Submitted:

12 February 2025

Posted:

12 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

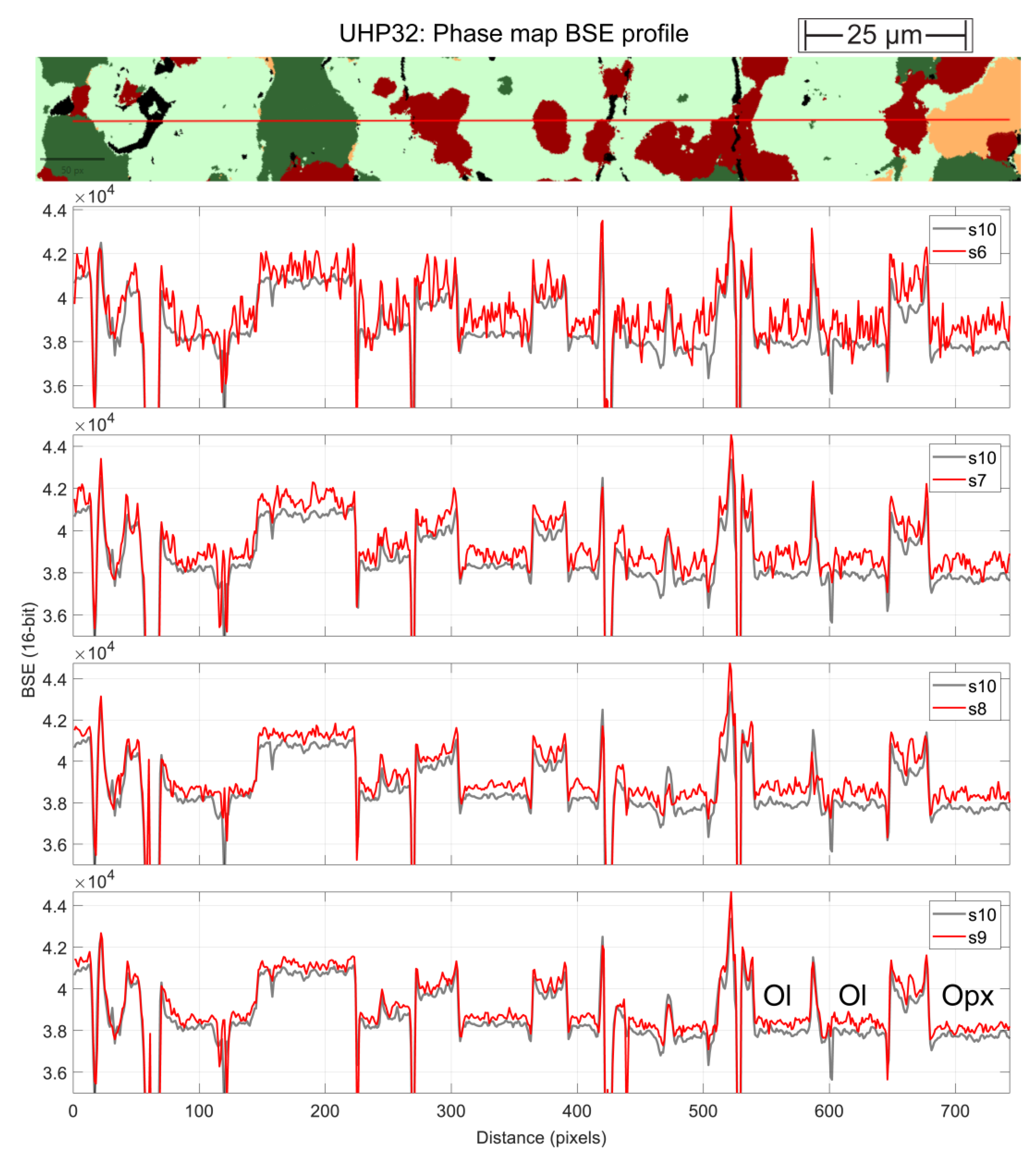

3.1. Evaluating BSE Scan Speeds and EDS Acquisition Settings

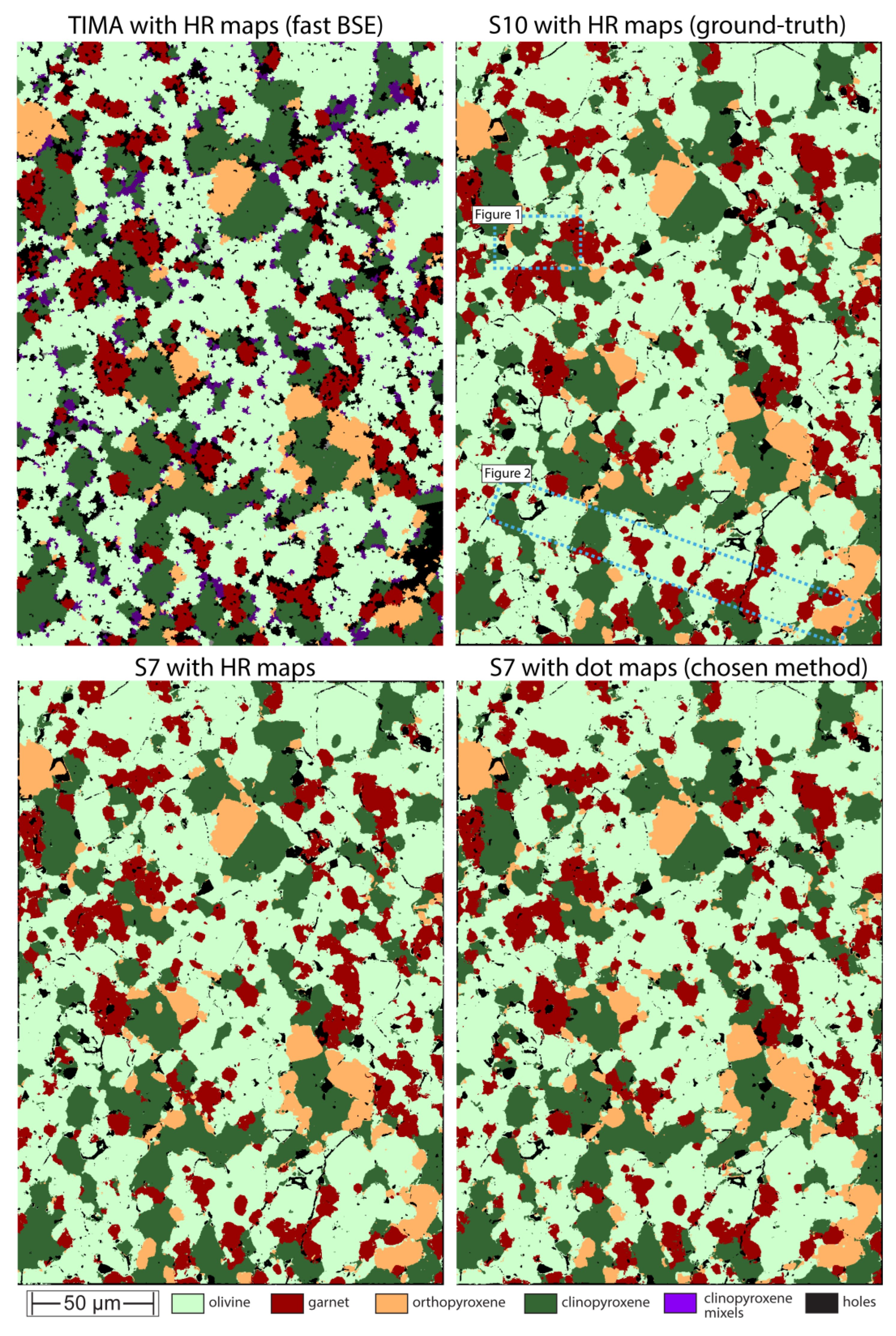

