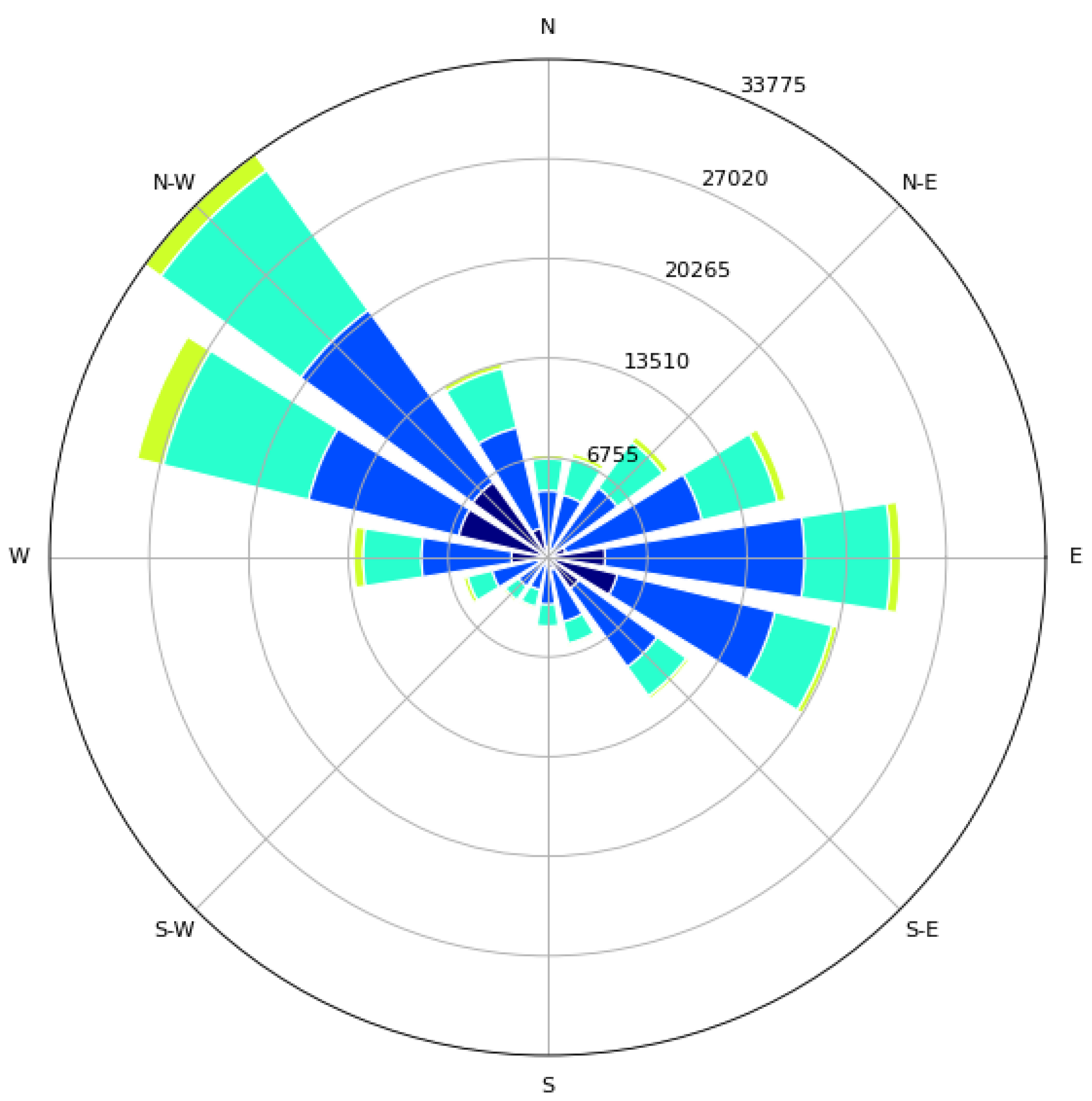

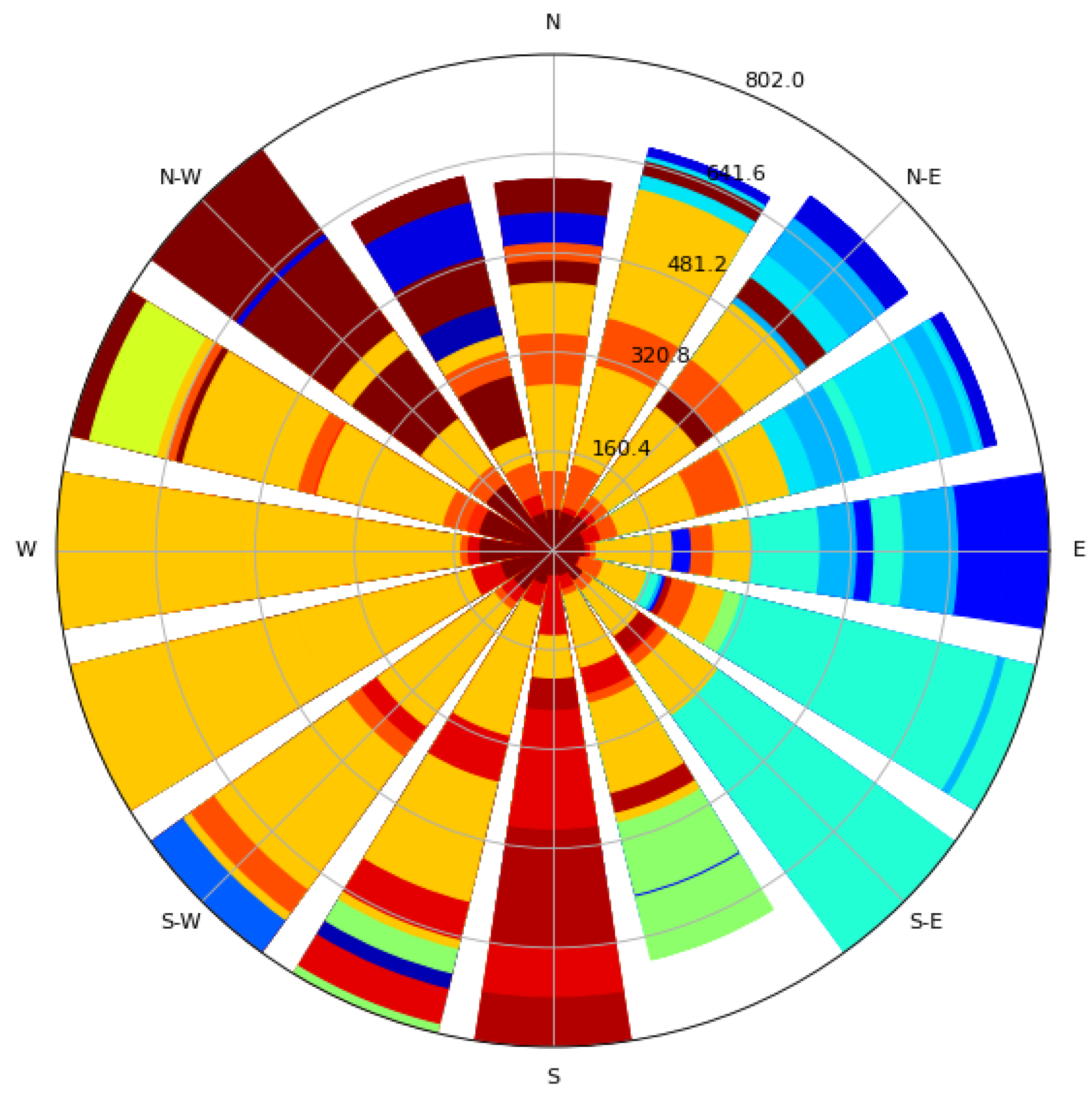

3.14. Wind Direction of the Joya de los Sachas Canton

Between 1998 and 2003, the wind direction during the first month varied between 120° and 190°. From May to August, the direction consistently stayed between 220° and 240°, shifting to between 120° and 210° from October to December. During the 2004-2009 period, changes in wind direction are noticeable. A significant shift is seen in 2008, with the direction consistently at 240° from June until early October. In 2005, the wind direction remained remarkably stable between 140° and 160° throughout the year. 2007 saw a change in direction, varying from 150° to 190° (see

Figure 31)

In 2010, the wind direction showed more rapid fluctuations, varying between 170° and 200°. In subsequent years, the directions started to stabilize, generally ranging from 220° to 240° from June to September. Between 2016 and 2021, and specifically in 2018, the wind direction began at 210°, contrasting with the other years, which started between 140° and 180°. This pattern highlights a distinct behavior in 2018 compared to other years in the period.

