Submitted:

09 February 2025

Posted:

11 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. IDH Inhibitors

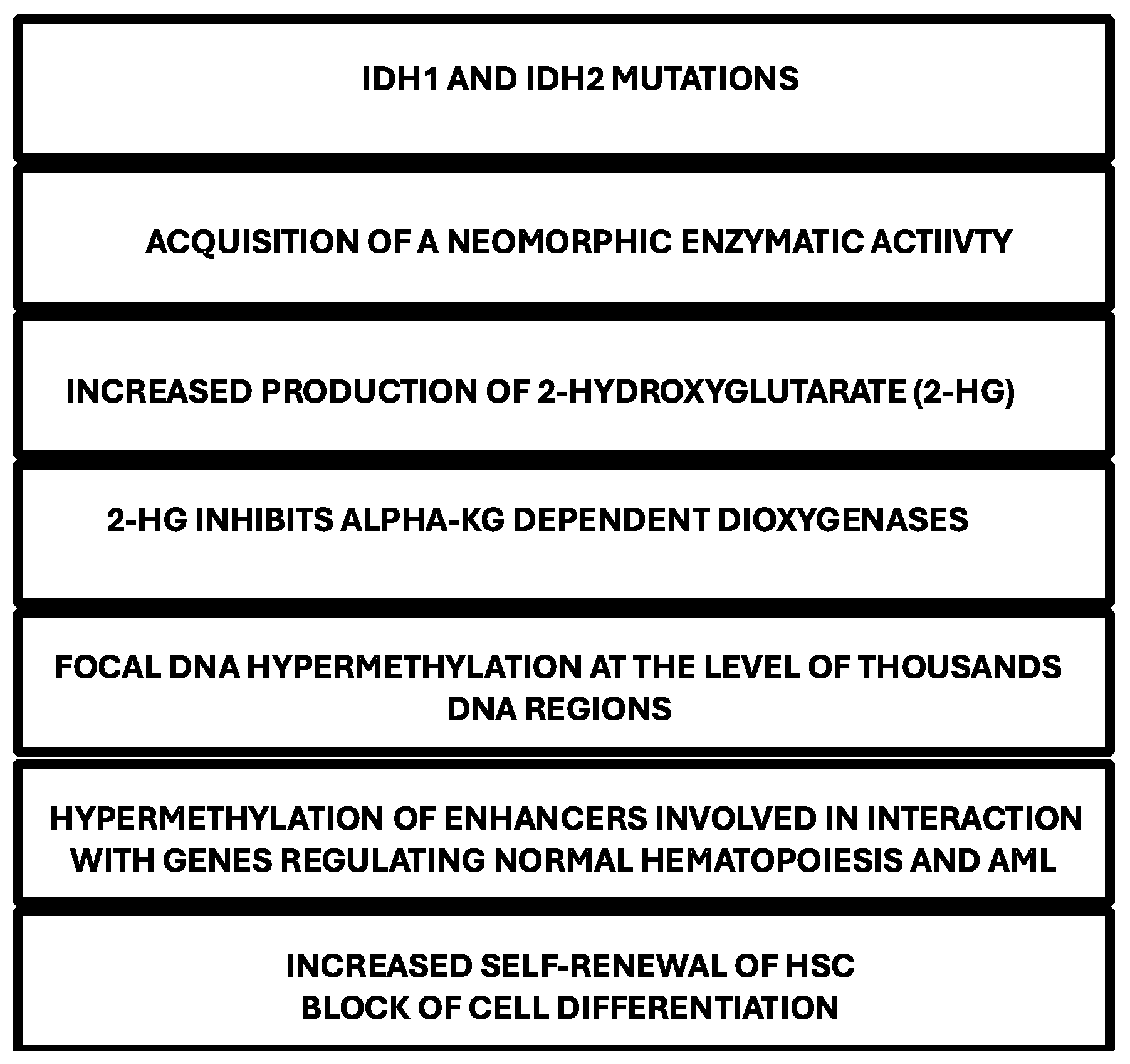

IDH Mutations and Cell Differentiation

IDH1 Inhibitors

IDH2 Inhibitors

Differentiation Syndrome in Patients Treated with IDH Inhibitors

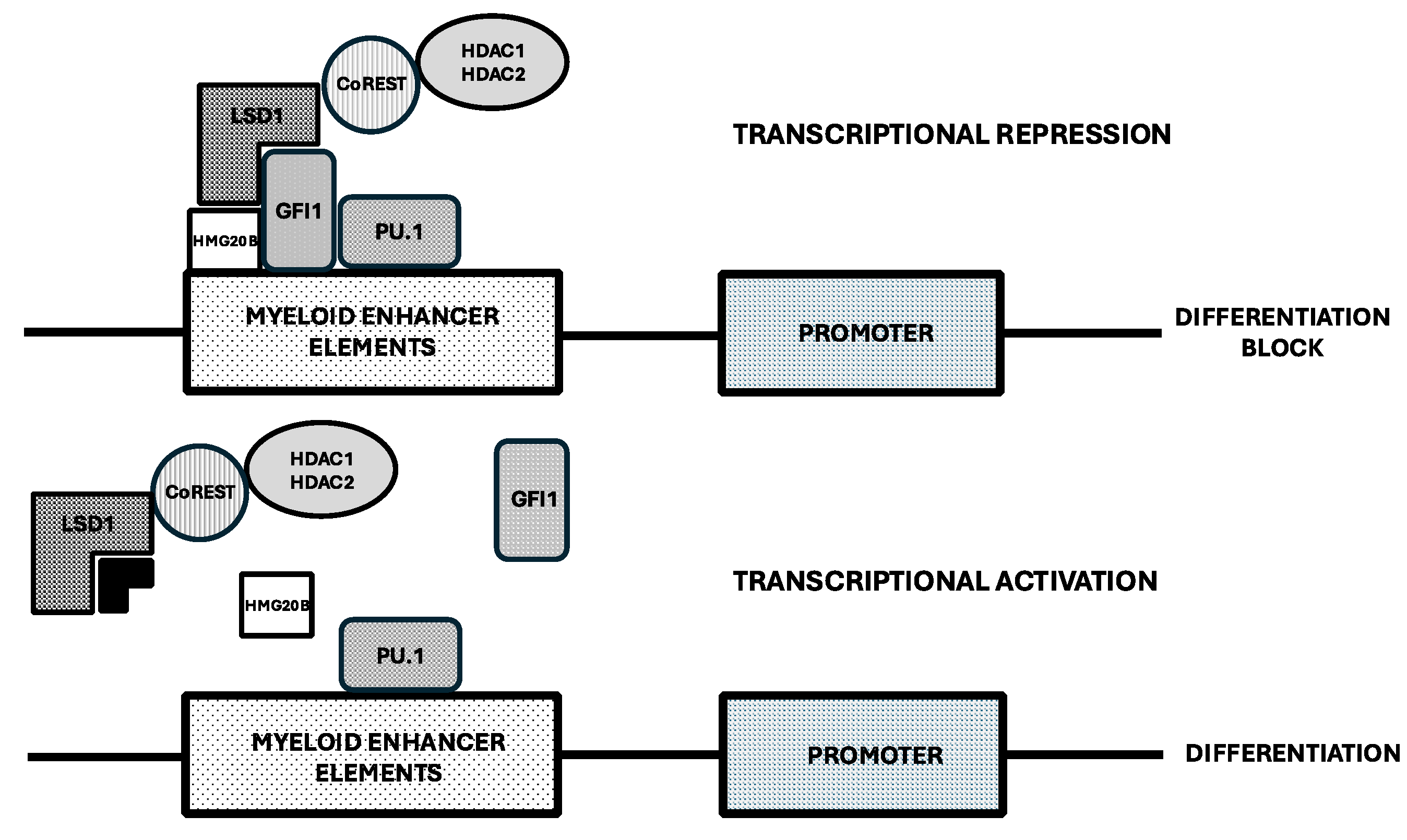

Inhibitors of Lysine-Specific Demethylase 1 (LSD1 or KMD1A)

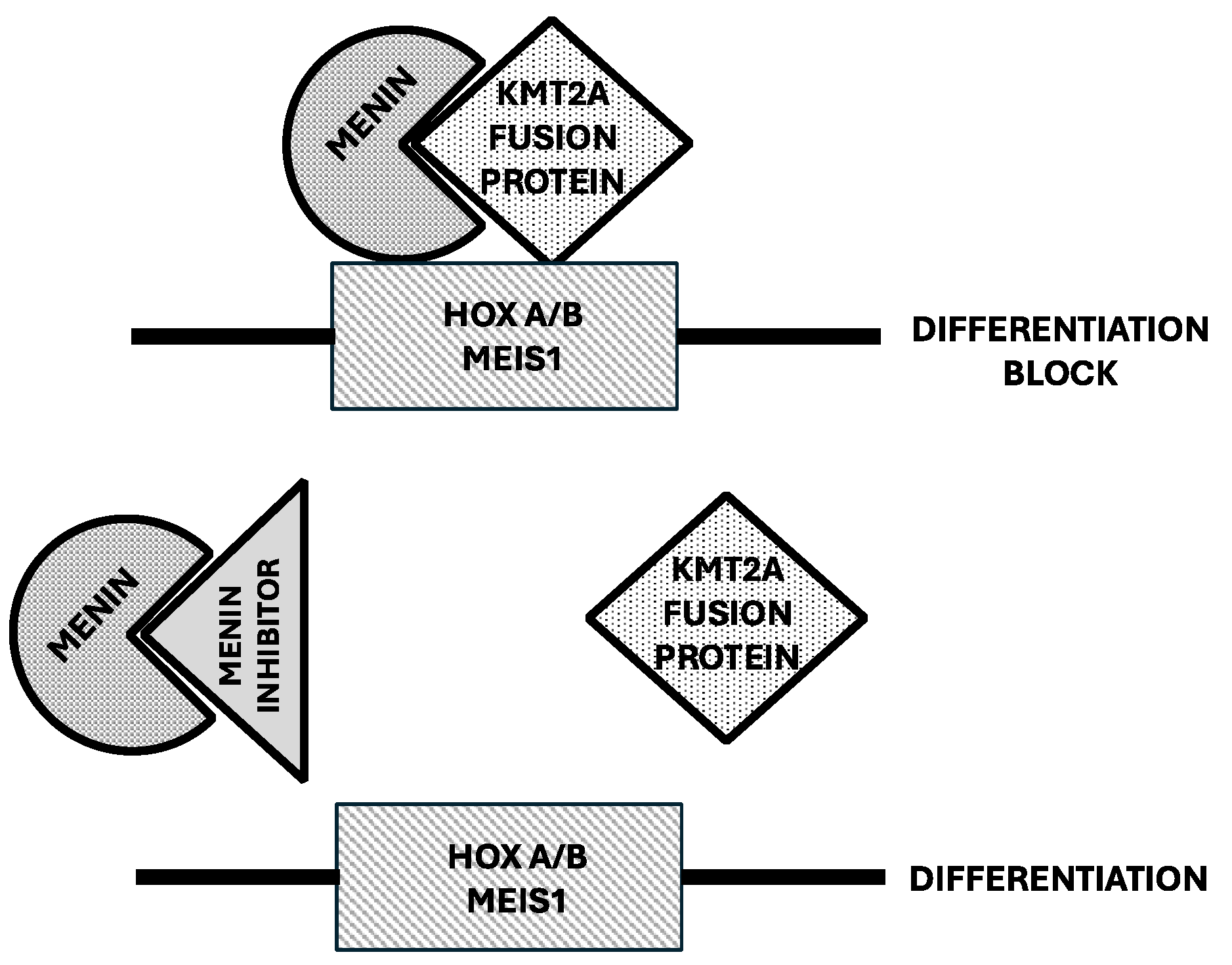

Menin Inhibitors in the Treatment of AML

| Compound | Revumenib | Bleximenib | Enzomenib | Ziftomenib |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | AUGMENT-101 Phase I/II |

CAMELOT-1 Phase I/II |

DSP-5336-101 Phase I/II |

KOMET-001Phase I/II |

| Number of patients | 161 | 21 | 40 | 58 |

| ORR | KMT2Ar 64% NPM1m 47% |

KMT2Ar 30% NPM1m 50% |

KMT2Ar 59% NPM1m 54% |

KMT2Ar 17% NPM1m 42% |

| CR+CRi | KMT2Ar 23% NPM1m 23% |

KMT2Ar 33% NPM1m 33% |

KMT2Ar 30% NPM1m 47% |

KMT2Ar 17% NPM1m 35% |

| MRD negativity(in CR+CRi) | KMT2Ar 58% NPM1m 64% |

NR | NR | KMT2Ar 100% NPM1m 63% |

| HSCT amongresponders | KMT2Ar 36% NPM1m 17% |

NR | NR | KMT2Ar 33% NPM1m 33% |

| DifferentiationSyndrome (%) | 22% | 19% | 11% | 11% |

Revumenib

Bleximenib

DSPP-5336 (Enzomenib)

KO-539 (Ziftomenib)

BMF-219 (Icovamenib)

3. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Breitman, T.R.; Colling, S.J.; Keene, B.R. Terminal differentiation of human promyelocytic leukemic cells in primary culture in response to retinoic acid. Blood 1981, 57, 100–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.E.; Ye, Y.C.; Chen, S.R.; Chai, J.R.; Lu, J.X.; Zhou, L.; Gu, L.J.; Wang, Z.Y. Use of all-trans retinoic acid in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 1988, 72, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degos, L.; Chomienne, C.; Daniel, M.T.; Berger, R.; Dombret, H.; Fenaux, P.; Castaigne, S. Treatment of rist relapse in acute promyelocytic leukemia with all-trans retinoic acid. Lancet 1990, 336, 1440–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castaigne, S.; Chomienne, C.; Daniel, M.T.; Ballerini, P.; Berger, R.; Fenaux, P.; Degos, L. All-trans retinoic acid as a differentiation therapy for acute promyelocytic leukemia, I: clinical results. Blood 1990, 76, 1704–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Thé, H.; Chomienne, C.; Lanotte, M.; Degos, L.; Dejan, A. The t(15;17) translocation of acute promyelocytic leukemia fuses the retinoic acid receptor alpha geneto a novel transcribed locus. Nature 1990, 347, 558–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grignani, F.; Ferrucci, P.F.; Testa, U.; Talamo, G.; Fagioli, M.; Alacalay, M.; Mencarelli, A.; Grignani, F.; Peschle, C.; Nicoletti, I.; et al. The acute promyelocytic leukemia-specific PML-RARα fusion protein inhibits differentiation and promotes survival of myeloid precursor cells. Cell 1993, 74, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo-Coco, F.; Avvisati, G.; Vignetti, M.; Thiede, C.; Orlando, S.M.; Iacobelli, S.; Ferrara, F.; fazzi, P.; Cicconi, L.; Di Bona, E.; et al. Retinoic acid and arsenic trioxide for acute promyelocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med 2013, 369, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, U.; Castelli, G.; Pelosi, E. Isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes and in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancers 2020, 12, 2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, F.W.

- Falini, B.; Spinelli, O.; Meggendorfer, M.; Martelli, M.P.; Bigerna, B.; Ascani, S.; Stein, H.; Rambaldi, A.; Haferlach, T. IDH1-R132 changes vary according to NPM1 and other mutations status in AML. Leukemia 2019, 33, 1043–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamegar-Lumley, S.; Alonzo, T.A.; Gerbing, R.B.; Othus, M.; Sun, Z.; Reis, R.E.; Wang, J.; Leonti, A.; Kutny, M.A.; et al. Characteristics and prognostic impact of IDH mutations in AML: a COG, SWOG and ECOG analysis. Blood Adv 2023, 7, 5941–5953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M.; Knobbe, C.B.; Munger, J.C.; Lind, E.F.; Brenner, D.; Brustle, A.; Harris, I.S.; Holmes, R.; Wakeham, A.; Heigth, J.; et al. IDH1(R132H) mutation increase murine hematopoietic progenitors and alters epigenetics. Nature 2012, 488, 656–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kats, L.M.; Reschke, M.; Taulli, R.; Pozdnyakova, O.; Buegess, K.; Bhagarva, P.; Straley, K.; Karnik, R.; Meissner, A.; Small, D.; et al. Proto-oncogenic role of mutant Idh2 in leukemia initiation and maintenance. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zheng, L.; Cheng, B.Y.L.; Sin, C.F.; Li, R.; Tsui, S.P.; Yi, X.; Ma, A.C.H.; he, B.L.; Leung, A.Y.H.; et al. Transgenic IDH2R172K and IDH2R140Q zebrafish model recapitulated features of human acute myeloid leukemia. Oncogene 2023, 42, 1272–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, M.E.; Abdel-Wahab, O.; Lu, C.; Ward, P.S.; Patel, J.; Shih, A.; Li, Y.; Bhagvat, N. , Vasannthakumar, A.; Fernandez, H.F.; et al. Leukemic Idh1 and Idh2 mutations result in a hypermethylation phenotype, disrupt Tet2 function, and impair hematopoietic differentiation. Cancer Cell 2010, 18, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Ward, P.S.; Kapoor, G.S.; Rohe, D.; Turcan, S.; Abdel-Wahab, O.; Edwards, C.R.; Khanin, R.; Figueroa, M.E.; Melnick, A.; Wellen, K.E. IDH mutation impais histohe demethylation and results in a block of cell differentiation. Nature 2012, 483, 474–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losman, J.A.; Looper, R.E.; Koivunen, P.; Lee, P.; Schneider, R.K.; McMahon, R.K.; Cowley, G.S.; Root, D.E.; Ebert, B.L.; Kaelin, W.G. 8R)-2-hydroxyglutarate is sufficient to promote leukemogenesis and its effects are reversible. Science 2013, 339, 1621–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Trafins, J.; DeLa Barre, B.; Penard-Lacronique, V.; Schalm, V.; Hansen, E.; Starley, K.; Kewrnytsky, A.; Liu, W.; Gliser, C.; et al. Targeted inhibition of mutant Idh2 in leukemnia cells induces cellular differentiation. Science 2013, 340, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierangeli, S.; Donnini, S.; Ciaurro, V.; Milano, F.; Cardinali, V.; Sciabolacci, S.; Cimino, G.; Gianfriddo, I.; Ranieri, R.; Cipriani, S.; et al. The leukemic isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) 1 / 2 mutations impair myeloid and erythroid cell differentiation of primary human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs). Cancers 2024, 16, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landberg, N.; Koehnke, T.; Nakauchi, Y.; Fan, A.; Linde, M.H.; Karigane, D.; Thomas, D.; Majeti, R. Targeting Idh1-mutated pre-leukemic hematopoietic stem cells in myeloid disease, including CCUS and AML. Blood 2022, 140, 2234–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landberg, N.; Koehnke, T.; Feng, Y.; Nakauchi, Y.; Fan, A.; Karigane, D.; Lim, K.; Sinha, R.; Malcovati, L.; et al. Idh1-mutant preleukemic hematopoietic stem cells can be eliminated by inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation. Blood Cancer Discov 2024, 5, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.R.; Helton, E.M.; Heath, S.E.; Fulton, S.R.; Payton, J.E.; Welch, J.S.; Walter, M.J.; Westervelt, P.; DiPersio, J.F.; Link, D.C.; et al. Focal disruption of DNA methylation dynamics at enhancers in IDH-Mutant AML cells. Leukemia 2022, 36, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popovici-Muller, J.; Lemieux, R.M.; Artin, E.; Saunders, J.O.; Salituro, F.G.; Travins, J.; Cianchetta, G.; Cai, Z.; Zhou, D.; Cui, D.; et al. Discovery of AG-120 (Ivosidenib): a first-in-class mutant IDH1 inhibitor for the treatment of IDH1 mutant cancers. ACS Med Chem Lett 2018, 9, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nardo, C.D.; Stein, E.M.; de Botton, S.; Roboz, J.K.; Altman, A.S.; Mims, A.S.; Swords, R.; Collins, R.H.; Mannis, G.N. , Pollyea, D.A.; et al. Durable remissions with ivodisenib in IDH1-mutated relapsed or refractory AML. N Engl J Med 2018, 378, 2386–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nardo, C.D.; Stein, E.M.; Pigneux, A.; Altman, J.K.; Collins, R.; Erba, E.P.; Watts, J.M.; Uy, G.L.; Winkler, T.; Wang, H.; et al. Outcomes of patients with IDH1-mutant relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia receiving ivosidenib who proceeded to hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Leukemia 2021, 35, 3278–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roboz, G.J.; DiNardo, C.D.; Stein, E.M.; de Botton, S.; Mims, A.S.; Prince, G.T.; Altman, J.K.; Arellano, M.L.; Donnellan, W.; Erba, H.P.; et al. Ivosidenib induces deep durable remissions in patients with newly diagnosed IDH1-mutant acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2020, 135, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesinos, P.; Recher, C.; Vives, S.; Zarzycha, E.; Wang, J.; Bertani, G.; Heuser, M.; Calado, R.T.; Schuh, A.C.; Yeh, S.P.; et al. Ivosidenib and azacitidine in IDH1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2022, 386, 1519–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marvin-Peek, J.; Garcia, J.S.; Borthakur, G.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Short, N.J.; Kadia, T.M.; Loghavi, S.; Masarova, L.; Daver, N. A phase Ib/II study of Ivosidenib ± Azacitidine in IDH1-mutated hematologic malignancies: a 2024 update. Blood 2024, 144 (suppl.1), 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, E.M.; DiNardo, C.D.; Fathi, A.T.; Mims, A.S.; Pratz, K.W.; Savona, M.R.; Stein, A.S.; Stone, R.M.; Winer, E.S.; et al. Ivosidenib or enasidenib combined with intensive chemotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed AML: a phase I study. Blood 2021, 137, 1792–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, E.F.; Pozdynakova, O.; Roshal, M.; Fathi, A.T.; Stein, E.M.; Ferrell, P.B.; Shaver, A.C.; Frattini, M.; Wang, H.; Hua, L.; et al. A novel differentiation response with combination IDH inhibitor and intensive induction therapy for AML. Blood Adv 2021, 5, 2279–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, A.T.; Kim, H.T.; Soiffer, R.J. ; Levis. M.J.; Li, S.; Kim, A.S; DeFilipp, Z.; El-Jewari, A.; MCAfee, S; Brunner, AM; et al. Multicenter phase I trial of ivosidenib as maintenance treatment following as maintenance treatment following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for IDH1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Cancer Res 2023, 29, 2034–2042. [Google Scholar]

