Submitted:

11 February 2025

Posted:

13 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Prelude

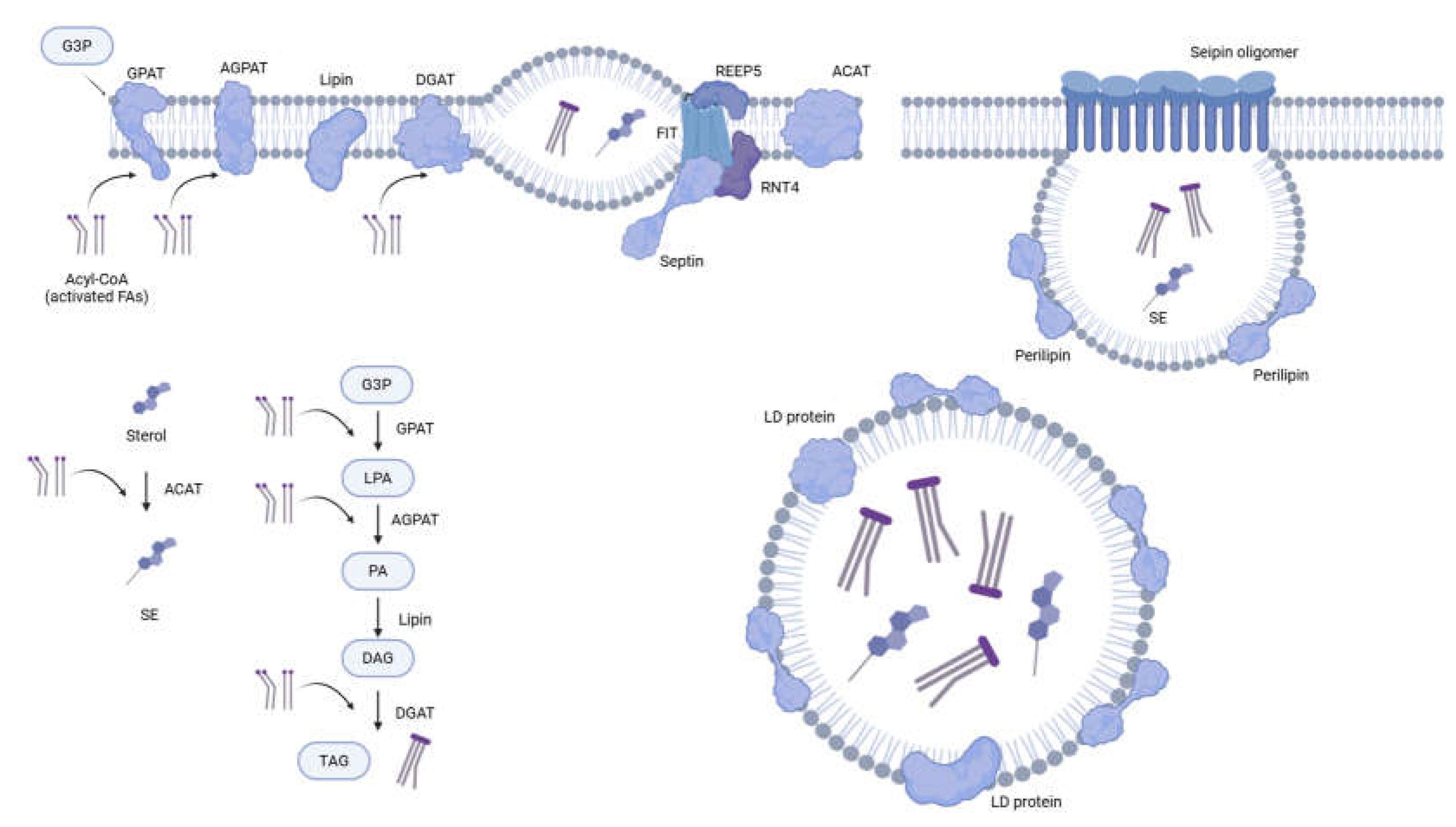

LD metabolism

A. Anabolism

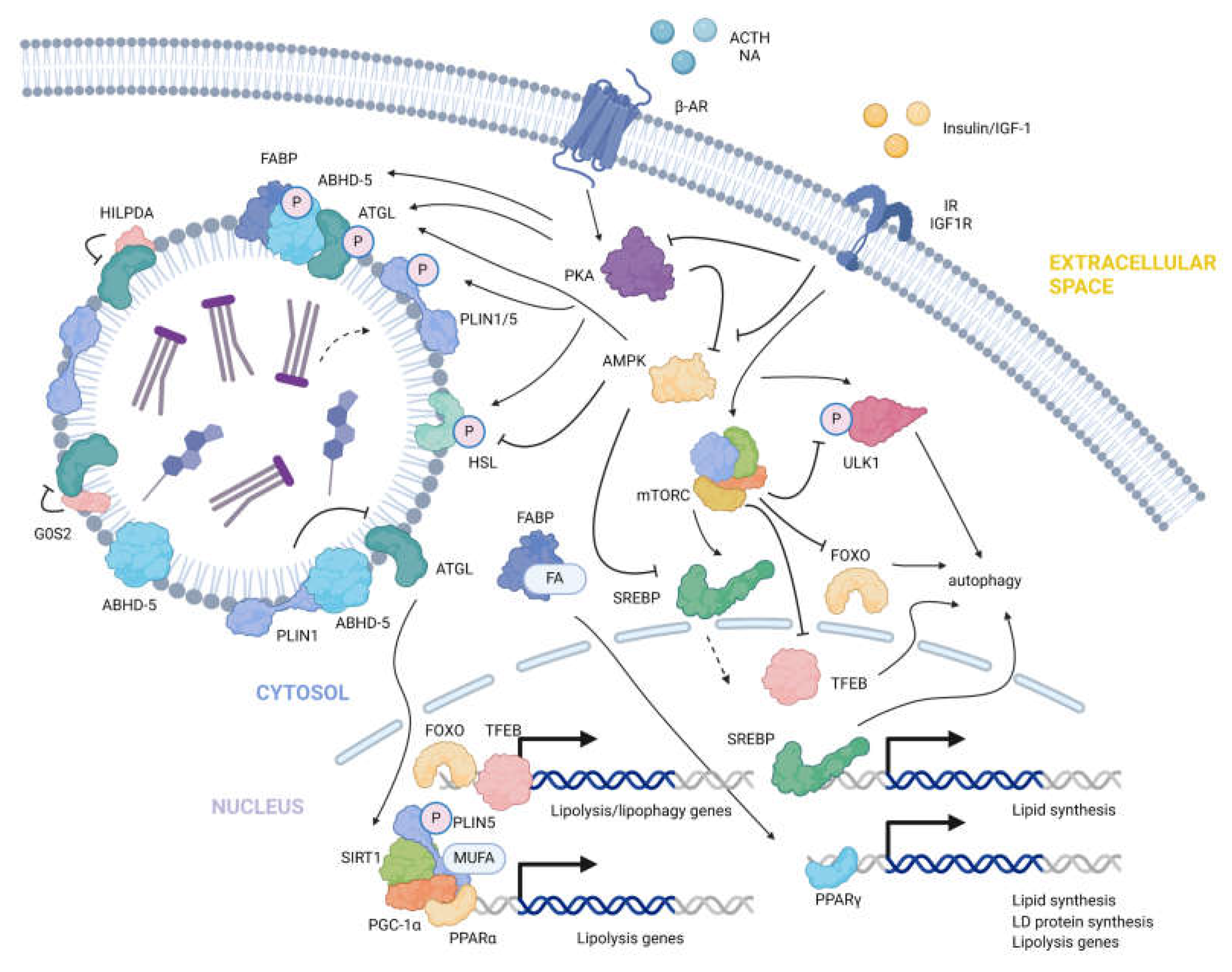

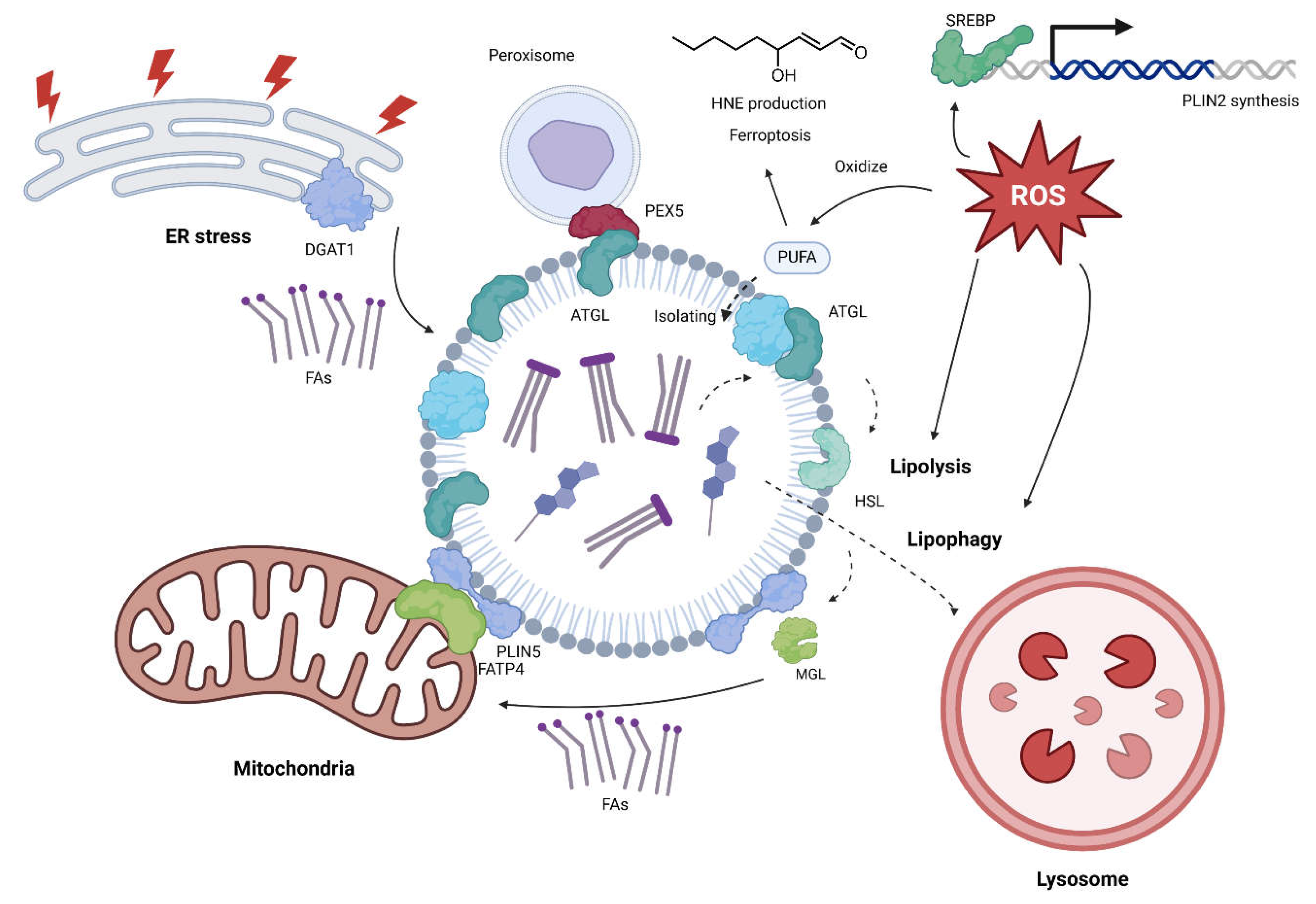

B. Catabolism

Lipolysis

Lipophagy

Additional regulators of LD metabolism

LD functions

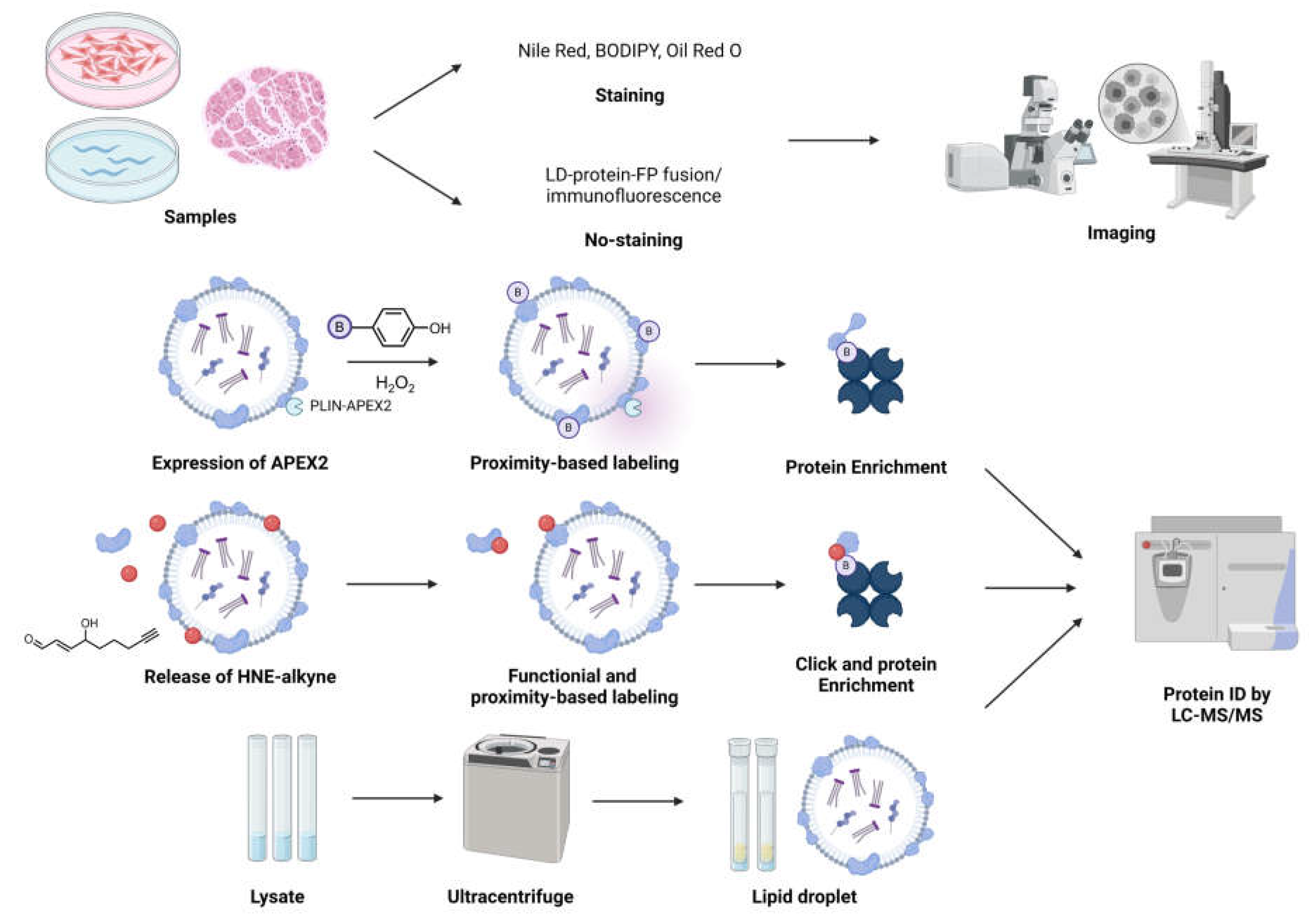

Approaches to perturb and probe LDs, regulation, and functions

B. Proteomics-based strategies to ID LD-associated proteins

Outlook

Acknowledgments

References

- Olzmann, J. A.; Carvalho, P. Dynamics and functions of lipid droplets. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2019, 20, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadi, P. U.; Gu, H. M.; Yin, K.; Jiang, X. C.; Zhang, D. W. Editorial: Lipid metabolism and human diseases. Front Physiol 2022, 13, 1072903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadoorian, A.; Du, X.; Yang, H. Lipid droplet biogenesis and functions in health and disease. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2023, 19, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zechner, R.; Madeo, F.; Kratky, D. Cytosolic lipolysis and lipophagy: two sides of the same coin. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2017, 18, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welte, M. A.; Gould, A. P. Lipid droplet functions beyond energy storage. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 2017, 1862, 1260–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiowetz, A. J.; Olzmann, J. A. Lipid droplets and cellular lipid flux. Nature Cell Biology 2024, 26, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Fan, J.; Taylor, D. C.; Ohlrogge, J. B. DGAT1 and PDAT1 acyltransferases have overlapping functions in Arabidopsis triacylglycerol biosynthesis and are essential for normal pollen and seed development. Plant Cell 2009, 21 (12), 3885-3901. DOI: 10.1105/tpc.109.071795. Jin, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Gao, L.; Sun, R.; Chen, L.; Li, D.; Zheng, Y. Characterization and Functional Analysis of a Type 2 Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase (DGAT2) Gene from Oil Palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) Mesocarp in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. Frontiers in Plant Science 2017, 8, Original Research. DOI: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01791.

