Significance Statement

Understanding the spatiotemporal dynamics of endogenous proteins and RNAs within the axon of adult neurons is critical for elucidating the mechanisms underlying fundamental axonal processes, such as local protein synthesis and transport. Recent advances in labeling technologies and efficient transduction systems for delivering large genetic payloads into adult neurons have made this study a possibility. This progress is essential for creating new strategies to treat neurodegenerative diseases, such as those caused due to nerve injuries.

Introduction

"Progress in science depends on new techniques, new discoveries and new ideas, probably in that order" – Sydney Brenner.

This situation cannot be truer for investigating the proteome and transcriptome of neurons. Neurons are highly polarized cells that are responsible for the communication of information in the brain. They are highly asymmetric in structure and terminally differentiated cells. As a result, they face the challenge of maintaining themselves over distances larger than other somatic cells. A healthy neuron needs to transport cargo from the cell body to the peripheral regions of the neuron without any impediment. Microtubules facilitate cargo transport by forming tracks. In axons, unlike dendrites, microtubules have a polarised arrangement with the plus end constituting the leading end. Motor proteins which predominantly fall into two classes namely kinesin and dynein determine the direction of the movement of cargo with kinesin controlling the anterograde motion and dynein controlling the retrograde motion (Guedes-Dias & Holzbaur, 2019). Mutations in any of the motor proteins lead to swellings in the axons which are enriched in vesicles and mitochondria (Chevalier-Larsen & Holzbaur, 2006). Over the past few years, a large body of work has underscored the importance of local protein synthesis and its regulation to maintain large stretches of neurites (Cioni et al., 2019). Different cellular components interact with each other and perform crucial roles to ensure that distal regions are kept functional. As an example, elements of both the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi apparatus have been detected in the axons and found to be functionally involved in the synthesis and subsequent transport of newly synthesized proteins to the plasma membrane (González et al., 2016; Merianda et al., 2009). Over the years, though many molecular details of axon composition have been solved, there is a need to elucidate a protein’s role from an endogenous standpoint within the mammalian system.

Early proteome investigation involved averaging approaches using biochemical methods to isolate proteins, followed by a sensitive detection technique such as Mass Spectrometry or large-scale RNA sequencing data. These have been instrumental in informing the experimenter about the population of proteins and RNA found in the neurons. Though the information obtained is average information from all compartments, nevertheless it is a start toward having information in the first place which would later inform on the experiment to be performed to deduce the spatial distribution of the protein. A drawback of these approaches is that the methods used are very varied and as a result, a consensus is difficult to arrive at. For instance, some studies restrict themselves to neuron-like cells such as NSC34 while others have employed more sophisticated approaches to extract information from a whole mammalian brain. Experiments that have used proximity approaches by employing APEX or TurboID or a combination of the two have been instrumental in conveying where proteins are compartmentalized and how their location changes in response to a certain stimulus such as stress. APEX has recently been used to characterize the Connexin complex that constitutes the gap junctions in electrical synapses. Electrical synapses like their chemical counterparts play an important role in several synaptic functions such as signal transmission and synaptic plasticity. However, the molecular components characterizing such a synapse have never been completely determined. Using CRISPR-tagged Connexin the authors successfully mined the Connexin interactome and found that electrical and chemical synapses occur together in a functional synaptic complex. Besides providing static information of local proteome, a modification of APEX termed TransitID incorporating a combination of APEX and TurboID was used to demonstrate how nuclear proteins travel from the nucleus to cytoplasmic SG granules. Further analysis revealed that proteins in these two populations were differentially soluble (Qin et al., 2023). In another study which demonstrated that RNA hitchhikes on endosomes, the authors combined APEX based protein mining approach to narrow down the potential candidate protein, Annexin11a, and used MS2-tagged RNA to help colocalize the RNA to Annexin11a. All these experiments require a tag for the protein. Precise localization information is best achieved if the tag is presented only on the endogenous proteins (Liao et al., 2019). Traditional methods of protein overexpression often provide only an approximate representation of protein localization. High levels of expression can mask a protein's true localization, making it challenging to study its precise native distribution. As a result, there is a growing need for gene editing techniques to introduce specific tags to proteins, allowing for a more accurate and native representation of their localization. These approaches enable the design of experiments that better reflect the protein's natural function within the cell.

In recent years, protein synthesis in neurites has been reported to be more complex than thought earlier. For instance, the endosomal pathways as a platform to transport RNA have emerged as a common theme that is conserved across disparate species such as fungi, reptiles, and mammals (Cioni et al., 2019; Kwon et al., 2020; Liao et al., 2019). Late endosomes facilitate protein synthesis giving rise to questions such as why only late endosomes or acidic compartments serve as platforms for translation. Is hitchhiking the only mode by which RNA can travel to distal regions of the neuron? Studies suggest that some RNA-moving cargo constitute fast axonal transport while those that hitchhike demonstrate a mixture of restricted and unrestricted mobility. A question that requires further investigation is how RNA granules differ from each other (Abraham & Fainzilber, 2022). Mitochondria also play a key role in local protein synthesis, while diseases that interfere with their function have been shown to cause abnormal deficits in the axons. RNA sequencing data from neurons and neuron-like cells such as NSC34 cells have provided a wealth of information about the RNA content within neurites, however, they lack compartmental information (Todd et al., 2013). Strategies like RiboTag address the lack of compartmentalization by providing cell-specific RNA information but are limited to transgenic mice engineered to express the RiboTag phenotype in specific cell types (Shigeoka et al., 2018).

A more unbiased way to investigate these issues is by employing techniques such as biochemical characterization of putative proteins followed by microscopy for further characterization. However, many challenges must be addressed before solving these issues. Microscopic approaches have traditionally relied on the overexpression of GFP-tagged proteins to capture the dynamics of the protein under interrogation. To what extent such an approach captures the native conditions of a protein is disputed (Willems et al., 2020). Biochemical methods of protein characterization have been the work-horse of protein function determination. However, biochemistry needs to be coupled with microscopic examination for a detailed display of a protein’s role in the cell. The best way to reconcile all these issues is to examine the role of the protein under native conditions. Recent advances in endogenous protein labeling technology have shed light on the distribution of native proteins in neurons (MacGillavry, 2023). Despite these successes in labeling technology, the greatest impediment to testing different approaches is the difficulty in transducing neurons with viruses capable of carrying a large payload such as a ~6 kb gene encoding Cas9-reverse transcriptase complex employed in prime editing. In this review, I describe different endogenous labeling strategies and argue for a need for a high-capacity gene transduction vector such as baculovirus to enable successful transduction of adult neurons which are recalcitrant to conventional transduction approaches.

Labeling Endogenous Proteins

Traditionally proteins have been labeled with antibodies. A caveat with the antibody labelling approach is that they are limited to fixed cells precluding investigation of proteins in live cells. To address this limitation, GFP-tagged intracellular antibodies can be genetically expressed within cells to target specific proteins (Trimmer, 2022). The most straightforward method for tagging endogenous proteins involves fusing the target protein with a fluorescent marker, such as GFP. CRISPR-based genome editing has advanced to the extent that it is now possible to edit the genome in many ways. Before surveying the various approaches to tagging endogenous proteins, it is important to understand the process of DNA repair which is crucial to choosing the right strategy for tagging. DNA like other macromolecules is constantly subjected to various stresses such as those due to reactive oxygen species resulting in double-stranded DNA breaks (DSB) (Capecchi, 2008). Cells predominantly employ two different strategies to correct the breaks: one based on homologous recombination, and the other based on non-homology end joining. These two repair mechanisms are quite distinct with the former requiring a donor DNA fragment containing appropriate homology arms and the latter requiring a suite of protein molecules including the enzyme ligase which are recruited to the sites of DNA double-stranded breaks (DSB) to facilitate their re-joining by ligation (Clarke et al., 2018). Early attempts at endogenous protein tagging relied heavily on homologous recombination, where a donor module with homology arms facilitated the process. However homologous recombination is restricted to dividing cells as it is active only during the late S/G2 phase of the cell cycle and is downregulated in post-mitotic cells such as neurons (Willems et al., 2020). Cells have a universal DSB repair mechanism which is independent of the cell cycle and relies on ligation of the free ends of the DSBs. Several homology-independent gene knock-in (KI) techniques have been developed, many of which utilize non-homology end joining (NHEJ) as a DNA repair mechanism. Further advances in CRISPR technology have also enabled manipulating the RNA directly thereby allowing direct visualization of RNA molecules besides proteins (Abudayyeh et al., 2017). Much of the KI effort is focused on tagging GFP allowing seamless microscopic characterization of the endogenous protein. These approaches are broadly divided into two categories: 1) those which target the exons of the gene and 2) those which target the introns of the gene.

