1. Introduction

In vitro fertilization was introduced 40 years ago, and advances such as in vitro embryo maturation, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, vitrification, and preimplantation genetic testing have increased the success of in vitro fertilization. However, in vitro culture techniques and media formulations that improve poor-quality human oocytes and embryos are an unmet clinical need, and new approaches are currently being developed. No precise media formulations are available to optimize culture to blastocysts development ratios in poor-quality human embryos. Currently, major causes of advanced aged female infertility are embryo incompetence and low pregnancy outcomes in assisted reproductive technology (ART) [

1,

2,

3,

4]. However, no current interventions for age-related infertility can recover embryo competence for ART [

1], and no specific embryo culture media formulations are available to improve embryo quality in ART for age-related infertility.

Embryo quality has been suggested to be highly associated with mitochondrial function. Several studies have reported that mitochondrial function can be improved by several agents, including anti-reactive oxygen species (ROS). However, mitochondrial dysfunction is still an unsolved issue for aged oocytes and embryos. Mitochondria are essential for the metabolism and catabolism of multiple substrates, generation of metabolic signals, and the sensing of metabolic cues. Mitochondrial integrity affects cellular health, and mitochondrial defects are associated with numerous diseases [

5]. However, therapeutic approaches that alleviate mitochondrial dysfunction are limited. Currently, the reversal of mitochondrial dysfunction is the focus of intense investigation, necessitating the identification of additional biochemical pathways that can be targeted to alleviate mitochondrial dysfunction [

6]. However, mitochondria are dynamic structures that engage in fusion, fission, transport, and mitophagy. Although these behaviors are regulated by proteins distinct from mitochondrial bioenergetic reactions, recent studies suggest that metabolism and mitochondrial dynamics are tightly linked with significant inter-regulation [

7]. Mitochondrial fusion and fission are unique processes that occur under different conditions to adapt mitochondrial morphology and dynamics to the cell’s bioenergetic requirements. Tau protein functional activity is linked to the net movement of axonal mitochondria to the neuronal cell body. Its dysfunction is more associated with dementia than beta-amyloid plaques. Therefore, therapies that target Tau have been reported to improve cognitive function in Alzheimer’s disease. Microtubule integrity is regulated by Tau protein, which affects mitochondria function and is required for the movement of mitochondrial at the axons of neurons [

8]. It performs this function by functioning as a linker protein between microtubule-associated proteins to stabilize microtubules. Tau protein is an attractive target for new therapeutic approaches for dementia and several small molecules that affect Tau function have entered clinical trials to examine their potential as treatments for neuronal degeneration disorders [

9]. Because microtubule disintegration is considered a key cause of the mitochondrial dysfunction leading to dementia, reestablishing microtubule integrity could be feasible therapy for dementia [

10]. A previous study reported that a microtubule stabilizer promotes recovery from dementia [

11].

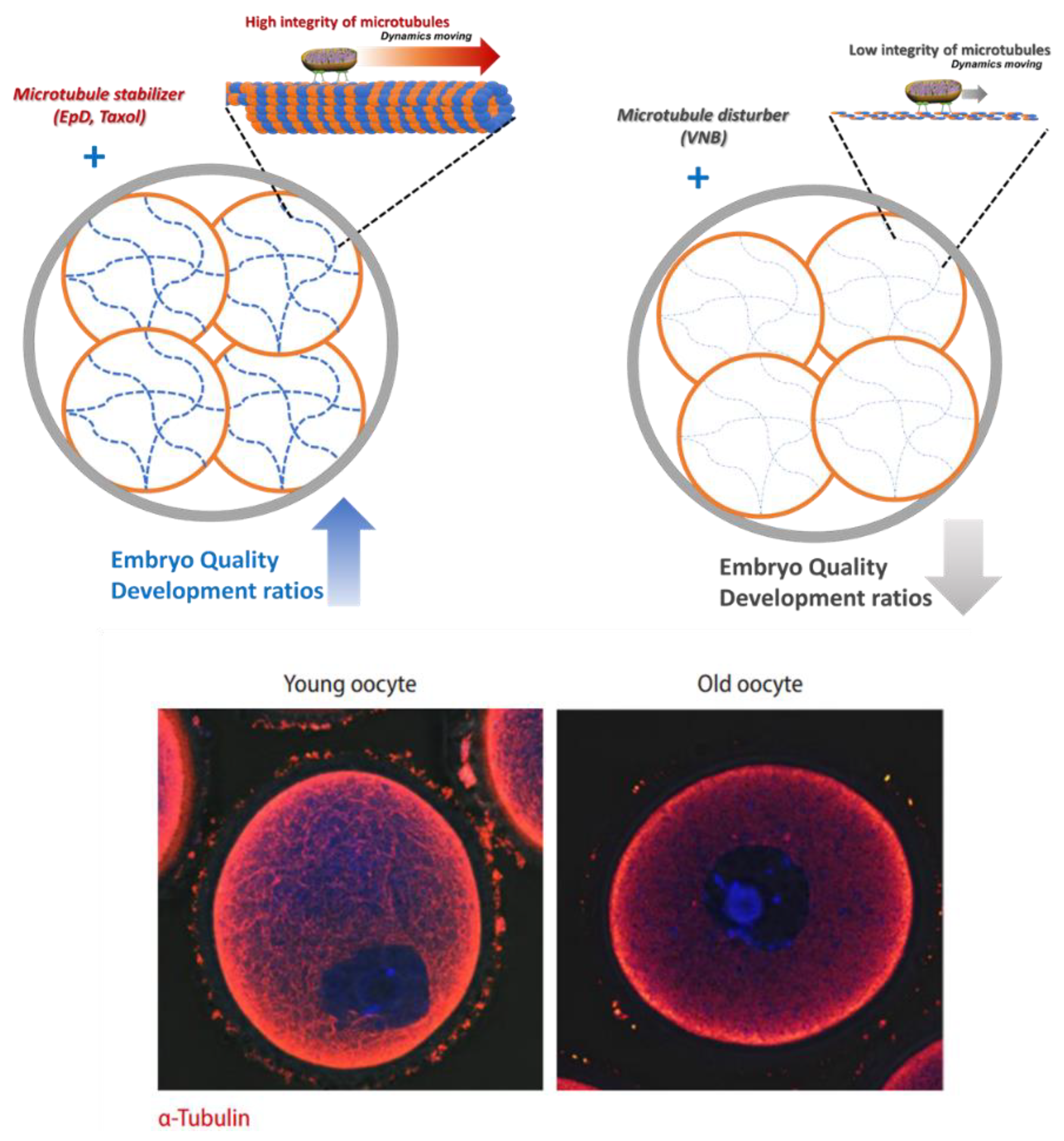

In the oocyte, mitochondria are dynamic structures, and their degree of movement is associated with oocyte quality. Mitochondria move more slowly in aged oocytes than in young oocytes. We have previously reported that increased mitochondria movement in the oocyte may be associated with increased oocyte quality [

