1. Introduction

Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM) represent a heterogeneous group of autoimmune diseases characterized by proximal muscle weakness, elevated muscle enzyme levels, presence of various myositis-specific and myositis-associated autoantibodies, and distinct electromyographic abnormalities. The primary subtypes comprise dermatomyositis (DM- including amyopathic dermatomyositis), antisynthetase syndrome (ASS), immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM), inclusion body myositis (IBM), polymyositis (PM) and overlap myositis (OM), each distinguished by clinical, histopathological, and immunological features [

1].

There is no precise definition of myocardial involvement in IIM, the incidence varies from 6% to 75% in literature. Manifest cardiac abnormalities are relatively rare. The primary cardiovascular manifestations in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM) are myocarditis and pericarditis, which can lead to arrhythmias and heart failure. Subclinical (ECG) manifestations, on the other hand, are more common [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Cardiovascular diseases are currently the leading cause of mortality worldwide [

10]. Patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases, including IIM, exhibit a heightened risk of developing cardiovascular disease when compared to general population. Several studies reported a higher prevalence of atherosclerosis in patients with autoimmune diseases also with IIM compared with the general population, leading to increased cardiovascular (CV) morbidity and mortality [

3,

9,

11,

12,

13,

14]. The higher cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk in patients with rheumatic diseases have multiple reasons. In addition to traditional risk factors, such as hyperlipidemia, atherosclerosis, smoking, advanced age, hypertension, positive family history, obesity, these patients have other major risk factors. While the presence of chronic inflammation plays a key role in cardiovascular disease pathogenesis in rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs), the negative effects of chronic glucocorticoid therapy on metabolism cannot be overlooked [

3,

11,

12,

13,

14].

Hyperlipidemia is the major risk factor of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in general population. Statins are the first-line treatment due to their effectiveness in lowering low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) and reducing cardiovascular risk. Other medications include ezetimibe, which reduces cholesterol absorption, and proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors, which further lower LDL-C levels in high-risk patients. Statins are inhibiting the enzyme 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme-A reductase (HMG-CoA). The most common side effects of statins are statin-associated muscle symptoms which include various types of mechanism and pathophysiology. It is important to distinguish the statin myotoxicity and statin-induced IMNM. While statin myotoxicity usually appears early after statin initiation and resolves with statin cessation, the IMNM appears after months to years after statin initiation, does not resolve with statin cessation and we can discover the presence of the anti-3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme-A reductase antibody (anti-HMGCR)[

15]. Meanwhile we have an increasing knowledge about the pathomechanism and outcome of necrotizing myopathy, fear of statin induced myopathy decrease the frequency of use although its role in CVD risk reduction is obvious [

16]

Based on the latest EULAR recommendations rheumatologists are responsible for CVD risk assessment and management in collaboration with primary care providers, internists or cardiologists and other healthcare providers. In patients with RMDs as myositis they recommend thorough assessment of traditional CVD risk factors. The use of cardiovascular prediction tools as for the general population is recommended. Lipid management should follow recommendations used in the general population [

14]. However, statin treatment in myositis patients has risks and special concerns and no international guidelines had been established yet regarding the regularity of screening or risk reduction strategies in these patients.

Our aim was to assess (1) the CVD risk of our patients using the SCORE2 prediction system, carotid artery Doppler ultrasound, intima-media thickness (IMT) measurement and biomarkers; (2) recommend individual lipid-lowering treatment (statin or ezetimibe); (3) follow the efficacy and adverse events of therapy in a 6 months’ treatment period. Primary endpoint was the change in CVD risk determined by the SCORE2 method after treatment. Secondary endpoint was to assess the proportion of patients in the cohort who can reach a lower SCORE2 category after treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

80 patients treated and regularly controlled due to IIM participated in the study at the Division of Immunology, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary. Inclusion criteria were that the patient fulfils the definition of definite or probable inflammatory myopathy based on the EULAR/ACR classification criteria [

17] and gave informed written consent. The laboratory was approved by the National Public Health and Medical Officer Service (approval number: 094025024).

Epidemiology data, general characteristics of IIM disease as symptoms at disease onset, autoantibody profile, comorbidities, and previous lipid-lowering and immunosuppressive treatment were collected during screening visit.

2.2. Sample Collection and Biochemical Measurements

All venous blood samples were drawn after a 12 h fasting. Routine metabolic laboratory parameters: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), hemoglobin A1C (HgbA1c), total cholesterol, triglyceride, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), LDL-C, apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1), apolipoprotein B100 (ApoB100), ; as well as muscle necroenzymes (creatine kinase (CK)), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were measured from fresh sera with Cobas c600 analysers (Roche Ltd., Mannheim, Germany) from the same vendor. The commercially available methods were used following the manufacturers’ protocols. All laboratory measurements have taken place at the Department of Laboratory Medicine, University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary.

Serum concentrations of oxidized LDL (oxLDL) were detected by a commercially available solid phase two-site enzyme immunoassay (ELISA) kit (Mercodia AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Measurements of oxLDL levels in the sera were performed according to the recommendations of the manufacturer. The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variations were 5.5–7.3% and 4.0–6.2%, respectively, and the sensitivity was <1 mU/L.

Soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM-1) and soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (sVCAM-1) levels were determined using a sandwich ELISA kit (R&D Systems Europe Ltd., Abingdon, UK). ELISA procedures were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Intra- and inter-assay CVs ranged from 3.7% to 5.2% and 4.4% to 6.7% for sICAM-1 and 2.3% to 3.6%, respectively, and between 5.5% and 7.8% for sVCAM-1. Values were expressed in ng/mL.

