Submitted:

12 February 2025

Posted:

13 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

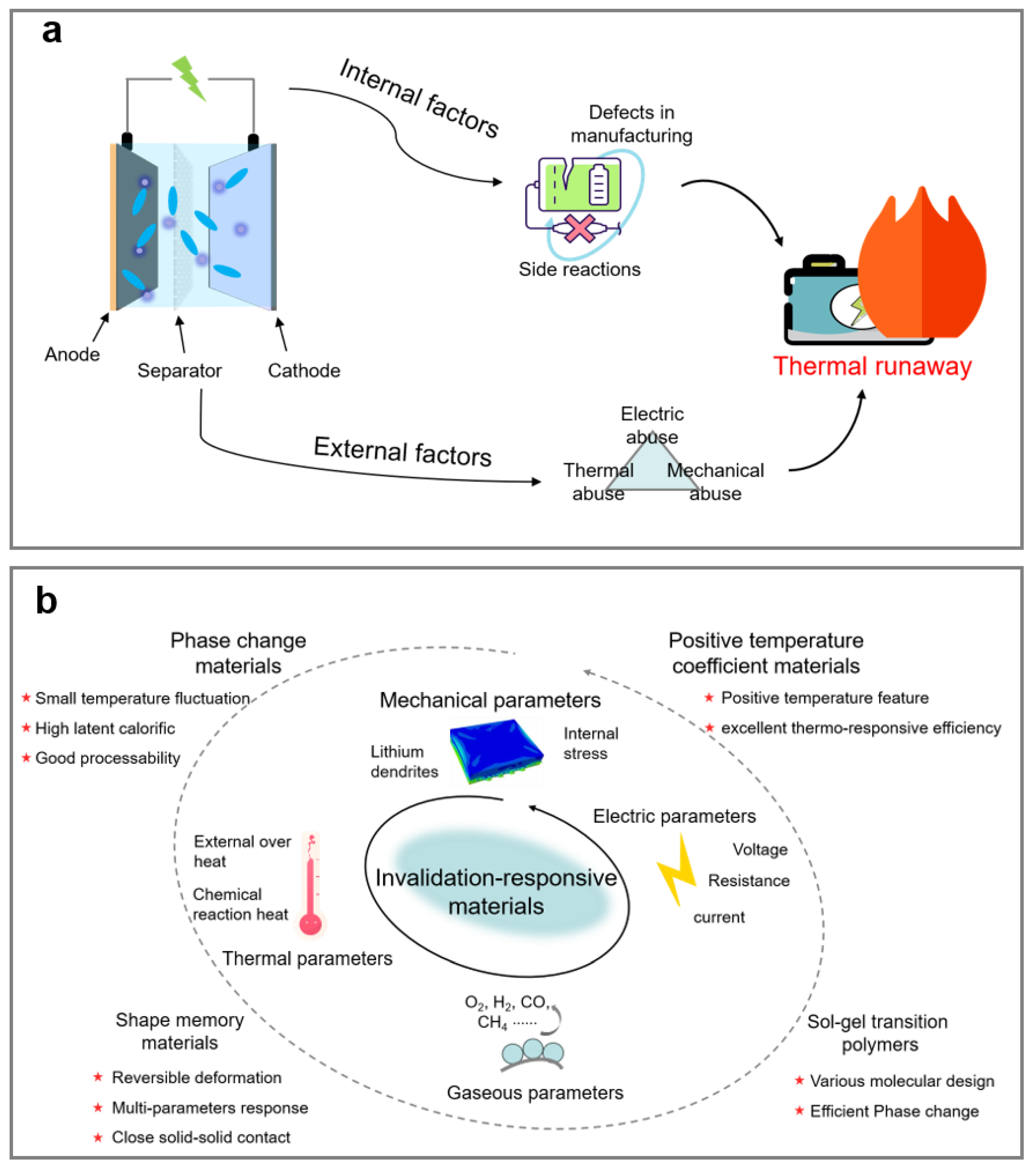

1. Introduction

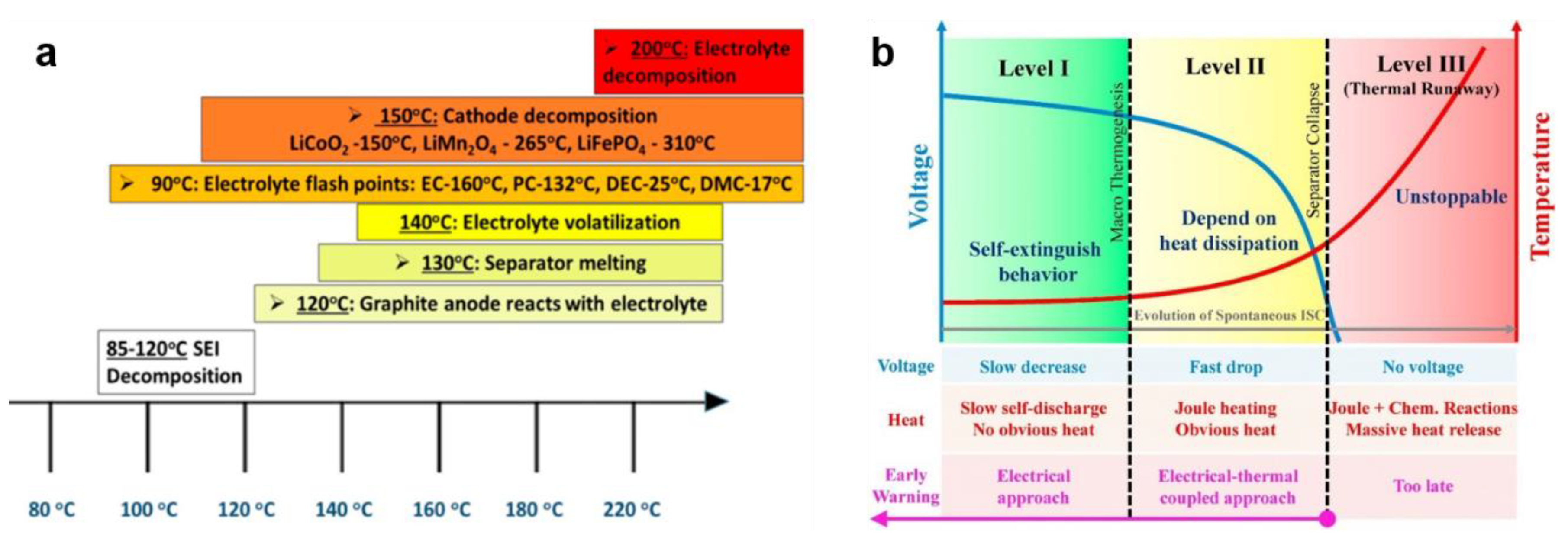

2. Thermal Runaway Characteristics

2.1. Thermal Runaway of LIBs

2.2. Triggering Mechanism of Thermal Runaway in LIBs

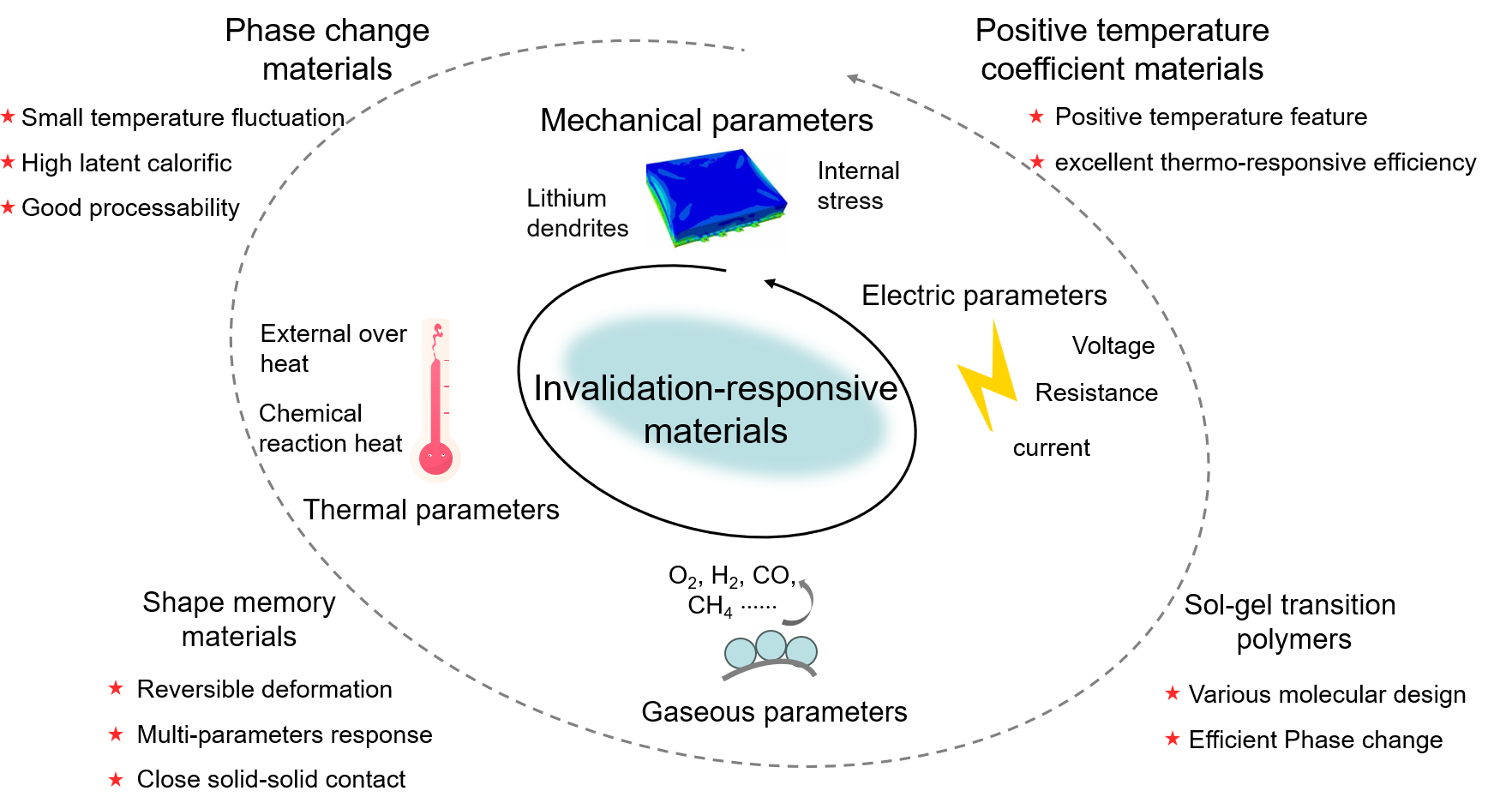

3. The Categories of Smart Safety Materials

3.1. Phase Change Materials

3.2. Positive Temperature Coefficient Materials

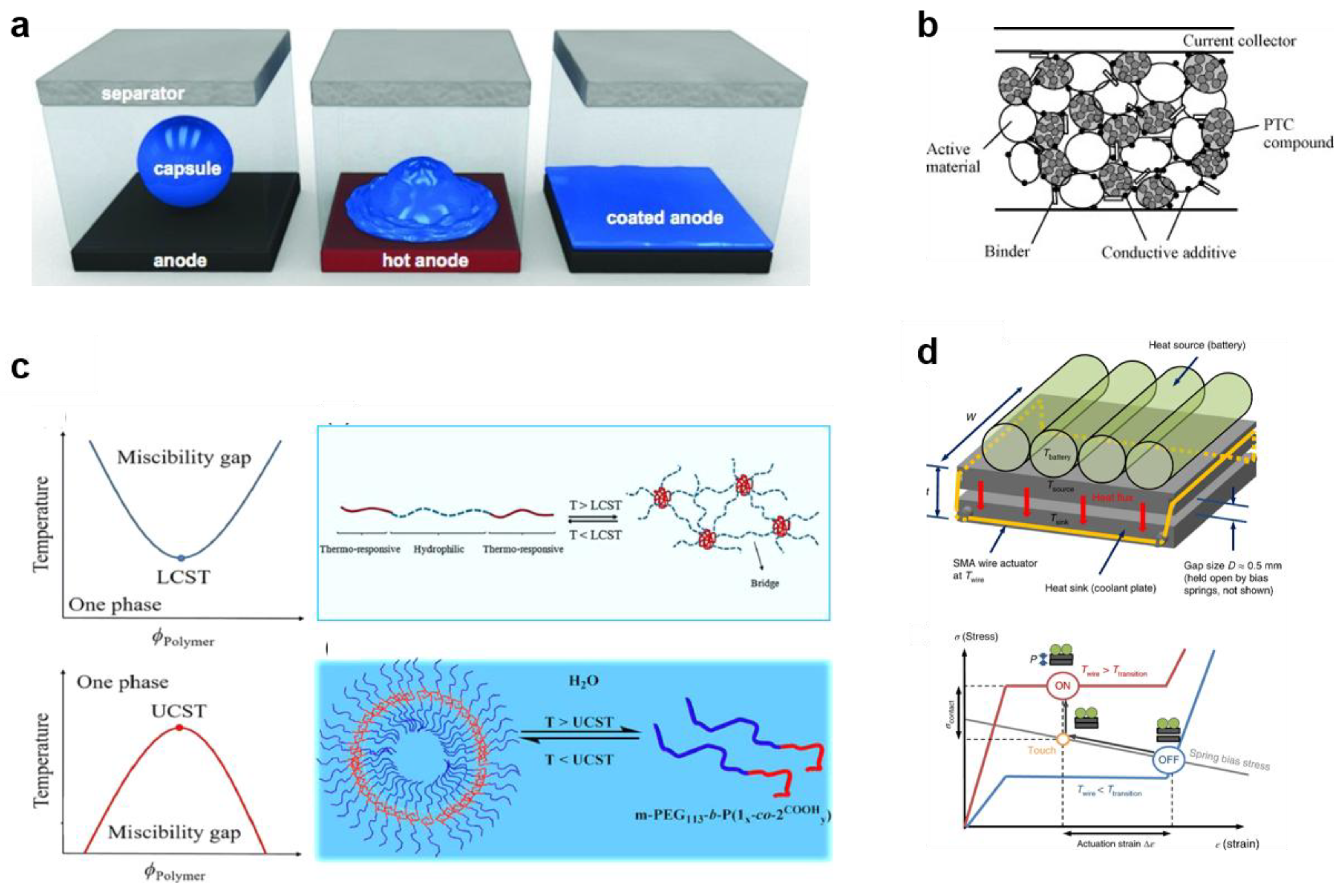

3.3. Sol-Gel Transition Polymers

3.4. Shape Memory Materials

4. Design and Application of LIBs’ Key Components

4.1. Thermo-Responsive Safety Materials

4.1.1. Thermo-Responsive Electrode

4.1.2. Thermo-Responsive Electrolyte

4.1.3. Thermo-Responsive Current Collector

4.1.4. Thermo-Responsive Separator

4.2. Electric-Responsive Safety Materials

4.2.1. Electric-Responsive Additives

4.2.2. Electric-Responsive Separator

4.3. Mechanical-Responsive Safety Materials

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

5.1. Advanced Characterization Techniques for Detection of Invalidation Status

5.2. Cross-Scale Response of Smart Materials for LIBs

5.3. Utilization of High Safety Redundancy Component

Acknowledgments

Declaration of competing interest

References

- Lin, D.; Liu, Y.Y.; Cui, Y. Reviving the lithium metal anode for high-energy batteries. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2017, 12, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Stalin, S.; Zhao, C.Z.; Archer, L.A. Designing solid-state electrolytes for safe, energy-dense batteries. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.S.; Nolan, A.M.; Lu, J. Z; Wang, J.Y.; Yu, X.Q.; Mo, Y.F.; Chen, L.Q.; Huang, X.J.; Li, H. The thermal stability of lithium solid electrolytes with metallic lithium. Joule. 2020, 4, 812–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.Q.; Murugesan, V.; Han, K.S.; Jiang, X.Y.; Cao, Y.L.; Xiao, L.F.; Ai, X.P.; Yang, H.X.; Zhang, J.-G.; Sushko, M.L.; Liu, J. Non-flammable electrolytes with high salt-to-solvent ratios for Li-ion and Li-metal batteries. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 674–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.X.; Lu, L.G.; Wang, L.; Ohma, A.; Ren, D.S.; Feng, X.N.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.L.; Ootani, I.; Han, X.B.; Ren, W.N.; He, X.M. Thermal runaway of Lithium-ion batteries employing LiN(SO2F)2-based concentrated electrolytes. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5100. [Google Scholar]