12], suggesting that a small molecule microtubule stabilizer could be used to improve mitochondrial functional activity and thereby embryo quality and pregnancy success. The interplay between microtubule integrity and mitochondria functional activity increases embryo competence and pregnancy success. Oxidative damage such as that caused by ROS jeopardizes the mitochondrial genome during the aging process, which together with microtubule instability, contributes to age-related mitochondrial dysfunction. We previously reported that cytoskeleton integrity dramatically decreases during aging, resulting in decreased mitochondrial functional activity and poor oocyte quality [

8]. We also reported previously that actin cytoskeleton instability is possibly the primary cause of loss of mitochondrial function in aged murine oocytes [

8]. Mitochondrial motility and loss of function may be related to actin cytoskeleton instability during oocyte maturation in young and aged mice. Mitochondrial motility along the actin cytoskeleton may play a pivotal role in determining oocyte quality, depending on age. Also, studies using microtubule stabilizer-treated cells could reveal the relationship between microtubule integrity and mitochondria functional activity. However, the effects of microtubule stability on mitochondrial bioenergetics and function in embryo development are still unidentified, and the potential for microtubule stabilizers to stimulate these processes in embryo cultures has remained unexplored. Further, the regulatory mechanisms by which microtubule integrity supports mitochondrial function during embryonic development are unknown. The aim of the present study was to determine whether use of a microtubule stabilizer would improve microtubule integrity to increase the bioenergetic and functional activities of mitochondria.

We also examined mitochondria functional activity in the preimplantation embryo, and investigated whether two microtubule stabilizers (MTS), Taxol and EpD, improve the competence of preimplantation embryo development and whether an MTS affects mitochondrial functional activity. As a negative control, we used embryos treated with vinorelbine, a microtubule disturber (MTD). Finally, we examined whether pregnancy ratios increased after transplantation of microtubule stabilizer-treated embryos into the uterus.

2. Results

2.1. MTS improved Embryo Development Ratios

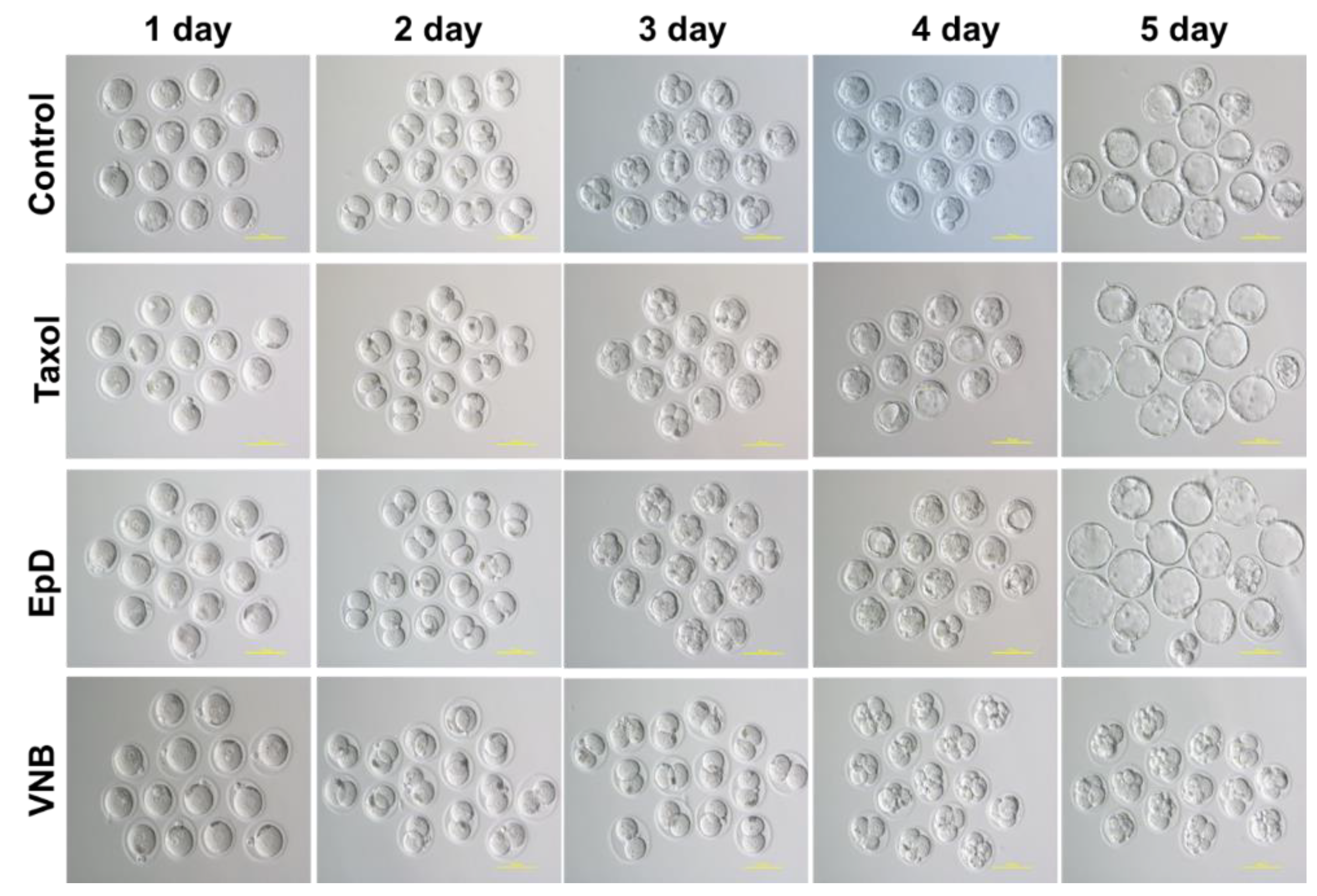

Embryo development rate was higher in MTS-treated embryos than in control and MTD groups (

