Submitted:

10 February 2025

Posted:

13 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

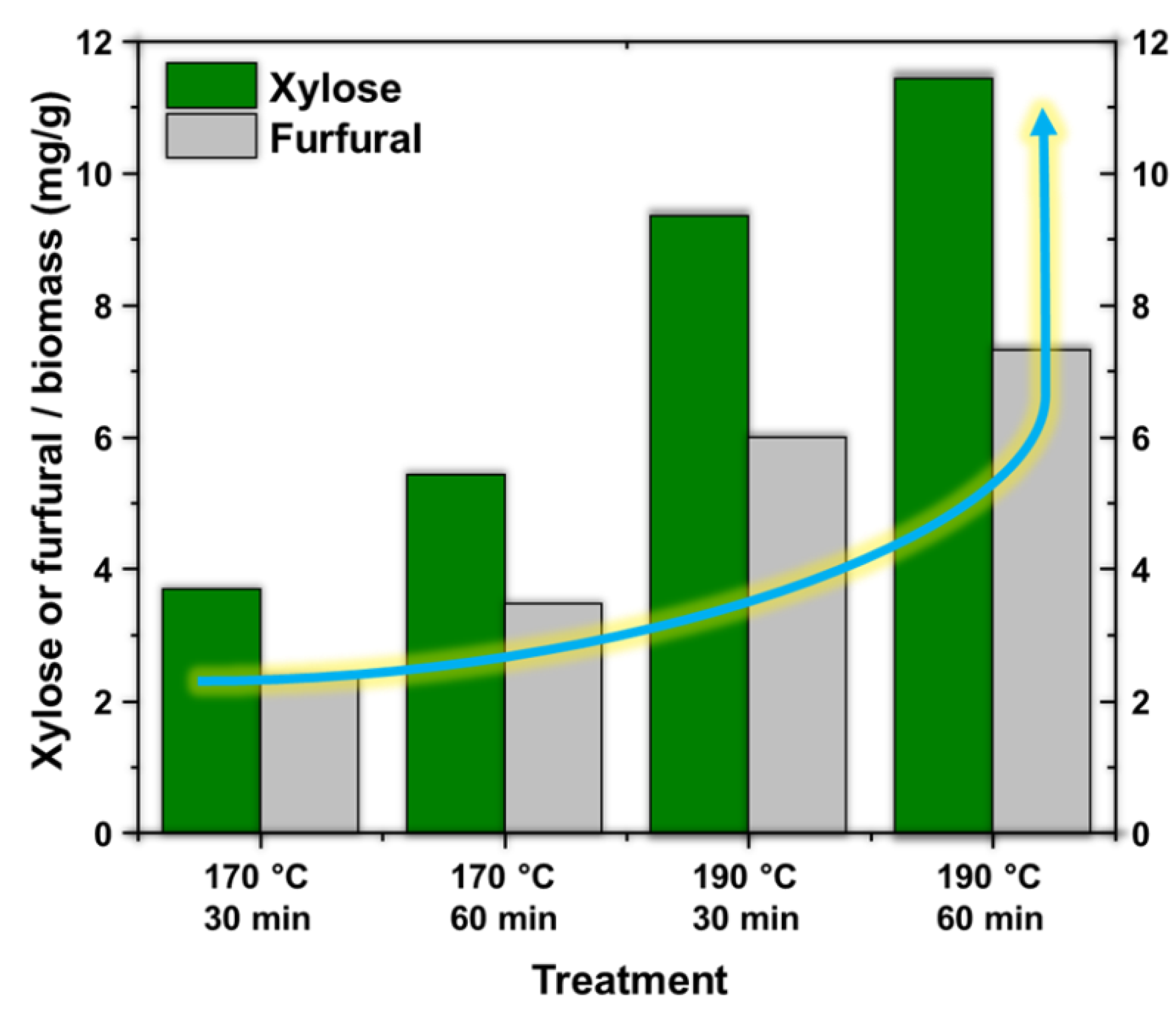

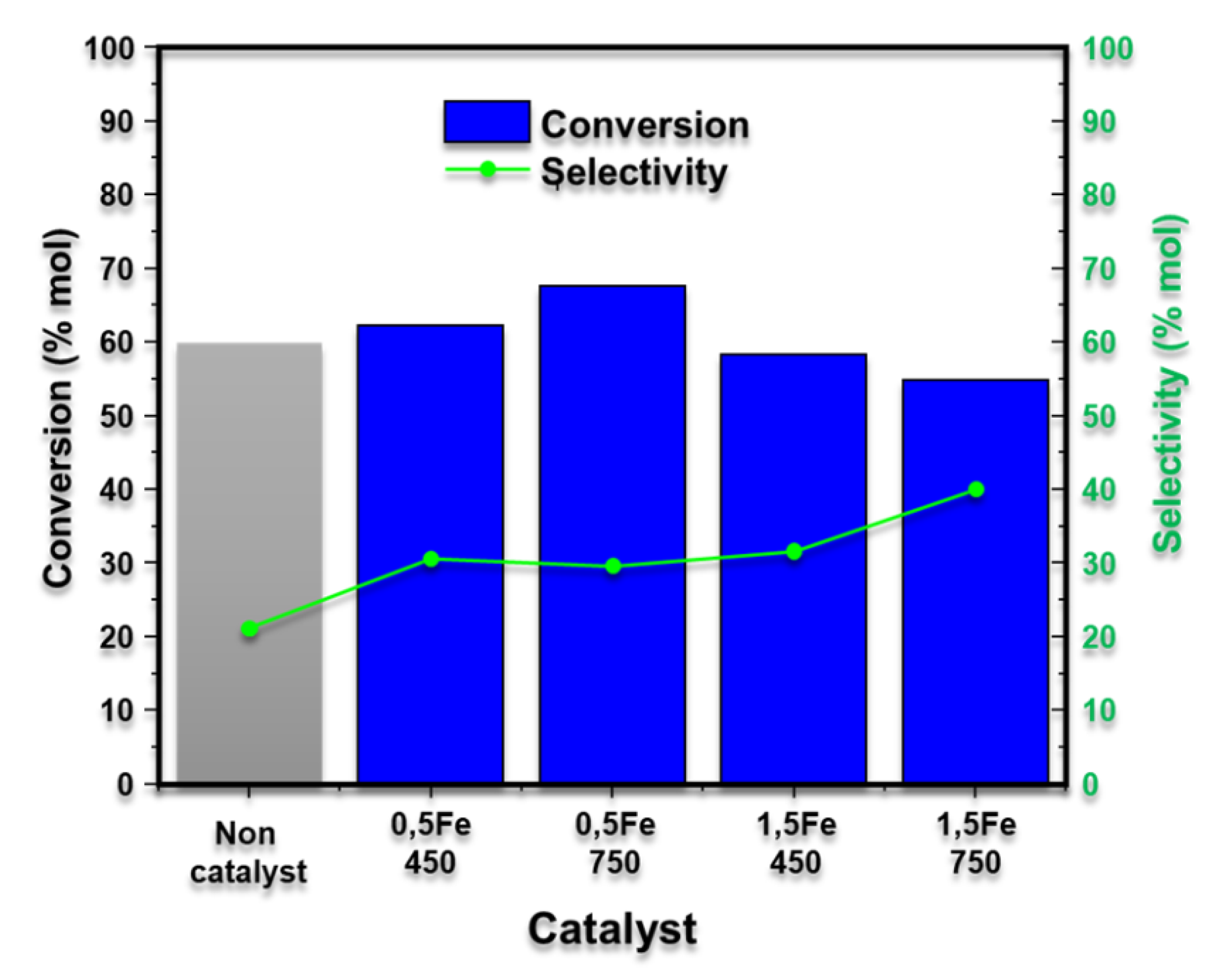

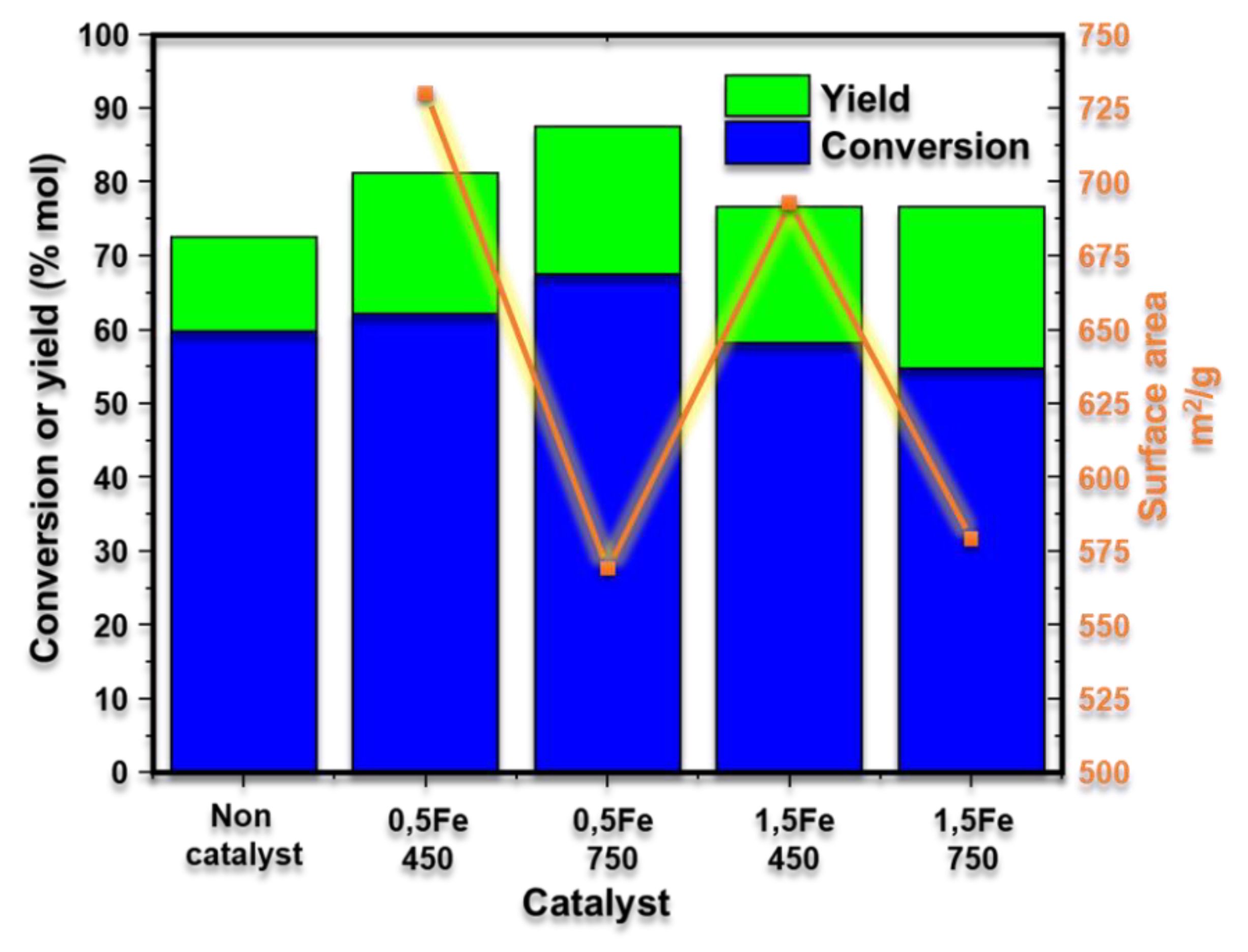

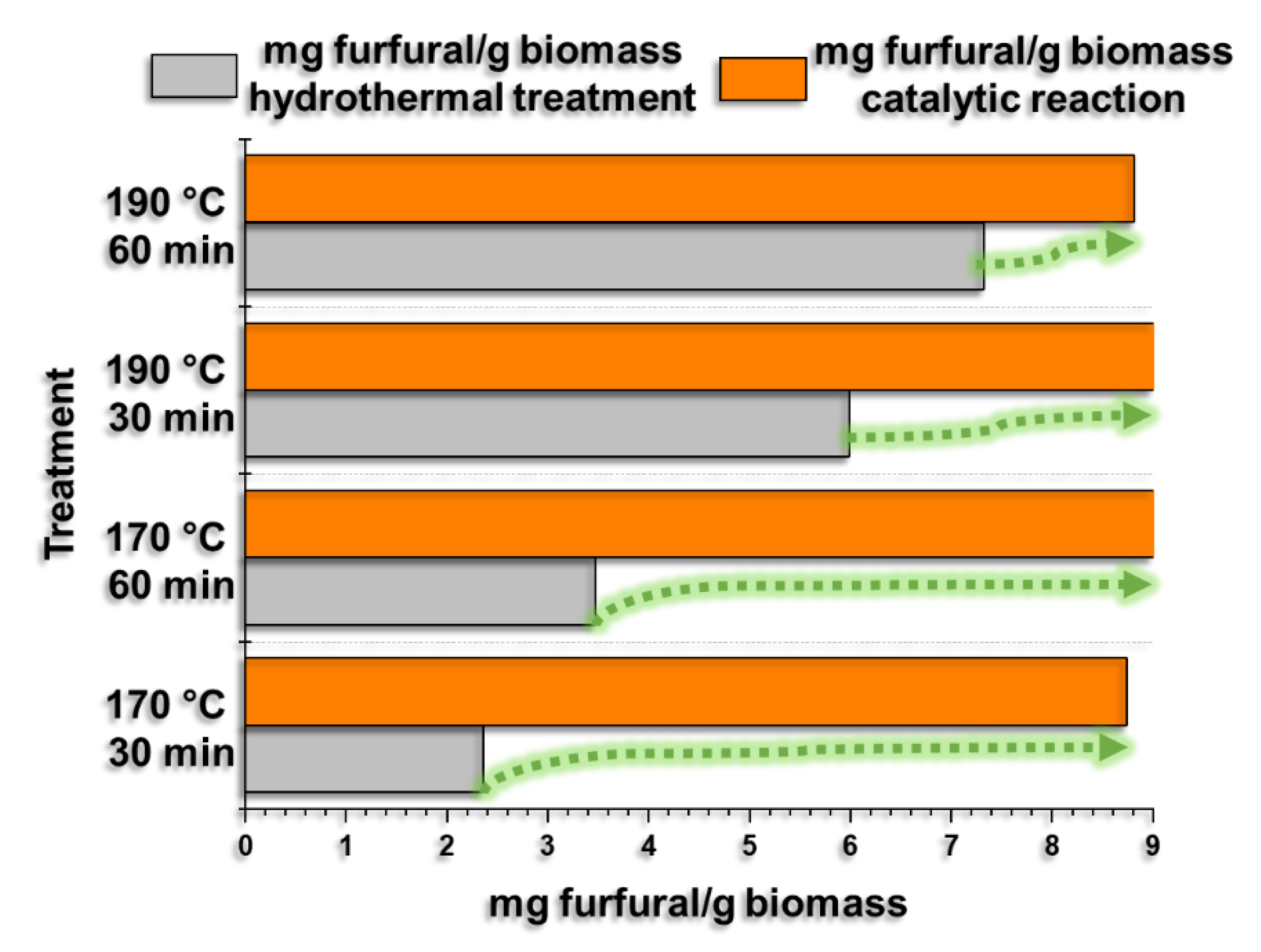

Solid Fe catalysts supported on SiO2 with Lewis and Brönsted acidity were synthesized using the sol-gel methodology. FTIR spectroscopy, XRD, Raman spectroscopy, BET isotherms, and SEM characterized the materials. Subsequently, they were used to dehydrate xylose to obtain furfural. It was observed that increasing the metal loading from 0.5 % to 1.5 % by mass increases the selectivity to furfural up to 40.09 %; in addition to this, it was observed that the calcination temperature has an effect concerning the conversion since the materials calcined at 450 °C present higher xylose conversion concerning the materials calcined at 750 °C. Finally, it was observed that the catalysts are active and effective in obtaining furfural from hydrolysates obtained from hydrothermal treatments of the residual biomass of the coffee crop, obtaining an average of 9.11 mg/g of furfural per gram of biomass.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biomass Material

