1. Introduction

Blockchain technology, introduced with Bitcoin in 2008, has revolutionized digital transactions and trust systems. At its core, blockchain is a decentralized, immutable ledger that eliminates the need for central authorities to manage and validate transactions. The launch of Ethereum in 2013 marked a significant evolution with the introduction of smart contracts—self-executing agreements with predefined rules encoded into the blockchain. These innovations enabled the creation of decentralized applications (dApps), which operate across a network of computers, offering a more secure, transparent, and trustless ecosystem for various applications.

As blockchain matures, its potential applications have expanded beyond cryptocurrency, finding promising use cases in real-world processes such as property management and dispute resolution. Traditional rental agreements often suffer from a lack of transparency, inefficient processes, and power imbalances between landlords and tenants. Common issues, such as disputes over security deposits, maintenance responsibilities, and lease violations, frequently lead to costly and time-consuming legal proceedings, often skewed in favor of the party with more resources.

To address these challenges, this paper introduces the Decentralized Rental Agreement and Dispute Resolution (DRADR) model. By leveraging blockchain technology, smart contracts, and decentralized justice systems, the DRADR model aims to create a more equitable, efficient, and transparent rental system. It automates key rental processes, ensures unchangeable records of agreements and transactions, and offers impartial, accessible methods for resolving disputes. This research provides a detailed analysis of the DRADR framework, including the development of smart contracts, a theoretical evaluation using game theory, and a case study-based analysis of its effectiveness.

The main contributions of this paper are the introduction of a blockchain-based rental agreement model that addresses power imbalances, integrates decentralized justice systems like Kleros, and offers insights into the potential regulatory impact on the rental market. By tackling these challenges, the DRADR model promotes broader acceptance and trust in blockchain-based solutions for everyday transactions.

The paper structure begins with an introduction followed by several sections: basic concepts, literature review and related works, system architecture and rental agreement management algorithms, methodology addressing key questions and analysis, experimental results, an in-depth discussion of findings, and a conclusion summarizing discussed ideas and outlining future work.

2. Literature Review

This paper establishes the theoretical background by summarizing the definitions of key concepts within our research domain. The purpose of the literature review is to assess the state of the art in the research focus under investigation and to survey the contributions of existing literature to our topic.

The literature review aims to outline existing knowledge in the research field and highlight the milestones that constitute research directions. Specifically, it demonstrates the progress made by researchers in the same topic, examines their findings, and identifies any gaps in the field [

1] in it. In our research, we aim to shed light on the term "Blockchain" and investigate some fundamental concepts related to rental markets

2.1. Blockchain History and Definition

The core ideas behind blockchain technology [

2]date back to the late 1980s and early 1990s, but its potential as a foundational technology for global record-keeping systems began to be realized only recently. Blockchain was formally introduced in 2008 by the pseudonymous Satoshi Nakamoto in [

3]. This paper laid the groundwork for the Bitcoin cryptocurrency and its accompanying blockchain network, launched in 2009 [

4].

The Bitcoin blockchain was a permissionless network, enabling users to create accounts and transact anonymously. This innovation established trust between parties without prior relationships, facilitating faster and lower-cost transactions. In contrast, permissioned blockchain networks where access is more controlled—focus on enhancing trust among known users [

5].

Blockchain’s decentralized architecture stores its general ledger in a peer-to-peer manner, requiring changes to propagate to most ledger holders. Bitcoin not only revolutionized digital currency, but also brought blockchain technology into the spotlight, showcasing its potential for secure, transparent, and tamper-proof record-keeping.

Taking into consideration various references,There are several perspectives on defining the concept of Blockchain.The authors in [

6] defined blockchain as :

Definition 1. The term Blockchain is not coincidental: the digital ledger is often described as a chain composed of individual data blocks.As new data is regularly added to the network, a new block is created and appended to the chain. This process requires all nodes in the network to update their versions of the blockchain ledger to maintain consistency.

The method by which these new blocks are generated is fundamental to understanding why blockchain is considered highly secure. Before a new block can be added to the ledger, a majority of nodes must verify and validate the authenticity of the new data. This process may involve using a cryptocurrency to ensure that the transactions in the new block are not fraudulent or that coins are not spent multiple times. This decentralized validation process contrasts with standalone databases or spreadsheets, where changes can be made by a single individual without oversight.[6]

Another definition from [

7] mentioned that:

Definition 2. A blockchain can be considered a digitalized public ledger that records all digital transactions in chronological order, referred to as “Completed Transaction Blocks” as a data structure, and stores this in a distributed manner across a network. This ledger is accessible to anyone who can connect to the network.

lockchain is a technology that creates a chain of blocks, each containing a record of multiple transactions linked together using cryptography. Once a block is added to the blockchain, its data cannot be altered, making blockchain an ideal platform for storing and sharing sensitive information.

A key feature of blockchain technology is its decentralized nature, meaning it is not controlled by any single entity or organization. Instead, it relies on a network of computers (known as nodes) to validate and record transactions. This decentralized structure makes blockchain highly resistant to fraud and tampering, as any changes must be verified by the majority of the network’s nodes before being implemented.

2.2. Blockchain Technologies

Blockchain technology can be defined as a distributed ledger that stores multiple transactions in a chain of blocks through a process of reading, validating, and storing data within the chain. This mechanism is based on a peer-to-peer topology, which eliminates the need for third-party intermediaries by leveraging a large, decentralized network that is securely connected. Every transaction is protected by the owner’s signature, making it traceable throughout its path.

Definition 3. Blockchain technology can be defined as a distributed ledger that stores several transactions in a chain of blocks through a reading, validating, and storing process in a block of the chain. This mechanism is based on peer-to-peer topology which removes the third-factor party from the transactions via a huge, decentralized network connected to each other securely. Every transaction is protected by the signature of the owner, and it can be traceable during the path it went through.

Blockchain is a technology [

8] that creates a chain of blocks, each containing a record of multiple transactions linked together using cryptography. Once a block is added to the blockchain, the data within it cannot be altered, making blockchain an ideal platform for storing and sharing sensitive information.

One of the key features of blockchain technology is its decentralized nature, meaning it is not controlled by any single entity or organization. Instead, it relies on a network of computers (known as nodes) to validate and record transactions. This decentralized structure makes it highly resistant to fraud and tampering, as any changes to the blockchain must be verified by the majority of the network’s nodes before they can be implemented. The classification of blockchain types is mentioned in the table below

Table 1:

Table 1.

Comparison-of-public-consortium-and-private-blockchains

Table 1.

Comparison-of-public-consortium-and-private-blockchains

| Property |

Public Blockchain |

Consortium Blockchain |

Private Blockchain |

| Consensus Determination |

All miners |

Selected set of nodes |

One organization |

| Read permission |

Public |

May be public or restricted |

May be public or restricted |

| Immutability |

Almost Completely tamper-proof |

Potential For tampering |

Potential For tampering |

| Efficiency |

Low |

Height |

Height |

| Centralized |

No |

Partial |

Yes |

| Consensus process |

Permissionedless |

Permissioned |

Permissioned |

A detailed consideration of the various referenced definitions is excluded from the scope of this paper.

3. Overview of Blockchain Platforms in Rental Markets

Blockchain platforms [

9] re increasingly being explored for their potential to revolutionize rental markets by introducing transparency, efficiency, and trust [

10]. Blockchain technology is being applied in rental markets, and the following are the most commonly used applications in this domain:

Smart Contracts: Blockchain-based smart contracts [

11] enable the automatic execution of rental agreements when predefined conditions are met, eliminating the need for intermediaries such as real estate agents. This reduces transaction costs and minimizes disputes.

Decentralization: Blockchain facilitates peer-to-peer (P2P) rental platforms, allowing property owners and tenants to connect directly without relying on centralized entities.

Tokenization: Property ownership or rental rights can be tokenized, enabling fractional ownership and simplifying the transfer of rental agreeme

Several blockchain platforms are emerging as key players in the rental sector, leveraging smart contracts, tokenization, and decentralized applications (dApps) to streamline rental processes, enhance security, and reduce reliance on intermediaries. Among the most popular platforms, Ethereum stands out for its extensive use of smart contracts, while others, such as Propy, ManageGo, BeeToken, and RealT, are introducing innovative solutions to various aspects of rental transactions. These platforms demonstrate how blockchain can simplify rental agreements, automate payments, and ensure transparency, paving the way for a more efficient and trustworthy rental ecosystem. Each of these platforms is contributing to the transformation of the rental market through unique use cases and technological features.

Ethereum: is the most widely used platform for smart contracts and decentralized applications (dApps), making it ideal for rental markets, as use Case: Ethereum-based rental platforms [

12] allow property owners to create digital rental contracts, automate rent payments, and securely record rental history.