- Choe, S.; Wang, H.; Di Nardo, C.D.; Stein, E.M.; de Botton, S.; Roboz, G.J.; Altman, J.K.; Mims, A.S.; Watts, J.M.; Pollyea, D.A.; et al. Molecular mechanisms mediating relapse following Ivosidenib monotherapy in IDH1-mutant relapsed or refractory AML. Blood Adv 2020, 4, 1894–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turkalj, S.; Stoilova, B.; Groom, A.J.; Radtke, F.E.; Mecklenbrauck, R.; Jakobsen, N.A.; Lachowiez, C.A.; Metzner, M.; Usukhbayar, B.; Salazar, M.A; et al. Clonal basis of resistance and response to ivosidenib combination therapies is established early during treatment in IDH1-mutated myeloid malignancies. Blood 2024, 144, 642–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caravella, J.A.; Lin, j.; Diebold, R.B.; Campbell, A.M.; Ericsson, A.; Gustafsson, G.; Wang, Z.; Castro, J.; Clarke, A.; Gofur, D.; et al. Structure-based design and identification of FT-2102 (Olutasidenib), a potent mutant-selective IDH1 inhibitor. J Med Chem 2020, 63, 1612–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Lu, W.; Caravella, J.A.; Campbell, A.M.; Diebold, FR.B.; Ericsson, A.; Fritzen, E.; Gustafson, G.R.; Lancia, D.R.; Shelekhin, T. Discovery and optimization of quinolone derivatives as potent, selective, and orally bioavailable mutant ioscitreate dehydrogenase 1 (mIDH1) inhibitors. J Med Chem 2019, 62, 6575–6592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, J.M.; Baer, M.R.; Yang, J.; Prebet, T.; Lee, S.; Schiller, G.J.; Dinner, S.N.; Pigneux, A.; Montesinos, P.; Wang, A.S.; et al. Olutasedinib alone or with azicitidine in IDH1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome: phase 1 results fo a phase 1-2 trial. Lancet Haematol 2023, 10, e46–e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Botton, S.; Fenaux, P.; Yee, K.; Récher, C.; Wei, A.H.; Montesinos, P.; Taussig, D.C.; Pigneux, A.; Braun, T.; Curti, A.; et al. Olutasedinib (FT-2102) induces durable complete remissions in patients with relapsed or refractory IDH1-muatted AML. Blood Adv 2023, 7, 3117–3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, J.E.; Jonas, B.A.; Watts, J.M.; Chao, M.M.; De Botton, S. Olutasidenib for mutated IDH1 acute myeloid leukemia: final five-year results from the phase 2 pivotal cohort. J Clin Oncol 2024, suppl 16, 6528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Botton, S.; Jonas, B.A.; Ferrell, B.; Choa, M.M.; Mims, A.S. Safety and efficacy of olutasidenib treatment in elderly patients with relapsed/refractory mIDH1 acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2024, 42, suppl–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, J.E.; Esteve, J.; Bajel, A.; Yee, K.; Braun, T.; De Botton, S.; Peterlin, P.; Recher, C.; Thomas, X.; Watts, J.; et al. Olutasidenib (FT-2102) in combination with azacitidine induces durable complete remissions in patients with mIDH1 acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2021, 138, 698–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, J.E.; Roboz, G.J.; Watts, J.; Baer, M.R.; Jonas, B.A.; Schiller, G.J.; Yee, K.; Ferrell, B.; Yang, J.; Wang, E.S.; et al. Combination of olutasidenib and azacitidine induces durable complete remissions in mIDH1 acute myeloid leukemia: a multicohort open-label phase ½ trial. Blood 2024, 144 (suppl.1), 2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNardo, C.D.; Chien, K.S.; Mullin, J.; Hammond, D.; Ramdial, J.; Kadia, T.M.; Haddad, F.G.; Yilmaz, M.; Sasaki, K.; Issa, G.C.; et al. Phase ½ study of decitabine and venetoclax in combination with the targeted mutant IDH1 inhibitor olutasidenib for patients with relapsed/refractory AML, high risk MDS, or newly diagnosed AML not eligible for chemotherapy with an IDH1 mutation. Blood 2024, 144 (suppl.1), 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.E.; Leahy, T.P.; Turner, A.; Thomassen, A.; Wang, L.; Sheppard, A.; Cortes, J.E. Effectiveness of olutasidenib versus ivosidenib in patients with mutated isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 acute myeloid leukemia who are relapsed or refractory to venetoclax: the 2102-HEM-101 trial versus a US electronic health record-based external control arm. Blood 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, J.M.; Shaw, S.J.; Jona, B.A. Looking beyond the surface: olutasidenib and ivosidenib for treatment of mIDH1 acute myeloid leukemia. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2024, 25, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, K.; Travens, J.; Wang, F.; David, M.D.; Artin, E.; Straley, K.; Padyana, A.; Gross, S.; DeLa Barre, B.; Tobin, E.; et al. AG-221, a first-in-class therapy targeting acute myeloid leukemia harboring oncogenic IDH2 mutations. Cancer Discover. 2017, 7, 478–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, E.M.; Di Nardo, C.D.; Pollyea, D.A.; Fathi, A.T.; Roboz, G.J.; Altman, J.K.; Stone, R.M.; De Angelo, D.J.; Levine, R.L.; Finn, J.W.; et al. Enasidenib in mutant IDH2 relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2017, 130, 722–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollyea, D.A.; Tallman, M.S.; De Botton, S.; Komborjian, A.M.; Collins, R.; Stein, A.S.; Frattini, M.G.; Xu, Q.; Tosolini, A.; See, W.L.; et al. Enasidenib, an inhibitor of mutant IDH2 proteins, induces durable remissions in older patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2019, 33, 2575–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amatangelo, M.D.; Quek, L.; Shih, A.; Stein, E.M.; Roshal, M.; David, M.D.; Marteyn, B.; Farnoud, N.R.; de Botton, S.; Bernard, O.A.; et al. Enasidenib induces acute myeloid leukemia cell differentiation to promote clinical response. Blood 2017, 130, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Botton, S.; Montesinos, P.; Schuh, A.C.; Papayannidis, C.; Vyes, P.; Wei, A.H.; Ommen, H.; Semochkin, S.; Kim, H.J.; Lrsom, R.A.; et al. Enasidenib versus conventional care in older patients with late-stage mutant IDH2-relapsed/refractory AML: a randomized phase 3 trial. Blood 2023, 141, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNardo, C.D.; Schuh, A.C.; Stein, E.M.; Montesinos, P.; Wei, A.H.; de Botton, S.; Ziedan, A.M.; Fathi, A.T.; Kantarjian, H.M.; Bennett, J.M.; et al. Enasidenib plus azacitidine versus azacitidine alone in patients with newly diagnosed, mutant-IDH2 acute myeloid leukemia (AG221-AML-005): a single-arm, phase 1b and randomized, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2021, 22, 1597–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.F.; Huang, Y.; Lance, J.R.; Mao, H.C.; Dunbar, A.J.; McNulty, S.N.; Druley, T.; Li, Y.; Baer, M.R.; Stock, W.; et al. A study to assess the efficacy of enasidenib and risk-adapted addition of azacitidine in newly diagnosed IDH2-mutant AML. Blood Adv 2024, 8, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard-Carpentier, G.; Gupta, G.; Cameron, C.; Chatelin, S.; Bankar, A.; Davidson, M.B.; Gupta, V.; Maze, D.C.; Minden, M.D.; et al. Final results of the phase Ib/II study evaluating enasidenib in combination with venetoclax in patients with IDH2-mutated relapsed/refractory myeloid malignancies. Blood 2023, 142 (suppl.1), 159–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salhotra, A.; Bejanyan, N.; Yang, D. Multicenter pilot clinical triasl of enasidenib as maintenance therapy after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT) in patienys with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) carrying IDH2 mutations. Transplantation and Cellular Therapies Meeting 2024, Sant Antonio, Texas, USA, abst 10.

