Introduction

The Paradigmatic Mountain Complex and the Emergence of Mountain Science: the paradigmatic mountain complex positions mountain science as one of the most recently emerging scientific fields globally. In a broad sense, mountain science has captivated various scholars, while in a more specific sense, it is recognized as a discipline that developed in the late 20th century and early 21st century.

A comprehensive and cross-sectional study of mountain science highlights the rapid rise in scientific output during contemporary centuries. Research conducted by Körner (2009) analyzed publications with a mountain or alpine focus from the Web of Science between 1900 and 2008, defining the concept of "alpine" strictly from a biogeographical perspective—as the terrain covered by vegetation above the climatic tree line, specifically at altitudes where trees can no longer grow.

Out of 14,226 publications analyzed, 56% originated from a select group of countries, with the following distribution among authors:

- -

20% from the United States

- -

15% from Switzerland

- -

11% from France

- -

10% each from Italy and Germany

- -

9% from Austria

- -

6% from Canada

- -

5% from the United Kingdom

- -

4% each from New Zealand and Australia

- -

3% each from Norway, China, and Spain

- -

2% each from Sweden, Japan, the Netherlands, and Russia

- -

1.3% from the Czech Republic

- -

1.2% from Scotland

- -

1.1% each from India and Slovakia

- -

1% from Denmark

- -

0.9% each from Belgium and Poland

- -

0.8% from Finland

Scientific Productivity in Mountain Research: when adjusted for population size, Switzerland ranks first, with 282 mountain-related publications per million inhabitants. Other nations exhibit varying levels of research output:

- -

New Zealand – 151 publications per million

- -

Austria – 145 publications per million

- -

Norway – 94 publications per million

- -

A significant gap follows, with France and Italy each reporting 24 publications per million and the United States at 10 publications per million.

Switzerland as the Global Leader in Mountain Science: a key finding in mountain research is that Switzerland stands as the global leader in the field. This prominence is largely attributed to the country's continuous and uninterrupted scientific development. Switzerland has maintained its leadership status due to several factors, including:

- -

A stable geopolitical position, free from significant internal or external conflicts

- -

A long-standing tradition of mountain-focused scientific research

- -

Economic prosperity, facilitated by substantial foreign investment

The Historical Legacy of Mountain Science: mountain science has deep historical roots in Switzerland, with a remarkable chronology dating back to the 16th century. Some of the most influential encyclopedic works on high-altitude regions include:

- -

Conrad Gessner (1555) – A volume dedicated to vegetation elevation changes in mountainous regions (Zürich)

- -

Horace-Bénédict de Saussure (circa 1800) – A seminal work on atmospheric sciences, primarily focused on mountain environments (Geneva)

- -

Carl Schröter (1906) – A comprehensive handbook on alpine plant ecology

As a result of Switzerland’s sustained contributions, mountain science has evolved into a global paradigm, and today, all nations acknowledge the importance of mountain research as well as its professional and technical applications.

(Körner, 2009)

Key Contributors and Global Perspectives in Mountain Science: as leading figures in mountain science, Professors Ives and Messerli have actively supported numerous initiatives aimed at transforming mountain environments and quantifying the impact of human activities on mountain ecosystems. Several mountain science researchers, including the authors of the study under discussion, have made significant efforts to bridge the gap between theoretical frameworks and practical applications in mountain science—specifically aligning scientific research with professional and technical mountain-related activities.

One clear conclusion emerges: international cooperation in supporting mountain research must be significantly strengthened, as its benefits extend to all people across the planet.

(Ives & Messerli, 1990)

The Global Importance of Mountain Communities and Ecosystems: the relevance of mountain communities and ecosystems is further emphasized by the United Nations’ dedication of specific years to mountain-related causes over the past three decades. During global events focused on mountain regions, numerous researchers have highlighted the threats facing these areas, including:

- -

Severe natural disasters

- -

Species extinction due to accelerated habitat deterioration caused by forced urbanization

- -

The rapid destruction of mountain fauna, flora, land, and pastures

(Jansky et al., 2002)

The Role of the United Kingdom in Mountain Science: another key hub for mountain research is the United Kingdom, particularly Scotland, where research efforts focus on global transformations in socio-ecological mountain systems. British researchers emphasize global change and mountain sustainability, with conferences held in the UK revealing a lack of representation in mountain studies for regions such as Africa, South America, and South and Southeast Asia.

At a global level, research on mountain environments is predominantly centered on biophysical and social studies, with a strong emphasis on:

- -

Natural resources

- -

Land use and resilience

- -

The mountain water-energy-food nexus

(Gleeson et al., 2016)

Methodology

Analysis of Scientific, Professional, and Technical Activities in European Mountain Regions (2021-2022): this study examines the evolution of scientific, professional, and technical activities in European mountain regions during the 2021-2022 period. The European mountain area represents the most advanced research sector globally, accounting for over 60% of studies conducted in developed countries. Existing data indicate that European mountain regions maintain a generally favorable environment for scientific, professional, and technical entrepreneurship.

