Submitted:

08 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

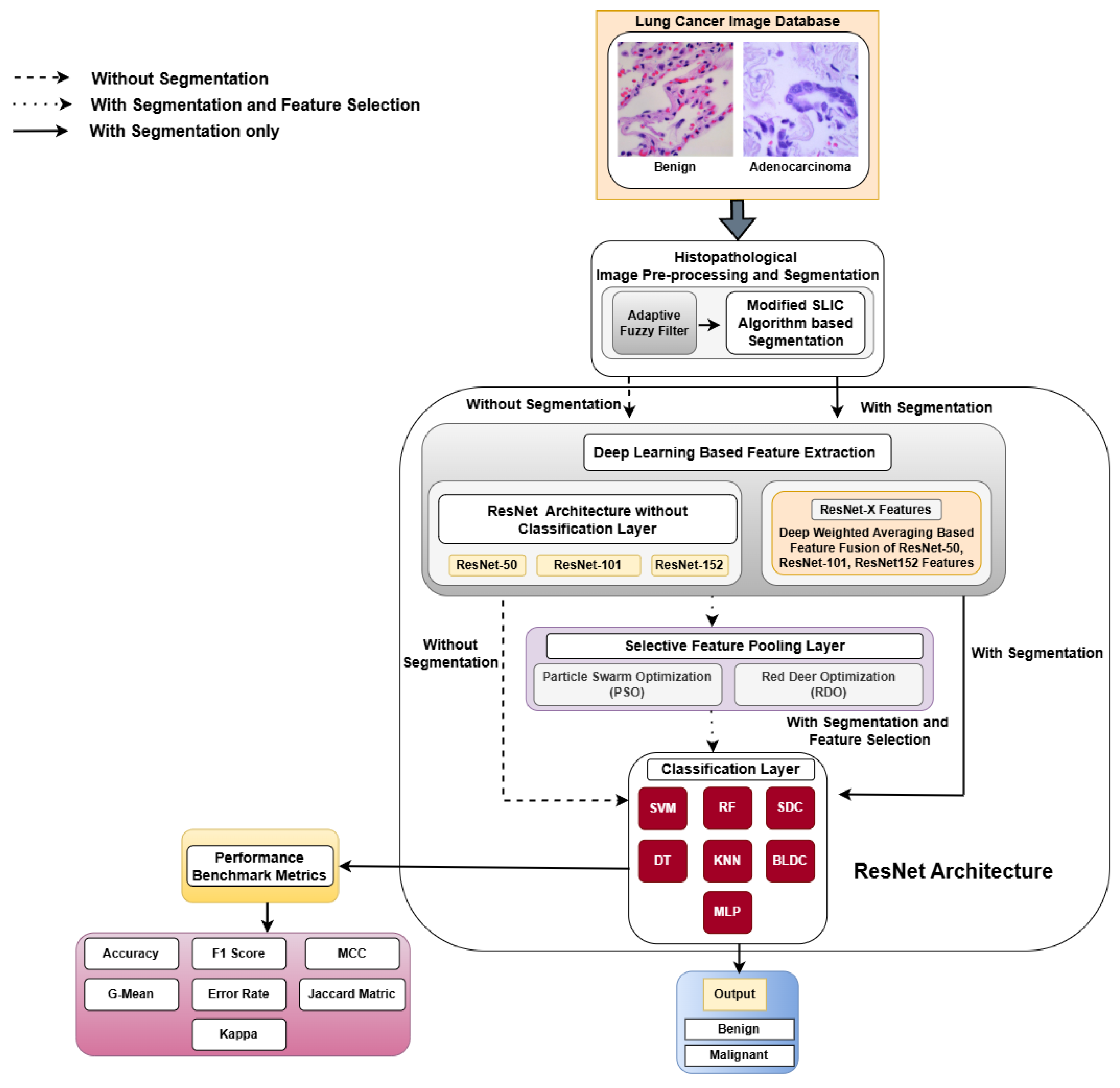

1. Introduction

1.1. Contribution of the Work

2. Review of Lung Cancer Detection

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dataset Used

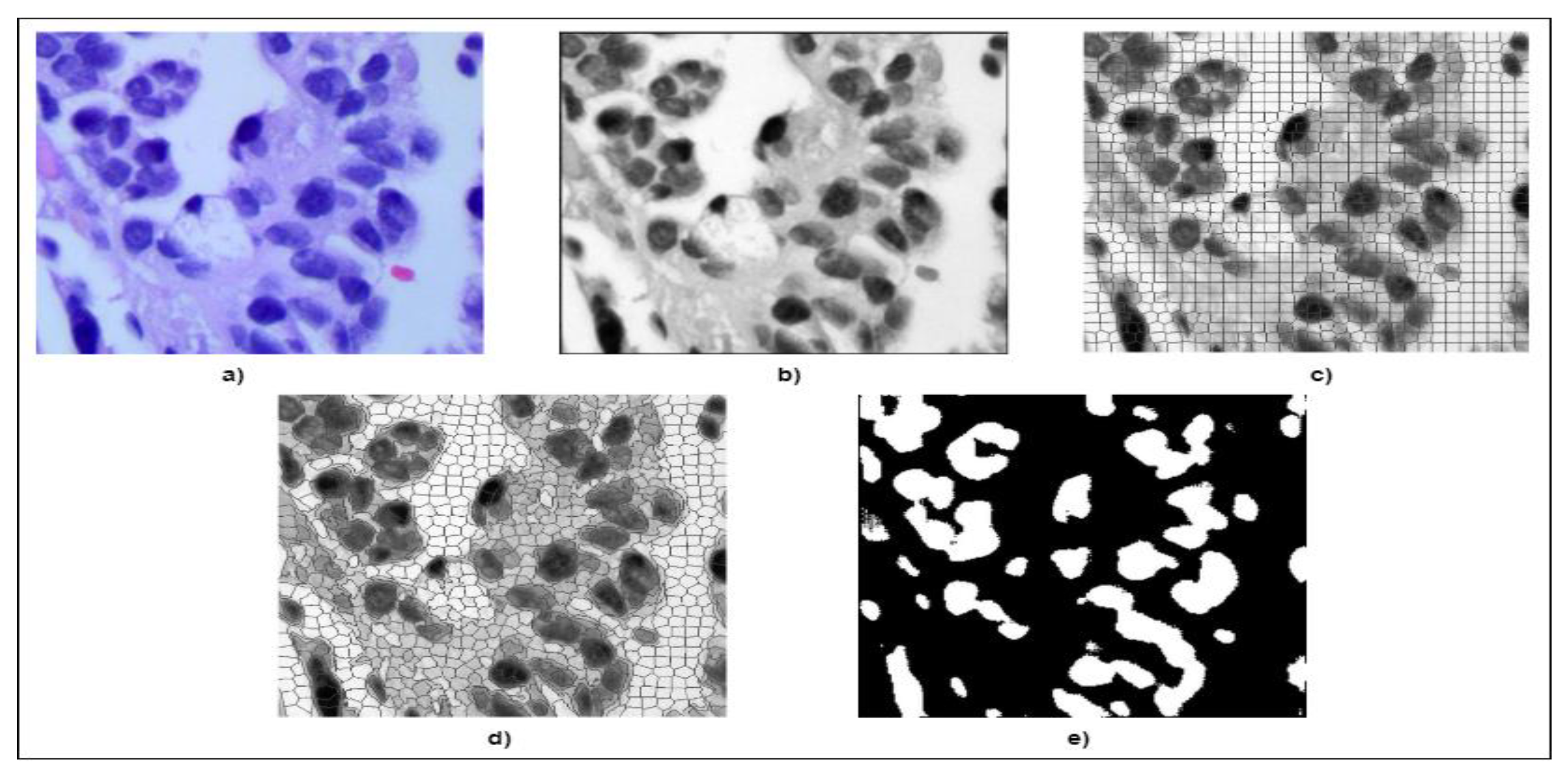

3.2. Image Preprocessing

3.3. Modified SLIC Algorithm-Based Segmentation

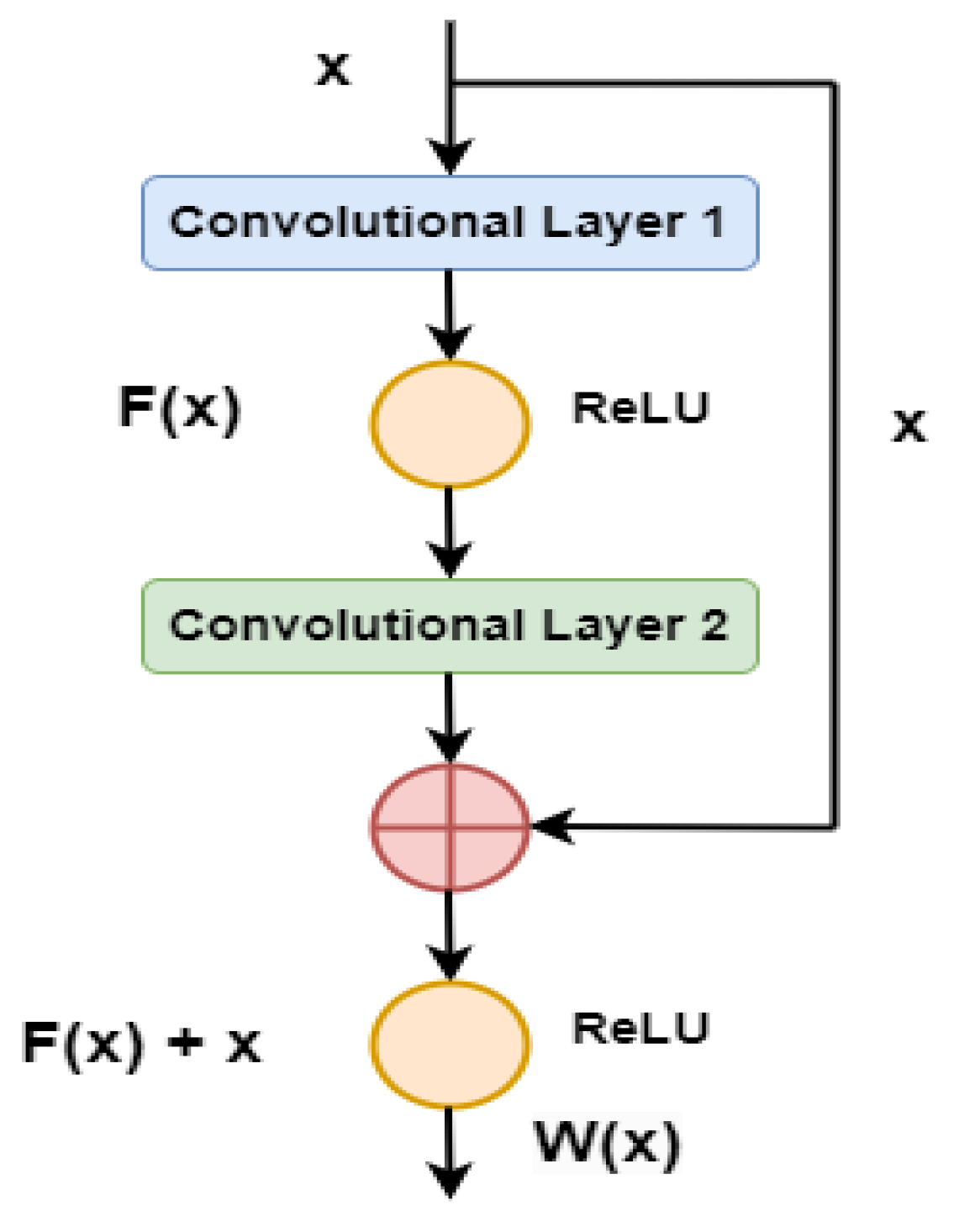

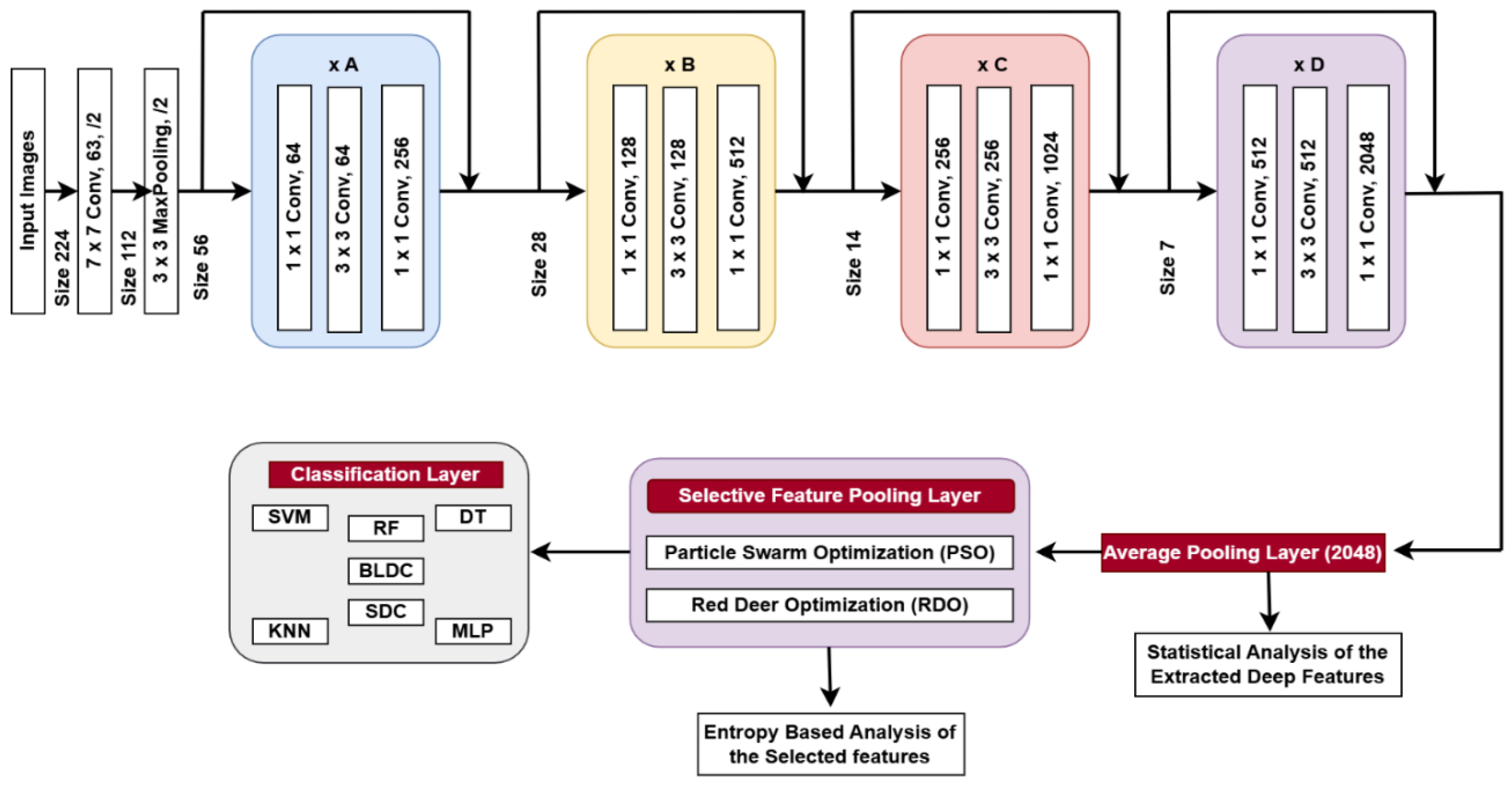

4. Deep Feature Extraction

4.1. Proposed DWAFF Technique for ResNet-X Features

Algorithm 1

Step 01: Extract Features

Step 02: Perform K-Fold Cross Validation

Step 03: Set Initial Weight Range

Step 04: Identify Optimal Weights

Step 05: Compute Mean Values

Step 06: Fuse Features for Final Feature Set

