Submitted:

11 February 2025

Posted:

11 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

- Most solutions used existing wireless communication protocols, specifically ISA100 Wireless or Wireless HART.

- Applications using wireless communication focus primarily on monitoring and data collection from sensors, with less emphasis on control.

- Both mentioned protocols effectively address monitoring; however, the control aspect is problematic as resulted from the conclusions of the assessed papers.

- Delays and limitations regarding data transmission periods were observed, which can cause instability in industrial process control.

- Some studies implemented additional functionalities to the standards to eliminate or at least mitigate the effects of these delays.

- The authors of these papers conclude that using wireless communication in a control loop is possible but not recommended for fast processes.

2. Materials and Methods

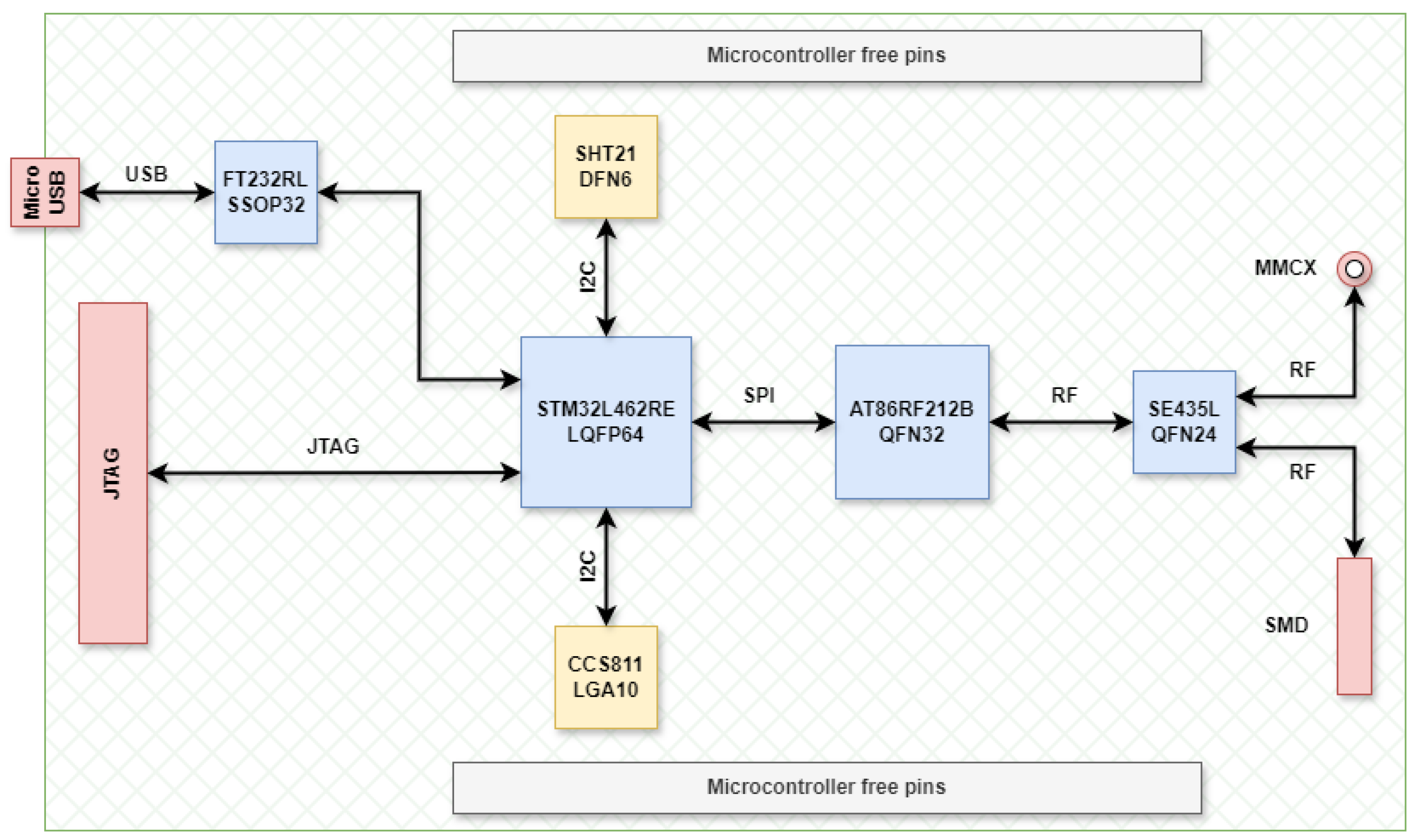

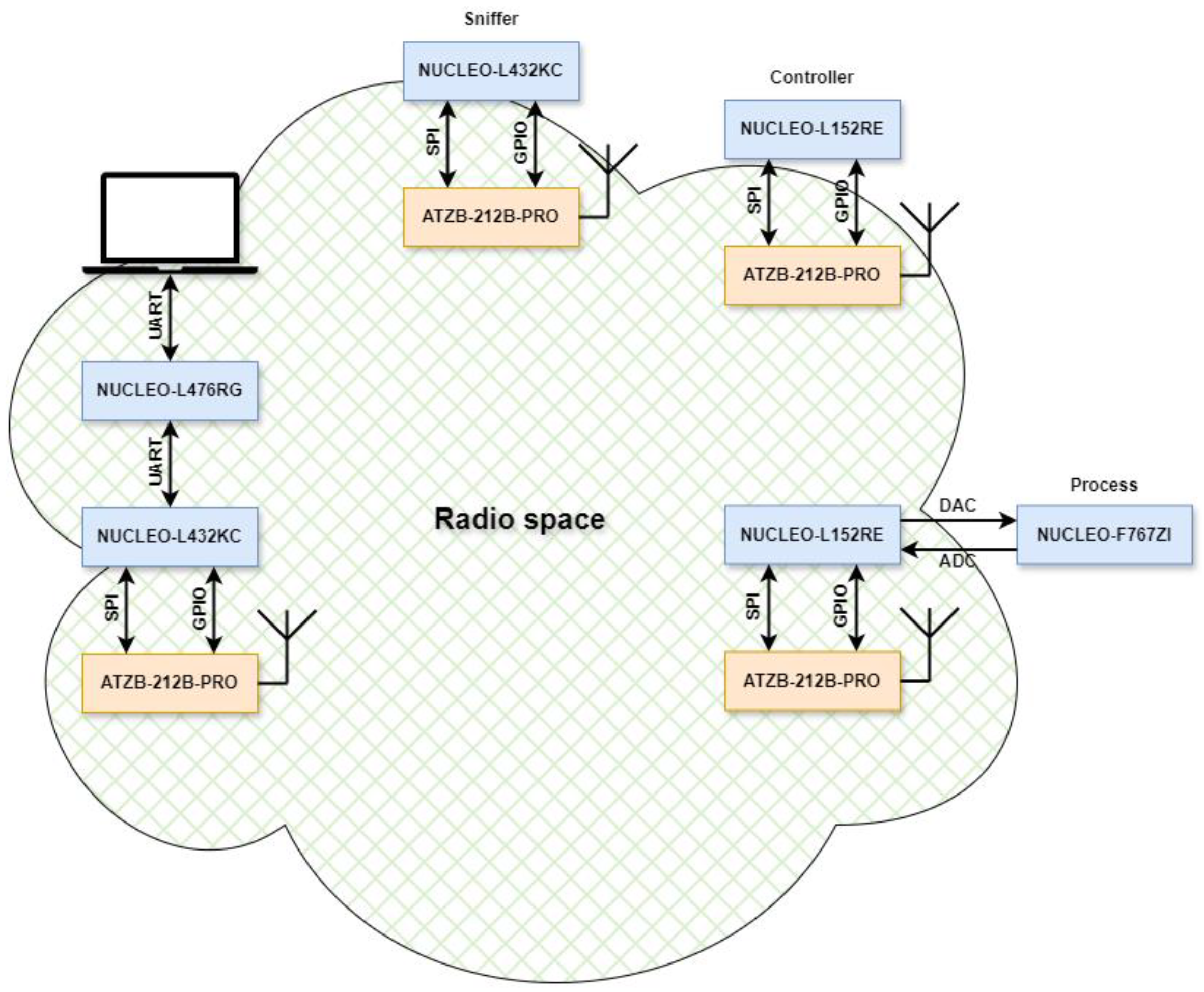

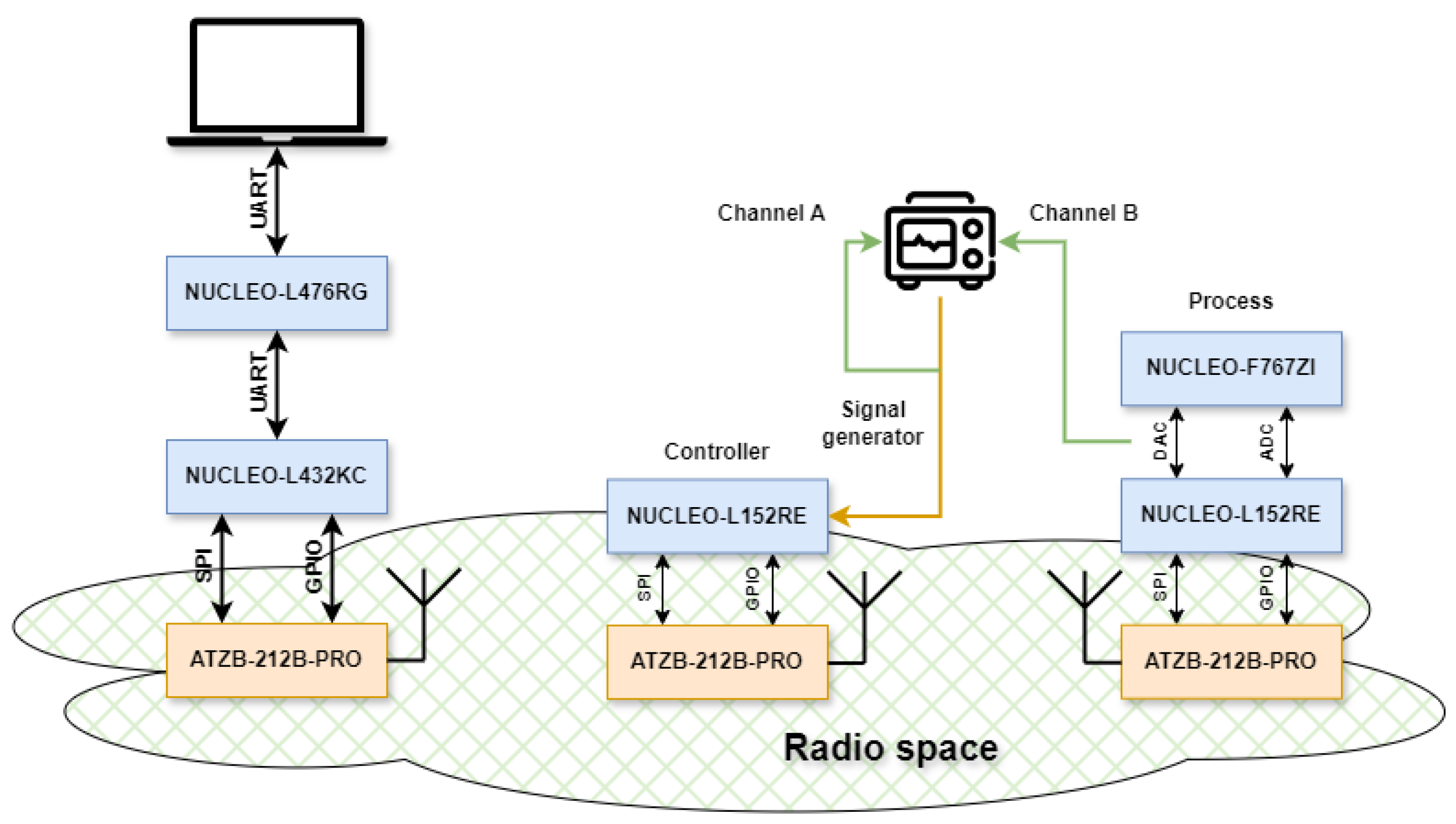

2.1. Hardware and Software Resources

- Identification of the requirements necessary for the proper operation of a WCN

- Identifying the hardware support for the deployment of the WCN

- Identifying the software support for the implementation of the WCN. To achieve objectives, the use of the latest hardware and software technologies available on the market was chosen.

- The identification of the hardware and software support of the WCN has been done using literature, comparative studies between different technologies, component manufacturers and available software solutions.