Propy: is a platform that offers decentralized title registry services and facilitates real estate transactions globally. as a use case: While Propy primarily focuses on real estate sales, its smart contracts and decentralized registries can be extended to rental markets, providing secure and transparent rental agreements. It can also be adapted for leasing to ensure transparency.

Blockchain-Based Property Management Platforms: [

13] Platforms like

ManageGo integrate blockchain with property management tools. as a use case: Using blockchain technology, rental payments and tenant management are made transparent and secure. This ensures that landlords can verify payment histories while tenants can track their rental status.

BeeToken: BeeToken aimed to decentralize the short-term housing rental market, similar to Airbnb, by using blockchain to eliminate middlemen. as a use case : BeeToken leveraged Ethereum to enable direct interaction between hosts and guests, secure payments through cryptocurrency, and enforce agreements through smart contracts.

RealT: RealT [

14] allows individuals to invest in fractions of rental properties and receive rental income in cryptocurrency. **Use Case**: By purchasing tokens representing partial ownership of a rental property, individuals can earn a share of the rent while the blockchain transparently tracks income and payouts.

4. Related works

From several references and deep research about the domain, we conclude the

Table 2 below that shows various research works and summaries the various references related to our topic:

Table 2.

Related works.

| Reference |

Idea |

Comments |

| Blockchain in Real Estate [15] |

Explores blockchain’s potential in automating real estate transactions. |

Relevant for automation and transparency in DRADR. |

| Smart Contracts for Dispute Resolution [16] |

Discusses smart contracts in resolving disputes. |

Useful for integrating decentralized justice mechanisms. |

| Ethereum-Based dApps [17] |

Evaluates Ethereum for real estate decentralization. |

Offers insights into DRADR technical implementation. |

| Game Theory and Blockchain [18] |

Analyzes blockchain models using game theory. |

Applicable to DRADR’s strategic dynamics. |

| Blockchain Dispute Resolution Platforms [19] |

Examines legal challenges in blockchain-enabled dispute systems. |

Key for DRADR’s compliance. |

| Kleros Case Study [20] |

Insights into decentralized justice with Kleros. |

Relevant for the DRADR justice mechanism. |

| Tokenization of Real Estate [21] |

Explores tokenization of properties for rental management. |

Useful for fractional ownership in DRADR. |

| Blockchain Regulation [22] |

Discusses regulatory frameworks for decentralized markets. |

Guides DRADR’s compliance strategy. |

| DeFi in Rental Markets [23] |

Investigates DeFi for rental agreements and payments. |

Adds DeFi perspectives to DRADR. |

The reviewed literature presents a broad spectrum of applications for blockchain technology in the real estate and rental sectors, aligning well with the core principles of the Decentralized Rental Agreement and Dispute Resolution (DRADR) model. Research highlights how blockchain can address long-standing challenges in traditional rental markets, including transparency, security, and the reduction of intermediaries. In particular, smart contracts and decentralized finance (DeFi) solutions are integral to automating rental agreements, minimizing disputes, and enabling more efficient and transparent transactions [

24].

Several studies, such as those exploring Ethereum-based decentralized applications (dApps), offer valuable insights into the technical implementation of blockchain in rental markets, demonstrating the feasibility of applying blockchain to rental agreements [

25]. Furthermore, research on smart contracts for dispute resolution [

26] provides a clear understanding of how blockchain technology can streamline the dispute resolution process by creating immutable records and reducing reliance on legal intermediaries. Platforms like Kleros, which offer decentralized justice, exemplify DRADR’s dispute resolution mechanism, ensuring fairness and impartiality.

The incorporation of game theory into blockchain models offers strategic insights essential for evaluating the potential risks and rewards in decentralized systems like DRADR. By examining equilibrium and payoff comparisons, game theory helps assess the optimal behaviors of different stakeholders involved in rental agreements.

In summary, existing research confirms that blockchain has the potential to revolutionize the rental market by offering solutions to inefficiencies and inequalities present in traditional systems. The insights gathered from these studies will guide the refinement and implementation of the DRADR model, helping it achieve its goal of creating a more equitable, transparent, and efficient rental ecosystem.

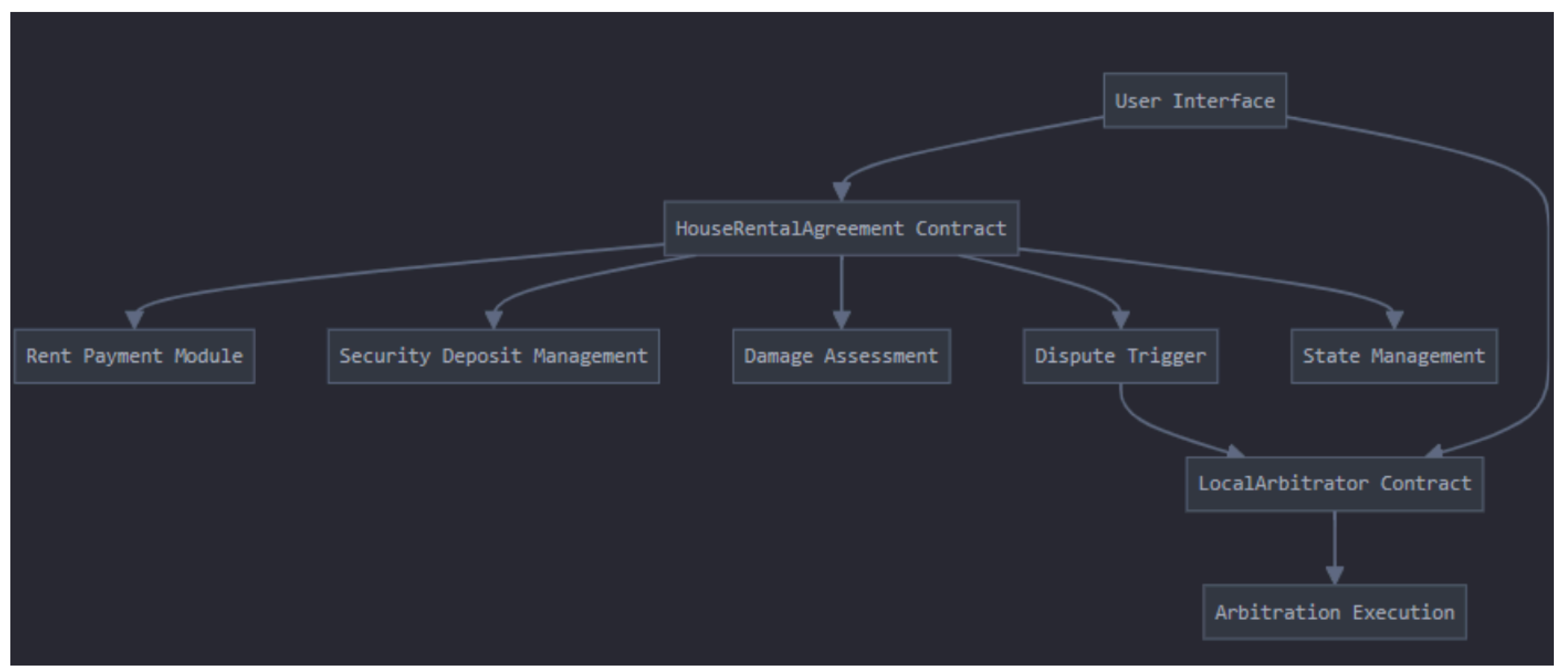

5. System Architecture

The system architecture is designed to ensure seamless interaction among components, providing a comprehensive solution for managing rental agreements and resolving disputes in a decentralized manner. Below is an overview of its key components:

Rental Agreement Management: This component manages the entire lifecycle of rental agreements, including rent payments, security deposits, damage claims, dispute creation, and the execution of rulings.

Arbitration System:The arbitration system oversees the processes for creating and resolving disputes. It ensures that disagreements are addressed systematically and impartially.

Figure 1.

High-level overview of the system components.

Figure 1.

High-level overview of the system components.

