1. Introduction

With the ongoing enhancement of social material living standards, the demand for high-quality meat is increasing. People are placing greater emphasis on the tenderness, taste and flavor of meat. Intramuscular fat (IMF) is a type of fat that is deposited between muscle fibers. The varying levels of IMF contribute to different degrees of Marbling in the muscle, which directly affects the tenderness, flavor, juiciness and other quality indicators of meat [

1,

2] , For example, one research showed that IMF can weaken the association between collagen fibers, making muscle fibers more likely to break during chewing and thereby enhancing muscle tenderness[

3]. In addition, IMF is rich in phospholipids and unsaturated fatty acids, such as palmitic acid, stearic acid, and linoleic acid. These compounds can produce volatile flavor substances through the Maillard reaction and thermal degradation during the cooking process of meat products, enhancing the overall flavor of the meat [

4,

5]. Therefore, gaining acomprehensive understanding of the regulatory mechanisms governing IMF deposition and selecting effective strategy to increase IMF content will improve meat quality, satisfy the demand for both health and flavor, and enhance the economic value of the meat.

In comparison to other types of fat storage, IMF is the most recent to develop. It primarily accumulates within the connective tissue between muscle fiber bundles, such as longissimus dorsi, pectoralis longus and biceps femoris. This deposition is influenced by various factors, including the breeds of the animal, its age, gender, and nutritional status. Breeds [

6]. Some research findings indicate that animal breeds influence the ability for adipose deposit breeds. Tshabalala et al. found Damara and Dorper sheep yielded more dissectible fat and lean meat than African indigenous and Boer goat breeds. Additionally, the sheep mutton was more tender, juicy and greasy, while being less chewy than goat patties [

7].Casey demonstrated that the fat content in the carcass muscle of Boer goat was higher than that of African native sheep, and the carcass muscle was also more tender in taste [

8]. In recent years, advancements in metagenomic sequencing technology have led to an increasing number of studies revealing that the composition and structure of microorganisms in the digestive systems of livestock influence IMF deposition. Zeng et al. found a significant correlation between the abundance of

Bacteroides,

RuminococcaceaeP7,

Eubacterium ruminant, and

Prevotella in the rumen and the fatty acid content of the longissimus dorsi muscle in Hechuan white goats [

9].Adding

Clostridium butyricum to the diet can greatly enhance the IMF content in the leg muscles of broiler chickens [

10]. The significant presence of

Klebsiella and

Escherichia-Shigell in the intestines of yellow chickens is associated with increased levels of total cholesterol (TC) and triglycerides (TG) in the blood, which contributes to fat accumulation [

11]. Furthermore, microbial metabolites like short chain fatty acids (SCFA

S) can affect animal appetite and regulate host lipid metabolism by modulating nutrient detection, nerve signal transmission, and hormone release within the digestive system [

12,

13]. Although the gut microbiota and their byproducts significantly influnce the lipid metabolism of the host. There is insufficient research regarding the IMF deposition in various animal breeds from a microbial standpoint.

Longdong cashmere goats and Tan sheep are unique breeds found in China, cherished by consumers for their tender, flavorful meat [

14,

15]. This study focused on grazing Longdong cashmere goats and Tan sheep to compare various factors such as carcass quality, IMF content, lipid levels, key enzymes involved in lipid metabolism, c SCFAs content, as well as bacterial diversity and functional differences. The aim was to identify significant microorganisms associated with to IMF deposition and to offer effective strategies to improve meat quality.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

Ten Longdong cashmere ewes and ten Tan sheep ewes with one-year-old that were grazed in the same area of Huanxian County, Qingyang City, Gansu Province of China were selected to randomly in this study. Jugular vein blood was collected from each animal. After centrifugation, serum samples were obtained for the determination of lipid-related indicators. After slaughter, the hot carcass weight was measured and the GR value was determined. The dressing percentage is obtained by the ratio of carcass weight to live weight. Muscle tissues (shoulder, longissimus dorsi, rump, and rib chops meat), digestive glands (liver, pancreas, and duodenum), and gut chyme (rumen, abomasum and colon) were collected. All samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at −80 °C until use.

2.2. Determination Content and Method

IMF content of muscle tissue samples was determined by soxhlet fat extraction (ANKOM XT15 Extractor, ANKOM Technology, USA). The serum samples were used to determine the concentrations of HDL, LDL, VLDL, FFA, TG, and TC using ELISA kits (Gansu Hongaodesi Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China). The content of FAS and HSL in digestive gland and gut chyme were determined by using FAS Elisa kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China ) and HSL Elisa kit ( Fankew, Shanghai kexing Trading Co., Ltd., Ltd. ).The content of SCFAs in the gut chyme was analyzed by referring to the method of Tangerman [

13] (Agilent 6890 N Network Gas Chromatograph, Agilent Technologies, USA). Utilizing 16S rRNA sequencing technology and bioinformatics techniques, the structure, composition, and functional predictions of the microbial community in the gastrointestinal contents were analyzed. The specific process includes:

2.2.1. Microbial DNA Extractions and PCR Amplification

Microbial DNA was extracted from goat and sheep intestinal contents samples using the E.Z.N.A.® Stool DNA Kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, USA) according to manufacturer’s protocols. The full-length bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA gene was amplified via PCR using primers 27F (5’-AGRGTTYGATYMTGGCTCAG-3’) and 1492R (5’-RGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3’), where the barcode was an eight-base sequence unique to each sample.

2.2.2. Processing of Sequencing Data

SMRTbell libraries were prepared from the amplified DNA by blunt-ligation with manufacturer’s instruction (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA) and sequenced on dedicated PacBio Sequel II using the Sequencing Kit 2.0 chemistry. PacBio raw reads were processed using the SMRT Link Analysis software (version 9.0) to obtain de-multiplexed circular consensus sequence reads [

16]. Raw reads were processed through SMRT Portal to filter sequences for length (<800 or >2500 bp) and quality. Sequences were further filtered by removing barcode, primer sequences, chirmas and sequences if they contained 10 consecutive identical bases. Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were clustered with 98.65% similarity cutoff using UPARSE (version 7.1) and chimeric sequences were identified and removed using UCHIME [

17]. The phylogenetic affiliation of each 16S rRNA gene sequence was analyzed by the UCLUST algorithm (v1.2.22q) [

18] against the Greengenes2 16S rRNA database using a confidence threshold of 80% [

19] (Greengenes2 unifies microbial data in a single reference tree. nature biotechnology, 2023). The raw reads were deposited into the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database (Accession Number: PRJNA1214480).

