Submitted:

13 February 2025

Posted:

16 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

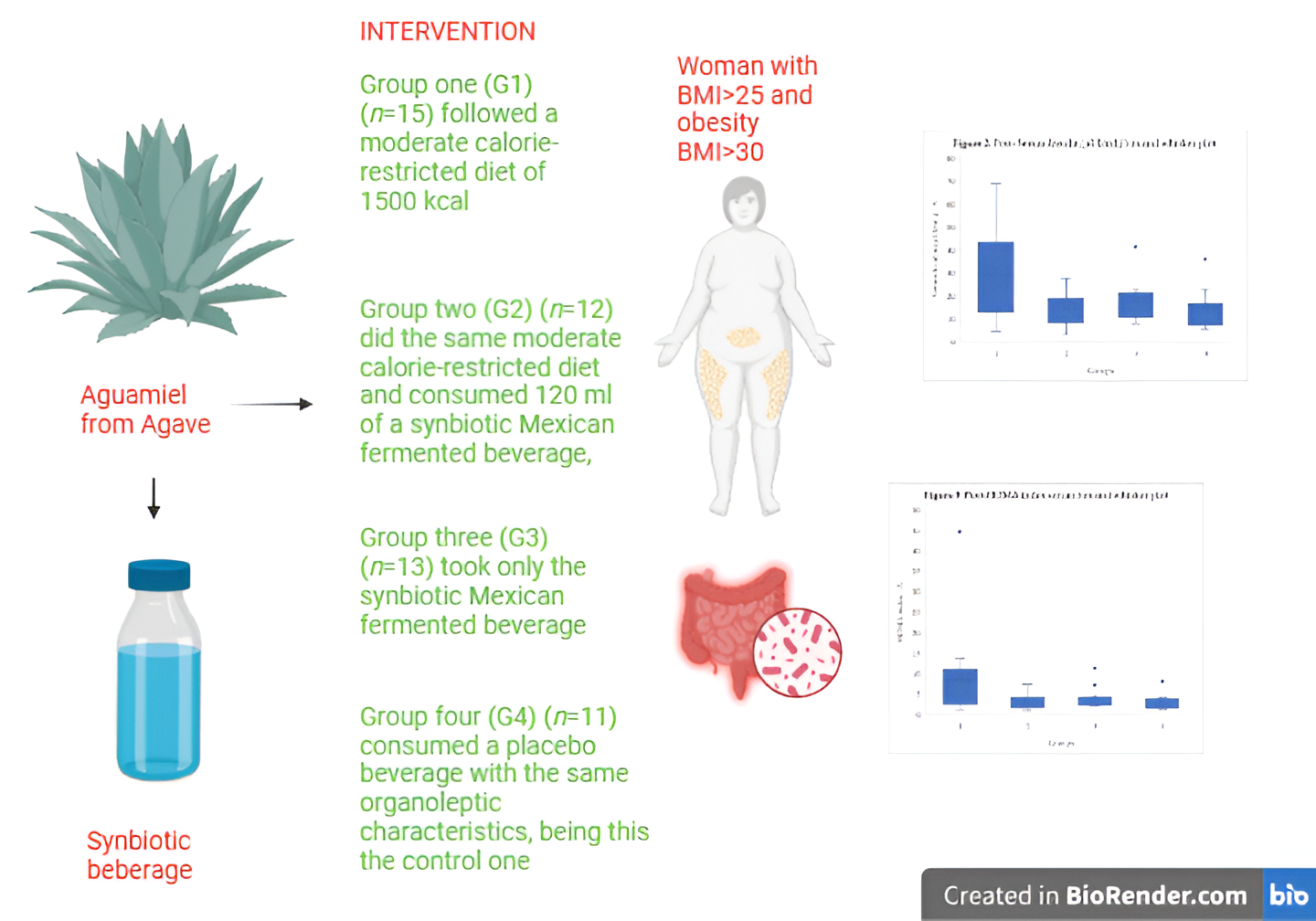

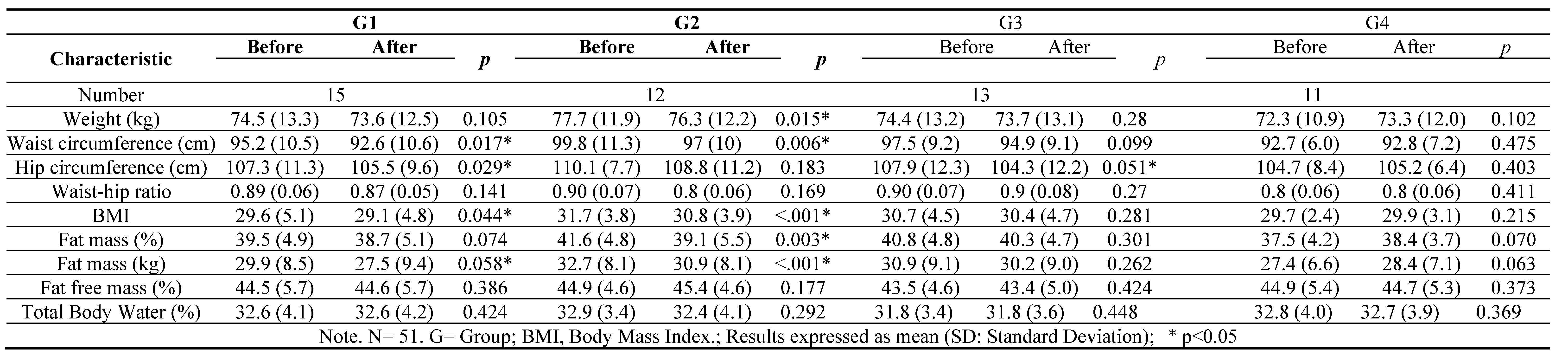

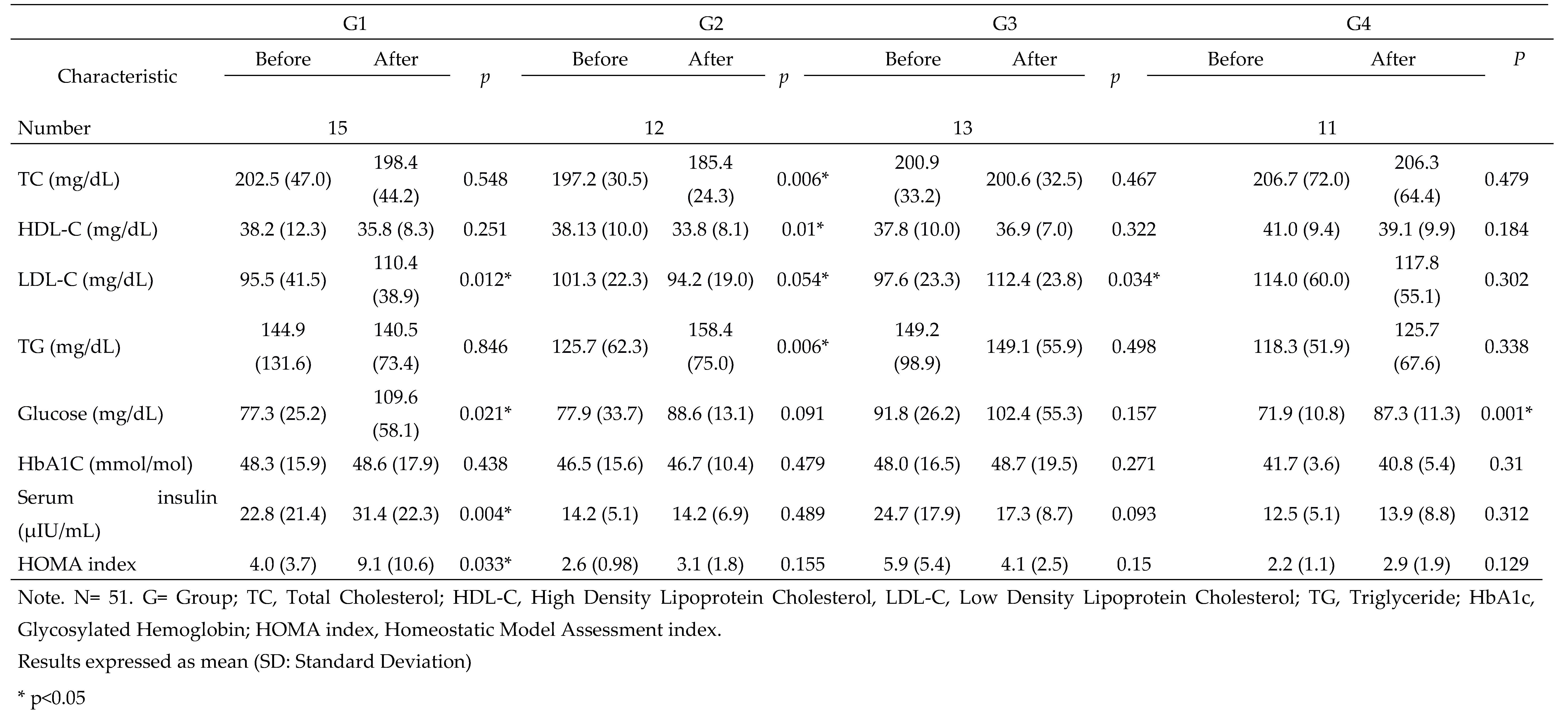

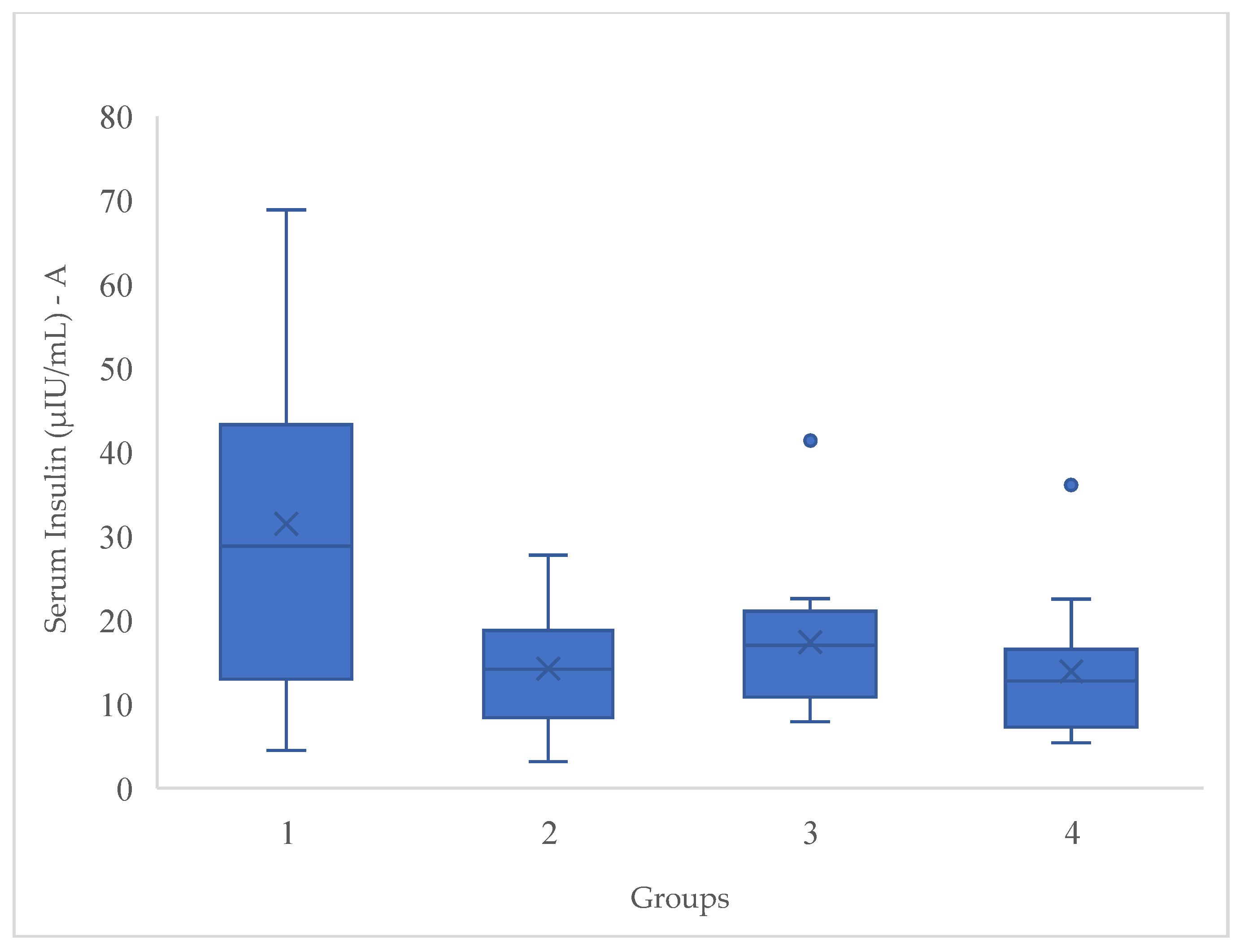

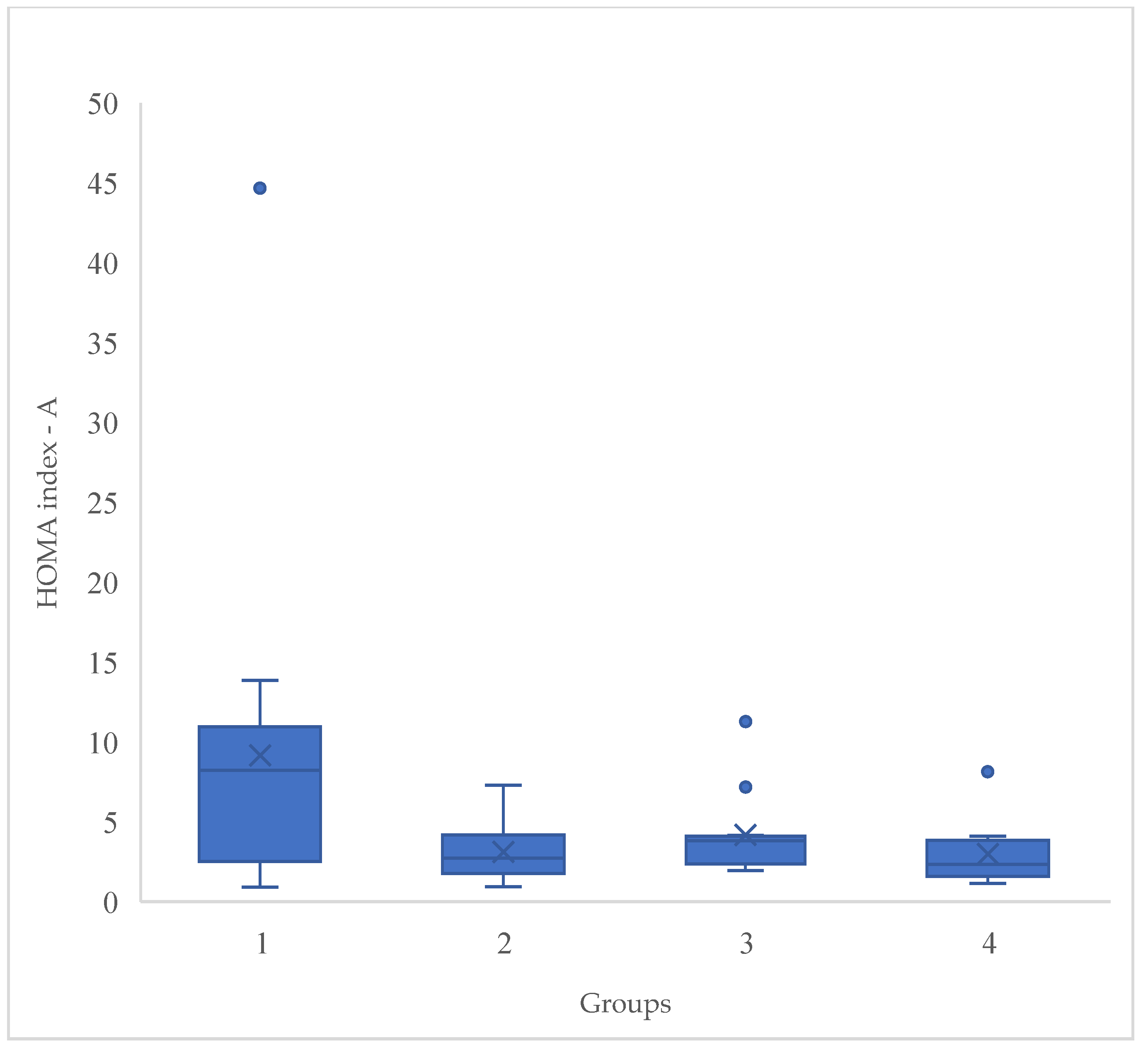

Introduction: Non committable chronic diseases such as overweight and obesity are considered in high risk for type 2 diabetes. Around the world, there are 536.6 