Submitted:

10 February 2025

Posted:

11 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Methodological Approaches to Studying Childhood Violence and Adverse Childhood Experiences

1.2. Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire

1.3. Study Objective

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Ad-hoc sociodemographic survey

2.3.2. Adverse Childhood Experiences Abuse Short Form (ACE-ASF)

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Statistical analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Reliability

4.2. Validity

4.3. Measurement Invariance

4.4. Comparisons with the ACE-IQ

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACE | Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire |

| ACE-ASF | Adverse Childhood Experiences Abuse Short Form |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| HTMT | Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio |

| CR | Composite Reliability |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

| CFI | Comparative ft index |

| TLI: | Tucker-Lewis Index |

| GFI | Goodness of Fit Index |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Estimate | λ2 | λ6 | GLB | AIC | Mean | SD | |

| Total | Point estimate | 0.835 | 0.867 | 0.906 | 0.376 | 19.831 | 4.741 |

| (A1 - A8) | 95% CI lower bound | 0.813 | 0.844 | 0.890 | 0.332 | 19.510 | 4.524 |

| 95% CI upper bound | 0.854 | 0.887 | 0.921 | 0.416 | 20.152 | 4.979 | |

| F1 | Point estimate | 0.826 | 0.788 | 0.860 | 0.540 | 11.308 | 3.527 |

| (A1 - A4) | 95% CI lower bound | 0.803 | 0.763 | 0.837 | 0.501 | 11.070 | 3.366 |

| 95% CI upper bound | 0.845 | 0.811 | 0.880 | 0.573 | 11.547 | 3.704 | |

| F1 | Point estimate | 0.869 | 0.853 | 0.914 | 0.633 | 8.523 | 2.234 |

| (A5 - A8) | 95% CI lower bound | 0.834 | 0.814 | 0.885 | 0.565 | 8.372 | 2.132 |