2.2.3. Functional Prediction of the Microbial Genes

Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States (PICRUSt2) [

20] program based on the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database was used to predict the functional alteration of microbiota in different samples. The OTU data obtained were used to generate BIOM files formatted as input for PICRUSt2 with the make.biom script usable in the Mothur [

21]. OTU abundances were mapped to Greengenes2 OTU IDs as input to speculate about the functional alteration of microbiota.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The independent sample T test of SPSS software (version20.0) was used to compare the differences in carcass quality (dressing percentage and GR value), content of IMF, lipid level, Lipid metabolism enzymes and content of SCFAs between Longdong cashmere goats and Tan sheep. Differences were considered significant at

p<0.05. The Chao1, Shannon diversity indices were analyzed based on the abundance of each OTU in each sample by vegan package [

16]. The statistical difference in alpha diversity between the four groups was measured by employing the T-test. The PCoA plotting analysis was performed based on the Bray–Curtis distance matrix among samples by using the ape package [

22]. One-way permutational analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was performed to assess the statistical significance between groups. The NMDS plotting analysis was performed based on the Unweighted UniFrac distance marix using the vegan package [

23]. The differences in microbial genera were assessed using T-test, while the wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for statistical analysis of various functional pathways. The Spearman’s correlation coefficients were assessed to determine the relationships between age and chemical factor, microbiota and content of IMF and SCFAs. All differences were considered significant at

p<0.05.

3. Results

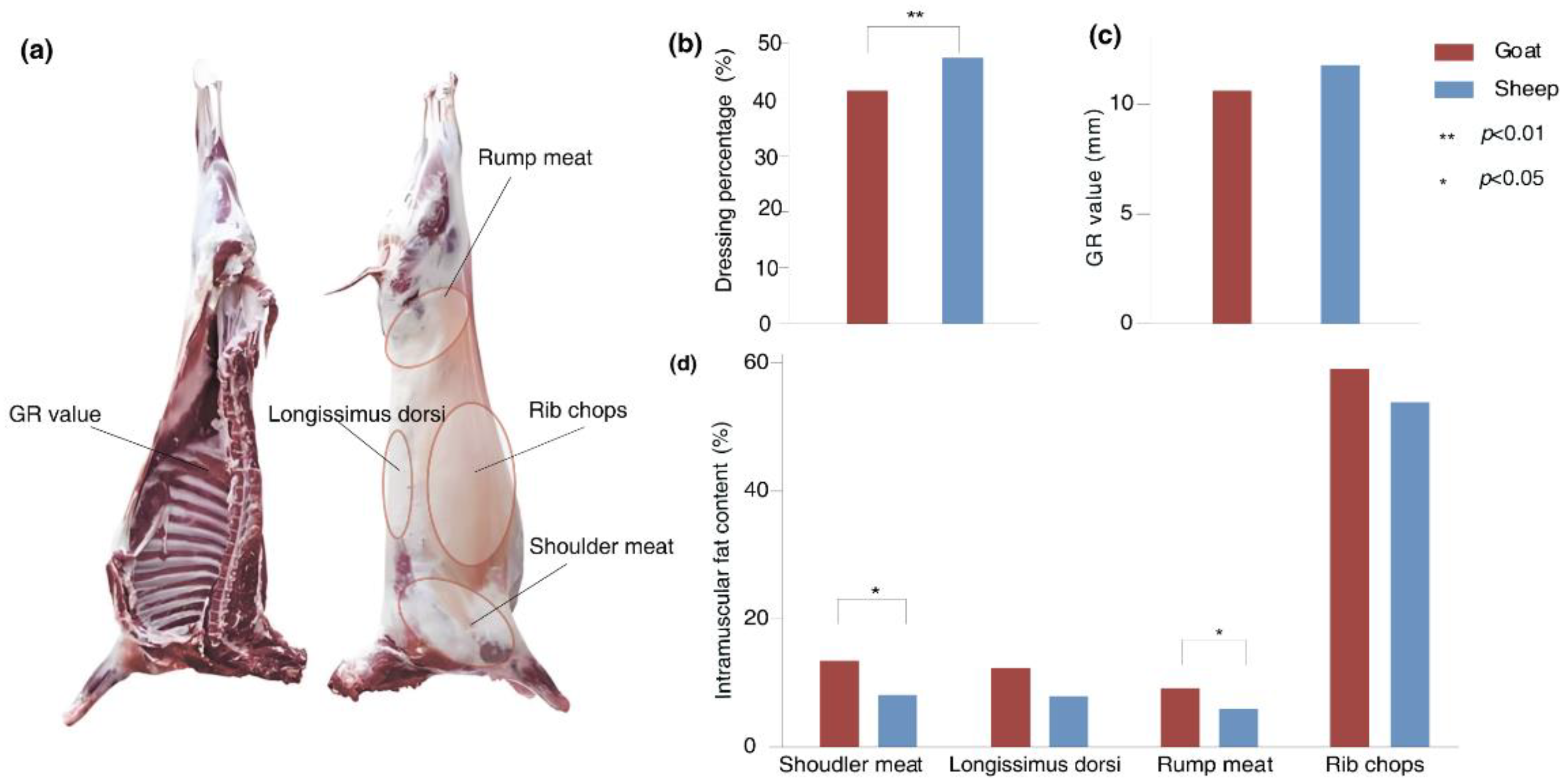

3.1. The Differences in Dressing Percentage, GR Value and IMF Content Between Goats and Sheep

To evaluate the impact of breeds on carcass traits and meat quality, we determined the dressing percentage, GR value, and IMF content in shoulder meat, longissimus dorsi, rump meat and rib chops of Longdong cashmere goats and Tan sheep. The results showed that the dressing percentage of Tan sheep was significantly higher than that of Longdong cashmere goats (

p= 0.003), while the IMF content in shoulder meat (

p= 0.02) and rump meat (

p= 0.04) was notably lower. No significant differences were observed in GR value, or the IMF content of longissimus dorsi and rib chops between the two breeds (

Figure 1).