2.2. Hydrothermal Treatment of Biomass

2.3. Catalysts Preparation

2.4. Characterization of Catalysts

2.5. Catalytic Conversion of Xylose and Coffee Waste to Furfural

2.6. Xylose an Furfural Quantification

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Coffee Waste Biomass

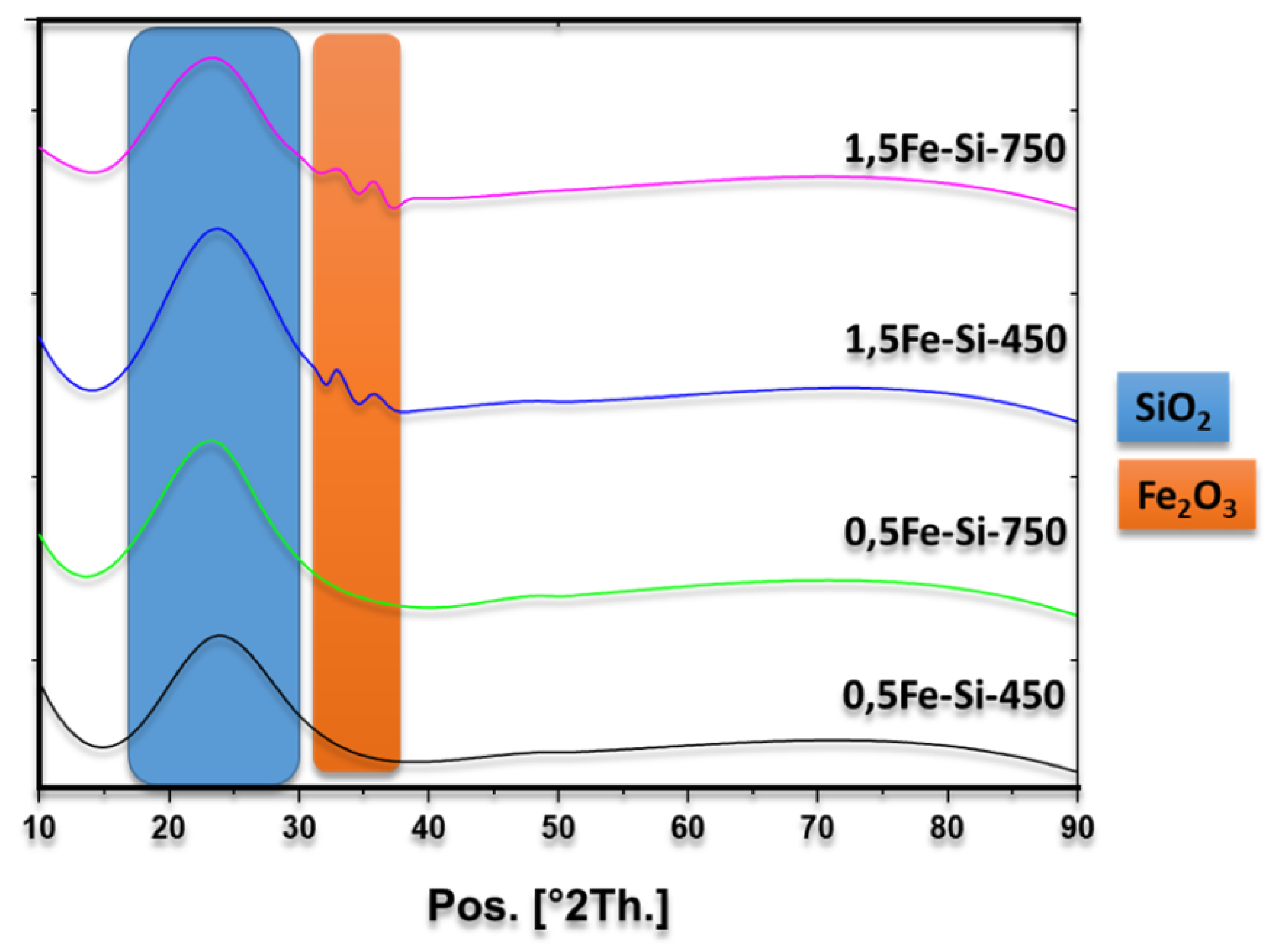