| 95% CI upper bound | 0.898 | 0.888 | 0.937 | 0.697 | 8.674 | 2.346 |

Appendix A.2

| General | Man | Woman | ||||

| KMO | R² | KMO | R² | KMO | R² | |

| A1 | 0.818 | 0.499 | 0.816 | 0.513 | 0.813 | 0.483 |

| A2 | 0.865 | 0.496 | 0.841 | 0.504 | 0.872 | 0.474 |

| A3 | 0.771 | 0.692 | 0.773 | 0.709 | 0.775 | 0.684 |

| A4 | 0.830 | 0.497 | 0.821 | 0.515 | 0.845 | 0.484 |

| A5 | 0.815 | 0.736 | 0.802 | 0.537 | 0.811 | 0.782 |

| A6 | 0.834 | 0.648 | 0.795 | 0.453 | 0.833 | 0.719 |

| A7 | 0.788 | 0.666 | 0.751 | 0.559 | 0.798 | 0.797 |

| A8 | 0.768 | 0.427 | 0.736 | 0.317 | 0.771 | 0.590 |

| Overall | 0.808 | 0.792 | 0.810 | |||

| Bartlett's test of sphericity | ||||||

| Χ² | 3.099.719 | 1.242.090 | 1.729.997 | |||

| df | 28 | 28 | 28 | |||

| p | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | |||

References

- Ferrara, P.; Cammisa, I.; Zona, M.; Corsello, G.; Giardino, I.; Vural, M.; Pettoello-Mantovani, M. The global issue of violence toward children in the context of war. J. Pediatr. 2024, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillis, S.; Mercy, J.; Amobi, A.; Kress, H. Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: A systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics 2016, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.P. Preventing violence against children and youth. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2024, 45, 363–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Pasha, S.A.; Cox, A.; Youssef, E. Examining the short and long-term impacts of child sexual abuse: a review study. SN Soc. Sci. 2024, 4, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, A.; Maas, M.K.; Mark, K.P.; Kussainov, N.; Schill, K.; Coker, A.L. The impacts of lifetime violence on women's current sexual health. Women's Health Rep. 2024, 5, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, A.; Berry, M.; Fernandez-Pineda, M.; Haberstroh, A. An Integrative Review of Adverse Childhood Experiences and Reproductive Traumas of Infertility and Pregnancy Loss. J. Midwifery Women's Health 2024, 69, 258–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhutta, Z.A.; Bhavnani, S.; Betancourt, T.S.; Tomlinson, M.; Patel, V. Adverse childhood experiences and lifelong health. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1639–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, G.; Shu, L.; Liu, H.; Ma, S.; Han, T.; Zhang, H.; Huang, C.; Wang, J.; Yang, L.; Sun, Y. Association Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Academic Performance Among Children and Adolescents: A Global Meta-Analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2024, 25, 3332–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horino, M.; Abu-Rmeileh, N.M.E.; Yang, W.; Albaik, S.; Al-Khatib, L.; Seita, A. Exploring the link between adverse childhood experiences and mental and physical health conditions in pregnant Palestine refugee women in Jordan. Public Health 2023, 220, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewkes, R.; Dunkle, K.; Nduna, M.; Jama, P.N.; Puren, A. Associations between childhood adversity and depression: Substance abuse and HIV and HSV2 incident infections in rural South African youth. Child Abuse Negl. 2010, 34, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinck, F.; Woollett, N.; Franchino-Olsen, H.; Silima, M.; Thurston, C.; Fouché, A.; Christofides, N. Interrupting the intergenerational cycle of violence: protocol for a three-generational longitudinal mixed-methods study in South Africa (INTERRUPT_VIOLENCE). BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.E.; Chen, E.; Parker, K.J. Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: Moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 959–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramiro, L.S.; Madrid, B.J.; Brown, D.W. Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) and health-risk behaviors among adults in a developing country setting. Child Abuse Negl. 2010, 34, 842–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansone, A.; Limoncin, E.; Colonnello, E.; Mollaioli, D.; Ciocca, G.; Corona, G.; Jannini, E.A. Harm reduction in sexual medicine: How to manage patients with sexual dysfunction caused by substance use. Sexual Med. Rev. 2024, 12, 422–429. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, N.; Quigg, Z.; Bellis, M.A. Cycles of violence in England and Wales: the contribution of childhood abuse to risk of violence revictimisation in adulthood. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrenkohl, T.I.; Fedina, L.; Roberto, K.A.; Raquet, K.L.; Hu, R.X.; Rousson, A.N.; Mason, W.A. Child Maltreatment, Youth Violence, Intimate Partner Violence, and Elder Mistreatment: A Review and Theoretical Analysis of Research on Violence Across the Life Course. Trauma Violence Abus. 2022, 23, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, C.; Langevin, R.; Cabecinha-Alati, S. Victim-to-victim intergenerational cycles of child maltreatment: A systematic scoping review of theoretical frameworks. Int. J. Child Adolesc. Resil. 2022, 9, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, M.; Tonmyr, L.; Hovdestad, W.E.; Gonzalez, A.; MacMillan, H. Exposure to family violence from childhood to adulthood. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May-Chahal, C.; Cawson, P. Measuring Child Maltreatment in the United Kingdom: A Study of the Prevalence of Child Abuse and Neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect 2005, 29, 969–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May-Chahal, C.; Bertotti, T.; Di Blasio, P.A.C.M.; Cerezo, M.A.; Gerard, M.; Grevot, A.; Al-Hamad, A. Child Maltreatment in the Family: A European Perspective. European Journal of Social Work 2006, 9, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, D.; McCoy, A.; Swales, D. The Consequences of Maltreatment on Children’s Lives: A Systematic Review of Data From the East Asia and Pacific Region. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 2012, 13, 209–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinck, F.; Steinert, J.; Sethi, D.; Gilbert, R.; Bellis, M.; Alink, L.; Baban, A. Measuring and Monitoring National Prevalence of Child Maltreatment: A Practical Handbook; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:d119ecfc-cd5e-45bc-8cde-13fabdfa982a/files/m580e1cc881179236acc5ba604fd6def9.

