Submitted:

10 February 2025

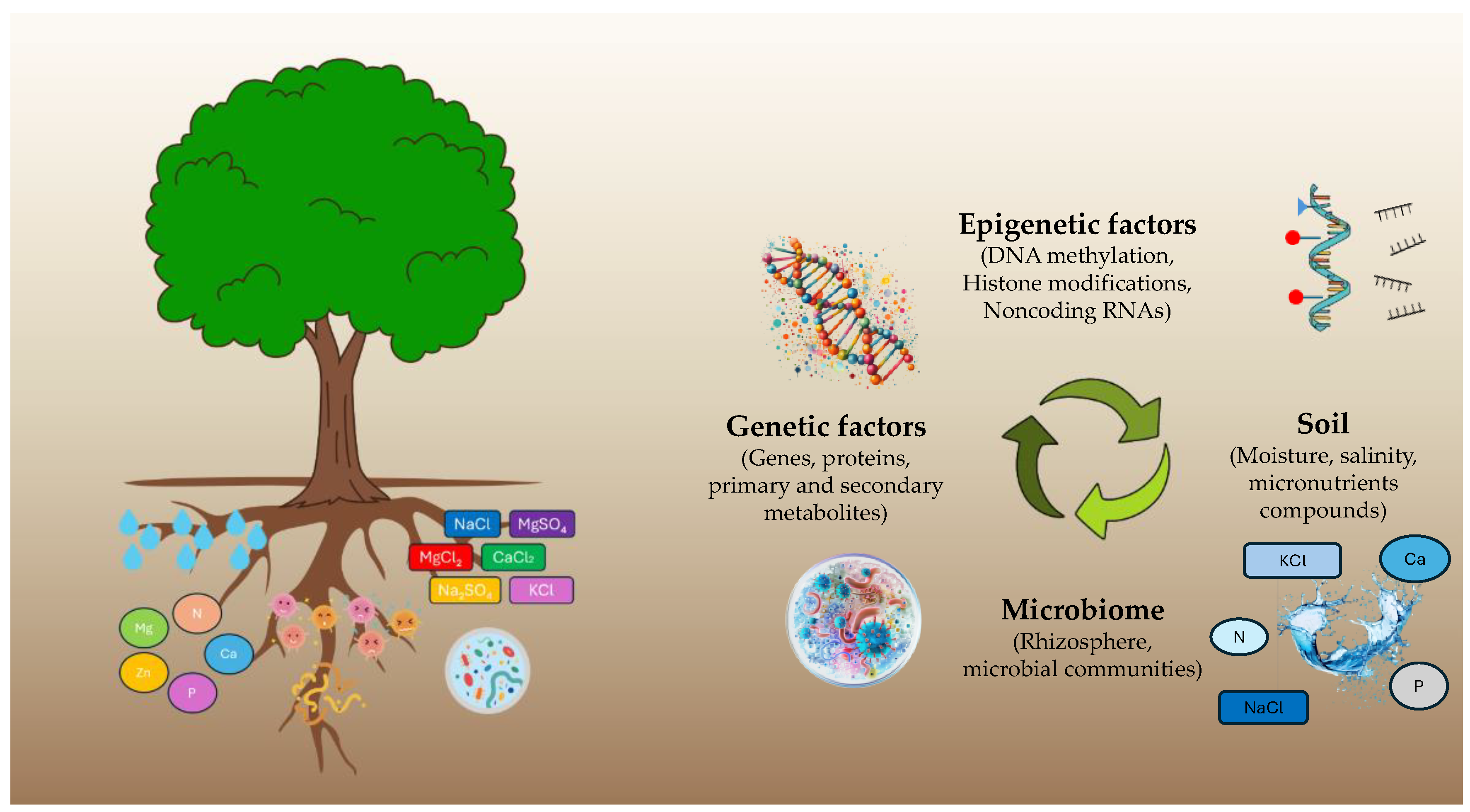

Posted:

13 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Grapevine

2.1. Climate Challenges

2.2. Genetic and Epigenetic Attributes on Abiotic Stress

| Species | Stress type | Molecular tools | Molecular response/ tolerance-associated genes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grapevine | Drought | Genome-wide identification studies (GWAS) | Candidate genes and SNPs associated with stomatal conductance and drought responsiveness e.g raffinose synthase | [49,62] |

| Transcriptomics-RNA Seq/ Quantitative PCR |

co-expression of gene networks related to signal transduction cascades, phenyl propanoid metabolism, sugar metabolizing enzymes, heat-shock protein transcription factor regulation, and histone modification factor TF families-VvAGL15, VvLBD41, and VvMYB86 Up- and down regulation of responsive miRNAs-VvmiR159, VvmiR156 Induction of miRNAs VvmiR159, VvmiR156 and anticorrelated expression TF genes, MYB1 and TPR Drought-induced VvmiR169d and VvmiR156b upregulation and VvmiR398a downregulation Activation of the module: miR156b-VvSBP8/13 |

[64] [63] [68] [70] [69] [72] |

||

| Heat | Transcriptomics-RNA seq/ Quantitative PCR | Transcription factor families -WRKYs, MYBs and NACs, Auxin and ABA signaling, Starch and sucrose metabolism Induction of heat stress-responsive miRNAs-VvmiR167 |

[65] [55] |

|

| Aluminum (Al) toxicity | Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | DNA methylation reduction / enhanced tolerance to Al | [76] | |

| Cold | Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Transcriptomics-RNA seq |

H3K27 trimethylation alterations / gene target downregulation Novel cold stress-responsive microRNAs |

[77] [75] |

|

|

Olive tree |

Drought | Transcriptomics/RNA-seq | Transmembrane transport and metal ion binding processes, abscisic acid, gibberellin, brassinosteroids, and ethylene-activated signaling |

[79] |

| Salt | Transcriptomics/RNA-seq | TF families, JERF and bZIP Up regulation of OeNHX7, OeP5CS, OeRD19A and OePetD |

[80] [81] |

|

| Date Palm | Combined heat and drought |

Proteomics | Increased abundance of Heat Shock Proteins (HSP), redox homeostasis proteins and proteins involved in isoprene production | [82] |

|

Salt |

Multi-omics |

Converging gene expression and protein abundance associated with osmotic adjustment, reactive oxygen species scavenging in leaves, and remodeling of the ribosome-associated proteome in salt-exposed root cells. Induction of Salt Overly Sensitive (SOS) genes, PdSOS2;1, PdSOS2;2, PdSOS4, PdSOS5, and PdCIPK11 |

[83] [84] |

|

|

Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) |

Differential DNA methylation and gene expression alterations in roots |

[85] |

||

| Pomegranate | Salt | Transcriptomics/RNA-seq | Spatiotemporal regulation of SWEET genes DEGs associated with ABA- and Ca2+-related and MAPK signal transduction pathways (ABA-receptors, Ca2+-sensors, MAPK cascades, TFs) and downstream functional genes coding for HSPs, LEAs, AQPs and PODs. Induction of proline, total soluble sugar, and SOD/POD activities and differential gene expression |

