Submitted:

13 February 2025

Posted:

13 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Survey Method

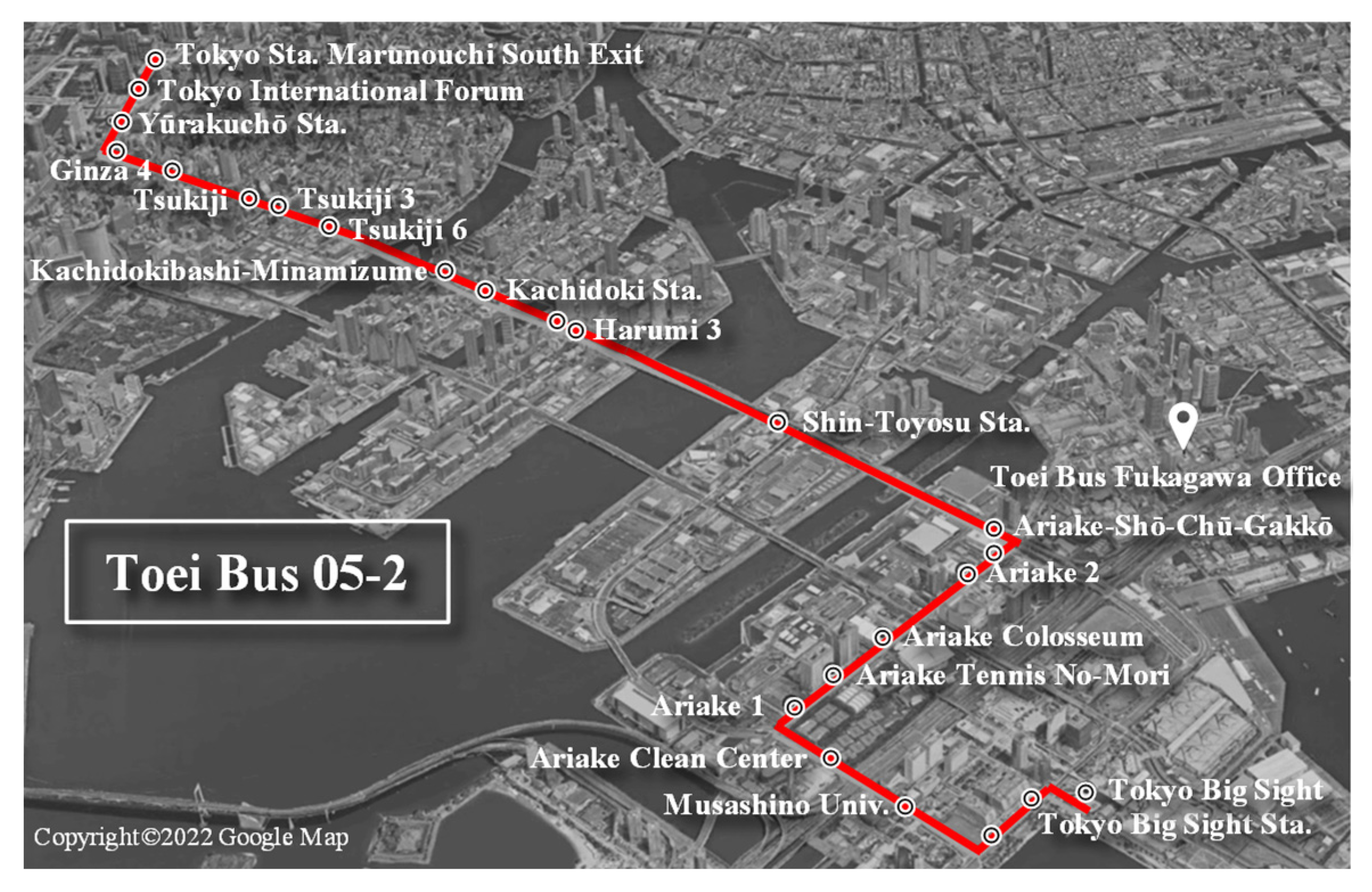

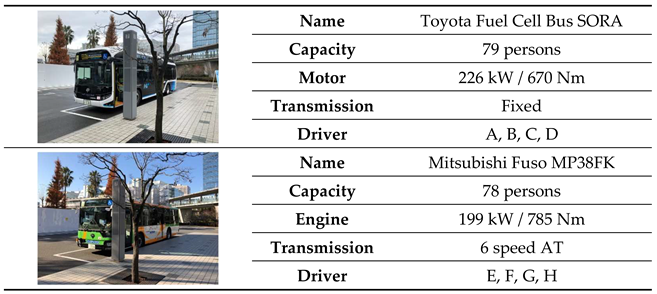

2.1. Regular Routes and Buses Being Measured

