1. Introduction

Public procurement is an important part of public expenditure, accounting for between 12 and 15 % of GDP [

1]. In Slovenia, in 2022, the share of total public procurement amounted to 14.11 per cent of GDP [

2]. With over EUR 8 billion of public procurement contracts awarded in that year, public procurement is an important part of the public finance system.

The European Court of Auditors (hereinafter ECA) [

3] carried out an audit of the European public procurement system at the end of 2023 and produced a special report entitled Public Procurement in the EU, which found that the level of competition in public procurement in the EU single market has declined over the last ten years. ECA in its report has made a recommendations to improve public procurement system and first (to European Commission as care takers of procurement system of European Union) is to clarify and prioritise public procurement objectives. The challenges of competitiveness of European Union's internal market and public procurement has also gained the attention of European Council which has administered former Italian Prime Minister Enrico Letta to prepare a special report on the necessary strategy for the modernisation of the internal market. Among other things, he points to the need, due to the increased complexity and number of rules at EU level, for an efficient and effective implementation of these rules and, inter alia, for the simplification of the rules [

4].

The public sector tends to meet the needs of the public interest and in this respect is significantly different from the private sector. This characteristic forms the basis for the functioning of public markets, where the public interest is replaced by profit maximisation [

5]. As an important element of the public interest and one of the fundamental principles of public procurement, value for money, is itself an element of public expenditure, which is used to realise the interest of the contracting authority in maximising the benefits of the purchases, and is reflected in the maxima more value for money. Value for money is the key to the optimal allocation of public goods and one the main goal of public procurement [

6].

In accordance with Treaty of functioning of the European Union (TFEU) , article 4, the Union share competence with the Member States in the area of internal market, including public procurement. Legislative environment of public procurement in EU is mainly defined by two directives, Directive 2014/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on public procurement and repealing Directive 2004/18/EC and Directive 2014/25/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on procurement by entities operating in the water, energy, transport and postal services sectors and repealing Directive 2004/17/EC . In recent years, however, we have seen an increasing number of EU regulations in public procurement rules that have a direct and immediate impact on national legislation.

By proposing a new procurement directive in 2011, the European Commission sought to achieve two main goals: to enable procurers to better use public procurement to support common societal goals, and to increase the efficiency of public spending to ensure the best possible procurement outcomes in terms of value for money [

7]. At the same time, the European Parliament [

8] adopted a resolution on the modernisation of public procurement in the EU in 2011, in which it advocates six tasks, half of which focus on increasing the efficiency of public procurement markets. Also, the European Commission [

9] has issued a communication on the future challenges of public procurement in Europe, where the need to ensure a wider uptake of strategic procurement is recognised as one of the six strategic priorities, which could lead to significant benefits in procurement outcomes.

From the study of exchange mechanism of public procurement, it is important that public procurement procedures and techniques can be classified among the known different types of auctions, as well as the exchange mechanism of negotiation. Therefore, auction theory is an appropriate starting point to address aspects of the efficiency of the public procurement system as a function of the value for money of public money. When we discuss about auctions in public procurement, which is predominantly exchange mechanism in modern procurement [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14] usually conducted in a manner, for example in the English auction type, where the price (bid) is increased in the procedure up to the point where everyone abandons the auction and only one bidder remains. In public procurement, the process is reversed, as it is a buying process and not a selling process, hence we speak of reverse auctions. However, formally, the process is the same.

The important statement of auction theory is the economic analysis of different auctions and commonly addressed question whether those auctions are equivalent in terms of expected prices. Auction theory explains that auctions are to be revenue equivalent as they result in same expected prices. As Klemperer has explained it [

11] (similarly [

15]), simultaneously have [

16] and [

17] showed that Vickrey’s results about the equivalence in expected revenue of different auctions apply very generally.

We can see that all standard (and less standard) types of auction exchange mechanisms are equally profitable for the seller and that, at the same time, buyers are indifferent to the choice of different types [

18], except negotiations where, as we have seen, research is ambivalent about the efficiency outcomes (eg. [

19] and [

20]). This suggests that the contracting authority, as a buyer, should not be concerned about the choice of procedure in terms of cost-effectiveness, nor should the legislator in setting the different rules for different procedures.

