1. Introduction

The loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta) is a pelagic species found in all the oceans of the temperate zone, including Mediterranean Sea [

1]. Several studies have documented the presence of nesting areas in Italy, along the coasts of Puglia, Basilicata, Campania, Calabria and Sicily [

2] but the only consistent nesting sites are the ’Pozzolana di Ponente’ beach on Linosa Island and the ’Spiaggia dei Conigli’ beach on Lampedusa Island [

3].

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) identified seven sea turtle species facing endangerment, with a specific focus on three species in the Mediterranean Sea classified as at risk of extinction. In particular, Caretta caretta appeared for the first time in 1975 in the category of the IUCN Red List of Italian Vertebrates as „critically endangered”. After over three decades of conservation initiatives, the Mediterranean loggerhead turtle sub-population has been designated as „Vulnerable” according to the latest assessment using the IUCN Red List criteria [

4]. Several studies have been carried out to ascertain the main causes of death during the life of these species [

5], but there is a lack of studies on the earlier stages, such as incubation and hatching. In fact, the loss of laid eggs results in the loss of a significant number of potential future adults already at risk of extinction. Nevertheless, this classification relies on conservation efforts, as substantial threats persist, including fishery bycatch, degradation of marine and terrestrial habitats, climate change, and marine pollution [

6]. In comparison with other Mediterranean nesting sites, Italian regions exhibit heightened human activities, including tourism, fishing, and marine traffic, all of which could potentially impact the utilization of coastal habitats by turtles [

7,

8]. These human-induced activities, combined with natural threats, may jeopardize various stages of sea turtle reproduction, including egg-laying, embryonic development, the occurrence of carapacial abnormalities, and the survival of hatchlings on the beach [

5]. For example, during the embryonic stages, the success of hatchlings may be compromised by a range of factors such as human disturbances, with a critical impact on the embryonic development, reducing hatchling success and leading to embryonic mortality [

9,

10,

11]. In recent years, the primary causes described for loggerhead turtles’ mortality are the sea turtle egg fusariosis (STEF) [

12,

13], organic pollutants contamination [

14] and microplastic ingestion [

15,

16]. In particular, STEF is a recently identified fungal disease associated with mortality in the eggs of endangered sea turtle nests on a global scale [

17]. Moreover, the rise in global temperatures as a result of climate change poses a threat to biodiversity worldwide [

18]. Non-avian reptiles are more vulnerable to heat stress during incubation due to the absence of parental care and limited behavioural thermoregulation [

19]. This has spurred increased research attention to comprehend the consequences of elevated nest temperatures on turtle development. Therefore, the purpose of this work is to evaluate the cause of death of unhatched Caretta caretta embryos from Pozzolana di Ponente beach on Linosa Island.

2. Materials and Methods

Samples collection

Forty-three unhatched loggerhead sea turtle eggs (Caretta caretta) were found on the beach of Pozzolana di Ponente on Linosa Island at the end of the summer season. A total of 5 unhatched nests were part of this study. In particular, the total number of eggs and the depth of eggs in the sand were recorded for each nest.

When the nest was opened, an external visual examination of the eggs was carried out, and they were subsequently opened for the extraction of the embryos. The samples were then fixed immediately by immersion in 10% buffered formalin (pH 7) to confer stability to the samples and inactivate the enzymes responsible for the autolytic processes. An initial selection was made on the specimens collected to exclude subjects clearly in a state of decomposition and therefore unsuitable for subsequent examinations. Fixed samples were sent to the Department of Veterinary Science, University of Turin.

Biometric data collection

For each sample, the following biometric data were recorded: standard carapace length (SCL) was measured from the midpoint of the nuchal plate to the caudal portion of the supracaudal scutes of the carapace; standard carapace width (SCW) was obtained by measuring the widest part of the carapace; head length (HL) was measured along the midline, from the posterior tip of the supra-occipital crest to the rostral part of the head (the rhaphotheca of the upper jaw); and head width (HW) was obtained by measuring the widest part of the head. These data were compared with Miller’s tables to evaluate age at death. [

20].