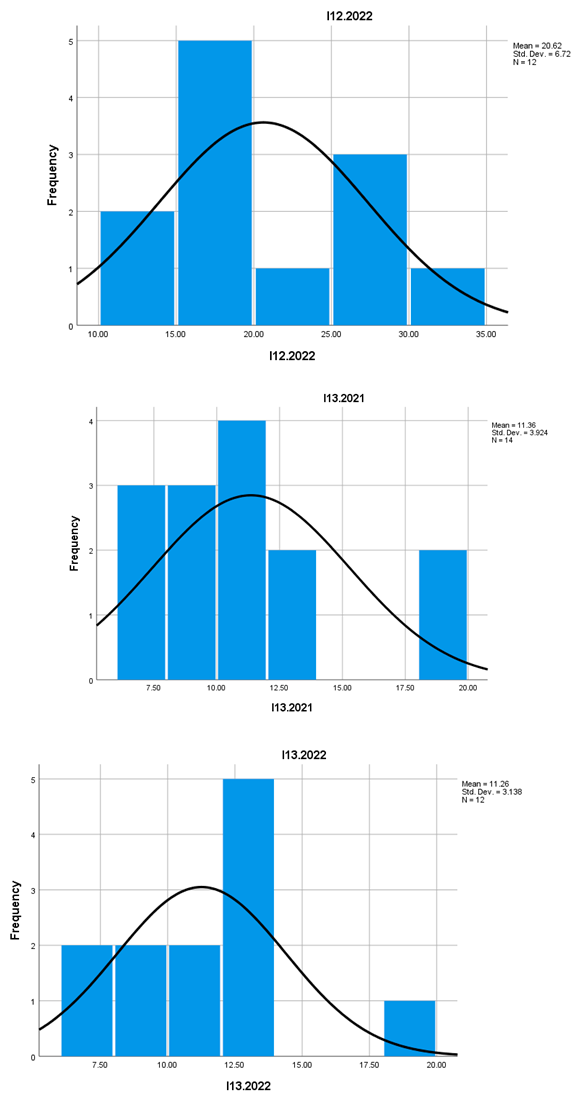

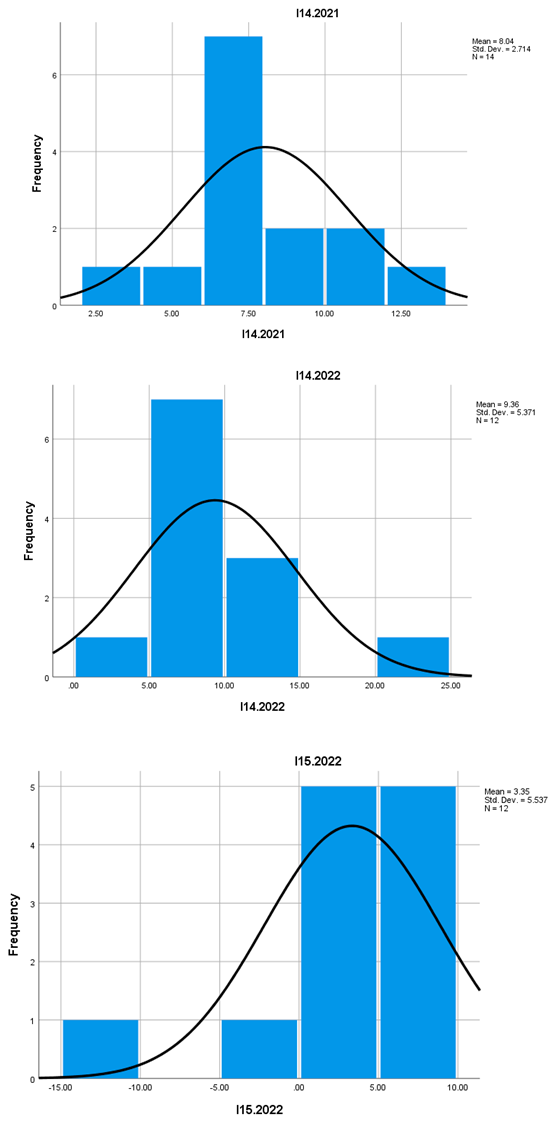

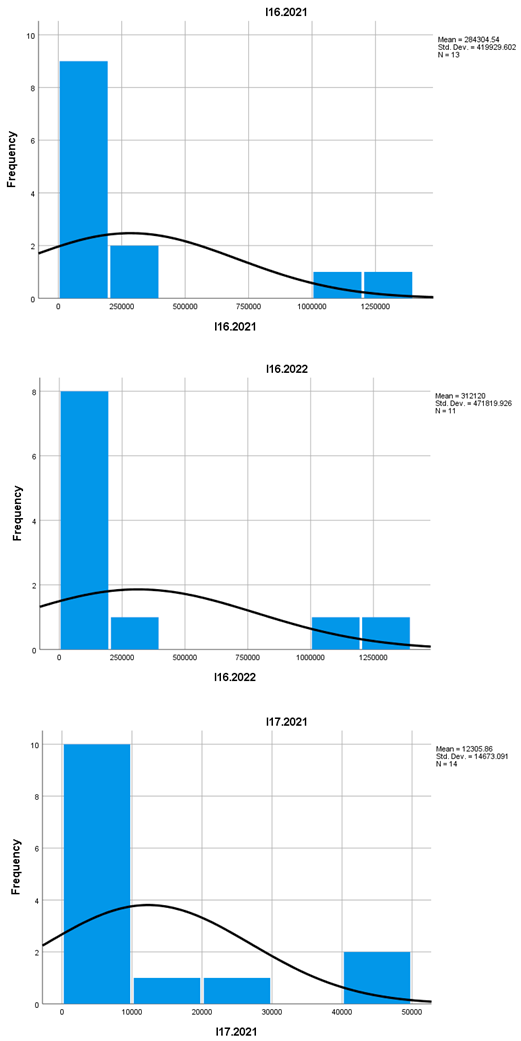

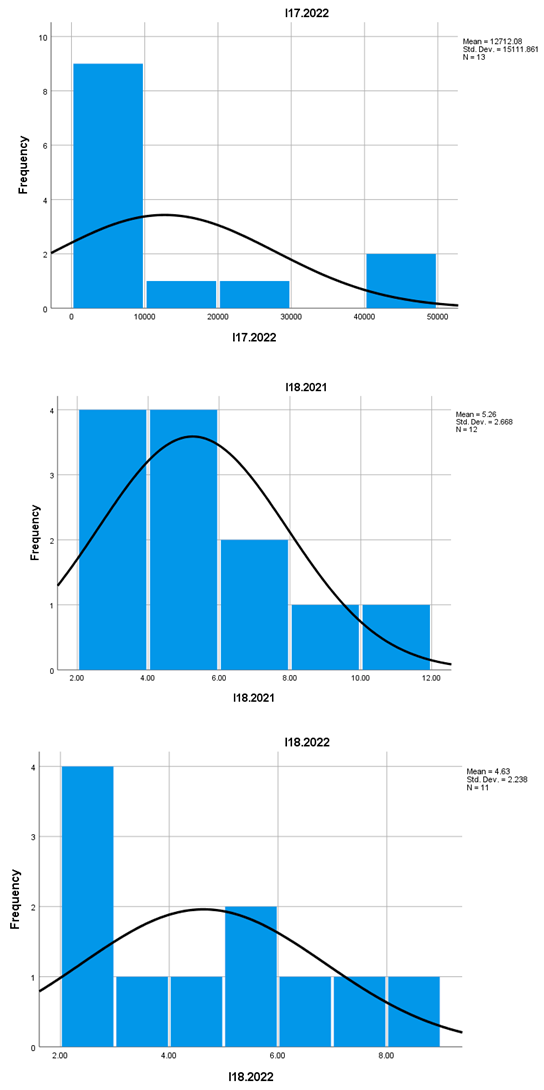

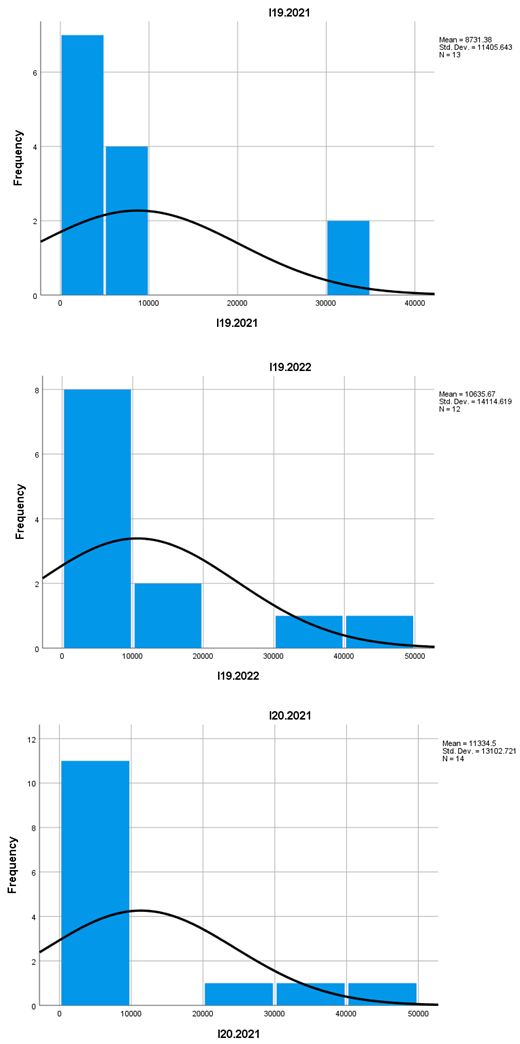

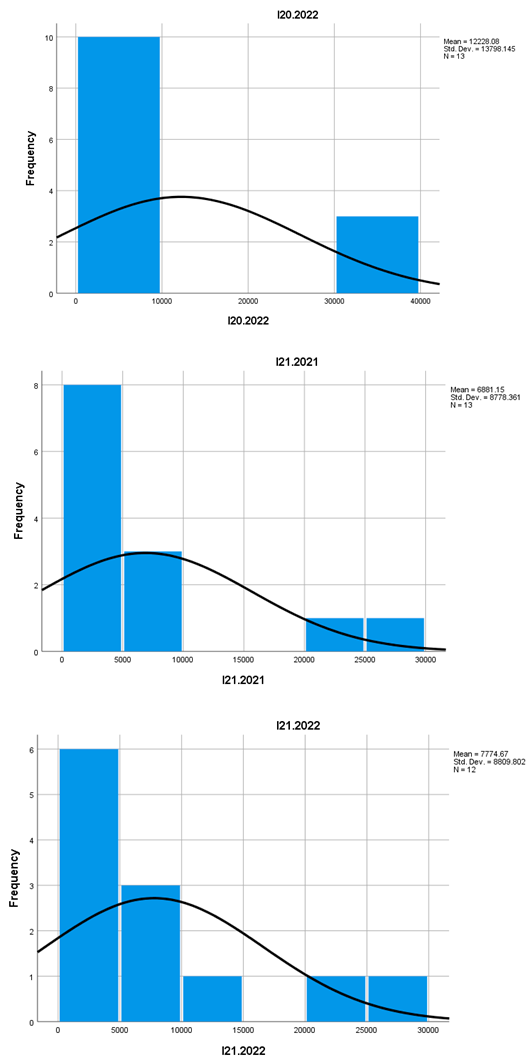

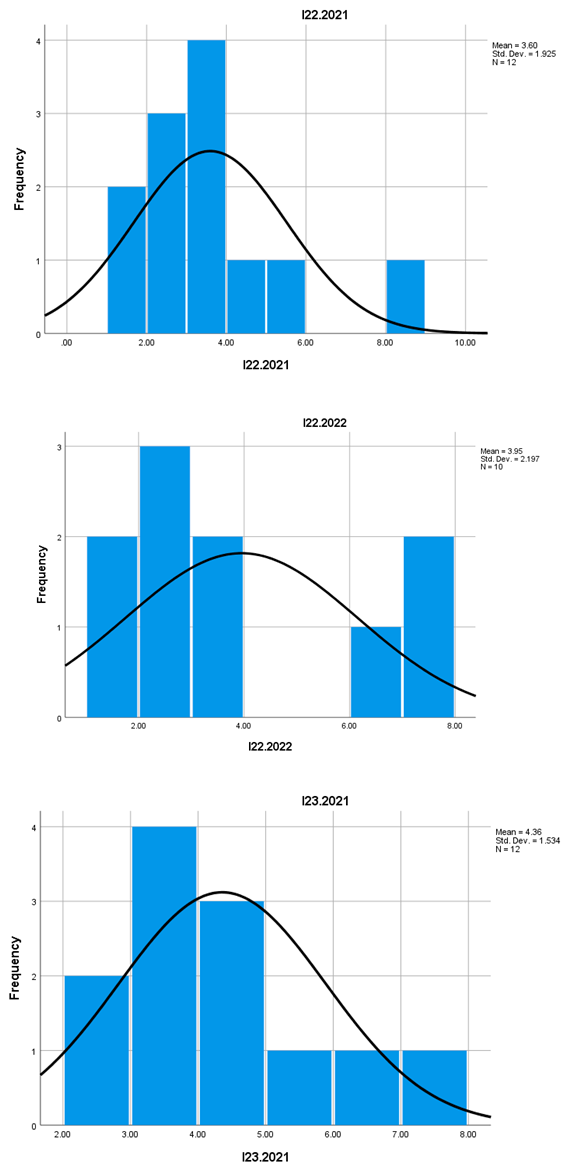

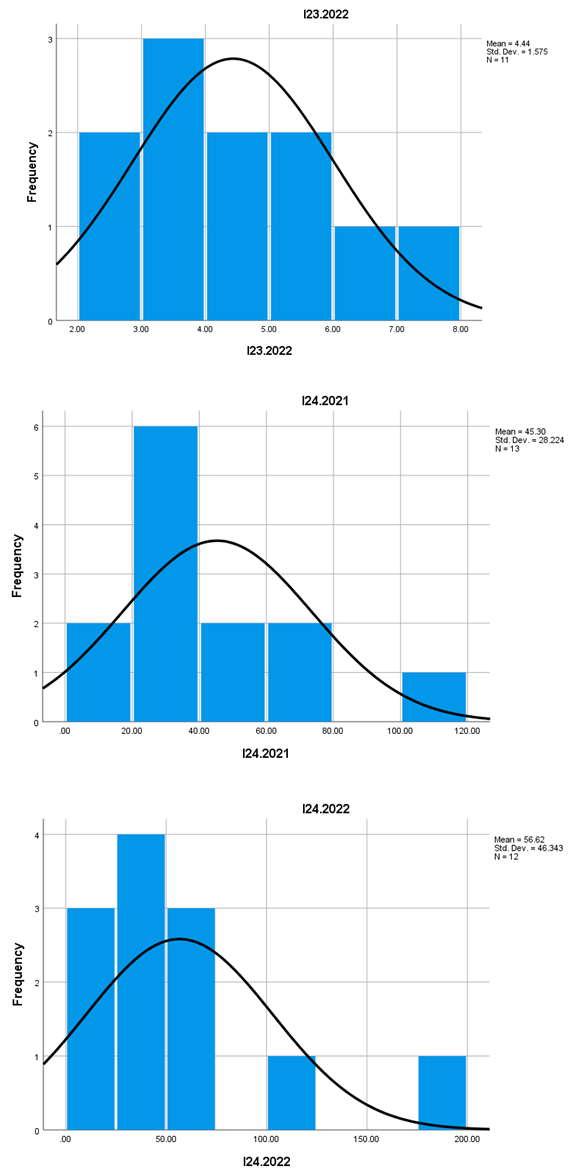