Efficient public procurement can achieve significant monetary savings, where efficient public procurement can be understood as better value for money, and public procurement has, among other things, a built-in system of redress to prevent inappropriate decisions by contracting authorities [

21]. Public procurement reforms that aim to increase economic growth will need to thoroughly understand the complex nature of the public procurement system, as well as simultaneously address a range of challenges in the areas of accountability, transparency, fairness and economic efficiency [

22].

The necessary (high) efficiency of public procurement is one of the important objectives of public procurement [

23], although the ends and means of public procurement (and its legal-economic regulation) may be interchangeable, as there is not always a clear distinction between what can be considered as means and ends, and what the hierarchy between them is [

24]. Different countries within the European Union are trying to find the best balance between the normative regulation of individual procurement procedures and the discretion of contracting authorities. The right balance also means a more efficient public procurement system, as [

21] points out, there are three key elements of an efficient public procurement system, namely transparency, objectivity and non-discrimination. Also, the ECA [

3] in its report has made a recommendations to improve public procurement system and one of important is to clarify and prioritise public procurement objectives.

Both technical and allocative efficiency are important in public procurement. As explained by [

25], controlling technical and allocative efficiency in public procurement is possible in practice in terms of understanding and observing the economics, efficiency and effectiveness.

The public procurement system has been criticised over the years (e.g. [

26]) for overemphasising compliance and cost minimisation to the detriment of public benefit and social welfare objectives. Some 15 years later, it is clear that the primary objective of value for money has somehow given way to strategic secondary policies. Today, the theory understands the components of public benefit from the perspective of the public procurer as the generation of innovation, the good functioning of the supplier market, the efficient (effective) functioning of the public procurement system and sustainable public procurement [

27].

2. Materials and Methods

Policies that focus on the operation or regulation of relationships between procuring entities and other entities outside the direct contract tend to be more burdensome for suppliers and also lead to higher costs [

28]. [

29] explain that the more complex the requirements of the secondary procurement policy, the higher the mark-up in the contract price paid by the procuring entity. Additional requirements (in a specific procurement) that are only indirectly related to the subject matter of the procurement and are defined and required by legislation increase both direct and transaction costs and lead to higher prices [

30,

31].

A number of studies have examined the cost-effectiveness of public procurement, in particular highlighting certain individual factors and certain aspects of the award of contracts, and many studies, as mentioned below, have chosen as a tool of comparison the difference between the estimated value of the contract and the final, selected tender.

Previous studies have examined aspects of procurement efficiency mainly from the perspective of price or cost-effectiveness and studies have used the difference between the estimated value (usually referred to as the reserve price, estimated price or expected price) and the final value of the best bid as a starting point and a model for calculating the efficiency of the different variables, for example in [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. Our study will help policy makers to address challenges of reaching different goals of public procurement, efficiency and competitiveness on one hand and pursing strategic societal goals on the other.

Through understanding the public procurement system, the auction exchange mechanism and the impact of a wide range of factors in parallel with a complex sample of public contracts that have already been carried out, we carried out not only analysis of some procurement procedures, but also different techniques and other strategic and sustainable measures, such as green and socially responsible procurement, usage of electronic procurement tools and additional, non-cost award criteria to observe the impact in our model.

Endogenous factors in the context of the implementation of an efficient public procurement by a contracting authority are understood to be the various secondary policies such as social and green public procurement, which are available or mandatory for contracting authorities, the use of e-procurement and the use of criteria other than price (non-price criteria). However, exogenous factors are understood to be parameters that are independent of the contracting authority itself and can influence efficiency, such as the number of bids and the publication of the contract in the Official Journal of the European Union.

The dependent variable will be using in research is the same as of many authors explained above, is the difference between the estimated value, which is the average of the market prices (the contracting authority must determine the estimated value of each contract and base it on market prices) and the final (winning) price. This can be seen as a better auction performance, i.e. a more efficient use of public money.

The primary sources are based on data from the Public Procurement Portal, owned by the Ministry of Public Administration and managed by Slovene national gazette, Uradni list d.o.o. It covers 120,455 public procurement procedures which represent individual lots awarded by contracting authorities, i.e. state authorities, self-governing local authorities, public institutions and public enterprises, between 2016 and 2023 and processed by the authors. The computations were conducted using the EViews 12 University Edition for Windows software.

