1. Introduction

Collaboration between industry and research entities plays a crucial role in systematically addressing the business needs within organisations [

1,

2,

3]. Applied research is becoming popular in this sector for the practical integration of technical knowledge to a targeted business purpose. Large organizations can set up independent research establishments focusing on their business needs. However, for small and medium-scale enterprises, where resources are mostly limited, research activities are outsourced or executed in collaboration with research institutions like universities and industry research centres [

4]. Hence, there is a need for a collaboration-enabling platform that provides features such as project recommendations, collaboration matchmaking, and reputation tracking, thereby, ensuring efficient and trustable inter-organization collaboration among entities such as SMEs, research institutions and independent consultants in the execution of research related projects.

Previous research works [

5,

6,

7] have shown the need to decentralize the execution and governance of inter-organizational operations due to the opportunities that blockchain provides. Blockchain is a peer-to-peer (p2p) network where data is replicated and redundantly stored across nodes of the participants and by applying various consensus mechanisms, the network ensures that the information stored is consistent and formally validated by the participating peers[

8]. Data stored in the blockchain network are organized in blocks and are cryptographically linked to prevent modification. The tamper-proof nature of the blockchain ensures that information generated during the research collaboration processes cannot be altered. The distributed nature of the network ensures that the algorithms that enable these collaborations (such as matchmaking, recommendations, etc.) cannot be manipulated. Smart contracts are computer programs that run on the blockchain, automating the execution of business logic (such as collaboration rules) without depending on a central authority [

9]. Various blockchain-enabled research collaboration platforms exist. The research works [

10,

11] provide ecosystems for researchers to share and access scientific data and enable researchers to collaborate. The work [

12] explored blockchain as a tool for democratizing collaboration in innovation-related processes and providing a new funding landscape for entrepreneurs in executing their innovative projects. The research [

13] proposes an architectural design for stakeholders in Industry 4.0 such as universities, research organizations, OEMs, SME clusters, and software houses to collaborate and execute industry-related projects. It explores important collaboration-supporting features such as tender creation, matchmaking and platform governance. There is still limited work that explores decentralized and democratized collaboration between SMEs and research entities in the formulation, execution and management of research-related collaborations. Although the platform designed in [

13] supports participating organizations to run independent nodes that manage the collaboration lifecycle and data generated within the collaboration. Due to little integration of blockchain-like technologies, the governance of the platform and management of collaboration rules are highly centralized.

There is a need for a blockchain platform that supports business sectors such as SMEs, research institutions and consultants to collaborate in long and short-term research projects. Such a platform enables users to create projects in the form of problem requests, where crowd-based and automated solutions are combined in recommending potential project partners. Collaboration information such as completed projects, feedback on the collaborations, and accumulated reputations of the users over some time are all stored on the blockchain. To ensure high-quality collaboration outputs and reduce spam content, such a blockchain-enabled collaboration platform provides an incentive mechanism for rewarding users who positively contribute to the platform. Such an incentivisation scheme, thereby, provides a utility value that drives and sustains the platform. This type of value system can be realized using blockchain tokens. Still, cryptocurrencies which blockchain tokens are derived from are generally unstable, hence, reducing business organizations’ (such as SMEs’) interest in blockchain applications [

9]. Moreover, complex interactions between various types of users in the platform and their different objectives in using the platform will pose different outcomes for the platform. Hence, it is important to systematically identify and analyze these interactions and their expected outcomes, then implement a suitable token model that will provide the most utility value to the entities and users in the platform.

The objective of this research is to design a self-sustaining valuable token model that incentivises users that positively contribute to the platform. Self-sustainability in this case implies that the value of the platform token will not depend on external assets but rather on the demand for valuable features on the platform to which the tokens provide access. To achieve this objective, first, this paper uses game theory to systematically analyze the token-related interactions between the various user groups in the blockchain-enabled research collaboration platform. Then, simulate a token economics model that fairly distributes and rewards users accordingly. Furthermore, this paper shows a dynamic token-pricing model for the utility that the tokens provide access to within the platform. The rest of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 provides the background on relevant technical concepts(blockchain technologies, tokens and game theory concepts) and the running case that provides summarized the core features of the blockchain-based research collaboration platform.

Section 3 shows the game theory analyses of the platform’s tokens-related user interactions and a simulation of expected token outcomes for the users.

Section 4 shows the design and simulation of a dynamic token utility model Discussions resulting from the simulations, relevant risks on the designed token model and mitigation strategies are presented in

Section 5. Finally, the conclusion, research limitations and future works are presented in

Section 6.

2. Background and Preliminaries

This section describes the technical concepts and research background that provide the foundation for this work. The relevant technical concepts include - blockchain technologies, token concepts and game theory concepts. Furthermore, the running case is introduced to describe a blockchain-based application that enables research collaboration between entities such as SMEs, research institutions and consultants. The running case, thereby, provides the basis for the token model developed in the remaining sections of this work.

2.1. Technical Concepts

2.1.1. Blockchain Technology Concepts

The blockchain network consists of peers that run the nodes in the network. Access to blockchain networks is either restricted, eg. in private and consortium blockchain networks or unrestricted as seen in public networks. Data generated in the network is redundantly stored across the nodes of the peers within the network. This ensures that data is continuously available and accessible across the peers. Blockchain networks adopt various consensus algorithms to validate data before they are stored. This is to ensure information consistency across all the participating nodes. Consensus methods are generally divided into proof-based which is common in public networks and voting-based which is prevalent in permissioned networks[

8]. Computer programs that run on the blockchain are referred to as smart contracts. These programs are self-executable, hence, business logic and collaboration rules can be encoded in them and executed without relying on a central authority[

14]. Decentralized applications (DApps) are programs that are generated by one or more smart contracts where blockchain technologies provide support for such applications. The collaboration platform presented in this paper is a form of DApp comprising multiple smart contracts and blockchain technologies.

2.1.2. Blockchain Token Concepts

Blockchain-native cryptocurrencies provide mechanisms for executing and storing transactions on the blockchain networks. However, blockchain tokens provide the means for creating and exchanging values among the users of a DApp. Some of the common examples of tokens are utility, non-fungible tokens (NFTs), and governance tokens [

15]. Utility tokens are commonly used to provide access to services offered in a DApp. NFTs are used to provide a unique representation of information assets stored in a blockchain network. Governance tokens as the name implies allow the owners to participate in governing and charting the direction of future changes in a DApp. The token model designed in this paper for incentivization of the blockchain-based collaboration platform is a form of utility token.

2.1.3. Game Theory Concepts

A game consists of players, the actions which are the strategies they execute, responses to these actions and the outcome of the game. In our case, the players are represented as various classes of users that are onboarded to use the blockchain-based collaboration platform. A game is played by at least two players and all the actions executed by the players and responses to these actions are organized in a game tree. From the starting node to the end nodes of the tree represents all the possible outcomes from the game. The payoffs are the rewards allocated to each player at each end node of the tree. Information set refers to a player’s lack of knowledge about the states of incoming nodes and will play the same moves for the corresponding outgoing nodes. The players’ strategies and outcomes (payoffs) after executing these strategies are organized either in a tree or matrix format. A tree representation of the game is referred to as an extensive form while a matrix representation is referred to as a strategic form [

16]. Extensive form provides more information about a game showing the sequences of interactions and their timing. Hence, the paper applies the extensive form to analyse the token economic interactions between the various groups of the blockchain-based collaboration platform. The payoffs represent tokens earned by various users for executing specific collaboration conditions.