Exon tagging:

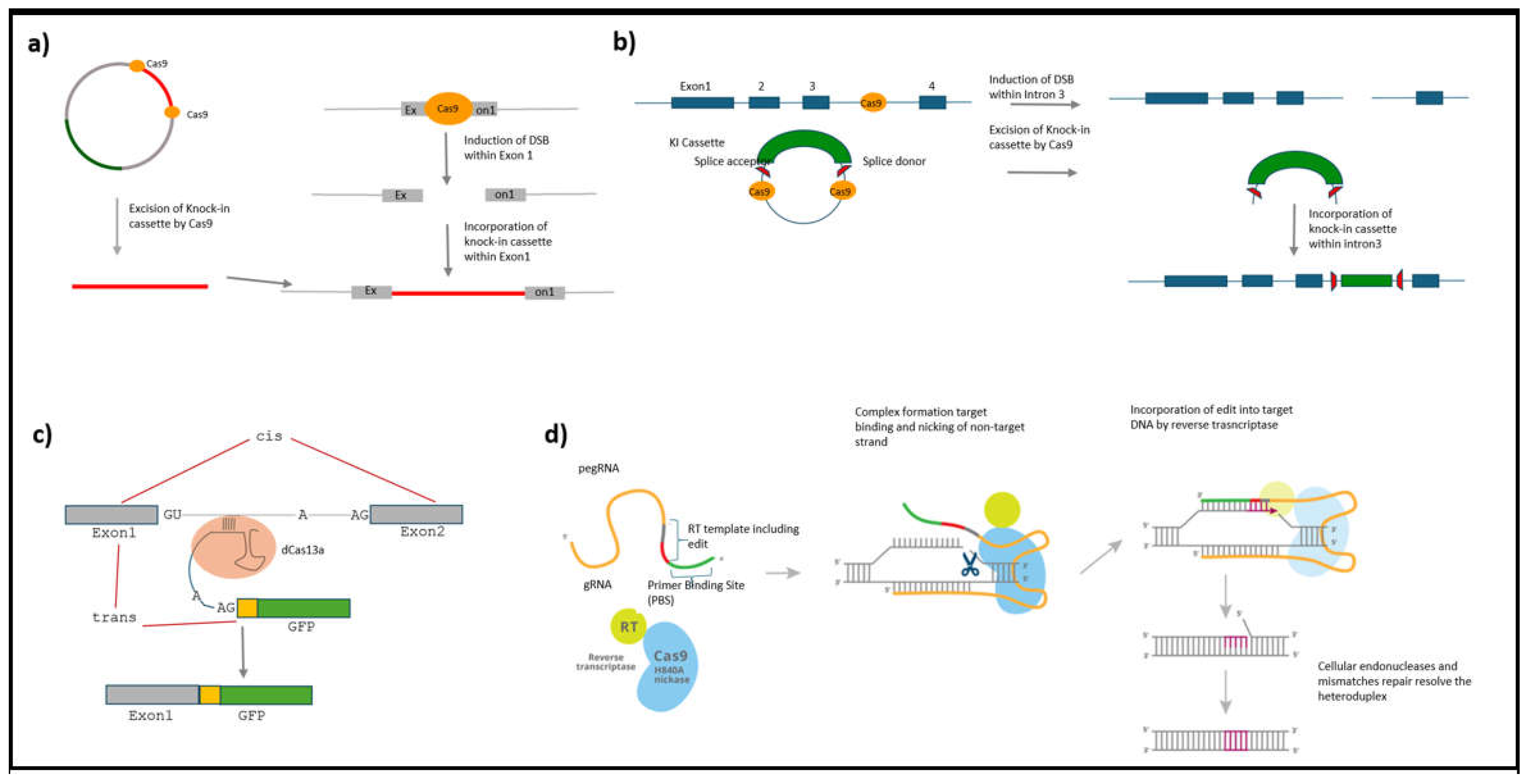

One of the early descriptions of this approach applied it as a method to tag the C-terminal portion of the protein. GFP-positive cells were automatically found to contain in-frame KI genes (Schmid-Burgk et al., 2016). However, not all proteins are amenable to C-terminal-based KI approaches. Some proteins tolerate better N-terminus-based tagging than C-terminus-based tagging. MacGillavry’s lab developed a technique that simplifies non-homology-based tagging of endogenous proteins by combining all the necessary elements into a single plasmid (

Figure 1a). The tag is flanked by guide sequences matching those on the target genomic DNA. This strategy ensures that the correct KI event results in a fluorescent event while the incorrect KI events result in non-fluorescent events. A drawback of the NHEJ is that while rejoining the two ends of DNA, a few nucleotides occasionally get incorporated in the form of insertions and deletions (INDELs). By ensuring proper localization and functioning of the protein this method has proven to be a great technique to tag endogenous proteins in cells despite INDELS. Several synaptic proteins such as PSD95, RIM, and Cav2.2 and cytoskeletal proteins such as actin and tubulin were tagged using this approach. Moreover, the authors also devised a unique way to perform dual color CRISPR tagging where a Cre recombinase, translated in combination with a fluorescent protein (but subsequently released into the cytosol by virtue of a P2A linker site), drives the activity of a second guide RNA leading to tagging of another protein (Willems et al., 2020). In conclusion, this technique provides a useful tool to investigate molecular events within axons by targeting axonal proteins.

Intron tagging:

One way to overcome the drawbacks of introducing mutations due to INDELs is to target the introns of a preRNA. Because introns are spliced out during mRNA maturation, targeting introns overcomes the problem caused by INDELs. The intron targeting approaches can be broadly classified into two types: one where the introns are targeted at the DNA level (Fang et al., 2021) and the other where introns are targeted at the RNA level (Berger et al., 2016; Chandrasekaran et al., 2024).

There have been various approaches targeting the introns at the genomic level. In one approach two guides targeting the introns are used to incorporate the module in the right region of the target. The module within the plasmid is flanked by guides which are also found in the target genome site. Though this study does not address the problems concerning changing the splicing sequences it nevertheless provides proof of the principle of avoiding INDELs characterized by targeting exons. Using this approach, the authors tag several proteins such as the AMPA receptors. A caveat in this study is that the experimenter is blind to mutations introduced in the splicing region. As a result, there is a high chance that this region is disturbed and splicing does not happen leading to a failed experiment (Fang et al., 2021). Splicing is a molecular process that is carried out by the spliceosome machinery in the nucleus. The process involves several cis-acting elements within the preRNA which determine the sequence of events resulting in the removal of the intron. The three main elements that are required for the process to happen are: 1) the 5' donor and the 3' acceptor splice site consensus sequence which mark the boundaries of an intron, 2) a branch point composed of an adenine located 18-40 bp upstream of 3' acceptor splice site and, 3) a polypyrimidine-rich (predominantly uracil rich region) sequence just before the 3' splice site. In a separate study, researchers created a donor module with flanking consensus splicing sequences, which allows the module to be processed as a synthetic exon and incorporated into the reading frame of the messenger RNA. Because of the use of a generic intron, a key feature of this strategy is that the module that needs to be inserted becomes generic facilitating the tagging of proteins at scale (

Figure 1b) (Reicher et al., 2024). For instance, Kubicek’s lab has used this approach to interrogate the effect of drugs on changes in the localization of proteins within the cell. One of the obstacles facing the CRISPR technology is the presence of non-target effects. Because introns are not as conserved as the exons, a great amount of care is required in the selection of guides. Because high target specificity is critical for CRISPR-based techniques, several software packages have been developed to assess guide sequences. One such tool, GuideScan, identifies all potential genomic matches of a given guide. Therefore, when using intron-based approaches, it is important to utilize a highly stringent algorithm that can prioritize guides based on the absolute number of on-target sites within the genome (Perez et al., 2017).