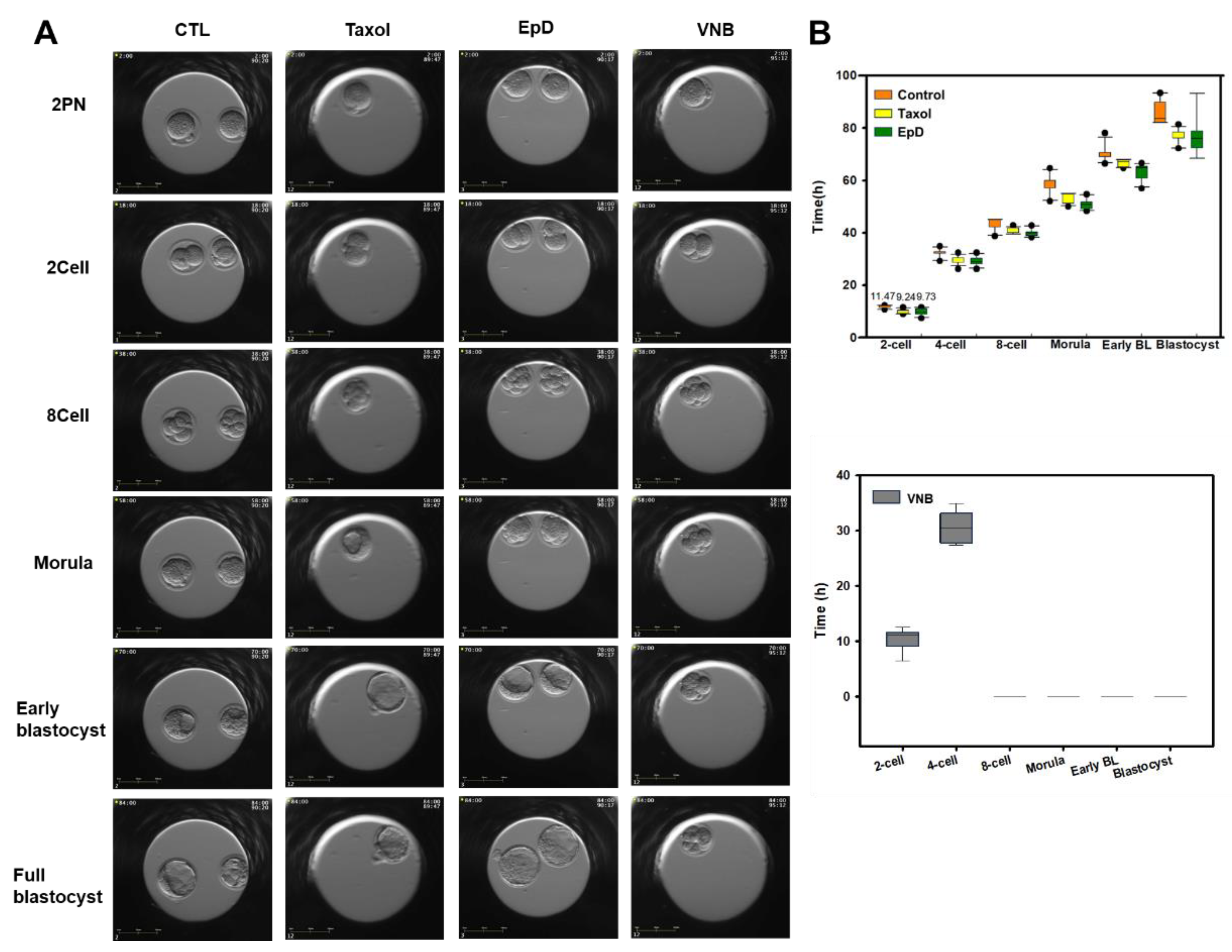

Figure 1). The development ratios of MTS- and MTD-treated embryos were evaluated. The development speed was faster in MTS-treated embryos than in control and MTD-treated embryos (

Figure 2). The times of each embryo development stage, including two-cell to four-cell, four-cell to eight-cell, eight-cell to morula, morula to blastocyst, and blastocyst to blastocyst, were decreased in MTS-treated embryos relative to control and MTD-treated embryos (

Figure 2). Blastocysts are more likely to implant and develop into successful pregnancies. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that MTS treatment increased the development rates of mouse embryos.

We measure the development speed of preimplantation embryo with MTS. Using a real-time cell monitoring system, the times at which embryos reached each developmental embryonic stage were measured (

Figure 2A, Right graph, supplement movie clip 1(A. Control: CTL), (B. Taxol), (C. EpD) and (D. VNB)). Blastocysts in the EpD (63 ± 13h) and Taxol (68 ± 10.4 h) groups reached the fully expanded blastocyst stage faster than the control group (71 ± 11.4h). The time required to reach the morula stage was dramatically decreased in both experimental groups (EpD 51± 25.7 h; Taxol 55 ±23 h) relative to control 60± 22 h;

Figure 2A, Right). Furthermore, the developmental rate to the blastocyst stage was 9.09%, 18.18% faster in the EpD, Taxol group than in the control group during the morula to late blastocyst stages. MTD treated group present stop embryo development after the four-cell stage.

Notably, preimplantation embryos cultured with EpD and Taxol exhibited the best speed and blastocyst development rate among the experimental groups. Microtubule stabilizer treatment positively impacted embryo development, potentially by better recapitulating the microtubule integrity of the preimplantation embryo.