Figure 1.

Blockchain-based Collaboration Platform

Figure 1.

Blockchain-based Collaboration Platform

2.2. Running case: The Blockchain-Based Collaboration Platform

The features of the blockchain-based collaboration platform are summarized to provide an overview and background understanding of the token analyses conducted in the rest of this paper. However, in-depth descriptions of algorithms used to realize the various functions of the collaboration platform are out of the scope of the current paper.

Registration and project description: The collaboration platform enables users such as SMEs, research institutions and independent consultants to register and define their areas of interests and competencies as tags. Users can endorse the tags defined by other users. Hence, the initial capacity of each user can be measured by their tags and endorsements received on them. The users earn tokens by performing collaboration-related activities that add value to the platform. After registration, the users can start creating project collaboration requests. A project is defined in the context of this platform as a business/research need that requires collaboration with other users in the platform to solve. A project contains tags, summary descriptions and additional information attached as documents. A project can also be denoted as a service when a user offers solutions, technologies or processes which another platform user can directly consume.

Project collaborations set up: After projects are created, recommendations for collaborators are suggested to the project creator which they can accept or reject. The platform supports rule-based and crowd-based recommendations. The rule-based recommendation algorithms suggest collaborators based on the quality of tags(number of matched tags and endorsements on them) relevant to the project. In the crowd-based approach, the users can recommend themselves or other platform users to a project. If the project creator accepts a recommendation from another user (not the algorithm recommendation), the recommender receives a token reward from the platform. On completion of the project, the collaborators in the platform earn a specified amount of tokens which is dependent on the length of the project. Long-term collaborations receive a higher amount of tokens than short-term projects.

User performance measurements: The users’ performances are determined by the number of projects they create and participate in and the accepted recommendations that they provide. The platform uses experience points (XP) to estimate the reputation of the users. The users’ performance metrics as well as the feedback they receive from other users on the completion of project collaborations are used in calculating the XP. The tokens earned on the platform can be spent by consuming platform-specific services such as acquiring higher rankings for their profiles, projects or services within the limited time and space provided on the platform main page. Still, determining the amount of tokens awarded to the users for specific activities and how they are spent relative to the availability of the platform-specific services is not a trivial task. Hence, the need to apply in the next sections of the paper – game theory to formally analyse the token rewards for the users’ interactions and simulations to determine a suitable token distribution model.

3. Game Theory Token Analyses

To demonstrate the game theory of the economic outcomes (tokens) of interactions between the various types of users in the platform, first, the paper provides the applicable assumptions and players’ strategies. Later, the paper shows the game tree for realizing the matrixes used in calculating the expected outcomes for the players.

3.1. Assumptions and Strategies

The following assumptions are relevant to this game theory analysis:

All the platform users can be categorised into three players - SME, Research Institution (RI) and Consultants (Con)

How each user will use the platform is limited to the strategies connected to the player type the user belongs to

The entire collaboration in the platform is split into two games, SME-Con and SME-RI

Any of the games can only be started when the player type ’SME’ creates a project.

The SME will respond the same way to a particular player to either accept or reject their offer to collaborate, match recommendations or service suggestions. Hence, this SME move can be represented with an information set

The two games are played simultaneously and the total payout for each player is the combination of outcomes from each game

The following strategies are relevant to this game theory analysis:

-

The strategies that can be played by the SME include:

Create a project (C) or not create a project (N).

Accept (a) or reject (r) recommended match or collaboration offer from Consultant

Accept (A) or reject (R) RI collaboration Offer or Service suggestion

Take no further action after creating a project (n1) or invite RI to collaborate (I)

-

The strategies that can be played by the Consultant include:

-

The strategies that can be played by RI include:

Offer a service to SME (S) or Offer to collaborate with SME (O), or no initial action (n)

accept collaboration Invitation from SME (a1) or reject invite (r1)

3.2. Game Trees and Players Interactions Token Outcomes

The publicly available game theory explorer tool GTE

1 published in [

16] is used in realizing the game trees and the corresponding game matrix.