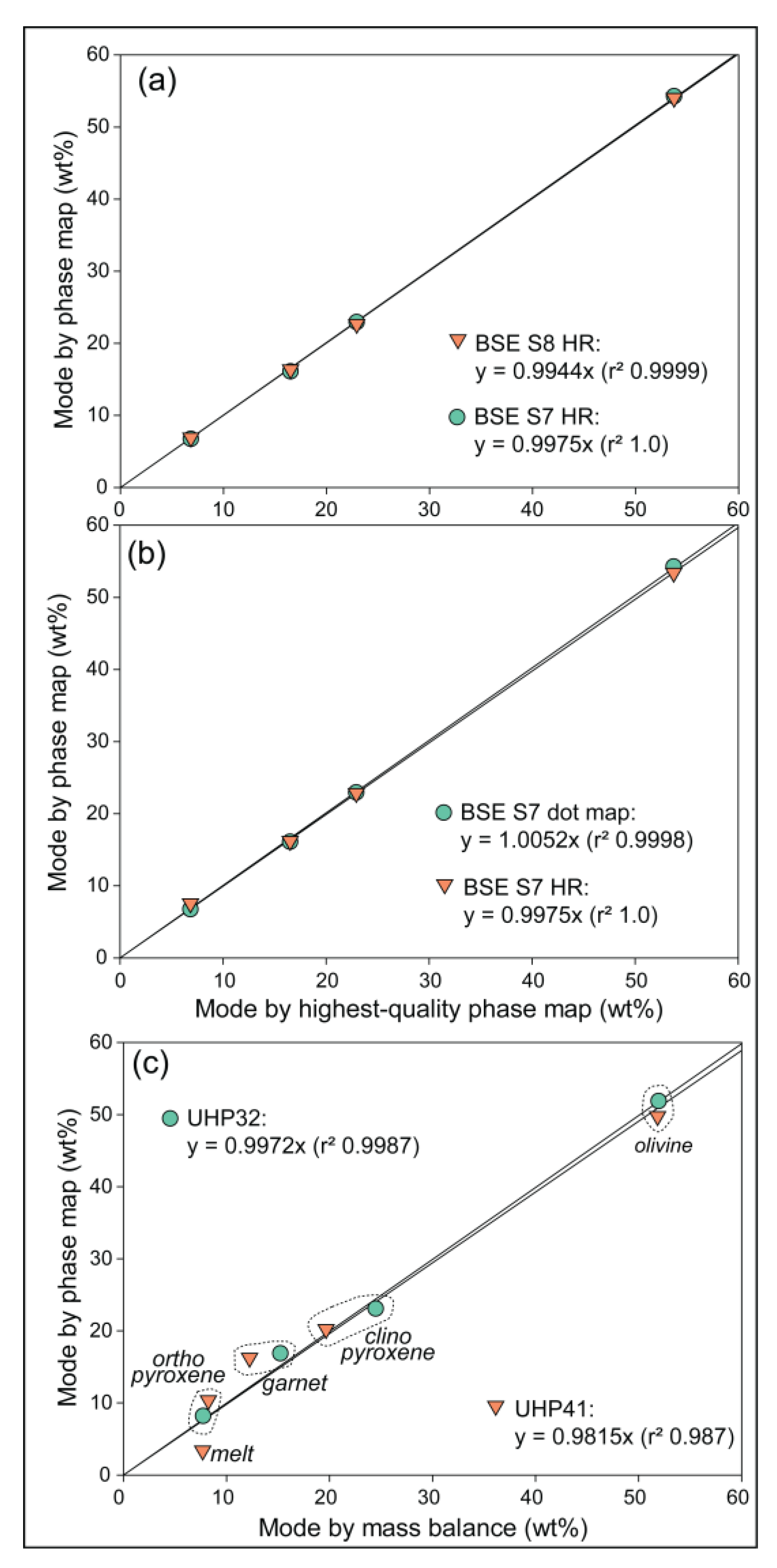

3.2. Phase Maps and Modal Mineralogy for Successful Experiments

3.3. Phase Map for Experiment Which Did Not Experience Thermal Equilibrium

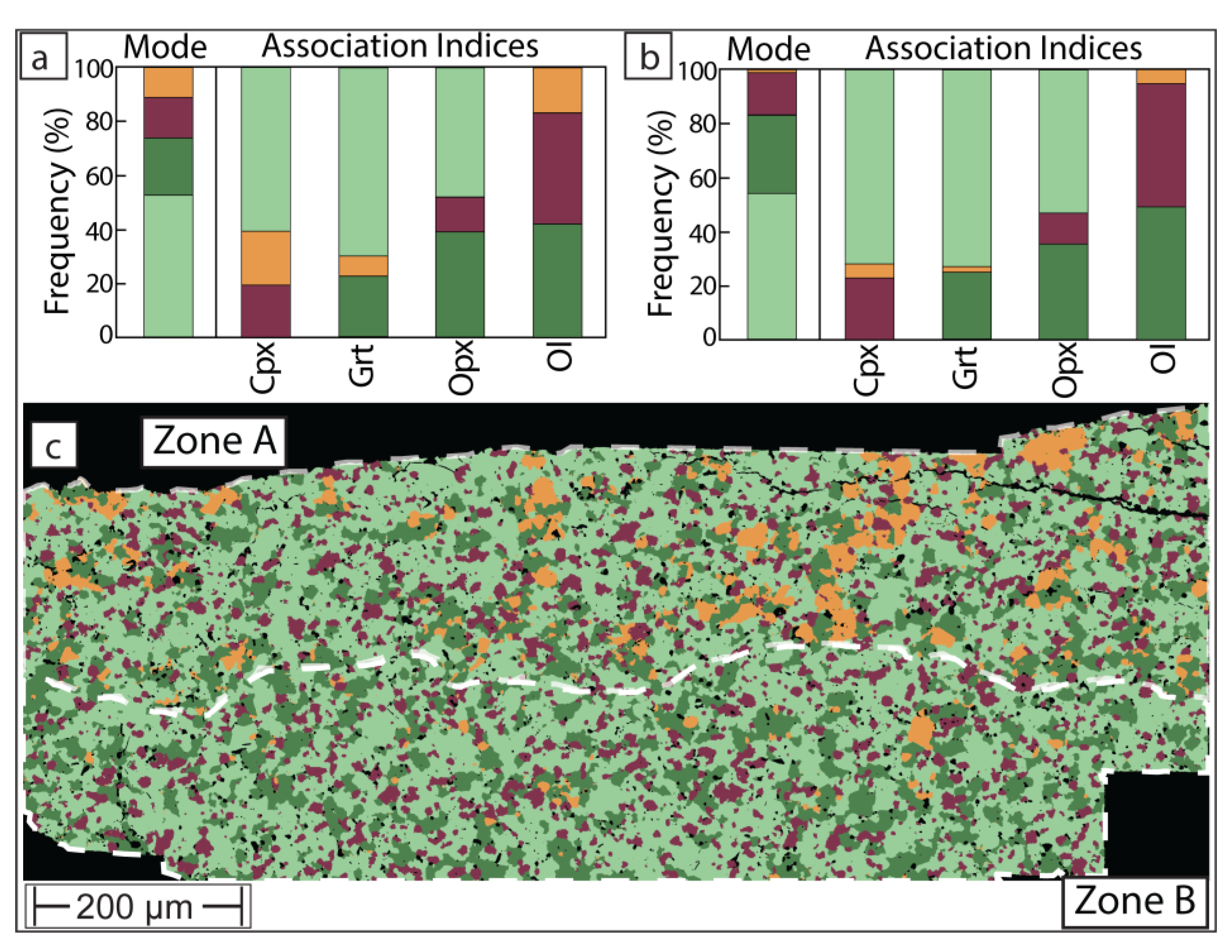

4. Discussion

