Introduction

The intricate dynamics of the global tanker freight market have long been a subject of interest for both academicians and industry practitioners due to its critical role in the shipping market, i.e. Adland and Cullinane [

1], Zhang and Zeng [

2], and Sun et al [

3]. This market exhibits complex behaviors that are influenced by a multitude of factors, including geopolitical events [

4,

5,

6], economic conditions [

7], technological innovations, and environmental policies [

8]. The study of these dynamics is further complicated by the market's inherent volatility and the interplay of various scales of temporal correlations [

9,

10]. Examination of market trends assists stakeholders in harnessing shifts to their advantage, while the progressive integration of technology reshapes market operations [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Despite the growing interest in this field, there remain several gaps and challenges that warrant further investigation. A need for a more nuanced understanding of the causal relationships between the multifractal dynamics of the tanker freight market and the various external factors that influence it, such as geopolitical tensions, economic cycles, and environmental policies, see Gao and Zhang [

4], and Chen et al. [

9]. There is also a need for more interdisciplinary research that integrates insights from complexity economics, financial engineering, and operations research to develop more sophisticated methodologies for analyzing and managing the risks associated with changing dynamics in the tanker freight market [

19,

20,

21].

Complexity economics provides a framework for interdisciplinary research of economics, information, physics and operations [

22,

23,

24]. It acknowledges the differences among agents, their imperfect information, and the dynamic nature of economic systems, providing significant insights applicable to both the fields of information and economics [

25,

26,

27,

28], including the energy and tanker freight market [

4,

12]. A series of models for fractals are developed as an effective tool for complexity economics studies. Fractals, known for their fragmented and rough geometric shapes, have the fascinating property of self-similarity, allowing them to be broken down into smaller parts that closely resemble the whole[

29,

30]. A variety of methodologies have been devised to analyze fractal attributes. One of the first was the rescaled range analysis by Hurst, which, however, faces challenges in assessing long-range dependencies in nonstationary series [

31]. To tackle multi-affine fractal exponents and correlation coefficients, Castro et al. introduced a novel approach [

32]. Around the same time, Peng et al. firstly constructed a different method called detrended fluctuation analysis (DFA) to discern long-term correlations within data [

33]. While DFA provided a valuable tool, it fell short when it came to multi-scale and fractal elements in time series that demonstrated more complex, non-monofractal scaling. To bridge this gap, multifractal detrended fluctuation analysis (MF-DFA) came into play, advanced by Kantelhardt et al. as a multifaceted extension of the DFA method [

34]. MF-DFA has proven to be a robust tool for multifractal characterization and has been used across various stochastic analysis contexts [

35,

36]. In parallel, the detrending moving average (DMA) technique gained traction for its effectiveness in evaluating long memory in nonstationary time series, applicable to both real and theoretical data samples [

37,

38,

39]. By focusing on the moving average function of a series and building on the moving average methodology, DMA excels in discerning scaling properties within time series data [

40]. MF-DMA extended DMA to higher-dimensional versions. It is a quantitative analysis delving into the spurious multifractality induced by fat-tailed probability distributions in time series, providing critical insights into distinguishing true multifractality arising from nonlinear correlations from spurious effects generated by distribution shapes [

41,

42]. Kwapien et al. use analytical arguments as well as numerical illustrations on the interesting question of the origin of the multifractality in time series [

43]. They get the conclusion that true multifractality in time series comes from temporal correlations.

The array of studies on tanker freight rate volatility represents a vital component of maritime economics, with ramifications extending into the broader global economy, delve into the interplay between numerous variables affecting freight rates, such as crude oil prices, charter rates, fleet size, and policy changes [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

44]. Multifractal analysis has emerged as a new trend in these studies, gaining traction due to its ability to capture the asymmetric nature of market risks, demonstrating different magnitudes of response to upward and downward trends and uncovers various scaling behaviors within the data[

45,

46]. Multifractality helps to recognize the freight rates which exhibit a spectrum of fractal characteristics, not just a single pattern of fluctuations [

47,

48,

49,

50]. It accounts for both small and large movements, providing a nuanced perspective on data correlations, especially under turbulent market conditions like those experienced during the 2008 world finance risk and the COVID-19 pandemic [

4,

12,

46]. This study tries to comprehend the intricate, multifaceted nature of the market to design strategies that buffer the fallout from unpredictable market shifts or crises, provide a comprehensive understanding of the market's complexity and its evolution over time.

The research is driven by the following key questions: (a) How has the multifractal nature of the tanker freight market evolved across the two distinct periods, and what does this evolution signify in terms of market behavior and systemic risks? (b) What role do temporal correlations and inherent volatility play in shaping the complex structure of the market, and how do these factors contribute to the observed multifractal dynamics? (c) How do external factors such as regulatory changes, economic disturbances, technological innovation, and environmental concerns influence the complexity and multifractal characteristics of the tanker freight market? (d) Can tanker freight rates, specifically the Baltic Dirty Tanker Index (BDTI), be used to predict Brent oil prices during periods of heightened market complexity, and how do multifractal features enhance the predictive power of such models?