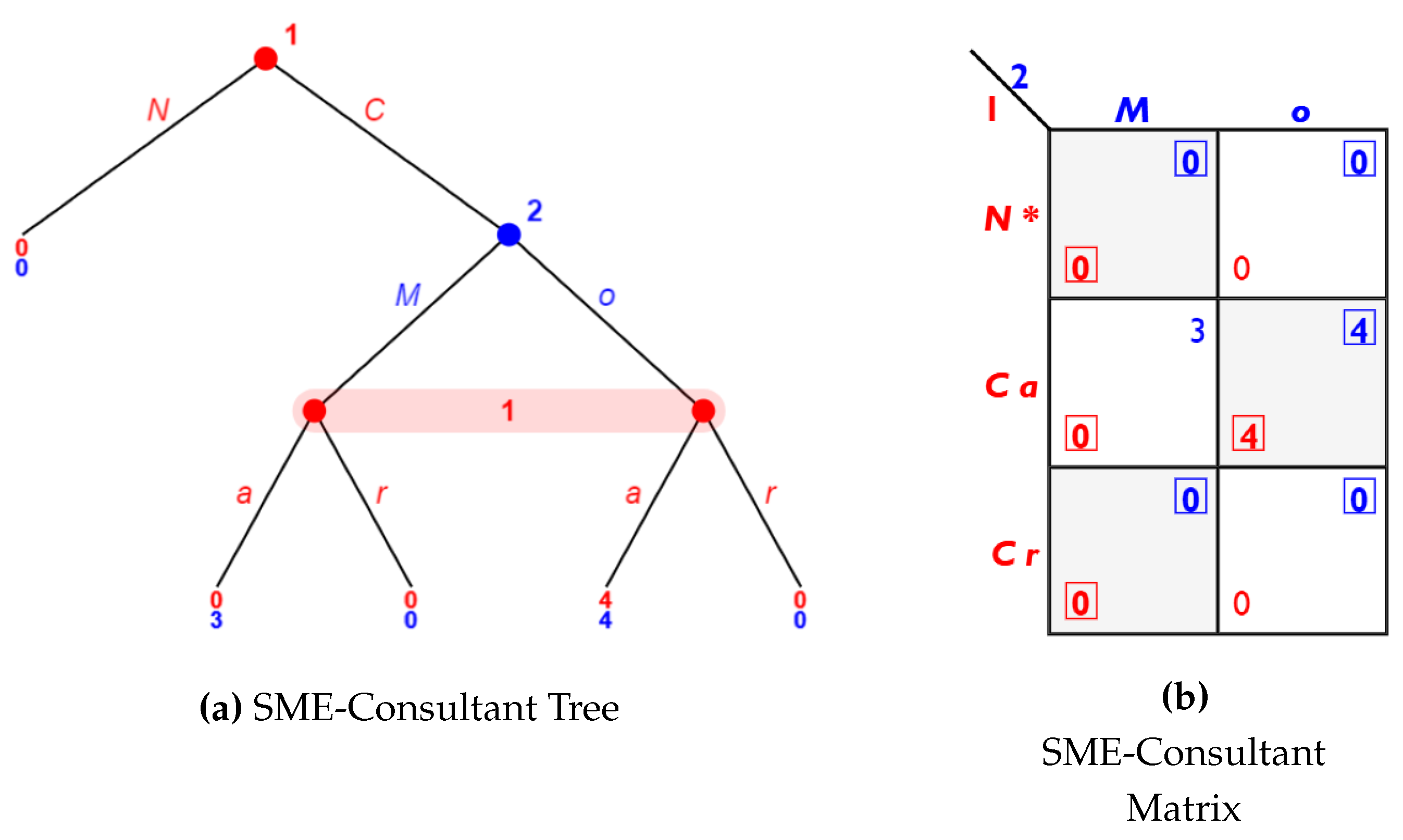

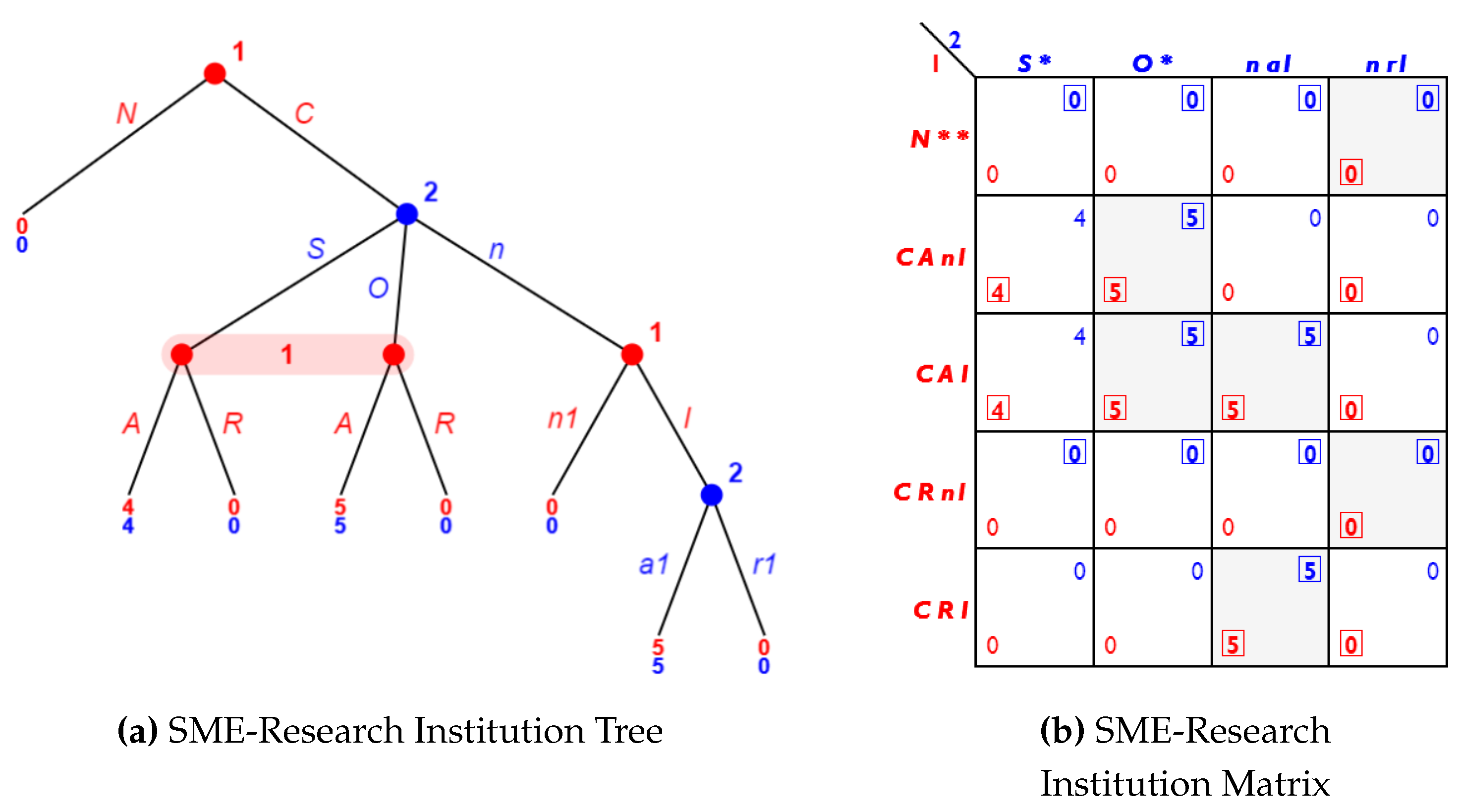

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 show extensive and strategic forms of the respective SME-consultant and SME-RI interactions generated in the game. In the first game, an SME can either create(C) or not create(N) a project. The consultant can respond by either proposing matchmaking with other users(M) or offering(o) to directly collaborate with the SME. Irrespective of the actual response from the consultant, the SME can either accept(a) or reject(r) the collaboration offer or the suggested matchmaking. For the second game, the SME either creates or does not create a project. The Research institution can respond by offering a collaboration(O), or offering a service(S) or do nothing(n). For the collaboration request or service request, SME can accept(A) or reject(R). However, if there is no response from the Research institution, the SME can either invite(I) the research institution to collaborate or not respond(n1). Still, the collaboration invitation from SME can either be accepted(a1) or rejected(r1) by the research institution.

The token outcomes (for the players) are assigned based on the task, partner recommendation gets fewer tokens than actual project collaboration. Long-term project collaborations get higher token rewards than short-term collaborations. An example of a long-term collaboration that receives a maximum token reward (5 tokens) is an SME collaborating with a research institution to execute an externally funded research project. A collaboration involving a research institution offering a service or a consultant offering consultation to an SME is considered a short-term collaboration with 4 token rewards for both parties. A recommender gets 3 tokens when a suggested match is accepted.

3.2.1. SME-Consultant Interactions

This paper formally represents the outcomes of the first game (G1) as terminal nodes that have non-zero outcomes for either of the players, where:

Combining Equation (

1) into equations(2) and (3)

The expected outcomes for Player1 and Player2 in G1 is given as follows:

Considering the probabilities of players 1 and 2 playing different strategies, equations (4) and (5) can be expanded as follows:

Equation (

1) represents the total tokens earned in G1 and equations (2) and (3) show the paths in the extensive game representation that resulted in either of the players earning a token. Equation (

4) and (5) shows the total tokens earned by each player which is represented by the summation of the payout paths where a token is received. Player 1, (as shown in eqn4), has only one path that results in a non-zero output, however, player 2 (as shown in eqn5), has two paths that result in a non-zero token reward. By integrating probabilities of a player playing (or not playing) a specific strategy, equations (4) and (5) are simplified further into equations (6) and (7) showing the tokens earned by each player. The simplified equations represent the total tokens earned by Player 1 and Player 2 which can then be used to simulate various expected outcomes of G1

3.2.2. SME-RI Interactions

For the second game (G2), the equations (1) to (7) are derived for the two players, where

and

represent the first and second players in the second game (G2) (see

Figure 3a). Equation (

1) of G2 is realised as Equation (

8).