- Abada, S.; Marlair, G.; Lecocq, A.; Petit, M.; Sauvant-Moynot, V.; Huet, F. Safety focused modeling of lithium-ion batteries: A review. J. Power Sources 2016, 306, 178–192. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Kang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Liang, Z.; He, X.; Li, X.; Tavajohi, N.; Li, B. A review of lithium-ion battery safety concerns: The issues, strategies, and testing standards. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 59, 83–99. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.S.; Ping, P.; Zhao, X.J.; Chu, G.Q.; Sun, J.H.; Chen, C.H. Thermal runaway caused fire and explosion of lithium ion battery. J. Power Sources 2012, 208, 210–224. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, L.; Li, S.L.; Ai, X.P.; Yang, H.X.; Cao, Y.L. Temperature-sensitive cathode materials for safer lithium-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 2845–2848. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Mao, B.; Stoliarov, S.I.; Sun, J. A review of lithium ion battery failure mechanisms and fire prevention strategies. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2019, 73, 95–131. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Shang, R.; Cheng, C.; Cheng, Y.; Xing, J.; Wei, Z.; Zhao, Y. Recent advances in lithium-ion battery separators with reversible/irreversible thermal shutdown capability. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 43, 143–157. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Liu, Y.Y.; Lin, D.C.; Pei, A.; Cui, Y. Materials for lithium-ion battery safety. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, 9820. [Google Scholar]

- He, W.; Guo, W.B.; Wu, H.L.; Lin, L.; Liu, Q.; Han, X.; Xie, Q.S.; Liu, P.F.; Zheng, H.F.; Wang, L.S. Challenges and recent advances in high capacity Li-rich cathode materials for high energy density lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2005937. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X. , Fang, M., He, X., Ouyang, M., Lu, L., Wang, H., and Zhang, M. Thermal runaway features of large format prismatic lithium ion battery using extended volume accelerating rate calorimetry. J. Power Sources 2014, 255, 294–301. [Google Scholar]