For each procurement, we will look at different factors, roughly more than 15 factors, which are our explanatory variables (types of procedures, use of techniques strategic procurement), and dependent variables representing the difference between the estimated value of the public contract and the difference between the estimated market prices, based on a survey carried out by the contracting authority, and the price paid by the most advantageous tenderer. Estimation (estimated price) is made by internal or external procurement experts, especially for large investment projects, which must be included in the investment documents of the project, so they should be considered as an average true representation of market prices. The difference between estimated price and value of bid represents the cost-effectiveness of specific procurement procedure which explains whether the price in a procurement is lower than the contracting authority's estimate (Tas, 2020). The factors observed in our research are (see

Table 1):

Regarding the methodology, from the cost-efficiency point of view, we will look at the issue of technical efficiency of public procurement system, which determines the economy and efficiency of the public procurement system with different variables, similar to some research (e.g. [

25]). This usage also reflects the notion of value for money in public procurement and is one of the most prominent goals of public procurement system. To achieve this goal, we will set out following two main questions with auxiliary research questions:

- 1.

What is the technical efficiency of public procurement system when using different procedures, techniques and other instruments?

- a.

What is the cost efficiency of using the transparent procedures and other, less transparent procedures?

- b.

What is the cost efficiency of using different public procurement techniques?

- c.

What is the cost efficiency of reaching sustainable and societal goals of procurement?

Observed variable is reduction, which is calculate using the following formula:

To test our research questions, we will employ binary response regression model. Binary dependent variable models as limited dependent variables have been used in several public procurement papers, for example [

38] on the use of competitive dialogue, [

39] on bidder prediction, [

40] on start-ups in public procurement. There are also several papers on strategic public procurement, such as [

41] on barriers to innovation in public procurement, [

42] on green award criteria in procurement, [

43] on green procurement and innovation, [

44] on adoption of green procurement practices, [

45] on financial barriers and green innovation, and [

46] on European funds and green public procurement.

As we have seen, in the past authors have studied public procurement mainly from the perspective of different types of procurement goods [

13], from the perspective of more or less complex projects [19 and 20]). [

47] studied some of the factors influencing the final price in public procurement procedures, most of which are exogenous in nature; similarly, the efficiency of the public procurement system has been studied mainly from a competitive perspective by [

48], [

49] or [

50]. Based on these studies, we cannot clearly conclude whether the public procurement system, from the perspective of the mix of different rules, (procedures and techniques) and strategic policies is an efficient system that can represent a rational use of public funds. Therefore, we will develop a model to compare the different factors of procurement and try to answer our hypothesis.

In our paper, we examine how the independent variables (procedures, techniques and other factors) in our model affect the dependent variable, ‘reduction’, which we will, as explained below, set in binary categories. In binary response models, the dependent variable takes only two values, 0 or 1, as follows:

In our paper, we examine how the independent variables (procedures, techniques and strategic policies) in our model affect the dependent variable, reduction. Several authors, as well as [

25], point out that although it is common to find studies of calculated differences between estimated and final values on certain factors using a linear regression model, it is not always the case that the effect of 'imaginary savings' can be found in the research, as these differences do not necessarily reflect actual market prices. Therefore, in our work we mainly talk about 'reductions' rather than 'savings'.

In the model we will include all the factors that might have an impact on this variable, and we will use the model to test whether all the factors included have a statistically significant impact. Logit model is used to identify the impact of different variables on cost-efficiency.

3. Results

The data for the analysis was extracted from the SQL database of the public procurement portal (enarocanje.si) of the Ministry of Public Administration, which is managed by the public company Uradni list d.o.o. We exclude public procurement contracts where there is an error in the estimated value of the contract or the final value of the tender. We have included 120,455 public procurement contracts for goods, services and works during this period.

To study the impact of explanatory variables on reduction we run a qualitative response regression model. We will employ binary logit regression model, which is used to model binary variables, where regressand is a binary variable [

51], to determine event probabilities of factors where the dependent variable follows Bernoulli distribution. In binary response model, interest lies primarily in the response probability [

52]:

The independent variables that will be included in the model are listed below. We will use different types of procedures, different types of techniques and other factors, such as green and social procurement, involvement of SME’s and usage of e-PP. Based on the literature on the amount of reduction or 'savings' ([

53] 3,4%; [

25] 6%) and our mean of reduction (0.088), we arbitrarily divide procurements where the considerable reduction is at least 5% (value of 1>0.05; 0<0.05). That we consider as cost-efficient public procurement.