Equations (2) and (3) are derived as equations (9), (10) and (11) in G2

Since

in G2, then

is used to represent either tokens earned by either player in G2. Hence, equations (4) and (5) are realized in G2 as Equation (

12).

Considering the following probabilities in G2

Equation (

6) and (7) is represented in G2 as Equation (

13)

3.3. Simulations of earned tokens by SME, Consultant and RI

Scenario-based simulations provide a logical space for estimating the actual amount of tokens earned by various users such as SMEs, research institutions and independent consultants. Furthermore, scenario-based simulation is also used in calculating the amount of tokens minted on the platform over a given amount of interactions between the various users in the collaboration platform. First, this paper shows the two scenarios used in simulating the G1 representing the interactions between SME and consultant and the expected token outcomes. Then, this paper shows the four scenarios used in simulating the G2 showing the interactions between SME and research institutions and the amount of tokens earned by the players. Lastly, based on these scenarios, this paper shows the upper and lower boundaries of expected tokens earned by combining outcomes from the two games for each player. The simulations are done over 20 repetitions of the games representing unique interactions between the players. This iteration is chosen because it is the minimum number of repetitions that will give token values of 1 or greater for all the considered simulation scenerios. This is because blockchain tokens are generally non-decimal.

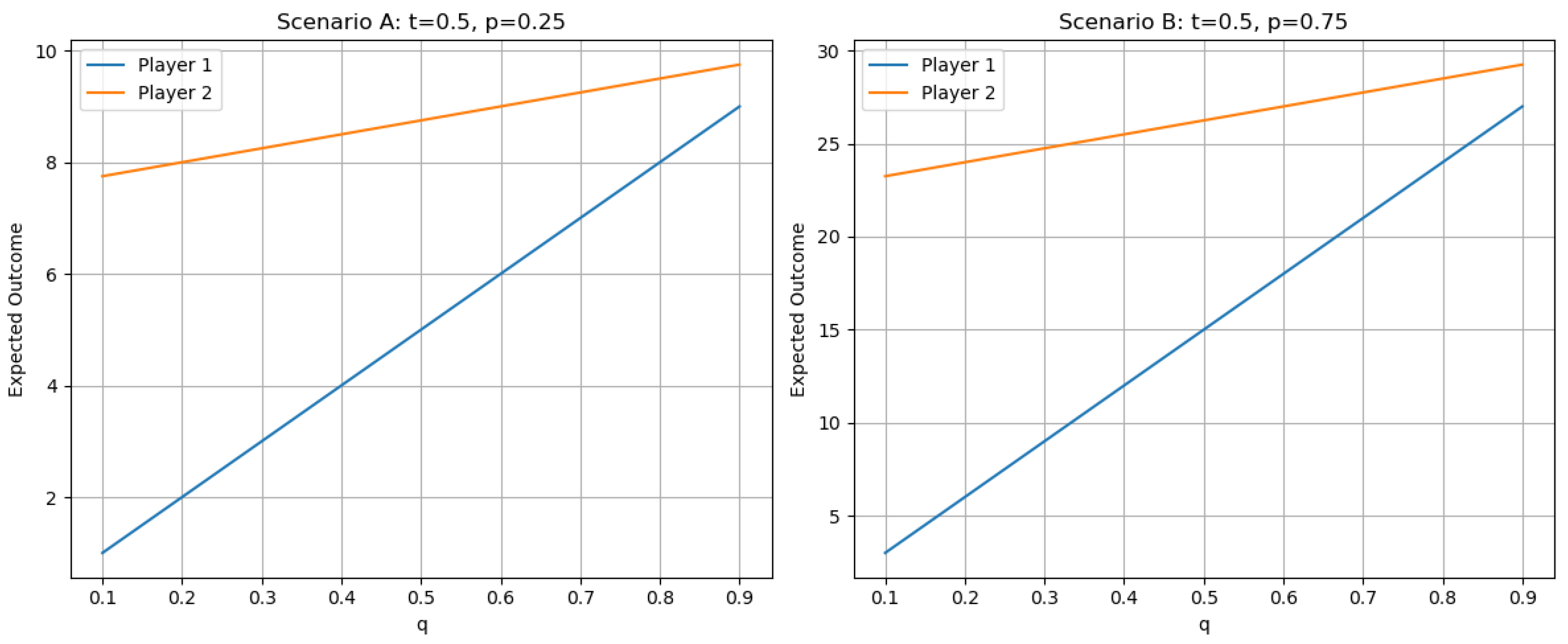

3.3.1. Applicable Scenarios and Simulation of G1

Equations (6) and (7) represent the total tokens earned by players 1 and 2 in the first game. Assuming that SMEs will accept requests from other parties solely based on their reputation and that at least half of the platform membership consists of reputable research institutions and consultants. Hence, the value can be assigned . In the first scenario, represents the situations where SMEs join the platform but are less likely to create project requests. In the second scenario, represents the situations where SMEs join the platform and are willing to create project requests. Both scenarios represent lower and upper quartiles of p. The equations (6) and (7) are then simulated for the values of q where . The assigned numbers represent various probabilities of the variables in the equations.

Figure 4 shows two diagrams representing the simulation of the two scenarios in G1. The left part shows the first scenario and the right part shows the second scenario. The lines in the figure represent the amount of tokens earned by each player of the two players in both scenarios. The blue line represents the earning potential of Player 1 (SME) and the red line shows the earning potential of Player 2 (Con) for the various probabilities of

q.