[86] [87] [88] |

|

Cold |

Transcriptomics/RNA-seq |

Upregulation of CBFs genes PgCBF3, PgCBF7 Differentially expressed genes related to TFs, photosynthesis, osmotic regulation system, and hormone signal transduction, sucrose metabolism Induction of beta-amylase, PgBAM4, and increase in soluble sugar content |

[89] [90] [91] |

2.3. Microbiota Attributes Related to Abiotic Stress

| Species | Stress type | Microbe type | Microbial effect – molecular response | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grapevine | Drought |

Rhizosphere associated bacteria | Protection against Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) – accumulation of terpenes | [93] |

| Drought | Root associated microbiome | Water stress-protection |

[92] |

|

| Drought | Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) | Drought tolerance by increasing the accumulation of osmolytes, triggering antioxidant processes and regulating the expression of key stress-responsive genes | [96] |

|

| Heat |

Marine Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria Consortia | Heat stress tolerance |

[98] | |

| Heat | AMF |

Enhancement of physiological indices Modulation of miRNAs and stress-related transcription factors and proteins related to antioxidant pathways |

[106] |

|

| Olive tree | Drought |

Pseudomonas reactans Ph3R3 | Enhancement of plant performance by reducing water loss, improving N levels, net CO2 assimilation rate, and antioxidant capacity. | [108] |

| Drought | PGPB consortia sampled from soil and rhizosphere of Tunisian olive orchards | Conferred tolerance to both drought-susceptible and drought-tolerant cultivars |

[109] |

|

| Drought | AMF (Rhizophagus irregularis) |

Reinforced tolerance to water deficit by enhancing olive plant growth, improving water status, accumulation of osmolytes and antioxidants and phytohormone regulation | [110] |

|

| Drought | AMF (Rhizophagus irregularis) | Enhanced water deficit tolerance by increasing net carbon fixation, water use efficiency and antioxidant defenses | [111] |

|

| Salt | PGPB Bacillus G7 |

Improved physiological and metabolic parameters, increased photosynthetic capacity, net carbon fixation, water use efficiency, and accumulation of osmolytes and antioxidant | [106] 131 |

|

| Salt | AMF mixtrure of Glomus deserticola and Gigaspora margarita | Alleviation of the stress imposed by irrigation with salt-enriched wastewater. | [112] | |

| Date Palm | Drought |

Selected date plam root bacterial endophytes | Increased the biomass of date palms exposed to recurrent drought stress cycles in greenhouse experiment |

[113] |

| Salt |

Piriformospora indica endophyte |

Mitigated the detrimental effects of salt stress through ion homeostasis and nutrient uptake, antioxidant activity, and upregulation of stress-responsive genes. | [114,115] |

|

| Salt |

Enterobacter cloacae SQU-2 (SQU-2)’ | Improved the growth of Arabidopsis thaliana Columbia (Col-0) seedlings under both normal and salt stress conditions through production of microbial volatile compounds mVOCs. | [116] | |

| Pomegranate | Drought | AMF strains Rhizophagus intraradices (GA5 and GC2) | Early inoculation with AMF, especially for the GC2 strain, offers protection against drought. Enhanced antioxidant defenses, specifically the ROS-scavenging enzymes superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and ascorbate peroxidase (APX), in shoots. | [117] |

3. Olive Tree

3.1. Climate Challenges

3.2. The Genetic and Epigenetic Component

3.3. The Microbiota Component

4. Other Woody Fruit Crops

4.1. Date Palm

4.1.1. Genetic/Epigenetic Factors in Abiotic Stress

4.1.2. Microbiota Aspects and Abiotic Stress

4.2. Pomegranate

4.2.1. Genetic Aspects and Transcriptional Regulation

4.2.2. Microbiome and Abiotic Stress

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jägermeyr, J.; Müller, C.; Ruane, A.C.; Elliott, J.; Balkovic, J.; Castillo, O.; Faye, B.; Foster, I.; Folberth, C.; Franke, J.A.; et al. Climate Impacts on Global Agriculture Emerge Earlier in New Generation of Climate and Crop Models. Nat Food 2021, 2, 873–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckardt, N.A.; Ainsworth, E.A.; Bahuguna, R.N.; Broadley, M.R.; Busch, W.; Carpita, N.C.; Castrillo, G.; Chory, J.; DeHaan, L.R.; Duarte, C.M.; et al. Climate Change Challenges, Plant Science Solutions. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 24–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Sixth Assessment Report. Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability.