- Steele, B.; Neelakantan, L.; Jochim, J.; Davies, L.M.; Boyes, M.; Franchino-Olsen, H.; Dunne, M.; Meinck, F. Measuring Violence Against Children: A COSMIN Systematic Review of the Psychometric and Administrative Properties of Adult Retrospective Self-report Instruments on Child Abuse and Neglect. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 2024, 25, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinck, F.; Murray, A.L.; Dunne, M.P.; Schmidt, P.; Nikolaidis, G.; Petroulaki, K.; Browne, K. Measuring Violence Against Children: The Adequacy of the International Society for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect (ISPCAN) Child Abuse Screening Tool-Child Version in 9 Balkan Countries. Child Abuse & Neglect 2020, 108, 104636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; et al. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Health Outcomes in Adults: The ACE Study. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences 1998, 90, 31. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/adverse-childhood-experiences-health-outcomes/docview/218184173/se-2.

- Hulme, P.A. Psychometric Evaluation and Comparison of Three Retrospective, Multi-Item Measures of Childhood Sexual Abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect 2007, 31, 853–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebschutz, J.M.; Buchanan-Howland, K.; Chen, C.A.; Frank, D.A.; Richardson, M.A.; Heeren, T.C.; Cabral, H.J.; Rose-Jacobs, R. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) Correlations with Prospective Violence Assessment in a Longitudinal Cohort. Psychological Assessment 2018, 30, 841–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midei, A.J.; Matthews, K.A.; Chang, Y.-F.; Bromberger, J.T. Childhood Physical Abuse Is Associated with Incident Metabolic Syndrome in Mid-Life Women. Health Psychology 2013, 32, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikton, C.; Power, M.; Raleva, M.; Makoae, M.; Al Eissa, M.; Cheah, I.; et al. The Assessment of the Readiness of Five Countries to Implement Child Maltreatment Prevention Programs on a Large Scale. Child Abuse & Neglect 2013, 37, 1237–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, D.C.; Merrick, M.T.; Parks, S.E.; Breiding, M.J.; Gilbert, L.K.; Edwards, V.J.; Dhingra, S.S.; Barile, J.P.; Thompson, W.W. Examination of the Factorial Structure of Adverse Childhood Experiences and Recommendations for Three Subscale Scores. Psychology of Violence 2014, 4, 432–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, K.; Bellis, M.A.; Hughes, K.; Barton, E.R.; Newbury, A. Adverse Childhood Experiences: A Retrospective Study to Understand Their Associations with Lifetime Mental Health Diagnosis, Self-Harm or Suicide Attempt, and Current Low Mental Wellbeing in a Male Welsh Prison Population. Health & Justice 2020, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, G.W.; Gower, T.; Chmielewski, M. Methodological Considerations in ACEs Research. In Adverse Childhood Experiences; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingenfeld, K.; Schäfer, I.; Terfehr, K.; Grabski, H.; Driessen, M.; Grabe, H.; Löwe, B.; Spitzer, C. The Reliable, Valid and Economic Assessment of Early Traumatization: First Psychometric Characteristics of the German Version of the Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire (ACE). Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, Medizinische Psychologie 2011, 61, e10–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovács-Tóth, B.; Oláh, B.; Kuritárné Szabó, I.; Fekete, Z. Psychometric Properties of the Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire 10 Item Version (ACE-10) Among Hungarian Adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology 2023, 14, 1161620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire. In Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/activities/adverse_childhood_experiences/en/.

