Submitted:

13 February 2025

Posted:

17 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

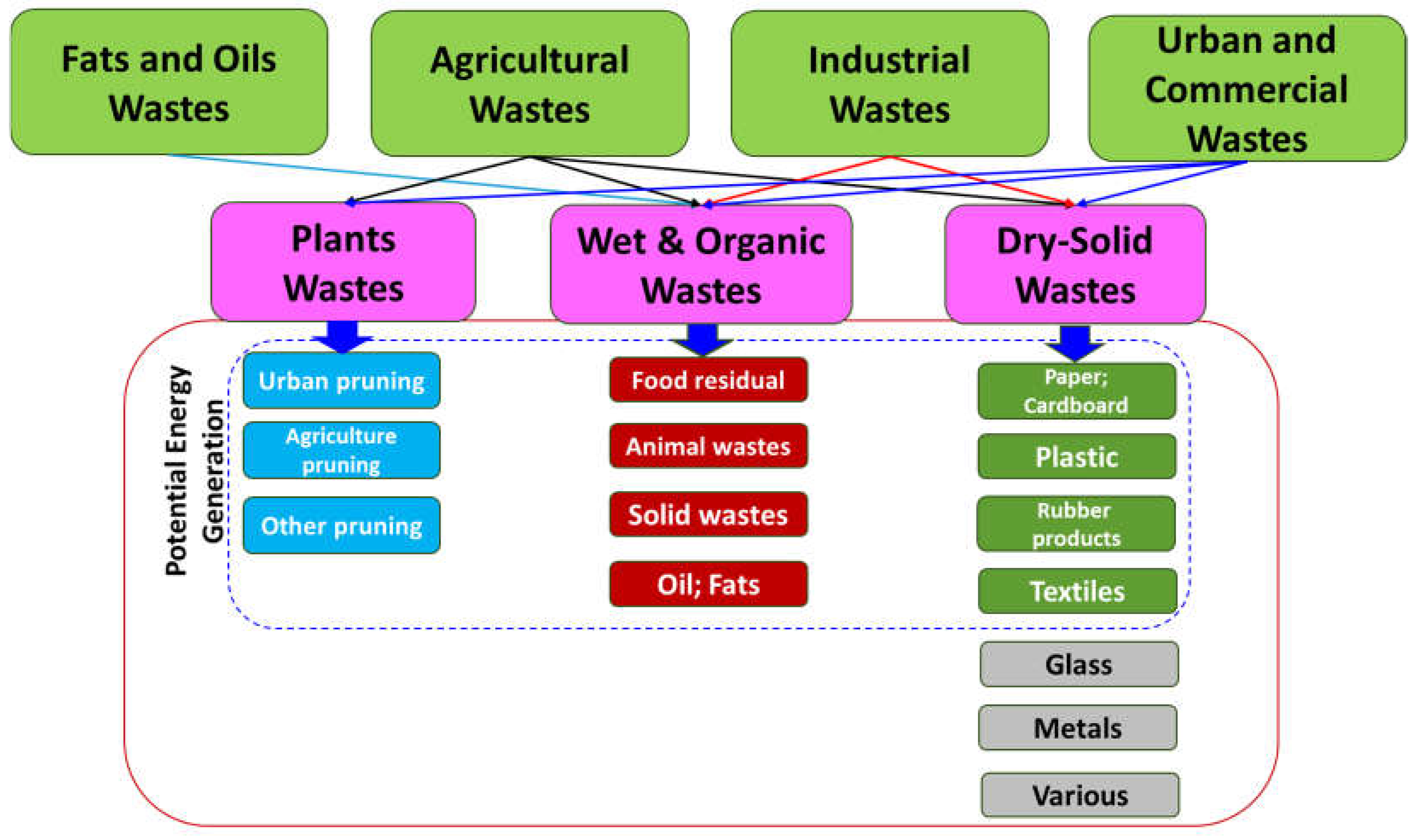

1.1. Types of Solid Waste

1.2. Pruning Waste

1.2.1. Reuse Options

1.2.2. Mulching

1.2.3. Composting

1.2.4. Improving Soil Properties by Adding Amendments

1.2.5. Biochar Generation

1.2.6. Disease and Pest Management

1.2.7. Carbon Sequestration

1.2.8. Sustainable Farming Practice

1.2.9. Food Sources

1.3. Energy

1.3.1. Bioenergy Production

1.3.2. Pyrolysis

1.3.3. Combustion

1.3.4. Incineration

1.4. Economic Aspects

2. The Purpose of the Work

3. Materials and Methods

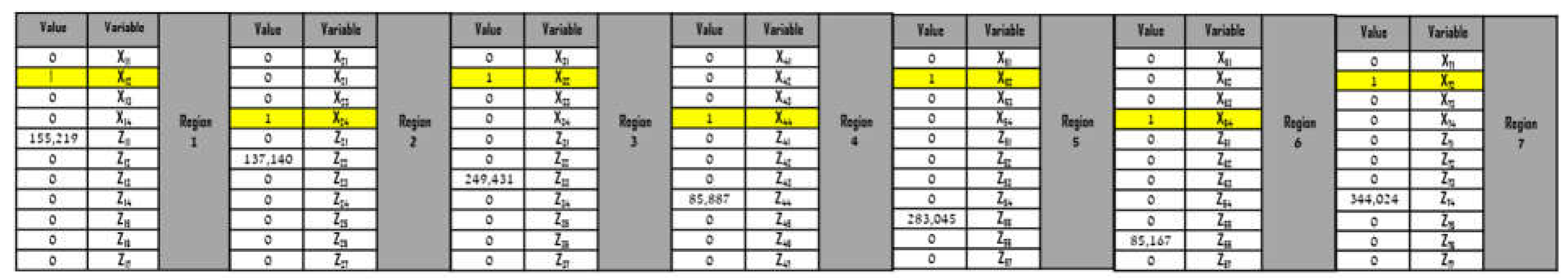

3.1. The Variables

3.2. The Objective Function

3.3. The Constraints

3.4. The Treatment Facilities

4. Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Park, J.W.; Shin, H.C. Surface emission of landfill gas from solid waste landfill. Atmospheric Environment 2001, 35(20), 3445-3451.–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, H.; Meng, H.; Chen, M.; Song, W.; Xing, H. Co-processing paths of agricultural and rural solid wastes for a circular economy based on the construction concept of “zero-waste city” in China. Circular Economy 2023, 2, 1-10, 100065.

