1. Introduction

Regenerative medicine, a specialized field of interventional and non-surgical medicine, often addresses issues not solvable by surgery or medications. There is a significant need for new treatment options for degenerative and traumatized tissues, as well as difficult-to-heal acute and chronic wounds. Tissue repair, regeneration, and wound healing constitute highly intricate and dynamic processes, influenced by a variety of pathological conditions, including chronic recalcitrant wounds, damaged tissue structures, and degenerative tissues.

These processes are dependent upon an array of local and systemic multicellular biological activities, which encompass critical cell signalling mechanisms [

1]. The application of autologous biological preparations, which can be prepared at the point of care, presents a significant promise for the promotion of tissue healing and repair in a natural manner [

2,

3]. These preparations leverage the body’s inherent healing capabilities, thereby enhancing the repair process in a targeted and efficient fashion. Blood-derived and mesenchymal stem cell and stromal based preparations are crucial in tissue repair and wound healing processes within complex biological microenvironments [

4].

Generally, HD-PRP and t-SVF biological preparations are increasingly used to support in chronic wound healing and tissue repair by delivering autologous biological cells [

5,

6].

This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the nuances of HD-PRP preparations as a stand-alone treatment, and we will address the synergy between HD-PRP and t-SVF when both biologics are combined as a therapeutical preparation.

2. Healing Cascades

Both the classical and angiogenesis healing pathways consist of distinct phases with an overlap of cellular activities, and they work in conjunction to ensure a coordinated and efficient healing and repair process, as shown in

Figure 1.

The traditional healing cascade consists of distinct phases, each characterized by specific cellular activities [

7]. Briefly, during the initial phase, hemostasis, platelets aggregate at tissue injury sites, stimulating blood clotting while forming a fibrinous network. Platelets then regulate the healing process by secreting their granular content and releasing many PGFs, cytokines, and molecules that initiate tissue repair [

8]. The angiogenesis cascade, though less studied, adds complexity to the wound healing process as it involves the recruitment, differentiation, and proliferation of endothelial cells [

9]. Ultimately forming new blood vessels are formed from preexisting ones, which is crucial for effective tissue repair, regeneration, and wound healing [

10]. In both healing cascades, the cellular and acellular components of HD-PRP, as well as the constituents of adipose tissue (t-SVF), play pivotal roles in restoring or regenerating tissues. The platelet and t-SVF cellular and acellular components stimulate tissue repair and regeneration by promoting cell proliferation, cell migration, immunomodulation, and angiogenesis. When combined, HD-PRP and t-SVF work synergistically to facilitate effective functional tissue restoration and regeneration.

3. HD-PRP Definition

PRP can be defined as a centrifugated and processed liquid fraction of harvested fresh peripheral blood with a platelet concentration above the baseline value [

11]. HD-PRP can be characterized as a heterogenous and complex composition of multicellular components, like platelet growth factors, chemokines, and other cytokines in a small volume of plasma, with a platelet concentration greater than 1 x 10

9/ml [

11,

12]. These natural proteins and cytokines are present in “normal” biological proportions and play important roles in cell proliferation, chemotaxis, cell differentiation, and angiogenesis [

1].

4. A Brief Overview of Platelets

Platelets are small, anucleate, discoid blood cells, typically measuring 1-3 micrometres, with an in vivo half-life of 7 days. In adults, the average platelet count ranges from 150 to 350.000 per microliter of circulating blood [

13]. Platelets are synthesized in the red bone marrow from megakaryocytes, which are their hematopoietic progenitor cells, by pinching off from these cells. Once synthesized, platelets are released into the peripheral circulation in a resting state and on a continuous basis [

14]. They play a crucial role in haemostasis by aggregating at the site of blood vessel injury to form a clot, preventing excessive bleeding. Additionally, platelets contain numerous growth factors, chemokines, cytokines, and other molecules that are essential for tissue repair and regeneration [

1]

The underlying scientific rationale for PRP therapy is that an injection of concentrated platelets at tissue sites may initiate repair through the release of numerous biologically active factors in the platelet storage granules, adhesion proteins, and transcription factors. These components are responsible for initiating restorative pathways. In any PRP formulation, platelets are the primary cells, and their activation leads to the secretion of these bioactive molecules [

15].

The release of HD-PRP concentrated platelet biological components can enhance tissue regeneration, promote cell proliferation, and accelerate the healing process by stimulating the body’s natural repair mechanisms.

5. PRP Variability and Its Consequences

Regrettably, significant variability in PRP platelet concentration and formulation among currently available PRP devices has resulted in inconsistent platelet dosing regimens and cellular characterization, leading to less beneficial patient outcomes [

16,

17,

18,

19]. The argument presented is that a “one-size-fits-all” approach to PRP orthobiological preparations and applications should be replaced by more nuanced and transformative approaches [

20]. These advances include the adoption of algorithms to determine cell dosing strategies specific to the pathoanatomic problem, as well as the use of physiologically different PRP bioformulations specific to the different tissues and pathologies being treated in the same patient procedure. This necessitates an unyielding awareness and understanding of the large variability in biocellular and orthobiological products currently on the market, regarding cell type, quality, and quantity, and application volumes needed to achieve appropriate dosing. The physiological variability of orthobiological preparations and specific bioformulations regarding their efficacy in immunomodulation, angiogenesis, pain downregulation, and tissue repair has been noted in clinical studies [

1]. Recently, we described recent advances in platelet-leukocyte interactions to provide a better understanding of PRP’s cellular behavior in various tissue types, like ligaments, menisci, and cartilage conditions, improving mechano-metabolic conditions, restoring musculoskeletal MSK function after injury and tissue degenerative and aging processes [

20]. It is only fair to assume that within the same functional unit (e.g., knee joint), different tissue structures and pathologies would respond differently to different biological treatments, because many interconnecting tissue structures are often involved in different pathologies. As a best practice, different PRP formulations should be used simultaneously in the same patient to treat tissue-specific and different pathoanatomic conditions. This approach aims to optimize the tissue structure-dependent healing response, ultimately leading to faster and better functional repair. For example, in patients with chronic wounds, different PRP formulations should be used based on the individual conditions of the wound bed and wound edges [

2].

5.1. PRP Classification

Various PRP bioformulations, terminologies, and product descriptions have been introduced to practitioners over the years [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. However, the lack of standardization and classification of PRP devices has led to the introduction of approximately 40, considerably, different PRP devices to the market, with inconsistent cell capture rates and varying platelet and non-platelet cellular constituents [

29].

Buffy-coat PRP devices and plasma-based PRP devices differ greatly. The more refined, often two-spin, buffy-coat PRP preparations have significantly more platelets available in the prepared PRP when compared to plasma-based PRP devices. Furthermore, buffy coat devices process in general higher whole blood volumes and they have the ability to capture leukocytic cells as well. These PRP devices are considered to be more flexible in the utilization of different PRP preparation protocols and can therefore be more effective in creating positive patient outcomes. Furthermore, PRP preparations can be categorized as pure PRP, leukocyte-poor PRP (LP-PRP), or leukocyte-rich PRP (LR-PRP) [

30].

In plasma-based PRP procedures, a “PRP-like” suspension is prepared, excluding erythrocytes and often leukocytes. Similarly, platelet rich fibrin (PRF) plasma-based preparations primarily consist of plasma [

31]. This plasma-based PRP product is a plasma protein matrix that can contain processed platelets and other cells with stimulatory and immunological properties. Many plasma-based devices do not use anticoagulants when harvesting blood, anticipating platelet activation and the release of clotting factors, including thrombin, to convert fibrinogen into a fibrin matrix. Fibrin polymerization, often induced by calcium chloride, results in a denser fibrin matrix compared to non-activated PRP. Following therapeutic application, fibrinolysis will liberate fibrin matrix components for a prolonged period, unlike activated PRP clots that lack excessive plasma fibrin and other proteins.

5.2. Variables in PRP Formulation

The quality and quantity of specific PRP products, determined by platelet dosages and leukocyte subpopulation bioformulations, are directly related to high cellular recovery rates from a unit of whole blood after gravitational density separation, as seen in two-spin PRP devices [

32]. Advanced PRP devices should be proficient in preparing different validated bioformulations to produce various platelet dosing and leukocyte populations and concentrations. It is, however, difficult to compare PRP outcome results accurately due to the wide variation in reported protocols for PRP preparation, including the total amount of whole blood donated, the type of anticoagulants used, device physical characteristics, the recovery rates of platelets and leukocytes, and centrifugal variances [

33,

34,

35]. These variable preparation characteristics, responsible for the heterogeneity of PRP preparations in MSK applications, have been discussed in more detail by Cherian et al. [

36]. The PRP centrifuge performance variables, such as the number of spin cycles, centrifugation speed and duration per spin cycle, and the acceleration and deceleration speed, are rarely mentioned. Thus, the characteristics of the ultimately extracted orthobiological products are scarcely understood. Piao et al. identified the critical factors to guarantee effective cellular yields in PRP orthobiologics as centrifuge acceleration profiles and spin time for the maximum recovery rate of platelets and leukocytes [

35]. Other substantial factors that determine the total number of available platelets for dosing include the total pre-donated anticoagulated blood volume prior to PRP processing, and the geometrical mathematics and physical properties of PRP devices used for cell concentration.

6. Defining the Biological Content of PRP and Platelets

On the outer surface of platelets, glycoprotein receptors and adhesion molecules are present, which play crucial roles in platelet activation and aggregation [

1]. Inside the platelet, there are three distinct structures: alpha-granules, dense granules, and lysosomes, demonstrated in

Figure 2. Additionally, and less known are platelet-derived exosomes, carrying many molecules that are transported to treated tissue sites [

37].

6.1. Platelet α-Granules

The α-granules of platelets are the most frequently cited intraplatelet structures due to their rich content of many platelet growth factors (PGFs), including, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (b-FGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), transforming growth factor-b (TGF-b) [

1,

38]. To a lesser extent, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), are secreted after platelet activation [

39]. Less frequently mentioned platelet α-granules include platelet coagulation factors, cytokines, chemokines, and pro and anti-angiogenetic regulators. These specific cytokines and chemokines serve various functions, including modulating inflammation, promoting cell migration and proliferation, and regulating angiogenesis, all of which are essential for tissue repair and regeneration.