- Chen, J. E.; Smith, A. G. A look at diacylglycerol acyltransferases (DGATs) in algae. Journal of Biotechnology 2012, 162, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiam, A. R.; Forêt, L. The physics of lipid droplet nucleation, growth and budding. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 2016, 1861, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoni, V.; Khaddaj, R.; Campomanes, P.; Thiam, A. R.; Schneiter, R.; Vanni, S. Pre-existing bilayer stresses modulate triglyceride accumulation in the ER versus lipid droplets. eLife 2021, 10, e62886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben M'barek, K.; Ajjaji, D.; Chorlay, A.; Vanni, S.; Forêt, L.; Thiam, A. R. ER Membrane Phospholipids and Surface Tension Control Cellular Lipid Droplet Formation. Dev Cell 2017, 41, 591–604e597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santinho, A.; Salo, V. T.; Chorlay, A.; Li, S.; Zhou, X.; Omrane, M.; Ikonen, E.; Thiam, A. R. Membrane Curvature Catalyzes Lipid Droplet Assembly. Curr Biol 2020, 30, 2481–2494e2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiam, A. R.; Ikonen, E. Lipid Droplet Nucleation. Trends in Cell Biology 2021, 31, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartwright, B. R.; Goodman, J. M. Seipin: from human disease to molecular mechanism. J Lipid Res 2012, 53, 1042–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhary, V.; Ojha, N.; Golden, A.; Prinz, W. A. A conserved family of proteins facilitates nascent lipid droplet budding from the ER. J Cell Biol 2015, 211, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Yan, B.; Ren, J.; Lyu, R.; Wu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, H.; Hu, J. FIT2 organizes lipid droplet biogenesis with ER tubule-forming proteins and septins. J Cell Biol 2021, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersuker, K.; Olzmann, J. A. Establishing the lipid droplet proteome: Mechanisms of lipid droplet protein targeting and degradation. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 2017, 1862, 1166–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amari, C.; Carletti, M.; Yan, S.; Michaud, M.; Salvaing, J. Lipid droplets degradation mechanisms from microalgae to mammals, a comparative overview. Biochimie 2024, 227, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, C. N.; Horn, P. J.; Case, C. R.; Gidda, S. K.; Zhang, D.; Mullen, R. T.; Dyer, J. M.; Anderson, R. G. W.; Chapman, K. D. Disruption of the <i>Arabidopsis</i> CGI-58 homologue produces Chanarin–Dorfman-like lipid droplet accumulation in plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107, 17833–17838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulovic, M.; Knittelfelder, O.; Cristobal-Sarramian, A.; Kolb, D.; Wolinski, H.; Kohlwein, S. D. The emergence of lipid droplets in yeast: current status and experimental approaches. Current Genetics 2013, 59, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H.; Kong, J.; Jang, J. Y.; Han, J. S.; Ji, Y.; Lee, J.; Kim, J. B. Lipid droplet protein LID-1 mediates ATGL-1-dependent lipolysis during fasting in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Cell Biol 2014, 34, 4165–4176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Klionsky, D. J.; Shen, H.-M. The emerging mechanisms and functions of microautophagy. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2023, 24, 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushik, S.; Cuervo, A. M. Degradation of lipid droplet-associated proteins by chaperone-mediated autophagy facilitates lipolysis. Nat Cell Biol 2015, 17, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S. Y.; Sun, K. S.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, X.; Zheng, X. H.; Tian, S. Y.; Liu, Y. S.; Chen, L.; Gao, X.; Ye, J.; et al. Disruption of Plin5 degradation by CMA causes lipid homeostasis imbalance in NAFLD. Liver International 2020, 40, 2427–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J. L.; Suh, Y.; Cuervo, A. M. Deficient chaperone-mediated autophagy in liver leads to metabolic dysregulation. Cell Metab 2014, 20, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, R. J.; Krueger, E. W.; Weller, S. G.; Johnson, K. M.; Casey, C. A.; Schott, M. B.; McNiven, M. A. Direct lysosome-based autophagy of lipid droplets in hepatocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 32443–32452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grumet, L.; Eichmann, T. O.; Taschler, U.; Zierler, K. A.; Leopold, C.; Moustafa, T.; Radovic, B.; Romauch, M.; Yan, C.; Du, H.; et al. Lysosomal Acid Lipase Hydrolyzes Retinyl Ester and Affects Retinoid Turnover. J Biol Chem 2016, 291, 17977–17987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabner, G. F.; Xie, H.; Schweiger, M.; Zechner, R. Lipolysis: cellular mechanisms for lipid mobilization from fat stores. Nature Metabolism 2021, 3, 1445–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, K. T.; Lee, C. S.; Mun, S. H.; Truong, N. T.; Park, S. K.; Hwang, C. S. N-terminal acetylation and the N-end rule pathway control degradation of the lipid droplet protein PLIN2. J Biol Chem 2019, 294, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Chen, J.; Macwan, V.; Dixon, C. L.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Yu, Y.; Xu, P.; Sun, Q.; Hu, Q.; et al. S-acylation of ATGL is required for lipid droplet homoeostasis in hepatocytes. Nat Metab 2024, 6, 1549–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H. D.; Chen, S. P.; Sun, Y. X.; Xu, S. H.; Wu, L. J. Seipin mutation at glycosylation sites activates autophagy in transfected cells via abnormal large lipid droplets generation. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2015, 36, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utsumi, T.; Hosokawa, T.; Shichita, M.; Nishiue, M.; Iwamoto, N.; Harada, H.; Kiwado, A.; Yano, M.; Otsuka, M.; Moriya, K. ANKRD22 is an N-myristoylated hairpin-like monotopic membrane protein specifically localized to lipid droplets. Scientific Reports 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kory, N.; Farese, R. V., Jr.; Walther, T. C. Targeting Fat: Mechanisms of Protein Localization to Lipid Droplets. Trends Cell Biol 2016, 26, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiegerl, B.; Tavassoli, M.; Smart, H.; Shabits, B. N.; Zaremberg, V.; Athenstaedt, K. Phosphorylation of the lipid droplet localized glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase Gpt2 prevents a futile triacylglycerol cycle in yeast. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 2019, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, T. R.; Sengupta, S. S.; Harris, T. E.; Carmack, A. E.; Kang, S. A.; Balderas, E.; Guertin, D. A.; Madden, K. L.; Carpenter, A. E.; Finck, B. N.; et al. mTOR complex 1 regulates lipin 1 localization to control the SREBP pathway. Cell 2011, 146, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Dagda, R. K.; Zhang, Y. How AMPK and PKA Interplay to Regulate Mitochondrial Function and Survival in Models of Ischemia and Diabetes. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017, 2017, 4353510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emerling, B. M.; Weinberg, F.; Snyder, C.; Burgess, Z.; Mutlu, G. M.; Viollet, B.; Budinger, G. R.; Chandel, N. S. Hypoxic activation of AMPK is dependent on mitochondrial ROS but independent of an increase in AMP/ATP ratio. Free Radic Biol Med 2009, 46, 1386–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallardo-Montejano, V. I.; Saxena, G.; Kusminski, C. M.; Yang, C.; McAfee, J. L.; Hahner, L.; Hoch, K.; Dubinsky, W.; Narkar, V. A.; Bickel, P. E. Nuclear Perilipin 5 integrates lipid droplet lipolysis with PGC-1α/SIRT1-dependent transcriptional regulation of mitochondrial function. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 12723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadria, M.; Layton, A. T. Interactions among mTORC, AMPK and SIRT: a computational model for cell energy balance and metabolism. Cell Communication and Signaling 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricoult, S. J. H.; Manning, B. D. The multifaceted role of mTORC1 in the control of lipid metabolism. EMBO reports 2013, 14 (3), 242-251-251. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/embor.2013.5 (acccessed 2024/10/17). Shimano, H.; Sato, R. SREBP-regulated lipid metabolism: convergent physiology — divergent pathophysiology. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2017, 13 (12), 710-730. DOI: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.91. Cruz, A. L. S.; Barreto, E. d. A.; Fazolini, N. P. B.; Viola, J. P. B.; Bozza, P. T. Lipid droplets: platforms with multiple functions in cancer hallmarks. Cell Death & Disease 2020, 11 (2), 105. DOI: 10.1038/s41419-020-2297-3. Kim, J.; Guan, K.-L. mTOR as a central hub of nutrient signalling and cell growth. Nature Cell Biology 2019, 21 (1), 63-71. DOI: 10.1038/s41556-018-0205-1. Liu, G. Y.; Sabatini, D. M. mTOR at the nexus of nutrition, growth, ageing and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2020, 21 (4), 183-203. DOI: 10.1038/s41580-019-0199-y. Gorga, A.; Rindone, G. M.; Regueira, M.; Pellizzari, E. H.; Camberos, M. C.; Cigorraga, S. B.; Riera, M. F.; Galardo, M. N.; Meroni, S. B. PPARγ activation regulates lipid droplet formation and lactate production in rat Sertoli cells. Cell Tissue Res 2017, 369 (3), 611-624. DOI: 10.1007/s00441-017-2615-y. Li, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wu, S.; Li, F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, X.; Wang, Y.; et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: A key link between lipid metabolism and cancer progression. Clinical Nutrition 2024, 43 (2), 332-345. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2023.12.005.

- Khan, S. A.; Sathyanarayan, A.; Mashek, M. T.; Ong, K. T.; Wollaston-Hayden, E. E.; Mashek, D. G. ATGL-catalyzed lipolysis regulates SIRT1 to control PGC-1α/PPAR-α signaling. Diabetes 2015, 64, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, N. S.; Shaw, N. S.; Vinckenbosch, N.; Liu, P.; Yasmin, R.; Desvergne, B.; Wahli, W.; Noy, N. Selective cooperation between fatty acid binding proteins and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in regulating transcription. Mol Cell Biol 2002, 22, 5114–5127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gong, L.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Tian, M.; Lu, H.; Bu, P.; Yang, J.; Ouyang, C.; et al. Adipose HuR protects against diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Nat Commun 2019, 10 (1), 2375. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-019-10348-0. Liu, C.; Lin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lin, S.; Zhou, J.; Tang, H.; Yi, X.; Ma, Z.; Xia, T.; Jiang, B.; et al. HuR promotes triglyceride synthesis and intestinal fat absorption. Cell Reports 2024, 43 (5), 114238. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114238.