Because intron tagging is an error-safe approach, targeting at the level of the genome still constitutes a problem due to the presence of permanently editing the genome. Moreover, critics of endogenous labeling at the DNA level argue that such modification may lead to prolonged wait times for the expression of the intended change to become apparent. Targeting RNA for modification prevents indelible changes to the genomes and allows for an immediate observation of changes made. This technology predates CRISPR, taking inspiration from lower animals that can perform trans-splicing. Using a technology titled Spliceosome mediated RNA trans-splicing (SMaRT), a trans-splicing module is made to hybridize with a preRNA. Using an antisense oligo to block the 3’ cis-splicing region of the intron, it is possible to channel the process favoring the trans-splicing process. However, these early non-CRISPR attempts led to low (5%) yields of trans-spliced products (Berger et al., 2016). In a recent experiment employing dCas13d from

Ruminococcus flavefaciens (

Figure 1c), the authors present evidence of significant improvements in efficacy. Such RNA-based tagging approaches are ideal for use in neurons as the operation of the spliceosome machinery is a highly conserved feature present in all cell types (Chandrasekaran et al., 2024). Its application to unravel protein function within axons would be of great utility as changes made at the level of RNA become immediately apparent.

Prime Editing:

Unlike conventional CRISPR Cas9 mediated creation of DSB to introduce a KI cassette, prime editing is an approach that modifies the DNA by introducing a stretch of DNA containing a few base pairs by the use of a nick in the double-stranded DNA (Anzalone et al., 2019). As a result, prime editing qualifies as a gene editing technique to interrogate protein function within neurons. Unlike purely Cas9-based approaches to DNA modification, prime editing accomplishes its goal with the help of a single-strand cleaving nCas9 (known as nickase) fused to an RNA transcriptase that binds an RNA strand. Hybridization of the RNA strand to the nicked DNA strand allows it to act as a template to create a novel stretch of DNA spanning 20-40 bp in length extending the nicked DNA strand (

Figure 1d). Prime editing has been harnessed to introduce small epitope tags such as FLAG tag. In a recent experiment, higher molecular weight cargoes such as GFP can also be introduced by recombination mediated by Bbx1 recombinase (Anzalone et al., 2022). Alternatively, a short segment of GFP can be used to tag an endogenous protein. However, the experimenter is limited to working with cells that constitutively express the other half of the GFP. This approach reduces the payload due to prime editing to introduce a fluorescent tag (Sanchez et al., 2024). Given these great advances in prime editing technology, the future of gene tagging is poised to see many interesting applications capable of addressing many questions concerning axon outgrowth.

Intracellular Antibody Technology for Targeting Endogenous Proteins

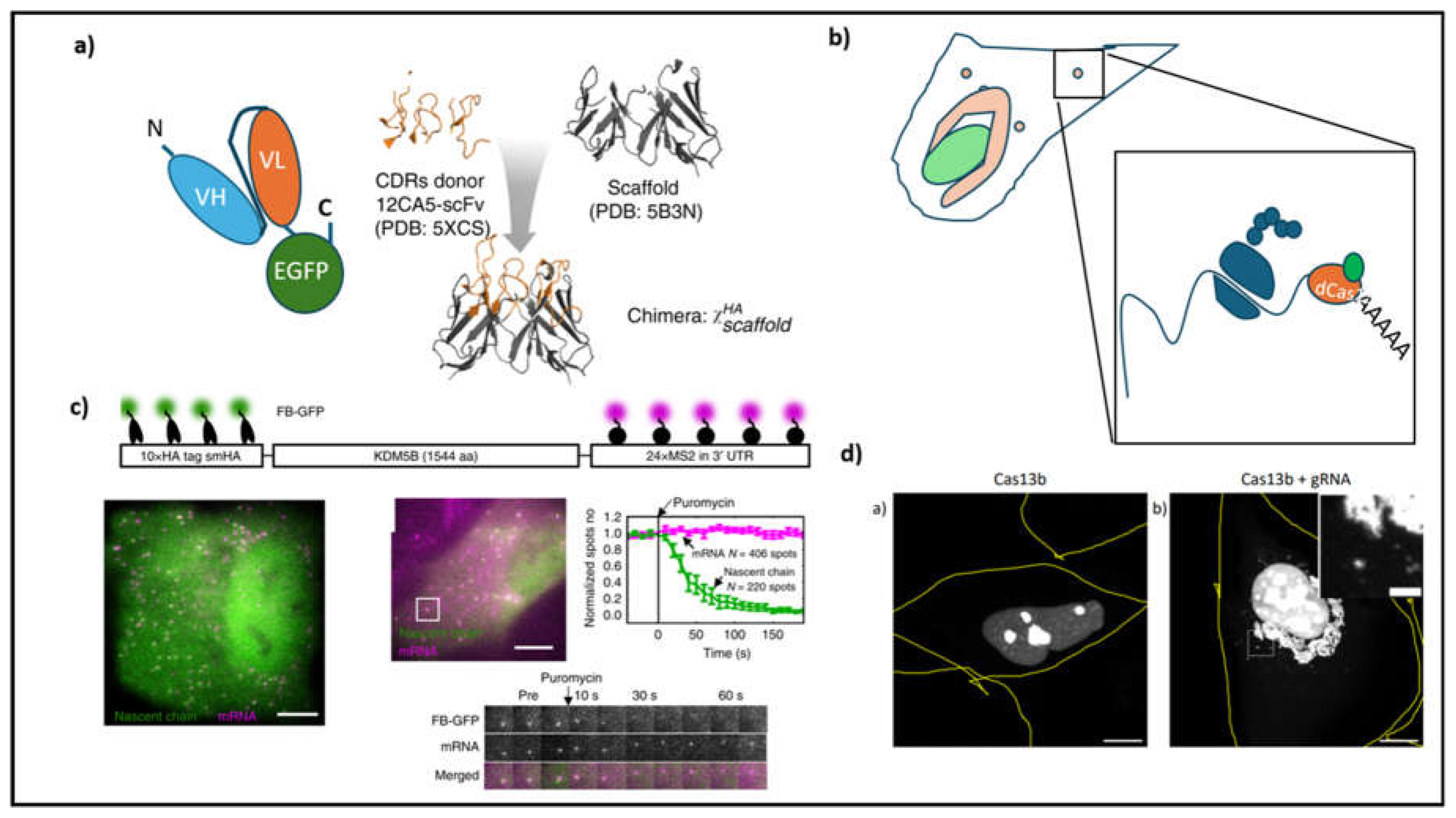

Historically antibodies were used to acquire spatial information of protein localization. Their use was primarily restricted to fixed samples. The bivalent characteristic of an antibody impedes its application to live imaging as it causes protein aggregation. Early attempts to overcome this problem entailed separating the Fab domain from the Fc domain by papain digestion. The separated Fab fragments, which are chemically conjugated to a fluorophore by N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) ester chemistry (a chemical reaction where the reactive ester group on the dye reacts with amine groups present in the proteins to form an amide linkage), would later be loaded into cells allowing the visualization of endogenous proteins and their modifications in the form of acetylation or phosphorylation. A major pitfall of this approach is that not all Fab fragments obtained in such a manner are stable and it is difficult to control the amounts of antibodies that are introduced in the cell (Sato et al., 2013; Trimmer, 2022). To solve this problem and to also genetically express them in cells, scientists combined the (single chain variable fragments of the antibody (scFv region) from two chains with the help of a flexible linker made of repeating serine-glycine units (

Figure 2a). Using this approach Kimura's group could localize specific post-translational modifications in histone proteins precisely (Sato et al., 2013).