2.3. Cardiovascular Disease Risk Assessment

CVD risk was estimated using the SCORE2 predilection model and carotid artery imaging and determination of carotid intima media thickness (IMT). SCORE2 is a standardized, validated risk assessment model to estimate the 10-year risk of cardiovascular diseases [

18]. It divides Europe into low, medium and high-risk regions (Hungary is a high-risk area). Risk stratification assessment is based on gender, age, smoking status, systolic blood pressure, total and HDL cholesterol levels. We used online available SCORE2 calculator via the website of European Society of Cardiology (ESC) [

19]. Based on the SCORE2 values, the patients were classified into low (<2.5%), medium (2.5-7.5%) and high risk (>7.5%) groups. If the 10-year risk is greater than 7.5%, lipid-lowering treatment is recommended according to international guidelines.

Identification of asymptomatic carotid plaques by Doppler ultrasound and IMT were determined at the Neurology Clinic of the University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary. Measurement was performed using the Philips Epiq 5 (Philips International B.V., Amsterdam, The Netherlands) device with a 5-10 MHz transducer. In the first step, longitudinal and cross-sectional images were taken to rule out the presence of possible atherosclerotic plaques, as they distort the measurement of vessel wall thickness. If plaque was not visible, longitudinal images were taken 10 mm proximal to the division of the common carotid during end diastole, which were evaluated using the US Q-App IMT software (Philips International B.V.). The IMT is the distance between two echogenic bands - the lumen-intima border and the media adventitia border - which is given in millimetres. We performed 10 measurements on both sides, the average of which was calculated as the IMT value. The normal value of IMT is 0.40-0.80 mm. To score the results, we used a carotid plaque score system published by Ihle-Hansen et al.[

20]: no plaque = 0 points, <50% stenosis = 1 point, 50-69% = 2 points, 70-100% = 3 points, plus 1 point if the plaque has a hypoechoic or ulcerated surface.

2.4. IIM Disease Activity and Muscular Side Effect of Lipid-Lowering Treatment

Myositis disease activity was evaluated based on IMACS core set measures using “Physician global activity”, “Patient global activity”, visual analogue scales (VAS), manual muscle test (MMT) scores and CK levels. Muscle pain was also evaluated by VAS scale.

Lipid lowering therapy was administered after a shared decision with the individual patient. 10 mg/day rosuvastatin was started in cases with medium and high CV risk patients (SCORE2≥7.5 and/or the presence of asymptomatic carotid plaque), in accordance with international recommendations. 10 mg of ezetimibe per day was recommended in case of statin contraindication as follows: anti-HGGCR antibody positivity, previous statin induced muscle pain or CK elevation and actual significantly high CK level (3x above the normal upper limit).