Figure 2.

Electron microscopic image of intact non-activated human PRP platelets. The blue lines mark a single platelet in a PRP vial of PRP. The magnification of a single plate let displays the three platelet granular structures. Adapted and modified from [

40]. Abbreviations: α: alpha granules; DG: dense granules; L: lysosomes.

Figure 2.

Electron microscopic image of intact non-activated human PRP platelets. The blue lines mark a single platelet in a PRP vial of PRP. The magnification of a single plate let displays the three platelet granular structures. Adapted and modified from [

40]. Abbreviations: α: alpha granules; DG: dense granules; L: lysosomes.

6.2. Platelet Dense Granules

The dense granules of platelets contain serotonin, adenosine diphosphate (ADP), polyphosphates, histamine, and epinephrine [

20]. These substances primarily modulate platelet activation and thrombus formation. Importantly, many of these elements also have immune cell-modifying effects. For instance, platelet ADP is recognized by dendritic cells (DCs), leading to an increase in antigen endocytosis. DCs are crucial for initiating T-cell immune responses and governing the protective immune response, linking the innate and adaptive immune systems via inflammatory T helper cell (Th-2 cells) [

41]. Additionally, platelet serotonin induces T-cell migration and promotes the differentiation of monocytes into DCs. In PRP, these dense granule-derived immune modifiers are highly enriched and exert substantial immune regulatory effects. This highlights the significant role of platelets in not only hemostasis but also in modulating immune responses and contributing to the overall inflammatory and immune regulatory processes within the body.

6.3. Platelet Lysosomal Granules

Several human in vivo studies have demonstrated α and dense granule secretion following platelet activation. However, there is limited data on the in vivo release of lysosomal content, which contains an array of acid hydrolases. In general, lysosomal functions have not been extensively studied, although Heijnen and van der Sluis have highlighted their roles as contributors to the cell’s digestive system, destroying substances from outside the cell and to digest archaic cytosolic components [

42]. Furthermore, lysosomal activities are involved in extracellular functions such as fibrinolysis, supportive in vasculature remodeling, and the degradation of extracellular matrix components. Interestingly, lysosomes contain proteases and cationic proteins with bactericidal activity and are interconnected with macrophages in phagocytosis [

43]. This suggests that lysosomes may also participate in immune responses by aiding in the destruction of pathogens. Overall, the diverse functions of lysosomes underscore their importance in both intracellular and extracellular processes, contributing to cellular homeostasis and tissue remodeling.

6.4. Platelet Exosomes

Exosomes are nanosized extracellular vesicles (EVs) that originate from intracytoplasmic multivesicular bodies (MVBs) and are directly released into the extracellular space upon the fusion of the MVB membrane with the plasma membrane [

44]. Platelet-derived exosomes (PLT-EXOs) are stored in platelet α-granules, and they are released out of the platelets through extracellular secretion [

45]. EVs, and thus PLT-EXOs, facilitate intracellular communication between (long-distance) cells in the body [

46].

7. Identifying and Comprehending HD-PRP Characteristics

In two major device comparison studies, Fadadu and Magalon found that the platelet concentration was significantly lower in plasma-based PRP devices [

32,

47]. They utilize a low whole blood volume and single spin centrifugation methods when compared to larger whole blood volume and double spin centrifugation methods, to acquire a highly concentrated PRP product (HD-PRP), with significantly higher PGF concentrations. Everts et al. demonstrated that tissue repair, regeneration, and wound healing capacities are lower in plasma-based devices when compared to HD-PRP and buffy coat PRP systems [

38]. Notably, some plasma-based PRF devices have over 20 different sub-formulations and preparation protocols, varying the centrifugal force, speed, and processing time [

31].

7.1. Platelet Dose

Clinicians should consider adopting the concept of total deliverable platelets (TDP) as an improved PRP quality parameter, as it articulates the number of platelets accurately delivered to a single treatment site. Our group presented for the first time the rationale and feasibility to implement TDP dosing strategies, including biological formulations, to treat different pathoanatomic pathologies [

20]. This new quality treatment standard is supported by the translation of in-vitro data to clinical practice. Giusti et al. clearly demonstrated the need to deliver 1.5 billion platelets/mL to induce a significant angiogenic response [

48].

Further studies are warranted to determine the optimal TDP dosing for different soft tissue types and pathologies, including the chronicity of the disorder (acute vs. chronic). Similarly, Berger et al. indicated that higher platelet concentrations, prepared from platelet lysate preparations, resulted in more tenocyte proliferation and migration in a dose-dependent manner [

49]. More recently, Bansal and associates injected 10 billion platelets in patients diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis and observed a consistent clinical effect regarding pain, inflammatory markers, and function after a single injection over a 12-month period [

50].

7.2. Leukocytes in PRP

In the literature, PRP preparation protocols are generally underreported, most studies do not include detailed PRP preparation methods, with inconsistent laboratory data on platelet counts, platelet dose, and specific leukocyte population concentrations [

51]. This lack of reporting is surprising because PRP preparations contain varying leukocyte populations and concentrations, which can significantly impact pro-inflammation, immunomodulation, nociceptive effects, tissue repair, and regeneration.

Currently, the use of quality hemocytometry to document and track the effects of PRP preparations is becoming increasingly common in clinical settings.

Different PRP preparation devices produce varying leukocyte counts and populations, with dissimilar neutrophil, lymphocyte, and monocyte cell concentrations and ratios in the final PRP preparation [

52,

53]. Plasma test tube-based PRP devices produce very few leukocytes and significantly fewer platelets compared to more advanced PRP devices. Sophisticated PRP devices produce a buffy coat stratum where leukocytes are significantly concentrated, except for eosinophils and basophils, whose cell membranes are too fragile to withstand centrifugal processing forces.

Physicians should carefully consider the inclusion of leukocytes in HD-PRP bioformulations, as these cells influence the intrinsic biology in both acute and chronic tissue lesions due to their immune and host-defense mechanisms. The presence of specific leukocyte populations in HD-PRP preparations will likely lead to significant differences in cellular and tissue effects. Considerations regarding bioformulations should be based on the specific musculoskeletal pathology being treated, the cellular properties of tissue structures, and the chronicity of the tissue pathology.

7.2.1. Platelet-Leukocyte Interactions in HD-PRP

Leukocytes in PRP preparations can be included or avoided, with neutrophils raising concern due to their pro-inflammatory cytokine activities and the release of MMP’s, potentially escalating any early onset inflammatory response in injured hard and soft tissues [

53]. However, their role in resolving inflammation is also significant [

54]. Unfortunately, the PRP literature has primarily focused on the individual leukocytic cells and their functions, like neutrophils, rather than the combined platelet-leukocyte interactions including the presence of monocytes and lymphocytes. Activated HD-PRP platelets release lipid mediators that modulate inflammation [

55]. Activated platelets can convert arachidonic acid to antroberti-inflammatory lipoxins, preventing further neutrophil recruitment and promoting tissue healing [

56]. HD-PRP bioformulations with high platelet and monocyte yields mimic Th-2 cell activity, producing anti-inflammatory interleukin (IL) 4 [

57]. Additionally, HD-PRP platelets can polarize macrophage subtypes, thereby modulating immune cell interactions [

58], stimulating the complex cell-cell interactions in immunomodulatory mechanisms, like in osteoarthritis and tendinopathies [

59].

Recently, the application of HD-PRP containing a full leukocyte buffy coat in soft tissue pathologies have shown benefits, without significant adverse events [

60,

61].

7.3. Platelet-Derived EVs (PLT-EVs) and Exosomes (EXOs)

EVs are involved in various biological processes, including immune response, antigen presentation, cell migration, and tissue regeneration [

62]. They can transfer molecules from one cell to another, influencing the recipient cell’s behavior and function. EVs are membrane-bound vesicles with a lipid bilayer that are secreted by almost all types of cells. These vesicles play vital roles in the human body, serving as crucial mediators for intercellular communication [

44]. Based on size, biogenesis, and secretion mechanism, EVs are divided into three categories: EXOs, microvesicles, and apoptotic bodies [

63].

The most common type of EVs in circulation are PLT-EVs, released upon activation of platelets by various factors, with a size varying from 100 nm to 1 micrometer [

64]. PLT-EVs have capabilities comparable to platelets and are thought to impact various biological processes such as coagulation, wound healing, and inflammation. They can stimulate cellular differentiation, improving musculoskeletal or neurological regeneration [

65,

66]. Unlike platelets, PLT-EVs can pass across all natural tissue barriers, and deliver their cargo to remote tissue sites [

67,

68], extending their regenerative capabilities beyond the blood.

Exosomes are a type of EV and are formed within MVBs inside cells, where they bud off as intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) before being released into the extracellular space when the MVB fuses with the plasma membrane [

69]. Exosomes range in size from 50 to 150 nm. Furthermore, EXOs and PLT-EXOs have no obvious adverse effects such as immunogenicity or tumorigenicity [

70,

71].

7.3.1. Autologous PLT-EXOs

PLT-EVs, including PLT-EXOs, and MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-EXOs), have gained significant clinical and research interest to treat a variety of clinical pathologies, act as drug delivery vehicles, and they perform as diagnostic indicators [

64]. These vesicles are valued for their potential in therapeutic applications and as diagnostic tools due to their ability to transport bioactive molecules and facilitate intercellular communication [

72]. PLT-EVs are an integrated part of platelets, as visualized in

Figure 3. They can support coagulation, angiogenesis, regulate immunity, and accelerate tissue repair [

46].

Clinically, PLT-EXOs have been beneficial in treating chronic injuries and trauma, alleviating knee osteoarthritis, promoting wound healing. Torreggiani et al., isolated exosomes from PRP as novel effectors in human platelet activity and discussed the use of PLT-EXOs for bone tissue regeneration [

73]. Recent studies further emphasize the beneficial effects of PLT-EXOs from PRP in preventing osteonecrosis and promoting the re-epithelialization of chronic wounds [

74].