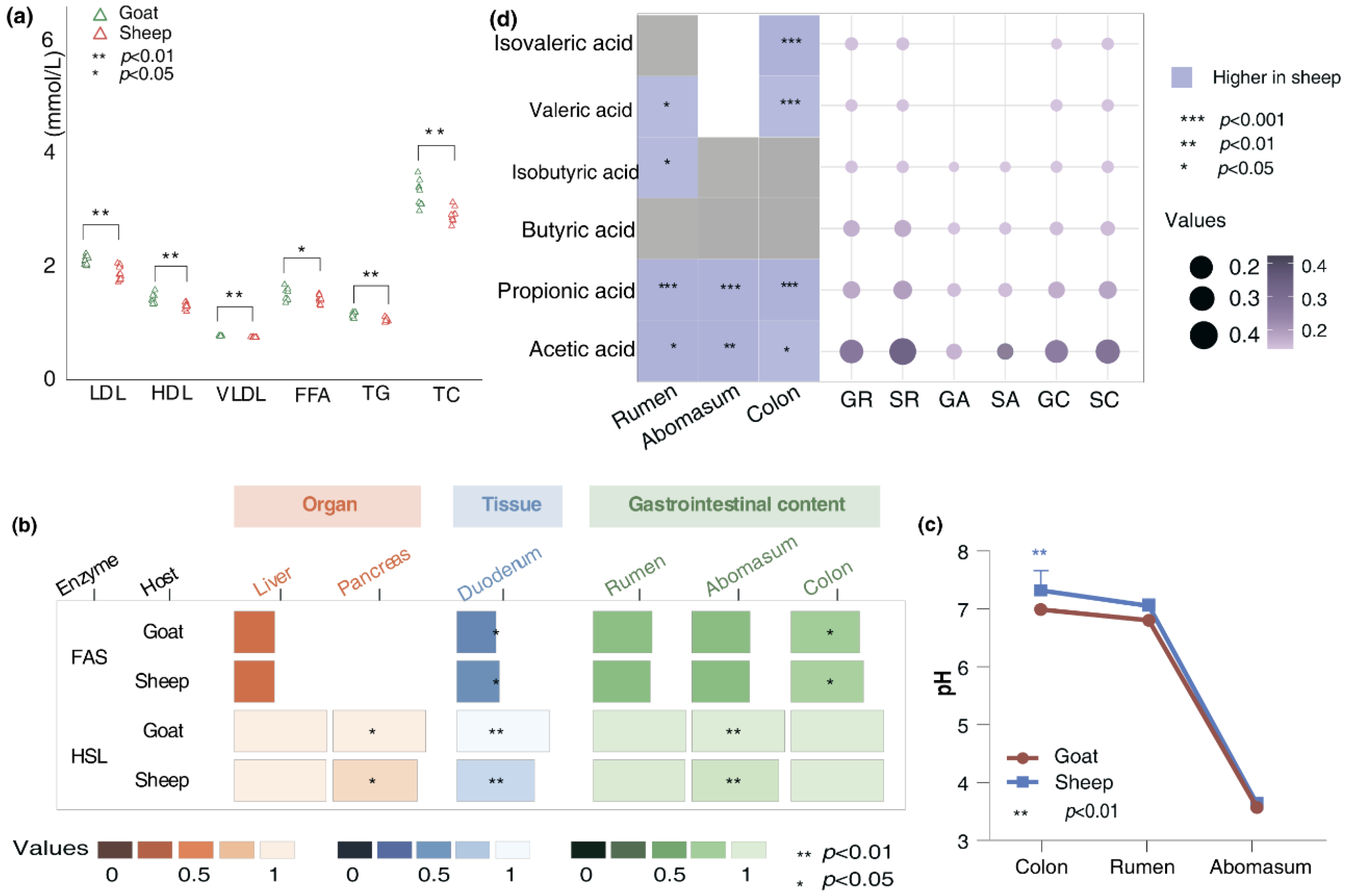

3.2. The Variations in Physiological Indicators and SCFAs Contents of Goats and Sheep

Studies have shown that the accumulation of fat is closely linked to lipid levels. When levels of TG, TC and other lipids increase, adipocyte tend to take in excess lipid substances, leading to greater fat accumulation [

24,

25]. Thus, we determined the levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (VLDL), TG, TC and free fatty acids (FFA) in the serum of Longdong cashmere goats and Tan sheep. The results showed that the levels of LDL (

p<0.001), HDL (

p=0.008), VLDL (

p<0.001), TG(

p<0.001), TC (

p<0.001) and FFA (

p=0.04) in goats were significantly higher than those in sheep (

Figure 2a). A series of enzymes regulated the process of animal fat deposition. Fatty acid synthase (FAS) and Hormone-sensitive triglyceride lipase (HSL) are the primary enzymes responsible for regulating the synthesis and breakdown of triglycerides. We used Elisa kit to determine the content of FAS and HSL in the liver, pancreas and duodenum. The results showed that the FAS content in the duodenum of goats was considerably lower compared to that in sheep (

p=0.04). In contrast, the HSL content in both the pancreas (

p=0.04) and duodenum (

p<0.001) were significantly higher than those found in sheep (

Figure 2b). We also determined the contents of those two enzymes in the chyme from the rumen, abomasum and colon. The results showed that, the HSL content in the abomasal chyme of goat was significantly higher compared to sheep (

p=0.004), whereas the FAS content in the colonic chyme was significantly lower (

p=0.01). These results imply that both the host and the microbiota might utilize enzymatic hydrolysis to jointly influence fat deposition in the body. Then a more in-depth analysis of the differences in pH value and the concentration of SCFAs in the gut chyme of the two breeds were conducted. We found that the pH in colon (

p<0.001) (

Figure 2c) and the concentrations of acetic acid, propionic acid, valeric acid and isovaleric acid (

p<0.001) in goats were significantly lower than those in sheep. The contents of acetic acid and propionic acid in the abomasum, as well as the contents of acetic acid, propionic acid, isobutyric acid and valeric acid in the rumen were notably lower compared to those found in sheep (

Figure 2d).