- Goodman, M.L.; Raimer-Goodman, L.; Chen, C.X.; Grouls, A.; Gitari, S.; Keiser, P.H. Testing and Testing Positive: Childhood Adversities and Later Life HIV Status Among Kenyan Women and Their Partners. Journal of Public Health 2017, 39, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, A.L.G.; Howe, L.D.; Matijasevich, A.; Wehrmeister, F.C.; Menezes, A.M.; Gonçalves, H. Adverse Childhood Experiences: Prevalence and Related Factors in Adolescents of a Brazilian Birth Cohort. Child Abuse & Neglect 2016, 51, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuneef, M.; Qayad, M.; Aleissa, M.; Albuhairan, F. Adverse Childhood Experiences, Chronic Diseases, and Risky Health Behaviors in Saudi Arabian Adults: A Pilot Study. Child Abuse & Neglect 2014, 38, 1787–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shawi, A.F.; Lafta, R.K. Effect of Adverse Childhood Experiences on Physical Health in Adulthood: Results of a Study Conducted in Baghdad City. Journal of Family and Community Medicine 2015, 22, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Q.A.; Dunne, M.P.; Vo, T.V.; Luu, N.H. Adverse Childhood Experiences and the Health of University Students in Eight Provinces of Vietnam. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health 2015, 27, 26S–32S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, C.S.; Muzi, S.; Rogier, G.; Meinero, L.L.; Marcenaro, S. The Adverse Childhood Experiences–International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) in Community Samples Around the World: A Systematic Review (Part I). Child Abuse & Neglect 2022, 129, 105640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinck, F.; Cosma, A.P.; Mikton, C.; Baban, A. Psychometric Properties of the Adverse Childhood Experiences Abuse Short Form (ACE-ASF) Among Romanian High School Students. Child Abuse & Neglect 2017, 72, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, A.; Sireci, S. Validez y Validación para Pruebas Educativas y Psicológicas: Teoría y Recomendaciones. Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. 2021, 14, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz, J.; Elosua, P.; Hambleton, R.K. Directrices para la traducción y adaptación de los tests: Segunda edición. Psicothema 2013, 25, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruchinho, P.; López-Franco, M.D.; Capelas, M.L.; Almeida, S.; Bennett, P.M.; Miranda da Silva, M.; Gaspar, F. Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, and Validation of Measurement Instruments: A Practical Guideline for Novice Researchers. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2024, 17, 2701–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.; Campbell, M.; Copeland, L.; Craig, P.; Movsisyan, A.; Hoddinott, P.; Evans, R. Adapting Interventions to New Contexts—The ADAPT Guidance. BMJ 2021, 374, n1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, K.; Ranger, J.; Ziegler, M. Confirmatory Factor Analyses in Psychological Test Adaptation and Development: A Nontechnical Discussion of the WLSMV Estimator. Psychol. Test Adapt. Dev. 2023, 4, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elosua, P.; Mujika, J.; Almeida, L.S.; Hermosilla, D. Judgmental-Analytical Procedures for Adapting Tests: Adaptation to Spanish of the Reasoning Tests Battery. Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 2014, 46, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoro Dantas Sartori, J. Determining the Confidence Interval for Non-Probabilistic Surveys: Method Proposal and Validation. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 2024, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (Version 4.1) [Computer software]. 2022. Retrieved from (R packages retrieved from CRAN snapshot 2023-04-07).

