1. Introduction

The anthropogenic ecological crisis is causing many kinds of loss and damage, which can evoke various kinds of sadness and grief. This is currently studied most often under the framework of ecological grief (Cunsolo and Ellis 2018; J. T. Barnett 2022), while other formulations include environmental grief (Kevorkian 2004; 2020) and Albrecht’s neologism solastalgia (Albrecht et al. 2007; Galway et al. 2019). Recent scholarship has aimed to clarify the various kinds of losses and grief which may be present in ecological grief (Pihkala 2024e). These range from tangible to intangible loss (Tschakert et al. 2019); from evident losses to ambiguous loss (Boss 2022); and from one-time losses to continuous, nonfinite losses (Pihkala 2024e). Ecological grief can be related to many temporalities (Randall 2009; Stanley 2023). Furthermore, it is often socially contested or at least not well supported, leading to disenfranchised grief (Pihkala 2024e).

Scholarship on ecological grief is now growing fast, but for a long time it was an under-studied phenomenon (for reviews of scholarship, see Pihkala 2024e; Benham and Hoerst 2024). Both local and global environmental changes can evoke ecological grief. A major part of all this is climate grief, which means sorrow about various negative impacts of anthropogenic climate change (Comtesse et al. 2021; Pihkala 2024b). Many phenomena can be evaluated by using various terms and frameworks, such as disasters which have been at least partly made worse by climate change: relevant frameworks include disaster studies, trauma research, grief and bereavement research, and research on community resilience and adaptation (see e.g., Chen et al. 2020; Doppelt 2023).

Researchers and counselors have only recently started to apply traditional research on grief and bereavement more extensively to ecological grief. Several frameworks have been drawn from, such as Worden’s tasks of mourning framework (Randall 2009; Worden 2018) and Kübler-Ross’ stages of grief model (L. Jones et al. 2021; Kübler-Ross and Kessler 2005). One of the influential frameworks in contemporary grief research is the Dual Process Model of Coping with Bereavement (DPM) (Stroebe and Schut 1999; 2001; 2010; 2015; 2016; 2021), and this article sets to apply it to ecological grief. There is not much earlier research on the DPM and ecological grief (see, however, Pihkala 2022; Bailey & Gerrish 2024), and several central features of the DPM seem important in relation to ecological grief. As will be discussed below in more detail, the DPM distinguishes between Loss-Oriented (LO) tasks and Restoration-Oriented (RO) tasks, and emphasizes the importance of oscillation between these two. There are some existing applications of the DPM into societal matters, but not many, and the basic models of the DPM only extend currently to family-level interaction.

This article engages with applications of grief theory into social spheres (D. Harris 2022; 2025) and extends the DPM into an eco-social context. Ecological grief is not characterized merely as an individual phenomenon: its intimate connections with social and structural factors is emphasized (see also Walter 2024). Following Harris, grief itself is seen as “a broad, interdimensional experience that can be both generated and experienced at micro, mezzo, and macro levels” (D. Harris 2022, 573). It is pointed out that issues of culpability, guilt, and responsibility greatly complicate engagement with ecological grief on all levels (see Menning 2017; Jensen 2019), and the relationship between this and the DPM is discussed. The article emphasizes that grief and grievance are intimately connected in the context of ecological grief (Pihkala 2024e; Ranjan 2024).

The article draws from interdisciplinary research about ecological grief and other eco-emotions, as well as scholarship on religion and ecology. Religious and spiritual communities have many possibilities for engaging with ecological grief (Hessel-Robinson 2012; Menning 2017; Pihkala 2024f), and this is explored in relation to dynamics of the DPM such as Loss-Oriented and Restoration-Oriented tasks.

2. The Dual Process Model of Coping with Bereavement

The DPM was generated in the late 1990s by experienced grief scholars Stroebe and Schut because of several perceived needs. In those times, there was still much emphasis in many grief approaches on “the grief work hypothesis”: roughly, the idea that grief is about confronting the loss. This was sometimes connected to the old idea that grief is about removing emotional bonds to that which is lost (for discussions, see e.g Worden 2018; Bonanno et al. 2002; Parkes and Prigerson 2013); during the last decades, the framework of continuing bonds has strongly replaced this idea (Root and Exline 2014). Stroebe and Schut wanted a create a model where also the other impacts of bereavement on life were taken into account: secondary stressors and various things that need attention in the aftermath of a loss. The need of mourners to sometimes distance themselves from grieving was also integrated, and it was pointed out that avoidance is not always maladaptive (Stroebe and Schut 1999; 2010).

Central features of the DPM are 1) separation between two kinds of engagements, Loss-Oriented (LO) and Restoration-Oriented (RO), and 2) oscillation between them. The two categories point to differences in emphasis. Loss-Orientation means that sometimes the mourner engages more directly with the loss and feelings related to it.

1 Restoration-Orientation means that sometimes the mourner focuses on what needs to be done because of the loss: for example, practical re-organization of daily life or learning new roles and identities because of the needs generated by the loss. The naming of Restoration-Orientation has produced some confusion, because people can interpret that it is geared towards restoration in the sense of recovery and adjustment after loss. However, Stroebe and Schut explicitly argue that this is not the case: restoration in the name of RO is not “an outcome variable” (Stroebe and Schut 1999, 214). Both LO and RO tasks are needed for adjustment.

Oscillation means movement between the two categories of tasks, either consciously or as driven by various forces, either internal or external. Stroebe and Schut (1999; 2010) argue that oscillation not only happens, but

should happen in grief processes, so that people could cope and adjust better. What was classically called “grief work” is needed, but it is too heavy for people to stay with the often painful feelings constantly, and anyway daily life demands attention.

2 Thus, one part of oscillation happens between engagement and disengagement with the loss. However, people can also learn skills of actively focusing on different kinds of coping tasks, such as between active commemoration (a LO task) and active reworking of one’s daily life (a RO task). Engagement with one task can support engagement with another one as well. For example, engaging with strong emotions of sadness can liberate energy afterwards to reorganize daily living, and engagement with learning new required skills can bring feelings of efficacy which increase capacity to engage also with losses (e.g., Stroebe and Schut 2010; Larsen, Hybholt, and O’Connor 2024).

A practical aim is to build balance between the various tasks and one’s responses to them. Even while people are different and grieve differently, Stroebe and Schut (1999; 2010; 2016) argue that it is problematic if there is no movement between LO and RO. People suffer if they get stuck in heavy grieving for overly long time without respite; and people’s adjustment also suffers if they do not face any of the hard feelings and only practice RO. Social and cultural factors influence people’s capabilities and motivations to engage with either category of tasks. There can be gendered emotion norms and socialization here. Stroebe and Schut (1999, 218-219) point out that women tend to include more emphasis on LO, while men tend to focus on RO, at least in industrialized societies.

By their categorization of RO tasks, Stroebe and Schut were able to bring more nuance to grief and bereavement research. The DPM quickly became a much-discussed theory in grief and bereavement research (Fiore 2021; Stroebe and Schut 2010). Its major feature of oscillation evoked much attention, too, but it was found to be a difficult phenomenon to study in practice, because the relationship between LO and RO activities can be quite nuanced and complicated. Critical discussion on the DPM has explored these complex issues (Shear 2010; Carr 2010). A recent empirical study observed that for its participants, the tasks were more entangled in the first, acute phase of bereavement, and become further differentiated over time (Larsen, Hybholt, and O’Connor 2024).

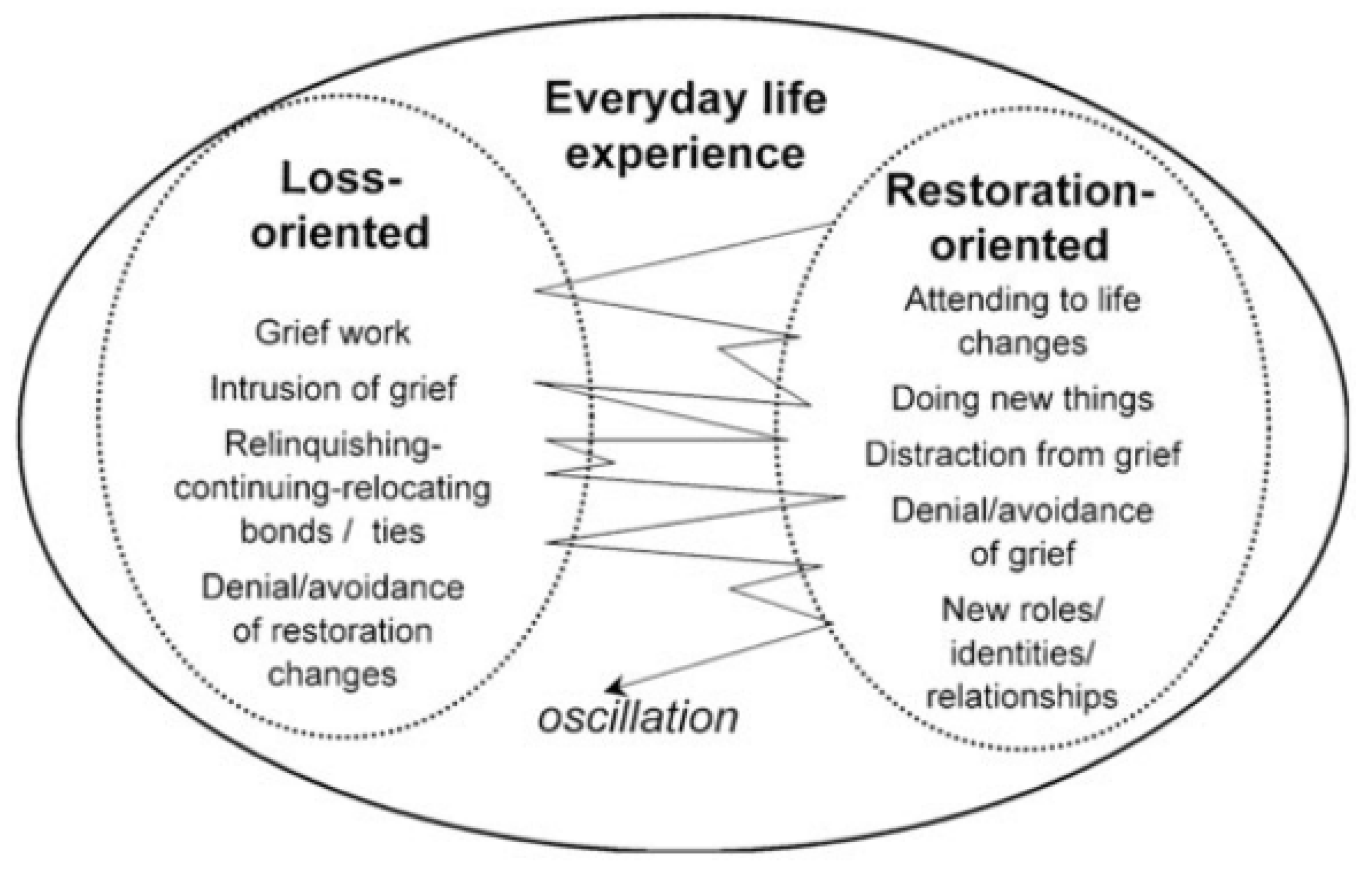

The first version of the DPM used general terms to describe the major contents in LO and RO, as seen in

