Submitted:

11 February 2025

Posted:

12 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

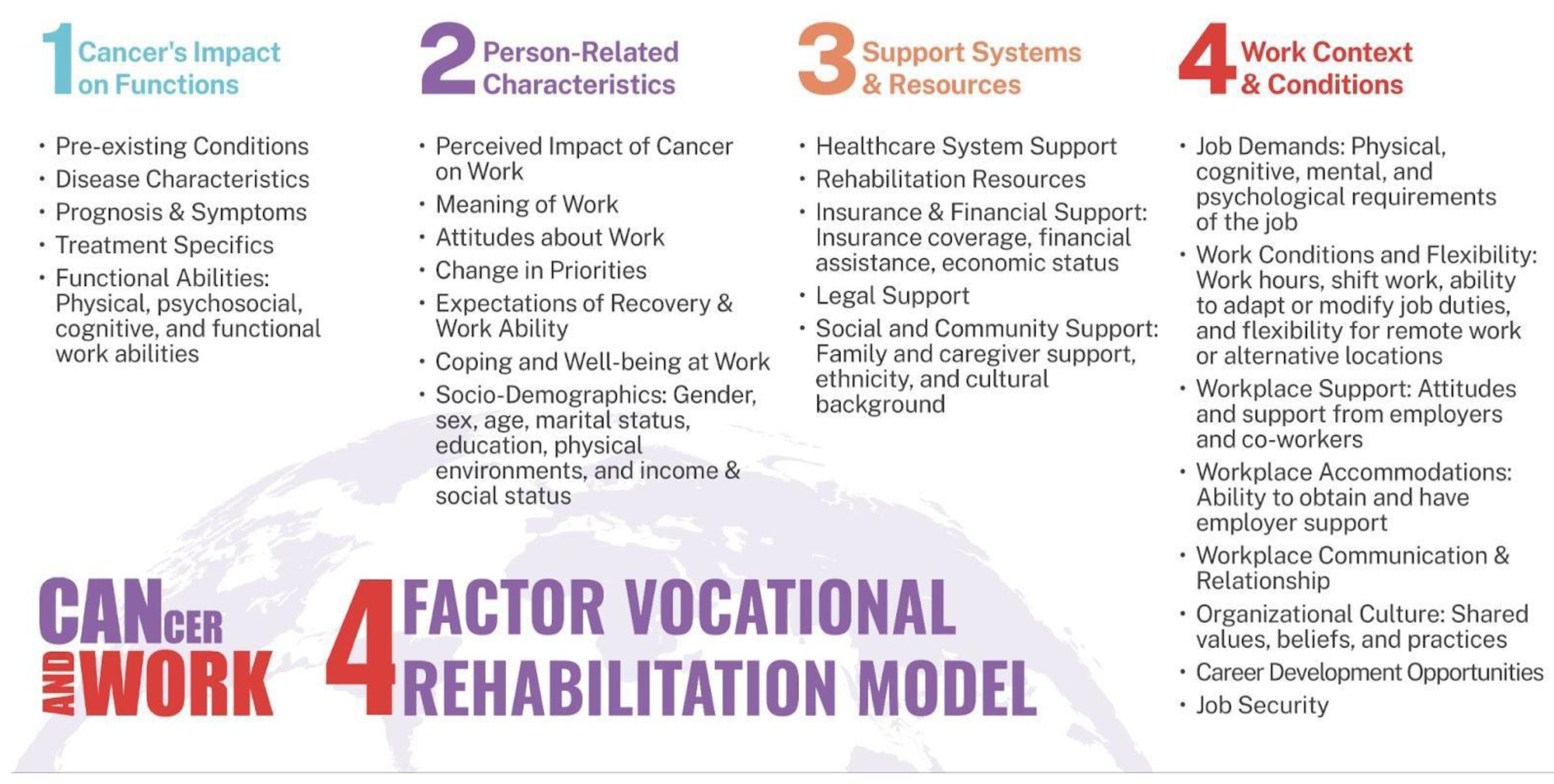

1. Introduction