While PLT-EXOs technologies have significant potential, the US-FDA restricts the clinical application of allogeneic PLT-EXO. Currently, only very limited technologies are available for the manufacturing of autologous PLT-EXOs and their use in clinical settings. Briefly, autologous patient pure exosomes (PPX™) (Zeo Scientifix, Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, FL 33328, USA), is manufactured from a fresh unit of anticoagulated patient’s whole blood. Ultimately, a two-spin PRP preparation is subjected to an innovative proprietary production process to extract PLT-EVs and PLT-EXOs, generating a high acellular concentration of autologous PLT-EXOs (400 billion exosomes per vial). The entire procedure is performed in an US-FDA registered and cGMP compliant laboratory, in accordance with stringent safety and efficacy standards.

7.4. Immunomodulation

In both acute and chronic conditions, injured and degenerated tissues as well as foreign bodies, are rapidly identified. This recognition initiates inflammatory pathways and is related to the start of the wound healing cascade. The immune response involves both the innate and adaptive immune systems, with leukocytes playing essential roles in both and overlapping between the two systems [

1]. Monocytes, macrophages phenotype 1 and 2, neutrophils, dendritic cells, and natural killer cells have fundamental tasks in the innate system, nonspecifically identifying intruding microbes or tissue fragments and stimulating their clearance [

75]. Lymphocytes and their subsets have similar capacities in the adaptive immune system. Under homeostatic circumstances, platelets are among the first cells to identify endothelial tissue injury and detect the presence of microbial pathogens. Following HD-PRP injections, high concentrations of platelets accumulate and aggregate at treated tissue sites. Following platelet activation, an abundance of platelet agonists and biomolecules are released, enhancing further platelet activation while expressing platelet chemokine receptors. Under normal circumstances, this results in a rapid accumulation of peripheral platelets at the site of injury or infection. Subsequently, neutrophils, monocytes, and dendritic cells are recruited for an early-phase immune response [

76]. As HD-PRP therapies provide inflammatory stimuli, platelet receptors change their surface expression to stimulate platelet–leukocyte interactions by forming platelet–leukocyte aggregates to regulate inflammation and ultimately tissue repair. More precisely, neutrophils and monocytes are both active participants in these aggregate formations, thereby contributing to the innate immune response [

77]. This coordinated response ensures that the immune system can effectively identify and respond to injuries and infections, promoting healing and tissue repair.

7.5. Angiogenesis

Angiogenesis, the restoration of blood vasculature and the subsequent tissue perfusion, plays a crucial role in wound healing and tissue regeneration This process is particularly stimulated by high concentrations of VEGF, PDGF and b-FGF, which are abundantly present in HD-PRP [

38]. VEGF is the most important and widely studied angiogenic factor, produced in large amounts by platelets, keratinocytes, macrophages, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts during angiogenesis and classical wound healing.

Tissue damage, cell disruption, chronic inflammatory conditions, and hypoxia are strong inducers of angiogenic factors, including several types of VEGF and their typical receptors. Specifically, VEGF-A promotes the initial phase of angiogenesis and is important for wound healing. It binds to the dedicated VEGF-1 and VEGF-2 receptors, initiating blood vessel organization, chemotaxis, proliferation, and endothelial cell differentiation, respectively [

78]. These coordinated responses ensure that new blood vessels form efficiently, providing the necessary oxygen and nutrients to support the wound healing process and tissue regenerative pathways.

7.6. Nociception

In 2008, Everts et al. were the first to publish on the analgesic effects of an activated PRP formulation and they observed a significant reduction in pain and opioid use, as well as more successful post-surgical rehabilitation [

79]. Various clinical studies have demonstrated significant pain reduction or elimination after PRP treatments [

80,

81]. However, others reported little to no pain relief. TDP, platelet dosing, and PRP bioformulations have been identified as key features contributing to consistent painkilling effects [

38]. Additional variables affecting pain modulation that have been cited are the type of injury, treated tissue types, PRP application techniques, and the use of platelet activators [

82].

Kuffler studied the use of PRP to alleviate chronic neuropathic pain due to damaged non-regenerated nerves and demonstrated that neuropathic pain relieve was noted within three weeks and was eliminated or significantly reduced for more than six years [

83]. Similar painkilling effects were observed by Mohammadi et al. in post-surgical wound care patients, with a higher incidence of angiogenesis in patients treated with PRP [

84]. They concluded that reinstituting neo-angiogenesis was necessary to optimize tissue oxygenation and nutrient delivery.

The optimal PRP platelet dose and bioformulation for maximal pain relief are currently unknown. Published data suggests that PRP should contain at least 1.0 billion platelets per milliliter to provoke pain-killing effects, with higher platelet doses leading to better outcomes and higher patient satisfaction [

85]. The exact mechanisms behind this dose-dependent effect are still under investigation, highlighting the need to optimize PRP formulations for the best therapeutic results. Further research is needed to establish the precise platelet concentration and bioformulation for effective pain relief in different clinical scenarios.

8. Aspects of Adipose Tissue Biology

Currently, innovative strategies are being developed to repair soft tissue pathologies, select cartilage defects, to alleviate pain, improve wound healing, and ultimately functional tissue repair. In addition to a variety of adipose tissue preparations, such as t-SVF, which are frequently used for regenerative applications in plastic reconstructive and cosmetic surgical procedures, other biological preparations have also gained prominence. These include PRP, platelet lysate (PL), BMAC, autologous PLT-EXOs, and non-autologous Wharton’s jelly. These preparations have become increasingly popular in the fields of non-surgical sports medicine and orthopedics, as evidenced by numerous studies and clinical applications [

86,

87,

88].

8.1. Adipose t-SVF Hallmarks

Adipose tissue preparations have been successfully used in minimally invasive and non-surgical reconstructive procedures and in guided injections into damaged, degenerative, or non-healing wounds. The rationale for using t-SVF is that it is a heterogeneous ABP, highly vascularized and stable connective tissue due to cell-to-cell or cell-to-matrix connections, which are considered a prerequisite for such stem cells to open the cellular send and receive signaling [

89]. Adipose tissue, with its important bioactive scaffolding capabilities, should therefore be recognized as a multifaceted microvascular organ in the form of lipoaspirates, consisting of various cellular tissue and stromal elements, including AD-MSCs [

90]. Furthermore, concentrated and compressed t-SVF provides a physiological multicellular scaffold containing AD-MSCs along with other stromal vascular cells. Minimally invasive access techniques are employed to harvest from several subcutaneous fat deposits, including the abdomen, perigluteal, thigh, and flank areas [

91]. During the procedure, a subcutaneous injection of a dilute local anesthetic solution (tumescent) is administered to numb the area of adipose harvesting and facilitate the creation of a t-SVF suspension [

92]. After a brief waiting period, a blunt-tipped atraumatic and coated microcannula is introduced through a small puncture using extensive pre-tunneling passages in the skin and attached to a closed syringe for manually controlled, low negative pressure, lipoaspiration. A correctly performed lipoaspiration procedure preserves the neurovascular structures at the donor site with a minimal level of discomfort for the patient. Furthermore, the cell yield and viability of AD- MSCs are rarely impacted by liposuction techniques [

93].

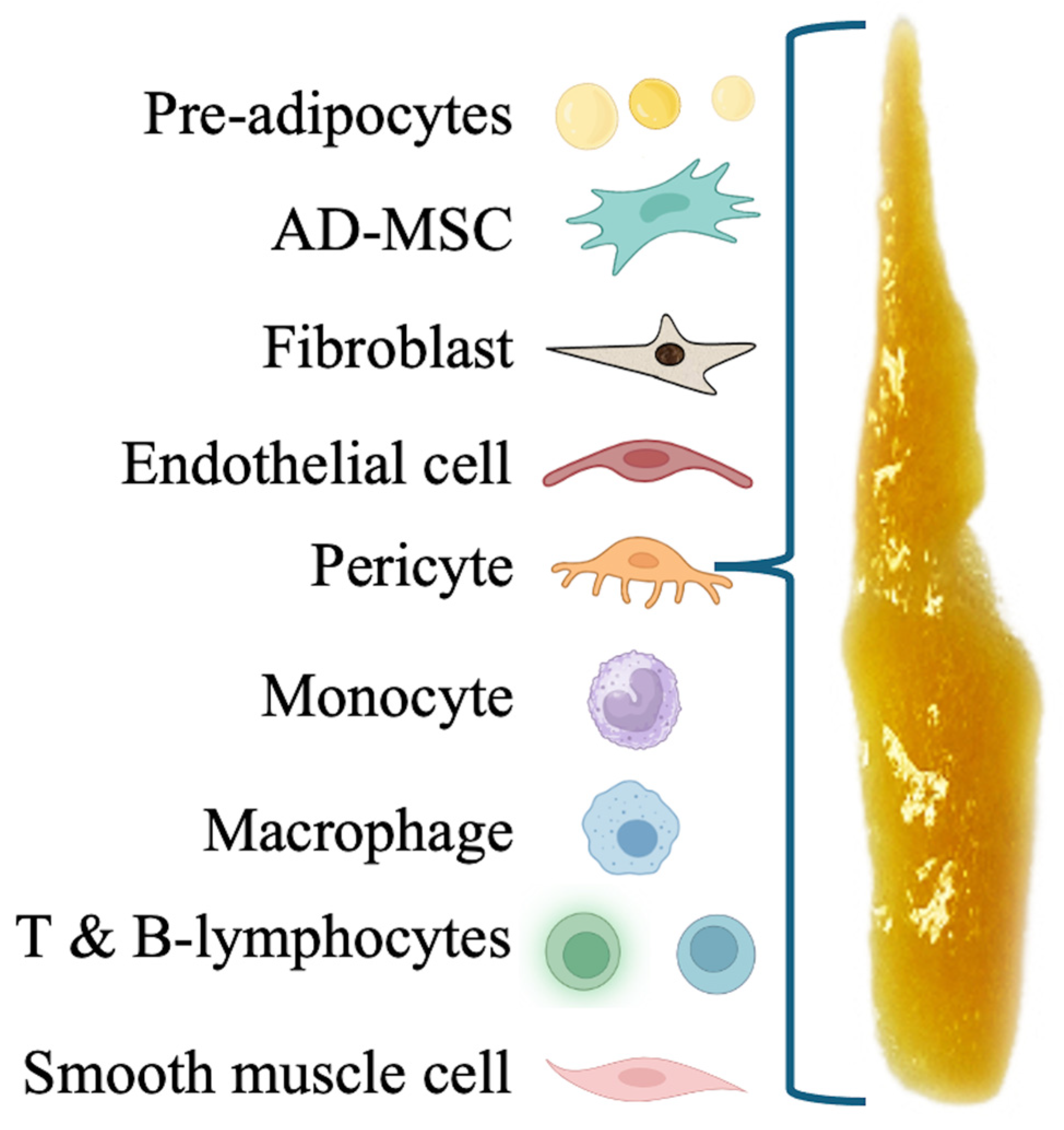

Following lipoaspirate centrifugation, t-SVF-based preparations can be accessed, consisting of cellular and matrix components derived from adipose tissue. These preparations are used in advanced regenerative medicine procedures. SVF is a complex mixture of various cell types, including endothelial cells, immune cells, fibroblasts, macrophages, pericytes, and a significant population of AD-MSCs [

94], as depicted in

Figure 4. Embedded in and attached to collagen fibers and other components of the extracellular matrix, these cells contribute to the regenerative properties of the SVF [

5].