Gross and histological examination

After an external examination of each specimen to search for any lesions or alterations, a necropsy was performed on each turtle embryo following the procedures described by Wyneken [

21]. However, the protocol for necropsy was partly modified since the dissected specimens were small in size and still contained some embryonic structures, such as the yolk sac. After gross examination, organs (liver, stomach, intestine, heart, lungs, kidneys, and central nervous system) were paraffin-embedded according to routine histological procedures. Representative sections of each sample were stained with Haematoxylin-Eosin (HE), Grocott, Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS), von Kossa, and Movat pentachrome stain. All slides were observed using a Nikon Eclipse E600 light microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Electron microscopy

Paraffin-embedded kidney blocks were cut into small pieces and deparaffinized in Sub X (Leica Biosystems) for 48 h. Samples were retrimmed to pieces no larger than 1 mm, rehydrated in an ethanol series of descending concentrations, and washed in distilled water. Then they were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde (TAAB) in PBS pH 7.4 for 2 h at 4°C and post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide (OsO₄) (Next Chimica, South Africa) in PBS for 2 h at 4°C. The tissues were dehydrated through ascending grades of ethanol, incubated in propylene oxide (TAAB) for 5 min at room temperature, and embedded in Epon 812. Resin blocks were solidified at 60°C for 48 h. Semi-thin sections (1 µm) were cut and stained with 1% toluidine blue (w/v) pH 3.5. Silver-colored ultrathin sections (60-70 nm) were collected onto copper grids coated with a Formvar layer (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and double-stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Samples were examined using and photographed at 80 kV on a CM12 STEM electron microscope (Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands).

Temperature collection

Temperatures during July and August, when oviposition occurred and when the eggs should have hatched, on Linosa Island, from two years before to two years after the egg sampling, were monitored and recorded by the weather station on Lampedusa Island.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software version 4.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA). Fisher’s test was applied to evaluate the association between the depth at which the eggs were laid and the presence or absence of renal lesions.

The statistical significance of the association between the nests and the presence or absence of renal lesions was evaluated using the chi-square test. The Kruskal-Wallis test (nonparametric ANOVA) and the corresponding Dunn’s post-test were used to evaluate the differences in the distribution of average temperatures in the months of July and August over five consecutive years, using the year of deposition of the examined samples as the reference.

3. Results

Egg Depth Distributions and Biometric Data

The unhatched eggs were distributed in the sand at different depths, as reported in

Table 1.

Temperatures recorded in July and August, when oviposition occurred and when the eggs should have hatched, on Linosa Island, from two years before to two years after the egg sampling are summarized in

Table 2.

The biometric data showed that 17/43 (39.5%) animals had an SCL between 3.5 and 4.9 cm. These animals were classified as ready to hatch (also referred to as hatchlings) [

20], with an approximate range between the 28th and 30th days, corresponding to the very late stage of embryonic development.

All the remaining animals, 26/43 (60.5%), had SCL values between 2.3 cm and 3.5 cm and were accordingly classified as being in the last third of development (in the range between the 22nd and 27th days of development), according to Miller [

20].