- Loveridge, M.J.; Remy, G.; Kourra, N.; Genieser, R.; Barai, A.; Lain, M.J.; Guo, Y.; Amor-Segan, M.; Williams, M.A.; Amietszajew, T.; Ellis, M.; Bhagat, R.; Greenwood, D. Looking deeper into the galaxy (note 7). Batteries 2018, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.L.; Yi, Y.K.; Fang, B.R.; Yang, P.; Wang, T.; Liu, P.; Qu, L.; Li, M.T.; Zhang, S.Q. Design strategies of safe electrolytes for preventing thermal runaway in lithium ion batteries. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 9821–9848. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.N.; Ren, D.S.; He, X.M.; Ouyang, M.G. Mitigating Thermal Runaway of Lithium-Ion Batteries. Joule 2020, 4, 743–770. [Google Scholar]

- He, W.; Guo, W.B.; Wu, H.L.; Lin, L.; Liu, Q.; Han, X.; Xie, Q.S.; Liu, P.F.; Zheng, H.F.; Wang, L.S.; Yu, X.Q.; Peng, D.L. Challenges and Recent Advances in High Capacity Li-Rich Cathode Materials for High Energy Density Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2005937. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.F.; Zhang, J.; Xue, W.R.; Li, J.Z.; Chen, R.S.; Pan, H.Y.; Yu, X.Q.; Liu, Y.J.; Li, H.; Chen, L.Q. Anomalous thermal decomposition behavior of polycrystalline LiNi0.8Mn0.1Co0.1O2 in PEO-based solid polymer electrolyte. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2200096. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.S. Fan, Z.W.; Zhang, M.Q.; Wang, P.B.; Wang, H.B.; Jin, C.Y.; Peng, Y.; Jiang, F.C.; Feng, X.N.; Ouyang, M.G. A Comparative Study of the Venting Gas of Lithium-ion Batteries during Thermal Runaway Triggered by Various Methods. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2023, 4, 101705. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Feng, X.N.; Ma, Z.; Gao, L.H.; Wang, Y.W.; Zhao, C.Z.; Ren, D.S.; Yang, M. Xu, C.S.; Wang, L.; He, X.M.; Lu, L.G.; Ouyang, M.G. Electrolyte Design for Stable Electrode-electrolyte Interphase to Enable High-safety and High-voltage Batteries. eTransportation 2023, 15, 100216. [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza, L.F.; Frazzica, A.; Chafer, M.; Verez, D.; Palomba, V. Research trends and perspectives of thermal management of electric batteries: Bibliometric analysis. J. Energy Storage 2020, 32, 101976. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, A.A. Battery thermal models for hybrid vehicle simulations. J. Power Sources 2002, 110, 377–382. [Google Scholar]

