1. Entropic States and the Hubble Sphere Energy Gap (Mass Gap)

Entropic gravity is an interesting and evolving theory; see [

4,

5]. The number of entropic states plays a central role in entropic gravity and is normally given as:

where

R is the black hole event horizon, that is the Schwarzschild radius if we limit ourselves to Schwarzschild black holes. This is essentially the Bekenstein-Hawking [

6,

7,

8] entropy for a black hole with a surface area equal to

, where

is the Planck length [

9,

10]. In the case above, this is simply the surface area of the black hole divided by the Planck area. However, we introduce a minor modification: since

represents the surface area of a Planck square, we will instead compare the spherical surface area of the black hole with the spherical Planck surface area. This gives:

In a Schwarzschild black hole, the Hubble radius is equal to the Schwarzschild radius. This can be seen from the critical mass, which is given by

. We are here working in a

cosmological model so the critical mass will vary over time. Solving for

, we obtain:

which is identical to the Schwarzschild radius for a black hole with mass

. This means for the Hubble sphere we have:

where

is the Hubble radius at time

t.

Haug [

1] has recently suggested that the Hubble sphere has an energy gap or an energy-equivalent mass gap; see also [

3,

11]. The idea is very simple: a photon cannot have a wavelength longer than the diameter of the Hubble sphere (or potentially the radius). No photon can have a longer wavelength than this, particularly in a black hole universe. The idea of black hole universe was introduced by at least 1972 by Pathria (1972) [

12] and is actively discussed to this day, see [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. The energy gap is simply given by:

where

represents the minimum possible observable energy in the Hubble sphere, corresponding to the photon with the longest possible wavelength. This is the same as the Hubble sphere energy gap

, just two different terms for the same concept. Furthermore, since we have Einstein’s equation

, the minimum equivalent mass above zero, that we have called the Hubble sphere mass gap, must be:

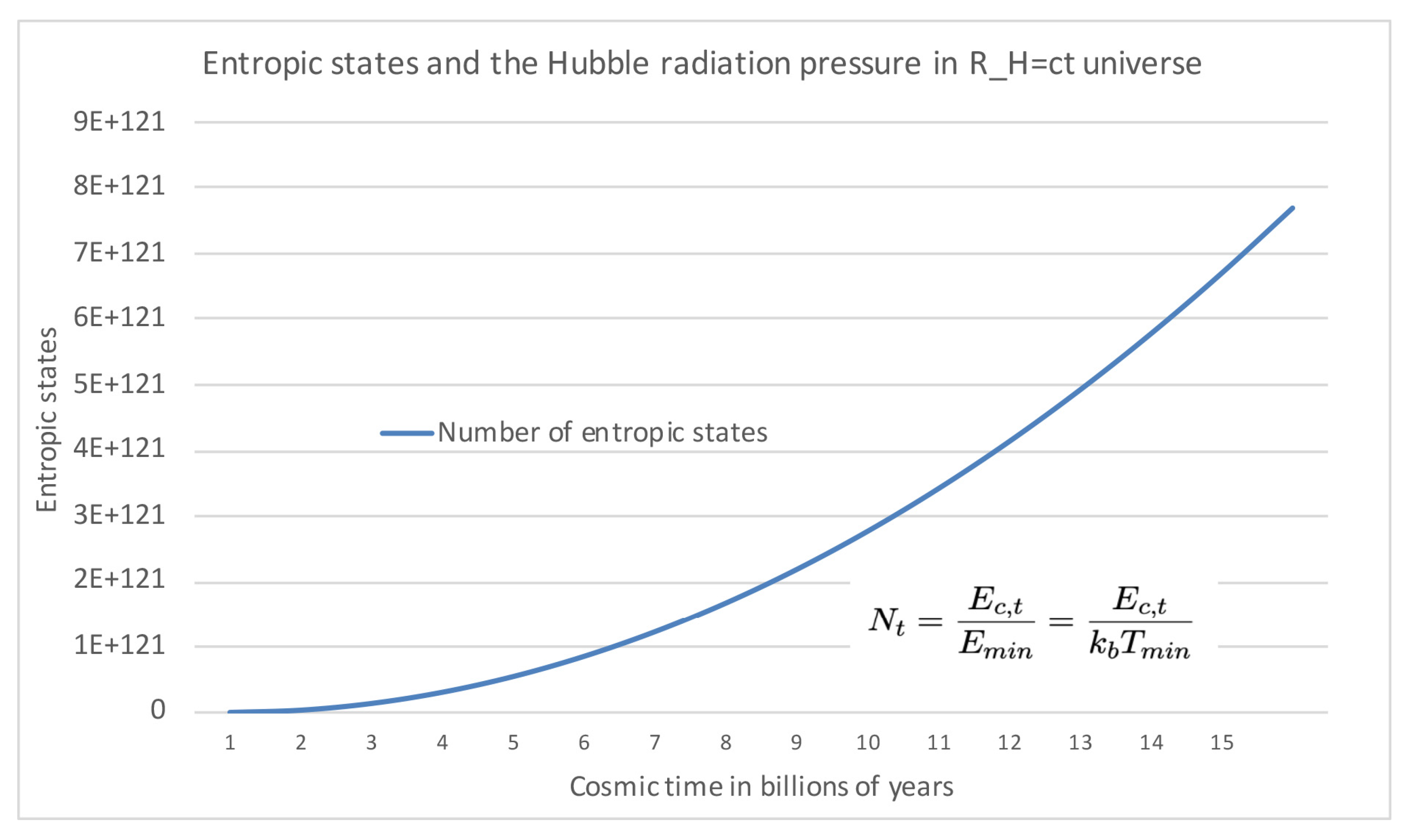

The number of entropic states in the Hubble sphere is given by:

the number of stats clculated here is given for when

as then

. Haug [

3] has also linked the minimum energy in the Hubble sphere to a minimum temperature, given simply as:

The entropic states (number of degrees of freedom) can therefore also be described as:

Note that

, and since we assume

, this means

is a deterministic function dependent on

over time, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

This means the entropic force can be described as (see also Tatum and Haug [

23] who have pointed out the entropic force in their

model as

, this can be re-written as:

where

is the entropic energy. Be aware also

is time dependent as we have

. The meaning of entropy is often defied as a measure of the unavailable energy in a closed thermodynamic system. In a black hole universe the Hubble sphere is indeed a closed thermodynamic system.