Gross and Histological Examination

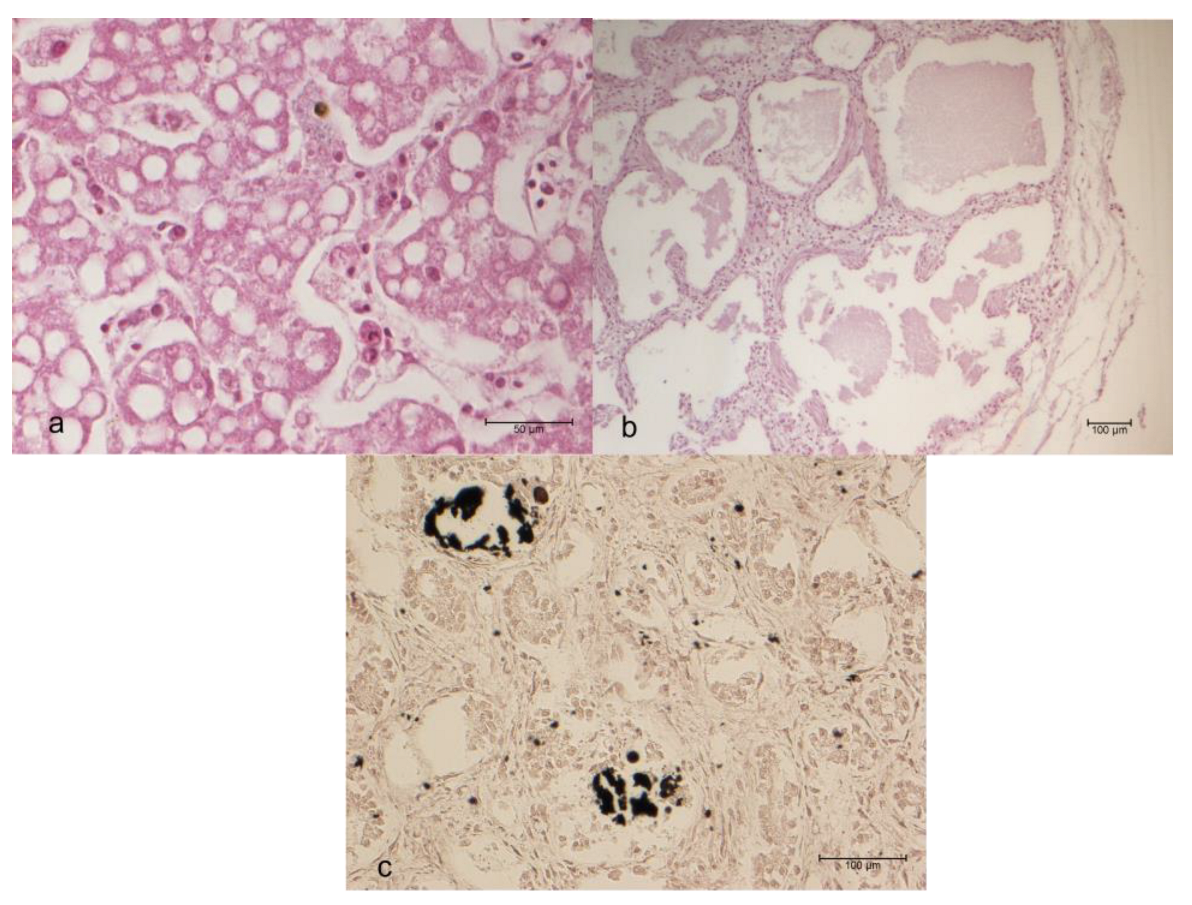

Histological examination of gonads and the central nervous system was not significant due to the heavy degree of autolysis. Stomach and intestine did not show any alterations. In 1/43 (2.3%) cases, a focal non-suppurative infiltration of the heart was observed. An increasing number of melanomacrophages (8/43 cases; 18.6%), haemorrhages (3/43 cases; 7.0%), and vacuolar degeneration (43/43 cases; 100%) were present in the liver (

Figure 1a). Oedema was observed in the lungs of 6/43 (14%) cases (

Figure 1b), and 25/43 (58.1%) animals showed glomerular and tubular calculosis, identified by von Kossa staining as calcium carbonate crystals, involving more than half of the renal parenchyma in 19 out of 25 (76%) animals (

Figure 1c).

