1. Introduction

Centrifugal pump is widely used for various applications due to its low initial cost and better performance at high speed. An impeller is one of the main components of the centrifugal pump. The impeller is a rotating part of a centrifugal pump, and its performance depends on the quality of the impeller [

1]. The surface quality of the impeller affects the efficiency and output of the centrifugal pump. As surface roughness increases, the efficiency of a pump decreases [

2]. Also, pump overall efficiency is influenced by impeller dimensions like blade height, blade angle, number of blades, and impeller diameter [

3]. So, dimensional accuracy and surface quality are key quality indicators for an impeller.

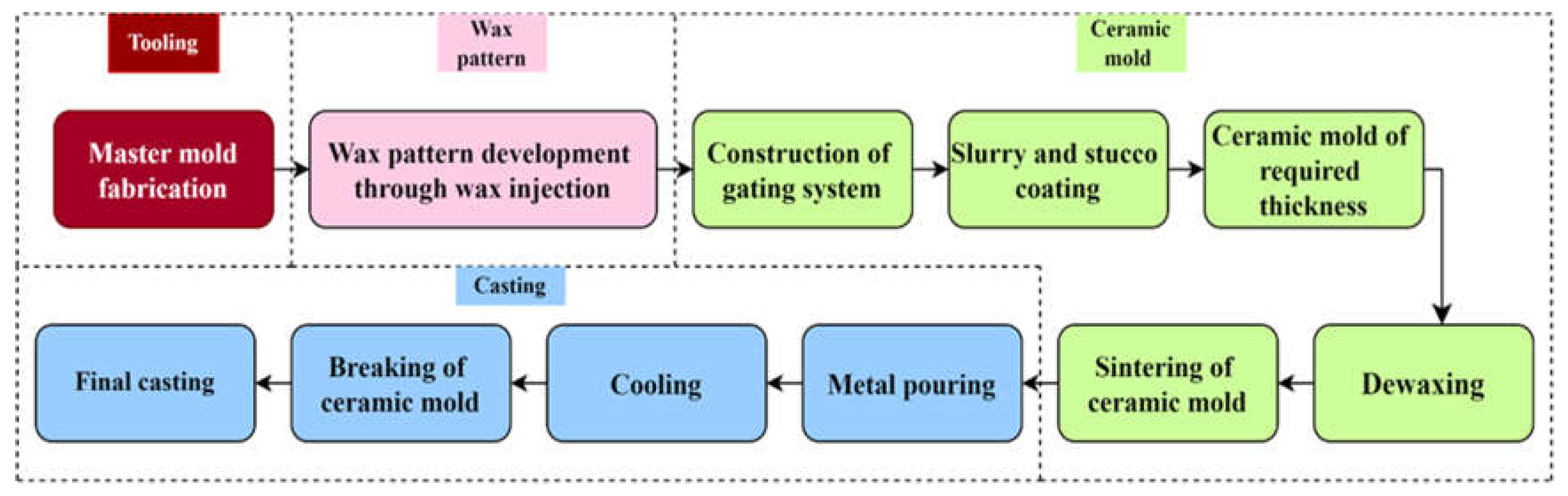

Investment casting (IC) is appropriate for manufacturing parts like impellers, which have intricate shapes, complex geometry, and thin sections. These parts have high dimensional accuracy and good surface finish, which negates the necessity of further finishing. This process involves several steps, i.e., fabrication of metal die called master mould, wax pattern development through wax injection, construction of a gating system, slurry, and stucco coating to produce a ceramic mold of required thickness, dewaxing, sintering of ceramic mold, metal pouring, cooling, and breaking of ceramic mold to get final casting [

4].

Figure 1 shows the step-by-step procedure of the conventional IC process.

Figure 1.

Step-by-step procedure of conventional investment casting process.

Figure 1.

Step-by-step procedure of conventional investment casting process.

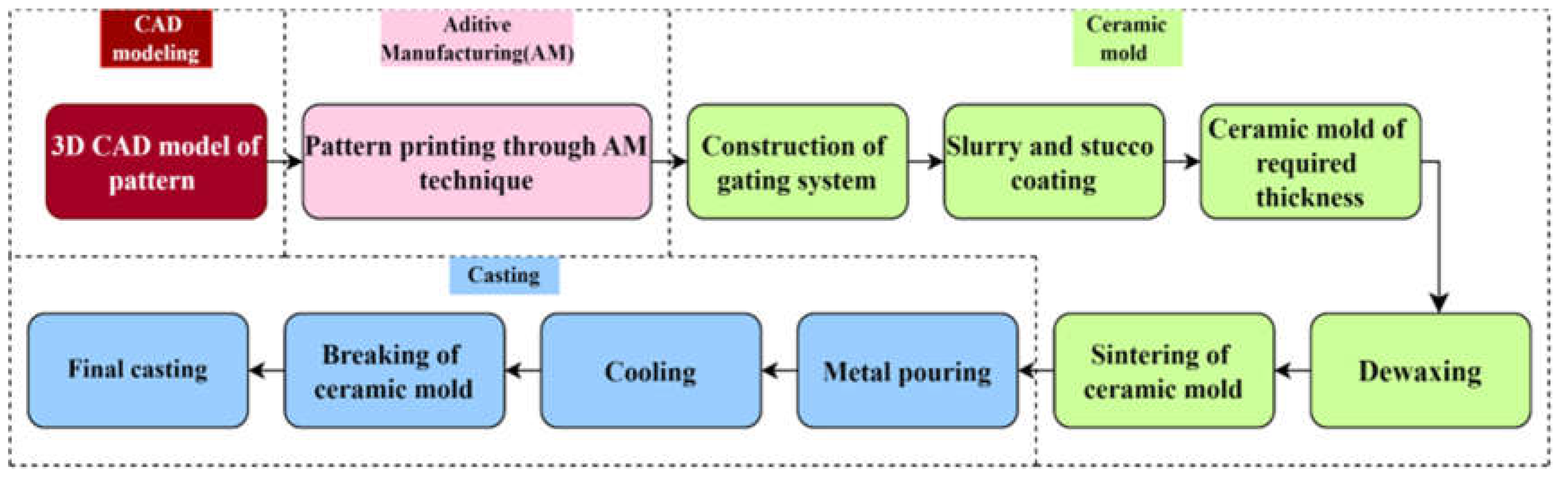

Figure 2.

Step-by-step procedure of rapid investment casting process-Direct tooling method.

Figure 2.

Step-by-step procedure of rapid investment casting process-Direct tooling method.

This process has some snags, which include a long product development cycle time, higher specific energy depletion, continual human capital requirements, environmental effects, etc. A major cause for these is the tooling required for patterns. It includes manufacturing aluminum die through a series of conventional and non-conventional machining processes based on the complexity level. This results in high lead time and cost [

5]. So, conventional investment casting is the most cost-effective option for mass production but is not apt for customized or batch production.

Lead time reduction is possible through a rapid investment casting (RIC) process. This process allows us to eliminate long and expensive tooling processes. Research shows that 60 to 80 percent lead time reduction can be achieved through Additive Manufacturing (AM) assisted RIC. In this process, the conventional wax pattern is replaced by a 3D printed pattern called the direct tooling method, or the aluminum die is replaced by a 3D printed mold called the indirect tooling method.

Figure 2 shows a step-by-step procedure for the direct tooling RIC method [

5,

6,

7]. Conventional wax pattern development has some issues like high cost of tooling, shrinkage at wide sections, trouble in injection molding of complex shapes, warping, and poor dimensional accuracy at slim features. The use of the 3D printed pattern by AM technique provides better flexibility, strength, and dimensional accuracy compared to this conventional wax pattern [

8]. The most popular AM technique is the Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) method due to its economical and simple operation, flexibility, fast printing, and low tooling cost [

9]. This method is suited to 3D printing of material having low melting point temperature, which matches the material properties requirements for sacrificial patterns used in investment casting.

Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) plastic proves its suitability for FDM printed patterns used as sacrificial patterns in investment casting. Research shows that FDM-printed ABS patterns give good dimensional stability and clean burnout [

10]. The dimensional accuracy of the FDM printed ABS part was studied by several researchers for the shapes like holes, slots having different sections, solid and hollow cylinders, spheres, inclined faces, various prisms, cuboids, thin features, etc. It is observed that small features show more dimensional variations and warping compared to larger ones [

11]. Another research shows that FDM-printed square parts with flat surfaces have better dimensional accuracy compared to cylindrical and elliptical-shaped parts. Also, as the wall thickness of a part increases, its dimensional accuracy will decrease due to the shrinkage of print material, and wall thickness accuracy will increase. It shows that parts with curved and thin features need more focus while printing to achieve better dimensional accuracy [

12]. It is preferable to set the nominal value of the curved feature in the 3D CAD model higher than its actual value to balance the negative dimensional deviation that occurred in the final part print. The compensation applied on nominal dimensions depends on the size and shape of the individual feature [

13].

Table 2 shows various FDM-printed ABS parts used as sacrificial patterns in investment casting. Casting and FDM printing parameters are studied to understand their effect on the quality of FDM printed patterns and final casting. From the literature survey, we can conclude that many experiments have been done to find optimum process parameter values to achieve better quality of FDM printed pattern and final cast through the RIC process [

14]-[

20].

