1. Introduction

Podoplanin (PDPN) (also known as T1α, PA2.26 antigen, E11 antigen, and Aggrus) is a type I transmembrane protein that has a highly glycosylated extracellular domain, a transmembrane domain, and a short intracellular domain [

1,

2]. PDPN expression is observed in normal tissue and cells, including lung type I alveolar epithelial cells [

3,

4], kidney podocytes [

5], and lymphatic endothelial cells [

6,

7]. Mice lacking PDPN exhibited the lethal phenotype at birth due to respiratory defects and failure in the lymphatic vessel formation [

8]. These results indicate the importance of PDPN in lung and lymphatic development.

The roles of PDPN have been studied in tumors, including malignant gliomas, mesotheliomas, and head and neck squamous cell carcinomas, and esophageal carcinoma [

2]. The overexpression of PDPN is associated with poor clinical outcomes [

2]. Moreover, PDPN expression is detected in cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), which constitute a significant part of the tumor microenvironment (TME) [

9]. CAFs have been shown to promote cancer cell survival and influence therapeutic outcomes [

9]. Additionally, they contribute to the development of an immunosuppressive TME, thereby diminishing antitumor immunity [

10]. Increased PDPN staining in CAFs has been associated with poor prognosis in patients with lung [11-13], breast [

14], and pancreatic cancer [

15]. Consequently, PDPN is a valuable diagnostic marker and a promising therapeutic target for tumors.

Majestic rhinoceroses once thrived across Africa, Asia, and Europe. Still, today, they are classified as threatened or endangered due to the decline of population driven by the illegal trade of their horns [

16]. Although conservation initiatives have succeeded in boosting the number of rhinoceros in the wild, specific populations, such as those with infectious diseases, remain at risk. The white rhinoceros (

Ceratotherium simum) and the black rhinoceros (

Diceros bicornis) have recently been found to carry bovine tuberculosis (bTB), a bacterial infection caused by

Mycobacterium bovis (M. bovis), within conservation areas [

17,

18]. The full extent and health impact of

M. bovis infections in wild rhinoceroses remain uncertain, and bTB has been identified as an "underrecognized threat" to their conservation [

19]. The prevalence, distribution, and risk factors of

M. bovis infections in rhinoceroses were reported in Kruger National Park, which harbors the world’s largest free-ranging rhinoceros population [

20]. However, there is a limitation of the pathological analysis owing to the lack of antibodies that can recognize the antigens of the rhinoceros and distinguish the specific types of cells in tissues.

The Cell-Based Immunization and Screening (CBIS) method includes immunizing antigen-overexpressed cells and high throughput hybridoma screening using flow cytometry. Using the CBIS method, a variety of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that recognize linear epitope [

21], structural epitope [

22], and glycosylated epitope [

23] of membrane protein have been established. Our group has developed anti-PDPN mAbs against over 20 species (

http://www.med-tohoku-antibody.com/topics/001_paper_antibody_PDIS.htm#PDPN). These mAbs contribute not only to the research of each animal but also to diagnosis [

24] and drug development [

25]. This study aimed to develop anti-rhinoceros PDPN (rhiPDPN) mAbs using the CBIS method.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines and Plasmids

Synthesized DNA encoding rhiPDPN (XM_058552942, Eurofins Genomics KK, Tokyo, Japan) plus an N-terminal MAP16 tag (PGTGDGMVPPGIEDKI) [

26] and an N-terminal PA16 tag (GLEGGVAMPGAEDDVV) [

27], which are recognized by an anti-MAP tag mAb (PMab-1) [

28] and an anti-PA tag mAb (NZ-1) [

29], were subcloned into a pCAGzeo vector [FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation (Wako), Osaka, Japan]. Afterward, plasmids were transfected into Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-K1 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) using the Neon transfection system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA). Stable transfectants (CHO/MAP16-rhiPDPN and CHO/PA16-rhiPDPN) were subsequently selected using a cell sorter (SH800, Sony Corp., Tokyo, Japan) using PMab-1 and NZ-1, respectively.

2.2. Production of Hybridomas

For developing anti-rhiPDPN mAbs, 6-week-old female BALB/cAJcl mice (CLEA Japan, Tokyo, Japan) were immunized intraperitoneally with 1 × 10

8 cells/mouse of CHO/MAP16-rhiPDPN. Alhydrogel adjuvant 2% (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA) was added as an adjuvant in the first immunization. Three additional injections of 1 × 10

8 cells/mouse of CHO/MAP16-rhiPDPN were administered intraperitoneally without an adjuvant addition every week. A final booster injection was performed with 1 × 10

8 cells/mouse of CHO/MAP16-rhiPDPN intraperitoneally two days before harvesting splenocytes from mice. We conducted cell-fusion of the harvested splenocytes from CHO/MAP16-rhiPDPN-immunized mice with P3X63Ag8U.1 (P3U1, ATCC) cells using polyethylene glycol 1500 (PEG1500; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) under heated conditions. Hybridomas were cultured as described previously [

21].