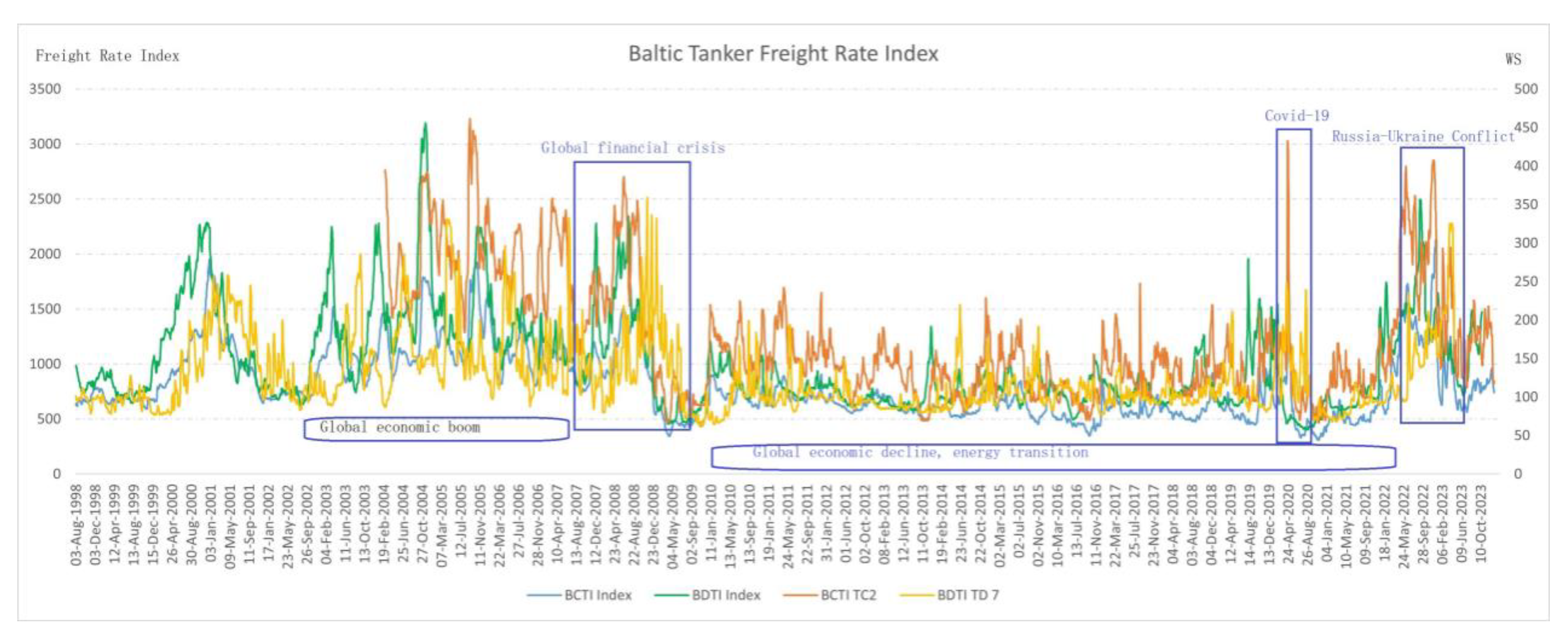

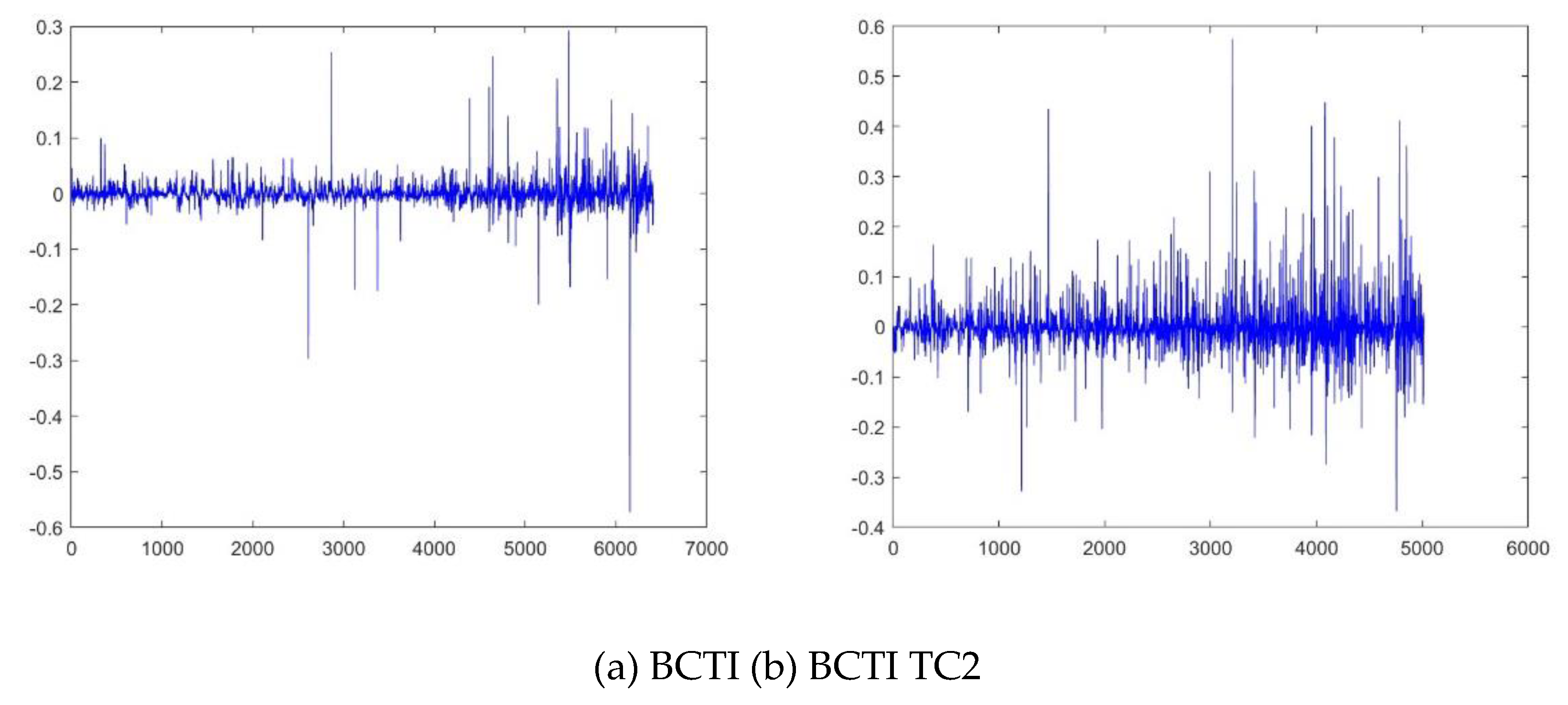

The research presented in this manuscript is motivated by the need to delve into the complex transformation of the Baltic Clean and Dirty Tankers markets from 1998 to 2023, with a particular focus on the multifractal characteristics that define the market's structure and behavior. Here, we apply the MF-DFA method to characterize the observations of clean and dirty tanker freight rates and the most concerned routes of TC2 and TD7 from Jan. 28, 1998, to Jan. 12, 2024. To describe the market pattern after larger fluctuations, we analyze Period I (1998–2010) and Period II (2010–2024). To better explain the multifractality in the BCTI and BDTI series, we apply the MF-DMA method to quantify the three components, including linear correlation, nonlinear correlation, and fat-tailed probability distribution.

Building on this foundational analysis, we further extend the scope of our research to explore the predictive potential of freight rates in forecasting Brent oil prices, particularly during periods of heightened market volatility and complexity. Traditionally, most studies have focused on forecasting freight rates based on oil price movements, reflecting the conventional economic logic that oil prices drive downstream costs, including shipping. However, freight rates, due to their responsiveness to supply-demand dynamics, vessel utilization rates, and macroeconomic shifts, may serve as valuable leading indicators for oil prices. This study, therefore, adopts an innovative perspective by investigating whether BDTI can predict Brent oil prices and how multifractal features contribute to the accuracy of such predictions.