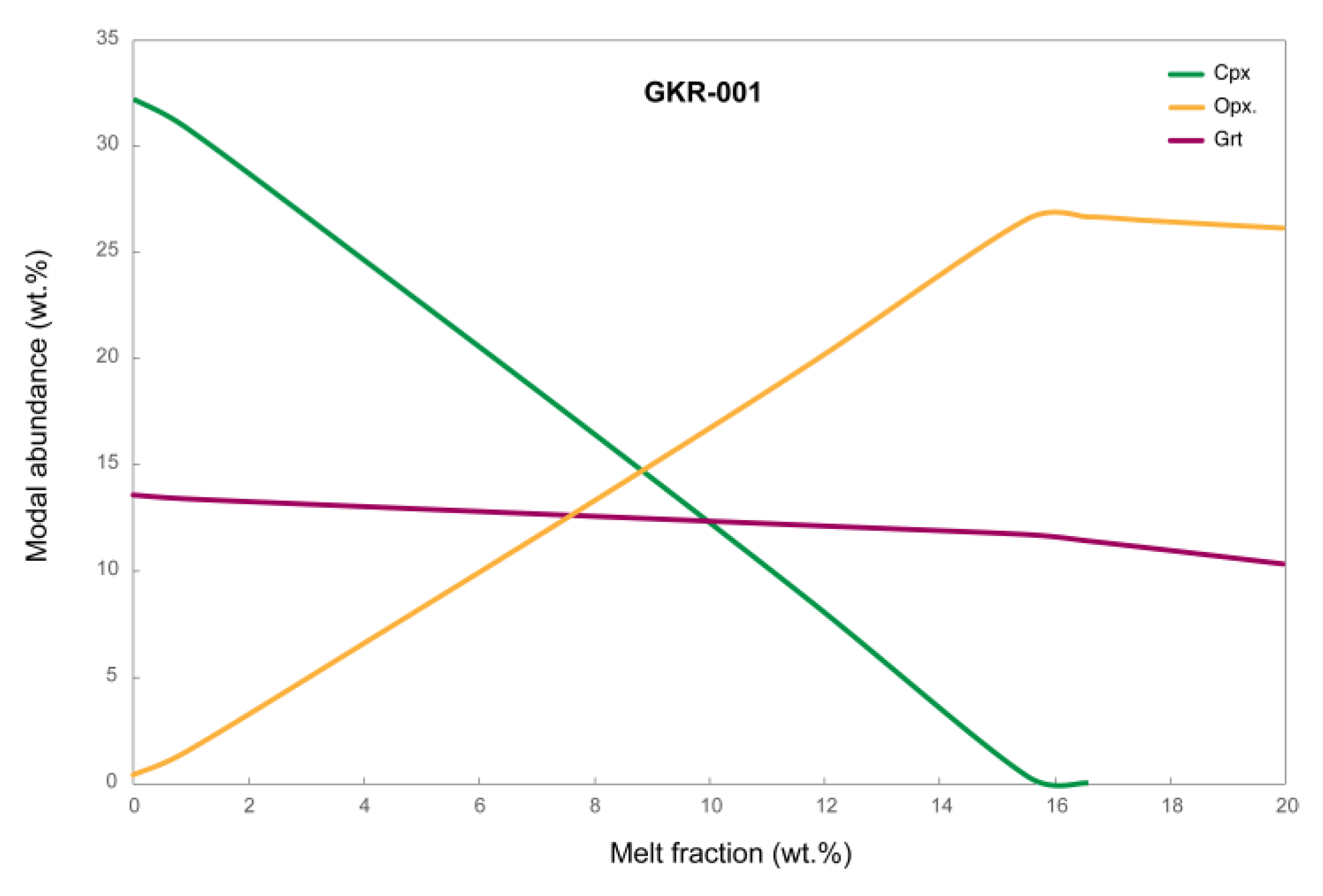

4.1. Insights from Phase Maps of High PT Charges

4.2. Working Towards Optimized Operating Procedures for High-Quality Phase Maps of Experimental Charges

5. Summary

- Due to their small sizes, it is feasible to obtain high quality BSE and EDS imagery for high PT experimental charges, requiring reasonable SEM instrument time (ca. 3 hours). This effort is modest in relation to the production of the experiment and analysis of phase chemistry on the EMPA.