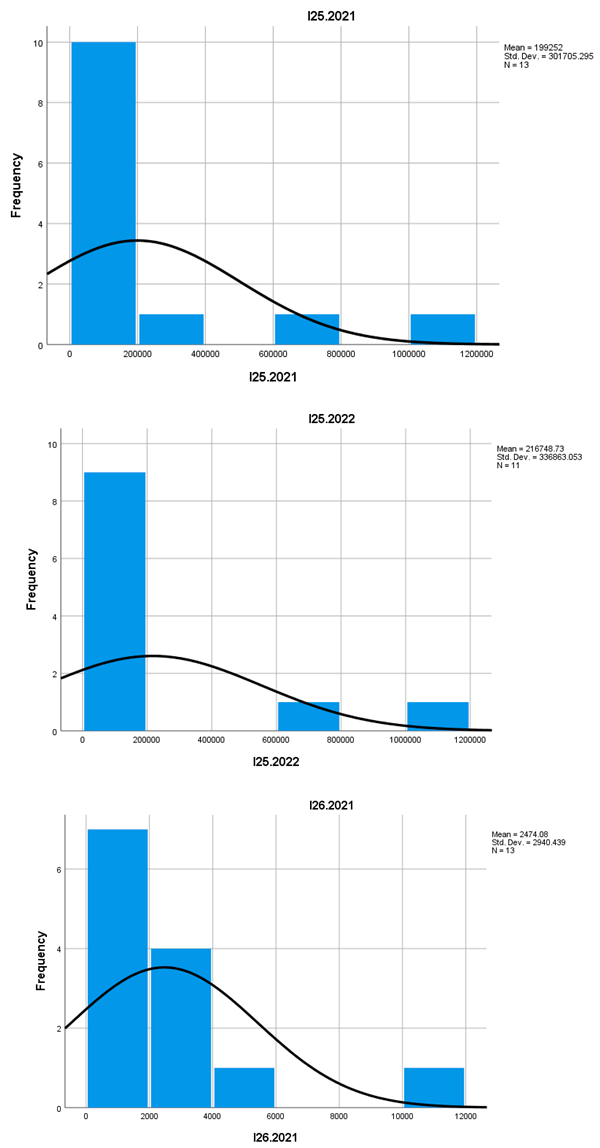

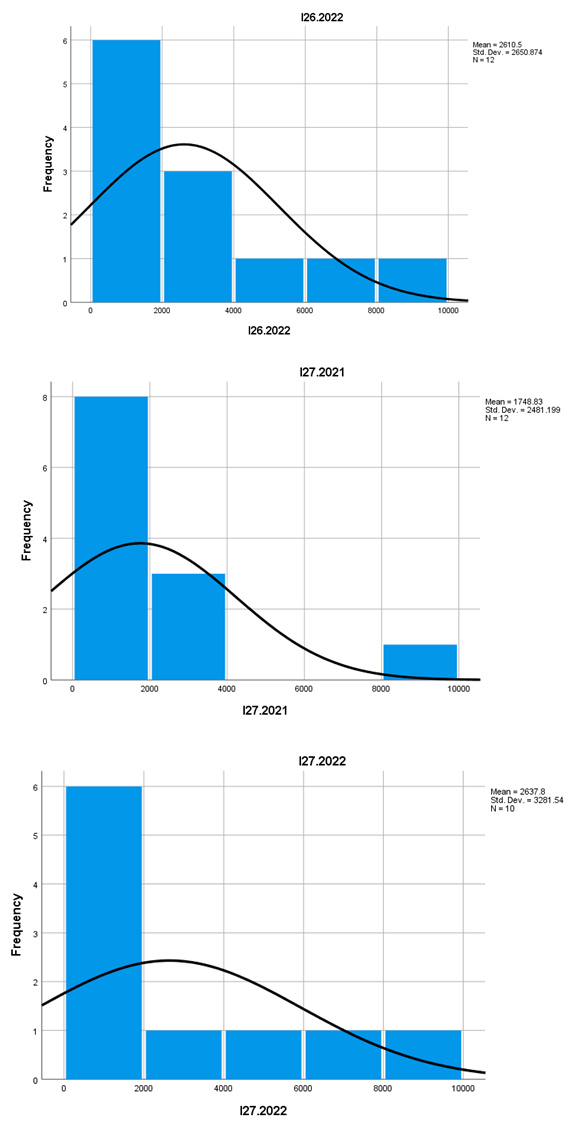

Data sourced from Eurostat were processed using Excel and SPSS, with 2021 established as the statistical reference year. The descriptive frequency analysis was based on Eurostat indicators related to mountain entrepreneurship, which