- Kise, M.; Yoshioka, S.; Kuriki, H. Relation between composition of the positive electrode and cell performance and safety of lithium-ion PTC batteries. J. Power Sources 2007, 174, 861–866. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, J.M. Designs of conductive polymer composites with exceptional reproducibility of positive temperature coefficient effect: A review. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138, 49677. [Google Scholar]

- Bordat, A.; Boissenot, T.; Nicolas, J.; Tsapis, N. Thermoresponsive polymer nanocarriers for biomedical applications. Adv. Drug. Del. Rev. 2019, 138, 167–192. [Google Scholar]

- Pasparakis, G.; Tsitsilianis, C. LCST polymers: Thermoresponsive nanostructured assemblies towards bioapplications. Polymer 2020, 211, 123146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, M.L.; Li, J.; Park, S.; Moura, S.; Dames, C. Efficient thermal management of Li-ion batteries with a passive interfacial thermal regulator based on a shape memory alloy. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 899–906. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.F.; Ruan, Z.H.; Liu, Z.X.; Wang, Y.K.; Tang, Z.J.; Li, H.F.; Zhu, M.S.; Huang, T.F.; Liu, J.; Shi, Z.C.; Zhi, C.Y. A flexible rechargeable zinc-ion wire-shaped battery with shape memory function. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 8549–8557. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, J.W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Yuan, L.X.; Liu, X.T.; Cheng, Z.X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.X.; Li, Z.; Shen, Y. A flame-retardant polymer electrolyte for high performance lithium metal batteries with an expanded operation temperature. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 3510–3521. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.Y.; Li, W.D.; You, Y.; Manthiram, A. Extending the service life of high-Ni layered oxides by tuning the electrode-electrolyte interphase. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1801957. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Feng, X.N.; Ren, D.S.; Li, Y.; Rui, X.Y.; Wang, Y.; Han, X.B.; Xu, G.L. Development of cathode-electrolyte-interphase for safer lithium batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 37, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.N.; Zhang, C.R.; Li, H.; Cao, Y.L.; Yang, H.X.; Ai, X.P. Reversible temperature-responsive cathode for thermal protection of lithium-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 5236–5244. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Wang, F.; Zhang, C.R.; Ji, W.; Qian, J.F.; Cao, Y.L.; Yang, H.X.; Ai, X.P. A temperature-sensitive poly (3-octylpyrrole)/carbon composite as a conductive matrix of cathodes for building safer Li-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2019, 17, 275–283. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.N.; Zhang, C.R.; Li, H.; Cao, Y.L.; Yang, H.X.; Ai, X.P. Reversible temperature-responsive cathode for thermal protection of lithium-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 5236–5244. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, H.Z.; Han, X.F.; Radjenovic, P.M.; Tian, J.H.; Li, J.F. Facile and effective positive temperature coefficient (PTC) layer for safer lithium-ion batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 1761–1766. [Google Scholar]

- Baginska, M.; Blaiszik, B.J.; Rajh, T.; Sottos, N.R. White, S.R. Enhanced autonomic shutdown of Li-ion batteries by polydopamine coated polyethylene microspheres. J. Power Sources 2014, 269, 735–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Hsu, P.C.; Lopez, J.; Li, Y.Z.; To, J.W.; Liu, N.; Wang, C.; Andrews, S.C.; Liu, J. Cui, Y. Fast and reversible thermoresponsive polymer switching materials for safer batteries. Nat. Energy. 2024, 1, 2058–7546. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, G.R.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Q.S.; Bai, Q.Y.; Quan, Y.Z.; Gao, Y.; Wu, G. Wang, Y.Z. Non-flammable solvent-free liquid polymer electrolyte for lithium metal batteries. Nat Commun. 2023, 14, 4617. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, J.C.; Pepin, M.; Huber, D.L.; Bunker, B.C.; Roberts, M.E. Reversible control of electrochemical properties using thermally-responsive polymer electrolytes. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 886–889. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Xue, P.; Liu, J.L.; Xu, X.H. Thermal-switching and repeatable self-protective hydrogel polyelectrolytes for energy storage applications of flexible electronics. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2021, 4, 6116–6124. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, Y.H.; Zhou, B.H.; Jiang, K.; Li, S.Q.; Zuo, C.; Gan, H.H.; He, D.; Zhou, X.P.; Xue, Z.G. Self-healing and shape-memory solid polymer electrolytes with high mechanical strength facilitated by a poly (vinyl alcohol) matrix. Polym. Chem. 2019, 10, 6561–6569. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.; Dong, S.M.; Lv, Z.L.; Xu, G.J.; Huang, L.; Wang, Q.L.; Cui, Z.L.; Cui, G.L. A temperature-responsive electrolyte endowing superior safety characteristic of lithium metal batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 1903441. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, J.C.; Liu, H.; Liao, S. L; Liu, K.; Wang, Y.P. Early braking of overwarmed lithium-ion batteries by shape-memorized current collectors. Nano Lett. 2022, 22, 9122–9130. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Y.S.; Chou, L.Y.; Liu, Y.Y.; Wang, H.S.; Lee, H.K.; Huang, W.X.; Wan, J.Y.; Liu, K.; Zhou, G. M; Yang, Y.F. Ultralight and fire-extinguishing current collectors for high-energy and high-safety lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 786–793. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.H.; Zhong, L.; Zhang, L.Q.; Kushima, A.; Mao, S.X.; Li, J.; Ye, Z.Z.; Sullivan, J.P.; Huang, J.Y. Lithium fiber growth on the anode in a nanowire lithium ion battery during charging. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 98. [Google Scholar]

- Steiger, J.; Kramer, D.; Mönig, R. Microscopic observations of the formation, growth and shrinkage of lithium moss during electrodeposition and dissolution. Electrochimica Acta. 2014, 136, 529–536. [Google Scholar]