- Krahmer, N.; Farese, R. V., Jr.; Walther, T. C. Balancing the fat: lipid droplets and human disease. EMBO Mol Med 2013, 5, 973–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, A. Y.; Lau, P. W.; Feliciano, D.; Sengupta, P.; Gros, M. A. L.; Cinquin, B.; Larabell, C. A.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J. AMPK and vacuole-associated Atg14p orchestrate μ-lipophagy for energy production and long-term survival under glucose starvation. Elife 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolis, M.; Bond, L. M.; Kampmann, M.; Pulimeno, P.; Chitraju, C.; Jayson, C. B. K.; Vaites, L. P.; Boland, S.; Lai, Z. W.; Gabriel, K. R.; et al. Probing the Global Cellular Responses to Lipotoxicity Caused by Saturated Fatty Acids. Mol Cell 2019, 74 (1), 32-44.e38. DOI: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.01.036. Listenberger, L. L.; Han, X.; Lewis, S. E.; Cases, S.; Farese, R. V., Jr.; Ory, D. S.; Schaffer, J. E. Triglyceride accumulation protects against fatty acid-induced lipotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100 (6), 3077-3082. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0630588100. Song, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhao, K.; Gao, L.; Zhao, J. Cholesterol-induced toxicity: An integrated view of the role of cholesterol in multiple diseases. Cell Metab 2021, 33 (10), 1911-1925. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.09.001.

- Unoki, T.; Akiyama, M.; Kumagai, Y. Nrf2 Activation and Its Coordination with the Protective Defense Systems in Response to Electrophilic Stress. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21 (2). DOI: 10.3390/ijms21020545. Poganik, J. R.; Huang, K. T.; Parvez, S.; Zhao, Y.; Raja, S.; Long, M. J. C.; Aye, Y. Wdr1 and cofilin are necessary mediators of immune-cell-specific apoptosis triggered by Tecfidera. Nat Commun 2021, 12 (1), 5736. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-021-25466-x. Long, M. J.; Parvez, S.; Zhao, Y.; Surya, S. L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Aye, Y. Akt3 is a privileged first responder in isozyme-specific electrophile response. Nat Chem Biol 2017, 13 (3), 333-338. DOI: 10.1038/nchembio.2284.

- Hong, Y.; Boiti, A.; Vallone, D.; Foulkes, N. S. Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling and Oxidative Stress: Transcriptional Regulation and Evolution. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13 (3). DOI: 10.3390/antiox13030312. Liu, L.; Zhang, K.; Sandoval, H.; Yamamoto, S.; Jaiswal, M.; Sanz, E.; Li, Z.; Hui, J.; Graham, B. H.; Quintana, A.; et al. Glial lipid droplets and ROS induced by mitochondrial defects promote neurodegeneration. Cell 2015, 160 (1-2), 177-190. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.019.

- Sekiya, M.; Hiraishi, A.; Touyama, M.; Sakamoto, K. Oxidative stress induced lipid accumulation via SREBP1c activation in HepG2 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2008, 375, 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensaad, K.; Favaro, E.; Lewis, C. A.; Peck, B.; Lord, S.; Collins, J. M.; Pinnick, K. E.; Wigfield, S.; Buffa, F. M.; Li, J. L.; et al. Fatty acid uptake and lipid storage induced by HIF-1α contribute to cell growth and survival after hypoxia-reoxygenation. Cell Rep 2014, 9, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, J.; Jeong, D.-W.; Park, J.-W.; Lee, K.-W.; Fukuda, J.; Chun, Y.-S. Fatty-acid-induced FABP5/HIF-1 reprograms lipid metabolism and enhances the proliferation of liver cancer cells. Communications Biology 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, G.; Wied, S.; Jung, C.; Over, S. Hydrogen peroxide-induced translocation of glycolipid-anchored (c)AMP-hydrolases to lipid droplets mediates inhibition of lipolysis in rat adipocytes. Br J Pharmacol 2008, 154, 901–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, S. A.; Haller, J. F.; Ferrante, T.; Zoeller, R. A.; Corkey, B. E. Reactive oxygen species facilitate translocation of hormone sensitive lipase to the lipid droplet during lipolysis in human differentiated adipocytes. PLoS One 2012, 7 (4), e34904. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034904. Issa, N.; Lachance, G.; Bellmann, K.; Laplante, M.; Stadler, K.; Marette, A. Cytokines promote lipolysis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes through induction of NADPH oxidase 3 expression and superoxide production. J Lipid Res 2018, 59 (12), 2321-2328. DOI: 10.1194/jlr.M086504.

- Bailey, A. P.; Koster, G.; Guillermier, C.; Hirst, E. M.; MacRae, J. I.; Lechene, C. P.; Postle, A. D.; Gould, A. P. Antioxidant Role for Lipid Droplets in a Stem Cell Niche of Drosophila. Cell 2015, 163, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarc, E.; Kump, A.; Malavašič, P.; Eichmann, T. O.; Zimmermann, R.; Petan, T. Lipid droplets induced by secreted phospholipase Aand unsaturated fatty acids protect breast cancer cells from nutrient and lipotoxic stress. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 2018, 1863, 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dierge, E.; Debock, E.; Guilbaud, C.; Corbet, C.; Mignolet, E.; Mignard, L.; Bastien, E.; Dessy, C.; Larondelle, Y.; Feron, O. Peroxidation of n-3 and n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the acidic tumor environment leads to ferroptosis-mediated anticancer effects. Cell Metab 2021, 33, 1701–1715e1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Gu, D.; Li, S.; Shen, C.; Song, Z. Increased 4-hydroxynonenal formation contributes to obesity-related lipolytic activation in adipocytes. PLoS One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Stockwell, B. R.; Conrad, M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2021, 22, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magtanong, L.; Ko, P. J.; To, M.; Cao, J. Y.; Forcina, G. C.; Tarangelo, A.; Ward, C. C.; Cho, K.; Patti, G. J.; Nomura, D. K.; et al. Exogenous Monounsaturated Fatty Acids Promote a Ferroptosis-Resistant Cell State. Cell Chem Biol 2019, 26, 420–432e429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Meng, L.; Han, L.; Jia, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, H.; Kang, R.; Wang, X.; Tang, D.; Dai, E. Lipid storage and lipophagy regulates ferroptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2019, 508, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parvez, S.; Long, M. J. C.; Poganik, J. R.; Aye, Y. Redox Signaling by Reactive Electrophiles and Oxidants. Chemical Reviews 2018, 118, 8798–8888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Tang, J.; Qiu, X.; Nie, X.; Ou, S.; Wu, G.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, J. Ferroptosis: Emerging mechanisms, biological function, and therapeutic potential in cancer and inflammation. Cell Death Discovery 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagan, V. E.; Mao, G.; Qu, F.; Angeli, J. P.; Doll, S.; Croix, C. S.; Dar, H. H.; Liu, B.; Tyurin, V. A.; Ritov, V. B.; et al. Oxidized arachidonic and adrenic PEs navigate cells to ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol 2017, 13, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppula, P.; Zhuang, L.; Gan, B. Cytochrome P450 reductase (POR) as a ferroptosis fuel. Protein Cell 2021, 12 (9), 675-679. DOI: 10.1007/s13238-021-00823-0. Zou, Y.; Li, H.; Graham, E. T.; Deik, A. A.; Eaton, J. K.; Wang, W.; Sandoval-Gomez, G.; Clish, C. B.; Doench, J. G.; Schreiber, S. L. Cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase contributes tophospholipid peroxidation in ferroptosis. Nature Chemical Biology 2020, 16 (3), 302-309. DOI: 10.1038/s41589-020-0472-6.

