1. Introduction

During evolution, animals acquired efficient ways to sense and respond to internal changes, including selective and adaptive barriers. Circumventricular organs are medial brain structures open to the circulation that allow transduction of peripheral signals to brain nuclei and, for secretory circumventricular organs, release of efferent neuroendocrine messages [

1]. At the base of the hypothalamus, a circumventricular organ, the ME, has a ventricular wall made of β-tanycytes, elongated cells with an apical body exposed to the cerebrospinal fluid and a long basal process whose ramifications approach portal blood vessels [

2]. ME (lateral β1 and central β2) tanycytes form barriers between the cerebrospinal fluid and the ME parenchyma, or between the ME itself and the arcuate nucleus (ARC) parenchyma [

3]. The ME is irrigated mostly by the superior hypophyseal arteries derived from the carotid artery, forming fenestrated capillaries in this region [

4]. This anatomical configuration makes the ME sensitive to, and permissive to the passage of, peripheral metabolic signals such as thyroid hormones (TH), leptin, glucose, ghrelin, and other nutritional information into the third ventricle or nearby nuclei such as the ARC of the hypothalamus; some of this information is transduced to distant hypothalamic nuclei like the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH) [

5,

6]. On the other hand, efferent signals generated by hypophysiotropic neurons are released into the proximity of fenestrated capillaries of the ME [

7] and transported by portal vessels to the pituitary, where these signals influence the secretion of anterior pituitary hormones into the peripheral circulation [

8].

The control of the HPT axis by tanycytes illustrates the impact of ME cellular components over energy balance. Axons and terminal buttons from hypophysiotropic TRH (pGlu-His-Pro-NH2) neurons of the PVH are abundant in the external zone of the ME [

9,

10]. Once released, TRH diffuses into the portal capillaries and is transported to the anterior pituitary, where it stimulates the release of thyrotropin (TSH) into the general circulation and consequently TH secretion from the thyroid [

11,

12]. Circulating TH acts as a negative feedback signal at different levels of the HPT axis [

13]. While 30% of TH secreted by the thyroid corresponds to 3,3’,5-triiodo-L-thyronine (T3), in addition circulating thyroxine (T4) can be converted to T3 by tissue deiodinases; in β2-tanycytes, deiodinase type 2 (DIO2) produces T3 that is taken up by nerve terminals of TRHergic hypophysiotropic neurons and retrogradely transported into the PVH where it exerts negative feedback control of

Trh expression [

11,

14]. On the other hand, β2-tanycyte end-feet are in close contact with TRH terminals [

15] and may also contribute to shape TRH pulses, since glutamate, co-released with TRH, induces endocannabinoid signaling by tanycytes that feedbacks to reduce TRH release [

16].

Tanycyte molecular machinery is remarkable for the abundance of TH transport, biotransformation and sensing proteins (

Slc16a2,

Slco1c1,

Crym,

Dio2,

Thra and

Thrb) and of the TRH-DE (EC 3.4.19.6), a narrow-specificity omega ectopeptidase that, in the extracellular space, hydrolyses TRH to products inactive on the TRH receptors [

15,

17].

Trhde expression in β2-tanycytes could influence the bioavailability of TRH to the pituitary, since inhibition of ME TRH-DE activity enhances TRH recovery from ME explants and the peripheral injection of an inhibitor that reduces ME TRH-DE activity enhances the secretion of TSH induced by 1 h cold stress in male rats reared in standard conditions [

15]. Furthermore, the activity of TRH-DE in the ME is enhanced by TH, fasting and TRH [

15,

18,

19], suggesting it may adjust TRH extracellular half-life. Finally, activation of the Gqα1 pathway in tanycytes, a pathway that couples to TRH receptor 1 (TRH-R1) [

20,

21], increases the contact of tanycytes end-feet on portal vessels, while its inhibition enhances the secretion of TSH induced by chemogenetic stimulation of PVH TRH neurons [

19]. These data suggest that either TRH-DE activity and/or end-feet positioning on portal capillaries is critical to adjust the output of TRH into the portal capillaries when TRH neurons are active. TRH-DE might thus be a target for the treatment of some pathologies derived from malfunction of the HPT axis [

22], but the effects of a long-term perturbation of TRH-DE activity on HPT axis homeostasis are unknown.

To evaluate the impact of ME TRH-DE activity on basal HPT axis function in rodents housed in standard conditions, we compared the locus of expression of TRH-DE with that of TRH terminals in the ME of adult rats, determined the status of the HPT axis in adult mice homozygous or heterozygous for a global inactivation of Trhde and, analyzed the impact of viral alteration of ME TRH-DE activity on HPT axis activity in adult rats.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Rodents were bred at the Institute’s animal house, a specific pathogen free facility. They were kept under controlled temperature (21 ± 1 °C), humidity (30-55%), lights on from 7:00 to 19:00 h, a standard diet (Teklad TD.2018SX chow [Envigo]) and purified water ad libitum.

B6;129S5-Trhde

tm1Lex/Mmucd mice (RRID:MMRRC_032690-UCD) are a strain in which

Trhde exon 1 (NCBI accession: NM_146241.1) is deleted and substituted by a β-galactosidase (β-gal) cassette by homologous recombination. The mice [

23] were obtained from the Knockout Mouse Project, KOMP Repository, University of California at Davis. We back crossed the original mutation to the C57BL/6NJ background, obtained from Jackson Laboratories, for up to 11 generations of mice, avoiding mixing parental lines or crossing relatives. C57BL/6NJ mice bearing both Trhde

tm1Lex alleles are abbreviated

Trhde knock out (KO) mice. Pups were genotyped, sexed after weaning, grouped 2-4 of the same sex per cage. They were sacrificed when being approx. 2 months old, between 10-14 h.

The Wistar rat colony was expanded from pairs of 3-4-month-old non-sibling male and female rats from Charles River (Wilmington MA), carefully recording crossings to keep each line independent and avoid inter-crossing. Pups were culled to 10 per mother and animals were sexed after weaning to keep groups of 5 male rats per cage. Male rats were grouped in pairs starting at one month of age and they were subjected to surgical or histological procedures when they reached 245-260 g body weight (approx. 2 months old) and sacrificed 2-3 weeks later, between 9 and 11 h.

Experimental groups were formed by selecting each member from different mothers to avoid siblings in a group. Animals were treated according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th edition), National Research Council of the National Academies of USA, and the Official Mexican Norm for production, care and use of laboratory animals (NOM-062-ZOO-1999). Experiments and animal care were approved by the Institute Biosafety (application number 241010) and Bioethics (application number 276) Committees. The number of animals used in each group and experiment is indicated in

Sup. Table S1.

2.2. Histochemistry for β-gal in Mouse Brain Slices

Mice were injected i.p. with a lethal dose of pentobarbital sodium (210 mg/Kg, Sedalphorte, Salud y Bienestar Animal SA de CV, Mexico) and perfused first with 20 mL of PBS 0.01 M pH=7.4 supplemented with 15 000 U/L heparin sulfate, followed by 30 mL of paraformaldehyde (PFA, 4%). Brains were excised and post-fixed with PFA (4%) at 4 °C for 6 h, then cryoprotected in sucrose solutions (from 20 to 30% until brain sinking), frozen with powdered dry ice and stored at -80 °C until sectioning 25 µm slices. For detection of β-gal activity, slices were washed 3 times with buffer (MgCl

2 2 mM, sodium deoxycholate 0.01%, NP-40 0.02% in PBS 0.1 M, each for 10 min at room temperature) and then stained for at least 6 h with K

3[Fe(CN)

6] 5 mM, K

4[Fe(CN)

6] 5 mM, X-gal 1 mg/mL [

24]. Slices were post-fixed with PFA 4%, dehydrated and mounted with resin on a slide. Standard bright light observation of blue precipitate was made with an Axioscop Zeiss epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss Neofluar 20X/0.58 and 40X/0.75).

2.3. Immunofluorescence Detection of Vimentin and TRH-DE in Rats, and β-gal and Vimentin in Mouse Brain Slices

Rodents were anesthetized with intraperitoneal (ip) pentobarbital sodium (rats: 120 mg/Kg) and perfused with PBS 0.01 M pH=7.4 supplemented with 15 000 U/L heparin sulfate (50 mL for rats, 20 mL for mice) and then with PFA 4% (200 mL for rats, 50 mL for mice). Brains were processed, sliced and stored as indicated above. Coronal sections of 25 μm (from bregma -1.4 to -3.6 mm in rats and bregma -1.58 to -2.3 mm in mice [

25,

26] were made in a cryostat and cryoprotected in antifreeze solution (glycerol 30% and ethylene glycol 30% in PBS) at -20 °C until immunofluorescence processing. Sections were washed with PBS 0.01 M pH=7.4 and then incubated with NaBH

4 0.1% for 15 min to remove autofluorescence, washed with PBS 0.01 M and then blocked and permeabilized with a mixture of donkey normal serum (5%) and Triton X-100 (0.05%) in PBS 0.01 M for 3 h. Sections were incubated with primary antibodies (sources and dilutions listed in

Sup. Table S2), most of them diluted in PBS 0.01 M with Triton X-100 0.05% overnight, except for the TRH-DE antibody which was diluted in PBS 0.01 M. Sections were then incubated with a secondary antibody (

Sup. Table S2) and finally contrasted with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and mounted with Citifluor montage medium (EMS Acquisition Corp., Hatfield, PA). Sections incubated with TRH-DE and β-gal antibodies were visualized in an Axioscop Zeiss epifluorescence microscope (magnifications with Zeiss Neofluar 20X/0.58, 40X/0.75) coupled to a ProgRes CF camera (Jenoptik Optical Systems, GmBH), using Morpho Pro software (Explora Nova, La Rochelle, France) with exposures ranging from 1000 to 4000 ms and gain=1. For vimentin extension analysis, mouse brain slices were observed in a confocal microscope (Olympus FV1000 Confocal Upright) using a UPLFL 40X/0.75, plus 3X magnification, two laser wavelengths (405 and 635 nm) and phase contrast to visualize capillaries. Nine confocal slices were stacked for analysis. The number of tanycyte vimentin-positive extensions in contact with basal capillaries was counted in 3 representative slices of the anterior, medial and posterior regions of the ME.

2.4. Triple Immunofluorescence for Vimentin, TRH and TRH-DE in Rat Brain Slices

The protocol was designed to maintain the structure of the extracellular domain of TRH-DE and TRH content in nerve terminals. Pore formation with saponin is subtler and more selective than permeabilization with detergents such as Triton X-100 or Tween-20 [

27], which extract membrane proteins reducing immunodetection, a problem we initially faced when testing different TRH-DE antibodies. The chosen anti-TRH-DE antibody labeled rat brain areas in agreement with the known distribution of

Trhde mRNA [

28], as well as positive controls in rat (

Sup. Figure S1C-G).

Rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium ip and perfused first with 50 mL of PBS 0.01 M pH=7.4 supplemented with 15 000 U/L heparin sulfate, and then with 100 mL of a mix of PFA (3%) and acrolein (1%); excess acrolein was eliminated by perfusion with 50 mL of PFA (3%) [

29]. Brains were removed and post-fixed with PFA (3%) at 4 °C for 6 h. Brains were processed, sliced and stored as indicated above. Sections were incubated with NaBH

4 0.1% for 15 min, washed with PBS 0.01 M and incubated with a mixture of 5% powdered milk (lactose-free Svelty) and saponin 0.1% in PBS 0.01 M for 3 h. Sections were incubated with antibodies (sources and dilutions listed in

Sup. Table S2) diluted in PBS 0.01 M pH=7.4 with saponin 0.1%; first, with anti-TRH (at 4 °C overnight), the next day with a secondary anti-goat Cy3 (at room temperature for 2 h), then with an anti-vimentin (at 4 °C overnight), and finally with a secondary anti-chicken Alexa-647 (at room temperature for 2 h). To reveal TRH-DE localization, slices were washed 4 times with PBS 0.01 M to remove any trace of saponin and then incubated with anti-TRH-DE (at 4 °C overnight). Slices were then incubated with a secondary antibody Alexa-488 (at room temperature for 2 h) and finally contrasted with DAPI and mounted with Citifluor montage medium (EMS Acquisition Corp., Hatfield, PA). Brain sections were visualized at the National Laboratory of Advanced Microscopy (UNAM) in a confocal microscope (Olympus FV1000 Confocal Upright) using UPLSAPO 10X/0.40, UPLFL 40X/0.75 and oil immersion UPLSAPO 60X/1.30, and laser wavelengths 405, 488, 543 and 635 nm.