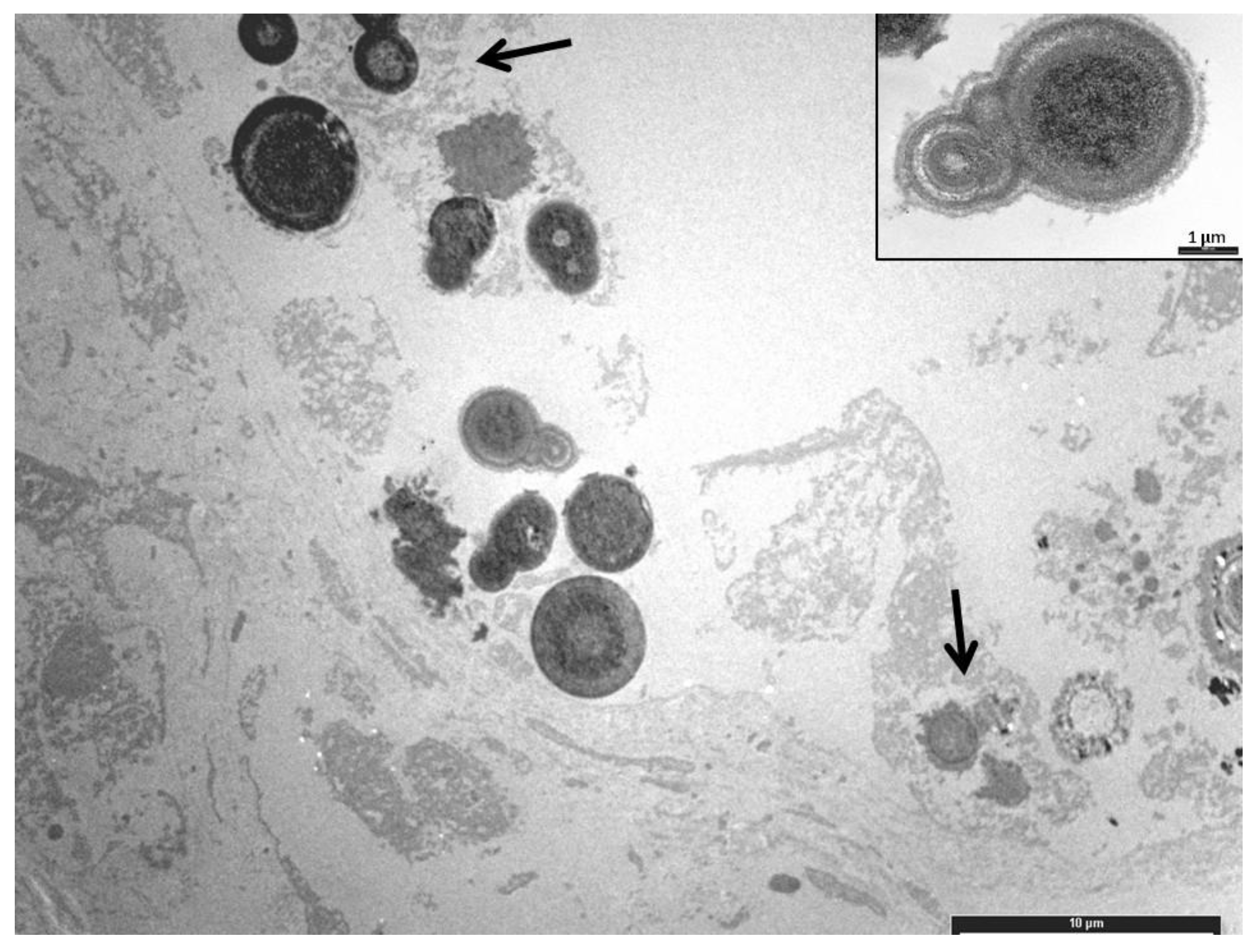

Electron Microscopy

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) revealed mineral deposits characterized by concentric, spherically shaped multilayered rings of crystals with alternating light and dark appearance, often embedded in an organic layer, consistent with calcium oxalate (

Figure 2).

Histochemical Staining

Grocott staining did not detect any fungal infection.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis revealed an association between nest position and renal calculosis (p<0.05) and between the differences in the average temperatures of July and August in the sampling year and the other years considered (p<0.001). No correlation was found between egg depth and kidney lesions.