2.2. Mitochondria Content and Membrane Potentials Were Higher in MTS-Treated Embryos

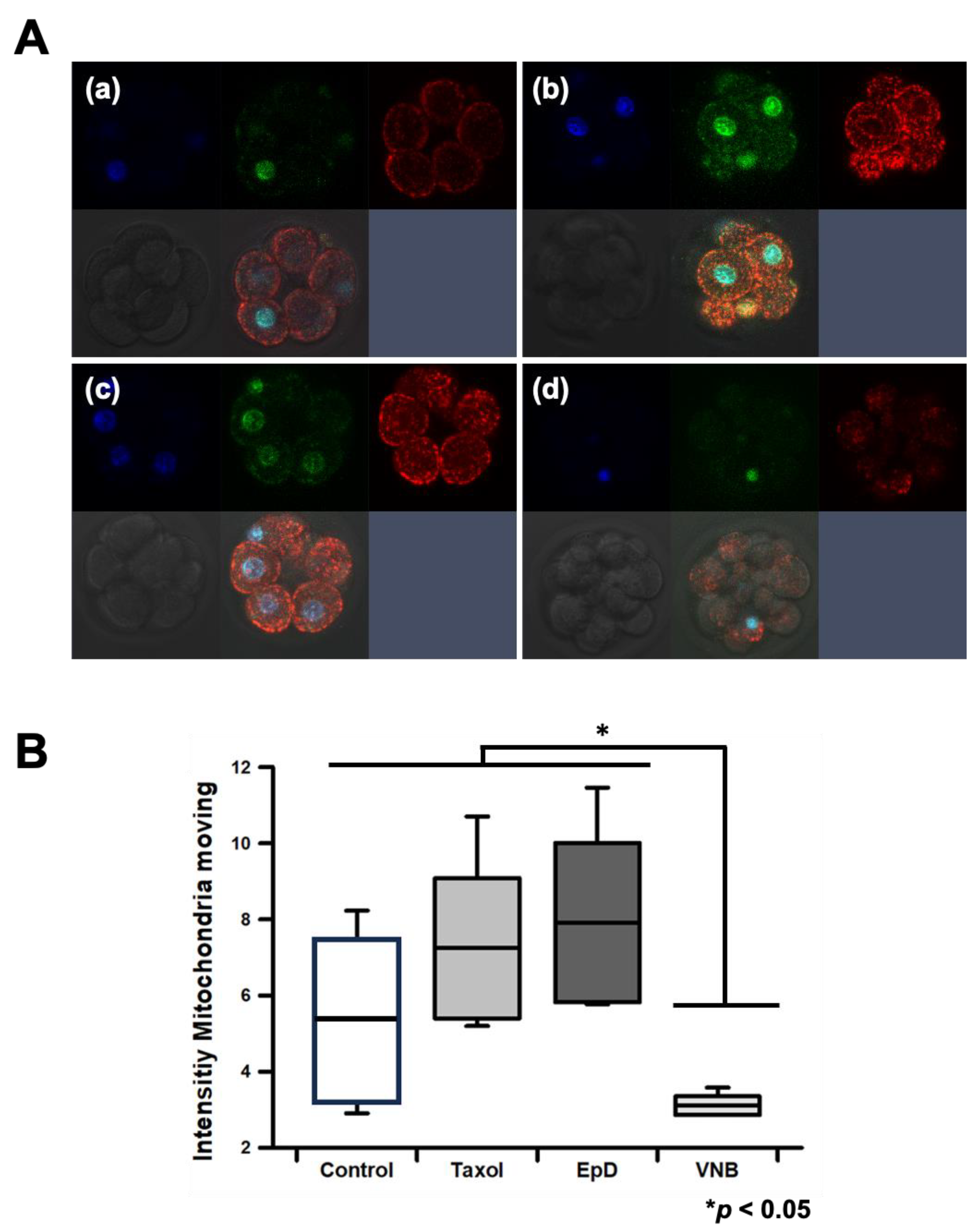

Mitochondria content and membrane potential were measured in MTS- and MTD-treated embryos using mitochondria-specific staining dyes, detecting mitochondria mass with MitoSpy Green FM, and mitochondria membrane potential with MitoSpy Orange CMTMRos. Mitochondria content, indicated by a green signal, was significantly higher in MTS-treated embryos than in control and MTD-treated embryos (

Figure 3A). MTS also increased mitochondrial membrane potential relative to that in control and MTD-treated embryos (

Figure 3A). Mitochondrial mass and membrane potential ratios were lowest in MTD-treated embryos.

2.3. Mitochondrial Dynamics in MTS- and MTD-Treated Embryos

Live confocal imaging was used to analyze the movement of mitochondria in preimplantation embryos (

Figure 3). Microtubule staining was higher in MTS-treated embryos than in control or MTS-treated embryos (

Figure 3A). Mitochondrial transport was faster in MTS-treated embryos than in control embryos. The maximum mitochondrial movement speed was 3 µm/s in MTS-treated embryos and 1 µm/s in control embryos (

Figure 3B, supplemental movie clip2 2A. control, 2B. Taxol-treated embryos, 2C: EpD-treated embryos and 2D VNB-treated embryo). However, mitochondria movement was significantly lower in MTD-treated embryos than in MTS-treated embryos (supplemental movie clip; A: control embryos, D: VNB-treated embryos). The average percentage of moving mitochondrial, as detected by fluorescence staining, was measured under each experimental condition, and was expressed as the percentage of mitochondria movement in each embryos.