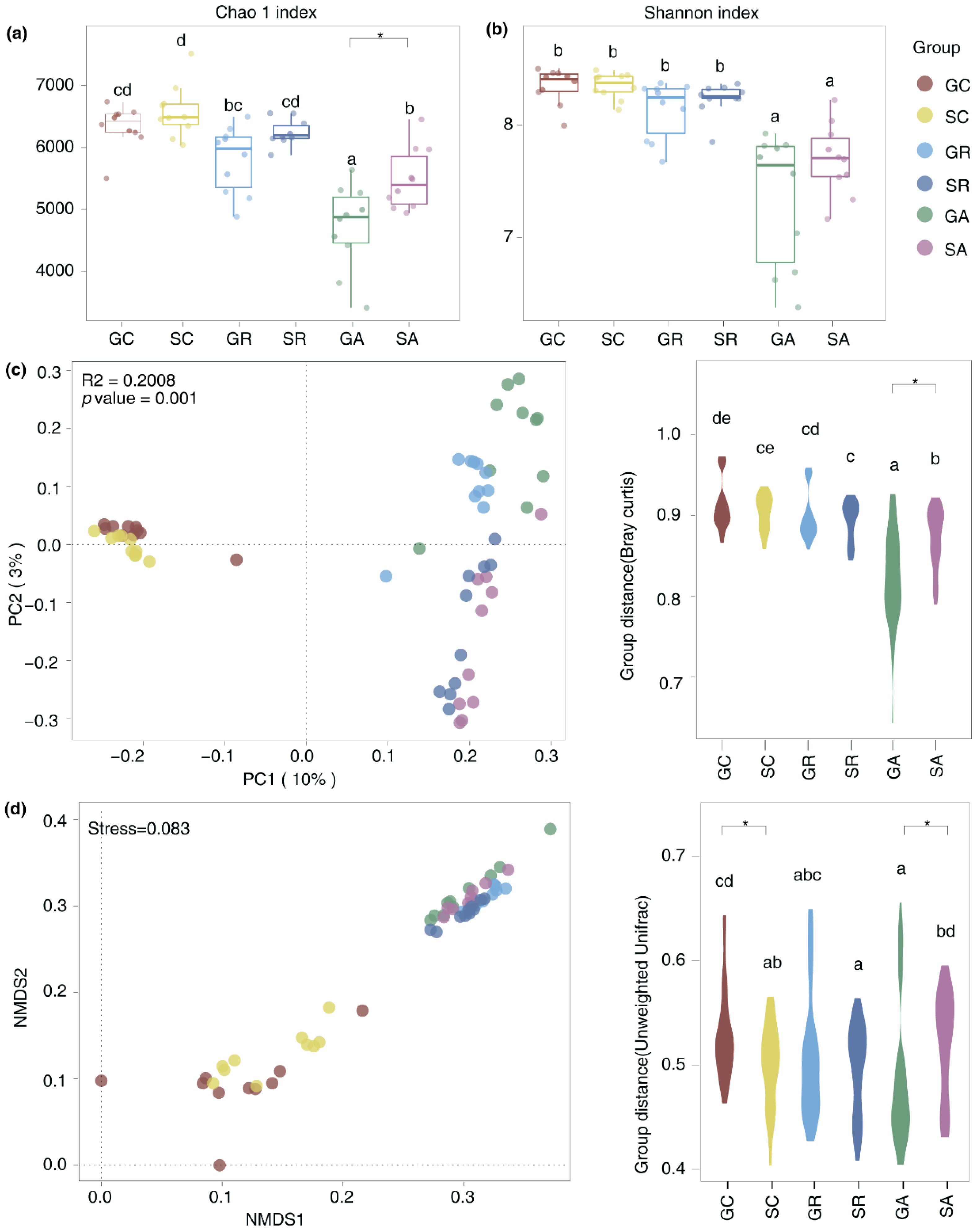

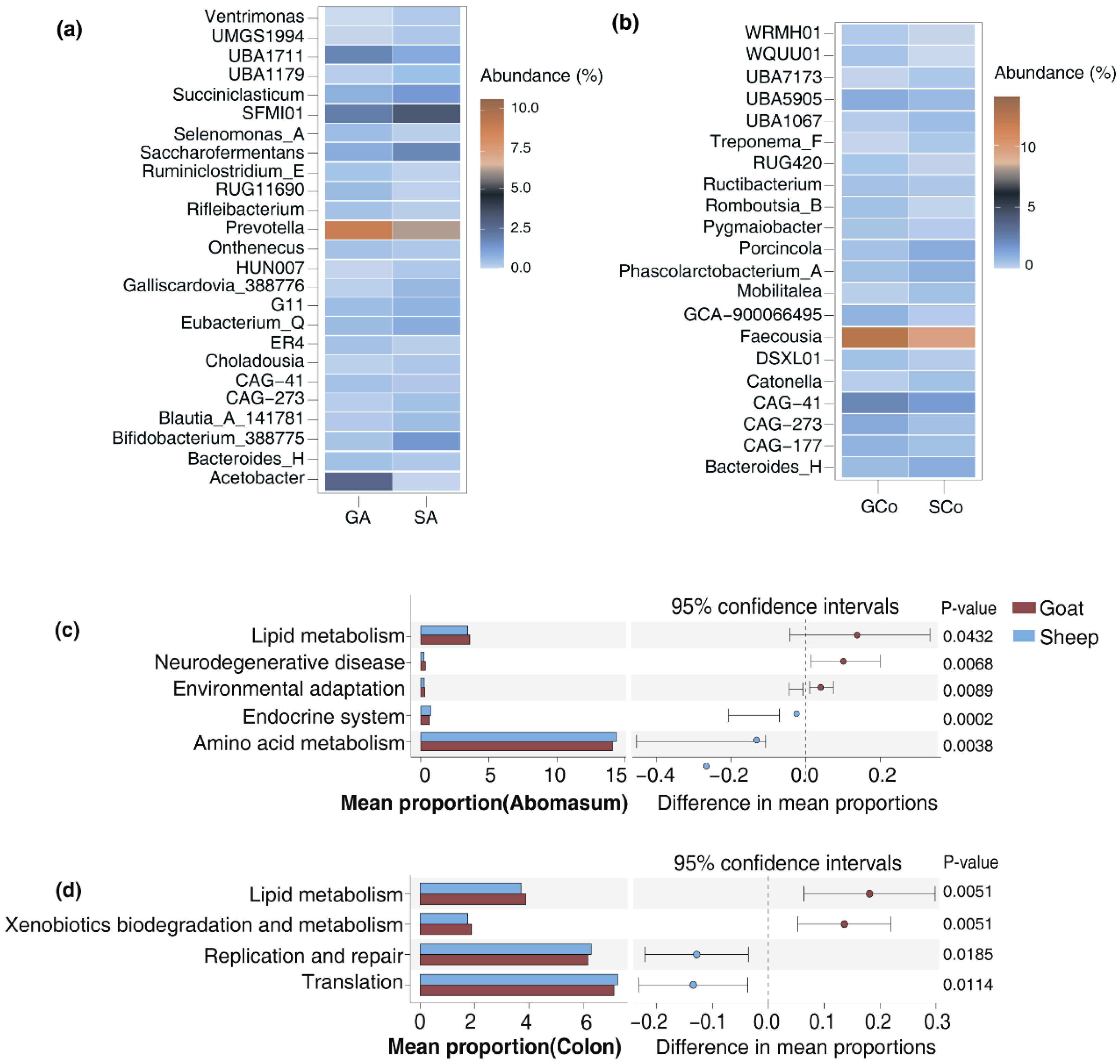

3.3. The Differences in the Gut Microbiota and Functional Profile Between Goat and Sheep

The alpha and beta diversity of the gut microbiota in Longdong cashmere goats and Tan sheep were examined by assessing the abundance of OTUs. The results showed that a notable decrease in the Chao1 diversity index of the abomasum in goats (

p=0.04) (

Figure 3a). Additionally, principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) mapping revealed significant variations in the beta diversity of the abomasum and colon when comparing goats to sheep. (

Figure 3c&d). Those findings indicate that there are differences in the microbial composition and structure of the abomasum and colon in goats compared to sheep. Statistical analysis of the varying bacteria in the gut of goats and sheep identified 24 distinct bacteria in the abomasum and 21 in the colon. For example, in the abomasum, goats had a significant increase in the abundance of

Prevotella (

p=0.04),

Acetobacter (

p=0.03) and

UBA1711 (

p=0.02) in comparison to Tan sheep. Conversely, there was a notable decrease in the abundance of

Bifidobacterium_388775 (

p=0.03),

Eubacterium_Q (

p=0.01),

Succiniclasticum (

p=0.02) and

Saccharofermentans (

p=0.01). In the colon of goats, the abundance of

Phascolarctobacterium_A (

p=0.01),

Catonella (

p=0.01),

Porcincola (

p<0.001),

Treponema_F(p=0.04) were significantly lower than those in Tan sheep. It is worth noting that the abundance of

CAG−41 in the abomasum and colon of goats was significantly higher than those found in sheep (

p<0.05). In contrary,

CAG−273 was found in lower abundance in the abomasum of goats, but was more prevalent in their colon, indicating a specific distribution in these sites (Fig 4a&b). To assess the functional differences between goats and sheep, we conducted a phylogenetic analysis of communities by reconstructing unobserved states to identify the changes in functional profile. The results showed that the varying bacteria present in the abomasum and colon of Longdong cashmere goats exhibited a greater ability to metabolize lipids (Fig 4c&d).