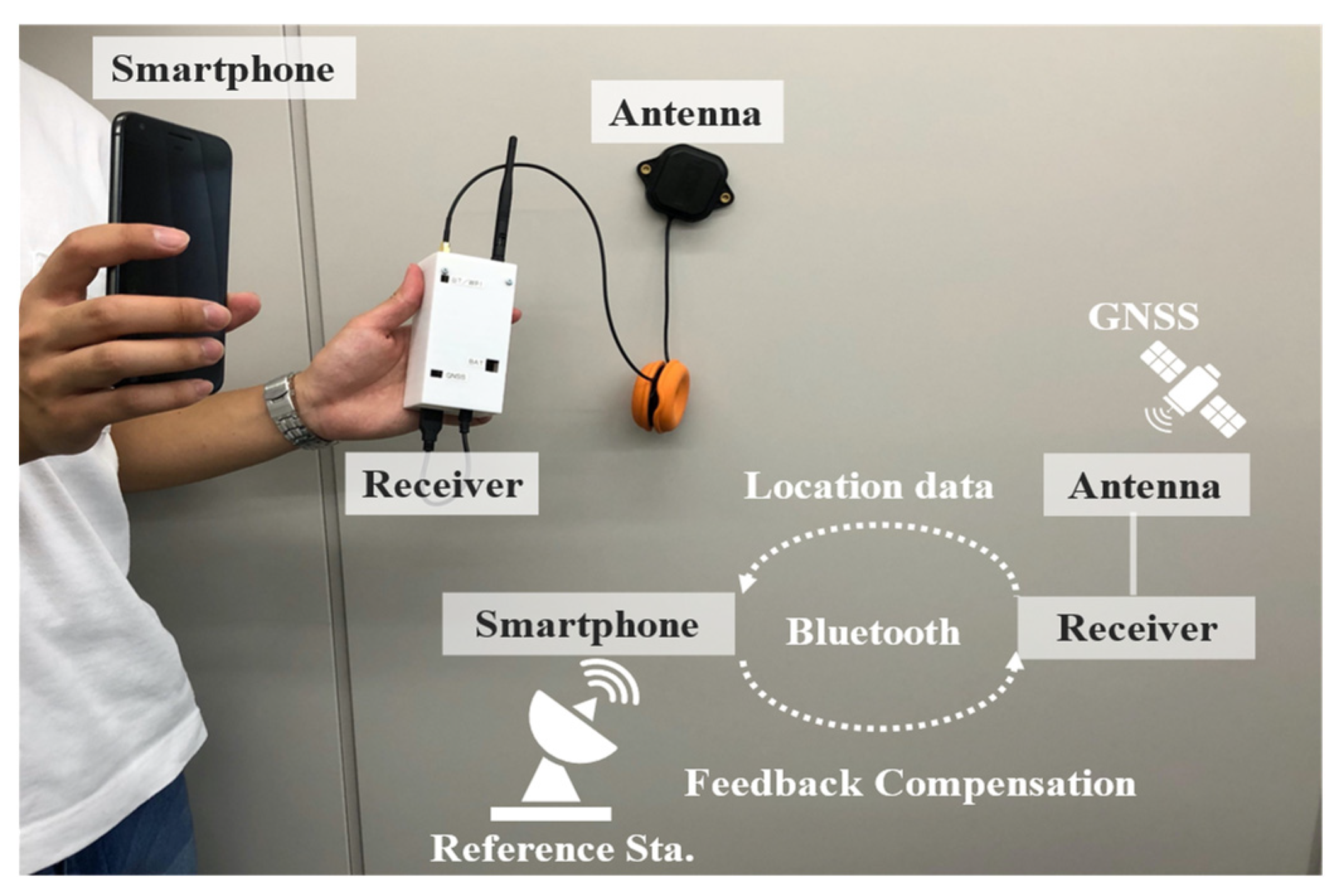

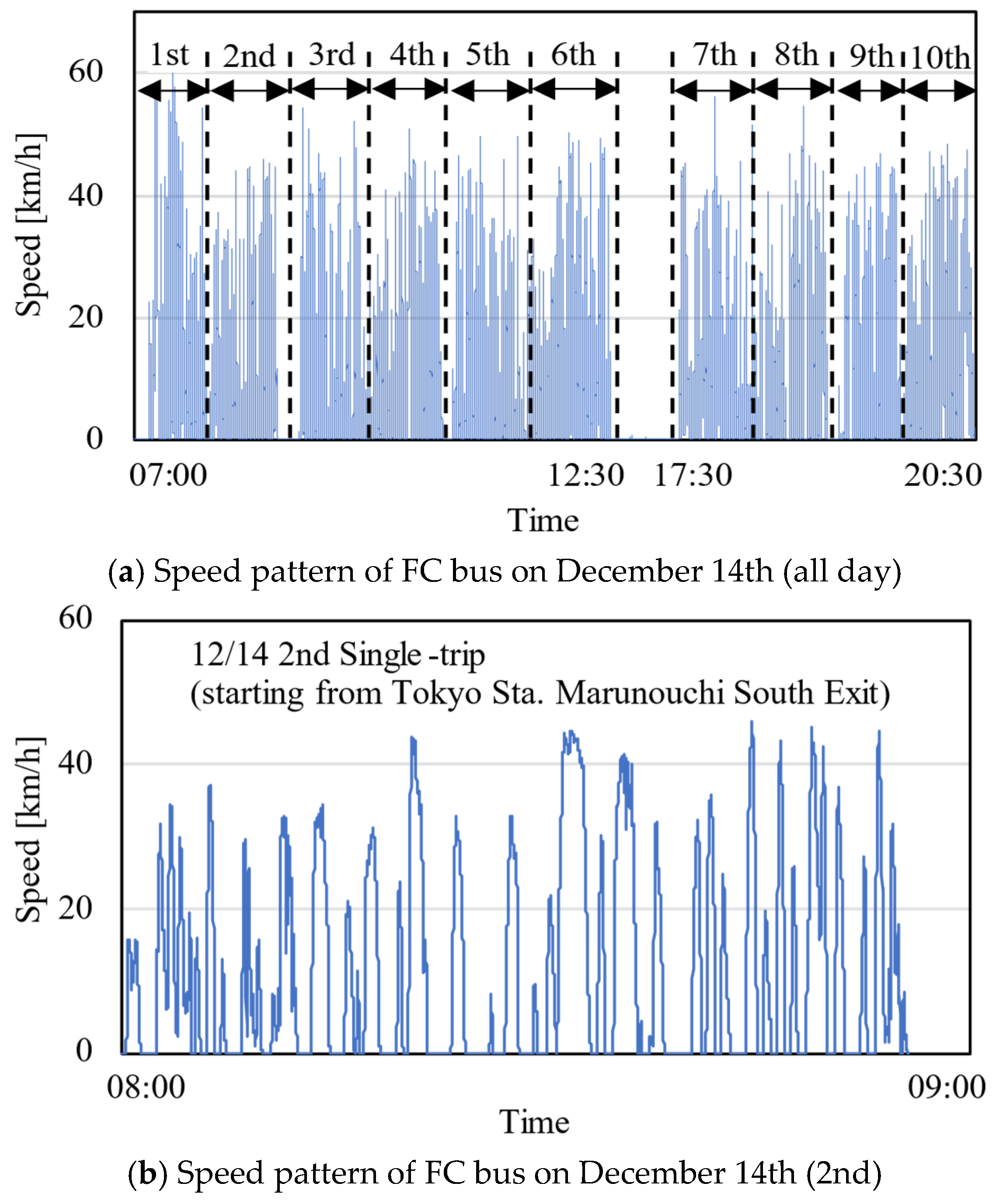

2.2. Survey Period and Equipment Used

3. Survey Results and Analysis Focusing on the Acceleration / Deceleration of Route Buses When Starting and Stopping at Bus Stops