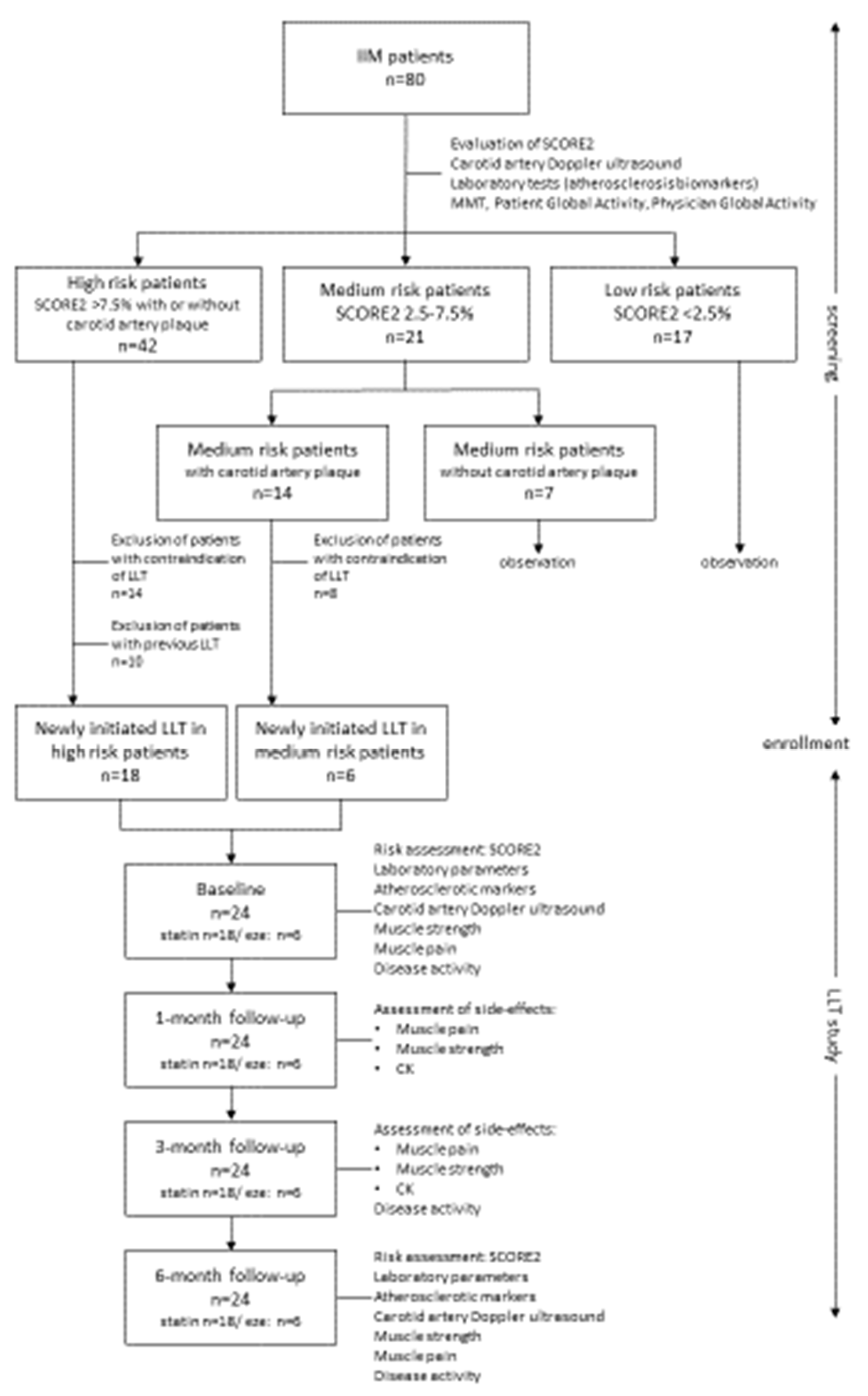

All diagnostic and laboratory procedures were repeated in all cases after one, 3 and 6 months independently of previous and actual lipid-lowering therapy. Carotid artery measurements only were tested at screening and 6 months after as no significant change was expected in a short period of time. The study design is shown on

Figure 1.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical calculations were performed using the Statistica 13.5.0.17 software (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). Graphs were made using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Normality of variables was checked with Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. We performed the paired T test for normally distributed variables, and the Wilcoxon Matched Pairs test for skewed variables to detect the statistical differences after 6-month follow-up. Data are presented as mean±standard deviation or median (lower-upper quartiles). The statistical difference between categorical variables was analysed with Chi-square test. A p value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Bonferroni-adjusted significance tests were applied to adjust p-values for multiple comparison. When the calculated p-values were less than the Bonferroni threshold (P < 2.2x10-3), the difference was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of IIM Cohort

General characteristics of study cohort are summarized in

Table 1. The mean age of IIM patients included in the study (n=80) was 56.2±13.4 years. The cohort is characterised with female dominancy (67.5% women vs. 32.5% men). The median duration of myositis disease was 9 (5-15) years. Patient reported actual smoking in 17.5% (n=14) of cases. 49% (n=39) of patients suffered from PM (including antisynthetase syndrome and necrotizing myopathy) and 51% (n=41) had DM. 60% (n=48) of our patient had detectable myositis specific (MSA) and 43.7% (n=32) had myositis associated autoantibody (MAA) positivity. Anti-HMGCR antibody positivity was proved in only 2.5% (n=2) cases. The most common symptoms at IIM disease onset were muscle weakness (96.25%; n=77), arthralgia/arthritis (81.25%; n=65), and skin rashes (70%; n=56). Internal organ involvement had been reported less: interstitial lung disease in 37.5% (n=30), dysphagia in 36.25% of cases (n=29). Definitive myocarditis occurred in 16.25% (n=13) of our patients. Leading traditional risk factors at screening were hypertension (71.3%) and diabetes mellitus (25%). The median disease activity was 1 (0-2.15), median CK value was 90.5 (62-185) IU/mL at screening referring to low disease activity. Median, mean, standard deviation (SD) and quartile values of metabolic parameters, SCORE2, IMT and biomarkers are presented in

Table 2.

