Submitted:

16 February 2025

Posted:

17 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Poultry meat is the most consumed worldwide due to its low fat content, sensory qualities, and affordability. However, its rapid spoilage, especially when minced for products like hamburgers, is a challenge. Strategies such as sulphite addition or modified atmosphere packaging (MAP) can help control spoilage and microbial growth. This study evaluated both approaches by analyzing bacterial development in poultry hamburgers through total viable counts and MALDI-TOF identification. The addition of 5 mg/kg sulphites had a limited effect, whereas increasing CO2 levels in packaging significantly extended shelf life by reducing bacterial growth rates and prolonging lag phases. The most affected bacteria were aerobic mesophilic and psychrotrophic bacteria, as well as Brochothrix thermosphacta. Carnobacterium spp. dominated the aerobic mesophilic group, while Enterobacter spp. was prevalent in Enterobacteriaceae and aerobic mesophilic isolates, highlighting its role in spoilage. Hafnia alvei was also relevant in the final spoilage stages. These results suggest the importance of these bacteria in poultry hamburger decay and demonstrate that MAP is an effective method to delay spoilage.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Sampling and Sample Preparation

2.3. Bacterial Isolation

2.3.1. Bacterial Culture Media

2.3.2. Bacterial Culture Conditions

2.3.3. Identification by MALDI-TOF

2.4. Data Representation, Modelling and Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Bacterial Counts

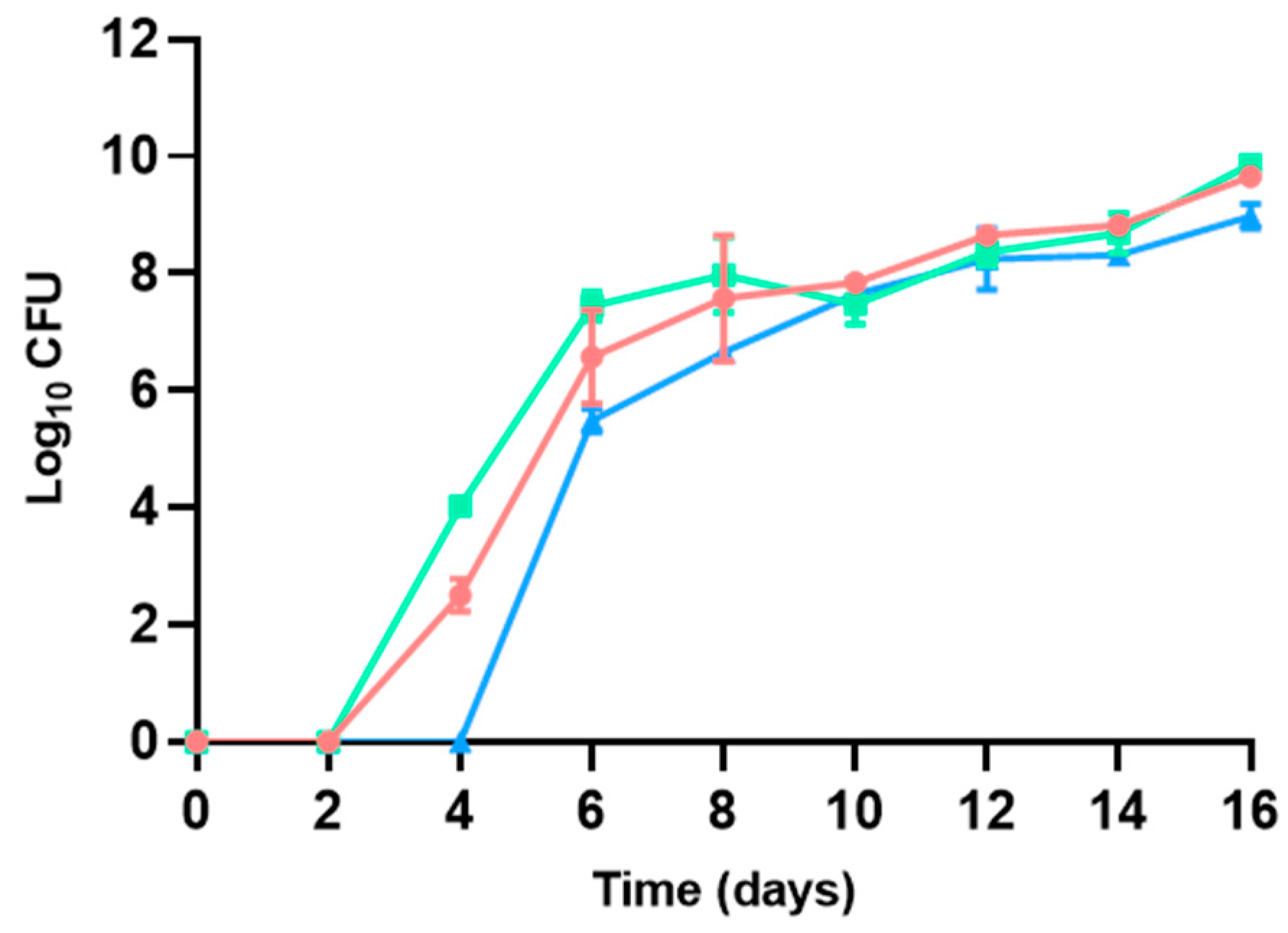

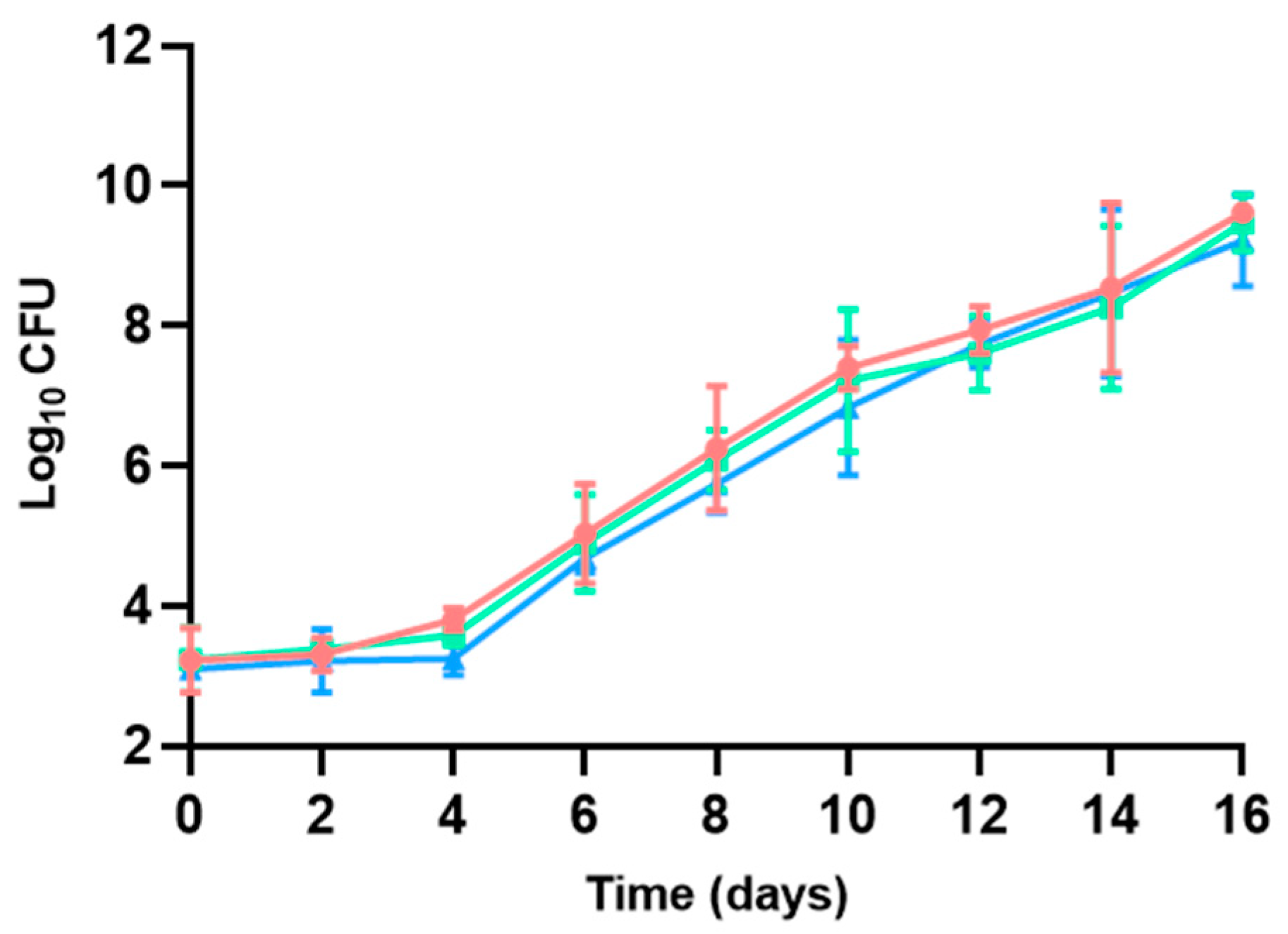

3.1.1. Aerobic Mesophilic Bacteria

3.1.2. Psychrotrophic Bacteria

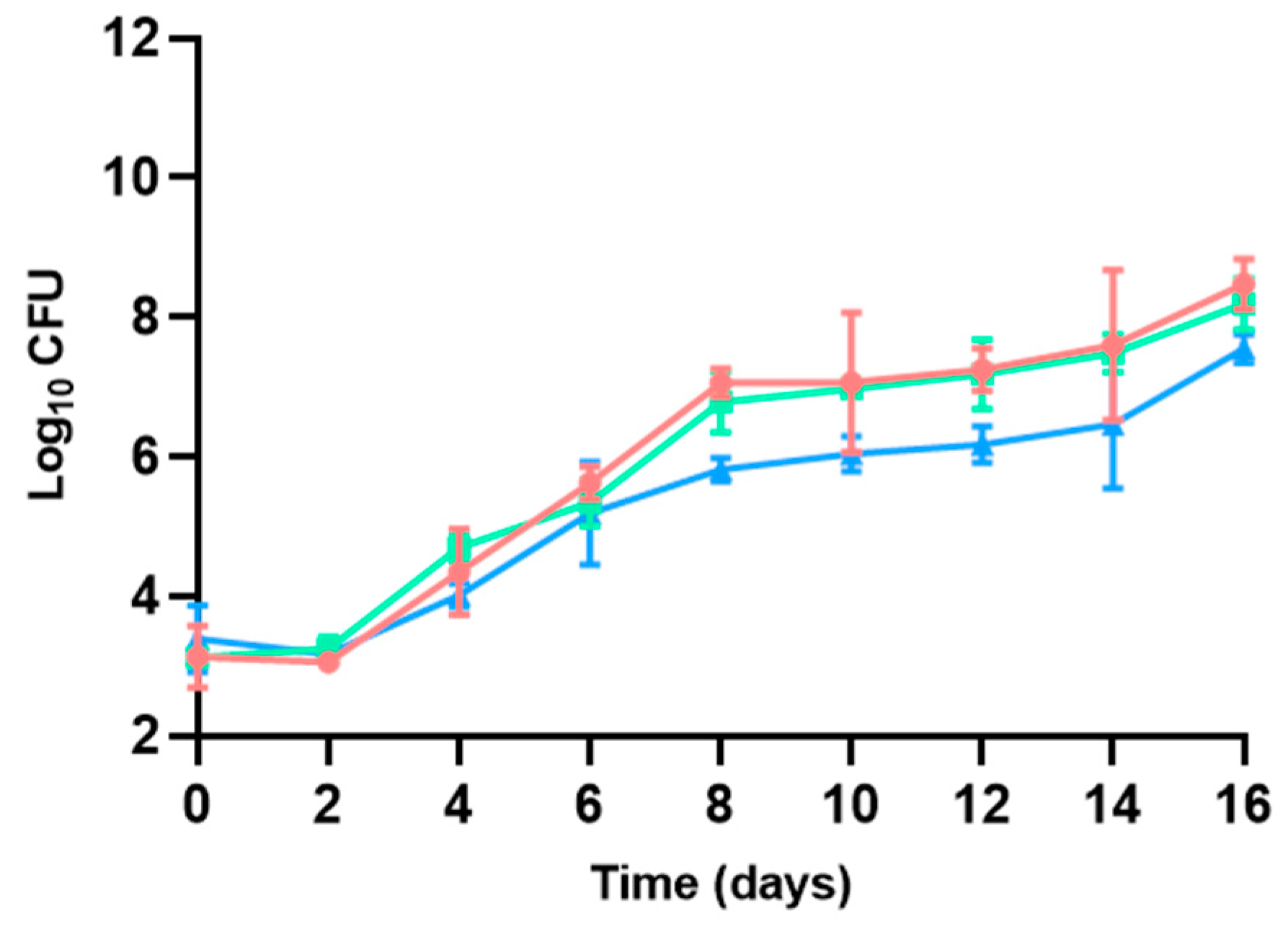

3.1.3. Enterobacteriaceae

3.1.4. Brochothrix thermosphacta

3.1.5. Pseudomonas spp.

3.1.6. Salmonella spp., Listeria spp. and Campylobacter spp.

3.2. Bacterial Identification

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ruiz-Capillas, C.; Herrero, A.M.; Pintado, T.; Delgado-Pando, G. Sensory analysis and consumer research in new meat products development. Foods 2021, 10, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Naeem, H.H.; Mohamed, H.M. Improving the physico-chemical and sensory characteristics of camel meat burger patties using ginger extract and papain. Meat Sci. 2016, 118, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Loo, E.J.; Caputo, V.; Lusk, J.L. Consumer preferences for farm-raised meat, lab-grown meat, and plant-based meat alternatives: Does information or brand matter? Food Policy 2020, 95, 101931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Zhou, G.; Song, S.; Xu, X.; Voglmeir, J.; Liu, L.; Li, C. Discrimination