- Verslues, P.E.; Bailey-Serres, J.; Brodersen, C.; Buckley, T.N.; Conti, L.; Christmann, A.; Dinneny, J.R.; Grill, E.; Hayes, S.; Heckman, R.W.; et al. Burning Questions for a Warming and Changing World: 15 Unknowns in Plant Abiotic Stress. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 67–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varotto, S.; Tani, E.; Abraham, E.; Krugman, T.; Kapazoglou, A.; Melzer, R.; Radanović, A.; Miladinović, D. Epigenetics: Possible Applications in Climate-Smart Crop Breeding. J Exp Bot 2020, 71, 5223–5236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventouris, Y.E.; Tani, E.; Avramidou, E.V.; Abraham, E.M.; Chorianopoulou, S.N.; Vlachostergios, D.N.; Papadopoulos, G.; Kapazoglou, A. Recurrent Water Deficit and Epigenetic Memory in Medicago Sativa L. Varieties. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosou, V.; Kapazoglou, A.; Letsiou, S.; Tsaftaris, A.S.; Argiriou, A. Drought Induces Variation in the DNA Methylation Status of the Barley HvDME Promoter. J Plant Res 2021, 134, 1351–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, F.T.; Griffiths, R.I.; Knight, C.G.; Nicolitch, O.; Williams, A. Harnessing Rhizosphere Microbiomes for Drought-Resilient Crop Production. Science (1979) 2020, 368, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.; Batista, B.D.; Bazany, K.E.; Singh, B.K. Plant–Microbiome Interactions under a Changing World: Responses, Consequences and Perspectives. New Phytologist 2022, 234, 1951–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Singh, B.N.; Dwivedi, P.; Rajawat, M.V.S. Interference of Climate Change on Plant-Microbe Interaction: Present and Future Prospects. Frontiers in Agronomy 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwan, D.; Rashid, M.d.M.; Vaishnav, A. Current Understanding of Plant-Microbe Interaction through the Lenses of Multi-Omics Approaches and Their Benefits in Sustainable Agriculture. Microbiol Res 2022, 265, 127180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Patil, S.; Shaikh, A.; Jamla, M.; Kumar, V. Modern Omics Toolbox for Producing Combined and Multifactorial Abiotic Stress Tolerant Plants. Plant Stress 2024, 11, 100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikiran, K.T.; Thribhuvan, R.; Anilkumar, C.; Kallugudi, J.; Prakash, N.R.; Adavi B, S.; Sunitha, N.C.; Abhijith, K.P. Harnessing the Power of Genomics to Develop Climate-Smart Crop Varieties: A Comprehensive Review. J Environ Manage 2025, 373, 123461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, N.; Singh, S.; Garg, R. Unlocking Crops’ Genetic Potential: Advances in Genome and Epigenome Editing of Regulatory Regions. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2025, 83, 102669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaridi, E.; Kapazoglou, A.; Gerakari, M.; Kleftogianni, K.; Passa, K.; Sarri, E.; Papasotiropoulos, V.; Tani, E.; Bebeli, P.J. Crop Landraces and Indigenous Varieties: A Valuable Source of Genes for Plant Breeding. Plants 2024, 13, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agius, D.R.; Kapazoglou, A.; Avramidou, E.; Baranek, M.; Carneros, E.; Caro, E.; Castiglione, S.; Cicatelli, A.; Radanovic, A.; Ebejer, J.-P.; et al. Exploring the Crop Epigenome: A Comparison of DNA Methylation Profiling Techniques. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapazoglou, A.; Gerakari, M.; Lazaridi, E.; Kleftogianni, K.; Sarri, E.; Tani, E.; Bebeli, P.J. Crop Wild Relatives: A Valuable Source of Tolerance to Various Abiotic Stresses. Plants 2023, 12, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Dias, M.C.; Freitas, H. Drought and Salinity Stress Responses and Microbe-Induced Tolerance in Plants. Front Plant Sci 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikiciuk, G.; Miller, T.; Kisiel, A.; Cembrowska-Lech, D.; Mikiciuk, M.; Łobodzińska, A.; Bokszczanin, K. Harnessing Beneficial Microbes for Drought Tolerance: A Review of Ecological and Agricultural Innovations. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Choudhary, P.; Chakdar, H.; Shukla, P. Molecular Insights and Omics-Based Understanding of Plant–Microbe Interactions under Drought Stress. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2024, 40, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, P.; Mahawar, H.; Agarrwal, R.; Kajal; Gautam, V.; Deshmukh, R. Advancement in the Molecular Perspective of Plant-Endophytic Interaction to Mitigate Drought Stress in Plants. Front Microbiol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenkoornhuyse, P.; Quaiser, A.; Duhamel, M.; Le Van, A.; Dufresne, A. The Importance of the Microbiome of the Plant Holobiont. New Phytologist 2015, 206, 1196–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.-H.; Muhammad Aslam, M.; Gao, Y.-Y.; Dai, L.; Hao, G.-F.; Wei, Z.; Chen, M.-X.; Dini-Andreote, F. Microbiome-Mediated Signal Transduction within the Plant Holobiont. Trends Microbiol 2023, 31, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravanbakhsh, M.; Kowalchuk, G.A.; Jousset, A. Targeted Plant Hologenome Editing for Plant Trait Enhancement. New Phytologist 2021, 229, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.; Leach, J.E.; Tringe, S.G.; Sa, T.; Singh, B.K. Plant–Microbiome Interactions: From Community Assembly to Plant Health. Nat Rev Microbiol 2020, 18, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, N.; Wang, T.; Kuzyakov, Y. Rhizosphere Bacteriome Structure and Functions. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.; Sarsaiya, S.; Singh, R.; Gong, Q.; Wu, Q.; Shi, J. Omics Approaches in Understanding the Benefits of Plant-Microbe Interactions. Front Microbiol 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doddavarapu, B.; Lata, C.; Shah, J.M. Epigenetic Regulation Influenced by Soil Microbiota and Nutrients: Paving Road to Epigenome Editing in Plants. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 2024, 1868, 130580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Dong, Z.; Chiniquy, D.; Pierroz, G.; Deng, S.; Gao, C.; Diamond, S.; Simmons, T.; Wipf, H.M.-L.; Caddell, D.; et al. Genome-Resolved Metagenomics Reveals Role of Iron Metabolism in Drought-Induced Rhizosphere Microbiome Dynamics. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zombardo, A.; Meneghetti, S.; Morreale, G.; Calò, A.; Costacurta, A.; Storchi, P. Study of Inter- and Intra-Varietal Genetic Variability in Grapevine Cultivars. Plants 2022, 11, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Duan, S.; Xia, Q.; Liang, Z.; Dong, X.; Margaryan, K.; Musayev, M.; Goryslavets, S.; Zdunić, G.; Bert, P.-F.; et al. Dual Domestications and Origin of Traits in Grapevine Evolution. Science (1979) 2023, 379, 892–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolkovich, E.M.; García de Cortázar-Atauri, I.; Morales-Castilla, I.; Nicholas, K.A.; Lacombe, T. From Pinot to Xinomavro in the World’s Future Wine-Growing Regions. Nat Clim Chang 2018, 8, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollat, N.; Marguerit, E.; de Miguel, M.; Coupel-Ledru, A.; Cookson, S.J.; van Leeuwen, C.; Vivin, P.; Gallusci, P.; Segura, V.; Duchêne, E. Moving towards Grapevine Genotypes Better Adapted to Abiotic Constraints. Vitis - Journal of Grapevine Research 2023, 62, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIV 2024, I.O. of V. and Wine. Available online: Http://Www.Oiv.Int/En/the-International-Organisation-of-Vine-and-Wine (Accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Bernardo, S.; Dinis, L.-T.; Machado, N.; Moutinho-Pereira, J. Grapevine Abiotic Stress Assessment and Search for Sustainable Adaptation Strategies in Mediterranean-like Climates. A Review. Agron Sustain Dev 2018, 38, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venios, X.; Korkas, E.; Nisiotou, A.; Banilas, G. Grapevine Responses to Heat Stress and Global Warming. Plants 2020, 9, 1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavromatis, T.; Koufos, G.C.; Koundouras, S.; Jones, G.V. Adaptive Capacity of Winegrape Varieties Cultivated in Greece to Climate Change: Current Trends and Future Projections. OENO One 2020, 54, 1201–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venios, X.; Gkizi, D.; Nisiotou, A.; Korkas, E.; Tjamos, S.; Zamioudis, C.; Banilas, G. Emerging Roles of Epigenetics in Grapevine and Winegrowing. Plants 2024, 13, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacifico, D.; Squartini, A.; Crucitti, D.; Barizza, E.; Lo Schiavo, F.; Muresu, R.; Carimi, F.; Zottini, M. The Role of the Endophytic Microbiome in the Grapevine Response to Environmental Triggers. Front Plant Sci 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francioli, D.; Strack, T.; Dries, L.; Voss-Fels, K.P.; Geilfus, C. Roots of Resilience: Optimizing Microbe-rootstock Interactions to Enhance Vineyard Productivity. PLANTS, PEOPLE, PLANET, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudge, K.; Janick, J.; Scofield, S.; Goldschmidt, E.E. A History of Grafting. In Horticultural Reviews; Wiley, 2009; pp. 437–493. [Google Scholar]