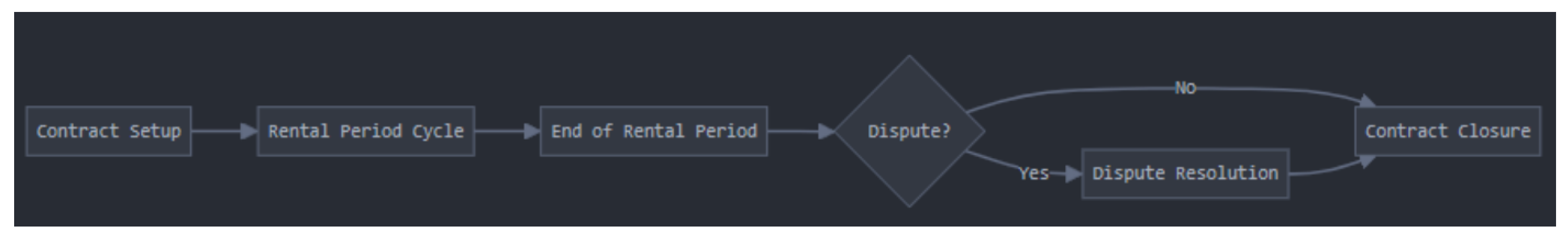

Figure 2.

Overview of House Rental System Based on DRADR Model.

Figure 2.

Overview of House Rental System Based on DRADR Model.

5.1. Rental Agreement Management Algorithms

This algorithm is activated when disputes arise regarding damage assessments at the end of a tenancy. It allows tenants to formally challenge a landlord’s damage estimate, providing a structured and fair process for resolving one of the most common sources of conflict in rental agreements. As noted by Oliveira [

27], arbitration mechanisms are critical in resolving disputes within smart contract frameworks, particularly in cross-border settings, where they ensure transparency, impartiality, and efficiency. The algorithm ensures financial viability by verifying that the security deposit covers arbitration costs, reflecting principles of fairness and dispute resolution highlighted in the literature.

Executing Arbitrator Ruling Algorithm This algorithm automatically enforces an arbitrator’s decision, ensuring the security deposit is distributed fairly based on the ruling. It eliminates manual intervention, reduces potential disputes, and incentivizes fair arbitration practices by refunding part of the arbitration cost to the winning party.

Arbitration System Algorithms The Arbitration System Algorithms play a critical role in resolving disputes effectively and transparently. When a dispute is formally raised, the system creates a comprehensive record of the disagreement, starting with the Creating a Dispute algorithm.

Creating a Dispute Algorithm This algorithm initializes and records disputes in a detailed and immutable manner. It captures both landlord and tenant estimates, assigns a unique identifier to each dispute, and prepares all relevant information for the arbitrator.

Resolving a Dispute Algorithm This algorithm swiftly and fairly implements the arbitrator’s decision, maintaining the integrity of the arbitration process by verifying the arbitrator’s authority and preventing duplicate resolutions. It bridges decision-making and execution, ensuring disputes are resolved efficiently.

5.2. Security Considerations

The reliability and trustworthiness of the DRADR system are underpinned by robust security mechanisms. While the algorithms form the functional core of the DRADR system, its overall dependability heavily relies on the implementation of security measures that ensure system integrity and fairness. As highlighted in recent research on decentralized dispute resolution mechanisms, such as [

27], these measures are crucial for maintaining transparency and security in blockchain-based systems.

Access Control: Restricts specific functions to authorized roles (e.g., landlords, tenants, or arbitrators) to maintain system integrity and fairness.

Fund Management: Implements a withdrawal pattern to prevent vulnerabilities such as re-entrance attacks, ensuring secure financial transactions.

State Management: Ensures actions occur only in the appropriate agreement state, avoiding inconsistencies or exploits.

Gas Efficiency: Optimizes blockchain operations by estimating gas requirements and setting limits, minimizing the risk of incomplete transactions during complex processes like dispute resolution.

These algorithms and mechanisms collectively ensure that the system operates efficiently, securely, and equitably for all parties involved in rental agreements..

6. Methodology

Our research methodology was designed to address three key questions that emerged from our analysis of the current challenges in rental markets and the potential of blockchain technology to address these issues. These research questions stemmed from a comprehensive review of existing literature on rental market inefficiencies, blockchain applications in real estate, and game-theoretic analyses of contractual relationships. We identified gaps in current research, particularly concerning the application of decentralized technologies to rental agreements and dispute resolution.

-

RQ1:

How does the integration of DeFi principles into a blockchain-based rental agreement system affect the efficiency and fairness of the rental process?

-

RQ2:

How does the implementation of a blockchain-based rental system alter the game-theoretic dynamics between landlords and tenants, particularly in security deposit disputes?

-

RQ3:

To what extent can a blockchain-based rental agreement system mitigate the power imbalances inherent in traditional landlord-tenant relationships?

To answer these questions and comprehensively evaluate the potential impact and efficacy of the DRADR model, we employed a multi-faceted approach that combines theoretical analysis, game-theoretic modeling, and empirical investigation.

We began our evaluation by applying the DRADR model to three landmark legal cases in rental disputes [

28], Arnold v Britton & Others

1 and Youssefi v Musselwhite/Horne & Meredith Properties v Cox and Billingsley [2014] EWCA Civ 423

2

For each case, we conducted a detailed analysis comparing how the DRADR model might have addressed the issues differently from traditional methods. Our comparison focused on five key aspects: efficiency, fairness, dispute prevention, transparency, and record-keeping. This analysis enabled us to explore the potential real-world applications and benefits of the DRADR model in complex legal scenarios.

6.1. Game-Theoretic Model Analysis

To understand the strategic implications of the DRADR model, we developed game-theoretic models for both traditional rental agreements and the DRADR model. These models included:

Player strategies for landlords and tenants.

Payoff matrices for different scenarios.

Analysis of Nash equilibria.

By comparing these models, we were able to assess how the DRADR system alters the strategic dynamics between landlords and tenants. This analysis provided insights into how the incentive structures embedded in the DRADR model could potentially lead to more equitable and efficient outcomes in rental relationships.

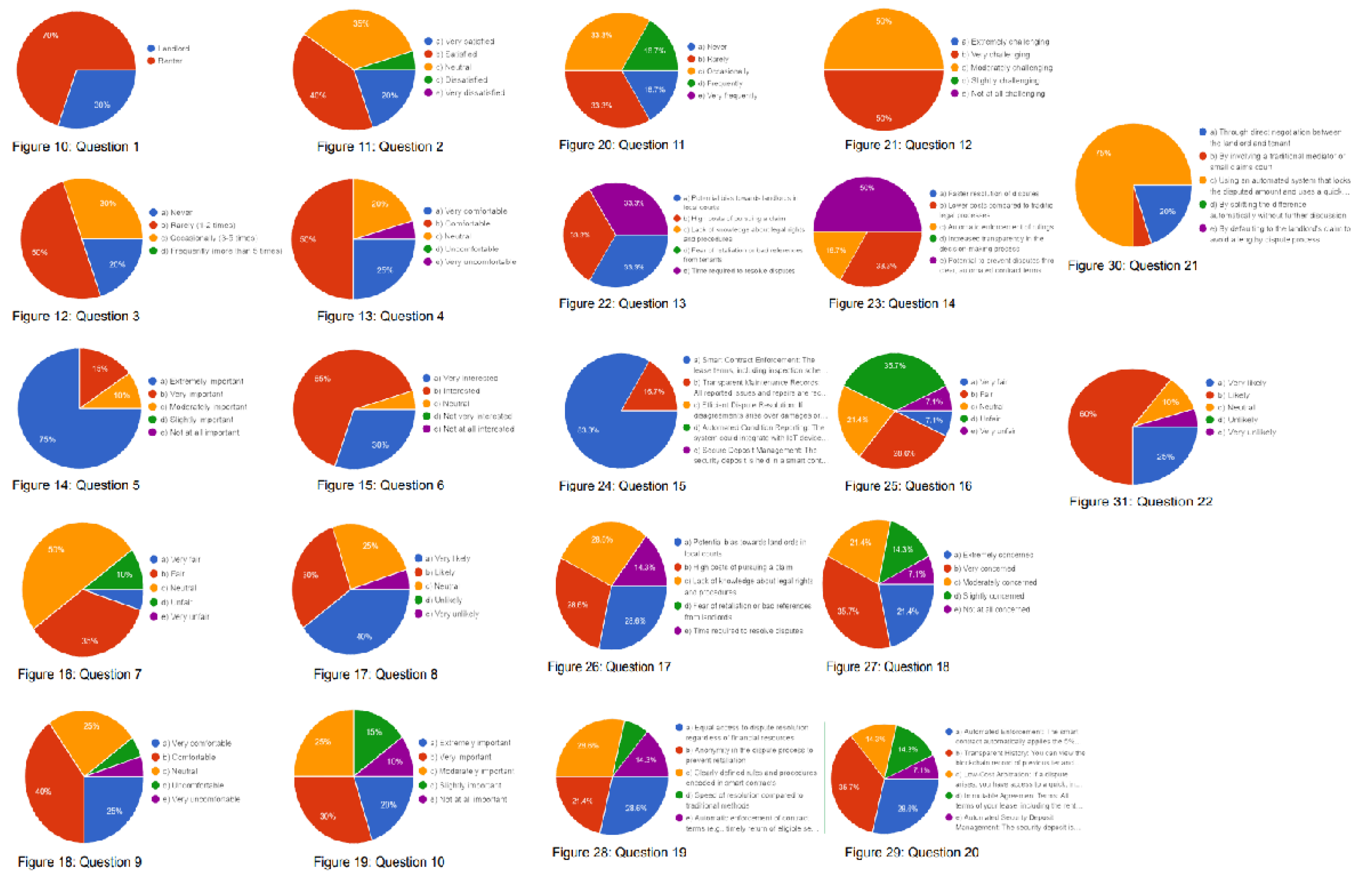

6.2. Survey Analysis

To gauge market readiness and user perceptions, we conducted a comprehensive survey targeting landlords and tenants involved in rental processes. The survey consisted of 22 questions covering a range of topics, including:

Satisfaction with current rental processes.