served as dependent variables. A series of histograms was generated—two for each of the 28 Eurostat indicators—with their detailed explanations available at [DOI:

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14713867].

Results

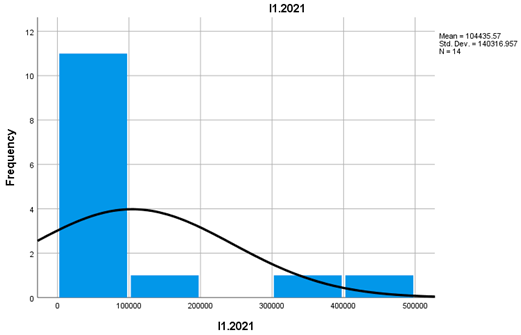

Fluctuations of the statistical values for population of active enterprises of science, professional and technical activities in 2021 and 2022 (I1.2021 and I1.2022) present different values, as follows (enumerated in 2021 and 2022 order): Mean - 104435.57, 118244.67; Std. Error of Mean - 37501.284, 45652.208; Median - 52059.00, 49917.50; Mode – 3157, 2786; Std. Deviation - 140316.957, 158143.886; Variance - 19688848434.264, 25009488656.970; Skewness - 1.980, 1.731; Std. Error of Skewness - .597, .637; Kurtosis - 2.781, 1.727; Std. Error of Kurtosis - 1.154, 1.232; Range – 440800, 466438; Minimum – 3157, 2786; Maximum – 443957, 469224; Sum – 1462098, 1418936; Percentiles 50 - 52059.00, 49917.50.