3.2. Patient Selection for Lipid Lowering Therapy (LLT)

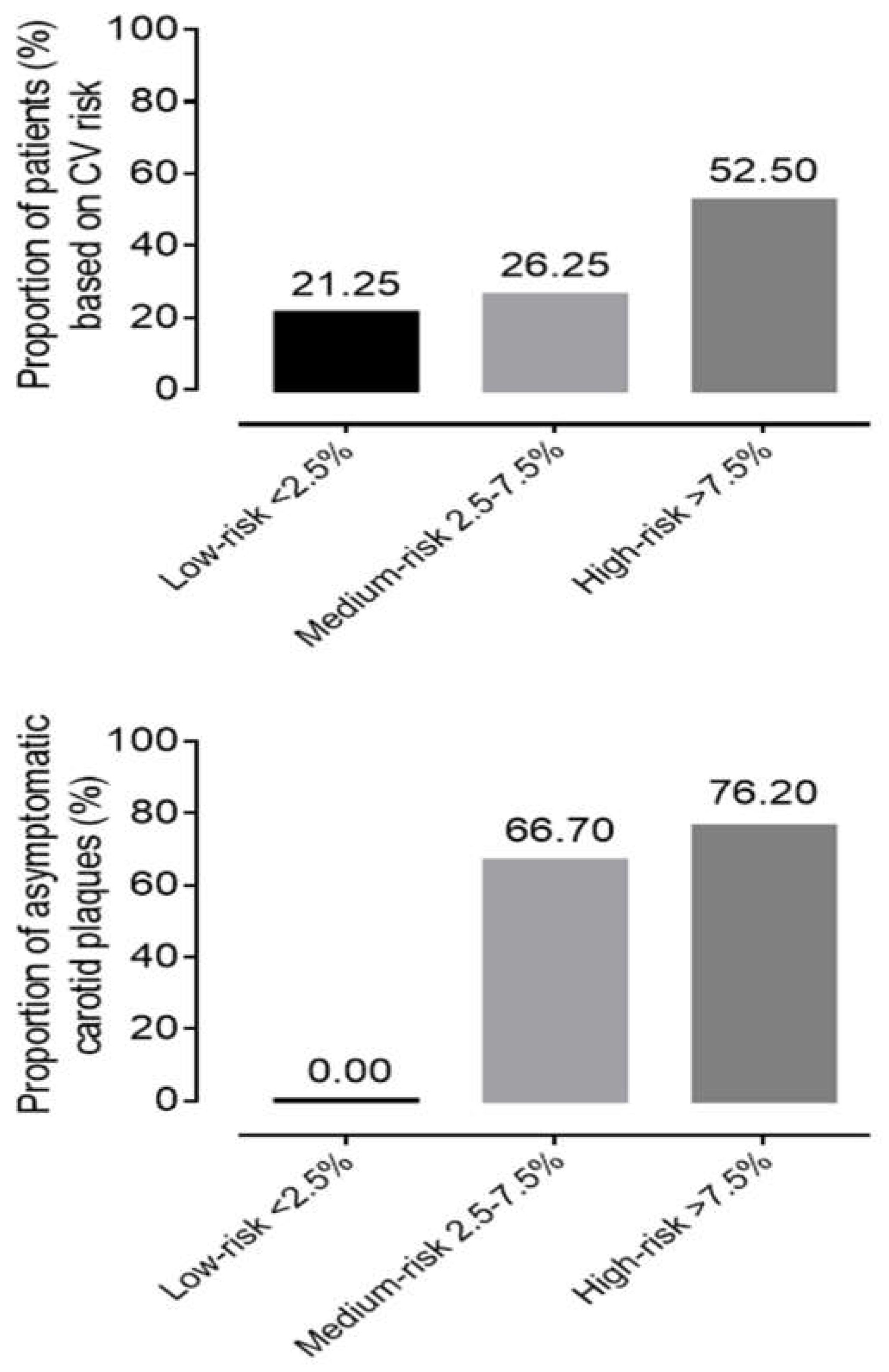

During CV risk stratification, based on SCORE2, 21.25% (n=17) of patients had low, 26.25% (n=21) had medium, and 52.5% (n=42) had high risk at screening. Evaluating the carotid artery ultrasound results, mean IMT were in normal range on both right and left side, but in 73.13% (n=49) of patients carotid score was 1 point, which means asymptomatic atherosclerotic plaques are present. Hyper echogenic, ulcerated or pronounced plaques with more than 50% of stenosis were detected only in 2.99% (n=2) of subjects. In the low SCORE2 risk group, we could not detect any carotid plaque. Meanwhile in 66.7 % (14/21) of patients in the medium and 76.2 % in the high-risk group had asymptomatic carotid artery plaques (

Figure 2).

In high-risk group, 10 patients were on continuous lipid-lowering therapy without any muscular side effects. We identified contraindication in 14 cases from the high-risk and in 10 cases from the medium risk group. We started 10 mg rosuvastatin per day for 18 patients and 10 mg ezetimibe per day for six patients. Regular check-up has been organised 1, 3 and 6 months thereafter to monitor laboratory parameters, muscle strength and side effect rate (

Figure 1).

3.3. Change of Variables During the Six-Month Lipid Lowering Therapy

Changes in metabolic, atherosclerotic markers and disease activity scores after six-month lipid-lowering treatment are summarized in