2.3. Flow Cytometric Analysis

Cells were collected after a brief treatment with 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA; Nacalai Tesque, Inc.). Afterward, they were rinsed with a blocking buffer of 0.1% BSA in PBS and incubated with varying concentrations (0.001, 0.01, 0.1, and 1 µg/mL) of PMab-315 and PMab-324 for 30 minutes at 4°C. Subsequently, the cells were exposed to Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG diluted to 1:2,000. Fluorescence measurements were then obtained using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer (Sony Corp.).

2.4. Determination of Dissociation Constant (KD) by Flow Cytometry

CHO/PA16-rhiPDPN cells were incubated in a series of diluted PMab-315 and PMab-324 solutions for 30 minutes at 4°C. Then, the cells were treated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG at a dilution 1:200. The

KD was determined as described previously [

21].

2.5. Western Blot Analysis

Cell lysates were prepared, electrophoresed, and transferred onto the membrane as described previously [

21]. The membranes were incubated with 5 μg/mL of PMab-315, 5 μg/mL of PMab-324, 0.5 μg/mL of NZ-1, or 1 μg/mL of an anti-isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 mAb (RcMab-1), followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:2,000; Agilent Technologies Inc.) or anti-rat IgG (1:10,000; Merck KGaA). Chemiluminescence signals were developed as described previously [

21].

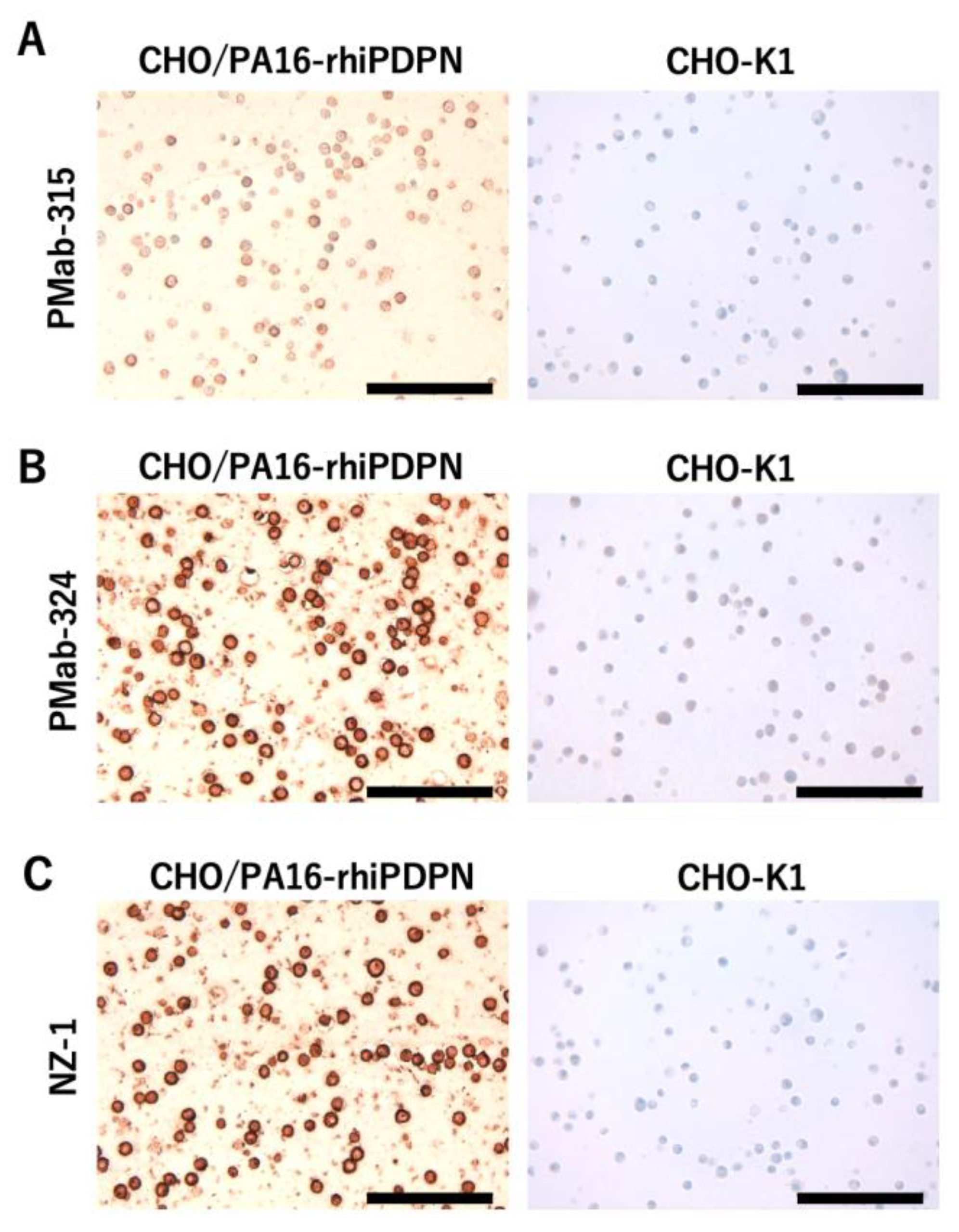

2.6. Immunohistochemical Analysis

CHO-K1 and CHO/PA16-rhiPDPN cell blocks were prepared using iPGell (Genostaff Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The paraffin-embedded cell sections were autoclaved in a citrate buffer (pH 6.0; Nichirei Biosciences, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). After blocking, the sections were incubated with 5 μg/mL of PMab-315, 5 μg/mL of PMab-324, or 1 μg/mL of NZ-1, and then treated with the Envision+ Kit (for PMab-315 and PMab-324, Agilent Technologies Inc.) or Histofine Simple Stain Mouse MAX PO (Rat) (for NZ-1, Nichirei Biosciences, Inc.). Color was developed using 3,3’-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Agilent Technologies Inc.), and counterstaining was performed using hematoxylin (Merck KGaA).

