1. Introduction

It is currently accepted that in a vacuum, all objects fall with the same gravitational acceleration [

1,

2,

3] . There is an experiment called Newton’s tube, which involves a tube about two meters long. Inside the tube, substances of different densities, such as paper, cork, lead, etc., are placed. By creating a vacuum inside the tube and inverting it, it can be observed that all the objects fall simultaneously [

4]. It is also accepted that in the presence of a fluid with appreciable density, heavier objects fall with greater acceleration. This is explained by a combined effect of drag force and buoyant force, both exerted by the fluid on the object. These forces slow down the motion, allowing heavier objects to experience a greater net force and higher acceleration [

5,

6,

7]. Research spanning from elementary school classrooms to graduate-level courses has repeatedly delved into how learners perceive the behavior of falling objects. A recurring misconception is that bulkier items plummet faster than their lighter counterparts. Educators, however, have creatively shattered this myth with experiments. For instance, dropping various compact items—like a scrunched-up paper ball, a hefty textbook, a solid rock, a basketball, and a bowling ball—from the same height illustrates that they all touch the ground nearly simultaneously. This holds even in the presence of air, a fluid that offers only minimal resistance due to its low density and viscosity. The tiny time differences between their descents are so negligible that they can essentially be dismissed [

8,

9].

There are many studies on objects falling in the presence of a fluid. For instance, a theoretical approach for estimation of the drag correlation coefficients in the flow of Newtonian or weak non-Newtonian liquids around spherical solid particles is studied [

10]. The terminal velocity and drag coefficient of free-falling discs, cylinders, and irregular particles in different fluids are described [

11]. The classical problem of spheres falling through viscous fluids for small Reynolds numbers was solved taking into account the effects of added mass [

12] . Kozlov et al. devoted themselves to an experimental study of the fluid motion induced by a light spherical body floating along the axis of a rotating vertical cylinder [

13]. A series of particle-resolved direct numerical simulations were conducted using FLOW-3D (commercial computational fluid dynamics software) for spheres and five regular, non-spherical shapes of sediment particles: prolate spheroid, oblate spheroid, cylinder, disk, and cube [

14]. However, there is no study that explores the possibility of lighter objects falling faster than heavier ones. Therefore, the research question (RQ) posed in this study is the following: Is it possible for lighter objects to descend more rapidly in a viscous medium? Indeed, this intriguing phenomenon forms a central focus of the present study. The motion of two spheres with distinct radii, one composed of iron and the other of aluminum, is analyzed as they move through a dense, highly viscous fluid. Each sphere’s motion is considered independently, assuming the fluid is homogeneous and unbounded. The analysis accounts for the forces exerted on the spheres, as well as their acceleration, velocity, and displacement over time. Despite extensive studies on terminal velocity and drag in Newtonian and non-Newtonian fluids, no previous research has explored the paradoxical scenario where a less massive sphere attains a higher terminal velocity than a more massive counterpart. This gap in the literature underscores the originality of the study, positioning it as a critical contribution to both theoretical physics and applied mechanics.