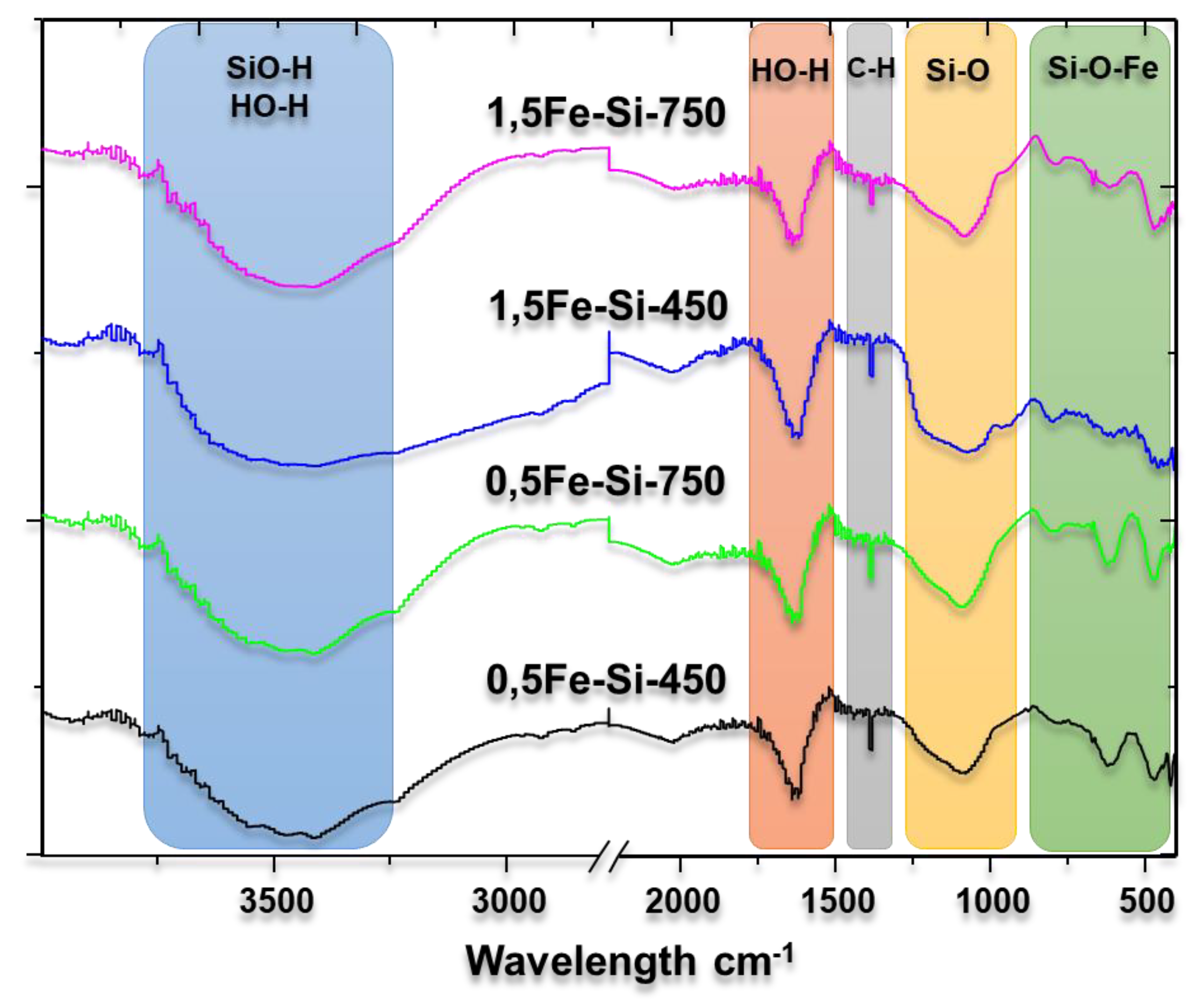

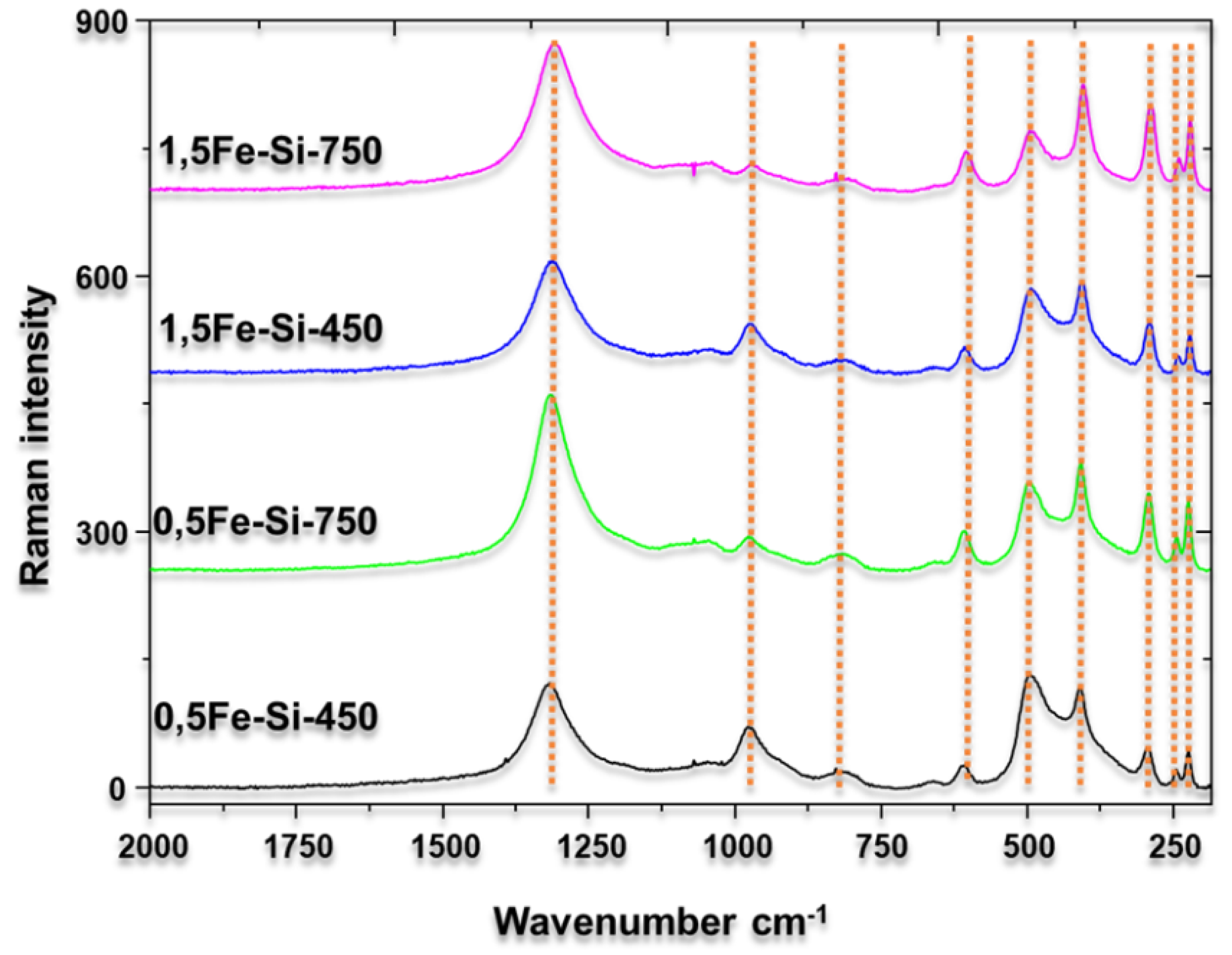

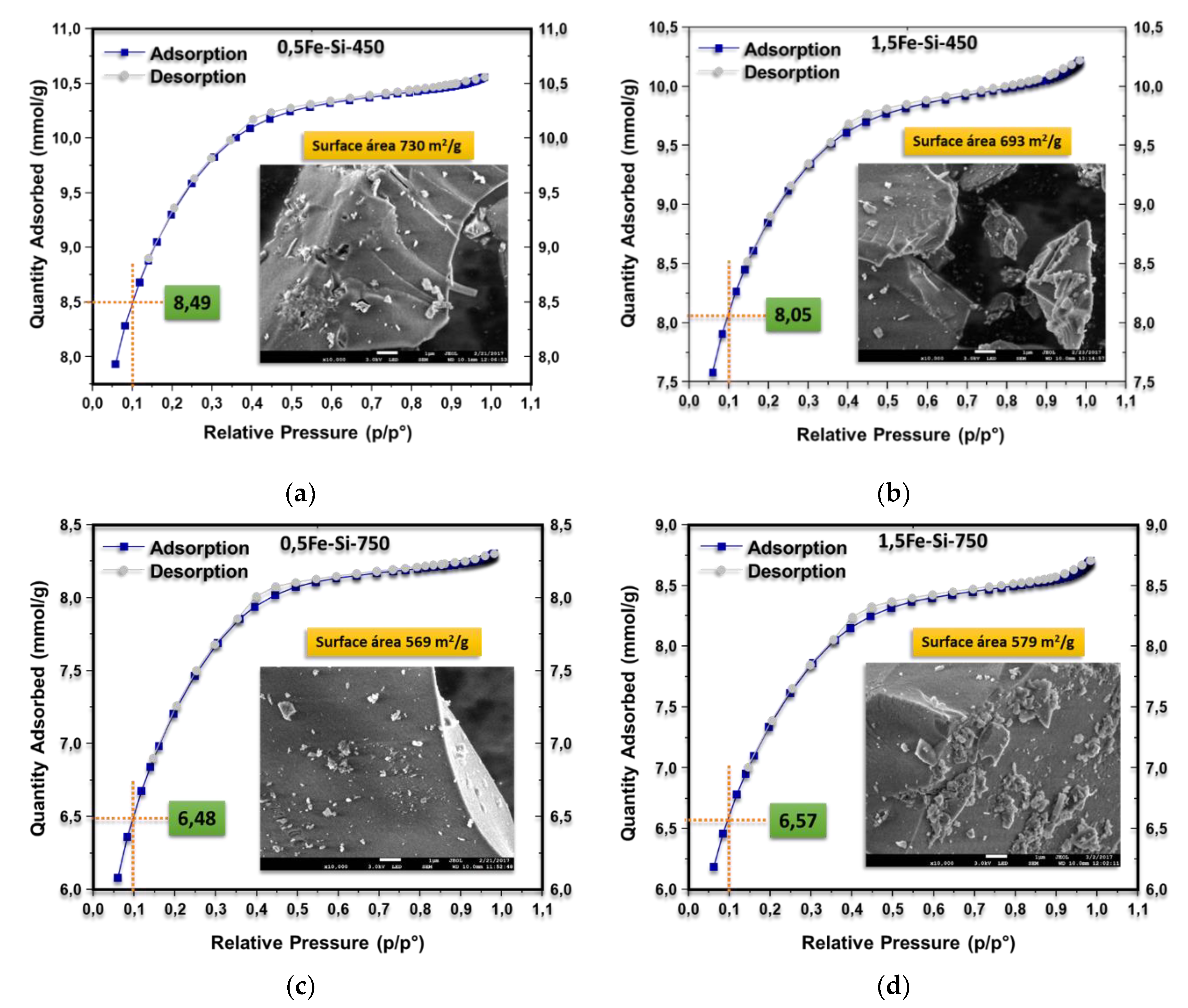

3.2. Characterization of Catalysts

3.3. Production of Furfural from Xylose

3.4. Production of Furfural from Coffee Residual Biomass Hydrolysates

4. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aristizábal-Marulanda, V.; Poveda-Giraldo, J.A.; Alzate, C.A.C. Comparison of furfural and biogas production using pentoses as platform. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 728, 138841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2. “International Coffee Organization - What’s New.” Accessed: 1 November 2022 [Online]. Available: https://www.ico.org/.