- Warschefsky, E.J.; Klein, L.L.; Frank, M.H.; Chitwood, D.H.; Londo, J.P.; von Wettberg, E.J.B.; Miller, A.J. Rootstocks: Diversity, Domestication, and Impacts on Shoot Phenotypes. Trends Plant Sci 2016, 21, 418–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migicovsky, Z.; Cousins, P.; Jordan, L.M.; Myles, S.; Striegler, R.K.; Verdegaal, P.; Chitwood, D.H. Grapevine Rootstocks Affect Growth-related Scion Phenotypes. Plant Direct 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Fei, Y.; Howell, K.; Chen, D.; Clingeleffer, P.; Zhang, P. Rootstocks for Grapevines Now and into the Future: Selection of Rootstocks Based on Drought Tolerance, Soil Nutrient Availability, and Soil PH. Aust J Grape Wine Res 2024, 2024, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapazoglou, A.; Tani, E.; Avramidou, E.V.; Abraham, E.M.; Gerakari, M.; Megariti, S.; Doupis, G.; Doulis, A.G. Epigenetic Changes and Transcriptional Reprogramming Upon Woody Plant Grafting for Crop Sustainability in a Changing Environment. Front Plant Sci 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darriaut, R.; Lailheugue, V.; Masneuf-Pomarède, I.; Marguerit, E.; Martins, G.; Compant, S.; Ballestra, P.; Upton, S.; Ollat, N.; Lauvergeat, V. Grapevine Rootstock and Soil Microbiome Interactions: Keys for a Resilient Viticulture. Hortic Res 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettenfeld, P.; Cadena i Canals, J.; Jacquens, L.; Fernandez, O.; Fontaine, F.; van Schaik, E.; Courty, P.-E.; Trouvelot, S. The Microbiota of the Grapevine Holobiont: A Key Component of Plant Health. J Adv Res 2022, 40, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avramidou, E.; Masaoutis, I.; Pitsoli, T.; Kapazoglou, A.; Pikraki, M.; Trantas, E.; Nikolantonakis, M.; Doulis, A. Analysis of Wine-Producing Vitis Vinifera L. Biotypes, Autochthonous to Crete (Greece), Employing Ampelographic and Microsatellite Markers. Life 2023, 13, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenti, M.; Lorenzi, S.; Bianchedi, P.L.; Grossi, D.; Failla, O.; Grando, M.S.; Emanuelli, F. Candidate Genes and SNPs Associated with Stomatal Conductance under Drought Stress in Vitis. BMC Plant Biol 2021, 21, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsivelikas, A.L.; Avramidou, E.V.; Ralli, P.E.; Ganopoulos, I.V.; Moysiadis, T.; Kapazoglou, A.; Aravanopoulos, F.A.; Doulis, A.G. Genetic Diversity of Greek Grapevine ( Vitis Vinifera L.) Cultivars Using Ampelographic and Microsatellite Markers. Plant Genet Resour 2022, 20, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lorenzis, G.; Mercati, F.; Bergamini, C.; Cardone, M.F.; Lupini, A.; Mauceri, A.; Caputo, A.R.; Abbate, L.; Barbagallo, M.G.; Antonacci, D.; et al. SNP Genotyping Elucidates the Genetic Diversity of Magna Graecia Grapevine Germplasm and Its Historical Origin and Dissemination. BMC Plant Biol 2019, 19, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinov, L.; Magris, G.; Di Gaspero, G.; Morgante, M.; Maletić, E.; Bubola, M.; Pejić, I.; Zdunić, G. Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) Analysis Reveals Ancestry and Genetic Diversity of Cultivated and Wild Grapevines in Croatia. BMC Plant Biol 2024, 24, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villano, C.; Procino, S.; Blaiotta, G.; Carputo, D.; D’Agostino, N.; Di Serio, E.; Fanelli, V.; La Notte, P.; Miazzi, M.M.; Montemurro, C.; et al. Genetic Diversity and Signature of Divergence in the Genome of Grapevine Clones of Southern Italy Varieties. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villano, C.; Aiese Cigliano, R.; Esposito, S.; D’Amelia, V.; Iovene, M.; Carputo, D.; Aversano, R. DNA-Based Technologies for Grapevine Biodiversity Exploitation: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Agronomy 2022, 12, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Fan, D.; Li, H.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, M.; Liu, J.; Song, Y.; He, J.; Xu, W.; et al. Characterization and Identification of Grapevine Heat Stress-Responsive MicroRNAs Revealed the Positive Regulated Function of Vvi-MiR167 in Thermostability. Plant Science 2023, 329, 111623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Song, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Fan, D.; Liu, M.; Ren, Y.; Xi, X.; et al. Development, Identification and Validation of a Novel SSR Molecular Marker for Heat Resistance of Grapes Based on MiRNA. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Cao, S.; Wang, X.; Huang, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, W.; Leng, X.; Peng, Y.; Wang, N.; et al. The Complete Reference Genome for Grapevine ( Vitis Vinifera L.) Genetics and Breeding. Hortic Res 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochetel, N.; Minio, A.; Guarracino, A.; Garcia, J.F.; Figueroa-Balderas, R.; Massonnet, M.; Kasuga, T.; Londo, J.P.; Garrison, E.; Gaut, B.S.; et al. A Super-Pangenome of the North American Wild Grape Species. Genome Biol 2023, 24, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, N.; Su, Y.; Long, Q.; Peng, Y.; Shangguan, L.; Zhang, F.; Cao, S.; Wang, X.; Ge, M.; et al. Grapevine Pangenome Facilitates Trait Genetics and Genomic Breeding. Nat Genet 2024, 56, 2804–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magon, G.; De Rosa, V.; Martina, M.; Falchi, R.; Acquadro, A.; Barcaccia, G.; Portis, E.; Vannozzi, A.; De Paoli, E. Boosting Grapevine Breeding for Climate-Smart Viticulture: From Genetic Resources to Predictive Genomics. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Liu, Q.; Li, W.; Yan, J.; Fernie, A.R. Raffinose Family Oligosaccharides: Crucial Regulators of Plant Development and Stress Responses. CRC Crit Rev Plant Sci 2022, 41, 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhao, F.; Zheng, T.; Liu, Z.; Ji, X.; Zhang, Z.; Pervaiz, T.; Shangguan, L.; Fang, J. Whole-Genome Re-Sequencing, Diversity Analysis, and Stress-Resistance Analysis of 77 Grape Rootstock Genotypes. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zheng, Q.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, W.; Deng, Z.; Zhou, P.; Fang, Y.; Chen, K.; Zhang, K. Physiology and Transcriptome Profiling Reveal the Drought Tolerance of Five Grape Varieties under High Temperatures. J Integr Agric 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.W.; Shinde, H.; Tesfamicael, K.; Hu, Y.; Fruzangohar, M.; Tricker, P.; Baumann, U.; Edwards, E.J.; Rodríguez López, C.M. Global Transcriptome and Gene Co-Expression Network Analyses Reveal Regulatory and Non-Additive Effects of Drought and Heat Stress in Grapevine. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, F.; Phillip, F.O.; Liu, G.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H. Transcriptomic and Physiological Analyses Reveal Different Grape Varieties Response to High Temperature Stress. Front Plant Sci 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Zeng, Z.; Liu, Z.; Xia, R. Small RNAs, Emerging Regulators Critical for the Development of Horticultural Traits. Hortic Res 2018, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrandino, A.; Pagliarani, C.; Pérez-Álvarez, E.P. Secondary Metabolites in Grapevine: Crosstalk of Transcriptional, Metabolic and Hormonal Signals Controlling Stress Defence Responses in Berries and Vegetative Organs. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliarani, C.; Vitali, M.; Ferrero, M.; Vitulo, N.; Incarbone, M.; Lovisolo, C.; Valle, G.; Schubert, A. The Accumulation of MiRNAs Differentially Modulated by Drought Stress Is Affected by Grafting in Grapevine. Plant Physiol 2017, 173, 2180–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Xu, T.; Ju, Y.; Lei, Y.; Zhang, F.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Jin, L.; Meng, J. MicroRNAs Behave Differently to Drought Stress in Drought-Tolerant and Drought-Sensitive Grape Genotypes. Environ Exp Bot 2023, 207, 105223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniatis, G.; Tani, E.; Katsileros, A.; Avramidou, E.V.; Pitsoli, T.; Sarri, E.; Gerakari, M.; Goufa, M.; Panagoulakou, M.; Xipolitaki, K.; et al. Genetic and Epigenetic Responses of Autochthonous Grapevine Cultivars from the ‘Epirus’ Region of Greece upon Consecutive Drought Stress. Plants 2023, 13, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, E.; Jiang, L.; Cui, H.; Li, X.; Yan, Y.; Liu, Q.; Chen, Z.; Li, M. Only Plant-Based Food Additives: An Overview on Application, Safety, and Key Challenges in the Food Industry. Food Reviews International 2023, 39, 5132–5163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zhang, M.; Feng, M.; Liu, G.; Torregrosa, L.; Tao, X.; Ren, R.