2.4. Expression of Embryonic Genes in MTS- and MTD-Treated Embryos

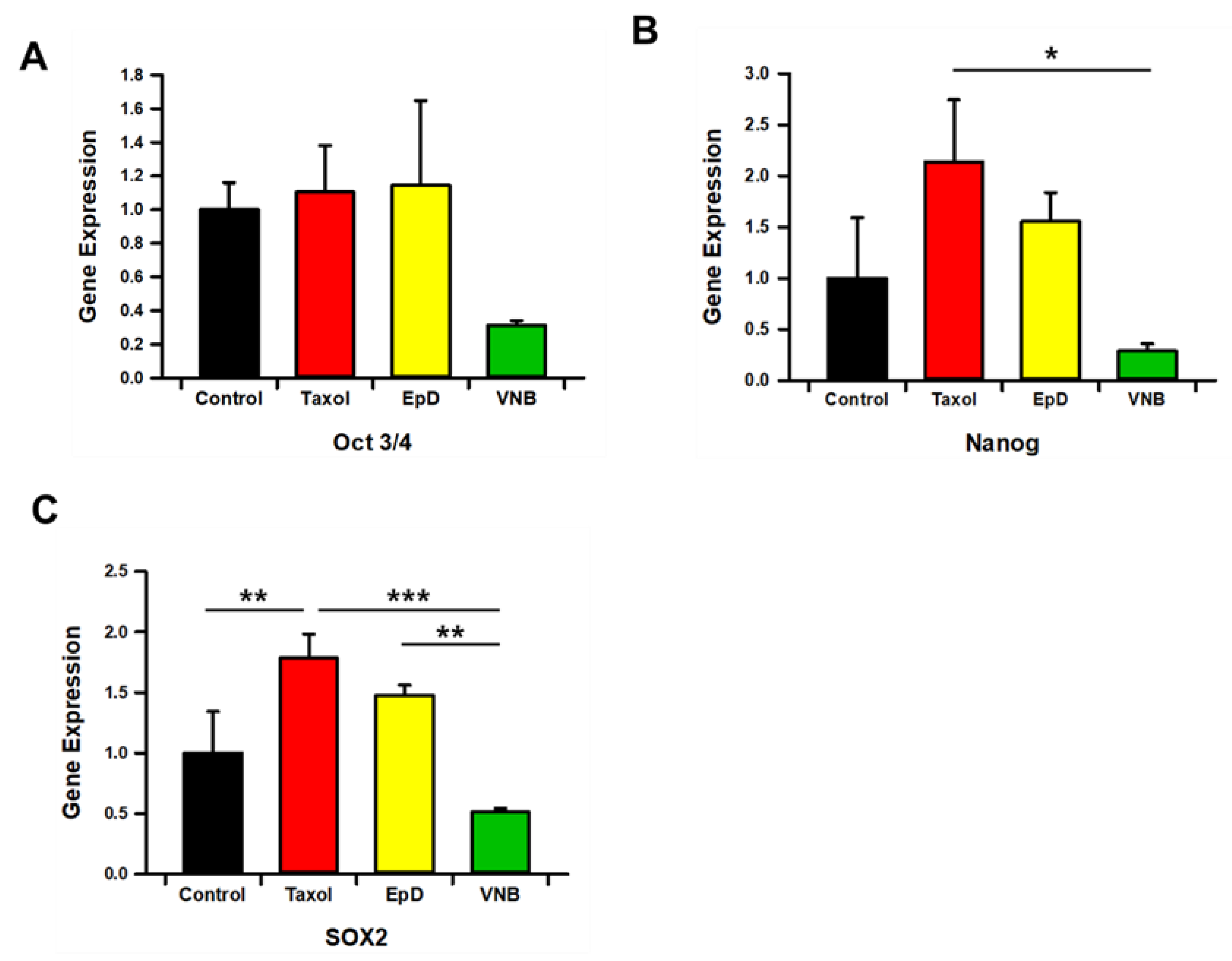

Expression levels of Oct3/4, Nanog, and Sox2 were measured in MTS- and MTD-treated mouse blastocysts by RT-PCR (

Figure 4). Oct3/4 mRNA levels were non-significantly increased in the MTS-treated group relative to those in control and MTD-treated groups (

Figure 4A). mRNA levels of Nanog and Sox2 were significantly higher in MTS-treated blastocysts than in control and MTD-treated blastocysts (

Figure 4B, 4C).