- Phase maps of experimental charges give readers more tangible and complete evidence of phase equilibrium and phase relations than microphotographs of representative areas alone.

- Phase maps generated with commercial automated mineralogy software are suitable to document phase relationships within charges, constrain modes, test for equilibrium, and identify EMPA analysis targets.

- For charges with phases in low abundance, user-assisted phase mapping holds greater promise for obtaining accurate modal abundance estimates than those generated with current proprietary software.

- In the studied sub-solidus charge, the system chemistry calculated from the phase map corresponded very well with the nominal chemistry and demonstrated closed system.

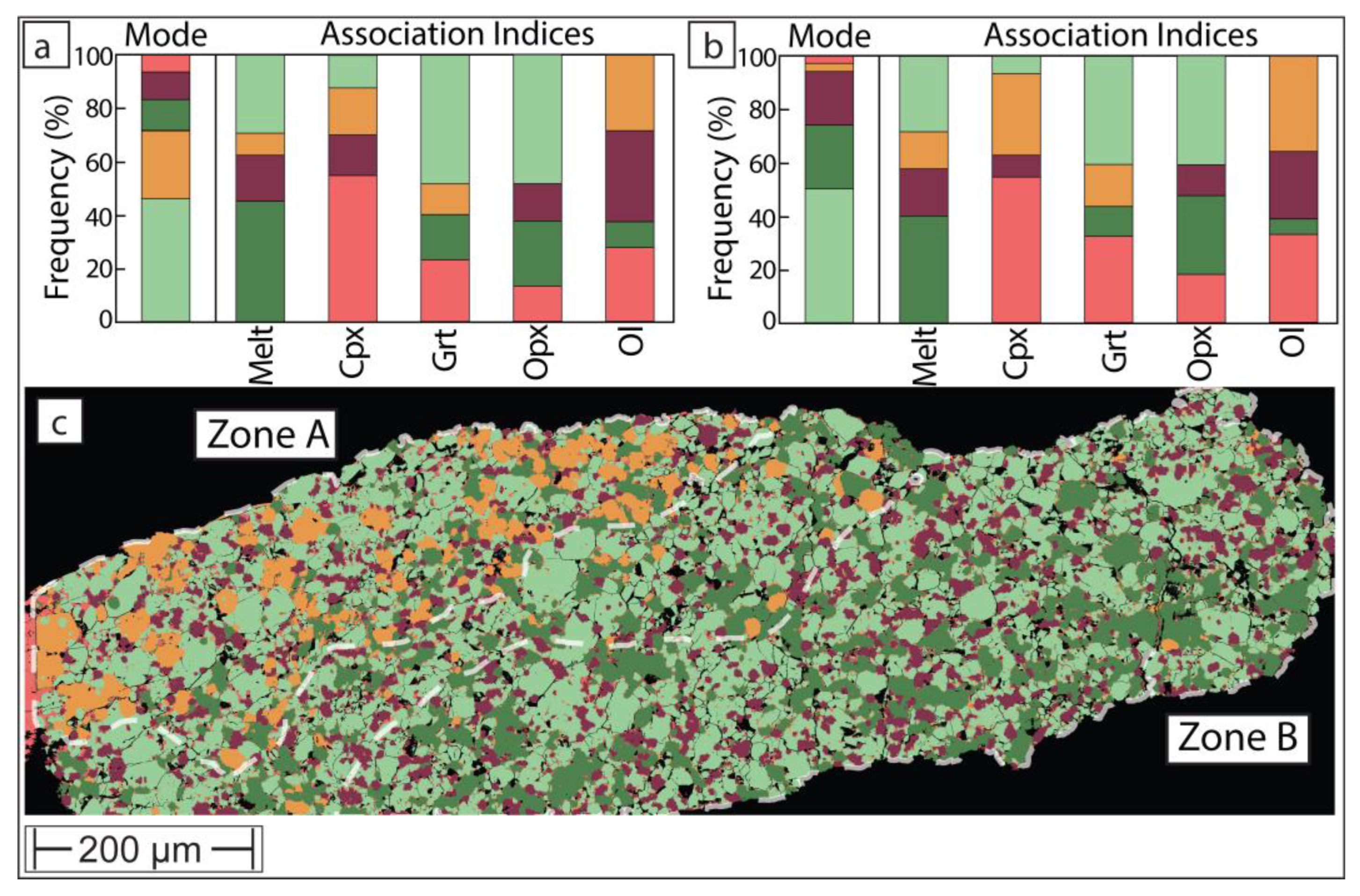

- Mutual pixel neighborhood relationships (quantified as association indices) can be used to verify the plausibility of mass balance-derived reaction equations.