Experiences with rental disputes.

Comfort levels with digital technologies.

Willingness to adopt blockchain-based solutions.

The survey provided valuable insights into the potential adoption challenges and opportunities for the DRADR model. These findings helped us understand how users might interact with and perceive such a system in practice.

6.3. Data Analysis

Case Studies: We conducted a qualitative comparison of outcomes and processes, examining how the DRADR model could improve upon traditional methods in real-world scenarios.

Game Theory: We carried out equilibrium analyses and payoff comparisons to understand the strategic implications of the DRADR model.

Survey: We applied descriptive statistics and thematic analysis to survey responses, identifying key trends and attitudes toward blockchain-based rental solutions.

6.4. Validation of Hypotheses

The results from our evaluation methods were used to validate three main hypotheses:

H1: The implementation of DeFi principles in a blockchain-based rental agreement system significantly increases the efficiency of rent collection and reduces disputes compared to traditional rental processes.

H2: A blockchain-based rental system with low-cost arbitration significantly reduces the likelihood of landlords making unfair claims on security deposits compared to traditional rental systems.

H3: A blockchain-based rental agreement system with transparent terms, automated enforcement, and accessible dispute resolution significantly reduces information asymmetry and increases perceived fairness for tenants compared to traditional rental agreements.

6.5. Case Study Analysis

For each case, we conducted a detailed analysis comparing how the DRADR model could have addressed the issues differently from traditional methods. Our comparison focused on five key aspects: efficiency, fairness, dispute prevention, transparency, and record-keeping. This analysis allowed us to explore the potential real-world applications and benefits of the DRADR model in complex legal scenarios.

Each of these methodological approaches was carefully selected to provide complementary insights, enabling us to triangulate our findings and develop a comprehensive understanding of the potential impacts of the DRADR model. By combining theoretical modeling with practical implementation considerations and user perception analysis, we aim to provide precise answers to our research questions and validate our hypotheses regarding the efficiency, fairness, and balance of power in blockchain-based rental agreements.

7. Results and Discussion

This section presents the findings of our study, focusing on the potential advantages and limitations of the Decentralized Rental Agreement and Dispute Resolution (DRADR) model. By applying theoretical and practical evaluation methods, we demonstrate how the DRADR model compares to traditional rental systems. Our analysis aims to highlight key areas where the DRADR model could improve efficiency, fairness, and transparency in rental agreements, while addressing common challenges in dispute resolution.

7.1. Theoretical Case Study Analysis

To evaluate the potential impact of the Decentralized Rental Agreement and Dispute Resolution (DRADR) model, we applied it to three landmark legal cases in rental disputes. This analysis allows us to explore how the DRADR model might address real-world issues differently from traditional methods.

7.1.1. Moorjani v Durban Estates Ltd [2015] EWCA Civ 1252

This case

3 involved a lessee’s claim for damages due to degradation of his flat during a period of non-occupation. The Court of Appeal ruled that damages should compensate for the loss of amenity value, not just the actual discomfort experienced.

Under the DRADR model, lease terms, including repair obligations, would be encoded in a smart contract. This would enable:

Automatic calculation of damages based on amenity value impairment, regardless of occupancy.

Immutable blockchain records of the property’s condition and repair attempts.

Swift dispute resolution through the decentralized arbitration system.

Table 3.

Comparative Analysis of Case 1: Traditional Method vs. DRADR Model.

Table 3.

Comparative Analysis of Case 1: Traditional Method vs. DRADR Model.

| Aspect |

Traditional Method |

DRADR Model |

| Efficiency |

Resolution time: Months/Years. |

Resolution time: Days/Weeks. |

| Fairness |

Inconsistent damage calculations. |

Consistent calculations regardless of occupancy. |

| Dispute Prevention |

Reactive approach to repairs. |

Real-time monitoring for immediate repairs. |

| Documentation |

Manual, potentially incomplete. |

Automated, comprehensive blockchain records. |

| Damage Assessment |

Subjective, time-consuming. |

Automated, based on amenity value impairment. |

This approach aligns with Katsh and Rabinovich-Einy’s (2017) argument that online dispute resolution systems can offer more flexible and tailored approaches to complex legal issues.

7.1.2. Arnold v Britton & Others [2015] UKSC 36

This case

4 dealt with the interpretation of service charge terms in long-term leases, where fixed-rate increases led to potentially unfair outcomes. The Supreme Court emphasized the need for explicit contractual language over "commercial common sense."

The DRADR model would address this issue by:

Encoding clear, unambiguous lease terms in smart contracts to prevent misinterpretation.

Providing transparent, immutable records of all contractual obligations and transactions.

Offering automated mechanisms to calculate service charges and adjust them dynamically, ensuring fairness for both parties.

Table 4.

Comparative Analysis of Case 2 between Traditional method and DRADR model.

Table 4.

Comparative Analysis of Case 2 between Traditional method and DRADR model.

| Aspect |

Traditional Method |

DRADR Model |

| Efficiency |

Manual calculations, prone to

errors |

Automated calculations,

reduced administrative burden . |

| Fairness |

Rigid, potentially unfair

long-term terms |

Flexible, market-responsive

adjustments possible . |

| Dispute Prevention |

Limited visibility of future

charges |

Clear alerts for significant future increases |

| Term Amendments |

Difficult to modify agreed

terms |

Programmable adjustments

based on indices/costs. |

| Transparency |

Limited access to calculation

methods |

Equal access to terms and calculations for all parties . |

The decentralized arbitration system could potentially offer a more flexible approach, considering factors such as market conditions and the original intent of the parties, which traditional courts might be constrained from considering due to strict interpretations of contract law.

7.1.3. Youssefi v Musselwhite/Horne & Meredith Properties v Cox and Billingsley [2014] EWCA Civ 423

These cases

5 focused on grounds for opposing new tenancies under the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954, emphasizing the significance of substantial breaches and landlord-tenant relationships. The DRADR model would address the issues raised in these cases by:

Encoding lease terms, including user covenants, in the smart contract.

Maintaining a comprehensive, tamper-proof record of all interactions, breaches, and disputes.

Providing a mechanism for objective assessment of "substantial" breaches through data analysis.

Table 5.

Comparative Analysis of Case 3 between Traditional method and DRADR model.

Table 5.

Comparative Analysis of Case 3 between Traditional method and DRADR model.

| Aspect |

Traditional Method |

DRADR Model |

| Efficiency |

Time-consuming renewal

decision process |

Streamlined decisions based

on clear, objective records. |

| Fairness |

Subjective interpretations of

breaches |

Impartial record-keeping for

fact-based decisions adjustments possible . |

| Dispute Prevention |

Reactive approach to

breaches |

Early notifications to prevent

escalation of issues |

| Record Keeping |

Incomplete or unreliable

tenancy history |

Comprehensive, tamper-proof

record of all interactions. |

| Breach Assessment |

Subjective evaluation of

"substantial" breaches |

Potential for more objective

assessment through data analysis |

7.1.4. Synthesis of Overall Impact on Rental Dispute Resolution

Table 6.

Overall benefits of the DRADR model across different types of landlord-tenant disputes.

Table 6.

Overall benefits of the DRADR model across different types of landlord-tenant disputes.

| Aspect |

Improvement with DRADR Model |

| Efficiency |

Significant reduction in processing and

resolution times . |

| Fairness |

more consistent and impartial application of

rules and calculations . |

| Dispute Prevention |

Proactive measures through real-time

monitoring and clear terms. |

| Transparency |

Improved access to information for all parties. |

| Record Keeping |

Comprehensive, tamper-proof blockchain

records |

The application of the DRADR model to these landmark cases reveals its potential to significantly improve rental dispute resolution:

Efficiency: The DRADR model could substantially reduce processing and resolution times, addressing a fundamental issue in traditional legal systems—access to justice. Offering low-cost arbitration and swift resolution mechanisms provides a more accessible and equitable path to dispute resolution, aligning with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 16. .