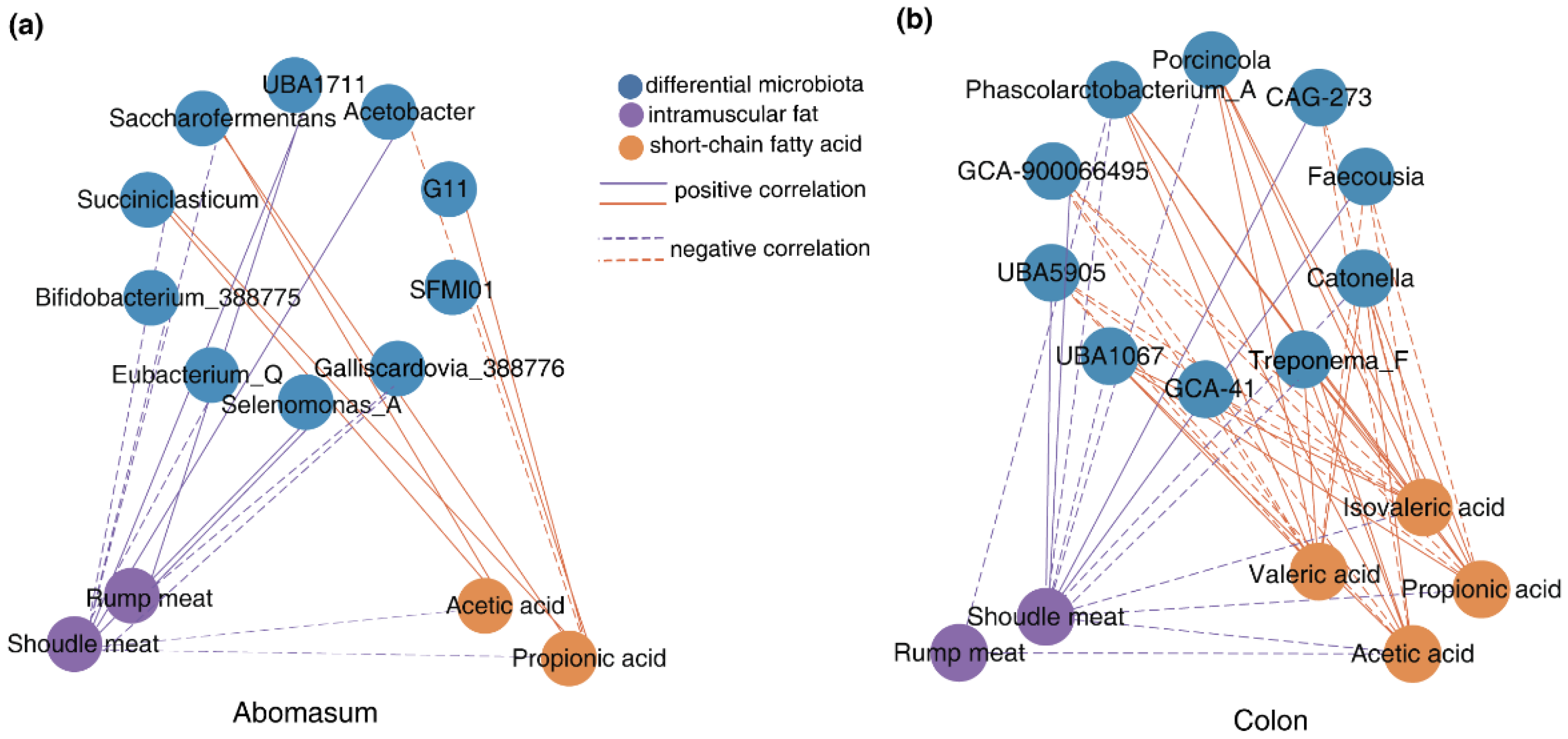

3.4. Association of Breeds-Related Bacteria with SCFAs and IMF Deposition

The Spearman correlation analysis demonstrated that Selenomonas_A in the abomasum was positively correlated with the IMF content in the shoulder and rump at a moderate to strong intensity (r>0.45, p<0.05). In contrast, Galliscardovia_388776 showed a negative correlation with this genus of bacteria (r<-0.45, p<0.05). Additionally, Bifidobacterium_388775 (r=-0.637, p<0.01) and Eubacterium_Q (r=-0.586, p<0.05) in the abomasum were both negatively associated with shoulder IMF content. Beyond the direct impacts of bacteria, their metabolic byproducts also influnced IMF deposition. Both Saccharofermentans and Succiniclasticum in the abomasum were positively correlated with the acetate and propionate content while negatively associated with shoulder IMF content (Fig.5a, |r|>0.45, p<0.05). Furthermore, UBA5905 and GCA-900066495 in the colon presented a negative correlation with SCFAs (acetic, propionic and isovaleric acid), but a positive association with shoulder IMF content. This trend was in contrast to that of Phascolarctobacterium_A, UBA1067, Treponema_F and Catonella. Faecousia, CAG−41 and CAG-273 were negatively correlated with isovaleric acid and positively related to shoulder IMF content (Fig.5b, |r|>0.45, p<0.05). Those findings suggest that some specific bacteria may modulate IMF deposition by altering their abundance within the microbial community or through their metabolic byproducts.

Figure 5.

Association of breeds-related bacteria with SCFAs contents and IMF deposition (a) Network of breeds-related bacteria in the abomasum with SCFAs contents and IMF deposition; (b) Network of breeds-related bacteria in the colon with SCFAs contents and IMF deposition. In these images, the solid line represents a significant positive correlation, while the dashed line represents a significant negative correlation. Only the results with moderate or strong correlations (Spearman r>0.45 or r<-0.45) and significant correlations (p< 0.05) based on Spearman rank were displayed.

Figure 5.

Association of breeds-related bacteria with SCFAs contents and IMF deposition (a) Network of breeds-related bacteria in the abomasum with SCFAs contents and IMF deposition; (b) Network of breeds-related bacteria in the colon with SCFAs contents and IMF deposition. In these images, the solid line represents a significant positive correlation, while the dashed line represents a significant negative correlation. Only the results with moderate or strong correlations (Spearman r>0.45 or r<-0.45) and significant correlations (p< 0.05) based on Spearman rank were displayed.

4. Discussion

The dressing percentage, GR value and IMF content are associated with the growth and fat deposition in animals, with variations observed across different breeds. Casey found that the dressing percentage of goats was lower than those in sheep, but their IMF content was higher [

8], which is generally consistent with our results. The levels of TG, TC, HDL, LDL and VDL in the serum are closely related to the lipid metabolism rate in the animal. Studies have shown that the serum levels of TC and TG were positively correlated with IMF content in the muscles [

26,

27]. This study revealed that the serum levels of TG, TC, FFA, HDL-C, LDL-C and VDL-C in Longdong cashmere goats were notably higher than those in Tan sheep, aligning with the observed IMF deposition. The findings of Hu et al. are basically in agreement with the results of this research [

28]. In addition, IMF deposition is also affected by a series of enzymes. FAS plays a key role in the de novo production of fatty acids, as it can catalyze the formation of fatty acids from malonyl-CoA, thus promoting fat synthesis[

29,

30].HSL is capable of breaking down fat into FFA and glycerol, with the FFA being carried through the bloodstream to provide energy to the body[

31,

32].Our research revealed that the content of FAS in the duodenum of Longdong Cashmere Goats was significantly lower, while the content of HSL in the pancreas and duodenum were notably higher. This shift may result in a greater flow of FFA to adipose tissue, leading to increased IMF deposition in muscle. These findings indicate that the lipid levels and the key enzymes related to lipid metabolism in the tissues and organs of Longdong cashmere goats have also been altered, which facilitates the IMF deposition.