- Chen, C.; Zhai, M.; Wang, X.; Li, W.; Xu, Y.; Bao, Z. Analysis of the dynamics of common industrial solid waste based on input–output: A case study of Shanghai international metropolis in China. Waste Management 2024, 177, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, A.R.G.; Salomon, M.J.; Lowe, A.J.; Cavagnaro, T.R. Review microbial solutions to soil carbon sequestration. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 417, 1-10, 137993.

- Yu, H.; Zahidi, I.; Fai, C.M.; Liang, D.; Madsen, D.O. Mineral waste recycling, sustainable chemical engineering, and circular economy. Results in Engineering 2024, 21, 1-8, 101865.

- Ramírez-Márquez, C.; Posadas-Paredes, T.; Raya-Tapia, A.Y.; Ponce-Ortega, J.M. Natural resource optimization and sustainability in society 5.0: a comprehensive review. Resources MDPI 2024, 13, 1-20, 19, https://doi.org/10.3390/resources13020019, https://www.mdpi.com/journal/resources.

- Shah, P.; Yang, J.Z. When virtue is its own reward: How norms influence consumers’ willingness to recycle and reuse. Environmental Development 2023, 48, 1-11, 100928, www.elsevier.com/locate/envde.

- Muscas, D.; Orlandi, F.; Petrucci, R.; Proietti, C.; Ruga, L.; Fornaciari, M. Effects of urban tree pruning on ecosystem services performance. Trees, Forests and People 2024, 15, 1-9, 100503.

- Gertsakis, J.; Lewis, H. Sustainability and the waste management hierarchy: A discussion paper on the waste management hierarchy and its relationship to sustainability. Product Stewardship Centre of Excellence, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology PO Box 123, Broadway NSW 2007, 2003, p-25, www.stewardshipexcellence.com.au.