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monter-Pozos, A.; González-Estrada, E. On Testing the Skew Normal Distribution by Using Shapiro–Wilk Test. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2024, 440, 115649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, S. Comparison of Normality Tests in Terms of Sample Sizes under Different Skewness and Kurtosis Coefficients. Int. J. Assess. Tools Educ. 2022, 9, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkewitz, C.P.; Schwall, P.; Meesters, C.; Hardt, J. Estimating reliability: A comparison of Cronbach's α, McDonald's ωt and the greatest lower bound. Soc. Sci. Human. Open 2023, 7, 100368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfadt, J.M.; Sijtsma, K. Statistical Properties of Lower Bounds and Factor Analysis Methods for Reliability Estimation. In: Wiberg, M.; Molenaar, D.; González, J.; Kim, J.S.; Hwang, H. (Eds.) Quantitative Psychology. IMPS 2021. Springer Proc. Math. Stat. 2022, 393, 57–71. [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y.; Loh, W.W. A structural after measurement approach to structural equation modeling. Psychol. Methods 2024, 29, 561–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiStefano, C.; Shi, D.; Morgan, G.B. Collapsing categories is often more advantageous than modeling sparse data: Investigations in the CFA framework. Struct. Equ. Modeling 2021, 28, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; DiStefano, C.; Zheng, X.; Liu, R.; Jiang, Z. Fitting latent growth models with small sample sizes and non-normal missing data. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2021, 45, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Bentler, P.M. Distributionally weighted least squares in structural equation modeling. Psychol. Methods 2022, 27, 519–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, G.; Hwang, H.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. Cutoff criteria for overall model fit indexes in generalized structured component analysis. J. Mark. Anal. 2020, 8, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Maydeu-Olivares, A. The Effect of Estimation Methods on SEM Fit Indices. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2020, 80, 421–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelle, W. Psych: Procedures for psychological, psychometric, and personality research [R package]. 2019.

- Cheung, G.W.; Wang, C. Current Approaches for Assessing Convergent and Discriminant Validity with SEM: Issues and Solutions. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2017, 2017, 12706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalnins, A.; Praitis Hill, K. The VIF Score. What Is It Good For? Absolutely Nothing. Organizational Research Methods 2025, 28, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Winter, J.C.; Gosling, S.D.; Potter, J. Comparing the Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients across distributions and sample sizes: A tutorial using simulations and empirical data. Psychol. Methods 2016, 21, 273. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/buy/2016-25478-001. [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, A.; Michaelides, M.; Karekla, M. Network analysis: A new psychometric approach to examine the underlying ACT model components. J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 2019, 12, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsboom, D.; Deserno, M.K.; Rhemtulla, M.; et al. Network analysis of multivariate data in psychological science. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2021, 1, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Maris, G.; Waldorp, L.J.; Borsboom, D. Network psychometrics. In The Wiley Handbook of Psychometric Testing: A Multidisciplinary Reference on Survey, Scale and Test Development; 2018; pp. 953–986. [CrossRef]

- Hevey, D. Network analysis: A brief overview and tutorial. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2018, 6, 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegeni, M.; Haghdoost, A.; Shahrbabaki, M.E.; Shahrbabaki, P.M.; Nakhaee, N. Validity and reliability of the Persian version of the Adverse Childhood Experiences Abuse Short Form. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2020, 9, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidman, R.; Smith, D.; Piccolo, L.R.; Kohler, H.P. Psychometric evaluation of the Adverse Childhood Experience International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) in Malawian adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2019, 92, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, J. Comparing the ACE-IQ and CTQ-SF in Chinese university students: Reliability and predictive validity for PTSD and depression. Trauma Violence Abuse 2023, 24, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, A.C.; Rojano, Á.E.V.; Caballero, A.R.; Solé, E.P.; Álvarez, M.G. Associations between mental health problems and Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) in indigenous and non-indigenous Mexican adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2024, 147, 106595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yu, Z.; Wang, L.; Gross, D. Examining Childhood Adversities in Chinese Health Science Students Using the Simplified Chinese Version of the Adverse Childhood Experiences-International Questionnaire (SC-ACE-IQ). Advers. Resil. Sci. 2022, 3, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos-Benavides, L.; Cano-Lozano, M.C.; Ramírez, A.; Rodríguez-Díaz, F.J. Instruments of Child-to-Parent Violence: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2023, 11, 3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos-Benavides, L.; Cano-Lozano, M.C.; Ramírez, A.; Contreras, L.; Rodríguez-Díaz, F.J. To What Extent is Child-to-Parent Violence Known in Latin America? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. Salud 2024, 15, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos-Benavides, L.; Cano-Lozano, M.C.; Ramírez, A.; León, S.P.; Medina-Maldonado, V.; Rodríguez-Díaz, F.J. Assessment of Adolescents in Child-to-Parent Violence: Invariance, Prevalence, and Reasons. Children 2024, 11, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millsap, R.E.; Olivera-Aguilar, M. Investigating measurement invariance using confirmatory factor analysis. In Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 380–392. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2012-16551-023.