Step 07: Output Final Fused Features

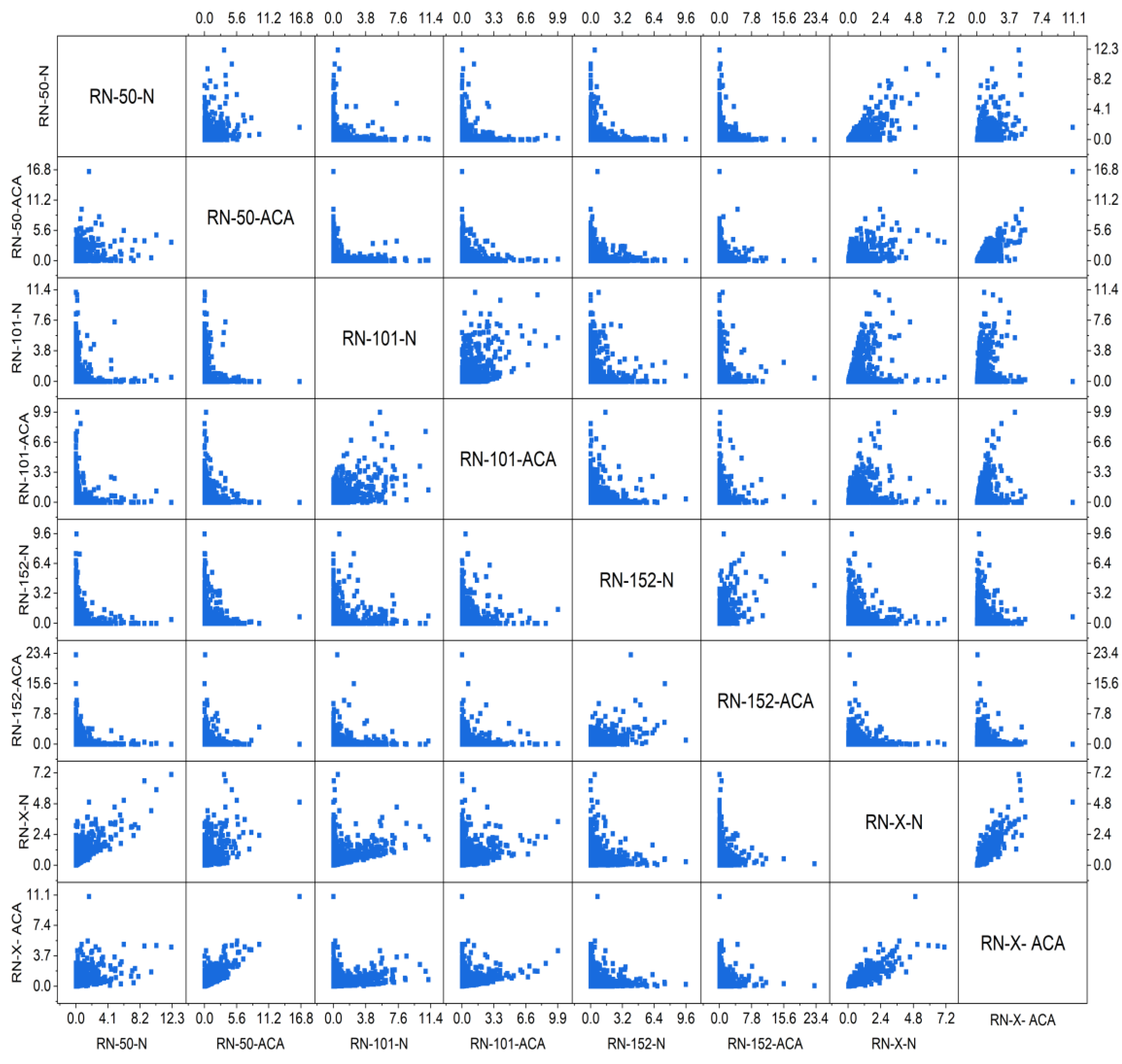

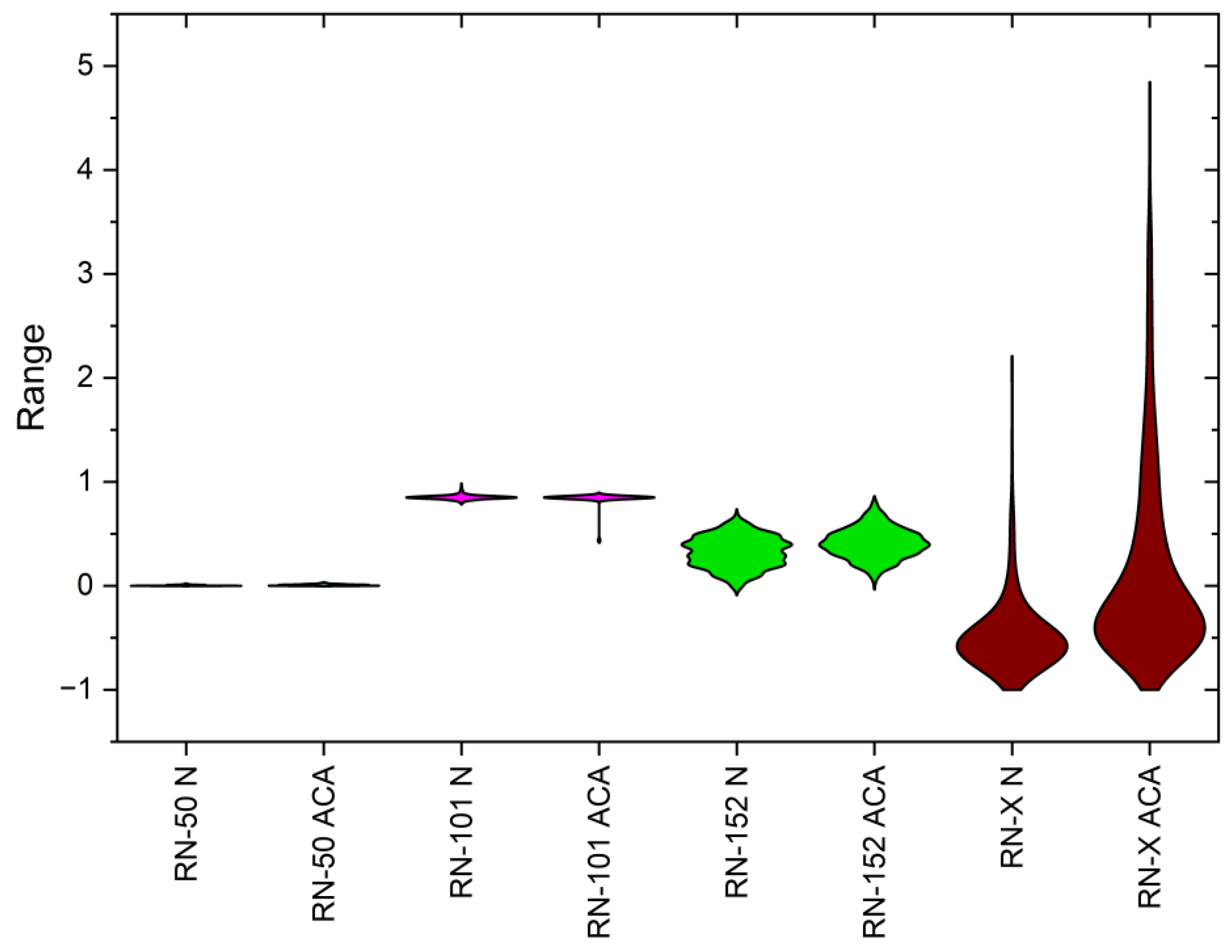

4.2. Statistical Analysis

4.3. Selective Feature Pooling Layer

4.3.1. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

Algorithm 2: PSO

4.3.2. Red Deer Optimization (RDO)

Algorithm 3: RDO

4.4. Entropy Based on Statistical Analysis

4.4.1. Approximate Entropy

4.4.2. Shannon Entropy

4.4.3. Fuzzy Entropy

4.5. Classification Layer

4.5.1. Support Vector Machine (SVM)

4.5.2. Decision Tree (DT)

4.5.3. Random Forest (RF)

4.5.4. K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN)

4.5.5. Softmax Discriminant Classifier (SDC)

4.5.6. Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP)