- Ball, B.J.; Zhang, J.; Afkhami, M.; Robbins, M.; Chang, L.; Humpal, S.; Porras, V.; Liu, Y.; Synold, T.; Farzinkhou, S.; et al. Study of IDH inhibition with Enasidenib and MEK inhibition with Cobimetinib in patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia who have co-occurring IDH2 and RAS signling gene mutations. Blood 2024, 144 (suppl.1), 6043–6044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebert, M.; Chevrer, S.; Dimicoli-Salazar, S.; Cluzeau, T.; Rauzy, O.; Bastard, A.S.; Lribi, K.; Fosard, G.; Thépot, S.; Gloaguen, S.; et al. Enasidenib (ENA) monotherapy in patients with IDH2 muatted myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), the ideal phase 2 study by the GFM and Emsco groups. Blood 2024, 144, 1839–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesinos, P.; Bergua, J.M.; Vellenga, E.; Rayon, C.; Parody, R.; de la Serna, J.; Leon, A.; Esteve, J.; Milone, G.; Debén, G.; et al. Differentiation syndrome in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with all-trans retinoic acid and anthracycline chemotherapy: characteristics, outcome, and prognostic factors. Blood 2009, 113, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luesink, M.; Pennings, J.; Wissink, W.; Linssen, P.; Muus, P.; mPfundt, R.; de Witte, T.; van der Reijden, B.; Jansen, J.H. Chemokine induction by all-trans retinoic acid and arsenic trioxide in acute promyelocytic leukemia: triggering the differentiation syndrome. Blood 2009, 114, 5512–5521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz, M.; Montesinos, P. How we prevent and treat differentiation syndrome in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 2014, 123, 2777–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, A.T.; DiNardo, C.D.; Kline, I.; Kenvin, L.; Gupta, I.; Attar, E.C.; Stein, E.M.; de Botton, S.; AG221-C-001 Study Investigators. Differentiation syndrome associated with enasidenib, a selective inhibitor of mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase 2: analysis of a phase 1-2 study. JAMA Oncol 2018, 4, 1106–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosworthy, K.J.; Mulkey, F.; Scott, E.C.; Ward, A.F.; Przepiorka, D.; Charlab, R.; Dorff, S.E.; Deisseroth, A.; Kazandjian, D.; Sridhara, R.; et al. Differentiation syndrome with ivosidenib and enasidenib treatment in patients with relapsed or refractory IDH-mutated AML: a U.S. food and drug administration systematic analysis. S. food and drug administration systematic analysis. Clin Cancer Res 2020, 26, 4280–4288. [Google Scholar]