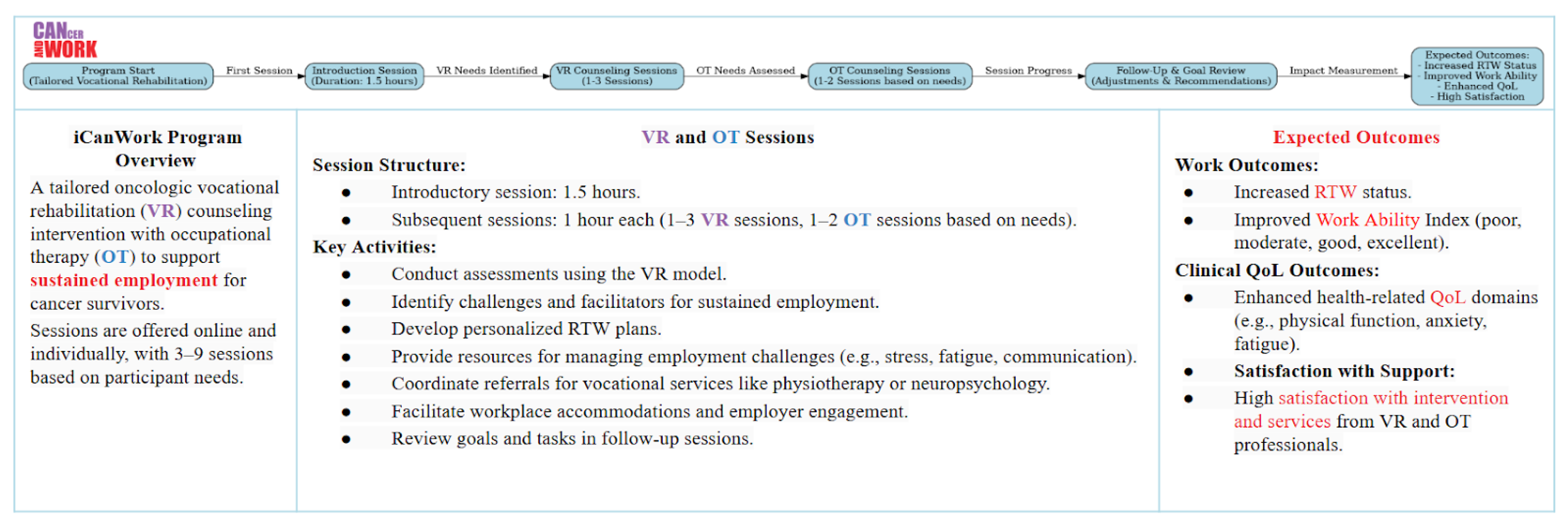

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting, Recruitment, Participants, and Sample Size