4.5.7. BLDC

5. Results and Discussion

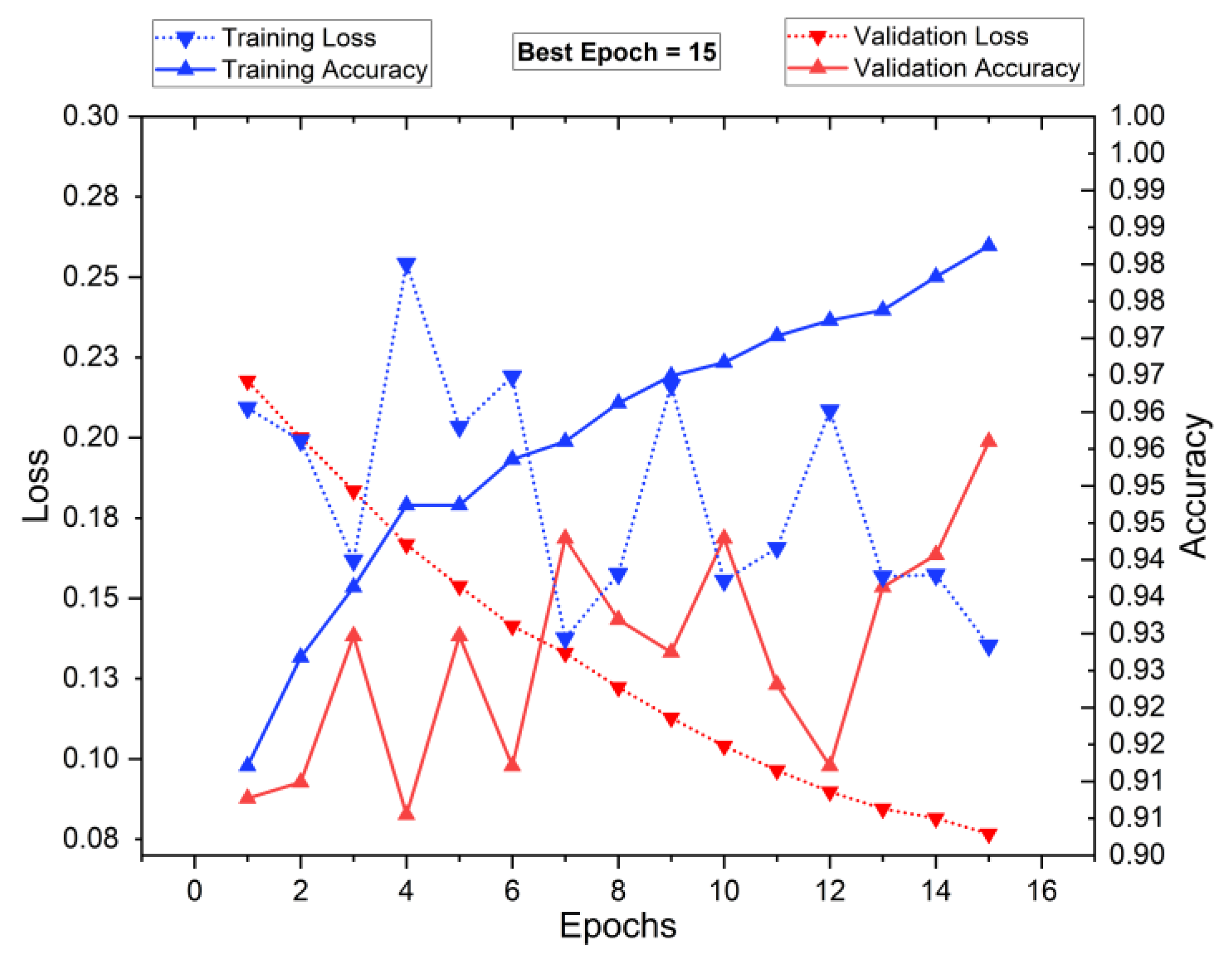

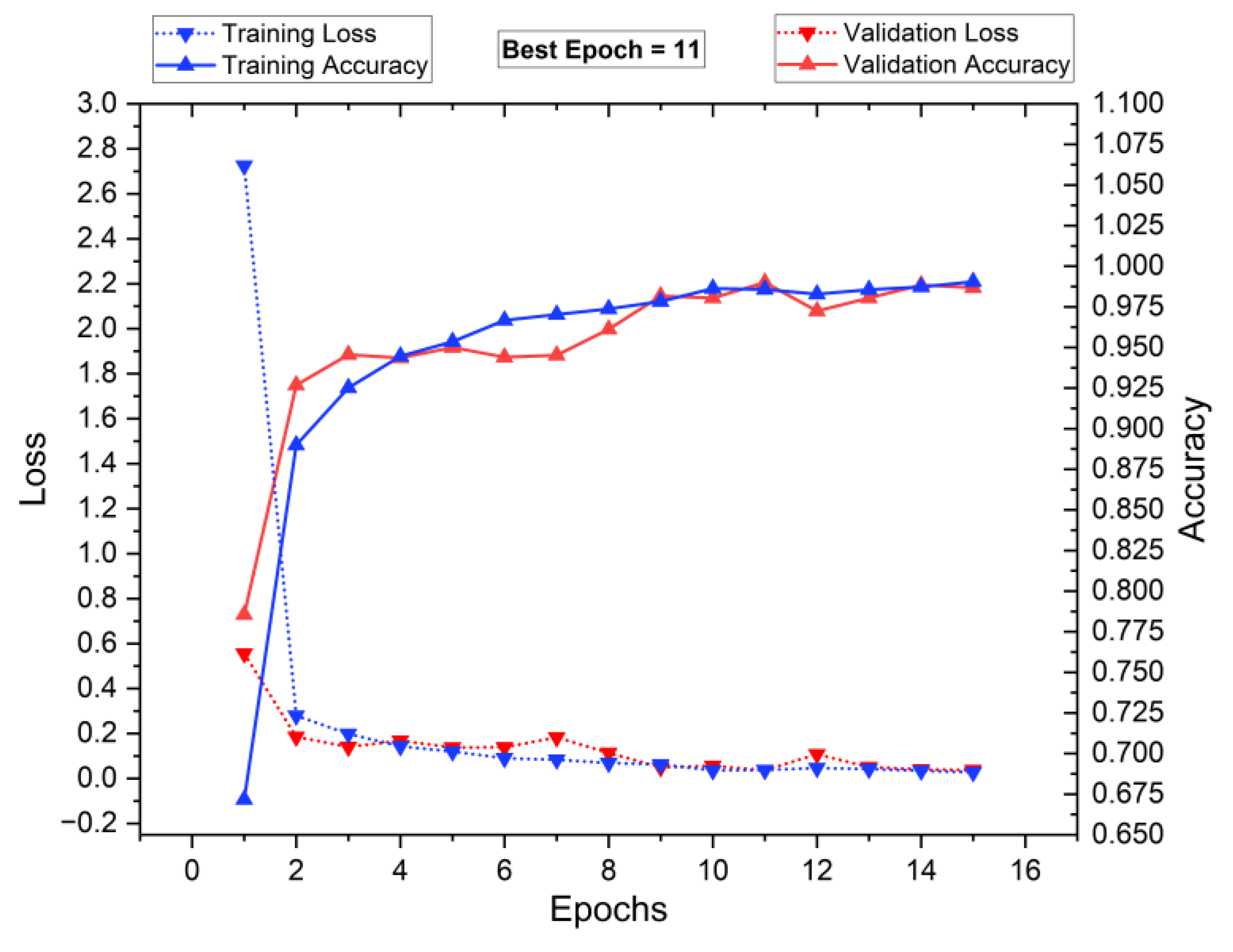

5.1. Training and Testing of the Classifiers

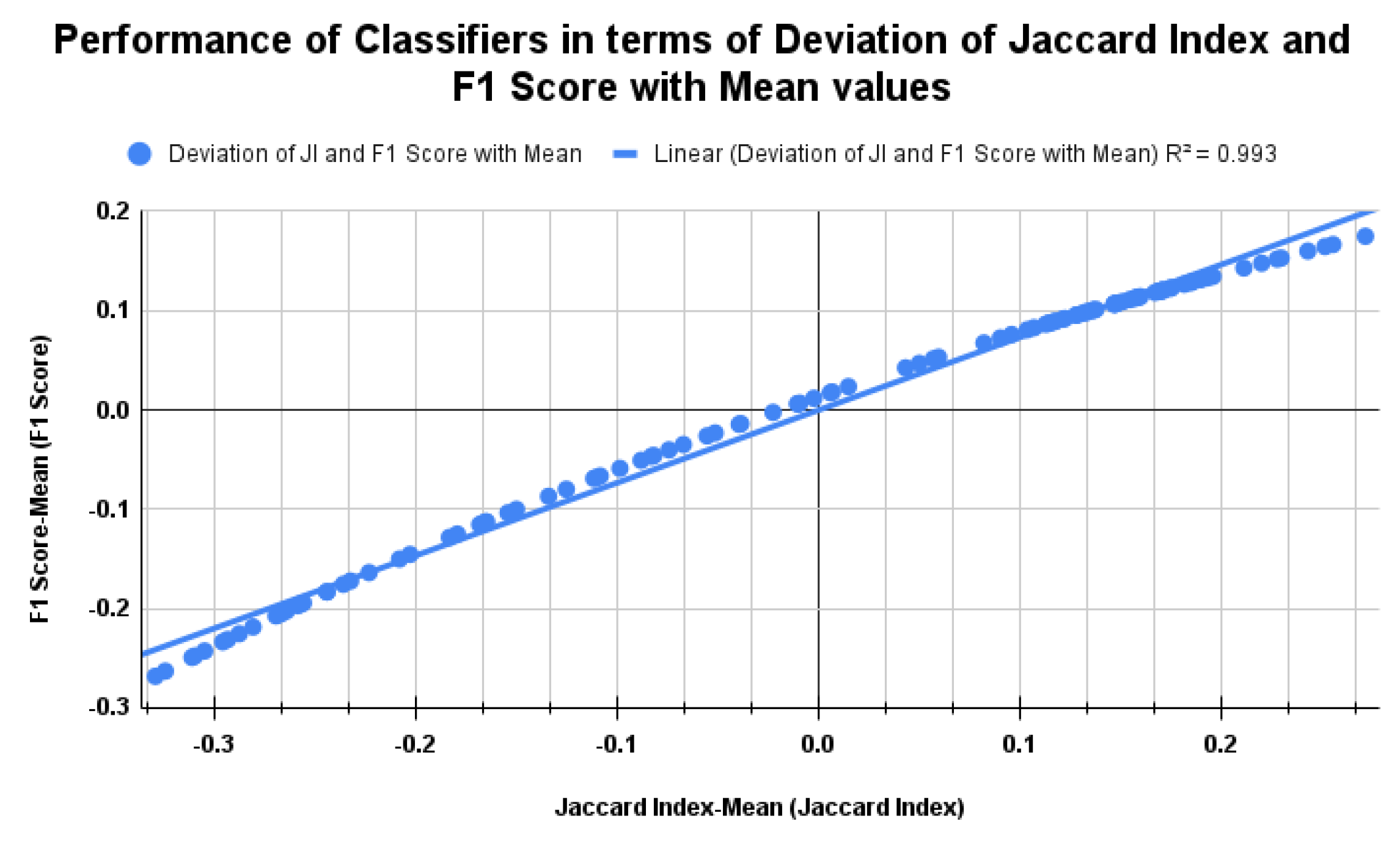

5.2. Standard Benchmark Metrics of the Classifiers

5.3. Performance Analysis of the Classifiers in Terms of Accuracy for Different K Values

| DL model with Classifiers | Without Segmentation and FS | With Segmentation only | With Segmentation and PSO FS | With Segmentation and RDO FS | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K = 2 | K = 4 | K = 5 | K = 8 | K = 10 | K = 2 | K = 4 | K = 5 | K = 8 | K = 10 | K = 2 | K = 4 | K = 5 | K = 8 | K = 10 | K = 2 | K = 4 | K = 5 | K = 8 | K = 10 | |

| ResNet-50-SVM | 53.700 | 59.324 | 62.990 | 62.500 | 57.200 | 65.820 | 65.100 | 72.270 | 73.703 | 74.350 | 65.820 | 72.983 | 71.633 | 82.872 | 90.110 | 73.230 | 77.082 | 83.140 | 85.803 | 89.840 |

| ResNet-50-DT | 54.500 | 56.860 | 60.160 | 57.063 | 67.060 | 60.830 | 64.780 | 71.520 | 70.603 | 73.910 | 61.380 | 71.270 | 73.173 | 83.600 | 91.290 | 72.250 | 78.922 | 78.382 | 85.681 | 90.630 |

| ResNet-50-RF | 56.070 | 59.164 | 62.630 | 59.914 | 68.230 | 62.960 | 66.213 | 68.260 | 72.790 | 79.420 | 62.960 | 74.150 | 74.743 | 86.920 | 93.110 | 75.830 | 79.040 | 82.422 | 87.141 | 91.140 |

| ResNet-50-KNN | 53.690 | 59.650 | 62.370 | 66.540 | 65.540 | 61.530 | 68.033 | 66.473 | 71.100 | 72.790 | 61.530 | 73.570 | 65.430 | 87.500 | 89.840 | 73.590 | 75.950 | 78.642 | 84.120 | 93.350 |

| ResNet-50-SDC | 55.190 | 60.450 | 64.070 | 68.445 | 59.790 | 59.730 | 69.733 | 70.573 | 77.862 | 80.730 | 71.100 | 72.790 | 75.260 | 91.012 | 92.750 | 77.760 | 76.302 | 82.812 | 85.810 | 93.750 |

| ResNet-50-BLDC | 51.420 | 56.510 | 57.430 | 57.950 | 58.150 | 63.590 | 63.404 | 64.490 | 74.673 | 77.090 | 65.950 | 65.230 | 65.883 | 78.840 | 87.100 | 73.170 | 73.700 | 77.220 | 83.332 | 90.880 |

| ResNet-50-MLP | 53.710 | 61.704 | 65.230 | 62.440 | 58.700 | 66.850 | 71.110 | 72.363 | 83.730 | 81.250 | 72.250 | 74.773 | 77.082 | 92.181 | 94.010 | 77.980 | 79.752 | 85.160 | 91.731 | 95.310 |

| ResNet-101-SVM | 54.900 | 61.270 | 61.220 | 67.580 | 64.330 | 63.220 | 64.524 | 66.103 | 77.990 | 69.760 | 63.590 | 70.893 | 68.163 | 86.713 | 89.960 | 76.590 | 80.800 | 75.130 | 89.451 | 90.760 |