Figure 1:

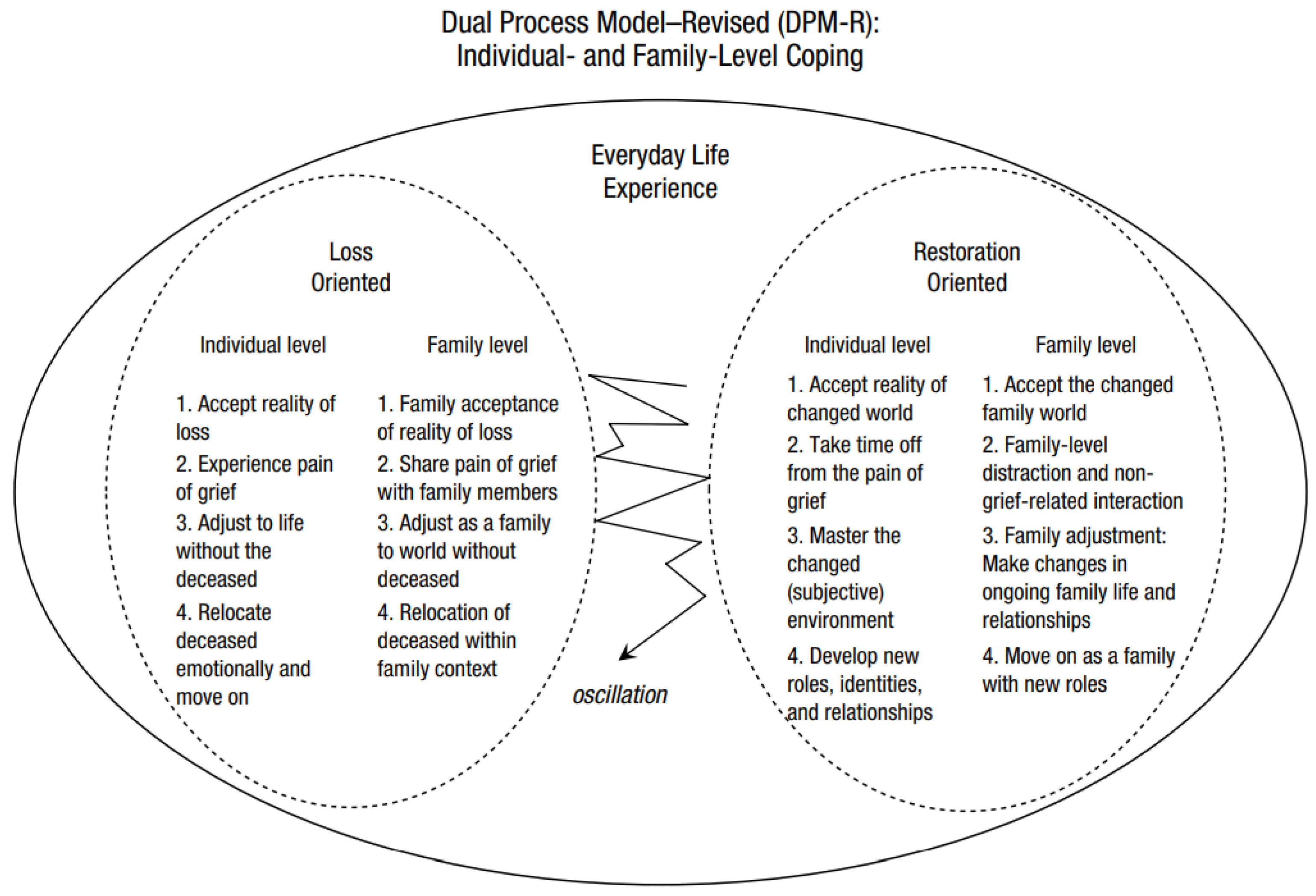

In later work, Stroebe and Schut explicitly integrated Worden’s famous model of tasks of mourning (the latest version is Worden 2018) into the DPM. The LO category now included Worden’s literal formulations and the RO category included certain adaptations or chosen specifications of them. Furthermore, in 2015 Stroebe and Schut extended the DPM to include family-level dynamics. There can be family-level ways of coping and also specific stressors on that level. Furthermore, the different levels influence each other: individual coping affects family coping, and vice versa. The revised version, The DPM-R, is seen in

Figure 2:

The later version is important in integrating Worden’s research into the DPM, and Worden’s work itself is based on integration of many kinds of earlier research. However, the new wordings of tasks have replaces the older ones, and some of those old ones can be helpful in observing what the DPM is about. For example, in Loss-Orientation, there can be “Intrusion of grief”: something reminds the mourner of the loss and feelings of grief take over. And in Restoration-Orientation, there is “denial/avoidance of grief” and “distraction from grief” (Stroebe and Schut 1999).

The DPM was influential in bringing more attention to the need to distract oneself, “to take time off from the pain of grief”.

3 Some scholars have further conceptualized this as an orientation of its own (Pihkala 2022a; Ratcliffe 2022, 209–10).

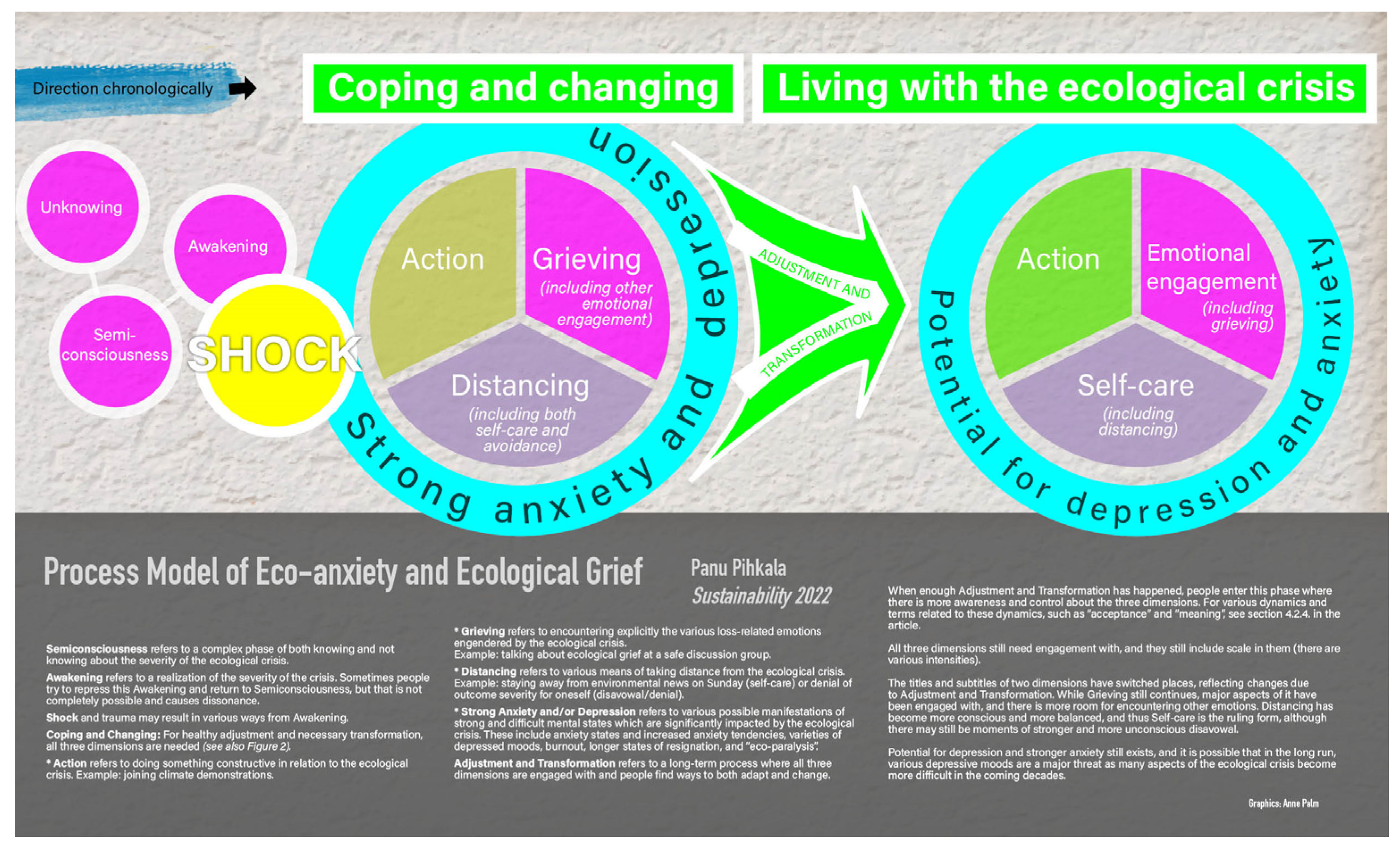

4 Of course, this need for distancing is fundamentally a consequence of the loss, and thus it is understandable that Stroebe and Schut place it under the category of “what needs to be engaged with”; but as an emphasis and orientation, it is quite different from e.g., actively learning new skills. Pihkala’s Process Model of Eco-anxiety and Grief (2022) reflects this by building on a three-fold dynamic: Action, Grieving, and Distancing. The more nuanced relationship between these models will be discussed later.

Overall, an important question for further research and discussion is the level of nuance and granularity in naming the tasks and contents of LO and RO. For example, there is a lot of possible content in a category such as “Developing new roles, identities, and relationships”. This will be discussed more in the later parts of this article.

The DPM has continued to evoke much interest, and both its creators and other scholars have developed or applied it further. Stroebe and Schut (2010) evaluate the first ten years of research around the framework, and Fiore (2021) provides a wider review. In addition to the 2015 revisions where family dynamics were added (Stroebe and Schut 2015), Stroebe and Schut published a paper in 2016 which focuses on the issue of overload and its relationship with the framework (Stroebe and Schut 2016). Larsen and colleagues (2024) offer an application of the DPM as a process visualization where the acute and more intense phase of grief is separated from later developments.