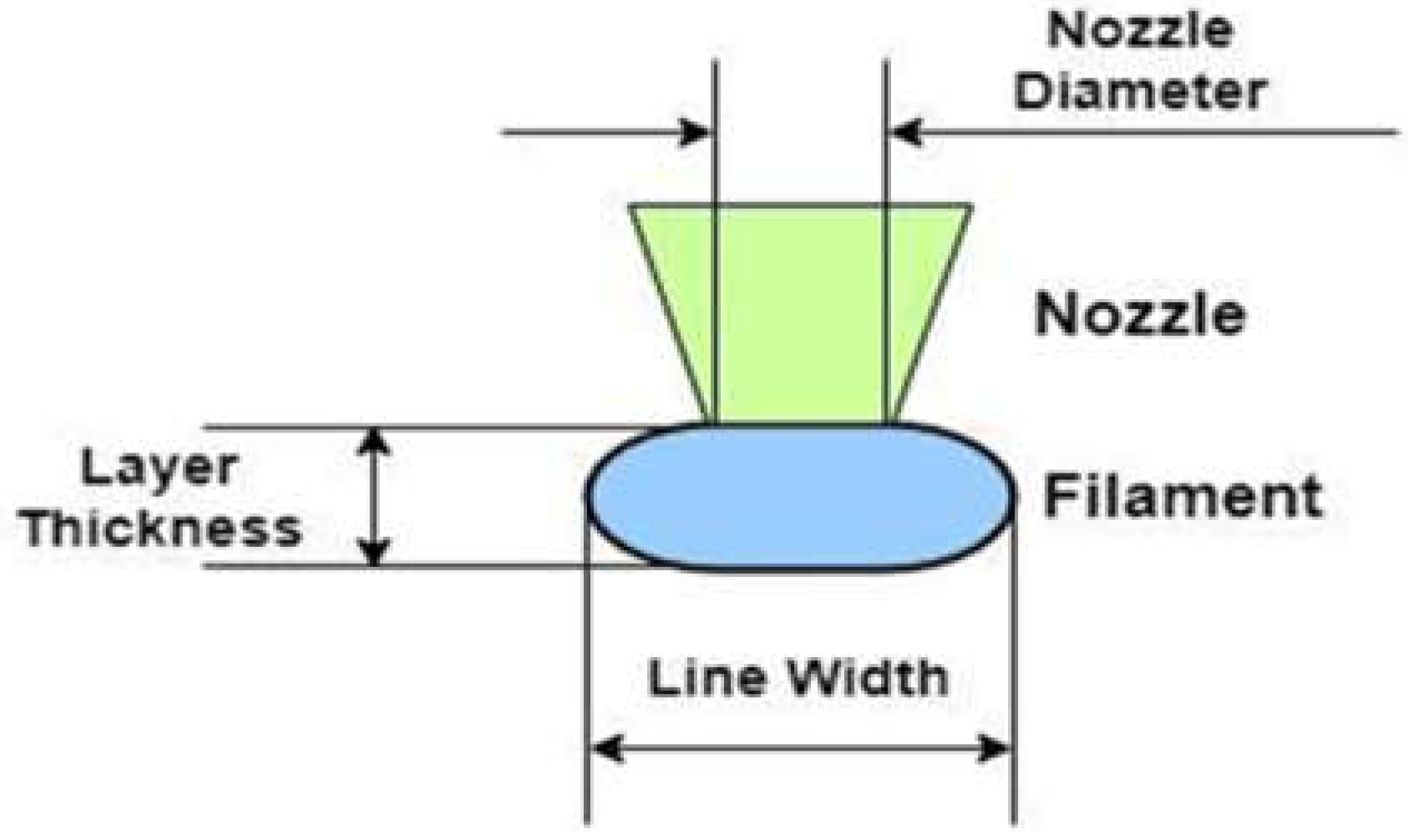

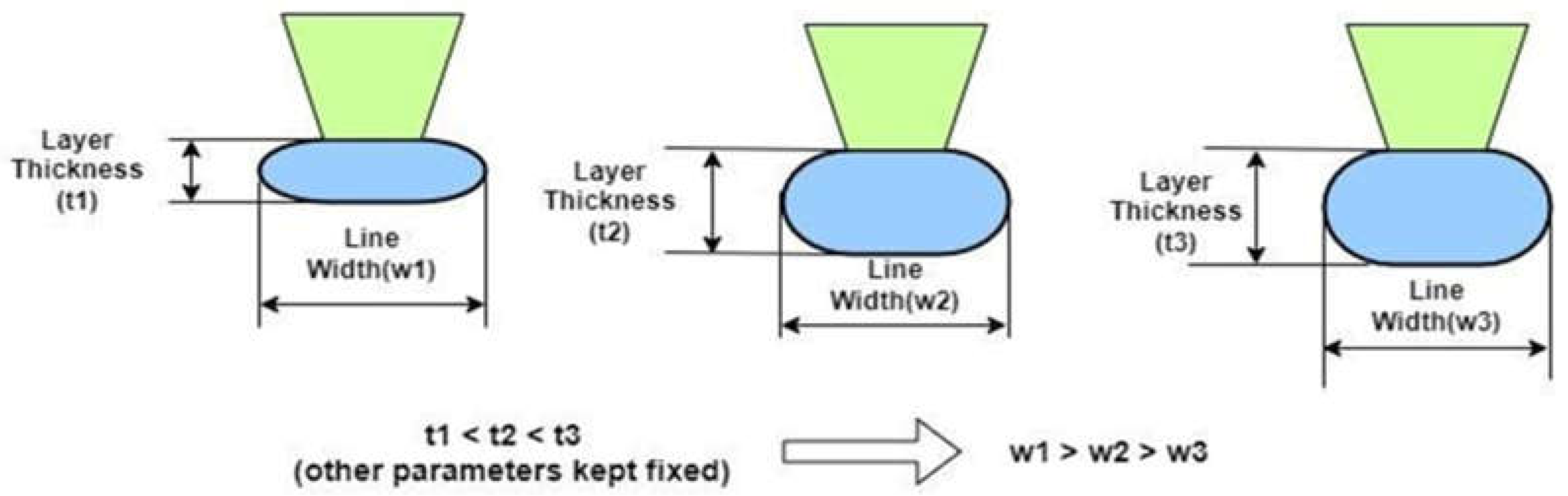

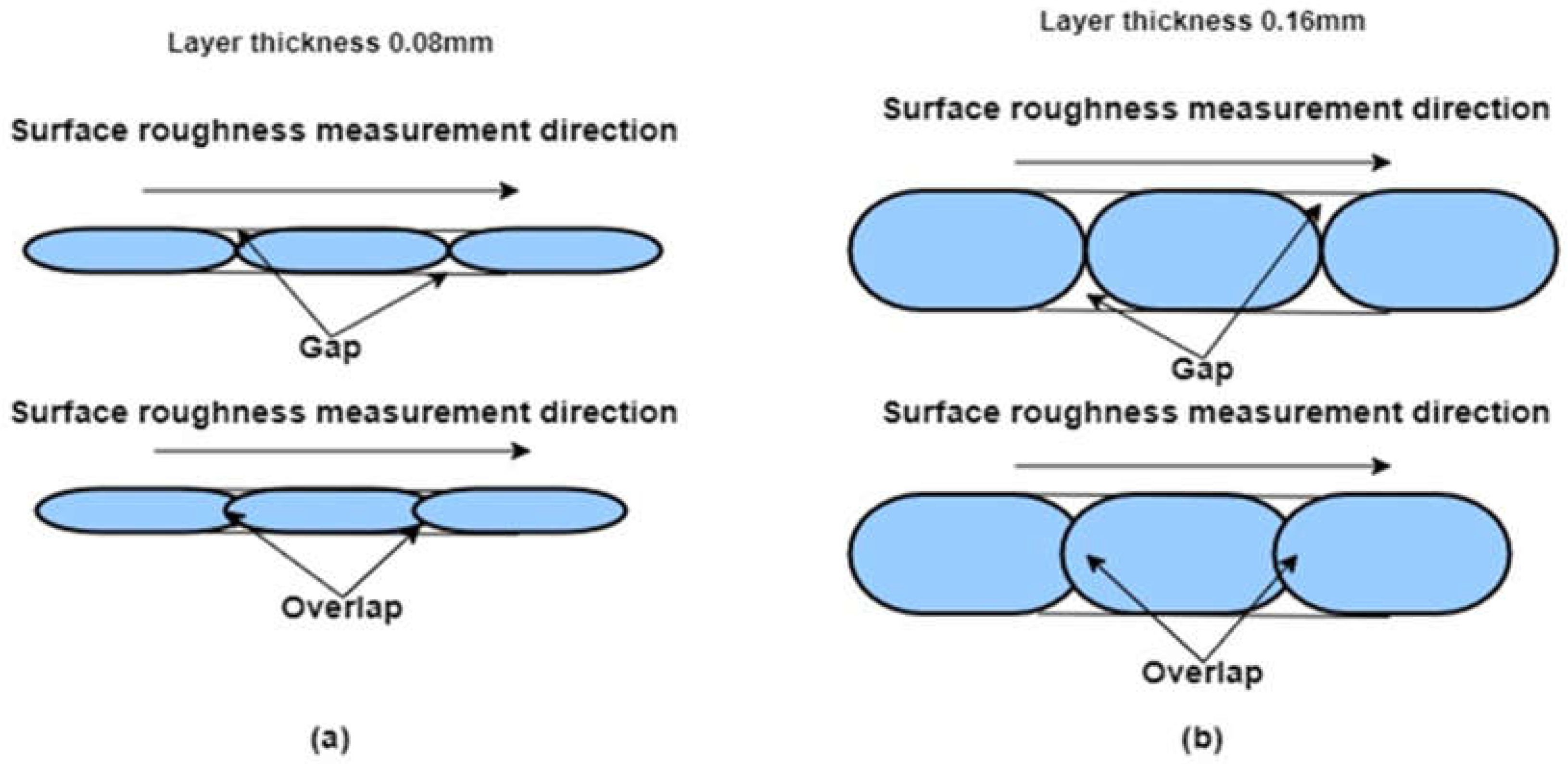

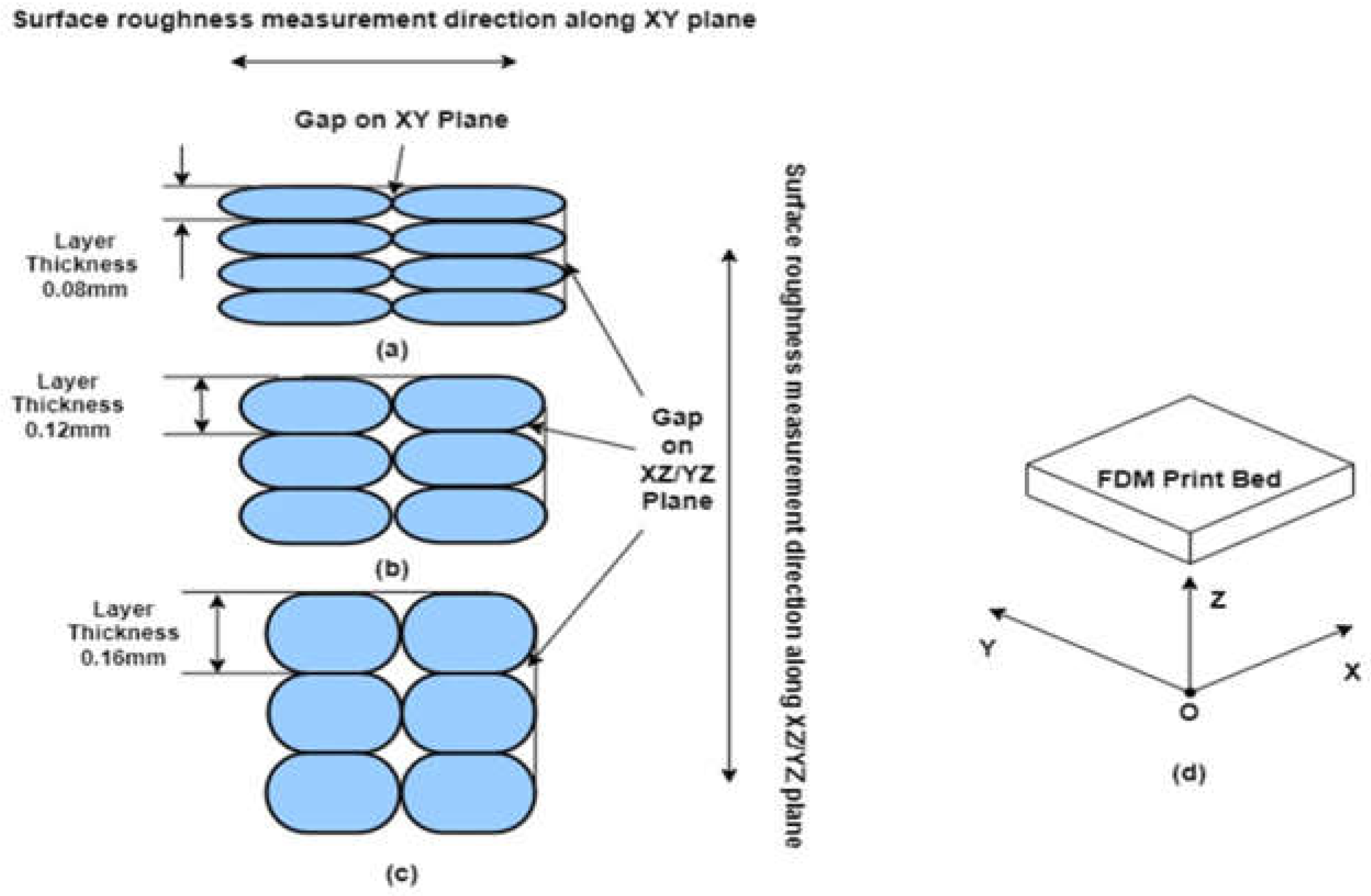

Experimental results of literature show that the surface roughness of FDM printed ABS parts is influenced by controllable printing parameters, i.e., layer thickness [

21,

22,

25], orientation [

21], number of shells [

21], infill percentage [

21,

22], print speed [

22,

25], nozzle temperature [

22,

24,

25], nozzle cross-section [

23].

Table 1.

FDM printed ABS parts as a sacrificial pattern for investment casting.

Table 1.

FDM printed ABS parts as a sacrificial pattern for investment casting.

FDM Printed Pattern

Geometry |

Work Done |

Parameter

Studied |

Suggested/ Optimum

Parameter Value |

Key Findings |

Ref. |

| H-shape |

Hollow and solid patterns were analyzed for dimensional accuracy, surface roughness, cleanliness of mold, pattern collapsibility, and shell cracking. |

Infill density, burnout temperature |

Minimum Dimensional Deviation: hollow pattern

Shell Cracking: hollow pattern, Burnout temperature 550°C-700 °C

Minimum Distortion: Solid pattern |

A hollow pattern shows better performance compared to a solid pattern. No significant change was observed in surface roughness. |

[14] |

| Hip joint |

Wax, ABS, and Wax coated ABS patterns were analyzed for the microhardness of cast components. |

Number of slurry layers, pattern material |

Maximize Micro hardness: wax pattern, eight number of slurry layers |

Process capability: Cp and Cpk are greater than 1 for all three pattern materials. |

[15] |

| Hip prostheses |

Pattern density increased after the VS process, which increased heat input and complexity in ash removal during the burnout stage of investment casting.

Pattern analyzed for change in density after post-processing by vapour smoothing (VS) method. |

FDM parameter: Orientation, density

post-processing parameters: Pre- and post-cooling time, smoothing time, number of cycles. |

Minimize Pattern density: orientation angle (90°), Density(high), precooling time(15min), smoothing time(10s), post-cooling time(20min), number of cycle (1) |

Initial density, orientation, and precooling time have negligible influences on the increase in density after the VS process. |

[16] |

| Dental crown for strategic dog teeth |

Part density, post-treatment temperature, and orientation are used for DoE. Multifactor Optimization has been performed. Optimum parameter settings are found to get optimum dimensional deviation and hardness. |

Pattern density, orientation angle, and post-treatment temperature |

Multifactor optimization gives 70% and 30% weightage to dimensional deviation and surface hardness, respectively.

Optimum values:

Pattern density: low,

Orientation: 180 °

post-treatment temperature: 80 °C |

Only part density affects the dimensional deviation and hardness of the part. Other parameters are found ineffective. |

[17] |

| A sample having faces at different angles between 0° to 128.4° in the step of 12.86°. |

Dimensional accuracy and surface roughness of 3D printed patterns and corresponding investment castings are compared for three different materials. ABS, PLA and PVB for different burnout temperatures ie. 700°C ,900°C and 1100°C. |

