Submitted:

12 February 2025

Posted:

14 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The local equilibrium approximation (LEA) is a central assumption in many applications of non-equilibrium thermodynamics involving the transport of energy, mass, and momentum. However, assessing the validity of the LEA remains challenging due to the limited development of tools for characterizing non-equilibrium states compared to equilibrium states. To address this, we have developed a theory based on kinetic theory, which provides a nonlinear extension of the telegrapher’s equation commonly discussed in non-equilibrium frameworks that extend beyond the LEA. A key result of this theory is a steady-state diffusion equation that accounts for the constraint imposed by available thermal energy on the diffusion flux. The theory is suitable for analysis of steady-state composition profiles and can be used to quantify the deviation from local equilibrium. To validate the theory, we performed molecular dynamics simulations. The results show that deviation from local equilibrium can be systematically quantified, and for the diffusion process we have studied here, we have confirmed that the LEA remains accurate even under extreme concentration gradients in gas mixtures.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theory

2.1. Fick’s Law

2.2. Generalized Diffusion Equation

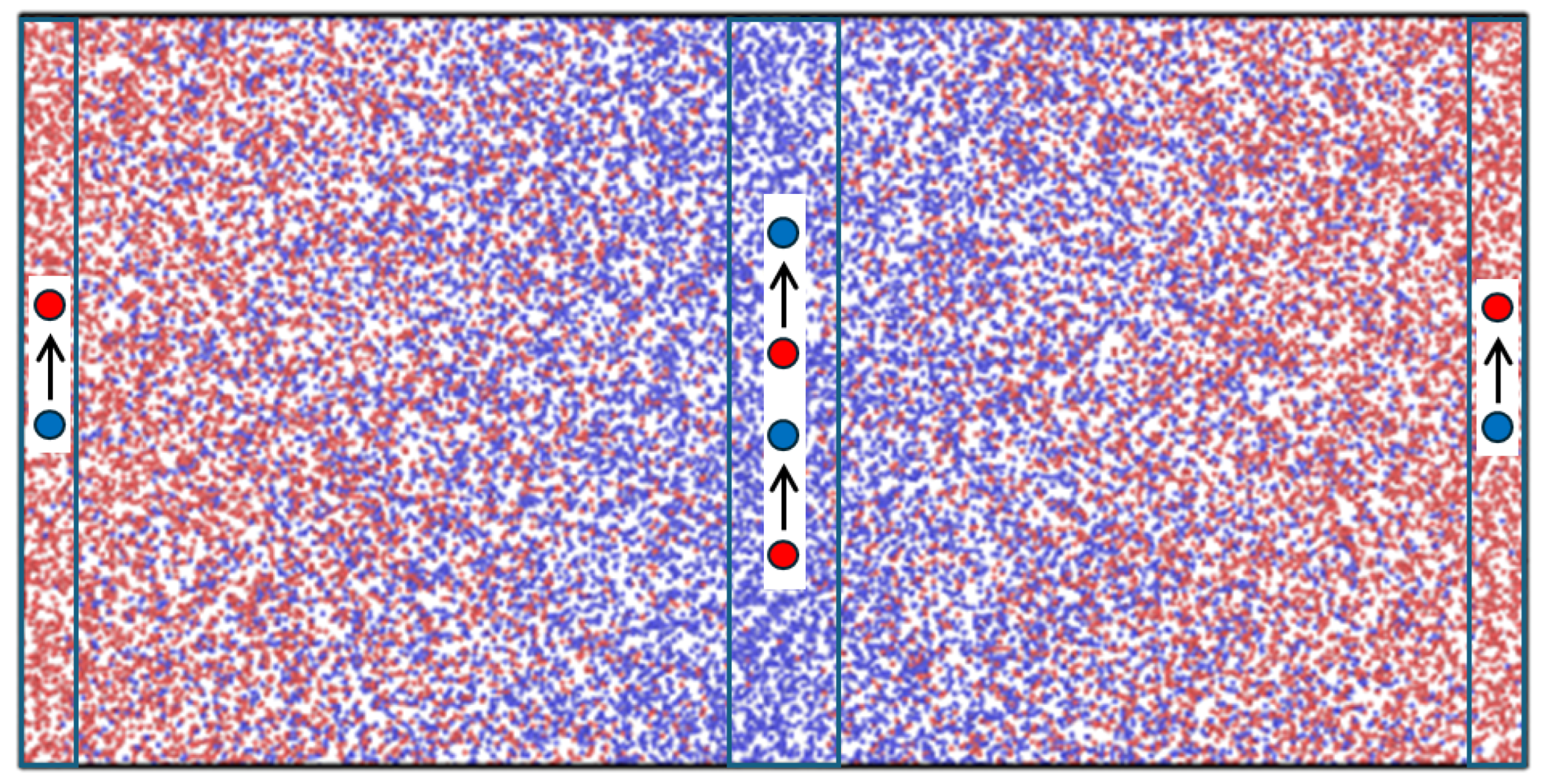

3. MD Simulations

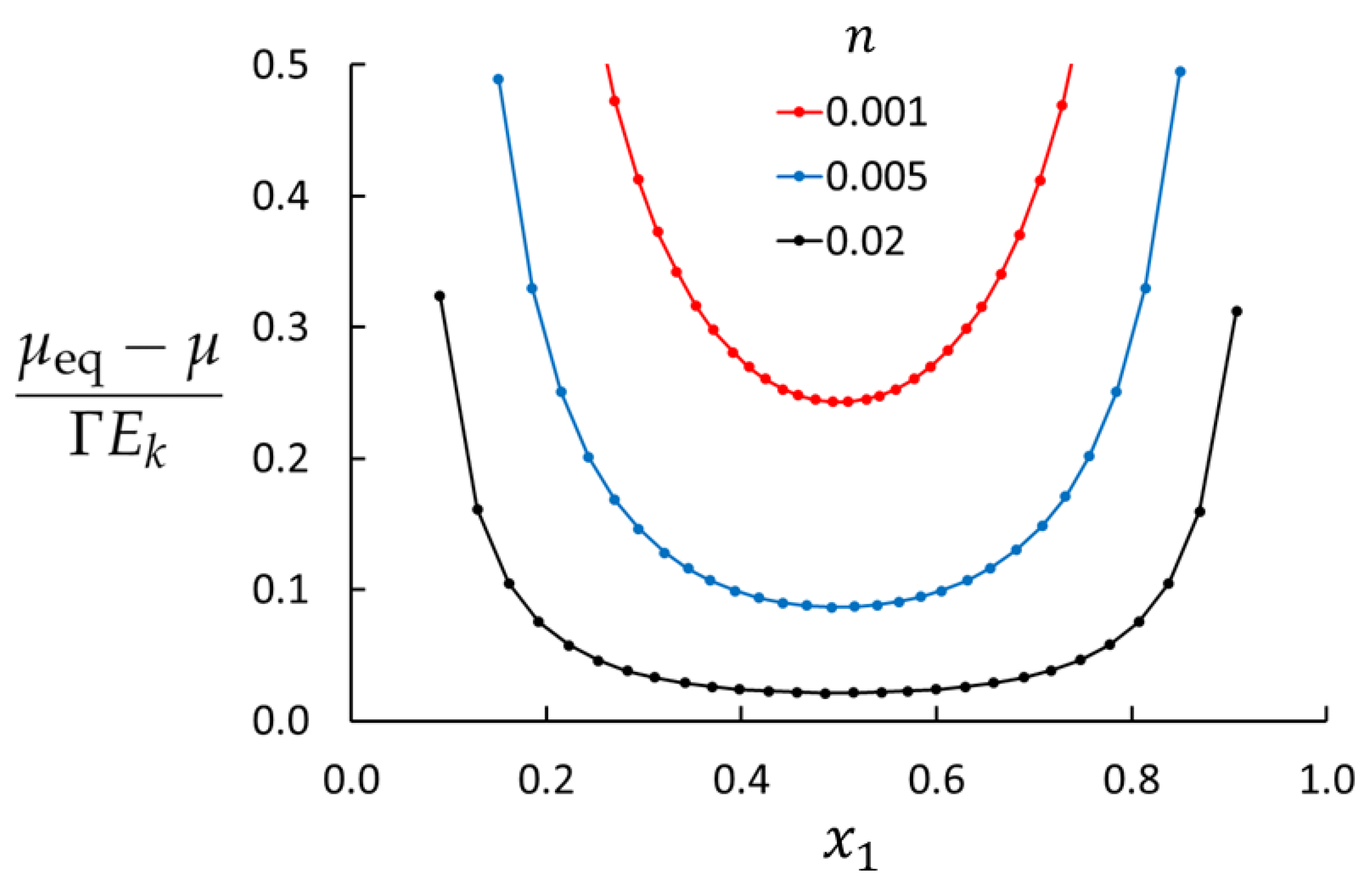

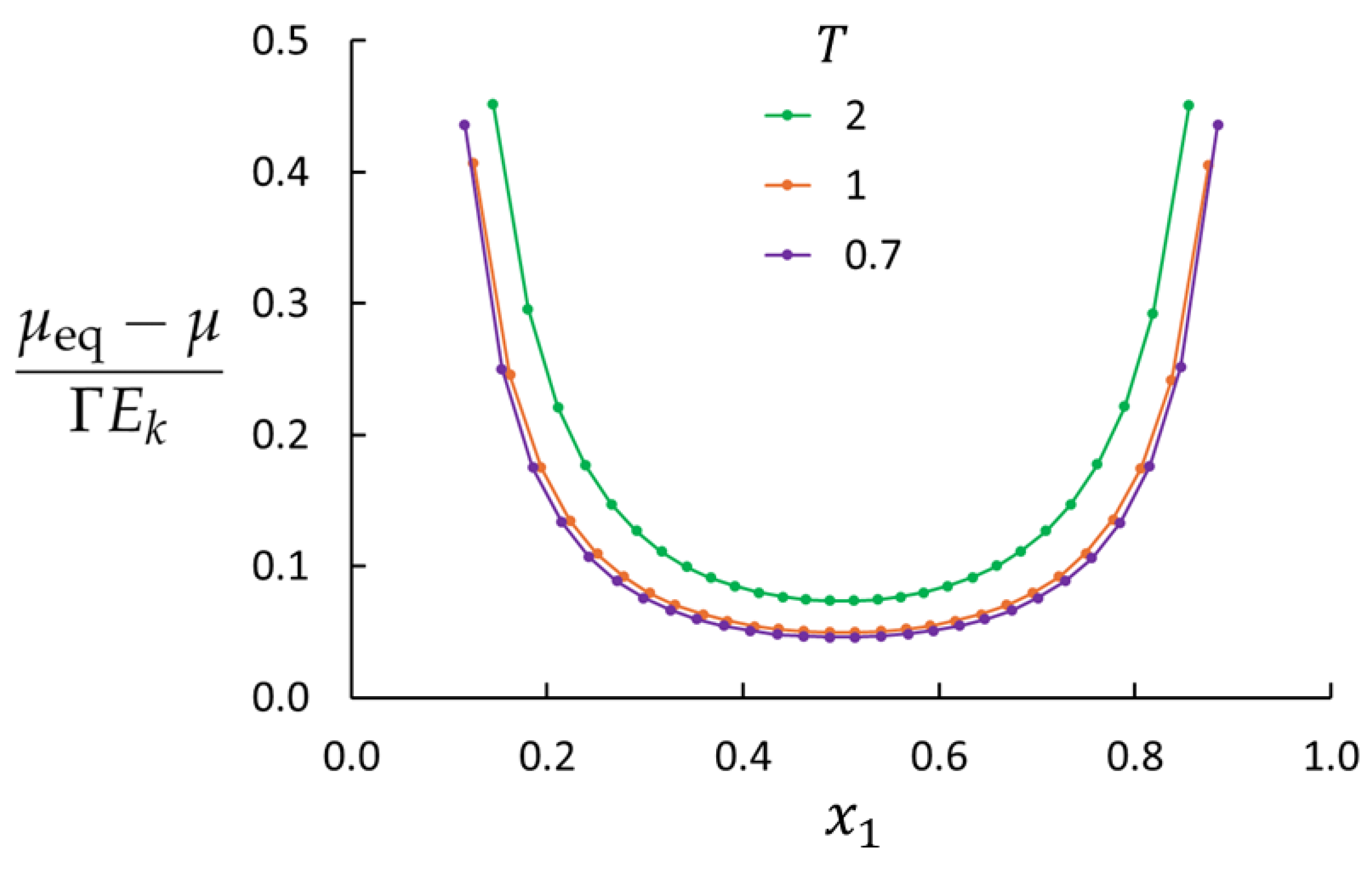

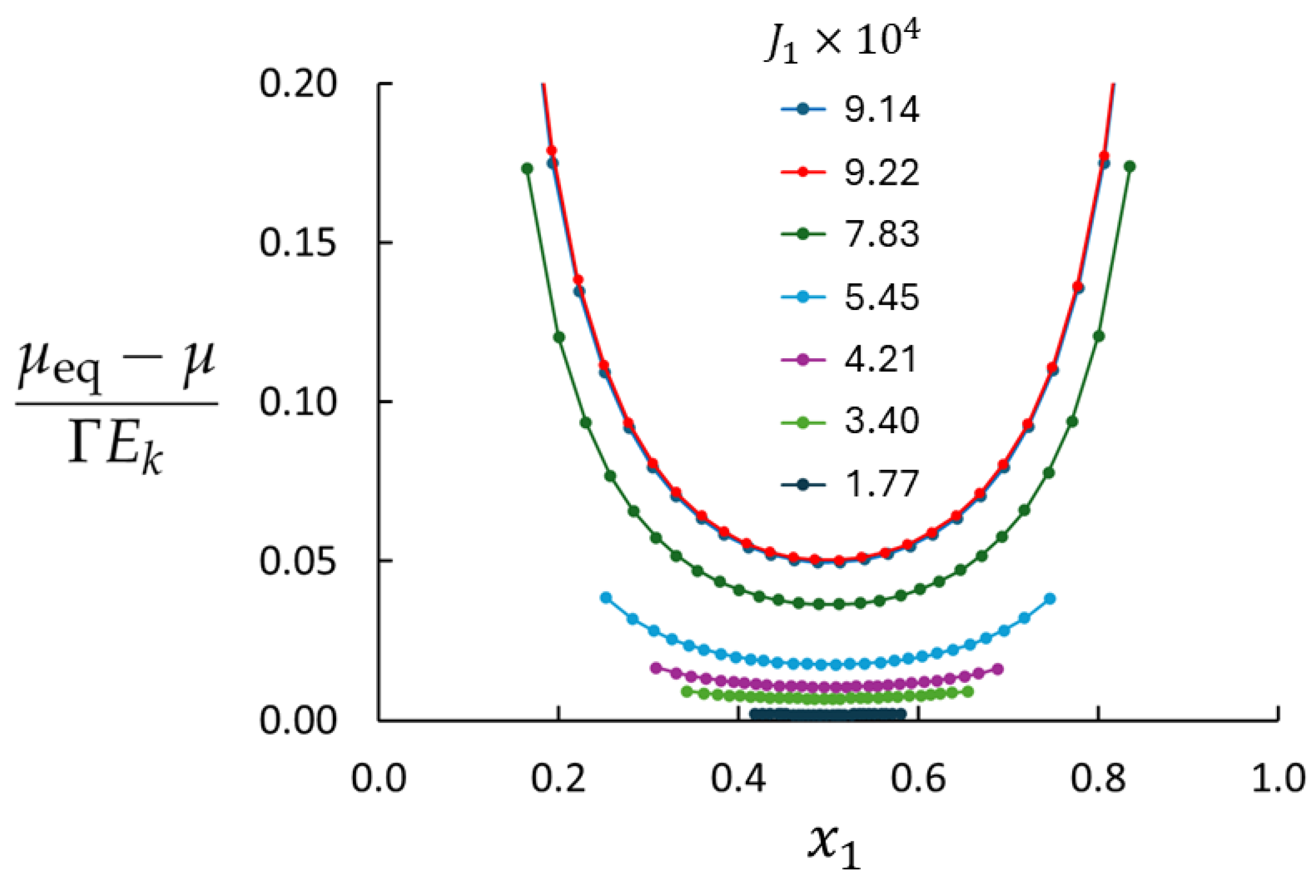

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kjelstrup, S.; Bedaux, D.; Johannessen, E.; Gross, J. Non-equilibrium Thermodynamics for Engineers; World Scientific Publishing, 2017; p. 156.