All the factors, except for the number of offers, are dummy variables. By testing the different factors on the dependent variable, we will thus be able to determine the direction and magnitude of their effect, first we will test their statistical significance of the model.

First, we will test the factors described above. We find that some factors (as involvement of SME’s, non-domestic bidders, involvement of subcontractors and several procurement procedures, as restricted, negotiations with prior notice and partnership for innovation procedure), are not statistically significant and were not included in computation. We chose values less than p<0.05, which means that we are lowering the chance of a Type I error [

54]. The likehood ratio chi-square of 6888,550, with a p-value of 0,0000 tells us that our model as a such is statistically significant . We run the model and got results, as follows (see

Table 2):

The descriptive statistic of included factors are as listed in table 3:

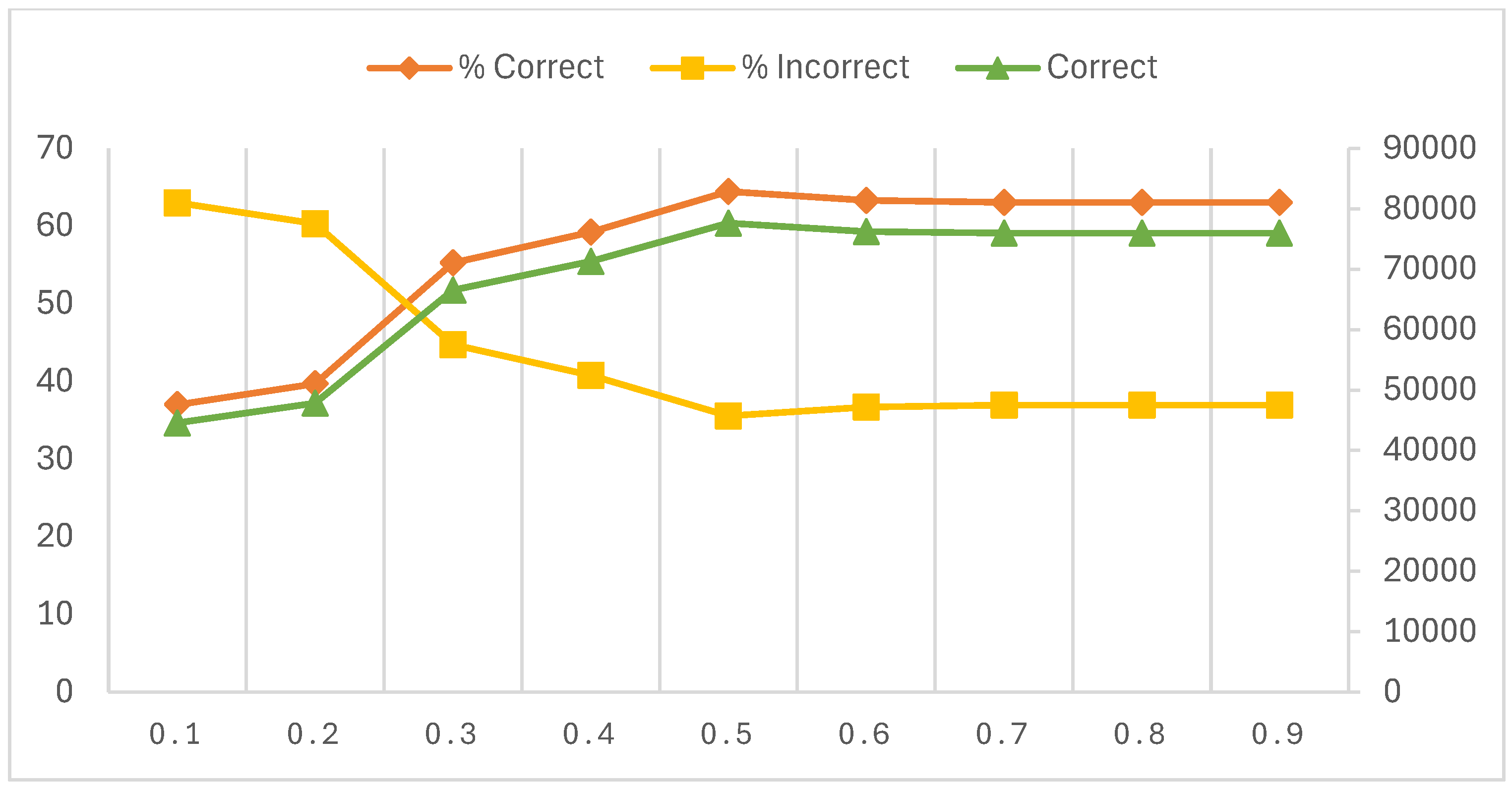

Second, as the computed value of the coefficient of determination and the adjusted coefficient of determination is not a good measure of the model's goodness of fit, as actual values of the dependent variable can only be 0 or 1, so R2 or adjusted R2 is small. So, we will employ goodness of fit of that tells us for how many observation units the model prediction was correct, i.e. we calculate the proportion of correct predictions [

55]. The graph (see

Figure 1) below shows us prediction at different cut off rate.

Optimal cutoff rates, where Dep=0 and Dep=1 are closest, is at 0,4 (see

Table 4).

Expectation-prediction evaluation for our model at cut-off rate 0,4 is correct in 59,21% cases.

Correlation table is as follows (see

Table 5):

Table 5 shows the pair-wise correlations. The correlations show the direction of movement among the variables. The test is important tool to help us understanding the trends and behaviour of the relevant variables of our model. We see that correlation is low among procedures, which are usually exclusive, but inclusive on different techniques. While using open procedure there is high correlation of publication in EU portal notices and likewise negative with NMV (small value domestic procedure).

We perform the computation with relevant factors of our model. The transparent procedures, according to the model, tend to have a higher probability of being used in the procurement with a reduction of 5 percent or more, e.g. if the contracting authority uses the open procedure, ceteribus paribus, there is a 130 percent odds (and probability of 70%) that the reduction in the contract value or savings will be 5 percent or more. Similarly, we can see high probability for small value purchases procedure (NMV) and competitive dialogue, where there is a 93 percent odds (65% probability) of reduction when using this type of procedure, similarly with centralised procurement