3. Previous Research About Extending the DPM into Societal Issues and Ecological Grief

Since the 2010s, a couple of scholars have probed the applicability of the DPM for societal-level mourning. Robben (2014) studied sociocultural mourning about government atrocities in Chile and Argentina, using the DPM as an analytical tool. He is clear about the challenges of applying the model into such wide dynamics, but points out that the separation between LO and RO tasks can be very helpful in analyzing societal responses to national losses. He found differences between “politics of oscillation” in these two countries, with many kinds of impacts. In Argentina, LO tasks were given more attention in addition to RO procedures, while in Chile, the governmental focus was heavily on RO tasks. As a result, in Chile, the victims and their close ones felt that recognition was missing, and the generalization of memorialization felt unfair: both perpetrators and victims were put in the same category. Robben points out that both LO and RO tasks need attention, and in these kind of cases, RO tasks include the hard work for reconciliation between perpetrators and victims.

McManus, Walter and Claridge (2018) provide an important discussion of the DPM in relation to natural disasters, and since they mention climate change, their research comes very close to ecological grief. They use two cases of online memorialization as examples of various dynamics in relation to LO and RO emphases. The disasters studied happened in New Zealand in 2010-11. The authors observe differences between cases where there is mainly loss of human lives as compared to cases where the damage happens mostly to infrastructure. They note that in the first case of “’nonmaterial’ disasters”, memorialization tends to be geared towards LO tasks, while in the latter, the emphasis is on RO tasks and reconstruction after material damage. They make insightful observations about disaster responses in general, noting how governments and other institutions may take various roles in management of RO tasks. The authors recommend that LO tasks would be given more attention in disaster studies, while RO tasks would need more attention in grief and bereavement studies about community/societal responses.

The DPM has also been applied to COVID-19 pandemic: in their 2021 article, Stroebe and Schut analyze many previous studies on coping with COVID-19-related bereavement. They make a distinction between LO/RO stressors and perceived reactions to them (Stroebe and Schut 2021, esp. table one), which is highly useful and provides a model for similar analysis in relation to other subjects such as ecological grief.

The only previous in-depth applications of the DPM into ecological grief, that the author is aware of have been made by Pihkala (2022a) and Bailey and Gerrish (2024). Pihkala discusses the dynamics of the DPM and integrates many of them into his Process model of eco-anxiety and grief, where oscillation is a key feature. However, Pihkala conceptualizes “Coping and Changing” into three, not two dimensions: Action, Grieving, and Distancing. Thus, the content in RO category in the DPM is split into two and broadened. The character of eco-anxiety as related to ethical issues brings additional focus on action, namely pro-environmental behavior of various kinds.

Bailey and Gerrish (2024) make an insightful application of the DPM into ecological grief. They focus on the possibilities of social work – or ecosocial work – in addressing it. A key feature of their application is a characterization of two major aspects of ecological grief: “unprecedented” and “unacknowledged”. These are linked with LO and RO, respectively, and special characters of both aspects are discussed on the basis of earlier research and literature. The authors argue that “[t]hese two orientations can coalesce in ways that create enormous barriers to coping and therefore action” (p. 5). Since the authors have a practical focus, they rename restoration in RO as “transformation”, and oscillation as “transition”. The key idea, well supported by research, is that communities and individuals need profound transformation because of the socio-ecological crisis.

The decisions made by Bailey and Gerrish mean that they are slightly moving away from the original focus of the DPM as describing various foci of engagement. Their model, inspired by the DPM, is more of a model of transformation. The two key terms, “unprecedented” and “unacknowledged” ecological grief, are clearly elemental aspects of ecological grief, but they are not exactly the same as LO and RO: they are qualities of psychosocial phenomena which affect how LO and RO tasks are encountered (or not encountered). Thus, in the following, the many insights provided by Bailey and Gerrish are drawn from, but the focus will be on a slightly more traditional application of the DPM in the sense of various coping tasks and dynamics. For some reason, Bailey and Gerrish do not refer to the revised version, the DPM-R, and the naming of the LO and RO tasks in that version will be used in the following analysis.

The main connotation of ecological grief for Bailey and Gerrish is its global form, and in this sense it is argued to be ”unprecedented”. They distill six major aspects of this kind of ecological grief (see their figure two): existential scale; the fact that environmental loss could have been prevented (for this ‘preventability’, see also Pihkala 2024e); “culpability”, meaning the prominence of guilt dynamics; the commonality of disenfranchised grief in relation to ecological grief; possible elements of ambiguous loss; and dimensions of anticipatory loss (pp. 6-8). Thus, these are attributes/features/dynamics which affect engagement with loss, but they are operate on a different level compared to the wordings of LO tasks by Stroebe and Schut.

Similarly, Bailey and Gerrish distill six major aspects related to “unacknowledged grief”. These are types of losses which help to understand why it is so difficult for many people to engage with the topic: loss of a way of life; of identity, of power and privilege; of predictability and certainty; of meaning and purpose; and of cultural narratives (pp. 8-10). Their summarizing figure five (p. 14) links the content together and names various tasks for collectives, such as “grief support” (LO task) and “create spaces of resistance” (RO task). However, they mostly make the RO side of the figure – now called Transformation – into an outcome variable: “Transition” is needed from the loss side to the restoration side. Thus, their insightful schema operates differently than the original DPM, and has a strong ethical dimension.

5 It points to large-scale RO tasks in the sense of societal transformation of industrial societies. These are kind of extended RO tasks: not just something which needs first to be done because there have been losses, but also deeper efforts to change societal structures so that fewer socio-ecological losses would be generated int the future. This is in line with in-depth theorizing on the topic (e.g., Head 2016; Verlie 2022). However, their powerful application could be clearer about the continuing need to engage with losses and LO tasks even in the midst of the desired transformation: there will be need for oscillation, too, in the midst of nonfinite losses (Pihkala 2024e; see also Johnson 2023; Boyd 2023; Schmidt 2023).

4. Dynamics of Ecological Grief Which Shape the New Application of the DPM

The following are major dynamics of ecological grief which affect the new application of the DPM in this article. They are selected and categorized from earlier scholarship on ecological grief and sociocultural mourning.

4.1. Local and Global Ecological Grief

Since there are many kinds of manifestations of ecological loss and grief, it seems important that the applications of the DPM would include engagement with them. Sometimes ecological grief is more explicitly born out of local changes, but often these have regional and global dimensions (e.g., Brugger et al. 2013; Cunsolo Willox et al. 2013). Mourning local ecological loss is different from mourning global ecological loss, since local losses have more particularity (Pihkala 2024e; see also the discussions around solastalgia in Galway et al. 2019).

However, it is important to note that the local and the global dimensions of ecological loss and grief can resonate strongly in people’s lifeworlds. There are many possible dynamics here. For some people, local environmental damage functions as an awakening into wider environmental problems, loss, and sorrow (Chawla 1998). For others, it is the other way around: they learn about universal dynamics of environmental problems and then they are able to see their local manifestations, which cause sorrow (e.g., Ray 2018). Sometimes people have to engage in overlapping processes of local ecological grief and global ecological grief: they are trying to deal with local loss and with a growing awareness of global ecological loss (Cunsolo and Ellis 2018; see also the discussions of ‘anticipatory solastalgia’, e.g., Stanley 2023). That can lead to various results: sometimes people become more aware and engaged, and sometimes people distance themselves. For example, research among climate disaster survivors shows that people may not want to think about the global dimension, or feel unable to do with the coping resources they have (Ogunbode et al. 2019; see also Marshall 2015).

4.2. Various Levels: Individual, Family, Peer Group, Community, Society

In the DPM-R, Stroebe and Schut extended the model to family-level and pointed out that individual and family dynamics of grieving and coping impact each other. It is possible, and indeed important, to analyze ecological grief on both of these levels, and to explore how they interact (Cooke et al. 2024). However, ecological grief is very relevant also for the wider levels of peer groups, communities, and societies, and this article extends the DPM into those levels, too.

All the aforementioned levels may interact with each other, and usually they do so, especially from the top down (Crandon et al. 2022). Societal dynamics of grieving affect community dynamics (Benham and Hoerst 2024). These both affect family and peer group dynamics, which may naturally have flavors of their own, too. And all these affect individual dynamics of grieving. Individuals may be able to influence the wider dynamics, and this is most evident for family and peer group level. Community-level innovation happens relatively often, too, such as in the case of ecological grief rituals spearheaded by a few committed individuals (e.g., J. L. Adams 2020). Society-level or even regional influencing is more challenging, but by no means impossible (Holthaus 2023).

In the DPM-R, Stroebe and Schut (2015) spend considerable time on the issue of differences among family members in grieving. They also refer to temporality: even while members grieve the same thing, they may differ in when they need to grieve more intensively or when they wish to be more socially open to joint mourning. This “desynchronization” (p. 877) provides a practical task and challenge, even more so on a community level.

At least two consequences emerge for ecological mourning. First, there should be times and places for more intense and open ecological mourning, because this is important both in relation to mourners and ethically as an act of witness to what has been lost (Cunsolo and Landman 2017). Second, those people who feel more intense ecological grief should accept that both family members and community members may have different ways of grieving. However, this is different from giving a license to bypassing ecological grief altogether.

4.3. Grief and Grievance

By definition, ecological grief is about human-caused damage to ecosystems (Cunsolo and Ellis 2018; J. T. Barnett 2022).

6 There are major differences in cases here: sometimes environmental damage is the result of very direct human action, and sometimes a more ambient or indirect consequence of for example carbon emissions. Ecological grief is thus bound up with questions about culpability and responsibility, which lead to discussions of guilt, blame, injustice, and justice. This has been noted by a great number of scholars of ecological grief (e.g., Menning 2017; Jensen 2019; Bailey and Gerrish 2024).

A simple way to express this is that grief and grievance are interconnected in ecological grief. It is interesting that research traditions about each term are quite disconnected from the other term, but recent proposals have been made to bring these closer to each other (Ranjan 2024; for another context, people of color, see Wilson and O’Connor 2022). Grievances evoke anger in many forms, including empathic anger and moral outrage (for discussions, see Batson et al. 2007; Kauppinen 2018), and this major theme is related to discussions about grief and political action. Grief and anger can channel into determined political action, and this aspect of ecological grief has been emphasized by many scholars (e.g., Kretz 2017; see further Bergman 2023).

In their application of the DPM into societal matters, this time disasters, McManus and colleagues (2018) point out, following Holst-Warhaft, that “from ancient Greece to the present day, grief’s potential to mobilize anger has troubled those with established power who therefore attempt to suppress the pain of grief” (p. 8). They connect this with the policies of authorities, and note that “Focusing on restoration rather than loss or trauma may serve their interests well” (p. 8). Emphases between LO and RO tasks may have conscious or unconscious political purposes, and the dynamics of anger and guilt are prominent here (for discussions of various dynamics, see Pihkala 2024f; Gregersen, Andersen, and Tvinnereim 2023).