4. Discussion

The most relevant findings in this study were observed in liver and kidney, primarily consisting of vacuolar degeneration of hepatocytes, increasing amount of melanomacrophages and renal calculosis.

The vacuolar lesions appear to be attributable to a chronic process, since the degeneration appears widespread and uniform throughout the parenchyma. These types of lesions have been previously observed for Caretta caretta in previous studies and are compatible with a pattern of toxicosis. Merendi and others [

22] have observed this degeneration in the liver of Caretta caretta stranded on the coast of Emilia Romagna; in that study it was hypothesized that the high concentration of arsenic in the liver, along with traces of other heavy metals, were responsible for the alterations. Moreover, Prearo and others [

23] observed that high concentrations of these substances were present in liver and kidneys of adult specimen of Caretta caretta. Further studies on the presence of persistent organic pollutants have been conducted: Storelli and Marcotrigiano [

24] have shown that the concentration of organo-chlorinated pesticides in the organs, particularly liver and kidneys, were higher in juveniles than in adults, while Alam and others [

25] described the presence of these substances in eggs of turtles. Environmental pollutants accumulated in female can play an important role during egg development of its eggs. Furthermore, sea turtles are animals at the top of the food chain, hence these substances can accumulate in the fatty tissue, before being transferred to the egg during its formation, as a result of the mobilization of the mother’s energy reserves [

26,

27]. Moreover, if the sand is further polluted, exposure to contaminants can continue after the deposition, through the gaseous exchanges occurring through the pores of the shell and the shell membranes [

28].

A further interesting result found in this study is the increase of melanomacrophages in 18.6% of liver samples. Factors that may contribute to the increase in number and/or size of these cells are represented by seasonal changes in temperature (as a defense mechanism in adaptive cold-blooded animals) [

29], weakness, wasting, stress, chronic inflammation and chronic diseases caused by bacteria [

30]. These data suggest that the increase in melanomacrophages could be due either to a physiological adaptive mechanism against exceptionally hot temperatures during the month of August, when the eggs were about to hatch, or to a defence mechanism against the exposure to toxic substances.

Kidneys showed in 58.1% of cases the deposition in the glomeruli and tubules of amorphous material, identified as crystals of calcium oxalate. It has been shown that in reptiles the most common causes of renal calculosis include dehydration [

31], excessive intake of protein and oxalate, vitamin and calcium deficiency, and bacterial infections [

32]. Considering that samples were represented by not hatched turtles, their metabolic energy is satisfied by the transfer of nutrients from the mother to the egg [

33]. The loggerhead turtle has an omnivorous-carnivorous diet, mainly based on the assumption of shellfishes, molluscs, and at a lesser extent algae [

34]. It is therefore unlikely that the renal oxalosis in embryos is due to the vertical transfer of food substances containing calcium oxalate. According to Ackerman [

35], the success of incubation for eggs of sea turtle depends on the presence of suitable conditions of temperature, humidity and salinity of the sand. Packard and Packard [

36] have demonstrated that a weight loss of more than 40% of the initial weight of the egg (for example due to dehydration), causes a considerable risk for the successful hatching. An analysis of environmental temperatures recorded in the months of July and August (

Table 2), in which the eggs were laid, revealed that the average temperature was statistically higher than the previous two and the next two years. Moran and others [

37] observed that the critical temperature of the sand beyond which the eggs of Caretta caretta do not hatch is 32.4°C. The sand temperature depends both on the environmental temperature and on its colour. Inasmuch, as the sand of the Pozzolana di Ponente beach is very dark, being of volcanic origin, a great heat radiation and a high nest temperature are present. The temperature of the sand around the nest also increases in the last stage of embryonic development, following the increases of the metabolic rate of the embryos [

38]. Considering that 39.5% of the samples analyzed were hatchlings, while the remaining were in the last stage of incubation, and renal oxalosis can result from dehydration, it can be speculated that the renal alterations were caused by the loss of water from the eggs, due to the abnormally high environmental temperatures.