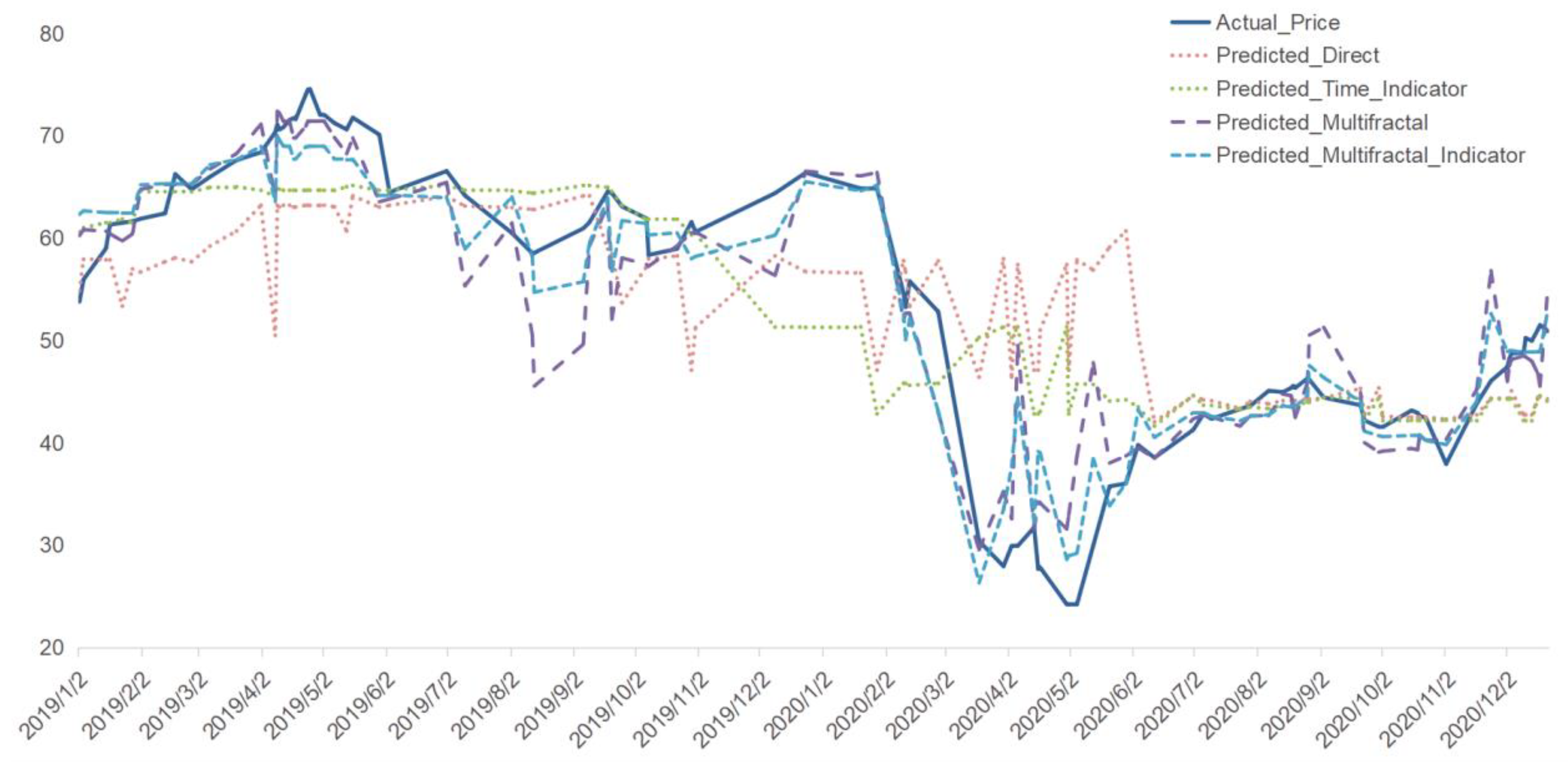

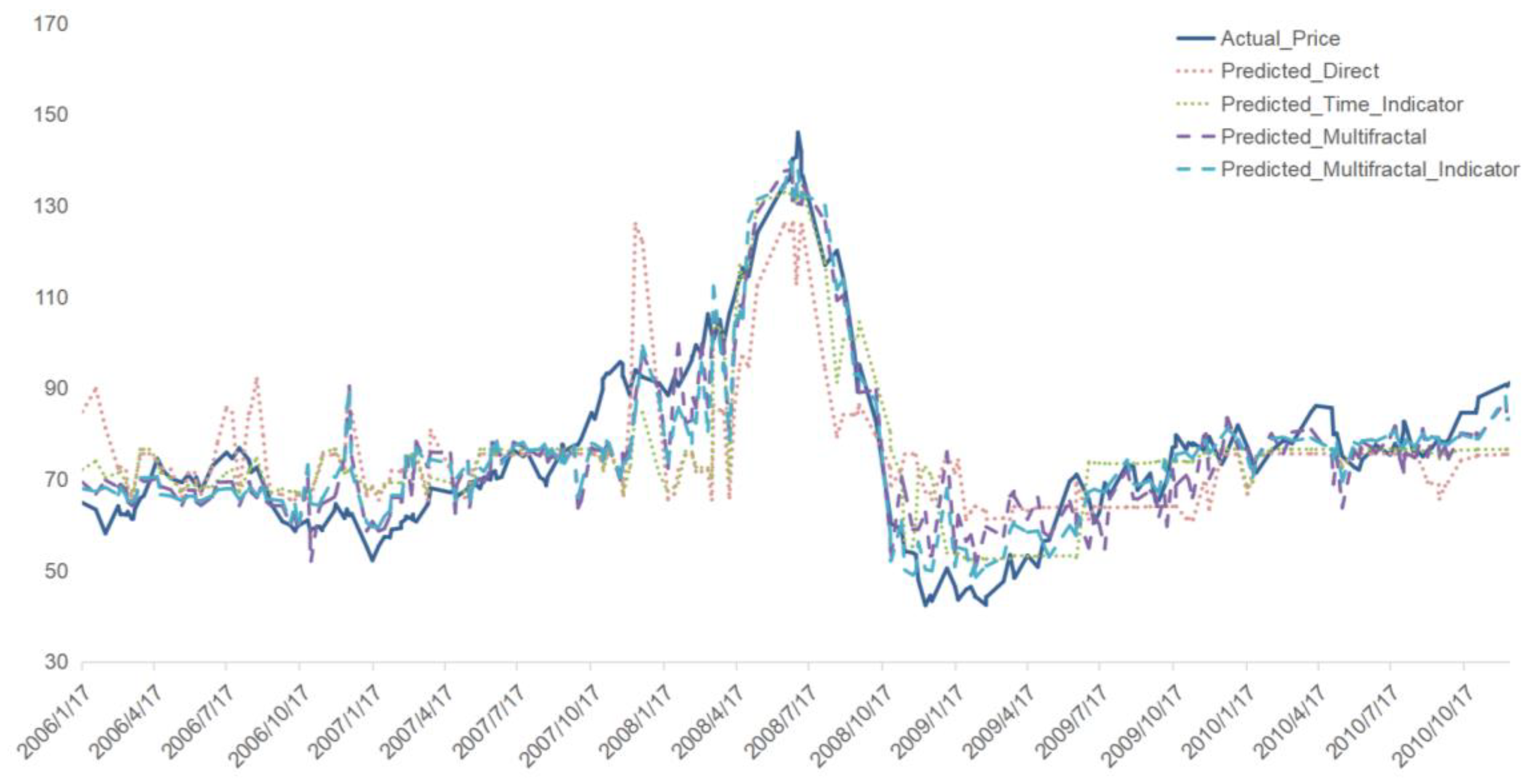

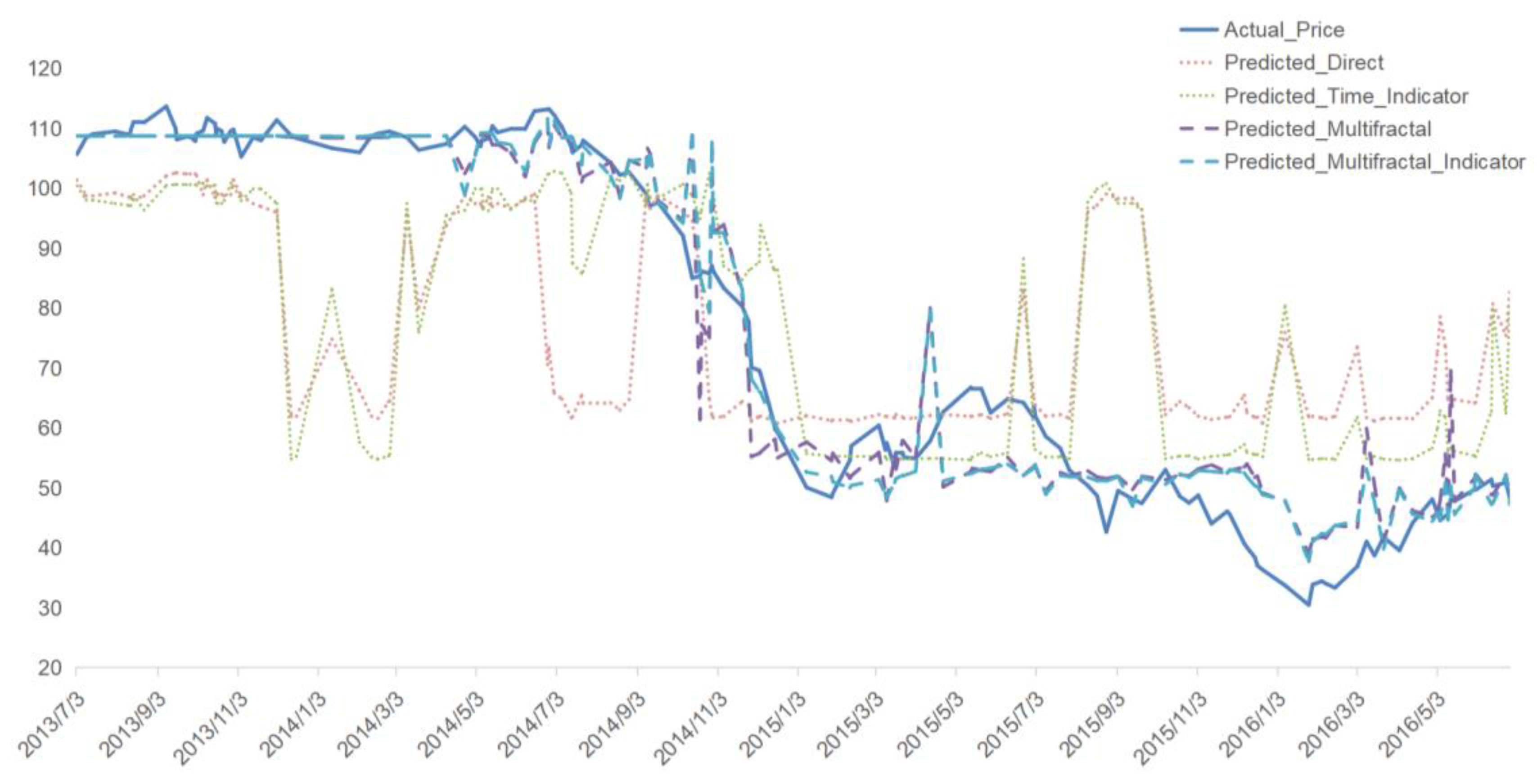

To address this question, we examine four distinct periods characterized by major global events that significantly influenced market dynamics:(1) 2006–2010: Marked by the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, which caused widespread disruptions in financial and commodity markets. (2)2013–2016: Defined by the 2014 Shale Oil Revolution, which reshaped global energy supply dynamics. (3) 2019–2021: Dominated by the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to unprecedented supply chain disruptions. (4) 2021–2024: Influenced by the Russia-Ukraine conflict, introducing severe geopolitical uncertainties and energy market volatility.