- Ramírez, A.; Medina-Maldonado, V.; Burgos-Benavides, L.; Alfaro-Urquiola, A.L.; Sinchi, H.; Herrero Díez, J.; Rodríguez-Diaz, F.J. Validation of the Psychometric Properties of the Conflict Resolution Styles Inventory in the University Population. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Median | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | p | Q1 | Q3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 3 | 3.283 | 1.219 | -0.159 | -1.133 | < .001 | 2 | 4 |

| A2 | 2 | 2.512 | 0.980 | 1.109 | 0.503 | < .001 | 2 | 3 |

| A3 | 3 | 3.025 | 1.162 | 0.285 | -1.050 | < .001 | 2 | 4 |

| A4 | 2 | 2.491 | 0.988 | 1.119 | 0.469 | < .001 | 2 | 3 |

| A5 | 2 | 2.242 | 0.775 | 1.601 | 3.213 | < .001 | 2 | 2 |

| A6 | 2 | 2.117 | 0.646 | 1.769 | 5.340 | < .001 | 2 | 2 |

| A7 | 2 | 2.096 | 0.609 | 2.106 | 7.914 | < .001 | 2 | 2 |

| A8 | 2 | 2.070 | 0.595 | 2.259 | 8.944 | < .001 | 2 | 2 |

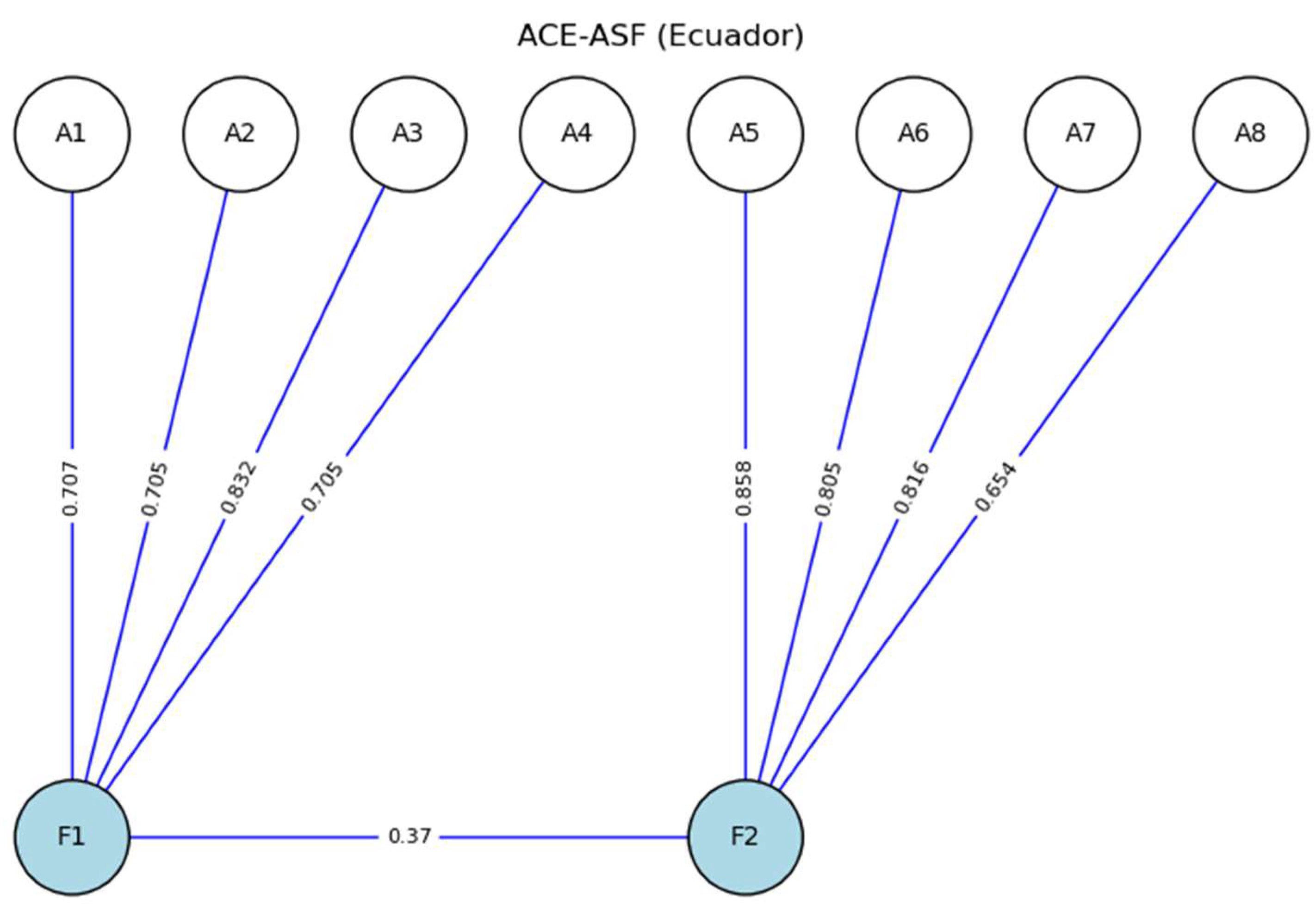

| Factor | Indicator | Std. Est. (all) | α | ω | CR | VIF | ω Total | α Total | F1 | F2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | A1 | 0.707 | 0.823 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 1.42 | 0.872 | 0.812 | 0.553* | |