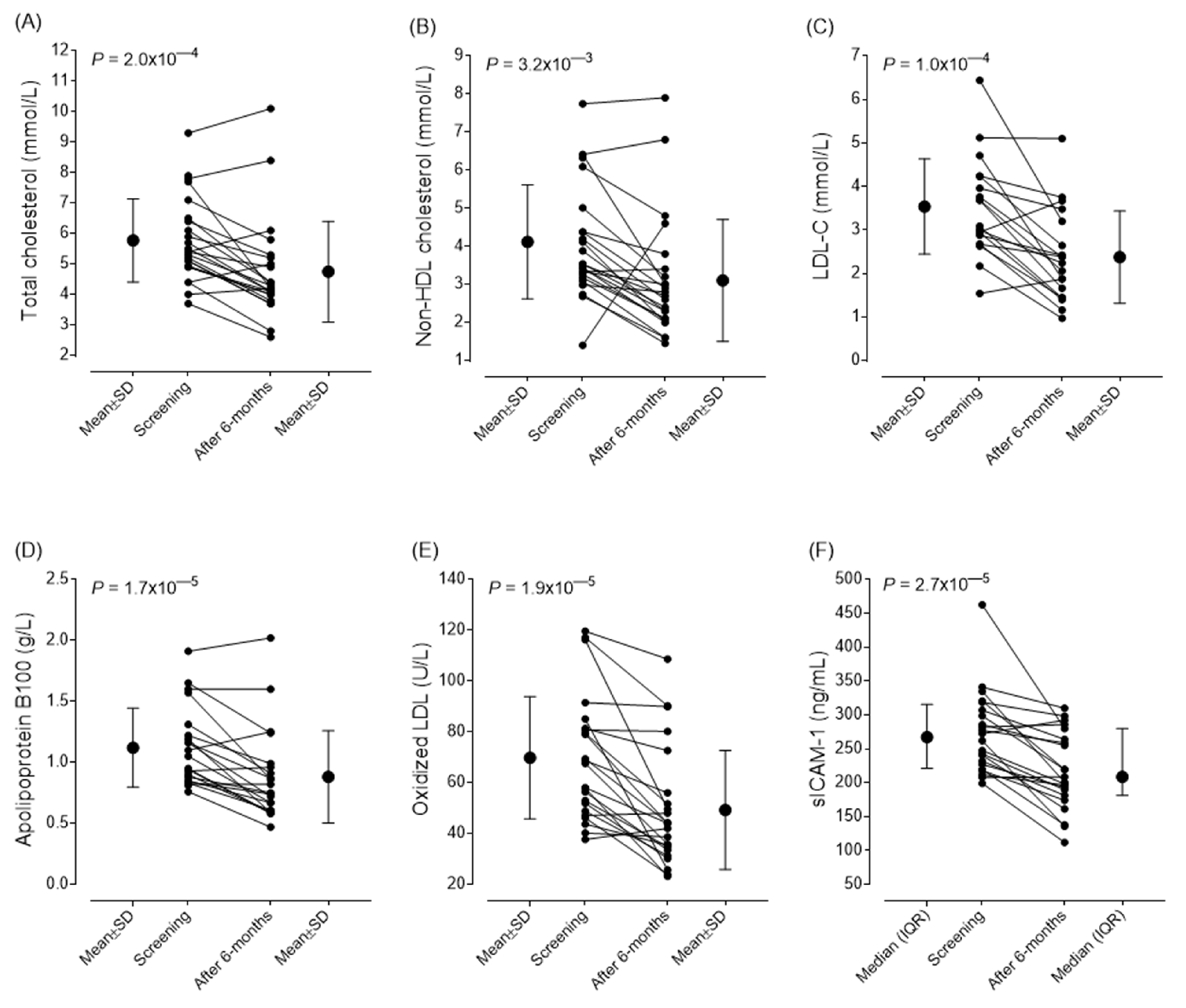

Table 3. After six-month follow-up we observed significant decrease in the mean values of total cholesterol (from 5.78±1.36 to 4.75±1.69 mmol/L; P<0.001), non-HDL cholesterol (from 4.1±1.49 to 3.1±1.64 mmol/L; P<0.001) and LDL-C levels (from 3.537±1.095 to 2.377±1.06 mmol/L; P<0.001). Also found significant improvement in the values of oxLDL (from 69.83±24.01 to 49.29±23.39 U/L; P<0.001), ApoB100 (from 1.12±0.32 g/l to 0.88±0.33 g/L; P<0.001) and sICAM-1 (from 267.2 (217.9-311.35) to 208.7 (181.2-279.2) ng/mL; P<0.001). In parallel, the SCORE 2 score also improved (from 9.75±4.36 to 8.478±3.58; P=0.014). The mean IMT of carotid arteries did not show any changes during the observational period, there were no progression in neither thickness nor plaque stage. Changes in vascular markers and CV score are summarized in

Table 3. The individual changes in lipid parameters, early markers of atherosclerosis and sICAM-1 levels are demonstrated in