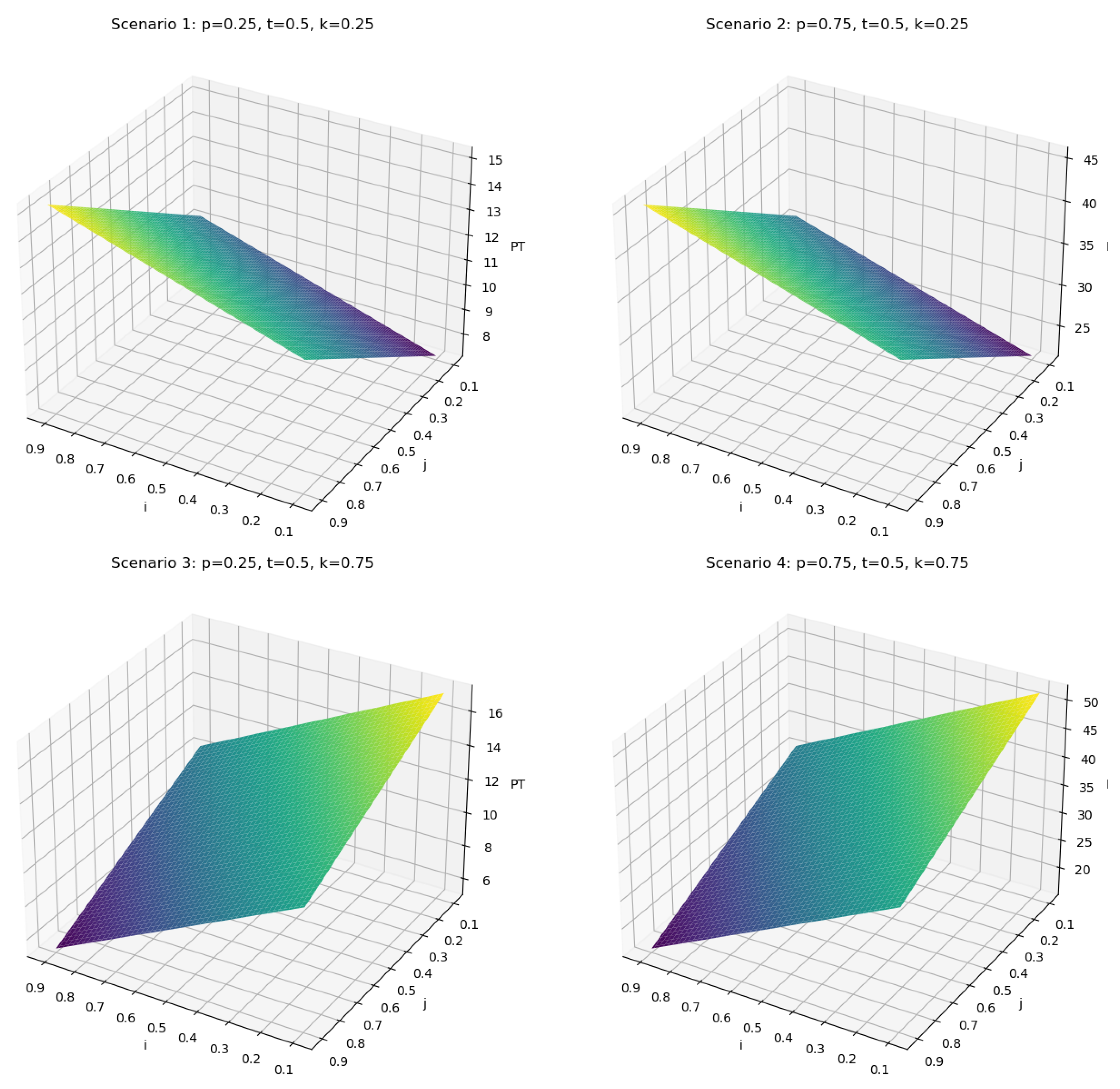

3.3.2. Applicable Scenarios and Simulation of G2

The same Equation (

13) is used to represent the earning potentials of player 1 and player 3 in the second game since their payout paths and token amounts earned are the same. Following the same earlier assumptions,

,

when SME doesn’t create many projects and vice-versa

. Since the relationship of SME inviting RI to collaborate and RI responding positively is linearly proportional, hence,

is represented in Equation (

13) and assigns the values of lower

and upper

quartiles to

k. Given these assigned values, four scenarios are possible- scenario 1:

,

,

, scenario 2:

,

,

, scenario 3:

,

,

and scenario 4:

,

,

. These four scenarios are simulated for the values

and

. The assigned numbers represent various probabilities of the variables in the Equation (

13).

Figure 5 contain four diagrams showing the four simulation scenarios described above. The diagrams show a 3d representation of estimated tokens earned by players 1 and 3 in the second game for the various probabilities of

i and

j.

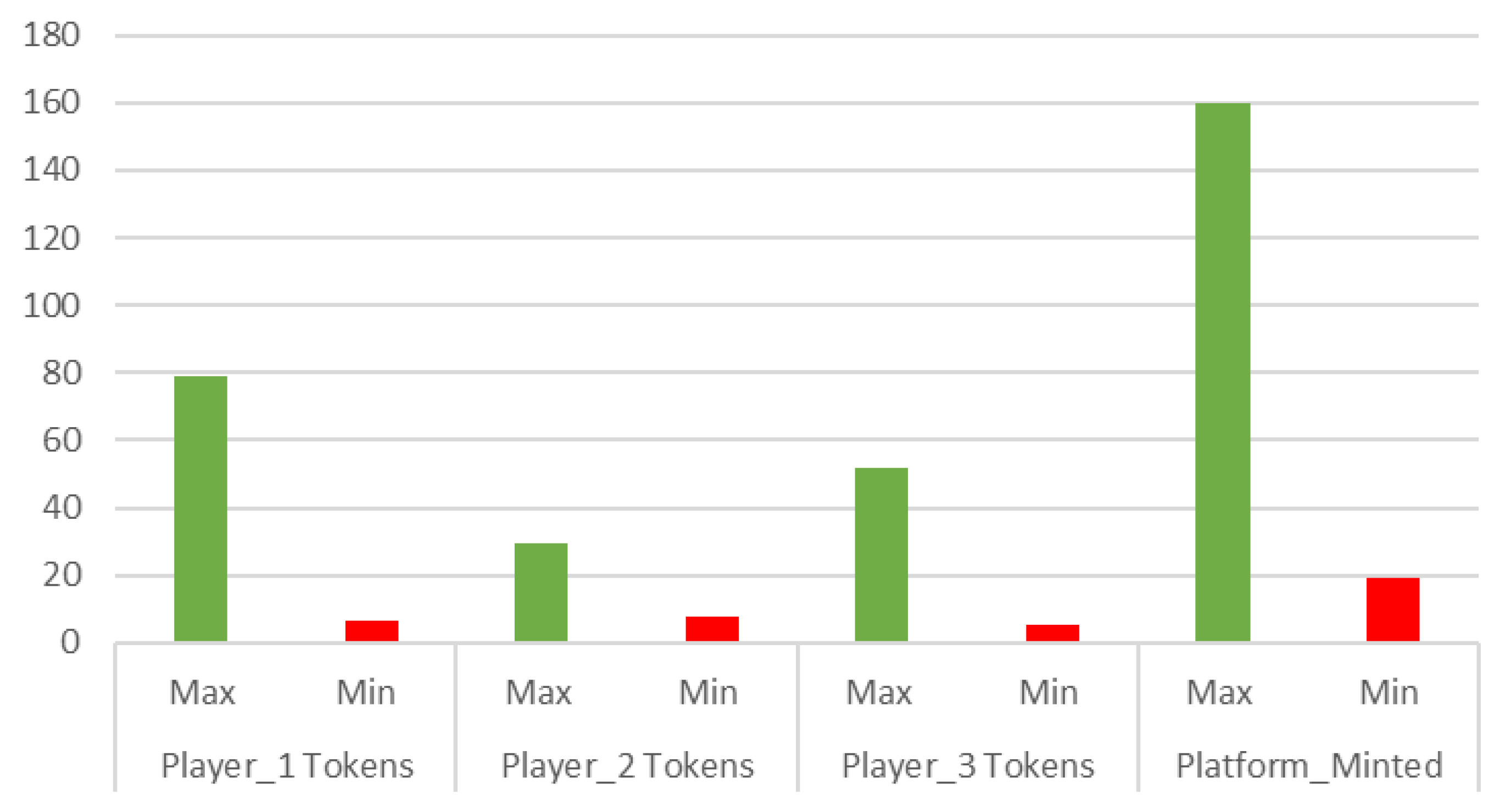

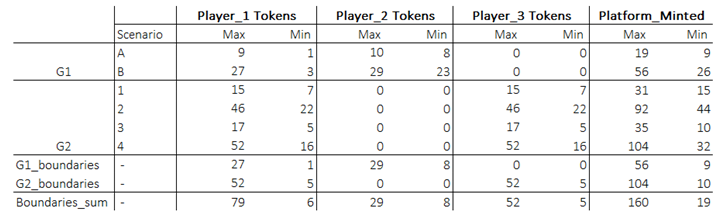

3.3.3. Boundaries of Estimated Tokens earned by Players

To estimate the upper and lower boundaries of tokens earned by the users and the total tokens minted on the platform, it is necessary to calculate the maximum and minimum amount of tokens earned by users for each game based on the developed scenarios.