In recent years monoclonal antibodies have been sequenced and cloned into expression vectors (Trimmer, 2022). Using protein structure prediction software such as abYmod, the sequence information can be used to predict the scFv regions and thus used for protein visualization studies conjugating them to GFP (Khetan et al., 2022). There are many parallel approaches to generating antibodies. In one study, the complementarity domains, obtained from a functional antibody, are transferred to a highly stable scFv scaffold thereby generating a highly stable intracellular antibody also known as Frankenbodies (

Figure 2a) (Zhao et al., 2019). Other approaches involve nanobodies obtained from single-chain antibodies isolated from animals such as camels, sharks, and llamas. Like antibodies, nanobodies can be reverse-translated into their genetic information and preserved as plasmids for later use in microscopic analysis. Besides these more traditional methods of antibody design, recent advancements in computational protein design are revolutionizing how antibodies are designed. For instance, Baker’s lab has developed a platform, called RosettaFold Diffusion (RF Diffusion), which can be used to construct a virtual antibody whose complementarity-determining region (CDR) is constrained by the epitope it is in contact with. In the second step, the tertiary structure of the ‘virtual antibody’ is back-translated into its primary sequence of amino acids which can then be tested for their binding efficacy (Bennett et al., 2024). Together these tools have enabled the design of intracellular antibodies. By employing a highly repetitive epitope tag system based on the epitope GCN4, which is recognized by a GFP-tagged scFv, fluorescence-signal amplification is achieved. This has enabled single-molecule imaging of cellular processes, ranging from in vivo tracking of kinesin-1 movement to tracking of nascent protein synthesis (

Figure 3c) (Morisaki et al., 2024; Tanenbaum et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2016). Besides scFv, FingRs (Fibronectin intrabodies generated with mRNA display) constitute another branch of intra-cellular antibodies that were developed to target synaptic protein such as PSD95. Like scFvs, which are designed to bind specific antigens, FingRs have been developed against specific excitatory and inhibitory synaptic proteins, such as PSD 95 and gephyrin, respectively. These intrabodies can be stably expressed in cells and include genetic control elements that regulate their expression, preventing overproduction and ensuring their specific enrichment at target sites. FingRs have been demonstrated to maintain the endogenous properties of the targeted protein without altering its distribution, both within the synapse and in other regions such as the spine neck (Son et al., 2016).

Labeling RNA

Previous attempts to track RNA have depended on the exogenous expression of RNA with specific modifications, such as MS2 repeats or fluorophore-binding aptamers (Park et al., 2014). Because Cas9 was a nucleotide-binding enzyme, there was soon a realization that it could be repurposed to function on RNA sequences. As a result, initial attempts at targeting RNA using CRISPR technology relied on modifying Cas9 in a way that its specificity could be altered to bind to a stretch of RNA. Unlike Cas9 which depends on the presence of an NGG PAM sequence within the template strand, RNA targeting RCas9 uses a separate strand, known as PAMer, to provide the PAM sequence. As a further extension, neutralizing the nuclease activity would result in an RCas9 that is capable of binding RNA without cleaving it (Nelles et al., 2015). Subsequently mining for different variants of CRISPR Cas enzymes led to the discovery of Cas13a which emerged as a highly efficient RNA-binding protein capable of cleaving the target RNA (East-Seletsky et al., 2016). Cas13a differs from Cas9 in having collateral RNA degrading activity. As a result, its application for diagnostics has garnered a lot of enthusiasm (Gootenberg et al., 2017). However, to make it applicable for RNA labeling site-specific mutation replacing catalytically relevant arginine residue produced a dead Cas13a (dCas13a) which can target specific RNA and track its fate of location within a cell without destroying it (

Figure 2b, d). Using this approach, the authors studied the localization of beta-actin mRNA to stress granules marked by G3BP1 (Abudayyeh et al., 2017). In neurons, such a labeling strategy will allow the experimenter to localize the RNA in different compartments of neurons. Previous attempts at RNA localization relied heavily on modified foreign RNA which contained MS2 loops. Such a strategy was used in a study that proved late endosomes served as hitchhiking platforms for RNA granules (Liao et al., 2019). Using dCas13a, a wide variety of endogenous RNAs can be tracked by altering the target guide sequence. This approach allows for precise, large-scale mapping of RNAs in specific neuronal compartments, such as growth cones or branch points.

Viral Vectors for Seamless Transduction:

Much of the biology about the fate of molecules within the axon would become intractable to investigation without a proper viral vector to transduce neurons. Although key principles of neuron function have been explored in young neurons, many biological processes relevant to aging and neurodegeneration are specific to adult neurons. A classical case for aging-related neurodegeneration is provided by the early onset of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Transgenic mice model of AD (APPswe/PS1ΔE9) exhibit early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. These mice's cortical and hippocampal neurons have immature spine morphology, affecting their performance in memory-related tasks (Kommaddi et al., 2018). Actin has been known to be post-translationally modified by glutathionylation and in the presence of the enzyme, glutathioredoxin keeps the actin protein in a reduced state. At any given point, the oxidative state of the cell determines the extent of glutathionylation of the actin. Spine development and maturation is an immense interplay of different components of a chemical synapse. In a follow-up study, the authors use viral-based gene delivery to overexpress glutathioredoxin, which maintains actin in the reduced sulfhydryl state, and reverses premature spine morphology (Kommaddi et al., 2019). This finding underscores the critical role of targeted interventions to correct genetic deficits. Gene therapeutic approaches, in particular, have shown increasing efficacy in addressing nervous system disorders. For example, Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA), a condition characterized by the atrophy of motor neuron axons, can now be treated effectively by overexpressing the Survival of Motor Neuron (SMN) protein. A promising development comes from Fischer's lab, which discovered that treatment of the sensorimotor cortex with hyper interleukin 6 (hIL-6) leads to the regeneration of axons of motor neurons of mice that underwent axotomy. They report that transduction of the corticospinal tract (CST) with hIL6 stimulates the regenerative potential of CST and the neurons they connect, namely the raphe-spinal tract in the brain stem. This occurs because the synthesized hIL6 in CST neurons is transported to the axon terminus for secretion where hIL6 further stimulates the raphespinal tract leading to axonal regenerations after nerve injury (Terheyden-Keighley et al., 2022). Additionally, approaches that can also target sensory neurons in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) such as Dorsal root ganglion cells (DRGs) help to understand axon regeneration and axon transport in the mammalian system. Investigations from Fainzilber’s lab have revealed that axotomized DRGs lead to the recruitment of mTOR mRNA to the regions of injury to facilitate nerve outgrowth (Terenzio et al., 2018). Traditional approaches to investigating neurons by targeted delivery of the virus do not work as DRGs are deeply embedded within the vertebral column. In contrast, adult DRGs in culture are extremely hard to transduce with any of the available viral methods. A great benefit of working with DRGs is that they are amenable to culturing from adult mice forming a model for understanding how adult neurons succumb to various injury-related insults such as sciatic nerve axotomy (Sahoo et al., 2018). These situations underscore the need for a viral-based gene delivery system that can transduce neurons located in impenetrable regions of the mammalian body.