2. Theoretical Approach and Analytical Method

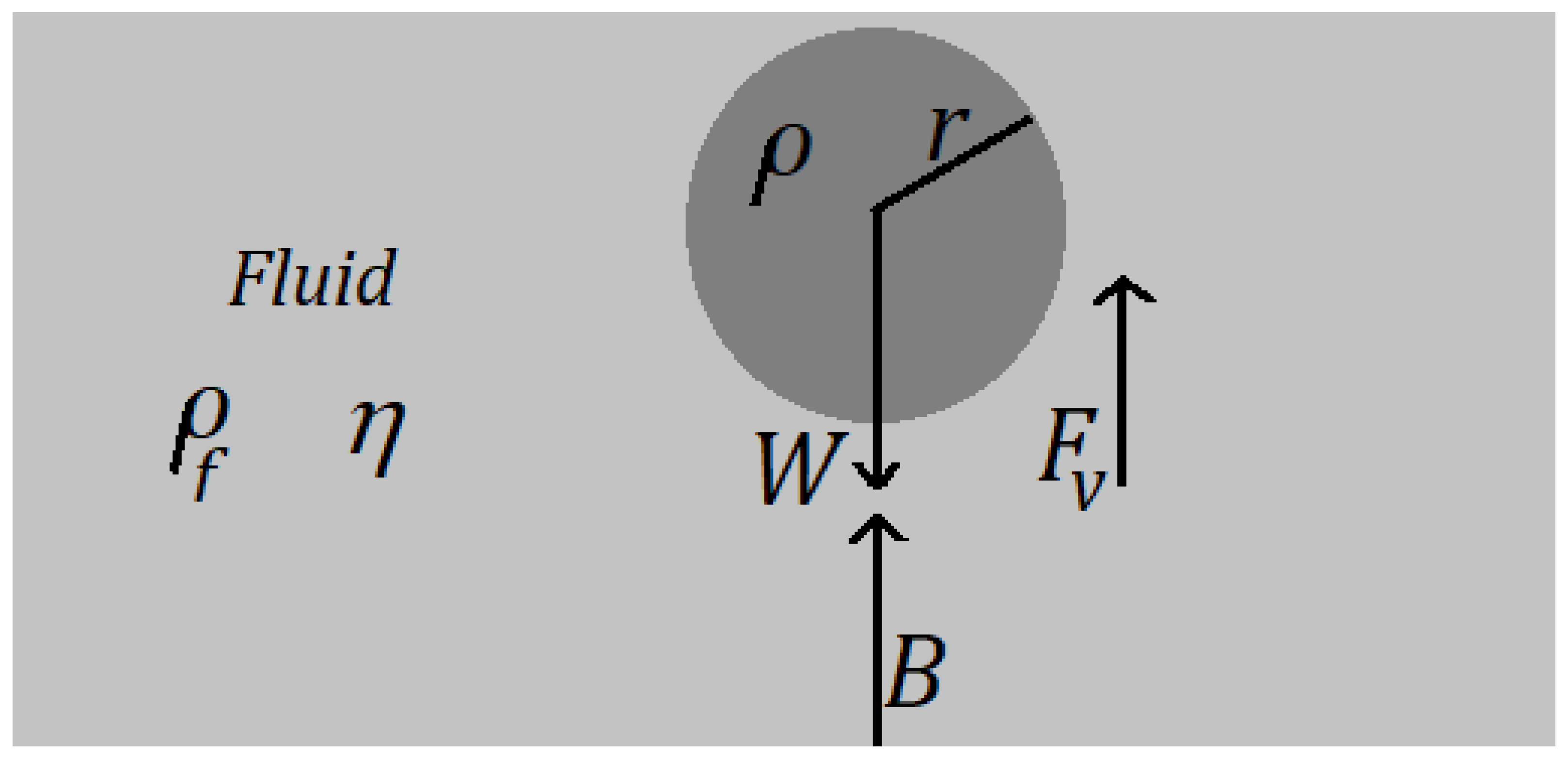

The

Figure 1 illustrates the forces acting on a sphere of density

and ratio

r falling in a fluid of density

and viscosity

. Vectors will be treated as scalar quantities with either positive or negative signs. Positive values will denote a direction toward the center of the Earth, whereas negative values will indicate a direction away from it. The sphere are close to the Earth’s surface, and its weight can be approximated by:

where the gravitational acceleration has been denoted by

g. The fluid exerts both a buoyant force (

B) [

2] and a viscous force (

) [

15] on the sphere, which are described by the following equations:

The preceding expression is Stokes’ law, which has been successfully verified for Reynolds numbers smaller than 1,

[

15]. This number is defined as:

Considering Eqs. (

1), (

2), and (

3) and applying Newton’s law, along with techniques for solving differential equations, expressions for the position, velocity, and acceleration of the sphere as functions of time were obtained.

where

t is the time. The constant

represents the terminal velocity of the sphere and is calculated as:

In Eq. (

6), as time increases, the exponential term approaches zero and the velocity reaches its maximum value

.

The gravitational force pulls the sphere toward the center of the Earth, while the buoyant and viscous forces act in the opposite direction. Therefore, the acceleration of the sphere depends on the ratio between the gravitational force and the opposing forces to the motion, often referred to as the "ratio of forces." This ratio is given by the fraction

Replacing equations (

1), (

2), (

3), and (

6) into equation (

9), the following result is obtained.

The fall of two spheres with different densities and radii will be compared. The first one has a higher density,

, and a radius of

, while the second one has a lower density,

, and a radius of

. The parameter

n is defined as the ratio between the radius of the sphere with higher density and the radius of the sphere with lower density, as follows:

By using Eqs. (

1) and (

11), the ratio of the weights of the spheres is calculated as follows:

By employing Eqs. (

8) and (

11), the ratio of the terminal velocities can be expressed as follows:

3. Results

The simulations are conducted using an iron sphere with a density of kg/m3 and an aluminum sphere with a density of kg/m3. Honey was used as the fluid, with a viscosity of Pa · s and a density of kg/m3.

3.1. Comparison of the Times at Which the Spheres Reach Their Terminal Velocities

When the forces acting on the sphere are in equilibrium, the ratio of the gravitational force to the forces opposing the motion in Eq. (

10) equals 1. As a consequence, the acceleration in Eq. (

7) tends to zero, and the velocity in Eq. (

6) attains its maximum value,

. At this stage, the exponential factor in Eqs. (

6), (

7), and (

10) becomes nearly zero. The two spheres reach their terminal velocities simultaneously when the time coefficients in the exponential terms for each sphere are nearly identical. In this situation, the ratio between the radii of the spheres is given by:

Using the previously mentioned densities of iron and aluminum,

is obtained. For

, the sphere with lower density reaches its terminal velocity after the sphere with higher density. Conversely, for

, the sphere with higher density reaches its terminal velocity after the sphere with lower density. This will be useful in the following sections.