2.5. Microinjection into the Rat Brain Third Ventricle (3V)

Rats were anesthetized with intramuscular ketamine (50 mg/Kg) and xylazine (10 mg/Kg), and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus (Kopf Instruments, Tigunga, CA). A small hole was drilled through the skull; the injector (28G internal cannula, Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) coupled to a syringe pump (Bioanalytical Systems Inc, IN) was first inserted approximately 0.5 mm lateral to the middle axis to avoid bleeding due to damage of the central cerebral vein and then relocated to the center to push the vein. To identify the site of injection, a group of rats was injected with 10 µL of 0.04% of trypan blue in PBS (rate: 0.5 μL per min) in the third ventricle, in the proximity of the ME (0 mm from the midline, -2.4 mm anteroposterior from Bregma and -9.4 mm dorsoventral from dura mater); we observed the stain in the third ventricle and ME; the injection site was confirmed by the gliosis that tracks it (

Sup. Figure S4A). Once the validity of the coordinates was established, rats were injected with 10 μL (0.5 μL/min) of adeno-associated virus (AAV) or sterile vehicle (0.001% Lutrol/F68 in PBS, Thermo Scientific, UT). The cannula was slowly removed 10 min after the end of the injection. The hole in the skull was covered with bone wax, the skin was sutured, and rats were injected with 40000 IU of benzylpenicillin (Benzetazil, Sandoz, Mexico) intra-muscular. Rats were maintained at two per cage, with food and water

ad libitum and body weight and food consumption was measured every week. In experiment 7, rats were habituated to tail blood extraction one week after AAV injection; then at week 2 they were moved from their home cage to either an adjacent room at 4

oC (cold stressed) or at 21 ± 1 °C (control temperature) at 9:00 h. Blood was collected from the tail in basal conditions and after 1 h cold exposure. Blood samples were centrifuged to obtain serum for hormone determination.

2.6. Analysis of AAV Ability to Transduce Rat Tanycytes In Vivo

Two or three weeks after the 3V injection of either AAV4-GFP, or self-complementary (sc) versions of AAV1-GFP, AAV2-GFP, AAV4-GFP, AAV5-GFP, AAV6-GFP, AAV8-GFP, AAV9-GFP, AAVD/J-GFP (University of Iowa Viral Vector Core;

Sup. Figure S4B) that expressed GFP under the cytomegalovirus promoter, rats were perfused with 50 mL of PBS 0.01 M/heparin 10 U/mL and 200 mL of 4% PFA in PBS. Cryopreservation, sectioning, and storage were as described above. To determine the distribution of GFP expression in the medio-basal hypothalamus, brain sections were mounted on a slide and some sections were processed for vimentin immunofluorescence to evaluate whether tanycytes were transduced. For detection of GFP fluorescence, sections were mounted and directly visualized in an Axioscop Zeiss epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss Neofluar 20X/0.58) coupled to a Jenoptik camera using Morpho software (exposure of 4000 ms and gain 1).

2.7. Efficiency of AAV1-TRH-DE and -TRH-DEt Vectors to Induce Changes in TRH-DE Activity in Cell Culture

To overexpress TRH-DE, or a truncated isoform of TRH-DE (TRH-DEt), a dominant negative isoform [

28], we used recombinant AAV1 vectors that allowed expression of TRH-DE (AAV1-TRH-DE) or TRH-DEt (AAV1-TRH-DEt) under the cytomegalovirus promoter (Cyagen Biosciences, Santa Clara, CA) (Figure 3A). Efficiency of AAV1-TRH-DE and AAV1-TRH-DEt transgene expression was tested in COS-7 cells cultured as described [

28]. 3x10

5 COS-7 cells were seeded and incubated with AAV1-TRH-DE at a multiplicity of infection (moi) of 1x10

4 in 35 mm dishes. Activity of dominant negative isoform transgene was evaluated by adding increasing proportions of AAV1-TRH-DEt to AAV1-TRH-DE. Cells were harvested after 48 h, membranes extracted, and TRH-DE activity was measured.

2.8. Overexpression of TRH-DE and TRH-DEt in Rats

To overexpress ME TRH-DE or TRH-DEt in vivo, 8.75x1010 - 4.37x1011 viral genomes (vg) of AAV1-TRH-DE or AAV1-TRH-DEt were injected into the third ventricle just above the ME. Sham animals were injected with vehicle or 8.75x1010 - 4.37x1011 AAV1-GFP genomes. The number of viral genomes injected is indicated in text and legend of figures. At either 2, or 3, or 4 weeks after injection, rats were killed by decapitation by a trained technician, and trunk blood serum was collected and stored at -70 °C. White adipose tissue (WAT) was weighted. Tissues were stored at -70 °C for measurement of TRH-DE activity. In experiment 5, 2 animals from each experimental group were used for TRH-DE immunohistochemistry, as described above. For overexpression of TRH-DE or TRH-DEt in the supraoptic nucleus (SON), 4.37x109 viral genomes were injected at the base of each side of the brain (+-2 mm from the midline, -1.4 mm anteroposterior from Bregma and -9.2 mm dorsoventral from dura mater) and effects were measured two weeks after viral injection.

2.9. Hormone Assays

For rats, serum TSH (IB79181, IBL-America), as well as total T3 (tT3) and total T4 (tT4) (Diagnóstica Internacional [Zapopan, JAL, México]), arginine-vasopressin (AVP) (OKEH03099, Aviva Systems Biology, San Diego, CA), prolactin (PRL) (80560, Crystal-Chem, Elk Grove Village, IL), growth hormone (GH) (80586, Crystal-Chem, Elk Grove Village, IL), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) (ab119548, Abcam, UK) concentrations were measured with ELISA kits, by duplicate within the same assay. The sensitivity ranges were: 0.1-80 ng/mL for TSH, 0.1-10 ng/mL for tT3, 0.1-25 μg/dL for tT4, 31.3-2000 pg/mL for AVP, 5-80 ng/mL for PRL, 0.025-1.5 ng/mL for GH and 31-2000 pg/mL for IL-6. To ensure a linear dose-signal relationship in tT3 and tT4 assays, serum from hypothyroid rats was added to the standard curve, in accordance with Bianco et al, 2014 [

31]. Serum TSH concentration was also measured with a radioimmunoassay (RIA) using rNIDDK reagents (Bethesda, MD); detection limit: 25 ng/ml; intra-assay and inter-assay variation coefficients < 10 %. To quantify serum TRH concentration, orthophenantroline 1 mM final, an inhibitor of thyroliberinase, was added to blood at recollection, and serum was kept at -20 °C. Serum was thawed and mixed with 4 volumes of cold acetic acid 20% and centrifuged at 12000 g for 30 min at 4

oC; 2 volumes of cold methanol were added to the supernatant, which was centrifuged; the supernatant was evaporated. Residue was resuspended in RIA buffer and TRH quantified by RIA using the R2 antibody [

32]. The sensitivity range was 25-2500 pg. Intra- and inter-assay variation coefficients were <10%. Serum TSH, tT3, and tT4 were also quantified with a Milliplex MAP Rat Thyroid Panel (RTHYMAG-30K, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), which uses antibody-coated magnetic beads coded with fluorescence to simultaneously measure multiple analytes in a sample. Serum TSH concentration was similar with the 3 methods (not shown). Data in Figure 4 and 6 were obtained by ELISA, those shown in Figure 3 by RIA and those in Figure 5 by the 3 methods.

For mice, serum leptin and tT4 concentrations were determined with ELISA kits (Crystal Chem Co, Diagnostica Internacional, respectively), corticosterone and TSH concentrations by RIA [

33] within the same assay. The sensitivities were: 0.1 ng/mL for serum leptin, 50 ng/mL for serum tT4, 1 ng/mL for serum tT3, 25 ng/mL for serum corticosterone, and 0.2 ng/mL for serum TSH.

2.10. TRH-DE, Thyroliberinase and Aminopeptidase N (APN) Activities

The TRH-DE activity assay was based on the protocol described by [

34], with some modifications. Brains were extracted and washed with fresh PBS. The ME, a small protuberance in the basal hypothalamus, was carefully dissected using 2 mm Vannas Spring Scissors (15000-03; Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA) and immediately frozen in dry ice. Tissues were sonicated in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4) and centrifuged at 80,000 rpm. After a wash with phosphate buffer, pellets were sonicated again to obtain membrane extracts and stored at −70 °C until TRH-DE activity was measured. For serum thyroliberinase activity, 5 uL of blood serum was used per assay. Membranes or serum were added to a mix of bacitracin and N-ethyl-maleimide and a saturating amount of dipeptidyl peptidase IV. After 10 min of preincubation, TRH-methyl coumarin (TRH-MCA), a fluorogenic substrate of TRH-DE, was added to the reaction tubes. Once His-Pro-MCA is released by TRH-DE activity, dipeptidyl peptidase IV releases MCA. An aliquot of the reaction was taken and mixed with the same amount of cold methanol every hour. The last reaction sample was taken after 3 h. MCA fluorescence was measured with a Nanodrop 3300 fluorospectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) excited with an UV LED (400-750 nm) and read at 437 nm. For APN, activity was assayed with 400 µM Ala-β-naphtylamide (βNA) as substrate in 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 as described [

35]. Released βNA was determined in a fluorometer (excitation, 335 nm; emission, 410 nm). Enzymatic preincubations and assays were performed at 37 °C; assays were done under initial velocity conditions in duplicate.

2.11. Genomic DNA PCR

To determine the number of Trhde

tm1Lex alleles, DNA was extracted from the tails of mice, purified as described (basic protocol 1; [

36]) and amplified by PCR using the oligonucleotides described in

Sup. Table S3. The products were separated by gel electrophoresis and detected by staining with ethidium bromide. WT mice are characterized by one 421, and KO mice by one 494 nucleotides band [

23].

2.12. End-Point RT-PCR

Gene expression in mouse tissues was evaluated by end-point RT-PCR. After dissection tissue was frozen onto dry ice. Total RNA was isolated as described [

37]. RNA was quantified by spectroscopy, and integrity examined by gel electrophoresis and staining with ethidium bromide. Samples that were not intact were not included in further analysis.

Trh,

Trhde and

Dio1 mRNA levels were determined by semi-quantitative RT-PCR using

Actb or

Hprt or

Ppia (indicated in Fig. legend) mRNA as internal control [

38]. Oligonucleotides used are described in

Sup. Table S3.

Briefly, each RNA sample (1 μg) was reverse-transcribed. For each cDNA product and amplicon, amplification conditions were chosen so that there was linearity between number of cycles and quantity of DNA product. For each cDNA product, aliquots of the amplicons were mixed and electrophoresed together; the gels were stained with ethidium bromide, amplicons identified according to molecular weight and quantified by densitometry with a Multi-Imager (Biorad). Ratio of

Trh or

Trhde or

Dio1 over internal control amplicon signal was computed; this method gives results that are comparable with those obtained by Northern analysis [

39,

40]. Genotypes did not change

Actb or

Hprt amplicon levels, assessed through densitometry of ethidium bromide-stained amplicons. Treatment effects on mRNA levels were generally consistent whatever the internal standard used; if this was not the case, we did not take the data into account.

2.13. RT-qPCR

Gene expression in rat tissues was evaluated by RT-qPCR. For PVH mRNA analysis, frozen brains were mounted in the cryostat and a 200 µm slice centered on the PVH region (-0.06 mm to Bregma, according to [

25]) was cut. Bilateral PVH samples were obtained with a 1 mm internal diameter punch, and RNA was extracted using an RNAEasy Plus Micro kit (74034, Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) using provider protocol. For anterior pituitary analysis, frozen tissue RNA was extracted with 500 uL of QIAzol Lysis Reagent (79306, Qiagen Sciences, Maryland, USA) using provider protocol. Genomic DNA was removed with a RapidOut DNA Removal Kit (K2981, Thermo Fisher Scientific Baltics UAB, Vilnus, Lithuania). RNA concentration was measured with a Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). cDNAs were generated with 0.5 ug of RNA using random primers (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Figure S2

qPCR primers are described in

Sup. Table S3; Rplp0 probes were used for normalization since Rplp0 expression was independent of treatments. For the PVH, the qPCR reaction was performed using Kapa Sybr® fast (Roche). For anterior pituitary, qPCR reaction was performed using qPCRBIO SyGreen Mix (PB20.17, PCR Biosystems, Pennsylvania, USA). A Qiagen Rotor Gene Q thermocycler (Qiagen Sciences, Maryland, USA) was used. A posterior melt analysis was made to verify the absence of non-specific PCR products.

2.14. Data Presentation and Statistical Analyses

Results are presented as mean ± SEM. The number of independent determinations is included in figure and supplementary figure legends, supplementary tables and in the text. For mice, data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 9.5.1. For rats, data were processed and analyzed using R Statistical Software (v. 4.2.2)[

41]. Graphs were made using R libraries cowplot (v. 1.1.1)[

42], and tidyverse packages ggplot2 (v. 3.3.6), dplyr (v. 1.09), tidyr (v. 1.2.0) and stringr (v. 1.4.0) [

43].

A paired t-student test was used for experiments where two independent groups were compared, unless specified. When more than 2 groups were compared, parameters were analyzed by ANOVA, followed by a Bonferroni post-hoc test. Effects of time and treatments over hormone measurements in experiment 1 were analyzed with a non-parametric two-way ANOVA followed by a Kruskal Wallis post hoc test.