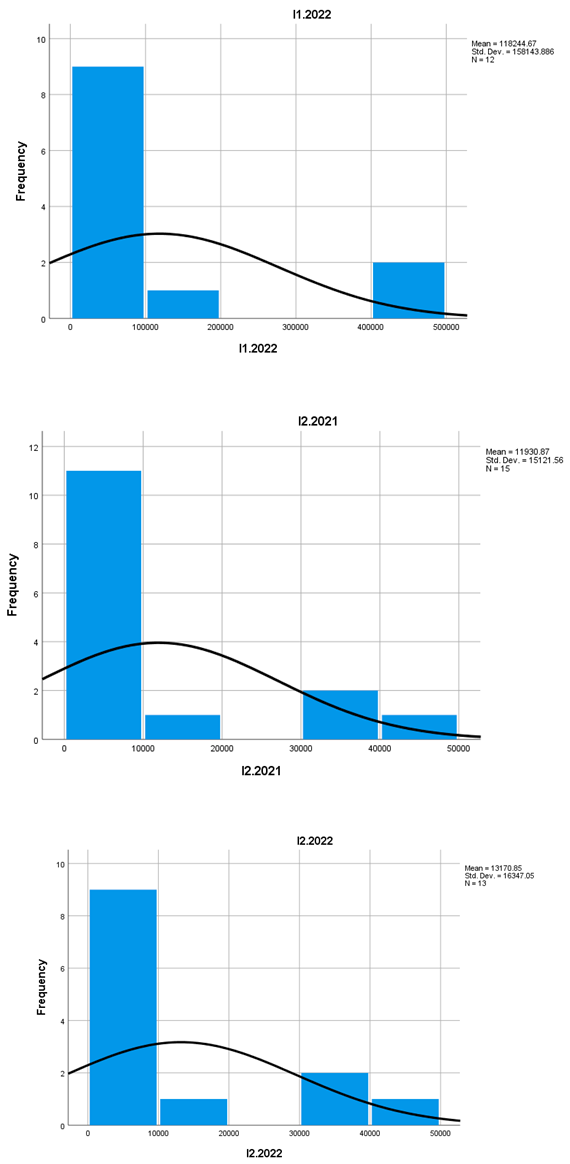

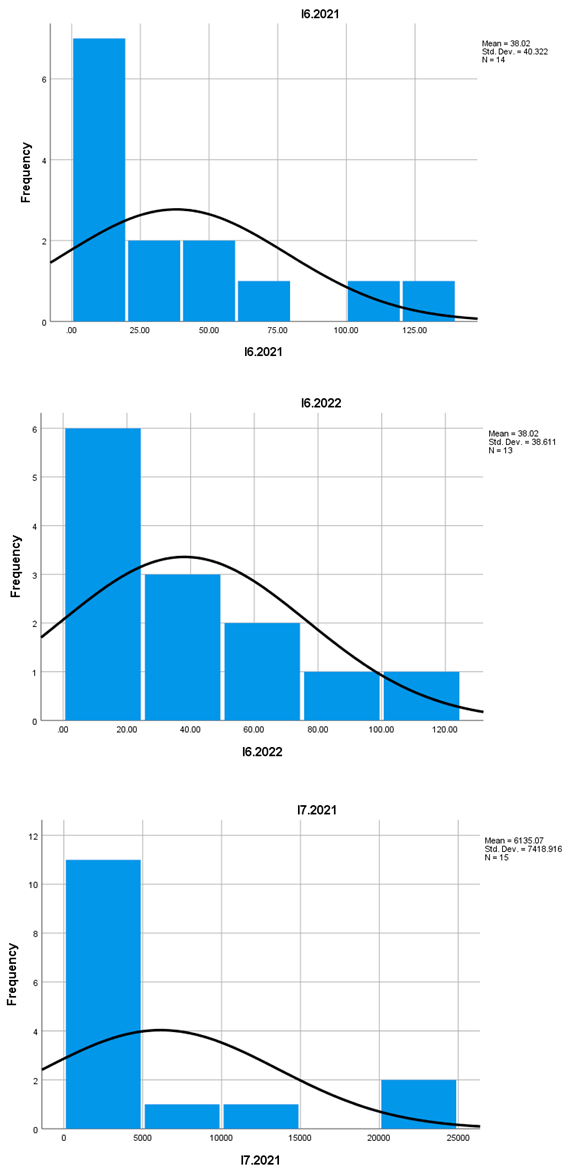

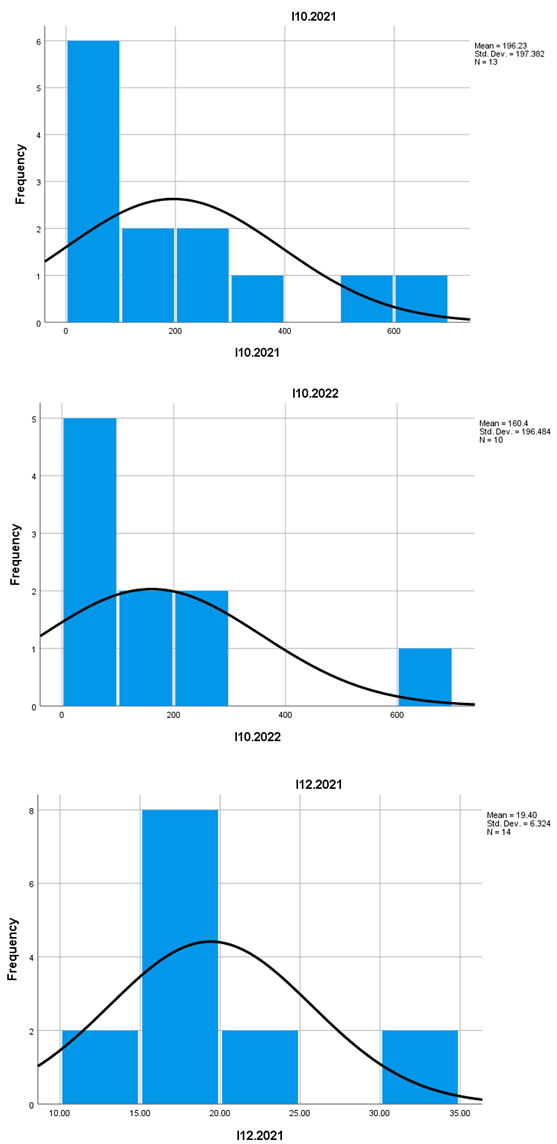

Analysis of Histograms from the following (I1.2021–I28.2022) show that the majority of the analyzed histograms exhibit a right-skewed (positively skewed) distribution, indicating that most values are concentrated at the lower end, while fewer values extend toward the right. As previously noted, some distributions appear bimodal, suggesting the presence of two peaks within the data.

The occurrence of bar-type distributions with gaps implies that certain variables may be categorical in nature or contain discrete numerical values. Additionally, a few histograms display isolated bars positioned far from the primary cluster, which may indicate potential outliers that warrant further examination.

A comparative analysis of the histograms for 2021 and 2022 reveals differences in distributions, pointing to possible temporal trends. Some histograms feature isolated bars distant from the main cluster, suggesting that these values represent rare occurrences within the dataset. Other histograms exhibit two peaks, which may indicate that the data originate from two distinct groups or subgroups. Furthermore, a subset of histograms resembles normal (Gaussian) distributions, characterized by a symmetrical bell-shaped curve.

Regarding variability, certain distributions are widely dispersed, reflecting high variability, whereas others are more tightly clustered, indicating lower variability.

Key Indicator Trends and Implications: Specifically, significant indicators such as I1, I2, I5, I6, I7, I10, I16, I17, I19, I20, I21, I25, I26, and I27 display left-oriented asymptotic tendencies, with predominant development occurring during the initial period under analysis. This trend suggests that the sectors in question are likely to experience a decline in the forthcoming period.

Conversely, indicators I8, I12, I13, I14, I22, I23, I24, and I28 exhibit Gaussian-type histogram shapes, implying that these indicators maintain equilibrium. However, an in-depth interpretation of their significance still points to an overall reduction in activity over time.

The remaining indicators, with the exception of I4, which follows a linear growth pattern, display rightward-oriented curves. This suggests that both in formal and substantive terms, the situation within these sectors (I3, I15) is expected to improve.