Different animal breeds are linked to variations in fat metabolism and SCFAs, as well as differences in the composition and structure of the microbial community found in their gut chyme. In this research, we discovered that the amount of FAS present in the gut chyme was higher than that found in the liver. The content of HSL in the abomasal chyme of Longdong cashmere goats was significantly higher, whereas the content of FAS in the colonic chyme was notably lower. This suggests that the microbes present in the abomasum and colon could influence the metabolism of external lipid substances via enzymatic processes, thus playing a role in the regulation of IMF deposition. It is important to mention that the enzyme content we assessed in the gut chyme might include enzymes generated by the host. Moreover, there are variations in the contents of SCFAs found in the gut chyme of Longdong cashmere goats compared to Tan sheep. We obeserved that the contents of acetic acid and propionic acid in the abomasum and colon of goats were significantly lower than those of sheep. Acetic acid and propionic acid can enhance energy expenditure and decrese fat deposition by activating the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) [

33,

34]. Propionic acid can trigger the secretion of the appetite-suppressing hormone glucagon-like peptide-1 (Peptide YY) from the gastrointestinal tract, leading to a reduction in food consumption and, consequently, less fat accumulation [

35,

36].These reports are consistent with our observations that goats possess a lower SCFAs content in their gut chyme. . We also analyzed the microbial community diversity and found that the beta diversity of the abomasum and colon of goats differed from that of Tan sheep, with a significant reduction in the Chao1 index for the abomasum. Additionally, the analysis of distinct bacteria and functional pathways further validated that the unique bacteria in goats played a significant role in lipid metabolism progress.

The correlation analysis of breeds-related bacteria to metabolites and IMF content indicated that some differential bacteria may exhibit a moderate correlation with IMF content, either directly or indirectly. For example,

Bifidobacterium _ 387352,

Eubacterium_Q in the abomasum were directly negative related to shoulder IMF content. Studies have reported that

Bifidobacterium can significantly lower the levels of TG and TC in the serum and reduce fat deposition in mice [

37,

38,

39].

Bifidobacterium and

Bacteroides synergistically degrade polysaccharides, enhance the production and release insulin and glucagon-like peptide 1, inhibite the absorption of dietary lipids and cholesterol in the small intestine, and decrease fat deposition [

38,

40,

41].

Eubacterium-Q is capable of converting cholesterol into coprosterol, which helps to minimize fat buildup in the host and lower TC level in the serum and intestines [

42,

43]. In addition, we discovered that

Succiniclasticum,

Saccharofermentans,

Treponema_F and

Faecousia were associated with the production of acetic acid, propionic acid and isovaleric acid, as well as IMF deposition. Research data shows that Succiniclasticum has the ability to transform succinic acid into propionic acid and generate acetic acid [

44,

45,

46].

Saccharofermentans, a common starch-degrading bacterium, can degrade plant polysaccharides to generate acetates and propionates [

47,

48].

Treponema is capable of producing a majority of SCFAs, particularly acetic acid, propionic acid and butyric acid [

49,

50].Jiao et al. reported that acetate and propionate administration on pigs could reduce lipogenesis, and enhance lipolysis in different tissues via regulating related hormones and genes to prevent fat deposition in pigs [

51]. However, there is a scarcity of research studies regarding the impact of isovaleric acid on fat deposition. Our study offers valuable information about the influence of the gut microbiome on the IMF deposition in Longdong cashmere goats and Tan sheep, highlighting several potential microbes and metabolites. Nevertheless, we have not yet fully clarified how the bacteria affects the IMF deposition in goats. Moving forward, it is essential to validate the relationships we have identified between the gut microbiome and host characteristics by employing germ-free animal models that are colonized with cultured gut bacteria in controlled experimental settings.

5. Conclusions

Our research shows that Longdong cashmere goats possess a notably higher IMF content in their shoulder and rump meat, as well as greater lipid levels compared to Tan sheep. Additionally, these goats exhibit lower content of FAS and higher content of HSL in their digestive glands and contents, which benefit to the fat deposition. The identified variation bacteria found in goats and sheep were involved in lipid metabolism, especially the Selenomonas_A, Bifidobacterium_388775 and Eubacterium_Q in the abomasum, along with the UBA5905 and GCA-900066495 in the colon. Our findings highlight the crucial role of microbes in the abomasum and colon in IMF deposition in mutton and provide potential targets for improving meat quality and its market value.

Author Contributions

F.Z. and Y.L conceived and designed the research. J.H., B.S., Z.T. and J.W. contributed to the samples collection. L. Y. analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. S.L. and F.Z. revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version before submission.

Funding acquisition: This research was funded by Lanzhou Youth Science and Technology Talent Innovation Project (2023-QN-186), the Fuxi Young Talents Fund of Gansu Agricultural University (Gaufx-03Y04), Research Fund Project of Gansu Agricultural University (0722019) and the Discipline Team Project of Gansu Agricultural University (GAUXKTD-2022-21).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Gansu Agricultural University (protocol code GSAU-Eth-AST-2023-037).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw reads were deposited into the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database (Accession Number: PRJNA1214480).

Conflicts of Interest

We certify that there are no conflicts of interest with any financial organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.

References

- Kruk, Z. A.; Bottema, M. J.; Reyes-Veliz, L.; Forder, R. E. A.; Pitchford, W. S.; Bottema, C. D. K. , Vitamin A and marbling attributes: Intramuscular fat hyperplasia effects in cattle. Meat Sci 2018, 137, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troy, D. J.; Tiwari, B. K.; Joo, S. T. , Health Implications of Beef Intramuscular Fat Consumption. Korean journal for food science of animal resources 2016, 36(5), 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J. D.; Enser, M.; Fisher, A. V.; Nute, G. R.; Sheard, P. R.; Richardson, R. I.; Hughes, S. I.; Whittington, F. M. , Fat deposition, fatty acid composition and meat quality. A review. Meat Sci 2008, 78(4), 343–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Liao, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Ni, M. J. I. J. o. B. , Study on the Fat-related Genes of Chicken. International Journal of Biology 2009, 1(1), 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benet, I.; Guàrdia, M. D.; Ibañez, C.; Solà, J.; Arnau, J.; Roura, E. , Low intramuscular fat (but high in PUFA) content in cooked cured pork ham decreased Maillard reaction volatiles and pleasing aroma attributes. Food chemistry 2016, 196, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S. J.; Beak, S. H.; Jung, D. J. S.; Kim, S. Y.; Jeong, I. H.; Piao, M. Y.; Kang, H. J.; Fassah, D. M.; Na, S. W.; Yoo, S. P.; Baik, M. , Genetic, management, and nutritional factors affecting intramuscular fat deposition in beef cattle - A review. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci 2018, 31 (7), 1043-1061.