To identify correlations between variables from different experiments, data from rats were standardized using a z-value transformation and ME TRH-DE activity was transformed using its natural logarithm, as ME TRH-DE expression showed skewness due to the high TRH-DE activity in the ME of several AAV1-TRH-DE injected animals. For this, mean and standard deviation for each variable were calculated for the control group (vehicle or AAV1-GFP). Each z value was obtained subtracting the mean of the control group from the original value and dividing by the standard deviation of the control group. Data from experiments 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 were grouped and correlation coefficients were determined using Pearson, Spearman and Kendall methods. P values were obtained using standard methods from base R libraries (t test, algorithm AS 89 and rho test, respectively).

3. Results

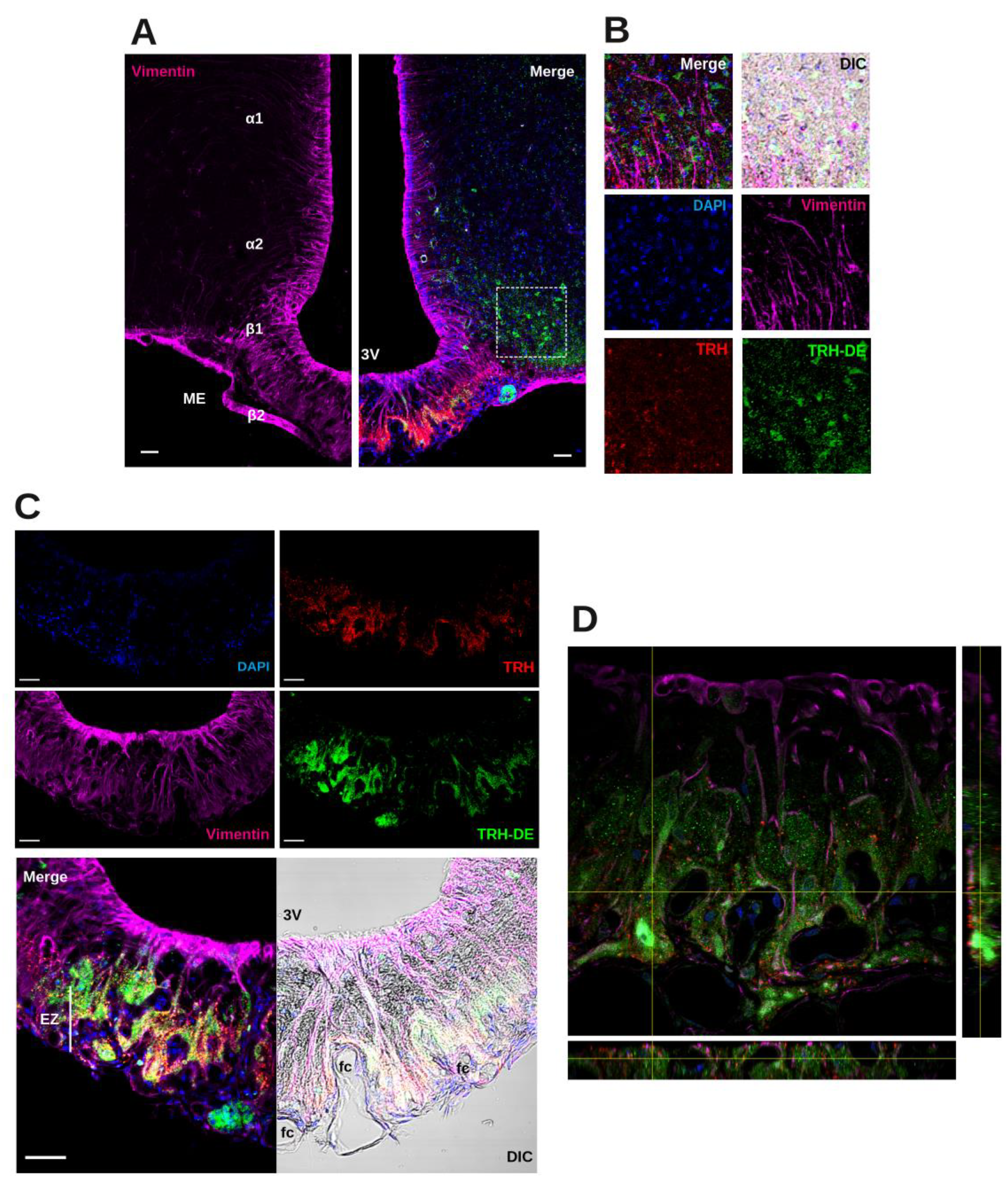

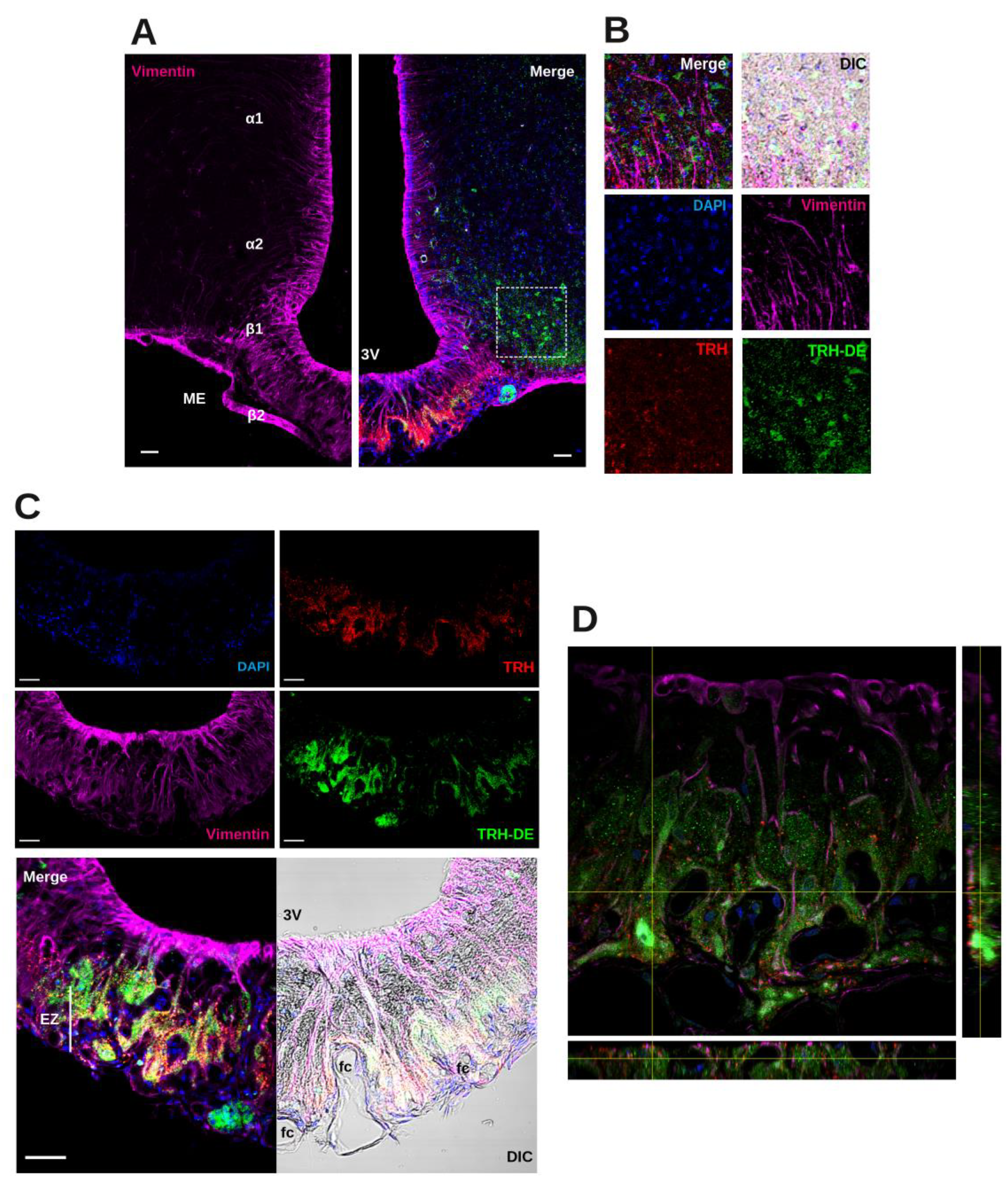

3.1. Localization of TRH-DE Immunoreactivity in the ME of the Adult Rat

In rats, ME TRH-DE activity was consistently detected at postnatal day (PND) 10, reaching a maximum value at PND 60 (

Sup. Figure S1B), a time-point chosen for all additional experiments. TRH-DE specific activity was much higher in the ME than in the anterior or posterior pituitary or whole brain, as reported [

15,

18,

28,

44]. A substantial TRH-DE activity per microliter of serum, corresponding to thyroliberinase, an isoform of TRH-DE produced by the liver [

45], was also detected (

Sup. Figure S1A), in agreement with previous data [

44].

Although

Trhde mRNA expression is prominent in the rat ME in tanycyte vimentin-positive domains that extend down to the ME external zone [

15], the spatial relationship between TRH-DE protein, tanycyte end-feet, and TRH terminals is unknown. Triple labeling immunofluorescence experiments showed the distribution of TRH-DE, vimentin and TRH in the ME and neighboring region of the male rat. In the hypothalamus, vimentin staining was enriched along the ventro-lateral and ventral walls of the third ventricle, overlapping ependymocyte and tanycyte domains (

Figure 1A). In the ME, β2-tanycyte bodies with visible nuclei packed in the ependymal layer contacting the third ventricle extend a vimentin process in direction of the external zone where it subdivides among TRH axons and terminal buttons [

15]. TRH-DE immunofluorescence signal was detected in limited regions of the medio basal hypothalamus, enveloping ARC cells and specific regions of the ME (

Figure 1A, B). Alpha-tanycytes were not labeled with the TRH-DE antibody, whereas labeling was predominant in the medial/external zone of the ME, surrounding vimentin fibers, and in close relationship with TRH terminal buttons, outlining the domains of ventral fenestrated capillaries; however, TRH and TRH-DE signals were not colocalized (

Figure 1C, D). Other TRH-DE positive structures in the ME were pars tuberalis cells (

Figure 1C). This pattern of TRH-DE immunodetection was consistent along the rostro-caudal extent of the ME (

Sup. Figure S1H). These observations show that TRH-DE is close to the putative sites of TRH release in the rat ME and could therefore influence the amount of TRH reaching the portal vessels. Hence, we measured the impact of the long-term modification of TRH-DE activity over serum TSH concentration and other HPT axis parameters in rodents housed in standard conditions.

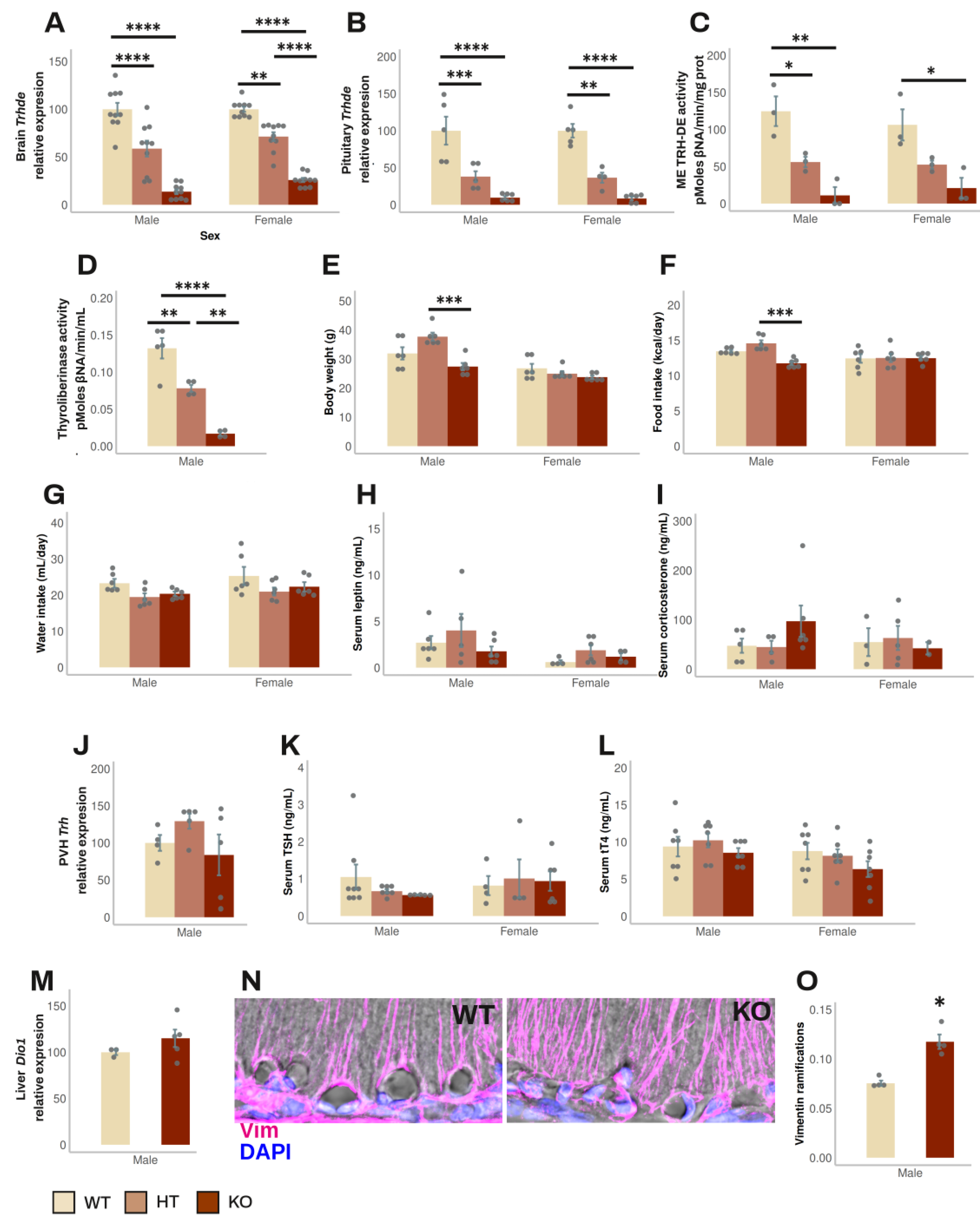

3.2. Effect of Global Elimination of Trhde Expression on Basal HPT Axis Activity in Mice

Trhde KO mice (in the B6129S5 background) have a normal phenotype, except that body weight is slightly lower than in wild type (WT) or heterozygous (HT) mice [

23]; the status of the HPT axis has not been reported. To test whether the absence of TRH-DE activity influences HPT axis activity, we back crossed the original mutation to the C57BL/6NJ background for up to 11 generations of mice. Mice were fed and reared in standard conditions. HT mice fertility was normal. Both male and female mice were tested after 1, 5, 9 and 11 back crossings, when two months old. All mice appeared healthy; at 6 months age, survival was 100% (n=36).