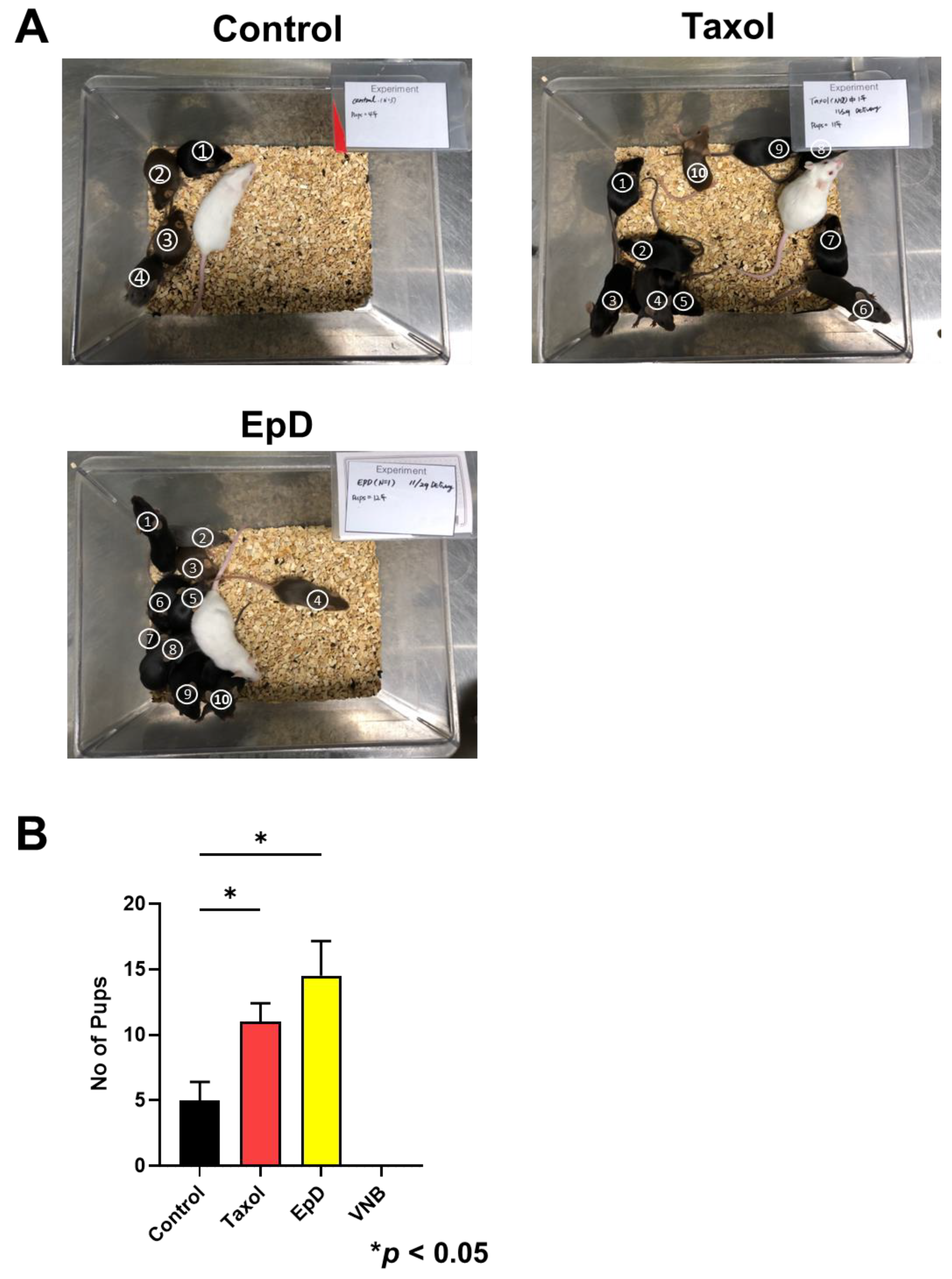

2.5. Implantation and Delivery Ratios of MTS- and MTD-Treated Embryos

Pregnancy and delivery ratios of EpD- and Taxol-treated embryos were significantly higher than those of the control group (

Figure 5). Embryos treated with MTD (VNB) were not sufficiently competent for successful pregnancy or delivery of offspring. In MTS-treated embryos, those tre ated with EpD had significantly higher delivery ratios than embryos treated with Taxol.

3. Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the effects of the MTS (Taxol and EpD) on mouse embryonic development. MTS treatment during in vitro embryonic culture enhanced mitochondrial functional activity. Further, MTS significantly increased embryonic development and blastocysts ratios. Further, MTS treatment resulted in higher offspring delivery ratios than untreated control embryos. However, MTD-treated embryos were not sufficiently competent for implantation or successful pregnancy.

The MTS used in the present study in used in clinical practice as an anti-cancer therapy and neurodegenerative disease therapy. The anti-cancer mechanisms of the MTS Taxol are incompletely understood, but prior reports suggest that MTS target mitochondria-dependent apoptotic signaling [

6]. However, the effects of these agents are dose dependent. Therefore, Tau-targeted therapy has been introduced for the treatment of neurodegeneration disease [

9]. Tau is a microtubule-associated protein that stabilizes microtubules, and its dysfunction causes neurodegeneration by reducing microtubule integrity. Several microtubule stabilizers are available, and some studies have shown that they are effective against Alzheimer’s Disease. Further, optimal doses of EpD, a microtubule stabilizer, improve cognition and decrease Tau pathology and Tau-related changes in mitochondria dynamics and quality [

13].

In assisted reproductive techniques, identifying "fast" embryos can be important as they often have a higher chance of reaching the blastocyst stage and potentially leading to successful pregnancy. In this study, MTS treated embryo development ratios at the 8-cell to morula stage and morula to blastocyst stage significantly faster than control embryo. The embryo development speed has several means and predictive of the outcome of embryo like full blastocyst development, implantation ratios, and pregnancy ratios after embryo transfer. Especially, morula stage is one of the important phases for first differentiation processes from totipotent cell as blastomere to TE and inner cell mass. And the morula phase is relatively faster than cleavage stage. Also, a lot of biological and molecular level activity in the morula phase. Therefore, normal and good quality of embryo has faster than poor quality in the ART. In the pregnancy group, timing of both morula compaction and regular blastocyst formation was significantly faster than in the non-pregnancy group. The development speed ratios utilized to selection of good quality embryo for pregnancy.

Previous our group report that mitochondrial motility along the actin cytoskeleton may play a pivotal role in determining the oocyte quality, depending on age [

12]. In generally, the actin cytoskeleton is a system of filaments and fibers that are essential for survival and diverse cellular processes, and microtubules are key modulators that underpin these cellular processes [

14]. In the actin cytoskeleton, microtubules regulate the mitochondrial trafficking of cargo proteins [

15]. Also, they are not only involved in intercellular trafficking and movement but also are involved in mitochondria quality control [

15]in the preimplantation embryo. Microtubules are a major component of the actin cytoskeleton and are involved in essential processes such as chromosome segregation, structural support, and intracellular transport of vesicles and organelles such as mitochondria. Microtubule integrity is related to diverse biological activities such as cell signaling and organelle trafficking [

15]. Also, microtubule rearrangement supports mitochondrial bioenergetics, which affect cell proliferation. Microtubule stability has been reported to promote the functional activity of mitochondria in the oocytes [

12]. In this study, these observations together with the results of the present study suggest that microtubule stability increases mitochondrial dynamics, embryo development ratios and pregnancy rates. The integrity of the actin cytoskeleton is also essential for mitochondrial quality control in the preimplantation embryo.

We analyzed the gene pression of Oct4, SOX2 and Nanog in the MTS treated embryo. High expression of Oct4, SOX2 and Nanog in the embryo is stemness factors and linked with good quality and potential for proper development of the embryo. Especially SOX2 is pivotal role for inner cell mass formation and lineages segregation during pre-implantation embryo development of early stage[

16]. MTS treated the embryo enhanced SOX2 in the embryo. And MTS enhanced embryo development speed and quality through the regulation of Oct4, SOX2 and Nanog gene expression.

We demonstrated that stabilization of microtubules with Taxol and EpD increases embryo competence and promotes in vitro embryonic development. Therefore, cytoskeletal stability could affect mitochondrial motility and metabolic activity during embryonic development. Development ratios were higher in Taxol- and EpD-treated preimplantation embryos than in control embryos. The development rate of fertilized embryos is an indicator of embryo quality [

4]. MTS-treated embryos also have significantly higher blastocyte rates than untreated embryos. Faster embryonic development is associated with healthy metabolic activity and normal chromosome status. Prior reports of human preimplantation embryo time lapse culture have demonstrated that early cleavage time and blastocyst formation are associated with increased ratios of euploid development and clinical pregnancy [

17]. Our results demonstrate the positive effect of MTS-induced microtubule stability on blastocyst development and hatched out ratios(

figure 6).