2.2. Development System Design

- Identifying the hardware components of the development system

- Design of the development board used for the development of the WCN

- Production of at least two development boards

- Power testing and validation of the development board functionalities

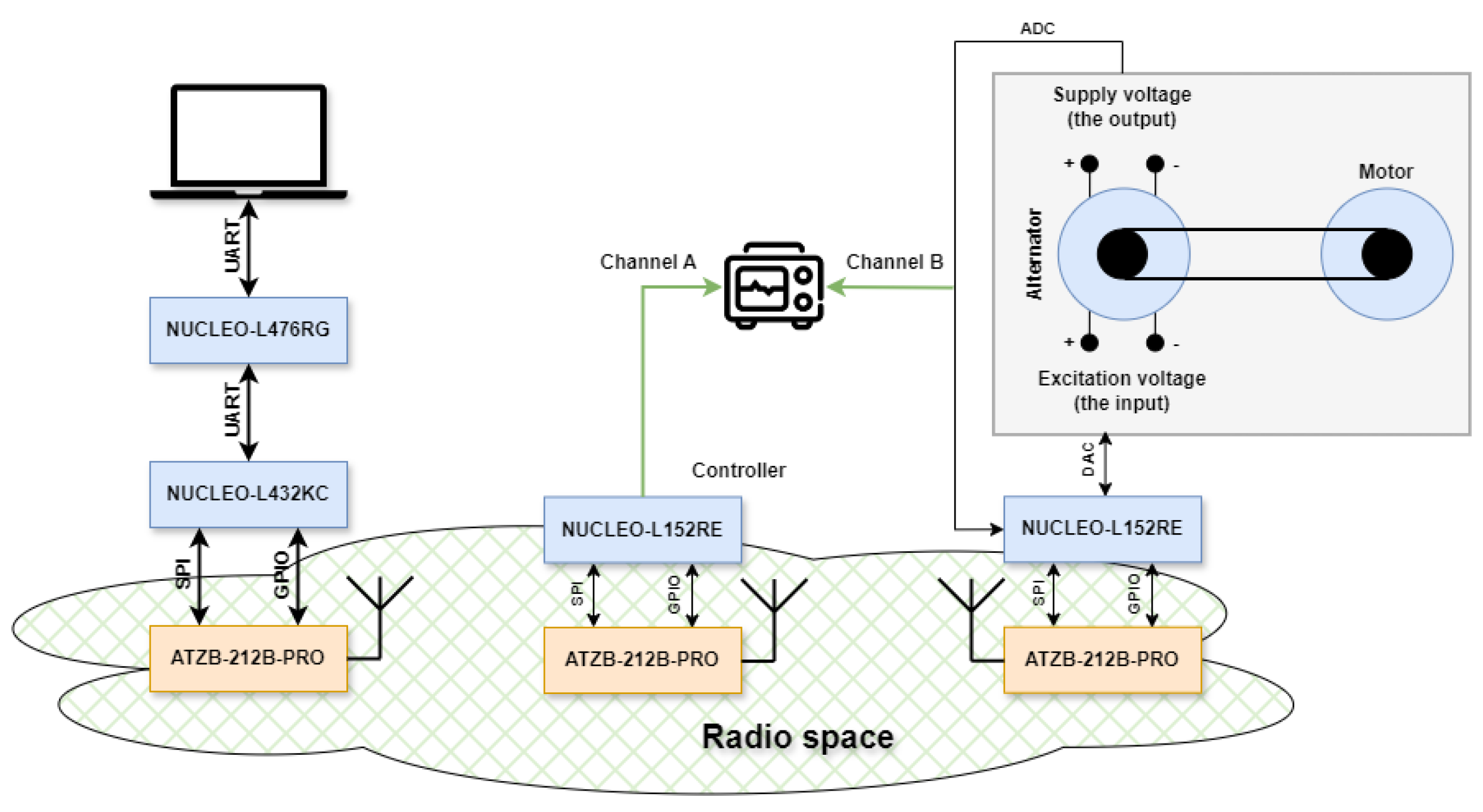

2.3. The Wireless Control System

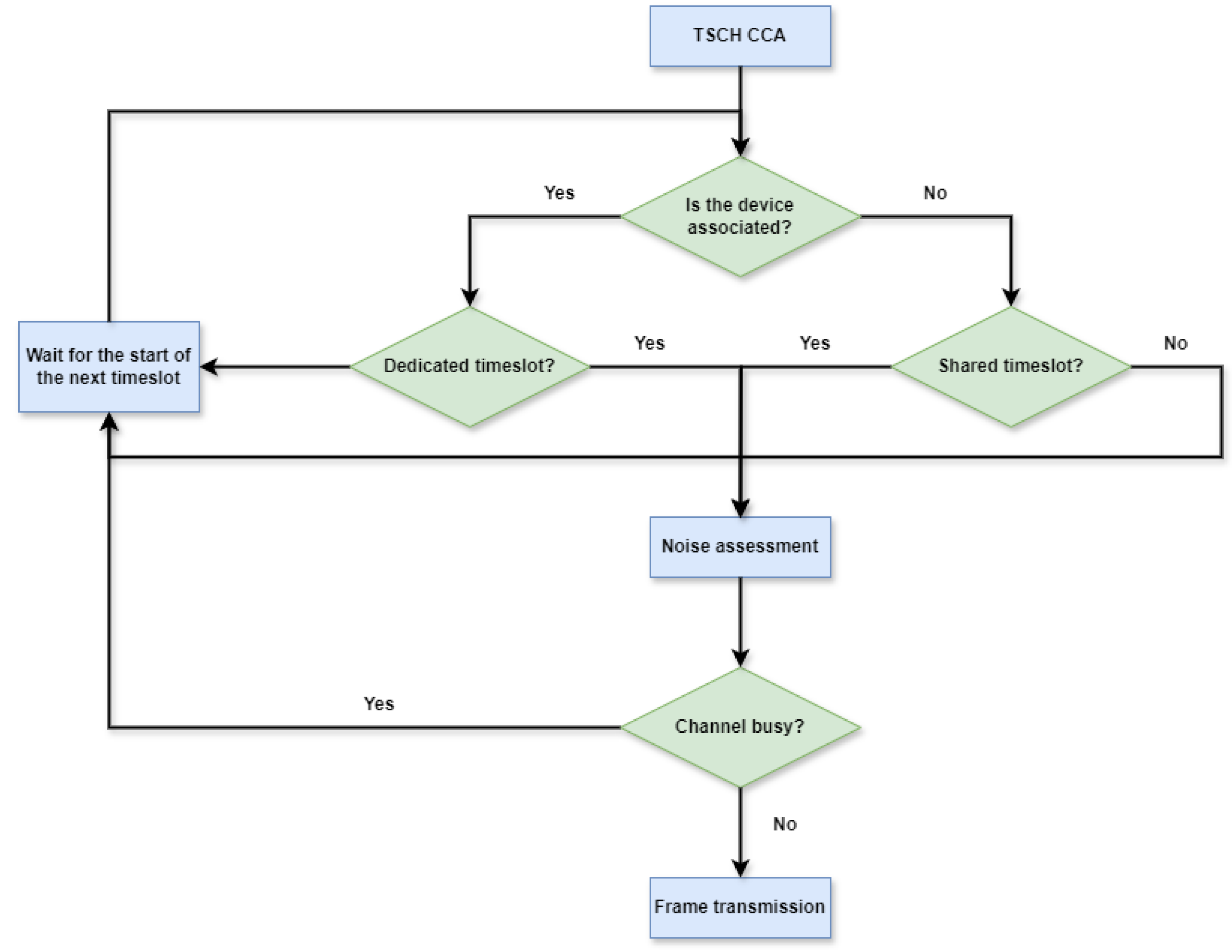

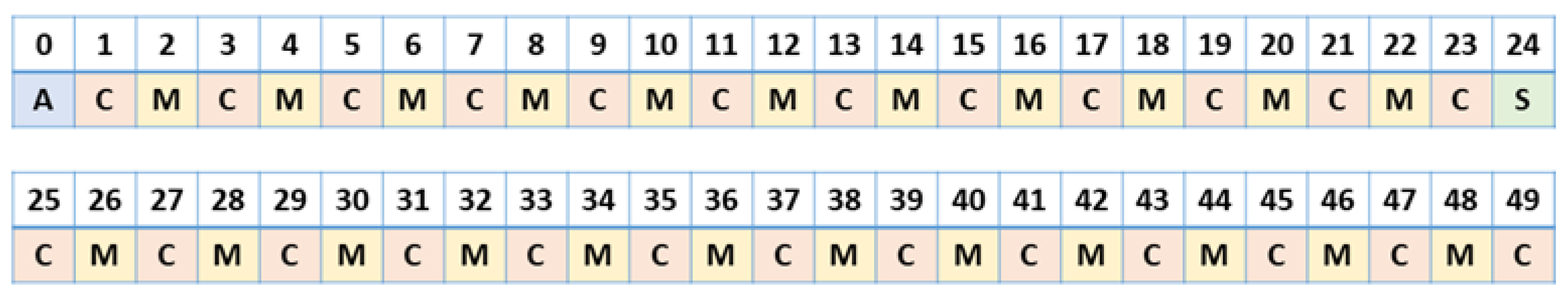

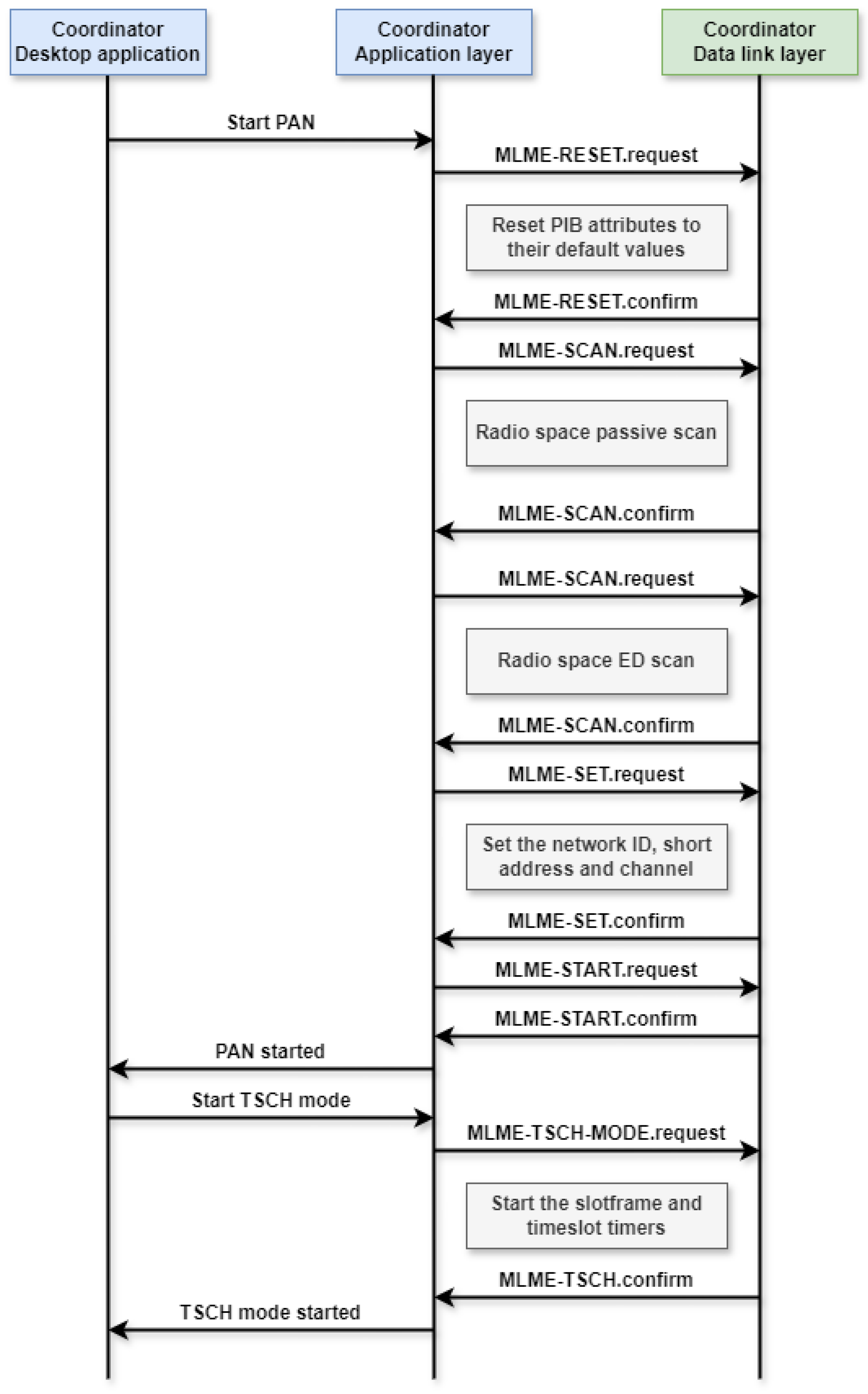

- Implementation of the functionality required for the TSCH (Time Slotted Channel Hopping) mode of operation of the wireless network, as defined by the IEEE 802.15.4-2020 standard.