For each period, we develop predictive models using BDTI data as a primary feature, integrating multifractal characteristics extracted via MF-DFA, such as the Hurst exponent and multifractal spectrum. These models are enhanced with crisis period indicators to capture the unique market dynamics during each global event. Furthermore, in order to enhance the robustness of predictions, advanced machine learning techniques are leveraged within this study. Specifically, we employ stacking regression models, which incorporate XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost as the foundational base learners[

51,

52,

53]. Among these technologies, XGBoost is designed to be scalable and efficient, allowing data scientists to achieve state-of-the-art results on a variety of machine learning challenges[

54].Additionally, Ridge Regression serves as the meta-learner in this stacking framework. By integrating these powerful algorithms in a structured and systematic manner, we aim to improve the overall accuracy and stability of our predictive models, thereby ensuring more reliable and insightful outcomes[

55,

56,

57].

At the same time, most studies have traditionally focused on forecasting freight rates based on oil price movements, which aligns with the conventional economic logic that oil prices drive downstream costs, including shipping. However, freight rates can be highly responsive to immediate changes in supply-demand dynamics, vessel utilization rates, and macroeconomic shifts, making them potentially valuable indicators for predicting oil prices as well. Thus, in this study, we take an innovative stance by attempting to predict oil prices from freight rates, with the intention of providing additional insights and decision-making tools for governments, businesses, and individual investors, especially during periods of significant market volatility and complexity.

The major contribution of this study is summarized as follows. The methodology evaluates the individual and combined effects of multifractal features and crisis indicators on predictive accuracy. This comprehensive framework not only tests the predictive capacity of freight rates for oil prices but also deepens our understanding of how market complexity evolves during times of significant economic and geopolitical turbulence. In addition to providing theoretical insights, this study offers practical implications for market participants, including energy companies, policymakers, and investors, by highlighting the utility of freight rates as a decision-making tool. The integration of multifractal analysis with predictive modeling demonstrates the potential for advanced analytics to navigate the complexities of modern financial markets effectively.

The paper structure is as follows:

Section 2 introduces the MF-DFA and MF-DMA methods;

Section 3 describes the Baltic Clean and Dirty Tanker Indexes and the data used in the analysis.

Section 4 presents the empirical results, including the multifractal characteristics of freight rate returns, the impact of structural breaks across different periods, and the predictive performance of the proposed framework under varying market conditions.

Section 5 discusses the findings and their implications, and Section 6 concludes the study with key insights and future research directions.

1. Methods

1.1. The Multifractal Detrended Fluctuation Analysis Method

The following introduction of MF-DFA method is based on the work from Kantelhardt, et.al. (2002)[

34].

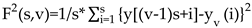

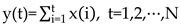

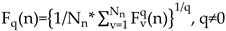

Here are the general steps of MF-DFA method on the series, where and is the length of the series. stands for the average value of series.

Assuming that

are increments of a random walk process around the mean

, then by the signal integration, the "trajectory" or "profile" could be expressed as

Next, we divide the integrated series into

, non-overlapping segments of equal length

. Generally, the length

of the series is not a multiple of the considered time scale

, a short part may remain at the end of the profile

. Not to disregard this remaining part, this procedure is repeated oppositely starting from the end. So

segments are obtained. Next, the local trend for each of the

segments could be calculated by a least-square fit of the series. Then the variance is determined by

for each segment

,

and

For

. Here,

is the fitting line in segment

. Next, over all segments are averaged to obtain the

-th order fluctuation function by

where, the index variable

can generally take any real value except zero. Repeating the above steps for several time scales

,

will increase as

increases. The scaling behavior of the fluctuation functions could be analyzed by log-log plots

versus

for each value of

. A power-law between

and

exists as the Eq. (5) when the series

is long-range power-law correlated.

However, because of the diverging exponent, the averaging procedure of Eq. (4) could not be applied directly to calculate the value

corresponds to the limit

as

. Instead, we must employ a logarithmic averaging procedure by Eq. (6).

The exponent generally depends on . For stationary series, is the well-defined Hurst exponent . So is called the generalized Hurst exponent. In a special case, when is independent from , it is defined as monofractal series. The distinct scaling patterns exhibited by small and large fluctuations have a substantial impact on the relationship between the -th order Hurst exponent and the scaling parameter . In the case of positive , segments characterized by a significant deviation from the expected trend, i.e., those with large variances, will exert a dominant influence on the average -order Hurst exponent . Consequently, a positive captures the scaling behavior of these segments with notable fluctuations, which typically correspond to smaller scaling exponents in multifractal time series. Conversely, for negative values, segments with smaller variances take precedence in determining the average -order Hurst exponent . Hence, a negative describes the scaling behavior of segments with minor fluctuations, which generally exhibit larger scaling exponents in multifractal time series. This intricate interplay between , the scaling behavior of different segments , and the corresponding fluctuations provides valuable insights into the multifractal nature of the time series, shedding light on how various levels of variance impact the overall scaling exponents.

The multifractal spectrum

is another tool to characterize multifractality in a series.

can be obtained by the Eq. (7)

and then the Legendre transform

where

is the Holder exponent value which indicates the strength of singularity. When the

is broader, it indicates a stronger multifractality or complexity.

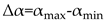

The width of the spectrum could be

where

and

indicate the maximum and minimum values respectively.

We name MF-DFA1, MFDFA2 and MFDFA3 separately with polynomial order . Here we apply MF-DFA1 and MF-DFA2 to investigate the BCTI, BDTI and specific routes of TC2 and TD7.

1.2. The Multifractal Detrending Moving Average Method

Following brief introduction of MF-DMA method is based on works of Gu and Zhou (2010) [

41].

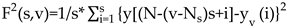

Assuming time series

,

and

is the length of the series. We construct a new series

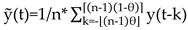

Next step,

indicates the moving average function. To calculate the sequence of cumulative totals, we slide a window of fixed size across the sequence.

where

is the size of window,

is the largest integer but not greater than

,

is the smallest integer but not smaller than

, and

is the position parameter, varying from 0 to 1. Here

is calculated over

data points from the preceding period while

data points from the subsequent period. We have to notice three special cases with different

values. The backward moving average, where

and

is calculated by all the past data points.

refers to the centered moving average, where

is calculated over half past and half future data points.

means the forward moving average, where

is based on the trend of future data points. In this context, we utilize the selected case

, as it has demonstrated superior performance compared to the other two alternatives, based on evidence presented in references [

37,

41,

43].

Subsequently, we eliminate the moving average component

from the series

to eliminate any underlying trend, resulting in a residual sequence

.

where

.

Then, the residual series

is divided into

(

) non-overlapping segments, each of equal length

. These segments can be represented as

for

, where

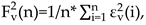

. We can get the root-mean-square function

by Eq. (14).

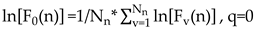

Additionally, the

-th order overall fluctuation function

is expressed as

Next step, when the values of

varies, we can get the power-law relation between

and

in Eq. (17)

Finally, the multifractal scaling exponent and multifractal spectrum could be defined similarly with that of above MF-DFA.

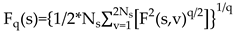

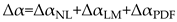

1.3. The Effective Multifractality

According to the references [

58,

61], the total multifractal spectrum could be intricately divided into three parts: the non-linear and linear correlation, and the PDF. This decomposition is captured by the Eq. (18).

It is important to emphasize that both the linear correlation component

and the nonlinear correlation component

represent temporal correlations [

2,

5]. Specifically, the linear correlation component is attributed to finite-size effects [

54,

63]. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that

indicating the linear correlation component, can be computed by semi-analytical formulas of an explicit form, offering a comprehensive quantitative characterization of this phenomenon [

39]. A type of computational deviation stemming from the sample number constraints is defined as the finite-size effect in reference [

26]. In essence, smaller time series sizes lead to greater computation deviations. To mitigate the impact of sample size limitations, especially for small sample sizes (<10000), it is necessary to calculate and exclude the linear correlation component from the true multifractality. Consequently, the true multifractality, denoted as

, which encompasses the nonlinearity component

, and the PDF component

, is determined[

40,

59,

61].

To depict the spectrum of multifractality, it is important to conduct an analysis that involves both the elimination of the linear correlation component stemming from the sample size limitations (sample size < 10000 points) and the decomposition of the remaining two effective parts [

59,

61,

62]. This quantitative analysis can be achieved through the creation of two new series: the shuffled and the surrogated time series. The shuffled time series is generated through the shuffled original series. During the process, the temporal correlations are disrupted, while the probability distribution remains unaltered [

43,

61].