This is also fully consistent with [

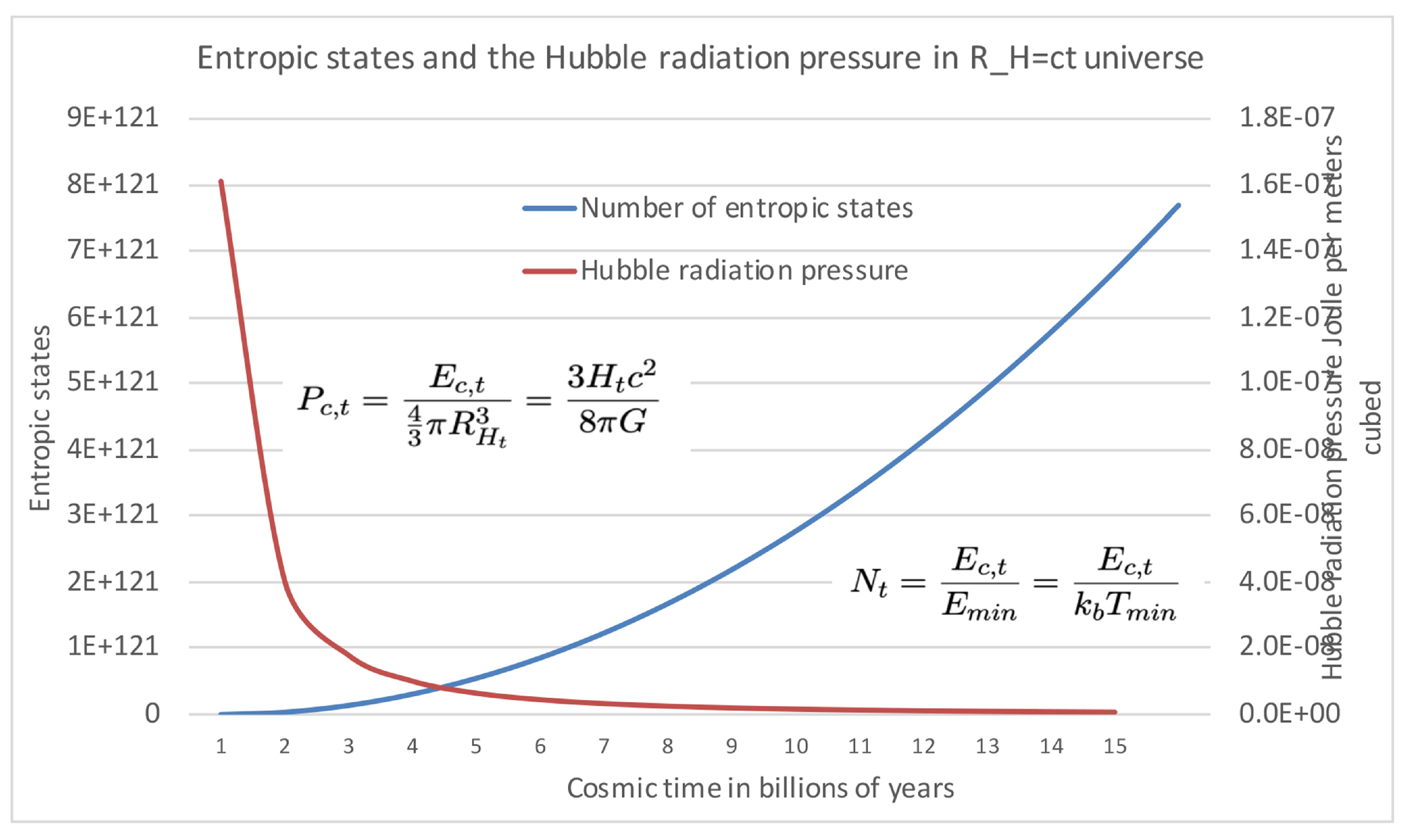

24], where Haug and Wojnow recently derived the Hubble Radiation Pressure Law:

where Haug and Wojnow describe the Hubble radiation pressure as:

As they describe it is identical to the critical energy (density), but link it to the CMB temperature. Further is the Hubble volume. The suggested Hubble radiation pressure and its corresponding entropic force is causing the black hole universe not to collapse into a singularity.

2. The Hubble Radiation Pressure Hindering the Energy and Mass Inside the Black Hole Universe to Collapse into a Center Singularity

The Hubble radiation pressure [

24]:

, when assuming

in black hole cosmology, will vary over time, as shown in

Figure 2, and prevent the mass and energy of the universe from collapsing into a central singularity.

We can see that as the entropic states increase with cosmic time as it expectedly should, the Haug and Wojnow Hubble radiation pressure (energy density) decreases. The reason for this is that the energy becomes more dispersed. Tatum and Haug [

23] later refer and discuss the same radiation pressure as entropic energy density and interestingly link it to a entropic force

. The interpretation may vary depending on whether one also considers it in terms of entropy. Therefore, it is important to highlight this counteracting force to gravity from different perspectives and papers throwing light at the topic from different angles is what science is about.

3. The Geometric Mean Temperature Is the CMB Temperature and It Is Linked to the Minimum and Maximum Temperature

Since the minimum temperature in the Hubble sphere seems to play an important role in cosmic entropy, it is also worth mentioning that it plays a significant role in the CMB temperature as well. Haug and Tatum [

11] have demonstrated how the CMB temperature is simply related to the geometric mean of basically the minimum and maximum physical temperatures. Haug [

3] has elaborated further on this and provided the elegant formula:

This is, at a deeper level, identical to the CMB formula that Haug and Wojnow [

25,

26] have derived from the Stefan-Boltzmann law [

27,

28], which, in turn, is consistent with the CMB prediction formula first heuristically suggested by Tatum et al. [

29]. It is important to be aware the CMB is considered a almost perfect black body, as described by for example Muller et al. [

30] that states :

“Observations with the COBE satellite have demonstrated that the CMB corresponds to a nearly perfect black body characterized by a temperature at , which is measured with very high accuracy, ."

Be aware that while the Planck temperature is a constant, , the minimum temperature varies as we travel back in time in the universe, as it is given by .

While the geometric mean temperature (energy) is relatively easy to detect and is likely the most precisely measured cosmological parameter [

31,

32,

33,

34], the minimum temperature is hard to detect because it is so small, approximately

. However, the minimum temperature is likely detectable indirectly as a minimum acceleration caused by radiation aceleraiton of about the order of

, something we will get back to in section 4.