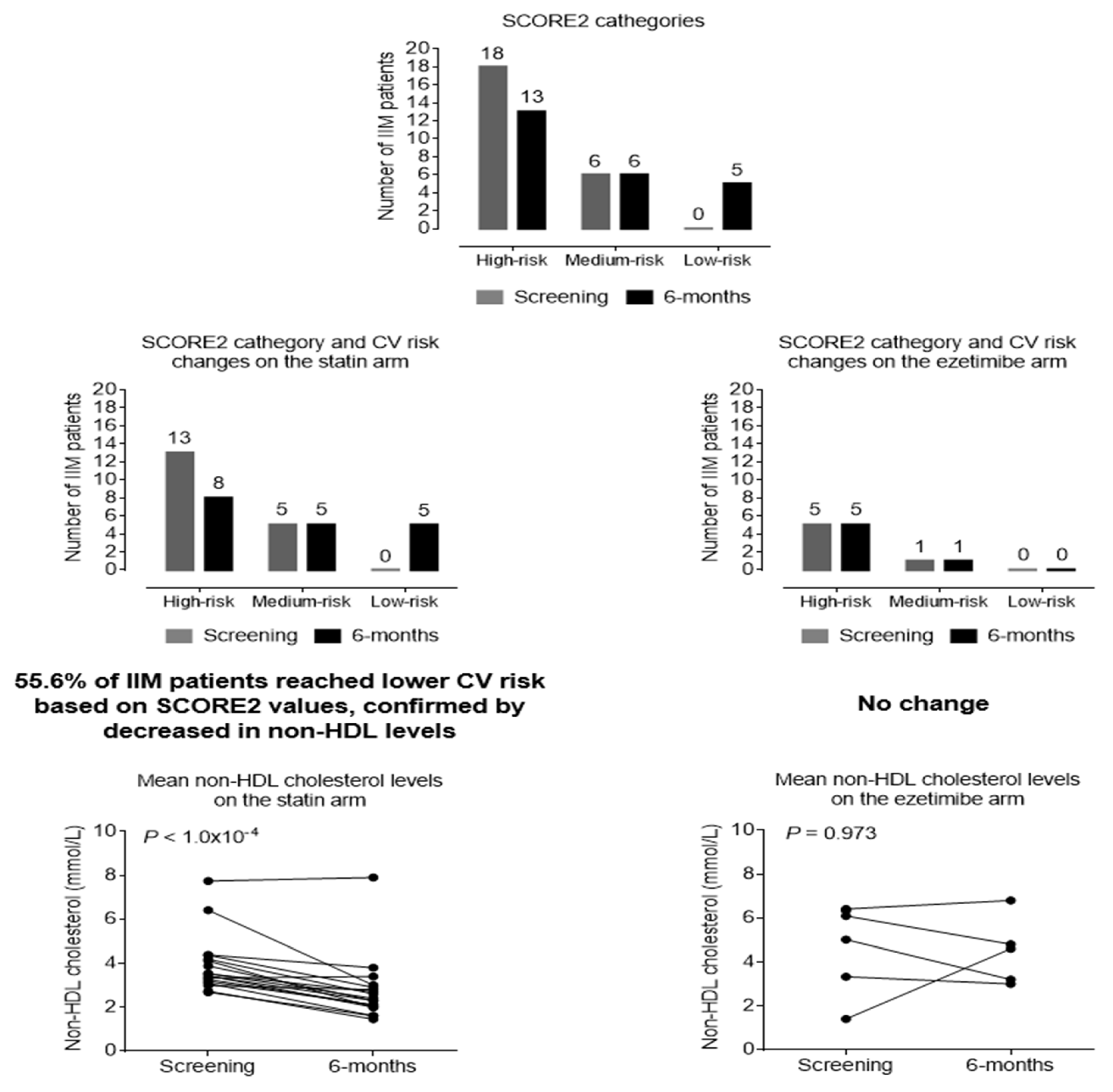

Figure 3. Based on the SCORE2 values, 37.5% of the patients reached a lower risk category after treatment; thus, their cardiovascular risk was remarkably reduced (

Figure 4). During the follow-up period, no side effects of the lipid-lowering treatments was observed. The muscle pain VAS score determined by the patients (P=0.463) and the CK levels (P=0.212) did not changed significantly. We could not observe any treatment-induced myopathy, myositis relapse or progression during the follow-up period. No significant change in muscle necroenzymes, disease activity and muscle strength was detected (

Table 3).

Based on SCORE2 improvement and non-HDL cholesterol level changes, there is a difference between ezetimibe and rosuvastatin in favour of statin either in lipid lowering or risk reduction. On the statin arm 56.6% of patients reached lower risk category, meanwhile on ezetimibe arm the risk status did not change in a half year. Non-HDL cholesterol levels did not change on the ezetimibe arm (P=0.973), but markedly decreased in the statin group (P<0.001) (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

The increased risk of accelerated atherosclerosis and cardiovascular diseases in systemic rheumatic diseases and IIM, is well-known. Several independent studies reported that in IIM increased risk of cardiovascular mortality is related to the cardiac involvement of IIM and early atherosclerosis; mostly due to the traditional risk factors, the inflammatory milieu and the applied corticosteroid therapy. This risk is 2.2-2.3-fold increase in the first 5 years of IIM diagnosis [

3,

8,

12,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Some studies [

26] reported that this increased CVD risk is mostly affected by traditional risk factors; while, others suggested high risk in IIM patients compared to healthy controls independently to traditional cardiovascular risk [

12]. IIM patients’ major cardiovascular events (stroke and acute coronary disease) occur with higher incidence compared to general population [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Electrocardiography, echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, determination of laboratory markers and risk factor evaluation are widely used for CVD risk stratification [

3,

8,

12,

21,

22,

23]. Recommendations are scarce considering exact lipid-lowering and CVD prevention protocols and frequency of risk assessment in IIM patients. Our results also confirm that the CVD risk of IIM patients is high even after a longer disease duration. High frequency of asymptomatic plaques suggests that beside the procedures listed above, screening by carotid artery Doppler ultrasound is also recommended shortly after the diagnosis of IIM and regularly thereafter. As we detected high CVD risk in patients with an average disease duration of 9 (5-15) years, we could state that it is necessary to repeat all the risk assessments regularly in the first 5 years after IIM diagnosis but also later during disease course.

As the international guidelines postulated lipid management should follow recommendations used in the general population [

14]. Small case studies have reported severe muscular complications with lipid lowering therapies in patients with metabolic myopathies [

32]. Meanwhile other, well-organized studies proved that statins are well tolerated in myositis patients besides careful application [

32,

33]. In addition to CV benefits, statins have been shown to have down regulatory effects on multiple inflammatory pathways [

34]. Based on our findings in case of high risk and/or asymptomatic plaque, lipid-lowering treatment is recommended, where statin treatment is preferred - as seems to be more effective than ezetimibe - in IIM patients without contraindication. Due to carefully applied lipid-lowering treatment, the CVD risk of myositis patients was effectively reduced without any muscular adverse event. Lipid levels (total cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol), early atherosclerosis biomarkers (oxLDL, sICAM-1, ApoB100 concentrations) significantly decreased and there was no progression in IMT. Although the primary goal according to the guidelines is to reduce LDL-C levels, the risk of cardiovascular complications is more closely related to the serum level of ApoB100, as this parameter indicates not only the LDL particles but also the amount of highly atherogenic triglyceride-rich lipoproteins [

35]. Indeed, reducing the non-HDL-C level is also important, for the same reason. Therefore, a 21.4% reduction in ApoB100 and a 24.6% reduction in non-HDL-C levels indicates the risk reduction caused by the improvement of global dyslipidemia. The stabilization of atherosclerotic plaques, including the reduction of lipid content and intravascular inflammation within the plaque, is a further important outcome of lipid-lowering treatment [

36]. However, measuring these parameters during routine clinical care is not currently feasible, and the IMT measurement we used is definitely not suitable for this purpose. Nevertheless, a favourable change in the sICAM-1 level, which characterizes endothelial function, may be an indirect indicator of plaque stabilization.