The creation of surrogate data is accomplished through a two-stage procedure. Initially, the process ensures that the surrogate data matches the original volatility time series in terms of probability distribution, which is executed through a transformation technique as described in reference [

49]. Subsequently, the surrogate time series is manipulated to include linear correlations by applying an improved version of the amplitude-adjusted Fourier transform (IAAFT), as detailed in reference [

59]. To gain a thorough grasp of the surrogate time series construction process, it is recommended that readers refer to the comprehensive explanation in the reference [

26].

1.4. Machine Learning-Three Learners

Overall, we selected and combined three learners(XGBoost, LightBGM and CatBoost) from machine learning to form our stacking regression model. Therefore, the introduction of machine learning is based on three researches which are respectively done by Chen T , Guestrin C[

54]; Ke G, Meng Q, Finley T[

64]; Prokhorenkova L, Gusev G, Vorobev A[

65].

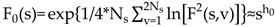

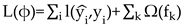

XGBoost is a scalable tree boosting system, which firstly use tree boosting in a nutsheel to regularize learning objective:

where

,

is the loss function,

is the predicted value,

is the target value,

and

are regularization parameters,

is the number of trees, and

represents the square of the output score on each tree's leaf nodes (equivalent to L2 regularization) .

Then, the system add ft to minimize objective and use second-order approximation to quickly optimize the objective in the general setting, the corresponding optimal is:

In the final stage, it is necessary to scale the newly added weights and perform column sampling to prevent overfitting (similar to random forests). XGBoost also includes a split finding algorithm, where the basic greedy algorithm enumerates all possible splits, calculates the gain for each split, and then selects the split with the maximum gain. The approximate algorithm, on the other hand, proposes candidate split points by mapping continuous features into bins and then aggregating statistics to find the optimal solution. In summary, XGBoost introduces a new sparse-aware algorithm and weighted quantile sketch, where caching access patterns, data compression, and partitioning are key, thus enabling the solution of real-world scale problems with minimal resources.

LightGBM is an efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) algorithm proposed by Ke et al. at the NIPS conference in 2017. It addresses the efficiency and scalability issues associated with high-dimensional features and large datasets by introducing two innovative techniques: Gradient-based One-Side Sampling (GOSS) and Exclusive Feature Bundling (EFB). The GOSS technique excludes data instances with small gradients, using only the remaining instances to estimate the information gain, thereby significantly reducing the amount of data processed while maintaining the accuracy of information gain estimation. The EFB technique reduces the number of features by bundling mutually exclusive features that rarely take non-zero values simultaneously, such as one-hot encoded features in text mining. LightGBM safely bundles these exclusive features together, constructing the same feature histograms from feature bundles as from individual features through a carefully designed feature scanning algorithm, thus reducing the complexity of histogram construction from O(#data×#feature) to O(#data×#bundle), where #bundle is much smaller than #feature, significantly accelerating the training of GBDT. Experimental results show that LightGBM is over 20 times faster in training on multiple public datasets while achieving nearly the same accuracy as traditional GBDT. These achievements not only demonstrate the superior performance of LightGBM in handling large-scale datasets but also provide new directions for the optimization of GBDT algorithms.

CatBoost introduced two algorithmic improvements: ordered boosting and an innovative algorithm for handling categorical features, corresponding to the Ordered mode and Plain mode (built-in ordered TS standard GBDT algorithm). For the Plain mode, multiple random permutations are first used to calculate gradients and TS, evaluate candidate splits, update the support model to construct decision trees, and then a complexity comparison and analysis with the standard GBDT algorithm is performed, culminating in the greedy construction of high-order feature combinations. CatBoost identified and analyzed the problem of prediction shift, proposing ordered boosting and ordered TS as solutions, and demonstrated superior performance in multiple benchmark tests.

1.5. Predictive Methodology Overview

To investigate how freight rates can help predict Brent oil prices in different periods, we employed the following methodology across four distinct periods (Period I-IV). In

Table 1, each of these periods corresponds to a significant global event that profoundly affected both freight rates and oil prices.