million people with diabetes. Mexico represents a high prevalence of these diseases. Objective: Evaluate the effect of a synbiotic beverage and a 12-week dietary intervention on body composition and biochemical parameters in women with T2D, overweight or obesity, to obtain an additional strategy as treatment. Methods: A double-blinded, randomized and experimental in a 12 week dietary intervention with a synbiotic fermented beverage with a n=51 women divided in 4 groups: G1 followed a moderate calorie-restricted diet, G2 did the same moderate calorie-restricted diet and a synbiotic, G3 took only the synbiotic and G4 consumed a placebo beverage. Results: The total mean of ages of the 4 groups was 42.90 ± 10.6. The significant changes were in BMI (P<0.001), fat mass (P<0.001), HOMA-index (P<0.001) and serum insulin serum (P<0.001), after the 12 week dietary intervention, proving the effect of the synbiotic. Conclusion: Significant decreases in different body composition and biochemical profiles were proved showing the benefits of the beverage. Further research is needed in gut microbiota profile in this kind of participants.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

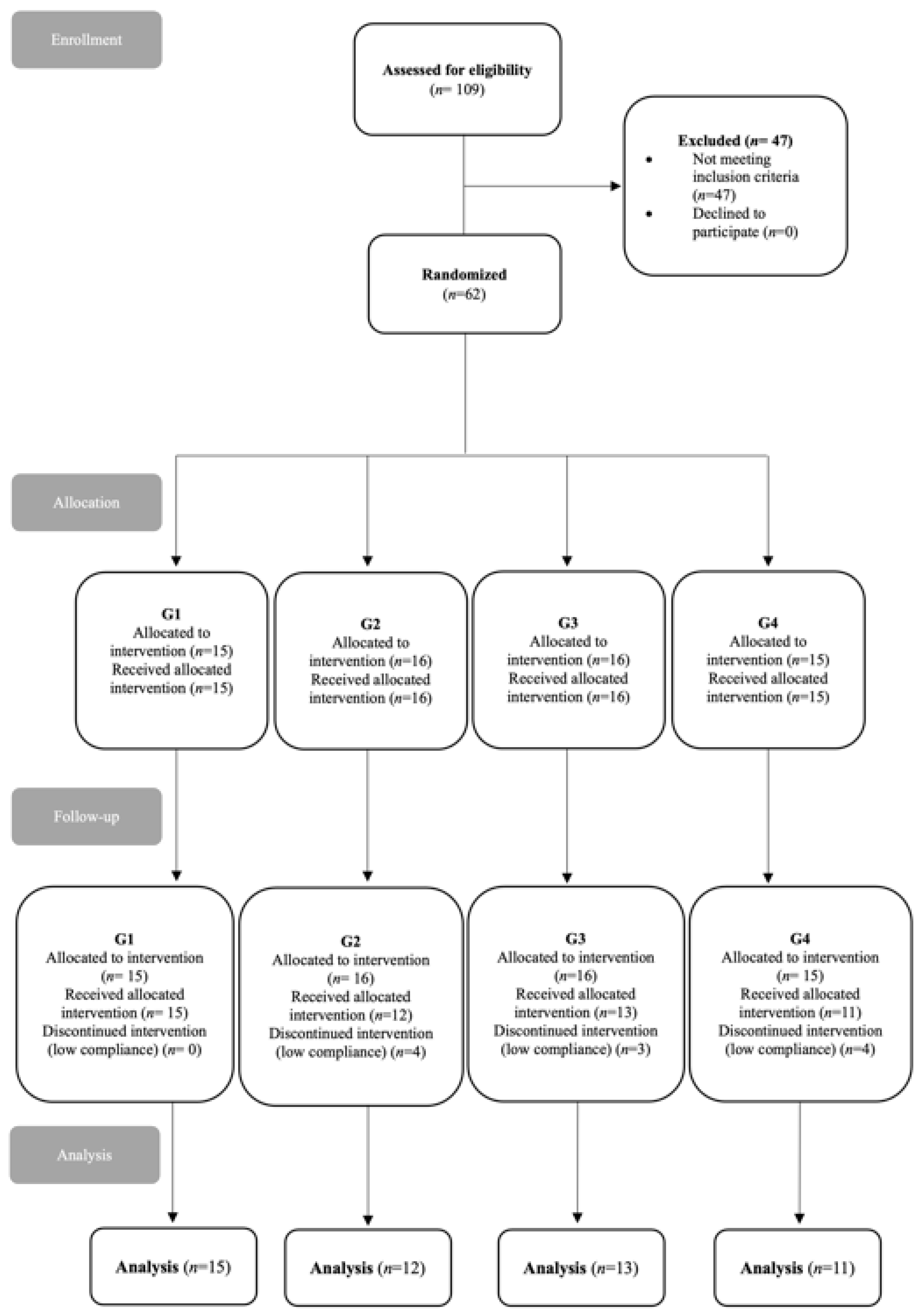

| Weight -B | Wc -B | Hc -B | WH-ratio -B | BMI-B | FTM (%) -B | FM (kg) -B | TC -B | HDL-C -B | LDL-C -B | Glucose -B | TG -B | HbA1C -B | SI -B | HOMA-I -B | ||