Since statins moderately increase the risk of developing newly onset type 2 diabetes mellitus [

37], it is important to emphasize that after 6 months of treatment, the HbA1c value, which reflects carbohydrate metabolism, did not change significantly. Therefore, in IIM patients, the diabetogenic effect of statin treatment is likely to be less pronounced compared to the previously examined general patient population, in which the proportion of prediabetic and overweight patients may be higher.

Some possible limitations of the study must be mentioned. Due to the limited number of patients, the results need to be confirmed by further, large-scale, multicenter studies. The 6-month follow-up is certainly not long enough to confirm the beneficial effect of lipid-lowering treatment on plaque regression. Therefore, we plan to continue the long-term following the patients. Measurement of further inflammatory and vascular biomarkers could contribute to exploring the favorable effects of lipid-lowering treatment. Nevertheless, the study provides important data supporting the effectiveness and safety of lipid-lowering treatment and underlines its role in cardiovascular risk reduction.

5. Conclusions

Based on our findings we could state that cardiovascular risk of patients with myositis is high. As the treating physician - mostly rheumatologist or neurologist - follows regularly IIM patients, it is necessary to advice or indicate CVD risk stratification in time and state recommendation on lipid lowering therapy considering risks of muscular adverse event as anti-HMGCR antibody positivity, disease activity or previous statin-induced complaints. Statin treatment can reach significant efficacy in risk diminution without side effects beside careful care and follow-up.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. Conceptualization M.N-V. and Z.G.; methodology: H.L. and M.H; data collection: D.Sz.; H. M., V.B; K.Sz.;T.B.; writing—original draft preparation D.Sz. and M.N-V; writing—review and editing Z.G; M.H; visualization H.L. and D. Sz. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Research Grant of the Hungarian Society of Allergology and Clinical Immunology supported the work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval for this study was provided by the Regional Ethics Committee of the University of Debrecen (DE RKEB/IKEB 6215-2022). All procedures complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ACR |

American College of Rheumatology |

| anti–HMGCR |

anti- 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme-A reductase antibody |

| ALT |

alanine aminotransferase |

| ApoA1 |

apolipoprotein A1 |

| ApoB100 |

apolipoprotein B100 |

| ASS |

antisynthetase syndrome |

| AST |

aspartate aminotransferase |

| CV |

cardiovascular |

| CVD |

cardiovascular diseases |

| CK |

creatine kinase |

| DM |

dermatomyositis |

| ECG |

electrocardiography |

| ELISA |

enzyme linked immunoassay |

| ESC |

European Society of Cardiology |

| EULAR |

European Alliance of Associations for Reumatology |

| EZE |

ezetimibe |

| GGT |

glutamyl transpeptidase |

| HDL-C |

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HgbA1c |

hemoglobin A1C |

| HMG-CoA |

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme-A reductase |

| hs CRP |

high-sensitivity C-reactive protein |

| IBM |

inclusion body myositis |

| IIM |

Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM) |

| IMNM |

immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy |

| IMT |

carotid artery intima media thickness |

| LDH |

lactate dehydrogenase |

| LDL-C |

low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol |

| LLT |

lipid-lowering therapy |

| MAA |

myositis associated autoantibody |

| MMT |

manual muscle test |

| MSA |

myositis specific autoantibody |

| OM |

overlap myositis |

| PCSK9 |

proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 |

| PM |

polymyositis |

| RMD |

rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases |

| sICAM-1 |

soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 |

| sVCAM-1 |

soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 |

| oxLDL |

oxidized LDL |

| VAS |

visual analogue scales |

References

- Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Lundberg IE, Fujimoto M, Vencovsky J, Aggarwal R, Holmqvist M, Christopher-Stine L, Mammen AL, Miller FW Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;;7(1):86.

- Diederichsen, Louise P. Cardiovascular involvement in myositis. Current Opinion in Rheumatology 2017;29(6): p 598-603.

- Shah M, Shinjo SK, Day J, Gupta L. Cardiovascular manifestations in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Clin Rheumatol. 2023, 42, 2557–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoo T, Stokes MB, Teo K, Proudman S, Basnayake S, Sanders P, Limaye V. Cardiac involvement in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies detected by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Rheumatol. 2019, 38, 3471–3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, IE. The heart in dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006; 45 Suppl 4:iv18-21.

- Péter A, Balogh Á, Csanádi Z, Dankó K, Griger Z. Subclinical systolic and diastolic myocardial dysfunction in polyphasic polymyositis/dermatomyositis: a 2-year longitudinal study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2022, 24, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myhr, K.A., Pecini, R. Management of Myocarditis in Myositis: Diagnosis and Treatment. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2020;22, 49.

- Limaye V, Hakendorf P, Woodman RJ, Blumbergs P, Roberts-Thomson P. Mortality and its predominant causes in a large cohort of patients with biopsy-determined inflammatory myositis. Intern Med J. 2012, 42, 42–8. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães F, Yildirim R, Isenberg DA Long-term survival of patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: anatomy of a single-centre cohort Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2023;41(2):322-329.

- Mc Namara K, Alzubaidi H, Jackson JK. Cardiovascular disease as a leading cause of death: how are pharmacists getting involved? Integr Pharm Res Pract 2019, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Oreska S, Storkanova H, Pekacova A, Kudlicka J, Tuka V, Mikes O, Krupickova Z, Satny M, Chytilova E, Kvasnicka J, Spiritovic M, Hermankova B, Cesak P, Rybar M, Pavelka K, Senolt L, Mann H, Vencovsky J, Vrablik M, Tomcik M. Cardiovascular risk in myositis patients compared with the general population. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2024;63(3):715-724.