- Montesinos, P.; Fathi, A.T.; de Botton, S.; Stein, E.M.; Zeidan, A.M.; Zhu, Y.; Prtebet, T.; Vigil, C.E.; Bluemmert, I.; Yu, X.; et al. Differentiation syndrome associated with treatment with IDH2 inhibitor enasidenib: pooled analysis from clinical trials. Blood Adv 2024, 6, 2509–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacilotto, N.; Dessanti, P.; Lufino, M.M.P.; Ortega, A.; Rodriguiez-Gimeno, A.; Salas, J.; Maes, T.; Bues, C.; Mascarò, C.; Soliva, R. Comprehensive in vitro characterization of the LSD1 small molecule inhibitor class in oncology. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci 2021, 4, 1818–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baby, S.; Shinde, S.D.; Kulkarni, N.; Sahu, B. Lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1) inhibitors: peptides as emerging class of therapeutics. ACS Chem Biol 2023, 18, 2144–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprussel, A.; Schulte, J.H.; Weber, S.; Necke, M.; Handschke, K.; Thor, T.; Pajtler, K.W.; Schramm, A.; Konig, K.; Diehl, L.; et al. Lysine-specific demethylase 1 restricts hematopoietic progenitor proliferation and is essential for terminal differentiation. Leukemia 2012, 26, 2039–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.T.; Spence, G.J.; Harris, W.J.; Maiques-Diaz, A.; Ciceri, F.; Huang, X.; Somervaille, T. ; Pharmacological inhibitors of LSD1 promote differentiation of myeloid leukemia cells through a mechanism independent of histone demethylation. Blood Adv 2014, 124 (suppl.1), 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiques-Diaz, A.; Spencer, G.J.; Lynch, J.T.; Ciceri, F.; Williams, E.L.; Amaral, F.; Wiseman, D.H.; Harris, W.J.; Li, Y.; Sahoo, S.; et al. Enhancer activation by pharmacologic displacement of LSD1 from GFI1 induces differentiation in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell Rep 2018, 22, 3641–3659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, J.; Abou-El-Ardat, K.; Dalic, D.; Kurrle, N.; Maier, A.M.; Mohr, S.; Schutte, J.; Vassen, L.; Greve, G.; Schulz-Fincke, J.; et al. Lsd1 inhibition by tranylcypromine derivatives interferes with GFI1.mediated repression of PU.1 target genes and induces differentiation in AML. mediated repression of PU.1 target genes and induces differentiation in AML. Leukemia 2019, 33, 1411–1426. [Google Scholar]

- Cusan, M.; Cai, S.F.; Mohammad, H.P.; Krivstov, A.; Chramiec, A.; Loizou, E. LSD1 inhibition exerts in antileukemic effect by recommissioning PU.1 and C/EBPα-dependent enhancers in AML. Blood 2018, 131, 1730–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiques-Diaz, A.; Nicosia, L.; Bosma, N.J.; Romero-Camarero, I.; Camera, F.; Spencer, G.J.; Amad, F.; Sineom, F.; Wingelhafer, B.; Williamson, A.; et al. HMG20B stabilizes association of LSD1 with GFI1 on chromatin to confer transcription repression and leukemia differentiation block. Oncogene 2022, 44, 4841–4854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleque, S.; Kim, J.; Rooke, H.M.; Orkin, S.H. Epigenetic regulation of hematopoietic differentiation by GFI1 and GFI1B is mediated by the cofactors CoREST and LSD1. Mol Cell 2007, 27, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moroy, T.; Vassen, L. , Wilkes, B.; Khandanpour, C. From cytopenia to leukemia. The role of GFI1 and GFI1B in blood formation. Blood 2015, 126, 2561–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterbury, A.L.; Kwok, H.S.; Lee, C.; Narducci, D.N.; Freedy, A.M.; Su, C.; Raval, S.; Reiter, A.H.; Hawkins, W.; Lee, K. An autoinhibitory switch of the LSD1 disordered region controls enhancer silencing. Mol Cell 2024, 84, 2238–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, T.; Mascarò, C.; Tirapu, I.; Estiarte, A.; Ciceri, F.; Lunardi, S.; Guibourt, N.; Perdone, A.; Lufino, M.M.; Somervaille, T.; et al. ORY-1001, a potent and selective covalent KMD1A inhibitor, for the treatment of acute leukemia. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salamero, O.; Montesinos, P.; Willekens, C.; Perez-Simon, J.A.; Pigneux, A.; Rècher, C.; Popat, R.; Carpo, C.; Molinero, C.; Mascaro, C.; et al. First-in-human phase I study of Iadademstat (ORY-1001): a first-in-class lysine-specific histone demethylase 1A inhibitor, in relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2020, 38, 4260–4273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salamero, O.; Molero, A.; Perez-Simon, J.A.; Arnan, M.; Cokli, R.; Garcia-Avila, S.; Acuna-Criz, E.; Cano, I.; Somervaille, T.; Gutierrez, S.; et al. Iadademstat in combination with azacitidine in patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (ALICE): an open-label, phase 2a dose-finding study. Lancet Hematol 2024, 2024. 11, e487–e498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, A.; Braun, T.P.; Abinder, A.J.; Borthakur, G.; Redner, R.L.; Arevalo, M.; Gutierrez, S.; Limon, A.; Faller, D.V. Iadademstat and gilteritinib for the treatment of FLT3-mutated relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia: the Frida study. Blood 2023, 142 (suppl.1), 5974–5975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, A.; Braun, T.P.; Abinder, A.J.; Palmisano, N.; Khurana, S.; Strickland, S.; Murthy, G.; Venugopal, S.; Feld, J.; Sanchez, E.; et al. Preliminary results of the FRIDA study: iadademstat and gilteritinib in FLT3-mutated R/R AML. EHA 2024.

- Brunett, L.; Gundry, M.C.; Sorcini, D.; Guzman, A.G.; Huang, Y.H.; Ramabradan, R.; et al. Mutant NPM1 maintains the leukemic state through HOX expression. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uckelmann, H.J.; Haaer, E.L.; Takeda, R.; Wong, E.M.; Hatton, C.; Marinaccio, C.; et al. Mutant NPM1 directly regulates oncogenic transcription in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Discov 2023, 13, 746–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Q.D.; Fan, D.; Han, Q.; Liu, Y.; Miao, H.; Wang, X.; et al. Mutant NPM1 hiajcacks transcriptional hubs to maintain pathogenic gene programs in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Discov 2023, 13, 724–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Amin, M.A.; Eklund, E.A.; Gartel, A.L. Regulation of HOX gene expression in AML. Blood Cancer J 2024, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, Y.; Reynold, M.; Williams, N.D.; Kawashima, N.; Bravo-Perez, C.; Guarnera, L.; Haddad, C.; Mandala, A.; Guarnari, C.; Durmaz, A.; et al. Genomic analyses unveil the pahtogenesis and inform on therapeutic targeting in KMT2A-PTD AML. Blood 2023, 142 (suppl.1), 5696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, A.; Somervaille, T.C.P.; Smith, K.S.; et al. The menin tumor suppressor protein is an essential oncogenic cofactor for MLL-associated leukemogenesis. Cell 2005, 123, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, L.K.; Peplinski, J.H.; Ries, R.E.; Kirkey, D.C.; Meshinchi, S. The AML HOX-ome: the landscape of developmental transcription factors across pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2024, 144 (suppl.1), 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klossowski, S.; Miao, H.; Kempinska, K.; Wu, T.; Purohit, T.; Kim, E.; Linhares, B.; Chen, D.; Jih, G.; Perkey, E.; Huang, H.; et al. Menin inhibitor MI-3454 induces remission in MLL1-rearranged and NPM1-mutated models of leukemia. J Clin Invest 2020, 130, 981–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto-Feliciano, Y.; Sanchez-Rovera, F.; Perner, F.; Barrows, D.; Kastenhuber, E.; Ho, Y.J.; Carool, T.; Xiong, Y.; Aand, D.; Soshnev, A.A.; et al. A molecular switch between mammalian MLL complexes dictates response to menin-MLL inhibition. Cancer Discov 2023, 13, 146–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciaurro, V.; Skwarska, A.; Daver, N.; Konopleva, M. .; Menin inhibtor DS-1594b drives differentiation and induces synergistic lethality in combination with venetoclax in AML cells with MLL-rearranged and NPM1 mutation. Blood 2022, 140 (suppl.1), 3082–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa,.C.; Aldoss, I.; DiPersio, J.; Cuglievan, B.; Stone, R.; Arellano, M.; Thirman, M.J.; Patel, M.R.; Dickens, D.S.; Shenoy, S.; t al. The menin inhibitor revumenib in KMT2A-rearraned or NPM1-mutant leukemia. Nature 2023, 615, 920–926.