3. Results

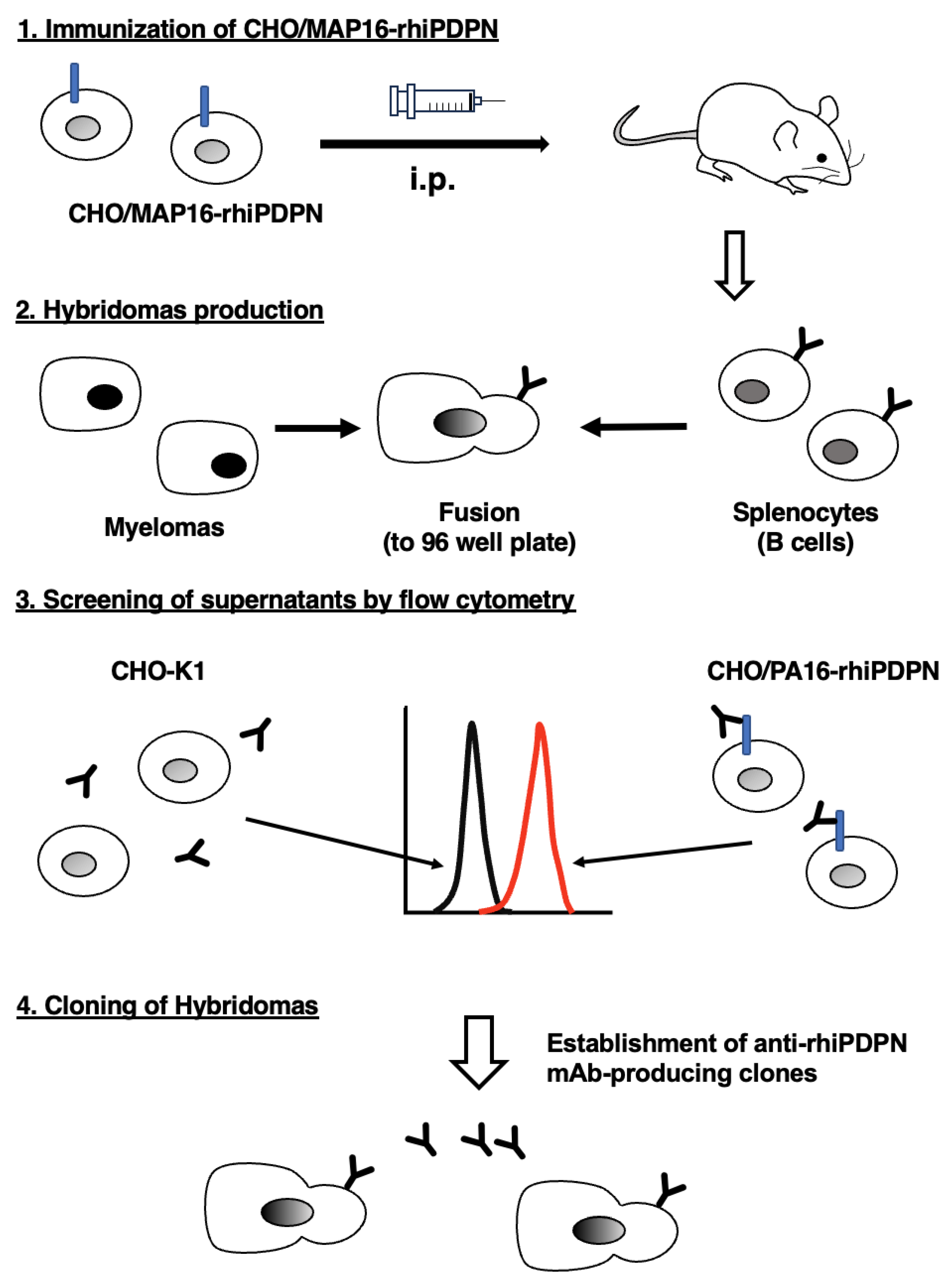

3.1. Development of Anti-rhiPDPN mAbs Using the CBIS Method

To generate anti-rhiPDPN mAbs, two mice were immunized with CHO/MAP16-rhiPDPN (

Figure 1A). Following immunization, the spleen was excised from the mice, and the splenocytes were fused with myeloma P3U1 cells (

Figure 1B). The resulting hybridomas were then plated into ten 96-well plates and cultured for six days. Subsequently, supernatants that were reactive to CHO/PA16-rhiPDPN and non-reactive to CHO-K1 were selected from 958 wells via flow cytometry (

Figure 1C). After conducting limiting dilution and several additional screenings, a clone, PMab-315 (mouse IgG

2a, kappa) was successfully established (

Figure 1D). Furthermore, we conducted another series of immunization and screening as mentioned above. Another clone PMab-324 (mouse IgG

2b, kappa) was successfully cloned.