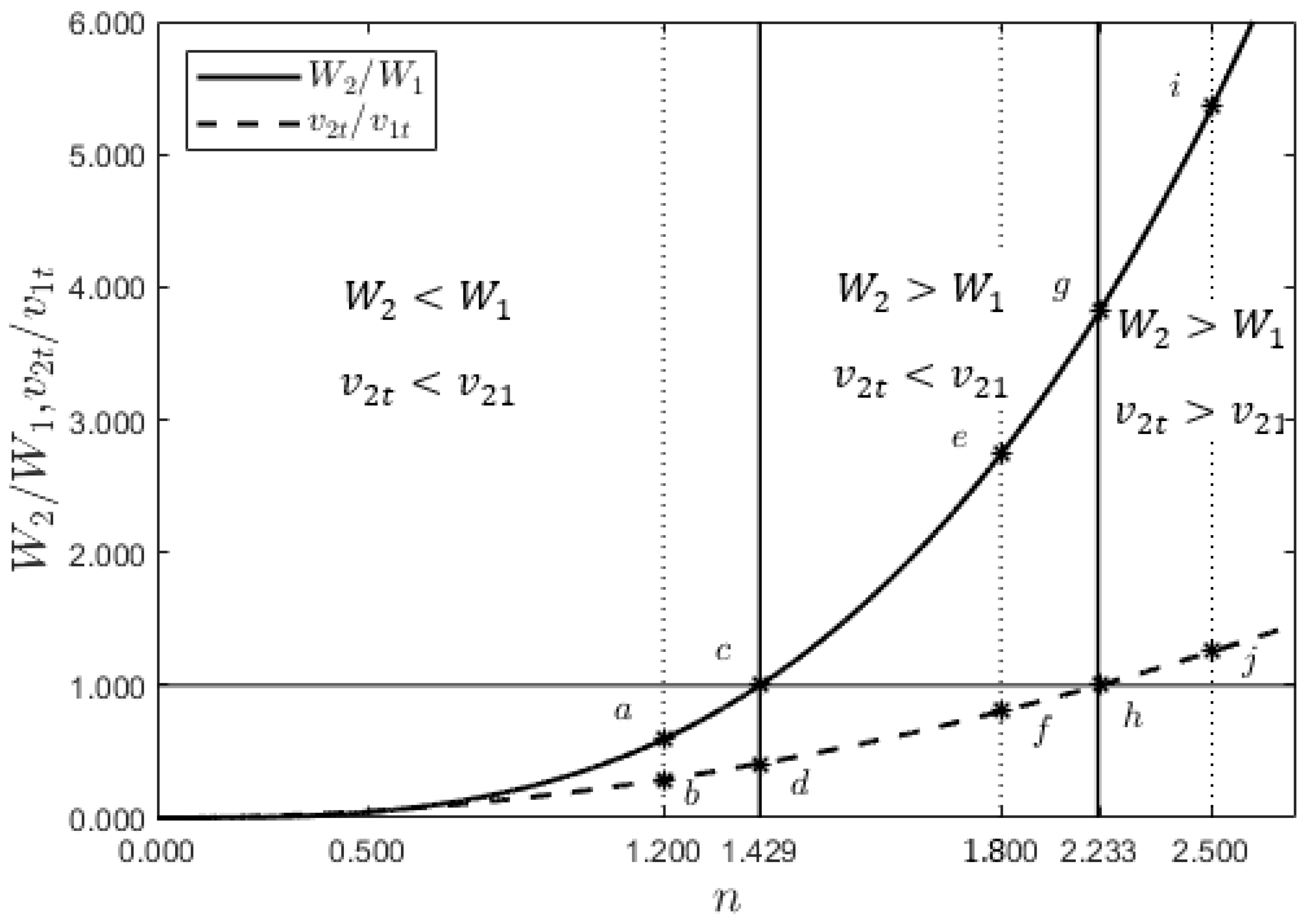

3.2. Comparing the Weights of the Spheres and Their Terminal Velocities

Figure 2 shows the ratio of weights (solid line) and the ratio of terminal velocities (dashed line) as a function of the ratio of radii. Let

be the radius of the iron sphere and

the radius of the aluminum sphere. The ratio

determines which sphere is heavier and which one has a larger terminal velocity. When the ratio between the weights of the spher

, as given by Eq. (

12), is greater than 1.000, the aluminum sphere is heavier, and if this ratio is smaller than 1.000, the heavier sphere is the iron one. If

, the spheres have equal weights. Similarly, when the ratio between the terminal velocities of the aluminum sphere and the iron sphere

, as given by Eq. (

13), is greater than 1.000, the aluminum sphere has a larger terminal velocity, and if this ratio is smaller than 1.000, the iron sphere has a larger terminal velocity. If

, the spheres have equal terminal velocities.

Figure 2 shows the curves obtained from equations (

12) and (

13). The spheres have equal weights (

) at point

c on the solid line for

, and equal terminal velocities (

) at point

h on the dashed line for

. When the spheres have the same weight, the denser one has a higher terminal velocity, as indicated by point

d in (

Figure 2). Conversely, when the spheres have the same terminal velocity, the less dense sphere has a greater weight, as indicated by point

g in (

Figure 2). We considered three intervals in the domain of the following functions.