| ResNet-101-DT | 56.620 | 61.820 | 62.760 | 61.440 | 60.940 | 60.830 | 67.210 | 64.980 | 73.960 | 76.110 | 61.340 | 71.550 | 64.230 | 80.210 | 90.620 | 73.373 | 76.942 | 76.170 | 82.950 | 91.670 |

| ResNet-101-RF | 57.310 | 62.350 | 63.970 | 63.670 | 65.130 | 62.000 | 69.010 | 66.000 | 78.640 | 74.020 | 62.000 | 72.500 | 65.890 | 82.292 | 91.670 | 74.090 | 77.932 | 78.902 | 89.711 | 93.350 |

| ResNet-101-KNN | 54.242 | 60.960 | 56.330 | 60.430 | 67.969 | 64.010 | 70.380 | 67.380 | 73.050 | 80.980 | 64.750 | 65.310 | 73.153 | 86.761 | 87.760 | 74.590 | 80.270 | 81.572 | 83.592 | 90.230 |

| ResNet-101-SDC | 58.450 | 62.990 | 63.770 | 66.570 | 60.680 | 64.520 | 71.910 | 68.360 | 80.790 | 82.550 | 68.700 | 71.383 | 77.342 | 89.321 | 93.490 | 75.010 | 78.390 | 83.752 | 90.760 | 97.130 |

| ResNet-101-BLDC | 53.700 | 56.720 | 56.249 | 56.774 | 54.450 | 59.680 | 63.530 | 67.970 | 75.000 | 81.310 | 60.830 | 63.570 | 68.040 | 79.560 | 90.360 | 69.240 | 73.113 | 75.520 | 82.620 | 89.320 |

| ResNet-101-MLP | 58.610 | 63.150 | 64.490 | 66.780 | 60.530 | 66.420 | 72.910 | 72.581 | 82.940 | 84.120 | 70.590 | 74.610 | 78.130 | 92.441 | 94.530 | 77.830 | 76.432 | 84.640 | 92.906 | 96.350 |

| ResNet152-SVM | 56.090 | 61.080 | 60.414 | 66.123 | 61.360 | 63.580 | 66.410 | 71.750 | 77.150 | 74.480 | 66.420 | 68.050 | 69.013 | 84.900 | 93.220 | 74.290 | 76.240 | 81.250 | 82.560 | 92.370 |

| ResNet152-DT | 53.840 | 62.870 | 61.704 | 62.714 | 55.970 | 64.660 | 68.820 | 66.410 | 75.062 | 73.370 | 64.520 | 70.960 | 71.873 | 88.541 | 90.110 | 70.890 | 80.080 | 81.672 | 82.352 | 92.570 |

| ResNet152-RF | 57.950 | 63.090 | 62.990 | 68.160 | 63.670 | 65.840 | 70.060 | 68.490 | 71.873 | 80.070 | 68.100 | 71.350 | 76.822 | 89.190 | 92.180 | 71.093 | 81.900 | 82.820 | 85.970 | 93.030 |

| ResNet152-KNN | 54.940 | 62.000 | 57.120 | 60.804 | 66.270 | 61.380 | 65.853 | 61.704 | 70.320 | 81.510 | 63.580 | 69.530 | 73.953 | 79.820 | 91.460 | 72.340 | 81.380 | 84.250 | 86.983 | 92.310 |

| ResNet152-SDC | 56.190 | 60.690 | 63.386 | 65.500 | 67.550 | 65.950 | 69.760 | 73.940 | 74.480 | 82.090 | 68.100 | 75.690 | 73.960 | 92.190 | 93.750 | 73.563 | 82.170 | 85.160 | 92.748 | 95.960 |

| ResNet152-BLDC | 55.930 | 55.810 | 59.444 | 58.840 | 59.340 | 59.830 | 64.000 | 66.670 | 72.620 | 75.770 | 63.220 | 63.900 | 70.920 | 79.750 | 93.230 | 69.273 | 78.970 | 76.885 | 82.690 | 86.710 |