- Steiger, J.; Kramer, D.; Mönig, R. Mechanisms of dendritic growth investigated by in situ light microscopy during electrodeposition and dissolution of lithium. J. Power Sources 2014, 261, 112–119. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H.; Wang, P.; Yan, S.S.; Xia, Y.C.; Wang, B.G.; Wang, X.L.; Liu, K. A thermoresponsive composite separator loaded with paraffin@ SiO2 microparticles for safe and stable lithium batteries. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 62, 423–430. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, W.X.; Jiang, B.L.; Ai, F.X.; Yang, H.X.; Ai, X.P. Temperature-responsive microspheres-coated separator for thermal shutdown protection of lithium ion batteries. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 172–176. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Li, C.H.; Wang, X.; Peng, C.; Cai, Y.P.; Huang, W.C. A hybrid system dynamics and optimization approach for supporting sustainable water resources planning in Zhengzhou City, China. J. Hydrol. 2018, 556, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.M.; Han, K.; Martin, E.J.; Wu, Y.Y.; Kung, M.C.; Hayner, C.M.; Shull, K.R.; Kung, H.H. Upper-critical solution temperature (UCST) polymer functionalized graphene oxide as thermally responsive ion permeable membrane for energy storage devices. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 18204–18207. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.J.; Yuan, Z.Z.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Zhang, H.Z.; Zhang, H.M.; Li, X.F. Porous membranes in secondary battery technologies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 2199–2236. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.A.; Williams, B.P.; Joo, Y.L. Effect of polymer and ceramic morphology on the material and electrochemical properties of electrospun PAN/polymer derived ceramic composite nanofiber membranes for lithium ion battery separators. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 526, 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, L.Y.; An, P.; Xu, Z.W.; Huang, J.F. Performance evaluation of electrospun polyimide non-woven separators for high power lithium-ion batteries. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2016, 767, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.Y.; Xiao, L.F.; Ai, X.P.; Yang, H.X.; Cao, Y.L. A novel bifunctional thermo-sensitive poly (lactic acid)@ poly (butylene succinate) core–shell fibrous separator prepared by a coaxial electrospinning route for safe lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 23238–23242. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.H.; Ding, Y.H.; Zhang, P.; Li, F.; Yang, Z.M. Temperature-dependent on/off PVP@ TiO2 separator for safe Li-storage. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 565, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes-Pereira, J.; Costa, C.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. Polymer composites and blends for battery separators: state of the art, challenges and future trends. J. Power Sources 2015, 281, 378–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, T.; Park, M.S.; Woo, S.G.; Kwon, H.K.; Yoo, J.K.; Jung, Y.S.; Kim, K.J.; Yu, J.S.; Kim, Y.J. Self-extinguishing lithium ion batteries based on internally embedded fire-extinguishing microcapsules with temperature-responsiveness. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 5059–5067. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Liu, W.; Qiu, Y.C.; Kong, B.; Sun, Y.M.; Chen, Z.; Zhuo, D.; Lin, D.C.; Cui, Y. Electrospun core-shell microfiber separator with thermal-triggered flame-retardant properties for lithium-ion batteries. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1601978. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y.K.; Xu, J. Data-driven short circuit resistance estimation in battery safety issues. J. Energy Chem. 2023, 79, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, R.; Liu, J.; Gu, J.J. Simulation and experimental study on lithium ion battery short circuit. Appl. Energy 2016, 173, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.L.; Wang, Z.R.; Bai, J.L. Influences of multi factors on thermal runaway induced by overcharging of lithium-ion battery. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 70, 531–541. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.S.; Hu, C.C.; Li, Y.Y. The importance of heat evolution during the overcharge process and the protection mechanism of electrolyte additives for prismatic lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2008, 181, 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, L.F.; Ai, X.P.; Cao, Y.L.; Yang, H.X. Electrochemical behavior of biphenyl as polymerizable additive for overcharge protection of lithium ion batteries. Electrochimica Acta. 2004, 49, 4189–4196. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.Q.; Xing, L.D.; Li, W.S.; Zuo, X.X.; Shu, D.; Li, G.L. Application of cyclohexyl benzene as electrolyte additive for overcharge protection of lithium ion battery. J. Power Sources 2008, 184, 427–431. [Google Scholar]

- Korepp, C.; Kern, W.; Lanzer, E.; Raimann, P.; Besenhard, J.; Yang, M.; Möller, K.C.; Shieh, D.T.; Winter, M. 4-Bromobenzyl isocyanate versus benzyl isocyanate—New film-forming electrolyte additives and overcharge protection additives for lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2007, 174, 637–642. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.L.; Ai, X.P.; Feng, J.K.; Cao, Y.L.; Yang, H.X. Diphenylamine: A safety electrolyte additive for reversible overcharge protection of 3.6 V-class lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2008, 184, 553–556. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Xia, Q.; Zhang, P.; Li, G.C.; Wu, Y.P.; Luo, H.J.; Zhao, S.Y.; Van Ree, T. N-Phenylmaleimide as a new polymerizable additive for overcharge protection of lithium-ion batteries. Electrochem. Commun. 2008, 10, 727–730. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Xu, M.Q.; Li, B.; Xing, L.D.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.S. Dimethoxydiphenylsilane (DDS) as overcharge protection additive for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2013, 244, 499–504. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.K.; Lu, L. A novel bifunctional additive for safer lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2013, 243, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.; Zheng, X.Z.; Wang, W.G.; Pan, Y.; Fang, G.H.; Wu, M.X. (2-Chloro-4-methoxy)-phenoxy pentafluorocyclotriphosphazene as a safety additive for lithium-ion batteries. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2017, 196, 310–314. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, S.R.; Surampudi, S.; Attia, A.I.; Bankston, C.P. Analysis of redox additive-based overcharge protection for rechargeable lithium batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1991, 138, 2224. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.S.; Jiang, L.H.; Yu, Y.; Sun, J.H. Progress of enhancing the safety of lithium ion battery from the electrolyte aspect. Nano Energy 2019, 55, 93–114. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.C.; Tsai, M.J.; Lee, M.H.; Kuo, C.Y.; Shen, M.C.; Tsai, Y.M.; Chen, H.C.; Hung, J.Y.; Huang, M.S.; Chong, I.W. Lower starting dose of afatinib for the treatment of metastatic lung adenocarcinoma harboring exon 21 and exon 19 mutations. BMC cancer. 2021, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, C.S.; Ai, X.P.; Yang, H.X. Polypyridine complexes of iron used as redox shuttles for overcharge protection of secondary lithium batteries. J. Power Sources 1995, 54, 255–258. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.H.; Qin, Y.; Amine, K. Redox shuttles for safer lithium-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta. 2009, 54, 5605–5613. [Google Scholar]

- Ergun, S.; Elliott, C.F.; Kaur, A.P.; Parkin, S.R.; Odom, S.A. Overcharge performance of 3, 7-disubstituted N-ethylphenothiazine derivatives in lithium-ion batteries. Chem Comm. 2014, 50, 5339–5341. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, K.M.; Pasquariello, D.M.; Willstaedt, E.B. N-butylferrocene for overcharge protection of secondary lithium batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1990, 137, 1856–1857. [Google Scholar]

- Golovin, M.N.; Wilkinson, D.P.; Dudley, J.T.; Holonko, D.; Woo, S. Applications of metallocenes in rechargeable lithium batteries for overcharge protection. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1992, 139, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Gélinas, B.; Bibienne, T.; Dollé, M.; Rochefort, D. Electrochemistry and transport properties of electrolytes modified with ferrocene redox-active ionic liquid additives. Can. J. Chem. 2020, 98, 554–563. [Google Scholar]