- Muftuoglu, M.; Basyal, M. ; Ayoub,nE.; Lv, J.; Bedoy, A.; Patsilevas, T.; Bidikian, A., Issa, G.S.; Andreef, M. Single-cell proteome analysis reveal menin inhibition-induced proteomic alterations in AML patients treated with Revumenib. Blood 2023, 142, 2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, G.C.; Aldoss, I.; Thirman, M.J.; DiPersio, J.; Arellano, M.; Blachly, J.S.; Mannis, G.N.; Perl, A.; Dickens, D.S.; McMahon, C.M.; et al. Menin inhibition with Revumenib for KMT2A-rearranged relapsed or refractory acue leukemia (AUGMANY-101). J Clin Oncol 2024, 43, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldoss, I.; Issa, G.C.; Blachly, J.; Thirman, M.J.; Mannis, G.N.; Arellano, M.; DiPersio, J.; Traer, E. , Zwaan, M.; Shukla, N.; et al. updated results and longer follow-up from AUGMENT-101 phase 2 study of remuvenib in all patients with relapsed or refractor (R/R) KMT2A-Ar acute leukemia. Blood 2024, 144, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syndax Pharmaceuticals announced pivotal topline results from relapsed or refractory AML cohort in AUGMAENT-101 trial of revumenib. Nes release. Syndax Pharmaceuticals. November 12, 2024.

- Loo, S.; Iland, H.; Tiong, I.S.; Westerman, D.; Othman, J.; Masrlton, P.; Chua, C.C.; Putill, D.; Rose, H.; Fleming, S.; et al. Revumenib as pre-emptive therapy for measurable residual disease in NPM1 mutated or KMT2A-rearranged acute myeloid leukemia: a domain of the multi-arm ALLG AMLM26 intercept platform trial. Blood 2024, 144, 223–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, G.C.; Cuglievan, B.; Daver, N.; DiNardo, C.; Farhat, A.; Short, N.J.; McCall, D.; Pike, A.; Tan, S.; Kamerer, B.; et al. Phase I/II stud of the all-oral combination of remivenib (SNDX-5613) with decitabine/cedazuridine (ASTX727) and venetoclax (SAVE) in R/R AML. Blood 2024, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidegger, N.; Alexa, G.; Khalid, D.; Ries, R.E.; Wang, J.; Alonzo, T.A.; Perr, J.; Armstrong, S.A.; Meshinchi, S.; Pikman, Y.; et al. Combining menin and MEK inhibition to target poor prognostic KMT”A-rearranged RAS pathway-mutant acute leukemia. Blood 2023, 142 (suppl.1), 166–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perner, F.; Stein, E.M.; Wenge, D.V.; Singh, S.; Kim, J.; Apazidis, A.; Rahnamoun, H.; Anand, D.; Marinaccio, C.; Hatton, C.; et al. MEN1 mutations mediate clinical resistance to menin inhibition, Nature 2023, 615, 913-919.

- Perner, F.; Cai, S.F. .; Wenge, D.V.; Kim, J.; Cutler, J.; Nowak, R.; Cassel, J.; Singh, S.; Bijpuria, S.; Miller, W.H.; et al. Characterization of acquired resistance mutations to Menin inhibitors. Cancer Res 2023, 83 (suppl. 7), 3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, J.; Clegg, B.; Grembecka, J.; Cierpicki, T. Drug-resistant menin variants retain high binding affinity and interactions with MLL1. J Biol Chem 2024, 300, 107777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, M.C.; Thuring, J.W.; Querolle, O.; Dai, X.; Verhulst, T.; Pande, V.; Marien, A.; Goffin, D.; Wenge, D.V.; Yue, H.; et al. Preclinical efficacy of the potent, selective menin-KMT2A inhibitor JNJ-75276617 (bleximenib) in KMT2A- and NPM1-altered leukemias. Blood 2024, 144, 1206–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabbour, E.; Searle, E.; Abdul-Hay, M.; Abedin, S.; Aldoss, I.; Pierola, A.A.; Alonso-Dominguez, j.M.; Chevallier, P.; Cost, C.; Diskalakis, N.; et al. A first-in-human phase 1 stud of the menin-KMT2A (MLL-1) inhibitor JNJ-75276617 in adult patients relapsed/refractory acute leukemia harboring KMT2A or NPM1 alterations. Blood 2023, 142 (suppl.1), 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, E.; Recher, C. ; Abdul, Hay, M.; Abedin, S.; Aldoss, I.; Pierole, A.; Aolnso-Dominguiez, J.; Chevallier, P.; Cost, C.; Daskalakis, N.; et al. Bleximenib dose optimization and determination of RP2D from a phase 1 stud in relapsed/refractor acute leukemia patients with KMt2A and NPM1 alterations. Blood 2024, 144, 212. [Google Scholar]

- Recher, C.; O’Nions, J.; Aldoss, I.; Pierola, A.A.; Allred, A.; Alonso-Dominguez, J.M.; Barreyro, L.; Bories, P.; Curtis, M.; Daskalakis, N.; et al. Phase Ib study of menin-KMT2A inhibitor Blixemenib in combination with intensive chemotherapy in newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia with KMT2A or NPM1 alterations. Blood 2024, 144 (suppl.1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, A.H.; Searle, E.; Aldoss, I.; Alfonso-Pierole, A.; Alonso-Dominguez, J.M.; Curtis, M.; Dsakalakis, N.; Della Porta, M.; Dohner, H.; D’Souza, A.; Dugan, J.P.; et al. A phase 1B study of the menin-KMT2A inhibitor JNJ-75276617 in combination with venetoclax and azacytidine in relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemic with alterations in KMT2A or NPM1. EHA Meeting 2024, abst S133.

- Hogeling, S.M.; Le, D.M.; La Rose, N.; Kwon, M.C.; Wierenga, A.; van den Heuvei, F.; van den Boom, V.; Kucknio, A.; Philippar, U.; Huls, G.; et al. Bleximinab, the novel menin-KMT2A inhibitor JNJ-75276617, impairs long-term proliferation and immune evasion in acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica, 2025, in press.