The maximum temperature, which is the Planck temperature is likely linked to quantum gravity and lasts only about the Planck time, making it also nearly impossible to detect directly. However, it may be detected indirectly as gravity itself; see [

35,

36]. Haug [

37,

38,

39] has recently demonstrated that Planck units can be measured from a series of gravitational observations without any knowledge of

G.

4. Could It Be That the Entropy Force Is Detectable as a Minimum Acceleration or Indirectly Through also the CMB Temperature?

The entropic force, in our view, could be detectable, as it predicts a minimum acceleration of approximately:

That is for the case when (so ) now.

This value is close to the minimum acceleration proposed in Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND) [

40,

41]. Also, be aware that:

A minimum acceleration close to

plays an important role in MOND, as discussed by Milgrom [

41], and in Verlinde’s Emergent Gravity model [

42].

Our minimum temperature from the energy gap also clearly corresponds, at least mathematically, to the Unruh temperature. The Unruh [

43] temperature is given by:

where

a is the Unruh acceleration. If we instead input our minimum acceleration, we obtain:

which is identical to our Hubble sphere minimum temperature, differing only by a factor of

. The minimum temperature is also closely connected to the Hawking [

44] temperature, as for the Hubble sphere, it is given by:

where

g is the gravitational acceleration. For the Hubble sphere, we can set

, and we obtain:

The minimum temperature

is so small it is unlikely to be easy to detect. But it can be detected indirectly through the CMB temperature as the CMB temperature is given by the formula recently given by Hayg

So solved for

we get:

And

can be easily measured, and since the Planck temperature is a constant, it can be calculated. This allows us to indirectly detect the entropic temperature, as it is linked to the CMB temperature. The CMB temperature is the geometric mean of the minimum and maximum physically possible temperatures within the Hubble sphere.

Since the Planck temperature is constant, we can calculate it using the traditional method, or it can even be extracted from the Hubble sphere using:

Thus, to determine the Planck temperature, all we need is the Hubble constant and the CMB temperature, even though it is more precisely calculated using the traditional Max Planck approach: . The important point here is we can extract the Planck temperature from observable cosmology parameters. And the reason for this is in our view that the Planck temperature is linked to gravity, and gravity naturally affect even the cosmological scale.

Table 1 presents these three different temperatures and their relationships. Therefore, one could say that detecting the CMB temperature is equivalent to indirectly detecting both the maximum and minimum temperatures in the universe, as the CMB temperature is simply the geometric mean of the two. This is fully consistent with a subgroup of

cosmology.

If this entropic temperature (Hubble radiation pressure) can be indirectly observed both in the minimum observed acceleration of galaxy rotation arms and through the CMB temperature, then the term “

Dark Energy”, as Tatum and Haug [

23] have compared this radiation pressure to, may be somewhat of a misnomer. On the other hand, what one calls this radiation pressure is largely a matter of wording and labeling. The important point is that we have built a very solid mathematical framework for entropic states in the universe and linked it to the minimum (entropic temperature), the maximum (Planck temperature), and even the directly detectable CMB temperature. This is fully consistent with recent developments in

cosmology (see [

45,

46]). Further if we should term it dark energy as Tatum and Haug has linked it to, then it is clear from the rest of their model that this dark energy is not needed to get a perfect match with the full distance ladder of SN Ia (in the HTC model). It is only needed indirectly to avoid the black hole universe to collapse into a singularity and to keep it expanding or alternatively to keep the Hubble sphere stay steady state. Steady state models should not be excluded fully yet at this point something we will come back to in a future paper.

An interesting question is the CMB temperature could be signature of two opposite forces, the gravity force that we claim must be linked to the Planck temperature and the Planck scale and the entropic force that we link to the minimum temperature (entropic temperature). The geometric mean bind these two extreme temperatures that both are not possible to detect directly but only indirectly together in the easily observable CMB temperature [

3]. The CMB temperature is then a type of equilibrium temperature between two forces, the gravity force and the entropic force.

5. Other Ways to Express the Numbers of Entropic States

If we take the critical mass in the Hubble sphere and divide it by the mass gap, or the critical energy and divide it by the mass gap, Haug [

25] has demonstrated:

where

is the reduced Compton wavelength of the critical mass,

. This is the same as estimated as given by [

47]:

which is identical to

and also in a

universe it is clear that

, so this is also identical to

( the Bekenstein-Hawking entropy), see also [

48].