The tasks of the DPM in relation to ecological grief are thus intimately connected with discussions about justice and responsibility, including guilt and culpability. Affects related to anger and guilt can be strongly present, and these are also generally common emotions in grief processes (Worden 2018; Li et al. 2014). There’s many ways in which perceived injustices and grievances can hinder engagement with both LO and RO tasks, including oscillation between them, and this has implications for all levels from individual to societal.

4.4. Social Difficulties, Anxiety, and Denial

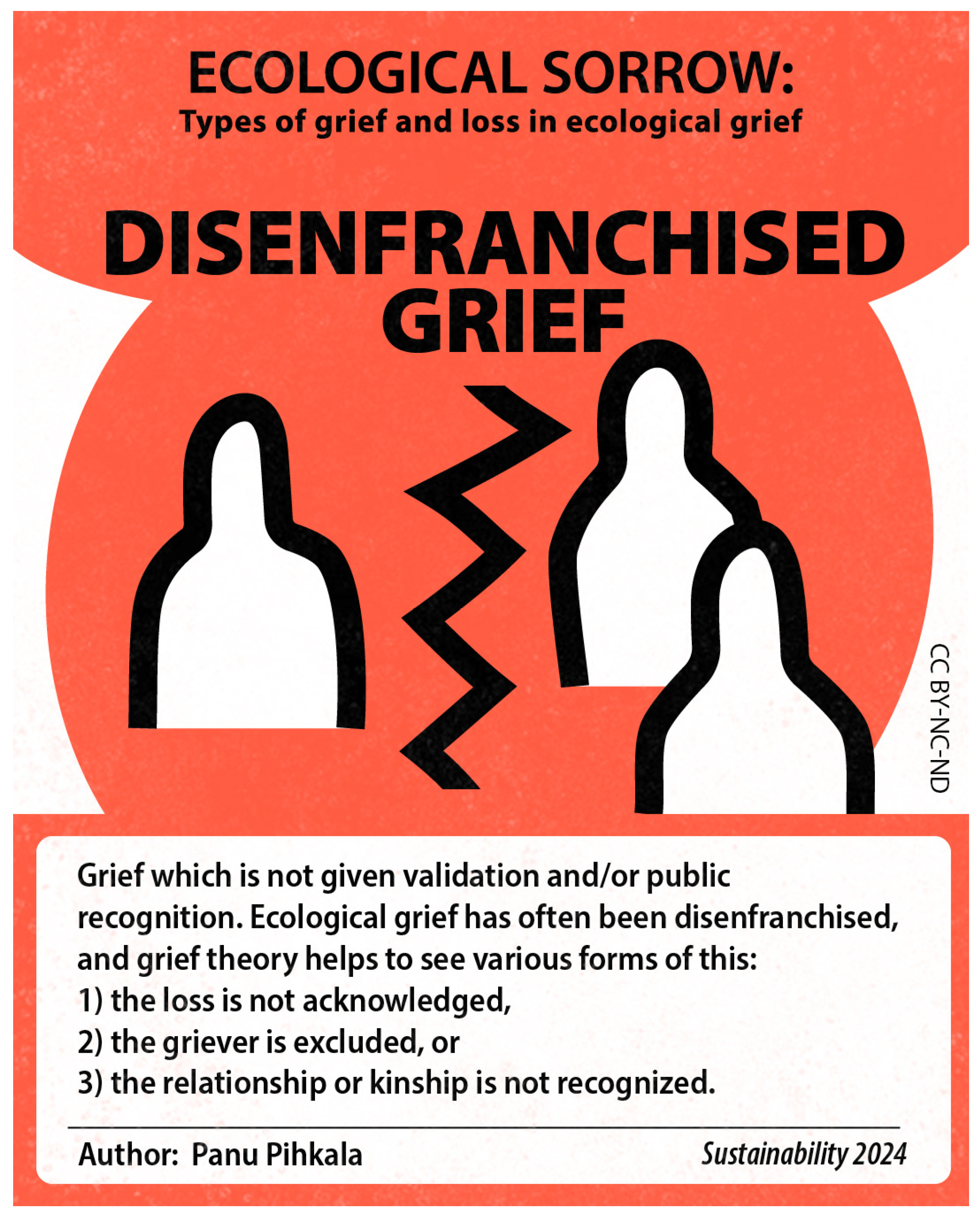

There are many reasons why ecological grief can be difficult. For collective-level applications of the DPM, social contradictions and difficulties around ecological grief seem particularly impactful (for discussions, see Neckel and Hasenfratz 2021; Varutti 2023). Ecological grief has often been disenfranchised grief (Kevorkian 2004; Cunsolo and Ellis 2018). Pihkala (2024e) provides a discussion of various dynamics in this, as seen in

Figure 3.

The various reasons why ecological grief often is socially contradictory are deep and manifold, and these are intimately connected with eco-anxiety / eco-distress (for these concepts, see Pihkala 2020; 2024c). Many scholars have noted the links between ecological grief and anxiety (for a review, see Ojala et al. 2021). Local ecological changes and losses may also evoke anxiety and distress, but these emotions – or mental states, depending on their character – are very prominent in relation to global ecological losses and threats.

The global ecological crisis often evokes both threat-related emotions such as anxiety, fear, and worry, and loss-related emotions, such as sadness and grief (Pihkala 2022b; Marczak et al. 2023). People’s reactions to this reality can be widely different. Some people get activated in environmental matters (Hoggett and Randall 2018; Kurth and Pihkala 2022), but as Bailey & Gerrish (2024) emphasize, there is often denial and distancing of the losses and threats (e.g., Weintrobe 2013b; Stoknes 2015). It is a tricky question whether people who practice strong denial already feel, in a suppressed or repressed form, “a deep grief”, as Bailey and Gerrish argue (2024), or whether they are only approaching the acceptance of the loss and resist grief (for perspectives, see Lertzman 2015; Head 2016; Haltinner and Sarathchandra 2018). Be that as it may, the evident result is that there are conflicting reactions and behaviors in societies, communities, and often also in families, and this makes ecological grief (and anxiety) much more difficult to cope with.

Thus, social contradictions and tensions affect all levels of ecological grief, from individual to societal, and they can impact both LO and RO dynamics, as well as oscillation. The DPM allows pinpointing various these impacts by exploring what exactly they hinder in a given situation. For example, it may be that a community socially supports RO tasks, but not LO tasks. In another case, it may be that there has initially been LO focus, but there is then social pressure for closure, and there is social discouragement of oscillation into LO tasks even while that would still be needed.

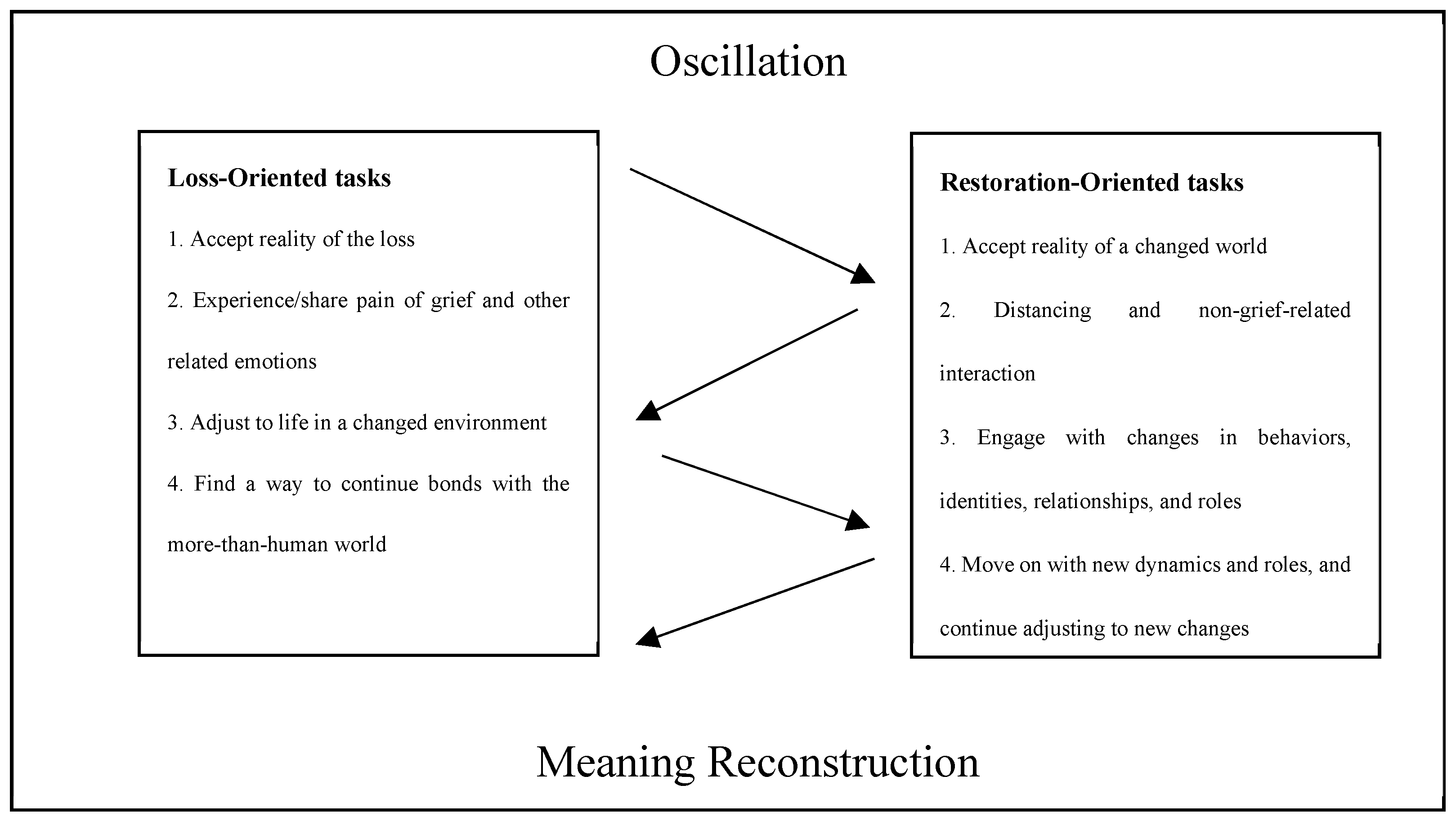

5. The DPM-EcoSocial

The following

Figure 4 shows the new application of the DPM-R into ecological grief and collective levels. The name of the new version is DPM-EcoSocial, and there are several reasons for this selection. The name emphasizes the close connections between ecological and social factors, which is discussed in eco-social philosophy (e.g., Pulkki, Varpanen, and Mullen 2021) and in socio-ecological modelling of eco-emotion dynamics (e.g., Crandon et al. 2022). The name also reminds of how powerful social dynamics are for ecological grief. The DPM-EcoSocial can be applied to both local and ecological grief (section 4.1. above), as well as for various levels from individual to community and society (section 4.2. above).