Prior to regenerative applications, various SVF preparation protocols are available to prepare either fully emulsified nanofat in small aggregates (t-SVF) or cellular SVF (c-SVF), a preparation method based on enzymatic digestion techniques using collagenase [

5,

95]. t-SVF preparations are created by mechanical emulsification, reducing the size of macrofat to either partially or fully emulsified aggregates, known as partially emulsified fat or nanofat,

Figure 5.

Importantly, the fully emulsified, sized t-SVF aggregates present an intact microenvironment, whereby the fully emulsified small nanofat aggregates are essentially devoid of adult adipocytes. Generally, nanofat t-SVF preparations are considered the most potent and valuable form of t-SVF for regenerative and wound healing purposes [

95].

Freshly prepared t-SVF can be directly administered to the patient without the need for cell expansion techniques or additional cell separation preparations. Unlike cultured MSCs, emulsified t-SVF is not a 100% acellular product, as it contains both cellular fragments and important native adipose structural) components. An advantage of t-SVF compared to cultured acellular MSCs is that it offers the ability to provide a bioactive cellular tissue scaffold [

90].

8.2. t-SVF Components

The application of t-SVF in wound healing, tissue repair, and regenerative therapies is predicated on its rich content of regenerative cells and factors. SVF cells possess the capacity for differentiation into various cell types, engage in cell-to-cell communication through paracrine signaling, and may contribute to secrete ECM components [

96]. These attributes provide crucial elements in response to damaged or degenerative cells. The presence of typical heterogeneous SVF-based cells can be assessed using enzymatic methods and quantified with advanced laboratory flow cytometry techniques, ensuring the quality and potential effectiveness of both t-SVF and c-SVF in therapeutic applications. AD-MSCs are the most prominent stem cells in t-SVF with the potential to differentiate into various cell types, including osteoblasts, adipocytes, chondrocytes, tenocytes, and myocytes. MSCs, with high self-renewal, proliferative, and differentiation potential, can be derived from various sources, including skeletal muscle, synovium, and periosteum [

97].

8.2.1. AD-MSCs

Adult MSCs are undifferentiated and multipotent cells that are found in virtually every organ of the body and are capable of self-renewal [

2]. The most common sources of ubiquitous MSCs are subdermal adipose tissue and bone marrow [

98]. In bone marrow, MSCs represent a small fraction, ranging from 0.001% to 0.01% of nonhematopoietic, multipotent MSCs [

99]. MSCs have the ability to differentiate into various cells of mesodermal origin, including adipocytes, chondrocytes, myocytes, and osteoblasts, when exposed to specific signaling pathways [

100]. In vitro, these same cells have been shown to develop into neuroectodermal lines, thereby, acting in a pluripotential activity [

101]. In addition to their potential to promote immune modulation, angiogenic activity, anti-inflammatory activity, and anti-apoptotic activity, they also release numerous cytokines and growth factors that confer immunomodulatory, anti-apoptotic, and anti-inflammatory effects on many heterogeneous populations of cells [

8].

AD-MSCs and BM-MSCs share many the same biological characteristics and transcriptome profiles [

102]. Although some differences in their immunophenotype, differentiation potential, proteome, and immunomodulatory activities have been reported.

Adipose tissue, on the other hand, has been reported to contain larger quantities of mesenchymal and progenitor cells. Due to this higher concentration of reparative and regenerative cells, adipose-derived cell therapies have become increasingly popular as a treatment option, surpassing the effectiveness of BMAC and peripheral blood derived preparations [

103]. Besides, AD-MSCs are preferred over bone marrow-derived counterparts due to their superior accessibility, higher proliferative and repair capacities, and lower donor site morbidity [

104]. AD-MSCs exert paracrine, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory effects depending on environmental conditions [

105,

106]. Their therapeutic effects are likely mediated by paracrine signaling and the release of growth factors and cytokines that influence the intraarticular environment [

107]. Furthermore, AD-MSCs are known to polarize M0 macrophages and dendritic cells to an anti-inflammatory phenotype [

108]. AD-MSC preparations have shown excellent safety profiles and promising clinical efficacy in treating soft tissue and musculoskeletal disorders, like knee and shoulder pathologies [

109].

8.2.2. Pericyte Stem Cells (PSCs)

Many researchers and clinicians believe that pericyte stem cells (PSCs) are ubiquitous cells, representing the original “stem” cell originator, and are fully capable of all the functions of MSCs [

110]. PSCs are located on the walls of capillaries, in perivascular and paravascular locations, and work intimately with endothelial and intra-adventitial cells [

111]. PSCs also possess pluripotent capabilities, including the ability to stabilize blood vessels as well as differentiate into other types of cells, including smooth muscle cells, adipocytes, osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and even neural lineages, contributing significantly to tissue regeneration, repair, and wound healing [

112].

8.2.3. Endothelial Cells

Endothelial cells, which line blood vessels, play key roles in forming new blood vessels through angiogenesis [

113]. t-SVF aids in the promotion of angiogenesis as endothelial cells and growth factors promote the formation of new blood vessels, enhancing oxygen and nutrient supply to the wound or damaged tissue, thereby supporting tissue healing [

114].

8.2.4. Fibroblasts

Fibroblasts in t-SVF contribute to the synthesis of collagen and other extracellular matrix components, which are essential for the structural integrity and function of repaired tissues [

115]. This comprehensive approach ensures that t-SVF can effectively support the healing and regeneration processes in various types of tissue damage. Fibroblasts hold crucial roles in wound closure and the strength of healed tissues [

116].

8.2.5. Immune Cells

Various immune cells, originating from hematopoietic cell lineages (e.g., monocytes, lymphocytes, and various macrophage phenotypes), are involved in modulating the immune response. Immune cells and anti-inflammatory cytokines are present in t-SVF, playing a crucial role in modulating the body’s immune response [

117]. The primary immune cells associated with anti-inflammatory activities are M2 macrophages and regulatory T cells (Tregs) [

118]. These cells secrete the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 reducing chronic inflammation. Additionally, T- helper cells, Th cell, more specifically Th2 cells produce TGF-β and IL-4, further supporting the anti-inflammatory environment [

119]. Together, these cells and cytokines modulate the body’s immune response, reducing inflammation and promoting a more conducive environment for tissue repair and tissue regeneration [

120,

121].

