1. Introduction

Statins inhibit a critical step in cholesterol synthesis, transforming 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) into mevalonate via the enzyme HMG-CoA reductase. This mechanism gives statins their potent lipid-lowering effects, reducing cardiovascular risk and mortality. Furthermore, the mevalonate pathway influences endothelial function, inflammatory responses, and coagulation, making the effects of statins extend beyond cholesterol reduction.

However, these side effects are rare, and in carefully selected patient populations, the benefits of statins significantly outweigh their potential risks.

Statins are a widely used group of drugs, primarily because they are the first-line treatment for coronary heart disease. Although highly effective and generally safe, their potential for myopathic toxicity is a well-documented side effect [

1,

2,

3].

In 2010, an autoantibody against HMGCR was identified, enabling the detection of statin-associated autoimmune myopathy, which is clinically identical to immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM) [

4].

Autoimmune myopathies are rare diseases, with a prevalence of just 9–14 cases per 100,000 people. Of these, only ~10% are associated with either anti-SRP or anti-HMGCR myopathy [

5,

6].

Our objective is to present a rare case of myositis. While limited cases are described in the literature, this form of myopathic toxicity can occasionally manifest, triggering an autoimmune myopathy that persists even after statin discontinuation [

7,

8].

2. Case Report

Case 1

A 74-year-old woman with a history of chronic ischemic heart disease, treated with atorvastatin 80 mg for 3 years, presented for consultation. She had undergone cataract and pterygium surgery and reported no known drug allergies.

The patient complained of pain in the left gluteal region and a sensation of a gluteal mass persisting for several months. On physical examination, Trendelenburg gait; there was noticeable soft tissue swelling in the left gluteal region with increased tension but no palpable, well-defined masses. No signs of inflammation were observed. Joint and muscle function were normal, with no significant alterations. The FABERE maneuver was non-painful, but the FADIR maneuver elicited pain localized to the gluteal area.