Fairness: The model promotes a more consistent and impartial application of rules and calculations. Its accessible and transparent arbitration process levels the playing field, encouraging fair practices and discouraging exploitative behavior from either party.

Dispute Prevention: By implementing proactive measures through real-time monitoring and clear terms, the DRADR model has the potential to prevent many disputes [

29] from arising in the first place.

Transparency: Improved access to information for all parties enhances trust and reduces information asymmetry, a common source of conflict in traditional rental agreements.

Record Keeping: Comprehensive, tamper-proof blockchain records provide an indisputable history of the rental agreement, which can be crucial in resolving disputes fairly. Blockchain’s transparency and security are essential for maintaining the integrity of dispute resolutions.

The integration of decentralized justice in the DRADR model addresses the issue of power imbalances often present in landlord-tenant disputes. In traditional systems, tenants may be deterred from seeking justice due to the costs and complexities involved. The DRADR model’s [

30] accessible and transparent arbitration process could significantly rebalance this dynamic.

7.2. Limitations

The automated damage calculation proposed for the Moorjani case, for instance, assumes a level of data availability and standardization that may not currently exist in property management. Additionally, our analysis focuses on a limited number of high-profile cases from common law jurisdictions, which may not represent the full spectrum of rental disputes globally. The DRADR model’s effectiveness could vary significantly in civil law systems or in jurisdictions with vastly different property rights structures.

Furthermore, the analysis assumes a level of technological literacy and blockchain adoption that is not yet universal, potentially overstating the immediate applicability of the DRADR model in some markets. Without empirical data from real-world implementation, we cannot definitively prove the DRADR model’s effectiveness in resolving these types of disputes, particularly in terms of user acceptance and long-term market effects.

Despite these limitations, the case study analysis demonstrates the significant potential of the DRADR model to address long-standing issues in rental dispute resolution. Using blockchain technology and smart contracts, it offers a promising approach to creating more efficient, fair, and transparent rental markets.

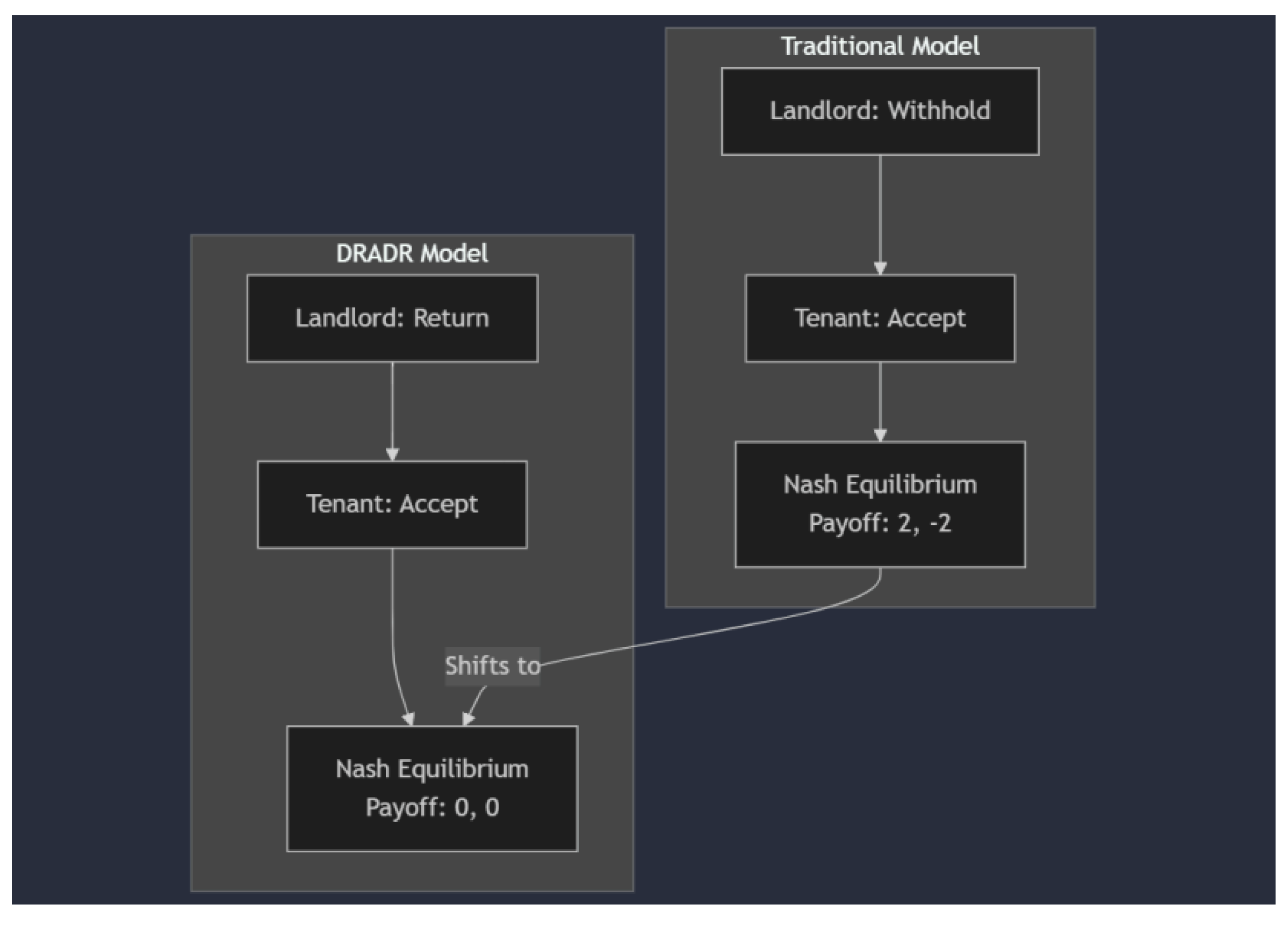

7.3. Game-Theoretic Model Analysis

To understand the strategic implications of the Decentralized Rental Agreement and Dispute Resolution (DRADR) model, we developed game-theoretic models for both traditional rental agreements and the DRADR model. This analysis allows us to assess how the DRADR system alters the strategic dynamics between landlords and tenants, particularly in security deposit disputes.

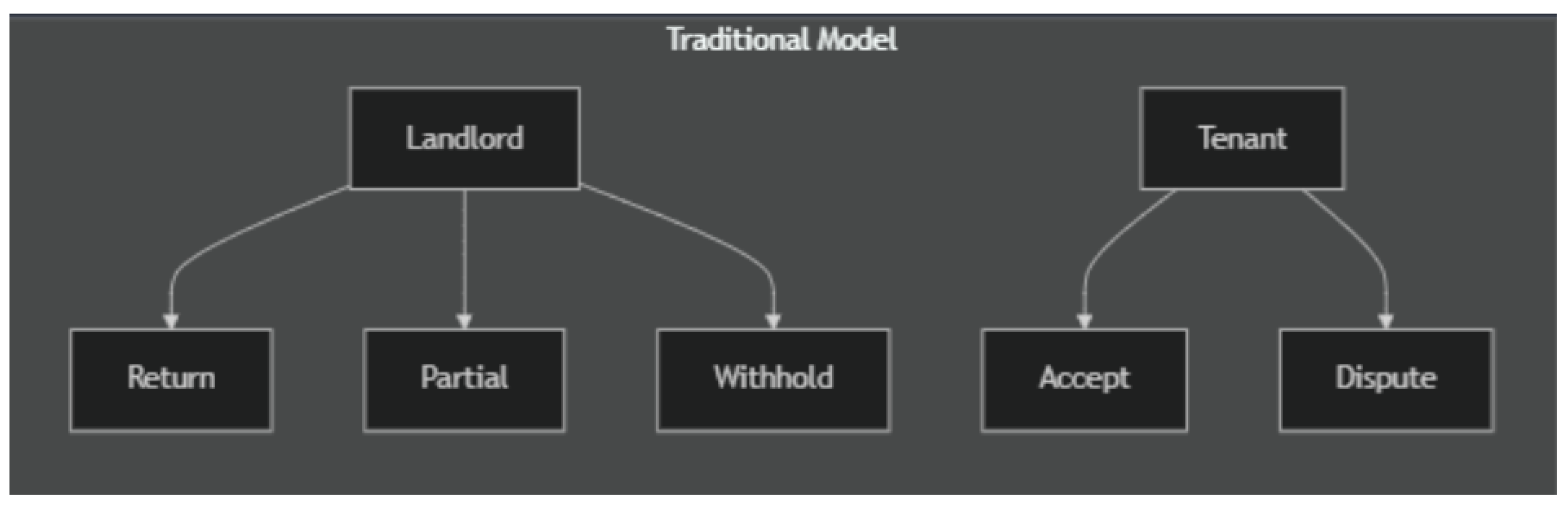

7.3.1. Game Theory Models and Results

Traditional Model: In the traditional model, there are two players: the Landlord (L) and the Tenant (T). The strategies available to landlords are:

The strategies available to tenants are:

Accept the decision (A)

Dispute the decision (D)

Figure 3.