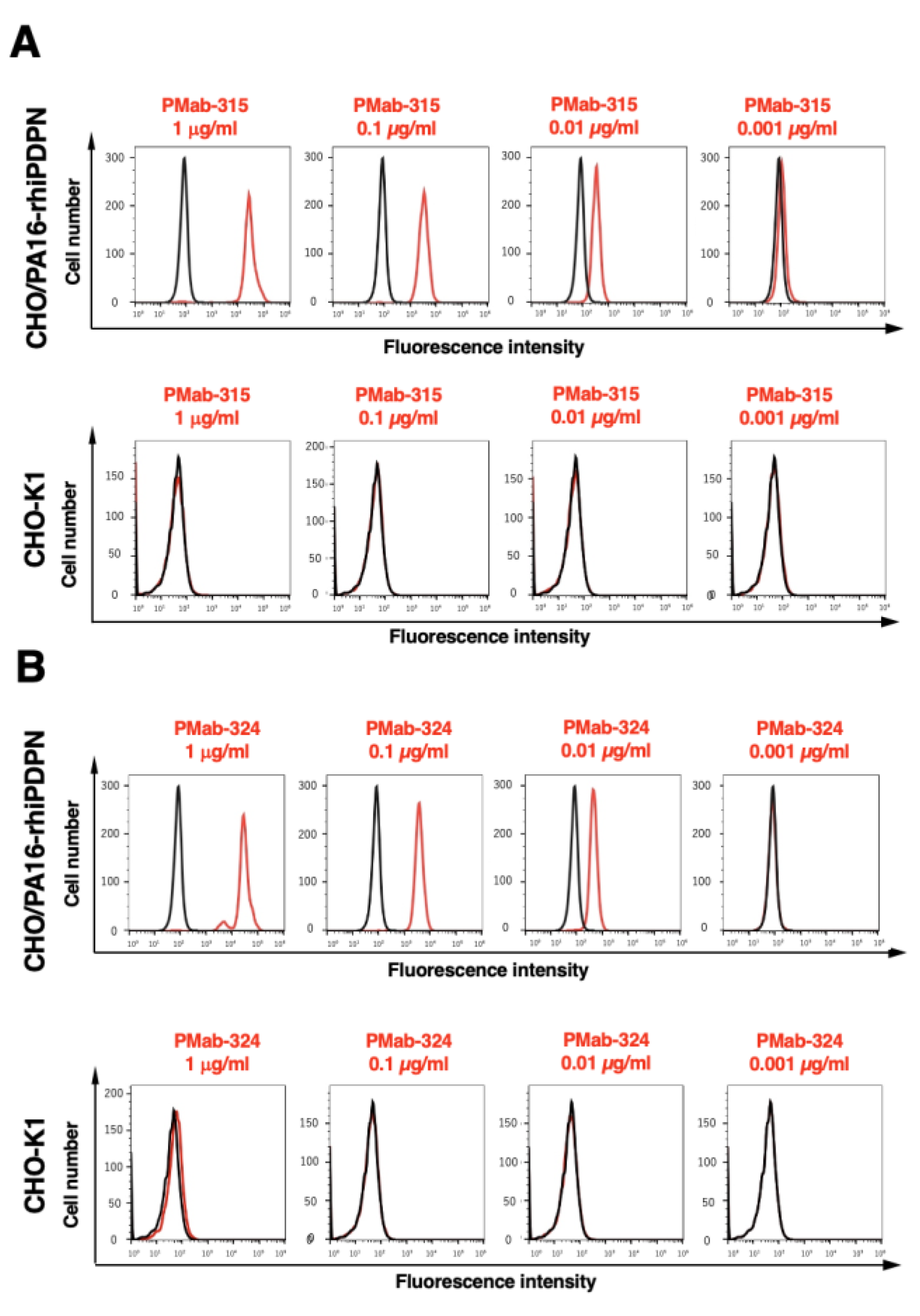

3.2. Flow Cytometry Using PMab-315 and PMab-324

We conducted flow cytometry using PMab-315 and PMab-324 against CHO/PA16-rhiPDPN and CHO-K1 cells. PMab-315 and PMab-324 showed similar reactivity to CHO/PA16-rhiPDPN cells (

Figure 2A,B) from 0.001 to 1 μg/mL. However, PMab-315 did not recognize parental CHO-K1 cells even at 1 μg/mL (

Figure 2A), and PMab-324 showed faint reactivity to CHO-K1 cells at 1 μg/mL (

Figure 2B).