- Phase maps have the potential to add retrospective additional value to historic experimental charges.

- In the future, when combined with high spatial resolution trace element geochemical maps, phase maps have potential to improve counting statistics for low abundance trace elements.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walter, M.J., 1998. Melting of garnet peridotite and the origin of komatiite and depleted lithosphere. Journal of petrology, 39(1), pp.29-60. [CrossRef]

- Canil, D., 1991. Experimental evidence for the exsolution of cratonic peridotite from high-temperature harzburgite. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 106(1-4), pp.64-72. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, E., Shimazaki, T., Tsuzaki, Y. and Yoshida, H., 1993. Melting study of a peridotite KLB-1 to 6.5 GPa, and the origin of basaltic magmas. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A: Physical and Engineering Sciences, 342(1663), pp.105-120. [CrossRef]

- Eggler, D.H., 1979. Experimental igneous petrology. Reviews of Geophysics, 17(4), pp.744-761. [CrossRef]

- Green, T.H., 1980. Island arc and continent-building magmatism—A review of petrogenic models based on experimental petrology and geochemistry. Tectonophysics, 63(1-4), pp.367-385. [CrossRef]

- Newton, R.C. and Manning, C.E., 2010. Role of saline fluids in deep-crustal and upper-mantle metasomatism: insights from experimental studies. Geofluids, 10(1-2), pp.58-72. [CrossRef]

- Ezad, I.S., Blanks, D.E., Foley, S.F., Holwell, D.A., Bennett, J. and Fiorentini, M.L., 2024. Lithospheric hydrous pyroxenites control localisation and Ni endowment of magmatic sulfide deposits. Mineralium Deposita, 59(2), pp.227-236. [CrossRef]

- Ezad, I.S., Saunders, M., Shcheka, S.S., Fiorentini, M.L., Gorojovsky, L.R., Förster, M.W. and Foley, S.F., 2024. Incipient carbonate melting drives metal and sulfur mobilization in the mantle. Science Advances, 10(12), p.eadk5979. [CrossRef]

- Song, W., Xu, C., Veksler, I.V. and Kynicky, J., 2016. Experimental study of REE, Ba, Sr, Mo and W partitioning between carbonatitic melt and aqueous fluid with implications for rare metal mineralization. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 171, pp.1-12. [CrossRef]

- London, D., 1992. The application of experimental petrology to the genesis and crystallization of granitic pegmatites. The Canadian Mineralogist, 30(3), pp.499-540.

- Brey, G.P. and Köhler, T., 1990. Geothermobarometry in four-phase lherzolites II. New thermobarometers, and practical assessment of existing thermobarometers. Journal of Petrology, 31(6), pp.1353-1378.

- Nickel, K.G. and Green, D.H., 1985. Empirical geothermobarometry for garnet peridotites and implications for the nature of the lithosphere, kimberlites and diamonds. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 73(1), pp.158-170. [CrossRef]

- Sudholz, Z.J., Yaxley, G.M., Jaques, A.L. and Brey, G.P., 2021. Experimental recalibration of the Cr-in-clinopyroxene geobarometer: improved precision and reliability above 4.5 GPa. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 176, pp.1-20. [CrossRef]

- Albarede, F. and Provost, A., 1977. Petrological and geochemical mass-balance equations: an algorithm for least-square fitting and general error analysis. Computers & Geosciences, 3(2), pp.309-326. [CrossRef]

- Pertermann, Maik, and Marc M. Hirschmann. "Partial melting experiments on a MORB-like pyroxenite between 2 and 3 GPa: Constraints on the presence of pyroxenite in basalt source regions from solidus location and melting rate." Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 108, no. B2 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Schulz, B., Sandmann, D. and Gilbricht, S., 2020. SEM-based automated mineralogy and its application in geo-and material sciences. Minerals, 10(11), p.1004. [CrossRef]

- Hrstka, T., Gottlieb, P., Skala, R., Breiter, K. and Motl, D., 2018. Automated mineralogy and petrology-applications of TESCAN Integrated Mineral Analyzer (TIMA). Journal of Geosciences, 63(1), pp.47-63. [CrossRef]

- Farmer, N. and O'Neill, H.S.C., 2024. The use of MgO–ZnO ceramics to record pressure and temperature conditions in the piston–cylinder apparatus. European Journal of Mineralogy, 36(3), pp.473-489.