Table 1 outlines the tokens earned for all the scenarios in the two games. The first column shows the first and second games,

G1 and G2. The second column shows the scenarios for each game. G1 has two scenarios A and B. While

G2 has four scenarios. The rest of the columns show the maximum and minimum tokens earned by each player (as well as the platform) for the listed scenarios.

GI_boundaries and

G2_boundaries are the row items for showing the maximum and minimum tokens earned in

G1 and

G2 respectively for all the scenarios in both games. For example, considering

player 1, for the scenarios in G1 (A and B), the minimum amount of tokens is in

Scenario A with the value of 1 and the maximum amount of tokens for G1 is in

Scenario B with the value of 27. For the

G2, the minimum amount of tokens for

player 1 is in the first scenario with the value of 5 and the maximum is in the fourth scenario with the value 52. Hence, the boundary values of player 1 are G1(27, 1) and G2(52, 5).

By Playing both games simultaneously, it is possible to estimate the minimum and maximum amount of tokens each player can earn for both games. For instance, player 1 earns tokens both in

G1 and

G2. The total amount of tokens minted by the platform can also be estimated over a given number of unique interactions between various types of users.

Boundaries_sum in the

Table 1 shows the estimated maximum and minimum amount of tokens for each player by summing the

GI_boundaries and

G2_boundaries. Therefore,

Figure 6, generated from

Boundaries_sum, represents the total possible tokens for each player and the platform that separately combines the minimum and maximum tokens earned in both games. Hence, the average token distribution on the platform can be estimated.

4. Dynamic Token Utility Model

This section describes the dynamic property of the token in the blockchain-enabled collaboration platform. First, this paper outlines the internal utility which the platform provides as the basis for deriving value for the token. Furthermore, this section of the paper shows the model formulation used in simulating the token pricing for the platform utility.

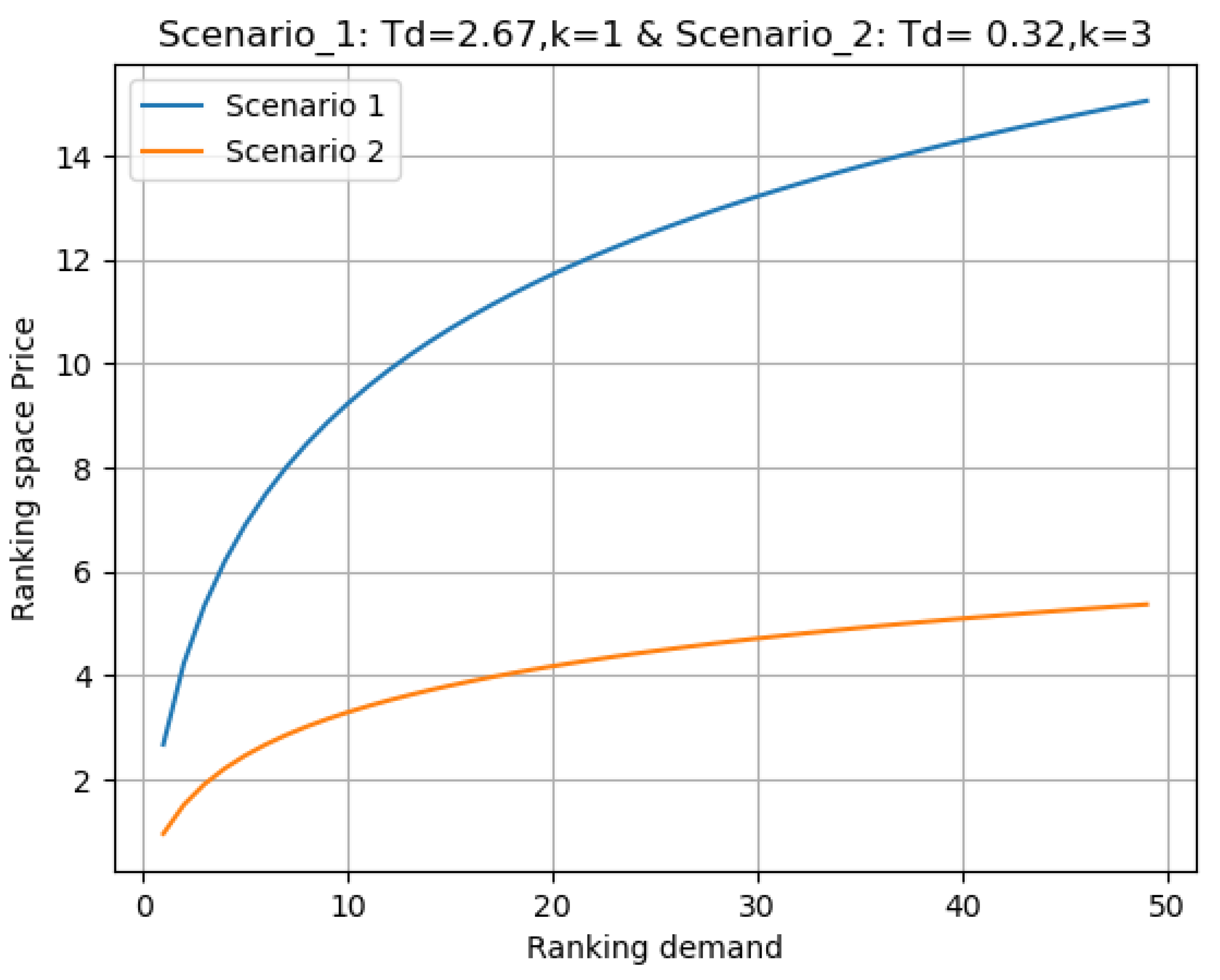

4.1. Ranking Space Utility

The utility of the collaborative platform token is realized using resources within the platform’s ranking space. Ranking space can be defined as a limited space resourced for highlighting important platform assets. Ranking space can be utilized to highlight users’ profiles or projects they created, hence, resulting in high visibility of users within the platform. The platform token can therefore be used to purchase the ranking space. Since the token is not backed by an external asset, the token reward amount for various activities (eg. matchmaking reward) does not necessarily need to be dynamic. However, the utility value of the token (pricing of ranking space) can be formulated to behave dynamically. Hence, the value of the tokens depends on the total supply of tokens within the platform based on the number of registered users (token distribution) and the demand for the actual ranking space by the users of the platform (ranking demand). To achieve a non-sharp rising price of the platform ranking space, a log function of the demand is adopted for ranking space. Then, the token distribution is used as the scaling factor for the price calculation. Too much token supply per the users on the platform will result in a higher price for the ranking space and vice versa. The logarithm value of ranking space demand provides minimal adjustments for the price for every additional user who wishes to buy the ranking space and the period (in days) in which the ranking space is intended to be purchased.