| Weight -A | r2 | 0.971** | 0.733** | 0.853** | -0.096 | 0.834** | 0.705** | 0.913** | 0.04 | -0.072 | 0.154 | -.319* | -0.126 | -0.268 | 0.169 | 0.045 |

| p | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 0.504 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 0.778 | 0.616 | 0.282 | 0.023 | 0.379 | 0.057 | 0.237 | 0.754 | |

| Wc -A | r2 | 0.688** | 0.861** | 0.632** | 0.347* | 0.730** | 0.639** | 0.708** | 0.099 | -0.049 | 0.153 | -0.145 | -0.006 | -0.057 | 0.071 | 0.04 |

| p | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 0.013 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 0.488 | 0.731 | 0.283 | 0.31 | 0.965 | 0.693 | 0.622 | 0.78 | |

| Hc -A | r2 | 0.798** | 0.641** | 0.852** | -0.212 | 0.822** | 0.704** | 0.801** | -0.032 | 0.015 | 0.005 | -.343* | -0.066 | -.319* | 0.192 | 0.089 |

| p | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 0.135 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 0.823 | 0.919 | 0.973 | 0.014 | 0.645 | 0.023 | 0.176 | 0.535 | |

| WH-ratio -A | r2 | -0.107 | 0.324* | -0.24 | 0.727** | -0.072 | -0.04 | -0.079 | 0.181 | -0.093 | 0.198 | 0.278* | 0.093 | 0.366** | -0.152 | -0.056 |

| p | 0.456 | 0.02 | 0.089 | <.001 | 0.617 | 0.781 | 0.582 | 0.204 | 0.514 | 0.164 | 0.049 | 0.514 | 0.008 | 0.286 | 0.694 | |

| BMI-A | r2 | 0.787** | 0.718** | 0.808** | -0.051 | 0.958** | 0.668** | 0.785** | -0.031 | -0.089 | 0.026 | -0.216 | -0.015 | -.297* | 0.078 | 0.022 |

| p | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 0.724 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 0.827 | 0.536 | 0.858 | 0.127 | 0.917 | 0.034 | 0.584 | 0.879 | |

| FTM (%) -A | r2 | 0.703** | 0.623** | 0.729** | -0.073 | 0.698** | 0.850** | 0.806** | 0.116 | 0.089 | 0.167 | -0.196 | -0.057 | -0.183 | 0.209 | 0.179 |

| p | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 0.611 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 0.419 | 0.534 | 0.242 | 0.169 | 0.691 | 0.2 | 0.141 | 0.208 | |

| FM (kg) -A | r2 | 0.881** | 0.749** | 0.839** | -0.053 | 0.848** | 0.771** | 0.892** | -0.015 | -0.027 | 0.051 | -0.229 | -0.035 | -0.188 | 0.209 | 0.122 |

| p | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 0.714 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 0.918 | 0.85 | 0.723 | 0.107 | 0.805 | 0.186 | 0.141 | 0.392 | |

| TC -A | r2 | -0.034 | -0.074 | -0.025 | -0.043 | -0.088 | -0.029 | -0.032 | 0.900** | 0.227 | 0.754** | 0.006 | 0.143 | 0.06 | 0.012 | 0.022 |

| p | 0.815 | 0.605 | 0.861 | 0.763 | 0.539 | 0.842 | 0.822 | <.001 | 0.109 | <.001 | 0.965 | 0.318 | 0.674 | 0.932 | 0.879 | |

| HDL-C -A | r2 | -0.026 | -0.084 | 0.03 | -0.147 | 0.004 | -0.014 | -0.008 | 0.216 | 0.776** | 0.197 | 0.012 | -0.259 | 0.02 | -0.004 | 0.036 |

| p | 0.857 | 0.559 | 0.834 | 0.303 | 0.975 | 0.922 | 0.956 | 0.127 | <.001 | 0.165 | 0.935 | 0.066 | 0.891 | 0.979 | 0.801 | |

| LDL-C -A | r2 | 0.059 | -0.032 | 0.053 | -0.079 | -0.032 | 0.015 | 0.043 | 0.841** | 0.209 | 0.818** | -0.079 | -0.07 | -0.006 | 0.022 | 0.015 |

| p | 0.68 | 0.823 | 0.71 | 0.579 | 0.823 | 0.918 | 0.764 | <.001 | 0.142 | <.001 | 0.579 | 0.626 | 0.968 | 0.878 | 0.914 | |

| TG -A | r2 | -0.146 | 0.084 | -0.126 | 0.272 | -0.011 | -0.076 | -0.129 | 0.202 | -.308* | -0.104 | 0.244 | 0.679** | 0.176 | -0.066 | -0.041 |

| p | 0.308 | 0.56 | 0.377 | 0.054 | 0.938 | 0.596 | 0.367 | 0.156 | 0.028 | 0.466 | 0.085 | <.001 | 0.216 | 0.645 | 0.774 | |