- Mpofu, A.B.; Kaira, W.M.; Oyekola, O.O.; Welz, P.J. Anaerobic co-digestion of tannery effluents: Process optimisation for resource recovery, recycling and reuse in a circular bioeconomy. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2022, 158, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Zeng, X.; Zheng, K.; Zeng, Z.; Dai, C.; Huo, X. Risk assessment and partitioning behavior of PFASs in environmental matrices from an e-waste recycling area. Sci. of the Total Environment 2023, 905, 1-10, 16770.

- Gordon, A.M.; Matilla, A.L.; Barrio, M.I.P.; Escamilla, A.C. From waste to resource: Exploring the recyclability and performance of gypsum-graphene nanofiber composites. Resources, Conservation & Recycling Advances 2024, 23, 1-12, 200222.journal homepage: www.sciencedirect.com/journal/.

- Liu, X.; Asghari, V.; Lam, C-M.; Hsu, S-C.; Xuana, D.; Angulo, S.C.; John, V.M.; Basavaraj, A.S.; Gettu, R.; Xiao, J.; Poon, C-S.; Review discrepancies in life cycle assessment applied to concrete waste recycling: A structured review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 434, 1-18, 140155.

- Guo, L.; Jina, Y.; Xiaoc, Y.; Tana, L.; Tiana, X.; Dinga, Y.; Hea, K.; Dua, A.; Lia, J.; Yia, Z.; Wange, S.; Fanga, Y.; Zhaoa, H. Energy-efficient and environmentally friendly production of starchrich duckweed biomass using nitrogen-limited cultivation. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 251, 1-10, 119726.

- Sang, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Wu, T.; Xiang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Guan, W.; Xu, J.; Maorong, C.M.; Singhal, S.C. Energy harvesting from algae using large-scale flat-tube solid oxide fuel cells. Cell Reports Physical Science 2023, 4, 1-19, 101454.

- Lavagi, V.; Kaplan, J.; Vidalakis, G.; Ortiz, M.; Rodriguez, M.V.; Amador, M.; Hopkins, F.; Ying, S.; Pagliaccia, D. Recycling agricultural waste to enhance sustainable greenhouse agriculture: Analyzing the cost-effectiveness and agronomic benefits of bokashi and biochar byproducts as soil amendments in citrus nursery production. Sustainability MDPI 2024, 16, 1-16, 6070.

- Vijaya, A.; Meisterknecht, J.P.S.; Angreani, L. S.; Wicaksono, H. Advancing sustainability in the automotive sector: A critical analysis of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance indicators. Cleaner Environmental Systems 2025, 16, 1-17, 100248, www.journals.elsevier.com/cleaner-environmental-systems.

- Verter, V.; Boyaci, T.; Galbreth, M. Design for reusability and product reuse under radical innovation. Sustainability Analytics and Modeling 2023, 3, (1-14, 100021, www.journals.elsevier.com/sustainability-analytics-and-modeling.

- Bubinek, R.; Knaack, U.; Cimpan, C. Reuse of consumer products: Climate account and rebound effects potential. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2025, 54, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dtie, U.N.E.P.; Converting waste agricultural biomass into a resource. Compendium of Technologies 2009, Osaka, United Nations Environment Program.

- Grohmann, D.; Petrucci, R.; Torre, L.; Micheli, M.; Menconi, M.E. Street trees’ management perspectives: Reuse of Tilia sp.’s running waste for insulation purposes. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2019, 38, 177-182.

- Lago, A.; Sanz, M.; Gordón, J.M.; Fermoso, J.; Pizarro, P.; Serrano, D.P.; Moreno, I. Enhanced production of aromatic hydrocarbons and phenols by catalytic co-pyrolysis of fruit and garden pruning wastes. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2022, 10, 1-9, 107738.

- Kougioumtzis, M.A.; Tsiantzi, S.; Athanassiadou, E.; Karampinis, E.; Grammelis, P.; Kakaras, E. Valorization of olive tree pruning for the production of particleboards. Evaluation of the particleboard properties at different substitution levels. Industrial Crops and Products 2023, 204-part B, 1-10, 117383.