and electronic auctions. If contracting authority is using an electronic auction, there is a 45 percent odds that savings will occur. We can see that these factors tend to be more efficient than the procedures not involving these factors. Negotiated procedure without publication is reducing the possibility of reduction (above 5%), as do some other factors, such as green procurement, publication in EU, additional criteria, and interestingly, with the involvement of electronic public procurement. Usage of framework agreements reduces the odds of considerable reduction by 46 percent (probability is 30 %).

We can also see that each additional bid increases the odds of significant reduction by 4%, which means that competition, as measured by the number of bids in the procurement procedure, has an effect on reducing contract values.

As noted above, our model shows that at least one of the independent variables involved is correlated with the dependent variable (lowering), with 59,2% correct of estimated equation.

We can say that, on average, the use of transparent procedures, where the contracting authority can have the least influence on the involvement of tenderers, the open procedure, competitive dialogue and the small value purchase, have the highest impact. Among the procedures, reduction is most obvious for open procedure, which is also the most transparent. A similar estimate is given by the small value purchase procedure variable, which, is a fully transparent national procedure, similar to open procedure, but yet more flexible and economic procedure. With techniques we see that probability to reduce is highest with electronic auctions and with centralised procurement, framework agreement are techniques where it’s use worsens the probability. Similar is with electronic procurement and green procurement.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the efficiency of the public procurement system, as limited by the rules of procedure, the use of non-binding techniques (in the sense that the contracting authority can choose to use any or none of the techniques, as opposed to procedures where it always has to use one of them) and other factors that influence the outcome of procedures, with a focus on the cost-effectiveness of procurement.

Firstly, we can see that transparent procedures, such as open procedures and procedures for small value purchases, i.e. the national open procedure, which is similar to the open and, as explained, more economical procedure, give better results in terms of cost-effectiveness. Small value procedures tend to reduce procurement costs by in smaller margin than open procedures. When open procedure is employed, for referent values of other variables, using open procedure raises odds by 130%, therefore probability is 69%, that cost reduction will be significant and at least 5% (as explained by difference in average market prices). Additional bids induce higher cost reduction.