The β-gal reporter was used to compare the expression sites of

Trhde in transgenic male mice with those in WT mice (Allen mouse brain atlas [

46]). Staining was found in

Trhde HT and KO mice but not in WT mice, restricted to previously reported loci of expression: high intensity in hippocampus and cerebral cortex, intermediate in amygdala, preoptic area of hypothalamus, or PVH. In contrast to the detection of

Trhde expression and TRH-DE activity in the ME of WT mice (Allen mouse brain atlas [

46], and

Figure 2C), β-gal activity was not detected along the ventro lateral walls of the third ventricle and in the ME (

Sup. Figure S2), even with longer reaction times than indicated in methods. β-gal was detected by immunohistochemistry in Trhde KO mice in the same regions as the X-gal hydrolysis product, including ARC and pars tuberalis cells, but signal was scarce in the ependymal layer corresponding to ME tanycytes (

Sup. Figure S3). Failure to detect activity or immunoreactivity of β-gal along the base of the 3V is not due to the inability of tanycytes to express β-gal, as activity is detected in tanycytes in other transgenic models [

47]. The specific insertion locus can influence the activity of LacZ reporters in mice, and detection can diminish in advanced postnatal stages, explaining cellular differences in the detection of β-gal in multiple models [

48,

49]. Since TRH-DE activity is almost eliminated in the ME of

Trhde KO mice (

Figure 2C), it is likely that the locus of insertion in transgenic

Trhde mice impeached expression of β-gal in tanycytes.

The following data were independent of the number of generations. In male mice,

Trhde expression in brain and pituitary, and ME TRH-DE and thyroliberinase specific activities were reduced in

Trhde HT and almost eliminated in

Trhde KO compared to WT mice (

Figure 2A, B, C, D). After an ip injection of TRH, the concentration of TRH detected in serum was lower in WT than in

Trhde HT and KO animals (

Sup. Table S4), confirming that TRH-DE contributes to TRH elimination in blood [

50]. However, besides the notable differences in TRH-DE activity, we did not find other genotype-dependent differences in most parameters.

Trhde KO mice had a body weight that was not different from that of WT mice (

Figure 2E). Brain APN activity, the closest member of the M1 family of metalloaminopeptidases (

Sup. Table S4), food and water intake (

Figure 2F, G), circulating leptin and corticosterone concentrations (

Figure 2H, I), PVH

Trh mRNA levels (

Figure 2J), serum TSH and tT4 concentrations (

Figure 2K, L), and

Dio1 mRNA levels in liver (

Figure 2M) were not different between WT and KO mice. Notwithstanding, the number of vimentin filaments at the base of the external zone of the ME in contact with capillaries per area was higher in

Trhde KO male mice than in WT animals (

Figure 2N, O). For female mice, although we did not analyze some parameters, the data obtained were like those in male mice (

Figure 2;

Sup. Table S4).

These results suggest that TRH-DE has no influence on HPT axis activity in standard conditions, or that the effect of

Trhde gene mutation is compensated by adjustments of HPT control elements during development, such as morphological alterations of the ME. To test the specific role of ME TRH-DE in adult animals, we used a viral vector approach in rats, which a wealth of histologic and physiologic data place as a mammalian model of choice to study the HPT axis [

31], and for which access to any brain region for

in vivo cannulation is relatively straightforward compared to other small vertebrates [

51].

3.3. Identification of AAV Serotypes Whose Injection into Rat 3V Transduces ME Tanycytes

An increasing number of experimental applications of AAVs demonstrate consistent effects in transduced host cells, including short- and long-term expression

in vivo. However, brain manipulation with AAVs to study energy balance is limited to mouse models [

52]. We tested the effect of delivery in the 3V of adult rats of different AAV serotypes expressing GFP in a conventional AAV construction (

Sup. Figure S4B), or in a self-complementary construction to enhance the visualization of the transduced cells. As expected, two or 3 weeks after the viral injection, patterns of GFP expression were serotype-dependent, varying in GFP abundance and proportion of cell types, at identical multiplicity of infection.

Since β2-tanycytes are the cells that most likely contribute to

Trhde expression and activity in the ME [15,28,53,this study], we initially focused on the expression of GFP in the ME and surrounding areas. While scAAV1-GFP induced a consistent transduction of ME tanycytes (

Sup. Figure S4D, left panel), scAAV2-GFP transduced some ME tanycytes and mostly other cells (

Sup. Figure S4D, central panel), and AAV4-GFP transduced varicosities or nerve terminal buttons present in the external layer of the ME (

Sup. Figure S4D, right panel); for other serotypes the level of transduction in the ME was low or undetectable (

Sup. Table S5). At the multiplicity level tested (4.5x109 viral genomes), injection of scAAV1-GFP allowed the highest GFP signal in tanycytes (

Sup. Table S5). Although we have not quantified the proportion of β2-tanycytes that are transduced with scAAV1-GFP, qualitative observations suggest that it is in the 20-50% range. Other brain regions were also transduced by 3V AAV, dependent on the serotype.

The choroid plexus and subcommisural organ were labeled by AAV4, AAV5 and AAV6 (

Sup. Figure S4C,

Sup. Table S5), but not by AAV1 or other serotypes. Except for AAV5, meningeal cells were transduced by all serotypes (

Sup. Table S5). Although for most AAV serotypes (except AAV4 and AAV5) we observed GFP fluorescence in varicosities and compartments resembling Herring bodies in the posterior pituitary, we did not observe fluorescence in the anterior pituitary (

Sup. Figure S5A). Posterior pituitary transduction coincided with labeling of cell soma in the SON when AAV1, AAV2, AAV6, and AAV8 were injected (

Sup. Figure S5B). We did not detect labeling of the PVH, albeit other hypothalamic nuclei were labeled by AAV2, AAV8, AAV9 and AAVD/J (

Sup. Table S5).

Based on cellular specificity and intensity of GFP transduction we selected the AAV1 serotype to manipulate TRH-DE activity in the ME. Although the specificity of AAV1 for the ME was not absolute, key hypothalamic centers in energy balance (ARC, dorso- and ventro-medial hypothalamus, and PVH) did not express GFP (

Sup. Table S5). As expected, after stereotaxic surgery, body weight was lower than in intact animals for 1 month: however, compared to vehicle injected animals, AAV1-GFP administration neither changed the rate of body weight increase (

Sup. Figure S4E), nor modified basal serum TSH concentration (

Sup. Figure S7L), nor induced a detectable concentration of interleukin 6 in serum (less than 31 pg/mL, n=3).

These data suggest that AAV1 delivery into the 3V of adult rats allows the relatively specific modification of gene expression in ME cells, without modifying basal HPT axis activity, and thus seems adequate to explore the effect of modifying TRH-DE activity on HPT axis variables.

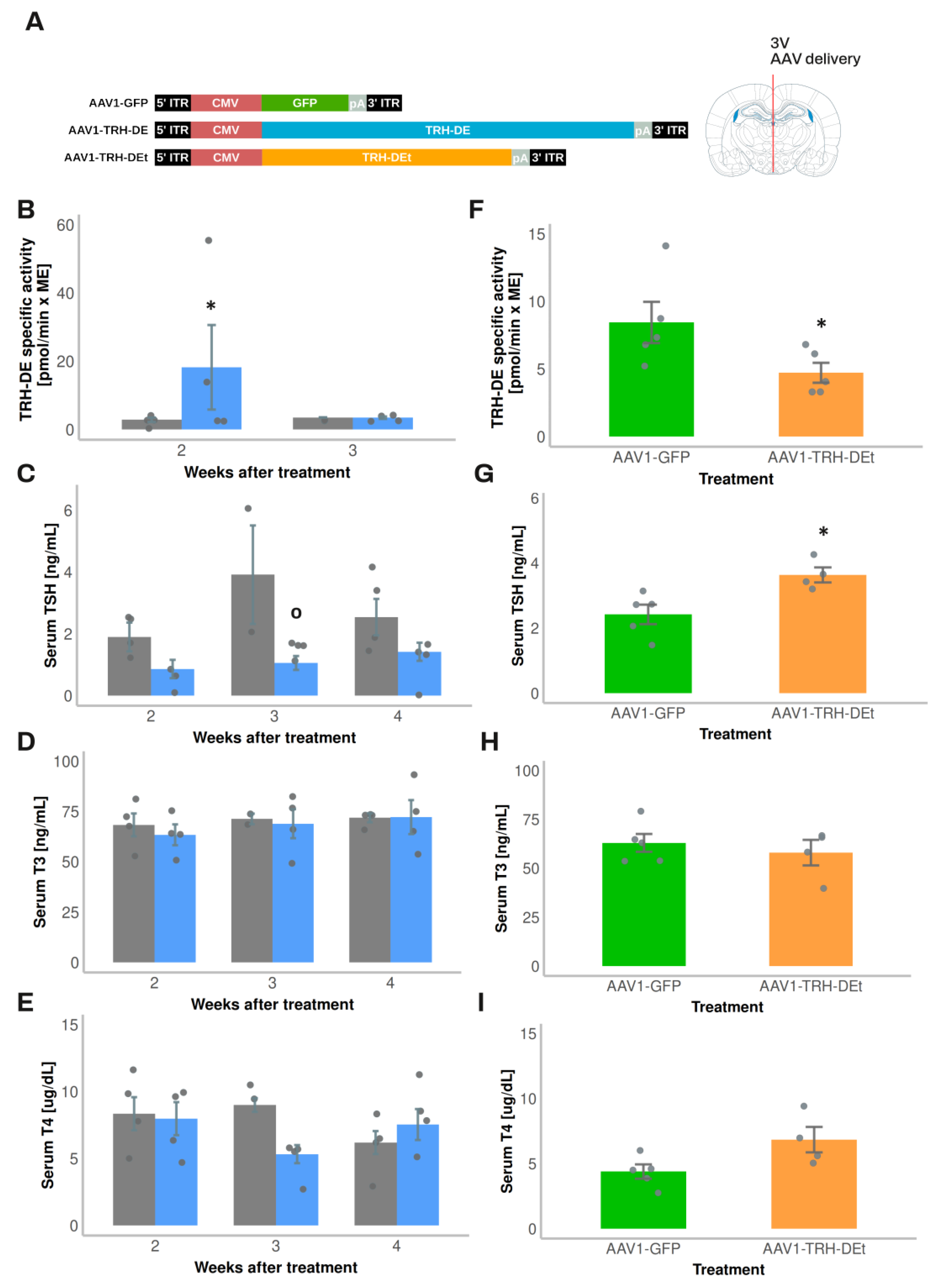

3.4. Temporal Dynamics of Over- or Under-Expression of TRH-DE Induced by AAV1 Constructions and Influence on TSH Secretion and HPT Axis Parameters

AAV1 vectors were designed to overexpress TRH-DE (AAV1-TRH-DE) or TRH-DEt (AAV1-TRH-DEt), a truncated isoform of TRH-DE with dominant negative influence [

30] (

Figure 3A). Both AAV vectors transduced COS-7 cell cultures efficiently and either increased (AAV1-TRH-DE) or reduced TRH-DE activity (AAV1-TRH-DEt) in a concentration-dependent manner (

Sup. Figure S6A). TRH-DE immunoreactivity in the external zone of the ME was enhanced in animals injected with AAV1-TRH-DE or AAV1-TRH-DEt when compared with AAV1-GFP injection in the 3V (experiment 5,

Sup. Figure S6B, C). Our success rate at modifying ME TRH-DE activity in either direction was variable; we detected changes in TRH-DE ME activity of at least 50% compared to the mean of control groups in 65 ± 6% (n=4 experiments) of AAV1-TRH-DE injections and 55 ± 5% (n=2 experiments) with AAV1-TRH-DEt injections.