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, J.; et al. MiR156b-Targeted VvSBP8/13 Functions Downstream of the Abscisic Acid Signal to Regulate Anthocyanins Biosynthesis in Grapevine Fruit under Drought. Hortic Res 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Zhang, X.; Du, B.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, T.-H. MicroRNA156ab Regulates Apple Plant Growth and Drought Tolerance by Targeting Transcription Factor MsSPL13. Plant Physiol 2023, 192, 1836–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Du, Y.; Xiang, J.; Zheng, T.; Cheng, J.; Wu, J. Integrated MRNA and MiRNA Transcriptome Analysis of Grape in Responses to Salt Stress. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooy, S.S.B.; Ghabooli, M.; Salekdeh, G.H.; Fard, E.M.; Karimi, R.; Fakhrfeshani, M.; Gholami, M. Identification of Novel Cold Stress Responsive MicroRNAs and Their Putative Targets in ‘Sultana’ Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera) Using RNA Deep Sequencing. Acta Physiol Plant 2023, 45, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qiao, Z.; Li, X.; Ren, Z.; Xu, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, K. 5-Azacytidine Enhances the Aluminum Tolerance of Grapes by Reducing the DNA Methylation Level. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr 2024, 24, 6922–6937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Li, Q.; Gichuki, D.K.; Hou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Xu, C.; Fang, L.; Gong, L.; Zheng, B.; et al. Genome-Wide Profiling of Histone H3 Lysine 27 Trimethylation and Its Modification in Response to Chilling Stress in Grapevine Leaves. Hortic Plant J 2023, 9, 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Mohamed, M.S.M.; Aini, N.; Kuang, Y.; Liang, Z. CRISPR/Cas in Grapevine Genome Editing: The Best Is Yet to Come. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benny, J.; Marchese, A.; Giovino, A.; Marra, F.P.; Perrone, A.; Caruso, T.; Martinelli, F. Gaining Insight into Exclusive and Common Transcriptomic Features Linked to Drought and Salinity Responses across Fruit Tree Crops. Plants 2020, 9, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazakos, C.; Manioudaki, M.E.; Therios, I.; Voyiatzis, D.; Kafetzopoulos, D.; Awada, T.; Kalaitzis, P. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of Two Olive Cultivars in Response to NaCl-Stress. PLoS One 2012, 7, e42931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.; Regni, L.; Bocchini, M.; Mariotti, R.; Cultrera, N.G.M.; Mancuso, S.; Googlani, J.; Chakerolhosseini, M.R.; Guerrero, C.; Albertini, E.; et al. Physiological, Epigenetic and Genetic Regulation in Some Olive Cultivars under Salt Stress. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghirardo, A.; Nosenko, T.; Kreuzwieser, J.; Winkler, J.B.; Kruse, J.; Albert, A.; Merl-Pham, J.; Lux, T.; Ache, P.; Zimmer, I.; et al. Protein Expression Plasticity Contributes to Heat and Drought Tolerance of Date Palm. Oecologia 2021, 197, 903–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, H.M.; Franzisky, B.L.; Messerer, M.; Du, B.; Lux, T.; White, P.J.; Carpentier, S.C.; Winkler, J.B.; Schnitzler, J.; El-Serehy, H.A.; et al. Integrative Multi-omics Analyses of Date Palm ( Phoenix Dactylifera ) Roots and Leaves Reveal How the Halophyte Land Plant Copes with Sea Water. Plant Genome 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, N.; Fu, H.; Wang, F.; Wen, M.; Chang, H.; Wu, J.; Abdelaala, W.B.; Luo, Q.; Li, Y.; et al. Salt Stress Modulates the Landscape of Transcriptome and Alternative Splicing in Date Palm (Phoenix Dactylifera L.). Front Plant Sci 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Harrasi, I.; Al-Yahyai, R.; Yaish, M.W. Differential DNA Methylation and Transcription Profiles in Date Palm Roots Exposed to Salinity. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0191492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumawat, S.; Sharma, Y.; Vats, S.; Sudhakaran, S.; Sharma, S.; Mandlik, R.; Raturi, G.; Kumar, V.; Rana, N.; Kumar, A.; et al. Understanding the Role of SWEET Genes in Fruit Development and Abiotic Stress in Pomegranate (Punica Granatum L.). Mol Biol Rep 2022, 49, 1329–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, J.; Gu, M.; Yuan, Z. Transcriptomic Profiling of Pomegranate Provides Insights into Salt Tolerance. Agronomy 2019, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Wang, C.; Mei, J.; Feng, L.; Wu, Q.; Yin, Y. Transcriptome Analysis Revealed the Response Mechanism of Pomegranate to Salt Stress. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Tong, R.; Wang, S.; Yao, J.; Jiao, J.; Wan, R.; Wang, M.; Shi, J.; Zheng, X. Overexpression of PgCBF3 and PgCBF7 Transcription Factors from Pomegranate Enhances Freezing Tolerance in Arabidopsis under the Promoter Activity Positively Regulated by PgICE1. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 9439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.; Chai, Y.; Hao, Q.; Ma, Y.; Wan, W.; Liu, H.; Diao, M. Transcriptomic and Physiological Analysis Reveals Crucial Biological Pathways Associated with Low-Temperature Stress in Tunisian Soft-Seed Pomegranate ( Punica Granatum L.). J Plant Interact 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xu, S.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, J. A Genome-Wide Analysis of the BAM Gene Family and Identification of the Cold-Responsive Genes in Pomegranate (Punica Granatum L.). Plants 2024, 13, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolli, E.; Marasco, R.; Vigani, G.; Ettoumi, B.; Mapelli, F.; Deangelis, M.L.; Gandolfi, C.; Casati, E.; Previtali, F.; Gerbino, R.; et al. Improved Plant Resistance to Drought Is Promoted by the Root-associated Microbiome as a Water Stress-dependent Trait. Environ Microbiol 2015, 17, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, M.V.; Purpora, R.; Bottini, R.; Piccoli, P. Rhizosphere Associated Bacteria Trigger Accumulation of Terpenes in Leaves of Vitis Vinifera L. Cv. Malbec That Protect Cells against Reactive Oxygen Species. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2016, 106, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolli, E.; Marasco, R.; Saderi, S.; Corretto, E.; Mapelli, F.; Cherif, A.; Borin, S.; Valenti, L.; Sorlini, C.; Daffonchio, D. Root-Associated Bacteria Promote Grapevine Growth: From the Laboratory to the Field. Plant Soil 2017, 410, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, N.; Goicoechea, N.; Zamarreño, A.M.; Carmen Antolín, M. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis Affects ABA Metabolism during Berry Ripening in Vitis Vinifera L. Cv. Tempranillo Grown under Climate Change Scenarios. Plant Science 2018, 274, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Wang, H.; Li, H. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Enhance Drought Stress Tolerance by Regulating Osmotic Balance, the Antioxidant System, and the Expression of Drought-Responsive Genes in Vitis Vinifera L. Aust J Grape Wine Res 2023, 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinale, M.; Minervini, F.; De Angelis, M.; Papadia, P.; Migoni, D.; Dimaglie, M.; Dinu, D.G.; Quarta, C.; Selleri, F.; Caccioppola, A.; et al. Vineyard Establishment under Exacerbated Summer Stress: Effects of Mycorrhization on Rootstock Agronomical Parameters, Leaf Element Composition and Root-Associated Bacterial Microbiota. Plant Soil 2022, 478, 613–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreiras, J.; Cruz-Silva, A.; Fonseca, B.; Carvalho, R.C.; Cunha, J.P.; Proença Pereira, J.; Paiva-Silva, C.; A. Santos, S.; Janeiro Sequeira, R.; Mateos-Naranjo, E.; et al. Improving Grapevine Heat Stress Resilience with Marine Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria Consortia. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.; Zhong, H.; Patel, M.K.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Su, J.; Zhang, F.; Wu, X. Integrated Omics-Based Exploration for Temperature Stress Resilience: An Approach to Smart Grape Breeding Strategies. Plant Stress 2024, 11, 100356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbi, A.; Acedo, A.; Imam, N.; Santini, R.G.; Ortiz-Álvarez, R.; Ellegaard-Jensen, L.; Belda, I.; Hansen, L.H. A Global Microbiome Survey of Vineyard Soils Highlights the Microbial Dimension of Viticultural Terroirs. Commun Biol 2022, 5, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, L.; Gentimis, T.; Downie, A.B.; Lopez, C.M.R. Grapevine Rootstock and Scion Genotypes’ Symbiosis with Soil Microbiome: A Machine Learning Revelation for Climate-Resilient Viticulture 2024.