The content of the tasks will be discussed in the following sections, but their naming and certain modifications from the DPM-R are elaborated here. As can be seen in the Figure, the wordings of the tasks have been kept almost the same, but naturally the context of ecological grief has causes the need to make certain changes. In selecting terms, also other grief theories were kept in mind, especially Worden’s evolving formulations; the DPM-R used Worden’s previous wordings.

Task 3 in both LO and RO categories has been renamed, because the original formulation referred to “the deceased” (person). The new wording of the LO task follows Worden’s new formulation, but interprets it ecologically: Adjust to life in a changed environment. Environment refers here to physical and possibly also social environment. The original individual RO task spoke of mastery: “Master the changed (subjective) environment”. Mastery is problematic as a goal, since human efforts at mastery of “nature” have caused massive environmental problems, and because environments will keep on changing (for critique of mastery in the context of ambiguous loss, see Boss, Roos, and Harris 2011). The original family-level task was characterized as adjustment and making changes in ongoing (family) life and relationships. The new formulation in the DPM-EcoSocial is “Engage with changes in behaviors, relationships, and roles”: this refers both to efficacy (think of “mastery” in the original), adjustment, and relationality.

Task 4 in both LO and RO has also been modified. The original wording of the DPM-R in LO, “Relocate deceased emotionally and move on”, was based on Worden’s effort to integrate the idea of continuing bonds and the idea of being able to move on in life (Worden 2009). This “move on”-aspect also reminds of the classic idea in grief research about “reinvesting emotional energy”, as Worden delineated the task in the 1980s (Worden 1982). In 2009, Worden modified the wording to bring out the connection to continuing bonds even more explicitly: “To find an enduring connection with the deceased in the midst of embarking on a new life” (Worden 2009). In 2018, this was changed into “To find a way to remember the deceased while embarking on the rest of one’s journey through life” (Worden 2018).

The individual-level RO task 4 in the DPM-R is “Develop new roles, identities, and relationships”, and the family-level task is “Move on as family with new roles”. Thus, key ideas are about adjusting, moving on, and new roles and relationships. The new formulations in the DPM-EcoSocial are the following: in LO, “Find a way to continue bonds with the more-than-human world”, and in RO, “Move on with new dynamics and roles, and continue adjusting to new changes”. The latter part of continuing to adjust pays tribute to the character of ongoing, sometimes nonfinite ecological losses. It is notable that one of the main developers of the continuing bonds approach, Klass, emphasizes the social and cultural dynamics in it (Klass 2023), and these are a major part of the DPM-EcoSocial.

The DPM-EcoSocial can easily be used also in relation to other community-level and society-level losses: only the fourth LO task needs to be renamed as ”Find a way to integrate what has been lost into the fabric of life”.

The following discussion describes the tasks in the DPM-EcoSocial and thus discusses some major aspects of coping with LO and RO tasks amidst ecological grief. It is to be noted that there could be also other ways of naming and describing important dynamics and tasks, such as the wordings in the original DPM.

6. Loss-Oriented Tasks

6.1. Accept Reality of the Loss

As was discussed above in connection to the work of Bailey and Gerrish (2024), this is a major challenge in relation to global ecological grief. People need lots of containment and psychosocial resources to take in the potentially traumatic information (e.g., Lewis, Haase, and Trope 2020; Doherty et al. 2024). Even gradual advances in this acceptance can be argued to be important; full acknowledgement of the severity of the ecological crisis is psychologically very tough (for books about experiences of this, see e.g., Jamail 2019; Sherrell 2021; Boyd 2023).

In relation to local or regional ecological losses, accepting them can be psychosocially easier because they are more particular and less threatening than global demise, but there are often various views of what counts as a loss and how significant those losses are (e.g., J. Barnett et al. 2016; van der Linden 2017). Furthermore, there can be so severe local losses that it is difficult to accept their finality (e.g., Amoak et al. 2023).

6.2. Experience/share Pain of Grief and Other Related Emotions

This task refers both to the need to actually feel one’s feelings and to share them with trusted others. Families and other in-groups can be highly important in this, but naturally this is challenging if people have very different reactions to ecological issues and grief. People long not only for emotional support, but for validation and recognition, and too often ecological mourners have felt isolated (e.g., Kretz 2017). The discussion by Cooke and colleagues about what they call “ecological grief literacy” (2024) includes recommendations for constructive engagement with ecological grief also on organizational and family levels.

It is well-known that many emotions often take place in grief processes, such as anger, fear, despair, and guilt (e.g., Worden 2018). This is also evident in relation to ecological grief and anxiety: the ecological crisis evokes many kinds of emotions in people (e.g., Hickman et al. 2021; Albrecht 2019; Pihkala 2022b). These need to be felt and engaged with, and for example issues around guilt can complicate grieving if they are not faced (e.g., O. Jones, Rigby, and Williams 2020; Prade-Weiss 2021). Peer groups and facilitated sessions can be a highly useful means for this (Hamilton 2020), both in relation to local and global ecological grief. Examples include Climate Cafés (Broad 2024), Good Grief Network groups (Schmidt 2023), Living with Climate Change groups (Randall, Nestor, and Fernandez-Catherall 2023), and various groups facilitated after severe local environmental damage. Some methods include focus on different eco-emotions in different thematic sessions (e.g., Macy and Brown 2014), which can be seen as important LO work.

6.3. Adjust to Life in a Changed Environment

This task emphasizes emotional adjustment; other kind of adjustment is more a RO task, but it is evident that many practical actions here can serve both LO and RO tasks. In the DPM-R, this task means learning to cope with situations where people are reminded that the deceased is missing. In relation to ecological grief, there can be various kinds of triggers which remind of the loss and grief, depending on what is mourned and whether that includes local and/or global aspects. Mourners face the task of learning somehow to deal with those triggers and the emotions they evoke.

Relevant strands of research include coping theory and emotion regulation theory (for an overview, see Ibrahim 2024). People can use, and learn to use, various methods, such as the following. They can practice situation selection: trying to either avoid or be in situations where certain emotions are evoked (Gross and Ford 2024). They can use cognitive reframing and/or somatic methods: for example, when difficult emotions arise, such as strong sadness, they can use cognition to tell themselves that they are able to withstand these emotions and that the strongest emotions will pass, and/or they can use deep breathing to calm themselves down (e.g., Doherty et al. 2024; Wright 2024). They can make spaces for emotions to flow, such as doing a grief ritual when sadness arises and letting tears run (e.g., Johnson 2018; Sapara Barton 2024). Many psychologists and experts-by-experience have offered various tips for emotion regulation and coping in relation to ecological grief and distress (e.g., Doppelt 2016; Davenport 2017; Weber 2020; Macy and Johnstone 2022).

6.4. Find a Way to Continue Bonds with the More-Than-Human World

Grief theorists emphasize that people need to find ways to integrate the loss into their lives. Sometimes this manifests as continuing emotional bonds with what has been lost (Klass 2023). This task is closely connected with acceptance and adjustment, in the sense of reaching a state where the painful feelings related to the loss do not take control – at least as easily as before – and perhaps some of their edge is gone (e.g., Kübler-Ross and Kessler 2005; Worden 2018). There may be elements of moving on in life and rejuvenated life energy, although nonfinite losses affect these dynamics: the losses may continue to manifest, and there is then cyclicity in the processes (Roos 2018).

In the DPM, the ultimate goal of adjustment is connected to both LO and RO tasks. In the LO part, this task is fundamentally about emotions and continuing bonds: a longer name for the task would be “Find a way to continue bonds with the more-than-human world while embarking on the rest of one’s journey through life”.

Continuing bonds are often manifested via memory objects, memorial places, rituals, and other spiritual practices. In relation to lost humans and more-than-human creatures such as companion animals, people often use memorial photos at home and visit memorial sites outdoors. In relation to various kinds of ecological grief, the following are examples of different ways to practice remembrance and continuing bonds:

Annual remembrance days, such as Remembrance Day for Lost Species on 30th November (de Massol de Rebetz 2020; Wray 2022, 203–15) and annual days where former climate disasters would be remembered

Public and stable memorials, such as the Monument to the Passenger Pigeon (J. T. Barnett 2022), monument to the Ok glacier in Iceland (Árnason and Hafsteinsson 2020), or plaques remembering intensive weather events and catastrophes (Hall 2017)

Movable/portable memorials, such as thematic Altars of Extinction (Gomes 2009) or art projects which engage with ecological grief (e.g., Barr 2017)

Public rituals (Mihai and Thaler 2023; Pike 2017)

More private, sometimes spontaneous rituals and/or memorial places (e.g., Johnson 2017)

These kind of activities are not only psychologically important, but also ethical practices of bearing witness and remembering (e.g., Cunsolo 2017; J. T. Barnett 2022). Emerging literature and scholarship provides insights for this. Social scientists Mihai and Thaler (2023) point out that various practical and ethical aspects need attention when organizing forms of public ecological mourning, and they provide insightful guidelines for what they call environmental commemoration. Religious scholar Menning (2017) analyzes elements in certain traditional mourning practices by various religious communities and provides fascinating reflections on how these could be applied for ecological grief. Ecological theologians such as Hessel-Robinson and Malcolm (Hessel-Robinson 2012; Malcolm 2020a) have applied the ancient practice of lament into ecological mourning.

This is a good place to remember that the tasks can be overlapping, and for example a public ritual of ecological mourning can advance all the four LO tasks named above: it can help bystanders to move towards accepting the reality of the loss, it offers an opportunity to share and experience pain of ecological grief, it provides methods of emotional engagement and emotion regulation, and it is connected to the tasks of continuing bonds, witnessing, and moving on in life.

7. Restoration-Oriented Tasks

As mentioned above, Restoration-Oriented tasks are things that need attention because of the loss has happened. These may be stressors or ways to deal with stress; Stroebe and Schut (2016, p. 98) call them “perceived concerns/preoccupations”. This category can easily become very wide-ranging in the case of ecological grief, because that is so holistic (an example is Bailey & Gerrish 2024). Especially global ecological grief is related to a whole changing world, but also local and regional sources of ecological grief can give rise to profound needs for change. For example, massive droughts can impact whole lifeworlds of communities, such as the farmers studied in a research article about Ghana (Amoak et al. 2023). As Stroebe and Schut (2016, p. 99) formulate, “Many aspects of one’s daily life may need to be rethought and planned afresh.”