There have been several reports of an association between microtubule density and aging [

8,

18,

19] and abnormal regulation of microtubules has been linked to aging-related disorders, such as neurodegenerative disease [

8,

20]. Previously, we reported microtubule integrity in aged oocytes and embryos. Therefore, microtubule stability is also important for the recovery quality of aged oocytes and embryos. Microtubule integrity dramatically differs between young and old oocytes, and mitochondrial functional activity is closely associated with oocyte and embryo quality [

12,

21]. Mitochondrial immobility reduces the amount of energy required for oocyte maturation. In general, dysfunctional mitochondria contribute to the aging process. Therefore, recovery of functional mitochondria is important for ART with advanced age oocytes and improved embryo quality. This is the first report to identify potential reagents for the recovery of functional mitochondria for preimplantation embryo development. Reagents for recovery of functional mitochondria in embryos cultured in vitro has significant potential for ART used to overcome age-related infertility.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Mice and 2-Pronuclear(PN) Embryo Collection

BDF1 Hybrid female mice (7–9 weeks of age) and male mice (12 weeks of age) were purchased from Oriental Bio (Seongnam, Korea). A set of experiments, five females were used for embryo collection and each set of experiments was repeated three times. All procedures for animal breeding and care complied with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC approval number: IACUC210117) regulations of CHA University (Pocheon, Korea). For in vivo hormone stimulation, follicle growth was promoted by injecting 7.5IU PMSG (Pregnant Mare Serum Gonadotropin; RP1782725000; BioVendor, Czech Republic) into the abdominal cavity of female mice, and hyperovulation was induced by injecting 7.5IU hCG (Human Chorionic Gonadotropin; 668900221; LG Chem, Seoul, Korea) after 48 hours. For the second hormone injection, female mice were mated with male mice (1:1 = females: males). 2-PN embryos were collected 36 h after hCG injection and mating. In this experiment we harvested 800 embryos from 40 mice.

4.2. Treatment and Culture of Two-PN Embryos with MTS or MTD

Two-PN embryos were cultured with MTS [2 pM Taxol (PHL89806; Sigma Aldrich, CA, USC) or 2 pM Epothilone D (EpD: ab143616; Abcam, Cambridge, UK)] or MTD [5 nM Vinorelbine (VNB: V2264-5MG; Sigma Aldrich, CA, USC)]. The none-cytotoxic concentration for treatment of two-PN embryos was determined in a previous study (doi.org/10.3390/cells10123600). Embryos were cultured in individual wells in a time lapse system incubator (CNC biotech, Korea) with 5% CO2 at 37℃ in SAGETM in vitro blastocyst media (ART-1029; Origio, Denmark) supplemented with 10% Quinn’s Advantage™ serum protein substitute (SPS) (ART-3011; Origio, Denmark). Images were acquired every 5 min in each culture dish. Embryo development ratios and cleavage time points were quantified during time lapse culture. Embryo quality was classified based on cleavage speed and blastocyst ratio.

4.3. Confocal Microscope Analysis of Embryo Mitochondrial Mass and Membrane Potential

We performed time-lapse confocal microscopy live imaging of mitochondria in the preimplantation embryo from mice. To investigate mitochondrial membrane potential and mass, four-cell and eight-cell embryos were co-stained with 250 nM MitoSpy Orange CMTMRos (424803; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), which localizes to mitochondria depending on membrane potential, and 250 nM MitoSpy Green FM (BioLegend, USA), which labels mitochondria independent of membrane potential and can therefore be used to measure mitochondrial mass. Then, nuclear count was stained with 1 µg/ml Hoechst 33342® (H1399; Thermo Fisher Life Technologies, CA, USA) for 5 min at room temperature. Then transferred to a media drop on a confocal glass-bottom dish (SPL Korea). Confocal microscopy images of live embryo were acquired using an LSM880 microscope with an Airyscan META device (Carl Zeiss AG, Germany) in a covered live chamber system (5% CO2, 37 °C). All time-lapse live image examinations comprised 100 images captured every 0.5 s. Each live sample image was analyzed and exported as a moving file (25 frames/s) and as a single picture (TIFF format) using ZEN2012 software (Carl Zeiss AG, Germany). Those live imaging was performed with a confocal microscope for the analysis of mitochondria mass and membrane potential. Thus, live images were evaluated for the dynamic property of mitochondria in the embryo by using ImageJ (version 1.08) with the Difference Tracker plug-in. The moving files were used to calculate the average percentage of moving intensity and maximum speed to enumerate mitochondria in the cytoplasm.

4.4. Gene Expression Analysis

Individual embryos were harvested for RNA isolation by aspiration into an injection pipette under negative pressure. Approximately 20 blastocyst embryos were pooled and sonicated for 30 sec in a WiseClean sonicator (WUC-A10H; DAIHAN, Wonju, Korea) filled with ice. Subsequently, cDNA was synthesized with AccuPower® CycleScript RT PreMix (K2050, Bioneer, Daejeon, Korea). Primers specific for mouse Oct3/4, Nanog, Sox2, and β-actin were used to amplify these target genes. PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 3 min at 95°C followed by 50 cycles of denaturation for 10 sec at 95°C and annealing and extension for 20 sec at 60°C. The expression of each gene was normalized to that of β-actin. Real-time qPCR was performed using a real-time PCR machine (CFX Connect, 788BR08519; Bio-Rad, CA, USA) and SYBR Green Supermix (172527, Bio-Rad, CA, USA). Primers were used to analyze the effects of MTS and MTD on gene expression in blastocyst embryos.

4.5. Assessment of Pregnancy and Birth Ratios

The reproductive capacities of MTS- and MTD-treated embryos were determined using BDF1 black mice. Mice were first prepared for pseudopregnancy receipt. Vasectomized male white ICR white mice and surrogate female white ICR mice(7~10weeks) were used for embryo transfer studies. Female recipient ICR mice were mated with vasectomized male ICR mice overnight and sperm plugs were checked on the following day. Female mice with confirmed sperm plugs were used for embryo transfer (ET). Blastocysts on culture day 5 were implanted via direct intra-uterine transfer using a 30-gauge needle.