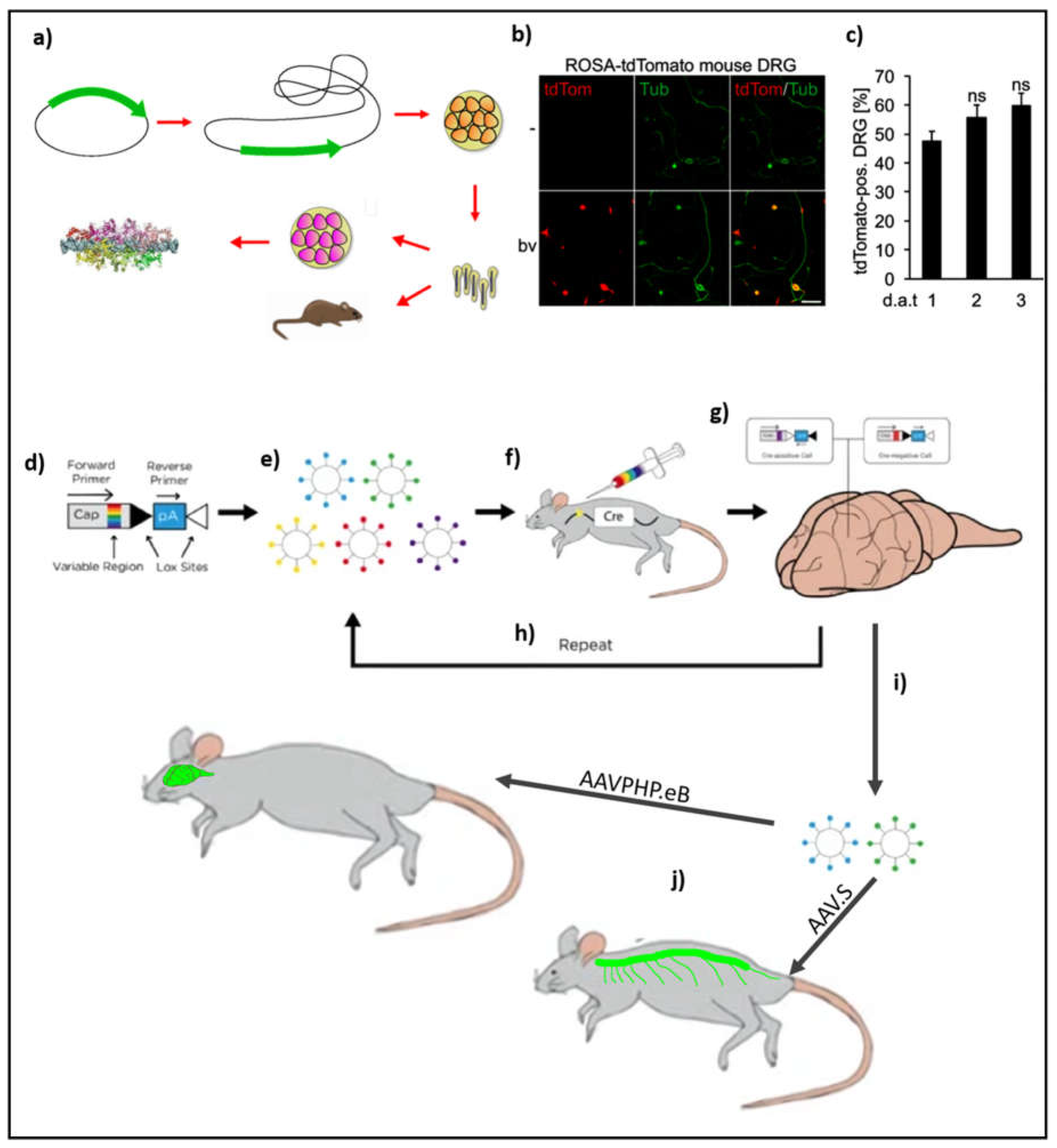

For in-vitro purposes, traditional approaches to transfecting neurons involve lipofection or electroporation of neurons. A limitation of lipofection is that these reagents are highly effective primarily in young neuronal cultures. While electroporation offers an alternative for gene delivery in difficult-to-transfect cells like adult neurons, the procedure's harsh electrical pulses often result in cell death during culturing. As a result of the drawback of both electroporation and lipofectamine, a much-preferred approach is to use a virus such as adeno-associated virus (AAV) or lentivirus (LV) (Levin et al., 2016; Schaly et al., 2021). However, recombinant LVs are especially toxic to cells as their genome tends to combine with the host’s genomic DNA at random locations. Given such issues of cytotoxicity and an inability to transduce adult neurons, the exploration of viruses that can overcome these barriers continues to be an unmet need. One such virus is the baculovirus which is an insect virus found to transduce mammalian cells also. Unlike AAVs and LVs, baculoviruses can carry genes exceeding 100 kb in load (Haase et al., 2013). As a result, these viruses have come to be employed by structural biologists for studying large protein complexes such as membrane proteins (

Figure 3a) (Goehring et al., 2014). Owing to their reduced cytotoxicity, these viruses are also gaining acceptance as gene therapeutic agents in treating diseases (Schaly et al., 2021). In a recent study addressing the aforementioned limitation of transducing neurons Fischer’s lab found that baculoviruses infect adult DRGs with rates exceeding 80% (Figure 4b and 4c). The ability of a baculovirus to transfect recalcitrant cells is primarily due to the presence of a surface protein called gp64 which helps in its efficient endocytosis into the host cell. This study offers a great potential to introduce into adult DRGs cargoes of differing payload capacities opening the avenue for high-resolution light microscopic interrogation of endogenous proteins within cells. As a consequence, baculovirus has gene therapeutic potential and future experiments will provide crucial information about their efficacy in vivo.

AAVs have been the traditional work-horse of gene delivery systems in both in-vitro and in-vivo studies of the brain. The traditional application of AAV has been restricted to areas of the brain that are under direct investigation. The extent of transduction in such cases was a function of the virus titer. This approach would also expose the brain to damage due to the insertion of the needle. On the other hand, intravenous application of AAV9 led to the transduction of very few neurons owing to the requirement of crossing the blood-brain barrier. A few years ago, Gardinaru’s lab devised a directed-evolution procedure that resulted in the enrichment of an AAV variant which can cross the blood-brain barrier thereby leading to the transduction of neurons. Briefly, they created a library of cap proteins that differed from each other due to a stretch of 7 amino acids between amino acid 588 and amino acid 589. This extra 7 amino acid stretch was randomized to create a library of cap proteins which were assessed for their ability to cross the blood-brain barrier. The selection procedure was done in such a way that the scientists introduced a loxP cassette within the polyA region which when acted upon by Cre recombinase uncovered a bar code that is used as a reverse primer in the downstream PCR validation step (

Figure 3d). Using these variants, a pool of viral particles with different capsid phenotypes is generated (

Figure 2e). This pool of viruses is subsequently injected intravenously into the mice (

Figure 3f). Following the expression of the fluorescent protein in the brain, the mice are sacrificed and their brains are harvested for PCR analysis of the transgene (

Figure 3g). After undergoing many rounds of selection (

Figure 3h), the efficacy of viruses to cross the blood-brain barrier and infect a specific population of cells in the CNS is improved. This strategy resulted in the selection of those viruses, namely AAV PHP.eB and AAV.S, which transduced cells found in the CNS and the PNS, respectively (

Figure 3 i,j). Cells that were traditionally very difficult to transduce with AAV such as the dorsal root ganglion cells were also found to successfully take up the virus. Moreover, the experiments to enrich CNS infecting viruses were performed on adult mice where neurons are generally recalcitrant to AAV-based viral transduction. These experiments have demonstrated that AAVs can be made to undergo selection for the enrichment of those variants that can successfully transduce brain cells in both juvenile and adult mice (Chan et al., 2017). While working with prime editing, however, the genetic payload would cross the permissible capacity of AAV. In such a case it is possible to implement inteins to divide the protein thereby allowing the AAVs to carry the entire payload by employing a divide-and-conquer approach (Davis et al., 2024).

In conclusion, recent developments in packaging and transduction technology have made it possible to carry large payloads of genetic material to both the CNS and PNS of the mammalian nervous system. Fine-tuning by using cell-type-specific promoters would lead to the targeting of specific cells. This technology is successful in both in-vitro and in-vivo scenarios and as a result, will witness increasing usage in the study of adult peripheral neurons such as dorsal root ganglion cells.