| ResNet152-MLP | 56.250 | 61.460 | 64.157 | 68.783 | 57.880 | 66.920 | 72.010 | 74.380 | 78.902 | 85.420 | 70.480 | 76.432 | 79.490 | 93.508 | 94.520 | 77.100 | 82.550 | 87.240 | 93.435 | 97.660 |

| ResNet-X-SVM | 57.410 | 56.120 | 57.670 | 67.300 | 56.780 | 62.100 | 66.703 | 68.230 | 70.703 | 73.300 | 66.280 | 66.490 | 70.813 | 82.812 | 91.670 | 77.410 | 80.110 | 77.862 | 89.650 | 91.640 |

| ResNet-X-DT | 54.900 | 59.830 | 61.460 | 63.480 | 60.020 | 61.080 | 71.650 | 66.970 | 72.530 | 76.690 | 64.010 | 73.390 | 66.670 | 85.680 | 88.600 | 69.730 | 76.170 | 78.252 | 84.770 | 92.180 |

| ResNet-X-RF | 56.120 | 62.100 | 63.150 | 64.390 | 64.800 | 64.660 | 72.460 | 71.093 | 77.410 | 77.580 | 66.920 | 74.800 | 70.633 | 87.761 | 92.190 | 70.543 | 79.920 | 84.892 | 86.391 | 94.010 |

| ResNet-X-KNN | 56.860 | 55.514 | 58.760 | 60.610 | 54.850 | 61.340 | 67.650 | 67.153 | 77.990 | 78.650 | 68.690 | 70.303 | 68.670 | 88.801 | 91.660 | 71.240 | 77.790 | 78.772 | 89.871 | 93.220 |

| ResNet-X-SDC | 58.450 | 60.960 | 62.760 | 67.690 | 68.930 | 64.750 | 65.450 | 73.180 | 80.210 | 83.850 | 70.080 | 75.130 | 70.633 | 90.881 | 93.490 | 72.530 | 82.712 | 82.032 | 92.451 | 97.860 |

| ResNet-X-BLDC | 54.090 | 54.900 | 57.310 | 59.414 | 61.060 | 56.860 | 63.780 | 68.813 | 71.230 | 72.550 | 60.830 | 64.800 | 64.157 | 87.760 | 92.180 | 69.010 | 76.822 | 78.780 | 82.030 | 88.540 |

| ResNet-X--MLP | 58.570 | 61.050 | 64.980 | 68.033 | 69.610 | 66.280 | 68.650 | 74.020 | 81.772 | 86.460 | 71.000 | 76.240 | 71.100 | 93.231 | 96.490 | 74.090 | 82.810 | 84.633 | 94.531 | 98.680 |

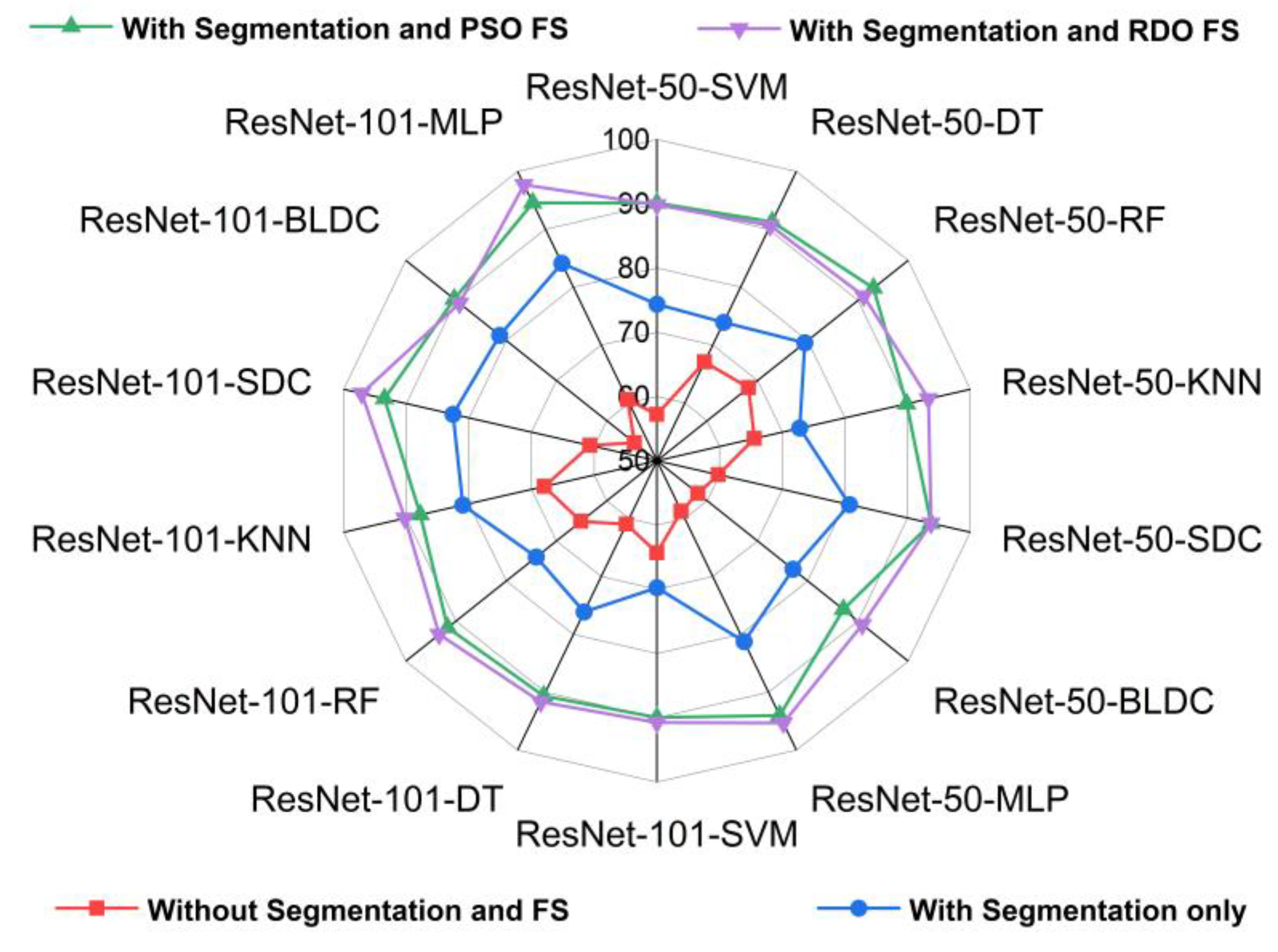

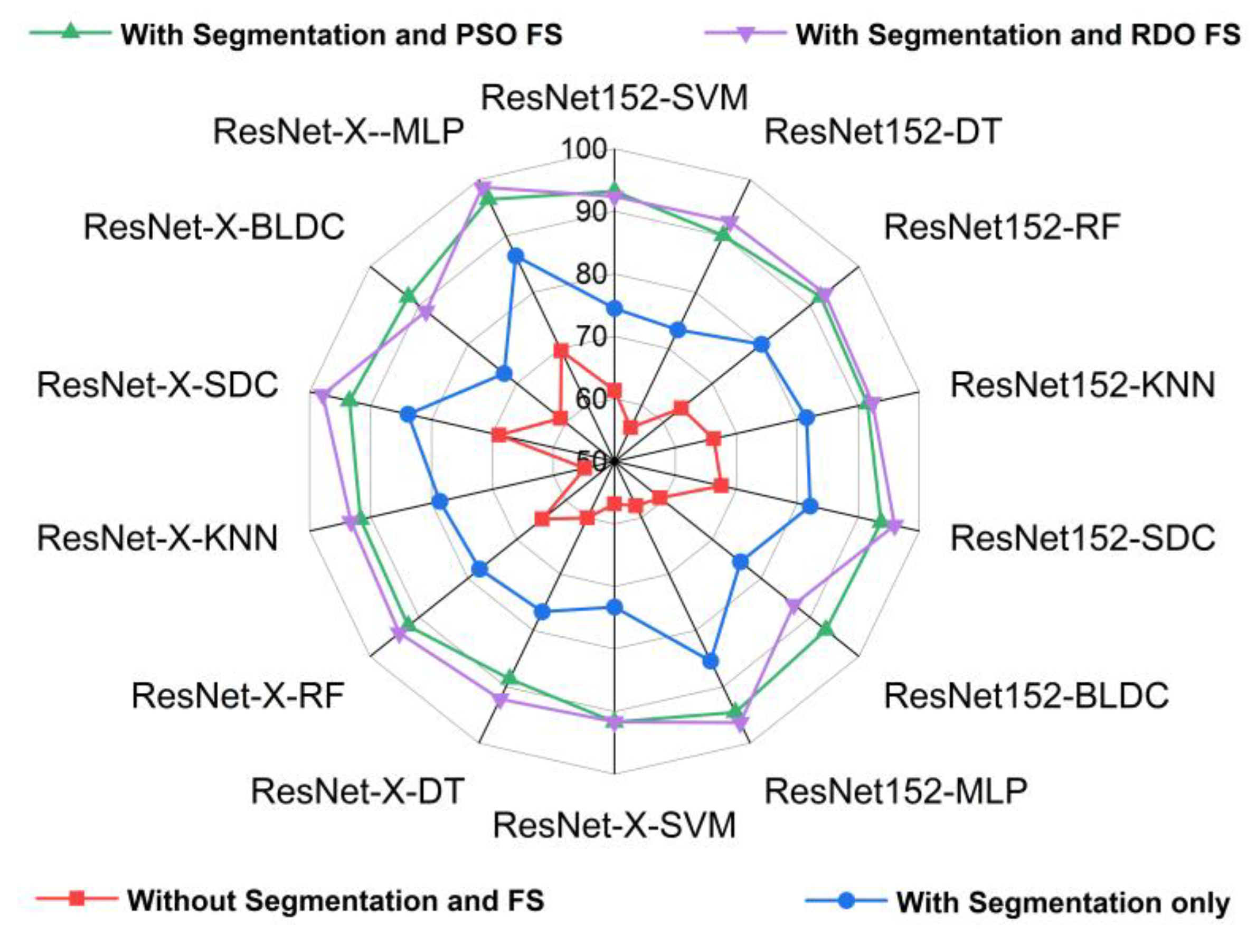

5.4. Performance Analysis of Classifiers for K = 10

5.5. Major Outcomes and Limitations

5.6. Computational Complexity

6. Conclusions

References

- WHO REPORT ON CANCER SETTING PRIORITIES, INVESTING WISELY AND PROVIDING CARE FOR ALL 2020 WHO report on cancer: setting priorities, investing wisely and providing care for all. 2020. [Online]. Available: http://apps.who.int/bookorders.