2.3. Randomization and Blinding

2.4. Study Groups

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Feasibility

Participant Engagement and Benchmark Adherence

3.3. Acceptability of the iCanWork Intervention

3.4. Preliminary Efficacy

3.4.1. Return to Work Status

3.4.2. Predictors of RTW

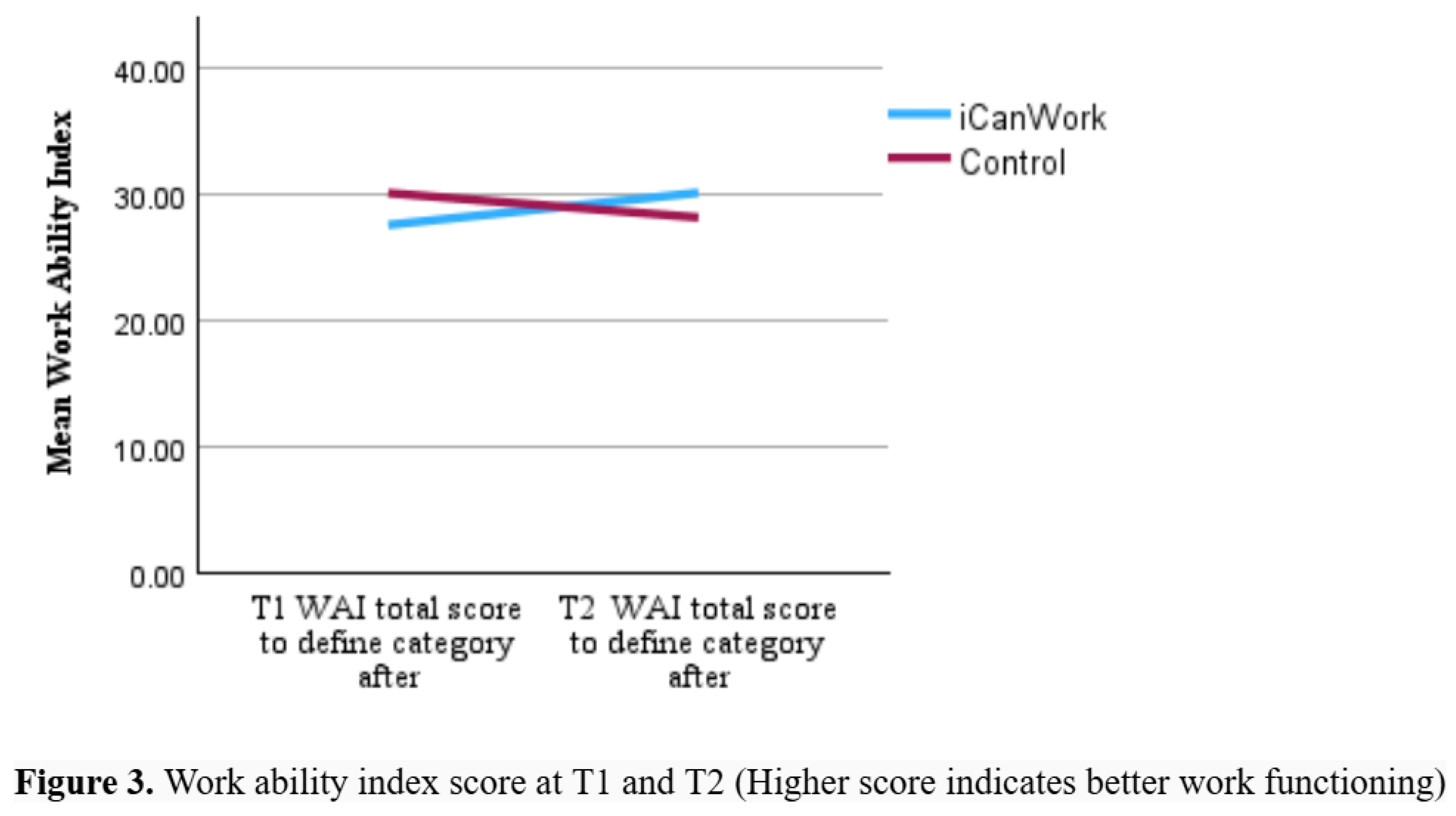

3.5. Work Ability Index (WAI)

3.6. PROPr Domains

3.7. Specific Support Services Utilized Post-Consultation

4. Discussion

Comparison of iCanWork with Existing RTW Support Interventions

Areas for Enhancement for iCanWork Based on Other RTW Interventions

Implications for Future Research & Policy

Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Maheu, C., Parkinson, M., Wong, C., Yashmin, F., and Longpré, C. (2023). Self-Employed Canadians’ Experiences with Cancer and Work: A Qualitative Study. Curr. Oncol. 30, 4586–4602. [CrossRef]

- Sabariego, M., Rosas, M., Piludu, M.A., Acquas, E., Giorgi, O., and Corda, M.G. (2019). Active avoidance learning differentially activates ERK phosphorylation in the primary auditory and visual cortices of Roman high- and low-avoidance rats. Physiol. Behav. 201, 31–41. [CrossRef]

- Skivington, K., Lifshen, M., and Mustard, C. (2016). Implementing a collaborative return-to-work program: Lessons from a qualitative study in a large Canadian healthcare organization. Work 55, 613–624. [CrossRef]

- Fitch, M.I., and Nicoll, I. (2019). Returning to work after cancer: Survivors’, caregivers’, and employers’ perspectives. Psychooncology 28, 792–798.

- de Boer, A.G., Torp, S., Popa, A., Horsboel, T., Zadnik, V., Rottenberg, Y., Bardi, E., Bultmann, U., and Sharp, L. (2020). Long-term work retention after treatment for cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cancer Surviv. 14, 135–150. [CrossRef]

- de Boer, A.G.E.M., and Frings-Dresen, M.H.W. (2009). Employment and the common cancers: return to work of cancer survivors. Occup Med (Lond) 59, 378–380. [CrossRef]

- Short, P.F., Vasey, J.J., and Tunceli, K. (2005). Employment pathways in a large cohort of adult cancer survivors. Cancer 103, 1292–1301. [CrossRef]

- Sumari, M., Mohd Kassim, N., and A.Razak, N.A. (2022). A conceptualisation of resilience among cancer surviving employed women in malaysia. TQR. [CrossRef]

- Molinero, R.G., González, P.R., Zayas, A., and Guil, R. (2019). Resilience and workability among breast cancer survivors. Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology. Revista INFAD de Psicología. 1.