Discussion

The past few years have witnessed an explosion in our understanding of how proteins in axons travel to sustain a labyrinth of neurites originating from a neuron. Many lines of evidence suggest that axons are self-sufficient in many of the components of a cell’s secretory pathway providing the necessary infrastructure for much of the synthesis and subsequent targeting of proteins to their designated areas of function (González et al., 2016). Microtubules form tracks upon which retrograde and anterograde cargo transport occur. Moreover, cargo traveling over the microtubules can be broadly classified as fast-moving and slowing-moving cargo. Fast-moving cargo contains vesicular cargo and, 2) slow-moving cargo contains filamentous and organelle-based cargo (Guedes-Dias & Holzbaur, 2019). Mitochondria and extra mitochondria-based glycogenic pathways provide the necessary energy with extra mitochondrial energy sources providing the bulk of energy for processes such as fast axon transport (Yang et al., 2024). Despite such a wealth of information, many questions require greater investigation into the life of the macromolecules populating the axons. Though over-expression of proteins through the introduction of genes via transfection is the preferred mode of investigation, it is replete with confounding problems (Willems et al., 2020). As a result, there is a need to understand proteins in their nativity, requiring the use of technologies that can target endogenous proteins thereby allowing their observation in real-time.

Much of the progress in science depends on the ease with which technology can be used to answer questions. CRISPR provides a great example. Initial attempts at tagging employed a homologous recombination-based KI approach which was highly instrumental in revealing many details about the location of an endogenous protein. However, homologous recombination-based approaches are confined to dividing cells excluding post-mitotic cells like neurons thereby propelling scientists to develop non-homology-based KI approaches (MacGillavry, 2023). Because genomic engineering leaves an indelible mark on the cell, a more transient approach involving editing preRNA to introduce tags could be suitable for some applications. This technique is based on trans-splicing, a known biological phenomenon, but is further refined by employing RNA binding CRISPR dCas13d to improve its KI efficacy (Chandrasekaran et al., 2024). Alternatively, intracellular antibodies can be engineered to target proteins within cells. Earlier attempts to use antibodies involved their fragmentation to isolate only the Fab region which is later loaded into the cell. Given the many pitfalls of this approach and the lack of an ability to propagate the tag across generations, intracellular antibodies are engineered at the genetic level. Much of this effort has been due to improvements in protein folding prediction technology enabling the generation of chimeric tools (Zhao et al., 2019). The full benefit of these improvements in labeling technologies is dependent on the capacity to effectively target specific cell types. This is particularly relevant for studying neurodegenerative diseases, where protein aggregates accumulate in the neurites of adult neurons due to genetic predispositions, like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and Alzheimer's disease. Traditional, approaches to transduction involve the use of LVs and AAVs which result in low transduction efficiencies in adult neurons (Levin et al., 2016). As a result, there is a growing need to explore and develop virus transduction approaches that can successfully transduce adult cells. The generation of improved variants of AAVs by selection for targeting adult neurons was a major step forward in developing effect transduction approaches. AAV PHP.eB and AAV.S are particularly effective in crossing the blood-brain barrier in C57BL/6 thereby establishing AAV for use in both in vitro and in-vivo studies (Beth Kenkel, 2017; Chan et al., 2017). A drawback of using AAV is its limited cargo capacity. However, this can be overcome by making use of inteins in a divide and conquer approach (Davis et al., 2024). An alternative strategy, though currently limited to neurons in cultures, is to use the insect virus baculovirus. Baculovirus has gained popularity due to its capacity to carry large payloads of cargo and its ability to transfect a wide variety of cell types across different ages. Such a transduction system is an ideal system to deploy large CRISPR-based gene editing machinery into highly recalcitrant cells such as the dorsal root ganglion cells from an adult mouse.

In the final analysis, endogenous tagging of proteins within adult neurons provides important information on protein function within neuronal compartments. This approach will help us understand many unanswered questions dealing with the importance of acidic compartments for protein synthesis. As promising as the approaches are, there are nevertheless limitations which the experimenter would need to work with. For example, not all RNAs within the axon are of equal abundance. Therefore, in trying to image RNAs that are low in abundance, highly sensitive imaging platforms could be used such as TIRF microscopy. This limitation is also exploited in diagnostic platforms which aim to provide diagnosis in a short period (Shinoda et al., 2021). In addition, appropriate controls need to ensure that the binding of probes to molecules does not hamper the functioning of protein or RNA. Given the initial successes of using this technology in studying the protein and RNA function, the aforementioned obstacles can be overcome to provide useful information on the working of proteins within the axon.

Limitations

Tag-based approaches need to be considered on a case-by-case approach. Proteins that are successfully tagged need to be fully characterized to demonstrate that they are equivalent to endogenous proteins. A KI experiment carried out in Ellenberg’s lab found that about 25% of human proteins cannot be successfully tagged. Moreover, some cells can tolerate only a heterozygous KI condition for some genes (Koch et al., 2018). In such cases, alternative approaches to gene editing should be explored. Intra-cellular antibody-based tagging is a particularly powerful alternative. Though antibody-based tagging proteins may also potentially interfere with their function, its development with proper controls should allow its successful implementation in studying the spatial distribution of proteins. A potential caveat in APEX experiments is the need for a high copy number of the APEX moieties. Experiments employing tagging of low-copy numbered endogenous RNA by Cas13 approach did not result in substantial biotinylation of interacting proteins and RNAs necessitating over-expression of RNA. In conclusion, these approaches can only be followed for those proteins which are amenable to being tagged. For those that cannot be tagged, their function can be elucidated indirectly by studying their interacting partners.

Intron based-tagging, though devoid of potential problems associated with INDELs, nevertheless need to be evaluated before use. This is due to the fact that introns tend to possess many regulatory elements which can interfere with the proper functioning of the cell. For instance, the introns of nucleolin contain sequences which code for snoRNAs which play an important role in ribosome maturation (Julia Fremerey, 2016). In the past decade, research on circular RNA has unravelled many circular RNA sites found predominantly in the 5’ region of the mRNA. Circular RNAs have regulatory roles such as buffering the activity of miRNA (Rybak-Wolf et al., 2015). As a result, intron-based tagging of protein at the N-terminal site would potentially interfere the critical functioning of the circular RNA.

Lastly, AAV PHP.eB and AAV.S serotypes exhibit a narrow tropism, restricting their application primarily to the C57BL/6 mouse strain. To expand its tropism, researchers have investigated delivering the virus directly into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cavity, enabling more effective neuronal transduction. Nonetheless, the use of high viral titers poses a significant challenge, as it increases toxicity and leads to the death of infected neurons.

Acknowledgments

SN wishes to acknowledge several colleagues for discussions during his time as a postdoc studying the biology of a neuron.

Conflicts of Interest

The author has no conflicts to declare

References

- Abraham, O., & Fainzilber, M. (2022). Riding the rails - different modes for RNA complex transport in axons. Neural Regeneration Research, 17(12), 2664–2665. [CrossRef]

- Abudayyeh, O. O., Gootenberg, J. S., Essletzbichler, P., Han, S., Joung, J., Belanto, J. J., Verdine, V., Cox, D. B. T., Kellner, M. J., Regev, A., Lander, E. S., Voytas, D. F., Ting, A. Y., & Zhang, F. (2017). RNA targeting with CRISPR-Cas13. Nature, 550(7675), 280–284. [CrossRef]

- Anzalone, A. V, Gao, X. D., Podracky, C. J., Nelson, A. T., Koblan, L. W., Raguram, A., Levy, J. M., Mercer, J. A. M., & Liu, D. R. (2022). Programmable deletion, replacement, integration and inversion of large DNA sequences with twin prime editing. Nature Biotechnology 40(5), 731–740. [CrossRef]

- Anzalone, A. V, Randolph, P. B., Davis, J. R., Sousa, A. A., Koblan, L. W., Levy, J. M., Chen, P. J., Wilson, C., Newby, G. A., Raguram, A., & Liu, D. R. (2019). Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature, 576(7785), 149–157. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N. R., Watson, J. L., Ragotte, R. J., Borst, A. J., See, D. L., Weidle, C., Biswas, R., Shrock, E. L., Leung, P. J. Y., Huang, B., Goreshnik, I., Ault, R., Carr, K. D., Singer, B., Criswell, C., Vafeados, D., Sanchez, M. G., Kim, H. M., Torres, S. V., … Baker, D. (2024). Atomically accurate de novo design of single-domain antibodies. BioRxiv : The Preprint Server for Biology. [CrossRef]

- Berger, A., Maire, S., Gaillard, M.-C., Sahel, J.-A., Hantraye, P., & Bemelmans, A.-P. (2016). mRNA trans-splicing in gene therapy for genetic diseases. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. RNA, 7(4), 487–498. [CrossRef]

- Beth Kenkel. (2017, September 28). AAVs CREATed for Gene Delivery to the CNS and PNS. Addgene Blog.