- Valm, A. M.; Cohen, S.; Legant, W. R.; Melunis, J.; Hershberg, U.; Wait, E.; Cohen, A. R.; Davidson, M. W.; Betzig, E.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J. Applying systems-level spectral imaging and analysis to reveal the organelle interactome. Nature 2017, 546, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Białek, W.; Hryniewicz-Jankowska, A.; Czechowicz, P.; Sławski, J.; Collawn, J. F.; Czogalla, A.; Bartoszewski, R. The lipid side of unfolded protein response. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 2024, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, S.; Yang, L.; Li, P.; Hofmann, O.; Dicker, L.; Hide, W.; Lin, X.; Watkins, S. M.; Ivanov, A. R.; Hotamisligil, G. S. Aberrant lipid metabolism disrupts calcium homeostasis causing liver endoplasmic reticulum stress in obesity. Nature 2011, 473, 528–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, P.; Ron, D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science 2011, 334, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chitraju, C.; Mejhert, N.; Haas, J. T.; Diaz-Ramirez, L. G.; Grueter, C. A.; Imbriglio, J. E.; Pinto, S.; Koliwad, S. K.; Walther, T. C.; Farese, R. V., Jr. Triglyceride Synthesis by DGAT1 Protects Adipocytes from Lipid-Induced ER Stress during Lipolysis. Cell Metab 2017, 26 (2), 407-418.e403. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.07.012. Vevea, J. D.; Garcia, E. J.; Chan, R. B.; Zhou, B.; Schultz, M.; Di Paolo, G.; McCaffery, J. M.; Pon, L. A. Role for Lipid Droplet Biogenesis and Microlipophagy in Adaptation to Lipid Imbalance in Yeast. Dev Cell 2015, 35 (5), 584-599. DOI: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.11.010.

- Miner, G. E.; So, C. M.; Edwards, W.; Ragusa, J. V.; Wine, J. T.; Wong Gutierrez, D.; Airola, M. V.; Herring, L. E.; Coleman, R. A.; Klett, E. L.; et al. PLIN5 interacts with FATP4 at membrane contact sites to promote lipid droplet-to-mitochondria fatty acid transport. Developmental Cell 2023, 58, 1250–1265e1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Q.; Chen, Q.; Ke, S.; Ding, L.; Yang, X.; Rong, P.; Feng, W.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, M.; et al. Rab8a as a mitochondrial receptor for lipid droplets in skeletal muscle. Dev Cell 2023, 58, 289–305e286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhao, M.; He, X.; Xue, R.; Li, D.; Yu, X.; Wang, S.; Zang, W. Acetylcholine reduces palmitate-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis by promoting lipid droplet lipolysis and perilipin 5-mediated lipid droplet-mitochondria interaction. Cell Cycle 2021, 20, 1890–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Tan, X. Y.; Pantopoulos, K.; Xu, J. J.; Zheng, H.; Xu, Y. C.; Song, Y. F.; Luo, Z. miR-20a-5p targeting mfn2-mediated mitochondria-lipid droplet contacts regulated differential changes in hepatic lipid metabolism induced by two Mn sources in yellow catfish. J Hazard Mater 2024, 462, 132749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Lee, S.; Jun, Y.; Lee, C. Structural basis for mitoguardin-2 mediated lipid transport at ER-mitochondrial membrane contact sites. Nat Commun 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jägerström, S.; Polesie, S.; Wickström, Y.; Johansson, B. R.; Schröder, H. D.; Højlund, K.; Boström, P. Lipid droplets interact with mitochondria using SNAP23. Cell Biol Int 2009, 33, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, M.; Sanchez-Martinez, A.; Longo, M.; Suomi, F.; Stenlund, H.; Johansson, A. I.; Ehsan, H.; Salo, V. T.; Montava-Garriga, L.; Naddafi, S.; et al. DGAT1 activity synchronises with mitophagy to protect cells from metabolic rewiring by iron depletion. Embo j 2022, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. B.; Louie, S. M.; Daniele, J. R.; Tran, Q.; Dillin, A.; Zoncu, R.; Nomura, D. K.; Olzmann, J. A. DGAT1-Dependent Lipid Droplet Biogenesis Protects Mitochondrial Function during Starvation-Induced Autophagy. Dev Cell 2017, 42, 9–21e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Ji, Y.; Jeon, Y. G.; Han, J. S.; Han, K. H.; Lee, J. H.; Lee, G.; Jang, H.; Choe, S. S.; Baes, M.; et al. Spatiotemporal contact between peroxisomes and lipid droplets regulates fasting-induced lipolysis via PEX5. Nature Communications 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C. L.; Weigel, A. V.; Ioannou, M. S.; Pasolli, H. A.; Xu, C. S.; Peale, D. R.; Shtengel, G.; Freeman, M.; Hess, H. F.; Blackstone, C.; et al. Spastin tethers lipid droplets to peroxisomes and directs fatty acid trafficking through ESCRT-III. J Cell Biol 2019, 218, 2583–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papsdorf, K.; Miklas, J. W.; Hosseini, A.; Cabruja, M.; Morrow, C. S.; Savini, M.; Yu, Y.; Silva-García, C. G.; Haseley, N. R.; Murphy, L. M.; et al. Lipid droplets and peroxisomes are co-regulated to drive lifespan extension in response to mono-unsaturated fatty acids. Nature Cell Biology 2023, 25, 672–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enkler, L.; Spang, A. Functional interplay of lipid droplets and mitochondria. FEBS Letters 2024, 598, 1235–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Ge, Q.; Ding, M.; Huang, X. A lipid droplet-associated GFP reporter-based screen identifies new fat storage regulators in C. elegans. J Genet Genomics 2014, 41 (5), 305-313. DOI: 10.1016/j.jgg.2014.03.002. Zhang, P.; Na, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Xue, P.; Chen, Y.; Pu, J.; Peng, G.; Huang, X.; Yang, F.; et al. Proteomic study and marker protein identification of Caenorhabditis elegans lipid droplets. Mol Cell Proteomics 2012, 11 (8), 317-328. DOI: 10.1074/mcp.M111.016345.