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zheng, J.; Liu, E.; Feng, L.; Feng, C.; Si, P.; Bai, W.; Cai, Q.; Yang, N.; van der-Werf, W.; Zhang, L. ; Plastic film cover during the fallow season preceding sowing increases yield and water use efficiency of rain-fed spring maize in a semi-arid climate. Agricultural Water Management 2019, 212, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, R.; Raza, M.A.S.; Valipour, M.; Saleem, M.F.; Zaheer, M.S.; Ahmad, S.; Toleikiene, M.; Haider, I.; Aslam, M.U.; Nazar, M.A. Potential agricultural and environmental benefits of mulches-a review. Bulletin of the National Research Centre 2020, 44(75), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Jia, G.; Wang, Y.; Yu, X. The effectiveness of mulching practices on water erosion control: A global meta-analysis. Geoderma 2023, 438, 1-20, 116643.

- Sapakhova, Z.; Islamb, K.R.; Toishimanov, M.; Zhapar, K.; Daurov, D.; Daurova, A.; Raissova, N.; Kanat, R.; Shamekova, M.; Zhambakin, K. Mulching to improve sweet potato production. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2024, 15, 1-10, 101011.

- Teutscherova, N.; Vazquez, F.; Santana, D.; Navas, M.; Masaguer, A.; Benito, M. Influence of pruning waste compost maturity and biocharon carbon dynamics in acid soil: Incubation study. European Journal of Soil Biology 2017, 78, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cestonaro, T.; de Vasconcelos-Barros, R.T.; de Matos, A.T.; Costa, M.A. Full scale composting of food waste and tree pruning: How large is the variation on the compost nutrients over time ?. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 754, 1-8, 142078.

- Li, M.; Li, F.; Zhou, J.; Yuan, Q.; Hu, N. Fallen leaves are superior to tree pruning as bulking agents in aerobic composting disposing kitchen waste. Bioresource Technology 2022, 346, 1-9, 126374.

- Garcia-Franco, N.; Wiesmeier, M.; Hurtarte, L.C.C.; Fella, F.; Martínez-Mena, M.; Almagro, M.; Martínez, E.G.; Kögel-Knabner, I. Pruning residues incorporation and reduced tillage improve soil organic matter stabilization and structure of salt-affected soils in a semi-arid Citrus tree orchard. Soil & Tillage Research 2021, 213, 1-11, 105129.

- Taguas, E.V.; Marín-Moreno, V.; Díez, C.M.; Mateos, L.; Barranco, D.; Mesas-Carrascosa, F-J.; García-Ferrera, R.P.A.; Quero, J.L. Opportunities of super high-density olive orchard to improve soil quality: Management guidelines for application of pruning residues. Journal of Environmental Management 2021, 293, 1-12, 112785. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

- Ahmed, M.B.; Zhou, J.L.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W. Insight into biochar properties and its cost analysis. Biomass and Bioenergy 2016, 84, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Mendoza-Perilla, P.; Clavier, K.A.; Tolaymat, T.M.; Bowden, J.A.; Solo-Gabriele, H.M.; Townsend, T.G. Municipal solid waste incineration MSWI) ash co-disposal: Influence on per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances PFAS) concentration in landfill leachate. Waste Management 2022, 144, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-Aguiar, E.; Gasco’, G.; Lado, M.; Méndez, A.; Paz-Ferreiro, J.; Paz-Gonzalez, A. New insights into the production, characterization and potential uses of vineyard pruning waste biochars. Waste Management 2023, 171, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguès, I.; Miritana, V.M.; Passatore, L.; Zacchini, M.; Peruzzi, E.; Carloni, S.; Pietrini, F.; Marabottini, R.; Chiti, T.; Massaccesi, L.; Marinari, S. Biochar soil amendment as carbon farming practice in a Mediterranean environment. Geoderma Regiona 2023, l33, 1-14, e00634, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

- Ruan, R.; Wang, Y. Effects of biochar amendment on root growth and plant water status depend on maize genotypes. Agricultural Water Management 2024, 293, 1-11, 108688.