Regarding the cellular specificity of the expression of TRH-DE or TRH-DEt, based on AAV1-GFP transduction data, an effective AAV1-TRH-DE injection should have raised TRH-DE activity in tanycytes and other ME cell types, as well as in SON magnocellular neurons. In contrast, while AAV1-TRH-DEt injection should induce TRH-DEt expression in the same cells, the dominant negative catalytic effect of this truncated isoform of TRH-DE should be limited to cells that express the complete TRH-DE isoform and be specific for TRH-DE [

30]. Because

Trhde expression in the medio-basal hypothalamus is predominant in β-tanycytes [

15,

17,

53], TRH-DEt injection into the 3V should produce an almost specific knock-down of β-tanycyte TRH-DE activity.

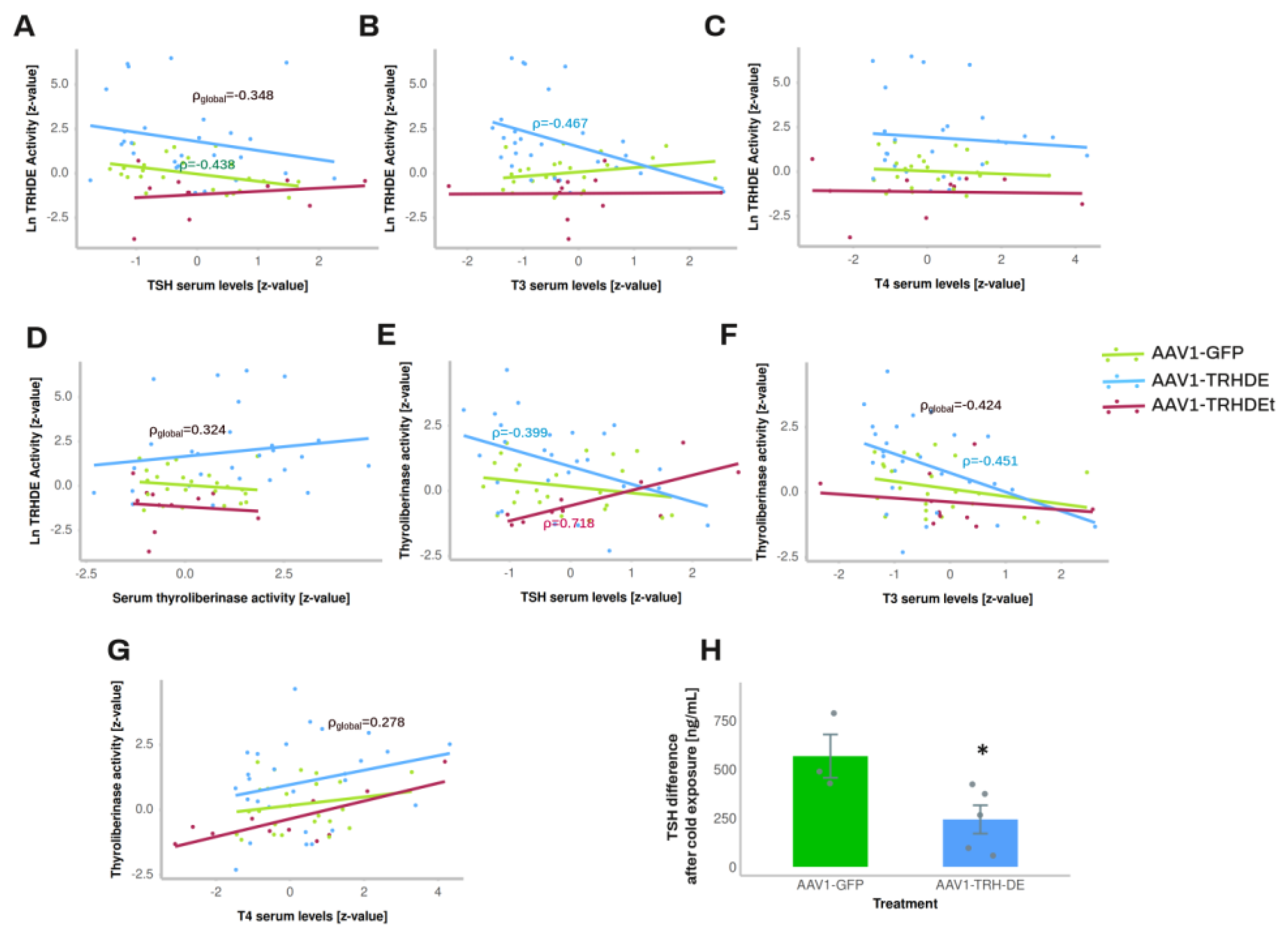

Exposure of rats to 4ºC for up to 2 h transiently increases

Trh expression in the PVH and serum TSH concentration [

54,

55]. Although in experiment 7 injection of AAV1-TRH-DE did not change serum concentrations of TSH 2 weeks later in rats maintained at room temperature (AAV1-GFP: 331 ± 126 (n=3); AAV1-TRH-DE: 499 ± 35 pg/mL (n=5); p=0.157, Student’s t-test), tT3 (AAV1-GFP: 2018 ± 322 (n=3); AAV1-TRH-DE: 2914 ± 279 pg/mL (n=5); p=0.088, Student’s t-test), and tT4 (AAV1-GFP: 83 ± 3.9 (n=3); AAV1-TRH-DE: 89 ± 1.6 ng/mL (n=5); p=0.1568, Student’s t-test), a rise of serum TSH concentration in AAV1-GFP rats was detectable after 1 h cold exposure, a response blunted in AAV1-TRH-DE animals (Figure 5H). These data demonstrate that TRH-DE activity in the ME controls TSH secretion when a stimulus induces TRH release, as proposed previously [

15] and suggest that ME TRH-DE activity does not control the basal serum concentration of TSH in male rats. To test this latter suggestion, we performed other experiments.

In experiment 1, compared with the vehicle group, we detected a rise in ME TRH-DE activity two weeks after the intra 3V delivery of AAV1-TRH-DE, an increase which was reversed at 3 weeks (

Figure 3B). This unexpected reversal was specific for the AAV1-TRH-DE since we found stable GFP expression with AAV1-GFP injected animals after 4 weeks of injection (not shown). The mechanistic basis of this result is unknown; it contrasts with data that show that AAV transduction generates stable long-term expression of proteins in mouse tanycytes [

52]. The regional specificity of the transduction was confirmed as we didn’t detect changes in TRH-DE activity in the anterior pituitary (

Sup. Figure S5C), or in serum thyroliberinase activity 2 or 3 weeks after AAV1-TRH-DE delivery in the 3V (

Sup. Figure S6E). The AAV1-TRH-DE injection produced a small but significant decrease in serum TSH concentration (

Figure 3C) 3 weeks after viral delivery; serum concentration of total TH (

Figure 3D, E), and of GH (AAV1-GFP: 34.3 ± 18.5 (n=2); AAV1-TRH-DE: 22.9 ± 12.3 ng/mL (n=4); p=0.621, Student’s t-test), and body weight gain (

Sup. Figure S6D) were not altered.

Because of this unexpected time-dependent reversal of 3V AAV1-TRH-DE effect on ME TRH-DE activity, we restricted the evaluation of transduction effects to the second week post viral delivery for the next experiments. In experiment 2, compared to AAV1-GFP injected animals, TRH-DE activity decreased in the ME of some animals injected with AAV1-TRH-DEt (

Figure 3F), while thyroliberinase activity was unchanged (

Sup. Figure S6E). AAV1-TRH-DEt injection into the 3V enhanced serum TSH concentration (

Figure 3G), but neither changed serum TH concentration (

Figure 3H, I), nor body weight gain (

Sup. Figure S6F).

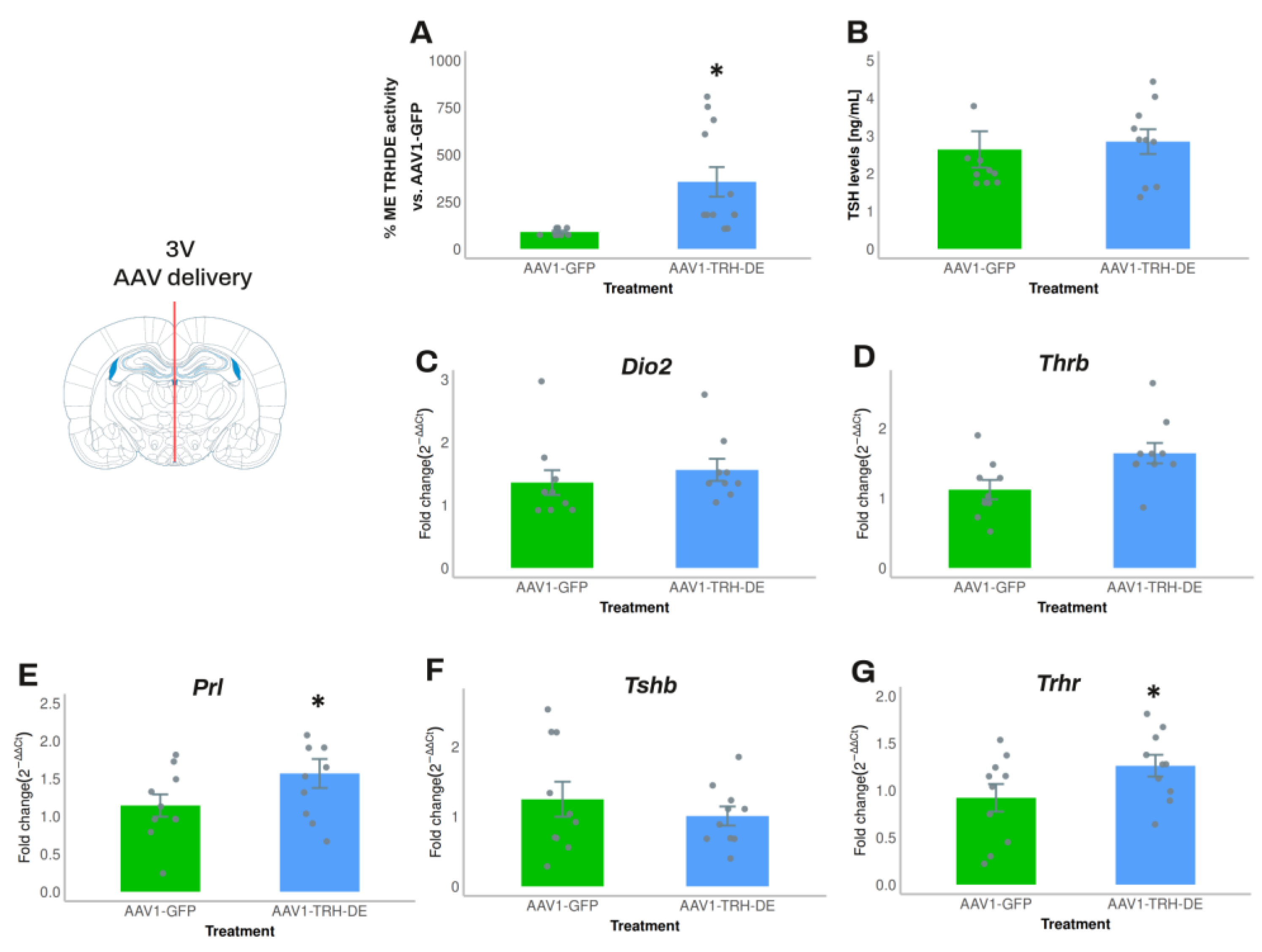

In experiment 4, we increased the quantity of AAV1-TRH-DE and AAV1-GFP injected. Compared to the average activity of the AAV1-GFP group, AAV1-TRH-DE injection increased ME TRH-DE activity 8-fold (

Figure 4A). Nevertheless, anterior pituitary

Dio2,

Thrb and

Tshb expression (

Figure 4C, D, F), serum TSH concentration (measured with either RIA or ELISA;

Figure 4B,

Sup. Figure S7A), and serum concentration of tT3 (AAV1-GFP: 72.8 ± 8.0 (n=10); AAV1-TRH-DE: 61.6 ± 3.9 ng/mL (n=10); p=0.22, Student’s t-test) or tT4 (AAV1-GFP: 3.28 ± 0.31 (n=10); AAV1-TRH-DE: 3.60 ± 0.37 μg/dL (n=10); p= 0.5047, Student’s t-test) did not change. In contrast, AAV1-TRH-DE injection increased anterior pituitary

Trhr and

Prl expression (

Figure 4E, G), two genes that are regulated by TRH [

56,

57,

58].