9. The Regenerative Marriage Between HD-PRP and Adipose Tissue

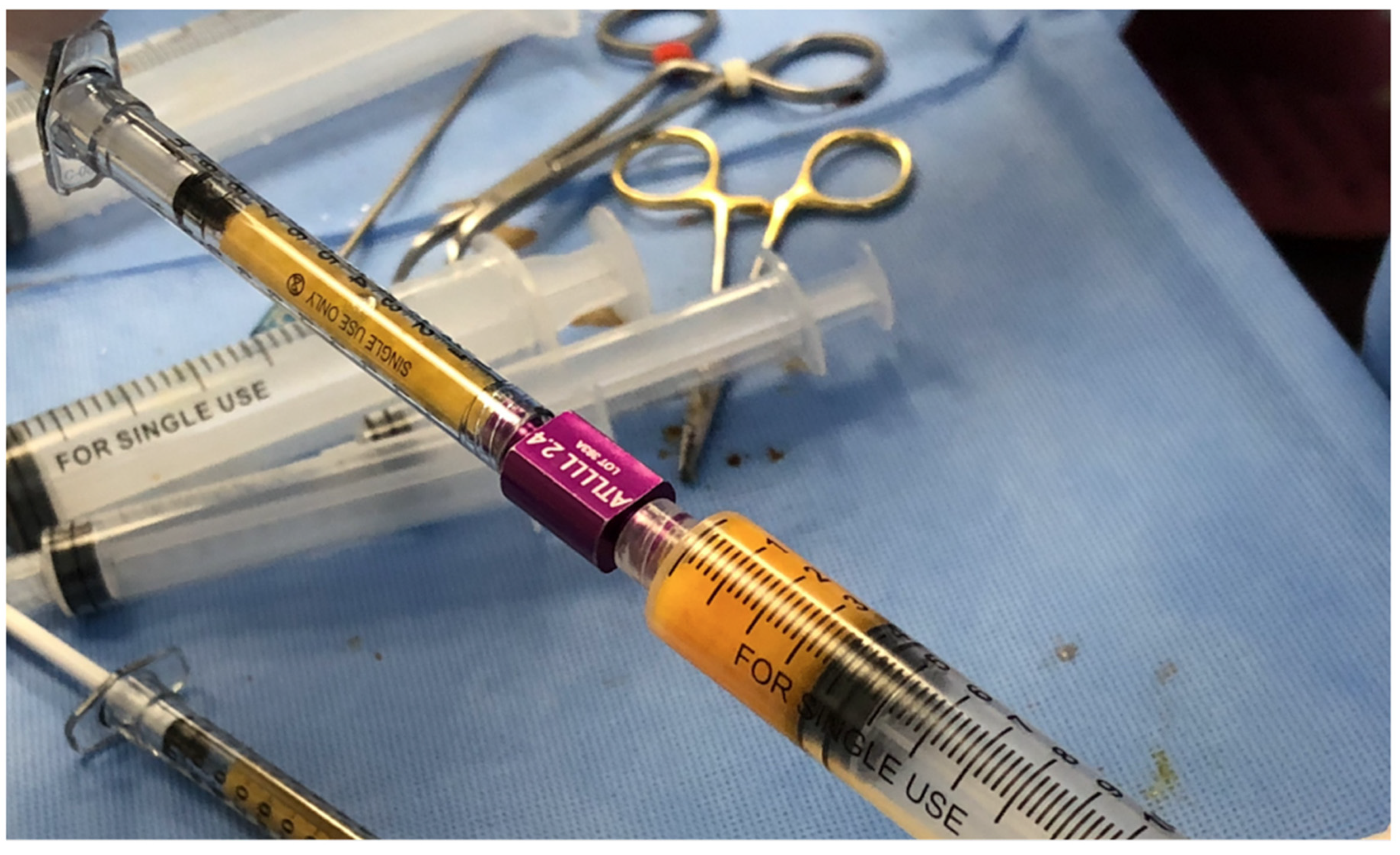

The efficacy of PRP and t-SVF as biological treatment options has been extensively studied. The combination of PRP and t-SVF (

Figure 6) has been utilized as an autologous innovative biological multi-cellular treatment platform, mostly employed in esthetic and plastic reconstructive surgeries, as well as for treating non-healing chronic wounds. The synergistic effects of PRP and t-SVF enhance tissue regeneration and repair, offering a comprehensive and effective solution for various medical and cosmetic needs.

Figure 6.

Mixing a high-volume HD-PRP (leukocyte rich preparation) with a high-volume of partially emulsified adipose tissue for a plastic reconstructive procedure.

Figure 6.

Mixing a high-volume HD-PRP (leukocyte rich preparation) with a high-volume of partially emulsified adipose tissue for a plastic reconstructive procedure.

Figure 7.

HD-PRP mixed with t-SVF serving as a biocellular graft. In A, the combined biocellular graft is injected in the wound edges of a chronic venous lower extremity ulcer. In B, the HD-PRP and t-SVF mixture is injected in the scalp to stimulate hair growth of a patient suffering from alopecia errata and injected in the scalp.

Figure 7.

HD-PRP mixed with t-SVF serving as a biocellular graft. In A, the combined biocellular graft is injected in the wound edges of a chronic venous lower extremity ulcer. In B, the HD-PRP and t-SVF mixture is injected in the scalp to stimulate hair growth of a patient suffering from alopecia errata and injected in the scalp.

9.1. Rationale for Compounding HD-PRP with t-SVF

Tissue repair, regeneration, and wound healing are complex biological processes aimed at restoring the integrity and function of damaged or degenerated tissues. These restorative processes follow well-defined cascades of events, involving numerous systemic and local cellular activities occurring sequentially.

HD-PRP and t-SVF biological technologies are designed to mimic the initiation of classical and angiogenesis healing cascades in various medical indications, including cosmetic and plastic reconstructive surgical and non-surgical procedures [

122]. Among other features, compounding HD-PRP and t-SVF is considered to potentially enhance fat graft survival, potentially avoiding fat necrosis, and reduce inflammation by promoting improved vascularization and providing anti-inflammatory signals at the graft site, thereby improving the overall healing process and stimulating the recipient tissue site [

123,

124]. Noteworthy, Yoshimura et al. have clearly shown a limited adipocyte survival in transplanted fat grafting treatments [

125]. They presented the concept of the “cell survival theory, in which transplanted adipocytes partly survive in response to microenvironmental changes, such as tissue ischemia and applied mechanical forces, leading to ischemic adipocyte cell death [

126,

127]. This resulted in nanofat small aggregate utilization in aesthetics and orthobiological applications, because nanofat leads to better adipocyte survival when compared to traditional fat grafting techniques due to a high concentration of AD-MSCs and other SVF constituents [

128].

9.2. Synergistic Effects

Combining PRP and t-SVF as demonstrated notable efficiencies in the metabolism of AD-MSCs. Additionally, it has promoted parenchymal cell proliferation and facilitated immunomodulation, impacting both the transplanted component and the damaged or aging recipient sites through various biological pathways [

129,

130].

The synergy PRP and AD-MSCs has been demonstrated to significantly stimulate tissue vascularization in wounds compared to PRP or AD-MSCs alone [

129]. It is believed that PRP enhances the angiogenic potential of AD-MSCs by activating the MSC secretome, resulting in increased synthesis of VEGF and stromal cell-derived factor 1, which consequently improves blood vessel formation and endothelial cell migration [

131].

9.2.1. HD-PRP and t-SVF Matrix Formation

Additional synergistic effects between t-SVF and a PRP-induced fibrin matrix have been observed regarding the secretion of high VEGF concentrations when both biologics are combined [

132].

This matrix serves as a cellular scaffold, retaining concentrated platelet elements, leukocytes, t-SVF cells, cytokines, and other proteins for an extended period, functioning as a sustained, extended-release matrix [

4,

133]. Furthermore, this scaffold inhibits the apoptosis of adipocytes. Interestingly, the combination of PRP and AD-MSCs revealed an increase in mitochondrial respiration and oxygen consumption, resulting in elevated adenosine triphosphate production [

122].

9.2.2. Optimizing Cell Migration

Cell migration is a fundamental, and underestimated, process in all multicellular organisms, playing a critical role not only during development but also throughout an organism’s life [

134]. This process is particularly important during wound healing, where cells must move to the site of injury to facilitate repair and wound closure, as well as the restoration of normal tissue architecture [

135]. Cell migration is directed by cell signaling or extracellular cues like soluble factors, cell bound ligands or ECM components, eliciting a wide range of intracellular responses [

136]. These cues can affect EV transportation pathways, over long distances, which are essential for transporting cargo within cells and steer to the correct location. Correspondingly, cues receive signals from neighboring cells, and the extracellular matrix, vital for maintaining cellular function. Hence, cues influence gene transcription and protein production to further support the integrity of cell migration and further propagate migratory signals within the cell [

137].

10. Conclusions

HD-PRP and t-SVF, are powerful high yielded cellular biological products which can be safely prepared at point-of-care, either separately or as a combined biological product to repair and regenerate tissues, aiming for functional restoration. HD-PRP exhibits unique cellular and acellular components, making it a complex biological preparation, containing many platelet-derived growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, PLT-EXOs, proteins, and bioformulation dependent, different leukocytes. t-SVF, a heterogenous mixture of cells obtained from adipose tissue, include AD-MSCs and its progenitor cells, endothelial cells, pericytes and a variety of immune cells. Both autologous preparations can be employed in non-surgical and bio-surgical procedures, including wound healing treatments to improve patient outcomes and decrease complications.

Combining HD-PRP with t-SVF is considered beneficial because it creates multiple synergistic effects which are capable of enhancing angiogenesis, increase cell proliferation, can modulate the immune response, and provides a supportive extracellular matrix.

This comprehensive combined multicellular approach is a promising strategy for enhancing tissue healing and regeneration. This biological preparation can create an optimal environment for tissue repair and regeneration, leading to improved clinical outcomes in patients suffering from recalcitrant and chronic wounds, provide support in skin rejuvenation and soft tissue repair procedures (scar treatments), various MSK disorders, like osteoarthritis and tendinopathies.

Lastly, more clinical and translational studies are required to further elucidate the biological potentials and further demonstrate efficacy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.A.E., and R.W.A.; investigation, P.A.E., R.W.A., J.F.L., L.P., and R.F.D.; writing—original draft preparation, P.A.E, and R.W.A.; writing—review and editing, L.P., J.F.L., R.F.D., G.S., A.v.Z.; visualization, P.A.E.; supervision, R.W.A., L.P., A.v.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Peter A. Everts is CSTO and George Shapiro is CMO of Zeo Scientifix.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABP |

autologous biological preparation |

| AD-MSCs |

adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells |

| ADP |

adenosine diphosphate |

| b-FGF |

basic fibroblast growth factor |

| BMAC |

bone marrow aspirate concentrates |

| CTGF |

connective tissue growth facto |

| DC |

dendritic cells |

| ECM |

extracellular matrix |

| EGF |

epidermal growth factor |

| EV |

extracellular vesicle |

| HD-PRP |

high-density platelet-rich plasma |

| HGF |

hepatocyte growth factor |

| IGF-1 |

insulin-like growth factor-1 |

| IL |

interleukin |

| ILV |

intraluminal vesicle |

| LP-PRP |

leukocyte-poor PRP |

| LR-PRP |

leukocyte-rich PRP |

| MSC |

mesenchymal stem cell |

| MSK |

musculoskeletal |

| MVB |

multivesicular bodies |

| PDGF |

platelet-derived growth factor |

| PGF |

platelet growth factor |

| PLT-EXO |

platelet-derived exosomes |

| PPX |

patient pure exosomes |

| PRF |

platelet rich fibrin |

| PRP |

platelet-rich plasma |

| PSC |

pericyte stem cell |

| SVF |

stromal vascular fractions |

| t-SVF |

tissue stromal vascular fraction |

| TDP |

deliverable platelets |

| TGF-b |

transforming growth factor-b |

| Th-cell |

T helper cell |

| Treg |

regulatory T cell |

| VEGF |

vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- Everts P, Onishi K, Jayaram P, Lana JF, Mautner and K. Platelet-Rich Plasma: New Performance Understandings and Therapeutic Considerations in 2020 [Internet]. MEDICINE & PHARMACOLOGY; 2020 Oct [cited 2020 Oct 21]. Available online: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202010.0069/v1.