- Shahrun, M.S.; Abdul-Rahman, M.H.; Baharom, N.A.; Jumat, F.; Saad, M.J.; Mail, M.F.; Zawawi, N.N.; Suherman, F.H.S. Design of a pyrolysis system and the characterization data of biochar produced from coconut shells, carambola pruning, and mango pruning using a low-temperature slow pyrolysis process. Data in Brief 2024, 52, 1-11, 109997.

- Acosta, A.C.; C.A.; Biller, P.; Sørensen, P.; Marulanda, V.F.; Brix, H. Optimizing resource efficiency through hydrothermal carbonization and engineered wetland systems: A study on carbon sequestration and phosphorus recovery potential. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Aare, A.K.; Lund, S.; Hauggaard-Nielsen, H. Exploring transitions towards sustainable farming practices through participatory research-the case of Danish farmers’ use of species mixtures. Agricultural Systems 2021, 189, 103053. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Espinosa, T.; Papamichael, I.; Voukkali, I.; Gimeno, A.P.; Candel, M.B.A.; Navarro-Pedreño, J.; Zorpas, A.A.; Lucas, I.G. Nitrogen management in farming systems under the use of agricultural wastes and circular economy. Science of the Total Environment 2023, 876, 162666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-Martí, B.; Fernández-González, E.; López-Cortés, I.; Salazar-Hernández, D.M. Quantification of the residual biomass obtained from pruning of vineyards in Mediterranean area. Biomass and Bioenergy 2011, 35, 3453–3464. [Google Scholar]

- Dangulla, M.; Manaf, L.A.; Aliero, M.M. The contribution of small and medium diameter trees to biomass and carbon pools in Yabo, Sokoto State, Nigeria. Academia Environmental Science and Sustainability 2025, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodato, C.; Hamelin, L.; Tonini, D.; Astrup, T.F. Towards sustainable methane supply from local bioresources: Anaerobic digestion, gasification, and gas upgrading. Applied Energy 2022, 323, 119568, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Han, L. Influence of pyrolysis temperature on chemical speciation, leaching ability, and environmental risk of heavy metals in biochar derived from cow manure. Bioresource Technology 2020, 302, 122850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taboada-Ruiz, L.R.; Pardo, R.; Ruiz, B.; Díaz-Somoano, M.; Calvo, L.F.; Paniaguac, S.; Fuentea, E. Progress and challenges in valorization of biomass waste from ornamental trees pruning through pyrolysis processes. Prospects in the bioenergy sector. Environmental Research 2024, 249, 118388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaidis, P.; Poullikkas, A. A comparative overview of hydrogen production processes. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 67, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van-Pinxteren, D.; Engelhardt, V.; Mothes, F.; Poulain, L.; Fomba, K.W.; Spindler, G.; Cuesta-Mosquera, A.; Tuch, T.; Müller, T. Wiedensohler, A.; Loschau, G.; Bastian, S.; Herrmann, H. Residential wood combustion in Germany: A twin-site study of local village contributions to particulate pollutants and their potential health effects. ACS Environmental Au. 2024, 4, 1.

- Wang, Z., Li, P., Cai, W., Shi, Z., Liu, J., Cao, Y., Li, W., Wu, W., Li, L., Liu, J., Zheng, T. Identifying administrative villages with an urgent demand for rural domestic sewage treatment at the county level: decision making from China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 800. [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Liu, T-S. ; Yao, M.; Yi, X.; Bai, G-X.; Huanga, Q-R.; Li, Z. Comparative study of the combustion and kinetic characteristics of fresh and naturally aged pine wood. Fuel 2023, 343, 127962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kougioumtzis, M.A.; Kanaveli, I.P.; Karampinis, E.; Elis, P.G.; Kakaras, E. Combustion of olive tree pruning pellets versus sunflower husk pellets at industrial boiler. Monitoring of emissions and combustion efficiency. Renewable Energy 2021, 171, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.S.; Leinweber, P. Effects of pyrolysis and incineration on the phosphorus fertilizer potential of bio-waste-and plant-based materials. Waste Management 2023, 172, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadlovec, M.; Výtisk, J.; Honus, S.; Pospišilík, V.; Bassel, N. Pollutants production, energy recovery and environmental impact of sewage sludge co-incineration with biomass pellets. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2023, 32, 103400, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

- Zu, L.; Wu, D.; Lyu, S. How to move from conflict to opportunity in the not-in-my-backyard dilemma: A case study of the Asuwei waste incineration plant in Beijing. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2024, 104, 107326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, F.; Zhou, J.; Yuan, Q.; Hu, N. Fallen leaves are superior to tree pruning as bulking agents in aerobic composting disposing kitchen waste. Bioresource Technology 2022, 346, 126374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medic, D. Investigation of torrefaction process parameters and characterization of torrefied biomass. A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Iowa State University, thesis 2012, p-128, Ames, Iowa.