7.1. Accept Reality of a Changed World

When Stroebe and Schut divided Worden’s first task into two parts, a LO one and a RO one, this latter one gained an emphasis on how the world is changed because of the loss. Depending on what kind of ecological loss one focuses on, this task can become complex. Global ecological loss and severe local ecological loss change the world in profound ways, both physically and socially.

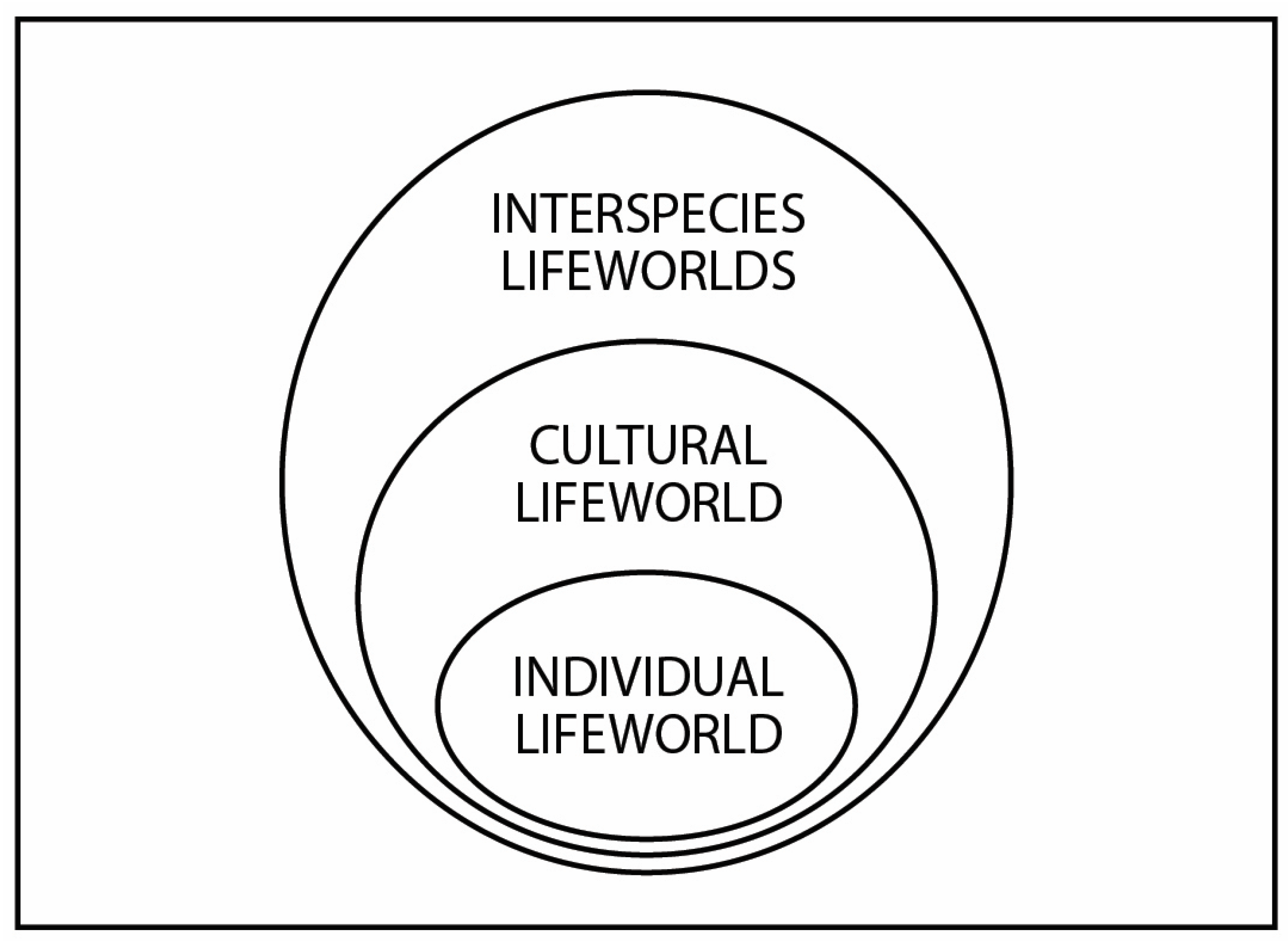

A distinction between world and lifeworld can sometimes bring clarity to focus. Lifeworlds are lived realities, which orient around important things and relations in a life (see e.g., Fairtlough 1991). Environmental change and damage can destroy whole lifeworlds, such as those of farmers, fishers, or seal-hunters; Pihkala (2024) uses the term “lifeworld loss” to describe this. The following

Figure 5 depicts multilayered lifeworlds, and family lifeworlds could be named there between cultural and individual.

Originally, key concepts in relation to RO in the DPM included “doing new things” and “attending to life changes” (Stroebe and Schut 1999). As Stroebe and Schut (2015, 877) write: “New tasks and secondary stressors (changes) due to the loss - - add to coping difficulties; undertaking them promotes adjustment and acceptance of the changed world.” Now that the DPM-R uses wordings from Worden, the first and third RO tasks come very close to each other.

The wider levels of family, peer group, community, and society affect how changed (life)worlds are accepted or not accepted, and the various levels interact with each other (see

Section 4.4. above). There can also be additional stressors on particular levels. What Stroebe and Schut (2015, 877) write in relation to family dynamics can be applied to ecological grief and the even wider levels of peer groups, communities, and societies: “Additional family-level stressors resulting from the loss (conflicts, legal/financial battles, poverty) add to difficulties and lack of acceptance of the changed family world.” Social support would be essential in the difficult but elementary task of accepting how the world has changed in so many ways: ecologically, socially, culturally, and politically. The changes extend to religions and worldviews, too (e.g., Haberman 2021; Malcolm 2020b).

7.2. Distancing and Non-Grief-Related Interaction

This task is discussed in Pihkala’s Process Model of Eco-anxiety and Grief (2022) as “Distancing (including both self-care and avoidance)”. Stroebe and Schut use the wordings “distraction”, “take time of the pain of grief”, and “non-grief-related interaction”. Distancing can be argued to be wider than just distraction, even though both point to the same direction.

Especially in relation to severe losses and nonfinite losses, people need skills and opportunities of regularly distancing themselves from heavy engagement with the losses and sorrows. In relation to eco-emotions, this is often discussed by psychologists in the case of eco-anxiety/distress and the need to calm down one’s nervous system (e.g., Haase and Hudson 2024; Ibrahim 2024). The chances for distancing are naturally shaped by socio-ecological factors, and people suffering from many kinds of hardships and injustices have more challenges here. That been said, some people amidst very difficult conditions have found creative ways to practice non-grief-related interaction: for example, storytelling, dancing or singing (Uchendu and Haase 2024; Wray 2022).

The founder of Good Grief Network, LaUra Schmidt, provides an insightful discussion of taking care of oneself amidst ecological grief and crisis (Schmidt 2023, 183–204). She notes how the concept of self-care, which is sometimes criticized today because of possible individualistic associations, was emphasized in an inter-relational way by black feminist activists in the late 1960s and 1970s. Self-care, which often happens in community and is intimately tied with various relationships (also to the more-than-human), is elementary also for political and ethical purposes: it enables people to keep on fighting for a better world (see also e.g., Boyd 2023, 219; Sapara Barton 2024).

In the context of ecological grief, distancing and non-grief-related interaction need to take place in social groups as well. Sometimes this happens naturally, but conscious effort can be made to ensure this. For in-groups and communities, developing a weekly or monthly rhythm of both engaging with loss (LO tasks) and taking time off from it (RO) can be a supporting structure. Religious communities can utilize their traditions for this (Pihkala 2024f), since they often anyway invite their members to engage with suffering and sorrow, while also offering spaces for fun and celebration (for an example, see Abercrombie 1994).

7.3. Engage with Changes in Behaviors, Identities, Relationships, and Roles

As mentioned above, this task is intimately connected with the first RO task. Accepting the changed world leads to motivation to rework behaviors and relationships, which in its turn may help people to accept changes in (life)world.

In addition to the words mentioned in the heading, practices could be named as well. There is a need to learn new things and to change because of the loss. Some of these changes are direct requirements caused by the loss, and some are more indirect consequences or opportunities caused by it.

In classic cases of bereavement, mourners may need to make changes to living arrangements now that a close one is gone, and they may have to learn new skills and practice new roles. For example, the deceased may have taken care of certain family duties, and now someone else needs to do that, which may require learning. Sometimes this dynamic takes place also in ecological loss: for example, loss of pollinators has already pushed people to try to pollinate plants in some regions of the world (Darnaud 2016).

Ecological losses can be diverse in character, and various levels of them cause different needs. Global ecological loss causes a deep need for adjustment and transformation (e.g., Pihkala 2022a; Bailey and Gerrish 2024). Local or regional ecological losses may cause holistic needs for change, too, such as in the case of lost possibilities for agriculture (Amoak et al. 2023), but there are also losses which cause rapid needs only for a portion of local people or which may even pass unnoticed by many. As a result, it is often only a part of the people of a larger community who engage in transformative change, and the development of more ethical and sustainable community dynamics is hindered because of differences in reactions.

There are numerous possible changes that are needed because of ecological losses and the resulting grief. Bailey and Gerrish (2024) name many of these, and some authors, such as Andreotti and colleagues (De Oliveira Andreotti et al. 2023; Stein et al. 2022), take the depth of required changes even further. Some differences between these changes can be discerned by differentiating between more traditional ideas of resilience and deeper conceptualizations of “transformational resilience” (Doppelt 2016; 2023) or “transilience” (Lozano Nasi, Jans, and Steg 2023; 2024). To begin with, ecological losses may require changes so that daily life can continue to function at all. For example, significant sources of food/water or income may be lost, and now work is needed in trying to reorganize the fulfillment of those needs. This would be resilience: being able to return to the previous state of functioning. However, that is not always easy to do in the case of profound environmental change and damage, such as droughts and other dire impacts of climate change (e.g., Boafo and Yeboah 2024).

Transformational resilience, or transilience, points to the need to grow beyond the original state of things. This can, and many ethicists say should, take many forms. There is physical transformational resilience in the sense of reworking the material lifeways of communities and societies. There is ethical transilience in the sense of developing new, more sustainable values, which guide actions. And there is psychological transilience: increased flexibility and capability in coping with hardship (for discussions on various aspects of this, see Doppelt 2016; Pihkala 2022a; Verlie 2022).

Engaging with this RO task in the case of ecological loss and grief is thus a profound ethical and practical need, with strong psychological implications. Communities and societies, I argue together with many other thinkers, should not be satisfied with surface-level restoration, but should aim at the same time for deeper transformation and transilience (Moser 2019; Walter 2024; see also the discussion around Bendell 2023). The DPM supports the idea that this deeper aim is probably not possible to reach without enough attention also to LO tasks. This is in line with Robben’s (2014) arguments about LO and RO tasks in national mourning and reconciliation, and also with the points made by McManus et al. (2018) about responding to natural disasters. There can be a vicious circle, here, however. Because deeper grieving is so often resisted in industrialized societies (e.g., Weller 2015; Horwitz and Wakefield 2007), there is a tendency to avoid LO tasks, and that then also restricts deeper engagement with RO tasks in the sense of more profound transformation.