3.2.1. The Iron Sphere Is Heavier and Falls with a Higher Terminal Velocity

For

, the solid line is below the horizontal line

, and the dashed magenta line is below the straight line

indicating that the iron sphere is heavier than the aluminum sphere and has a higher terminal velocity in the corresponding interval

3.2.2. The Iron Sphere Is Lighter and Falls with a Higher Terminal Velocity

For

, the solid line is above the straight line

, and the dashed magenta line is below the horizontal line

, indicating that in this interval the iron sphere is lighter and falls with a higher terminal velocity. The corresponding interval is

3.2.3. The Aluminum Sphere Is Heavier and Falls with a Higher Terminal Velocity

For

the solid line is above the straight line

, and the dashed magenta line is above the straight line

. Therefore, the aluminum sphere is heavier and falls with a higher terminal velocity in the following interval:

The three intervals mentioned above are summarized in the

Table 1 and will be analyzed in detail in the following sections.

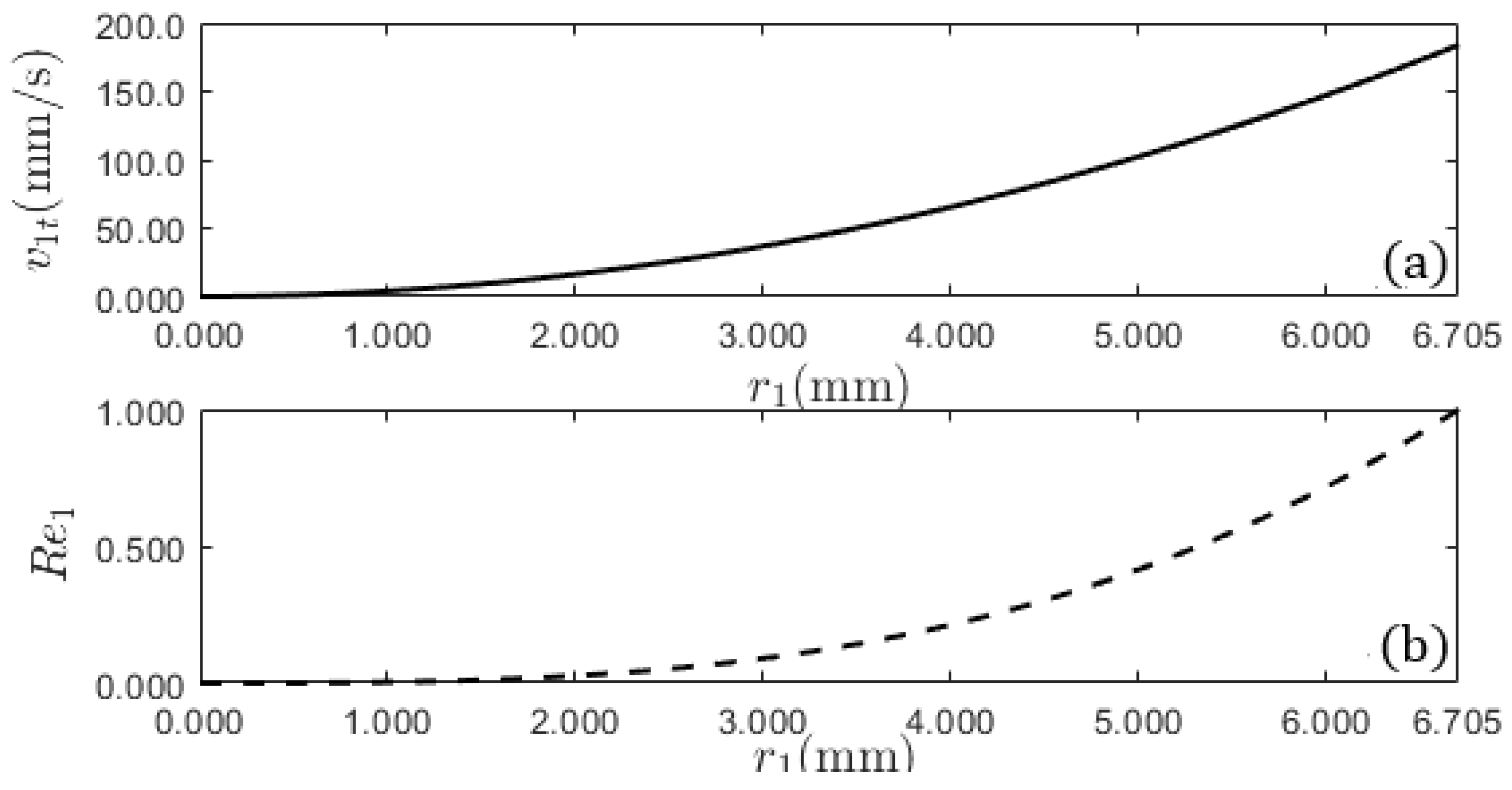

3.3. Allowed Values for the Radii of the Spheres

Stokes’ law, which describes the viscous force on a sphere, is valid for Reynolds number (Eq.