- Capecchi, M. (2008). The first transgenic mice: an interview with Mario Capecchi. Interview by Kristin Kain. Disease Models & Mechanisms, 1(4–5), 197–201. [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, S. S., Tau, C., Nemeth, M., Pawluk, A., Konermann, S., & Hsu, P. D. (2024). Rewriting endogenous human transcripts with trans -splicing. [CrossRef]

- Chan, K. Y., Jang, M. J., Yoo, B. B., Greenbaum, A., Ravi, N., Wu, W.-L., Sánchez-Guardado, L., Lois, C., Mazmanian, S. K., Deverman, B. E., & Gradinaru, V. (2017). Engineered AAVs for efficient noninvasive gene delivery to the central and peripheral nervous systems. Nature Neuroscience, 20(8), 1172–1179. [CrossRef]

- Chevalier-Larsen, E., & Holzbaur, E. L. F. (2006). Axonal transport and neurodegenerative disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1762(11–12), 1094–1108. [CrossRef]

- Cioni, J.-M., Lin, J. Q., Holtermann, A. V, Koppers, M., Jakobs, M. A. H., Azizi, A., Turner-Bridger, B., Shigeoka, T., Franze, K., Harris, W. A., & Holt, C. E. (2019). Late Endosomes Act as mRNA Translation Platforms and Sustain Mitochondria in Axons. Cell, 176(1–2), 56-72.e15. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R., Heler, R., MacDougall, M. S., Yeo, N. C., Chavez, A., Regan, M., Hanakahi, L., Church, G. M., Marraffini, L. A., & Merrill, B. J. (2018). Enhanced Bacterial Immunity and Mammalian Genome Editing via RNA-Polymerase-Mediated Dislodging of Cas9 from Double-Strand DNA Breaks. Molecular Cell, 71(1), 42-55.e8. [CrossRef]

- Davis, J. R., Banskota, S., Levy, J. M., Newby, G. A., Wang, X., Anzalone, A. V, Nelson, A. T., Chen, P. J., Hennes, A. D., An, M., Roh, H., Randolph, P. B., Musunuru, K., & Liu, D. R. (2024). Efficient prime editing in mouse brain, liver and heart with dual AAVs. Nature Biotechnology 42(2), 253–264. [CrossRef]

- East-Seletsky, A., O’Connell, M. R., Knight, S. C., Burstein, D., Cate, J. H. D., Tjian, R., & Doudna, J. A. (2016). Two distinct RNase activities of CRISPR-C2c2 enable guide-RNA processing and RNA detection. Nature, 538(7624), 270–273. [CrossRef]

- Fang, H., Bygrave, A. M., Roth, R. H., Johnson, R. C., & Huganir, R. L. (2021). An optimized CRISPR/Cas9 approach for precise genome editing in neurons. ELife, 10. [CrossRef]

- Goehring, A., Lee, C.-H., Wang, K. H., Michel, J. C., Claxton, D. P., Baconguis, I., Althoff, T., Fischer, S., Garcia, K. C., & Gouaux, E. (2014). Screening and large-scale expression of membrane proteins in mammalian cells for structural studies. Nature Protocols, 9(11), 2574–2585. [CrossRef]

- González, C., Cánovas, J., Fresno, J., Couve, E., Court, F. A., & Couve, A. (2016). Axons provide the secretory machinery for trafficking of voltage-gated sodium channels in peripheral nerve. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(7), 1823–1828. [CrossRef]

- Gootenberg, J. S., Abudayyeh, O. O., Lee, J. W., Essletzbichler, P., Dy, A. J., Joung, J., Verdine, V., Donghia, N., Daringer, N. M., Freije, C. A., Myhrvold, C., Bhattacharyya, R. P., Livny, J., Regev, A., Koonin, E. V., Hung, D. T., Sabeti, P. C., Collins, J. J., & Zhang, F. (2017). Nucleic acid detection with CRISPR-Cas13a/C2c2. Science, 356(6336), 438–442. [CrossRef]

- Guedes-Dias, P., & Holzbaur, E. L. F. (2019). Axonal transport: Driving synaptic function. Science (New York, N.Y.), 366(6462), 31601744. [CrossRef]

- Haase, S., Ferrelli, L., Luis, M., & Romanowski, V. (2013). Genetic Engineering of Baculoviruses. In Current Issues in Molecular Virology - Viral Genetics and Biotechnological Applications. InTech. [CrossRef]

- Julia Fremerey. (2016). NUCLEOLIN: A NUCLEOLAR RNA-BINDING PROTEIN INVOLVED IN RIBOSOME BIOGENESIS. PhD Thesis, 1–237.

- Khetan, R., Curtis, R., Deane, C. M., Hadsund, J. T., Kar, U., Krawczyk, K., Kuroda, D., Robinson, S. A., Sormanni, P., Tsumoto, K., Warwicker, J., & Martin, A. C. R. (2022). Current advances in biopharmaceutical informatics: guidelines, impact and challenges in the computational developability assessment of antibody therapeutics. MAbs, 14(1), 2020082. [CrossRef]

- Koch, B., Nijmeijer, B., Kueblbeck, M., Cai, Y., Walther, N., & Ellenberg, J. (2018). Generation and validation of homozygous fluorescent knock-in cells using CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. Nature Protocols, 13(6), 1465–1487. [CrossRef]

- Kommaddi, R. P., Das, D., Karunakaran, S., Nanguneri, S., Bapat, D., Ray, A., Shaw, E., Bennett, D. A., Nair, D., & Ravindranath, V. (2018). Aβ mediates F-actin disassembly in dendritic spines leading to cognitive deficits in Alzheimer’s disease. The Journal of Neuroscience, 38(5), 1085–1099. [CrossRef]

- Kommaddi, R. P. , Tomar, D. S., Karunakaran, S., Bapat, D., Nanguneri, S., Ray, A., Schneider, B. L., Nair, D., & Ravindranath, V. (2019). Glutaredoxin1 Diminishes Amyloid Beta-Mediated Oxidation of F-Actin and Reverses Cognitive Deficits in an Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Model. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling, 31(18), 1321–1338. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S., Tisserant, C., Tulinski, M., Weiberg, A., & Feldbrügge, M. (2020). Inside-out: from endosomes to extracellular vesicles in fungal RNA transport. Fungal Biology Reviews, 34(2), 89–99. [CrossRef]

- Levin, E., Diekmann, H., & Fischer, D. (2016). Highly efficient transduction of primary adult CNS and PNS neurons. Scientific Reports, 6, 38928. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.-C., Fernandopulle, M. S., Wang, G., Choi, H., Hao, L., Drerup, C. M., Patel, R., Qamar, S., Nixon-Abell, J., Shen, Y., Meadows, W., Vendruscolo, M., Knowles, T. P. J., Nelson, M., Czekalska, M. A., Musteikyte, G., Gachechiladze, M. A., Stephens, C. A., Pasolli, H. A., … Ward, M. E. (2019). RNA Granules Hitchhike on Lysosomes for Long-Distance Transport, Using Annexin A11 as a Molecular Tether. Cell, 179(1), 147-164.e20. [CrossRef]

- MacGillavry, H. D. (2023). Recent advances and challenges in the use of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing for understanding neuronal cell biology. Neurophotonics, 10(4), 044403. [CrossRef]