Implications for the Mountain Region's Economic and Employment Landscape: Based on the analysis across all indicators, the number of enterprises operating within the studied sectors in the mountain region remains relatively stable, with a slight decline observed during the second period. The establishment of new enterprises remains a challenging objective within the analyzed timeframe.

Additionally, employment levels show a consistent downward trend, indicating that employability constraints will likely impact the long-term development of scientific and technical activities within the mountain region.

Conclusion

The findings of this study underscore the critical role of European mountain regions in the advancement of scientific, professional, and technical research. Despite Switzerland’s global leadership in mountain science and a strong research presence in other European nations, the analysis indicates emerging challenges, particularly in terms of entrepreneurial sustainability and employment trends. While some scientific and technical sectors maintain equilibrium, a general decline in activity is observed across key indicators.

A significant takeaway is that mountain-related economic and employment landscapes are experiencing structural shifts, with enterprise growth struggling to keep pace with broader global trends. This calls for targeted interventions, including:

- -

Strengthening international research collaboration

- -

Increasing funding for mountain-related enterprises

- -

Developing long-term employment strategies for mountain professionals

Given the ongoing environmental and socio-economic pressures on mountain ecosystems and communities, policymakers, researchers, and industry stakeholders must work together to ensure the resilience and sustainability of mountain science and its practical applications.

This paper has been corrected with the assistance of artificial intelligence.

References

- Körner, C. (2009). Global statistics of “mountain” and “alpine” research. Mountain Research and Development, 29(1), 97-102. [CrossRef]

- Ives, J. D., & Messerli, B. (1990). Progress in theoretical and applied mountain research, 1973-1989, and major future needs. Mountain Research and Development, 101-127. [CrossRef]

- Jansky, L., Ives, J. D., Furuyashiki, K., & Watanabe, T. (2002). Global mountain research for sustainable development. Global Environmental Change, 12(3), 231-239. [CrossRef]

- Gleeson, E. H., von Dach, S. W., Flint, C. G., Greenwood, G. B., Price, M. F., Balsiger, J., ... & Vanacker, V. (2016). Mountains of our future earth: Defining priorities for mountain research—A synthesis from the 2015 Perth III conference. Mountain research and development, 36(4), 537-548. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).