| Glucose -A | r2 | -0.117 | 0.089 | -0.148 | 0.306* | -0.211 | -0.112 | -0.115 | -0.016 | -0.043 | -0.053 | 0.465** | 0.005 | 0.835** | 0.109 | 0.119 |

| p | 0.413 | 0.535 | 0.299 | 0.029 | 0.138 | 0.432 | 0.422 | 0.909 | 0.762 | 0.712 | <.001 | 0.974 | <.001 | 0.448 | 0.404 | |

| HbA1C -A | r2 | -0.136 | 0.095 | -0.144 | 0.305* | -0.187 | -0.055 | -0.097 | -0.036 | -0.009 | -0.035 | 0.540** | -0.074 | 0.870** | 0.094 | 0.125 |

| p | 0.34 | 0.506 | 0.313 | 0.03 | 0.189 | 0.702 | 0.497 | 0.802 | 0.947 | 0.808 | <.001 | 0.604 | <.001 | 0.512 | 0.381 | |

| SI -A | r2 | 0.409** | 0.234 | 0.337* | -0.114 | 0.271 | 0.215 | 0.333* | -0.009 | 0.016 | -0.09 | -0.227 | 0.037 | 0.003 | 0.639** | 0.383** |

| p | 0.003 | 0.098 | 0.016 | 0.428 | 0.054 | 0.129 | 0.017 | 0.952 | 0.909 | 0.53 | 0.11 | 0.799 | 0.985 | <.001 | 0.006 | |

| HOMA-I -A | r2 | 0.283* | 0.252 | 0.226 | 0.046 | 0.102 | 0.174 | 0.243 | -0.001 | -0.046 | -0.068 | -0.121 | -0.006 | 0.350* | 0.478** | 0.246 |

| p | 0.044 | 0.075 | 0.112 | 0.749 | 0.475 | 0.223 | 0.085 | 0.993 | 0.747 | 0.636 | 0.396 | 0.965 | 0.012 | <.001 | 0.082 | |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Statement of Ethics

Consent to participate statement

Conflict of Interest Statement

Funding Sources

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgement

References

- Nianogo RA, Arah OA. Forecasting Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Incidence and Burden: The ViLA-Obesity Simulation Model. Front Public Health. 2022;10:818816.

- Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2022;183.

- Shamah-Levy T R-MM, Barrientos-Gutiérrez T, Cuevas-Nasu L, Bautista-Arredondo S, Colchero MA, Gaona-Pineda EB, Lazcano-Ponce E, Martínez-Barnetche J, Alpuche-Arana C, Rivera-Dommarco J.. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2021 sobre Covid-19. Resultados nacionales. 2021.

- Sáez-Lara MJ, Robles-Sanchez C, Ruiz-Ojeda FJ, Plaza-Diaz J, Gil A. Effects of Probiotics and Synbiotics on Obesity, Insulin Resistance Syndrome, Type 2 Diabetes and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Review of Human Clinical Trials. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(6).

- Cuamatzin-García L, Rodríguez-Rugarcía P, El-Kassis EG, Galicia G, Meza-Jiménez MdL, Baños-Lara MdR, et al. Traditional Fermented Foods and Beverages from around the World and Their Health Benefits. Microorganisms. 2022;10(6):1151.

- Probiotics in food : health and nutritional properties and guidelines for evaluation : Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on Evaluation of Health and Nutritional Properties of Probiotics in Food including Powder Milk with Live Lactic Acid Bacteria, Cordoba, Argentina, 1-4 October 2001 [and] Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Working Group on Drafting Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food, London, Ontario, Canada, 30 April -1 May 2002. Food, Agriculture Organization of the United N, World Health O, Joint FAOWHOECoEoH, Nutritional Properties of Probiotics in Food including Powder Milk with Live Lactic Acid B, Joint FAOWHOWGoDGftEoPiF, editors. Rome [Italy]: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, World Health Organization; 2006.

- Marquez Morales L, El Kassis E, Cavazos-Arroyo J, Rocha Rocha V, Martínez-Gutiérrez F, Pérez-Armendáriz B. Effect of the Intake of a Traditional Mexican Beverage Fermented with Lactic Acid Bacteria on Academic Stress in Medical Students. Nutrients. 2021;13.

- Devotee D, Contreras-Esquivel J. Aguamiel and its fermentation: Science beyond tradition. Mexican Journal of Biotechnology. 2018;3:1-22.

- Díez-Sainz E, Milagro FI, Riezu-Boj JI, Lorente-Cebrián S. Effects of gut microbiota-derived extracellular vesicles on obesity and diabetes and their potential modulation through diet. J Physiol Biochem. 2022;78(2):485-99.

- Negrete-Romero B, Valencia-Olivares C, Baños-Dossetti GA, Pérez-Armendáriz B, Cardoso-Ugarte GA. Nutritional Contributions and Health Associations of Traditional Fermented Foods. Fermentation. 2021;7(4):289.

- Li HY, Zhou DD, Gan RY, Huang SY, Zhao CN, Shang A, et al. Effects and Mechanisms of Probiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics, and Postbiotics on Metabolic Diseases Targeting Gut Microbiota: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2021;13(9).

- Salazar J, Angarita L, Morillo V, Navarro C, Martínez MS, Chacín M, et al. Microbiota and Diabetes Mellitus: Role of Lipid Mediators. Nutrients. 2020;12(10).

- Ortega MA, Fraile-Martínez O, Naya I, García-Honduvilla N, Álvarez-Mon M, Buján J, et al. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Associated with Obesity (Diabesity). The Central Role of Gut Microbiota and Its Translational Applications. Nutrients. 2020;12(9).