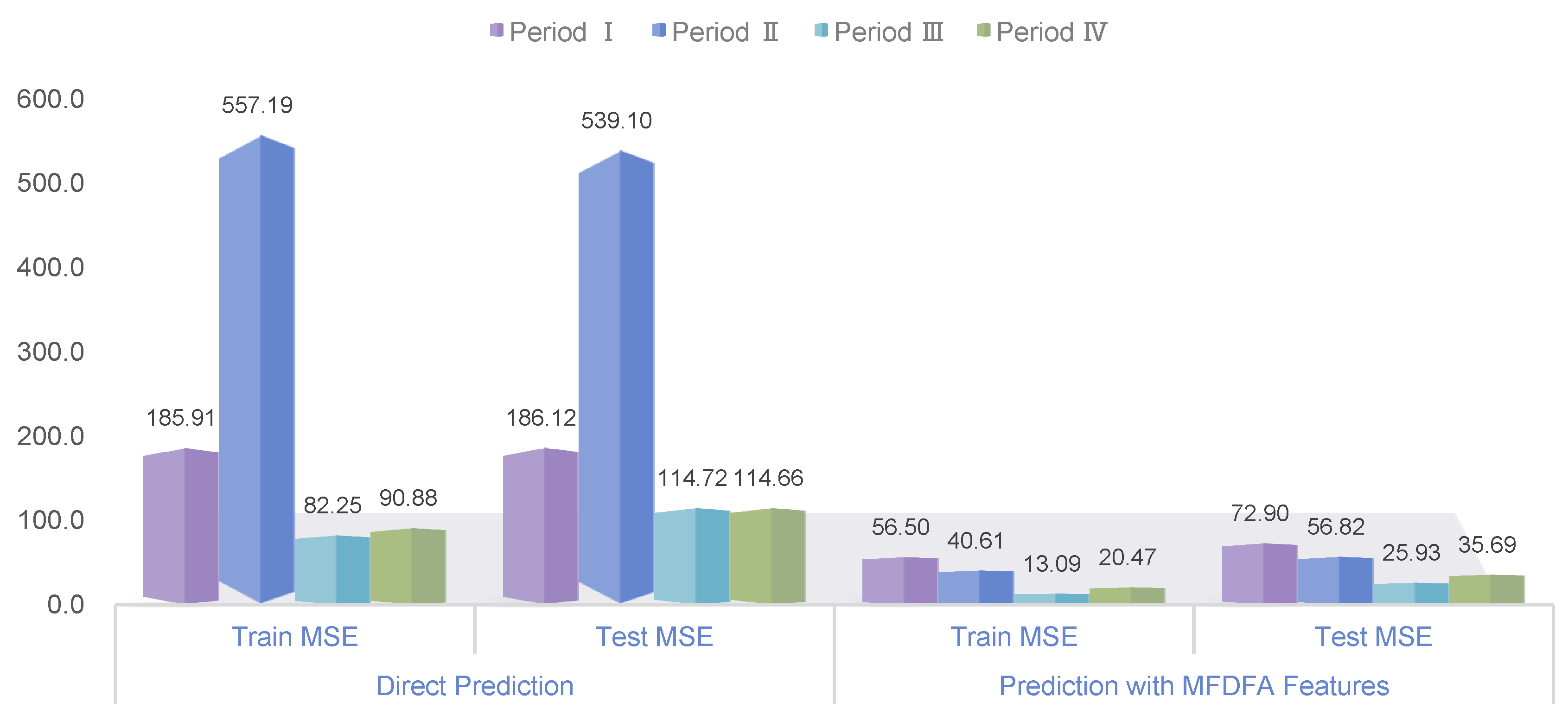

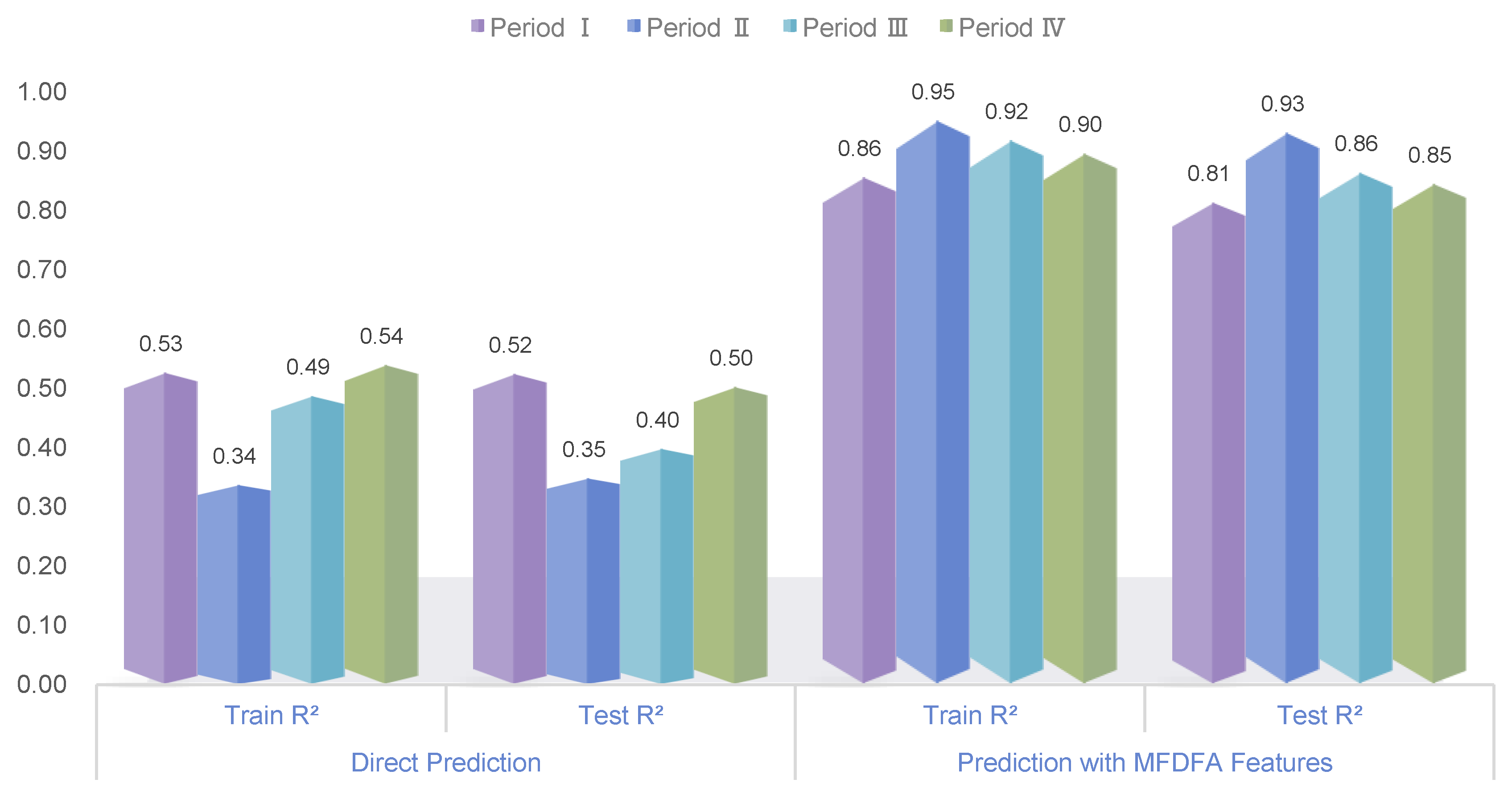

For each of these periods, we employed the same predictive approach to understand the effect of multifractal features on forecasting oil prices. Specifically, the freight rates (BDTI) were utilized alongside different feature sets to predict Brent oil prices, with the following steps:

Direct Prediction Using BDTI: As a baseline, we predicted Brent prices using only BDTI data.

Addition of Crisis Period Indicator: We added an indicator for the crisis period to account for the impact of significant events (e.g., the financial crisis or the pandemic) on market dynamics.

Addition of Multifractal Features: Multifractal features extracted using the Multifractal Detrended Fluctuation Analysis (MFDFA) method were included to capture complex market behaviors.

Combination of Crisis Indicators and Multifractal Features: Both crisis indicators and multifractal features were included to examine their combined effect on prediction accuracy.

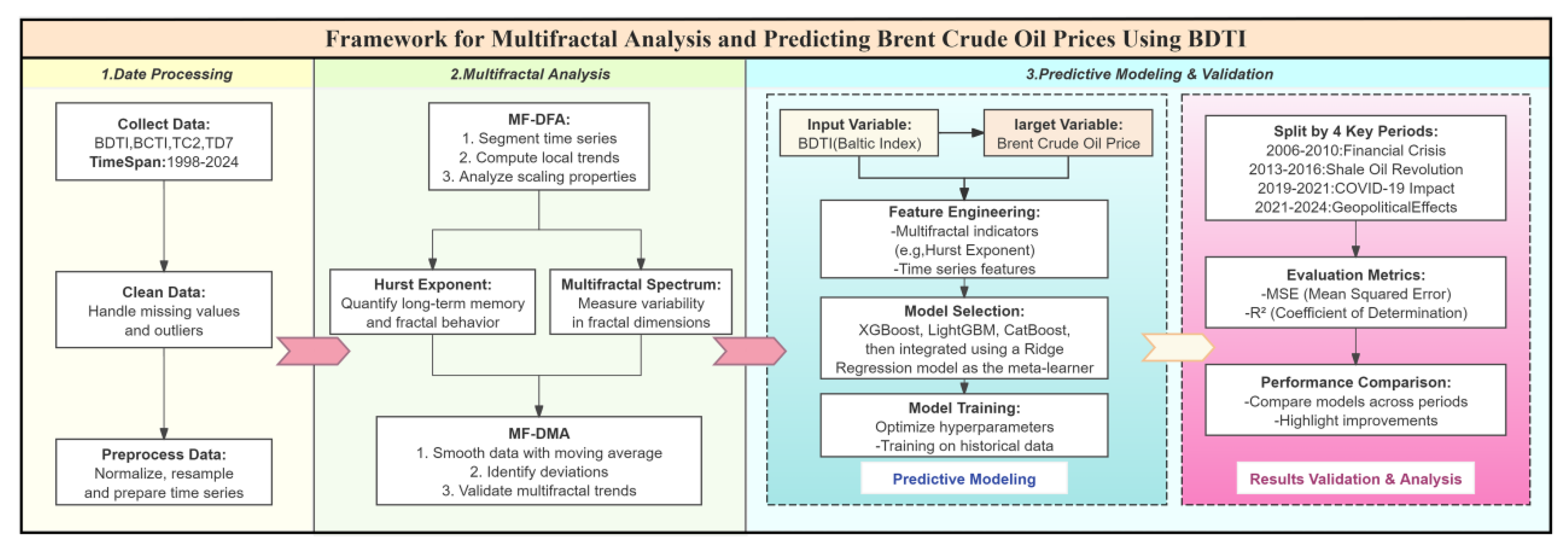

To provide a clear visual representation of the methodology, the following flowchart outlines the framework for multifractal analysis and predictive modeling using the Baltic Dirty Tanker Index (BDTI) and its application to Brent crude oil price prediction. This framework includes three key components: data processing, multifractal analysis, and predictive modeling and validation.

Figure 1.

Framework for Multifractal Analysis and Predictive Brent Crude Oil Prices Using BDTI. This visual representation complements the detailed methodology described above, offering readers an intuitive understanding of the step-by-step process adopted in this study, particularly how multifractal indicators and machine learning models are integrated for predictive modeling across the four structural break periods.

Figure 1.

Framework for Multifractal Analysis and Predictive Brent Crude Oil Prices Using BDTI. This visual representation complements the detailed methodology described above, offering readers an intuitive understanding of the step-by-step process adopted in this study, particularly how multifractal indicators and machine learning models are integrated for predictive modeling across the four structural break periods.