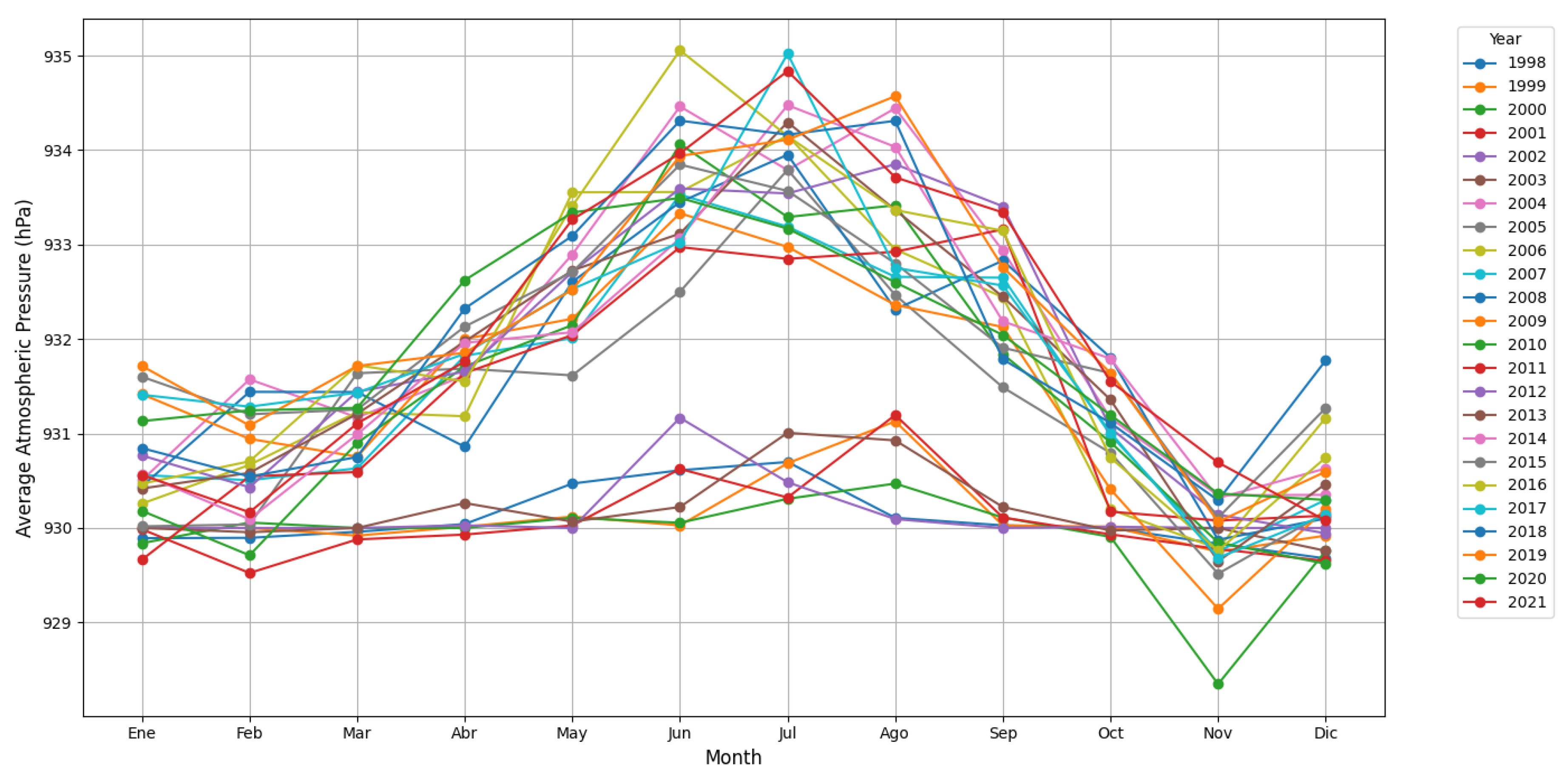

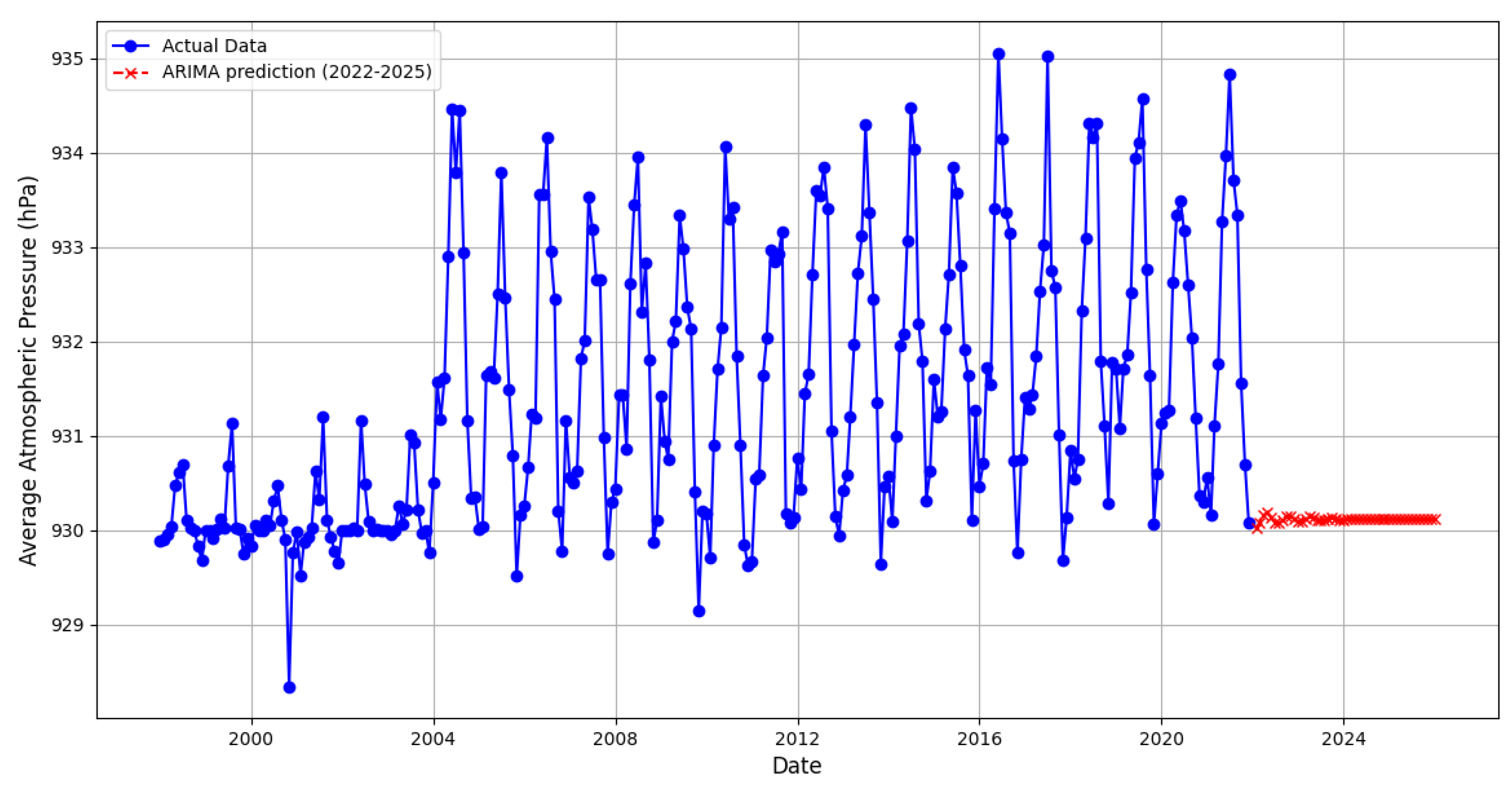

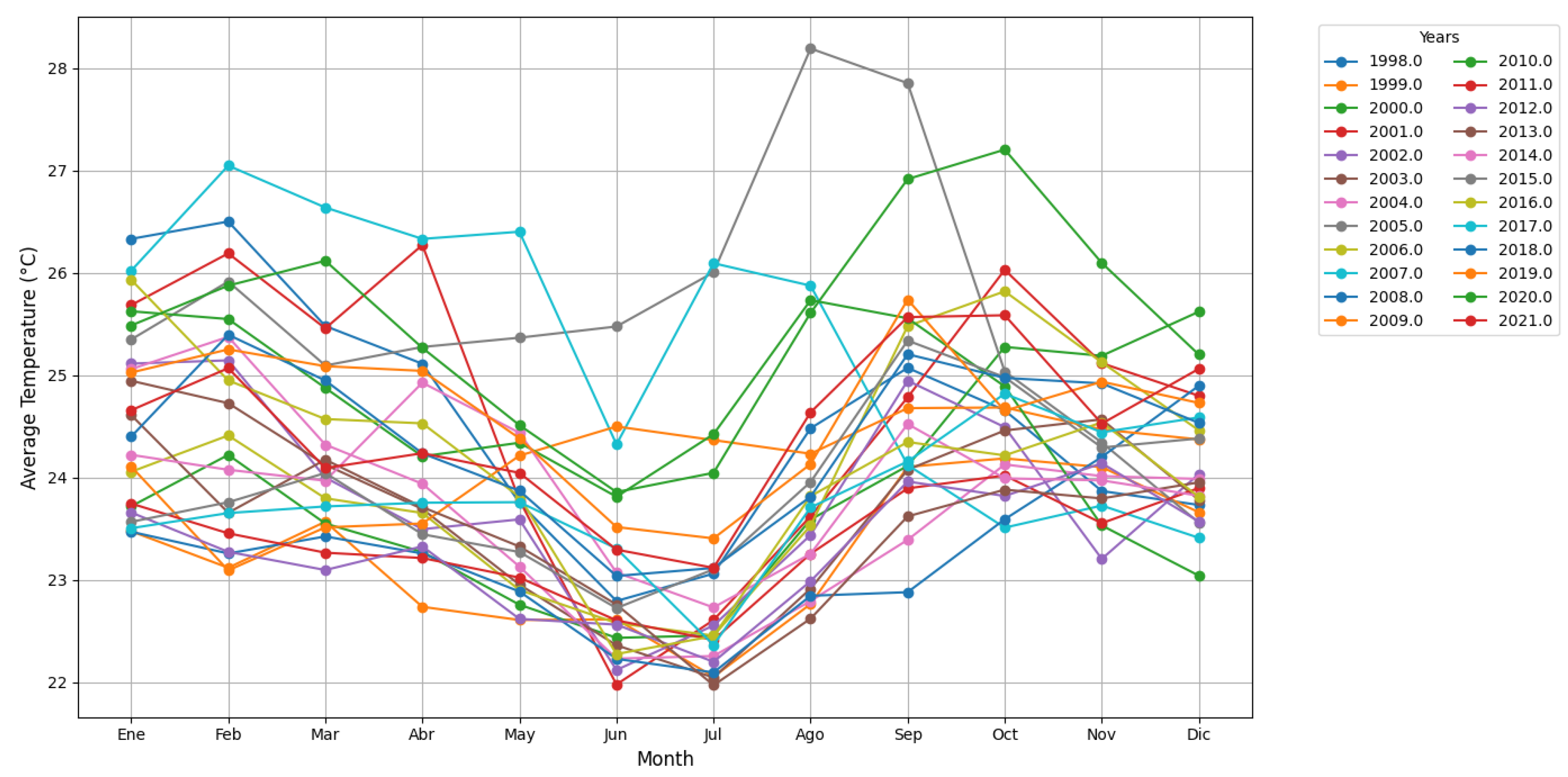

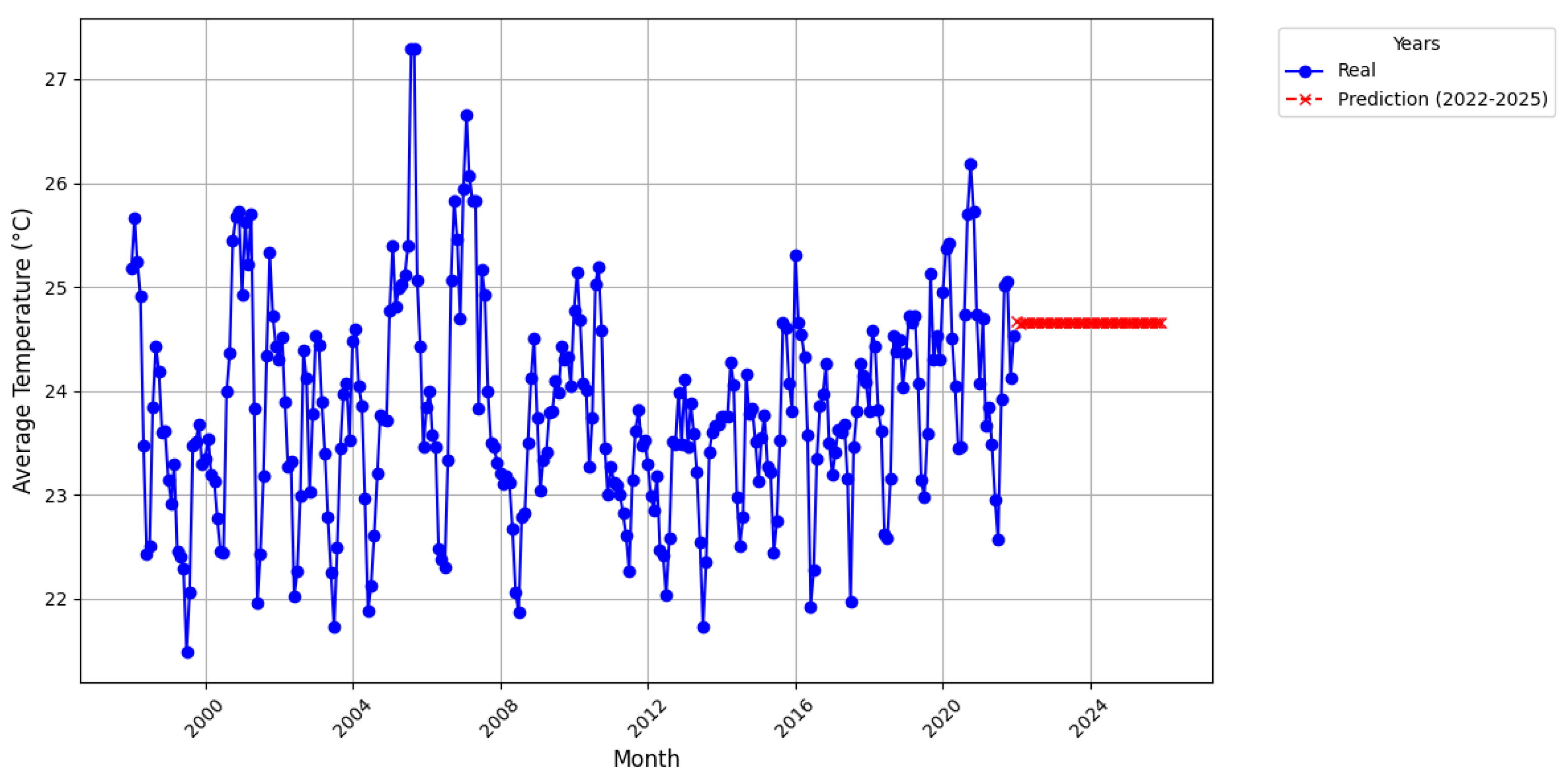

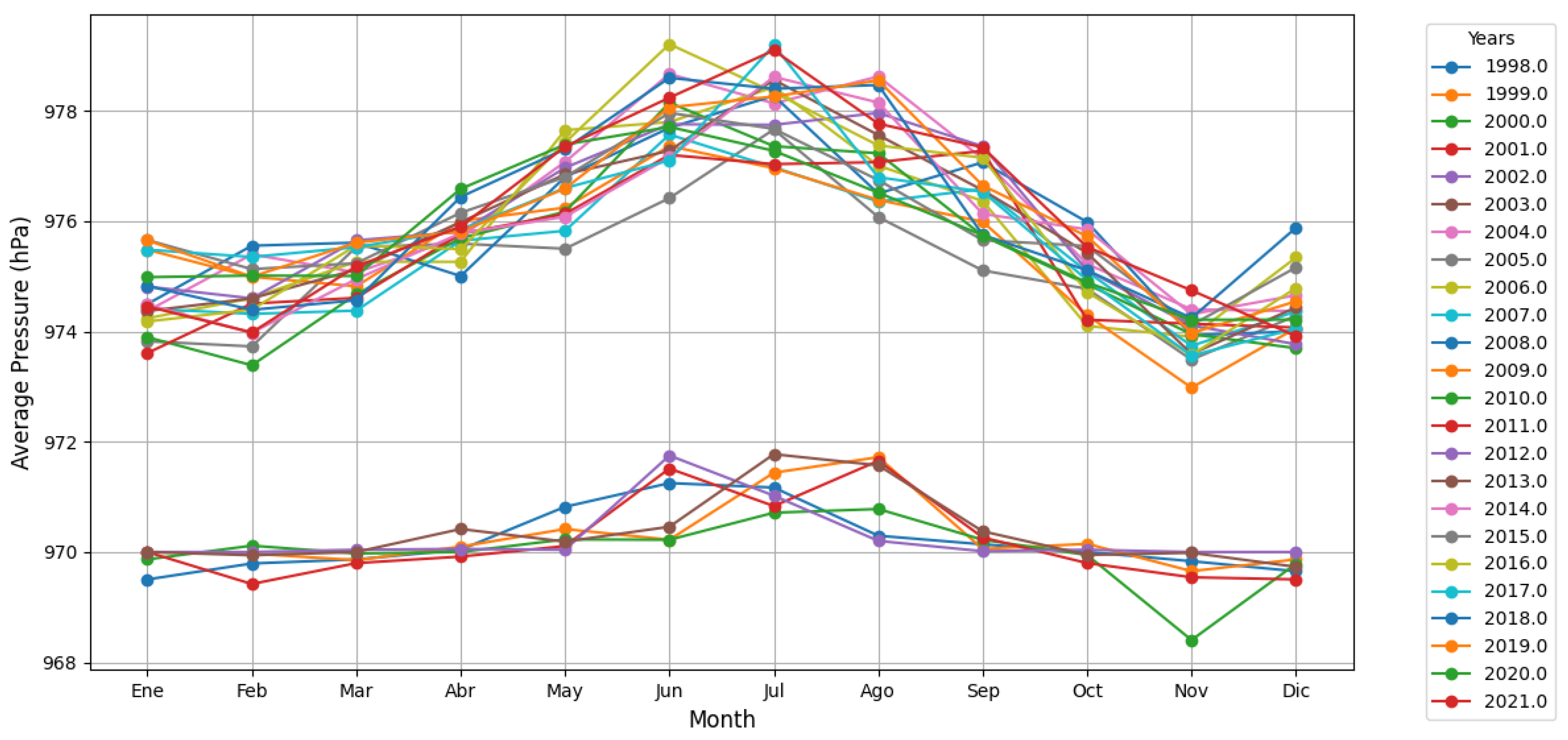

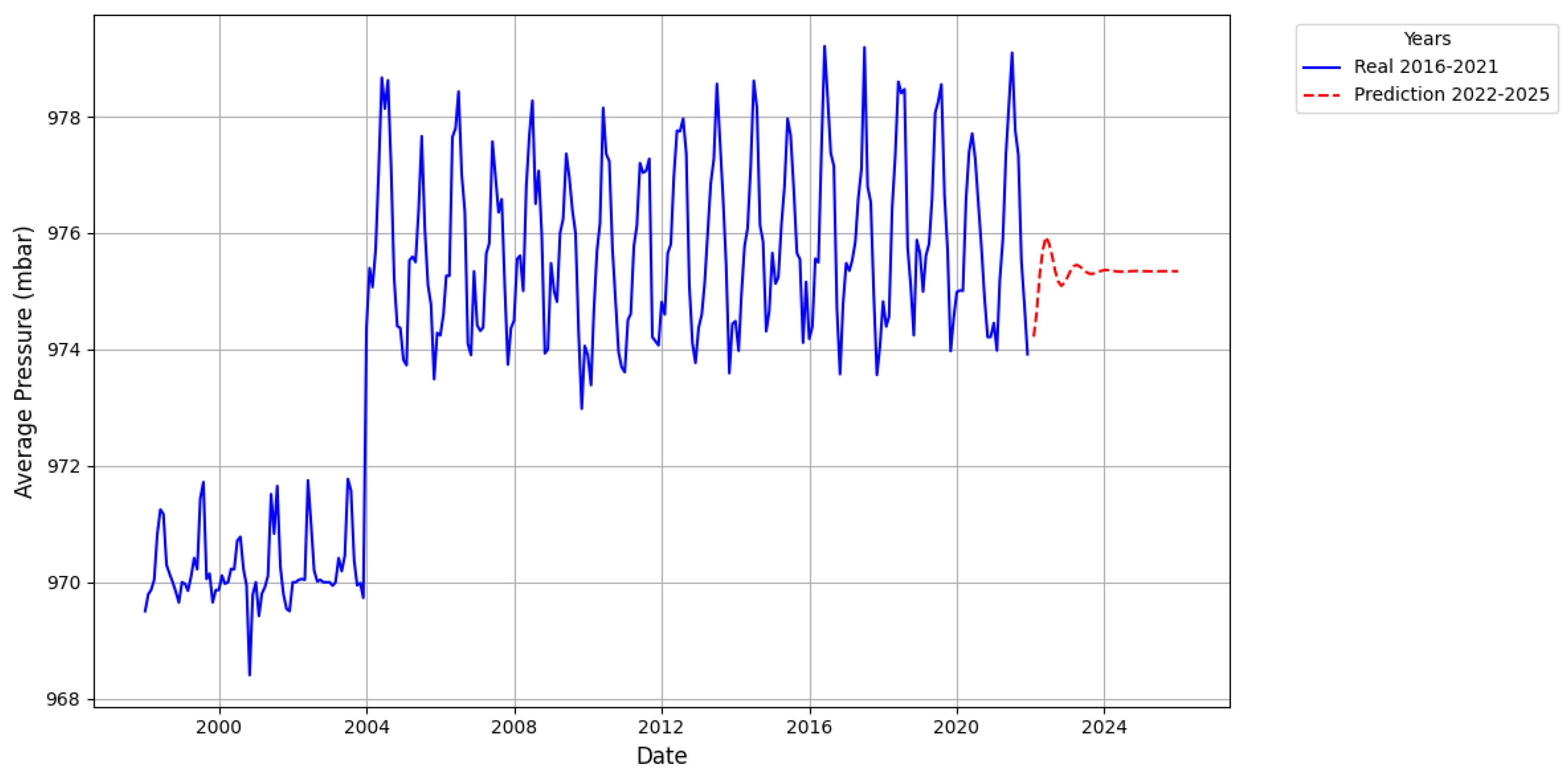

With regard to temperature, it is observed that El Sacha exhibits higher values than Loreto throughout all analyzed periods. Specifically, during the 2016-2021 period, El Sacha attains a maximum temperature of 24.5 °C, exceeding that recorded in Loreto. Concerning atmospheric pressure, this is likewise higher in El Sacha in comparison to Loreto. During the period spanning 2016 to 2021, El Sacha registers a maximum value of 976.0 mbar, which demonstrates a significant difference in the atmospheric conditions between the two localities (see

Table 7).