Traditional Model.

Figure 3.

Traditional Model.

The payoff matrix for the traditional model is as follows:

Table 7.

Payoff Matrix for Traditional Model

Table 7.

Payoff Matrix for Traditional Model

| |

Tenan |

|

| Landlord |

Accept (A) |

Dispute (D). |

| Return (R) |

(0,0) |

(-1,1) |

| Return (P) |

(1,-1) |

(-2,0) |

| Return (W) |

(2,-2) |

(-3,1) |

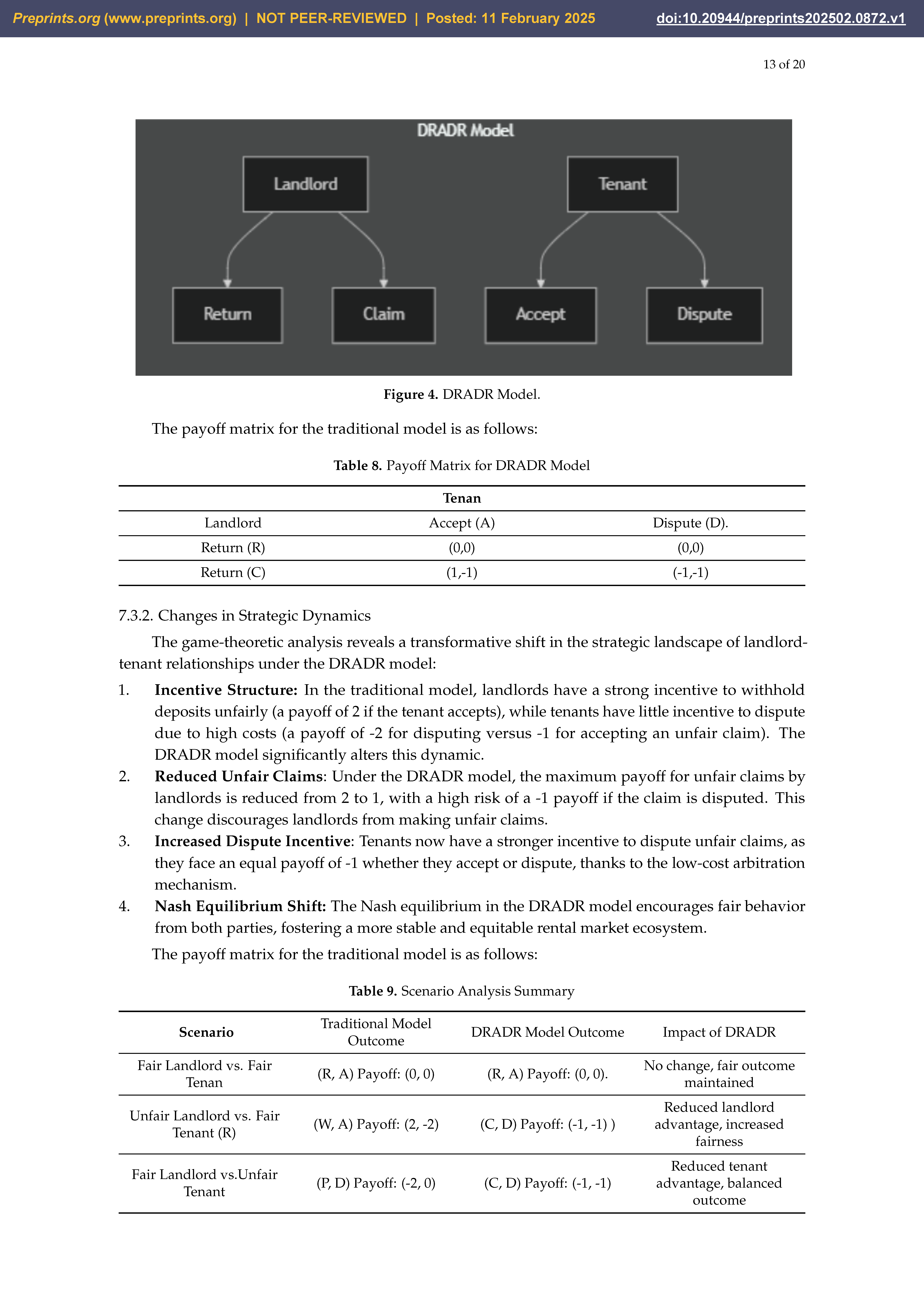

DRADR Model: In the DRADR model, the strategies are slightly different due to its automated nature:

Landlord strategies:

Return full deposit (R)

Claim damages (C)

Tenant strategies:

Accept claim (A)

Dispute claim (D)

The payoff matrix for the traditional model is as follows:

Table 8.

Payoff Matrix for DRADR Model

Table 8.

Payoff Matrix for DRADR Model

| |

Tenan |

|

| Landlord |

Accept (A) |

Dispute (D). |

| Return (R) |

(0,0) |

(0,0) |

| Return (C) |

(1,-1) |

(-1,-1) |

7.3.2. Changes in Strategic Dynamics

The game-theoretic analysis reveals a transformative shift in the strategic landscape of landlord-tenant relationships under the DRADR model:

Incentive Structure: In the traditional model, landlords have a strong incentive to withhold deposits unfairly (a payoff of 2 if the tenant accepts), while tenants have little incentive to dispute due to high costs (a payoff of -2 for disputing versus -1 for accepting an unfair claim). The DRADR model significantly alters this dynamic.

Reduced Unfair Claims: Under the DRADR model, the maximum payoff for unfair claims by landlords is reduced from 2 to 1, with a high risk of a -1 payoff if the claim is disputed. This change discourages landlords from making unfair claims.

Increased Dispute Incentive: Tenants now have a stronger incentive to dispute unfair claims, as they face an equal payoff of -1 whether they accept or dispute, thanks to the low-cost arbitration mechanism.

Nash Equilibrium Shift: The Nash equilibrium in the DRADR model encourages fair behavior from both parties, fostering a more stable and equitable rental market ecosystem.

The payoff matrix for the traditional model is as follows:

Table 9.

Scenario Analysis Summary

Table 9.

Scenario Analysis Summary

| Scenario |

Traditional Model

Outcome |

DRADR Model Outcome |

Impact of DRADR |

| Fair Landlord vs. Fair Tenan |

(R, A) Payoff: (0, 0) |

(R, A) Payoff: (0, 0). |

No change, fair outcome maintained |

| Unfair Landlord vs. Fair Tenant (R) |

(W, A) Payoff: (2, -2) |

(C, D) Payoff: (-1, -1) ) |

Reduced landlord advantage, increased fairness |

| Fair Landlord vs.Unfair Tenant |

(P, D) Payoff: (-2, 0) |

(C, D) Payoff: (-1, -1) |

Reduced tenant advantage, balanced

outcome |

Figure 5.

Nash Equilibrium Comparisonl.

Figure 5.

Nash Equilibrium Comparisonl.

7.3.3. Implications for Landlord-Tenant Relationships and Market Equilibrium

The game-theoretic modeling of the DRADR system reveals significant implications for landlord-tenant relationships and the overall rental market:

Power Balance: The DRADR model addresses the issue highlighted by Miceli and Sirmans (1999) regarding landlords’ potential to exploit information asymmetries [25]. By reducing the potential gains from unfair actions, DRADR creates a more balanced playing field.

Dispute Resolution: The increased incentive for tenants to dispute unfair claims under the DRADR model represents a significant shift in power dynamics. This aligns with Ambrose and Kim’s (2003) observations on how alternative system structures can rebalance landlord-tenant relationships [26]. Trust Enhancement:The consistent optimal outcome (0,0) for fair actions in the DRADR model suggests that the system effectively incentivizes honest behavior from both parties. This aligns with the way blockchain-based systems enhance trust by aligning incentives.

Market Efficiency: By discouraging unfair claims and promoting fair behavior, the DRADR model could reduce the overall number of disputes, potentially increasing the efficiency of the rental market.

Long-Term Relationships: The model could foster stronger long-term relationships between landlords and tenants, as both parties are incentivized to act fairly from the outset.