- A. Everts P. Autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma and Mesenchymal Stem Cells for the Treatment of Chronic Wounds. In: Hakan Dogan K, editor. Wound Healing - Current Perspectives [Internet]. IntechOpen; 2019 [cited 2020 Sep 10]. Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/books/wound-healing-current-perspectives/autologous-platelet-rich-plasma-and-mesenchymal-stem-cells-for-the-treatment-of-chronic-wounds.

- Calvi LM, Link DC. The hematopoietic stem cell niche in homeostasis and disease. Blood. 2015 Nov 26;126[22]:2443–51.

- Lana JF, Purita J, Everts PA, De Mendonça Neto PAT, De Moraes Ferreira Jorge D, Mosaner T, et al. Platelet-Rich Plasma Power-Mix Gel (ppm)—An Orthobiologic Optimization Protocol Rich in Growth Factors and Fibrin. Gels. 2023 Jul 7;9[7]:553.

- Alexander RW. Adipose Tissue Complex (ATC): Cellular and Biocellular Uses of Stem/Stromal Cells and Matrix in Cosmetic Plastic, Reconstructive Surgery and Regenerative Medicine. In: Duscher D, Shiffman MA, editors. Regenerative Medicine and Plastic Surgery [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019 [cited 2024 Mar 24]. p. 45–69. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-19962-3_5.

- Everts P, M. Hoogbergen M, A.Weber T, J.J. Devilee R, van Monftort G, H.J.T. de Hingh I. Is the Use of Autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma Gels in Gynecologic, Cardiac, and General, Reconstructive Surgery Beneficial? Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012 May 1;13[7]:1163–72.

- Gentile P, Garcovich S. Systematic Review—The Potential Implications of Different Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) Concentrations in Regenerative Medicine for Tissue Repair. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Aug 9;21[16]:5702.

- Everts PA, Sadeghi P, Smith DR. Basic Science of Autologous Orthobiologics. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2023 Feb;34[1]:1–23.

- Honnegowda TM, Kumar P, Udupa EGP, Kumar S, Kumar U, Rao P. Role of angiogenesis and angiogenic factors in acute and chronic wound healing. 2015;2(5):7.

- Tonnesen MG, Feng X, Clark RAF. Angiogenesis in Wound Healing.

- Marx, RE. Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP): What Is PRP and What Is Not PRP?: Implant Dent. 2001 Dec;10(4):225–8.

- Tate-Oliver K, Alexander RW. Combination of Autologous Adipose-Derived Tissue Stromal Vascular Fraction Plus High Density Platelet-Rich Plasma or Bone Marrow Concentrates in Achilles Tendon Tears.

- Pokrovskaya ID, Yadav S, Rao A, McBride E, Kamykowski JA, Zhang G, et al. 3D ultrastructural analysis of α-granule, dense granule, mitochondria, and canalicular system arrangement in resting human platelets. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020 Jan;4(1):72–85.

- Day RB, Link DC. Megakaryocytes in the hematopoietic stem cell niche. Nat Med. 2014 Nov;20(11):1233–4.

- Roh YH, Kim W, Park KU, Oh JH. Cytokine-release kinetics of platelet-rich plasma according to various activation protocols. Bone Jt Res. 2016 Feb;5(2):37–45.

- Hurley ET, Fat DL, Moran CJ, Mullett H. The Efficacy of Platelet-Rich Plasma and Platelet-Rich Fibrin in Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am J Sports Med. :8.

- Bennell KL, Paterson KL, Metcalf BR, Duong V, Eyles J, Kasza J, et al. Effect of Intra-articular Platelet-Rich Plasma vs Placebo Injection on Pain and Medial Tibial Cartilage Volume in Patients With Knee Osteoarthritis: The RESTORE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021 Nov 23;326(20):2021.

- Rodeo SA, Delos D, Williams RJ, Adler RS, Pearle A, Warren RF. The Effect of Platelet-Rich Fibrin Matrix on Rotator Cuff Tendon Healing: A Prospective, Randomized Clinical Study. Am J Sports Med. 2012 Jun;40(6):1234–41.

- Korpershoek JV, Vonk LA, De Windt TS, Admiraal J, Kester EC, Van Egmond N, et al. Intra-articular injection with Autologous Conditioned Plasma does not lead to a clinically relevant improvement of knee osteoarthritis: a prospective case series of 140 patients with 1-year follow-up. Acta Orthop. 2020 Nov 1;91(6):743–9.

- Everts PA, Mazzola T, Mautner K, Randelli PS, Podesta L. Modifying Orthobiological PRP Therapies Are Imperative for the Advancement of Treatment Outcomes in Musculoskeletal Pathologies. Biomedicines. 2022 Nov 15;10(11):2933.

- Ehrenfest DMD, Andia I, Zumstein MA, Zhang CQ, Pinto NR, Bielecki T. Classification of platelet concentrates (Platelet-Rich Plasma-PRP, Platelet-Rich Fibrin-PRF) for topical and infiltrative use in orthopedic and sports medicine: current consensus, clinical implications and perspectives. :7.

- DeLong JM, Russell RP, Mazzocca AD. Platelet-Rich Plasma: The PAW Classification System. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2012 Jul;28(7):998–1009.

- Mishra A, Harmon K, Woodall J, Vieira A. Sports Medicine Applications of Platelet Rich Plasma. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012 May 1;13(7):1185–95.

- Mautner K, Malanga GA, Smith J, Shiple B, Ibrahim V, Sampson S, et al. A Call for a Standard Classification System for Future Biologic Research: The Rationale for New PRP Nomenclature. PM&R. 2015 Apr;7:S53–9.

- Magalon J, Chateau AL, Bertrand B, Louis ML, Silvestre A, Giraudo L, et al. DEPA classification: a proposal for standardising PRP use and a retrospective application of available devices. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2016 Feb;2(1):e000060.

- Lana JFSD, Purita J, Paulus C, Huber SC, Rodrigues BL, Rodrigues AA, et al. Contributions for classification of platelet rich plasma – proposal of a new classification: MARSPILL. Regen Med. 2017 Jul;12(5):565–74.

- Kon E, Di Matteo B, Delgado D, Cole BJ, Dorotei A, Dragoo JL, et al. Platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: an expert opinion and proposal for a novel classification and coding system. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2020 Dec 1;20(12):1447–60.

- Everts PAM, van Zundert A, Schönberger JPAM, Devilee RJJ, Knape JTA. What do we use: Platelet-rich plasma or platelet-leukocyte gel? J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008 Jun 15;85A(4):1135–6.

- Chahla J, Cinque ME, Piuzzi NS, Mannava S, Geeslin AG, Murray IR, et al. A Call for Standardization in Platelet-Rich Plasma Preparation Protocols and Composition Reporting: A Systematic Review of the Clinical Orthopaedic Literature. J Bone Jt Surg. 2017 Oct 18;99(20):1769–79.

- Everts PA, Flanagan G, Podesta L. Autologous Orthobiologics. In: Mostoufi SA, George TK, Tria AJ, editors. Clinical Guide to Musculoskeletal Medicine [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2022 [cited 2022 Sep 22]. p. 651–79. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-92042-5_62.

- Miron RJ, Chai J, Fujioka-Kobayashi M, Sculean A, Zhang Y. Evaluation of 24 protocols for the production of platelet-rich fibrin. BMC Oral Health. 2020 Dec;20(1):310.

- Magalon J, Brandin T, Francois P, Degioanni C, De Maria L, Grimaud F, et al. Technical and biological review of authorized medical devices for platelets-rich plasma preparation in the field of regenerative medicine. Platelets. 2021 Feb 17;32(2):200–8.

- Marathe A, Patel SJ, Song B, Sliepka JM, Shybut TS, Lee BH, et al. Double-Spin Leukocyte-Rich Platelet-Rich Plasma Is Predominantly Lymphocyte Rich With Notable Concentrations of Other White Blood Cell Subtypes. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2022 Apr;4(2):e335–41.

- Fitzpatrick J, Bulsara MK, McCrory PR, Richardson MD, Zheng MH. Analysis of Platelet-Rich Plasma Extraction: Variations in Platelet and Blood Components Between 4 Common Commercial Kits. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017 Jan;5(1):232596711667527.

- Piao L, Park H, Jo CH. Theoretical prediction and validation of cell recovery rates in preparing platelet-rich plasma through a centrifugation. Wang JHC, editor. PLOS ONE. 2017 Nov 2;12(11):e0187509.

- Cherian C, Malanga G, Mautner K. OPTIMIZING PLATELET-RICH PLASMA (PRP) INJECTIONS: A NARRATIVPEroceedings. 2:17.

- Guo SC, Tao SC, Yin WJ, Qi X, Yuan T, Zhang CQ. Exosomes derived from platelet-rich plasma promote the re-epithelization of chronic cutaneous wounds via activation of YAP in a diabetic rat model. Theranostics. 2017;7(1):81–96.

- Everts PA, Lana JF, Onishi K, Buford D, Peng J, Mahmood A, et al. Angiogenesis and Tissue Repair Depend on Platelet Dosing and Bioformulation Strategies Following Orthobiological Platelet-Rich Plasma Procedures: A Narrative Review. 2023.

- Hayashi S, Aso H, Watanabe K, Nara H, Rose MT, Ohwada S, et al. Sequence of IGF-I, IGF-II, and HGF expression in regenerating skeletal muscle. Histochem Cell Biol. 2000;122:427–34.

- Everts PA, Jakimowicz JJ, van Beek M, Schönberger JPAM, Devilee RJJ, Overdevest EP, et al. Reviewing the Structural Features of Autologous Platelet-Leukocyte Gel and Suggestions for Use in Surgery. Eur Surg Res. 2007;39(4):199–207.

- Kaiko GE, Horvat JC, Beagley KW, Hansbro PM. Immunological decision-making: how does the immune system decide to mount a helper T-cell response? Immunology. 2008 Mar;123(3):326–38.

- Heijnen H, van der Sluijs P. Platelet secretory behaviour: as diverse as the granules … or not? J Thromb Haemost. 2015 Dec;13(12):2141–51.