3.1. Separation and Extraction of Different Types of Starts and Stops (Bus Stop / Traffic Signal / Other)

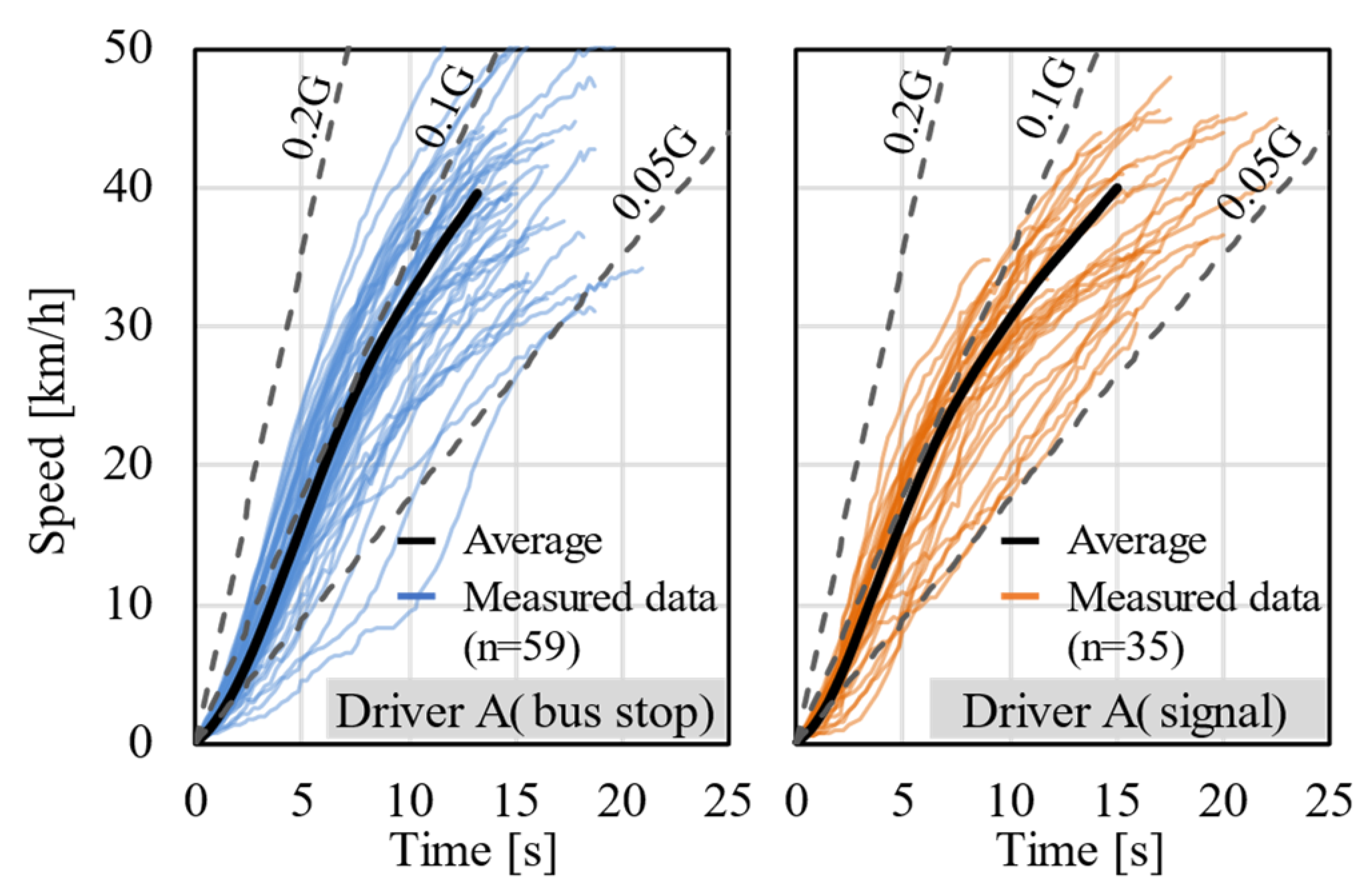

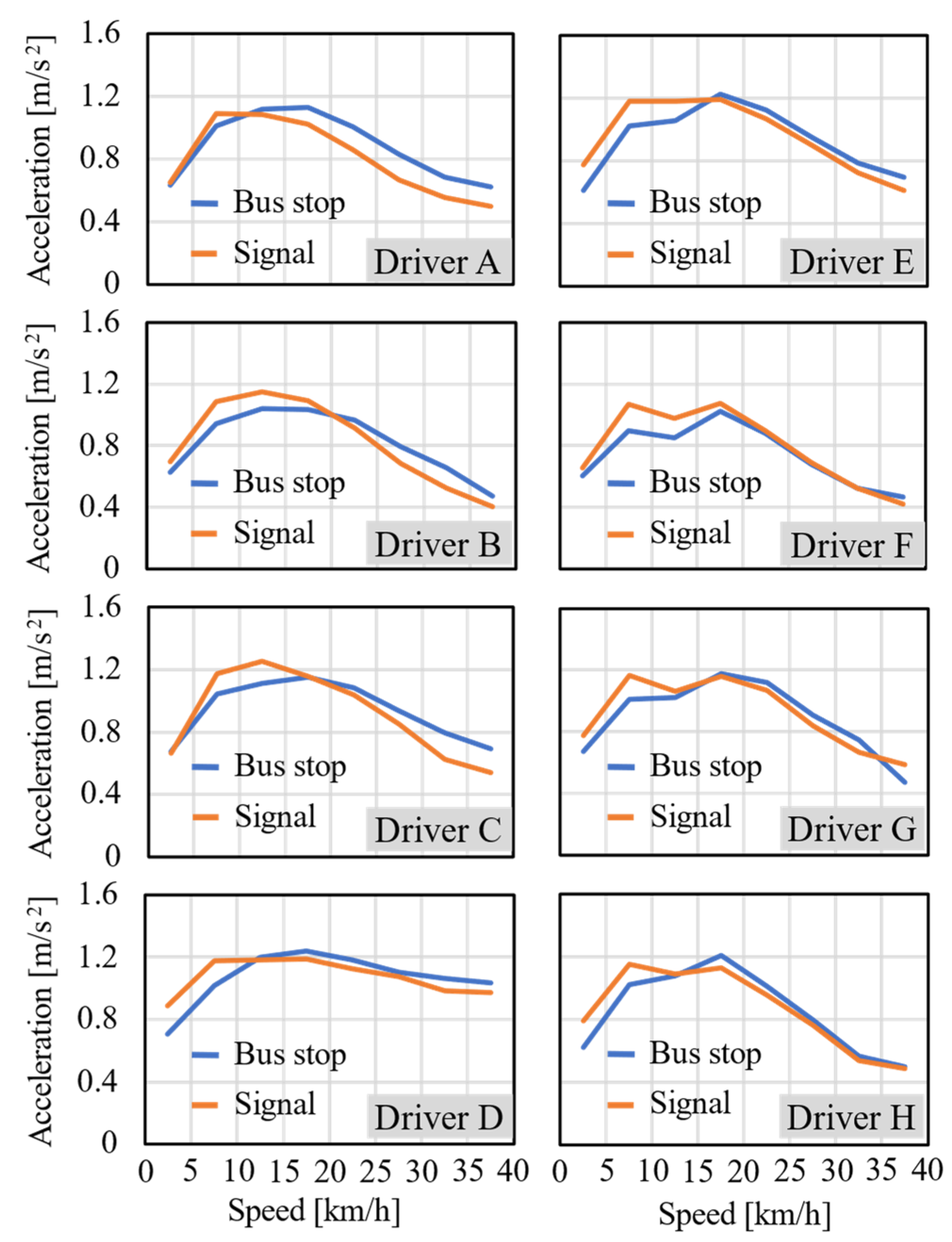

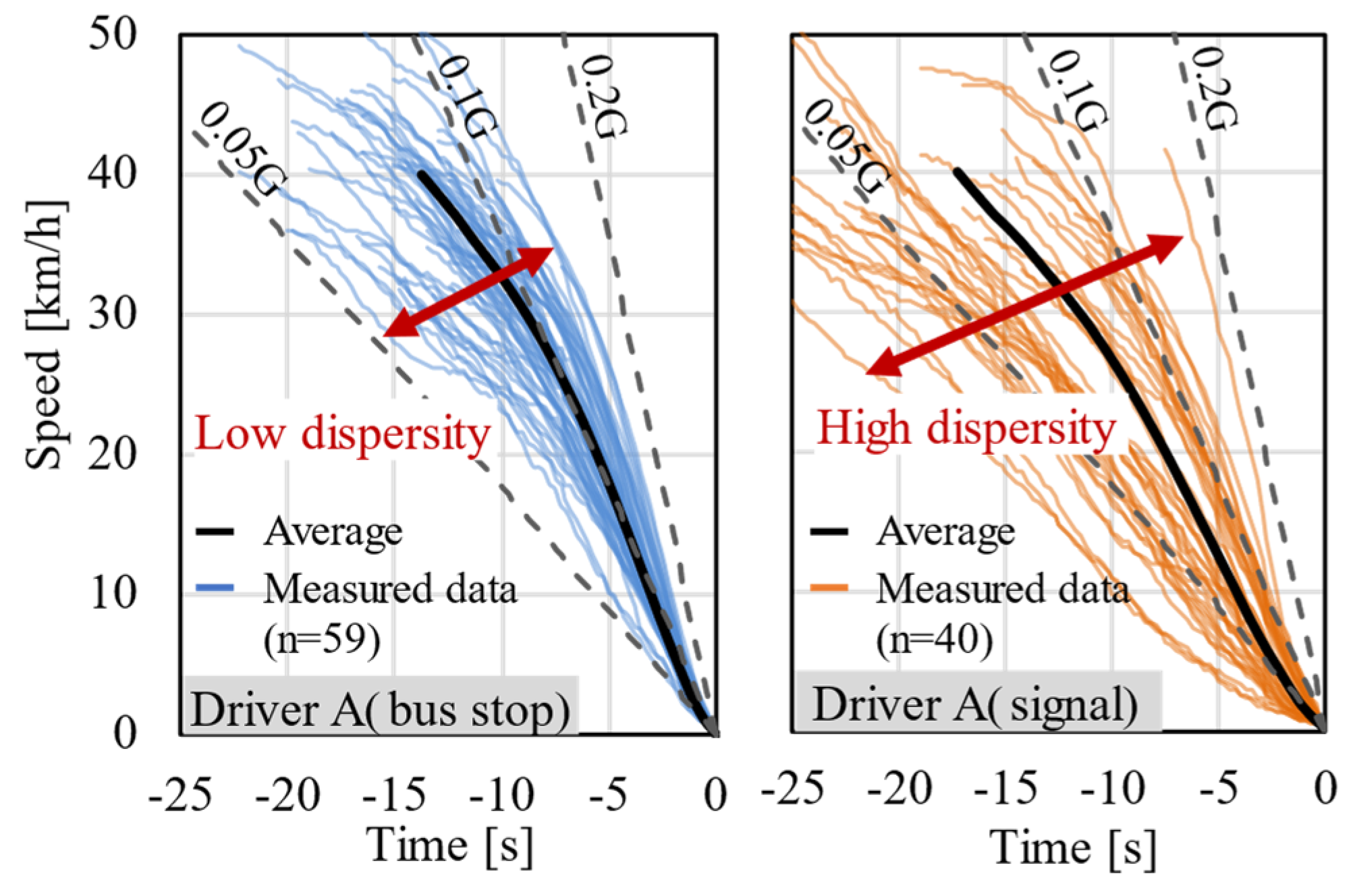

3.2. Comparative Analysis of Start Acceleration at Bus Stops and Start Acceleration at Traffic Signals

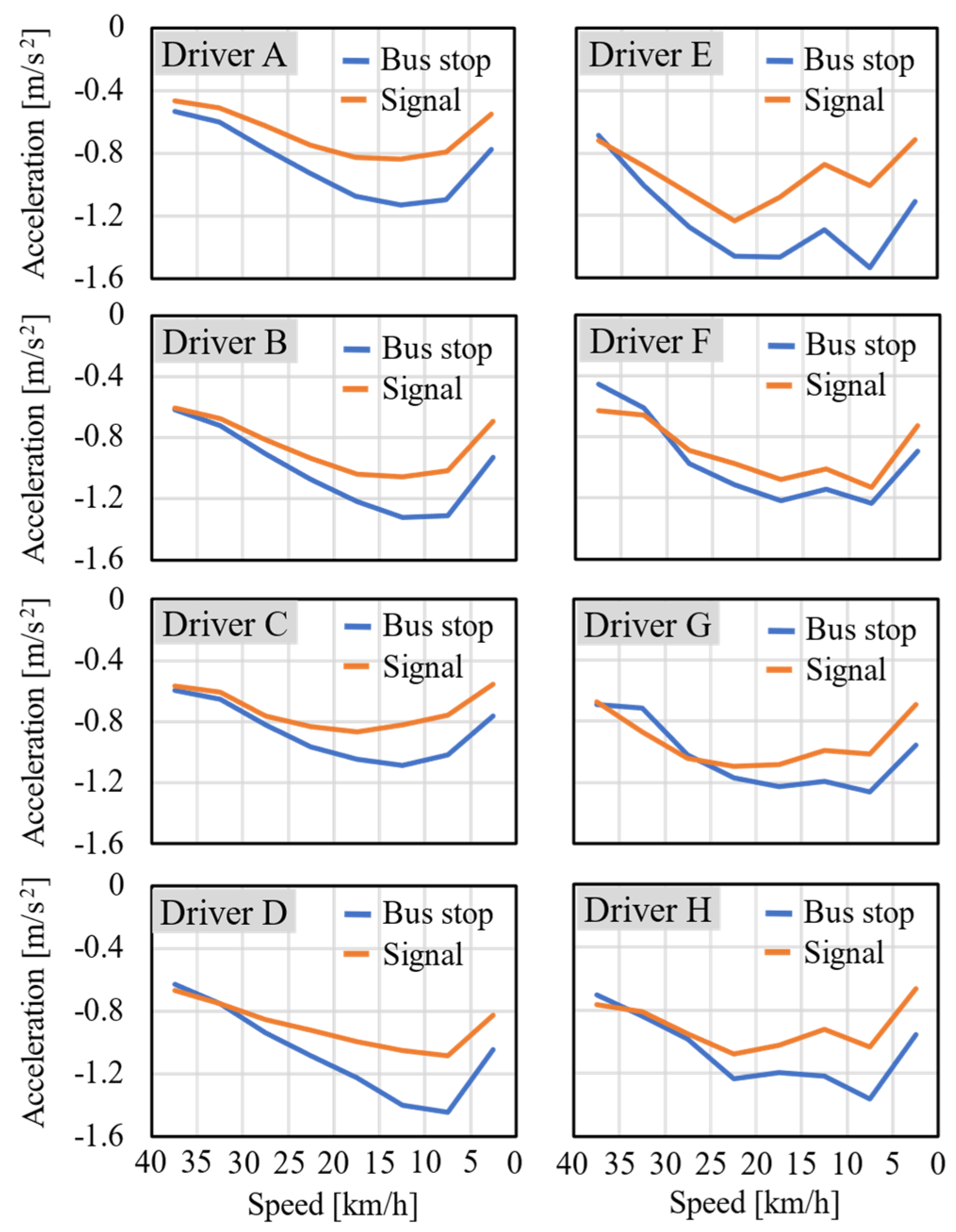

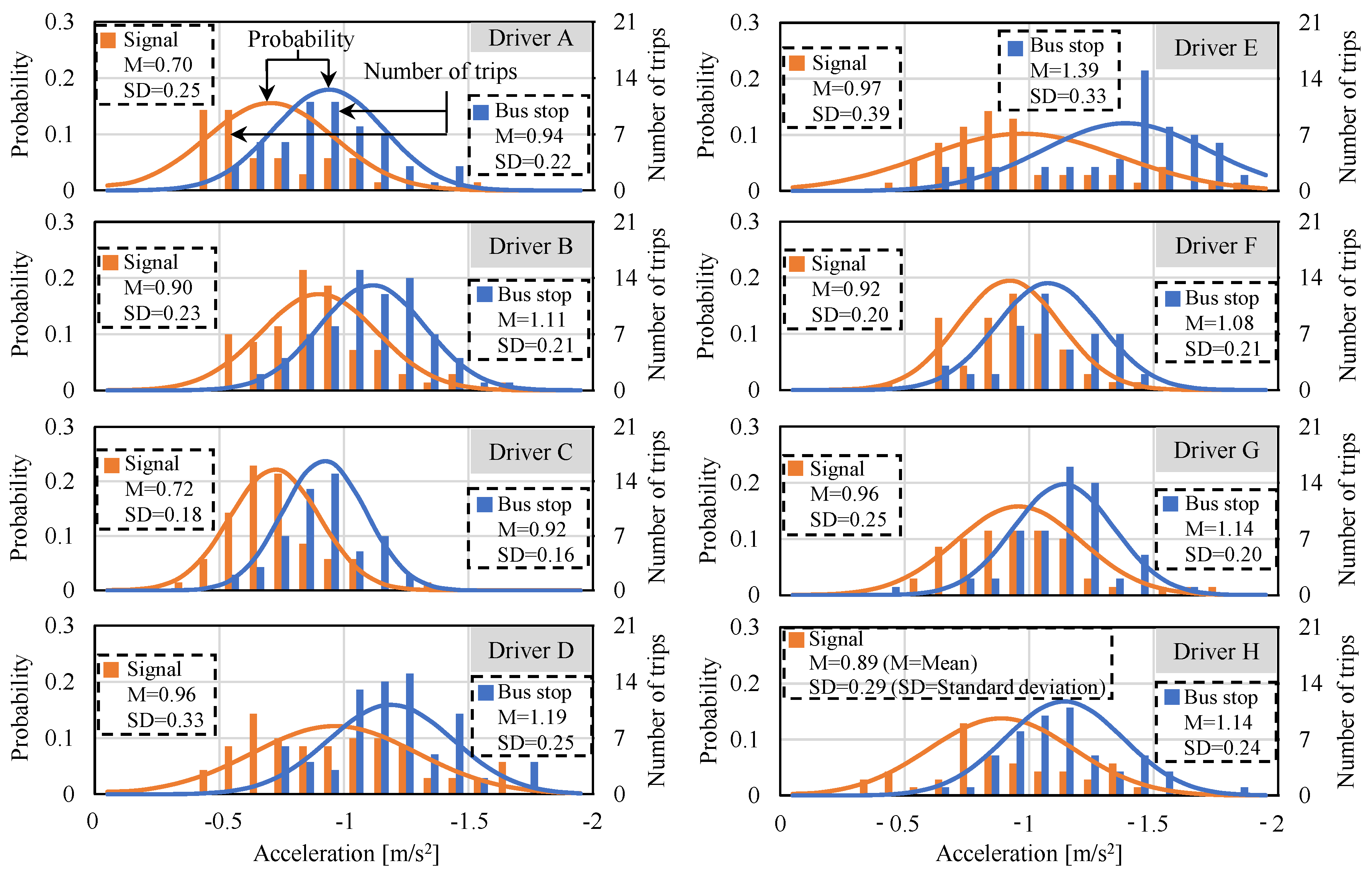

3.3. Comparative Analysis of Stop Deceleration at Bus Stops and Stop Deceleration at Traffic Signals