- Y. Piñeros-castro, G. A. Y. Piñeros-castro, G. A. Velasco, W. G. Cortes Ortiz, and J. Proaños, “Producción de azúcares fermentables por hidrólisis enzimática de cascarilla de arroz pretratada mediante explosión con vapor,” Revista Ión, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 23–28, 2011.

- W. G. Cortés Ortiz, “Tratamientos Aplicables a Materiales Lignocelulósicos para la Obtención de Etanol y Productos Químicos,” Revista de Tecnología, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 39–44, 2014.

- Pholjaroen, B.; Li, N.; Wang, Z.; Wang, A.; Zhang, T. Dehydration of xylose to furfural over niobium phosphate catalyst in biphasic solvent system. J. Energy Chem. 2013, 22, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulie, N.W.; Woldeyes, B.; Demsash, H.D. Synthesis of lignin-carbohydrate complex-based catalyst from Eragrostis tef straw and its catalytic performance in xylose dehydration to furfural. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 171, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Zhang, C.; Cao, Y.; Zhan, J.; Fan, J.; Clark, J.H.; Zhang, S. Conversion of xylose into furfural over MC-SnOx and NaCl catalysts in a biphasic system. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R.; Jiang, L.; Yin, D.; Lv, F.; Yu, S.; Li, L.; Liu, S.; Wu, Q.; Liu, Y. Core-shell catalyst WO3@mSiO2-SO3H interfacial synergy catalyzed the preparation of furfural from xylose. Mol. Catal. 2022, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, P.; Yi, H.; Yang, M.; Wang, G. Catalytic conversion of xylose to furfural over the solid acid /ZrO2–Al2O3/SBA-15 catalysts. Carbohydr. Res. 2011, 346, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusanen, A.; Kupila, R.; Lappalainen, K.; Kärkkäinen, J.; Hu, T.; Lassi, U. Conversion of Xylose to Furfural over Lignin-Based Activated Carbon-Supported Iron Catalysts. Catalysts 2020, 10, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Sluiter et al., “Determination of total solids in biomass and total dissolved solids in liquid process samples,” National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), no. March, pp. 2008; 5.

- Sluiter, B. Hames, R. Ruiz, C. Scarlata, J. Sluiter, and D. Templeton, “Determination of Ash in Biomass Laboratory Analytical Procedure ( LAP ) Issue Date : 7 / 17 / 2005 Determination of Ash in Biomass Laboratory Analytical Procedure ( LAP ),” no. January, 2008.

- Sluiter, B. Hames, R. Ruiz, and C. Scarlata, “Determination of structural carbohydrates and lignin in biomass,” Laboratory analytical …, vol. 2011, no. July, 2008.

- Ortiz, W.G.C.; Delgado, D.; Fajardo, C.A.G.; Agouram, S.; Sanchís, R.; Solsona, B.; Nieto, J.M.L. Partial oxidation of methane and methanol on FeOx-, MoOx- and FeMoOx -SiO2 catalysts prepared by sol-gel method: A comparative study. Mol. Catal. 2020, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero, J.A.; Moncada, J.; Cardona, C.A. Techno-economic analysis of bioethanol production from lignocellulosic residues in Colombia: A process simulation approach. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 139, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. , V.A.; P., Á.G.; A., C.A.C. Biorefineries based on coffee cut-stems and sugarcane bagasse: Furan-based compounds and alkanes as interesting products. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 196, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xi, G.; Zhang, J.; Yu, H.; Wang, X. Efficient catalytic system for the direct transformation of lignocellulosic biomass to furfural and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 224, 656–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Pan, X. Efficient sugar production from plant biomass: Current status, challenges, and future directions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, T.R.; Pattnaik, F.; Nanda, S.; Dalai, A.K.; Meda, V.; Naik, S. Hydrothermal pretreatment technologies for lignocellulosic biomass: A review of steam explosion and subcritical water hydrolysis. Chemosphere 2021, 284, 131372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, F.; Iqbal, A. Silica supported amorphous molybdenum catalysts prepared via sol–gel method and its catalytic activity. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2011, 141, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Ortiz, W.G.; Baena-Novoa, A.; Guerrero-Fajardo, C.A. Structuring-agent role in physical and chemical properties of Mo/SiO2 catalysts by sol-gel method. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2018, 89, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajardo, C.A.G.; N’guyen, Y.; Courson, C.; Roger, A.C. Fe/SiO2 catalysts for the selective oxidation of methane to formaldehyde. Ing. E Investig. 2006, 26, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alayat, A.; Mcllroy, D.; McDonald, A.G. Effect of synthesis and activation methods on the catalytic properties of silica nanospring (NS)-supported iron catalyst for Fischer-Tropsch synthesis. Fuel Process. Technol. 2018, 169, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yao, K.; Fu, L.-H.; Ma, M.-G. Selective synthesis of Fe3O4, γ-Fe2O3, and α-Fe2O3 using cellulose-based composites as precursors. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 2135–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Niu, Y.; Meng, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, J. Structural evolution and characteristics of the phase transformations between α-Fe2O3, Fe3O4 and γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles under reducing and oxidizing atmospheres. CrystEngComm 2013, 15, 8166–8172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, G.S. Iron oxide surfaces. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2016, 71, 272–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, V.K.; Kumar, A.S.; Ali, A.; Prasad, S.; Srivastava, P.; Mallick, S.P.; Ershad; Singh, S. P.; Pyare, R. Assessment of nickel oxide substituted bioactive glass-ceramic on in vitro bioactivity and mechanical properties. Boletin De La Soc. Espanola De Ceram. Y Vidr. 2016, 55, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Brinker and G. Scherer, “Structural Evolution during Consolidation,” in Sol-Gel Science, San Diego: Academic Press, 1990, ch. 9, pp. 514–615. [CrossRef]