- de Rijk, A., Amir, Z., Cohen, M., Furlan, T., Godderis, L., Knezevic, B., Miglioretti, M., Munir, F., Popa, A.E., Sedlakova, M., et al. (2020). The challenge of return to work in workers with cancer: employer priorities despite variation in social policies related to work and health. J. Cancer Surviv. 14, 188–199. [CrossRef]

- Greidanus, M.A., Tamminga, S.J., de Rijk, A.E., Frings-Dresen, M.H.W., and de Boer, A.G.E.M. (2019). What Employer Actions Are Considered Most Important for the Return to Work of Employees with Cancer? A Delphi Study Among Employees and Employers. J. Occup. Rehabil. 29, 406–422. [CrossRef]

- Awang, H., Tan, L.Y., Mansor, N., Tongkumchum, P., and Eso, M. (2017). Factors related to successful return to work following multidisciplinary rehabilitation. J. Rehabil. Med. 49, 520. [CrossRef]

- Iragorri, N., de Oliveira, C., Fitzgerald, N., and Essue, B. (2021). The indirect cost burden of cancer care in canada: A systematic literature review. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 19, 325–341. [CrossRef]

- Paltrinieri, S., Fugazzaro, S., Bertozzi, L., Bassi, M.C., Pellegrini, M., Vicentini, M., Mazzini, E., and Costi, S. (2018). Return to work in European Cancer survivors: a systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 26, 2983–2994. [CrossRef]

- Canadian Cancer Society (2024). Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee in collaboration with the Canadian Cancer Society, Statistics Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Cancer Statistics: A 2024 special report on the economic impact of cancer in Canada (Toronto, ON, Canada: Canadian Cancer Society).

- de Boer, A.G.E.M., Taskila, T., Ojajärvi, A., van Dijk, F.J.H., and Verbeek, J.H.A.M. (2009). Cancer survivors and unemployment: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. JAMA 301, 753–762.

- de Boer, A.G., Tamminga, S.J., Boschman, J.S., and Hoving, J.L. (2024). Non-medical interventions to enhance return to work for people with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 3, CD007569. [CrossRef]

- Lamore, K., Dubois, T., Rothe, U., Leonardi, M., Girard, I., Manuwald, U., Nazarov, S., Silvaggi, F., Guastafierro, E., Scaratti, C., et al. (2019). Return to work interventions for cancer survivors: A systematic review and a methodological critique. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, M., and Maheu, C. (2019). Cancer and Work . Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal / Revue canadienne de soins infirmiers en oncologie 29, 258–266.

- Maheu, C., Parkinson, M., Oldfield, M., Kita-Stergiou, M., Bernstein, L., Esplen, M.J., Hernandez, C., Zanchetta, M., Singh, M., and on behalf of the Cancer and Work core team members (2016). Cancer and Work. Cancer and Work. Available at: https://www.cancerandwork.ca/ [Accessed August 4, 2021].

- Parkinson, M., and Maheu, C. (2022). Supporting patients surviving cancer with return to work. www.fpon.ca, 4–5, 13. Available at: http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/health-professionals/networks/family-practice-oncology-network/journal-of-family-practice-oncology [Accessed July 23, 2022].

- Maheu, C., Kocum, L., Parkinson, M., Robinson, L., Bernstein, L.J., Zanchetta, M.S., Singh, M., Hernandez, C., Yashmin, F., and Esplen, M.J. (2021). Evaluation of usability and satisfaction of two online tools to guide return to work for cancer survivors on the cancer and work website. J. Occup. Rehabil. [CrossRef]

- Maheu, C., Parkinson, M., Oldfield, M., Kita-Stergiou, M., Bernstein, L., Esplen, M.J., Hernandez, C., Zanchetta, M., Singh, M., and on behalf of the Cancer and Work core team members. Checklist adapted for the Cancer and Work website (2016). Cancer and Work Cognitive Symptoms at Work Checklist. Cancer and Work. Available at: https://www.cancerandwork.ca/ [Accessed February 4, 2025].

- Ottati, A., and Feuerstein, M. (2013). Brief self-report measure of work-related cognitive limitations in breast cancer survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 7, 262–273. [CrossRef]

- Nitkin, P., Parkinson, M., and Schultz, I.Z. (2011). Cancer and work – A Canadian perspective. Canadian Association of Psychological Oncology. Canadian Association of Psycho-Oncology.