- Boscaini S, Leigh SJ, Lavelle A, García-Cabrerizo R, Lipuma T, Clarke G, et al. Microbiota and body weight control: Weight watchers within? Mol Metab. 2022;57:101427.

- Wang D, Liu J, Zhou L, Zhang Q, Li M, Xiao X. Effects of Oral Glucose-Lowering Agents on Gut Microbiota and Microbial Metabolites. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:905171.

- Zhou Z, Sun B, Yu D, Zhu C. Gut Microbiota: An Important Player in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:834485.

- Craciun CI, Neag MA, Catinean A, Mitre AO, Rusu A, Bala C, et al. The Relationships between Gut Microbiota and Diabetes Mellitus, and Treatments for Diabetes Mellitus. Biomedicines. 2022;10(2).

- Wu D, Wang H, Xie L, Hu F. Cross-Talk Between Gut Microbiota and Adipose Tissues in Obesity and Related Metabolic Diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:908868.

- Saleem A, Ikram A, Dikareva E, Lahtinen E, Matharu D, Pajari AM, et al. Unique Pakistani gut microbiota highlights population-specific microbiota signatures of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Gut Microbes. 2022;14(1):2142009.

- Liu W, Luo Z, Zhou J, Sun B. Gut Microbiota and Antidiabetic Drugs: Perspectives of Personalized Treatment in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:853771.

- Huda MN, Kim M, Bennett BJ. Modulating the Microbiota as a Therapeutic Intervention for Type 2 Diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:632335.

- Lazar V, Ditu L-M, Pircalabioru GG, Picu A, Petcu L, Cucu N, et al. Gut Microbiota, Host Organism, and Diet Trialogue in Diabetes and Obesity. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2019;6.

- New Insights on Obesity and Diabetes from Gut Microbiome Alterations in Egyptian Adults. OMICS: A Journal of Integrative Biology. 2019;23(10):477-85.

- Li WZ, Stirling K, Yang JJ, Zhang L. Gut microbiota and diabetes: From correlation to causality and mechanism. World J Diabetes. 2020;11(7):293-308.

- Pai C-S, Wang C-Y, Hung W-W, Hung W-C, Tsai H-J, Chang C-C, et al. Interrelationship of Gut Microbiota, Obesity, Body Composition and Insulin Resistance in Asians with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2022;12(4):617.

- Megur A, Daliri EB-M, Baltriukienė D, Burokas A. Prebiotics as a Tool for the Prevention and Treatment of Obesity and Diabetes: Classification and Ability to Modulate the Gut Microbiota. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022;23(11):6097.

- Włodarczyk M, Śliżewska K. Obesity as the 21st Century's major disease: The role of probiotics and prebiotics in prevention and treatment. Food Bioscience. 2021;42:101115.

- Gomes AC, de Sousa RG, Botelho PB, Gomes TL, Prada PO, Mota JF. The additional effects of a probiotic mix on abdominal adiposity and antioxidant Status: A double-blind, randomized trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25(1):30-8.

- Kim J, Yun JM, Kim MK, Kwon O, Cho B. Lactobacillus gasseri BNR17 Supplementation Reduces the Visceral Fat Accumulation and Waist Circumference in Obese Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J Med Food. 2018;21(5):454-61.

- Thiennimitr P, Yasom S, Tunapong W, Chunchai T, Wanchai K, Pongchaidecha A, et al. Lactobacillus paracasei HII01, xylooligosaccharides, and synbiotics reduce gut disturbance in obese rats. Nutrition. 2018;54:40-7.

- Farhangi MA, Javid AZ, Dehghan P. The effect of enriched chicory inulin on liver enzymes, calcium homeostasis and hematological parameters in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Primary Care Diabetes. 2016;10(4):265-71.

- Razmpoosh E, Javadi A, Ejtahed HS, Mirmiran P, Javadi M, Yousefinejad A. The effect of probiotic supplementation on glycemic control and lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized placebo controlled trial. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews. 2019;13(1):175-82.

- Kobyliak N, Falalyeyeva T, Mykhalchyshyn G, Kyriienko D, Komissarenko I. Effect of alive probiotic on insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes patients: Randomized clinical trial. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews. 2018;12(5):617-24.

- Ebrahimi Zs, Nasli-Esfahani E, Nadjarzade A, Mozaffari-khosravi H. Effect of symbiotic supplementation on glycemic control, lipid profiles and microalbuminuria in patients with non-obese type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, clinical trial. Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders. 2017;16(1):23.

- Mahboobi S, Rahimi F, Jafarnejad S. Effects of Prebiotic and Synbiotic Supplementation on Glycaemia and Lipid Profile in Type 2 Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Adv Pharm Bull. 2018;8(4):565-74.

- Salud, Sd. Ley General de Salud. Artículo 54. “Reglamento Interno de Investigación en Salud”. Consultado en: https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/regley/Reg_LGS_MIS.pdf. 2014.

- Cuamatzin-García L, Rodríguez-Rugarcía P, El-Kassis EG, Galicia G, Meza-Jiménez ML, Baños-Lara MDR, et al. Traditional Fermented Foods and Beverages from around the World and Their Health Benefits. Microorganisms. 2022;10(6).

- Dimidi E, Cox SR, Rossi M, Whelan K. Fermented Foods: Definitions and Characteristics, Impact on the Gut Microbiota and Effects on Gastrointestinal Health and Disease. Nutrients. 2019;11(8).