of in vitro and in vivo digestion products of meat proteins from pork, beef, chicken, and fish. Proteomics 2015, 15, 3688–3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.C.; Barrett, L.F. Affective beliefs influence the experience of eating meat. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0160424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longato, E.; Lucas-González, R.; Peiretti, P.G.; Meineri, G.; Pérez-Alvarez, J.A.; Viuda-Martos, M.; Fernández-López, J. The effect of natural ingredients (amaranth and pumpkin seeds) on the quality properties of chicken burgers. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2017, 10, 2060–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, K.D.L.; Moisés de Sousa, F.; Duarte de Almeida, R.; Pereira de Gusmão, R.; Gusmão, T.A.S. Replacement of fat by natural fibers in chicken burgers with reduced sodium content. The Open Food Science Journal 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martuscelli, M.; Esposito, L.; Mastrocola, D. The role of coffee silver skin against oxidative phenomena in newly formulated chicken meat burgers after cooking. Foods 2021, 10, 1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, P.J.; Mottet, A.; Opio, C.I.; Falcucci, A.; Teillard, F. Environmental impacts of beef production: Review of challenges and perspectives for durability. Meat Sci. 2015, 109, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babji, A.S.; Fatimah, S.; Abolhassani, Y.; Ghassem, M. Nutritional quality and properties of protein and lipid in processed meat products - a perspective. Int. Food Res. J. 2010, 17, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bohrer, B.M. Nutrient density and nutritional value of meat products and non-meat foods high in protein. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 65, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensio-Grau, A.; Calvo-Lerma, J.; Heredia, A.; Andrés, A. Fat digestibility in meat products: influence of food structure and gastrointestinal conditions. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 70, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Comission 2021. EU Agricultural Outlook for Markets, Income and Environment, 2021-2031. Available at: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/news/eu-agricultural-outlook-2021-31-sustainability-and-health-concerns-shape-agricultural-markets-2021-12-09_en. Accessed on: 7th March 2023.

- FAO, 2021. Food and Agriculture Organization. OECD Agricultural Outlook 2021-2030. Chapter 6. Meat. Available at: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.fao.org/3/cb5332en/Meat.pdf. Accessed on: 7th March 2023.