- Maheu, C., Parkinson, M., Oldfield, M., Kita-Stergiou, M., Bernstein, L., Hernandez, C., Singh, M., Esplen, M.-J., Zanchetta, M., and on behalf of the Cancer and Work core team members (2020). Development and initial evaluation of the Cancer and Work website to provide a valuable resource to return to work after cancer. Submitted.

- Parkinson, M., and Maheu, C. (2024). Navigating return to work cancer survivor: Supportive strategies and insights. Plans & Trusts 42, 16–22.

- Parkinson, M., and Maheu, C. (2019). Cancer and work. Can. Oncol. Nurs. J. 29, 258–266.

- Tamminga, S.J., de Boer, A.G.E.M., Verbeek, J.H.A.M., and Frings-Dresen, M.H.W. (2010). Return-to-work interventions integrated into cancer care: a systematic review. Occup. Environ. Med. 67, 639–648.

- de Boer, A.G., Taskila, T., Tamminga, S.J., Frings-Dresen, M.H., Feuerstein, M., and Verbeek, J.H. (2011). Interventions to enhance return-to-work for cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev., CD007569.

- de Boer, A.G.E.M., Greidanus, M.A., Dewa, C.S., Duijts, S.F.A., and Tamminga, S.J. (2020). Introduction to special section on: current topics in cancer survivorship and work. J. Cancer Surviv. 14, 101–105. [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, S.M., Chan, C.L., Campbell, M.J., Bond, C.M., Hopewell, S., Thabane, L., Lancaster, G.A., and PAFS consensus group (2016). CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2, 64. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T.C., Glasziou, P.P., Boutron, I., Milne, R., Perera, R., Moher, D., Altman, D.G., Barbour, V., Macdonald, H., Johnston, M., et al. (2014). Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 348, g1687. [CrossRef]

- Sim, J., and Lewis, M. (2012). The size of a pilot study for a clinical trial should be calculated in relation to considerations of precision and efficiency. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 65, 301–308. [CrossRef]

- Julious, S.A. (2005). Sample size of 12 per group rule of thumb for a pilot study. Pharm. Stat. 4, 287–291. [CrossRef]

- Eysenbach, G. (2013). CONSORT-EHEALTH: implementation of a checklist for authors and editors to improve reporting of web-based and mobile randomized controlled trials. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 192, 657–661.

- Eysenbach, G., and CONSORT-EHEALTH Group (2011). CONSORT-EHEALTH: improving and standardizing evaluation reports of Web-based and mobile health interventions. J. Med. Internet Res. 13, e126.

- Sheill, G., Guinan, E., Brady, L., Hevey, D., and Hussey, J. (2019). Exercise interventions for patients with advanced cancer: A systematic review of recruitment, attrition, and exercise adherence rates. Palliat. Support. Care 17, 686–696. [CrossRef]

- Oei, T.P., and Shuttlewood, G.J. (1999). Development of a satisfaction with therapy and therapist Scale. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 33, 748–753.

- Sidani, S., Epstein, D.R., and Fox, M. (2017). Psychometric evaluation of a multi-dimensional measure of satisfaction with behavioral interventions. Res. Nurs. Health 40, 459–469. [CrossRef]

- Eze, A., Anyebe, M.O., Nnamani, R.G., Nwaogaidu, J.C., Mmegwa, P.U., Akubo, E.A., Bako, V.N., Ishaya, S.N., Eze, M.I., Ekwueme, F.O., et al. (2023). Online cognitive-behavioral intervention for stress among English as a second language teachers: implications for school health policy. Front. Psychiatry 14, 1140300. [CrossRef]

- de Boer, A.G.E.M., Verbeek, J.H.A.M., Spelten, E.R., Uitterhoeve, A.L.J., Ansink, A.C., de Reijke, T.M., Kammeijer, M., Sprangers, M.A.G., and van Dijk, F.J.H. (2008). Work ability and return-to-work in cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer 98, 1342–1347. [CrossRef]

- Stapelfeldt, C.M., Momsen, A.-M.H., Jensen, A.B., Andersen, N.T., and Nielsen, C.V. (2021). Municipal return to work management in cancer survivors: a controlled intervention study. Acta Oncol. 60, 370–378. [CrossRef]

- Tamminga, S.J., Verbeek, J.H.A.M., Bos, M.M.E.M., Fons, G., Kitzen, J.J.E.M., Plaisier, P.W., Frings-Dresen, M.H.W., and de Boer, A.G.E.M. (2019). Two-Year Follow-Up of a Multi-centre Randomized Controlled Trial to Study Effectiveness of a Hospital-Based Work Support Intervention for Cancer Patients. J. Occup. Rehabil. 29, 701–710. [CrossRef]