- Griggs, R.G.; Steenwerth, K.L.; Mills, D.A.; Cantu, D.; Bokulich, N.A. Sources and Assembly of Microbial Communities in Vineyards as a Functional Component of Winegrowing. Front Microbiol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colautti, A.; Mian, G.; Tomasi, D.; Bell, L.; Marcuzzo, P. Exploring the Influence of Soil Salinity on Microbiota Dynamics in Vitis Vinifera Cv. “Glera”: Insights into the Rhizosphere, Carposphere, and Yield Outcomes. Diversity (Basel) 2024, 16, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jatan, R.; Chauhan, P.S.; Lata, C. Pseudomonas Putida Modulates the Expression of MiRNAs and Their Target Genes in Response to Drought and Salt Stresses in Chickpea (Cicer Arietinum L.). Genomics 2019, 111, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, M.; Zhu, J.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Jing, M.; Chen, Y.; Xu, X.; Jiang, J.; et al. Long-Term Effect of Epigenetic Modification in Plant–Microbe Interactions: Modification of DNA Methylation Induced by Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria Mediates Promotion Process. Microbiome 2022, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, C.; Coito, J.L.; Cardoso, H.; Marques da Silva, J.; Pereira, H.S.; Viegas, W.; Nogales, A. Dynamic Regulation of Grapevine’s MicroRNAs in Response to Mycorrhizal Symbiosis and High Temperature. Plants 2023, 12, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sportes, A.; Hériché, M.; Mounier, A.; Durney, C.; van Tuinen, D.; Trouvelot, S.; Wipf, D.; Courty, P.E. Comparative RNA Sequencing-Based Transcriptome Profiling of Ten Grapevine Rootstocks: Shared and Specific Sets of Genes Respond to Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. Mycorrhiza 2023, 33, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, M.C.; Silva, S.; Galhano, C.; Lorenzo, P. Olive Tree Belowground Microbiota: Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria and Fungi. Plants 2024, 13, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azri, R.; Lamine, M.; Bensalem-Fnayou, A.; Hamdi, Z.; Mliki, A.; Ruiz-Lozano, J.M.; Aroca, R. Genotype-Dependent Response of Root Microbiota and Leaf Metabolism in Olive Seedlings Subjected to Drought Stress. Plants 2024, 13, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aganchich, B.; Wahbi, S.; Yaakoubi, A.; El-Aououad, H.; Bota, J. Effect of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Inoculation on Growth and Physiology Performance of Olive Trees under Regulated Deficit Irrigation and Partial Rootzone Drying. South African Journal of Botany 2022, 148, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekaya, M.; Dabbaghi, O.; Guesmi, A.; Attia, F.; Chehab, H.; Khezami, L.; Algathami, F.K.; Ben Hamadi, N.; Hammami, M.; Prinsen, E.; et al. Arbuscular Mycorrhizas Modulate Carbohydrate, Phenolic Compounds and Hormonal Metabolism to Enhance Water Deficit Tolerance of Olive Trees (Olea Europaea). Agric Water Manag 2022, 274, 107947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassena, A.; Zouari, M.; Trabelsi, L.; Decou, R.; Ben Amar, F.; Chaari, A.; Soua, N.; Labrousse, P.; Khabou, W.; Zouari, N. Potential Effects of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Mitigating the Salinity of Treated Wastewater in Young Olive Plants (Olea Europaea L. Cv. Chetoui). Agric Water Manag 2021, 245, 106635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherif, H.; Marasco, R.; Rolli, E.; Ferjani, R.; Fusi, M.; Soussi, A.; Mapelli, F.; Blilou, I.; Borin, S.; Boudabous, A.; et al. Oasis Desert Farming Selects Environment-specific Date Palm Root Endophytic Communities and Cultivable Bacteria That Promote Resistance to Drought. Environ Microbiol Rep 2015, 7, 668–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabeem, M.; Abdul Aziz, M.; Mullath, S.K.; Brini, F.; Rouached, H.; Masmoudi, K. Enhancing Growth and Salinity Stress Tolerance of Date Palm Using Piriformospora Indica. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Abdul Aziz, M.; Sabeem, M.; Kutty, M.S.; Sivasankaran, S.K.; Brini, F.; Xiao, T.T.; Blilou, I.; Masmoudi, K. Date Palm Transcriptome Analysis Provides New Insights on Changes in Response to High Salt Stress of Colonized Roots with the Endophytic Fungus Piriformospora Indica. Front Plant Sci 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, G.A.; Yaish, M.W. Isolation and Functional Characterization of a MVOC Producing Plant-Growth-Promoting Bacterium Isolated from the Date Palm Rhizosphere. Rhizosphere 2020, 16, 100267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bompadre, M.J.; Silvani, V.A.; Bidondo, L.F.; Ríos de Molina, M.D.C.; Colombo, R.P.; Pardo, A.G.; Godeas, A.M. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Alleviate Oxidative Stress in Pomegranate Plants Growing under Different Irrigation Conditions. Botany 2014, 92, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez, C.M.; Trujillo, I.; Martinez-Urdiroz, N.; Barranco, D.; Rallo, L.; Marfil, P.; Gaut, B.S. Olive Domestication and Diversification in the Mediterranean Basin. New Phytologist 2015, 206, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langgut, D.; Garfinkel, Y. 7000-Year-Old Evidence of Fruit Tree Cultivation in the Jordan Valley, Israel. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 7463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTATS. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL;IOC, https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/) FAOSTATS,Https://Www.Fao.Org/Faostat/En/#data/QCL;IOC, Https://Www.Internationaloliveoil.Org/).