- Merianda, T. T., Lin, A. C., Lam, J. S. Y., Vuppalanchi, D., Willis, D. E., Karin, N., Holt, C. E., & Twiss, J. L. (2009). A functional equivalent of endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi in axons for secretion of locally synthesized proteins. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience 40(2), 128–142. [CrossRef]

- Morisaki, T., Wiggan, O., & Stasevich, T. J. (2024). Translation Dynamics of Single mRNAs in Live Cells. Annual Review of Biophysics 53(1), 65–85. [CrossRef]

- Nelles, D. A., Fang, M. Y., Aigner, S., & Yeo, G. W. (2015). Applications of Cas9 as an RNA-programmed RNA-binding protein. BioEssays : News and Reviews in Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology, 37(7), 732–739. [CrossRef]

- Park, H. Y., Lim, H., Yoon, Y. J., Follenzi, A., Nwokafor, C., Lopez-Jones, M., Meng, X., & Singer, R. H. (2014). Visualization of dynamics of single endogenous mRNA labeled in live mouse. Science (New York, N.Y.) 343(6169), 422–424. [CrossRef]

- Perez, A. R., Pritykin, Y., Vidigal, J. A., Chhangawala, S., Zamparo, L., Leslie, C. S., & Ventura, A. (2017). GuideScan software for improved single and paired CRISPR guide RNA design. Nature Biotechnology 35(4), 347–349. [CrossRef]

- Qin, W., Cheah, J. S., Xu, C., Messing, J., Freibaum, B. D., Boeynaems, S., Taylor, J. P., Udeshi, N. D., Carr, S. A., & Ting, A. Y. (2023). Dynamic mapping of proteome trafficking within and between living cells by TransitID. Cell, 186(15), 3307-3324.e30. [CrossRef]

- Reicher, A., Reiniš, J., Ciobanu, M., Růžička, P., Malik, M., Siklos, M., Kartysh, V., Tomek, T., Koren, A., Rendeiro, A. F., & Kubicek, S. (2024). Pooled multicolour tagging for visualizing subcellular protein dynamics. Nature Cell Biology 26(5), 745–756. [CrossRef]

- Rybak-Wolf, A., Stottmeister, C., Glažar, P., Jens, M., Pino, N., Giusti, S., Hanan, M., Behm, M., Bartok, O., Ashwal-Fluss, R., Herzog, M., Schreyer, L., Papavasileiou, P., Ivanov, A., Öhman, M., Refojo, D., Kadener, S., & Rajewsky, N. (2015). Circular RNAs in the Mammalian Brain Are Highly Abundant, Conserved, and Dynamically Expressed. Molecular Cell, 58(5), 870–885. [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P. K., Lee, S. J., Jaiswal, P. B., Alber, S., Kar, A. N., Miller-Randolph, S., Taylor, E. E., Smith, T., Singh, B., Ho, T. S.-Y., Urisman, A., Chand, S., Pena, E. A., Burlingame, A. L., Woolf, C. J., Fainzilber, M., English, A. W., & Twiss, J. L. (2018). Axonal G3BP1 stress granule protein limits axonal mRNA translation and nerve regeneration. Nature Communications, 9(1), 3358. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, H. M., Lapidot, T., & Shalem, O. (2024). High-throughput optimized prime editing mediated endogenous protein tagging for pooled imaging of protein localization. BioRxiv : The Preprint Server for Biology. [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y., Mukai, M., Ueda, J., Muraki, M., Stasevich, T. J., Horikoshi, N., Kujirai, T., Kita, H., Kimura, T., Hira, S., Okada, Y., Hayashi-Takanaka, Y., Obuse, C., Kurumizaka, H., Kawahara, A., Yamagata, K., Nozaki, N., & Kimura, H. (2013). Genetically encoded system to track histone modification in vivo. Scientific Reports, 3, 2436. [CrossRef]

- Schaly, S., Ghebretatios, M., & Prakash, S. (2021). Baculoviruses in Gene Therapy and Personalized Medicine. Biologics : Targets & Therapy, 15, 115–132. [CrossRef]

- Schmid-Burgk, J. L., Höning, K., Ebert, T. S., & Hornung, V. (2016). CRISPaint allows modular base-specific gene tagging using a ligase-4-dependent mechanism. Nature Communications, 7, 12338. [CrossRef]

- Shigeoka, T., Jung, J., Holt, C. E., & Jung, H. (2018). Axon-TRAP-RiboTag: Affinity Purification of Translated mRNAs from Neuronal Axons in Mouse In Vivo. Methods in Molecular Biology (Clifton, N.J.), 1649, 85–94. [CrossRef]

- Shinoda, H., Taguchi, Y., Nakagawa, R., Makino, A., Okazaki, S., Nakano, M., Muramoto, Y., Takahashi, C., Takahashi, I., Ando, J., Noda, T., Nureki, O., Nishimasu, H., & Watanabe, R. (2021). Amplification-free RNA detection with CRISPR-Cas13. Communications Biology, 4(1), 476. [CrossRef]

- Son, J.-H., Keefe, M. D., Stevenson, T. J., Barrios, J. P., Anjewierden, S., Newton, J. B., Douglass, A. D., & Bonkowsky, J. L. (2016). Transgenic FingRs for Live Mapping of Synaptic Dynamics in Genetically-Defined Neurons. Scientific Reports, 6, 18734. [CrossRef]

- Tanenbaum, M. E., Gilbert, L. A., Qi, L. S., Weissman, J. S., & Vale, R. D. (2014). A protein-tagging system for signal amplification in gene expression and fluorescence imaging. Cell, 159(3), 635–646. [CrossRef]

- Terenzio, M., Koley, S., Samra, N., Rishal, I., Zhao, Q., Sahoo, P. K., Urisman, A., Marvaldi, L., Oses-Prieto, J. A., Forester, C., Gomes, C., Kalinski, A. L., Di Pizio, A., Doron-Mandel, E., Perry, R. B.-T., Koppel, I., Twiss, J. L., Burlingame, A. L., & Fainzilber, M. (2018). Locally translated mTOR controls axonal local translation in nerve injury. Science, 359(6382), 1416–1421. [CrossRef]

- Terheyden-Keighley, D., Leibinger, M., & Fischer, D. (2022). Transneuronal delivery of designer cytokines: perspectives for spinal cord injury. Neural Regeneration Research, 17(2), 338. [CrossRef]

- Todd, A. G., Lin, H., Ebert, A. D., Liu, Y., & Androphy, E. J. (2013). COPI transport complexes bind to specific RNAs in neuronal cells. Human Molecular Genetics 22(4), 729–736. [CrossRef]

- Trimmer, J. S. (2022). Genetically encoded intrabodies as high-precision tools to visualize and manipulate neuronal function. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology, 126, 117–124. [CrossRef]

- Willems, J., de Jong, A. P. H., Scheefhals, N., Mertens, E., Catsburg, L. A. E., Poorthuis, R. B., de Winter, F., Verhaagen, J., Meye, F. J., & MacGillavry, H. D. (2020). ORANGE: A CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing toolbox for epitope tagging of endogenous proteins in neurons. PLoS Biology, 18(4), e3000665. [CrossRef]

- Wu, B., Eliscovich, C., Yoon, Y. J., & Singer, R. H. (2016). Translation dynamics of single mRNAs in live cells and neurons. Science (New York, N.Y.) 352(6292), 1430–1435. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S., Niou, Z.-X., Enriquez, A., LaMar, J., Huang, J.-Y., Ling, K., Jafar-Nejad, P., Gilley, J., Coleman, M. P., Tennessen, J. M., Rangaraju, V., & Lu, H.-C. (2024). NMNAT2 supports vesicular glycolysis via NAD homeostasis to fuel fast axonal transport. Molecular Neurodegeneration 19(1), 13. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N., Kamijo, K., Fox, P. D., Oda, H., Morisaki, T., Sato, Y., Kimura, H., & Stasevich, T. J. (2019). A genetically encoded probe for imaging nascent and mature HA-tagged proteins in vivo. Nature Communications, 10(1), 2947. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).