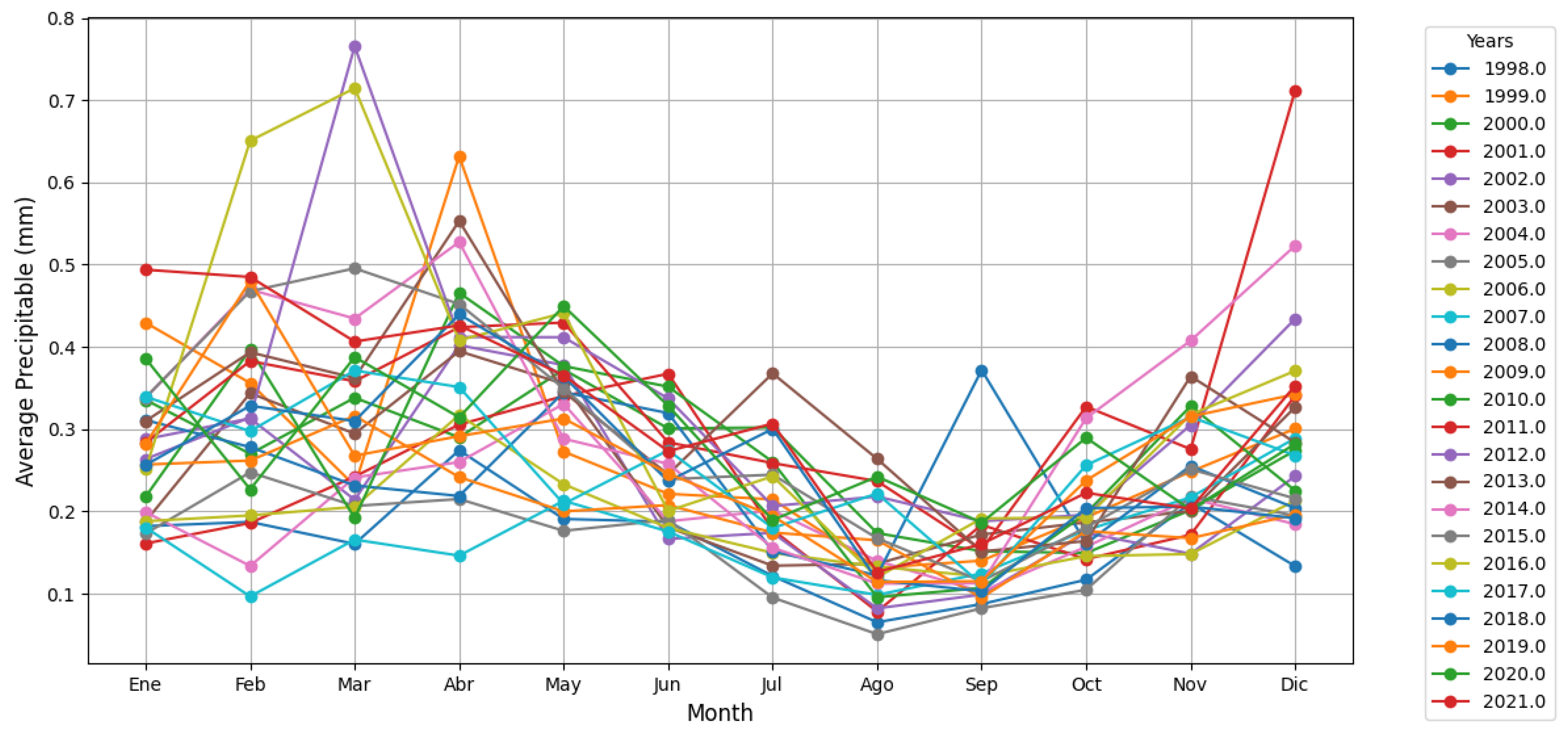

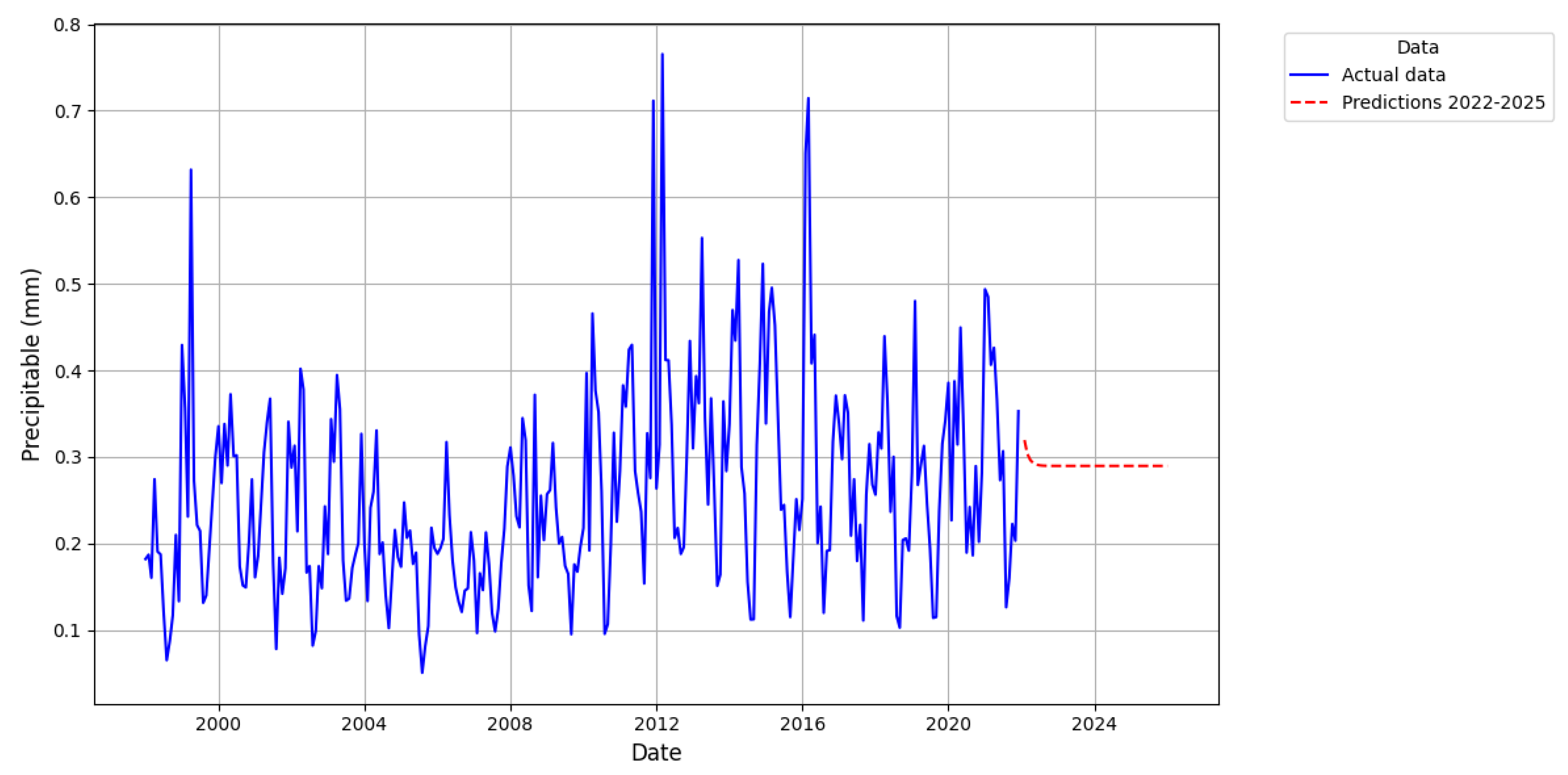

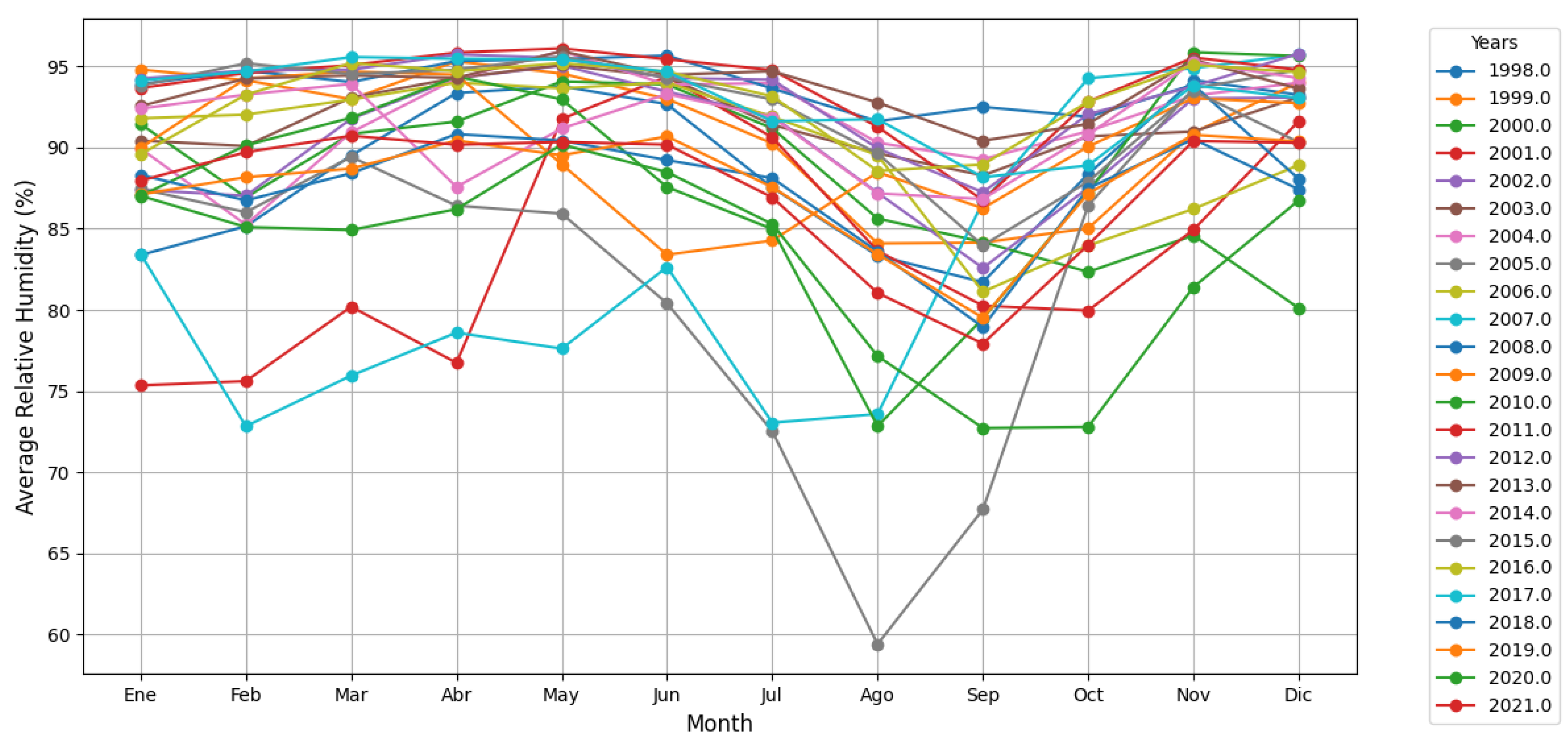

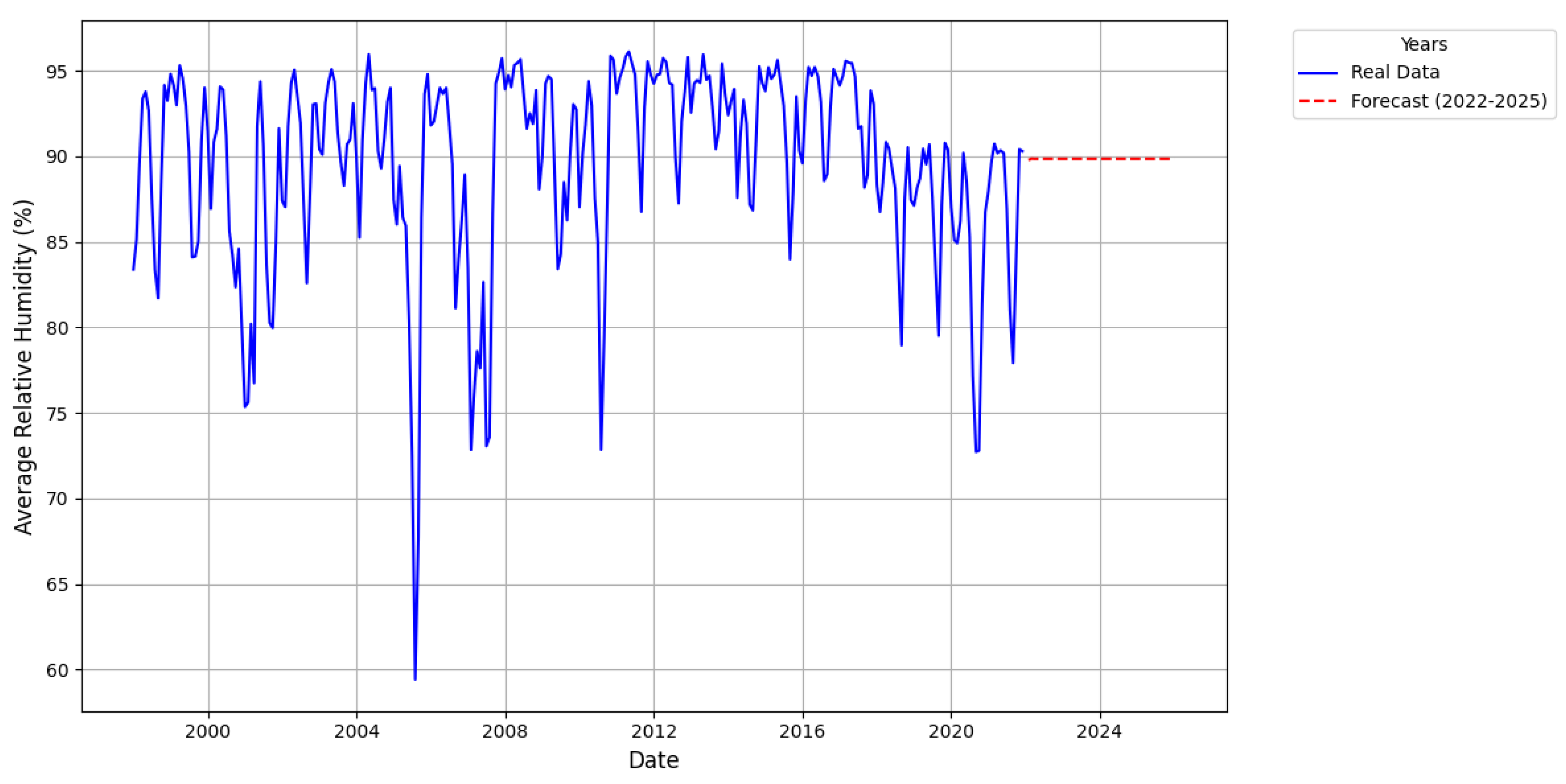

With regard to precipitation, it is observed that El Sacha exhibits a greater quantity of precipitation in comparison to Loreto throughout the majority of the analyzed periods. The period spanning 2010-2015 in El Sacha is particularly noteworthy, registering a value of 0.314 mm. Conversely, relative humidity is significantly elevated in El Sacha relative to Loreto. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced during the 2010-2015 period in El Sacha, with a recorded value of 92.2%. In contrast, Loreto registers its nadir in relative humidity during the 2016-2021 period, with a value of 85.6% (see

Table 10).