5. Conclusions

So far, discussions on the effects of global warming on sea turtle populations have primarily focused on the loss of egg-laying sites due to rising sea levels and tides, as well as alterations in sex ratios caused by the resulting increase in sand and nest temperatures [

39]. In summary, climate change and human-induced impacts are considered among the most significant threats to the well-being of sea turtles, and should therefore be prioritized in research and conservation management efforts. Furthermore, identifying potential pathogens that pose a threat to endangered sea turtle species, influenced by both global warming and human activities, is essential for developing effective conservation strategies. The findings of this study may indicate a potential threat to loggerhead sea turtle nesting areas in the Mediterranean basin, a phenomenon likely linked to global warming.

Since the loggerhead sea turtle is an endangered species and Linosa is a crucial site in the Mediterranean for the birth of nearly all female individuals, more detailed studies are necessary to assess the critical temperature for successful hatching. Therefore, preventive measures should be implemented to protect the nests. Additional research on sand pollution and its toxicity to the turtles is also needed to identify corrective and protective actions to safeguard nesting sea turtles in the Mediterranean Sea.

Author Contributions

FES was the mentor and principal advisor and proposed the concept of the study, EB, EL and MC performed histological examination and diagnosis, EM performed electron microscopy, PP performed statistical analysis, DZ, SA performed sampling and monitoring of the nests, SN, ADL, MP, MG performed laboratory analysis, FRS, PP, MC were involved in the drafting and writing of the manuscript. All authors have read, commented and approved the final article.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

the datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories, accessible under request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IUCN |

International Union for Conservation of Nature |

| SCL |

Standard carapace length |

| SCW |

standard carapace width |

| HL |

head length |

| HW |

head width |

| HE |

Haematoxylin-Eosin stain |

| PAS |

Periodic Acid Schiff |

| TEM |

Transmission Electron Microscopy |

References

- Pritchard, P.; Mortimer, J. Taxonomy, External Morphology, and Species Identification. In Research and management techniques for the conservation of sea turtles.; SSC/IUCNN marine turtle specialist group.: Gland, 1999; pp. 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mingozzi, T.; Masciari, G.; Paolillo, G.; Pisani, B.; Russo, M.; Massolo, A. Discovery of a Regular Nesting Area of Loggerhead Turtle Caretta Caretta in Southern Italy: A New Perspective for National Conservation. 2006; 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balletto, E.; Giacoma, C.; Paolillo, G.; Mari, F.; Dell’Anna, L. Piano d’azione per La Conservazione Della Tartaruga Marina Caretta Caretta Nelle Isole Pelagie. In; Edi. Tur. S.r.l.: Roma, 2003; pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Casale, P. Caretta Caretta (Mediterranean Subpopulation); IUCN Red List of Threatened Species Available online:. Available online: https://www.iucn.it/scheda.php?id=1108177324 (accessed on 7 December 2023).

- Casale, P. Sea Turtles in the Mediterranean : Distribution, Threats and Conservation Priorities; IUCN, 2010; ISBN 978-2-8317-1240-6.