4) values smaller than 1. The terminal velocity and the Reynolds number of the iron sphere as a function of its radius are plotted in

Figure 3a and

Figure 3b, respectively. As the Reynolds number must not exceed the value of 1.000, the range of values for the radius of the iron sphere is:

In the same way, for the aluminum sphere, according to (

Figure 4a) and (

Figure 4b), the valid values for its radius are:

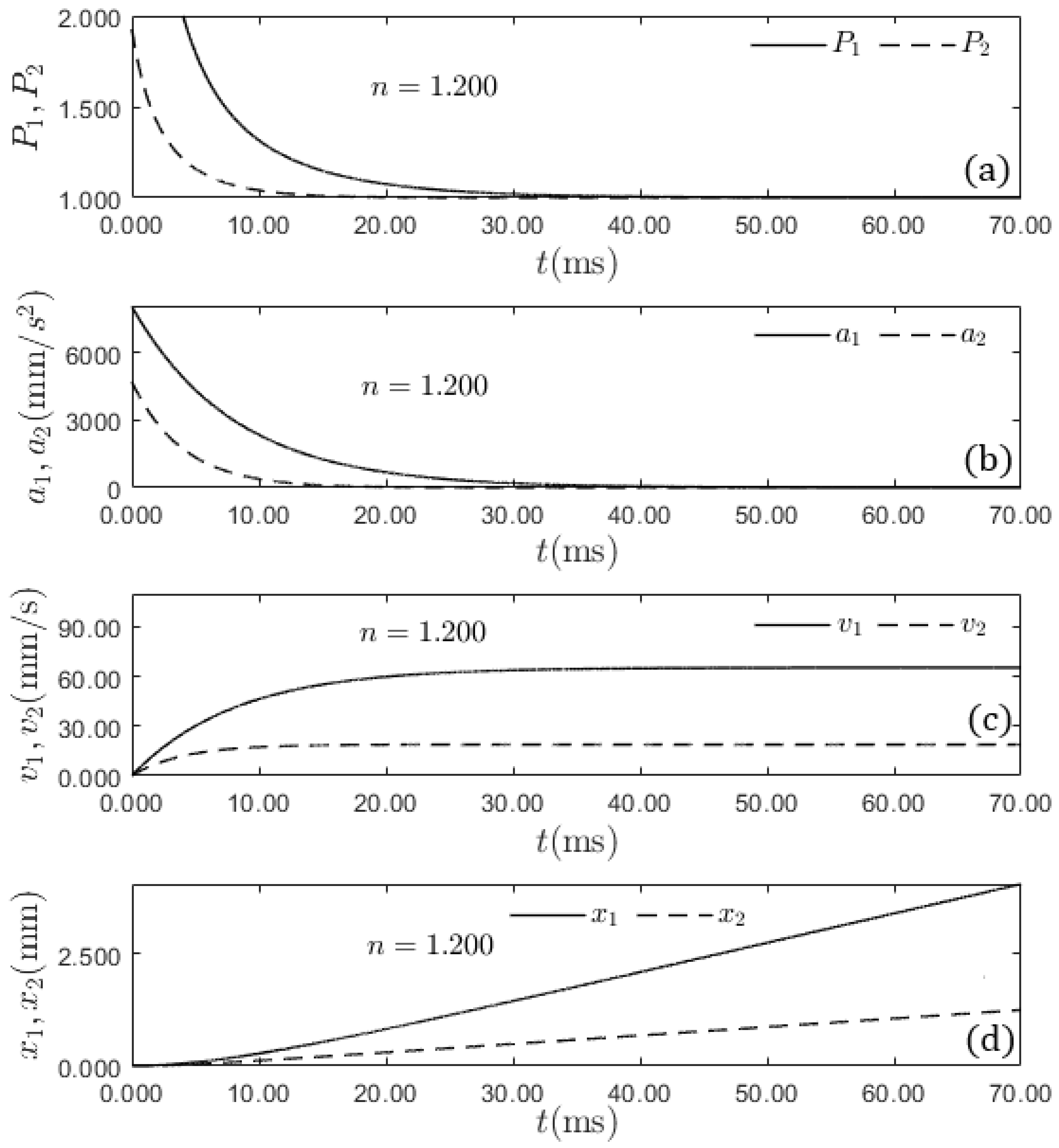

3.4. The Heavier Sphere Falls with a Higher Terminal Velocity

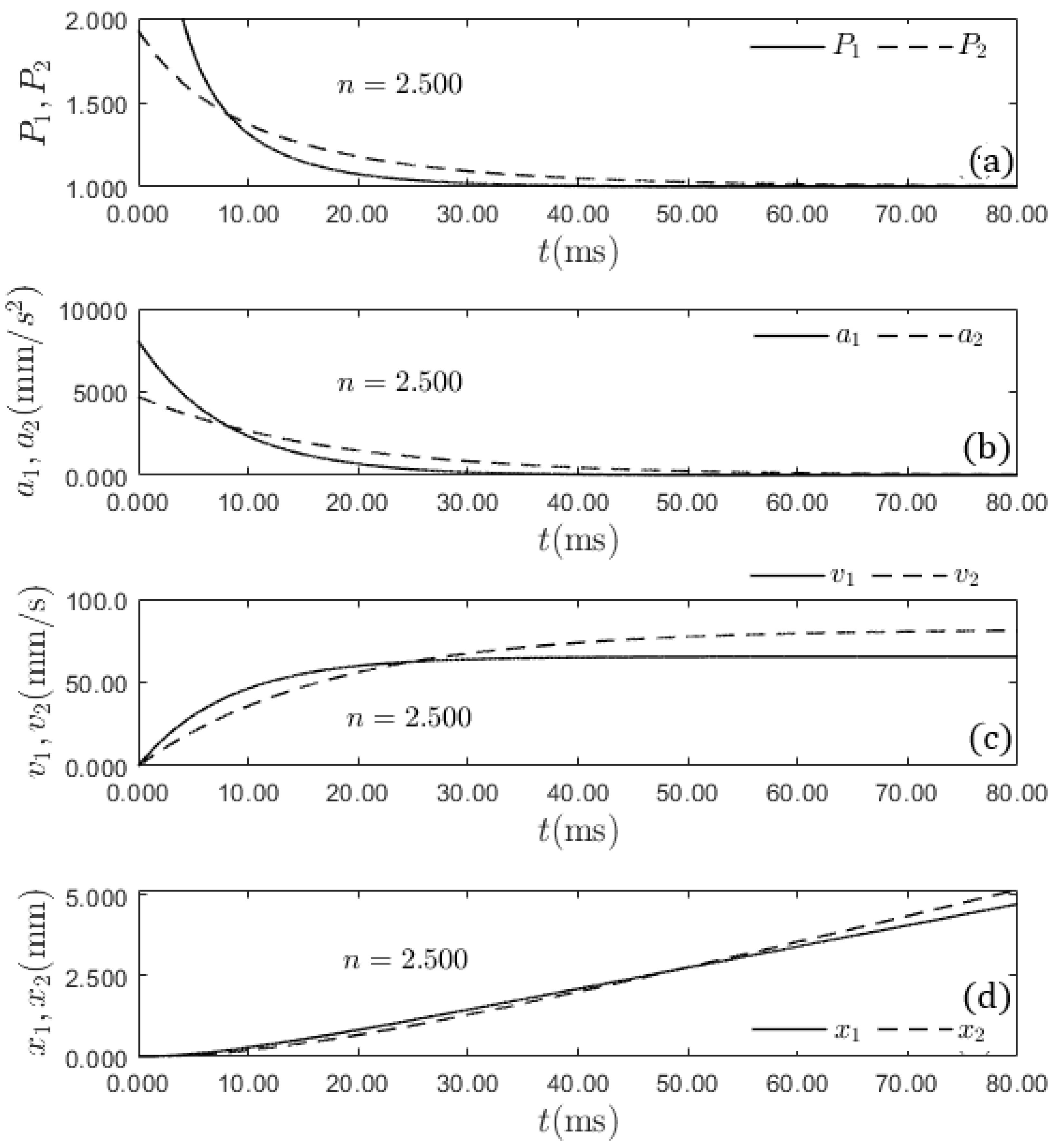

Figure 5c plots the velocities of the two spheres as a function of time for

mm and

mm.

According to

Section 3.2.1,

lies within the interval where the iron sphere is heavier and has a higher terminal velocity. This can be corroborated because the points

a and

b for

in (

Figure 2) lie below the line

. According to Eq. (

14) the two spheres reach their terminal velocities simultaneously for

. For

, the iron sphere attains its terminal velocity after the aluminum one. Additionally, the proportion between the gravitational force and opposing forces is larger for the iron sphere (

), before it decays to approximately 1.000 at

ms (see

Figure 5a). This leads to the iron sphere having a greater acceleration (

) before it becomes approximately zero at

ms (

Figure 5b). These factors explain why the iron sphere has a larger velocity for any time in

Figure 5c, and why its position always leads the position of the aluminum sphere in

Figure 5d. Regardless of the height at which the two spheres are released in the viscous medium, the heavier sphere touches the ground first. It has been observed that the sphere with greater density is heavier and has a larger ratio of forces

P, acceleration

a, and velocity

v at any given time.