Pattern material, burnout temperature, surface angle |

Minimize surface roughness:

Pattern material: ABS,

Surface angle 90 °

Minimize dimensional deviation: ABS |

More dimensional deviation is observed in the case of PVB than in ABS and PLA. On the other hand, shell cracking, shell erosion, and residual ash are observed only in the ABS and PLA cases. |

[18] |

Also, experimental studies proved that nozzle size [

26], layer height [

26,

27], build orientation [

27], infill density [

27,

29], raster angle [

28], print material [

28], infill pattern [

29], wall thickness [

29], number of shells [

29] are influencing the dimensional accuracy of FDM printed ABS parts.

From the previous research work, it can be concluded that influencing printing parameters and their optimum values depend on part geometry, shapes, and complexity [

26,

27,

29]. No generalized optimum parameter value was found applicable to all geometrical shapes and features, so experimentation for required parts is necessary to obtain accurate results.

The basic steps involved in experimental design are understanding the behavior of the process, selecting controllable and uncontrollable factors, and selecting the number of levels and level values. The traditional way of experimenting is the one factor at a time (OFAT) method, which allows us to change only one factor, keeping other factors constant in a single experimental run. This method helps in screening the critical factors amongst all other factors, but it requires many runs to find the optimum value of critical factors. This issue can be solved using the Design of Experiment (DoE) method. This method allows us to change multiple factors in a single experimental run, and with the help of a smaller number of experimental runs, optimum values of critical factors can be achieved [

30]. Researchers compared the most popular DoE methods like Response Surface Methodology (RSM), Full Factorial Design, Screening Design, and Taguchi Design, which concluded that Taguchi Design is the most efficient and adaptable DoE method for researchers and scientists. This method works on an orthogonal array design, which distributes all factor levels in a balanced way over the number of experimental runs. This feature reduces the number of experimental runs required in DoE without compromising the accuracy of the results [

31].

Several experimental investigations have been done by researchers to understand the impact of FDM printing parameters on dimensional accuracy and surface roughness of ABS parts and to find optimum parameter values for optimal quality.

Optimum parameter values are different for different materials, shapes, sizes, and geometry. There is no generalized set of optimum parameter values which apply to a wide range of applications.

Researchers must perform their experimental study to find optimal print parameter values for FDM printed parts having medium to high complexity level geometry.

Very little research has been done for FDM printing of sacrificial patterns of an impeller used in RIC.

Taguchi Design is the most efficient method for screening the factors with fewer experimental runs.