- Feofilova, E.P.; Mysyakina, I.S. Lignin: chemical structure, biodegradation, and practical application a review. Appl. Biochemistry and Microbiology 2016, 52, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassoni, A.C.; Costa, P.; Mota, I.; Vasconcelos, M.W.; Pintado, M. Recovery of lignins with antioxidant activity from Brewer’s spent grain and olive tree pruning using deep eutectic solvents. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2023, 192, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavinato, C.; Fatone, F.; Bolzonella, D.; Pavan, P. Thermophilic anaerobic co-digestion of cattle manure with agro-wastes and energy crops: comparison of pilot and full-scale experiences. Bioresource Technology 2015, 101, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón, E.; Espinosa, E.; García-Domínguez, M.T.; Balu, A.M.; Vilaplana, F.; Serrano, L.; Jimẻnez-Quero, A. Bioactive pectic polysaccharides from bay tree pruning waste: Sequential subcritical water extraction and application in active food packaging. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 272, 118477, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

- Vercruysse, W.; Derison, F.; Joos, B.; Hardy, A.; Hamed, H.; Schreurs, S. Biomass residue streams as potential feedstocks for the production of activated-carbon-based electrodes for supercapacitors. ACS Sustainable Resources Management 2024, 1, 124-132.

- Amchova, P.; Siska, F.; Ruda-Kucerova, J. Food safety and health concerns of synthetic food colors: an update. Toxics 2024, 12, 466–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, S.; Pow, D.; Dawson, K.; Mitchell, D.R.G.; Rawal, A.; Hook, J.; Taherymoosavi, S.; Van-Zwieten, L.; Rust, J.; Donne, S.; Munroe, P.; Pace, B.; Graber, E.; Thomas, T.; Nielsen, S.; Ye, J.; Lin, Y.; Pan, G.; Lin, L.; Solaiman, Z.M. Feeding biochar to cows: an innovative solution for improving soil fertility and farm productivity. Pedosphere 2015, 25, 666–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, D.; Sarswat, A.; Ok, Y.S.; Pittman Jr, C.U. Organic and inorganic contaminants removal from water with biochar, a renewable, low cost and sustainable adsorbent–a critical review. Bioresource Technology 2014, 160, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saygin, D.; Gielen, D.J.; Draeck, M.; Worrell, E.; Patel, M.K. Assessment of the technical and economic potentials of biomass use for the production of steam, chemicals and polymers. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2014, 40, 1153–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, L.O.; Aigbavboa, C.; Adepoju, O.; Nnamdi, N. Applying circular economy strategies in mitigating the perfect storm: The built environment context. Sustainable Futures 2025, 9, 100444, www.sciencedirect.com/journal/sustainable-futures.

- Broitman, D.; Raviv, O.; Ayalon, O.; Kan, I. Designing an agricultural vegetative waste-management system under uncertain prices of treatment-technology output products. Waste Management 2018, 75, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, L.J.; Pinto, A.S.S.; Arshad, M.N.; Rowe, R.L.; Donnison, I.; McManus, M. Techno-economic and life cycle assessments of waste recovery for crop growth in glasshouses. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 432, 139650, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

- Díaz, L.; Seoñrans, S.; González, L.A.; Escalante, D.J. Assessment of the energy potential of agricultural residues in the Canary Islands: Promoting circular economy through bioenergy production. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 437, 140735, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/bync-nd/4.0/.