Non-transparent negotiated procedures reduce the possibility of reducing contract values. When a negotiated procedure is used, the odds of savings of more than 5% is reduced by 21% or there is a 44% that saving will occur when using this procedure. On the other hand, the use of competitive dialogue, which includes open notification and negotiation, increases the odds of cost-effective procedures by 93%, pushing probability to 66%.

Using different techniques, which can be combined with different procedures (and, unlike procedures, can be used simultaneously), we see that when contracting authorities use centralised procurement, the likelihood of cost reduction increases. When contracting authorities use electronic auctions, the odds of significant savings is 45% (or 59% probability that this event will occur). On the other hand, when framework agreements are used, our model shows that this technique reduces the likelihood of significant cost reductions. Similarly, when electronic tendering is used, this is reducing the probability of significant cost savings.

Finally, the use of strategic procurement, socially responsible procurement and green public procurement produces opposite results. The use of socially responsible criteria in public procurement increases the odds of more cost-effective procurement by 34% (or 57% probability). For green procurement, the opposite is true, with the use of such criteria reducing the likelihood of cost-effective procurement.

5. Conclusions

The year 2024 was a wake-up call for public procurement in the European Union. At the end of 2023, in December 2023, the ECA published its first in-depth report on the competitiveness of EU public procurement markets [

3] stating that the 2014 reform of EU directives has shown no signs of reversing this trend. Overall, there is a lack of awareness of competition in public procurement. In 2024, Enrico Letta, with the approval of the EU Council, published a report on the EU's single market, arguing for significant reforms to the EU's single market. Similar to the ECA, Letta [

4] proposed reforms in public procurement, focusing in particular on the key objectives of procurement and better regulation.

After reviewing the French and European public procurement system, [

56] made ten suggestions for improving the public procurement system, advocating primary for enhanced transparency, better monitoring, simplification and professionalization. They wrote that recognising that the aim of public procurement, regardless of the values at stake, is primarily to meet an identified need by achieving the best possible performance in terms of cost and service or expected functionalities.

The results of our analysis show the need for a transparent public procurement. While open procedures are among the most efficient, national small value purchases, which are similarly transparent as open procedure but more flexible, with more discretion and economically procedure, but similar results in terms of cost-effectiveness. Furthermore, it was confirmed that less transparent procedures are also less efficient in terms of probability of reducing contract values. It was also determined that the number of tenders received has a direct impact on the probability of achieving a reduction in contract values.

On the other hand, the use of centralised procurement and electronic auctions leads to the best results, while techniques such as framework agreements, which operate in a controllable, semi-closed environment and are more prone to collusion, are less likely to be cost-effective. With regard to other factors, we have observed that their use by the contracting authority (green procurement, electronic procurement) reduces the likelihood of cost-effective procurement outcomes, while the opposite is true for socially responsible procurement. We have seen that strategic procurement can have either negative and positive impact on cost-efficiency, so this policies should not be written off as unsuitable.

It can be said that a combination of transparent procedures and an undisclosed market environment at the time of tendering, as well as less binding secondary objectives of procurement, deliver the best cost-efficiency results where savings are considered to be significant. It is recommended that EU legislation promotes a high level of transparency, provides more flexible rules also for procurement above the threshold and limits the use of framework agreements. Secondary measures may have a higher policy objective of addressing climate change and rapidly emerging environmental challenges, and may have an important impact on a fairer, more inclusive and sustainable society, but their cost-effectiveness may remain a challenge.

The prevailing contention in the realm of public procurement appears to be an inherent dichotomy between the pursuit of efficiency and the pursuit of social and environmental objectives. Restrictive conditions have the potential to impede the competitive landscape and result in the excluding the bidders [