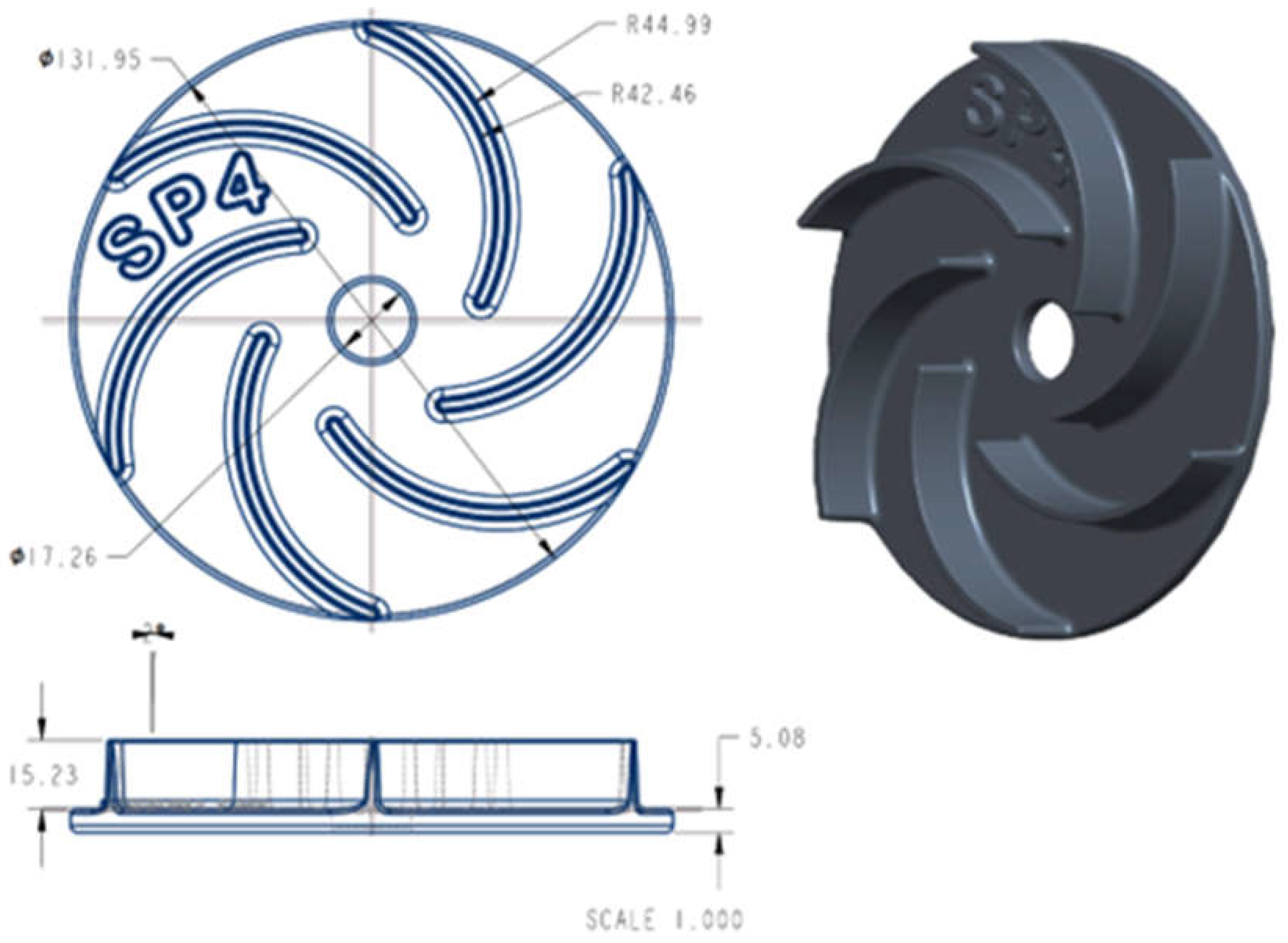

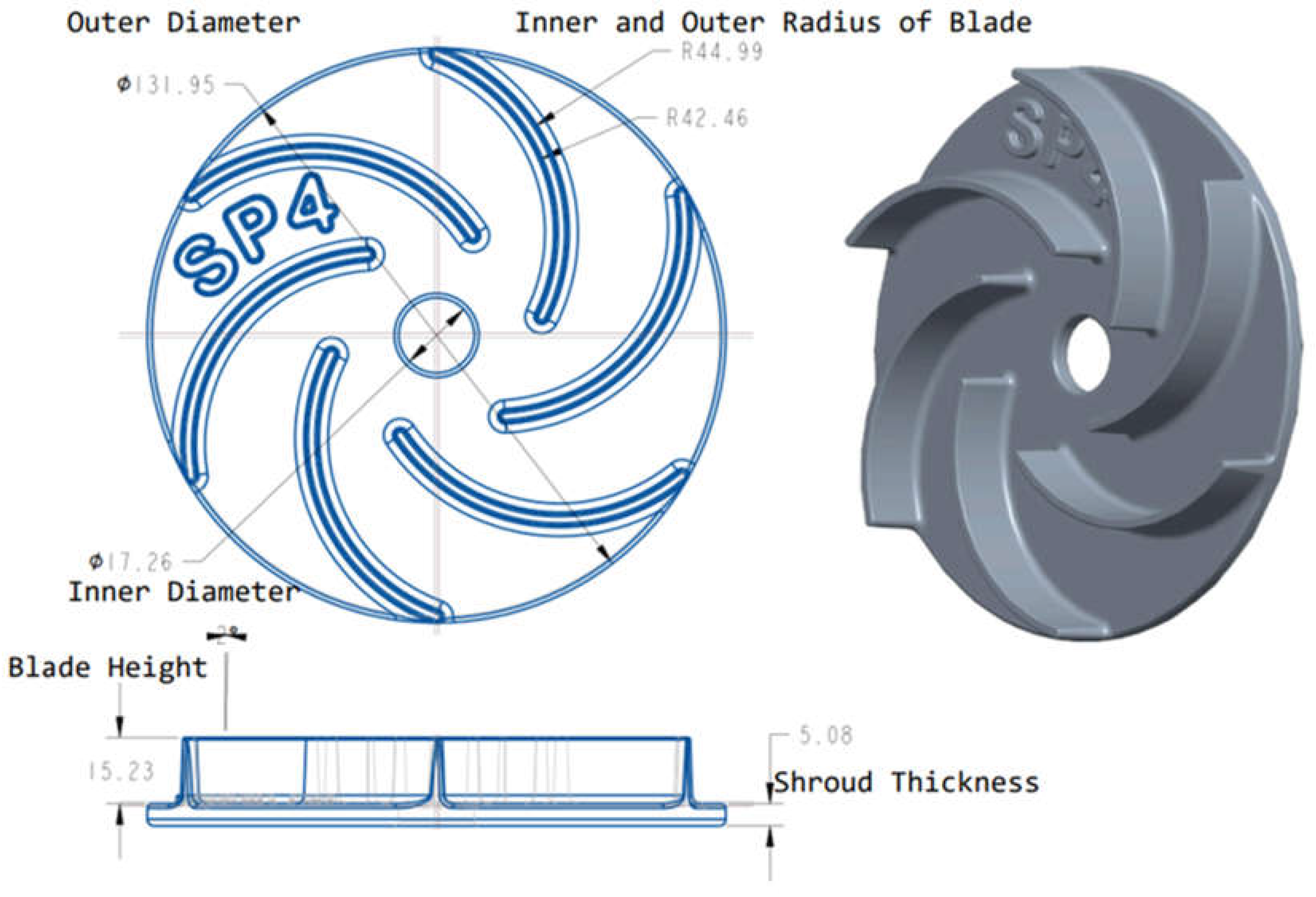

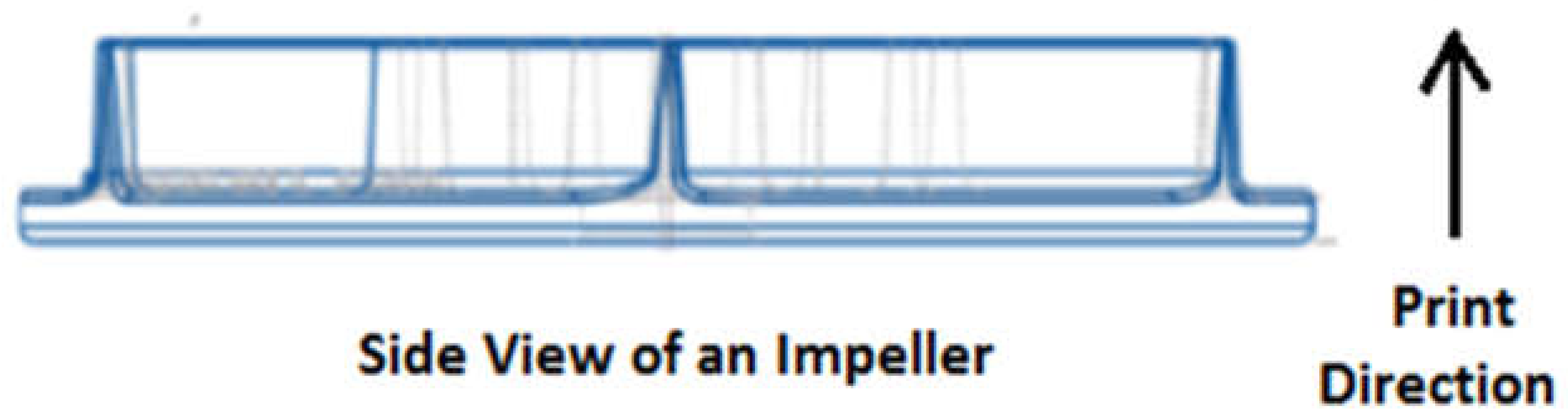

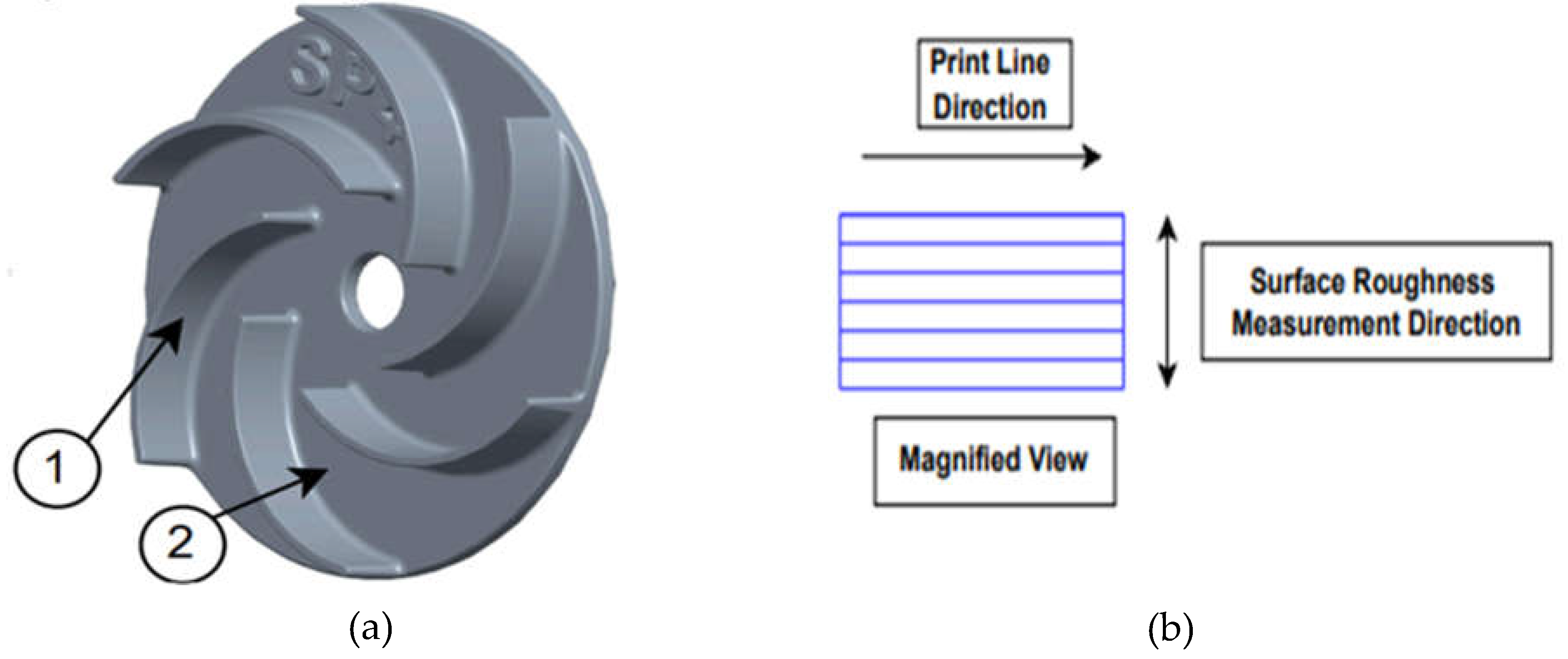

A single shrouded, semi-open type impeller of a centrifugal pump has been selected for this experimental study. The impeller geometry includes several critical geometrical features, such as thin walls (blade thickness), curved surfaces (blades), and varying dimensions (inner and outer diameters). ABS was selected as the printing material, and impeller patterns were printed on the FDM machine according to the Taguchi Design of Experiment (DoE) method. Dimensional deviation and surface roughness measurements were performed, and a detailed analysis of the results was conducted to understand the influence of printing parameters on part quality at various geometrical features of the impeller.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. 3D CAD Modeling of an Impeller