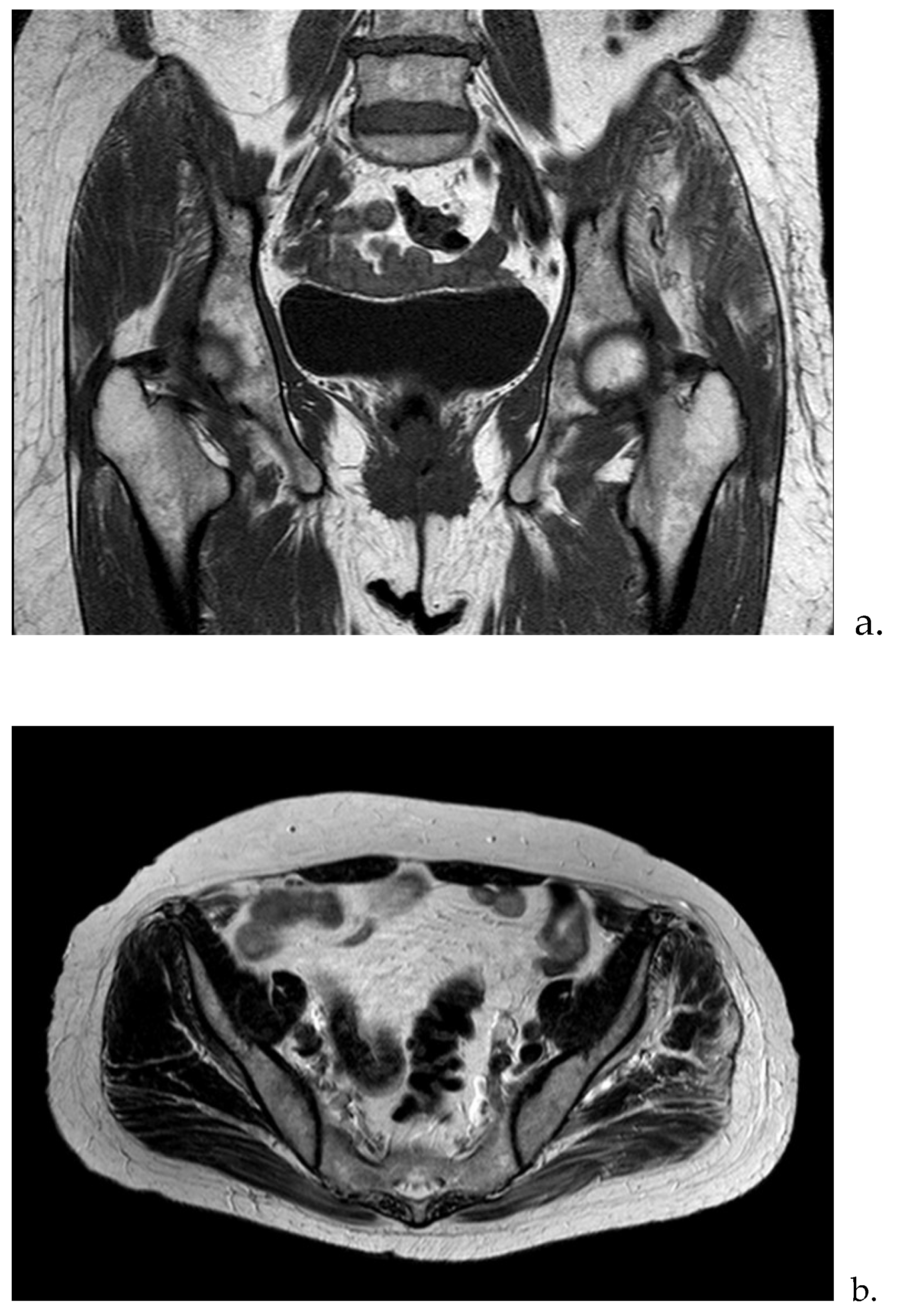

Complementary Test Results: Laboratory analysis: ESR: 80 mm/hr; Hemoglobin: 12.8 g/dL; Urea: 57 mg/dL; Creatinine: 0.93 mg/dL; GOT (AST): 16 U/L; GPT (ALT): 10 U/L; GGT: 13 U/L; CRP: 1.8 mg/dL; CPK: 563 U/L; Aldolase: 3.6 U/L (<7.6). Imaging studies: Ultrasound: Altered signal in the gluteus maximus and medius muscles. MRI: Signal abnormalities with enhancement involving the gluteus maximus and medius, consistent with findings of myositis. Etiologies considered include infectious or inflammatory origins, with traumatic causes deemed less likely (

Figure 1a,b).

The analytical study was expanded with a myositis profile, which revealed positive autoantibodies against HMGCR (>200 U/mL). No other myositis-related autoantibodies were detected, including Mi-2, Ku, PM-Scl100, Jo-1, SRP, PI-12, EJ, Oh, and Ro-52. Based on these results, a muscle biopsy was performed, confirming the diagnosis of statin-induced immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM), established approximately one year after symptom onset.

Treatment and Outcome: Statins were discontinued, leading to a reduction in pain and improved muscle strength in the following weeks, although weakness persisted in the thigh and gluteal muscles. Blood tests showed a decline in creatine kinase (CK) levels and liver transaminases.

Treatment was initiated with Prednisone 30 mg/day for three weeks, followed by a tapering regimen over five months. This resulted in the resolution of pain and swelling, with full recovery of functionality. The corticosteroid was then discontinued.

The patient has remained asymptomatic, with no recurrence of muscle symptoms for the past three years.

Case 2

A 76-year-old woman with a personal history of dyslipidemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease was being treated with atorvastatin 20 mg daily as secondary prevention following an ischemic stroke a year earlier.

She presented to our clinic with complaints of pain, swelling, and functional impairment preventing full extension of the left elbow that had persisted for several months. Additionally, she reported intermittent symptoms of paresthesia and dysesthesia in all the fingers of the ipsilateral hand.

Physical examination revealed swelling in the proximal region of the left forearm with an increase in perimeter, though the swelling was poorly defined. Muscle strength and joint range of motion were otherwise unaffected.

An ultrasound suggested a possible intramuscular hematoma due to a rupture of the proximal third of the brachioradialis muscle. The patient was referred to the Rehabilitation Service and received local treatment, which provided temporary and slight improvement.

After one year, swelling and functional impairment persisted, prompting additional analytical and imaging studies:

Laboratory analysis: ESR: 61 mm/hr; Hemoglobin: 12.8 g/dL; Urea: 57 mg/dL; Creatinine: 0.93 mg/dL; GOT (AST): 8.9 U/L; GPT (ALT): 11 U/L; GGT: 13 U/L; CRP: 1.6 mg/dL; CPK: 343 U/L; Aldolase: 3.5 U/L (<7.6). Myoglobin: 2,375 μg/l Imaging studies: Serology tests: Negative for hepatitis, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and Lyme disease. Autoimmune markers: Negative for antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and extractable nuclear antigen antibodies (anti-ENA).