- Wang, H.; Becuwe, M.; Housden, B. E.; Chitraju, C.; Porras, A. J.; Graham, M. M.; Liu, X. N.; Thiam, A. R.; Savage, D. B.; Agarwal, A. K.; et al. Seipin is required for converting nascent to mature lipid droplets. Elife 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, S.; Delgado, A. C.; Cadilhac, C.; Maillard, V.; Battiston, F.; Igelbüscher, C. M.; De Neck, S.; Magrinelli, E.; Jabaudon, D.; Telley, L.; et al. A fluorescent perilipin 2 knock-in mouse model reveals a high abundance of lipid droplets in the developing and adult brain. Nat Commun 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhanghao, K.; Liu, W.; Li, M.; Wu, Z.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Shan, C.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Dai, Q.; et al. High-dimensional super-resolution imaging reveals heterogeneity and dynamics of subcellular lipid membranes. Nature Communications 2020, 11 (1), 5890. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-19747-0. Athinarayanan, S.; Fan, Y. Y.; Wang, X.; Callaway, E.; Cai, D.; Chalasani, N.; Chapkin, R. S.; Liu, W. Fatty Acid Desaturase 1 Influences Hepatic Lipid Homeostasis by Modulating the PPARα-FGF21 Axis. Hepatology Communications 2021, 5 (3). Chen, J.; Yue, F.; Kuang, S. Labeling and analyzing lipid droplets in mouse muscle stem cells. STAR Protocols 2022, 3 (4), 101849. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xpro.2022.101849.

- Pino, E. C.; Webster, C. M.; Carr, C. E.; Soukas, A. A. Biochemical and high throughput microscopic assessment of fat mass in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Vis Exp 2013, (73). DOI: 10.3791/50180. Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Tang, Y.; Lin, C.; Cao, Y.; Chen, Y. Mechanism of Pentagalloyl Glucose in Alleviating Fat Accumulation in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Agric Food Chem 2019, 67 (51), 14110-14120. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b06167.

- Greenspan, P.; Mayer, E. P.; Fowler, S. D. Nile red: a selective fluorescent stain for intracellular lipid droplets. J Cell Biol 1985, 100, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenburg, E. E.; Pratt, S. J. P.; Wohlers, L. M.; Lovering, R. M. Use of BODIPY (493/503) to visualize intramuscular lipid droplets in skeletal muscle. J Biomed Biotechnol 2011, 2011, 598358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohsaki, Y.; Shinohara, Y.; Suzuki, M.; Fujimoto, T. A pitfall in using BODIPY dyes to label lipid droplets for fluorescence microscopy. Histochemistry and Cell Biology 2010, 133, 477–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korotkova, D.; Borisyuk, A.; Guihur, A.; Bardyn, M.; Kuttler, F.; Reymond, L.; Schuhmacher, M.; Amen, T. Fluorescent fatty acid conjugates for live cell imaging of peroxisomes. Nature Communications 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, K.; Le, T. T.; Bansal, A.; Narasimhan, S. D.; Cheng, J. X.; Tissenbaum, H. A. A comparative study of fat storage quantitation in nematode Caenorhabditis elegans using label and label-free methods. PLoS One 2010, 5 (9). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012810. O'Rourke, E. J.; Soukas, A. A.; Carr, C. E.; Ruvkun, G. C. elegans major fats are stored in vesicles distinct from lysosome-related organelles. Cell Metab 2009, 10 (5), 430-435. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.10.002.

- Zhao, Y.; Shi, W.; Li, X.; Ma, H. Recent advances in fluorescent probes for lipid droplets. Chemical Communications 2022, 58, 1495–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehlem, A.; Hagberg, C. E.; Muhl, L.; Eriksson, U.; Falkevall, A. Imaging of neutral lipids by oil red O for analyzing the metabolic status in health and disease. Nature Protocols 2013, 8 (6), 1149-1154. DOI: 10.1038/nprot.2013.055. Du, J.; Zhao, L.; Kang, Q.; He, Y.; Bi, Y. An optimized method for Oil Red O staining with the salicylic acid ethanol solution. Adipocyte 2023, 12 (1), 2179334. DOI: 10.1080/21623945.2023.2179334.

- Kraus, N. A.; Ehebauer, F.; Zapp, B.; Rudolphi, B.; Kraus, B. J.; Kraus, D. Quantitative assessment of adipocyte differentiation in cell culture. Adipocyte 2016, 5, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, D.; Bhapkar, A.; Manchandia, B.; Charak, G.; Rathore, S.; Jha, R. M.; Nahak, A.; Mondal, M.; Omrane, M.; Bhaskar, A. K.; et al. ARL8B mediates lipid droplet contact and delivery to lysosomes for lipid remobilization. Cell Reports 2023, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targett-Adams, P.; Chambers, D.; Gledhill, S.; Hope, R. G.; Coy, J. F.; Girod, A.; McLauchlan, J. Live cell analysis and targeting of the lipid droplet-binding adipocyte differentiation-related protein. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 15998–16007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blouin, C. M.; Le Lay, S.; Eberl, A.; Köfeler, H. C.; Guerrera, I. C.; Klein, C.; Le Liepvre, X.; Lasnier, F.; Bourron, O.; Gautier, J.-F.; et al. Lipid droplet analysis in caveolin-deficient adipocytes: alterations in surface phospholipid composition and maturation defects[S]. Journal of Lipid Research 2010, 51, 945–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jüngst, C.; Klein, M.; Zumbusch, A. Long-term live cell microscopy studies of lipid droplet fusion dynamics in adipocytes. J Lipid Res 2013, 54, 3419–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshihara, T.; Maruyama, R.; Shiozaki, S.; Yamamoto, K.; Kato, S.-i.; Nakamura, Y.; Tobita, S. Visualization of Lipid Droplets in Living Cells and Fatty Livers of Mice Based on the Fluorescence of π-Extended Coumarin Using Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy. Analytical Chemistry 2020, 92, 4996–5003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottillo, E. P.; Mladenovic-Lucas, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, L.; Kelly, C. V.; Ortiz, P. A.; Granneman, J. G. A FRET sensor for the real-time detection of long chain acyl-CoAs and synthetic ABHD5 ligands. Cell Rep Methods 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.; Li, M.; Ko, Y. H.; Park, S.; Seo, J.; Park, K. M.; Kim, K. Visualization of lipophagy using a supramolecular FRET pair. Chemical Communications 2021, 57, 12179–12182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farese, R. V., Jr.; Walther, T. C. Lipid droplets finally get a little R-E-S-P-E-C-T. Cell 2009, 139, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Zutphen, T.; Todde, V.; de Boer, R.; Kreim, M.; Hofbauer, H. F.; Wolinski, H.; Veenhuis, M.; van der Klei, I. J.; Kohlwein, S. D. Lipid droplet autophagy in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell 2014, 25, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robenek, H.; Hofnagel, O.; Buers, I.; Robenek, M. J.; Troyer, D.; Severs, N. J. Adipophilin-enriched domains in the ER membrane are sites of lipid droplet biogenesis. Journal of Cell Science 2006, 119, 4215–4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudka, W.; Salo, V. T.; Mahamid, J. Zooming into lipid droplet biology through the lens of electron microscopy. FEBS Letters 2024, 598, 1127–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahamid, J.; Tegunov, D.; Maiser, A.; Arnold, J.; Leonhardt, H.; Plitzko, J. M.; Baumeister, W. Liquid-crystalline phase transitions in lipid droplets are related to cellular states and specific organelle association. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 16866–16871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, T.; Ohsaki, Y.; Suzuki, M.; Cheng, J. Chapter 13 - Imaging Lipid Droplets by Electron Microscopy. In Methods in Cell Biology, Yang, H., Li, P. Eds.; Vol. 116; Academic Press, 2013; pp 227-251.