4.2. Ranking Space Dynamic Token Pricing Model

The following variables are relevant for modelling the dynamic pricing mechanism for the ranking space in the blockchain collaboration platform.

Where represents the token distribution on the platform which is the average amount of tokens in each user’s wallet based on the total tokens in circulation. Hence, can denote high and low token inflation on the platform. K represents the scaling factor, where the ranking price can be a multiple Given that the minimum-ranking space demand is such that there is only a single demand of ranking space for a single day , in that case, the demand for ranking space is . Therefore, the scaling factor K can determine the token price of ranking space relative to the average token balance in the users’ wallets.

4.3. Simulation of Ranking Space Dynamic Token Pricing Model

Two scenarios are considered to simulate the token pricing of the ranking space with respect to the platform users’ demand for ranking. The first scenario represents a high supply of tokens relative to the number of registered users and the second scenario represents a low supply of tokens relative to registered users. As earlier shown in

Figure 6, the max and min platform tokens, can be used to estimate the values of

. Given

. Hence

respectively for high and low token inflation. The scaling factor

is used in the second scenario to ensure

, even when ranking demand is 1 since the token value cannot be less than 1.

Figure 7 shows the token ranking price for values of ranking demand between 1 to 50. The blue and red lines show the estimated ranking price during high and low token inflation respectively.

5. Discussion

The discussions resulting from this work are presented in three themes. First is the general discussion of the result of this work, second is comparative discussions with related work and the third is token-related risks discussions and their mitigation strategies.

5.1. Results Discussions

Considering the three types of users of the platform, the result of the analyses conducted in this paper shows that SMEs have the most token outcomes. SME earns token from both interaction with Consultant and the Research institutions. However, with research institutions, the SME can earn the most tokens in the second game since they can perform long-term collaborations with research institutions and earn maximum rewards. This implies (based on the assumptions presented) that the SME is the main driver of the platform and the success of the platform highly depends on onboarding SME entities into the platform to create meaningful project requests that will result in actual collaboration. Hence, to drive and scale more interactions on the platform, an additional reward mechanism can be introduced to award tokens for users that invite verified SMEs to join the platform. Such a reward is claimed after the invited SME joins the platform and creates a project that results in actual collaboration.

In this paper, it is shown that the token earned in the platform can be used to access additional features provided within the platform such as the purchase of ranking space. This provides an opportunity for p2p trading the tokens among the participants in the platform. For instance, new users who join the platform can quickly gain visibility by purchasing tokens from other users and then using the tokens to highlight their profiles or projects which they seek collaboration for. One weakness of the p2p trading of tokens earned in the platform is determining the exchange rate. However, this challenge can be limited if the users have an overview of the token distribution within the platform to determine if there is high or low token inflation. Hence, they can set their prices accordingly. To further improve the utility value and demand for the platform, additional features can be introduced, to which the tokens will provide access. For instance, the tokens can be used for anti-spam prevention, especially for creating projects. However, this is outside the scope of the analyses conducted in this paper.

5.2. Results Comparative Discussions

One interesting contribution of this work is that it provides the first attempt to model token concepts of a DApp where the utility value of such tokens is independent of externally backed assets/resources using game theory. The research in [

17] shows that game theory is mostly applied in analyzing various threats and risks for consensus mechanisms in blockchain networks. The paper shows that common concepts such as mean-payoff and Nash equilibrium have been consistently adopted in minimizing threats posed by miners that create transaction blocks in the blockchain networks. The paper [

18] shows a game theory-based incentivization scheme applicable in consensus mechanisms for permissioned blockchain networks that don’t use cryptocurrencies. These other works [

19,

20] that applied game theory concepts in DApps, their tokens are backed by tangible assets such as energy and agricultural products. However, this work describes a non-cooperative game that formally describes the interactions between the different types of users in a blockchain collaboration to estimate their token outcomes. Furthermore, uses the aggregated expected outcomes for tokens minted on the platform to model a pricing mechanism for the utility to which the tokens provide access.

The self-sustaining token model designed and simulated in this paper provides an important step in addressing one of the challenges limiting the adoption of public blockchains within enterprises and business organizations. The previous work [

9] shows that the instability of cryptocurrencies mitigates organizations’ willingness to use blockchain applications irrespective of the numerous benefits they provide. The token model designed in this paper shows organisations can use blockchain applications without being exposed to the complexities of cryptocurrencies (publicly traded tokens). With the advances in blockchain technologies such as Layer 2 scaling solutions for reduced on-chain transaction costs[

21], multi-signature transaction fee donations in smart contracts[

22], and self-sustaining token model designed in this paper, administrators or owners of blockchain applications can run the platform as a regular application without passing any transaction fees cost to the users. Hence, the business model of such platforms solely depends on the utility values provided by the tokens and are only used within the platform.

5.3. Token Risks and Mitigation Strategies

One of the common applications of game theory in dynamic economic systems is identifying and understanding risks relevant to such systems. Collusion is the main threat that can be exploited in the token system designed in this paper. This is because individual actors cannot exploit the collaboration platform unless they collude to act maliciously. The threat of collusion can be exploited in two ways. First, assuming a single bad actor, an SME for instance, spams the platform with several projects to earn tokens. When the rest of the users act in good faith, neither a consultant nor a research institution will recommend a match or propose collaboration with such an SME. However, when either of these two parties collude, they can collaborate and complete such spam projects just to earn tokens. Secondly, seeing that most token outcomes occur when an SME collaborate with research institutions for a long-term project, an SME can easily reject collaboration requests and match recommendations from a consultant while only accepting collaborations from a user type of research institution. The former leads to the risk of token reward manipulation while the latter leads to the risk of token inflation. Hence, token reward manipulation occurs when users trick the system into earning tokens and token inflation occurs when users trick the system into minting too many tokens in the platform.

These risks also impact the ranking space utility which the token value is based upon. With too many tokens in circulation, but mostly in the wallet of malicious users, legitimate users with limited tokens can’t access important services provided in the platform such as ranking space utility. This is because the resulting token price for the ranking space will be much higher than the average tokens in the users’ wallets. One way to protect the platform from these types of risks that exploit colluding actors is to introduce the concept of decentralized auditors [

23]. Such auditors can randomly select projects to check if they are spam and if the collaboration outcomes are influenced by collusion. The decision of these auditors can be based on majority voting[

24] and the selection of auditors randomised within the platform users. Malicious colluders when detected, will result in reduced reputation points or outright banning. However, introducing auditors within the platform also raises privacy concerns. The auditors will have access to project documents, which most of the collaborators will rather prefer to remain private within the collaborating parties. Still, with proper KYC and onboarding only legitimate organizations and entities within the platform, the threat of collusion and resulting risks are greatly reduced.