4. Survey Result and Comparative Analysis of Speed Change Patterns Between Fuel Cell Buses and Diesel Buses

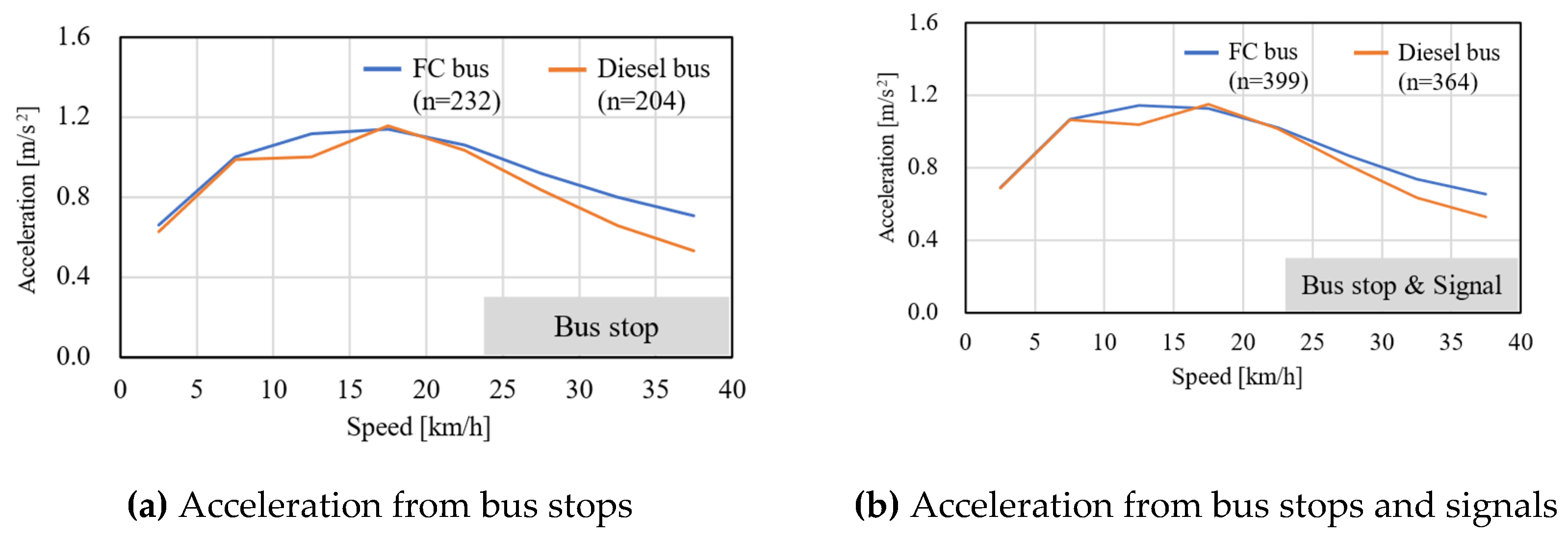

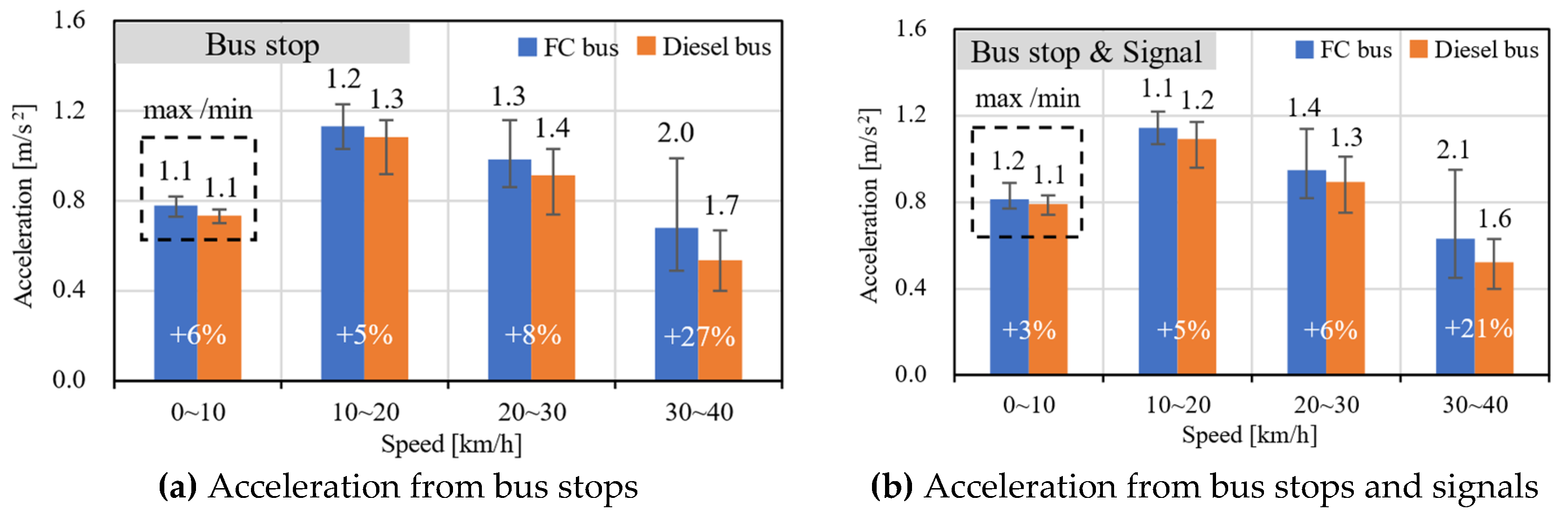

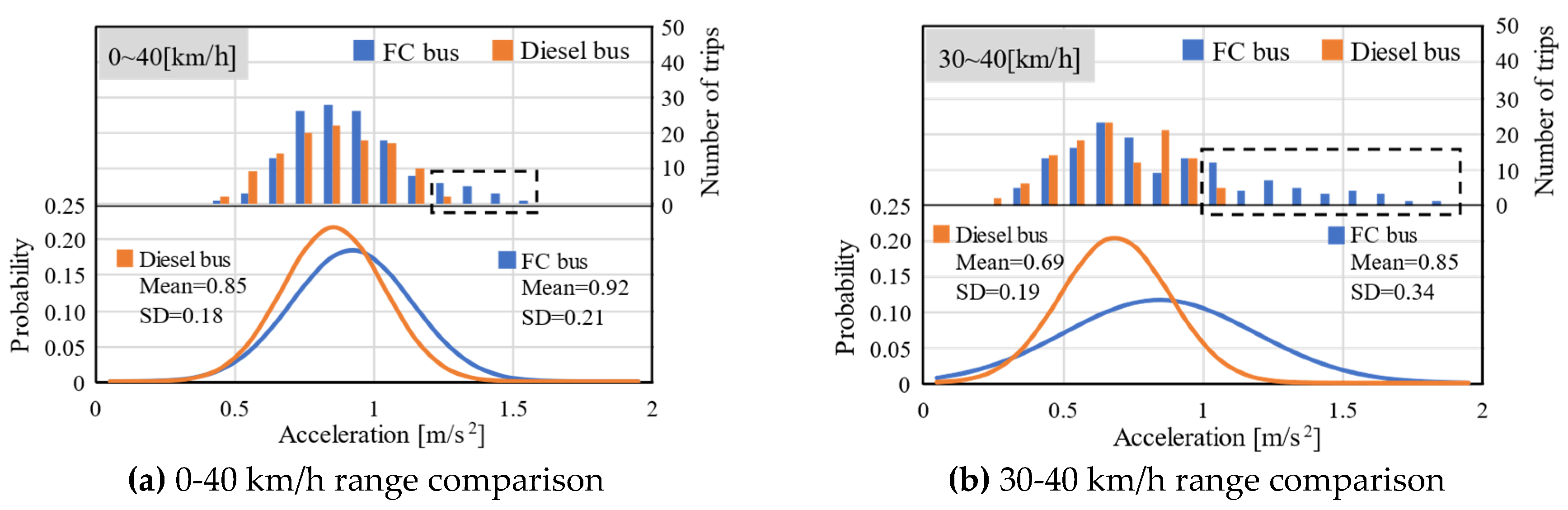

4.1. Comparative Analysis of Acceleration Intensity at the Start

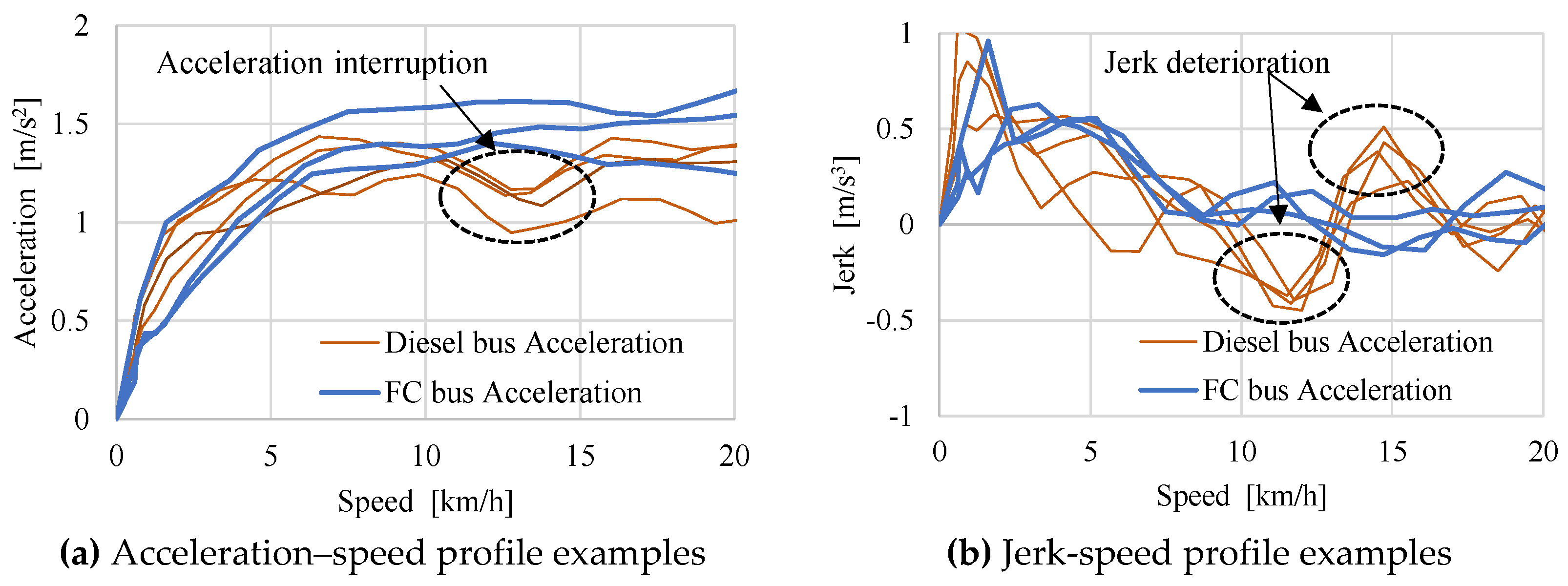

4.2. Analysis of the Negative Impact of Gear Shifting During the Start of Acceleration of Diesel Buses

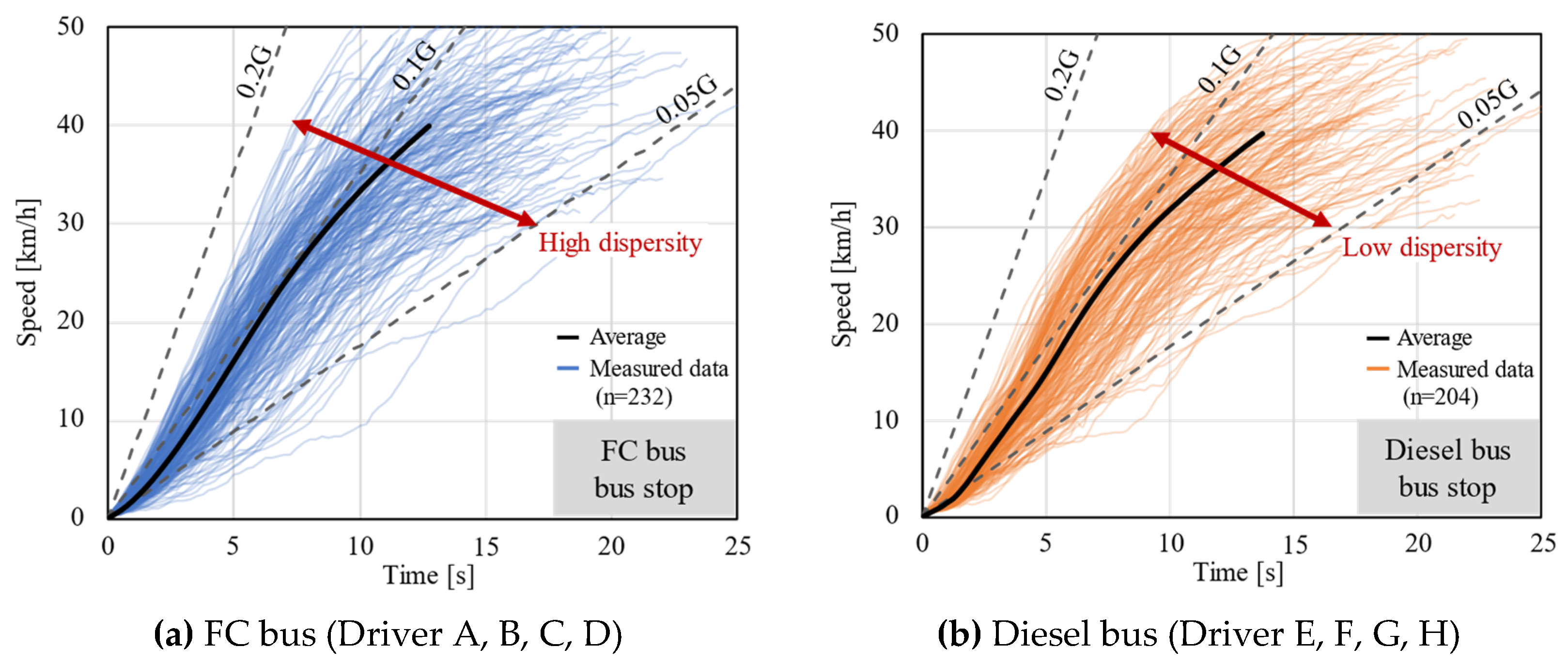

4.3. Comparative Analysis of Individual Differences in the Speed Change Pattern When Starting