- Collins, C.; Wang, J.; Miao, H.; Bronstein, J.; Nawer, H.; Xu, T.; Figueroa, M.; Muntean, A.; Hess, J.L. C/ERBPα is an essential collaborator in Hoxa9/Meis1-mediated leukemogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014, 111, 9899–9904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, L.; Heyes, E.; Scheiblecker, L; Eder, T.; Volpe, G.; Frampton, J.; Nerlov, C.; Valent, P.; Germbecka, J.; Grebien, F. Leukemia 2019, 33, 1608-1619.

- Eguchi, K.; Shimizu, T.; Kato, D. ; Furuta,.; Kamioka, S.; Ban, H.; Ymamoto, S.; Yokoyama, A.; Kitabaayshi, I. Preclinical evaluation of a novel orally bioavailable menin-MLL interaction inhibitor, DSP-5336, for the treatment of acute leukemia patients with MLL-rearrangement of NPM1 mutation. Blood 2021, 138, 3339. [Google Scholar]

- Daver, N.; Zeidner, J.F.; Yuda, J.; Watts, J.M.; Levis, M.J.; Fukushima, K.; Ikezoe, T.; Ogawa, .; Brandwein, J.; Wang, E.S.; et al. phase 1-2 first-in-human study of the menin-MLL inhibitor DSP-5336 in patients with relapsed or refractory acue leukemia. Blood 2023, 142 (suppl.1), 2911. [CrossRef]

- Zeidner, J.F.; Yuda, J.; Watts, J.M. , Levis, M.J.; Erba, H.P.; Fukushima, K.; Shaima, T.; Palmisano, N.D.; Wang, E.S.; borate, U-; et al. Phase 1 results: first-in-human phase 1-2 study of the menin-MLL inhibitor enzomenib (DSP-5336) in patients with relapsed or refractor acute leukemia. Blood 2024, 144, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisku, W.; Daver, N.; Boettcher, S.; Mill, C.P.; Sasaki, K.; Bindwell, C.E.; Davis, J.A.; Das, K. , Takashi, K.; Kadia, T.M.; et al. Activity of menin inhibitor zitfomenib (KO-539) as monotherapy or in combinations against AML cells with MLL1 rearrangement or mutant NPM1. Leukemia 2022, 36, 2729–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauch, J.; Dzama, M.M. ; Dolgikh, N:; Stiller, H.; Bohl, S.; Lahrmann, C.; Kunz, K.; Kessler, L.; Echannoni, H.; Chei, C.W.; et al. Menin inhibitor ziftomeninb (KO-539) synergizes with drugs targeting chromatin regulation or apoptosis and sensitizes acute myeloid leukemia with MLL rearrangement or NPM1 mutation to venetoclax. Haematologica 2023, 108, 2837–2847. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, E.S.; Issa, G.C.; Erba, H.P.; Altman, J.K.; Montesinos, P.; DeBotton, S.; Walter, R.B.; Pettit, K.; Savona, M.R.; Shah, M.V.; et al. Ziftomenib in relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia (KOPMET-001): a multicenter, open-label, multi-cohort, phase I trial. Lancet Oncol 2024, 25, 1310–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, A.M.; Wang, E.S.; Issa, G.C.; Altman, J.; Balasubramianan, S.K.; Strickland, S.A.; Roboz, G.J.; Schiller, G.J.; McMahon, C.M.; Palmisano, N.D.; et al. Ziftomenib combined with intensive induction (7+3) in newly diagnosed NPM1-m or KMTY2A-r acute myeloid leukemia: interim phase 1a results from KOMET-007. Blood 2024, 144 (suppl.1), 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golobberg, A.D.; Corun, D.; Ahsan, J.; Nie, K.; Koziek, T.; Leoni, M.; Dale, S. Kamet-008: a phase 1 study to determine the safety and tolerability of Ziftomernib combinations for the treatment of KMT2A-rearranged or NPM1-mutant relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2023, 142 (suppl.1), 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancet, J.; Ravandi, F.; Montesinos, P.; Barrientos, J.C.; Badar, T.; Alegre, A.; Bashey, A.; Bergua Bugues, J.M.; et al. Covalent menin inhibitor Bmf-219 in patients with relapsed or refractory (R/R) leukemia (AL): preliminary phase 1 data from the Covalent-101 stud. Blood 2023, 142 (suppl.1), 2916–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, M.; Troester, S.; Grebien, F.; Goemans, B.F.; Zwaan, G.M.; Heidenreich, O. NUP98 oncofusions in myeyloid malignancies: an update on molecular mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. HemaSphere 2024, 8, 70013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Valerio, D.G.; Eisold, M.E.; Sinha, A.; Koche, R.P.; Hu, W.; Chen, C.W.; Chu, S.H.; Brien, G.L.; Park, C.Y.; et al. NUP98 fusion proteins interact with the NSL and MLL1 complexes to drive leukemogenesis. Cancer Cell 2016, 30, 863–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikamp, E.B.; Heinroich, J.A.; Perner, F.; Wong, E.M.; Hatton, C.; Wen, Y.; Barwe, S.P.; Golalakrishnapillai, A.; Xu, H.; et al. The menin-MLL1 interaction in a molecular dependency in NUP98-rearranghed AML. Blood 2022, 139, 894–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasouli, M.; Blair, H.; Troester, S.; Szoltysek, K.; Cameron, R.; Ashtiani, M.; Krippmner-Heidenreich, A.; Grebien, F.; McGeehan, G.; McGeehanm, G.; et al. The MLL-menin interaction is a therapeutic vulnerability in NUP98-rearranged AML. HemaSphere 2023, 7, e935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heikamp, E.D.; Martucci, C.; Henrich, J.A.; Neel, D.S.; Mahendra-Rajah, S.; Rice, H.; Wenge, D.V.; Perner, F.; Wen, Y.; Hatton, C.; et al. NUP98 fusion proteins and KMT2A-Menin antagonize PRC1.1 to drive gene expression in AML. Cell Rep 2024, 43, 114901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carraway, H.E.; Nakitandwe, J.; Cacovean, A.; Ma, Y.; Mumeke, B.; Waghmare, G.; Mandap, C.; Ahmed, U.; Kawalkezyk, N.; Butler, T.; et al. Complete remission of NUP98 fusion-positive acute myeloid leukemia with the covalent menin inhibitor BMF-219, icovamenib. Haematologica in press. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, H.; Cheri, D.; Ropa, J.; Purohit, T.; Kim, E.; Sulis, M.L.; Ferrando, L.; Cierpicki, T.; Grembecka, J.; et al. Combination of menin and kinase inhibitors as an effective treatment for leukemia with NUP98 translocations. Leukemia 2024, 34, 1674–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).