Table 9.

Temperature (°C) and Atmospheric Pressure (mbr)

Table 9.

Temperature (°C) and Atmospheric Pressure (mbr)

| Interaction effect |

Temperature (°C) |

Interaction effect |

Pressure(mbr) |

| Loreto (2010-2015) |

23.5 ± 1.01 a |

Loreto (1998-2003) |

930.1 ± 0.88 a |

| Loreto (1998-2003) |

23.7 ± 1.32 b |

Loreto (2004-2009) |

931.6 ± 1.78 b |

| El Sacha (2010-2015) |

23.8 ± 1.11 b |

Loreto (2010-2015) |

931.7 ± 1.79 b |

| El Sacha (1998-2003) |

24.0 ± 1.41 c |

Loreto (2016-2021) |

932.0 ± 1.85 c |

| Loreto (2016-2021) |

24.0 ± 1.10 c |

El Sacha (1998-2003) |

970.2 ± 1.19 d |

| Loreto (2004-2009) |

24.1 ± 1.42 c |

El Sacha (2004-2009) |

975.6 ± 1.88 e |

| El Sacha (2004-2009) |

24.3 ± 1.55 d |

El Sacha (2010-2015) |

975.7 ± 1.88 e |

| El Sacha (2016-2021) |

24.5 ± 1.23 e |

El Sacha (2016-2021) |

976.0 ± 1.97 f |

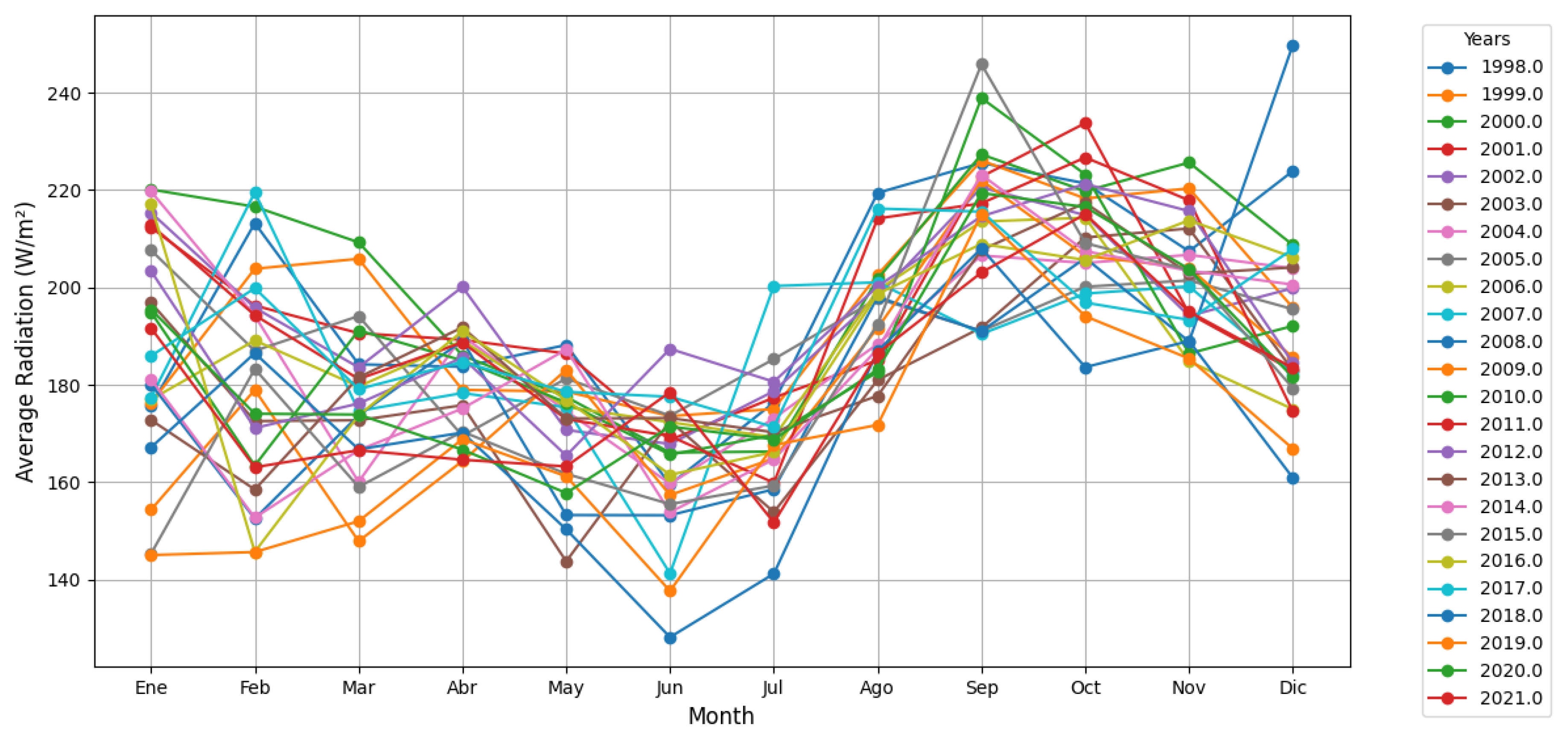

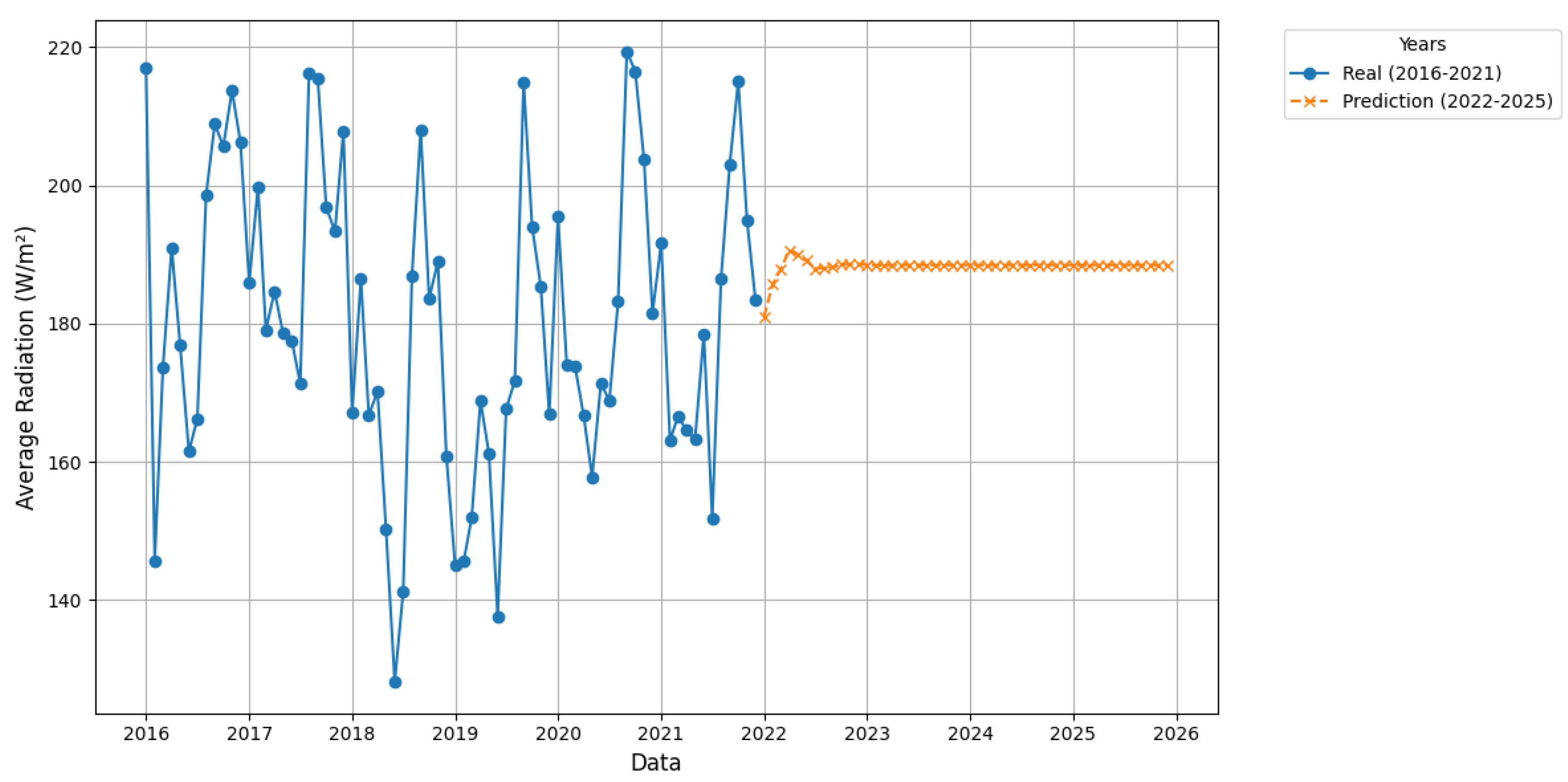

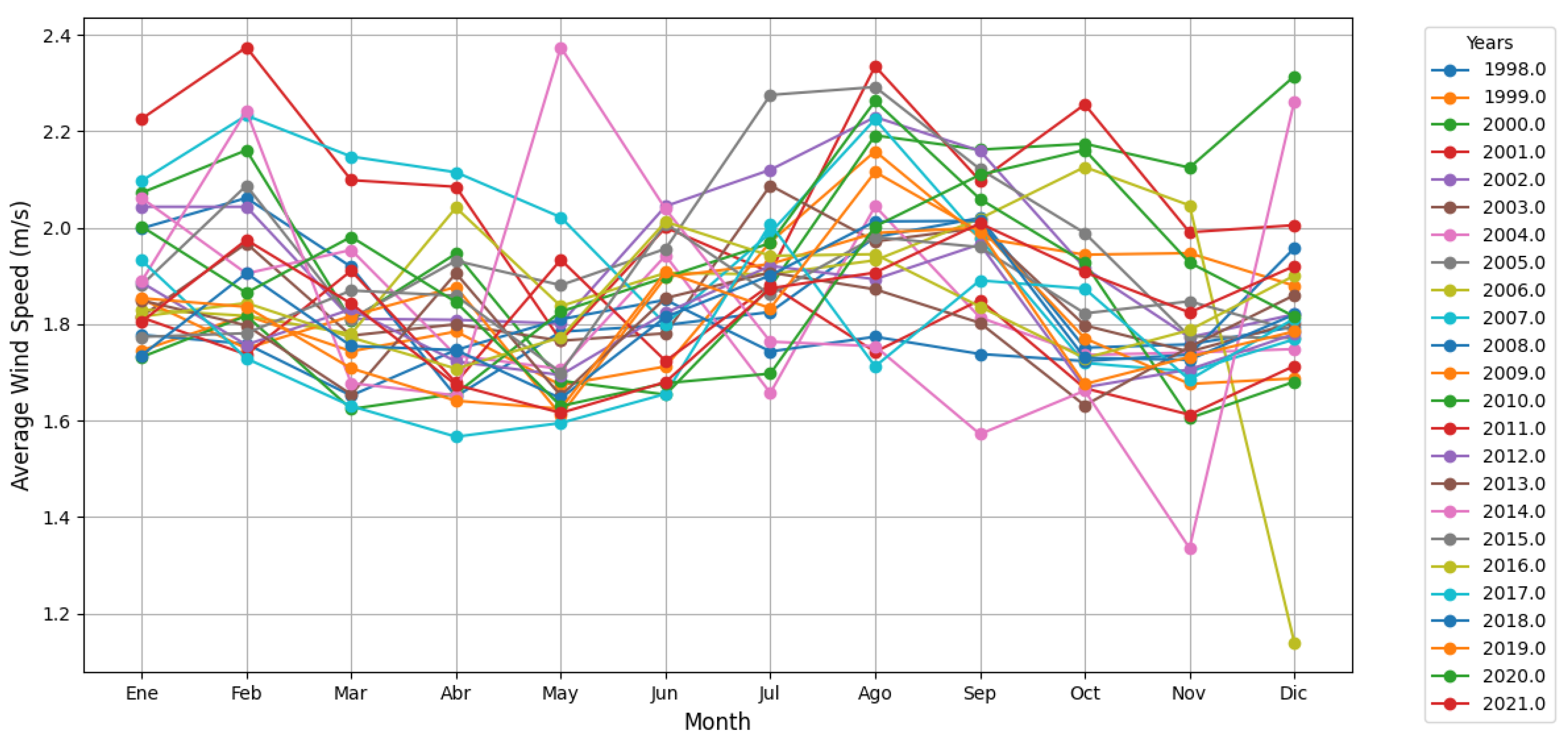

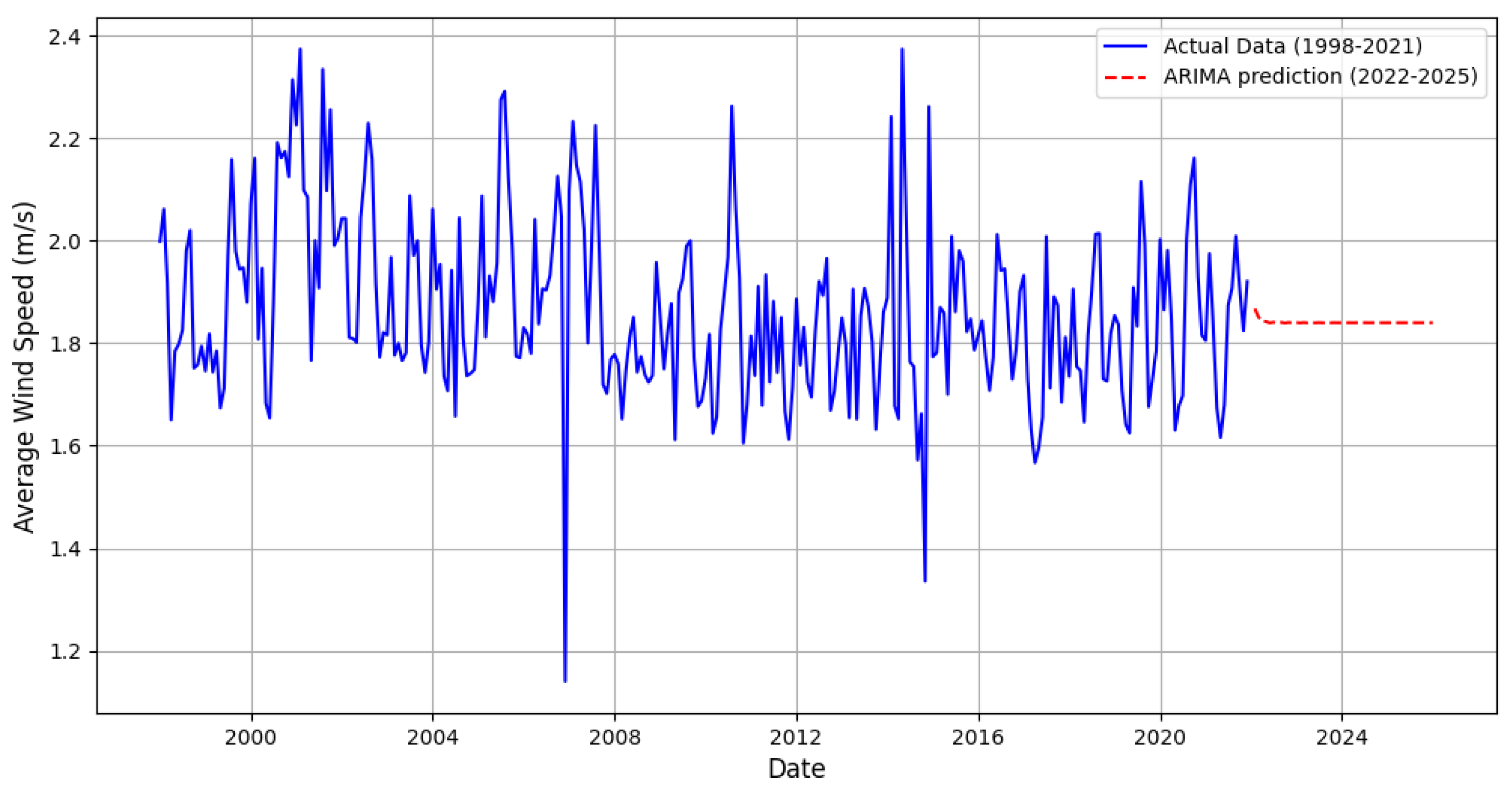

Solar radiation in the Loreto region exhibits elevated levels in comparison to El Sacha, particularly noteworthy between 1998 and 2003, with a mean value of 391.7 W/m². This phenomenon signifies a greater intensity of radiation in Loreto during the aforementioned period. With respect to wind speed, a similar tendency is likewise observed, with higher values recorded in Loreto, reaching up to 2.53 m/s between 1998 and 2003. Conversely, wind speeds in El Sacha are lower, with a maximum of 1.94 m/s within the same temporal interval. These data reflect a significant disparity in the climatic conditions of both zones, which may have implications for renewable energy analyses and other meteorological investigations (see

Table 9).

Wind direction exhibits greater variability at the Loreto station, where a range of 200.1° was observed during the period from 2010 to 2015. Conversely, at El Sacha, the wind direction demonstrates greater consistency, with a range fluctuating between 181.9° and 197.2°. This disparity suggests that, whereas Loreto experiences more pronounced fluctuations in wind orientation, El Sacha presents more stable conditions in this respect (see

Table 12)

The soil pH in Loreto and Sachas is within the optimal range for the growth of most plant species. However, Loreto exhibits a slightly lower pH value in comparison to Sachas, although both values are conducive to plant development. With respect to NH4 (ammonium) concentrations, both soils are within the optimal range; however, Sachas demonstrates a higher ammonium concentration, which may be advantageous for plant growth, as ammonium serves as a significant nitrogen source.

With regard to phosphorus (P), Loreto demonstrates a deficient level, below the established optimal range, which may potentially limit plant growth in this area. Conversely, Sachas exhibits an adequate value for vegetative development. Potassium (K) concentrations are low in Loreto, which may restrict plant nutrition, whereas Sachas exhibits a higher concentration, albeit still outside the optimal range.