- Pudukudy, M.; Yaakob, Z. Methane decomposition over Ni, Co and Fe based monometallic catalysts supported on sol gel derived SiO2 microflakes. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 262, 1009–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, K.M.; Makhlouf, S.A. High surface area thermally stabilized porous iron oxide/silica nanocomposites via a formamide modified sol–gel process. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2008, 254, 3767–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Z.; Zeng, H. A catalyst-free approach for sol–gel synthesis of highly mixed ZrO2–SiO2 oxides. J. Non-Crystalline Solids 1999, 243, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, R.; Levin-Elad, M. Metal Oxide (TiO2, MoO3, WO3) Substituted Silicate Xerogels as Catalysts for the Oxidation of Hydrocarbons with Hydrogen Peroxide. J. Catal. 1997, 166, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudron, E.; Tfayli, A.; Monnier, C.; Manfait, M.; Prognon, P.; Pradeau, D. Identification of hematite particles in sealed glass containers for pharmaceutical uses by Raman microspectroscopy. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2011, 54, 866–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Li, Y.; An, D.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y. Selective oxidation of methane to formaldehyde by oxygen over silica-supported iron catalysts. J. Nat. Gas Chem. 2009, 18, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubb, A.; Allen, H.C. Vibrational Spectroscopic Characterization of Hematite, Maghemite, and Magnetite Thin Films Produced by Vapor Deposition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2010, 2, 2804–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, P.M.C.; Nazzarro, M.S.; Parentis, M.L.; Gonzo, E.E.; Bonini, N.A. Effect of hydrothermal treatment on Cr-SiO2 mesoporous materials. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2013, 101, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, K.S.W. Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems with special reference to the determination of surface area and porosity (Provisional). Pure Appl. Chem. 1982, 54, 2201–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perego and, P. Villa, “Catalyst preparation methods,” Catalysis Today, vol. 34, pp. 281–305, 1997.

- Millán, G.G.; El Assal, Z.; Nieminen, K.; Hellsten, S.; Llorca, J.; Sixta, H. Fast furfural formation from xylose using solid acid catalysts assisted by a microwave reactor. Fuel Process. Technol. 2018, 182, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Hu, X.; Lam, F.L.-Y. Modified coal fly ash waste as an efficient heterogeneous catalyst for dehydration of xylose to furfural in biphasic medium. Fuel 2019, 239, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xi, G.; Yu, K.; Yu, H.; Wang, X. Furfural production from biomass–derived carbohydrates and lignocellulosic residues via heterogeneous acid catalysts. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2017, 98, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Shao, Y.; Liu, P.; Zhang, L.; Gao, G.; Dong, D.; Zhang, S.; Hu, G.; Xu, L.; Hu, X. A solid iron salt catalyst for selective conversion of biomass-derived C5 sugars to furfural. Fuel 2021, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, H.T.; Siah, W.R.; Yuliati, L. Enhanced adsorption of acetylsalicylic acid over hydrothermally synthesized iron oxide-mesoporous silica MCM-41 composites. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2016, 65, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttha, S.; Youngme, S.; Wittayakun, J.; Loiha, S. Formation of iron active species on HZSM-5 catalysts by varying iron precursors for phenol hydroxylation. Mol. Catal. 2018, 461, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | This work | [1] | [15] | [16] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture | 3,11 ± 0,0061 | 9,11 ± 0,39 | 4,12 | 11,00 |

| ashes | 7,60 ± 0,064 | 0,96 ± 0,13 | 2,27 | 1,27 ± 0,03 |

| Cellulose | 19,60 ± 0,59 | 35,13 ± 0,81 | 37,35 | 40,39 ± 2,20 |

| Hemicellulose | 14,90 ± 0,45 | 11,42 ± 0,31 | 27,79 | 34,01 ± 1,20 |

| Lignin | 16,90 ± 0,51 | 23,27 ± 0,25 | 19,81 | 10,13 ± 1,30 |

| Wavelength (cm-1) | Assignment |

|---|---|

| 3750 | Isolated neighborhood SiO-H extension |

| 3660 | Extension of hydrogen bond SiO-H or internal SiO-H extension |

| 3540 | SiO-H extension of surface silanol groups bonded by hydrogen to molecular water |

| 3500-3400 | O-H extension of hydrogen bonded to molecular water |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).