- Riel, N., Kaus, B.J., Green, E.C.R. and Berlie, N., 2022. MAGEMin, an efficient Gibbs energy minimizer: application to igneous systems. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 23(7), p.e2022GC010427. [CrossRef]

- Holland, T.J., Green, E.C. and Powell, R., 2018. Melting of peridotites through to granites: a simple thermodynamic model in the system KNCFMASHTOCr. Journal of Petrology, 59(5), pp.881-900. [CrossRef]

- Cardona, A., Saalfeld, S., Schindelin, J., Arganda-Carreras, I., Preibisch, S., Longair, M., Tomancak, P., Hartenstein, V. and Douglas, R.J., 2012. TrakEM2 software for neural circuit reconstruction. PloS one, 7(6), p.e38011. [CrossRef]

- Bogovic, J.A., Hanslovsky, P., Wong, A. and Saalfeld, S., 2016, April. Robust registration of calcium images by learned contrast synthesis. In 2016 IEEE 13th international symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBI) (pp. 1123-1126). IEEE.

- Schindelin, J., Arganda-Carreras, I., Frise, E., Kaynig, V., Longair, M., Pietzsch, T., Preibisch, S., Rueden, C., Saalfeld, S., Schmid, B. and Tinevez, J.Y., 2012. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nature methods, 9(7), pp.676-682. [CrossRef]

- Bankhead, P., Loughrey, M.B., Fernández, J.A., Dombrowski, Y., McArt, D.G., Dunne, P.D., McQuaid, S., Gray, R.T., Murray, L.J., Coleman, H.G. and James, J.A., 2017. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Scientific reports, 7(1), pp.1-7. [CrossRef]

- Chiaruttini, N., Burri, O., Haub, P., Guiet, R., Sordet-Dessimoz, J. and Seitz, A., 2022. An open-source whole slide image registration workflow at cellular precision using Fiji, QuPath and Elastix. Frontiers in Computer Science, 3, p.780026. [CrossRef]

- Acevedo Zamora, M.A. and Kamber, B.S., 2023. Petrographic microscopy with ray tracing and segmentation from multi-angle polarisation whole-slide images. Minerals, 13(2), p.156. [CrossRef]

- Koch, P.H., 2017. Particle generation for geometallurgical process modeling (Doctoral dissertation, Luleå tekniska universitet).

- Kim, J.J., Ling, F.T., Plattenberger, D.A., Clarens, A.F. and Peters, C.A., 2022. Quantification of mineral reactivity using machine learning interpretation of micro-XRF data. Applied Geochemistry, 136, p.105162. [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, E.L. and Kamber, B.S., 2021. Depth-dependent peridotite-melt interaction and the origin of variable silica in the cratonic mantle. Nature Communications, 12(1), p.1082. [CrossRef]

- Walter, M.J., Sisson, T.W. and Presnall, D.C., 1995. A mass proportion method for calculating melting reactions and application to melting of model upper mantle lherzolite. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 135(1-4), pp.77-90. [CrossRef]

- Pertermann, M. and Hirschmann, M.M., 2003. Anhydrous partial melting experiments on MORB-like eclogite: phase relations, phase compositions and mineral–melt partitioning of major elements at 2–3 GPa. Journal of Petrology, 44(12), pp.2173-2201.

- Lund, C., Lamberg, P. and Lindberg, T., 2015. Development of a geometallurgical framework to quantify mineral textures for process prediction. Minerals engineering, 82, pp.61-77. [CrossRef]

- Lanari, P. and Engi, M., 2017. Local bulk composition effects on metamorphic mineral assemblages. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry, 83(1), pp.55-102. [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, E.L. and Holland, T.J., 2021. A thermodynamic model for the subsolidus evolution and melting of peridotite. Journal of Petrology, 62(1), p.egab012. [CrossRef]

- Lesher, C.E., Pickering-Witter, J., Baxter, G. and Walter, M., 2003. Melting of garnet peridotite: Effects of capsules and thermocouples, and implications for the high-pressure mantle solidus. American Mineralogist, 88(8-9), pp.1181-1189. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A., Zhang, N. and Santos, R.M., 2023. Mineral characterization using scanning electron microscopy (SEM): a review of the fundamentals, advancements, and research directions. Applied Sciences, 13(23), p.12600. [CrossRef]

- Acevedo Zamora, M.A.A., Caulfield, J.T., Laupland, E., Kamber, B.S. and Allen, C.M., 2025, January. Mineral Separate Microanalysis with Intelligent Spot Placement, Manual Edition, and Simulation: Two Correlative Microscopy Prototypes for Relating Zircon Texture, Age, and Geochemistry. In 13th Asia Pacific Microscopy Congress 2025 (APMC13) (p. 280). ScienceOpen.