- El Yamani, M.; Cordovilla, M. del P. Tolerance Mechanisms of Olive Tree (Olea Europaea) under Saline Conditions. Plants 2024, 13, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, H.; Moriondo, M.; Leolini, L.; Santos, J.A. Mediterranean Olive Orchards under Climate Change: A Review of Future Impacts and Adaptation Strategies. Agronomy 2020, 11, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoni, M.; Mercado-Blanco, J. Confronting Stresses Affecting Olive Cultivation from the Holobiont Perspective. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrameche, O.; Tul, S.; Manolikaki, I.; Digalaki, N.; Kaltsa, I.; Psarras, G.; Koubouris, G. Optimizing Agroecological Measures for Climate-Resilient Olive Farming in the Mediterranean. Plants 2024, 13, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nteve, G.-M.; Kostas, S.; Polidoros, A.N.; Madesis, P.; Nianiou-Obeidat, I. Adaptation Mechanisms of Olive Tree under Drought Stress: The Potential of Modern Omics Approaches. Agriculture 2024, 14, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ollas, C.; Morillón, R.; Fotopoulos, V.; Puértolas, J.; Ollitrault, P.; Gómez-Cadenas, A.; Arbona, V. Facing Climate Change: Biotechnology of Iconic Mediterranean Woody Crops. Front Plant Sci 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazakos, C.; Alexiou, K.G.; Ramos-Onsins, S.; Koubouris, G.; Tourvas, N.; Xanthopoulou, A.; Mellidou, I.; Moysiadis, T.; Vourlaki, I.; Metzidakis, I.; et al. Whole Genome Scanning of a Mediterranean Basin Hotspot Collection Provides New Insights into Olive Tree Biodiversity and Biology. The Plant Journal 2023, 116, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.; Mariotti, R.; Valeri, M.C.; Regni, L.; Lilli, E.; Albertini, E.; Proietti, P.; Businelli, D.; Baldoni, L. Characterization of Differentially Expressed Genes under Salt Stress in Olive. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 23, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullones, A.; Castro, A.J.; Lima-Cabello, E.; Alché, J.d.D.; Luque, F.; Claros, M.G.; Fernandez-Pozo, N. OliveAtlas: A Gene Expression Atlas Tool for Olea Europaea. Plants 2023, 12, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, M.C.; Araújo, M.; Ma, Y. A Bio-Based Strategy for Sustainable Olive Performance under Water Deficit Conditions. Plant Stress 2024, 11, 100342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galicia-Campos, E.; García-Villaraco, A.; Montero-Palmero, Ma.B.; Gutiérrez-Mañero, F.J.; Ramos-Solano, B. Bacillus G7 Improves Adaptation to Salt Stress in Olea Europaea L. Plantlets, Enhancing Water Use Efficiency and Preventing Oxidative Stress. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 22507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallami, A.; Rachidi, F.; Lahsini, A.I.; El Khedri, H.; Douira, A.; El Modafar, C.; Medraoui, L.; Filali-Maltouf, A. Plant Growth Promoting (PGP) Performances and Diversity of Bacterial Species Isolated from Olive (Olea Europaea L.) Rhizosphere in Arid and Semi-Arid Regions of Morocco. J Pure Appl Microbiol 2023, 17, 2165–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malacrinò, A.; Mosca, S.; Li Destri Nicosia, M.G.; Agosteo, G.E.; Schena, L. Plant Genotype Shapes the Bacterial Microbiome of Fruits, Leaves, and Soil in Olive Plants. Plants 2022, 11, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vita, F.; Sabbatini, L.; Sillo, F.; Ghignone, S.; Vergine, M.; Guidi Nissim, W.; Fortunato, S.; Salzano, A.M.; Scaloni, A.; Luvisi, A.; et al. Salt Stress in Olive Tree Shapes Resident Endophytic Microbiota. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakagianni, M.; Tsiknia, M.; Feka, M.; Vasileiadis, S.; Leontidou, K.; Kavroulakis, N.; Karamanoli, K.; Karpouzas, D.G.; Ehaliotis, C.; Papadopoulou, K.K. Above- and below-Ground Microbiome in the Annual Developmental Cycle of Two Olive Tree Varieties. FEMS Microbes 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergine, M.; Vita, F.; Casati, P.; Passera, A.; Ricciardi, L.; Pavan, S.; Aprile, A.; Sabella, E.; De Bellis, L.; Luvisi, A. Characterization of the Olive Endophytic Community in Genotypes Displaying a Contrasting Response to Xylella Fastidiosa. BMC Plant Biol 2024, 24, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.T.; Krueger, R.R. The Date Palm (Phoenix Dactylifera L.): Overview of Biology, Uses, and Cultivation. HortScience 2007, 42, 1077–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Kruse, J.; Winkler, J.B.; Alfarray, S.; Schnitzler, J.-P.; Ache, P.; Hedrich, R.; Rennenberg, H. Climate and Development Modulate the Metabolome and Antioxidative System of Date Palm Leaves. J Exp Bot 2019, 70, 5959–5969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, L.; Kreuzwieser, J.; Kruse, J.; Zimmer, I.; Ache, P.; Alfarraj, S.; Al-Rasheid, K.A.S.; Schnitzler, J.-P.; Hedrich, R.; Rennenberg, H. Acclimation to Heat and Drought—Lessons to Learn from the Date Palm (Phoenix Dactylifera). Environ Exp Bot 2016, 125, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazzouri, K.M.; Flowers, J.M.; Nelson, D.; Lemansour, A.; Masmoudi, K.; Amiri, K.M.A. Prospects for the Study and Improvement of Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Date Palms in the Post-Genomics Era. Front Plant Sci 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, H.; Vikram, P.; Hammami, Z.; Singh, R.K. Recent Advances in Date Palm Genomics: A Comprehensive Review. Front Genet 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, N.; Tripathi, P.; Pandey, N.; Nakum, H.; Vala, Y.S. Advancements in Date Palm Genomics and Biotechnology Genomic Resources to the Precision Agriculture: A Comprehensive Review 2024.