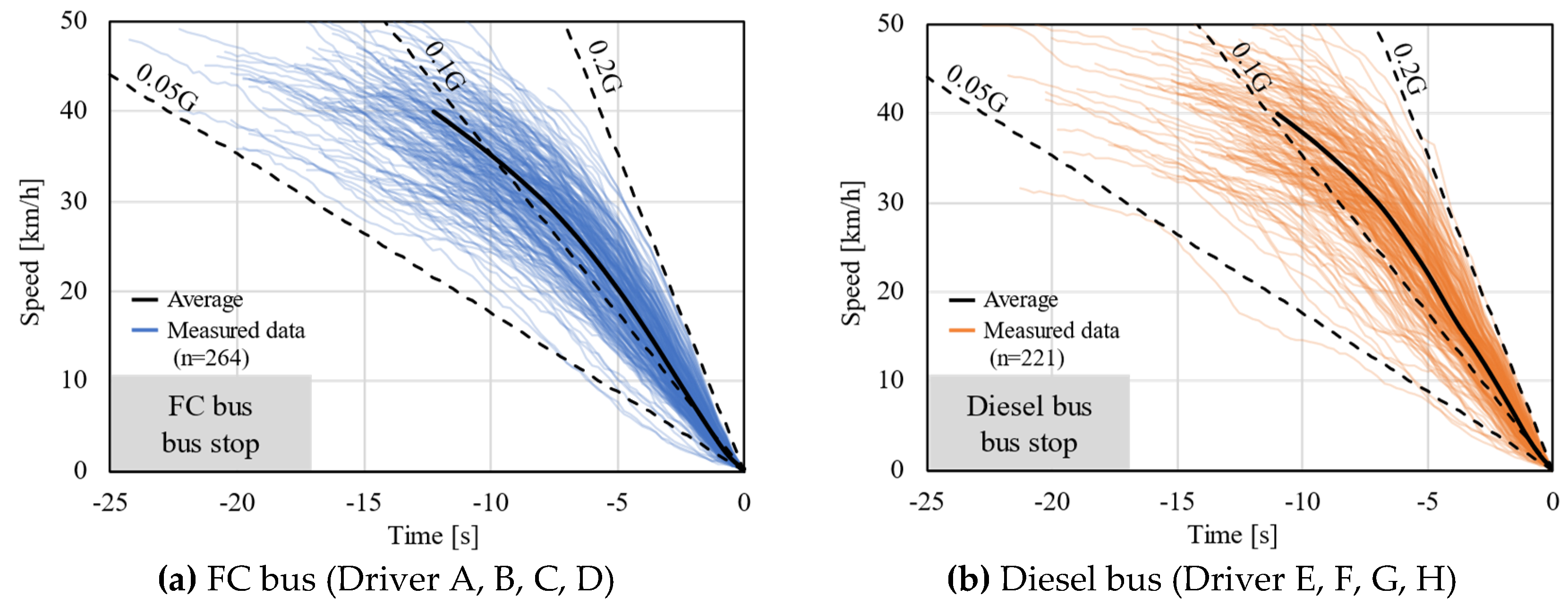

4.4. Comparative Analysis of the Speed Change Pattern When Stopping

5. Conclusions

- I.

- Regarding the start of acceleration at bus stops, unique to regular route buses, it was pointed out that the start of acceleration at bus stops is weaker than the start of acceleration at traffic signals during the first half of acceleration (in the low-speed region), and the reasons for this were clarified. Furthermore, it was elucidated that during the second half of the start of acceleration at bus stops (in the medium-speed region), acceleration is stronger, and the reason for this was due to the desire to reach cruising speed quickly to prevent rear-end collisions. Generally, the acceleration performance of motor-driven vehicles is superior to that of engine-driving vehicles, and it is widely understood that this characteristic is well-liked by bus drivers. Moreover, the difference in performance was verified, primarily during the second half of the start of acceleration at bus stops (in the medium-speed region).

- I.

- II. Regarding the stop deceleration at bus stops, unique to regular route buses, the characteristics of “strong deceleration when stopping at bus stops” and a “low degree of dispersion when stopping at bus stops,” as well as their reasons, were elucidated. It was pointed out that the latter, in particular, has the potential to facilitate the narrowing down of the regeneration setting, which contributes to improving electricity consumption during electrification to a significant degree.

- I.