- Chouliara, E.; Karatapanis, A.; Savvaidis, I.N.; Kontominas, M.G. Combined effect of oregano essential oil and modified atmosphere packaging on shelf-life extension of fresh chicken breast meat, stored at 4° C. Food Microbiol. 2007, 24, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Calleja, J.M.; Cruz-Romero, M.C.; O’Sullivan, M.G.; García-López, M.L.; Kerry, J.P. High-pressure-based hurdle strategy to extend the shelf-life of fresh chicken breast fillets. Food Control 2012, 25, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraqueza, M.J.; Barreto, A.S. The effect on turkey meat shelf life of modified-atmosphere packaging with an argon mixture. Poult. Sci. 2009, 88, 1991–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraqueza, M.J.; Barreto, A.S. Gas mixtures approach to improve turkey meat shelf life under modified atmosphere packaging: The effect of carbon monoxide. Poult. Sci. 2011, 90, 2076–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilatos, G.C.; Savvaidis, I.N. Chitosan or rosemary oil treatments, singly or combined to increase turkey meat shelf-life. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 166, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirsa, S.; Shamusi, T. Intelligent and active packaging of chicken thigh meat by conducting nano structure cellulose-polypyrrole-ZnO film. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 102, 798–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercolini, D.; Russo, F.; Torrieri, E.; Masi, P.; Villani, F. Changes in the spoilage-related microbiota of beef during refrigerated storage under different packaging conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 4663–4671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte-Junior, C.A.; Monteiro, M.L.G.; Patrícia, R.; Mársico, E.T.; Lopes, M.M.; Alvares, T.S.; Mano, S.B. The effect of different packaging systems on the shelf life of refrigerated ground beef. Foods 2020, 9, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, J.E.; Brown, D.J.; Madsen, M.; Bisgaard, M. Cross-contamination with Salmonella on a broiler slaughterhouse line demonstrated by use of epidemiological markers. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 94, 826–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwirzitz, B.; Wetzels, S.U.; Dixon, E.D.; Fleischmann, S.; Selberherr, E.; Thalguter, S.; Stessl, B. Co-occurrence of Listeria spp. and spoilage associated microbiota during meat processing due to cross-contamination events. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 632935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ercolini, D.; Russo, F.; Nasi, A.; Ferranti, P.; Villani, F. Mesophilic and psychrotrophic bacteria from meat and their spoilage potential in vitro and in beef. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 1990–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haeghebaert, S.; Duché, L.; Gilles, C.; Masini, B.; Dubreuil, M.; Minet, J.C.; Vaillant, V. Minced beef and human salmonellosis: review of the investigation of three outbreaks in France. Eurosurveillance 2001, 6, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, M.K.; Alvarez-Ordonez, A.; Prieto, M.; Skjerve, E.; Asehun, T.; Alvseike, O.A. A systematic review of bacterial foodborne outbreaks related to red meat and meat products. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2018, 15, 598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellou, K.; Kyritsi, M.; Chrysostomou, A.; Sideroglou, T.; Georgakopoulou, T.; Hadjichristodoulou, C. Clostridium perfringens foodborne outbreak during an athletic event in northern Greece, June 2019. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA, 2022. Foodborne outbreaks. Available online at: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/microstrategy/FBO-dashboard. Accessed on: 7th March 2023.

- Roccato, A.; Uyttendaele, M.; Cibin, V.; Barrucci, F.; Cappa, V.; Zavagnin, P.; Ricci, A. Survival of Salmonella Typhimurium in poultry-based meat preparations during grilling, frying and baking. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 197, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nychas, G.-J.E.; Skandamis, P.N.; Tassou, C.C.; Koutsoumanis, K.P. Meat spoilage during distribution. Meat Sci. 2008, 78, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohareb, F.; Iriondo, M.; Doulgeraki, A.I.; Van Hoek, A.; Aarts, H.; Cauchi, M.; Nychas, G.J.E. Identification of meat spoilage gene biomarkers in Pseudomonas putida using gene profiling. Food Control 2015, 57, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odeyemi, O.A.; Alegbeleye, O.O.; Strateva, M.; Stratev, D. Understanding spoilage microbial community and spoilage mechanisms in foods of animal origin. Compr. Rev. Food. Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasinghe, N.N.; Ravensdale, J.; Coorey, R.; Chandry, S.P.; Dykes, G.A. The predominance of psychrotrophic pseudomonads on aerobically stored chilled red meat. Compr. Rev. Food. Sci. Food Saf. 2019, 18, 1622–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanborough, T.; Fegan, N.; Powell, S.M.; Tamplin, M.; Chandry, P.S. Insight into the genome of Brochothrix thermosphacta, a problematic meat spoilage bacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e02786–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kameník, J. The microbiology of meat spoilage: a review. Maso International - Journal of Food Science and Technology 2013, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Höll, L.; Behr, J.; Vogel, R.F. Identification and growth dynamics of meat spoilage microorganisms in modified atmosphere packaged poultry meat by MALDI-TOF MS. Food Microbiol. 2016, 2016 60, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ur Rahman, U.; Sahar, A.; Ishaq, A.; Aadil, R.M.; Zahoor, T.; Ahmad, M.H. Advanced meat preservation methods: A mini review. J. Food Saf. 2018, 38, e12467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, C.; Eslami, S.; Brunton, N.P.; Arimi, J.M.; Noci, F.; Lyng, J.G. An assessment of the impact of pulsed electric fields processing factors on oxidation, color, texture, and sensory attributes of turkey breast meat. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 1088–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, G.; D’Elia, F.; Soglia, F.; Tappi, S.; Petracci, M.; Rocculi, P. Exploring the effect of pulsed electric fields on the technological properties of chicken meat. Foods 2021, 10, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon-Rojo, A.D.; Carrillo-Lopez, L.M.; Reyes-Villagrana, R.; Huerta-Jiménez, M.; Garcia-Galicia, I.A. Ultrasound and meat quality: A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019, 55, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.D.; Holley, R.A. High hydrostatic pressure effects on the texture of meat and meat products. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, R17–R23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nychas, G.E.; Skandamis, P.N. Fresh meat spoilage and modified atmosphere packaging (MAP). In Improving the safety of fresh meat (pp. 461–502). 2005. Woodhead Publishing.