- Yaish, M.W.; Patankar, H.V.; Assaha, D.V.M.; Zheng, Y.; Al-Yahyai, R.; Sunkar, R. Genome-Wide Expression Profiling in Leaves and Roots of Date Palm (Phoenix Dactylifera L.) Exposed to Salinity. BMC Genomics 2017, 18, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safronov, O.; Kreuzwieser, J.; Haberer, G.; Alyousif, M.S.; Schulze, W.; Al-Harbi, N.; Arab, L.; Ache, P.; Stempfl, T.; Kruse, J.; et al. Detecting Early Signs of Heat and Drought Stress in Phoenix Dactylifera (Date Palm). PLoS One 2017, 12, e0177883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekik, I.; Chaâbene, Z.; Kriaa, W.; Rorat, A.; Franck, V.; Hafedh, M.; Elleuch, A. Transcriptome Assembly and Abiotic Related Gene Expression Analysis of Date Palm Reveal Candidate Genes Involved in Response to Cadmium Stress. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology 2019, 225, 108569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Kruse, J.; Winkler, J.B.; Alfarraj, S.; Albasher, G.; Schnitzler, J.-P.; Ache, P.; Hedrich, R.; Rennenberg, H. Metabolic Responses of Date Palm ( Phoenix Dactylifera L.) Leaves to Drought Differ in Summer and Winter Climate. Tree Physiol 2021, 41, 1685–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, M.I.; Danish, S.; Naqvi, S.A.; Jaskani, M.J.; Asghar, M.A.; Khan, I.A.; Munir, M.; Muscolo, A. Physiological, Biochemical, and Comparative Genome Analysis of Salt and Drought Stress Impact on Date Palm (Phoenix Dactylifera L.): Tolerance Mechanism and Management. Plant Growth Regul 2024, 104, 1261–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordrostami, M.; Mafakheri, M.; Al-Khayri, J.M. Date Palm (Phoenix Dactylifera L.) Genetic Improvement via Biotechnological Approaches. Tree Genet Genomes 2022, 18, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaish, M.W.; Sunkar, R.; Zheng, Y.; Ji, B.; Al-Yahyai, R.; Farooq, S.A. A Genome-Wide Identification of the MiRNAome in Response to Salinity Stress in Date Palm (Phoenix Dactylifera L.). Front Plant Sci 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Amaresan, N.; Bhagat, S.; Madhuri, K.; Srivastava, R.C. Isolation and Characterization of Rhizobacteria Associated with Coastal Agricultural Ecosystem of Rhizosphere Soils of Cultivated Vegetable Crops. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2011, 27, 1625–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaish, M.W.; Al-Harrasi, I.; Alansari, A.S.; Al-Yahyai, R.; Glick, B.R. The Use of High Throughput DNA Sequence Analysis to Assess the Endophytic Microbiome of Date Palm Roots Grown under Different Levels of Salt Stress. Int Microbiol 2016, 19, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayyat, M.; Vazifeshenas, M.; Akbari, M. Pomegranate and Salt Stress Responses—Assimilation Activities and Chlorophyll Fluorescence Performances: A Review. Applied Fruit Science 2024, 66, 2455–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Zhang, X.; Yan, Y.; Wang, N.; Ge, W.; Zhou, Q.; Yang, Y. Unravelling the Molecular Mechanisms of Abscisic Acid-Mediated Drought-Stress Alleviation in Pomegranate (Punica Granatum L.). Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2020, 157, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiba, A.; Haddioui, A.; Hamdani, A.; Kettabi, Z.E.; Outghouliast, H.; Charafi, J. Impact of Contrasting Climate Conditions on Pomegranate Development and Productivity: Implications for Breeding and Cultivar Selection in Colder Environments. Vegetos 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, J.-S.; Chen, L.-Q.; Sosso, D.; Julius, B.T.; Lin, I.; Qu, X.-Q.; Braun, D.M.; Frommer, W.B. SWEETs, Transporters for Intracellular and Intercellular Sugar Translocation. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2015, 25, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZHAO, L.; YAO, J.; CHEN, W.; LI, Y.; LÜ, Y.; GUO, Y.; WANG, J.; YUAN, L.; LIU, Z.; ZHANG, Y. A Genome-Wide Analysis of SWEET Gene Family in Cotton and Their Expressions under Different Stresses. Journal of Cotton Research 2018, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.-Y.; Han, J.-X.; Han, X.-X.; Jiang, J. Genome-Wide Identification, Phylogeny, and Expression Analysis of the SWEET Gene Family in Tomato. Gene 2015, 573, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, S.K.; Reddy, K.R.; Li, J. Abscisic Acid and Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Crop Plants. Front Plant Sci 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterland, N.L.; Campbell, C.A.; Finer, J.J.; Jones, M.L. Abscisic Acid Application Enhances Drought Stress Tolerance in Bedding Plants. HortScience 2010, 45, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Hu, C.; Qi, X.; Chen, J.; Zhong, Y.; Muhammad, A.; Lin, M.; Fang, J. The AaCBF4-AaBAM3.1 Module Enhances Freezing Tolerance of Kiwifruit (Actinidia Arguta). Hortic Res 2021, 8, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravinath, R.; Das, A.J.; Usha, T.; Ramesh, N.; Middha, S.K. Targeted Metagenome Sequencing Reveals the Abundance of Planctomycetes and Bacteroidetes in the Rhizosphere of Pomegranate. Arch Microbiol 2022, 204, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, K.R.; Bolt, B.; Rodríguez López, C.M. Breeding for Beneficial Microbial Communities Using Epigenomics. Front Microbiol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwarari, D.; Radani, Y.; Ke, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, L. CRISPR/Cas Genome Editing in Plants: Mechanisms, Applications, and Overcoming Bottlenecks. Funct Integr Genomics 2024, 24, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, P.; Pal, S. CRISPR Genome Editing of Woody Trees: Current Status and Future Prospects. In CRISPRized Horticulture Crops; Elsevier, 2024; pp. 401–418. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).