7.4. Move on with New Dynamics and Roles, and Continue Adjusting to New Changes

This task refers both to a continuation of the third task and the element of moving on in life (see

Section 6.4. above). In practice, this is intimately connected with growth via grief and crises. That is often called post-traumatic growth (Tedeschi et al. 2018), with some scholars suggesting that adversarial growth would be a more neutral common name (Blackie et al. 2023). People will need to continue transforming and growing amidst various socio-ecological crises. Scholars have started to explore the dynamics of adversarial/post-traumatic growth in relation to ecological issues (Doppelt 2016; Pihkala 2024a; Kamenetz 2023).

8. Discussion: Dynamics of the DPM and Ecological Grief

In this section, certain important dynamics of DPM and ecological grief are discussed further.

8.1. Oscillation

As mentioned, the creators of the DPM, Stroebe and Schut, point out that oscillation not only happens in grief processes, but that it should happen. Both kinds of tasks, LO and RO, need engagement with, and it is problematic if people get overly stuck with only one of these orientations.

In ecological grief, the need for oscillation is strengthened by many factors, such as the following:

Ongoing character of ecological losses, especially in global ecological grief. Oscillation is needed amidst nonfinite loss and chronic sorrow.

The common social disputes around ecological grief. Ecological mourners often need to regulate their responses because of outer, social needs.

The existential weight of the global ecological crisis and the grief it causes. So much is being destroyed that there will be “intrusion of grief” (Stroebe and Schut 1999) and a need to oscillate to LO tasks. On the other side, there will be a need a need to find relief from the pain of grief via RO tasks and distancing.

The importance of learning skills of oscillating more consciously has been mentioned several times above. In Pihkala’s Process Model of Eco-anxiety and Grief (2022a), oscillation is characterized to happen via three dimensions of Coping and Changing: Action, Grieving (including other emotional engagement), and Distancing (including self-care and avoidance). Furthermore, a more flexible state of being able to control oscillation more is described under the heading Living with the Ecological Crisis, where the titles and subtitles of two dimensions have switched places to describe this element of control: Emotional Engagement (including grieving), and Self-care (including avoidance).

Figure 6 shows the model.

What is not depicted visually in the model is the potential cyclicity in processes of more acute grief and distress. There may happen events, both external and internal, which cause a need for people to engage again with Grieving and Distancing more intensively – and perhaps less consciously. New tasks of adjustment and transformation may present themselves, sometimes along with new opportunities for growth (if people are lucky). By using terms from the DPM, this could be described as more intense engagement with LO tasks and new kinds of RO tasks.

7

8.2. Overload

In a 2016 article, Stroebe & Schut integrated the concept of overload to the DPM: “having more to cope with than one feels one can manage” (Stroebe and Schut 2016, 97). The structure of the DPM allows them to think of various options for this overload:

Overload (mainly) because of too many LO stressors

Overload (mainly) because of too many RO stressors

Overload because of too many both LO and RO stressors at a given time

Overload (mainly) because of too many non-grief-related stressors in life (Stroebe and Schut 2016, 101-102)

Stroebe and Schut point out that mere oscillation may not be enough in situations of overload, but instead the number and weight of stressors needs to be limited (2016, 102-103). They also note the problems caused if there is significant trauma included: “Traumatic bereavements may cause difficulties in alternating smoothly (less balanced or controlled or coherent) between the LOs and ROs (and in taking time off).” (Stroebe and Schut 2016, 100).

Sometimes overload can result from the need to make difficult decisions about what stressor(s) to deal with: “bereaved persons … may actually experience a sense of conflict between dealing with stressors (i.e., the feeling that one should be dealing with something else” (Stroebe and Schut 2016, 101).

In relation to ecological grief, all this is significant and can help to make sense of difficulties in coping with it. Using the DPM, it is possible to analyze what kind of dynamics cause overload. For example, sometimes there may simply be too many ecological losses: simultaneous, cumulative, and/or cascading losses (Cunsolo et al. 2020). And in other cases, the demands for RO can be so immense that people feel overwhelmed. However, often the overload in ecological grief and anxiety may result simply from having too many stressors in life in general.

The felt conflict between stressors, the feeling that perhaps one should be dealing with something else, seems an important dynamic in ecological grief and anxiety. Anxiety itself is strengthened by feelings of overwhelm or having to choose between many options amidst stress (see already Epstein 1972; later Barlow 2004; LeDoux 2016; Kurth 2018). It can be a manifestation of adaptive, practical anxiety (Kurth and Pihkala 2022) to think about what exactly one should do in a given situation, but it is easy to see how that may become too intense, especially when feeling grief and in the midst of everything which needs changing in contemporary societies.

Communities and counselors could advise people to focus on one LO or RO stressor at a time, which helps to avoid overload and anxiety (Doherty et al. 2024; Ibrahim 2024). If things go well, this can bring feelings of efficacy, which then buffer against distress and feelings of helplessness.

8.3. Meaning Reconsctruction

In addition to the DPM, one of the most influential approaches in grief theory and counseling in the 2000s has been the meaning reconstruction approach by Neimeyer and colleagues (Neimeyer 2019; for its influence, see e.g., Worden 2018; D. L. Harris 2020). This integrative approach emphasizes the need for mourners to work through changes in meanings in life, perhaps after shattered assumptions or at least due to a need to “relearn the world” (Attig 2015) after grief. In practice, narrative methods are often used in this approach, helping people to tell the story of the loss, spend time on the background story which led to it, and engage in telling a forward-looking story of their life (e.g., Neimeyer 2023). There is much literature on this approach (e.g., Neimeyer 2016; 2022) and Pihkala (2024) applies the approach to ecological grief.

Stroebe and Schut have linked the DPM intimately with meaning reconstruction, but their most explicit discussion of this is already from 2001 and a bit outdated, since the meaning reconstruction approach has been developed further since that. In addition, the application of “positive” and “negative” meaning reconstruction in their article is arguably not nuanced enough for losses such as ecological losses (Stroebe and Schut 2001). Stroebe and Schut have continued to refer to the importance of the meaning reconstruction approach and to the need to combine various approaches (Stroebe and Schut 2021, 517).

The process of meaning reconstruction and re-telling of life narratives is so holistic that it is related to both LO and RO tasks. It can be framed as an overarching theme in the whole model, and this is why it is written next to the visualization in the new DPM-EcoSocial.

In practice, the materials and methods published by grief scholars and counselors who use meaning reconstruction offer many ideas for engaging with ecological grief. These methods allow for explicit LO and/or RO engagement, in addition to holistic work on changing meanings in life. A prime example of this are narrative methods. Telling the story of the loss is important for tasks 1 in both LO and RO: trying to accept the loss and the changed world it has caused. Telling the background story brings more understanding, and telling the forward-looking new story of who people are in light of the loss is closely connected with tasks 3 and 4 in both LO and RO. Some facilitators of eco-emotion engagement (e.g., Graugaard 2024) have already worked with changing narratives and their multifaceted character – e.g., including both suffering and necessary growth – and this kind of work could be more brought into more explicit discussion with meaning reconstruction approaches.

8.4. Sociopolitical Grief, Ecological Grief, and Weltschmerz

Grief researcher Harris (2025) writes how ecological grief can be one part of what she calls sociopolitical grief: grief because of unjust actions by decision-makers, possibly even linked to shattered assumptions (Janoff-Bulman 1992) about the world (see also Harris 2022). Many decision-makers have done sociopolitical choices which damage both humans and the more-than-human world. This is related to what ethicist Hogue (2024) calls structural grief: he argues that in many cases, “grief has become structural, a response to socio-cultural, ecological, and political forces in the world”.

I want to offer two observations on these matters. First, for some people, ecological grief is not only part of sociopolitical grief, but itself related to shattered or faltering assumptions about the world. Pihkala (2024) writes about this and the related needs for meaning reconstruction, and earlier psychologists such as Lifton (2017) and Nicholsen (2002) have raised attention to similar dynamics. The world of nature can be a hugely important source of safety and stability, either more in the background or also via life practices such as spending much time outdoors or practicing eco-psychology. Realizing that many ecosystems and planetary boundaries are seriously threatened can disrupt people’s “ontological security”, to use Giddens’ term (for discussions, see M. Adams 2016; Norgaard 2011). This affects the difficulty of the first LO task in DPM-EcoSocial and has implications for other tasks, too.

Second, many people feel a holistic sorrow, outrage, and often powerlessness about the unjust state of the world in general. Sources for this include structural injustices in world trade and legacies of colonialism; wars; poverty; racism; misogyny; sociopolitical troubles; and ecological losses (e.g., Sapara Barton 2024; Verlie 2024). A glance at the global news in early 2025 quickly reveals a plethora of these kind of issues. It seems not adequate to call this “world-grief” simply environmental grief or sociopolitical grief. I think that it is important to be able to name crucial aspects of this world-grief, such as ecological grief and sociopolitical grief, but it would also be important to find ways to speak of its totality. The old wording by Joanna Macy and colleagues, “pain for the world” (e.g., Macy and Brown 2014), is a descriptive one; the German word Weltschmerz could be used literally to refer to this; and indigenous writers have used several terms to describe this (e.g., Whyte 2017; Meloche 2018), to name a few examples. Bailey and Gerrish (2024) offer many guidelines for transformation which is required in relation to such holistic grief (and outrage). The DPM can be used to discern various aspects of that, but it is clear that also other wordings and models will be needed to address so wide issues.

8

8.5. Disasters, Ecological Grief, and the DPM

Stroebe and Schut (2016) note the rather common dynamic where people try to avoid LO tasks by over-focus on RO tasks and “staying busy”. In general, a culture of busyness has actually been discussed as a psychosocial defense against ecological awareness and anxiety (Weintrobe 2013a). Similarly, McManus and colleagues (2018) point out how common it is in post-disaster actions to over-focus on RO.

“Natural” disasters are a complex topic in relation to ecological grief. Many of them are currently affected by global warming and sometimes also other environmental issues (for an overview, see Hore et al. 2018). Many of them produce damage to both human and the more-than-human world, sparking ecological grief in addition to post-traumatic stress, possible bereavement, and other impacts (e.g., Ranjan 2024). But not all people feel ecological grief when disasters happen, and some are resistant to attributing natural disasters to climate change, for various reason. The politics and practicalities of attributing extreme weather events to climate change are complex, since various political purposes may be included in them. Scholars have called for an integrated understanding of both socio-political and ecological dynamics in crises: for example, it is too easy for leaders who have neglected community resilience building to just blame climate change for the damage (e.g., Lahsen and Ribot 2022).