Although in experiment 5 intracerebroventricular delivery of AAV1-TRH-DE or AAV1-TRH-DEt changed TRH-DE ME activity in the expected direction (AAV1-GFP: 1.00 ± 0.11 (n= 5); AAV1-TRH-DE: 2.53 ± 0.92 (n= 4) ; AAV1-TRH-DEt: 0.88 ± 0.07 pmoles/min x ME (n= 5); p=0.058, 1-way ANOVA), it did not change

Trh PVH expression compared to AAV1-GFP (

Sup. Figure S7B), or serum TSH concentration (AAV1-GFP: 1.40 ± 0.63 (n= 5); AAV1-TRH-DE: 0.86 ± 0.34 (n= 4); AA1-TRH-DEt: 0.88 ± 0.24 pmoles/min x ME (n= 5); p= 0.479, 1-way ANOVA).

In experiment 6, stereotaxic injections of AAV1 vectors induced subtle effects in ME TRH-DE activity (AAV1-GFP: 1.32 ± 0.11; AAV1-TRH-DE: 1.53 ± 0.19; AAV1-TRH-DEt: 0.88 ± 0.08 pmoles/min x ME (n=7); difference between AAV1-TRH-DE and AAV1-TRH-DEt: p= 0.008, 1-way ANOVA), with no effect over serum concentrations of TSH (AAV1-GFP: 1.74 ± 0.37; AAV1-TRH-DE: 1.87 ± 0.44; AAV1-TRH-DEt: 1.57 ± 0.36 ng/mL (n=7), p= 0.859, 1-way ANOVA), tT3 (AAV1-GFP: 67.4 ± 24.0; AAV1-TRH-DE: 108 ± 22.3; AAV1-TRH-DEt: 87.5 ± 25.1 ng/mL (n=7), p= 0.486, 1-way ANOVA), tT4 (AAV1-GFP: 6.29 ± 0.32; AAV1-TRH-DE: 5.88 ± 0.23; AAV1-TRH-DEt: 5.32 ± 0.37 μg/dL (n=7), p= 0.120, 1-way ANOVA), or leptin concentration, white adipose weight, body weight (not shown), or serum triglyceride concentration (

Sup. Figure S7C).

In summary, the experiments in which we intended to modify TRH-DE expression in the ME did not show a reproducible effect on basal serum TSH and TH concentrations. This may be the result of insufficient statistical power, and/or of variable efficacy and precision of stereotaxic AAV injection, a parameter which could not be measured directly, except for its effect on ME TRH-DE activity. To consider some of these difficulties, we analyzed the correlations between ME TRH-DE activity and multiple HPT axis parameters in each experimental condition.

3.5. TRH-DE Activity in the ME and Basal Serum TSH Concentration Are Negatively Correlated in Adult Male Rats

The output of multiple experiments was grouped to analyze correlations between variables. As expected, serum leptin concentration strongly correlated positively with white adipose weight in all the experimental groups (

Sup. Figure S7D-F). ME TRH-DE activity was negatively correlated with serum TSH concentration in AAV1-GFP treated animals, or when considering all animals (significant Pearson, Spearman and Kendall correlations) (

Figure 5A), and with serum concentration of tT3 (

Figure 5B), but not with serum concentration of tT4 (

Figure 5C). ME-TRH-DE and thyroliberinase activities did not correlate (

Figure 5D), but we observed robust and significant correlations (Pearson, Spearman and Kendall tests) between thyroliberinase activity and serum TSH concentration, with opposite directions in the AAV1-TRH-DE and AAV1-TRH-DEt groups (

Figure 5E), making it unlikely that thyroliberinase activity sets serum TSH concentration. Thyroliberinase activity correlated negatively with serum tT3 concentration in the AAV1-GFP group (

Figure 5F), but not with serum tT4 concentration (

Figure 5G). As for anterior pituitary transcripts, data gathered from experiments 4 and 5 show that ME TRH-DE activity correlated negatively with Prl expression in the AAV1-GFP group, as with serum PRL concentration (Sup. Figure 7G, H), and serum tT4 concentration was negatively correlated with Dio2, Thrb, and Prl expression in the same group (Sup. Figure 7I-K).

To identify other factors affecting the correlation between ME TRH-DE activity and serum TSH concentration, partial and semi partial correlations were calculated [

59]. The partial correlation between ME TRH-DE activity and serum TSH concentration was still significant in global data (r= -0.307, p = 0.015) and AAV1-GFP treated animals (r=-0.49, p=0.016) when thyroliberinase activity was maintained constant. When the other factors (tT3, tT4, adipose tissue weight, and body weight gain) were compensated, global correlation was still significant (r = -0.32, p = 0.019), showing that none of the factors tested contributed to the negative correlation between ME TRH-DE activity and serum TSH concentration.

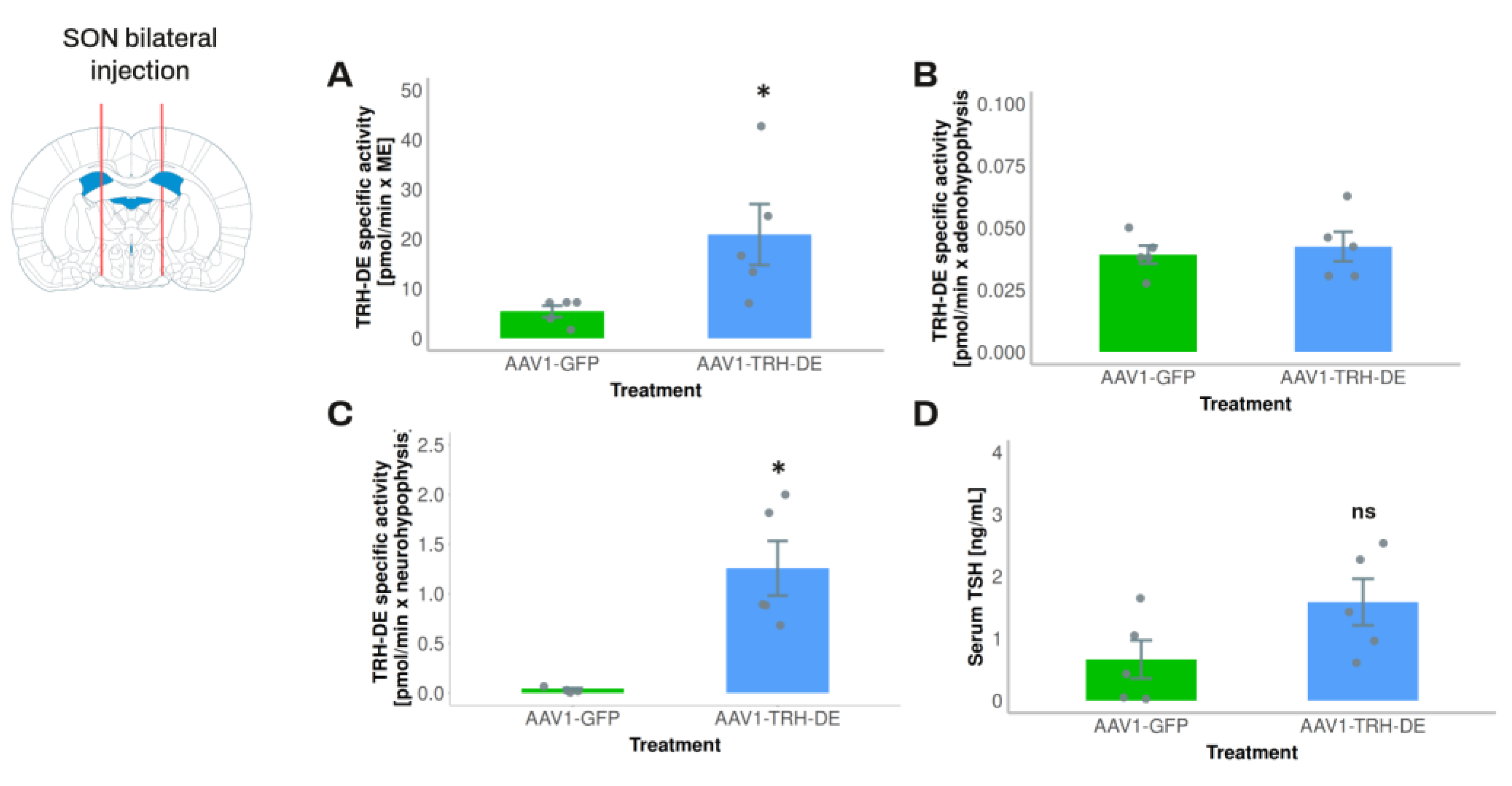

3.6. Exploring the Influence of Posterior Pituitary TRH-DE Activity on Basal Serum TSH Concentration in Rats

The 3V injection of scAAV1-GFP strongly enhanced GFP expression in the posterior pituitary (Sup. Figure 5A). This result was consistent with experiment 1, in which rats that received a 3V injection of AAV1-TRH-DE had a higher posterior pituitary TRH-DE activity than vehicle treated rats. As in the ME, this change in posterior pituitary activity was detected at 2 but not at 3 weeks (Sup. Figure 5D).

TRH concentration (but not

Trh expression), and TRH-DE specific activity (but not

Trhde expression) are higher in the rat posterior pituitary than in the anterior pituitary, although lower than in the ME [

28,

29,

60] (Sup. Figure 1A for TRH-DE activity).

Trh may be expressed by magnocellular neurons of the paraventricular and/or the SON of the hypothalamus [

61] and TRH may control the release of vasopressin and oxytocin [

62]. Regarding posterior pituitary TRH-DE activity, it might localize to magnocellular neuron axons, as significant expression of

Trhde was detected in the SON of wild type rats by transcriptomic profiling [

63]. Small amounts of

Trhr (and

Trhde) are expressed by pituicytes in mice [

64], suggesting that TRH might have a local role. We analyzed the functional impact of this locus of TRH-DE activity on serum TSH concentration.

To avoid a direct interference of AAV injection on PVH TRH neurons and tanycytes, in experiment 3 we injected AAV1-TRH-DE into both sides of the SON of the rat to induce an overexpression of TRH-DE in the posterior pituitary and measure its possible effects on serum TSH concentration. AAV1-TRH-DE injection into the SON successfully induced high TRH-DE activity in posterior pituitary (

Figure 6C), a small increase in the ME (

Figure 6A) consistent with the passage of SON axons through the ME, and no changes in the anterior pituitary (

Figure 6B), when compared to the AAV1-GFP group. Despite these marked changes of TRH-DE activity in the posterior pituitary, we did not detect a significant change in serum concentration of TSH (

Figure 6D), tT3 (AAV1-GFP: 60.6 ± 4.4; AAV1-TRH-DE: 52.7 ± 8.1 ng/mL (n=5), p= 0.282, Student’s t-test) or tT4 (AAV1-GFP: 2.52 ± 0.36; AAV1-TRH-DE: 3.21 ± 0.47 μg/dL (n=5), p=0.1156, Student’s t-test).

4. Discussion

The amount of TRH released by hypophysiotropic neurons that reaches the portal capillaries is not only controlled by their spiking patterns, but also by events that operate at nerve terminals and in β2-tanycytes. The relative physiological relevance of the phenomena occurring in the ME has yet to be fully clarified, including the specific contribution of β2-tanycyte TRH-DE. In this report, we show that TRH-DE is close to the putative sites of TRH release in the rat ME, that global Trhde KO mice do not show alterations in basal HPT axis parameters, and that long-term modification of TRH-DE activity in the ME of adult male rats has a small effect on basal serum TSH concentration, in contrast to a stronger one when hypophysiotropic TRH neurons are activated by 1 h cold exposure.

4.1. TRH-DE Is Close to the Putative Sites of TRH Release in the Rat ME

Trhde mRNA is detected in tanycyte cell bodies and in their cytoplasmic process [

15]. We demonstrated that TRH-DE immunolabeling is not homogeneous along the tanycyte cell surface in the ME, being more prominent in the intermedial and external zones, near the portal capillaries and TRH terminals, than in other subcellular loci. The localization of

Trhde mRNA into the cytoplasmic extensions may contribute to the polarization of TRH-DE localization since polarization of mRNAs and local translation enrich specific proteins at defined domains of the cell [

65]. Although factors contributing to the localization of TRH-DE in tanycyte end-feet are unknown, they probably follow mechanisms identified for other proteins in various glial cell types [

66].

Thus, ME TRH-DE activity, previously detected in the whole ME [

15], is likely concentrated in the intermedial/external layer of the ME, where it seems ideally suited to control TRH output into the portal capillaries. This subcellular information, together with a previous report showing that TRH-DE inhibition enhances the recovery of TRH released from ME explants [

15], supports a critical role of tanycyte TRH-DE activity in the control of TRH flux into portal vessels. This hypothesis was further tested with models in which a long-term modification of TRH-DE activity was established.

4.2. Two Models for Long-Term Modification of TRH-DE Activity

Young adult global KO

Trhde mice maintained in standard conditions, which are almost completely devoid of TRH-DE activity, either in the ME or in other sites of

Trhde expression, are apparently healthy, fertile, with no obvious phenotypic differences with WT animals, except for a small decrease in body weight in some cohorts (see also [

23]). Although this model should give insights into HPT axis control by TRH-DE, it has limitations. To eliminate the potential developmental effects of

Trhde KO and to focus on the specific role of ME TRH-DE activity, we also used a model in which we manipulated adult male rat ME

Trhde expression with AAV.