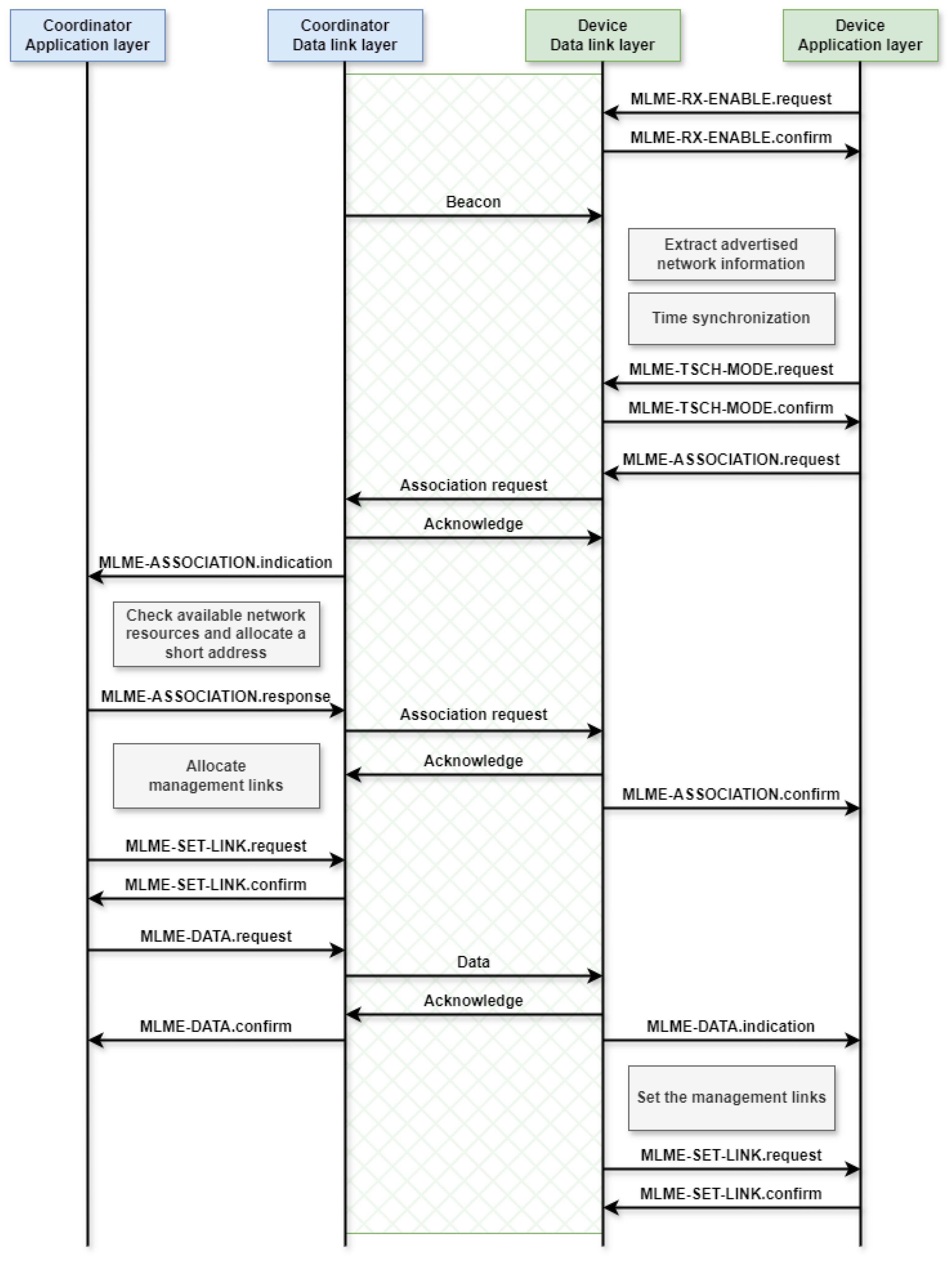

- Allocation of communication slots for devices associated with the network.

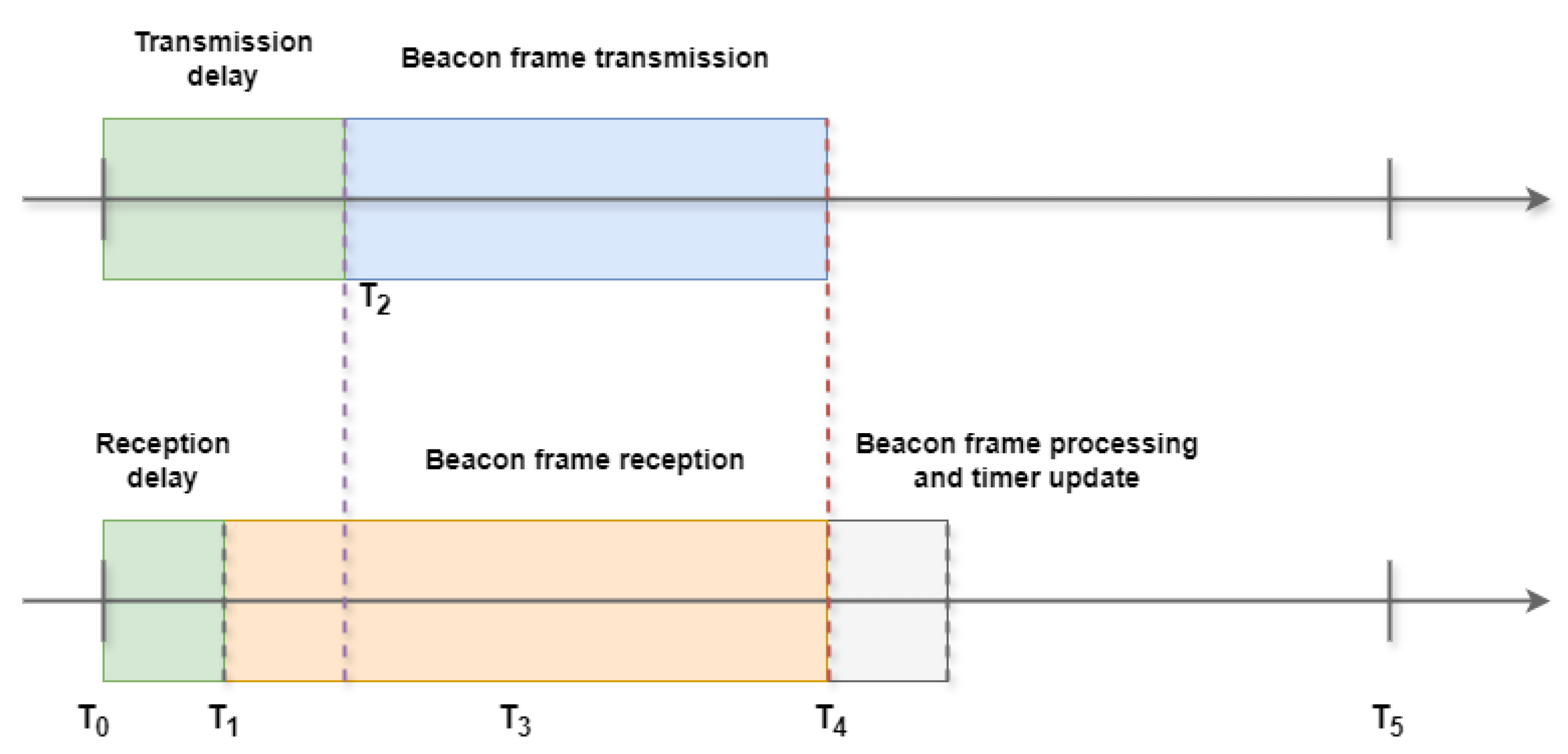

- Time synchronization of devices associated with the network.

3. Wireless Control Network Requirements

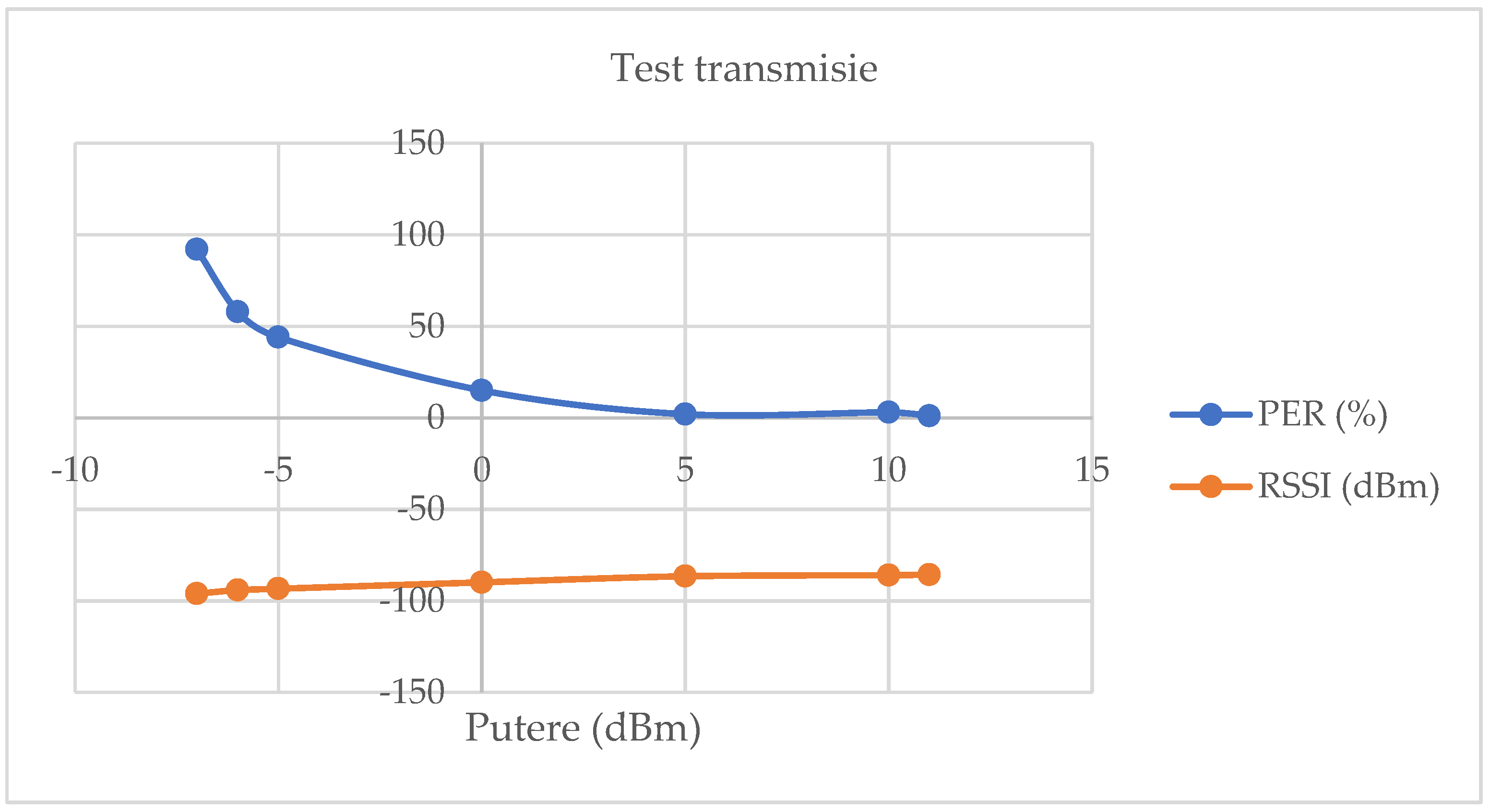

- The wireless network will be designed in such a way as to allow control of both slow and fast processes. From a process point of view, a latency below 100 milliseconds is required.

- The latency between two nodes in a wireless network with a mesh topology is dependent on the number of levels between the two nodes. Thus, if a control loop is desired using two nodes in the network, those two nodes must communicate directly without the communication link being handled by the network coordinator. The wireless network must support point-to-point communication between any two nodes.

- Redundancy is needed to guarantee continuous process control if the wireless communication between the node measuring the process output and the node calculating the command no longer works properly. Current wireless protocols only provide redundant routes through router nodes.

- Interference can cause the control loop to operate incorrectly. Using an operating frequency less common in wireless communication, such as 868 MHz, along with frequency hopping, minimizes this risk and maximizes noise resistance.

- A high data transfer speed is recommended to ensure low latency.

- Time synchronization between wireless network components must be accurate. Desynchronization leads to incorrect operation of the control system.