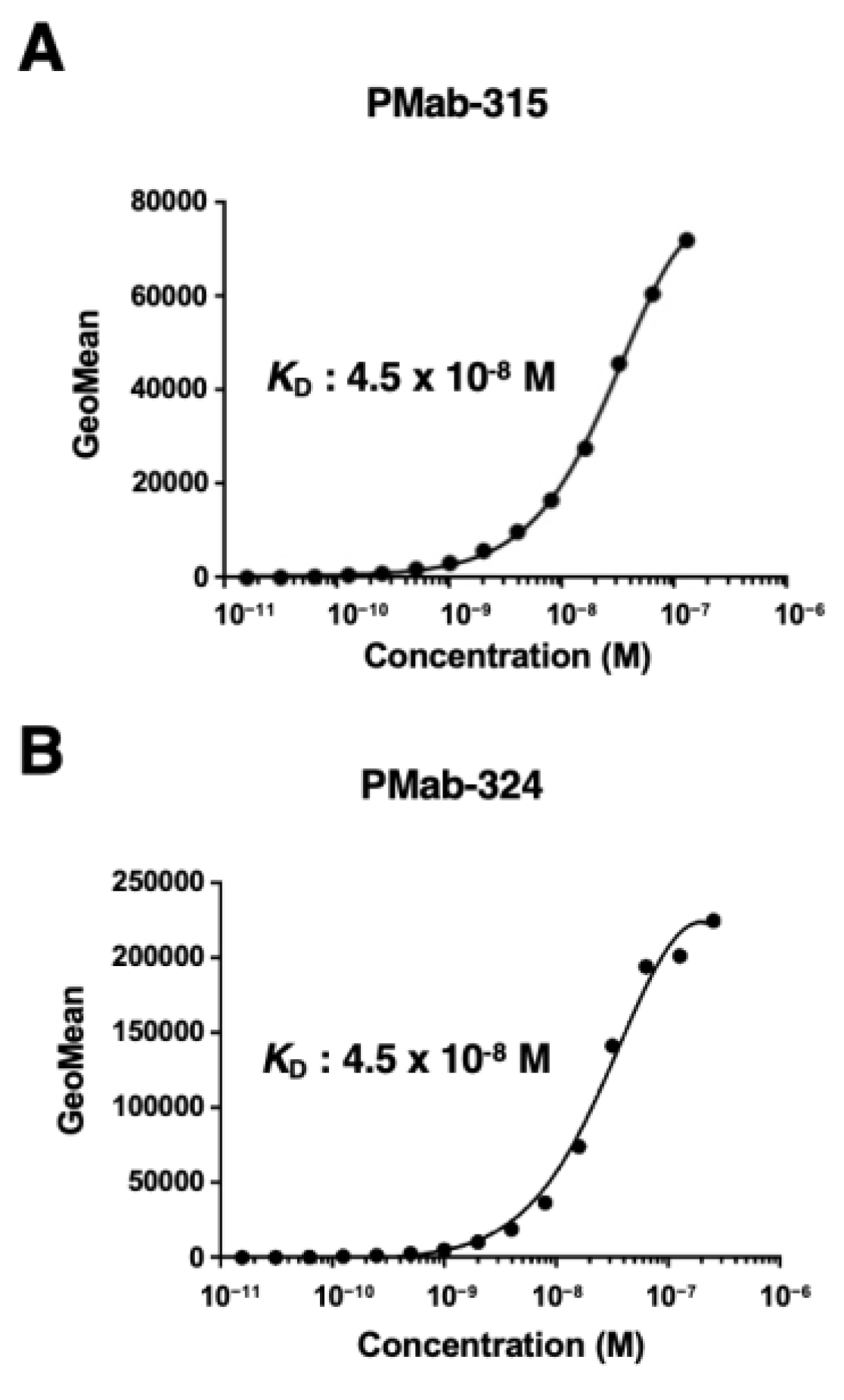

3.3. The Binding Affinity of PMab-315 and PMab-324

We conducted flow cytometry to determine the

KD values of PMab-315 and PMab-324 against CHO/PA16-rhiPDPN. PMab-315 and PMab-324 showed the same

KD value (4.5 × 10

−8 M) (

Figure 3).