Transduction of different brain cell types mediated by viral vectors has been extensively documented, although information about the interactions of AAVs with different subtypes of glial cells is still incomplete, especially in the rat [

52,

67]. We tested the efficiency and specificity of different AAV serotypes injected into the 3V to transduce cells of the rat ME; 3V scAAV1 delivery targeted β2-tanycytes, among the occasional targeting of round-shaped cells in the ME. These findings are consistent with previous experiments in mice, in which tanycyte transduction was induced with a viral construction of mosaic AAV1 and AAV2 capsids injected into the lateral ventricles [

19]. However, the injection of AAV1 vectors into the rat 3V also led to labeling of the posterior pituitary, which could be due to diffusion of viral particles to ventral brain areas, including SON magnocellular neurons sending axons into the posterior pituitary. Thus, to induce a sustained and mainly local modification of TRH-DE activity in the ME, we used two vectors: AAV1-TRH-DE to increase, and AAV1-TRH-DEt to decrease ME TRH-DE activity.

4.3. ME TRH-DE Controls the Phasic Output of TSH

One of the best-known stimuli that activates the HPT axis is cold (4-5º C) exposure; in male rats reared in standard conditions, it rapidly enhances TRH mRNA levels in PVH neurons, TRH release into blood, and serum TSH concentration [

54,

55,

68,

69,

70,

71]. Previous reports suggested that tanycyte TRH-DE activity controls serum TSH concentration and/or HPT axis activity when a phasic induction of TRH release from the hypophysiotropic PVH TRH neurons is promoted by cold stress in rats or a chemogenetic activation in mice [

15,

19]. These experiments have however limitations: Sánchez et al, 2009 [

15] used the ip injection of a TRH-DE inhibitor that passes through the blood-brain-barrier, making it impossible to pinpoint the anatomical site involved; Müller-Fielitz et al, 2017 [

19] could not untangle the relevance for HPT axis activity of tanycytes end-feet from that of tanycyte TRH-DE or that of other tanycyte factors down-stream of Gαq/11 proteins.

Overexpression of TRH-DE activity in the ME reduced serum TSH concentration in response to cold exposure, likely because the availability of TRH to the pituitary was reduced. These data argue in favor of the idea that ME TRH-DE activity controls the phasic output of TRH into the portal vessels, but do not rule out the impact of tanycyte end-feet physical interaction with portal capillaries. We next used the viral strategy to investigate the control of basal serum TSH concentration by ME TRH-DE.

4.4. Long-Term Alteration of ME TRH-DE Activity Has Either No or a Small Impact on Basal Serum Concentration of TSH and TH

In heathy adult mice housed in standard conditions, the KO of genes involved in the central regulation of the HPT axis generally upsets thyroid homeostasis, while maintaining serum tT3 concentration inside circadian variation [

72]. For example, global or PVH-specific deletion of

Trh increases serum TSH concentration, diminishes TSH biological activity and leads to hypothyroidism [

73,

74]. Deletion in adult tanycytes of diacylglycerol lipase alpha, an enzyme that synthesizes an endocannabinoid that inhibits the release of TRH from nerve terminals in ME [

16], increases pituitary

Tshb mRNA level and circulating free T4 concentration [

75]. Global

Trhr deletion does not affect serum TSH concentration but produces hypothyroidism [

76,

77]. Deletion of

Dio2 in pituitary or in thyrotropes leads to high serum TSH concentration with low biological activity and normal serum TH concentrations [

78,

79].

Thrb-/- mice are hypothyroid with enhanced serum TSH concentration [

80]. In contrast, the PVH specific deletion of

Dio3 does not change hypothalamic expression of

Trh, or serum concentrations of TSH, tT4 and tT3 in mice of both sexes at baseline [

81]. Likewise, for

Trhde KO mice we expected a mild hyperthyroid status, but HPT axis variables were not distinct from those of WT mice. Therefore, in standard conditions the basal activity of the HPT axis seems resistant to long-term

Trhde elimination, despite no evidence that TRH-DE hydrolytic activity can be substituted by that of another protein [

22].

Nevertheless, in rats we obtained a more nuanced result. Except for a pair of experiments, we generally did not observe a significant effect of 3V AAV1-TRH-DE or AAV1-TRH-DEt injection over basal serum TSH concentration compared to AAV1-GFP injection. Neither

Trh expression in the PVH, pituitary

Tshb expression, total serum TH concentration, nor serum tT3/tT4 ratio, an indirect marker of TH biotransformation, nor body or WAT weights, nor expression of down-stream targets of TSH action were affected by 3V AAV1-TRH-DE or AAV1-TRH-DEt injection. The data were the same using different TSH immunoassays, limiting the possibility that TRH-induced TSH glycosylation [

82], and thus immunodetection, might have masked changes in serum TSH concentration. We cannot however exclude the possibility that the biological activity of TSH was modified.

Another limitation of our approach in rats is that viral injections did not always change ME TRH-DE, possibly because variations in the injection site altered the efficiency of transduction, and/or because TRH concentration in ME extracellular space negatively regulates endogenous TRH-DE activity [

19]. Thus, the conclusion that ME TRH-DE activity does not influence basal serum TSH concentration in rats could have been due to the way we analyzed the data, i.e. without separating successful injections from those that did not change ME TRH-DE activity, which might have reduced further statistical power. Indeed, when the output of multiple experiments was grouped, we found a small negative correlation between TRH-DE ME activity and serum TSH concentration, suggesting a small inhibitory influence of TRH-DE over basal serum TSH concentration in rats reared in standard conditions.

4.5. Long-Term Alteration of Trhde Expression Impacts Parameters That Might Control the Basal Activity of the HPT Axis in ME and Anterior Pituitary

Although we observed that serum TSH concentration was not or minimally affected by manipulation of ME TRH-DE activity, we nevertheless detected 2 adaptations that might have contributed to the stability of serum TSH concentration, in addition to the short loop positive feedback that TRH exerts on ME TRH-DE activity [

19]. First, the number of vimentin positive tanycyte ramifications in the ME was higher in

Trhde KO mice than in WT mice; excess TRH concentration around β2-tanycytes end feet might have activated a TRH-R1 transduction pathway that increases the coverage of portal vessels with tanycyte extensions [

19], limiting TRH access to portal capillaries, and thus maintaining basal TSH concentration. However, a limitation of our work is that vimentin extensions do not necessarily reflect the real cytoplasmic tanycyte coverage of ventral vessels. Second, AAV1-TRH-DE 3V injection increased anterior pituitary

Trhr expression, possibly because of a decrease in TRH concentration in the anterior pituitary extracellular space [

57,

58,

83]. Increased expression of the receptor might have dampened the physiological consequence of a decrease in pituitary TRH availability. Although preliminary, these observations suggest that the impact of sustained modifications of ME TRH-DE activity on HPT axis activity is opposed by other events that change TRH secretion from nerve endings, and limit TRH entry in the portal capillaries or TRH action on thyrotropes.

4.6. Multiple Evidence Indicates That Trhde Expression Is Not Critical for the Control of the Basal Activity of the HPT Axis

Despite experimental evidence that ME TRH-DE is positioned in proximity to TRH buttons and portal vessels, and that ME TRH-DE activity controls the phasic output of TRH into the portal vessels, previous results had shown that an intravenous injection of a specific inhibitor of TRH-DE to adult male rats reared in standard conditions does not change basal serum TSH concentration [

15]. Likewise, the ip injection of the TRH-DE inhibitor Glp-Asn-Pro-D-Tyr-D-TrpNH2 hardly changes basal TSH concentration in rats [

84]. In addition, other data indicate that anterior pituitary TRH-DE activity is not critical for short-term control of TRH-induced TSH release from anterior pituitary cells [

85]. Our data in mice and rats suggest that the long-term modification of ME TRH-DE activity has a limited impact on basal serum TSH and TH concentrations, probably because specific adaptations of TRH output and/or action limit change in the basal concentration of serum TSH. In agreement, tanycyte Gαq/11 KO, which reduces ME TRH-DE activity, does not modify basal HPT axis activity [

19]. Other data show that short-term ablation of the β-tanycyte layer (which is substituted by a GFAP positive glial scar) in tamoxifen inducible Rax-CreERxEno2-lsl-DTA mice promotes a small rise in serum TSH concentration while the long-term ablation does not [

86]. Finally, genome-wide association studies indicate that the approx. 100 genes relevant for setting serum TSH levels in humans do not include

Trh, nor

Trhr, nor

Trhde [

87].

5. Conclusions

When the activity of the hypophysiotropic TRH neurons is relatively stable, short-term or long-term changes in ME TRH-DE activity might not modify efficiently the amount of TRH reaching the anterior pituitary, or the efficiency of TRH at pituitary level, because of either rapid or slow adaptations at ME and/or pituitary level. However, when hypophysiotropic TRH neurons are burst-firing, these adaptations might be insufficient in front of the large amount of TRH released, making ME TRH-DE activity critical for regulating serum TSH concentration.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure S1: Activity and immunoreactivity of TRH-DE in the rat brain and serum; S2: Histochemistry of β-gal activity in the Trhde KO adult mouse brain; S3: Immunohistochemistry of β-gal in the

Trhde KO adult mouse brain. S4: Transduction sites detected with intra 3V injection of distinct AAV serotypes in rats; S5: Some AAV serotypes induced neurohypophyseal transduction when delivered into the rat 3V; S6: Effect of AAV vectors expressing TRH-DE or TRH-DEt on TRH-DE activity in COS-7 cells and in the ME; S7: Additional aspects of rat physiology were not affected by AAV1-TRH-DE or AAV1-TRH-DEt delivery in the 3V of rats in standard conditions. Additional correlations between variables. Table S1: List of experiments performed; S2: List of primary and secondary antibodies used for immunofluorescence; S3: List of primers used for PCR, RT-PCR and RT-qPCR protocols; S4: Additional effects of

Trhde genotype on C57BL/6NJ mice phenotype; S5: Patterns of transduction found after delivery of different AAV serotypes into the third ventricle of male rats.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.C., P.J.B. and A.R.R.; methodology, A.R.R., R.M.U. and A.C.V.; software, A.R.R.; validation, A.R.R. and J.L.C.; formal analysis, A.R.R. and A.C.V.; investigation, A.R.R., R.M.U., and A.C.V.; resources, J.L.C. and R.M.U.; data curation, A.R.R. and A.C.V.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R.R.; writing—review and editing, A.R.R., R.M.U., P.J.B. and J.L.C.; visualization, A.R.R.; supervision, J.L.C.; project administration, J.L.C., A.R.R., R.M.U. and A.C.V.; funding acquisition, J.L.C. and A.C.V.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Supported in part by grants from CONACYT (2014-254960 and 2015-01-562 to J.L.C.), CONAHCYT (CBF2023-2024-732 to J.L.C.) and DGAPA-UNAM (PAPITT IN206712, IN216022 and IN220825 to J.L.C., IN206416 and IN212719 to A.C.V.). MSc A. Rodríguez Rodríguez, fellow of the Postgraduate Program in Biochemical Sciences (UNAM), was supported by a fellowship from CONACYT.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institute Biosafety (application number 241010) and Bioethics (application number 276) committees.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the technical help of Dr V. Rojo León, MSc Y. Vargas, MSc A. Saralegui, BSc F. Romero, BSc E. Mata, BSc G. Cabeza and BSc JO. Arriaga.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”.

References

- Kiecker, C. The Origins of the Circumventricular Organs. Journal of Anatomy 2018, 232, 540–553, doi:10.1111/joa.12771. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, E.; Guerra, M.; Peruzzo, B.; Blázquez, J.L. Tanycytes: A Rich Morphological History to Underpin Future Molecular and Physiological Investigations. J Neuroendocrinology 2019, 31, e12690, doi:10.1111/jne.12690. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, E.M.; Blázquez, J.L.; Guerra, M. The Design of Barriers in the Hypothalamus Allows the Median Eminence and the Arcuate Nucleus to Enjoy Private Milieus: The Former Opens to the Portal Blood and the Latter to the Cerebrospinal Fluid. Peptides 2010, 31, 757–776, doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2010.01.003. [CrossRef]

- Page, R.B.; Leure-Dupree, A.E.; Bergland, R.M. The Neurohypophyseal Capillary Bed II. Specializations within Median Eminence. Am. J. Anat. 1978, 153, 33–65, doi:10.1002/aja.1001530104. [CrossRef]

- Silverman, A.J.; Hoffman, D.L.; Zimmerman, E.A. The Descending Afferent Connections of the Paraventricular Nucleus of the Hypothalamus (PVN). Brain Research Bulletin 1981, 6, 47–61, doi:10.1016/S0361-9230(81)80068-8. [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.A.; Herkenham, M. Arcuate Nucleus Neurons That Project to the Hypothalamic Paraventricular Nucleus: Neuropeptidergic Identity and Consequences of Adrenalectomy on mRNA Levels in the Rat. J of Comparative Neurology 1995, 358, 518–530, doi:10.1002/cne.903580405. [CrossRef]

- Tóth, Z.E.; Palkovits, M. Distributions of Periventricular Projections of the Paraventricular Nucleus to the Median Eminence and Arcuate Nucleus. Brain Research 1998, 802, 294–297, doi:10.1016/S0006-8993(98)00620-9. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Shlomo, A.; Melmed, S. Hypothalamic Regulation of Anterior Pituitary Function. In The Pituitary; Elsevier, 2011; pp. 21–45 ISBN 978-0-12-380926-1.