4. Design of the Development System

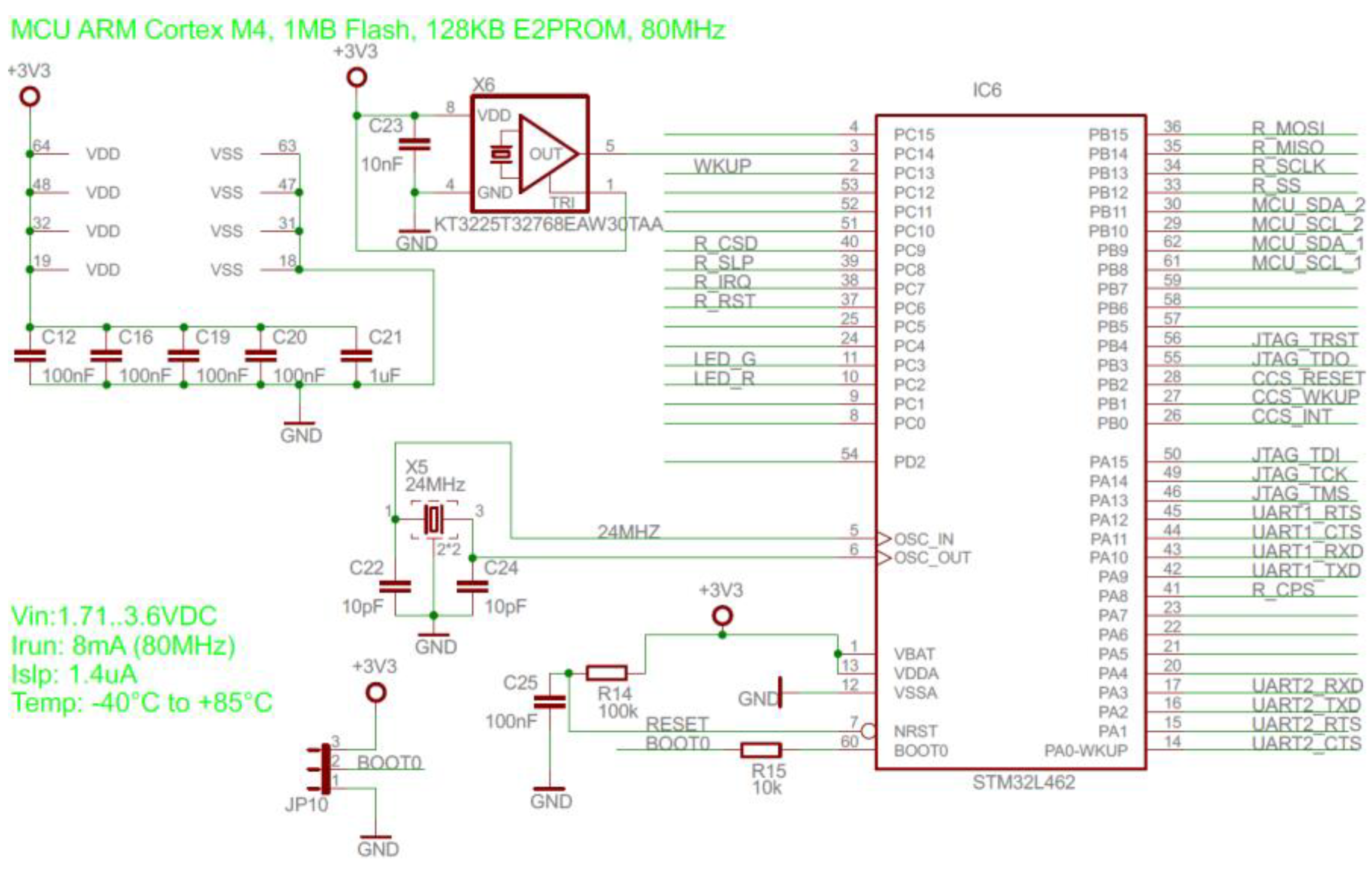

4.1. Microcontroller

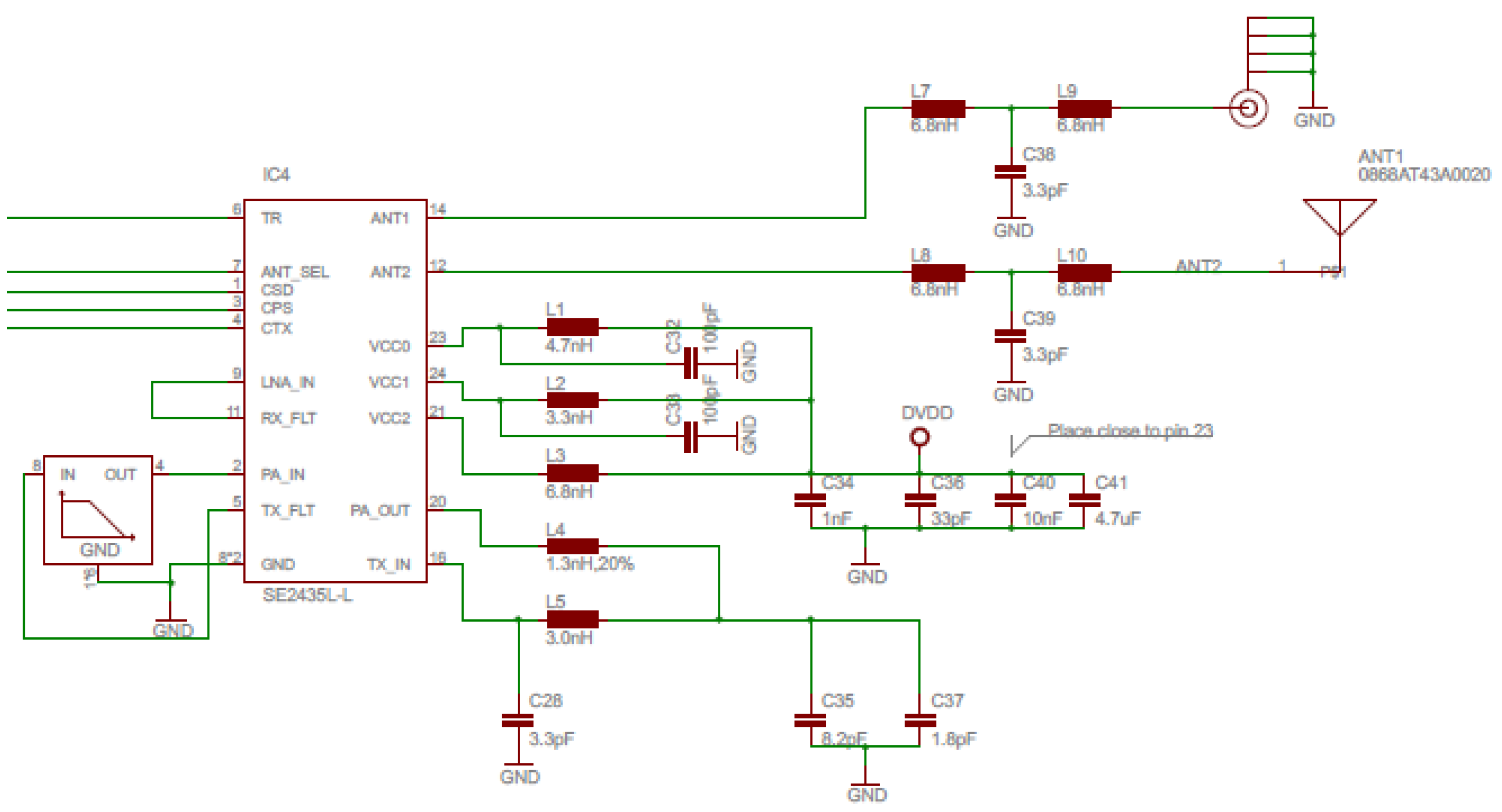

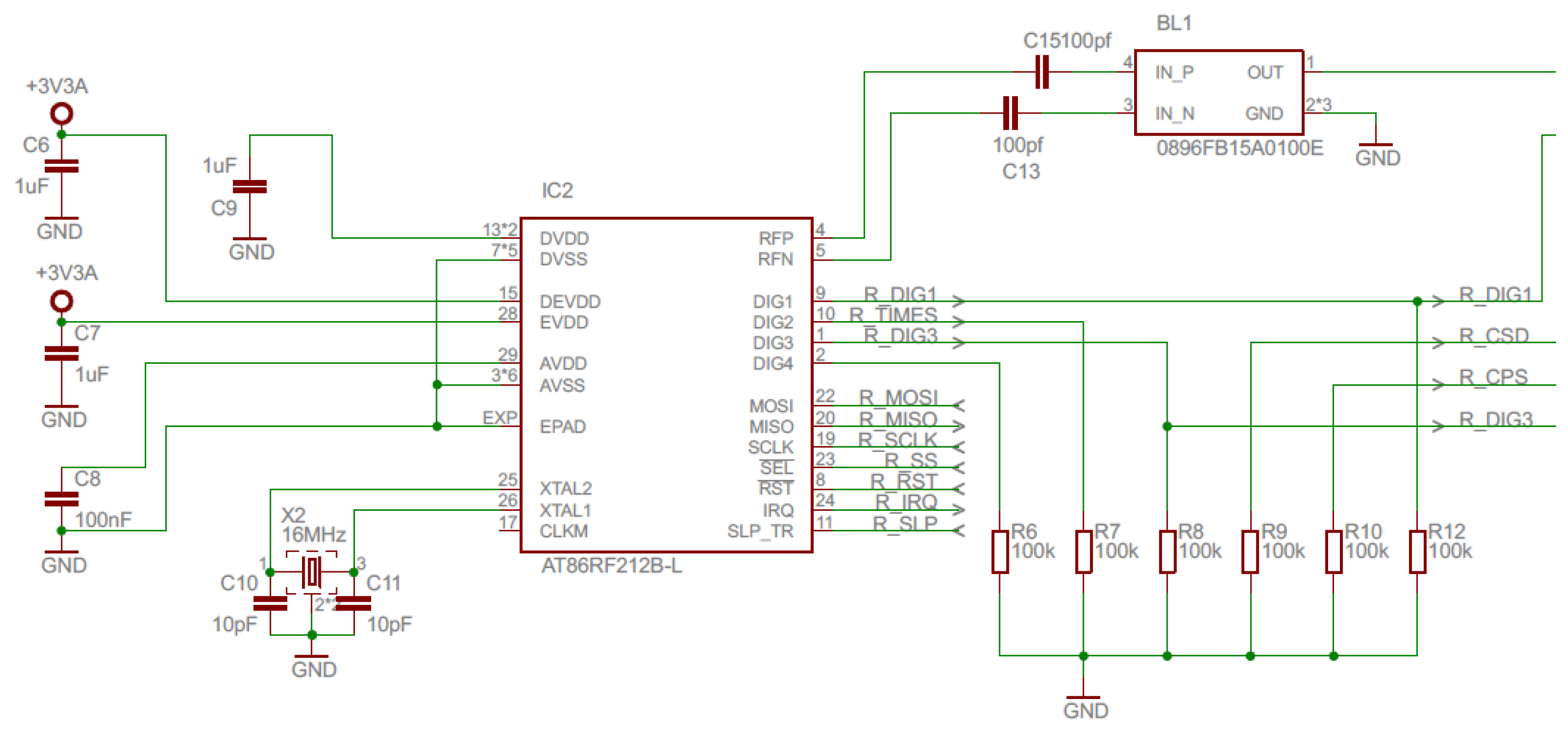

4.2. Transceiver

- A serial communication interface that is typically SPI.

- A pin used by the transceiver to generate interrupts and thus notify the microcontroller that a state change has occurred.

- A reset pin through which the microcontroller resets the transceiver – the internal registers are set to their default values.

- Optionally, a pin through which the microcontroller sets the transceiver to low power mode.

| Transceiver | Microchip AT86RF212B | Texas Instruments CC110L | STMicroelectronics S2-LP |

| Frequency bands (MHz) | 779 – 787 863 – 870 920 – 928 915 – 930 |

300 – 348 387 – 464 779 – 928 |

430 – 470 860 – 940 |

| Modulations | BPSK O-QPSK |

2-FSK 2-GFSK 4-FSK 4-GFSK OOK MSK |

2-FSK 2-GFSK 4-FSK 4-GFSK OOK ASK |

| Data rate (kbps) | 20 ÷ 1000 | 0.6 ÷ 600 | 0.1 ÷ 500 |

| Sensitivity (dBm) | -100 | -95 | -101 |

| Maximum power (dBm) | +11 | +12 | +16 |

| Power increment (dBm) | 1 | Variable | 0.5 |

| Consumption | |||

| Sleep (nA) | 200 | 200 | 950 |

| Idle (µA) | 450 | 1700 | 420 |

| RX (mA) | 9.2 | 14.6 | 8.6 |

| TX (mA) | 26.5 @ +10 dBm | 30 @ +10 dBm | 11 @ +10 dBm |

| FIFO length (bytes) | 128 | 64 | 128 |

| Operating temperature | -40 ÷ +85 | -40 ÷ +85 | -40 ÷ +105 |

| RSSI | X | X | X |

| Antenna diversity | X | - | X |

| CCA | X | X | X |

| IEEE 802.15.4 | X | - | X |

| ETSI EN 300 220 | X | X | X |

4.3. Development Board

- 25 mW or 14 dBm in the K, L, M, N, O, and R bands

- 500 mW or 27 dBm in the P-band

- 5 mW or 7 dBm in the Q band

5. Implementation of the Wireless Control Network

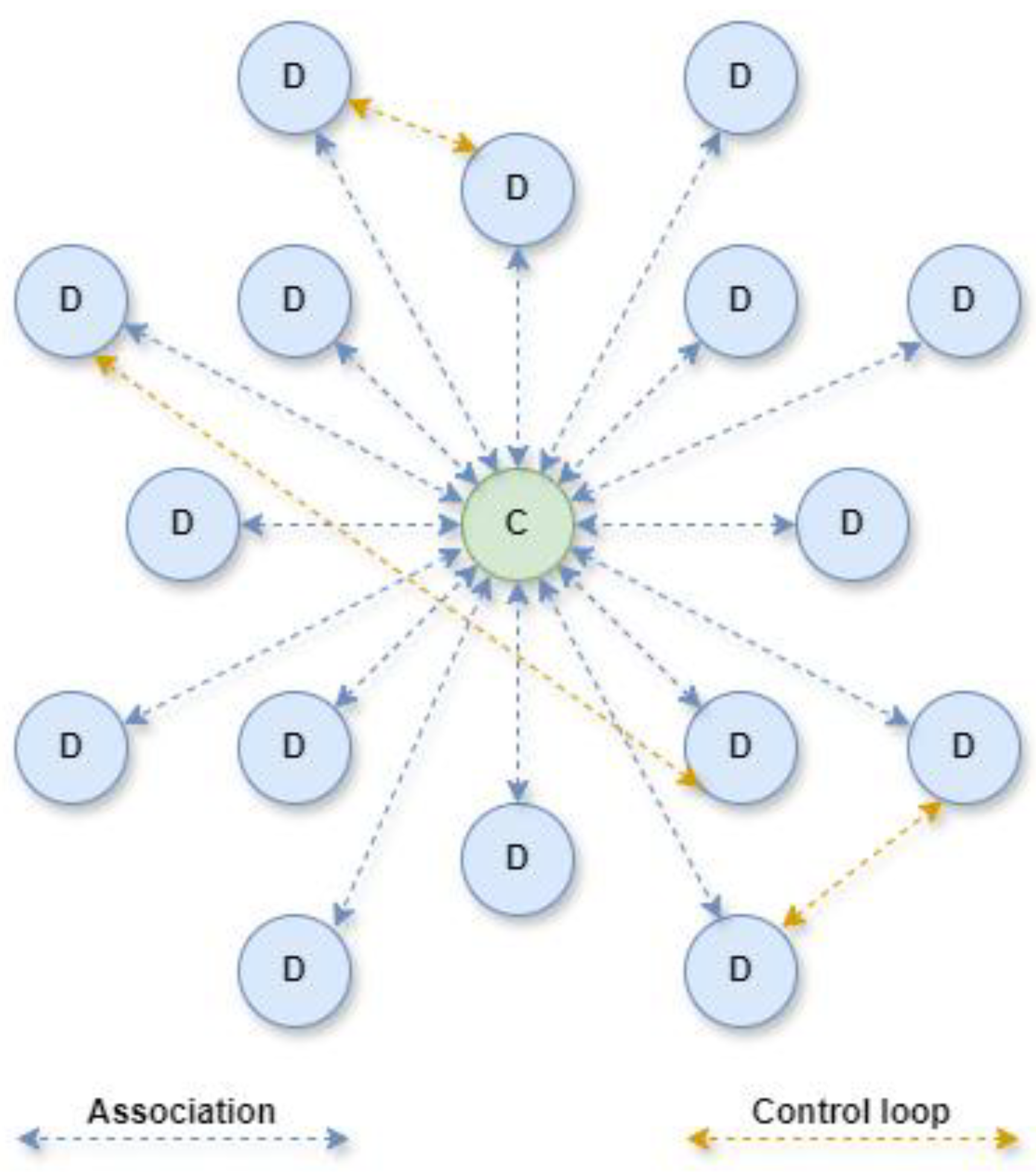

5.1. Wireless Control Network Topology

5.2. Physical Layer

- PLDE_Init - used to initialize the transceiver and in turn calls the AT86RF212B_Init function.