- Kan, I.; Rapaport-Rom, M. Regional blending of fresh and saline irrigation water : Is it efficient? Water Resources Research 2012, 48, W07517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LINGO, 2015. The modeling language and optimizer. Lingo Systems Inc., 1415 North Dayton Street, Chicago, Illinois 60642, Technical Support: 312, 988-9421, E-mail: tech@lindo.com WWW: http://www.lindo.com.

| Treatment method | The process | Percentage of pruning waste | Product outcome and results |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mulching | Shredding for soil cover using straw, polyethylene, and plastic | 100 | Maintaining soil moisture and temperature | [24,25,26,27] |

| Composting | Anaerobic wastes: sorting to desired calories; minimal contamination | 30–35 | Soil amendment: increased carbon addition & disease reduction | [28,29,30,55] |

| Bio charcoaling | Closed thermochemical: 200oC–300oC; similar to pyrolysis | 100 | Additive for electricity generation and heating | [33,35,36,37,38,56] |

| Food production | Extracted polysaccharides; lignin | 40–60 | Supplementary food for humans | [58,59,60,61,62] |

| Animal feed |

Mixing according to ratio and animal species |

10–50 | Wet food as a substitute for fodder | [63] |

| Pyrolysis | Anaerobic conversion of biomass: thermochemical: 300oC–900oC | 100 | Heat for local use; biochar | [33,38,46,64] |

| Combustion | High-temperature burning | 100 | Fuel; rocket propulsion | [23,50] |

| Incineration | Heating primarily hazardous solid wastes | 100 | Flue gas; heating source | [52,53] |

| Anaerobic digestion | Thermophilic: bacterial dismantling at 50oC–60oC | 20–50 |

Biogas for electricity; low-quality compost |

[59] |

| Steam generation | Biomass burning; fertilizers | 100 | Steam for industrial plants | [65] |

| Geographical region |

Geographical–agricultural subdistrict | Agricultural areas, ha |

Residual pruning wastes, ton/year | Residual regional pruning wastes, ton/year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 Northeast |

Golan | 8,249 | 54,857 | 155,219 |

| Zefat | 17,863 | 85,692 | ||

| The Jordan Valley | 3,206 | 14,670 | ||

|

2 Northwest |

Acre | 21,416 | 79,911 | 137,140 |

| Hadera–Haifa | 13,811 | 57,229 | ||

|

3 North |

Kinneret | 15,930 | 72,498 | 249,431 |

| Jezrael | 38,338 | 176,933 | ||

|

4 Center |

The Sharon | 10,896 | 54,088 | 85,887 |

| Petach-Tikva | 7,948 | 31,799 | ||

|

5 Southwest |

Ashkelon | 48,674 | 220,791 | 283,045 |

| Rehovot–Tel Aviv | 12,699 | 62,254 | ||

|

6 Southeast |

Jerusalem | 6,927 | 48,085 | 85,167 |

| Ramla | 8,537 | 37,082 | ||

|

7 South |

Beer-Sheva-Besor | 74,341 | 323,739 | 344,024 |

| Arava-Dead Sea | 4,386 | 20,285 |

| Dimension and definitions of variables/comments | Meaning of designation | Parameter designation |

|---|---|---|

| i = 1,……,N 1 – North-East 2 – North-West 3 – North 4 – Center 5 – South-West 6 – South-East 7 – South |

Number of geographic regions. | N |

| j = 1,……..,F 1 – Composting 2 – Mulching 3 – Steam generation 4 – Biochar production |

Number of alternative treatment options. | F |

| Ton per year | Annual Amount of generated pruning in the i region. | wi |

| Ton per year | Maximal capacity of treatment facility of type j. | cj |

| Supplementary binary variable |

|

bi |

| US per ton |

Revenue from sale of the new product accepted at treatment site j (out of all raw material entered into the facility). | Pj |

| US per ton |

Mean investment in treating the pruning wastes in facility j. | vj |

| US per ton |

Operating and maintenance expenses in treating the pruning wastes in facility j. | oj |

| Distances kilometer (km) based on mean values between district i and district k. | Mean weight distance of pruning wastes transportation from region i to region k. | dik |

| US Dollars per ton per km | Cost of transporting the pruning wastes to the treatment facility. | tc |

| Treatment facility type j | Treatment type | Maximal capacity, ton/year, cj | Mean investment in treatment facility, USD/ton, vj | Operation and maintenance expenses, USD/ton, oj | Final value of product, USD/ton pj |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Compost preparation | 54,000 | 19 | 37 | 78 |

| 2 | Crushing and soil mulching and/or crumbling into the soils | 902,000 | 6 | 7 | 15 |

| 3 | Steam generation by | 120,000 | 11 | 31 | 39 |

| raw material burning | |||||

| 4 | Pyrolysis for bio-charcoal production | 150,000 | 13 | 58 | 120 |

| North-East | North-West | North | Center | South-West | South-East | South | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region of Recycling | Golan | Zefat | The Jordan | Accre | Hadera+ Haifa |