57]. Conversely, the European Court of Auditors [

3] has advocated for the optimisation of public procurement goals where it seems that efficiency and strategic goals of procurement are incompatible. This challenging perspective can be overcome by focusing on strategic policies with more efficient rules and a less complex legal environment (reducing administrative burden) in a transparent and open public procurement system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M. and Ž.J.O.; methodology, T.J. and S.M.; validation, Ž.J.O. and T.J; formal analysis, S.M. and Ž.J.O.; investigation, S.M.; resources, S.M.; data curation, S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.; writing—review and editing, Ž.J.O. and T.J.; visualization, S.M.; supervision, Ž.J.O. and T.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ministry of Public Administration in Slovenia for providing necessary data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- OECD. Government at a Glance 2023; OECD Publishing: Paris, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Public Administration. Statistical report on public procurement of 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.si/assets/ministrstva/MJU/DJN/Statisticna-porocila/Stat_por_JN_2022.docx (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Europan Court of Auditors. Special report 28/2023: Public procurement in the EU – Less competition for contracts awarded for works, goods and services in the 10 years up to 2021. 2023. Available online: https://www.eca.europa.eu/en/publications?ref=sr-2023-28 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Letta, E. Much more than a market, Empowering the Single Market to deliver a sustaianble future and prosperity for all EU citizens. 2024. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/ny3j24sm/much-more-than-a-market-report-by-enrico-letta.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Bovis, C. The Law of EU Public Procurement, 2nd ed.; Oxford, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Trybus, M. Beyond Competition and Value for Money: Corporate Social Responsibility in Public Procurement. Kilaw Juournal, Special Supplement 2020. [Google Scholar]

- De Koninck, C.; Ronse, T.; Timmermans, W. European Public Procurement Law: The Public Sector Procurement Directive 2014/24/EU Explained Through 30 Years of Case Law by the Court of Justice of the European Union. Kluwer Law International, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. Modernisation of public procurement European Parliament resolution of 25 October 2011 on modernisation of public procurement (2011/2048(INI)). 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. communication from the commission to the european parliament, the council, the european economic and social committee and the committee of the regions Making Public Procurement work in and for Europe (COM (207) 572 final). 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McAfee, R.P.; McMillan, J. Auctions and bidding. Journal of economic literature 1987, 25, 699–738. [Google Scholar]