- PLDE_Idle - used to set the transceiver to idle mode (TRX_OFF). In this way, the transceiver consumes the least current. This mode is used when the transceiver does not have to receive or transmit data frames.

- PLDE_Transmit - used to pass a data frame. The parameters of the function include the data to be transmitted and its size.

- PLDE_Receive - used to set the transceiver to receive mode.

- PLDE_ComputeRSQI - used to calculate the quality of the received signal. It can have a value between 0 and 31.

- PLDE_Interrupt - called every time the transceiver changes its state. Depending on the new status, some operations are required. The transceiver signals a state change by setting the IRQ pin to high. This function calls the functions in the upper layer (the data link layer) that retrieve the frames received by the transceiver.

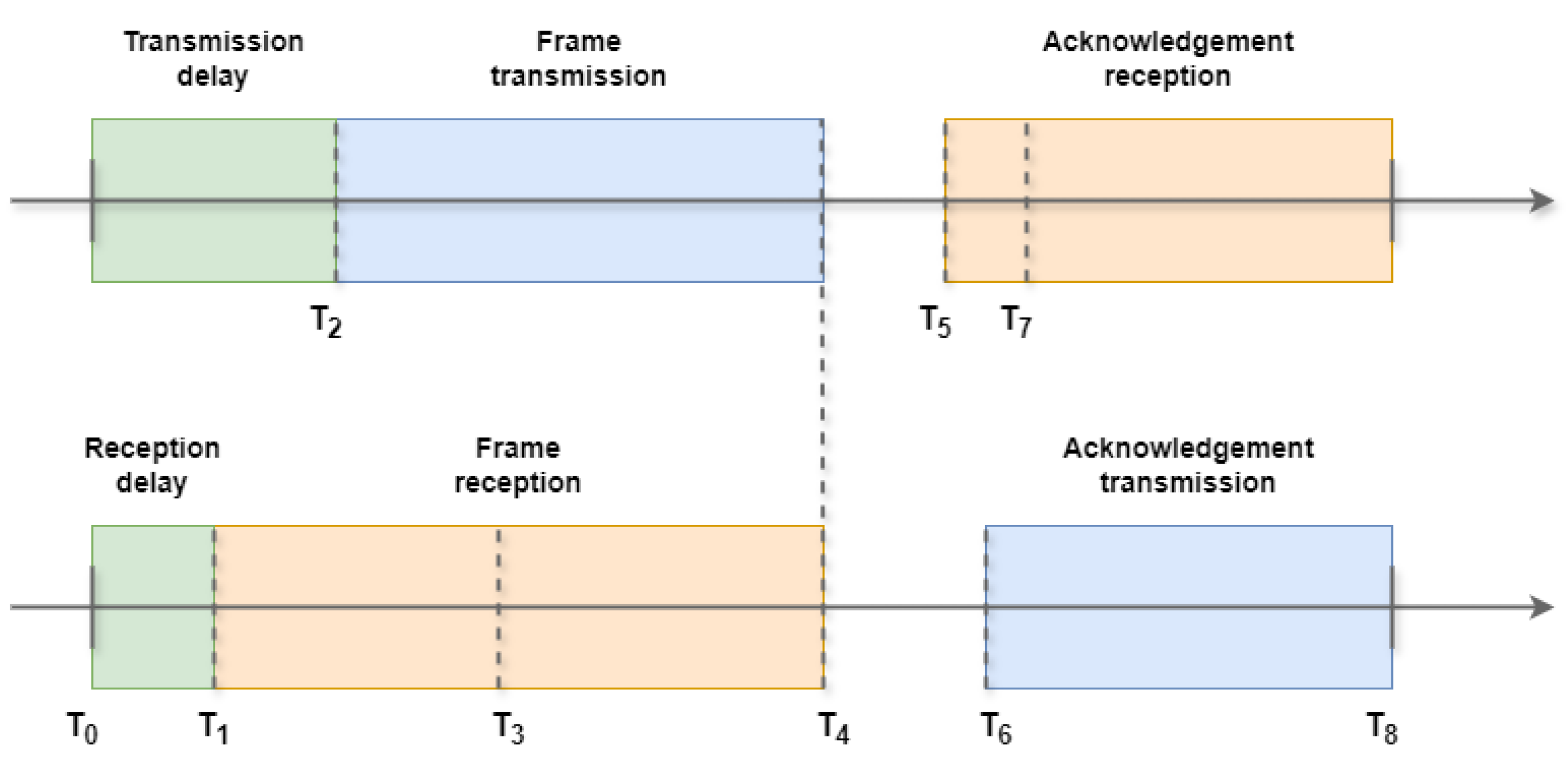

5.3. Data Link Layer

- MLME_Read – used to read an attribute of the data link layer, regardless of its type

- MLME_Write – used to write and attribute of the data link layer, regardless of its type

- MLDE_GenerateBeacon – used to generate a beacon frame and gets as input the beacon frame parameters and the payload.

- MLDE_GenerateData – used to generate a data frame and gets as input the payload on the type of link on which the frame will be sent.

- MLDE_GenerateCommand – used to generate a command frame and gets as input the type of command and the payload.

- MLDE_GenerateAck – used to generate an acknowledgement frame.

- PLDE_FrameInication - notifies the application layer that new frame has been received. This function extracts the useful data from the frame and sends it to the application layer.

- PLDE_ErroIndicate – used by the physical layer to notify the data link layer that and error occurred while receiving a frame.

- PLDE_FramConfirm – used by the physical layer to notify the data link layer that a new frame has been received successfully.

- MLDE_IncommingFrame – used by the data layer to extract and analyze the data contained in each received frame and perform the necessary actions.

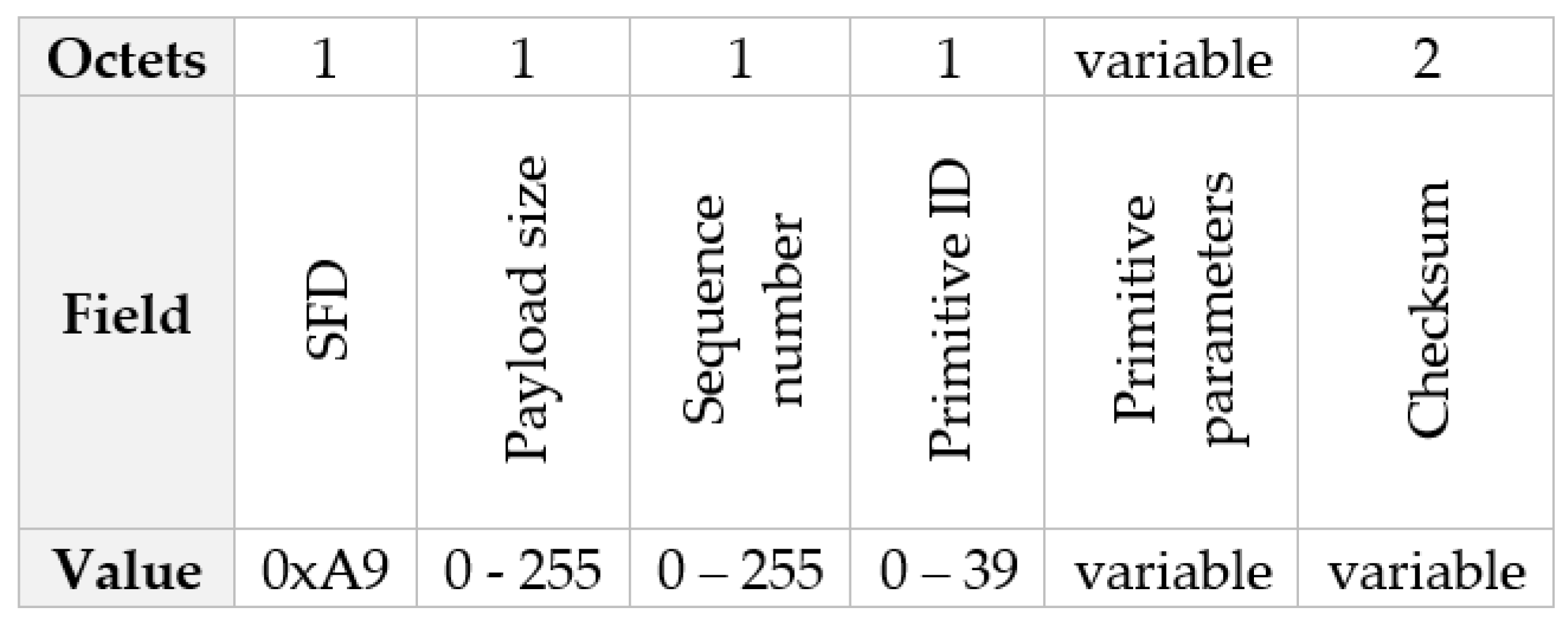

5.4. Inter-Layer Communication

- Start frame delimiter (SFD)