- Adachi, M.; Tanaka, K.; Sekai, K. Aromatic compounds as redox shuttle additives for 4 V class secondary lithium batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1999, 146, 1256. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.K.; Ai, X.P.; Cao, Y.L.; Yang, H.X. A highly soluble dimethoxybenzene derivative as a redox shuttle for overcharge protection of secondary lithium batteries. Electrochem. Commun. 2007, 9, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.C.; Redfern, P.C.; Curtiss, L.A.; Amine, K. Molecular engineering towards safer lithium-ion batteries: a highly stable and compatible redox shuttle for overcharge protection. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 8204–8207. [Google Scholar]

- Moshurchak, L.M.; Lamanna, W.M.; Bulinski, M.; Wang, R.L.; Garsuch, R.R.; Jiang, J.W.; Magnuson, D.; Triemert, M.; Dahn, J.R. High-potential redox shuttle for use in lithium-ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2009, 156, A309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, W.; Tao, Y.T.; Zhang, Z.C.; Redfern, P.C.; Curtiss, L.A.; Amine, K. Asymmetric form of redox shuttle based on 1, 4-Di-tert-butyl-2, 5-dimethoxybenzene. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2013, 160, A1711. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.C.; Wu, H.M.; Amine, K. Novel redox shuttle additive for high-voltage cathode materials. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 2858–2862. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.H.; Shkrob, I.A.; Wang, P.Q.; Cheng, L.; Pan, B.F.; He, M.N.; Liao, C.; Zhang, Z.C.; Curtiss, L.A.; Zhang, L. 1, 4-Bis (trimethylsilyl)-2, 5-dimethoxybenzene: a novel redox shuttle additive for overcharge protection in lithium-ion batteries that doubles as a mechanistic chemical probe. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 7332–7337. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, W.; Huang, J.H.; Shkrob, I.A.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.C. Redox Shuttles with Axisymmetric Scaffold for Overcharge Protection of Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2016, 6, 1600795. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.J.; Shkrob, I.A.; Assary, R.S.; Zhang, S.; Hu, B.; Liao, C.; Zhang, Z.C.; Zhang, L. Dual overcharge protection and solid electrolyte interphase-improving action in Li-ion cells containing a bis-annulated dialkoxyarene electrolyte additive. J. Power Sources 2018, 378, 264–267. [Google Scholar]

- Odom, S.A. Overcharge protection of lithium-ion batteries with phenothiazine redox shuttles. New J Chem. 2021, 45, 3750–3755. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.P.; Li, X.L.; Yang, M.R.; Chen, W.H. High-safety separators for lithium-ion batteries and sodium-ion batteries: advances and perspective. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 41, 522–545. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.Y.; Richardson, T.J. Overcharge protection for rechargeable lithium batteries using electroactive polymers. ECS Solid State Lett. 2003, 7, A23. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Cao, Y.L.; Yang, H.X.; Lu, S.G.; Ai, X.P. A redox-active polythiophene-modified separator for safety control of lithium-ion batteries. J Polym. Sci. Pol. Phys. 2013, 51, 1487–1493. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.K.; Ai, X.P.; Cao, Y.L.; Yang, H.X. Polytriphenylamine used as an electroactive separator material for overcharge protection of rechargeable lithium battery. J. Power Sources 2006, 161, 545–549. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.L.; Ai, X.P.; Yang, H.X.; Cao, Y.L. A polytriphenylamine-modified separator with reversible overcharge protection for 3.6 V-class lithium-ion battery. J. Power Sources 2009, 189, 771–774. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.Y.; Richardson, T.J. Overcharge protection for high voltage lithium cells using two electroactive polymers. ECS Solid State Lett. 2005, 9, A24. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, L.F.; Ai, X.P.; Cao, Y.L.; Wang, Y.D.; Yang, H.X. A composite polymer membrane with reversible overcharge protection mechanism for lithium ion batteries. Electrochem. Commun. 2005, 7, 589–592. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, W.; Yang, D.; Cheng, J.L.; Li, X.D.; Guan, Q.; Wang, B. Gel-type polymer separator with higher thermal stability and effective overcharge protection of 4.2 V for secondary lithium-ion batteries. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 52966–52973. [Google Scholar]

- Jana, A.; Ely, D.R.; García, R.E. Dendrite-separator interactions in lithium-based batteries. J. Power Sources 2015, 275, 912–921. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.H.; Zhong, L.; Zhang, L.Q.; Kushima, A.; Mao, S.X.; Li, J.; Ye, Z.Z.; Sullivan, J.P.; Huang, J.Y. Lithium fiber growth on the anode in a nanowire lithium ion battery during charging. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 98. [Google Scholar]