- Párraga Prieto C, Ibrahim F, Campbell R et al. Similar risk of cardiovascular events in idiopathic inflammatory myopathy and rheumatoid arthritis in the first 5 years after diagnosis. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40(1):231–8.

- Mizus MC, Tiniakou E. Lipid-lowering Therapies in Myositis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2020, 22, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosos GC, Vedder D, Houben E, Boekel L, Atzeni F, Badreh S, Boumpas DT, Brodin N, Bruce IN, González-Gay MÁ, Jacobsen S, Kerekes G, Marchiori F, Mukhtyar C, Ramos-Casals M, Sattar N, Schreiber K, Sciascia S, Svenungsson E, Szekanecz Z, Tausche AK, Tyndall A, van Halm V, Voskuyl A, Macfarlane GJ, Ward MM, Nurmohamed MT, Tektonidou MG. EULAR recommendations for cardiovascular risk management in rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(6):768-779.

- Shah M, Shrestha K, Tseng CW, Goyal A, Liewluck T, Gupta L. Statin-associated muscle symptoms: A comprehensive exploration of epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and clinical management strategies. Int J Rheum Dis. 2024;27(9):e15337.

- Pinal-Fernandez I, Casal-Dominguez M, Mammen AL. Statins: pros and cons. Med Clin (Barc). 2018;150(10):398–402.

- Lundberg IE, Tjärnlund A, Bottai M, Werth VP, Pilkington C, Visser M, et.al.; International Myositis Classification Criteria Project consortium, The Euromyositis register and The Juvenile Dermatomyositis Cohort Biomarker Study and Repository (JDRG) (UK and Ireland). 2017 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and their major subgroups. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(12):1955-1964.

- SCORE2 working group and ESC Cardiovascular risk collaboration , SCORE2 risk prediction algorithms: new models to estimate 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease in Europe, European Heart Journal, 2021;42:25, 2439–2454.

- https://www.escardio.org/Education/Practice-Tools/CVD-prevention-toolbox/HeartScore.

- Ihle-Hansen H, Vigen T, Berge T, Walle-Hansen MM, Hagberg G, Ihle-Hansen H,et al. Carotid Plaque Score for Stroke and Cardiovascular Risk Prediction in a Middle-Aged Cohort From the General Population. JAHA 2023, 12, e030739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobloug GC, Svensson J, Lundberg IE, Holmqvist M Mortality in idiopathic inflammatory myopathy: results from a Swedish nationwide population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:40–47.

- Dankó K, Ponyi A, Constantin T et al Long-term survival of patients with idiopathic infammatory myopathies according to clinical features: a longitudinal study of 162 cases. Medicine 2004;83:35–42.

- Jung K, Kim H, Park W et al Incidence, survival, and risk of cardiovascular events in adult infammatory myopathies in South Korea: a nationwide population-based study. Scand J Rheumatol 2020;49:323–331.

- Xiong A, Hu Z, Zhou S et al Cardiovascular events in adult polymyositis and dermatomyositis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2022;61:2728–2739.

- Ungprasert P, Suksaranjit P, Spanuchart I et al Risk of coronary artery disease in patients with idiopathic infammatory myopathies: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2014;44:63-67.

- Diederichsen LP, Diederichsen ACP, Simonsen JA et al Traditional cardiovascular risk factors and coronary artery calcifcation in adults with polymyositis and dermatomyositis: a danish multicenter study. Arthritis Care Res 2015;67:848–854.

- Linos E, Fiorentino D, Lingala B et al. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and dermatomyositis: an analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample survey. Arthritis Res Ther 2013, 15, R7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng M-Y, Lai EC-C, Yang Y-HK Increased risk of coronary heart disease among patients with idiopathic infammatory myositis: a nationwide population study in Taiwan. Rheumatology 2019;58:1935–1941.

- Leclair V, Svensson J, Lundberg IE, Holmqvist M Acute coronary syndrome in idiopathic infammatory myopathies: a population-based study. J Rheumatol 2019;46:1509–1514.

- Rai SK, Choi HK, Sayre EC, Aviña-Zubieta JA Risk of myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke in adults with polymyositis and dermatomyositis: a general population-based study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2016;55:461–469.

- Lin Y-N, Lin C-L, Chang K-C, Kao C-H Increased subsequent risk of acute coronary syndrome for patients with dermatomyositis/polymyositis: a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. Scand J Rheumatol 2015;44:42–47.

- Bae SS, Oganesian B, Golub I, Charles-Schoeman C. Statin use in patients with non-HMGCR idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: A retrospective study. Clin Cardiol. 2020, 43, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastegar TF, Khan IA, Christopher-Stine L. Decoding the Intricacies of Statin-Associated Muscle Symptoms. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2024;26(7):260-268.

- Blake GJ, Ridker PM. Are statins anti-inflammatory? Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med. 2000;1:161-165.

- Glavinovic T, Thanassoulis G, de Graaf J et al. Physiological Bases for the Superiority of Apolipoprotein B Over Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Non–High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol as a Marker of Cardiovascular Risk Journal of the American Heart Association 2022;11:20.

- Brinjikji W, Cloft H, Cekirge S. et al. Lack of Association between Statin Use and Angiographic and Clinical Outcomes after Pipeline Embolization for Intracranial Aneurysms AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2017;38:753–58.

- Reith, Christina et al. Effects of statin therapy on diagnoses of new-onset diabetes and worsening glycaemia in large-scale randomised blinded statin trials: an individual participant data meta-analysis The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 2024;12,5:306 - 319.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).