- Payload data size

- Sequence number

- Primitive identifier

- Primitive parameters

- Checksum

5.5. Time Management

5.6. Starting the Network

5.7. Joining the Network

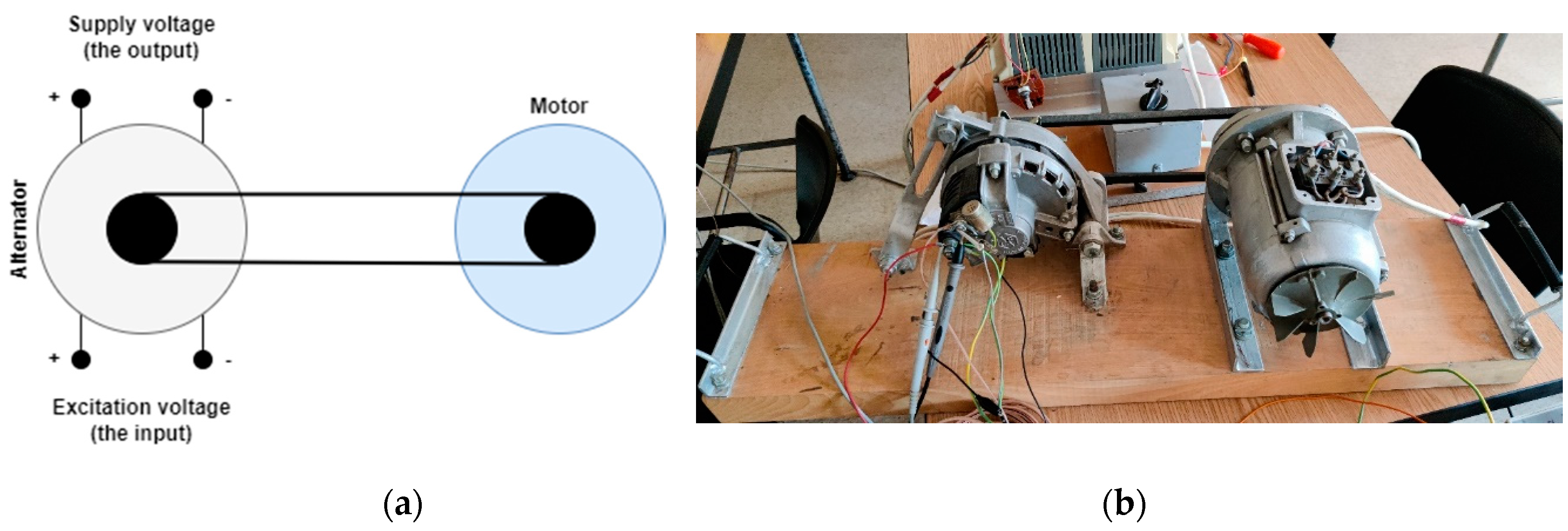

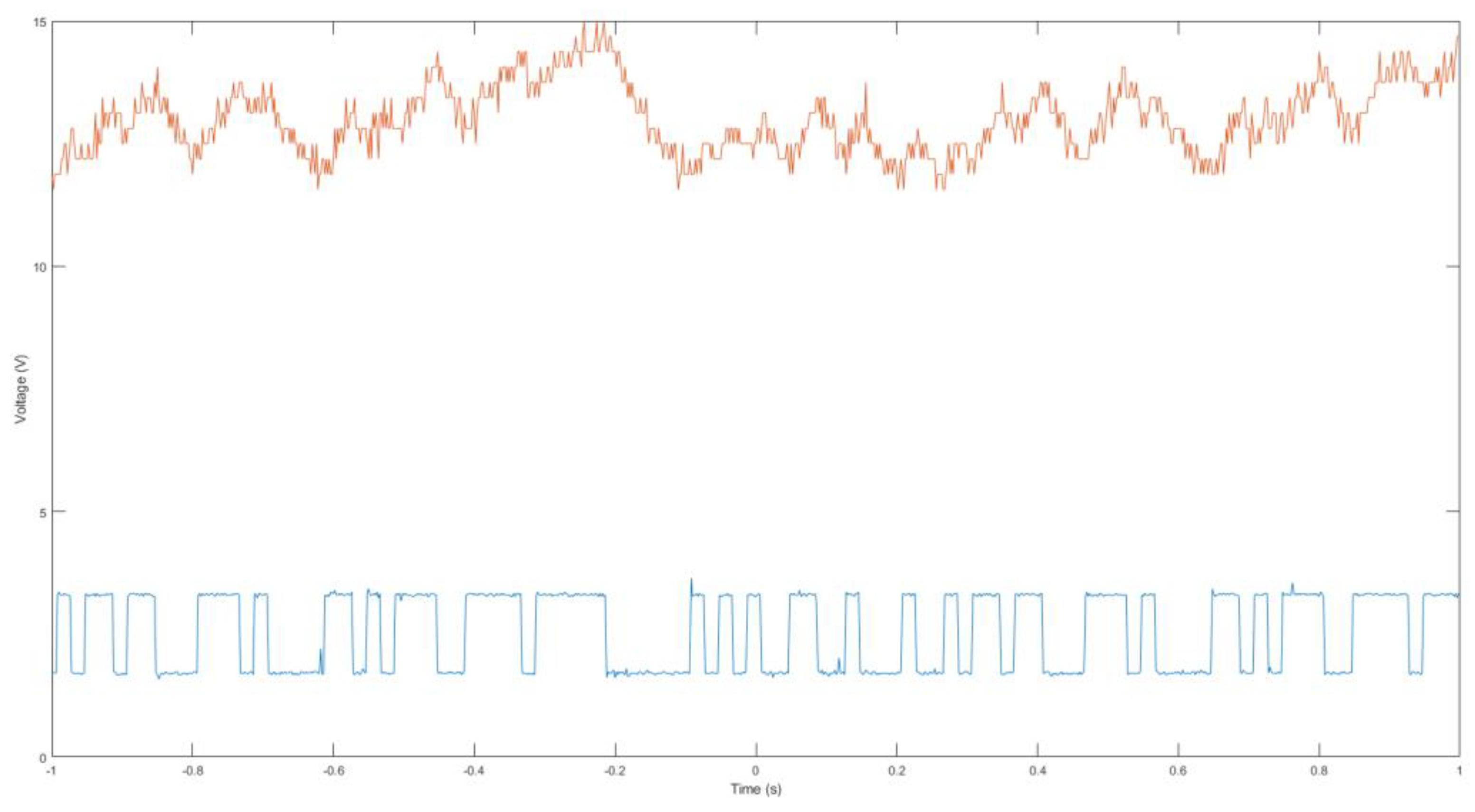

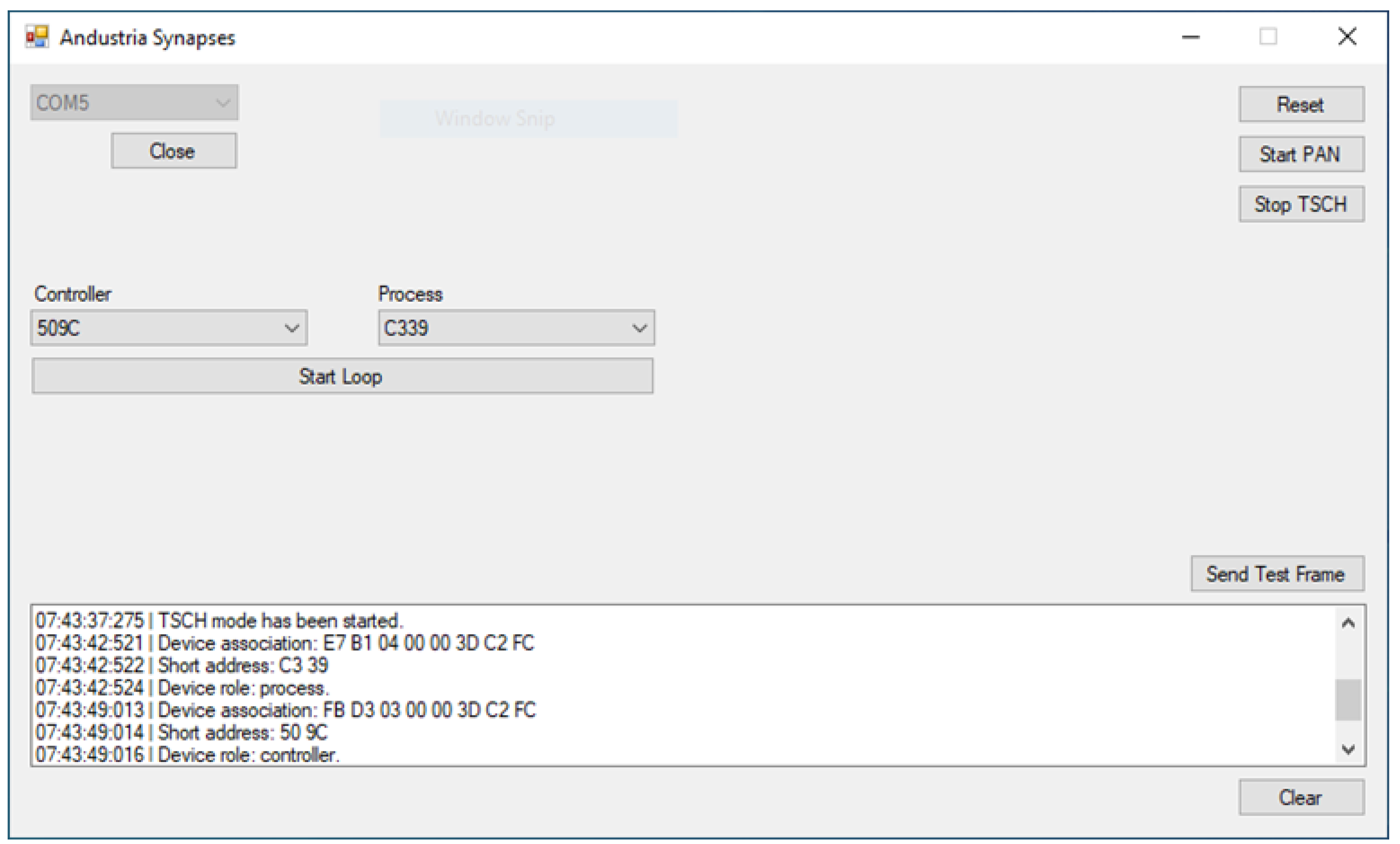

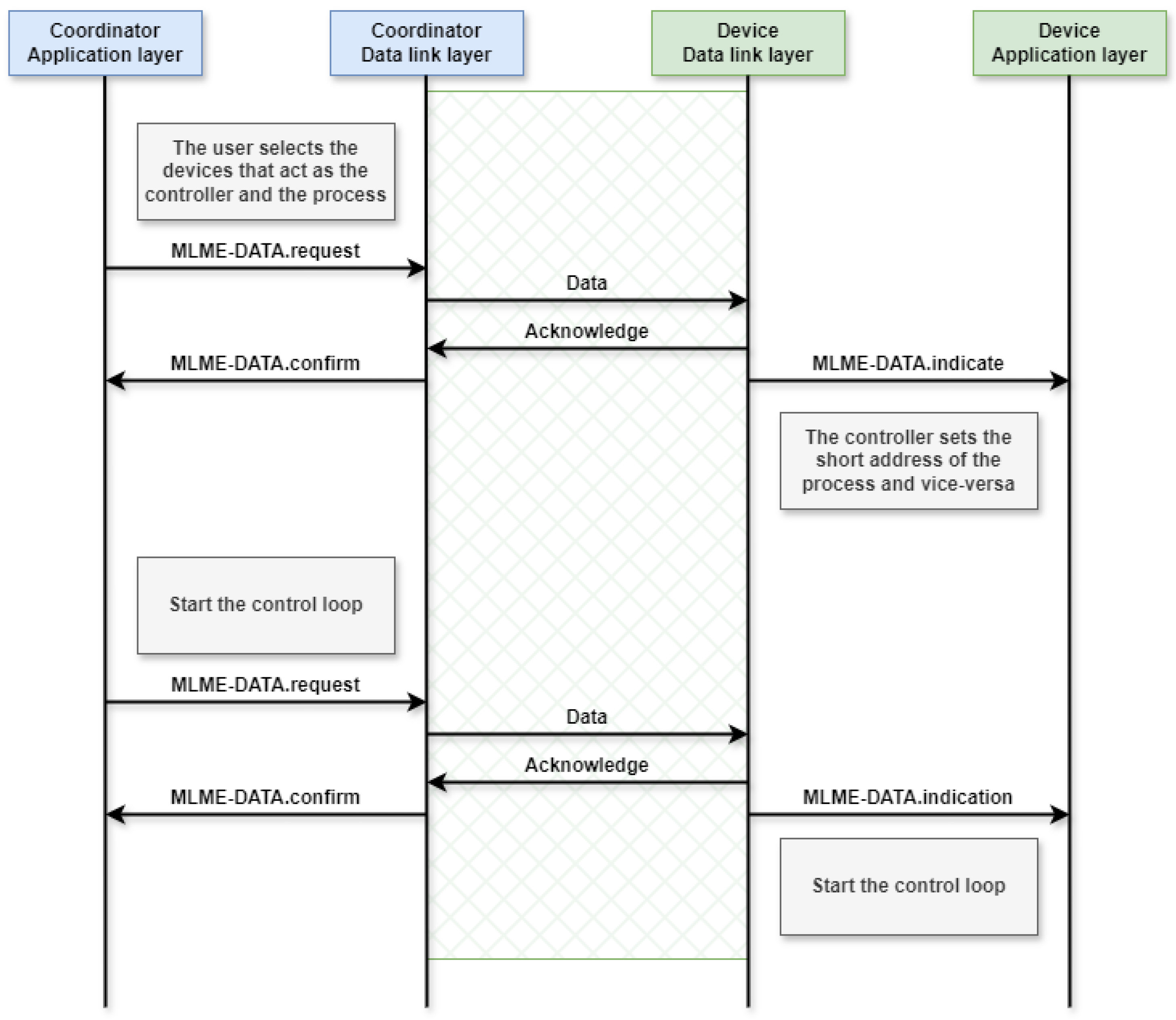

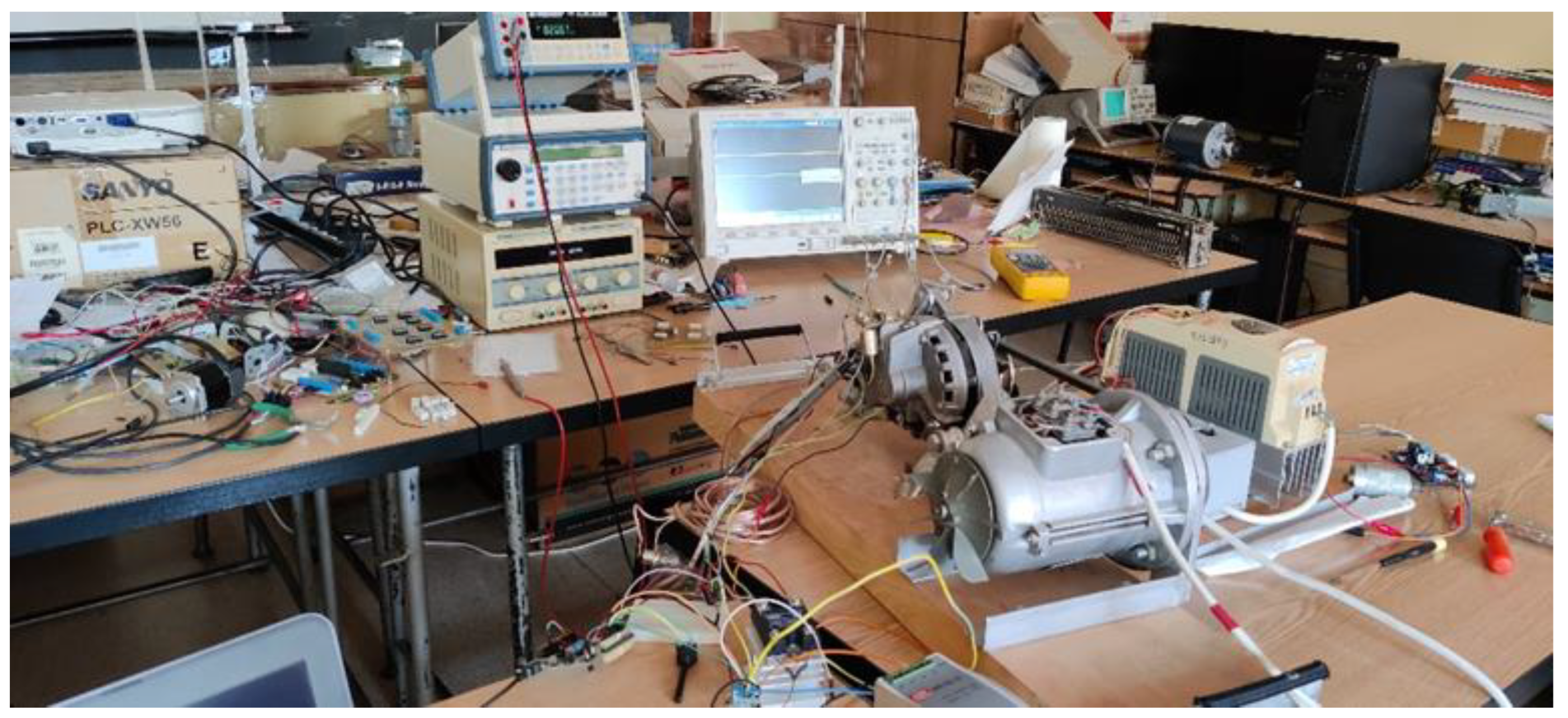

5.8. Setting-Up the Control Loop

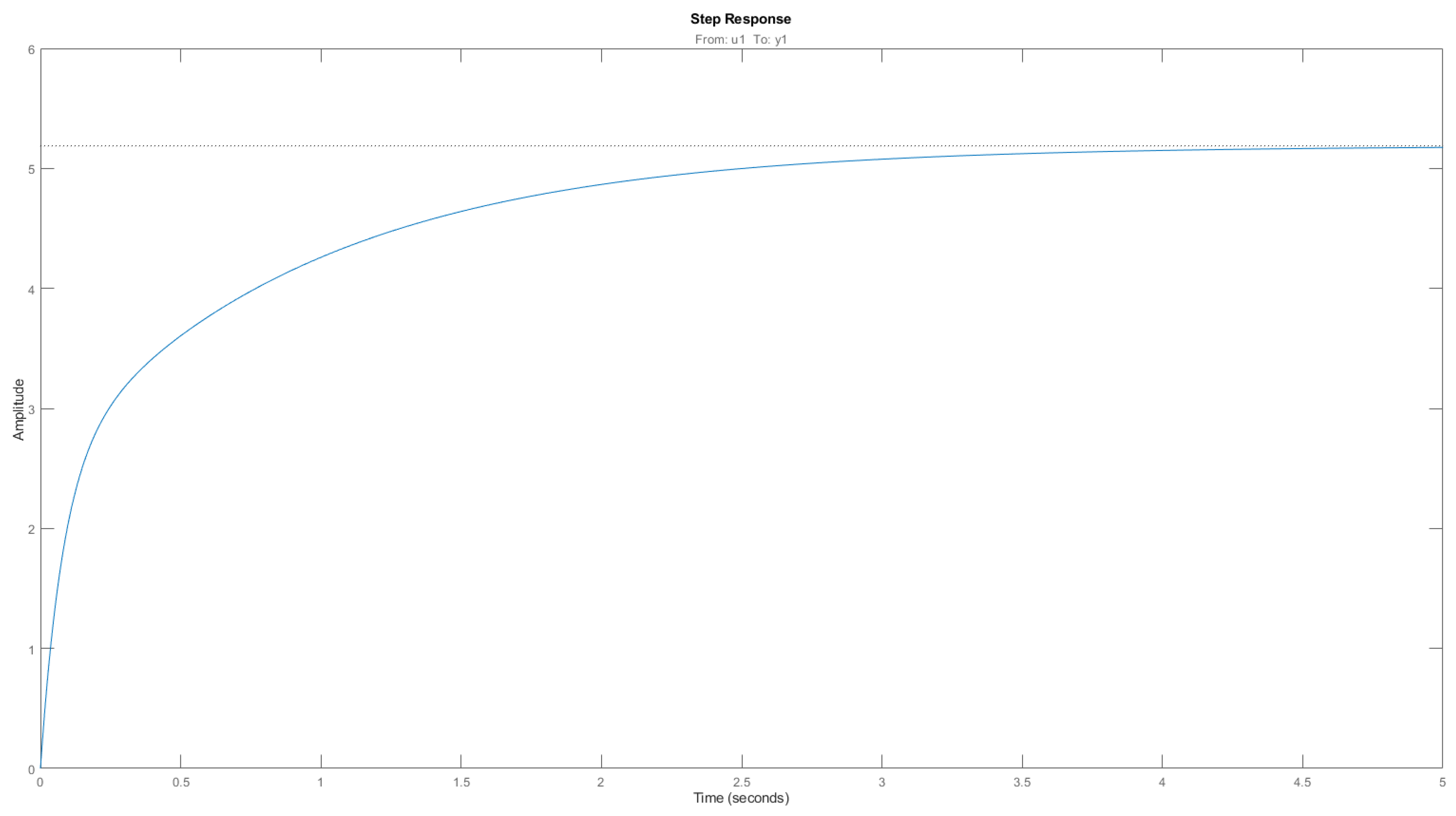

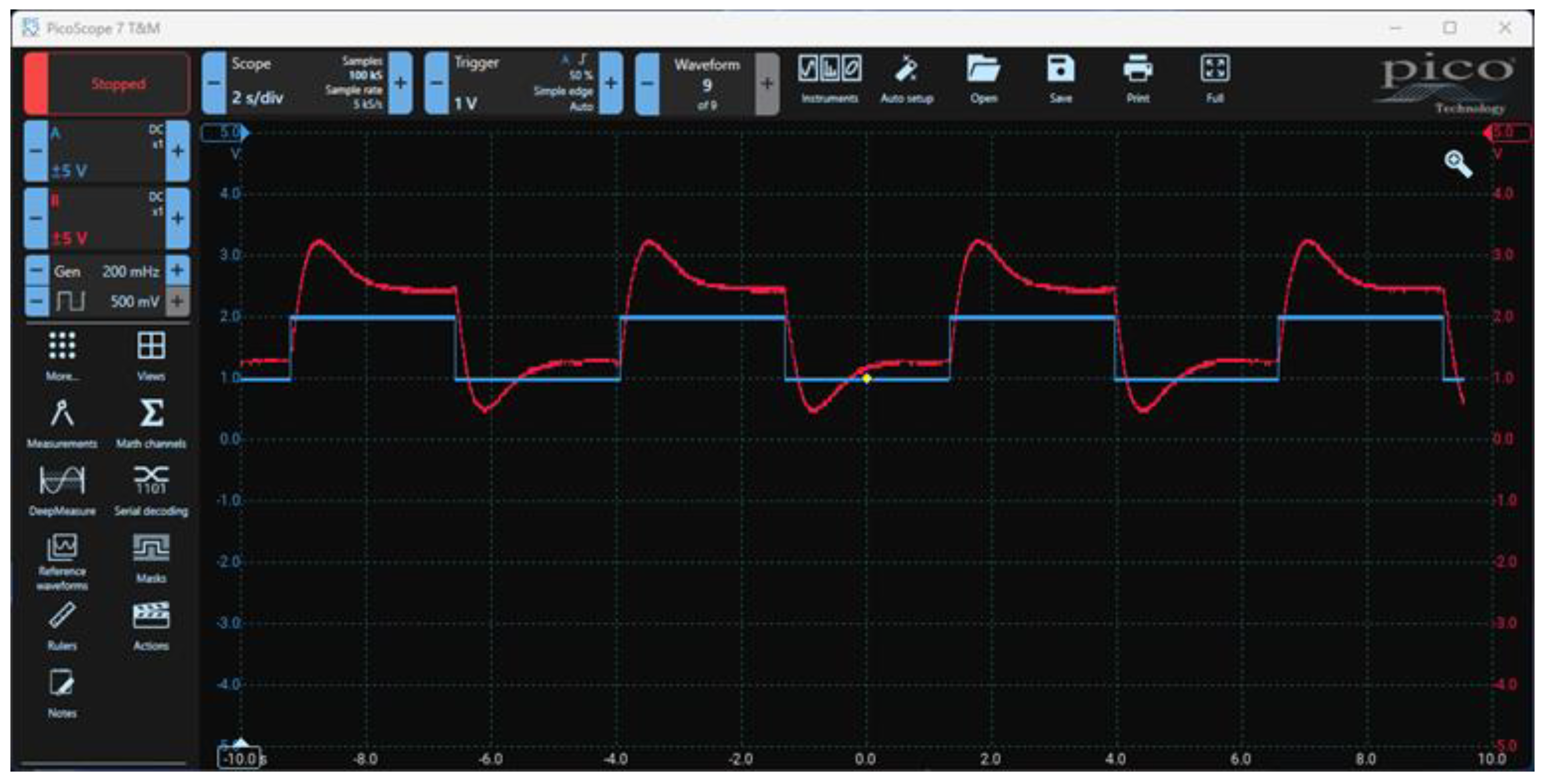

- Settling time: 5.19 seconds

- Overshoot: 0%

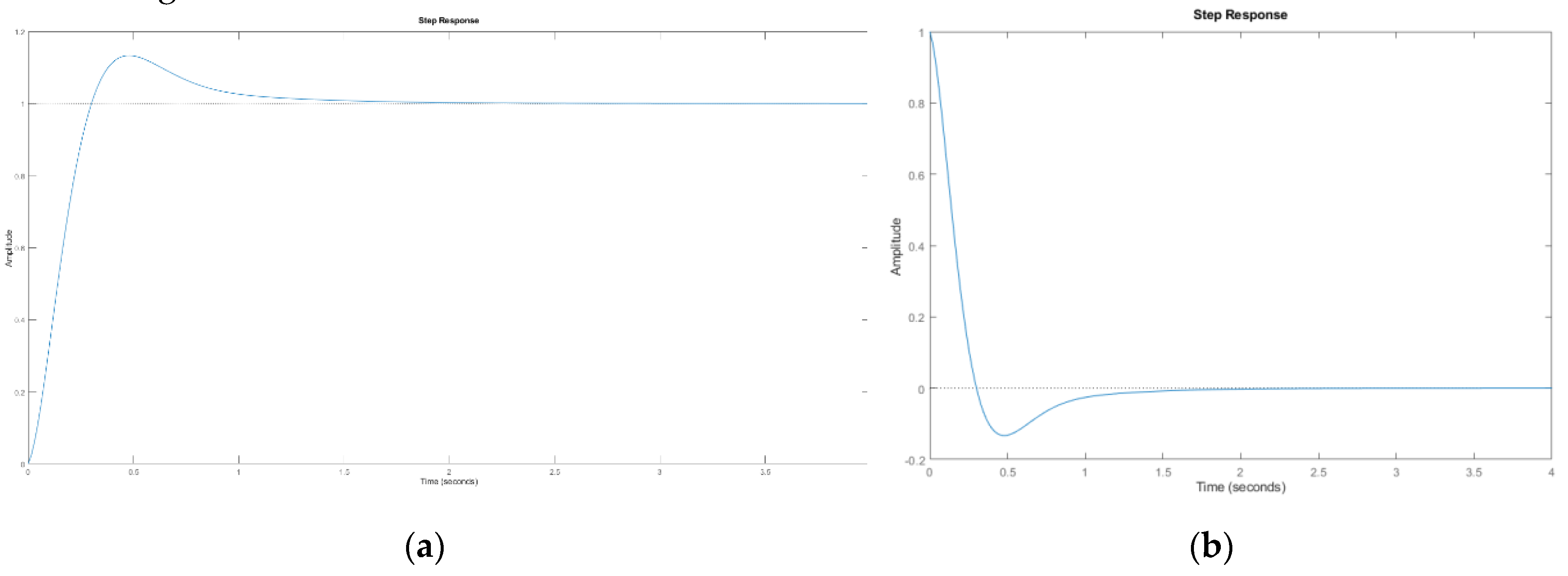

- Settling time: 3.07 seconds

- Settling time: 4 seconds

- Overshoot: 13.3%

- Settling time: 1.09 seconds

5.9. Running the Control Loop

6. Discussion

- channel hopping - each device associated to the WCN hops from one channel frequency to another in a well-defined pattern configured by the coordinator. [22]

- device redundancy - minimizes the risk of control loop malfunction if one of the two devices, controller or process, becomes inactive. Redundancy requires that all information related to the wireless network is duplicated in master-slave devices. Furthermore, tight time synchronization is mandatory between these pairs of devices.

- additional communication frequency bands - IEEE 802.15.4-2020 offers support for different frequency bands like ultra-wide-band (UWB) which are less known and used. [23]

- adaptive transmission power - the power usage of wireless devices cand be reduced by using adaptive transmission power. Devices will include in the acknowledgement frame information about the signal quality like the received signal strength indicator (RSSI) and link quality indicator (LQI). [24]

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- SpaceX - Launches Available online: https://www.spacex.com/launches/ax-1/ (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- SpaceX - Falcon 9 Available online: https://www.spacex.com/vehicles/falcon-9/ (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Alsahli, A.A.; Khan, H.U. Security Challenges of Wireless Sensors Devices (MOTES). In Proceedings of the 2014 World Congress on Computer Applications and Information Systems (WCCAIS); January 2014; pp. 1–9.

- Shahdad, S.Y.; Sabahath, A.; Parveez, R. Architecture, Issues and Challenges of Wireless Mesh Network. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Communication and Signal Processing (ICCSP); April 2016; pp. 0557–0560.