- Chouliara, E.; Badeka, A.; Savvaidis, I.; Kontominas, M.G. Combined effect of irradiation and modified atmosphere packaging on shelf-life extension of chicken breast meat: microbiological, chemical and sensory changes. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2008, 226, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Amore, T.; Di Taranto, A.; Berardi, G.; Vita, V.; Marchesani, G.; Chiaravalle, A.E.; Iammarino, M. Sulfites in meat: Occurrence, activity, toxicity, regulation, and detection. A comprehensive review. Compr. Rev. Food. Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 2701–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.H.; Xu, X.L.; Liu, Y. Preservation technologies for fresh meat - A review. Meat Sci. 2010, 86, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, A.R. Advances in modified-atmosphere packaging, in G. W. GOULD (ed.), New methods of food preservation, (pp. 304–320). 1995. Boston, MA: Springer US.

- Patsias, A.; Chouliara, I.; Badeka, A.; Savvaidis, I.N.; Kontominas, M.G. Shelf-life of a chilled precooked chicken product stored in air and under modified atmospheres: microbiological, chemical, sensory attributes. Food Microbiol. 2006, 23, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luning, P.A.; Jacxsens, L.; Rovira, J.; Osés, S.M.; Uyttendaele, M.; Marcelis, W.J. A concurrent diagnosis of microbiological food safety output and food safety management system performance: Cases from meat processing industries. Food Control 2011, 22, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milios, K.T.; Drosinos, E.H.; Zoiopoulos, P.E. Food Safety Management System validation and verification in meat industry: Carcass sampling methods for microbiological hygiene criteria - A review. Food Control 2014, 43, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Nobile, M.A.; Conte, A.; Cannarsi, M.; Sinigaglia, M. Strategies for prolonging the shelf life of minced beef patties. J. Food Saf. 2009, 29, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alp, E.; Aksu, M.İ. Effects of water extract of Urtica dioica L. and modified atmosphere packaging on the shelf life of ground beef. Meat Sci. 2010, 86, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Sadiq, F.A.; Burmølle, M.; Wang, N.I.; He, G. Insights into psychrotrophic bacteria in raw milk: a review. J. Food Prot. 2019, 82, 1148–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allende, A.; Aguayo, E.; Artés, F. Microbial and sensory quality of commercial fresh processed red lettuce throughout the production chain and shelf life. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 91, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Ruengwilysup, C.; Fung, D.Y.C. Antibacterial effect of water-soluble tea extracts on foodborne pathogens in laboratory medium and in a food model. J. Food Prot. 2004, 67, 2608–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupp, C.; Robertson, M.L.; Wickham, M.E.; Sekirov, I.; Champion, O.L.; Gaynor, E.C.; Finlay, B.B. Host-mediated inflammation disrupts the intestinal microbiota and promotes the overgrowth of Enterobacteriaceae. Cell host & microbe 2007, 2, 119–129. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Calleja, J.M.; Santos, J.A.; Otero, A.; García-López, M.L. Effect of vacuum and modified atmosphere packaging on the shelf life of rabbit meat. CyTA–Journal of Food 2010, 8, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, A.; Rygala, A.; Oltuszak-Walczak, E.; Walczak, P. The prevalence and some metabolic traits of Brochothrix thermosphacta in meat and meat products packaged in different ways. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012, 92, 1304–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remenant, B.; Jaffrès, E.; Dousset, X.; Pilet, M.R.; Zagorec, M. Bacterial spoilers of food: behavior, fitness and functional properties. Food Microbiol. 2015, 45, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouger, A.; Tresse, O.; Zagorec, M. Bacterial Contaminants of Poultry Meat: Sources, Species, and Dynamics. Microorganisms 2017, 5, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pin, C.; García de Fernando, G.D.; Ordónez, J.A. Effect of modified atmosphere composition on the metabolism of glucose by Brochothrix thermosphacta. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 4441–4447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainty, R.H.; Mackey, B.M. The relationship between the phenotypic properties of bacteria from chill-stored meat and spoilage processes. J. Appl. Bacteriol 1992, 73, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, R.K.; Griffiths, M.W.; Harris, L.J. Isolation and characterization of Carnobacterium, Lactococcus, and Enterococcus spp. from cooked, modified atmosphere packaged, refrigerated, poultry meat. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2000, 62, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drzewiecka, D. Significance and roles of Proteus spp. Bacteria in natural environments. Microb. Ecol. Microb. Ecol. 2016, 72, 741–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firildak, G.; Asan, A.; Goren, E. Chicken carcasses bacterial concentration at poultry slaughtering facilities. Asian. J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 8, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbruster, C.E.; Mobley, H.L.T.; Pearson, M.M. Pathogenesis of Proteus mirabilis infection. EcoSal Plus 2018, 8, 1–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, M.H.Y.; Wan, H.Y.; Chen, S. Characterization of multidrug-resistant Proteus mirabilis isolated from chicken carcasses. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2013, 10, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanches, M.S.; Baptista, A.A.S.; de Souza, M.; Menck-Costa, M.F.; Koga, V.L.; Kobayashi, R.K.T.; Rocha, S.P.D. Genotypic and phenotypic profiles of virulence factors and antimicrobial resistance of Proteus mirabilis isolated from chicken carcasses: potential zoonotic risk. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2019, 50, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aklilu, E.; Nurhardy, A.D.; Mokhtar, A.; Zahirul, I.K.; Rokiah, A.S. Molecular detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE) isolates in raw chicken meat. Int. Food Res. J. 2016, 23, 322. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Bai, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhou, G. Pathogenicity and antibiotic resistance of coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from retailing chicken meat. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 90, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miragaia, M.; Couto, I.; Pereira, S.F.; Kristinsson, K.G.; Westh, H.; Jarlov, J.O.; Carrico, J.; Almeida, J.; Santos-Sanches, I.; de Lencastre, H. Molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis clones: evidence of geographic dissemination. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, A.; Hoffmann, H. Prevalences of the Enterobacter cloacae complex and its phylogenetic derivatives in the nosocomial environment. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012, 31, 2951–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercolini, D.; Russo, F.; Blaiotta, G.; Pepe, O.; Mauriello, G.; Villani, F. Simultaneous detection of Pseudomonas fragi, P. lundensis, and P. putida from meat by use of a multiplex PCR assay targeting the carA gene. Compr. Rev. Food. Sci. Food Saf. 2007, 73, 2354–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoyama, M.; Kobayashi, M.; Sasaki, K.; Nomura, M.; Mitsumoto, M. Pseudomonas spp. convert metmyoglobin into deoxymyoglobin. Meat Sci. 2010, 84, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanborough, T.; Fegan, N.; Powell, S.M.; Singh, T.; Tamplin, M.; Chandry, P.S. Genomic and metabolic characterization of spoilage-associated Pseudomonas species. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 268, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, A.; Pérez, E.; de Faria, C.T.; Ferrús, M.A.; Carrascosa, C. Food spoilage by Pseudomonas spp. - An overview. In O. V. Singh (Ed.), Foodborne pathogens and antibiotic resistance (pp. 41–71). 2017. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