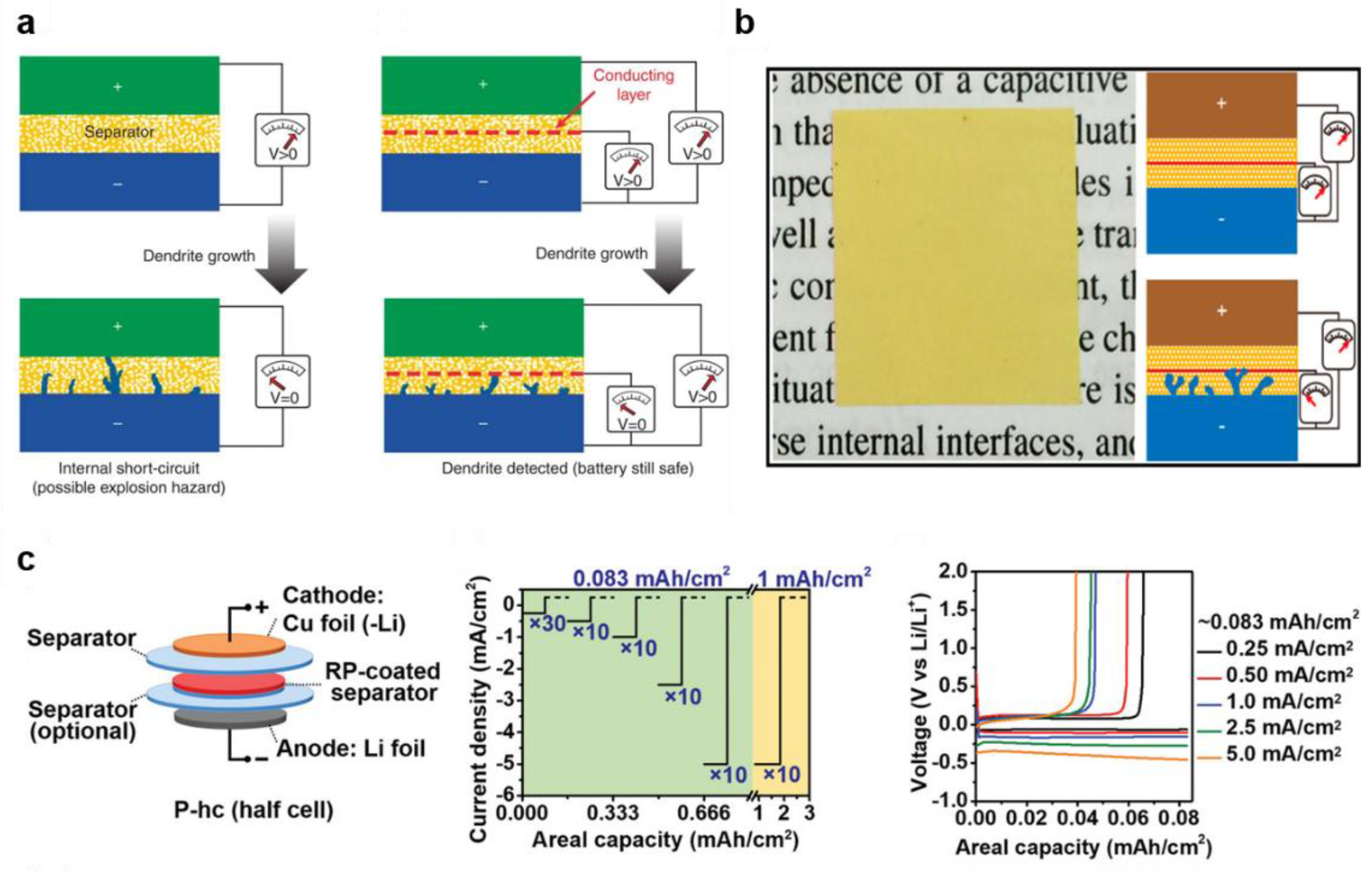

- Wu, H.; Zhuo, D.; Kong, D.S.; Cui, Y. Improving battery safety by early detection of internal shorting with a bifunctional separator. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.C.; Zhuo, D.; Liu, Y.Y.; Cui, Y. All-integrated bifunctional separator for Li dendrite detection via novel solution synthesis of a thermostable polyimide separator. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 11044–11050. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Salvatierra, R.V.; Tour, J.M. Detecting Li dendrites in a two-electrode battery system. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1807405. [Google Scholar]

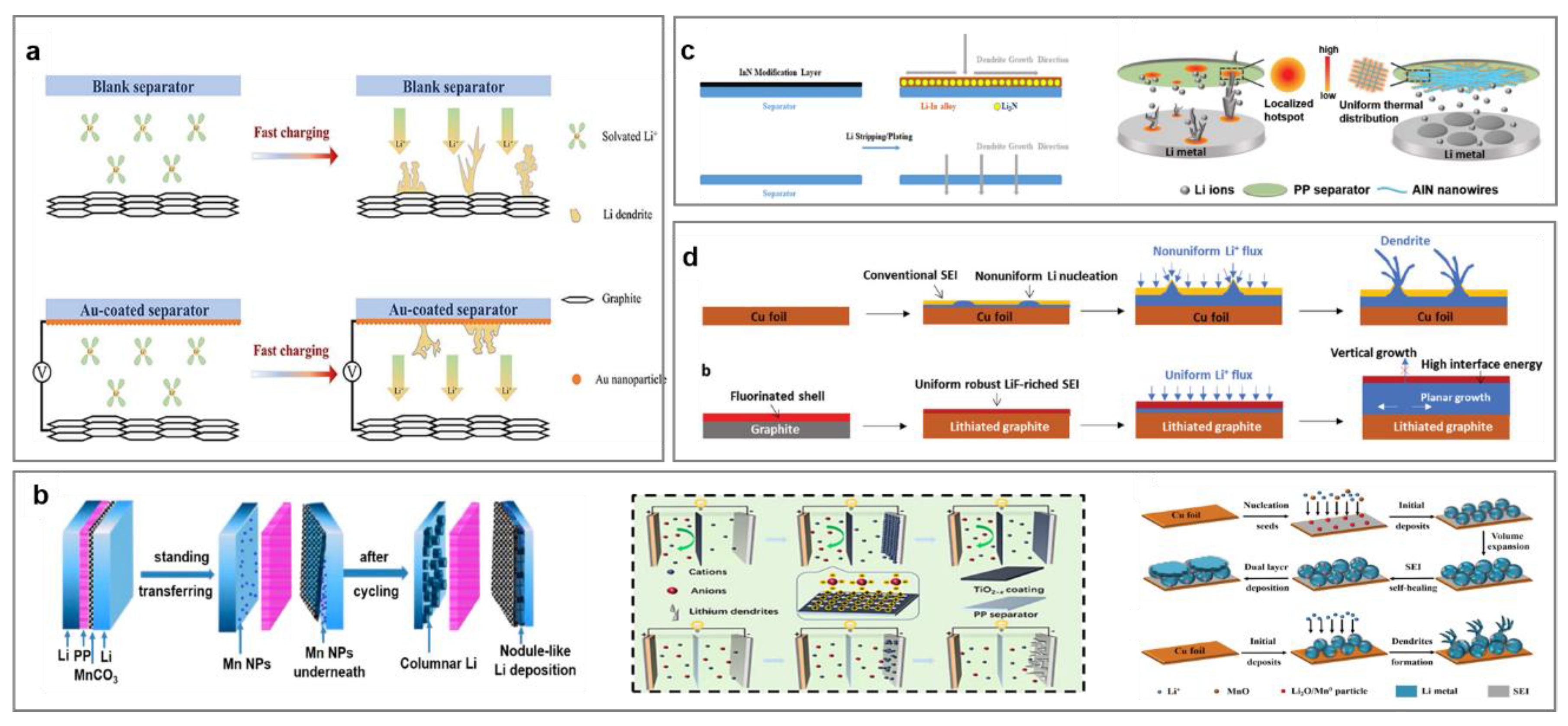

- Lee, H.; Ren, X.D.; Niu, C.J.; Yu, L.; Engelhard, M.H.; Cho, I.; Ryou, M.H.; Jin, H.S.; Kim, H.T.; Liu, J. Suppressing lithium dendrite growth by metallic coating on a separator. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1704391. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, K.; Lu, Z. d.; Lee, H.W.; Xiong, F.; Hsu, P.C.; Li, Y.Z.; Zhao, J.; Chu, S.; Cui, Y. Selective deposition and stable encapsulation of lithium through heterogeneous seeded growth. Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Wu, F.; Chen, N.; Ma, Y.T.; Yang, C.; Shang, Y.X.; Liu, H.X.; Li, L.; Chen, R.J. Reversing the dendrite growth direction and eliminating the concentration polarization via an internal electric field for stable lithium metal anodes. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 9277–9284. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, S.S.; Chen, X.X.; Zhou, P.; Wang, P.C.; Zhou, H. Y; Zhang, W.L.; Xia, Y.C.; Liu, K. Regulating the growth of lithium dendrite by coating an ultra-thin layer of gold on separator for improving the fast-charging ability of graphite anode. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 67, 467–473. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Xiong, S.Z.; Wang, J.L.; Jiao, X.X.; Li, S.; Zhang, C.F.; Song, Z.X.; Song, J.X. Dendrite-free lithium metal anode enabled by separator engineering via uniform loading of lithiophilic nucleation sites. Energy Storage Mater. 2019, 19, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; Liu, F.; Yan, X.L.; Chen, Q.L.; Zhuang, Y.P.; Zheng, H.F.; Lin, J.; Wang, L.S.; Han, L.H.; Wei, Q.L. Dendrite-free reverse lithium deposition induced by ion rectification layer toward superior lithium metal batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2104081. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, C.; Sun, S.; Jang, M.; Park, E.; Son, B.; Son, H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, D.; Paik, U.; Song, T. A robust solid electrolyte interphase layer coated on polyethylene separator surface induced by Ge interlayer for stable Li-metal batteries. Electrochim. Acta. 2021, 370, 137703. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; Liu, F.Q.; Gao, J.; Zhou, W.; Huo, H.; Zhou, J.J.; Li, L. Low-cost regulating lithium deposition behaviors by transition metal oxide coating on separator. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2007255. [Google Scholar]