Table 1.

Analytical values of the two cases.

Table 1.

Analytical values of the two cases.

| Lab |

Normal range |

Case 1 |

Case 2 |

| ESR |

0–30 mm/h |

70 |

61 |

| CRP |

< 0,3 mg/dL |

1.8 |

1.6 |

| CPK |

10 a 120 (mcg/L) |

563 |

343 |

| AST |

0-35 unidades/L |

16 |

8.9 |

| ALT |

4 a 36 U/L |

10 |

11 |

| Aldolasa |

1,0 y 7,5 unidades por litro |

3.6 |

3.5 |

Myositis profile

anti-HMG-CoA reductase antibodies |

|

|

|

| 0-20 CU |

>200 U/mL |

190 |

| MI-2 autoanbibodies |

Non detected |

Non detected |

Non detected |

| PL-7 autoanbibodies |

Non detected |

Non detected |

Non detected |

| PL-12 autoanbibodies |

Non detected |

Non detected |

Non detected |

| Ku autoanbibodies |

Non detected |

Non detected |

Non detected |

| EJ autoanbibodies |

Non detected |

Non detected |

Non detected |

| OJ autoanbibodies |

Non detected |

Non detected |

Non detected |

| SRP autoanbibodies |

Non detected |

Non detected |

Non detected |

| JO-1 autoanbibodies |

Non detected |

Non detected |

Non detected |

| PM-Ccl100 autoanbibodies |

Non detected |

Non detected |

Non detected |

| RO-52 autoanbibodies |

Non detected |

Non detected |

Non detected |

| MI-2 autoanbibodies |

Non detected |

Non detected |

Non detected |

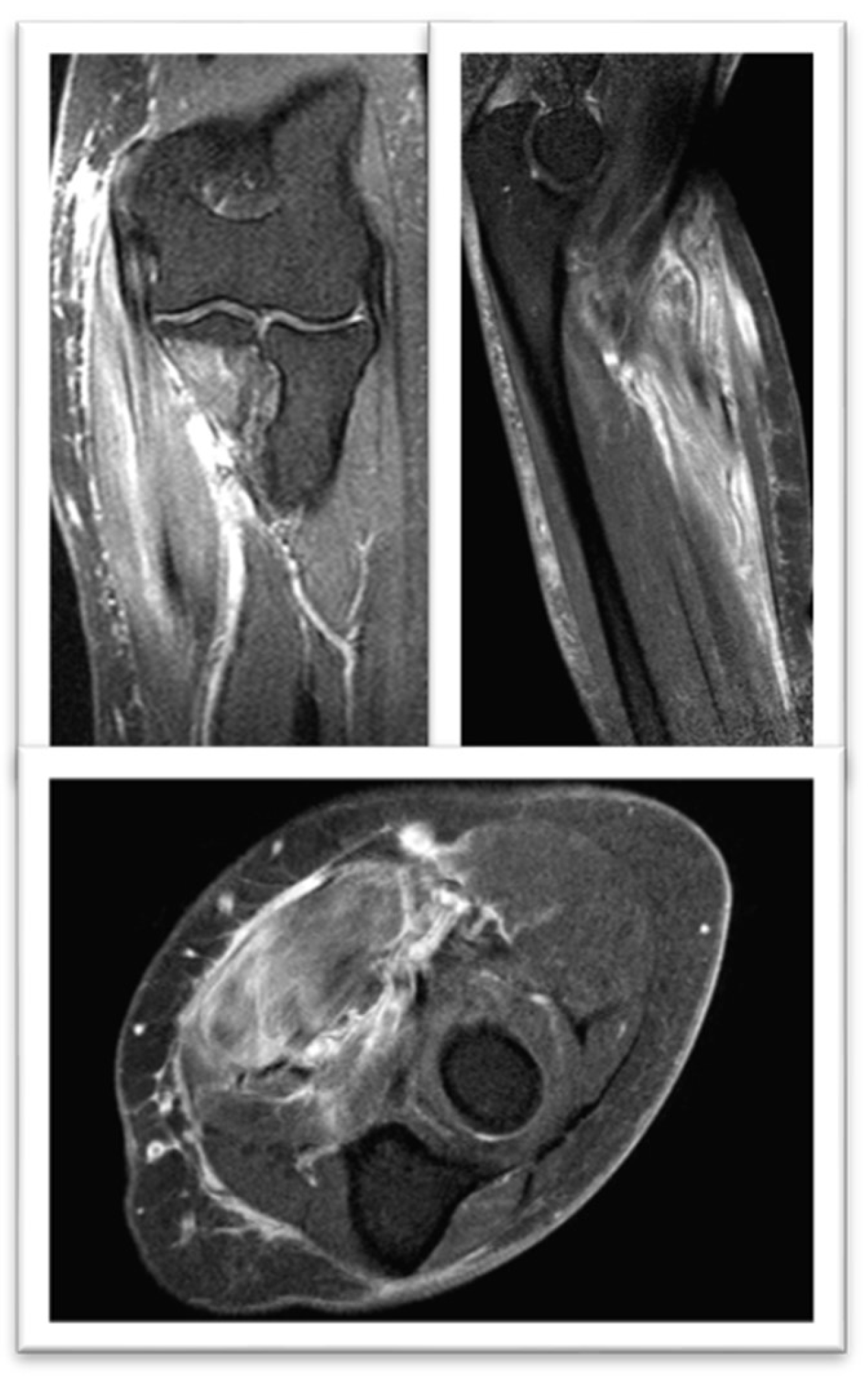

Magnetic Resonance Nuclear: Signal alteration with enhancement mainly in the flexor carpi radialis muscle. Findings in relation to myositis (

Figure 3).

Analytical study is completed with Myositis profile: IMNM secondary to statins was confirmed by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with positive autoantibodies (AK) against HMGCR (>200 U/mL).

Given the findings, it was decided to perform a muscle biopsy: . showed necrotizing myopathy with regeneration of muscle fibers, a large number of necrotic muscle fibers and few inflammatory cells. compatible with necrotising inflammatory myopathy.

Given the diagnostic criteria of IMNM secondary to statins, it was decided to withdraw cholesterol-lowering treatment. After three months, despite the improvement in his symptoms, and the altered signal in the affected muscles in the control MRI (

Figure 4), the persistence of muscle weakness did not improve and the CK values increased, so Treatment was started with prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day.

After several years changing lipid-lowering treatment, she remains asymptomatic.

3. Discussion

Statins, hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A-reductase (HMGCR) inhibitors, significantly reduce the risk of cardiovascular events and are generally safe but are associated with muscle side effects, which are usually transient [

9].