Five to seven blastocysts of each culture condition were transferred into each uterus horn of one recipient ICR mouse. After ET, implantation and live birth ratios were compared between control and experimental groups. We used three mice for each treated blastocyst for one set ET experiment and the triple repeated for statistical analysis of the assessment of pregnancy.

4.6. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were repeated in triplicate. Data are presented as average values (mean ± SD). Statical analysis was performed using Sigma-Plot 12.5 software. A one-way ANOVA followed by a post-hoc Holm-Sidak test was used to determine statistical significance. Significance levels were expressed as * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our data newly demonstrate the therapeutic potential of MTS such as Taxol and EpD, which could support embryonic competence by enhancing mitochondrial function. MTS could thus be used as a supplement in in vitro embryo culture media.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Table S1: primer sequences used for real-time qPCR, Video S1: confocal live-cell imaging movie clips of MitoTracker (red)-stained mitochondria in control (A), Taxol-treated (B), EpD-treated (C), and VNB-treated (D) preimplantation embryo.

Author Contributions

Y.H.S., M.J.C. M.H.K. S.A.O, Y.J.K. contributed to acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; Y.H.S., M.J.C., M.H.K. contributed to sample collection and design; M.J.C. and M.H.K. contributed to experimental design; J.H.L. contributed to study conception and design and writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) [grant numbers 2019R1A2C1086882 and 2022R1G1A1006651].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal experiments, breeding, and care procedures were performed following the regulations of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of CHA University. IACUC approval (approval number IACUC210117) was obtained before initiation of the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

References

- Cimadomo, D.; Fabozzi, G.; Vaiarelli, A.; Ubaldi, N.; Ubaldi, F.M.; Rienzi, L. Impact of Maternal Age on Oocyte and Embryo Competence. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018, 9, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igarashi, H.; Takahashi, T.; Nagase, S. Oocyte aging underlies female reproductive aging: biological mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Reprod Med Biol 2015, 14, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichenlaub-Ritter, U. Oocyte ageing and its cellular basis. Int J Dev Biol 2012, 56, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Long, H.; Gao, H.; Guo, W.; Xie, Y.; Chen, D.; Cong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Si, J.; et al. The Valuable Reference of Live Birth Rate in the Single Vitrified-Warmed BB/BC/CB Blastocyst Transfer: The Cleavage-Stage Embryo Quality and Embryo Development Speed. Front Physiol 2020, 11, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Sampath, H. Mitochondrial DNA Integrity: Role in Health and Disease. Cells 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.; Ardehali, H.; Balaban, R.S.; DiLisa, F.; Dorn, G.W., 2nd; Kitsis, R.N.; Otsu, K.; Ping, P.; Rizzuto, R.; Sack, M.N.; et al. Mitochondrial Function, Biology, and Role in Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circ Res 2016, 118, 1960–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.; Hossain, T.; Eckmann, D.M. Mitochondrial dynamics involves molecular and mechanical events in motility, fusion and fission. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 1010232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauretti, E.; Pratico, D. Alzheimer's disease: phenotypic approaches using disease models and the targeting of tau protein. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2020, 24, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buee, L. Dementia Therapy Targeting Tau. Adv Exp Med Biol 2019, 1184, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.K.; Jara, C.; Park-Kang, H.S.; Polanco, C.M.; Tapia, D.; Alarcon, F.; de la Pena, A.; Llanquinao, J.; Vargas-Mardones, G.; Indo, J.A.; et al. Synaptic Mitochondria: An Early Target of Amyloid-beta and Tau in Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2021, 84, 1391–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Wan, H.; Chen, S.; Liu, G.P. Targeting tau in Alzheimer's disease: from mechanisms to clinical therapy. Neural Regen Res 2024, 19, 1489–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Choi, K.H.; Seo, D.W.; Lee, H.R.; Kong, H.S.; Lee, C.H.; Lee, W.S.; Lee, H.T.; Ko, J.J.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Association Between Functional Activity of Mitochondria and Actin Cytoskeleton Instability in Oocytes from Advanced Age Mice. Reprod Sci 2020, 27, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, J.A.; Chuckowree, J.A.; Dyer, M.S.; Dickson, T.C.; Blizzard, C.A. Epothilone D alters normal growth, viability and microtubule dependent intracellular functions of cortical neurons in vitro. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, D.A.; Mullins, R.D. Cell mechanics and the cytoskeleton. Nature 2010, 463, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlan, K.; Gelfand, V.I. Microtubule-Based Transport and the Distribution, Tethering, and Organization of Organelles. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Choi, K.H.; Oh, J.N.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, D.K.; Choe, G.C.; Jeong, J.; Lee, C.K. SOX2 plays a crucial role in cell proliferation and lineage segregation during porcine pre-implantation embryo development. Cell Prolif 2021, 54, e13097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.R.; Arrach, N.; Rhodes-Long, K.; Salem, W.; McGinnis, L.K.; Chung, K.; Bendikson, K.A.; Paulson, R.J.; Ahmady, A. Blastulation timing is associated with differential mitochondrial content in euploid embryos. J Assist Reprod Genet 2018, 35, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cash, A.D.; Aliev, G.; Siedlak, S.L.; Nunomura, A.; Fujioka, H.; Zhu, X.; Raina, A.K.; Vinters, H.V.; Tabaton, M.; Johnson, A.B.; et al. Microtubule reduction in Alzheimer's disease and aging is independent of tau filament formation. Am J Pathol 2003, 162, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Guzman-Sepulveda, J.R.; Kalra, A.P.; Tuszynski, J.A.; Dogariu, A. Thermal hysteresis in microtubule assembly/disassembly dynamics: The aging-induced degradation of tubulin dimers. Biochem Biophys Rep 2022, 29, 101199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, L.; Wetzel, A.; Granno, S.; Heaton, G.; Harvey, K. Back to the tubule: microtubule dynamics in Parkinson's disease. Cell Mol Life Sci 2017, 74, 409–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Cho, M.J.; Yu, W.D.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, J.H. Links of Cytoskeletal Integrity with Disease and Aging. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).