Table 10.

Payoff Comparison Table: Traditional vs DRADR Model

Table 10.

Payoff Comparison Table: Traditional vs DRADR Model

| Aspect |

Traditional Method |

DRADR Model |

| Incentive for Unfair Claims by

Landlords |

Strong (payoff of 2 if tenant

accepts) |

Reduced (max payoff of 1,

high risk of -1). |

| Tenant Incentive to Dispute

Unfair Claims |

Low (payoff of -2 vs -1 for

accepting) |

High (payoff of -1 in both

cases due to low-cost arbitration) . |

| Fairness Incentives |

Unfair actions can lead to

higher payoffs |

Fair actions (Return, Accept)

consistently provide the best Mmutual outcome (0,0) |

| Maximum Landlord Payoff for

Unfair Action |

2 (for withholding deposit) |

1 (for unfair claim). |

| Tenant Payoff for Accepting Unfair Claim |

-2 |

-1 |

| Mutual Payoff for Fair Action |

(0,0) |

(0,0) |

| Risk for Landlord Making Unfair Claim |

Low (worst case: -3) |

Higher (50% chance of -1) |

Table 11.

Predicted Behavior Changes

Table 11.

Predicted Behavior Changes

| Aspect |

Traditional Method |

DRADR Model |

| Landlord Claim Behavior |

Strong More likely to overclaim |

More accurate claims. |

| Tenant Dispute Likelihood |

Low due to high costs |

Higher due to low-cost arbitration . |

| Speed of Resolution |

Slower |

Faster |

| Fairness of Outcomes |

Variable |

More consistent. |

These changes in strategic dynamics and their implications directly address Research Question 2 (RQ2) by demonstrating how a blockchain-based rental system alters the game-theoretic dynamics between landlords and tenants, particularly in security deposit disputes. The analysis provides strong support for Hypothesis 2 (H2), showing that a blockchain-based rental system with low-cost arbitration significantly reduces the likelihood of landlords making unfair claims on security deposits.

8. Analysis of User Attitudes Towards Traditional and Blockchain-Based Systems

Our survey, comprising 22 questions, explored various topics such as satisfaction with current rental processes, experiences with rental disputes, comfort with digital technologies, and willingness to adopt blockchain-based solutions. Below are the key findings:

8.1. Key Findings

The responses provided valuable insights into the pain points faced by tenants and landlords, as well as the potential opportunities for adopting blockchain technology to address these issues. Below, we summarize the Key Findings derived from the survey, which highlight critical areas of concern and user preferences.

Table 12.

A snippet of the responses collected.

Table 12.

A snippet of the responses collected.

| Key Findings |

Responses |

| Satisfaction with Current Processes |

45% of respondents expressed satisfaction with their current rental agreement processes.

55% were dissatisfied, highlighting a clear need for improvement in the rental market. |

| Dispute Prevention |

The majority of respondents reported not encountering frequent disputes in their rental experiences. |

| Security Deposit Management |

Only 35% of respondents considered the current process for managing security deposits to be fair.

This low percentage underscores significant issues with the current system. |

| Concerns About Unfair Treatment |

60% of tenants expressed strong or extreme concern about unfair treatment in damage assessments. |

| Dispute Resolution Concerns |

70% of tenants identified high costs or bias toward landlords as their primary concerns with traditional dispute resolution systems. |

| Major Concerns by Party |

Tenants: Unfair treatment and high costs in disputes.

Landlords: Rent collection was the most common concern. |

| Comfort with Digital Technologies |

75% of respondents were comfortable using digital technologies for rental agreements and dispute resolution.

An additional 20% were neutral. |

| Interest in Low-Cost and Fast Arbitration |

75% of respondents found the concept of low-cost, fast arbitration appealing. |

| Comfort with Blockchain-Based Systems |

60% of the respondents expressed comfort with using blockchain-based systems for managing rental agreements and dispute resolution. |

The dissatisfaction with current rental agreement processes (55%) and the low fairness perception of security deposit management (35%) present significant opportunities for solutions like DRADR. These findings also emphasize the high levels of concern among tenants about unfair treatment (60%) and biased dispute resolution (70 % ), suggesting a clear power imbalance in traditional systems. These concerns align with prior research, such as Desmond and Wilmers (2019) and Greif (2018), which examined landlord-tenant dynamics and the challenges of fairness in rental agreements.

8.2. Openness to Digital Solutions and Implications for DRADR Adoption

The survey revealed a high level of comfort with digital technologies (75% comfortable, 20% neutral), indicating a readiness for digital solutions in the rental market. However, the lower comfort level with blockchain-based systems (60%) suggests a need for education and trust-building specifically around blockchain technology.

The DRADR model’s focus on fair and transparent security deposit management directly addresses major pain points in the current system. By emphasizing impartial, automated processes and low-cost arbitration, DRADR could particularly appeal to tenants. To attract landlords, the model should highlight features like streamlined rent collection.

For the 25% of respondents who were not comfortable or were neutral about digital technologies, a gradual adoption strategy is recommended. This could include pilot programs, optional blockchain features, or hybrid systems combining traditional and blockchain elements. Bridging the gap between general digital comfort and blockchain-specific comfort will require educational initiatives and user-friendly interfaces that simplify blockchain interactions.

Building trust in the DRADR system is essential and can be supported by transparency measures, security certifications, and partnerships with respected real estate institutions. These steps will help address market concerns and foster widespread acceptance of blockchain-based solutions.

Building trust in DRADR is crucial for widespread adoption. This can be achieved through:

Transparency measures, such as immutable blockchain records accessible to all stakeholders.

Security certifications, ensuring the reliability and safety of the platform.

Partnerships with established and respected real estate institutions to enhance credibility.

By aligning with these strategies, DRADR has the potential to overcome user hesitancy and disrupt traditional rental practices effectively, addressing the market’s current inefficiencies and fostering long-term trust.

9. Synthesis of Findings and Implications for DRADR

This section synthesizes insights from the theoretical case study analysis, game-theoretic modeling, and survey analysis to comprehensively evaluate the Decentralized Rental Agreement and Dispute Resolution (DRADR) model. It addresses key research questions and hypotheses while exploring the broader implications for the rental market and blockchain adoption.

9.1. Integration of Insights

To comprehensively evaluate the DRADR model, insights from different methodologies are combined. The integration of case studies, game-theoretic analysis, and survey findings allows for a nuanced understanding of how DRADR addresses core challenges in the rental market, including efficiency, fairness, transparency, and technological adoption.

-

Efficiency and Fairness

Case Study Analysis: DRADR demonstrated potential to significantly reduce dispute resolution time from months or years to days or weeks, while enabling more consistent damage assessments.

Game Theory: The model incentivizes fair behavior and discourages unfair claims by altering the payoff structures for landlords and tenants.

Survey Findings: 75% of respondents found low-cost, fast arbitration appealing, aligning closely with DRADR’s focus on efficiency and fairness.

-

Power Balance

Case Study Analysis: Transparent and automated processes in DRADR could create a more balanced dynamic in landlord-tenant disputes.

Game Theory: By lowering the cost of challenging unfair claims, DRADR reduces landlords’ advantage in security deposit disputes and empowers tenants.

Survey Findings: With 60% of tenants concerned about unfair treatment, DRADR’s balanced approach addresses a clear market need.

-

Transparency and Trust

Case Study Analysis: Blockchain-based record-keeping in DRADR offers immutable, comprehensive documentation of all transactions and interactions.

Game Theory: DRADR fosters honest behavior by establishing a new equilibrium based on transparency.

Survey Findings: Only 35% of respondents viewed current security deposit management as fair, underscoring the need for DRADR’s transparent and trust-enhancing features.

-

Technology Adoption

Case Study Analysis: DRADR’s effectiveness depends on technological infrastructure, which may not yet be universally accessible.

Game Theory: The model assumes all parties have access to and an understanding of relevant technologies.

Survey Findings: While 75% of respondents are comfortable with digital technologies, only 60% expressed confidence in blockchain systems, highlighting a need for education and phased implementation.

9.2. Addressing Research Questions and Hypotheses

The research questions and hypotheses are examined through a multi-faceted approach, leveraging findings from the case study analysis, game theory modeling, and survey data. This comprehensive approach ensures that conclusions are robust and aligned with the practical realities of the rental market and blockchain adoption.

RQ1: How does the integration of DeFi principles in a blockchain-based rental agreement system affect the efficiency and fairness of the rental process? Findings: Strong evidence supports Hypothesis 1, showing DRADR’s ability to enhance rent collection efficiency and reduce disputes. The case study analysis demonstrated faster dispute resolution, the game-theoretic model highlighted fairer outcomes, and the survey confirmed demand for low-cost arbitration.