A single-shrouded, semi-open type impeller of the centrifugal pump was selected for this experiment. The design specifications were as follows: 6 blades, a 50 mm inlet diameter, a 130 mm outlet diameter, a 20° blade discharge angle, a 35° blade inlet angle, a 15 mm blade height, and a 2.5 mm blade thickness [

32]. Since investment casting undergoes shrinkage during the solidification of molten metal, it is necessary to prepare sacrificial patterns oversized by applying a shrinkage allowance [

33]. After consulting with industry experts, the shrinkage allowance was applied to the impeller pattern. A three-dimensional model of the impeller was created using CREO Parametric, a 3D modeling software. The 2D and 3D drawings of the impeller, with final dimensions after applying the shrinkage allowances, are provided in

Figure 3. Paper size: US Letter (8.5″ × 11″ or 21.59 cm × 27.94 cm).

Figure 3.

2D and 3D drawing of an impeller using CREO parametric.

Figure 3.

2D and 3D drawing of an impeller using CREO parametric.

2.2. Material and Equipment

The 3D CAD file was saved in STL file format and sliced using Ultimaker Cura, an open-source slicing software with appropriate parameters. The FDM technique of additive manufacturing was used to produce the impeller pattern. The pattern was 3D printed with Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) at Tri-Aayam Engineering Solutions Pvt. Ltd., 3D Printing, Ahmedabad. The important properties of ABS are listed in

Table 2, and the specifications of the FDM machine are provided in

Table 3.

Table 2.

Properties of ABS.

Table 2.

Properties of ABS.

| Property |

Print

Temperature |

Print Bed

Temperature |

Bed Preparation |

Density |

Ultimate Tensile

Strength (UTS) |

| Value |

210°C – 250°C |

80°C – 110°C |

Apply glue stick |

1.0 to 1.4 g /cm³ |

37 to 110 MPa |

Table 3.

Specifications of FDM.

Table 3.

Specifications of FDM.

| Particular |

Detail |

| Maximum Nozzle temperature |

340 °C |

| Maximum Bed temperature |

140°C |

| Nozzle size |

0.4 mm |

| Build Volume |

300mm x 300mm x 300mm |

| Maximum Printing speed |

600mm/sec |

2.3. Experimental Design

This experimental investigation was conducted to understand the influence of FDM printing parameters on the dimensional accuracy and surface quality of various geometric features of an impeller. Taguchi's Design of Experiment (DoE) method was used for the experimental design in this research. This method is a robust design that identifies the most influential parameters and their interaction effects with a minimum number of experimental runs. It is particularly suitable when there are a few parameters and interactions involved in the process [

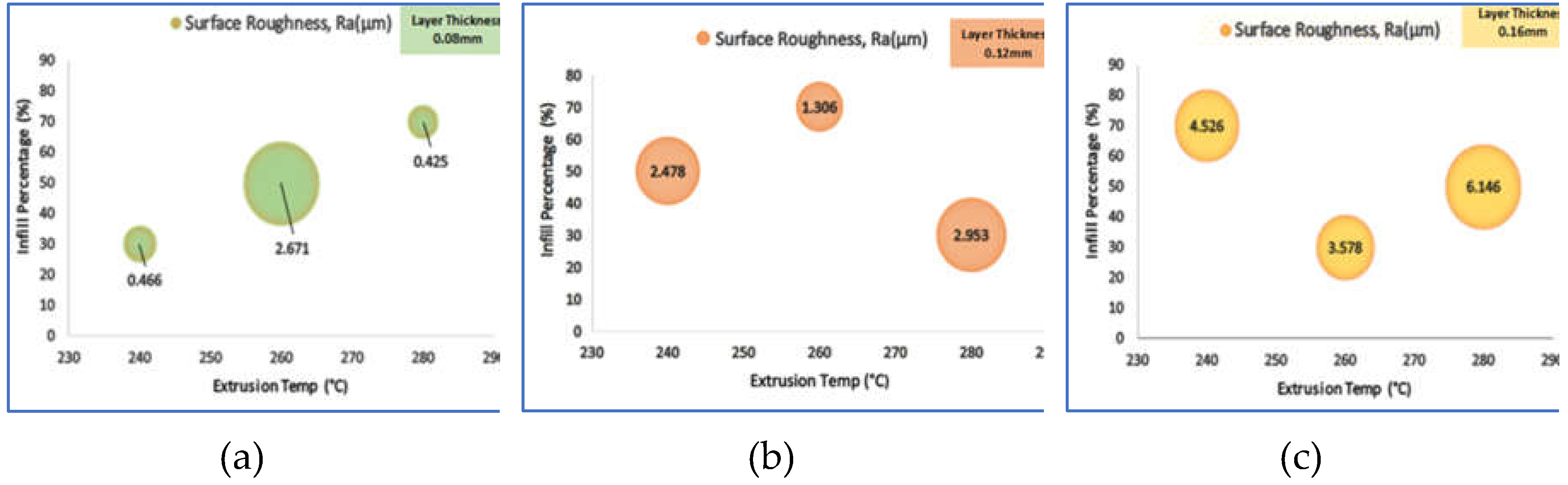

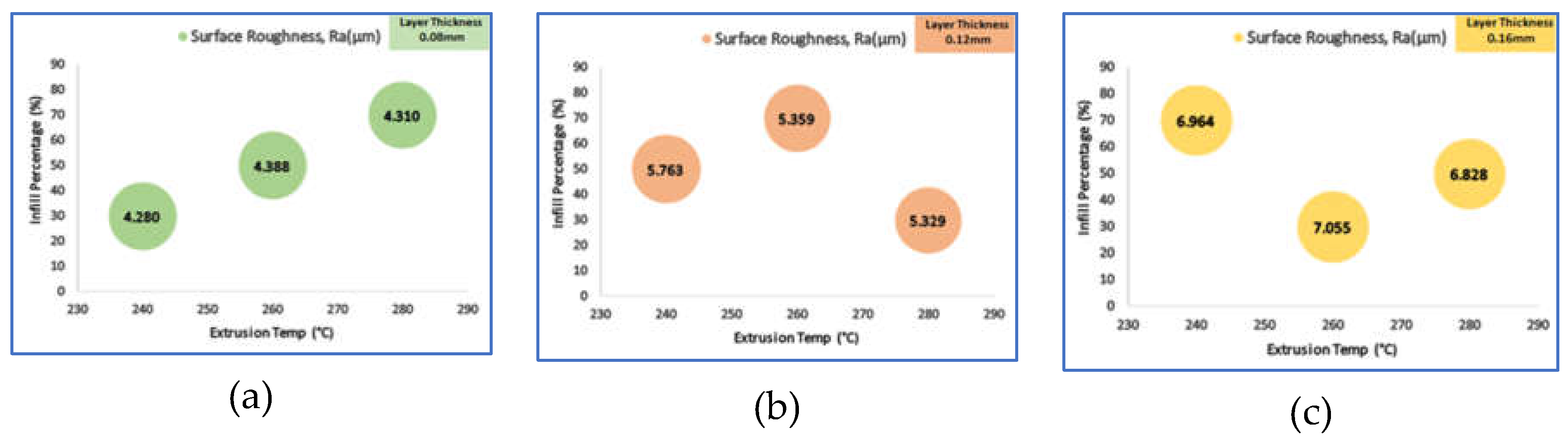

31]. The present study aimed to investigate the impact of three printing parameters: layer thickness, extrusion temperature, and infill percentage. The experimental investigation was conducted using the Taguchi orthogonal array L9(3^3) DoE method, which involves three factors and three levels for each factor. Specifically, 3^3 was selected for nine runs. The systematic approach helped identify the criticality of the parameters and determine their impact on printing quality. By analyzing the results of the samples, the study findings can help improve the quality of the printing process and make it more efficient. Minitab 20.0 was used to generate the experimental design matrix.

Three FDM printing parameters, i.e., layer thickness, extrusion temperature, and infill percentage, were used for this experiment. Factors and their corresponding level values are shown in

Table 4.

Table 5 and

Table 6 show the details of the experiment run order and corresponding factor level settings as per Taguchi L9(3^3) orthogonal array.