- R. L. Siegel, A. N. Giaquinto, and A. Jemal, “Cancer statistics, 2024,” CA Cancer J Clin, vol. 74, no. 1, pp. 12–49, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Sung et al., “Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries,” CA Cancer J Clin, vol. 71, no. 3, pp. 209–249, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Araghi et al., “Global trends in colorectal cancer mortality: projections to the year 2035,” Int J Cancer, vol. 144, no. 12, pp. 2992–3000, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board (Ed.) WHO Classification of Tumours. In Thoracic Tumours, 5th ed.; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2021; ISBN 978-92-832-4506-3.

- D. A. Andreadis, A. M. Pavlou, and P. Panta, “Biopsy and oral squamous cell carcinoma histopathology,” in Oral Cancer Detection: Novel Strategies and Clinical Impact, Springer International Publishing, 2019, pp. 133–151. [CrossRef]

- O. Ozdemir, R. L. Russell, and A. A. Berlin, “A 3D Probabilistic Deep Learning System for Detection and Diagnosis of Lung Cancer Using Low-Dose CT Scans,” IEEE Trans Med Imaging, vol. 39, no. 5, pp. 1419–1429, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Teramoto, T. Tsukamoto, Y. Kiriyama, and H. Fujita, “Automated Classification of Lung Cancer Types from Cytological Images Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks,” Biomed Res Int, vol. 2017, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Anthimopoulos, S. Christodoulidis, L. Ebner, A. Christe, and S. Mougiakakou, “Lung Pattern Classification for Interstitial Lung Diseases Using a Deep Convolutional Neural Network,” IEEE Trans Med Imaging, vol. 35, no. 5, pp. 1207–1216, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- O. Iizuka, F. Kanavati, K. Kato, M. Rambeau, K. Arihiro, and M. Tsuneki, “Deep Learning Models for Histopathological Classification of Gastric and Colonic Epithelial Tumours,” Sci Rep, vol. 10, no. 1, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Wang et al., “ConvPath: A software tool for lung adenocarcinoma digital pathological image analysis aided by a convolutional neural network,” EBioMedicine, vol. 50, pp. 103–110, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Gessert, M. Nielsen, M. Shaikh, R. Werner, and A. Schlaefer, “Skin lesion classification using ensembles of multi-resolution EfficientNets with meta data,” MethodsX, vol. 7, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, X. Liu, and Y. Qi, “Adaptive Threshold Learning in Frequency Domain for Classification of Breast Cancer Histopathological Images,” International Journal of Intelligent Systems, vol. 2024, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhou, C. Zhang, and S. Gao, “Breast Cancer Classification From Histopathological Images Using Resolution Adaptive Network,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 35977–35991, 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Wang, J. Wang, Y. Li, P. Li, L. Li, and M. Jiang, “Automatic classification of breast cancer histopathological images based on deep feature fusion and enhanced routing,” Biomed Signal Process Control, vol. 65, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Aresta et al., “BACH: Grand challenge on breast cancer histology images,” Med Image Anal, vol. 56, pp. 122–139, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. A. Spanhol, L. S. Oliveira, C. Petitjean and L. Heutte, "Breast cancer histopathological image classification using Convolutional Neural Networks," 2016 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2016, pp. 2560-2567. [CrossRef]

- P. Filipczuk, T. Fevens, A. Krzyzak, and R. Monczak, “Computer-aided breast cancer diagnosis based on the analysis of cytological images of fine needle biopsies,” IEEE Trans Med Imaging, vol. 32, no. 12, pp. 2169–2178, Dec. 2013. [CrossRef]

- N. Mobark, S. Hamad, and S. Z. Rida, “CoroNet: Deep Neural Network-Based End-to-End Training for Breast Cancer Diagnosis,” Applied Sciences (Switzerland), vol. 12, no. 14, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Araujo et al., “Classification of breast cancer histology images using convolutional neural networks,” PLoS One, vol. 12, no. 6, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Rafiq et al., “Detection and Classification of Histopathological Breast Images Using a Fusion of CNN Frameworks,” Diagnostics, vol. 13, no. 10, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Hameed, S. Zahia, B. Garcia-Zapirain, J. J. Aguirre, and A. M. Vanegas, “Breast cancer histopathology image classification using an ensemble of deep learning models,” Sensors (Switzerland), vol. 20, no. 16, pp. 1–17, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Wang, X. Hu, Y. Li, Q. Liu, and X. Zhu, “Automatic cell nuclei segmentation and classification of breast cancer histopathology images,” Signal Processing, vol. 122, pp. 1–13, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Borkowski, M. M. Bui, L. Brannon Thomas, C. P. Wilson, L. A. Deland, and S. M. Mastorides, “Lung and Colon Cancer Histopathological Image Dataset (LC25000).” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/beamandrew/medical-data.

- S. Boumaraf, X. Liu, Z. Zheng, X. Ma, and C. Ferkous, “A new transfer learning-based approach to magnification dependent and independent classification of breast cancer in histopathological images,” Biomed Signal Process Control, vol. 63, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Achanta, A. Shaji, K. Smith, A. Lucchi, P. Fua, and S. Süsstrunk, “SLIC superpixels compared to state-of-the-art superpixel methods,” IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell, vol. 34, no. 11, pp. 2274–2281, 2012. [CrossRef]

- He, Kaiming & Zhang, Xiangyu & Ren, Shaoqing & Sun, Jian. (2016). Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. 770-778. 10.1109/CVPR.2016.90.

- D. Theckedath and R. R. Sedamkar, “Detecting Affect States Using VGG16, ResNet50 and SE-ResNet50 Networks,” SN Comput Sci, vol. 1, no. 2, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Alinsaif and J. Lang, “Texture features in the Shearlet domain for histopathological image classification,” BMC Med Inform Decis Mak, vol. 20, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Goel, L., Patel, P. Improving YOLOv6 using advanced PSO optimizer for weight selection in lung cancer detection and classification. Multimed Tools Appl 83, 78059–78092 (2024). [CrossRef]

- A. M. Fathollahi-Fard, M. Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, and R. Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, “Red deer algorithm (RDA): a new nature-inspired meta-heuristic,” Soft Computing, vol. 24, no. 19, pp. 14637–14665, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Pincus SM. “Approximate entropy as a measure of system complexity”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Mar 15;88(6):2297-301. PMID: 11607165; PMCID: PMC51218. [CrossRef]

- Bart Kosko, Fuzzy entropy and conditioning, Information Sciences, Volume 40, Issue 2, 1986, Pages 165-174. [CrossRef]

- V. M. Rachel and S. Chokkalingam, "Efficiency of Decision Tree Algorithm For Lung Cancer CT-Scan Images Comparing With SVM Algorithm," 2022 3rd International Conference on Smart Electronics and Communication (ICOSEC), Trichy, India, 2022, pp. 1561-1565. [CrossRef]

- C L, S P, Kashyap AH, Rahaman A, Niranjan S, Niranjan V. Novel Biomarker Prediction for Lung Cancer Using Random Forest Classifiers. Cancer Inform. 2023 Apr 21; 22:11769351231167992. [CrossRef]

- Y. Song, J. Huang, D. Zhou, H. Zha, and C. L. Giles, “LNAI 4702 - IKNN: Informative K-Nearest Neighbor Pattern Classification,” 2007, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 4702. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- F. Zang and J. S. Zhang, “Softmax discriminant classifier,” in Proceedings - 3rd International Conference on Multimedia Information Networking and Security, MINES 2011, 2011, pp. 16–19. [CrossRef]

- Liu M, Li L, Wang H, Guo X, Liu Y, Li Y, Song K, Shao Y, Wu F, Zhang J, Sun N, Zhang T, Luan L. A multilayer perceptron-based model applied to histopathology image classification of lung adenocarcinoma subtypes. Front Oncol. 2023 May 18; 13:1172234. [CrossRef]

- Cybenko, G. Approximation by superpositions of a sigmoidal function. Math. Control Signal Systems 2, 303–314 (1989). [CrossRef]

- M. Kalaiyarasi, H. Rajaguru and S. Ravi, "PFCM Approach for Enhancing Classification of Colon Cancer Tumors using DNA Microarray Data," 2023 Third International Conference on Smart Technologies, Communication and Robotics (STCR), Sathyamangalam, India, 2023, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- D. K. Jain, K. M. Lakshmi, K. P. Varma, M. Ramachandran, and S. Bharati, “Lung Cancer Detection Based on Kernel PCA-Convolution Neural Network Feature Extraction and Classification by Fast Deep Belief Neural Network in Disease Management Using Multimedia Data Sources,” Comput Intell Neurosci, vol. 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Civit-Masot, A. Bañuls-Beaterio, M. Domínguez-Morales, M. Rivas-Pérez, L. Muñoz-Saavedra, and J. M. Rodríguez Corral, “Non-small cell lung cancer diagnosis aid with histopathological images using Explainable Deep Learning techniques,” Comput Methods Programs Biomed, vol. 226, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Naseer, T. Masood, S. Akram, A. Jaffar, M. Rashid, and M. A. Iqbal, “Lung Cancer Detection Using Modified AlexNet Architecture and Support Vector Machine,” Computers, Materials and Continua, vol. 74, no. 1, pp. 2039–2054, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang et al., “Targeting tumor heterogeneity: multiplex-detection-based multiple instances learning for whole slide image classification,” Bioinformatics, vol. 39, no. 3, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Masud, N. Sikder, A. Al Nahid, A. K. Bairagi, and M. A. Alzain, “A machine learning approach to diagnosing lung and colon cancer using a deep learning-based classification framework,” Sensors (Switzerland), vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 1–21, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. R. Wahid, C. Nisa, R. P. Amaliyah, and E. Y. Puspaningrum, “Lung and colon cancer detection with convolutional neural networks on histopathological images,” in AIP Conference Proceedings, American Institute of Physics Inc., Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Liu et al., “A multilayer perceptron-based model applied to histopathology image classification of lung adenocarcinoma subtypes,” Front Oncol, vol. 13, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Gupta, M. K. Gupta, M. Shabaz, and A. Sharma, “Deep learning techniques for cancer classification using microarray gene expression data,” Sep. 30, 2022, Frontiers Media S.A. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu et al., “CroReLU: Cross-Crossing Space-Based Visual Activation Function for Lung Cancer Pathology Image Recognition,” Cancers (Basel), vol. 14, no. 21, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, G. Yu, Z. Yan, L. Wan, W. Wang, and L. Cui, “Lung Cancer Subtype Diagnosis by Fusing Image-Genomics Data and Hybrid Deep Networks,” IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 512–523, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mastouri, R., Khlifa, N., Neji, H. et al. A bilinear convolutional neural network for lung nodules classification on CT images. Int J CARS 16, 91–101 (2021). [CrossRef]