- Klemperer, P. Auctions: theory and practice; Princeton University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bajari, P.; Tadelis, S. Incentives versus transaction costs: A theory of procurement contracts. Rand journal of Economics 2001, 32, 387–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajari, P.; McMillan, R.; Tadelis, S. Auctions Versus Negotiations: Evidence from the Building Construction Industry. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 2009, 25, 372–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decarolis, F. When the highest bidder loses the auction: theory and evidence from public procurement; The University of Chicago, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna, V. Auction theory; Academic press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Myerson, R.B. Optimal auction design. Mathematics of operations research 1981, 6, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, J.G.; Samuelson, W.F. Optimal Auctions. American EconomicReview 1981, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom, P. Putting auction theory to work; Cambridge University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, E.; Staropoli, C.; Yvrande-Billon, A. Auction versus negotiation in public procurement: Looking for empirical evidence. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lalive, R.; Schmutzler, A.; Zulehner, C. Auctions vs negotiations in public procurement: which works better. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stilger, P.S. Formulas for Choosing the Most Economically Advantageous Tender-a Comparative Study. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McCue, C.P.; Prier, E.; in Swanson, D. Five dilemmas in public procurement. Journal of public procurement 2015, 15, 177–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, R.; Liu, J. Price/time/intellectual efficiency of procurement: Uncovering the related factors in Chinese public authorities. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 2020, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrowsmith, S. The purpose of the EU procurement directives: ends, means and the implications for national regulatory space for commercial and horizontal procurement policies. Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies 2012, 14, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemec, J.; Kubák, M.; Donin, G.; in Kotherová, Z. Efficiency of public procurement in the Czech and Slovak health care sectors. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences 2021, 17, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erridge, A. Public procurement, public value and the Northern Ireland unemployment pilot project. Public Administration 2007, 85, 1023–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malacina, I.; Karttunen, E.; Jääskeläinen, A.; Lintukangas, K.; Heikkilä, J.; Kähkönen, A.K. Capturing the value creation in public procurement: A practice-based view. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 2022, 28, 100745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrowsmith, S. Horizontal policies in public procurement: a taxonomy. Journal of public procurement 2010, 10, 149–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.; in Marklund, P.O. Green public procurement and multiple environmental objectives. Economia e Politica Industriale 2018, 45, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halonen, K.M. Is public procurement fit for reaching sustainability goals? A law and economics approach to green public procurement. Maastricht Journal of European and comparative law 2021, 28, 535–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.; Marklund, P.O.; Strömbäck, E.; in Sundström, D. Using public procurement to implement environmental policy: an empirical analysis. Environmental Economics and Policy Studies 2015, 17, 487–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, P.; Vyklický, M.; in Heidu, R. Selected Factors Influencing Public Procurement in the Czech Republic. Theoretical and Practical Aspects of Public Finance 2015, 2015, 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Tas, B.K.O. Procurement efficiency in public procurement auctions: Analysis of different types of products. 2012. Available at SSRN 214 8638. [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, R. Impact of procurement professionalization on the efficiency of public procurement. Operations Excellence: Journal of Applied Industrial Engineering 2019, 11, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemec, J.; Grega, M.; in Orviska, M. Over-bureaucratisation in public procurement: purposes and results. Public Sector Economics 2020, 44, 0–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tas, B.K.O. Effect of public procurement regulation on competition and cost-effectiveness. Journal of Regulatory Economics 2020, 58, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemec, P.; Ďuricová, V.; in Kubak, M. Institutions, corruption and transparency in effective healthcare public procurement: evidence from Central and Eastern Europe. Post-Communist Economies 2023, 35, 619–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccino, G.; Iossa, E.; Raganelli, B.; Vincze, M. Competitive dialogue: an economic and legal assessment. Journal of Public Procurement 2020, 20, 163–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia Rodríguez, S.M.; Acevedo Prins, N.; Rojas López, M.D. Using a Logit Model to Predict Plurality of Bidders in Public Tenders. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, B.; Füner, L.; Prüfer, M. Which Start-Ups Win Public Procurement Tenders? ZEW-Centre for European Economic Research Discussion Paper, (24-072). 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Uyarra, E.; Edler, J.; Garcia-Estevez, J.; Georghiou, L.; Yeow, J. Barriers to innovation through public procurement: A supplier perspective. Technovation 2014, 34, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Morotomi, T.; Yu, H. What influences adoption of green award criteria in a public contract? An empirical analysis of 2018 European public procurement contract award notices. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, B.; Zipperer, V. Does green public procurement trigger environmental innovations? Research Policy 2022, 51, 104516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryngemark, E.; Söderholm, P.; Thörn, M. The adoption of green public procurement practices: Analytical challenges and empirical illustration on Swedish municipalities. Ecological Economics 2023, 204, 107655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, D.; Stephan, A.; Fuhrmeister, S. The impact of public procurement on financial barriers to general and green innovation. Small Business Economics 2024, 62, 939–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, R.; Titl, V.; Schotanus, F. European funds and green public procurement (No. 11263). CESifo Working Paper; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Grega, M.; in Nemec, J. Factors influencing final price of public procurement: evidence from Slovakia. Procedia Economics and Finance 2015, 25, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavurova, B.; Tkáčová, A.; Tuček, D. Determinants of public fund's savings formation via public procurement process; Administratie si Management Public, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gavurova, B.; in Kubák, M. The efficiency evaluation of public procurement of medical equipment. Entrepreneurship and sustainability issues. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jovanović, P.; Radojičić, M.; Molnar, D.; Matas, S. Is There a Trade-off Between Sustainability and Competition Goals in Public Procurement? Evidence from Slovenia, Lex Localis, Journal of Local Self-Governement. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gujarati, D.N. Basic Econometrics, International edition; Mc Graw Hill, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Introductory econometrics: a modern approach (upper level economics titles), Southwestern College Publishing: Nashville, 2020.

- Pavel, J.; Sičakova-Beblava, E. Do e-auctions really improve the efficiency of public procurement? The case of Slovak municipalities. Prague Economic Papers 2013, 1, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesana, B.M. What p-value must be used as the Statistical Significance Threshold? P<0.005, P<0.01, P<0.05 or no value at all? Biomedical Journal of Scientific Technical Research 2018, 6, 5310–5318. [Google Scholar]

- Pfajfar, L. Osnovna ekonometrija; Ekonomska fakulteta, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Saussier, S.; Tirole, J. Strengthening the efficiency of public procurement. Notes du conseil danalyse economique 2015, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Christian & Wixforth, Susanne. Policy Brief: Public procurement based on social and environmental criteria. 10.13140/RG.2.2.29916.50563. 2024. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/386602265_Policy_Brief_Public_procurement_based_on_social_and_environmental_criteria (accessed on 5 February 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).