- Ilmarinen, J. (2006). The Work Ability Index (WAI). Occup Med (Lond) 57, 160–160. [CrossRef]

- Zaman, A.C.G.N.M., Tytgat, K.M.A.J., Klinkenbijl, J.H.G., Boer, F.C. den, Brink, M.A., Brinkhuis, J.C., Bruinvels, D.J., Dol, L.C.M., van Duijvendijk, P., Hemmer, P.H.J., et al. (2021). Effectiveness of a Tailored Work-Related Support Intervention for Patients Diagnosed with Gastrointestinal Cancer: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Occup. Rehabil. 31, 323–338. [CrossRef]

- Tamminga, S.J., Verbeek, J.H.A.M., Bos, M.M.E.M., Fons, G., Kitzen, J.J.E.M., Plaisier, P.W., Frings-Dresen, M.H.W., and de Boer, A.G.E.M. (2013). Effectiveness of a hospital-based work support intervention for female cancer patients - a multi-centre randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE 8, e63271. [CrossRef]

- Nekhlyudov, L., Campbell, G.B., Schmitz, K.H., Brooks, G.A., Kumar, A.J., Ganz, P.A., and Von Ah, D. (2022). Cancer-related impairments and functional limitations among long-term cancer survivors: Gaps and opportunities for clinical practice. Cancer 128, 222–229. [CrossRef]

- Munir, F., Yarker, J., and McDermott, H. (2009). Employment and the common cancers: correlates of work ability during or following cancer treatment. Occup Med (Lond) 59, 381–389. [CrossRef]

- de Boer, A.G.E.M., de Wind, A., Coenen, P., van Ommen, F., Greidanus, M.A., Zegers, A.D., Duijts, S.F.A., and Tamminga, S.J. (2023). Cancer survivors and adverse work outcomes: associated factors and supportive interventions. Br. Med. Bull. 145, 60–71. [CrossRef]

- Leensen, M.C.J., Groeneveld, I.F., van der Heide, I., Rejda, T., van Veldhoven, P.L.J., Berkel, S. van, Snoek, A., Harten, W. van, Frings-Dresen, M.H.W., and de Boer, A.G.E.M. (2017). Return to work of cancer patients after a multidisciplinary intervention including occupational counselling and physical exercise in cancer patients: a prospective study in the Netherlands. BMJ Open 7, e014746. [CrossRef]

- Maheu, C., and Parkinson, M. (2021). Supporting cancer survivors with return to work e-course for primary care providers. www.fpon.ca, 2, 13. Available at: http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/family-oncology-network-site/Documents/2021SpringFPONjournal_Apr29web.pdf [Accessed July 21, 2022].

- Greidanus, M.A., de Boer, A.G.E.M., de Rijk, A.E., Frings-Dresen, M.H.W., and Tamminga, S.J. (2020). The MiLES intervention targeting employers to promote successful return to work of employees with cancer: design of a pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials 21, 363. [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, D.M., Frost, D., Jefford, M., O’Connor, M., and Halkett, G. (2020). Building a novel occupational rehabilitation program to support cancer survivors to return to health, wellness, and work in Australia. J. Cancer Surviv. 14, 31–35. [CrossRef]

- Leensen, M.C.J., Groeneveld, I.F., Rejda, T., Groenenboom, P., van Berkel, S., Brandon, T., de Boer, A.G.E.M., and Frings-Dresen, M.H.W. (2018). Feasibility of a multidisciplinary intervention to help cancer patients return to work. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 27, e12690. [CrossRef]

- Kovacevic, N., Žagar, T., Homar, V., Pelhan, B., Sremec, M., Rozman, T., and Besic, N. (2024). Benefits of early integrated and vocational rehabilitation in breast cancer on work ability, sick leave duration, and disability rates. Healthcare (Basel) 12. [CrossRef]

- Rath, H.M., Steimann, M., Ullrich, A., Rotsch, M., Zurborn, K.-H., Koch, U., Kriston, L., and Bergelt, C. (2015). Psychometric properties of the Occupational Stress and Coping Inventory (AVEM) in a cancer population. Acta Oncol. 54, 232–242. [CrossRef]