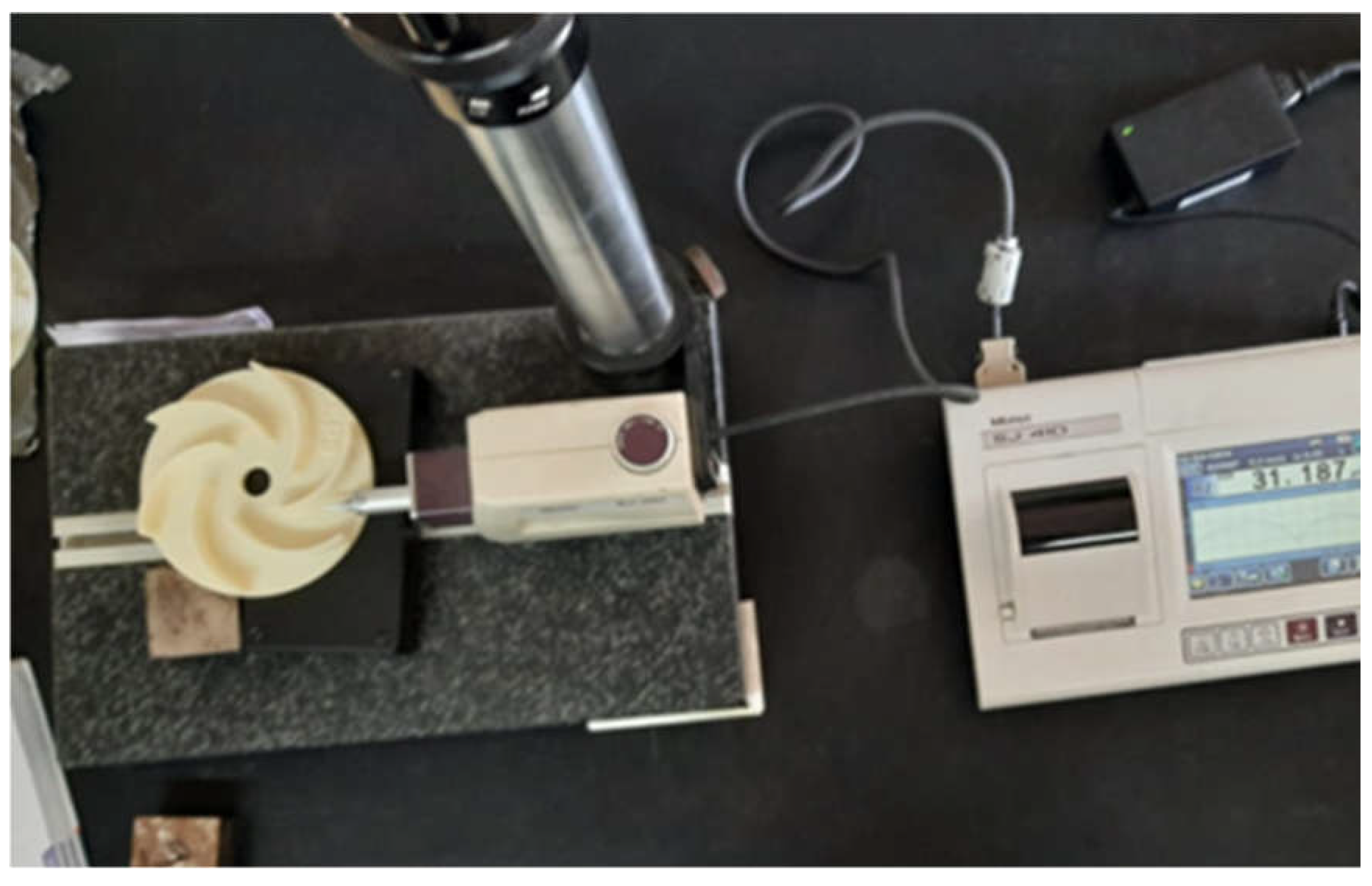

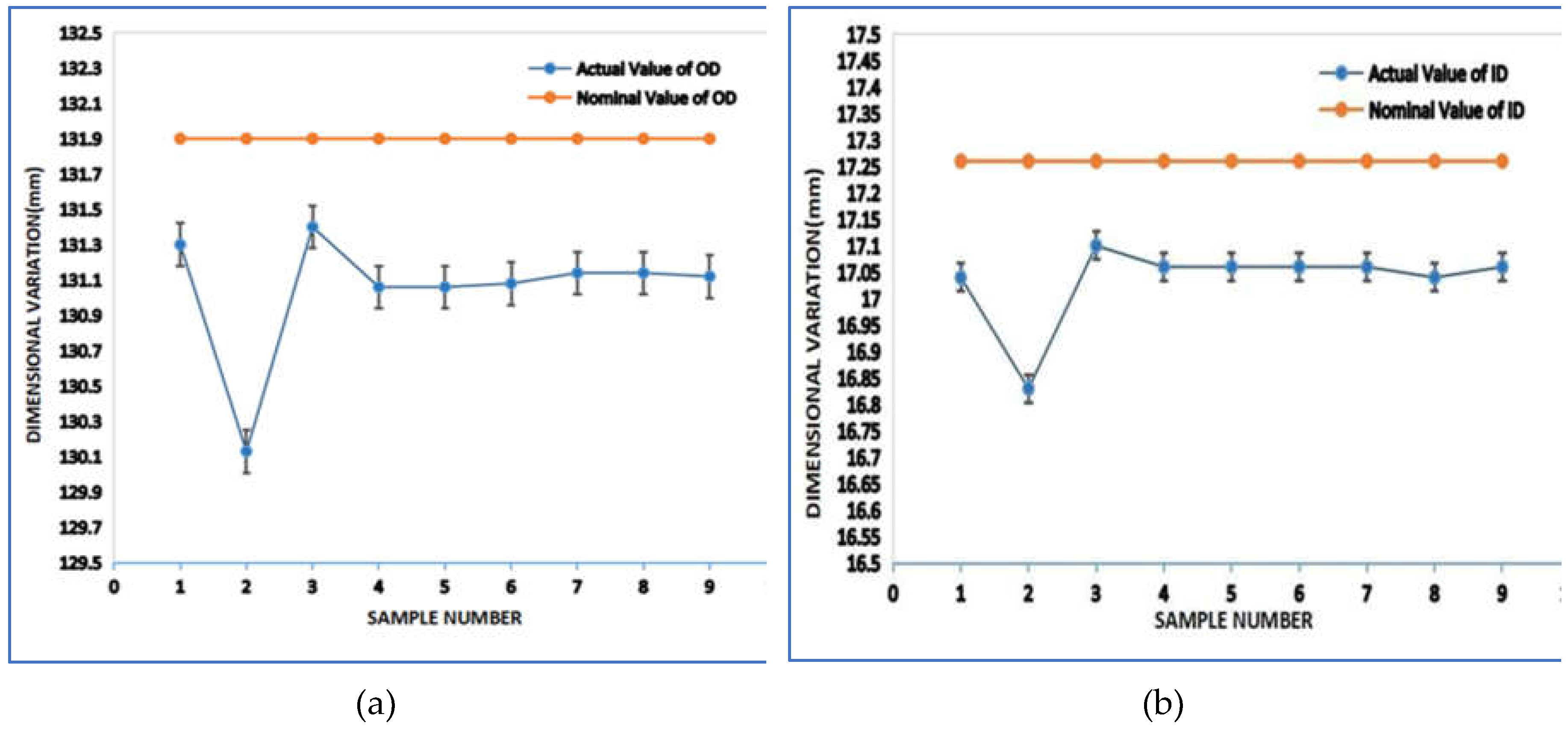

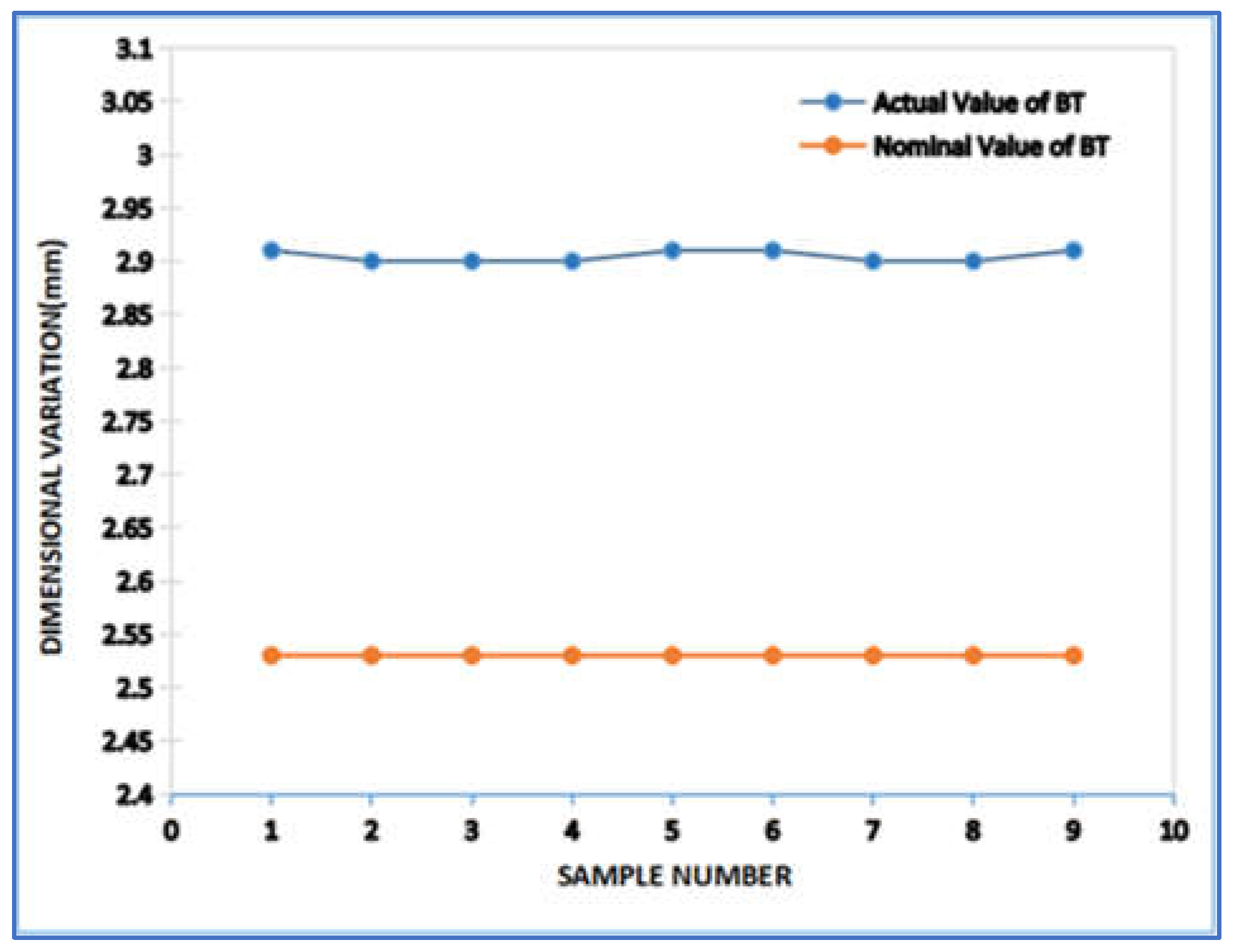

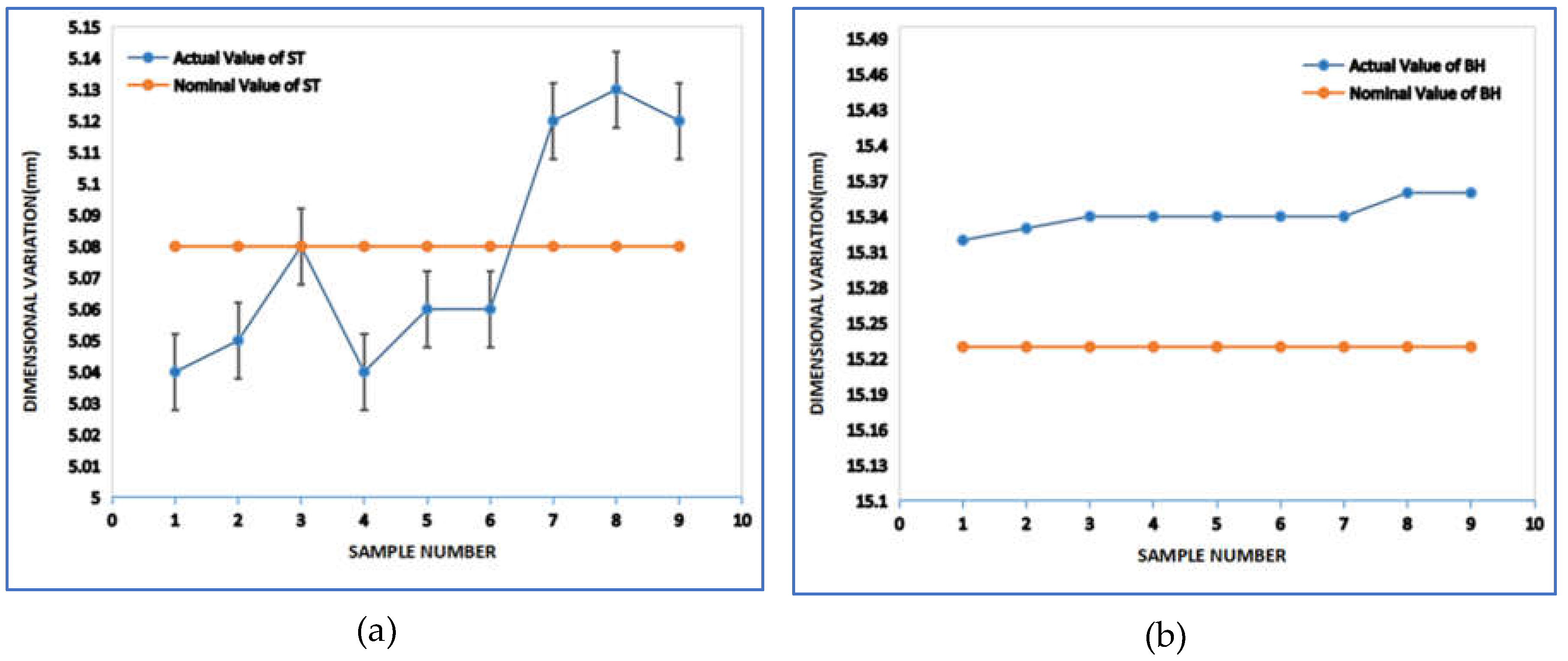

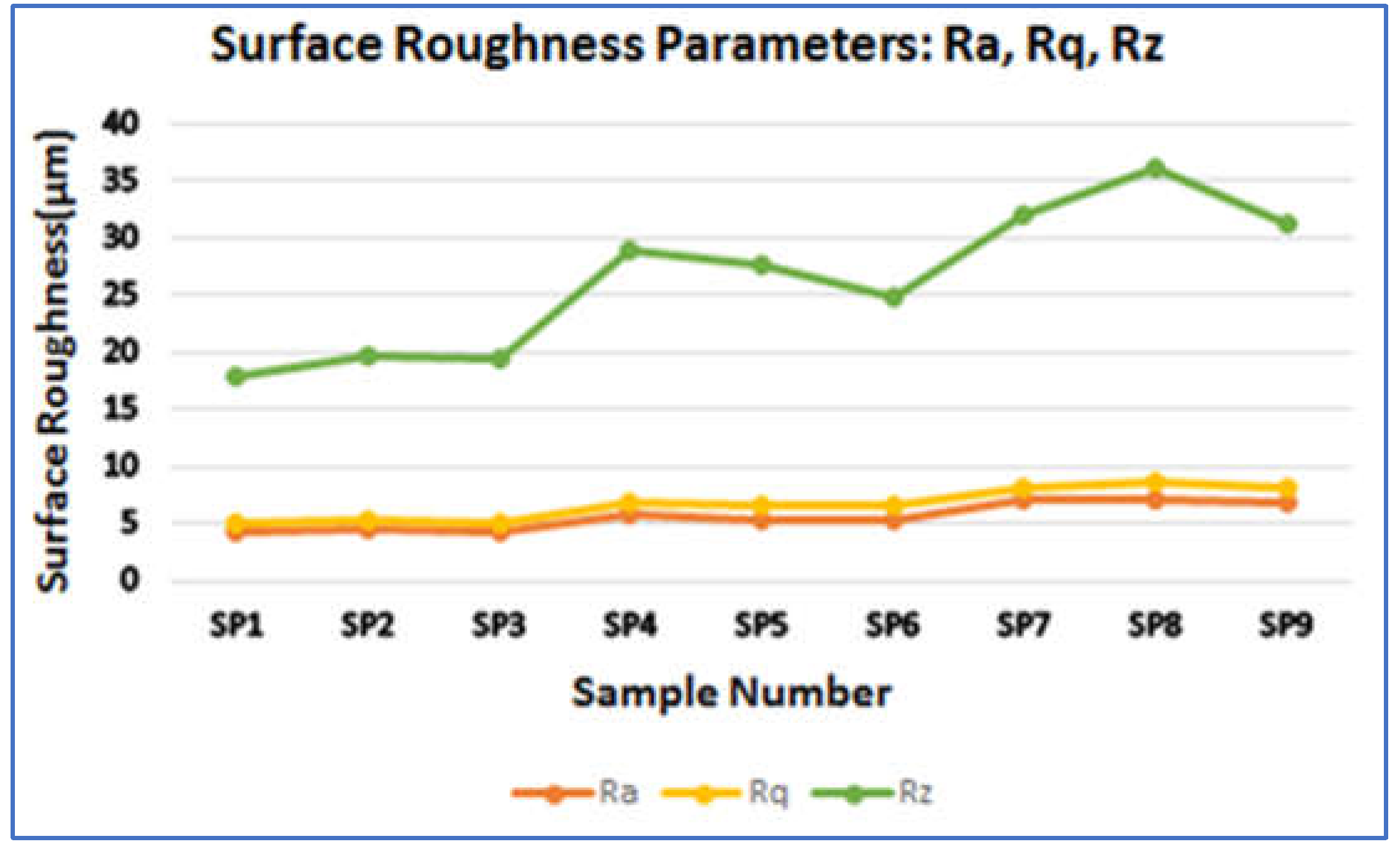

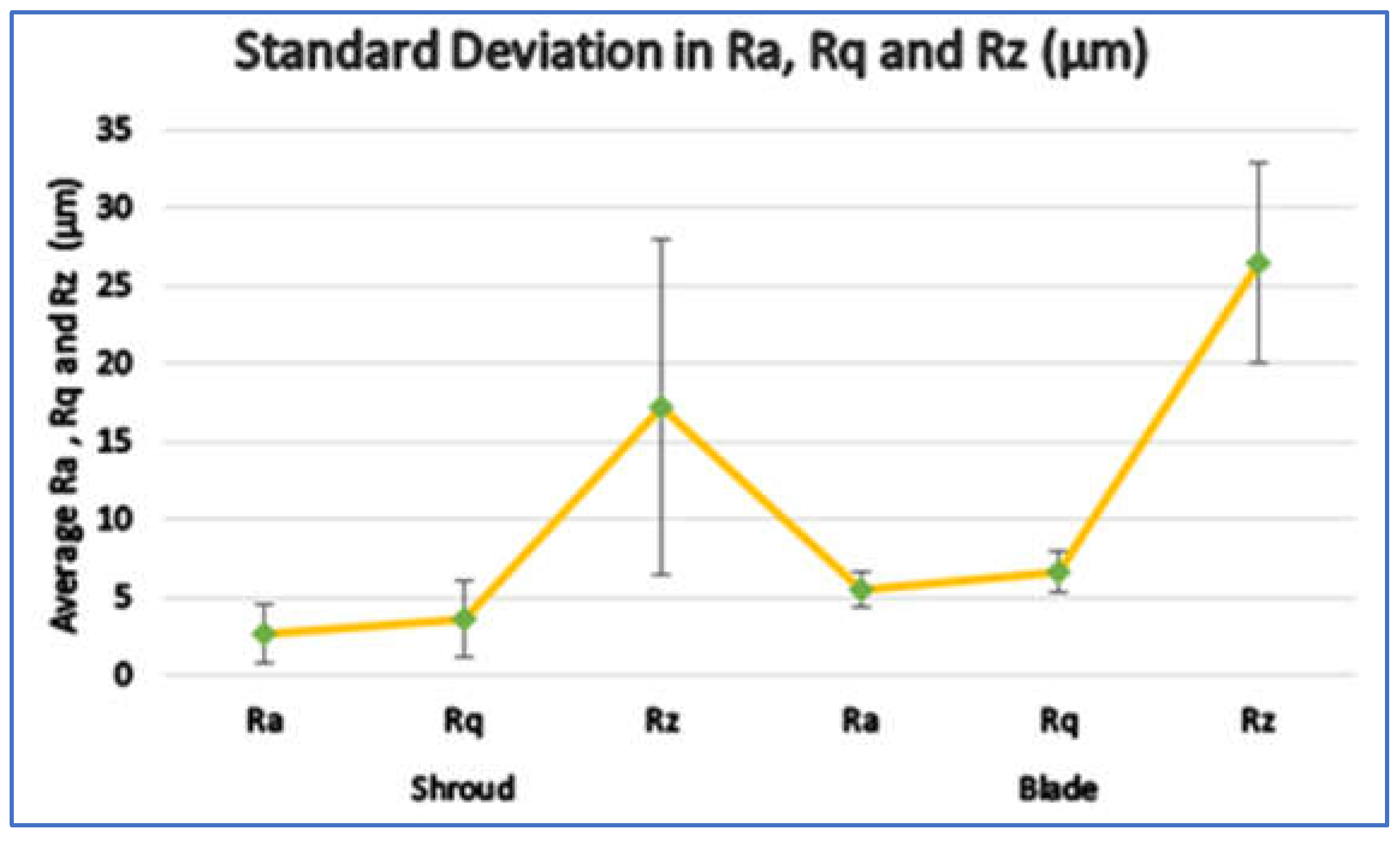

2.4. Dimension and Surface Roughness Measurement

Mitutoyo vernier calipers and a micrometer screw gauge were used to measure the dimensions of the 3D-printed impellers. We measured the dimensions at five different locations on the impeller: 1) Outer Diameter, 2) Inner