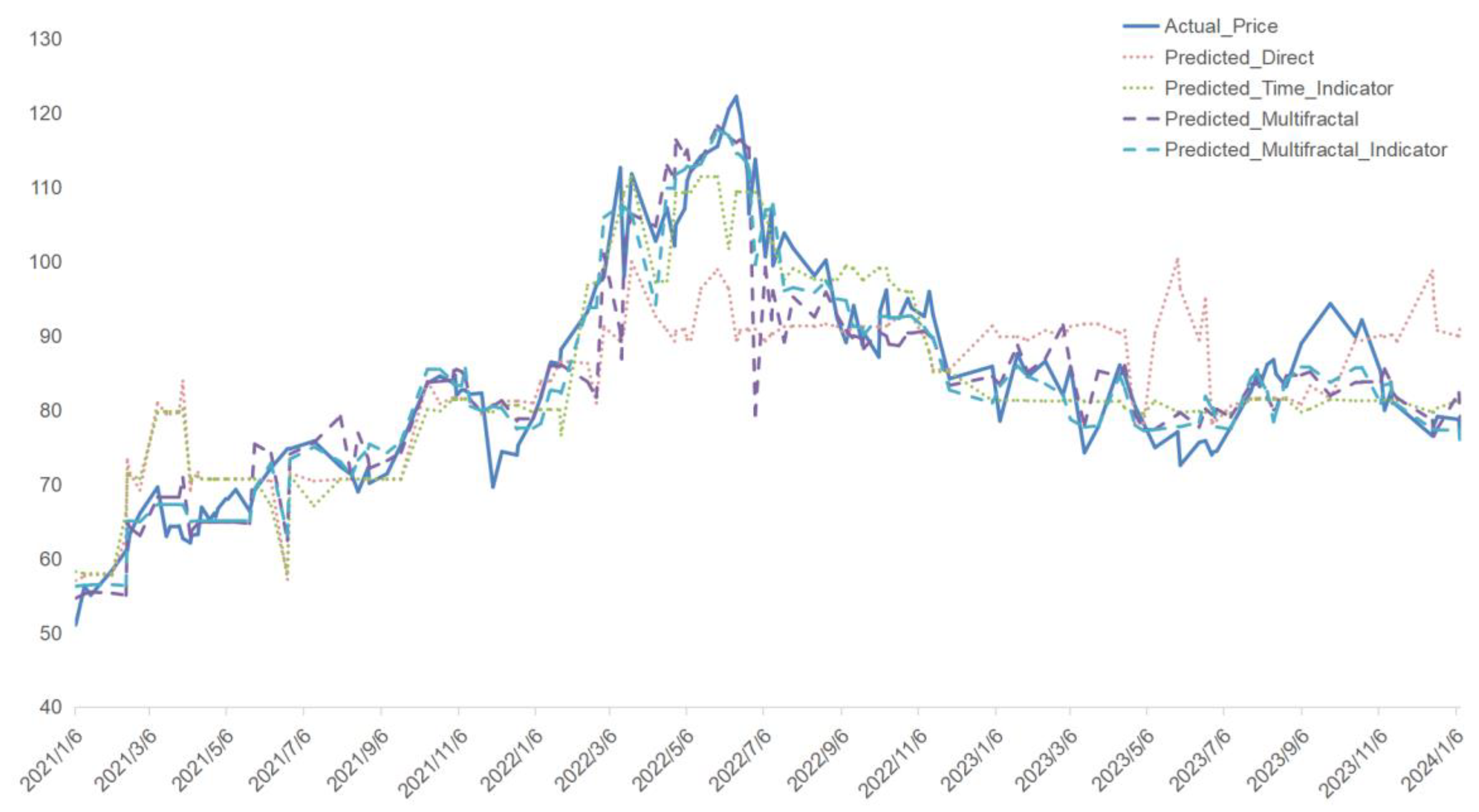

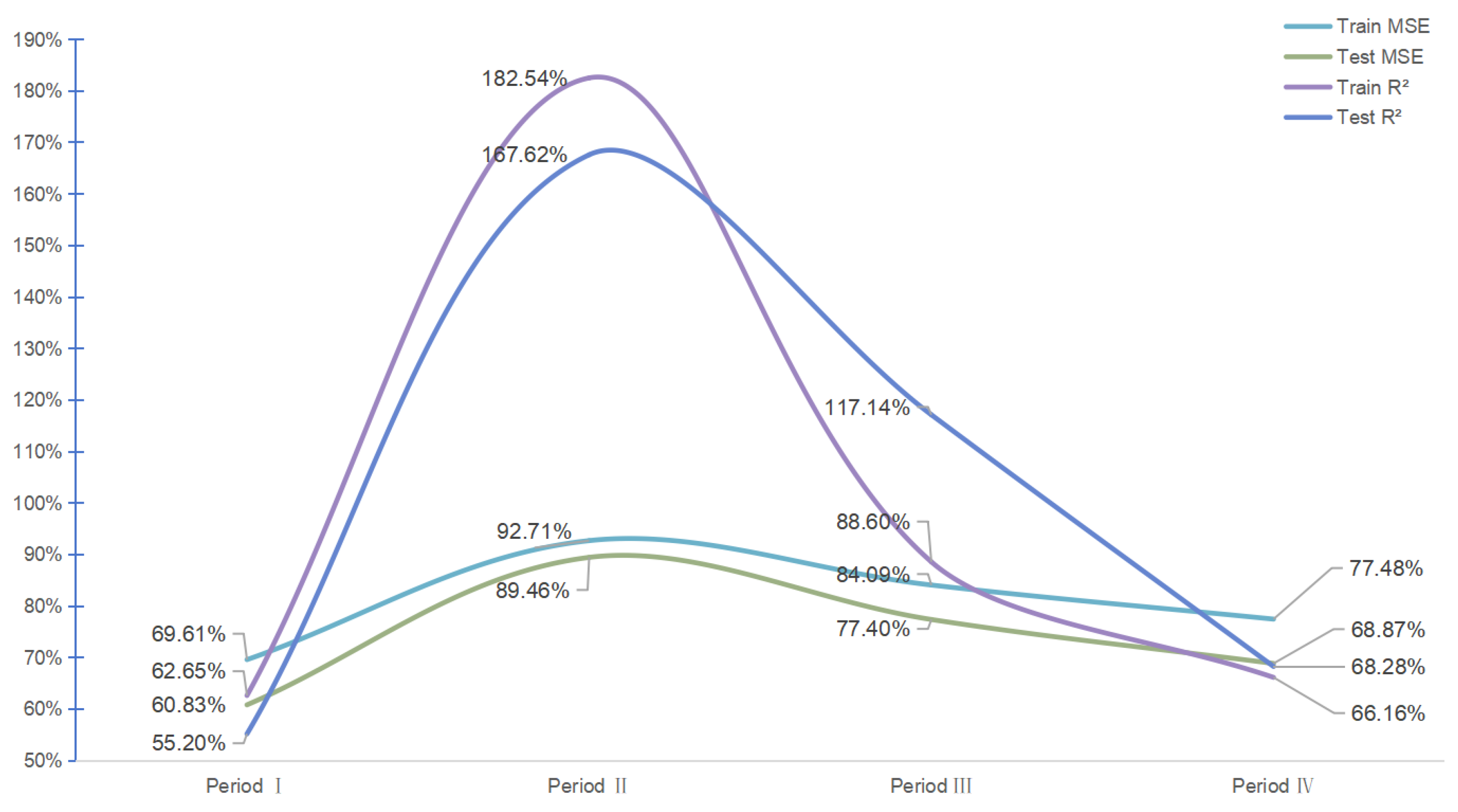

4. Discussion of Results

From the discussion, one may conclude that this study successfully unravels the multifaceted complexity of the Baltic Tanker Freight market using multifractal analysis techniques and advanced machine learning models. By integrating the Baltic Dirty Tanker Index (BDTI) as a leading indicator, we demonstrate that freight rates can effectively predict Brent oil prices, particularly during heightened market volatility caused by global crises such as the 2008 Financial Crisis, the 2014 Shale Oil Revolution, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Russia-Ukraine conflict. The findings reveal that multifractal characteristics, such as the generalized Hurst exponent and multifractal spectrum, significantly enhance the predictive accuracy of the models, outperforming traditional approaches that rely solely on linear or unidirectional relationships [

7,

9]. Moreover, the stacking regression framework combining XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost, and Ridge Regression validates the robustness of the proposed methodology, aligning closely with contemporary machine learning advancements [

26,

62,

63,

64]. These results provide actionable insights for policymakers, energy companies, and investors, emphasizing the utility of multifractal analysis in managing systemic risks and navigating energy market volatility [

4,

6].

Comparison of the findings with those of other studies confirms the progressive advantage of integrating multifractal analysis with predictive modeling. Previous research has largely focused on forecasting freight rates based on oil prices, reflecting a conventional perspective of oil price-driven costs in shipping [

17,

18]. However, this study advances the discussion by demonstrating that BDTI provides valuable information for predicting Brent oil prices. This finding aligns with recent studies that highlight the sensitivity of freight rates to immediate supply-demand imbalances and macroeconomic shocks [

74]. Unlike earlier studies that overlooked nonlinear dynamics, the inclusion of multifractal features offers a substantial improvement in capturing complex market behaviors. Thus, the predictive performance achieved in this study reflects methodological progress compared to traditional econometric models or linear approaches, which often fail under volatile conditions [

12,

18].