- Koutsoumanis, K.; Stamatiou, A.; Skandamis, P.; Nychas, G.J. Development of a microbial model for the combined effect of temperature and pH on spoilage of ground meat, and validation of the model under dynamic temperature conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qi, J.; Dong, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhou, G. Characterization of attachment and biofilm formation by meat-borne Enterobacteriaceae strains associated with spoilage. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 86, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidis, A.S.; Kalamaki, M.S.; Georgiadou, S.S. Identification of non-Listeria spp. bacterial isolates yielding a β-D-glucosidase-positive phenotype on Agar Listeria according to Ottaviani and Agosti (ALOA). Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 193, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Microbial group | Medium | Temperature (°C) | Incubation time (days) | Atmosphere | ISO standards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesophilic | TSA-YE | 35 | 1 | Aerobiosis | UNE-EN ISO 4833 |

| Psychrotrophic | TSA-YE | 7 | 7 | Aerobiosis | UNE-EN ISO 4833 |

| Enterobacteriaceae | VRBG | 35 | 1 | Aerobiosis | UNE-EN ISO 21528 |

| B.thermosphacta | STAA | 25 | 2 | Aerobiosis | - |

| Pseudomonas spp. | CFC | 20 | 2 | Aerobiosis | - |

| Salmonella spp. | XLD | 35 | 1 | Aerobiosis | UNE-EN ISO 6579 |

| L. monocytogenes | OCLA | 10 | 1 | Aerobiosis | UNE-EN ISO 11290 |

| Campylobacter spp. | CBFSA | 40 | 1 | Microaerophilia | EN-ISO 10.272-2 |

| Sulphites | Atmophere | Day 0 | Day 4 | Day 8 | Day 16 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Isolates | Identifcation | % Isolates | Identifcation | % Isolates | Identifcation | % Isolates | Identifcation | ||

| W/O* | Unmodified | 30 | Rothia nasimurium | 60 | Proteus mirabilis | 50 | Carnobacterium spp. | 80 | Carnobacterium spp. |

| 30 | Staphylococcus spp. | 30 | E.coli | 50 | B. subtilis | 10 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | ||

| 10 | Macrococcus caseolyticus | 10 | Staphylococcus simulans | 10 | Kurthia zopfii | ||||

| 10 | Escherichia coli | ||||||||

| 10 | Proteus mirabilis | ||||||||

| 10 | Corynebacterium phoceense | ||||||||

| W* | Unmodified | 70 | Carnobacterium spp | 50 | B. subtilis | 90 | Carnobacterium divergens | 100 | Carnobaterium spp. |

| 20 | Staphylococcus spp. | 20 | Staphylococcus simulans | 10 | Proteus mirabilis | ||||

| 10 | Enterococcus faecalis | 10 | Enterococcus faecalis | 10 | Proteus mirabilis | ||||

| 10 | Pseudomonas lundensis | ||||||||

| 10 | Carnobacterium divergens | ||||||||

| W/O* | Modified | 50 | Proteus mirabilis | 40 | Staphylococcus spp. | 50 | Carnobacterium spp. | 60 | Carnobacterium divergens |

| 20 | Microbacterium liquefacens | 20 | Rothia nasimuirum | 20 | Bacillus spp. | 30 | Enterobacter spp. | ||

| 10 | Carnobacterium maltaromaticum | 20 | Bacillus spp. | 20 | Staphylococcus spp. | 10 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | ||

| 10 | Rothia nasimurium | 20 | E. coli | 10 | E.coli | ||||

| 10 | Escherichia coli | ||||||||

| Sulphites | Atmophere | Day 0 | Day 4 | Day 16 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Isolates | Identifcation | % Isolates | Identifcation | % Isolates | Identifcation | ||

| W/O* | Unmodified | 75 | Pseudomonas lundensis | 100 | Enterobacter spp. | ||

| 25 | Staphylococcus epidermis | ||||||

| W* | Unmodified | 75 | Pseudomonas lundensis | 40 | Serratia liquefaciens | 60 | Enterobacter spp. |

| 25 | Staphylococcus epidermis | 20 | Pseudomonas lundensis | 40 | Hafnia alvei | ||

| 20 | Citrobacter freundii | ||||||

| 20 | Escherichia coli | ||||||

| W/O* | Modified | 75 | Pseudomonas lundensis | 80 | Escherichia coli | 100 | Enterobacter spp. |

| 25 | Staphylococcus epidermis | 20 | Hafnia alvei | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).