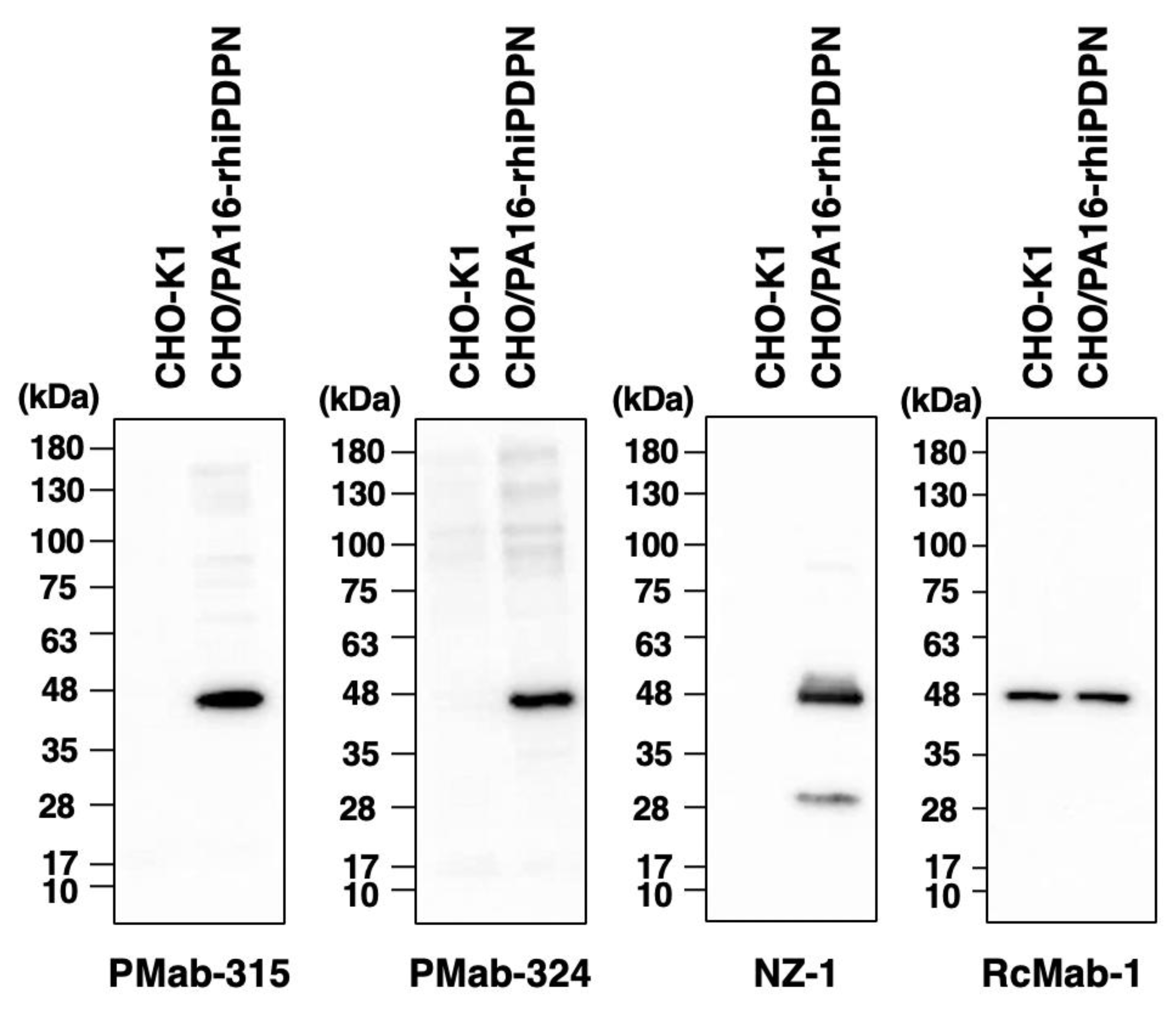

3.4. Western Blot Analysis Using PMab-315 and PMab-324

We investigated whether PMab-315 and PMab-324 can be used for western blot analysis using CHO-K1 and CHO/PA16-rhiPDPN cell lysates. As shown in

Figure 4, PMab-315 and PMab-324 could detect rhiPDPN as the significant band around 48 kDa in CHO/PA16-rhiPDPN cell lysates, while no band was detected in parental CHO-K1 cells. An anti-PA tag mAb, NZ-1, could detect rhiPDPN as the band around 48 kDa in CHO/PA16-rhiPDPN cell lysates. An anti-isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 mAb (clone RcMab-1) was used for internal control. These results indicate that PMab-315 and PMab-324 can detect rhiPDPN in western blot analysis.

3.5. Immunohistochemistry Using PMab-315 and PMab-324

To investigate whether PMab-315 and PMab-324 can be used for immunohistochemistry, paraffin-embedded CHO-K1 and CHO/PA16-rhiPDPN sections were stained with PMab-315, PMab-324, or NZ-1. PMab-315 showed a membranous staining in CHO/PA16-rhiPDPN, but not in CHO-K1 (

Figure 5A). Furthermore, more potent membranous staining by PMab-324 was observed in CHO/PA16-rhiPDPN (

Figure 5B). A weak reactivity to CHO-K1 was observed by PMab-324 (

Figure 5B). An anti-PA tag mAb, NZ-1 showed potent membranous staining in CHO/PA16-rhiPDPN, but not in CHO-K1 (

Figure 5C). These results indicate that PMab-315 and PMab-324 can apply to IHC for detecting rhiPDPN-positive cells in paraffin-embedded cell samples.

4. Discussion

In this study, we developed novel anti-rhiPDPN mAbs, PMab-315 and PMab-324, using the CBIS method (

Figure 1) from two independent screening. PMab-315 and PMab-324 showed the usefulness of flow cytometry (

Figure 2) and possess moderate affinities (4.5 × 10

−8 M) against CHO/PA16-rhiPDPN (

Figure 3). Furthermore, PMab-315 and PMab-324 can detect rhiPDPN in western blot (

Figure 4) and immunohistochemistry (

Figure 5) using a paraffin-embedded cell block. Therefore, PMab-315 and PMab-324 are expected to identify endogenous rhiPDPN-positive cells, such as lung type I alveolar epithelial cells, kidney podocytes, and lymphatic endothelial cells.