- Lieb, E.H.; Yngvason, J. The entropy concept for non-equilibrium states. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2013, 469, 20130408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafskjold, B.; Ratkje, S.K. Criteria for local equilibrium in a system with transport of heat and mass. Journal of Statistical Physics 1995, 78, 463–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimmelli, V.A.; Jou, D.; Ruggeri, T.; Ván, P. Entropy principle and recent results in non-equilibrium theories. Entropy 2014, 16, 1756–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattanzio, C.; Mascia, C.; Plaza, R.G.; Simeoni, C. Kinetic schemes for assessing stability of traveling fronts for the Allen–Cahn equation with relaxation. Applied Numerical Mathematics 2019, 141, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranovich, G.; Donohue, M. Limitations and generalizations of the classical phenomenological model for diffusion in fluids. Molecular physics 2007, 105, 1085–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell, F.M.; Aranow, R.; Spangler, R.A. Statistical-Mechanical Derivation of the Partial Molecular Stress Tensors in Isothermal Multicomponent Systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1967, 47, 4959–4971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jou, D.; Casas-Vázquez, J.; Lebon, G. Extended Irreversible Thermodynamics; Springer, 2010.

- de Groot, S.R.; Mazur, P. Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics; Dover Publications, 1984.

- Hafskjold, B.; Travis, K.P.; Hass, A.B.; Hammer, M.; Aasen, A.; Wilhelmsen, Ø. Thermodynamic properties of the 3D Lennard-Jones/spline model. Molecular Physics 2019, 117, 3754–3769. [CrossRef]

- Darken, L.S. Diffusion, mobility and their interrelation through free energy in binary metallic systems. Trans AIME 1948, 175, 184–194. [Google Scholar]

- Hafskjold, B.; Ikeshoji, T.; Ratkje, S.K. On the molecular mechanism of thermal diffusion in liquids. Molecular Physics 1993, 80, 1389–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Westen, T.; Hammer, M.; Hafskjold, B.; Aasen, A.; Gross, J.; Wilhelmsen, Ø. Perturbation theories for fluids with short-ranged attractive forces: A case study of the Lennard-Jones spline fluid. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2022, 156. [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, F. Self-diffusion in argon. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1949, 17, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Here, we use the flux of particles and the number density instead of the usual molar flux and molar concentration. |

| Case | n | T | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.001 | 0.7 | 254 | 225 |

| 2 | 0.005 | 0.7 | 148 | 45.0 |

| 3 | 0.01 | 0.7 | 118 | 22.5 |

| 4 | 0.01 | 1.0 | 118 | 22.5 |

| 5 | 0.01 | 2.0 | 118 | 22.5 |

| 6 | 0.02 | 0.7 | 94 | 11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).