- Casale, P.; Broderick, A.C.; Camiñas, J.A.; Cardona, L.; Carreras, C.; Demetropoulos, A.; Fuller, W.J.; Godley, B.J.; Hochscheid, S.; Kaska, Y.; et al. Mediterranean Sea Turtles: Current Knowledge and Priorities for Conservation and Research. Endangered Species Research 2018, 36, 229–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depellegrin, D.; Menegon, S.; Farella, G.; Ghezzo, M.; Gissi, E.; Sarretta, A.; Venier, C.; Barbanti, A. Multi-Objective Spatial Tools to Inform Maritime Spatial Planning in the Adriatic Sea. Science of The Total Environment 2017, 609, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachogianni, T.; Fortibuoni, T.; Ronchi, F.; Zeri, C.; Mazziotti, C.; Tutman, P.; Varezić, D.B.; Palatinus, A.; Trdan, Š.; Peterlin, M.; et al. Marine Litter on the Beaches of the Adriatic and Ionian Seas: An Assessment of Their Abundance, Composition and Sources. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2018, 131, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoro, M.; Hernández, G.; Caballero, M.; García, F. AEROBIC BACTERIAL FLORA OF NESTING GREEN TURTLES (CHELONIA MYDAS) FROM TORTUGUERO NATIONAL PARK, COSTA RICA. zamd 2006, 37, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durmuş, S.H.; Ilgaz, Ç.; Gü çlü, Ö.; Özdemir, A. The Effect of the Predicted Air Temperature Change on Incubation Temperature, Incubation Duration, Sex Ratio and Hatching Success of Loggerhead Turtles. Animal Biology 2011, 61, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caracappa, S.; Persichetti, M.F.; Piazza, A.; Caracappa, G.; Gentile, A.; Marineo, S.; Crucitti, D.; Arculeo, M. Incidental Catch of Loggerhead Sea Turtles (Caretta Caretta) along the Sicilian Coasts by Longline Fishery. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleason, F.H.; Allerstorfer, M.; Lilje, O. Newly Emerging Diseases of Marine Turtles, Especially Sea Turtle Egg Fusariosis (SEFT), Caused by Species in the Fusarium Solani Complex (FSSC). Mycology 2020, 11, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risoli, S.; Sarrocco, S.; Terracciano, G.; Papetti, L.; Baroncelli, R.; Nali, C. Isolation and Characterization of Fusarium Spp. From Unhatched Eggs of Caretta Caretta in Tuscany (Italy). Fungal Biology 2023, 127, 1321–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Canzanella, S.; Iaccarino, D.; Pepe, A.; Di Nocera, F.; Bruno, T.; Marigliano, L.; Sansone, D.; Hochscheid, S.; Gallo, P.; et al. Trace Elements and Persistent Organic Pollutants in Unhatched Loggerhead Turtle Eggs from an Emerging Nesting Site along the Southwestern Coasts of Italy, Western Mediterranean Sea. Animals 2023, 13, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemello, G.; Trotta, E.; Notarstefano, V.; Papetti, L.; Di Renzo, L.; Matiddi, M.; Silvestri, C.; Carnevali, O.; Gioacchini, G. Microplastics Evidence in Yolk and Liver of Loggerhead Sea Turtles (Caretta Caretta), a Pilot Study. Environmental Pollution 2023, 337, 122589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, E.M.; Broderick, A.C.; Fuller, W.J.; Galloway, T.S.; Godfrey, M.H.; Hamann, M.; Limpus, C.J.; Lindeque, P.K.; Mayes, A.G.; Omeyer, L.C.M.; et al. Microplastic Ingestion Ubiquitous in Marine Turtles. Global Change Biology 2019, 25, 744–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietroluongo, G.; Centelleghe, C.; Sciancalepore, G.; Ceolotto, L.; Danesi, P.; Pedrotti, D.; Mazzariol, S. Environmental and Pathological Factors Affecting the Hatching Success of the Two Northernmost Loggerhead Sea Turtle (Caretta Caretta) Nests. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.P.; Allen, C.D.; Eguchi, T.; Bell, I.P.; LaCasella, E.L.; Hilton, W.A.; Hof, C.A.M.; Dutton, P.H. Environmental Warming and Feminization of One of the Largest Sea Turtle Populations in the World. Current Biology 2018, 28, 154–159e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.M.; Sun, B. Heat Tolerance of Reptile Embryos: Current Knowledge, Methodological Considerations, and Future Directions. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part A: Ecological and Integrative Physiology 2021, 335, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.D.; Mortimer, J.A.; Limpus, C.J. A Field Key to the Developmental Stages of Marine Turtles (Cheloniidae) with Notes on the Development of Dermochelys. ccab 2017, 16, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyneken, J. The Anatomy of Sea Turtles; Technical Memorandum.; Department of Commerce, NOAA, U.S.: Miami (FL), 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Merendi, F.; Zaccaroni, A.; Zucchini, M.; Affronte, M.; Scaravelli, D.; Simoni, P. Rilievi Necroscopici, Esami Citologici, Istologici e Determinazione Dei Metalli Pesanti e Arsenico in Tartarughe Marine (Caretta Caretta) Spiaggiate in Emilia Romagna. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1th annual congress of the Italian association of pathologists.