- M. Phankokkruad, “Ensemble Transfer Learning for Lung Cancer Detection,” in ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, Association for Computing Machinery, Jul. 2021, pp. 438–442. [CrossRef]

- Syed Usama Khalid Bukhari, Asmara Syed, Syed Khuzaima Arsalan Bokhari, Syed Shahzad Hussain, Syed Umar Armaghan, Syed Sajid Hussain Shah. “The Histological Diagnosis of Colonic Adenocarcinoma by Applying Partial Self Supervised Learning”, medRxiv 2020.08.15.20175760;. [CrossRef]

| ResNet Architectures | A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RN-50 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 3 |

| RN-101 | 3 | 4 | 23 | 3 |

| RN-152 | 3 | 8 | 36 | 3 |

| Statistical Parameters | ResNet-50 | ResNet-101 | ResNet-152 | DWAFF- ResNet-X | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | ACA | N | ACA | N | ACA | N | ACA | |

| Mean | 0.33849 | 0.342961 | 0.344422 | 0.334716 | 0.350822 | 0.341976 | 0.453891 | 0.453709 |

| Variance | 0.714733 | 0.810025 | 0.792067 | 0.84634 | 0.798777 | 0.865552 | 0.380702 | 0.444597 |

| Skewness | 5.446134 | 5.940833 | 5.438773 | 6.000539 | 5.552535 | 6.224899 | 3.767961 | 4.486885 |

| Kurtosis | 43.68334 | 52.99684 | 42.83772 | 52.96116 | 46.38955 | 60.27778 | 21.14865 | 33.4781 |

| PCC | 0.499424 | 0.52724 | 0.495801 | 0.516755 | 0.494458 | 0.518542 | 0.938638 | 0.944338 |

| Dice Coefficient | 0.7512 | 0.7043 | 0.8028 | 0.7557 | 0.8598 | 0.8011 | 0.9038 | 0.8572 |

| CCA | 0.7018 | 0.7532 | 0.8293 | 0.8816 | ||||

| S No | Parameters | Value | S No | Parameters | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Number of Population | 100 | 6 | Beta | 0.5 |

| 2 | Simulation Time | 13 (s) | 7 | Gamma | 0.6 |

| 3 | Number of Male RD | 12 | 8 | Roar | 0.23 |

| 4 | Number of Hinds | 58 | 9 | Fight | 0.47 |

| 5 | Alpha | 0.9 | 10 | Mating | 0.78 |

| Statistical Measures | PSO | RDO | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | ACA | N | ACA | |

| Approximate Entropy | 1.2385 | 1.7816 | 2.0123 | 2.4893 |

| Shannon Entropy | 3.8523 | 4.9891 | 5.0821 | 5.8982 |

| Fuzzy Entropy | 0.4862 | 0.5231 | 0.7283 | 0.9182 |

| Classifiers | Description |

|---|---|

| SVM | Kernel Function-RBF; Support vector coefficient, α = 1.8; Gaussian function bandwidth (σ) = 98; Bias term (b) = 0.012; Convergence Criterion-MSE. |

| KNN | K-5; Distance Metric-Euclidian; Weight-0.52; Criterion-MSE. |

| RF | Number of Trees-150; Maximum Depth-15; Bootstrap Sample Size-16; Class Weight-0.35. |

| DT | Maximum Depth-14; Impurity Criterion-MSE; Class Weight-0.25 |

| SDC | λ -0.458 along with the average target values for each class being 0.15 and 0.85 |

| MLP | Learning rate-0.45; Training Method-LM; Criterion-MSE. |

| BLDC | Mean and Covariance matrix , are calculated with a prior probability of 0.12; Convergence Criteria = MSE. |

| Performance Metrics | Equation | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy (%) | The overall accuracy of the classifier's predictions. | |

| Error Rate (%) | The ratio of misclassified instances. | |

| F1 Score (%) | The harmonic mean of precision and recall, reflecting the classification accuracy for a specific class. | |

| MCC | The Pearson correlation between the observed and predicted classifications. |

|

| Jaccard Index (%) | The proportion of predicted true positives to the sum of predicted true positives and actual positives, regardless of their true or predicted status. | |

| g-mean (%) | A metric combines sensitivity and specificity into a singular value balancing both objectives. | |

| Kappa | Evaluates how well the observed and predicted classifications align, reflecting the consistency of the classification outcomes. |

| DL model with Classifiers | Without Segmentation and FS | With Segmentation only | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy (%) |

Error Rate (%) |

F1 Score (%) |

MCC | Kappa | Jaccard Index (%) |

G-Mean (%) |

Accuracy (%) |

Error Rate (%) |

F1 Score (%) |

MCC | Kappa | Jaccard Index (%) |

G-Mean (%) |

|

| ResNet-50-SVM | 57.200 | 42.800 | 57.808 | 0.144 | 0.144 | 40.655 | 57.182 | 74.350 | 25.650 | 77.690 | 0.510 | 0.487 | 63.519 | 72.827 |

| ResNet-50-DT | 67.060 | 32.940 | 68.339 | 0.342 | 0.341 | 51.905 | 66.938 | 73.910 | 26.090 | 68.676 | 0.507 | 0.478 | 52.295 | 71.996 |

| ResNet-50-RF | 68.230 | 31.770 | 70.813 | 0.370 | 0.365 | 54.814 | 67.654 | 79.420 | 20.580 | 79.788 | 0.589 | 0.588 | 66.373 | 79.399 |

| ResNet-50-KNN | 65.540 | 34.460 | 63.611 | 0.313 | 0.311 | 46.640 | 65.325 | 72.790 | 27.210 | 76.492 | 0.480 | 0.456 | 61.933 | 71.066 |

| ResNet-50-SDC | 59.790 | 40.210 | 56.393 | 0.198 | 0.196 | 39.269 | 59.280 | 80.730 | 19.270 | 78.859 | 0.625 | 0.615 | 65.097 | 80.243 |

| ResNet-50-BLDC | 58.150 | 41.850 | 56.247 | 0.164 | 0.163 | 39.127 | 57.987 | 77.090 | 22.910 | 75.289 | 0.548 | 0.542 | 60.370 | 76.745 |

| ResNet-50-MLP | 58.700 | 41.300 | 59.310 | 0.174 | 0.174 | 42.157 | 58.681 | 81.250 | 18.750 | 82.353 | 0.630 | 0.625 | 70.000 | 81.009 |

| ResNet-101-SVM | 64.330 | 35.670 | 61.740 | 0.289 | 0.287 | 44.655 | 63.973 | 69.760 | 30.240 | 66.623 | 0.402 | 0.395 | 49.950 | 69.124 |

| ResNet-101-DT | 60.940 | 39.060 | 60.940 | 0.219 | 0.219 | 43.823 | 60.940 | 76.110 | 23.890 | 74.359 | 0.527 | 0.522 | 59.183 | 75.803 |

| ResNet-101-RF | 65.130 | 34.870 | 66.156 | 0.303 | 0.303 | 49.427 | 65.060 | 74.020 | 25.980 | 74.272 | 0.481 | 0.480 | 59.074 | 74.014 |

| ResNet-101-KNN | 67.969 | 32.031 | 69.630 | 0.362 | 0.359 | 53.409 | 67.748 | 80.980 | 19.020 | 80.930 | 0.620 | 0.620 | 67.969 | 80.980 |

| ResNet-101-SDC | 60.680 | 39.320 | 60.719 | 0.214 | 0.214 | 43.595 | 60.680 | 82.550 | 17.450 | 81.791 | 0.653 | 0.651 | 69.191 | 82.445 |

| ResNet-101-BLDC | 54.450 | 45.550 | 54.345 | 0.089 | 0.089 | 37.311 | 54.450 | 81.310 | 18.690 | 82.983 | 0.639 | 0.626 | 70.915 | 80.714 |

| ResNet-101-MLP | 60.530 | 39.470 | 60.605 | 0.211 | 0.211 | 43.477 | 60.530 | 84.120 | 15.880 | 81.797 | 0.706 | 0.682 | 69.201 | 83.147 |

| ResNet152-SVM | 61.360 | 38.640 | 64.790 | 0.232 | 0.227 | 47.918 | 60.582 | 74.480 | 25.520 | 72.470 | 0.495 | 0.490 | 56.826 | 74.121 |

| ResNet152-DT | 55.970 | 44.030 | 58.055 | 0.120 | 0.119 | 40.899 | 55.749 | 73.370 | 26.630 | 76.585 | 0.486 | 0.467 | 62.055 | 72.074 |

| ResNet152-RF | 63.670 | 36.330 | 62.849 | 0.274 | 0.273 | 45.825 | 63.632 | 80.070 | 19.930 | 78.563 | 0.607 | 0.601 | 64.694 | 79.761 |

| ResNet152-KNN | 66.270 | 33.730 | 69.914 | 0.335 | 0.325 | 53.744 | 65.154 | 81.510 | 18.490 | 83.525 | 0.650 | 0.630 | 71.711 | 80.587 |

| ResNet152-SDC | 67.550 | 32.450 | 61.465 | 0.370 | 0.351 | 44.368 | 65.679 | 82.090 | 17.910 | 79.728 | 0.660 | 0.642 | 66.290 | 81.259 |

| ResNet152-BLDC | 59.340 | 40.660 | 60.432 | 0.187 | 0.187 | 43.299 | 59.276 | 75.770 | 24.230 | 69.889 | 0.560 | 0.515 | 53.715 | 73.210 |

| ResNet152-MLP | 57.880 | 42.120 | 58.633 | 0.158 | 0.158 | 41.476 | 57.851 | 85.420 | 14.580 | 85.420 | 0.708 | 0.708 | 74.551 | 85.420 |

| ResNet-X-SVM | 56.780 | 43.220 | 56.892 | 0.136 | 0.136 | 39.755 | 56.779 | 73.300 | 26.700 | 71.160 | 0.471 | 0.466 | 55.231 | 72.924 |

| ResNet-X-DT | 60.020 | 39.980 | 61.617 | 0.201 | 0.200 | 44.526 | 59.876 | 76.690 | 23.310 | 76.100 | 0.535 | 0.534 | 61.420 | 76.650 |

| ResNet-X-RF | 64.800 | 35.200 | 63.942 | 0.296 | 0.296 | 46.996 | 64.756 | 77.580 | 22.420 | 74.523 | 0.568 | 0.552 | 59.391 | 76.646 |

| ResNet-X-KNN | 54.850 | 45.150 | 54.864 | 0.097 | 0.097 | 37.801 | 54.850 | 78.650 | 21.350 | 81.862 | 0.613 | 0.573 | 69.294 | 76.630 |

| ResNet-X-SDC | 68.930 | 31.070 | 69.756 | 0.379 | 0.379 | 53.558 | 68.876 | 83.850 | 16.150 | 82.916 | 0.681 | 0.677 | 70.817 | 83.671 |

| ResNet-X-BLDC | 61.060 | 38.940 | 62.851 | 0.222 | 0.221 | 45.826 | 60.870 | 72.550 | 27.450 | 77.154 | 0.493 | 0.451 | 62.805 | 69.696 |

| ResNet-X--MLP | 69.610 | 30.390 | 73.185 | 0.407 | 0.392 | 57.709 | 68.322 | 86.460 | 13.540 | 86.318 | 0.729 | 0.729 | 75.929 | 86.454 |

| DL model with Classifiers | With Segmentation and PSO FS | With Segmentation and RDO FS | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy (%) |