6. Conclusions

The goal of this paper is to design a self-sustaining token model for incentivising collaboration between SMEs, Research institutions and Consultants in the execution of research projects on a blockchain-based research collaboration platform. To achieve this objective, this paper explored the use of game theory to formally model token-based interactions between the various entities and user groups in the blockchain collaboration platform. Scenarios-based simulations are applied to derive the boundaries of expected token outcomes for the platform users. Also, the scenario-based simulation approach is applied to estimate the maximum and minimum tokens minted on the platform over a specified number of interactions between the platform users. Furthermore, a dynamic token utility model based on ranking space utility is introduced to provide a pricing mechanism from which the token derives its value without depending on externally backed assets. The ranking space utility provides a means for users to highlight their profiles and projects to quickly gain visibility on the platform. This ensures quicker matches and recommendations for project collaborations and executions. The token pricing model is simulated using the initially derived platform’s expected token outcomes (tokens minted) representing high and low inflation scenarios to show the prices of ranking space utility for these two scenarios. Lastly, the paper discusses the simulation results, potential collusion threats, and risks (such as token inflation and reward manipulations) in the designed token model and their mitigation strategies. The main contribution of this work is that it provides the first attempt to design a self-sustaining token model for blockchain applications using game theory. Hence, the methods and results from this work provide the basis for other researchers to design token systems for DApps that enable inter-organizations where the instability of cryptocurrencies has mitigated the adoption of blockchain systems within business organizations.

Limitations and Future Work

The main limitation of this work is that the token model developed in this paper using game theory concepts is limited by the assumption of two-way interactions between SME & Consultant and SME & Research institution for project executions. However, a research project collaboration can involve multiple types of each entity and simulating such complex interactions will be difficult to realize with the approach adopted in this paper. Another limitation of this work is that the simulation results derived from this work are bounded within the scope of the scenarios applied. While this shows the development of a self-sustaining token model for inter-organizational collaborations in research project executions, the methods and concepts used in this paper can be applied to other use cases of blockchain-based inter-organizational collaborations. A practical future work emerging from this research is to apply the approaches used in this paper to other cases of inter-organisational collaborations. Hence, develop a self-sustaining token model framework for DApps that enables organizational collaborations on the blockchain.

Funding

This work is fully funded by the EU and Austrian FFG grant for the development of Cyber-physical Systems European Digital Innovation Hub (CPS-EDIH).

Acknowledgments

Special appreciation goes to colleagues from the Austrian Blockchain Center Research, who contributed to the development of the blockchain research project collaboration platform which the designed token model is based upon.

References

- Pertuze, J.A.; Calder, E.S.; Greitzer, E.M.; Lucas, W.A. Best practices for industry-university collaboration. MIT Sloan Management Review 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nsanzumuhire, S.U.; Groot, W. Context perspective on University-Industry Collaboration processes: A systematic review of literature. Journal of cleaner production 2020, 258, 120861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Jeyaraj, A.; Hughes, L.; Davies, G.H.; Ahuja, M.; Albashrawi, M.A.; Al-Busaidi, A.S.; Al-Sharhan, S.; Al-Sulaiti, K.I.; Altinay, L.; others. “Real impact”: Challenges and opportunities in bridging the gap between research and practice–Making a difference in industry, policy, and society, 2024.

- Andersson, G.; Haque, A. Unlocking Open Innovation: The Role of Resources & Capabilities in Swedish High-Tech SMEs, 2024.

- Udokwu, C.; Norta, A. Deriving and formalizing requirements of decentralized applications for inter-organizational collaborations on blockchain. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering 2021, 46, 8397–8414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carminati, B.; Ferrari, E.; Rondanini, C. Blockchain as a platform for secure inter-organizational business processes. 2018 IEEE 4th International Conference on Collaboration and Internet Computing (CIC). IEEE, 2018, pp. 122–129.

- Rondanini, C.; Carminati, B.; Daidone, F.; Ferrari, E. Blockchain-based controlled information sharing in inter-organizational workflows. 2020 IEEE International Conference on Services Computing (SCC). IEEE, 2020, pp. 378–385.

- Swan, M. Blockchain: Blueprint for a new economy; " O’Reilly Media, Inc.", 2015.

- Udokwu, C.; Kormiltsyn, A.; Thangalimodzi, K.; Norta, A. The state of the art for blockchain-enabled smart-contract applications in the organization. 2018 Ivannikov Ispras Open Conference (ISPRAS). IEEE, 2018, pp. 137–144.

- Coelho, R.; Braga, R.; David, J.M.; Dantas, M.; Stroele, V.; Campos, F. Integrating blockchain for data sharing and collaboration support in scientific ecosystem platform 2021.

- Alniamy, A.M.; Liu, H. Blockchain-based secure collaboration platform for sharing and accessing scientific research data. 2020 3rd International Conference on Hot Information-Centric Networking (HotICN). IEEE, 2020, pp. 34–40.

- Unalan, S.; Ozcan, S. Democratising systems of innovations based on Blockchain platform technologies. Journal of Enterprise Information Management 2020, 33, 1511–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sampaio, P.; Pishchulov, G.; Mehandjiev, N.; Cisneros-Cabrera, S.; Schirrmann, A.; Jiru, F.; Bnouhanna, N. The architectural design and implementation of a digital platform for Industry 4.0 SME collaboration. Computers in Industry 2022, 138, 103623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idelberger, F.; Governatori, G.; Riveret, R.; Sartor, G. Evaluation of logic-based smart contracts for blockchain systems. Rule Technologies. Research, Tools, and Applications: 10th International Symposium, RuleML 2016, Stony Brook, NY, USA, July 6-9, 2016. Proceedings 10. Springer, 2016, pp. 167–183.

- Oliveira, L.; Zavolokina, L.; Bauer, I.; Schwabe, G. To token or not to token: Tools for understanding blockchain tokens. ICIS, 2018.

- Savani, R.; Von Stengel, B. Game Theory Explorer: software for the applied game theorist. Computational Management Science 2015, 12, 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Luong, N.C.; Wang, W.; Niyato, D.; Wang, P.; Liang, Y.C.; Kim, D.I. A survey on applications of game theory in blockchain. arXiv preprint 2019, arXiv:1902.10865 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Liu, Q.; Wu, S.; Cao, Z.; Bai, Q. Game theory based compatible incentive mechanism design for non-cryptocurrency blockchain systems. Journal of Industrial Information Integration 2023, 31, 100426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniruzzaman, M.; Yassine, A.; Benlamri, R. Blockchain and cooperative game theory for peer-to-peer energy trading in smart grids. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2023, 151, 109111. [Google Scholar]

- Song, L.; Luo, Y.; Chang, Z.; Jin, C.; Nicolas, M. Blockchain adoption in agricultural supply chain for better sustainability: A game theory perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sguanci, C.; Spatafora, R.; Vergani, A.M. Layer 2 blockchain scaling: A survey. arXiv preprint 2021, arXiv:2107.10881 2021. [Google Scholar]

- OpenZeppelin. OpenZeppelin GSN (2.x) Documentation, 2024. Accessed: 2024-08-09.

- Bonyuet, D. Overview and impact of blockchain on auditing. International Journal of Digital Accounting Research 2020, 20, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebtehal Nassar, etal,. Design Patterns For Sharing Economy Within Blockchain-based Community Systems: A Technical Report. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382398779_Design_Patterns_For_Sharing_Economy_Within_Blockchain-based_Community_Systems_A_Technical_Report (accessed on 20 July 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).