| A2 | 0.705 | |||||||||

| A3 | 0.832 | |||||||||

| A4 | 0.705 | |||||||||

| F2 | A5 | 0.858 | 0.867 | 0.861 | 0.85 | 1.56 | 0.367** | 0.637* | ||

| A6 | 0.805 | |||||||||

| A7 | 0.816 | |||||||||

| A8 | 0.654 |

| Physical and Emotional | Sexual | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Man | Woman | Man | Woman | |

| n | 402 | 438 | 402 | 438 |

| Mean (M) | 11.100 | 11.500 | 8.147 | 8.868 |

| Std. Deviation | 3.625 | 3.427 | 1.623 | 2.630 |

| Median (Med) | 10 | 11 | 8 | 8 |

| IQR | 6 | 5 | 0 | 1 |

| Minimum | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Maximum | 20 | 20 | 18 | 20 |

| 25th percentile | 8 | 9 | 8 | 8 |

| 50th percentile | 10 | 11 | 8 | 8 |

| 75th percentile | 14 | 14 | 8 | 9 |

| SE | 0.181 | 0.164 | 0.081 | 0.126 |

| Coefficient of variation | 0.327 | 0.298 | 0.199 | 0.297 |

| Mean Rank | 403.552 | 436.055 | 386.223 | 451.960 |

| Sum Rank | 162.228.000 | 190.992.000 | 155.261.500 | 197.958.500 |

| U | 81.225.000 | 74.258.500 | ||

| p | 0.051 | < .001 | ||

| VS-MPR* | 2.430 | 10.461.152 | ||

| Rank-Biserial Correlation (r) | 0.077 | 0.157 | ||

| SE Rank-Biserial Correlation | 0.040 | 0.040 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).