- Tshabalala, P. A.; Strydom, P. E.; Webb, E. C.; de Kock, H. L. , Meat quality of designated South African indigenous goat and sheep breeds. Meat Sci 2003, 65(1), 563–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, N. H. Carcass and growth characteristics of four South African sheep breeds and the Boer goat. Universiteit van Pretoria, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; Mou, H.; He, Y.; Zhang, D.; Pan, X.; Zhou, L.; Shen, Y.; E, G. , Effects of Key Rumen Bacteria and Microbial Metabolites on Fatty Acid Deposition in Goat Muscle. Animals: an open access journal from MDPI 2024, 14 (22).

- Zhao Xu, Z. X.; Ding Xiao, D. X.; Yang ZaiBin, Y. Z.; Shen YiRu, S. Y.; Zhang Shan, Z. S.; Shi ShouRong, S. S. , Effects of Clostridium butyricum on thigh muscle lipid metabolism of broilers. Italian Journal of Animal Science 2018, 17(4), 2018,17(4),1010–1020. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X.; Gou, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Li, L.; Lin, X.; Fan, Q.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, S. , Dietary fiber modulates abdominal fat deposition associated with cecal microbiota and metabolites in yellow chickens. Poultry science 2022, 101(4), 101721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, E. S.; Viardot, A.; Psichas, A.; Morrison, D. J.; Murphy, K. G.; Zac-Varghese, S. E.; MacDougall, K.; Preston, T.; Tedford, C.; Finlayson, G. S.; Blundell, J. E.; Bell, J. D.; Thomas, E. L.; Mt-Isa, S.; Ashby, D.; Gibson, G. R.; Kolida, S.; Dhillo, W. S.; Bloom, S. R.; Morley, W.; Clegg, S.; Frost, G. , Effects of targeted delivery of propionate to the human colon on appetite regulation, body weight maintenance and adiposity in overweight adults. Gut 2015, 64(11), 1744–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangerman, A.; Nagengast, F. M. , A gas chromatographic analysis of fecal short-chain fatty acids, using the direct injection method. Analytical biochemistry 1996, 236(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Smet, S.; Vossen, E. , Meat: The balance between nutrition and health. A review. Meat Sci 2016, 120, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babour, A.; Wei, J.; Luoa, Y. J. J. C. S. T. , Fatty Acid Composition of Muscles Tissues of Longdong Goat (Black and White Cashmere). 2018; 9, 2Journal of Chromatography & Separation Techniques. [Google Scholar]

- Schloss, P. D.; Jenior, M. L.; Koumpouras, C. C.; Westcott, S. L.; Highlander, S. K. , Sequencing 16S rRNA gene fragments using the PacBio SMRT DNA sequencing system. PeerJ 2016, 4, e1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Lin, J.; Pan, T.; Li, T.; Jiang, H.; Fang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, F.; Huang, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, D.; Chen, Y. , Polymeric immunoglobulin receptor deficiency exacerbates autoimmune hepatitis by inducing intestinal dysbiosis and barrier dysfunction. Cell death & disease, 2023; 14, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, D. V.; Madhusudanan, S.; Jaganathan, S. J. A. J. o. E.; Sciences, A. , uCLUST-a new algorithm for clustering unstructured data. ARPN Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences 2015, 10(5), 2108–2117. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, D.; Jiang, Y.; Balaban, M.; Cantrell, K.; Zhu, Q.; Gonzalez, A.; Morton, J. T.; Nicolaou, G.; Parks, D. H.; Karst, S. M.; Albertsen, M.; Hugenholtz, P.; DeSantis, T.; Song, S. J.; Bartko, A.; Havulinna, A. S.; Jousilahti, P.; Cheng, S.; Inouye, M.; Niiranen, T.; Jain, M.; Salomaa, V.; Lahti, L.; Mirarab, S.; Knight, R. , Greengenes2 unifies microbial data in a single reference tree. Nature biotechnology 2024, 42(5), 715–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, G. M.; Maffei, V. J.; Zaneveld, J. R.; Yurgel, S. N.; Brown, J. R.; Taylor, C. M.; Huttenhower, C.; Langille, M. G. I. , PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions. Nature biotechnology 2020, 38(6), 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloss, P. D.; Westcott, S. L.; Ryabin, T.; Hall, J. R.; Hartmann, M.; Hollister, E. B.; Lesniewski, R. A.; Oakley, B. B.; Parks, D. H.; Robinson, C. J.; Sahl, J. W.; Stres, B.; Thallinger, G. G.; Van Horn, D. J.; Weber, C. F. , Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Applied and environmental microbiology 2009, 75(23), 7537–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, N.; Mehrotra, D.; Bansal, A.; Bala, M. Thakur, N., Mehrotra, D., Bansal, A., Bala, M. (2019). Analysis and Implementation of the Bray–Curtis Distance-Based Similarity Measure for Retrieving Information from the Medical Repository. International Conference on Innovative Computing and Communications, 2019; 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Lozupone, C.; Lladser, M. E.; Knights, D.; Stombaugh, J.; Knight, R. , UniFrac: an effective distance metric for microbial community comparison. The ISME journal 2011, 5(2), 169–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Yang, Z.; Ji, H.; Li, N.; Yang, Z.; Xu, L.; Yang, H.; Wang, Z. , Effects of lycopene on abdominal fat deposition, serum lipids levels and hepatic lipid metabolism-related enzymes in broiler chickens. Animal bioscience 2021, 34(3), 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mersmann, H. J.; MacNeil, M. D. , Relationship of plasma lipid concentrations to fat deposition in pigs. Journal of animal science 1985, 61(1), 122–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Liao, K.; Wang, T.; Mai, K.; Xu, W.; Ai, Q. , Dietary Lipid Levels Influence Lipid Deposition in the Liver of Large Yellow Croaker (Larimichthys crocea) by Regulating Lipoprotein Receptors, Fatty Acid Uptake and Triacylglycerol Synthesis and Catabolism at the Transcriptional Level. PloS one 2015, 10(6), e0129937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, K.; Ye, P.; Yang, L.; Kuang, J.; Chen, X.; Geng, Z. J. A. B. , Comparison of slaughter performance, meat traits, serum lipid parameters and fat tissue between Chaohu ducks with high-and low-intramuscular fat content. Animal biotechnology 2020, 31(3), 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Zou, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Ma, J.; Shah, A. M.; Peng, Q.; Xue, B.; Wang, L.; Zhao, S.; Kong, X. , Dietary Energy Levels Affect Rumen Bacterial Populations that Influence the Intramuscular Fat Fatty Acids of Fattening Yaks (Bos grunniens). Animals : an open access journal from MDPI, 2020; 10, 9, 1474–1474. [Google Scholar]

- Mabrouk, G. M.; Helmy, I. M.; Thampy, K. G.; Wakil, S. J. , Acute hormonal control of acetyl-CoA carboxylase. The roles of insulin, glucagon, and epinephrine. The Journal of biological chemistry, 1990; 265, 11, 6330–6338. [Google Scholar]