Haug [

25] has also demonstrated that one must have:

This even means the entropic force can be described as:

And the entropic force can then also be described as:

6. Conclusions

We have demonstrated that the entropic states in the universe correspond simply to the critical ’Friedmann’ energy divided by the Hubble energy gap: . It is therefore possible that the entropic force is actually detectable, as this energy gap also seems lead to a minimum acceleration, similar to what has been observed in galaxy rotation curves.

In addition, this minimum energy is related to a minimum temperature that we also have called entropic temperature. This entropic temperature is linked to the CMB temperature and the Planck temperature by . Since the Planck temperature is known and the CMB temperature is easily measurable, we can say that this minimum Hubble sphere temperature (the entropic temperature) is easily and indirectly detectable. The Hubble radiation pressure is what keeps a black hole Hubble sphere universe from collapsing into a singularity over time. Entropy is related to the counterforce of gravity on a cosmic scale and this force is indirectly detectable through both minimum acceleration and the CMB temperature.

References

- E. G. Haug. The black hole mass-gap and its relation to Bekenstein-Hawking entropy leads to potential quantization of black holes and a minimum gravitational acceleration in the universe. Cambridge Engage, Physics and Astronomy, preprint, 2024. URL https://www.cambridge.org/engage/coe/article-details/676598be81d2151a02668356.

- E. G.. Haug. The Hubble sphere mass-gap leads to a gravitational acceleration gap that could be linked to Milgrom MOND. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge Engage, Physics and Astronomy: preprint archive, 2024. URL https://www.cambridge.org/engage/coe/article-details/676d394281d2151a02fa1e33.

- E. G. Haug. Geometric mean cosmology predicts the CMB temperature now and in past epochs. Cambridge Engage, Physics and Astronomy, preprint, 2025. URL https://www.cambridge.org/engage/coe/article-details/67a2866381d2151a022e25e1.

- E. Verlinde. On the origin of gravity and the laws of newton. Journal of High Energy Physics, 2011:29, 2011. [CrossRef]

- N. Roos. Entropic forces in brownian motion. American Journal of Physics, 82:1161, 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Bekenstein. Black holes and the second law. Lettere al Nuovo Cimento, 4(15):99, 1972. [CrossRef]

- J. Bekenstein. Black holes and entropy. Physical Review D, 7(8):2333, 1973. [CrossRef]

- S. Hawking. Black holes and thermodynamics. Physical Review D, 13(2):191, 1976. [CrossRef]

- M. Planck. Natuerliche Masseinheiten. Der Königlich Preussischen Akademie Der Wissenschaften: Berlin, Germany, 1899. URL https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/93034#page/7/mode/1up.

- M. Planck. Vorlesungen über die Theorie der Wärmestrahlung. Leipzig: J.A. Barth, p. 163, see also the English translation “The Theory of Radiation" (1959) Dover, 1906.

- E. G. Haug and E. T. Tatum. The Hawking Hubble temperature as a minimum temperature, the Planck temperature as a maximum temperature and the CMB temperature as their geometric mean temperature. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Physics, 12:3328, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Pathria. The universe as a black hole. Nature, 240:298, 1972. [CrossRef]

- W. M. Stuckey. The observable universe inside a black hole. American Journal of Physics, 62:788, 1994. [CrossRef]

- P. Christillin. The machian origin of linear inertial forces from our gravitationally radiating black hole universe. The European Physical Journal Plus, 129:175, 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. X. Zhang and C. Frederick. Acceleration of black hole universe. Astrophysics and Space Science, 349:567, 2014. [CrossRef]

- N. Popławski. The universe in a black hole in Einstein–Cartan gravity. The Astrophysical Journal, 832:96, 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. X. Zhang. The principles and laws of black hole universe. Journal of Modern Physics, 9:1838, 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Easson and R. H. Brandenberger. Universe generation from black hole interiors. Journal of High Energy Physics, 2001, 2001. [CrossRef]

- E. Gaztanaga. The black hole universe, part i. Symmetry, 2022:1849, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Roupas. Detectable universes inside regular black holes. The European Physical Journal C, 82:255, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Siegel. Are we living in a baby universe that looks like a black hole to outsiders? Hard Science, Big Think, January 27, 2022. URL https://bigthink.com/hard-science/baby-universes-black-holes-dark-matter/.