- Gray MA, Choy CH, Dayam RM, Ospina-Escobar E, Somerville A, Xiao X, et al. Phagocytosis Enhances Lysosomal and Bactericidal Properties by Activating the Transcription Factor TFEB. Curr Biol. 2016 Aug;26(15):1955–64.

- Kalra H, Drummen G, Mathivanan S. Focus on Extracellular Vesicles: Introducing the Next Small Big Thing. Int J Mol Sci. 2016 Feb 6;17(2):170.

- Rui S, Yuan Y, Du C, Song P, Chen Y, Wang H, et al. Comparison and Investigation of Exosomes Derived from Platelet-Rich Plasma Activated by Different Agonists. Cell Transplant. 2021 Jan 1;30:096368972110178.

- Spakova T, Janockova J, Rosocha J. Characterization and Therapeutic Use of Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Platelets. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Sep 8;22(18):9701.

- Fadadu PP, Mazzola AJ, Hunter CW, Davis TT. Review of concentration yields in commercially available platelet-rich plasma (PRP) systems: a call for PRP standardization. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2019 Jun;44(6):652–9.

- Giusti I, D’Ascenzo S, Mancò A, Di Stefano G, Di Francesco M, Rughetti A, et al. Platelet Concentration in Platelet-Rich Plasma Affects Tenocyte Behavior In Vitro. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014:1–12.

- Berger DR, Centeno CJ, Steinmetz NJ. Platelet lysates from aged donors promote human tenocyte proliferation and migration in a concentration-dependent manner. Bone Jt Res. 2019 Jan;8(1):32–40.

- Bansal H, Leon J, Pont JL, Wilson DA, St SM, Bansal A, et al. Clinical Efficacy of a Single-dose of Platelet Rich Plasma in the Management of Early Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Controlled Study With Mri Assessment and Evaluation of Optimal Dose [Internet]. In Review; 2020 Jun [cited 2020 Jul 7]. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-33058/v1.

- Melo, Luzo, Lana, Santana. Centrifugation Conditions in the L-PRP Preparation Affect Soluble Factors Release and Mesenchymal Stem Cell Proliferation in Fibrin Nanofibers. Molecules. 2019 Jul 27;24(15):2729.

- Lana, JF. Leukocyte-rich PRP versus leukocyte-poor PRP - The role of monocyte/macrophage function in the healing cascade. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2019;6.

- Zhou Y, Zhang J, Wu H, Hogan MV, Wang JHC. The differential effects of leukocyte-containing and pure platelet-rich plasma (PRP) on tendon stem/progenitor cells - implications of PRP application for the clinical treatment of tendon injuries. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015 Dec;6(1):173.

- N. Serhan C, Krishnamoorthy S, Recchiuti A, Chiang N. Novel Anti-Inflammatory-Pro-Resolving Mediators and Their Receptors. Curr Top Med Chem. 2011 Mar 1;11(6):629–47.

- Kargarpour Z, Panahipour L, Mildner M, Miron RJ, Gruber R. Lipids of Platelet-Rich Fibrin Reduce the Inflammatory Response in Mesenchymal Cells and Macrophages. Cells. 2023 Feb 16;12(4):634.

- Serhan CN, Sheppard KA. Lipoxin formation during human neutrophil-platelet interactions. Evidence for the transformation of leukotriene A4 by platelet 12-lipoxygenase in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1990 Mar 1;85(3):772–80.

- Sadtler K, Estrellas K, Allen BW, Wolf MT, Fan H, Tam AJ, et al. Developing a pro-regenerative biomaterial scaffold microenvironment requires T helper 2 cells. Science. 2016 Apr 15;352(6283):366–70.

- Uchiyama R, Toyoda E, Maehara M, Wasai S, Omura H, Watanabe M, et al. Effect of Platelet-Rich Plasma on M1/M2 Macrophage Polarization. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Feb 26;22(5):2336.

- Andia I, Martin JI, Maffulli N. Advances with platelet rich plasma therapies for tendon regeneration. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2018 Apr 3;18(4):389–98.

- Lin KY, Chen P, Chen ACY, Chan YS, Lei KF, Chiu CH. Leukocyte-Rich Platelet-Rich Plasma Has Better Stimulating Effects on Tenocyte Proliferation Compared With Leukocyte-Poor Platelet-Rich Plasma. Orthop J Sports Med. 2022 Mar 1;10(3):232596712210847.

- Romandini I, Boffa A, Di Martino A, Andriolo L, Cenacchi A, Sangiorgi E, et al. Leukocytes Do Not Influence the Safety and Efficacy of Platelet-Rich Plasma Injections for the Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Sports Med. 2024 Nov;52(13):3212–22.

- Liu X, Wang L, Ma C, Wang G, Zhang Y, Sun S. Exosomes derived from platelet-rich plasma present a novel potential in alleviating knee osteoarthritis by promoting proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis of chondrocyte via Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. J Orthop Surg. 2019 Dec;14(1):470.

- Colombo M, Raposo G, Théry C. Biogenesis, Secretion, and Intercellular Interactions of Exosomes and Other Extracellular Vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014 Oct 11;30(1):255–89.

- Gupta AK, Wang T, Rapaport JA, Talukder M. Therapeutic Potential of Extracellular Vesicles (Exosomes) Derived From Platelet-Rich Plasma: A Literature Review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2024 Dec;e16709.

- Murphy C, Withrow J, Hunter M, Liu Y, Tang YL, Fulzele S, et al. Emerging role of extracellular vesicles in musculoskeletal diseases. Mol Aspects Med. 2018 Apr;60:123–8.

- Cano A, Muñoz-Morales Á, Sánchez-López E, Ettcheto M, Souto EB, Camins A, et al. Exosomes-Based Nanomedicine for Neurodegenerative Diseases: Current Insights and Future Challenges. Pharmaceutics. 2023 Jan 16;15(1):298.

- Heidarzadeh M, Zarebkohan A, Rahbarghazi R, Sokullu E. Protein corona and exosomes: new challenges and prospects. Cell Commun Signal. 2023 Mar 27;21(1):64.

- Heidarzadeh M, Gürsoy-Özdemir Y, Kaya M, Eslami Abriz A, Zarebkohan A, Rahbarghazi R, et al. Exosomal delivery of therapeutic modulators through the blood–brain barrier; promise and pitfalls. Cell Biosci. 2021 Jul 22;11(1):142.

- Rajabi H, Konyalilar N, Erkan S, Mortazavi D, Korkunc SK, Kayalar O, et al. Emerging role of exosomes in the pathology of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases; destructive and therapeutic properties. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022 Apr 4;13(1):144.

- Penna F, Garcia-Castillo L, Costelli P. Extracellular Vesicles and Exosomes in the Control of the Musculoskeletal Health. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2024 Apr;22(2):257–65.

- Wan R, Liu S, Feng X, Luo W, Zhang H, Wu Y, et al. The Revolution of exosomes: From biological functions to therapeutic applications in skeletal muscle diseases. J Orthop Transl. 2024 Mar;45:132–9.

- Chaudhary PK, Kim S, Kim S. An Insight into Recent Advances on Platelet Function in Health and Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 May 27;23(11):6022.

- Torreggiani E, Perut F, Roncuzzi L, Zini N, Baglìo SR, Baldini N. Exosomes: novel effectors of human platelet lysate activity. Eur Cell Mater. 2014;28:137–51.

- Szunerits S, Chuang EY, Yang JC, Boukherroub R, Burnouf T. Platelet extracellular vesicles-loaded hydrogel bandages for personalized wound care. Trends Biotechnol. 2025 Jan;S0167779924003937.

- Institute of Orthopaedic Research and Biomechanics, University of Ulm, Helmholtzstr. 14, D-89081, Ulm, Germany, Kovtun A, Bergdolt S, Wiegner R, Radermacher P, Huber-Lang M, et al. The crucial role of neutrophil granulocytes in bone fracture healing. Eur Cell Mater. 2016 Jul 25;32:152–62.

- Iberg CA, Hawiger D. Natural and Induced Tolerogenic Dendritic Cells. J Immunol. 2020 Feb 15;204(4):733–44.

- Koupenova M, Clancy L, Corkrey HA, Freedman JE. Circulating Platelets as Mediators of Immunity, Inflammation, and Thrombosis. Circ Res. 2018 Jan 19;122(2):337–51.

- Shibuya, M. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) and Its Receptor (VEGFR) Signaling in Angiogenesis: A Crucial Target for Anti- and Pro-Angiogenic Therapies. Genes Cancer. 2011 Dec 1;2(12):1097–105.

- Everts PA, Devilee RJJ, Brown Mahoney C, van Erp A, Oosterbos CJM, Stellenboom M, et al. Exogenous Application of Platelet-Leukocyte Gel during Open Subacromial Decompression Contributes to Improved Patient Outcome. Eur Surg Res. 2008;40(2):203–10.

- Johal H, Khan M, Yung S hang P, Dhillon MS, Fu FH, Bedi A, et al. Impact of Platelet-Rich Plasma Use on Pain in Orthopaedic Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Health Multidiscip Approach. 2019 Jul;11(4):355–66.

- Kuffler, DP. Platelet-Rich Plasma Promotes Axon Regeneration, Wound Healing, and Pain Reduction: Fact or Fiction. Mol Neurobiol. 2015;27.

- Kuffler, D. Variables affecting the potential efficacy of PRP in providing chronic pain relief. J Pain Res. 2018 Dec;Volume 12:109–16.

- Kuffler DP, Foy C. Restoration of Neurological Function Following Peripheral Nerve Trauma. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Mar 6;21(5):1808.

- Mohammadi S, Nasiri S, Mohammadi MH, Malek Mohammadi A, Nikbakht M, Zahed Panah M, et al. Evaluation of platelet-rich plasma gel potential in acceleration of wound healing duration in patients underwent pilonidal sinus surgery: A randomized controlled parallel clinical trial. Transfus Apher Sci. 2017 Apr;56(2):226–32.