- Menendez, J. A.; Lupu, R. , Fatty acid synthase-catalyzed de novo fatty acid biosynthesis: from anabolic-energy-storage pathway in normal tissues to jack-of-all-trades in cancer cells. Archivum immunologiae et therapiae experimentalis 2004, 52(6), 414–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lowe, M. E. , The triglyceride lipases of the pancreas. Journal of lipid research 2002, 43(12), 2007–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Wen, H.; Zeng, L.-B.; Jiang, M.; Wu, F.; Liu, W.; Yang, C.-G. J. A. , Changes in the activities and mRNA expression levels of lipoprotein lipase (LPL), hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) and fatty acid synthetase (FAS) of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) during fasting and re-feeding. Aquaculture 2013, 400, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Besten, G.; Bleeker, A.; Gerding, A.; van Eunen, K.; Havinga, R.; van Dijk, T. H.; Oosterveer, M. H.; Jonker, J. W.; Groen, A. K.; Reijngoud, D. J.; Bakker, B. M. , Short-Chain Fatty Acids Protect Against High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity via a PPARγ-Dependent Switch From Lipogenesis to Fat Oxidation. Diabetes 2015, 64(7), 2398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, H.; Guan, Y.; Li, X.; Lei, L.; Liu, J.; Yin, L.; Liu, G.; Wang, Z. , Acetic acid activates the AMP-activated protein kinase signaling pathway to regulate lipid metabolism in bovine hepatocytes. PloS one 2013, 8(7), e67880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H. V.; Frassetto, A.; Kowalik, E. J., Jr.; Nawrocki, A. R.; Lu, M. M.; Kosinski, J. R.; Hubert, J. A.; Szeto, D.; Yao, X.; Forrest, G.; Marsh, D. J. , Butyrate and propionate protect against diet-induced obesity and regulate gut hormones via free fatty acid receptor 3-independent mechanisms. PloS one 2012, 7(4), e35240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psichas, A.; Sleeth, M. L.; Murphy, K. G.; Brooks, L.; Bewick, G. A.; Hanyaloglu, A. C.; Ghatei, M. A.; Bloom, S. R.; Frost, G. , The short chain fatty acid propionate stimulates GLP-1 and PYY secretion via free fatty acid receptor 2 in rodents. International journal of obesity 2015, 39(3), 424–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y. N.; Yu, Q. F.; Fu, N.; Liu, X. W.; Lu, F. G. , Effects of four Bifidobacteria on obesity in high-fat diet induced rats. World journal of gastroenterology 2010, 16(27), 3394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Yoon, Y.; Park, J. H.; Park, J. W.; Noh, M. G.; Kim, H.; Park, C.; Kwon, H.; Park, J. H.; Kim, Y.; Sohn, J.; Park, S.; Kim, H.; Im, S. K.; Kim, Y.; Chung, H. Y.; Nam, M. H.; Kwon, J. Y.; Kim, I. Y.; Kim, Y. J.; Baek, J. H.; Kim, H. S.; Weinstock, G. M.; Cho, B.; Lee,C. ;Fang,S.;Park,H.;Seong, J. K., Bifidobacterial carbohydrate/nucleoside metabolism enhances oxidative phosphorylation in white adipose tissue to protect against diet-induced obesity. Microbiome 2022, 10(1), 188–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begley, M.; Hill, C.; Gahan, C. G. , Bile salt hydrolase activity in probiotics. Applied and environmental microbiology 2006, 72(3), 1729–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruta, H.; Fujii, Y.; Toyokawa, N.; Nakamura, S.; Yamashita, H. , Effects of Bifidobacterium-Fermented Milk on Obesity: Improved Lipid Metabolism through Suppression of Lipogenesis and Enhanced Muscle Metabolism. International journal of molecular sciences 2024, 25(18), 9934–9934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xia, Q.; Wu, T.; Shao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jin, N.; Tian, P.; Wu, L.; Lu, X. , Prophylactic treatment with Bacteroides uniformis and Bifidobacterium bifidum counteracts hepatic NK cell immune tolerance in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis induced by high fat diet. Gut microbes 2024, 16(1), 2302065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Lordan, C.; Ross, R. P.; Cotter, P. D. , Gut microbes from the phylogenetically diverse genus Eubacterium and their various contributions to gut health. Gut microbes 2020, 12(1), 1802866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Yu, M.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Meng, Q.; Majeed, U.; Jian, L.; Song, W.; Xue, W.; Luo, Y.; Yue, T. , Positive interactions among Corynebacterium glutamicum and keystone bacteria producing SCFAs benefited T2D mice to rebuild gut eubiosis. Food research international (Ottawa, Ont), 2023; 172, 113163. [Google Scholar]

- LI, W.-j.; Tao, M.; ZHANG, N.-f.; DENG, K.-d.; DIAO, Q.-y. J. J. o. I. A. , Dietary fat supplement affected energy and nitrogen metabolism efficiency and shifted rumen fermentation toward glucogenic propionate production via enrichment of Succiniclasticum in male twin lambs1. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. K.; Zhang, X. X.; Li, F. D.; Li, C.; Li, G. Z.; Zhang, D. Y.; Song, Q. Z.; Li, X. L.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, W. M. , Characterization of the rumen microbiota and its relationship with residual feed intake in sheep. Animal : an international journal of animal bioscience, 2021; 15, 100161. [Google Scholar]

- van Gylswyk, N. O. , Succiniclasticum ruminis gen. nov., sp. nov., a ruminal bacterium converting succinate to propionate as the sole energy-yielding mechanism. International journal of systematic bacteriology, 1995; 45, 297–300. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Hou, Y.; Yao, D.; Tian, J.; Jin, Y. , Rumen bacteria and meat fatty acid composition of Sunit sheep reared under different feeding regimens in China. Journal of the science of food and agriculture 2021, 101(3), 1100–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Liang, X.; He, X.; Li, J.; Tian, G.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y. , Compound enzyme preparation supplementation improves the production performance of goats by regulating rumen microbiota. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 2023, 107(23), 7287–7299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Peng, W.; Mao, K.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Wang, K.; Zeng, M.; Han, X.; Han, J.; Zhou, H. , The Changes in Fecal Bacterial Communities in Goats Offered Rumen-Protected Fat. Microorganisms 2024, 12(4), 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espiritu, H. M.; Valete, E. J. P.; Mamuad, L. L.; Jung, M.; Paik, M. J.; Lee, S. S.; Cho, Y. I. , Metabolic Footprint of Treponema phagedenis and Treponema pedis Reveals Potential Interaction Towards Community Succession and Pathogenesis in Bovine Digital Dermatitis. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland), 2024; 13, 9, 796. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, A.; Yu, B.; He, J.; Yu, J.; Zheng, P.; Luo, Y.; Luo, J.; Mao, X.; Chen, D. , Short chain fatty acids could prevent fat deposition in pigs via regulating related hormones and genes. Food & function, 2020; 11, 2, 1845–1855. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).