- An, Q.; Liu, Q.; Wang, S.M.; Liu, L.X.; Wang, H.; Sun, Y.J.; Duan, L.Y.; Zhao, G.F.; Guo, H. Oxygen vacancies with localized electrons direct a functionalized separator toward dendrite-free and high loading LiFePO4 for lithium metal batteries. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 75, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; Liu, F.Q.; Hu, Z.Y.; Gao, J.; Zhou, W.D.; Huo, H.; Zhou, J. J; Li, L. Realizing dendrite-free lithium deposition with a composite separator. Nano Lett. 2020, 20, 3798–3807. [Google Scholar]

- Sim, R.; Su, L.S.; Dolocan, A.; Manthiram, A. Delineating the impact of transition-metal crossover on solid-electrolyte interphase formation with ion mass spectrometry. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2311573. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, M.; Wang, C.Y.; Fan, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xin, S.; Yue, J.; Zeng, X.X.; Liang, J.Y.; Song, Y.X.; Yin, Y.X. In situ derived mixed ion/electron conducting layer on top of a functional separator for high-performance, dendrite-free rechargeable lithium-metal batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2301638. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.T.; Qu, W.J.; Hu, X.; Qian, J.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Lu, H.; Du, H.L.; Wu, F.; Chen, R.J. Induction/inhibition effect on lithium dendrite growth by a binary modification layer on a separator. ACS Appl. Mater. 2022, 14, 44338–44344. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Wu, Q.; Liu, L.W.; Li, G.C.; Yang, L.J.; Wang, X.Z.; Ma, Y.W.; Hu, Z. Thermally conductive AlN-network shield for separators to achieve dendrite-free plating and fast Li-ion transport toward durable and high-rate lithium-metal anodes. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2200411. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, C.Y.; Yang, C.Y.; Eidson, N.; Chen, J.; Han, F.D.; Chen, L.; Luo, C.; Wang, P.F.; Fan, X.L.; Wang, C.S. A highly reversible, dendrite-free lithium metal anode enabled by a lithium-fluoride-enriched interphase. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1906427. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.L.; Fu, S.Y.; Zhao, T.; Qian, J.; Chen, N.; Li, L.; Wu, F.; Chen, R.J. In situ formation of a LiF and Li–Al alloy anode protected layer on a Li metal anode with enhanced cycle life. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 1247–1253. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Pei, A.; Lee, H.R.; Kong, B.; Liu, N.; Lin, D.C.; Liu, Y.Y.; Liu, C.; Hsu, P.C.; Bao, Z.N. Lithium metal anodes with an adaptive “solid-liquid” interfacial protective layer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 4815–4820. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Li, Q.Y.; Bi, Y.J.; Cai, M.; Dunn, B.; Glossmann, T.; Liu, J.; Osaka, T.; Sugiura, R.; Wu, B.B.; Yang, J.H.; Zhang, J.G.; Whittingham, M.S. Understanding and applying coulombic efficiency in lithium metal batteries. Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 561–568. [Google Scholar]

- Raghavab, A.; Kiesel, P.; Sommer, L.W.; Schwartz, J.; Lochbaum, A.; Hegyi, A.; Schuh, A.; Arakaki, K.; Saha, B.; Ganguli, A.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, C.; Hah, H.J.; Kim, S.; Hwang, G.-O.; Chuang, G.-C.; Choi, B.; Alamgir, M. Embedded fiber-optic sensing for accurate internal monitoring of cell state in advanced battery management systems part 1: Cell embedding method and performance. J. Power Sources 2017, 341, 466–473. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, S.; Birke, K.P.; Kuhn, R. Fast thermal runaway detection for lithium-ion cells in large scale traction batteries. Batteries 2018, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Stefanopoulou, A.G.; Siegel, J.B. Early detection for li-ion batteries thermal runaway based on gas sensing. ECS Trans. 2019, 89, 85–97. [Google Scholar]

| Time | Type | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| April 2023 | A lithium battery container caught fire in the industrial park in Gothenburg, Sweden | Massive property damage |

| May 2023 | A 5MW energy storage facility caught fire in East Hampton, New York, USA | Massive property damage |

| June 2023 | A fire broke out at an electric bicycle shop in Chinatown, New York City | Four people died, and two were seriously injured |

| July 2023 | A fire broke out at the container energy storage station in Longjing District, Taichung City, Taiwan Province | Massive property damage |

| August 2023 | A storage energy cabinet suddenly caught fire in the Guangtong Logistics Park in Zhuhai, Guangdong Province | Massive property damage |

| August 2023 | A lithium battery failure in an electric scooter and caused a fire in a residential building in Los Angeles, California | Two people died, and multiple people were seriously injured |

| September 2023 | A fire broke out in an apartment building due to overheating of lithium batteries in personal mobility devices in London, UK | Resulting in significant property damage, many people received treatment for smoke inhalation |

| February 2024 | A lithium-ion battery from an electric bicycle caused an apartment fire in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City | One journalist died, and multiple people were seriously injured |

| May 2024 | A fire broke out at a 70 MW agricultural-photovoltaic complementary energy storage power station in Hainan Province | A group of battery prefabricated containers was burned |

| Number | Standard | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | GB/T 36276-2023 | The phenomenon of uncontrollable temperature rise caused by exothermic reactions inside the battery cell |

| 2 | IEC 62619-2022 | Uncontrollable and rapid temperature rise caused by exothermic reactions within the battery cell |

| 3 | UL 1973-2022 UL 9540A |

An event in which an electrochemical battery uncontrollably raises its temperature through self-heating. Thermal runaway occurs when the heat generated by the battery exceeds the heat it can dissipate. This can lead to fires, explosions, and gas emissions |

| 4 | GB/T 36276-2023 | The phenomenon where thermal runaway in a battery cell within a battery module triggers thermal runaway in adjacent or other cells |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).