- IEEE Standard for Low-Rate Wireless Networks. IEEE Std 802.15.4-2020 (Revision of IEEE Std 802.15.4-2015) 2020, 1–800. [CrossRef]

- ISA100 Wireless Compliance Institute Available online: https://isa100wci.org/ (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- WirelessHART | FieldComm Group Available online: https://www.fieldcommgroup.org/technologies/wirelesshart (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Blevins, T.; Nixon, M.; Wojsznis, W. PID Control Using Wireless Measurements. In Proceedings of the 2014 American Control Conference; June 2014; pp. 790–795.

- Friman, M.; Nikunen, J. A Practical and Functional Approach to Wireless PID Control. In Proceedings of the 21st Mediterranean Conference on Control and Automation; June 2013; pp. 942–947.

- Liu, Y.; Candell, R.; Lee, K.; Moayeri, N. A Simulation Framework for Industrial Wireless Networks and Process Control Systems. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE World Conference on Factory Communication Systems (WFCS); May 2016; pp. 1–11.

- OMNeT++ Discrete Event Simulator Available online: https://omnetpp.org/ (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Zhitle>Zhu, X.; Lin, T.; Han, S.; Mok, A.; Chen, D.; Nixon, M.; Rotvold, E. Measuring WirelessHART against Wired Fieldbus for Control. In Proceedings of the IEEE 10th International Conference on Industrial Informatics; July 2012; pp. 270–275.

- Foundation Fieldbus | FieldComm Group Available online: https://www.fieldcommgroup.org/technologies/foundation-fieldbus (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Mager, F.; Baumann, D.; Trimpe, S.; Zimmerling, M. Poster Abstract: Toward Fast Closed-Loop Control over Multi-Hop Low-Power Wireless Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 17th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Information Processing in Sensor Networks (IPSN); April 2018; pp. 158–159.

- Ferrari, F.; Zimmerling, M.; Mottola, L.; Thiele, L. Low-Power Wireless Bus. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Embedded Network Sensor Systems; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, November 2012; pp. 1–14.

- Rusu, A. Low-power wireless control systems; PhD Thesis, Technical University of Cluj-Napoca, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2025 (in preparation).