As a result of all this, coping with ecological grief dimensions in relation to disasters is usually complicated, and anyway the various impacts of disasters often make grieving difficult. The following is a categorization of options in relation to LO and RO tasks in post-disaster activities where ecological grief would be relevant:

there is very little if any focus on LO tasks in general (see also McManus, Walter, and Claridge 2018), and this in itself means that there’s no places for ecological grief

there is some focus on LO tasks, but ecological grief is not acknowledged

both general LO tasks and ecological grief are acknowledged

Ecological mourners are burdened with additional stressors and social pressures if there is no public acknowledgement of ecological grief in relation to climate disasters (see also Ramsay and Manderson 2011).

9 Furthermore, it is ethically problematic if there is no witness of damage to the more-than-human world (e.g., J. T. Barnett 2021).

A case example is currently ongoing. As I write this, unprecedented wildfires, intensified by global warming, are raging in Los Angeles, and societal responses are indeed conflicted: scientists are writing about the connections between climate change and the fires, while the newly re-elected President of the country is not acknowledging that (McGrath 2025; Milman 2025). Engaging with LO tasks and ecological grief dimensions of the crisis are left to small groups, such as climate-aware psychologists organizing Climate Cafés. This may be a recurring issue amidst many future disasters: the need for civil society to pay attention to LO tasks and both the grief and grievance dimensions, if political leaders are not up to that. This work can combine mourning past disasters and engaging with “anticipatory disaster rituals” (van der Beek 2021).

8.6. Religious Communities and LO Tasks

Above, several dynamics related to religious communities have been mentioned. Overall, religious communities seem to have particularly important possibilities for keeping up engagement with LO tasks and thus serving the whole grieving process; as Stroebe and Schut (1999) point out, engagement with both kinds of tasks serve each other. In the lifeworlds of communities, religious communities – e.g., congregations – are often places of remembrance and gathering places amidst collective grief. Frameworks and keywords for the topic include disaster rituals (Hoondert et al. 2021), community commemoration (Eyre), consolation offered by religious communities in grief (Klass 2014), and the ethical task of witness for grief and grievance (e.g., Malcolm 2023).

This topic of religious communities and LO tasks – not to mention all the tasks of the DPM-EcoSocial – is too big to be discussed here in-depth, and most explorations must be left for future research. However, I raise up certain questions for reflection.

In relation to disasters, religious communities have sometimes produced creative ways to practice remembrance also afterwards, such as in the case of disaster rituals by Norwegian Christians (Danbolt and Stifoss-Hanssen 2017). How could these kind of practices of be developed for ecological loss and grief, and in ways which manifest “vigilant mourning” (Barnett 2021) and “resistant mourning” (Mark and Di Battista 2017)?

How could leaders of religious communities work towards community acknowledgement of the large anthropogenic ecological changes which produce ecological loss and grief? (Burton-Christie 2011) How to negotiate situations where part of the members of the community frame events as “acts of God”? (Malcolm 2020b; Pihkala 2024d)

How could religious communities support engagement with ecological guilt and shame as part of “penitent mourning” (O. Jones, Rigby, and Williams 2020; J. L. Adams 2020), and help members also direct emotional energy to moral outrage in order to work against injustices? (Pihkala 2024f; Grau 2025)

In environmental commemoration, a crucial LO task, how could religious communities practice the ethical guidelines delineated by scholars Mihai and Thaler (2023): multispecies justice, responsibility, pluralism, dynamism, anticlosure?

What kind of LO tasks and RO tasks do the religious communities themselves encounter, and how could these be engaged with constructively? For example, there may be “spiritual losses” (see also Pargament et al. 2005) such as loss of spiritually important places and relations (see also Conradie 2021); loss of community cohesion because of disputes about climate politics; and loss of some young members of the community because their “eco-spiritual grief” was not encountered (Pihkala 2024d). What kind of changed roles, identities, dynamics, and possibly beliefs are needed?

9. Concluding Words

Does the DPM adequately capture the nature of coping with loss in all its complexity? We would be the first to admit that—like the earlier models—it has limitations, and some shortcomings have been identified by others too.

(Stroebe and Schut 2016, 97)

Ecological loss and coping with it is so complex that no single model can name all the relevant dynamics. However, the DPM was found in this article to be helpful in observing many dynamics of ecological grieving. The DPM was extended to include not only individual and family levels, but also social levels such as peer group, community, and society. All these levels can interact with each other in mourning. The wordings of the DPM were applied and partly modified to the context of ecological grief, and this new application was called the DPM-EcoSocial (see

Figure 4). The collective formulation may serve other applications of the DPM into community and societal matters. The earlier application of the DPM into ecological grief by Bailey and Gerrish (2024) was discussed in nuance.

Particularities of ecological grief, which affect dynamics of grieving and coping, were discussed. The intimate connections between grief and grievance were emphasized. Social difficulties and climate denial were shown to often complicate ecological grieving.

It was pointed out that the distinction between Loss-Oriented (LO) and Restoration-Oriented (RO) tasks can help to discern special needs on various levels, from individual to community. These tasks, which in the DPM-R (family-level version) are based on grief researcher Worden’s famous model, were discussed in relation to ecological grief. Dynamics related to religious communities were given attention, and it was observed that they have special possibilities for keeping engagement with LO tasks alive in communities. There are also challenges in negotiating between different religious interpretations of ecological losses, such as climate disasters, because some religious people interpret these as “acts of God”: this can be linked with moving away from the need for structural change in societies, which would be elementary in relation to climate change.

The article also discussed another key feature of the DPM, namely oscillation between various tasks of grief, and between grieving and distancing. In this, DPM was discussed in relation to Pihkala’s Process Model of Eco-anxiety and Grief, which proposes a three-fold scheme – Action, Grieving, Distancing – instead of two. The possibility of overload, a relatively recent addition to the DPM, was analyzed in relation to ecological grief and anxiety. There is great possibility for overload in ecological grief and anxiety, due to the severity of the losses, social contradictions in environmental politics, and the difficulty to choose between various tasks.

The article situated ecological grief in the context of holistic “pain for the world” and discussed the relationship of ecological grief with grief scholar Harris’ concepts of political and sociopolitical grief. For some people, ecological grief is a major dynamic in disruptions to their sense of ontological security. The importance and challenge of meaning reconstruction and re-telling of life stories was dwelled upon, and this holistic task was named in the DPM-EcoSocial.

Limitations in the article include the consequences of a very wide topic. Despite the length of the article, it is clear that many topics need further discussion and research. There are also many intriguing opportunities for future research. It would be highly interesting to do empirical research about communities who experience ecological grief by using the DPM-EcoSocial to explore various dynamics. In relation to COVID-19, Stroebe and Schut (2021), the creators of the DPM, provided a fascinating table about various stressors – both LO and RO – and dynamics and reactions related to them, gathered from existing research. This kind of mapping of ecological grief (and anxiety) stressors, dynamics, and reactions would give more light to community engagement with ecological losses and threats. For example, it would be important to study how much attention is given to LO tasks amidst the growing number of climate disasters.

In the 21 century, humanity lives among various kinds of structural grief. Finding ways to engage both with losses and community transformation is essential, and the DPM helps to see how “non-grief-related interaction” is also very important. Communities, including religious ones, can be places for both sorrow and joy, but this requires determination to engage with changing reality and resistant mourning.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DPM |

Dual Process Model of Coping with Bereavement |

| DPM-R |

Revised, family-level model of the DPM |

| LO |

Loss-Oriented tasks, part of the DPM |

| RO |

Restoration-Oriented tasks, part of the DPM |

Notes

| 1 |

Stroebe and Schut (2010) define LO as “the bereaved person’s concentration on, appraising and processing of some aspect of the loss experience itself”, and RO as “focus on secondary stressors that are also consequences of bereavement, reflecting a struggle to reorient oneself in a changed world without the deceased person” (p. 277). |

| 2 |

Stroebe and Schut (2016, p. 99) provide a summary of what they mean with oscillation: “Oscillation is a dynamic, regulatory coping process, based on the principle, indicated earlier, that the bereaved person will at times (have to—in order to come to terms with the bereavement) confront aspects of loss (deal with LO stressors), while at other times he or she will (have to) avoid them. The same applies to restoration (RO) tasks: At times, these need to be attended to (at which times LO coping cannot take place) and this goes hand-in-hand with avoidance of RO at other times too. But one cannot cope the whole time, it is exhausting to do so a lot of the time; time off is needed, where non-bereavement-related activities are followed or when the person simply relaxes and recuperates”. |

| 3 |

In their empirical study, Larsen et al. 2024 observe that the participants found it very difficult to distance themselves from their grief, and thus they question the relevance of this dynamic. However, there seems to be misunderstanding here. “Taking time off grief” does not necessarily mean that the grievers would totally forget about the grief. But there is often an impulse, a need, a desire to move away from intense engagement with grieving (Stroebe & Schut 1999). The participants in the study by Larsen et al. actually do seem to manifest this desire, too, but they do not see all its connections with “time off from grief”. |

| 4 |

Ratcliffe (2022, p. 209) argues: “loss and restoration can at least be construed as different—although interrelated—emphases that our coping activities have at different times. But there are also times when we disengage from both, by participating in familiar or new activities in ways that do not relate to the bereavement or its implications. So, it should be added that, as well as oscillating between loss- and restoration-focused activities, we oscillate between coping per se and respite from it.” |

| 5 |

The following quote explains their rationale: ”we have adapted and developed the DPM to emphasise that coping with ecological grief requires a consideration of the following: (1) an emphasis on the importance of acknowledging and responding to the enormity of unprecedented grief (loss orientation); (2) a focus on the importance of the transition (oscillation) through the development of change processes informed by an ethics of care and that prioritise collective processes; and (3) taking action to cope with unacknowledged grief (restoration, now transformation, orientation) through prefiguring new ways of living well within our ecosystem. We have renamed this orientation from restoration to transformation in recognition that radical social change is required.” (Bailey and Gerrish 2024, p. 15, italics in original) |

| 6 |

There is a rich and ongoing philosophical discussion on ecological grief (e.g., Beran 2024; Fernandez Velasco 2024; and many articles in Beran et al. 2025). |

| 7 |

It is interesting to think about the relation between oscillation and the psychological methods around distress which build on movement between two things, such as titrating and toggling. In these methods, attention is guided to be directed to a source of resources and a source of distress, trying to increase capacity by moving between these two when distress starts to get overly intense. For applications of these kind of methods to ecological distress, see Davenport (2017); Weber (2020). |

| 8 |