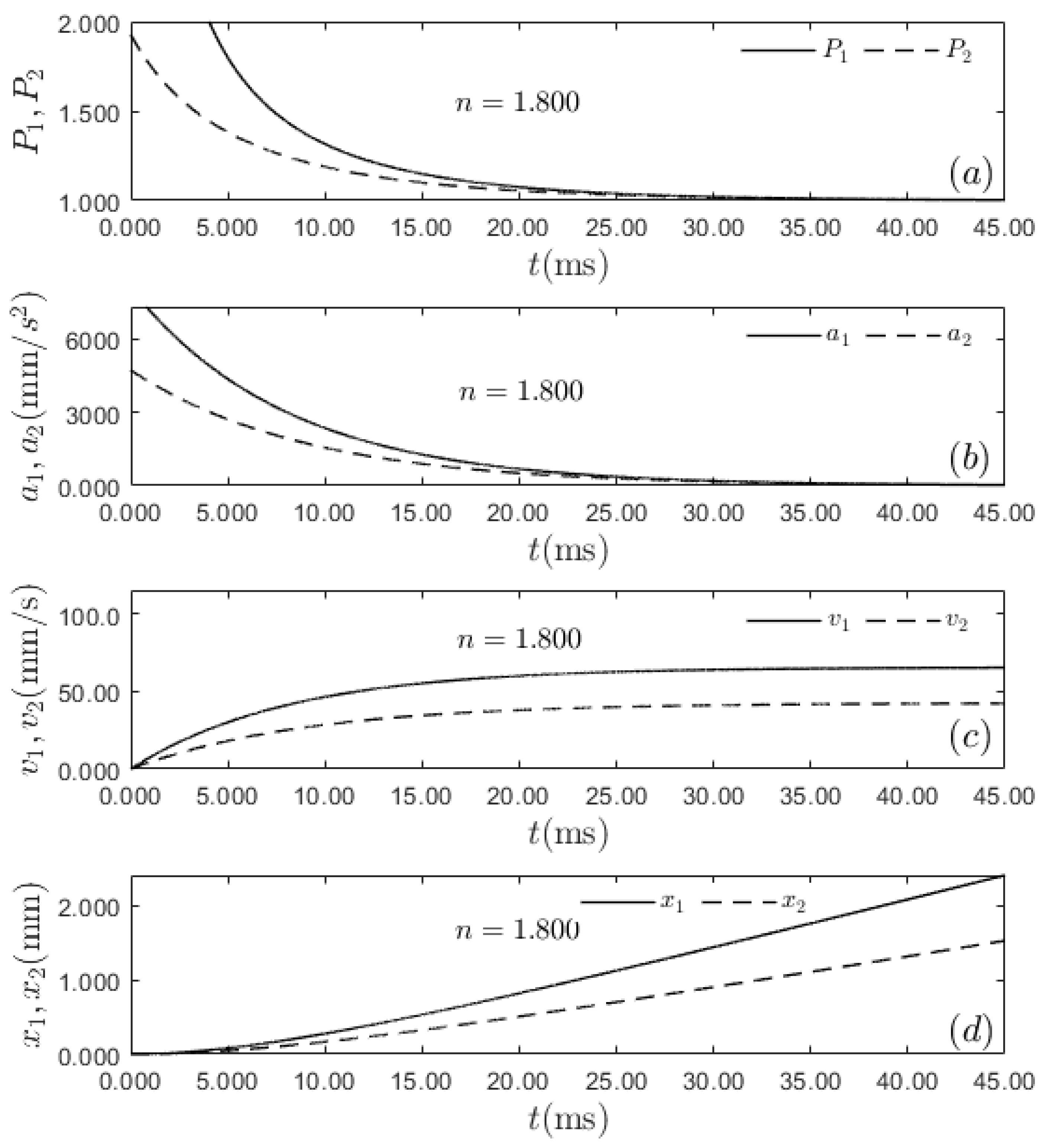

Figure 6c plots the velocities of the two spheres as a function of time for

mm and

mm. According to

Section 3.2.3,

lies within the interval where the aluminum sphere is heavier and has a higher terminal velocity. This can be corroborated because the points

i and

j for

in (

Figure 2) lie above the line

. For

,the aluminum sphere attains its terminal velocity after the iron one. The ratio between the gravitational force and opposing forces to motion is larger for the iron sphere during a small interval of time at the beginning of the motion, specifically for

ms (

Figure 6a), as well as its acceleration (

Figure 6b). The iron sphere has a higher velocity from

until

ms. After

, the ratio of forces

P and the acceleration

a becomes larger for the aluminum sphere over a sufficient interval of time, resulting in the aluminum sphere having a higher velocity beyond

ms.

Figure 6d shows that the position of the iron sphere is ahead of the position of the aluminum sphere for

ms. However, for

ms, the aluminum sphere is always ahead of the iron sphere. At

ms, the spheres have approximately the same position, around

mm. Which sphere hits the bottom of the container first depends on the height at which the spheres were released. If the height is smaller than

mm, the iron sphere will hit the ground first. If the height is greater than 2.500 mm, the aluminum sphere will hit the ground first. If the height is approximately

mm, the spheres hit the bottom of the container at approximately the same time. It has been described a case where the sphere with higher density is actually lighter. Initially, it has a larger ratio of forces

P, acceleration

a , and velocity

v. However, after a short period of time,

P and

a become larger for the heavier sphere, which has lower density. As a result, the heavier sphere with lower density attains a higher velocity.

3.5. The Lighter Sphere Falls with Higher Terminal Velocity

Figure 7c plots the velocities of the two spheres as a function of time for

mm and

mm.

According to

Section 3.2.2,

lies within the interval where the iron sphere is lighter and has a higher terminal velocity. Therefore, the results suggest that the answer to the RQ posed in this study is affirmative, since the point

e in

Figure 2 lies above the line

, and the point

f lies below the line

.

It can be observed that

is approximately equal to

, so the spheres attain their terminal velocities approximately at the same time. The ratio of forces and the acceleration are larger for the iron sphere before the forces acting on each sphere are balanced at approximately

ms. At this time, the ratio of forces for each sphere is around 1.000 (

Figure 7a) and their accelerations are near zero (

Figure 7c). Consequently the velocity of the iron sphere stays larger than that of the aluminum sphere at any time above zero (

Figure 7c). The iron sphere is always ahead of the aluminum one in position (

Figure 7d). It has been described a case where the sphere of higher density is lighter and has a larger ratio of forces and acceleration before the forces on the spheres are balanced. As a result, the velocity is always greater for this sphere. Regardless of the height at which the spheres were dropped, the lighter sphere with higher density will hit the ground first.