As a generalist pathogen,

M. bovis can infect a broad range of domestic and wild host species [

30,

31]. bTB is endemic among rhinoceros populations as well as other domestic and wild hosts Kruger National Park [

32]. Disease susceptibility and progression seem to vary between species, resulting in different levels of clinical symptoms [

31]. Previous studies in zoological settings have indicated that rhinoceroses are susceptible to tuberculosis [

33]. However, histopathological analysis has not been reported in the affected organs. PMab-315 and PMab-324 will help in the pathological analysis of rhinoceros tissues in future studies.

Rhinoceroses are known for their thick skin, often called dermal armor. The structure has a dense and cornified epidermis and a dermis with high tensile strength [

34]. A histological study of white rhinoceros integument was reported [

35]. The hematoxylin & eosin and elastic staining revealed that the stratum corneum was present in more than half of the epidermal thickness. The epidermal-dermal junction featured numerous papillary folds, enhancing the surface contact between the integumentary layers. Most dermis were composed of well-organized collagen bundles interspersed with elastic fibers. The superficial layer of the dermis was richly vascularized, with capillaries, arterioles, and venules densely concentrated just beneath the epidermis. Small arteries and veins were present in the middle layer of the dermis. Only a few large vessels were observed in the deepest layers of the dermis. Since PDPN is highly expressed in lymphatic endothelial cells, PMab-315 and PMab-324 would contribute to identifying lymphatic vessels from the capillaries and analyzing rhinoceros diseases such as cancer.

Author Contributions

Shiori Fujisawa: Investigation, Writing – original draft; Rena Ubukata: Investigation. Hiroyuki Suzuki: Investigation, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft. Tomohiro Tanaka: Investigation, Funding acquisition. Airi Nomura: Investigation. Keisuke Shinoda: Investigation. Takuya Nakamura: Investigation. Guanjie Li: Investigation. Hiroyuki Satofuka: Investigation, Funding acquisition. Mika K. Kaneko: Conceptualization. Yukinari Kato: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under Grant Numbers: JP24am0521010 (to Y.K.), JP24ama121008 (to Y.K.), JP24ama221339 (to Y.K.), JP24bm1123027 (to Y.K.), and JP24ck0106730 (to Y.K.), and by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) grant nos. 22K06995 (to H.Suzuki), 24K11652 (to H.Satofuka), 24K18268 (to T.T), and 22K07224 (to Y.K.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Tohoku University (Permit number: 2022MdA-001) for studies involving animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All related data and methods are presented in this paper. Additional inquiries should be addressed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest involving this article.

References

- Kato, Y.; Fujita, N.; Kunita, A.; et al. Molecular identification of Aggrus/T1alpha as a platelet aggregation-inducing factor expressed in colorectal tumors. J Biol Chem 2003;278(51): 51599-51605. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Roles of Podoplanin in Malignant Progression of Tumor. Cells 2022;11(3). [CrossRef]

- Dobbs, L.G.; Williams, M.C.; Gonzalez, R. Monoclonal antibodies specific to apical surfaces of rat alveolar type I cells bind to surfaces of cultured, but not freshly isolated, type II cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1988;970(2): 146-156. [CrossRef]

- Rishi, A.K.; Joyce-Brady, M.; Fisher, J.; et al. Cloning, characterization, and development expression of a rat lung alveolar type I cell gene in embryonic endodermal and neural derivatives. Dev Biol 1995;167(1): 294-306.

- Breiteneder-Geleff, S.; Matsui, K.; Soleiman, A.; et al. Podoplanin, novel 43-kd membrane protein of glomerular epithelial cells, is down-regulated in puromycin nephrosis. Am J Pathol 1997;151(4): 1141-1152.

- Hirakawa, S.; Hong, Y.K.; Harvey, N.; et al. Identification of vascular lineage-specific genes by transcriptional profiling of isolated blood vascular and lymphatic endothelial cells. Am J Pathol 2003;162(2): 575-586. [CrossRef]

- Petrova, T.V.; Mäkinen, T.; Mäkelä, T.P.; et al. Lymphatic endothelial reprogramming of vascular endothelial cells by the Prox-1 homeobox transcription factor. Embo j 2002;21(17): 4593-4599. [CrossRef]

- Schacht, V.; Ramirez, M.I.; Hong, Y.K.; et al. T1alpha/podoplanin deficiency disrupts normal lymphatic vasculature formation and causes lymphedema. Embo j 2003;22(14): 3546-3556.