Concerning calcium (Ca) and magnesium (Mg), it is observed that Loreto’s soil possesses an insufficient calcium concentration, which may negatively impact plant health, while Sachas presents a more suitable value. With respect to magnesium, Loreto exhibits a slightly low value, although within the optimal range, whereas Sachas presents adequate concentrations. Furthermore, both soils exhibit low sulfur (S) concentrations, with the deficiency being more pronounced in Loreto, which may influence plant growth if these concentrations persist.

Micronutrient concentrations such as zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), iron (Fe), and manganese (Mn) are generally within optimal ranges in both soils. However, in Loreto, elevated iron and manganese concentrations are observed relative to Sachas, which may have implications for the uptake of these elements by plants. Finally, boron (B) concentrations are low in both samples, which may limit the efficacy of certain metabolic processes in plants.

With regard to organic matter (OM), Sachas is notable for possessing a significantly higher concentration compared to Loreto, which indicates a superior nutrient content and enhanced soil fertility (see

Table 13)

With respect to the Al + H and Al (Aluminum + Hydrogen and Aluminum) parameters, both values are within the appropriate ranges for the soils under investigation, suggesting an optimal equilibrium of acidity and toxicity in both instances.

Conversely, the relationship between Ca/Mg, Mg/K, and (Ca+Mg)/K exhibits significant disparities between the Sachas and Loreto soils. The Sachas soil demonstrates a more balanced calcium-to-magnesium ratio, which is conducive to its stability. In contrast, in the Loreto soil, this ratio is less balanced, which could engender a less propitious environment for plant development.

Finally, upon analysis of the Exchangeable Bases, Sand, Silt, Clay fractions, and the soil texture classification, it is observed that the Loreto soil possesses a higher clay content, thus classifying it as a heavier soil. Conversely, the Sachas soil exhibits a greater silt content, indicative of a lighter texture, which consequently enhances aeration and water drainage, fundamental characteristics for optimal soil health (see

Table 14).

The parameters of samples N9FL1, N10FL2, and N11FL3 fall within the permissible ranges for the majority of analyzed elements, including pH, electrical conductivity (EC), and nitrites. Nevertheless, certain exceptions have been identified, notably in the values corresponding to lead and fluoride, which do not attain the optimal levels stipulated according to quality criteria. This finding indicates the necessity of a more comprehensive review of these parameters to ensure conformity with environmental standards.

The values of pH, electrical conductivity (EC), and other key parameters are typically observed to fall within the permissible ranges stipulated by water quality regulations, indicating that the majority of water samples meet the minimum safety and health requirements for human consumption and other applications. These parameters are essential for assessing water suitability in terms of its acidity or alkalinity, electrical conductivity (which reflects the concentration of dissolved ionic species), as well as other factors that exert a direct impact on public health and industrial processes.

Notwithstanding this, certain samples exhibit elevated concentrations of lead and fluoride, which do not conform to the standards prescribed by quality regulations. Lead, even at low concentrations, can elicit significant toxic effects on human health, particularly in children and pregnant women, by impairing neurological development and inducing neurological disorders. Concurrently, fluoride, while demonstrating beneficial effects at low concentrations for dental health, can prove detrimental when present at elevated levels, predisposing individuals to conditions such as dental and skeletal fluorosis. These non-permissible values constitute a cause for concern, underscoring the necessity for continuous monitoring and, potentially, the implementation of remedial measures to mitigate these contaminants to safe concentrations.

The results derived from the analysis of water samples intended for human consumption and domestic use are essential for evaluating the quality of water available across diverse regions. The presented tables furnish a detailed analysis of the various samples, thereby enabling a clear comprehension of the status of key parameters in relation to the limits stipulated by sanitary and environmental regulations. This analysis not only facilitates the identification of parameters that adhere to established quality standards but also underscores those that fail to attain permissible levels, thus necessitating immediate intervention.

The presence of impermissible constituents, such as lead, fluoride, or other compounds present in excessive concentrations, may engender grave consequences for human health. In this context, protracted exposure to contaminants such as lead can induce damage to vital organs, while excessive fluoride can exert deleterious effects on skeletal and dental health. Consequently, intervention aimed at ameliorating water quality is not merely a technical consideration but rather an urgent imperative to forestall public health exigencies.

This type of exhaustive analysis is of paramount importance in ensuring continuous access to potable and safe water, a resource indispensable for human life and well-being. Furthermore, water quality exerts a direct influence on the prevention of waterborne illnesses, such as diarrheal diseases, which constitute a primary cause of morbidity and mortality in numerous regions globally. The availability of clean and safe water is inextricably linked to public health and quality of life, as it influences hygiene practices, food security, and the overall development of communities.

Likewise, a meticulous analysis contributes to the sustainability of water resources, which is of particular relevance within a context characterized by water scarcity and escalating pollution. Preserving water quality and guaranteeing its equitable distribution are endeavors that necessitate long-term strategic planning and the implementation of robust protection, treatment, and conservation measures (see

Table 15).

Moreover, these analyses furnish those responsible for water management and public health with a critical instrument for informed decision-making. Precise information pertaining to water quality facilitates the formulation of appropriate policies, the identification of problematic locales, and the development of action plans for water treatment and purification. This encompasses the enhancement of distribution infrastructures, the adoption of advanced purification technologies, and the education of communities in appropriate water stewardship practices.

The parameters observed in samples N9FL1, N10FL2, and N11FL3 conform to the quality criteria stipulated for water intended for agricultural irrigation. Initially, the values of pH and electrical conductivity (EC), in conjunction with the sulfate concentration, are within the permissible limits defined for agricultural utilization. Moreover, the concentrations of heavy metals, including arsenic, iron, and chromium, are also within acceptable ranges.

These findings indicate that the physicochemical characteristics of the water under consideration are suitable for agricultural use, presenting no risk to crop production. The analyzed results of water samples obtained in Loreto (N9FV1, N10FV2, and N11FV3) reveal that all key water quality parameters comply with the established criteria for their use in agriculture and irrigation, according to international and local regulations.

Regarding pH, all samples remained within the optimal range for agricultural use, established between 6.5 and 8.5. The obtained values were 6.77, 7.14, and 6.65, respectively, which ensures the water’s suitability to guarantee that nutrients are accessible to plants, without risk of toxicity.

In terms of electrical conductivity (EC), which indicates the concentration of soluble salts in the water, the values were 47.63, 19.7, and 33.46, all within the permitted limits. This ensures that the water does not present a high concentration of salts, preventing potential salinity problems that could negatively affect crop growth.

Sulfate levels in the Loreto samples were 45, 54, and 41 mg/L, values significantly below the permissible limit of 250 mg/L. This indicates a low sulfate concentration in the water, which favors nutrient absorption by plants and eliminates the risk of toxicity.

Regarding heavy metals, such as arsenic, iron, chromium, copper, lead, and cadmium, it was observed that all levels remained below the established limits. Arsenic values were 0.016, 0.014, and 0.012 mg/L, well below the permissible limit of 0.1 mg/L. Iron levels were 0.24, 0.8, and 0.85 mg/L, all within the permitted limit of 5 mg/L. Furthermore, no levels of cadmium or lead were detected in the samples, which confirms the absence of risks associated with these toxic metals. Regarding chromium and copper, the values were 0.023, 0.04, and 0.5 for chromium, and 0.12, 0.18, and 0.18 for copper, which remained within acceptable levels, supporting the water’s safety in relation to heavy metals.

Finally, nitrite levels, which can be harmful in high concentrations, remained at low values. Nitrite concentrations were 0.1, 0.052, and 0.005 mg/L, all below the permissible limit of 0.5 mg/L, eliminating any risk of nitrite toxicity in the water intended for irrigation (see

Table 16).

The results presented in the table indicate that all water parameters for irrigation in the Sacha sample conform to the permissible levels stipulated by the established quality criteria. Nonetheless, certain exceptions were identified wherein the values of some parameters approach the upper threshold of the permitted standards. Specifically, the pH in sample C11FL3 exhibited a value of 9.05, while the electrical conductivity (EC) in the same sample registered 198. These values, albeit within the established limits, necessitate continuous monitoring, as their exceedance could engender adverse effects on the agricultural utilization of the water, thereby altering the optimal conditions for irrigation.

The results largely adhere to the quality criteria established for agricultural water utilization, as evidenced by the analyzed parameters. The reported values are, in general terms, within the prescribed limits, thereby suggesting that the water may be employed safely for agricultural irrigation without presenting an immediate hazard to crops or soil. This finding is of considerable importance in regions where water quality may undergo significant variations due to factors of either natural or anthropogenic origin.

Notwithstanding, a singular instance was identified in sample C11FP3, wherein the copper content attained a value of 13, substantially exceeding the permissible limit of 0.2 stipulated by current regulatory frameworks. This elevated concentration constitutes a potential hazard to soil and plant health, inasmuch as excessive copper concentrations may engender toxicity in crops, negatively impact edaphic biodiversity, and, in the long term, alter the physicochemical properties of agricultural soil. Furthermore, the bioaccumulation of this metal could potentially culminate in adverse effects within the food chain should appropriate control measures not be implemented (see

Table 17).

In this context, it is deemed a priority to institute more detailed and periodic monitoring of the copper concentration in irrigation water within this specific area. Furthermore, it would be pertinent to investigate the potential sources of contamination, which may encompass proximate industrial activities, the utilization of pesticides or fertilizers with elevated copper content, or even natural contributions originating from the soil or subsoil. Should the need arise, remedial measures, such as filtration systems or chemical treatments, could be implemented to mitigate copper concentrations within the water prior to its utilization in agricultural activities. These actions would serve to ensure the sustainability of agricultural practices and the preservation of ecosystem health in its entirety (see

Table 18).