- Zeinali F, Aghaei Zarch SM, Vahidi Mehrjardi MY, Kalantar SM, Jahan-Mihan A, Karimi-Nazari E, et al. Effects of synbiotic supplementation on gut microbiome, serum level of TNF-α, and expression of microRNA-126 and microRNA-146a in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: study protocol for a double-blind controlled randomized clinical trial. Trials. 2020;21(1):324.

- Karimi E, Heshmati J, Shirzad N, Vesali S, Hosseinzadeh-Attar MJ, Moini A, et al. The effect of synbiotics supplementation on anthropometric indicators and lipid profiles in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Lipids Health Dis. 2020;19(1):60.

- Rasaei N, Heidari M, Esmaeili F, Khosravi S, Baeeri M, Tabatabaei-Malazy O, et al. The effects of prebiotic, probiotic or synbiotic supplementation on overweight/obesity indicators: an umbrella review of the trials' meta-analyses. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;15:1277921.

- Álvarez-Arraño V, Martín-Peláez S. Effects of Probiotics and Synbiotics on Weight Loss in Subjects with Overweight or Obesity: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2021;13(10).

- Chaiyasut C, Sivamaruthi BS, Kesika P, Khongtan S, Khampithum N, Thangaleela S, et al. Synbiotic Supplementation Improves Obesity Index and Metabolic Biomarkers in Thai Obese Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Foods. 2021;10(7):1580.

- Rahimi F, Pasdar Y, Kaviani M, Abbasi S, Fry H, Hekmatdoost A, et al. Efficacy of the Synbiotic Supplementation on the Metabolic Factors in Patients with Metabolic Syndrome: A Randomized, Triple-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Int J Clin Pract. 2022;2022:2967977.

- Rabiei S, Hedayati M, Rashidkhani B, Saadat N, Shakerhossini R. The Effects of Synbiotic Supplementation on Body Mass Index, Metabolic and Inflammatory Biomarkers, and Appetite in Patients with Metabolic Syndrome: A Triple-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. J Diet Suppl. 2019;16(3):294-306.

- Batu Z, Gök Balcı U, Akal Yıldız E. The Effect of Using Synbiotic on Weight Loss, Body Fat Percentage and Anthropometric Measures in Obese Women. Progress in Nutrition. 2021;23(2):e2021116.

- Darvishi S, Rafraf M, Asghari-Jafarabadi M, Farzadi L. Synbiotic Supplementation Improves Metabolic Factors and Obesity Values in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Independent of Affecting Apelin Levels: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo - Controlled Clinical Trial. Int J Fertil Steril. 2021;15(1):51-9.

- Ben Othman R, Ben Amor N, Mahjoub F, Berriche O, El Ghali C, Gamoudi A, et al. A clinical trial about effects of prebiotic and probiotic supplementation on weight loss, psychological profile and metabolic parameters in obese subjects. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2023;6(2):e402.

- Sergeev IN, Aljutaily T, Walton G, Huarte E. Effects of Synbiotic Supplement on Human Gut Microbiota, Body Composition and Weight Loss in Obesity. Nutrients. 2020;12(1).

- Jamshidi S, Masoumi SJ, Abiri B, Vafa M. The effects of synbiotic and/or vitamin D supplementation on gut-muscle axis in overweight and obese women: a study protocol for a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Trials. 2022;23(1):631.

- Greany KA, Bonorden MJ, Hamilton-Reeves JM, McMullen MH, Wangen KE, Phipps WR, et al. Probiotic capsules do not lower plasma lipids in young women and men. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62(2):232-7.

- Sun L, Xie C, Wang G, Wu Y, Wu Q, Wang X, et al. Gut microbiota and intestinal FXR mediate the clinical benefits of metformin. Nature Medicine. 2018;24(12):1919-29.

- Tenorio-Jiménez C, Martínez-Ramírez MJ, Gil Á, Gómez-Llorente C. Effects of Probiotics on Metabolic Syndrome: A Systematic Review of Randomized Clinical Trials. Nutrients. 2020;12(1):124.

- Megur A, Daliri EB, Baltriukienė D, Burokas A. Prebiotics as a Tool for the Prevention and Treatment of Obesity and Diabetes: Classification and Ability to Modulate the Gut Microbiota. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(11).

- Ooi LG, Liong MT. Cholesterol-lowering effects of probiotics and prebiotics: a review of in vivo and in vitro findings. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;11(6):2499-522.

- Ojeda-Linares C, Álvarez-Ríos GD, Figueredo-Urbina CJ, Islas LA, Lappe-Oliveras P, Nabhan GP, et al. Traditional Fermented Beverages of Mexico: A Biocultural Unseen Foodscape. Foods. 2021;10(10).

- Márquez-Morales L, El-Kassis EG, Cavazos-Arroyo J, Rocha-Rocha V, Martínez-Gutiérrez F, Pérez-Armendáriz B. Effect of the Intake of a Traditional Mexican Beverage Fermented with Lactic Acid Bacteria on Academic Stress in Medical Students. Nutrients. 2021;13(5).

- Garcia-Arce ZP, Castro-Muñoz R. Exploring the potentialities of the Mexican fermented beverage: Pulque. Journal of Ethnic Foods. 2021;8(1):35.

- Romero-Luna HE, Hernández-Sánchez H, Dávila-Ortiz G. Traditional fermented beverages from Mexico as a potential probiotic source. Annals of Microbiology. 2017;67(9):577-86.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).