Kinneret | Jezrael | The Sharon | Petach Tikva | Ashkelon | Rehovot+ Tel-Aviv |

Jerusalem | Ramla | Beer-Sheva | The Arava |

|

| Golan | 37 | 94 | 87 | 118 | 84 | 99 | 147 | 204 | 218 | 204 | 190 | 189 | 247 | 322 | ||

| 1 | Zefat | 37 | 84 | 70 | 102 | 69 | 84 | 133 | 149 | 203 | 190 | 177 | 175 | 234 | 311 | |

| North-East | The Jordan | 94 | 84 | 76 | 73 | 43 | 47 | 79 | 99 | 148 | 133 | 117 | 116 | 174 | 249 | |

| 2 North-West | Accre | 87 | 70 | 76 | 58 | 54 | 56 | 100 | 112 | 166 | 157 | 153 | 148 | 205 | 287 | |

|

Hadera +Haifa |

118 | 102 | 73 | 58 | 60 | 47 | 66 | 74 | 129 | 120 | 120 | 114 | 169 | 253 | ||

|

3 North |

Kinneret | 84 | 69 | 43 | 54 | 60 | 36 | 84 | 101 | 154 | 141 | 130 | 127 | 186 | 265 | |

| Jezrael | 99 | 84 | 47 | 56 | 47 | 36 | 70 | 86 | 140 | 127 | 119 | 115 | 173 | 253 | ||

|

4 Center |

The Sharon | 147 | 133 | 79 | 100 | 66 | 84 | 70 | 41 | 91 | 78 | 75 | 69 | 125 | 208 | |

| Petach Tikva | 204 | 149 | 99 | 112 | 74 | 101 | 86 | 41 | 76 | 67 | 75 | 67 | 117 | 201 | ||

|

5 South-West |

Ashkelon | 218 | 203 | 148 | 166 | 129 | 154 | 140 | 91 | 76 | 40 | 72 | 65 | 72 | 155 | |

|

Rehovot+ Tel-Aviv |

204 | 190 | 133 | 157 | 120 | 141 | 127 | 78 | 67 | 40 | 53 | 45 | 71 | 156 | ||

|

6 South -East |

Jerusalem | 190 | 177 | 117 | 153 | 120 | 130 | 119 | 75 | 75 | 72 | 53 | 30 | 78 | 155 | |

| Ramla | 189 | 175 | 116 | 148 | 114 | 127 | 115 | 69 | 67 | 65 | 45 | 30 | 79 | 159 | ||

|

7 South |

Beer-Sheva | 247 | 234 | 174 | 205 | 169 | 186 | 173 | 125 | 117 | 72 | 71 | 78 | 79 | 105 | |

| The Arava | 322 | 311 | 249 | 287 | 253 | 265 | 253 | 208 | 201 | 155 | 156 | 155 | 159 | 105 | ||

| Location of Recyling Facility | Use of Recycled PWs (Objective function - 10,358,879 $/year) |

|---|---|

|

Facility to be contructed in region 1 – Northe-East |

Soil multhcing |

|

Facility to be contructed in region 2– Northe-West |

Pyrolysis for bio-charcoal production |

|

Facility to be contructed in region 3 – Northe |

Soil multcjing |

|

Facility to be contructed in region 4 – Center |

Pyrolysis for bio-charcoal production |

|

Facility to be contructed in region 5 – South-West |

Soil multching |

|

Facility to be contructed in region 6 – Souothe-East |

Pyrolysis for bio-charcoal production |

|

Facility to be contructed in region 7 – South |

Soil multching |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).