- III. We concluded that the “no gear shifting” characteristic makes acceleration easy during departing from a bus stop in addition to the “high acceleration performance” of motor-driven vehicles. Furthermore, by calculating and analyzing the jerk amount, we could quantitatively demonstrate the comfortable driving experience while riding on this type of bus where there is no shock due to gear shifting.

- I.

- IV. While the “high acceleration performance” of motor-driven vehicles produces “individual differences in the speed change patterns,” this does not translate to “individual differences in electricity consumption” owing to the characteristics of this type of vehicle [30,31]. With engine-driven vehicles, measures, such as “slow acceleration,” are strongly encouraged to realize eco-driving, and any driving style that deviates from these measures is avoided. However, with motor-driven vehicles, the driver does not need to be too concerned about the speed history during acceleration. This characteristic also suggests a benefit in terms of the electrification of buses.

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Land–climate interactions. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/4/2022/11/SRCCL_Chapter_2.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Polar Regions. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/3/2022/03/05_SROCC_Ch03_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low-Lying Islands, Coasts and Communities. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/3/2022/03/06_SROCC_Ch04_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). World energy outlook 2022 [R]. IEA, 2022, Paris. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/energy/worldenergy-outlook-2022_3a469970-en (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Sorrell, S.; Speirs, J.; Bentley, R.; Brandt, A.; Miller, R. Global Oil Depletion: A Review of the Evidence. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 5290–5295. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301421510003204 (accessed on 8 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mikael Höök, Robert Hirsch, Kjell Aleklett, Giant oil field decline rates and their influence on world oil production, Energy Policy 2009, 37, 2262–2272. [CrossRef]

- MAZZA, Daniele; CANUTO, Enrico. Depletion of fossil fuel reserves and projections of CO $ _2 $ concentration in the Earth atmosphere. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.01911. [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Summary for Policymakers. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2022/06/SPM_version_report_LR.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Lacal Arantegui, R.; Jäger-Waldau, A. Photovoltaics and wind status in the European Union after the Paris Agreement. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 2460–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, A.; Smyth, B.M.; Pukšec, T.; Markovska, N.; Duić, N. A review of developments in technologies and research that have had a direct measurable impact on sustainability considering the Paris agreement on climate change. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 68, 835–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ng, E.C.Y.; Zhou, J.L.; Surawski, N.C.; Chan, E.F.C.; Hong, G. Eco-driving technology for sustainable road transport: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 93, 596–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehry, A.S.; Belloumi, M. Study of the environmental Kuznets curve for transport carbon dioxide emissions in Saudi Arabia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 75, 1339–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Summary of the Paris Agreement. Available online: http://bigpicture.unfccc.int/#content-the-paris agreement (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- United Nations. Paris Agreement—Status of Ratification. Available online: http://unfccc.int/paris_agreement/items/9444.php (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Bryła, P.; Chatterjee, S.; Ciabiada-Bryła, B. Consumer Adoption of Electric Vehicles: A Systematic Literature Review. Energies 2023, 16, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). World Energy Outlook 2024. IEA, 2024. Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/140a0470-5b90-4922-a0e9-838b3ac6918c/WorldEnergyOutlook2024.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Hawkins, T.R.; Singh, B.; Majeau-Bettez, G.; Strømman, A.H. Comparative Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Conventional and Electric Vehicles. Journal of Industrial Ecology 2013, 17, 53–64. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1530-9290.2012.00532.x (accessed on 8 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Inderbitzin, A.; Bening, C. Total Cost of Ownership of Electric Vehicles Compared to Conventional Vehicles: A Probabilistic Analysis and Projection Across Market Segments. Energy Policy 2015, 80, 196–214. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301421515000671 (accessed on 8 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Nordelöf, A.; Messagie, M.; Tillman, A.-M.; Ljunggren Söderman, M.; Van Mierlo, J. Environmental Impacts of Hybrid, Plug-in Hybrid, and Battery Electric Vehicles—What Can We Learn from Life Cycle Assessment? International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 2014, 19, 1866–1890. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11367-014-0788-0 (accessed on 8 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Transportation Tokyo Metropolitan Government, Toei Bus Real-Time Information Service. Available online: https://tobus.jp/blsys/navi?LCD=&VCD=cslrsi&ECD=NEXT&RTMCD=181 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Clairand, J.-M.; Guerra-Terán, P.; Serrano-Guerrero, X.; González-Rodríguez, M.; Escrivá-Escrivá, G. Electric Vehicles for Public Transportation in Power Systems: A Review of Methodologies. Energies 2019, 12, 3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.-W.; Tong, H.-Y. Comparisons of Driving Characteristics between Electric and Diesel-Powered Bus Operations along Identical Bus Routes. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Yang, W.-h.; Ihara, Y.; Kamiya, Y. Developing a Simple Electricity Consumption Prediction Formula for the Pre-Introduction Prediction for Electric Buses. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyota Motor Corporation, Mass-produced Fuel Cell Bus – SORA. Available online: https://global.toyota/jp/newsroom/corporate/21862392.html (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- The Mitsubishi Fuso Truck and Bus Corporation, AERO STAR. Available online: https://www.mitsubishi-fuso.com/ja/product/aero-star/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- UBLOX Company, C099-F9P Application board (rev, E) User guide. Available online: https://content.u-blox.com/sites/default/files/documents/C099-F9P-AppBoard_UserGuide_UBX-18063024.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Wang, F.; Sagawa, K.; Inooka, H. A Study of the Relationship between the Longitudinal Acceleration / Deceleration of Automobiles and Ride Comfort. The Japanese Journal of Ergonomics 2000, 36, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao Li, Yoichi Hori, Realtime Smart Speed Pattern Generator for EVs to Improve Safety and Ride Comfort taking Driver’s Command Change and Limits of Acceleration and Jerk into account, Papers of Technical Meeting on Industrial Instrumentation and Control and Mechatronics Control, IEE Japan, Vol. IIC-06, No. 16-39. 41-44, pp.5-9, 2006.

- Nobuki Akamatsu, Ikkyu Aihara, Tohru Kawabe, Driving Characteristics Analysis Using Ride Comfort Index Based on Time Series Data of Longitudinal and Lateral Accelerations, Proceedings of IFAC Japan Congress 2018, No. 13D5, pp. 1292–1297, 2018.

- Fang, Y.; Yang, W.-h.; Kamiya, Y.; Imai, T.; Ueki, S.; Kobayashi, M. Speed Change Pattern Optimization for Improving the Electricity Consumption of an Electric Bus and Its Verification Using an Actual Vehicle. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Huang, S.-H.; Kobayashi, K.; Yang, W.-H.; Kamiya, Y. Optimization of Speed Change Pattern for Improving Electricity Consumption of Electric Heavy-duty Vehicles and Verification through Actual Vehicle Chassis Dynamometer Testing. Journal of Transactions of Society of Automotive Engineers of Japan 2024, 55, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

| Bus stop | Signal | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) The number of total trips | — | — | 35 |

| (b) The number of starts & stops (≧100 m) | 31 | 15 | — |

| (c) The number of starts & stops (≧100 m, ≧30 km/h) | 15 (68%) | 7 (32%) | — |

| Bus stop | Signal | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) The number of total trips | — | — | 395 |

| (b) The number of starts & stops (≧100 m) | 295 | 165 | — |

| (c) The number of starts & stops (≧100 m, ≧30 km/h) | 118 (61%) | 75 (39%) | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).