Statins are among the most effective treatments for the primary and secondary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Since the introduction of lovastatin in 1987, an estimated 25 million patients worldwide use these drugs. However, statin-induced myopathy (SIM) is a known adverse reaction that limits their use [

4]. Myalgia caused by statin use is more common and challenging to quantify, affecting an estimated 2–20% of treated patients

Most statins have been found to possess the potential to cause muscle damage [

7]. Myalgia is the most frequently reported and limiting symptom of statin use [

8]. Muscle symptoms, especially at high doses, may be more common and impactful on daily life than previously recognized. Clinical signs of myopathy include pain, weakness, stiffness, and muscle cramps, which may or may not be associated with elevations in serum CK levels [

1,

2,

3].

In addition to the muscular condition described, there are other rarer conditions of muscular involvement , incidence of immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM) is estimated to be 9–14 cases per 100,000 exposed patients

6 and in contrast statin associated IMNM is exceptionally rare, 2-3 of every 100.000 patients trated [

10]. A review of patients with IMNM revealed that, unlike statin-induced rhabdomyolysis, which typically occurs early in treatment, IMNM symptoms emerged after a median of 38-40 months on statins treatment

5; This finding suggests that long-term exposure to statins is likely required to trigger an autoimmune response in most cases [

11].

Myositis has been reported in 0.5% of patients, particularly those on high doses of statins. The mechanism by which statins induce toxicity is not fully understood. Statins inhibit the conversion of HMG-CoA to mevalonic acid, a key step in cholesterol synthesis. They also reduce the synthesis of coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10), which plays an essential role in muscle cell energy production. It is hypothesized that this reduction in CoQ10 may contribute to muscle damage. Treatment with simvastatin (10–40 mg daily for over 12 months) has been shown to reduce CoQ10 levels and impair mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation capacity in skeletal muscle. Regarding the pathophysiology of IMNM, it is not entirely understood. Current hypotheses suggest that muscle damage is mediated by anti-HMGCR antibodies, which target the HMG-CoA reductase enzyme expressed in muscle cells 12. This enzyme becomes more abundant in muscle cells after statin use. The human leukocyte antigen DRB1*11:01 allele has been associated with a higher incidence of anti-HMGCR antibodies, suggesting a genetic predisposition to this condition.