- Prearo, M.; Squadrone, S.; Tarasco, R.; Zizzo, N.; Appino, S.; Pavoletti, E.; Abete, M. Presenza Di Metalli Pesanti in Tartarughe Comuni (Caretta Caretta) Spiaggiate Lungo Le Coste Pugliesi. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 11th annual congress of Italian Society of Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory.

- Storelli, M.M.; Marcotrigiano, G.O. Chlorobiphenyls, HCB, and Organochlorine Pesticides in Some Tissues of Caretta Caretta (Linnaeus) Specimens Beached along the Adriatic Sea, Italy. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 2000, 64, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.K.; Brim, M.S. Organochlorine, PCB, PAH, and Metal Concentrations in Eggs of Loggerhead Sea Turtles (Caretta Caretta) from Northwest Florida, USA. J Environ Sci Health B 2000, 35, 705–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Merwe, J.P.; Hodge, M.; Whittier, J.M.; Ibrahim, K.; Lee, S.Y. Persistent Organic Pollutants in the Green Sea Turtle <em>Chelonia Mydas</Em>: Nesting Population Variation, Maternal Transfer, and Effects on Development. Marine Ecology Progress Series 2010, 403, 269–278. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, K.R.; Keller, J.M.; Templeton, R.; Kucklick, J.R.; Johnson, C. Monitoring Persistent Organic Pollutants in Leatherback Turtles (Dermochelys Coriacea) Confirms Maternal Transfer. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2011, 62, 1396–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañas, J.E.; Anderson, T.A. Organochlorine Contaminants in Eggs: The Influence of Contaminated Nest Material. Chemosphere 2002, 47, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.C.; Schwiesow, T.; Ekwall, A.K.; Christiansen, J.L. Reptilian Melanomacrophages Function under Conditions of Hypothermia: Observations on Phagocytic Behavior. Pigment Cell Research 1999, 12, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agius, C.; Roberts, R.J. Melano-Macrophage Centres and Their Role in Fish Pathology. Journal of Fish Diseases 2003, 26, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mader, D. Reptile Medicine and Surgery. In; Saunders Elsevier: Philadelphia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Frye, F. Biomedical and Surgical Aspects of Captive Reptile Husbandry.; Krieger publishing company.: Malabar, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J. Embryology of Marine Turtles. In Biology of the reptilia.; Wiley-Interscience: Hoboken, 1985; pp. 269–328. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, P.; Musick, J.; Wyneken, J. The Biology of Sea Turtles.; Crc press: London, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman, R. The Nest Environment and the Embryonic Development of Sea Turtles. In The biology of sea turtles.; Crc press: London, 1997; pp. 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- Packard, G.; Packard, M. The Physiological Ecology of Reptilian Eggs and Embryos. In Biology of the reptilia.; Academic press.: Cambridge, 1988; pp. 523–605. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, K.; Bjorndal, K.; Bolten, A. Effects of the Thermal Environment on the Temporal Pattern of Emergence of Hatchling Loggerhead Turtles Caretta Caretta. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1999, 189, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzawa, Y.; Sato, K.; Sakamoto, W.; Bjorndal, K. Seasonal Fluctuations in Sand Temperature: Effects on the Incubation Period and Mortality of Loggerhead Sea Turtle (Caretta Caretta) Pre-Emergent Hatchlings in Minabe, Japan. Marine Biology 2002, 140, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, J. Temperature and the Life-History Strategies of Sea Turtles. Journal of Thermal Biology 1997, 22, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).