- C. H. Lineweaver and V. M. Patel. All objects and some questions. American Journal of Physics, 91(819), 2023.

- E. T. Tatum and E. G. Haug. How the Haug-Tatum cosmological model entropic force can be directly linked to what is currently called “dark energy” . Unpublished paper submitted to journal, 2025. 2025.

- E. G. Haug and S. Wojnow. Application of the ideal gas law to the Hubble sphere leads to a new hubble sphere radiation pressure law. Cambridge engage, pre-print, 2025. URL https://www.cambridge.org/engage/coe/article-details/679c7c8dfa469535b987c3fb.

- E. G. Haug. CMB, Hawking, Planck, and Hubble scale relations consistent with recent quantization of general relativity theory. International Journal of Theoretical Physics, Nature-Springer, 63(57), 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. G. Haug and S. Wojnow. How to predict the temperature of the CMB directly using the Hubble parameter and the Planck scale using the Stefan-Boltzman law. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Physics, 12:3552, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Stefan J. Über die beziehung zwischen der wärmestrahlung und der temperatur. Sitzungsberichte der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Classe der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien, 79:391, 1879.

- L. Boltzmann. Ableitung des Stefanschen gesetzes, betreffend die abhängigkeit der wärmestrahlung von der temperatur aus der electromagnetischen lichttheori. Annalen der Physik und Chemie, 22:291, 1879.

- E. T. Tatum, U. V. S. Seshavatharam, and S. Lakshminarayana. The basics of flat space cosmology. International Journal of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 5:116, 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Muller et. al . A precise and accurate determination of the cosmic microwave background temperature at z=0.89. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 551, 2013. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Fixsen and et. al. The temperature of the cosmic microwave background at 10 Ghz. The Astrophysical Journal, 612:86, 2004. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Fixsen. The temperature of the cosmic microwave background. The Astrophysical Journal, 707:916, 2009. [CrossRef]

- P. Noterdaeme, P. Petitjean, R. Srianand, C . Ledoux, and S. López. The evolution of the cosmic microwave background temperature. Astronomy and Astrophysics, 526, 2011. [CrossRef]

- S. Dhal and R. K. Paul. Investigation on CMB monopole and dipole using blackbody radiation inversion. Scientific Reports, 13:3316, 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. G. Haug. Different mass definitions and their pluses and minuses related to gravity. Foundations, 3:199–219., 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. G. Haug. CMB, Hawking, Planck, and Hubble scale relations consistent with recent quantization of general relativity theory. International Journal of Theoretical Physics, 63(57), 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. G. Haug. Finding the Planck length multiplied by the speed of light without any knowledge of G, c, or h, using a newton force spring. Journal Physics Communication, 4:075001, 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. G. Haug. Planck units measured totally independently of big g. Open Journal of Microphysics, 12:55, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. G. Haug. Progress in the composite view of the Newton gravitational constant and its link to the Planck scale. Universe, 8(454), 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Milgrom. A modification of the Newtonian dynamics as a possible alternative to the hidden mass hypothesis. Astrophysical Journal., 270, 1983.

- M. Milgrom. Alternatives to dark matter. Comments on Astrophysics, 13:215, 1989.

- E. Verlinde. Emergent gravity and the dark universe. SciPost Phys., 2:016, 2017. [CrossRef]

- W. G. Unruh. Notes on black-hole evaporation. Physical Review D, 14(4), 1976.

- S. Hawking. Black hole explosions. Nature, 248, 1974. [CrossRef]

- E. G. Haug and E. T. Tatum. Solving the Hubble tension using the PantheonPlusSH0ES supernova database. Accepted and forthcoming Journal of Applied Mathematics and Physics, vol 13, no. 2, 2025.

- E. G. Haug. Closed form solution to the Hubble tension based on Rh=ct cosmology for generalized cosmological redshift scaling of the form: z=(rh/rt)x-1 tested against the full distance ladder of observed SN ia redshift. Preprints.org, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Lloyd. Ultimate physical limits to computation. Nature, 406:1047–1054, 2000.

- E. G. Haug. The Planck computer is the quantum gravity computer: We live inside a gigantic computer, the Hubble sphere computer? Quantum Reports, 6:482, 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).