- Greidanus, M.A., de Boer, A.G.E.M., de Rijk, A.E., Brouwers, S., de Reijke, T.M., Kersten, M.J., Klinkenbijl, J.H.G., Lalisang, R.I., Lindeboom, R., Zondervan, P.J., et al. (2020). The Successful Return-To-Work Questionnaire for Cancer Survivors (I-RTW_CS): Development, Validity and Reproducibility. Patient 13, 567–582. [CrossRef]

| Variable | iCanWork (n = 12) | Control (n = 11) | Total (N = 23) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Mean (SD): 43.08 ± 9.22 |

Mean (SD): 48.27 ± 8.34 |

Mean (SD): 45.57 ± 9.01 |

| Months to RTW | Mean (SD): 9.75 ± 5.34 |

Mean (SD): 12.55 ± 6.56 |

Mean (SD): 11.09 ± 5.99 |

| Gender | |||

| Women | 12 (100.0%) | 10 (90.9%) | 22 (95.7%) |

| Men | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married/Common law | 10 (62.5%) | 6 (37.5%) | 16 (69.6%) |

| Never Married | 2 (50.0%) | 2 (50.0%) | 4 (17.4%) |

| Separated | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (100.0%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| Other | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (100.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Education | |||

| Less than High School | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (100.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| High School Graduate | 1 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Some College | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | 3 (13.0%) |

| University/College Graduate | 6 (46.2%) | 7 (53.8%) | 13 (56.5%) |

| Postgraduate | 4 (80.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 5 (21.7%) |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Breast Cancer | 11 (91.7%) | 8 (72.7%) | 19 (82.6%) |

| Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | 1 (8.3%) | 2 (18.2%) | 3 (13.0%) |

| Oral Cancer | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Treatment | |||

| Chemotherapy (Yes) | 9 (75.0%) | 9 (81.8%) | 18 (78.3%) |

| Radiation (Yes) | 5 (41.7%) | 5 (45.5%) | 10 (43.5%) |

| Occupation (NOC) | |||

| 3114 – Professional health services | 2 (16.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| 1228 – Employment insurance | 1 (8.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| 0124 – Advertising, marketing | 1 (8.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Occupations in education, law | 4 (33.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (17.4%) |

| 1253 – Records management | 2 (16.7%) | 4 (36.4%) | 6 (26.1%) |

| 0311 – Business managers | 2 (16.7%) | 3 (27.3%) | 5 (21.7%) |

| 1223 – Human resources | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| 1222 – Executive assistants | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| 6552 – Customer service | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| 4021 – College and instructors | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| ID | Before RTW | After RTW | Reasons |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 1 VR | 2 VR | Met the benchmark for before and after RTW. |

| P2 | 2 VR, 1 OT | 1 VR | Met the benchmark for before and after RTW. |

| P3 | 2 VR, 1 OT | 0 | Met before RTW; after RTW unmet due to scheduling issues. |

| P4 | 1 VR, 1 OT | 1 VR | Met the benchmark for before and after RTW. |

| P5 | 1 VR, 1 OT | 1 VR | Met the benchmark for before and after RTW. |

| P6 | 2 VR, 1 OT | 0 | Met before RTW; after RTW unmet due to scheduling issues. |

| P7 | 2 VR, 0 OT | 0 | Met before RTW; OT not delivered despite attempts. RTW not attempted. |

| P8 | 2 VR, 1 OT | 0 | Met before RTW; RTW not attempted during study time frame. |

| P9 | 1 VR, 1 OT | 1 VR | Met the benchmark for before and after RTW. |

| P10 | 2 VR, 1 OT | 0 | Met before RTW; RTW not attempted during study time frame. |

| P11 | 1 VR | 0 | Met before RTW; study ended before additional VR could occur. |

| P12 | 1 VR | 0 | Met before RTW; study ended before additional VR could occur. |

| Domain | Item | Intervention Count Agree (%) (n = 12) | Control Count Agree (%) (n = 5) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction with Intervention | I am satisfied with the quality of the intervention I received (Item 1) | 9 (75.0%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| The interventionist listened to what I was trying to say (Item 2) | 12 (100.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | |

| My needs were met by the program (Item 3) | 8 (66.7%) | 2 (40.0%) | |

| The interventionist provided an adequate explanation (Item 4) | 12 (100.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | |

| I would recommend the program to a friend (Item 5) | 9 (75.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | |

| The interventionist was not negative or critical towards me (Item 6) | 9 (75.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | |

| I would return to the program if I needed help (Item 7) | 9 (75.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | |

| Satisfaction with Therapist | The interventionist was friendly and warm towards me (Item 8) | 12 (100.0%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| I am now able to deal more effectively with my problems (Item 9) | 5 (41.7%) | 2 (40.0%) | |

| I felt free to express myself (Item 10) | 12 (100.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | |

| I was able to focus on what was of real concern to me (Item 11) | 10 (83.3%) | 2 (40.0%) | |

| The interventionist seemed to understand what I was thinking and feeling (Item 12) | 9 (75.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | |

| Perceived Changes in Condition | How much did this intervention help with the specific problems that led you to the program? (Item 13) | 10 (83.3%) | 4 (80.0%) |

| RTW Status | iCanWork (n = 12) | Control (n = 11) | Total (n = 23) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Returned Full-Time | 6 (50.0%) | 4 (36.4%) | 10 (43.5%) |

| Returned Part-Time | 4 (33.3%) | 6 (54.5%) | 10 (43.5%) |

| Did Not Return to Work | 2 (16.7%) | 1 (9.1%) | 3 (13.0%) |

| Median Time to RTW (months) | 8.0 | 11.00 | 11.0 |

| Mean Time to RTW (months) | 10.4 | 13.5 | 12.1 |

| Outcomes And Instruments | Group | Baseline (T1) Mean (SD) (n) |

3 Months Follow-up (T2) Mean (SD) (n) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Work Ability (7-49) |

Intervention | 27.63 (1.37) (n=12) | 30.17 (2.02) (n=12) | 0.111 |

| Control | 30.12 (1.7) (n=11) | 28.21 (2.65) (n=7) |

| Time | WAI Category | iCanWork (n, %) |

Control (n, %) | Total (n) | Mann-Whitney U | Exact p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | Poor (7–27 points) | 4 (44.4%) | 5 (55.6%) | 9 | ||

| Moderate (28–36 points) | 7 (58.3%) | 5 (41.7%) | 12 | |||

| Good (37–43 points) | 1 (50.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 2 | 69.50 | 0.33 | |

| T2 | Poor (7–27 points) | 5 (71.4%) | 2 (28.6%) | 7 | ||

| Moderate (28–36 points) | 5 (55.6%) | 4 (44.4%) | 9 | |||

| Good (37–43 points) | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | 3 | 36.50 | 0.650 |

| Group | N Total | Increased Scores | Decreased Scores | Unchanged Scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iCanWork | 12 | 6 | 5 | 1 |

| Control | 7 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Domain | Group | Baseline Mean (SD) (T1) | Three months post- baseline (T2) Mean (SD) |

p-value (Within Group) | p-value (Between Groups) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Function | iCanWork | 50.93 ± 7.845 | 50.89 ± 7.103 | 0.799 | |

| Control | 42.95 ± 6.783 | 44.31 ± 5.818 | 0.116 | 0.995 | |

| Anxiety | iCanWork | 58.75 ± 7.30 | 57.25 ± 6.70 | 0.423 | |

| Control | 59.21 ± 8.78 | 60.71 ± 9.78 | 0.753 | 0.574 | |

| Depression | iCanWork | 51.70 ± 8.05 | 53.44 ± 6.95 | 0.423 | |

| Control | 54.75 ± 9.58 | 59.11 ± 9.91 | 0.753 | 0.280 | |

| Fatigue | iCanWork | 52.23 ± 10.55 | 49.82 ± 5.57 | .350 | |

| Control | 58.57 ± 8.42 | 58.44 ± 8.10 | .753 | 0.040 | |

| Sleep disturbance | iCanWork | 51.05 ± 10.90 | 47.92 ± 10.61 | 0.173 | |

| Control | 58.66 ± 9.64 | 55.67 ± 8.38 | 0.225 | 0.131 | |

| Social roles and activities | iCanWork | 51.61 ± 1.39 | 51.61 ± 1.39 | .262 | |

| Control | 44.54 ± 6.67 | 43.63 ± 6.14 | .917 | 0.017 | |

| Pain interference | iCanWork | 48.78 ± 8.098 | 49.39 ± 8.249 | 0.735 | |

| Control | 58.14 ± 10.237 | 61.47 ± 6.265 | 0.893 | 0.006 | |

| Pain intensity | iCanWork | 2.70 (3.03) | 1.83 (2.41) | 0.262 | |

| Control | 3.80 (2.52) | 5.43 (2.15) | 0.202 | 0.036 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).