- Lutz C, Cheng J, Prysak M, Zukofsky T, Rothman R, Lutz G. Clinical outcomes following intradiscal injections of higher-concentration platelet-rich plasma in patients with chronic lumbar discogenic pain. Int Orthop [Internet]. 2022 Mar 28 [cited 2022 Apr 26]. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00264-022-05389-y.

- Migliorini F, Rath B, Tingart M, Baroncini A, Quack V, Eschweiler J. Autogenic mesenchymal stem cells for intervertebral disc regeneration. Int Orthop. 2019 Apr;43(4):1027–36.

- Gupta A, Jeyaraman M, Potty A. Leukocyte-Rich vs. Leukocyte-Poor Platelet-Rich Plasma for the Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis. Biomedicines. 2023 Jan 6;11(1):141.

- Jeyaraman M, Maffulli N, Gupta A. Stromal Vascular Fraction in Osteoarthritis of the Knee. Biomedicines. 2023 May 16;11(5):1460.

- Van Boxtel J, Vonk LA, Stevens HP, Van Dongen JA. Mechanically Derived Tissue Stromal Vascular Fraction Acts Anti-inflammatory on TNF Alpha-Stimulated Chondrocytes In Vitro. Bioengineering. 2022 Jul 27;9(8):345.

- Alexander, R. Overview of cellular stromal vascular fraction (cSVF) & biocellular uses of stem/stromal cells & matrix (tSVF+ HD-PRP) in regenerative medicine, aesthetic medicine and plastic surgery. J Stem Cell Res Dev Ther. 2019;2:304–12.

- Klein, JA. The Tumescent Technique: Anesthesia and Modified Liposuction Technique. Dermatol Clin. 1990;8(3):425–37.

- Simonacci F, Bertozzi N, Grieco MP, Raposio E. From liposuction to adipose-derived stem cells: indications and technique. Acta Bio Medica Atenei Parm. 2019 May 23;90(2):197–208.

- Kurita M, Matsumoto D, Shigeura T, Sato K, Gonda K, Harii K, et al. Influences of Centrifugation on Cells and Tissues in Liposuction Aspirates: Optimized Centrifugation for Lipotransfer and Cell Isolation: Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 Mar;121(3):1033–41.

- Williams SK, Wang TF, Castrillo R, Jarrell BE. Liposuction-derived human fat used for vascular graft sodding contains endothelial cells and not mesothelial cells as the major cell type. J Vasc Surg. 1994 May;19(5):916–23.

- Alexander, RW. Understanding Mechanical Emulsification (Nanofat) Versus Enzymatic Isolation of Tissue Stromal Vascular Fraction (tSVF) Cells from Adipose Tissue: Potential Uses in Biocellular Regenerative Medicine. :14.

- Vasilyev VS, Borovikova AA, Vasilyev SA, Khramtsova NI, Plaksin SA, Kamyshinsky RA, et al. Features and Biological Properties of Different Adipose Tissue Based Products. Milli-, Micro-, Emulsified (Nano-) Fat, SVF, and AD-Multipotent Mesenchymal Stem Cells. In: Plastic and Aesthetic Regenerative Surgery and Fat Grafting: Clinical Application and Operative Techniques. Springer; 2022. p. 91–107.

- Caplan AI, Correa D. The MSC: An Injury Drugstore. Cell Stem Cell. 2011 Jul;9(1):11–5.

- Li L, Xie T. STEM CELL NICHE: Structure and Function. 2005;30.

- Dallo I, Bernáldez P, Santos GS, Lana JF, Everts PA. Defining, optimizing, and measuring bone marrow aspirate and bone marrow concentrate. In: OrthoBiologics [Internet]. Elsevier; 2025 [cited 2025 Jan 28]. p. 47–59. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780128229026000210.

- Mohamed-Ahmed S, Fristad I, Lie SA, Suliman S, Mustafa K, Vindenes H, et al. Adipose-derived and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells: a donor-matched comparison. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018 Dec;9(1):168.

- Charbord, P. Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Historical Overview and Concepts. Hum Gene Ther. 2010 Sep;21(9):1045–56.

- Izadpanah R, Trygg C, Patel B, Kriedt C, Dufour J, Gimble JM, et al. Biologic properties of mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow and adipose tissue. J Cell Biochem. 2006 Dec 1;99(5):1285–97.

- Centeno C, Pitts J, Al-Sayegh H, Freeman M. Efficacy of Autologous Bone Marrow Concentrate for Knee Osteoarthritis with and without Adipose Graft. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014:1–9.

- da Silva Meirelles L, Fontes AM, Covas DT, Caplan AI. Mechanisms involved in the therapeutic properties of mesenchymal stem cells. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009 Oct;20(5–6):419–27.

- Cucchiarini M, Venkatesan JK, Ekici M, Schmitt G, Madry H. Human mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing therapeutic genes: From basic science to clinical applications for articular cartilage repair. Biomed Mater Eng. 2012;22(4):197–208.

- Centeno CJ, Pastoriza SM. PAST, CURRENT AND FUTURE INTERVENTIONAL ORTHOBIOLOGICS TECHNIQUES AND HOW THEY RELATE TO REGENERATIVE REHABILITATION: A CLINICAL COMMENTARY. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2020 Apr;15(2):301–25.

- Lana JF, da Fonseca LF, Azzini G, Santos G, Braga M, Cardoso Junior AM, et al. Bone Marrow Aspirate Matrix: A Convenient Ally in Regenerative Medicine. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Mar 9;22(5):2762.

- Liu C, Xiao K, Xie L. Advances in the Regulation of Macrophage Polarization by Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Implications for ALI/ARDS Treatment. Front Immunol. 2022 Jul 8;13:928134.

- Lee S, Chae DS, Song BW, Lim S, Kim SW, Kim IK, et al. ADSC-Based Cell Therapies for Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Review of Recent Clinical Trials. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Sep 30;22(19):10586.

- Caplan, AI. New MSC: MSCs as pericytes are Sentinels and gatekeepers: MSCs, PERICYTES, METASTASIS, REGENERATIVE MEDICINE. J Orthop Res. 2017 Jun;35(6):1151–9.

- Wu Y, Fu J, Huang Y, Duan R, Zhang W, Wang C, et al. Biology and function of pericytes in the vascular microcirculation. Anim Models Exp Med. 2023 Aug;6(4):337–45.

- Dias Moura Prazeres PH, Sena IFG, Borges IDT, De Azevedo PO, Andreotti JP, De Paiva AE, et al. Pericytes are heterogeneous in their origin within the same tissue. Dev Biol. 2017 Jul;427(1):6–11.

- Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Endothelial Cell Apoptosis in Angiogenesis and Vessel Regression.

- Festa J, AlZaim I, Kalucka J. Adipose tissue endothelial cells: insights into their heterogeneity and functional diversity. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2023 Aug;81:102055.

- Kakudo N, Minakata T, Mitsui T, Kushida S, Notodihardjo FZ, Kusumoto K. Proliferation-Promoting Effect of Platelet-Rich Plasma on Human Adipose–Derived Stem Cells and Human Dermal Fibroblasts: Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 Nov;122(5):1352–60.

- Guo J, Nguyen A, Banyard DA, Fadavi D, Toranto JD, Wirth GA, et al. Stromal vascular fraction: A regenerative reality? Part 2: Mechanisms of regenerative action. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016 Feb;69(2):180–8.

- Man K, Kallies A, Vasanthakumar A. Resident and migratory adipose immune cells control systemic metabolism and thermogenesis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2022 Mar;19(3):421–31.

- Cipolletta D, Feuerer M, Li A, Kamei N, Lee J, Shoelson SE, et al. PPAR-γ is a major driver of the accumulation and phenotype of adipose tissue Treg cells. Nature. 2012 Jun;486(7404):549–53.

- Lynch L, Michelet X, Zhang S, Brennan PJ, Moseman A, Lester C, et al. Regulatory iNKT cells lack expression of the transcription factor PLZF and control the homeostasis of Treg cells and macrophages in adipose tissue. Nat Immunol. 2015 Jan;16(1):85–95.

- Davies LC, Jenkins SJ, Allen JE, Taylor PR. Tissue-resident macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2013 Oct;14(10):986–95.

- Lacy P, Stow JL. Cytokine release from innate immune cells: association with diverse membrane trafficking pathways. Blood. 2011 Jul 7;118(1):9–18.

- Smith OJ, Jell G, Mosahebi A. The use of fat grafting and platelet-rich plasma for wound healing: A review of the current evidence. Int Wound J. 2019 Feb;16(1):275–85.

- Tatsis D, Vasalou V, Kotidis E, Anestiadou E, Grivas I, Cheva A, et al. The Combined Use of Platelet-Rich Plasma and Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promotes Healing. A Review of Experimental Models and Future Perspectives. Biomolecules. 2021 Sep 24;11(10):1403.

- Dallo I, Morales M, Gobbi A. Platelets and Adipose Stroma Combined for the Treatment of the Arthritic Knee. Arthrosc Tech. 2021 Nov;10(11):e2407–14.

- Eto H, Suga H, Inoue K, Aoi N, Kato H, Araki J, et al. Adipose Injury–Associated Factors Mitigate Hypoxia in Ischemic Tissues through Activation of Adipose-Derived Stem/Progenitor/Stromal Cells and Induction of Angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2011 May;178(5):2322–32.

- Mashiko T, Yoshimura K. How Does Fat Survive and Remodel After Grafting? Clin Plast Surg. 2015 Apr;42(2):181–90.

- Yu W, Wang Z, Dai Y, Zhao S, Chen H, Wang S, et al. Autologous fat grafting for postoperative breast reconstruction: A systemic review. Regen Ther. 2024 Jun;26:1010–7.

- Ding P, Lu E, Li G, Sun Y, Yang W, Zhao Z. Research Progress on Preparation, Mechanism, and Clinical Application of Nanofat. J Burn Care Res. 2022 Sep 1;43(5):1140–4.

- Hersant B, Sid-Ahmed M, Braud L, Jourdan M, Baba-Amer Y, Meningaud JP, et al. Platelet-Rich Plasma Improves the Wound Healing Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells through Paracrine and Metabolism Alterations. Stem Cells Int. 2019 Oct 31;2019:1–14.