Therefore, the present study provides a novel theoretical perspective on the dynamics of objects falling in a viscous medium, challenging the widely accepted notion that heavier spheres always achieve higher terminal velocities. Through analytical modeling and simulations, the research identified specific conditions under which a lighter sphere can surpass a heavier one in terminal velocity, revealing a complex interplay between buoyant, drag, and gravitational forces. This finding has significant implications for fluid dynamics, particularly in educational and engineering applications where assumptions about object motion in viscous environments are frequently employed. The results challenge conventional understandings of motion in viscous media and open new avenues for experimental validation and practical applications in fields such as sediment transport, industrial fluid mechanics, and biomechanics.

4. Conclusions

The fall of two spheres in a medium with appreciable density and viscosity was described. It was graphically demonstrated that there is a range of sphere radii in which the denser sphere is the lighter one and has a higher terminal velocity. The commonly accepted case, where the heavier sphere has a higher terminal velocity, was also analyzed. There is no range in which the less dense sphere is the lighter one and reaches a higher terminal velocity. The competition between the weight of the spheres and the forces opposing their motion due to the fluid is the determining factor in describing the acceleration, velocity, and position of each sphere as a function of time, allowing for a detailed description of their fall.

There is a range where the denser sphere is the lighter one and another where it is the heavier one. However, in both ranges, at all times before force equilibrium is reached, the denser sphere experiences a greater ratio of weight to opposing forces, acquiring a higher terminal velocity and touching the ground first regardless of the height from which the spheres are released. In the range where the less dense sphere is the heavier one, before each sphere reaches its terminal velocity, some non-trivial behaviors occur in the falling velocity as a function of time. Therefore, to determine which sphere touches the ground first, the release height must first be established.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A. S. M- P. and E. A. A-E..; methodology, L. F. M-M.; software, C. E. D-T.; validation, C. A. G-N. and K. R. C. P-J.; formal analysis, A. S. M-P.; investigation, A. S. M-P.; resources, E. A. A-E.; data curation, C. E. D- T.; writing—original draft preparation, C. A. G-N. and K. R. C. P-J.; writing—review and editing, L. F. M-M.; visualization, A. S. M-P.; supervision,C. E. D-T.; project administration, C. A. G-N. and K. R. C. P-J.; funding acquisition, E. A. A-E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript..

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data obtained during the study are included in this paper. For any questions regarding the data in the paper, you can contact the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Basic Sciences Department of the University of Sinú for providing the space for conducting seminars, discussions, and result analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Oh, J. Y. Understanding scientific inquiries of Galileo’s formulation for the law of free falling motion. Foundations of Sciencie 2016, 567, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serway, R.; Jewett, W. Objetos en caida libre. In Physics for scientists and engineers; Cervantes Gozález, S. R., Ed.; Cengage learning: Mexico, 2008; pp. 36–38. [Google Scholar]

- Young, H. D. and Freedman, R. A. Cuerpos en caída libre. In Física Universitaria; De La Vega, P.; PEARSON, México, 2013; pp. 52.

- Haertel, H.; Jeskova, Z. To drop a feather and a piece of lead in a vacuum tube [student experiment]. The IEEE Region 8 EUROCON 2003. Computer as a Tool. 2003, 2, 324–326. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, A.; Seyffert, A. S.; Lemmer, M. Developing a graphical tool for students to understand air resistance and free fall: when heavier objects do fall faster. Phys. Educ. 2017, 52, 034002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Aristotle’s Physics: A Physicist’s look. Journal of the American Philosophical Association 2015, 1, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zee, E. H. V. and Minstrell, J. Reflective discourse: Developing shared understandings in a physics classroom. International Journal of Science Education 1997, 19, 209–228. [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, C.; Sneider, C. Y. Learning about gravity I. Free fall: A guide for teachers and curriculum developers. Astronomy Education Review 2007, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syuhendri, S.; Andriani, N.; and Taufiq, T. Preliminary development of conceptual change texts regarding misconceptions on basic laws of dynamics. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series. En Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing 2019, 1166, 012013.

- Ahbasov, T.; Herdem, S. and Memnedov, A. On the drag force of a solid sphere in power law flow model. Mathematical and Computational Applications 1999, 4, 161–167. [CrossRef]

- Kalman, H. and Portnikov, D. Free falling of non-spherical particles in Newtonian fluids, A: Terminal velocity and drag coefficient. Powder Technology 2024, 434, 119357. [CrossRef]

- Soares, A. A.; Caramelo, L. and Andrade, M. A. P. M. Study of the motion of a vertically falling sphere in a viscous fluid. European journal of physics 2012, 33, 1053. [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, V.; Zvyagintseva, E.; Kudymova, E. and Romanetz, V. Motion of a light free sphere and liquid in a rotating vertical cylinder of finite length. Fluids 2023, 8, 49. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Cao, Z.; Li, J. and Borthwick, A. A numerical study of the settling of non-spherical particles in quiescent water. Physics of Fluids 2016, 35, 21.

- Stretter, V. Flujo y arrastre: Esferas. In Mecánica de Fluidos; Emma Ariza H.; Mc Graw Hill, 1979; pp. 325–328.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).