Diameter, 3) Blade Thickness, 4) Shroud Thickness, and 5) Overall Height. For each location, five readings were taken, and the average value was recorded for further analysis.

Figure 4.

(a)Vernier caliper and (b)Micrometer screw gauge.

Figure 4.

(a)Vernier caliper and (b)Micrometer screw gauge.

Figure 5.

Mitutoyo SJ 410 surface roughness tester.

Figure 5.

Mitutoyo SJ 410 surface roughness tester.

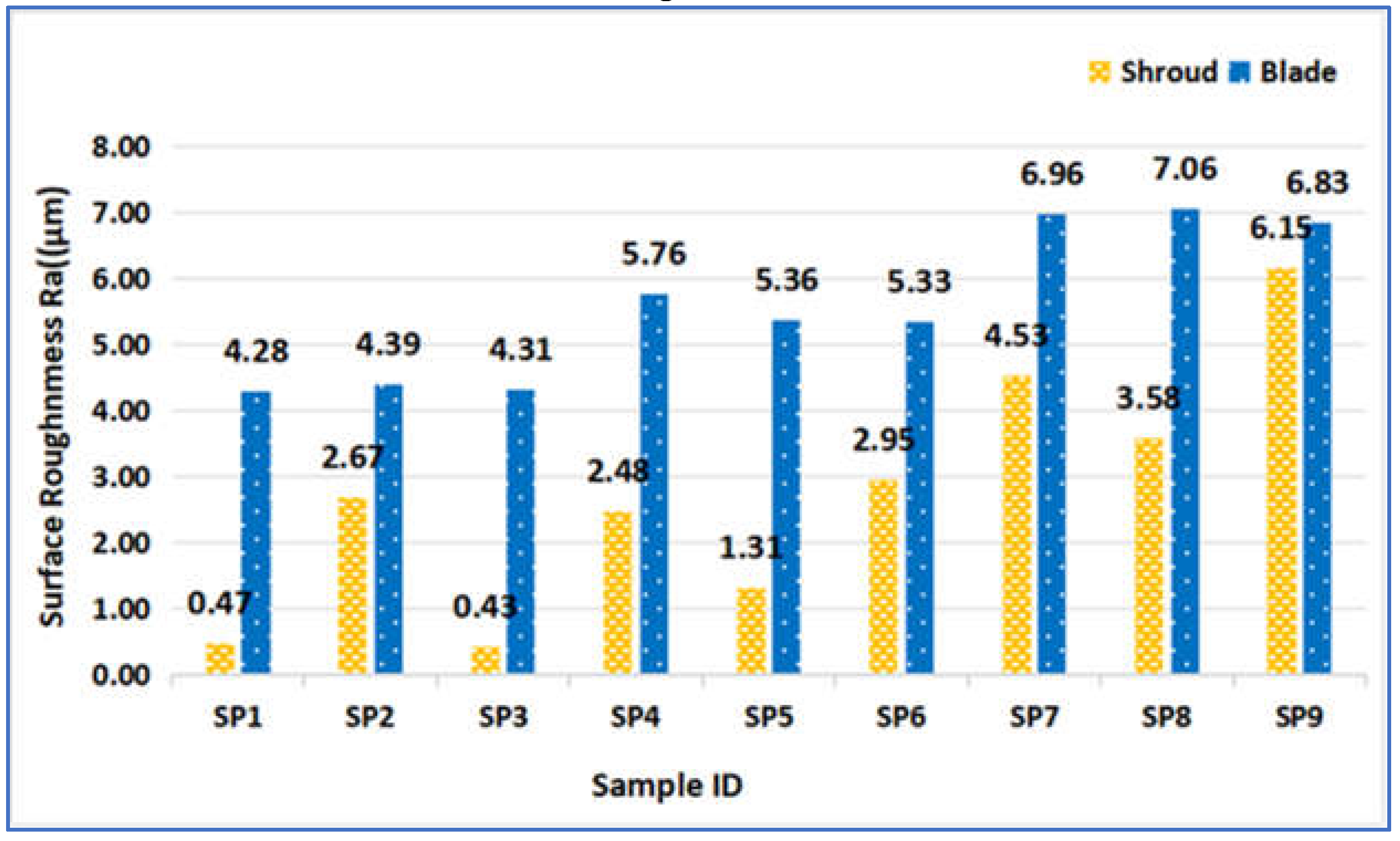

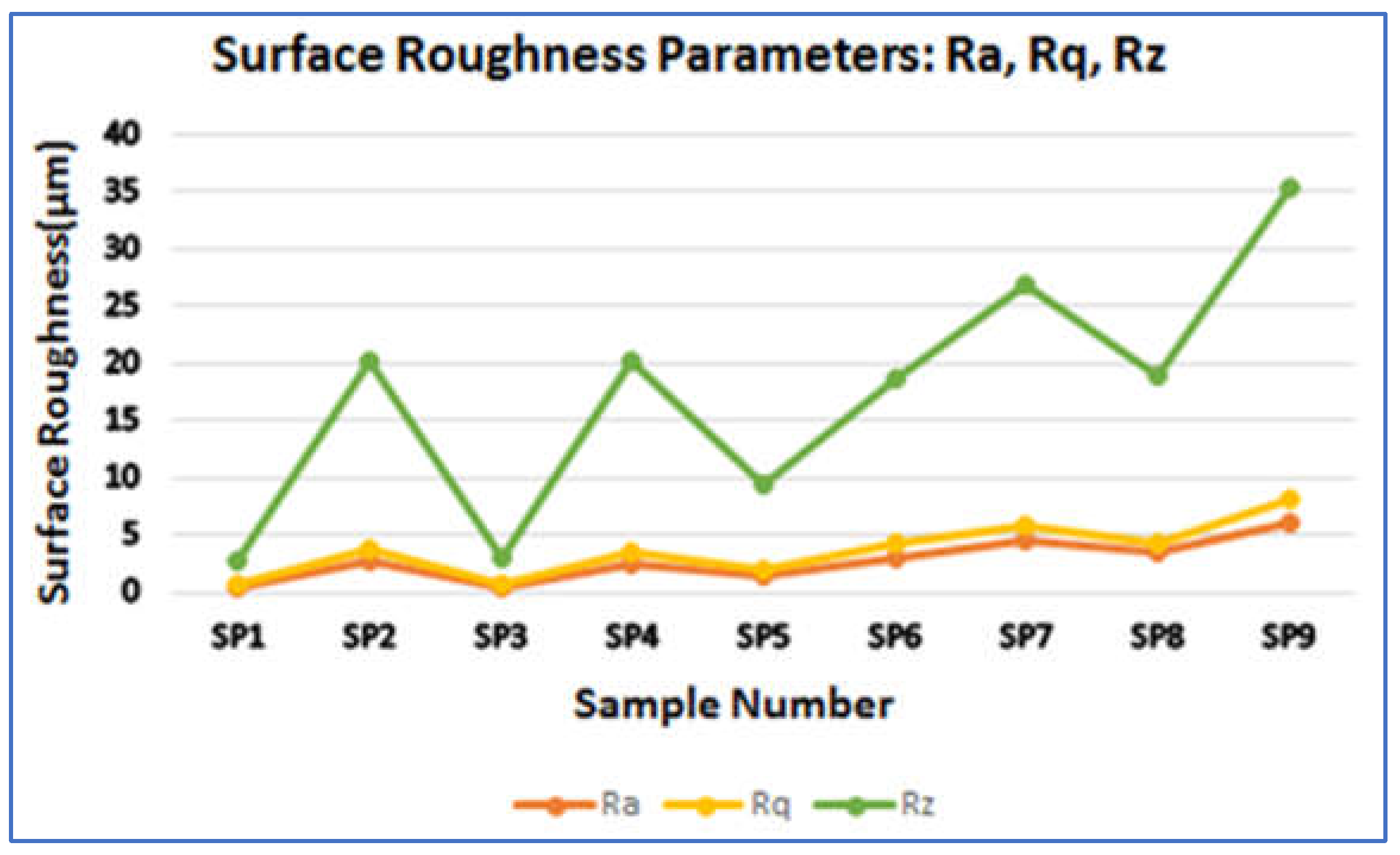

Shroud and blade surface roughness values of an impeller influence the efficiency of the centrifugal pump [

34]-[

36]. A Mitutoyo SJ 410 surface roughness tester was used to measure various surface quality indicators, including Ra (the absolute average of the surface profile), Rq (the root mean square of the surface profile), and Rz (the average peak-to-valley roughness). For more details on roughness parameters, readers can refer to [

37]. Three measurements were taken at both the shroud and blade, and the average values were recorded for further analysis.