Nevertheless, there are limitations to the current study that warrant consideration. First, while the study leverages BDTI and multifractal features, it does not account for other exogenous factors such as regional economic policies, environmental regulations, or vessel fleet dynamics, which may further influence oil and freight markets [

8]. Second, the analysis is constrained to the Baltic indices (BDTI and BCTI), which, although significant, may not fully represent global tanker market dynamics. Third, the use of historical data assumes that past patterns remain valid predictors for future trends, which may not hold during unprecedented disruptions or structural market changes [

19,

33]. Finally, the reliance on machine learning models, though effective, introduces the risk of overfitting, particularly when applied to smaller or less volatile datasets [

51,

52].

To address these limitations, several potential solutions can be proposed. Expanding the dataset to include additional variables such as global trade volumes, bunker fuel prices, or geopolitical risk indices may enhance the robustness of the models [

19,

21]. Incorporating real-time data streams or satellite-based tracking of vessel movements could also improve predictive accuracy [

52,

53]. Furthermore, the application of hybrid methods, combining deep learning approaches like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks with multifractal analysis, could address the limitations of traditional machine learning models.

Research questions that could be asked include whether integrating additional market indicators, such as energy derivatives or macroeconomic indicators, could further refine predictive outcomes [

14]. One important future direction of this research is to explore the interplay between multifractality and emerging market phenomena, such as carbon emissions trading and the adoption of alternative fuels in shipping. Moreover, investigating the applicability of multifractal analysis in other energy markets, such as natural gas or LNG freight rates, may provide deeper insights into the broader dynamics of energy transportation [

16,

19]. These experimental research results will hopefully serve as useful feedback information for future iterations of predictive frameworks.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the significant potential of multifractal analysis and machine learning in accurately forecasting energy prices during periods of high volatility. The findings not only advance the theoretical understanding of tanker freight markets but also provide practical tools for stakeholders to manage uncertainty and enhance decision-making. By successfully integrating multifractal features and advanced predictive models, this study offers a robust framework that can serve as a foundation for future research. Moving forward, further refinements and broader applications of the proposed methodology may uncover additional insights into the intricate relationships shaping global energy markets, paving the way for more resilient and adaptive forecasting strategies.

5. Conclusions

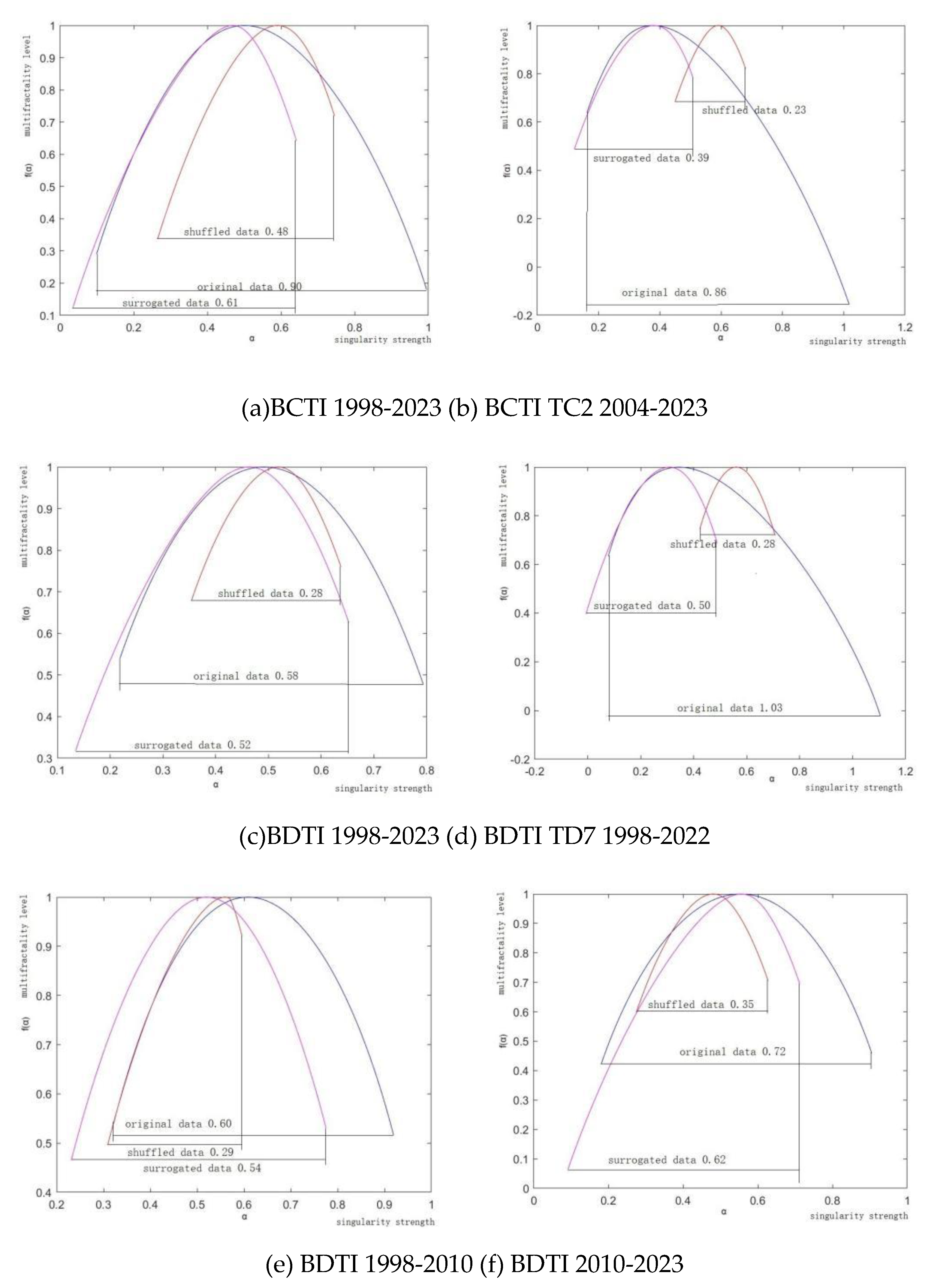

This study utilizes MF-DMA methodology to unravel the multifaceted nature of the Baltic Tanker freight market. Initial findings suggest an overarching multifractal nature within the market, with total multifractality reaching up to 0.90 in the Clean Tankers market. This complexity arises partly from a fat-tailed probability distribution (0.48) and non-linear correlations (0.29), indicating sophisticated temporal organization and inherent volatility as core components of market behavior. A closer examination of a specific route (TC2, 37,000-tonnage) shows that the market retains its multifractal attributes, albeit with reduced magnitudes upon data manipulation. This consistent reduction in multifractality values—evident upon shuffling and surrogating—reinforces the significant contribution of temporal arrangement to the market's complex structure. The world clean tanker market reflects a tight supply-demand balance, with freight rates fluctuating significantly in response to external changes.

In the case of the Dirty Tankers market, the study highlights moderate complexity, with an original multifractality value of 0.58, diminishing under surrogate and shuffled scenarios. This suggests that chronological sequencing is crucial for preserving multifractal properties in this segment. This assertion is further substantiated by focusing on specific routes like TD7 (80,000-tonnage), where multifractality peaks at 1.03 but declines markedly when temporal and structural correlations are disrupted.

The transition in multifractal dynamics between 1998–2010 and 2010–2024 reflects a shift from crisis-induced market behaviors to diversified and complex dynamics influenced by technological advancements, regulatory changes, and environmental policies.

Building on these findings, the study proposes a novel predictive framework that integrates the Baltic Dirty Tanker Index (BDTI), multifractal features, and crisis period indicators to forecast Brent oil prices during periods of heightened volatility. An analysis of four major global events—the 2008 Financial Crisis, the 2014 Shale Oil Revolution, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Russia-Ukraine conflict—illustrates how external factors influence market dynamics and energy prices. The advanced machine learning models employed, including stacking regression with XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost, and Ridge Regression, enhance the robustness and reliability of predictions. These methods highlight the potential of freight rates as leading indicators for energy markets, providing actionable insights for policymakers and market participants.

In conclusion, this study combines multifractal analysis and predictive modeling to provide a comprehensive framework for understanding and navigating the complexities of the Baltic Tanker freight market. By revealing the evolving multifractal dynamics and demonstrating the predictive power of freight rates, the research underscores the importance of integrating multifractal characteristics into forecasting models. The findings offer practical implications for strategic decision-making, operational resilience, and risk management in the shipping and energy industries. Future studies should build on this framework by incorporating additional datasets, refining predictive algorithms, and exploring the interplay between multifractality and other market indicators to further enhance prediction accuracy and application scope.