- Asif, P.J.; Longobardi, C.; Hahne, M.; Medema, J.P. The Role of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in Cancer Invasion and Metastasis. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13(18). [CrossRef]

- Sakai, T.; Aokage, K.; Neri, S.; et al. Link between tumor-promoting fibrous microenvironment and an immunosuppressive microenvironment in stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer 2018;126: 64-71. [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, A.; Ishii, G.; Ito, T.; et al. Podoplanin-positive fibroblasts enhance lung adenocarcinoma tumor formation: podoplanin in fibroblast functions for tumor progression. Cancer Res 2011;71(14): 4769-4779. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K.; Sugai, T.; Ishida, K.; et al. Analysis of cancer-associated fibroblasts and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cutaneous basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma. Hum Pathol 2018;79: 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, J.; Aokage, K.; Neri, S.; et al. Relationship between podoplanin-expressing cancer-associated fibroblasts and the immune microenvironment of early lung squamous cell carcinoma. Lung Cancer 2021;153: 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Pula, B.; Jethon, A.; Piotrowska, A.; et al. Podoplanin expression by cancer-associated fibroblasts predicts poor outcome in invasive ductal breast carcinoma. Histopathology 2011;59(6): 1249-1260. [CrossRef]

- Shindo, K.; Aishima, S.; Ohuchida, K.; et al. Podoplanin expression in cancer-associated fibroblasts enhances tumor progression of invasive ductal carcinoma of the pancreas. Mol Cancer 2013;12(1): 168. [CrossRef]

- Kamath, P.L. Conserving rhinoceros in the face of disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022;119(25): e2206438119.

- Miller, M.A.; Buss, P.; Parsons, S.D.C.; et al. Conservation of White Rhinoceroses Threatened by Bovine Tuberculosis, South Africa, 2016-2017. Emerg Infect Dis 2018;24(12): 2373-2375.

- Miller, M.A.; Buss, P.E.; van Helden, P.D.; Parsons, S.D. Mycobacterium bovis in a Free-Ranging Black Rhinoceros, Kruger National Park, South Africa, 2016. Emerg Infect Dis 2017;23(3): 557-558.

- Miller, M.; Michel, A.; van Helden, P.; Buss, P. Tuberculosis in Rhinoceros: An Underrecognized Threat? Transbound Emerg Dis 2017;64(4): 1071-1078.

- Dwyer, R.; Goosen, W.; Buss, P.; et al. Epidemiology of Mycobacterium bovis infection in free-ranging rhinoceros in Kruger National Park, South Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022;119(24): e2120656119.

- Kudo, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of a Novel Anti-CD44 Variant 5 Monoclonal Antibody C(44)Mab-3 for Multiple Applications against Pancreatic Carcinomas. Antibodies (Basel) 2023;12(2). [CrossRef]

- Okada, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of a Sensitive Anti-Mouse CD39 Monoclonal Antibody (C(39)Mab-1) for Flow Cytometry and Western Blot Analyses. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2024;43(1): 24-31. [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Kaneko, M.K. A cancer-specific monoclonal antibody recognizes the aberrantly glycosylated podoplanin. Sci Rep 2014;4: 5924. [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Honma, R.; Ogasawara, S.; et al. PMab-38 Recognizes Canine Podoplanin of Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2016;35(5): 263-266. [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Ito, Y.; Ohishi, T.; et al. Antibody-Drug Conjugates Using Mouse-Canine Chimeric Anti-Dog Podoplanin Antibody Exerts Antitumor Activity in a Mouse Xenograft Model. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2020;39(2): 37-44. [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. MAP Tag: A Novel Tagging System for Protein Purification and Detection. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2016;35(6): 293-299. [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Kaneko, M.; Neyazaki, M.; et al. PA tag: a versatile protein tagging system using a super high affinity antibody against a dodecapeptide derived from human podoplanin. Protein Expr Purif 2014;95: 240-247. [CrossRef]

- Kaji, C.; Tsujimoto, Y.; Kato Kaneko, M.; Kato, Y.; Sawa, Y. Immunohistochemical Examination of Novel Rat Monoclonal Antibodies against Mouse and Human Podoplanin. Acta. Histochem. Cytochem. 2012;45(4): 227-237. [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kuno, A.; et al. Inhibition of tumor cell-induced platelet aggregation using a novel anti-podoplanin antibody reacting with its platelet-aggregation-stimulating domain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006;349(4): 1301-1307. [CrossRef]

- Bernitz, N.; Kerr, T.J.; Goosen, W.J.; et al. Review of Diagnostic Tests for Detection of Mycobacterium bovis Infection in South African Wildlife. Front Vet Sci 2021;8: 588697. [CrossRef]

- Hlokwe, T.M.; van Helden, P.; Michel, A.L. Evidence of increasing intra and inter-species transmission of Mycobacterium bovis in South Africa: are we losing the battle? Prev Vet Med 2014;115(1-2): 10-17.

- Michel, A.L.; Bengis, R.G.; Keet, D.F.; et al. Wildlife tuberculosis in South African conservation areas: implications and challenges. Vet Microbiol 2006;112(2-4): 91-100. [CrossRef]

- Espie, I.W.; Hlokwe, T.M.; Gey van Pittius, N.C.; et al. Pulmonary infection due to Mycobacterium bovis in a black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis minor) in South Africa. J Wildl Dis 2009;45(4): 1187-1193. [CrossRef]

- Shadwick, R.E.; Russell, A.P.; Lauff, R.F. The structure and mechanical design of rhinoceros dermal armour. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 1992;337(1282): 419-428. [CrossRef]

- Plochocki, J.H.; Ruiz, S.; Rodriguez-Sosa, J.R.; Hall, M.I. Histological study of white rhinoceros integument. PLoS One 2017;12(4): e0176327. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).