- Shioda, S.; Nakai, Y. Immunocytochemical Localization of TRH and Autoradiographic Determination of 3H-TRH-Binding Sites in the Arcuate Nucleus-Median Eminence of the Rat. Cell Tissue Res. 1983, 228, doi:10.1007/BF00211469. [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, K.; Taniguchi, Y.; Inoue, K.; Kurosumi, K.; Suzuki, M. Immunocytochemical Delineation of Thyrotrophic Area: Origin of Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone in the Median Eminence. Neuroendocrinology 1988, 47, 384–388, doi:10.1159/000124943. [CrossRef]

- Fekete, C.; Lechan, R.M. Central Regulation of Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid Axis Under Physiological and Pathophysiological Conditions. Endocrine Reviews 2014, 35, 159–194, doi:10.1210/er.2013-1087. [CrossRef]

- Joseph-Bravo, P.; Jaimes-Hoy, L.; Uribe, R.-M.; Charli, J.-L. 60 YEARS OF NEUROENDOCRINOLOGY: TRH, the First Hypophysiotropic Releasing Hormone Isolated: Control of the Pituitary–Thyroid Axis. Journal of Endocrinology 2015, 226, T85–T100, doi:10.1530/JOE-15-0124. [CrossRef]

- Chiamolera, M.I.; Wondisford, F.E. Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone and the Thyroid Hormone Feedback Mechanism. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 1091–1096, doi:10.1210/en.2008-1795. [CrossRef]

- Salas-Lucia, F.; Fekete, C.; Sinkó, R.; Egri, P.; Rada, K.; Ruska, Y.; Gereben, B.; Bianco, A.C. Axonal T3 Uptake and Transport Can Trigger Thyroid Hormone Signaling in the Brain. eLife 2023, 12, e82683, doi:10.7554/eLife.82683. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, E.; Vargas, M.A.; Singru, P.S.; Pascual, I.; Romero, F.; Fekete, C.; Charli, J.-L.; Lechan, R.M. Tanycyte Pyroglutamyl Peptidase II Contributes to Regulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid Axis through Glial-Axonal Associations in the Median Eminence. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 2283–2291, doi:10.1210/en.2008-1643. [CrossRef]

- Farkas, E.; Varga, E.; Kovács, B.; Szilvásy-Szabó, A.; Cote-Vélez, A.; Péterfi, Z.; Matziari, M.; Tóth, M.; Zelena, D.; Mezriczky, Z.; et al. A Glial-Neuronal Circuit in the Median Eminence Regulates Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone-Release via the Endocannabinoid System. iScience 2020, 23, 100921, doi:10.1016/j.isci.2020.100921. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez, A.; Lazcano, I.; Sánchez-Jaramillo, E.; Uribe, R.M.; Jaimes-Hoy, L.; Joseph-Bravo, P.; Charli, J.-L. Tanycytes and the Control of Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone Flux Into Portal Capillaries. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 401, doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00401. [CrossRef]

- Lazcano, I.; Cabral, A.; Uribe, R.M.; Jaimes-Hoy, L.; Perello, M.; Joseph-Bravo, P.; Sánchez-Jaramillo, E.; Charli, J.-L. Fasting Enhances Pyroglutamyl Peptidase II Activity in Tanycytes of the Mediobasal Hypothalamus of Male Adult Rats. Endocrinology 2015, 156, 2713–2723, doi:10.1210/en.2014-1885. [CrossRef]

- Müller-Fielitz, H.; Stahr, M.; Bernau, M.; Richter, M.; Abele, S.; Krajka, V.; Benzin, A.; Wenzel, J.; Kalies, K.; Mittag, J.; et al. Tanycytes Control the Hormonal Output of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid Axis. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 484, doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00604-6. [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, K.P.; Martin, T.F. Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone and Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Receptors Activate Phospholipase C by Coupling to the Guanosine Triphosphate-Binding Proteins Gq and G11. Molecular Endocrinology 1992, 6, 1673–1681, doi:10.1210/mend.6.10.1333052. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lu, X.; Gershengorn, M. Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone Receptors -- Similarities and Differences. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology 2003, 30, 87–97, doi:10.1677/jme.0.0300087. [CrossRef]

- Charli, J.-L.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, A.; Hernández-Ortega, K.; Cote-Vélez, A.; Uribe, R.M.; Jaimes-Hoy, L.; Joseph-Bravo, P. The Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone-Degrading Ectoenzyme, a Therapeutic Target? Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 640, doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.00640. [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Li, L.; Tang, J.; Li, Y.; Lin, W.Y.; Martin, F.; Grant, D.; Solloway, M.; Parker, L.; Ye, W.; et al. A Mouse Knockout Library for Secreted and Transmembrane Proteins. Nat Biotechnol 2010, 28, 749–755, doi:10.1038/nbt.1644. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.A.; Zhou, R. β-Galactosidase Staining of LacZ Fusion Proteins in Whole Tissue Preparations. In Neural Development; Zhou, R., Mei, L., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2013; Vol. 1018, pp. 189–197 ISBN 978-1-62703-443-2.

- Paxinos, G.; Watson, S.J. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates (2nd Edn); 2nd ed.; Academic Press, 1986; Vol. 10; ISBN 012 547 6213.

- Franklin, K.B.J.; Paxinos, G. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates; Compact 3. ed.; Elsevier Academic Press: Amsterdam Heidelberg, 2008; ISBN 978-0-12-374244-5.

- Jamur, M.C.; Oliver, C. Permeabilization of Cell Membranes. In Immunocytochemical Methods and Protocols; Oliver, C., Jamur, M.C., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2010; Vol. 588, pp. 63–66 ISBN 978-1-58829-463-0.

- Heuer, H.; Schäfer, M.K.-H.; Bauer, K. The Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone-Degrading Ectoenzyme: The Third Element of the Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone-Signaling System. Thyroid 1998, 8, 915–920, doi:10.1089/thy.1998.8.915. [CrossRef]

- Lechan, R.M.; Jackson, I.M.D. Immunohistochemical Localization of Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone in the Rat Hypothalamus and Pituitary*. Endocrinology 1982, 111, 55–65, doi:10.1210/endo-111-1-55. [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Gutiérrez, L.; Bourdais, J.; Aranda, G.; Vargas, M.A.; Matta-Camacho, E.; Ducancel, F.; Segovia, L.; Joseph-Bravo, P.; Charli, J. A Truncated Isoform of Pyroglutamyl Aminopeptidase II Produced by Exon Extension Has Dominant-negative Activity. Journal of Neurochemistry 2005, 92, 807–817, doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02916.x. [CrossRef]

- Bianco, A.C.; Anderson, G.; Forrest, D.; Galton, V.A.; Gereben, B.; Kim, B.W.; Kopp, P.A.; Liao, X.H.; Obregon, M.J.; Peeters, R.P.; et al. American Thyroid Association Guide to Investigating Thyroid Hormone Economy and Action in Rodent and Cell Models: Report of the American Thyroid Association Task Force on Approaches and Strategies to Investigate Thyroid Hormone Economy and Action. Thyroid 2014, 24, 88–168, doi:10.1089/thy.2013.0109. [CrossRef]

- Joseph-Bravo, P.; Charli, J.L.; Palacios, J.M.; Kordon, C. Effect of Neurotransmitters on the in Vitro Release of Immunoreactive Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone from Rat Mediobasal Hypothalamus*. Endocrinology 1979, 104, 801–806, doi:10.1210/endo-104-3-801. [CrossRef]

- Joseph-Bravo, P.; Lazcano, I.; Jaimes-Hoy, L.; Gutierrez-Mariscal, M.; Sanchez-Jaramillo, E.; Uribe, R.M.; Charli, J.-L. Sexually Dimorphic Dynamics of Thyroid Axis Activity during Fasting in Rats. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2020, 25, 1305–1323, doi:10.2741/4857. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.A.; Slator, G.R.; Tipton, K.F.; Williams, C.H.; Bauer, K. Development of a Continuous, Fluorometric Coupled Enzyme Assay for Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone-Degrading Ectoenzyme. Analytical Biochemistry 1999, 274, 195–202, doi:10.1006/abio.1999.4276. [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Gutiérrez, L.; Matta-Camacho, E.; Osuna, J.; Horjales, E.; Joseph-Bravo, P.; Maigret, B.; Charli, J.-L. Homology Modeling and Site-Directed Mutagenesis of Pyroglutamyl Peptidase II: Insights into Omega-versus Aminopeptidase Specificity in the M1 Family. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2006, 281, 18581–18590.

- Limaye, A.; Cho, K.; Hall, B.; Khillan, J.S.; Kulkarni, A.B. Genotyping Protocols for Genetically Engineered Mice. Current Protocols 2023, 3, e929, doi:10.1002/cpz1.929. [CrossRef]

- Chomzynski, P.; Sacchi, N. Single-Step Method of RNA Isolation by Acid Guanidinium Thiocyanate–Phenol–Chloroform Extraction. Analytical Biochemistry 1987, 162, 156–159, doi:10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [CrossRef]

- Cote-Vélez, A.; Martínez Báez, A.; Lezama, L.; Uribe, R.M.; Joseph-Bravo, P.; Charli, J.-L. A Screen for Modulators Reveals That Orexin-A Rapidly Stimulates Thyrotropin Releasing Hormone Expression and Release in Hypothalamic Cell Culture. Neuropeptides 2017, 62, 11–20, doi:10.1016/j.npep.2017.01.005. [CrossRef]

- Uribe, R.Ma.; Pérez-Martínez, L.; De Lourdes^Covarrubias, Ma.; Gómez, O.; Covarrubias, L.; Charli, J.L.; Joseph-Bravo, P. Phorbol Ester or cAMP Enhance Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone mRNA in Primary Cultures of Hypothalamic Cells. Neuroscience Letters 1995, 201, 41–44, doi:10.1016/0304-3940(95)12125-N. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Martínez, L.; Carreón-Rodríguez, A.; González-Alzati, Ma.E.; Morales, C.; Charli, J.L.; Joseph-Bravo, P. Dexamethasone Rapidly Regulates TRH mRNA Levels in Hypothalamic Cell Cultures: Interaction with the cAMP Pathway. Neuroendocrinology 1998, 68, 345–354, doi:10.1159/000054383. [CrossRef]

- Team, R.C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria 2013.

- Wilke, C.O. Cowplot: Streamlined Plot Theme and Plot Annotations for’ggplot2’. CRAN: Contributed Packages 2020.

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. JOSS 2019, 4, 1686, doi:10.21105/joss.01686. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, K. Regulation of Degradation of Thyrotropin Releasing Hormone by Thyroid Hormones. Nature 1976, 259, 591–593, doi:10.1038/259591a0. [CrossRef]

- Schmitmeier, S.; Thole, H.; Bader, A.; Bauer, K. Purification and Characterization of the Thyrotropin-releasing Hormone (TRH)-degrading Serum Enzyme and Its Identification as a Product of Liver Origin. European Journal of Biochemistry 2002, 269, 1278–1286, doi:10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02768.x. [CrossRef]

- Lein, E.S.; Hawrylycz, M.J.; Ao, N.; Ayres, M.; Bensinger, A.; Bernard, A.; Boe, A.F.; Boguski, M.S.; Brockway, K.S.; Byrnes, E.J.; et al. Genome-Wide Atlas of Gene Expression in the Adult Mouse Brain. Nature 2007, 445, 168–176, doi:10.1038/nature05453. [CrossRef]

- Haan, N.; Goodman, T.; Najdi-Samiei, A.; Stratford, C.M.; Rice, R.; El Agha, E.; Bellusci, S.; Hajihosseini, M.K. Fgf10-Expressing Tanycytes Add New Neurons to the Appetite/Energy-Balance Regulating Centers of the Postnatal and Adult Hypothalamus. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 6170–6180, doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2437-12.2013. [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Wani, M.A.; Wight, D.; Kopchick, J.; Stambrook, P.J. Reporter Genes in Transgenic Mice. Transgenic Research 1994, 3, 182–194, doi:10.1007/BF01973986. [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, L.; Theis, M.; Alvarez-Maya, I.; Brenner, M.; Willecke, K.; Messing, A. hGFAP-cre Transgenic Mice for Manipulation of Glial and Neuronal Function in Vivo. Genesis 2001, 31, 85–94, doi:10.1002/gene.10008. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, T.C.; Wilk, S. The Effect of Inhibitors of Prolyl Endopeptidase and Pyroglutamyl Peptide Hydrolase on TRH Degradation in Rat Serum. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 1985, 132, 787–794, doi:10.1016/0006-291X(85)91201-X. [CrossRef]