RQ2: How does the implementation of a blockchain-based rental system alter the game-theoretic dynamics between landlords and tenants, particularly in security deposit disputes? Findings: Hypothesis 2 is validated as DRADR’s low-cost arbitration mechanism deters landlords from making unfair claims and encourages equitable behavior. Survey results and game-theoretic analysis reveal a new equilibrium that addresses power imbalances.

RQ3: To what extent can a blockchain-based rental agreement system mitigate the power imbalances inherent in traditional landlord-tenant relationships? Findings: Hypothesis 3 is supported by DRADR’s transparent terms, automated enforcement, and accessible dispute resolution processes. These features reduce information asymmetry and increase perceived fairness, as demonstrated in both case studies and survey responses.

9.3. Overall Implications for the Rental Market and Blockchain Adoption

DRADR has the potential to transform the rental market by reducing disputes, lowering transaction costs, and fostering trust between landlords and tenants. Its ability to streamline processes and provide fair arbitration mechanisms could lead to more stable, long-term rental relationships.

The model’s alignment with the need for accessible, low-cost dispute resolution was evident in case studies and survey results. However, successful implementation will require adjustments to legal frameworks to recognize blockchain-based agreements and arbitration decisions. While general comfort with digital technologies is high, the gap in blockchain-specific comfort highlights the importance of education, gradual rollout strategies, and user-friendly design.

DRADR also poses a challenge to traditional intermediaries in the rental industry, potentially facing resistance from established players. Despite this, its principles can be adapted across various legal systems, offering a scalable, global solution to inefficiencies in the rental market. Finally, industry-wide standardization of property condition assessments and damage calculations will be critical to DRADR’s success.

10. Conclusion and future Work

This research has demonstrated the transformative potential of the Decentralized Rental Agreement and Dispute Resolution (DRADR) model, offering a blockchain-based solution to modernize and streamline rental agreements and dispute resolution. By integrating blockchain technology, decentralized finance principles, and game theory, DRADR addresses critical inefficiencies and imbalances in the rental market, promoting fairness, transparency, and efficiency. The game-theoretic analysis provided a quantitative foundation for fairness, showing how DRADR can rebalance power dynamics between landlords and tenants. By applying the model to real-world legal cases, this study highlighted DRADR’s ability to automate complex processes, ensuring transparency and reducing the time and cost associated with traditional dispute resolution methods. These contributions position DRADR as a significant step forward for both proptech and legal tech, with implications for reshaping contract law and property management globally.

However, to further advance this model and make it more applicable in the real world, several areas require further research and development. Pilot studies should be conducted to validate DRADR’s effectiveness, refine automated damage assessments, and identify challenges in user adoption. Expanding the case analysis to various legal jurisdictions and rental types, such as short-term and commercial leases, will assess the model’s adaptability and broader applicability. Enhancing the arbitration process through advanced arbitrator selection mechanisms and integrating AI/ML technologies will ensure fairer, more efficient dispute resolution. Furthermore, technological advancements are necessary to integrate DRADR with emerging blockchain platforms, improve scalability, and reduce transaction costs. Privacy features like zero-knowledge proofs and enabling interoperability between blockchain systems should also be explored.

By addressing these avenues, future work will refine and expand the DRADR model, contributing to the broader adoption of blockchain technology in property management and helping to create a more transparent and efficient global rental market.

Author Contributions

Muntasir Jaodun and Khawla Bouafia worked on the conceptualization of the raised issue; they wrote the original draft version, and then carried out editing the revision. Muntasir J. carried out the operationalization and coding of the models. Khawla B. proofread the draft and revision, and supervised the process. Khawla. acquired funding to support the creation of the paper. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was supported by the ELTE EKÖP

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data and code presented in this study are available on request from the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Webster, J.; Watson, R.T. Analyzing the Past to Prepare for the Future: Writing a Literature Review. erIS Quarterly 2002, xiii–xxii. [Google Scholar]

- Bouafia, K.; Gulalov, M. Blockchain Solutions for Authorization and Authentication. Procedia Computer Science 2024, 237, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, S.; Bitcoin, A. A peer-to-peer electronic cash system. Bitcoin.–URL: https://bitcoin. org/bitcoin. pdf 2008, 4, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Monrat, A.A.; Schelén, O.; Andersson, K. A survey of blockchain from the perspectives of applications, challenges, and opportunities. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 117134–117151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaga, D.; Mell, P.; Roby, N.; Scarfone, K. Blockchain technology overview. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.11078. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, A.; Bonneau, J.; Felten, E.; Miller, A.; Goldfeder, S. Bitcoin and cryptocurrency technologies: a comprehensive introduction; Princeton University Press, 2016.

- Abbas, Q.E.; Sung-Bong, J. A survey of blockchain and its applications. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Information and Communication (ICAIIC). IEEE; 2019; pp. 001–003. [Google Scholar]

- Bouafia, K.; Molnár, B.; Majid, G. Blockchain Technologies for Transparency in FinTech. In Proceedings of the International Congress on Information and Communication Technology. Springer; 2024; pp. 575–585. [Google Scholar]

- Dabbagh, M.; Choo, K.K.R.; Beheshti, A.; Tahir, M.; Safa, N.S. A survey of empirical performance evaluation of permissioned blockchain platforms: Challenges and opportunities. computers & security 2021, 100, 102078. [Google Scholar]

- Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Del Vecchio, P.; Oropallo, E.; Secundo, G. Blockchain technology for bridging trust, traceability and transparency in circular supply chain. Information & Management 2022, 59, 103508. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.N.; Loukil, F.; Ghedira-Guegan, C.; Benkhelifa, E.; Bani-Hani, A. Blockchain smart contracts: Applications, challenges, and future trends. Peer-to-peer Networking and Applications 2021, 14, 2901–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannen, C. Introducing Ethereum and solidity; Springer, 2017; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, I.; Alqarni, M.A.; Almazroi, A.A.; Alam, L. Real estate management via a decentralized blockchain platform. Comput. Mater. Contin 2021, 66, 1813–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriarty, C. Is RealT Reality? Investigating the Use of Blockchain Technology and Tokenization in Real Estate Transactions. Minn. JL Sci. & Tech. 2022, 24, 471. [Google Scholar]

- Abualhamayl, A.; Almalki, M.; Al-Doghman, F.; Alyoubi, A.; Hussain, F.K. Blockchain for real estate provenance: an infrastructural step toward secure transactions in real estate E-Business. Service Oriented Computing and Applications 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, A.; Rule, C. Online dispute resolution for smart contracts. J. Disp. Resol. 2019, 103. [Google Scholar]

- Azari, K.; Malek, S. Blockchain applications in Real Estate: challenges and a proposed framework 2021.

- Dong, Y.; Dong, Z. Bibliometric Analysis of Game Theory on Energy and Natural Resource. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadioglu Kumtepe, C.C. A brief introduction to blockchain dispute resolution. J. Marshall LJ 2020, 14, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuk, A. Applying blockchain to the modern legal system: Kleros as a decentralised dispute resolution system. International Cybersecurity Law Review 2023, 4, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Choudhury, A. Tokenization of real estate assets using blockchain. International Journal of Intelligent Information Technologies (IJIIT) 2022, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guseva, Y. Decentralized Markets and Decentralized Regulation. George Washington Law Review 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, G. Regulating Decentralized Financial Technology: A Qualitative Study on the Challenges of Regulating DeFi with a Focus on Embedded Supervision. Stan. J. Blockchain L. & Pol’y 2024, 7, 136. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Greenwood, D.; Kassem, M. Blockchain in the built environment and construction industry: A systematic review, conceptual models and practical use cases. Automation in construction 2019, 102, 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, G.; et al. Ethereum: A secure decentralised generalised transaction ledger. Ethereum project yellow paper 2014, 151, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Amponsah, A.A.; Adebayo, F.A.; WEYORI, B.A. Blockchain in insurance: Exploratory analysis of prospects and threats. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OLIVEIRA, N.B. THE ROLE OF INTERNATIONAL ARBITRATION IN RESOLVING CROSS-BORDER SMART CONTRACT DISPUTES: OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES 2023.

- Muldoon-Smith, K.; Greenhalgh, P. Realigning the built environment. RICS Building Surveying Journal 2016, 2016, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Druckman, D. Doing research: Methods of inquiry for conflict analysis; Sage Publications, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, D. Wealth and the marital divide. American Journal of Sociology 2011, 117, 627–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

Youssefi v Musselwhite/Horne Meredith Properties v Cox and Billingsley [2014] EWCA Civ 423 clarified landlords’ rights to oppose lease renewals based on substantial tenant breaches. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).