- STM32L432KC - Ultra-Low-Power with FPU Arm Cortex-M4 MCU 80 MHz with 256 Kbytes of Flash Memory, USB - STMicroelectronics Available online: https://www.st.com/en/microcontrollers-microprocessors/stm32l432kc.html (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Texas Instruments. MSP432P401R Datasheet; Document No. SLAS826M; Texas Instruments: Dallas, TX, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.ti.com/lit/ds/slas826e/slas826e.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- CPU Benchmark – MCU Benchmark – CoreMark – EEMBC Embedded Microprocessor Benchmark Consortium Available online: https://www.eembc.org/coremark/ (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- CPU Energy Benchmark – MCU Energy Benchmark – ULPMark – EEMBC Embedded Microprocessor Benchmark Consortium Available online: https://www.eembc.org/ulpmark/ (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- ETSI. Electromagnetic Compatibility and Radio Spectrum Matters (ERM); Short Range Devices (SRD); Radio Equipment to Be Used in the 25 MHz to 1,000 MHz Frequency Range with Power Levels Ranging Up to 500 mW; ETSI EN 300 220-1 V3.1.1; European Telecommunications Standards Institute: Sophia Antipolis, France, 2017.

- Rusu, A.; Dobra, P. Channel Hopping in Wireless Process Control. In Proceedings of the 2019 23rd International Conference on System Theory, Control and Computing (ICSTCC); October 2019; pp. 67–72.

- Ratiu, O.; Rusu, A.; Pastrav, A.; Palade, T.; Puschita, E. Implementation of an UWB-Based Module Designed for Wireless Intra-Spacecraft Communications. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Wireless for Space and Extreme Environments (WiSEE); September 2016; pp. 146–151.

- Rusu, A.; Dobra, P. Using Adaptive Transmit Power in Wireless Indoor Air Quality Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2019 23rd International Conference on System Theory, Control and Computing (ICSTCC); October 2019; pp. 543–548.

| Feature | ISA100 Wireless | Zigbee | LoRaWAN |

| Operating frequency | 2.4 GHz | 2.4 GHz | 868 MHz |

| Transfer speed | 250 kbps | 250 kbps | 0.3 ÷ 50 kbps |

| Network topology | Mesh | Mesh | Mesh |

| Maximum network size | 100 knots | 65,000 knots | 62,500 knots |

| Modulation | IEEE 802.15.4 2.4 GHz O-QPSK |

IEEE 802.15.4 2.4 GHz O-QPSK 868/915 MHz BPSK 868/915 MHz FSK |

433/868/915/920 MHz LoRa 868/915/920 LR-FHSS 433/868/915/920 FSK |

| Latency | 100 milliseconds | 15 milliseconds | 5 minutes |

| STMicroelectronics STM32L432KC | Texas Instruments MSP432P401R | |

| General characteristics | ||

| Core | Arm Cortex-M4F | Arm Cortex-M4F |

| Maximum operating frequency | 80 MHz | 48 MHz |

| FLASH memory | 256 KB | 256 KB |

| RAM | 64 KB | 64 KB |

| Supply voltage | 1.71 ÷ 3.6V | 1.62 ÷ 3.7V |

| Operating temperature | -40 ÷ 85 °C | -40 ÷ 85 °C |

| Consumption | ||

| Run mode | 84 µA/MHz | 80 µA/MHz |

| Sleep mode | 1.0 µA | 660 nA |

| CoreMark [19] | 3.42 CoreMark/MHz | 3.41 CoreMark/MHz |

| ULPMark [20] | 176.7 ULPMark-CP | 193.2 ULPMark-CP |

| Interfaces | ||

| ADC | 1 | 1 |

| DAC | 2 | - |

| UART | 3 | 4 |

| SPI | 2 | 8 |

| I2C | 2 | 4 |

| CAN | 1 | - |

| DMA | 14 channels | 8 channels |

| USB | Full speed | - |

| Package | UFQFPN32 | LQFP100 VQFN64 NFBGA80 |

| Price | €4.74 | N/A |

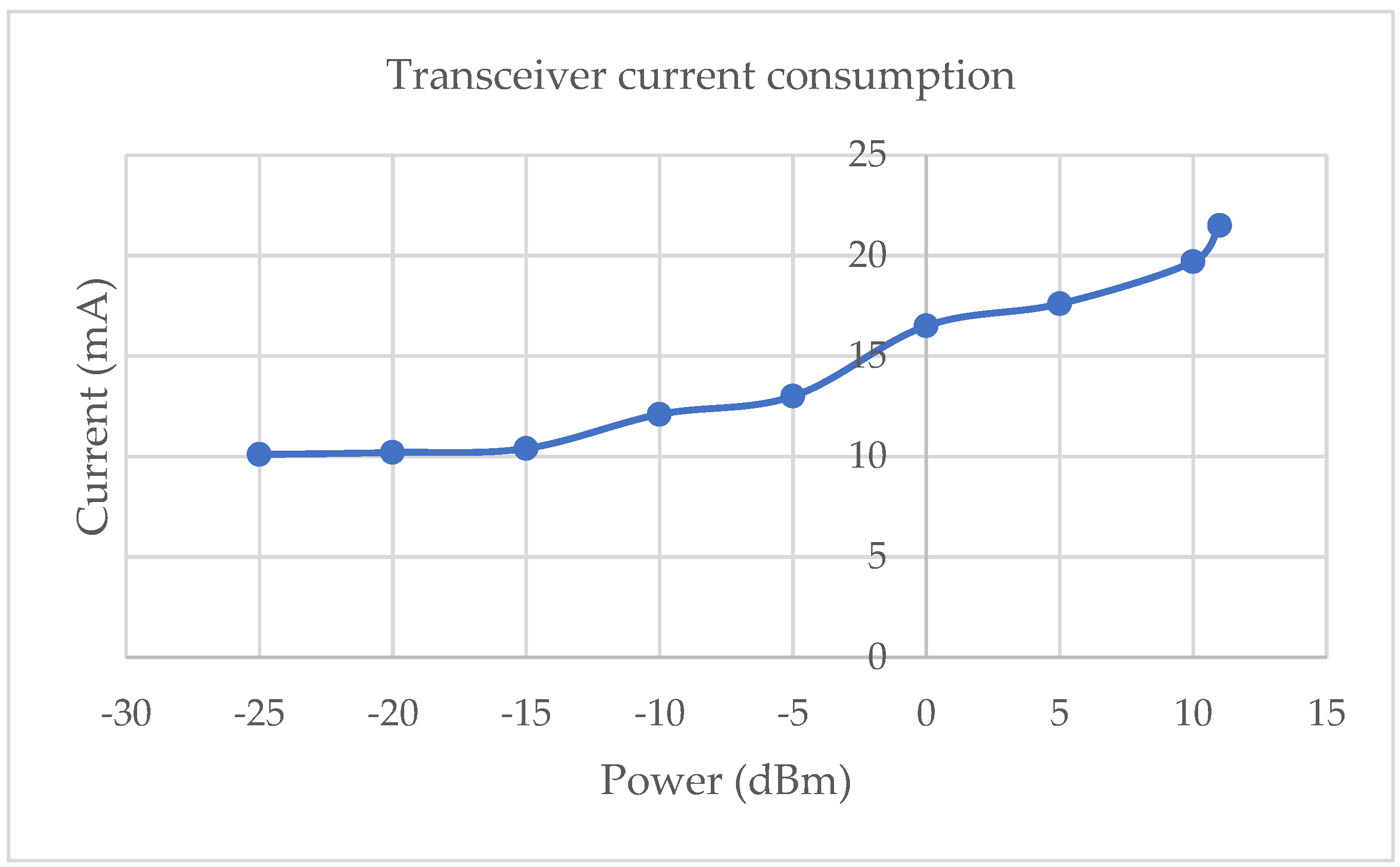

| Mode | Consumption |

| Sleep | 0.2 µA |

| Idle | 450 µA |

| Reception | 9.2 mA |

| Transmission at +10 dBm | 26.5 mA |

| Transmission at +5 dBm | 18.0 mA |

| Transmission at +0 dBm | 13.5 mA |

| Transmission at -25 dBm | 9.5 mA |

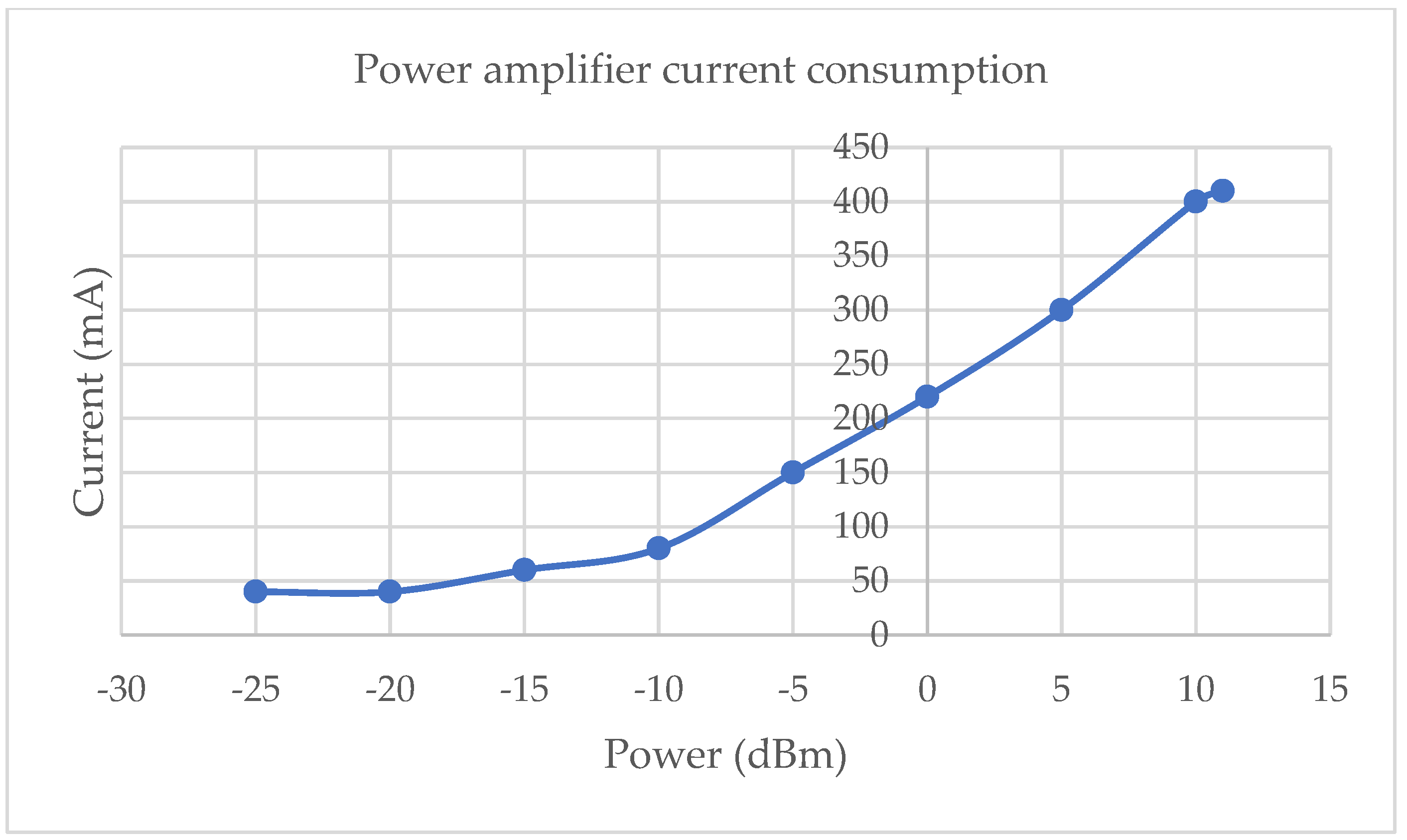

| Mode | Consumption |

| Sleep | 1 µA |

| Bypass | 280 µA |

| Reception | 6 mA |

| Transmission | 410 mA |

| Primitive ID | Primitive |

| 0 | MLME_ASSOCIATE |

| 1 | MLME_BEACON_NOTIFY |

| 2 | MLME_BEACON |

| 3 | MLME_BEACON_REQUEST |

| 4 | MLME_CALIBRATE |

| 5 | MLME_COMM_STATUS |

| 6 | MLME_DBS |

| 7 | MLME_DA |

| 8 | MLME_DISASSOCIATE |

| 9 | MLME_DPS |

| 10 | MLME_GET |

| 11 | MLME_GTS |

| 12 | MLME_IE_NOTIFY |

| 13 | MLME_ORPHAN |

| 14 | MLME_PHY_DETECT |

| 15 | MLME_PHY_OP_SWITCH |

| 16 | MLME_POLL |

| 17 | MLME_RESET |

| 18 | MLME_RIT_REQ |

| 19 | MLME_RIT_RES |

| 20 | MLME_RX_ENABLE |

| 21 | MLME_SCAN |

| 22 | MLME_SET |

| 23 | MLME_START |

| 24 | MLME_SYNC |

| 25 | MLME_SYNC_LOSS |

| 26 | MLME_SOUNDING |

| 27 | MLME_SRM_REPORT |

| 28 | MLME_SRM_INFORMATION |

| 29 | MLME_SRM_REQ |

| 30 | MLME_SRM_RES |

| 31 | MLME_SET_SLOTFRAME |

| 32 | MLME_SET_LINK |

| 33 | MLME_TSCH_MODE |

| 34 | MLME_KEEP_ALIVE |

| 35 | MLME_DSME_GTS |

| 36 | MLME_DSME_LINK_REPORT |

| 37 | MCPS_DATA |

| 38 | MCPS_PURGE |

| 39 | MLME_LINK_TABLE |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).