- Ogliore, R.C., 2021. Acquisition and Online Display of High-Resolution Backscattered Electron and X-Ray Maps of Meteorite Sections. Earth and Space Science, 8(7), p.e2021EA001747. [CrossRef]

- Nowell, M.M. and Wright, S.I., 2004. Phase differentiation via combined EBSD and XEDS. Journal of microscopy, 213(3), pp.296-305. [CrossRef]

- Acevedo Zamora, M.A., Schrank, C.E. and Kamber, B.S., 2024. Using the traditional microscope for mineral grain orientation determination: A prototype image analysis pipeline for optic-axis mapping (POAM). Journal of Microscopy. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H., Zhang, J., Yu, T., Rivers, M., Wang, Y. and Zhao, S., 2015. Crystallographic evidence for simultaneous growth in graphic granite. Gondwana Research, 27(4), pp.1550-1559. [CrossRef]

- Bussweiler, Y., Gervasoni, F., Rittner, M., Berndt, J. and Klemme, S., 2020. Trace element mapping of high-pressure, high-temperature experimental samples with laser ablation ICP time-of-flight mass spectrometry–Illuminating melt-rock reactions in the lithospheric mantle. Lithos, 352, p.105282.

- Acevedo Zamora, M.A.A., Kamber, B.S., Jones, M.W., Schrank, C.E., Ryan, C.G., Howard, D.L., Paterson, D.J., Ubide, T. and Murphy, D.T., 2024. Tracking element-mineral associations with unsupervised learning and dimensionality reduction in chemical and optical image stacks of thin sections. Chemical Geology, 650, p.121997. [CrossRef]

| GKR-001 | UHP32 | ||||

| Ol (32)2 | Opx (17) | Cpx (30) | Grt (23) | ||

| SiO2 | 45.52 | 40.83 (23)3 | 56.36 (22) | 55.03 (23) | 42.37 (28) |

| TiO2 | 0.07 | 0.08 (06) | 0.04 (01) | 0.04 (01) | 0.21 (07) |

| Al2O3 | 4.41 | 0.17 (20) | 2.55 (17) | 2.67 (09) | 22.70 (60) |

| Cr2O3 | 0.32 | 0.09 (02) | 0.28 (02) | 0.30 (03) | 1.29 (23) |

| FeOt | 7.11 | 8.80 (16) | 5.18 (08) | 4.57 (15) | 5.66 (16) |

| MnO | 0.15 | 0.14 (01) | 0.13 (02) | 0.15 (02) | 0.21 (03) |

| MgO | 38.18 | 49.97 (37) | 33.15 (59) | 25.50 (31) | 22.48 (20) |

| NiO | 0.10 | 0.08 (03) | 0.06 (02) | 0.05 (01) | bdl |

| CaO | 3.96 | 0.30 (15) | 2.62 (68) | 11.53 (43) | 5.07 (26) |

| Na2O | 0.09 | 0.03 (00) | 0.07 (02) | 0.24 (01) | bdl |

| K2O | 0.01 | bdl1 | bdl | bdl | bdl |

| Total | 99.90 | 100.39 | 100.40 | 100.05 | 99.99 |

| Mg# | 90.54 | 91.01 | 91.94 | 90.87 | 90.76 |

| Mode (wt.%) Mass balance Phase map |

|

51.95 51.87 |

7.74 8.19 |

24.48 23.07 |

15.23 16.86 |

| UHP40 | |||||

| Ol (22) | Opx (29) | Cpx (29) | Grt (27) | Melt (07)4 | |

| SiO2 | 41.10 (22) | 56.12 (43) | 54.74 (26) | 42.85 (23) | 46.74 (97) |

| TiO2 | bdl | 0.03 (01) | 0.03 (01) | 0.15 (03) | 0.24 (07) |

| Al2O3 | 0.15 (02) | 3.11 (34) | 3.12 (12) | 22.71 (36) | 8.90 (1.0) |

| Cr2O3 | 0.10 (01) | 0.32 (03) | 0.35 (02) | 1.36 (22) | 0.44 (04) |

| FeOt | 8.21 (13) | 4.93 (09) | 4.56 (14) | 5.22 (16) | 11.11 (02) |

| MnO | 0.13 (01) | 0.12 (01) | 0.15 (01) | 0.20 (02) | 0.17 (01) |

| MgO | 50.24 (28) | 32.98 (32) | 26.74 (56) | 22.71 (24) | 18.00 (1.2) |

| NiO | 0.02 (01) | 0.03 (01) | 0.02 (00) | bdl | bdl |

| CaO | 0.28 (01) | 2.56 (18) | 9.79 (69) | 4.95 (22) | 13.95 (07) |

| Na2O | 0.02 (01) | 0.07 (01) | 0.21 (02) | bdl | 0.45 (02) |

| K2O | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | 0.01 (00) |

| Total | 100.32 | 100.24 | 99.69 | 100.15 | 100.00 |

| Mg# | 91.50 | 92.26 | 91.27 | 90.27 | 74.27 |

| Mode (wt.%) Mass balance Phase map |

51.84 49.78 |

8.24 10.37 |

19.66 20.22 |

12.23 16.24 |

7.69 3.38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).