Error Rate (%) |

F1 Score (%) |

MCC | Kappa | Jaccard Index (%) |

G-Mean (%) |

Accuracy (%) |

Error Rate (%) |

F1 Score (%) |

MCC | Kappa | Jaccard Index (%) |

G-Mean (%) |

|

| ResNet-50-SVM | 90.110 | 9.890 | 90.111 | 0.802 | 0.802 | 82.002 | 90.110 | 89.840 | 10.160 | 89.253 | 0.802 | 0.797 | 80.592 | 89.674 |

| ResNet-50-DT | 91.290 | 8.710 | 91.301 | 0.826 | 0.826 | 83.995 | 91.290 | 90.630 | 9.370 | 90.061 | 0.818 | 0.813 | 81.918 | 90.449 |

| ResNet-50-RF | 93.110 | 6.890 | 93.225 | 0.863 | 0.862 | 87.309 | 93.095 | 91.140 | 8.860 | 90.904 | 0.824 | 0.823 | 83.324 | 91.103 |

| ResNet-50-KNN | 89.840 | 10.160 | 89.814 | 0.797 | 0.797 | 81.511 | 89.840 | 93.350 | 6.650 | 93.218 | 0.868 | 0.867 | 87.297 | 93.330 |

| ResNet-50-SDC | 93.750 | 6.250 | 94.060 | 0.880 | 0.875 | 88.785 | 93.605 | 93.750 | 6.250 | 94.000 | 0.878 | 0.875 | 88.680 | 93.657 |

| ResNet-50-BLDC | 87.100 | 12.900 | 86.484 | 0.745 | 0.742 | 76.186 | 86.981 | 90.880 | 9.120 | 91.043 | 0.818 | 0.818 | 83.559 | 90.862 |

| ResNet-50-MLP | 94.010 | 5.990 | 93.833 | 0.882 | 0.880 | 88.383 | 93.966 | 95.310 | 4.690 | 95.475 | 0.909 | 0.906 | 91.342 | 95.240 |

| ResNet-101-SVM | 89.960 | 10.040 | 89.895 | 0.799 | 0.799 | 81.645 | 89.958 | 90.760 | 9.240 | 89.935 | 0.826 | 0.815 | 81.710 | 90.389 |

| ResNet-101-DT | 90.620 | 9.380 | 90.717 | 0.813 | 0.812 | 83.010 | 90.614 | 91.670 | 8.330 | 92.083 | 0.838 | 0.833 | 85.327 | 91.522 |

| ResNet-101-RF | 91.670 | 8.330 | 91.015 | 0.842 | 0.833 | 83.512 | 91.380 | 93.350 | 6.650 | 93.218 | 0.868 | 0.867 | 87.297 | 93.330 |

| ResNet-101-KNN | 87.760 | 12.240 | 87.917 | 0.756 | 0.755 | 78.439 | 87.750 | 90.230 | 9.770 | 90.318 | 0.805 | 0.805 | 82.346 | 90.225 |

| ResNet-101-SDC | 93.490 | 6.510 | 93.188 | 0.873 | 0.870 | 87.245 | 93.385 | 97.130 | 2.870 | 97.182 | 0.943 | 0.943 | 94.518 | 97.113 |

| ResNet-101-BLDC | 90.360 | 9.640 | 90.385 | 0.807 | 0.807 | 82.457 | 90.360 | 89.320 | 10.680 | 89.457 | 0.787 | 0.786 | 80.925 | 89.311 |

| ResNet-101-MLP | 94.530 | 5.470 | 94.628 | 0.891 | 0.891 | 89.804 | 94.512 | 97.660 | 2.340 | 97.629 | 0.954 | 0.953 | 95.368 | 97.651 |

| ResNet152-SVM | 93.220 | 6.780 | 93.113 | 0.865 | 0.864 | 87.113 | 93.207 | 92.370 | 7.630 | 92.443 | 0.848 | 0.847 | 85.948 | 92.365 |

| ResNet152-DT | 90.110 | 9.890 | 90.737 | 0.810 | 0.802 | 83.045 | 89.855 | 92.570 | 7.430 | 92.482 | 0.852 | 0.851 | 86.015 | 92.563 |

| ResNet152-RF | 92.180 | 7.820 | 91.885 | 0.846 | 0.844 | 84.988 | 92.108 | 93.030 | 6.970 | 92.591 | 0.867 | 0.861 | 86.204 | 92.841 |

| ResNet152-KNN | 91.460 | 8.540 | 91.203 | 0.831 | 0.829 | 83.829 | 91.413 | 92.310 | 7.690 | 92.533 | 0.848 | 0.846 | 86.104 | 92.262 |

| ResNet152-SDC | 93.750 | 6.250 | 93.478 | 0.878 | 0.875 | 87.755 | 93.657 | 95.960 | 4.040 | 95.954 | 0.919 | 0.919 | 92.223 | 95.960 |

| ResNet152-BLDC | 93.230 | 6.770 | 93.011 | 0.866 | 0.865 | 86.936 | 93.177 | 86.710 | 13.290 | 85.863 | 0.740 | 0.734 | 75.228 | 86.503 |

| ResNet152-MLP | 94.520 | 5.480 | 94.477 | 0.891 | 0.890 | 89.532 | 94.517 | 96.350 | 3.650 | 96.369 | 0.927 | 0.927 | 92.993 | 96.349 |

| ResNet-X-SVM | 91.670 | 8.330 | 91.212 | 0.838 | 0.833 | 83.844 | 91.522 | 91.640 | 8.360 | 91.850 | 0.834 | 0.833 | 84.929 | 91.604 |

| ResNet-X-DT | 88.600 | 11.400 | 88.426 | 0.772 | 0.772 | 79.254 | 88.587 | 92.180 | 7.820 | 91.928 | 0.845 | 0.844 | 85.062 | 92.127 |

| ResNet-X-RF | 92.190 | 7.810 | 91.850 | 0.847 | 0.844 | 84.929 | 92.096 | 94.010 | 5.990 | 94.293 | 0.885 | 0.880 | 89.201 | 93.880 |

| ResNet-X-KNN | 91.660 | 8.340 | 91.830 | 0.834 | 0.833 | 84.894 | 91.636 | 93.220 | 6.780 | 93.425 | 0.866 | 0.864 | 87.662 | 93.168 |

| ResNet-X-SDC | 93.490 | 6.510 | 93.113 | 0.875 | 0.870 | 87.114 | 93.330 | 97.860 | 2.140 | 97.836 | 0.957 | 0.957 | 95.764 | 97.854 |

| ResNet-X-BLDC | 92.180 | 7.820 | 92.300 | 0.844 | 0.844 | 85.701 | 92.167 | 88.540 | 11.460 | 88.774 | 0.772 | 0.771 | 79.813 | 88.516 |

| ResNet-X--MLP | 96.490 | 3.510 | 96.476 | 0.930 | 0.930 | 93.192 | 96.489 | 98.680 | 1.320 | 98.670 | 0.974 | 0.974 | 97.375 | 98.677 |

| S No | Authors | Dataset Used | Classification Models | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jain DK et al., (2022) [41] | 1500 images from LZ2500 dataset | Kernel PCA combined with Faster Deep Belief Networks | 97.10% |

| 2 | Civit-Masot J et al., (2022) [42] | 15,000 images from LC25000 dataset | Custom Architecture with 3 Convolution and 2 dense layers | 99.69% with 50 epochs |

| 3 | Iftikhar Naseer et al., (2023) [43] | LUNA 16 Database |

LungNet-SVM | 97.64% |

| 4 | Wang et al., (2023) [44] | 993 WSIs from TCGA dataset | A novel multiplex-detection-based MIL model | 90.52% |

| 5 | Mehedi Masud et al., (2021) [45] | LC25000 dataset | Custom CNN architecture consisting of 3 Convolution and 1 FC layers | 96.33% |

| 6 | Radical Rakhman Wahid et al., (2023) [46] |

LC25000 Database | Customized CNN Model | 93.02% |

| 7 | Mingyang Liu et al., (2023) [47] | First Hospital of Jilin University - Dataset | MLP IN MLP | 95.31% |

| 8 | Gupta S et al., (2022) [48] | TCGA dataset | Deep CNN | 92% |

| 9 | Liu Y et al., (2022) [49] | 766 lung WSIs from First Hospital of Baiqiu’en and LC25000 dataset | SE-ResNet-50 with novel activation function CroRELU | 98.33% |

| 10 | Wang X et al., (2023) [50] | 988 samples with both CNV and histological data | LungDIG: Combination of InceptionV3 with MLP | 87.10% |

| 11 | Rekka, Mastouri. et al., (2021) [51] | LUNA16 Database (3186 CT images) |

BCNN [VGG16, VGG19] | 91.99% |

| 12 | Phankokkruad, M (2021) [52] | LC25000 Database | Ensemble ResNet50V2 |

91% 90% |

| 13 | Bukhari, S. et al., (2020) [53] | CRAG Dataset | ResNet-50 | 93.91% |

| 14 | Karthikeyan Shanmugam, Harikumar Rajaguru This Research |

LC25000 Database |

Feature Extraction – RDO TL model – EfficientNetB0 with MLP classifier |

98.698% |

| Deep Feature Extraction |

Classifiers | Without Segmentation | With Segmentation | With Segmentation and PSO Feature Selection | With Segmentation and RDO Feature Selection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet-50 | SVM | ||||

| DT | |||||

| RF | |||||

| KNN | |||||

| SDC | |||||

| BLDC | |||||

| MLP | |||||

| ResNet-101 | SVM | ||||

| DT | |||||

| RF | |||||

| KNN | |||||

| SDC | |||||

| BLDC | |||||

| MLP | |||||

| ResNet-152 | SVM | ||||

| DT | |||||

| RF | |||||

| KNN | |||||

| SDC | |||||

| BLDC | |||||

| MLP | |||||

| DWAFF - ResNet-X |

SVM | ||||

| DT | |||||

| RF | |||||

| KNN | |||||

| SDC | |||||

| BLDC | |||||

| MLP |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).