- Shimobayashi, S. F.; Ohsaki, Y. Universal phase behaviors of intracellular lipid droplets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116 (51), 25440-25445. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1916248116. Rogers, S.; Gui, L.; Kovalenko, A.; Zoni, V.; Carpentier, M.; Ramji, K.; Ben Mbarek, K.; Bacle, A.; Fuchs, P.; Campomanes, P.; et al. Triglyceride lipolysis triggers liquid crystalline phases in lipid droplets and alters the LD proteome. J Cell Biol 2022, 221 (11). DOI: 10.1083/jcb.202205053.

- Slipchenko, M. N.; Le, T. T.; Chen, H.; Cheng, J. X. High-speed vibrational imaging and spectral analysis of lipid bodies by compound Raman microscopy. J Phys Chem B 2009, 113, 7681–7686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Yu, Y.; Folick, A.; Currie, E.; Farese, R. V., Jr.; Tsai, T.-H.; Xie, X. S.; Wang, M. C. In Vivo Metabolic Fingerprinting of Neutral Lipids with Hyperspectral Stimulated Raman Scattering Microscopy. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2014, 136, 8820–8828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran, P. V.; Savini, M.; Folick, A. K.; Hu, K.; Masand, R.; Graham, B. H.; Wang, M. C. Lysosomal Signaling Promotes Longevity by Adjusting Mitochondrial Activity. Developmental Cell 2019, 48, 685–696e685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, R. C.; Hankin, J. A.; Barkley, R. M. Imaging of lipid species by MALDI mass spectrometry. J Lipid Res 2009, 50 Suppl (Suppl), S317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, E. J.; Liao, P. C.; Tan, G.; Vevea, J. D.; Sing, C. N.; Tsang, C. A.; McCaffery, J. M.; Boldogh, I. R.; Pon, L. A. Membrane dynamics and protein targets of lipid droplet microautophagy during ER stress-induced proteostasis in the budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Autophagy 2021, 17, 2363–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, R. S.; Nilsson, T. Rab proteins implicated in lipid storage and mobilization. J Biomed Res 2014, 28, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasineni, K.; McVicker, B. L.; Tuma, D. J.; McNiven, M. A.; Casey, C. A. Rab GTPases associate with isolated lipid droplets (LDs) and show altered content after ethanol administration: potential role in alcohol-impaired LD metabolism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2014, 38, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, S.; Resjö, S.; Gomez, M. F.; James, P.; Holm, C. Characterization of the Lipid Droplet Proteome of a Clonal Insulin-producing β-Cell Line (INS-1 832/13). Journal of Proteome Research 2012, 11, 1264–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S. A.; Wollaston-Hayden, E. E.; Markowski, T. W.; Higgins, L.; Mashek, D. G. Quantitative analysis of the murine lipid droplet-associated proteome during diet-induced hepatic steatosis. J Lipid Res 2015, 56 (12), 2260-2272. DOI: 10.1194/jlr.M056812. Li, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, W.; Hong, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Xu, S.; Shu, Q.; Li, J.; Yang, F.; et al. Comparative proteomics reveals abnormal binding of ATGL and dysferlin on lipid droplets from pressure overload-induced dysfunctional rat hearts. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 19782. DOI: 10.1038/srep19782.

- Lam, S. S.; Martell, J. D.; Kamer, K. J.; Deerinck, T. J.; Ellisman, M. H.; Mootha, V. K.; Ting, A. Y. Directed evolution of APEX2 for electron microscopy and proximity labeling. Nature Methods 2015, 12, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bersuker, K.; Peterson, C. W. H.; To, M.; Sahl, S. J.; Savikhin, V.; Grossman, E. A.; Nomura, D. K.; Olzmann, J. A. A Proximity Labeling Strategy Provides Insights into the Composition and Dynamics of Lipid Droplet Proteomes. Developmental Cell 2018, 44, 97–112e117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Loureiro, Z. Y.; Desai, A.; DeSouza, T.; Li, K.; Wang, H.; Nicoloro, S. M.; Solivan-Rivera, J.; Corvera, S. Regulation of lipolysis by 14-3-3 proteins on human adipocyte lipid droplets. PNAS Nexus 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschallinger, J.; Iram, T.; Zardeneta, M.; Lee, S. E.; Lehallier, B.; Haney, M. S.; Pluvinage, J. V.; Mathur, V.; Hahn, O.; Morgens, D. W.; et al. Lipid-droplet-accumulating microglia represent a dysfunctional and proinflammatory state in the aging brain. Nature Neuroscience 2020, 23 (2), 194-208. DOI: 10.1038/s41593-019-0566-1. Jin, Y.; Tan, Y.; Wu, J.; Ren, Z. Lipid droplets: a cellular organelle vital in cancer cells. Cell Death Discovery 2023, 9 (1), 254. DOI: 10.1038/s41420-023-01493-z.

- Wang, C.; Weerapana, E.; Blewett, M. M.; Cravatt, B. F. A chemoproteomic platform to quantitatively map targets of lipid-derived electrophiles. Nat Methods 2014, 11, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Long, M. J. C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Aye, Y. Ube2V2 Is a Rosetta Stone Bridging Redox and Ubiquitin Codes, Coordinating DNA Damage Responses. ACS Central Science 2018, 4, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Miranda Herrera, P. A.; Chang, D.; Hamelin, R.; Long, M. J. C.; Aye, Y. Function-guided proximity mapping unveils electrophilic-metabolite sensing by proteins not present in their canonical locales. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2022, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Kulkarni, A.; Gao, Y. Q.; Urul, D. A.; Hamelin, R.; Novotny, B.; Long, M. J. C.; Aye, Y. Organ-specific electrophile responsivity mapping in live C. elegans. Cell 2024, 187, 7450–7469e7429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).