Some statins, particularly atorvastatin [

12], are more frequently associated with IMNM compared to others. Pravastatin and fluvastatin, which are more hydrophilic and have lower muscle penetration, appear to carry a lower risk. Additionally, these statins interact less with other medications as they are not extensively metabolized through CYP3A4.

Risk factors for statin-associated myopathy include hypothyroidism, acute or chronic renal failure, obstructive liver disease, and the use of certain drugs or toxic substances like alcohol. Genetic factors and ethnicity also play a role; for example, Chinese patients are recommended to take lower doses, particularly of simvastatin [

8].

European Neuromuscular Centre criteria recognize antiSRP myopathy anti-HMGCR myopathy, and autoantibody-negative IMNM as three distinct subtypes of IMNM.; anti-HMGCR myopathy as a distinct subtype of IMNM, often associated with statin exposure and linked to HLA-DRB111:01 and HLA-DRB107:01. CK levels may not always reflect disease activity, as muscle strength recovery can lag behind biochemical improvement [

6,

13].

The clinical presentation of anti-HMGCR myopathy includes subacute, progressive, symmetrical muscle weakness with markedly elevated CK levels, which persist despite statin discontinuation [

14]. Medical providers should consider IMNM in statin-exposed patients presenting with proximal muscle weakness and very high CK levels, even after discontinuing statins

Myalgia may or may not be present, approximately one-third of patients may experience myalgia and dysphagia [

15]. CK levels are correlated with muscle strength and can serve as surrogate markers of disease activity although serum CK levels may not accurately reflect disease activity [

13].

Muscle MRI has only limited value in diagnosing patients with IMNM because it discriminates poorly between patients with IMNM compared to other types of myositis; Intramuscular hyperintensities on the STIR sequences reflect active muscle edema associated with inflammation or myofiber necrosis. Muscle MRI may be a useful tool to monitor the evolution of muscle disease over time [

5,

6,

13].

Detection of anti-HMGCR autoantibodies is diagnostic, with high sensitivity and specificity for statin-induced IMNM (94.4% and 99.3%, respectively). These antibodies are not associated with self-limited statin myopathy or genetic muscle diseases [

6,

13].

In patients with persistent muscle weakness despite statin discontinuation, testing for anti-HMGCR antibodies is recommended to differentiate this condition from more common statin-related myotoxicities. For antibody-negative cases, alternative diagnoses should be considered.

Histopathological findings typically include necrotic and regenerating muscle fibers with minimal inflammation [

16]. Other characteristic findings include upregulation of MHC class I in muscle fibers and deposition of membrane attack complexes on blood vessels and non-necrotic muscle fibers .Muscle biopsy, if performed, typically shows necrosis with muscle fiber regeneration and minimal inflammation [

17].

The differential diagnosis includes other inflammatory myopathies, metabolic and genetic muscle disorders, and toxic statin myopathy [

18]. For example, dermatomyositis can be ruled out by the absence of skin lesions and perifascicular atrophy on biopsy. The absence of significant endomysial mononuclear infiltrates makes polymyositis less likely, while the lack of vacuoles excludes inclusion body myositis.

Prompt and immediate discontinuation of the statin drug is required if the patient is being treated with IMNM [

19] Treatment for IMNM typically requires immunosuppression in addition to discontinuing statins [

20]. High-dose corticosteroids are often used initially, followed by steroid-sparing agents such as mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, or methotrexate. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is effective, particularly in HMGCR IMNM, and may even be used as monotherapy. In refractory cases, rituximab has shown promise [

21].

Patients often require prolonged immunosuppressive therapy, and relapses are common during tapering n. The optimal treatment duration remains unknown [

13], but consensus suggests maintaining the lowest effective steroid dose and tapering steroid-sparing agents after at least two years of disease control. Chronic IVIG therapy may be necessary for many patients [

20].

Unfortunately, clinical trials are lacking, and treatment strategies rely on observational studies and expert opinion [

22,

23]. Approximately 50% of patients continue to experience muscle weakness after two years of treatment [

24]. Younger patients tend to have worse prognoses and more severe disease... □