1. Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is the most common acute leukemia in adults with a median age at diagnosis of 68 years while myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is a clonal hematological disorder with heterogeneous presentation that can progress to AML. Both AML and MDS are among the most challenging hematologic malignancies, especially in elderly and unfit patients who cannot tolerate intensive chemotherapy and have inferior survival outcomes (1). The use of hypomethylating agents (HMA) such as azacytidine (AZA) and decitabine (DEC) in combination with Venetoclax (VEN) have shown promising results in improving overall survival (OS) and increasing remission rates in these patients as compared to HMA alone. HMA-VEN combination therapy got FDA approval in November 2018 for the treatment of newly diagnosed AML patients who are elderly (>75 years) or unfit for intensive induction regimens(2, 3). This approval was primarily based on promising results from clinical trials such as VIALE-A which demonstrated improved survival and higher remission with the AZA VEN combination as compared to AZA alone. VEN acts as a selective inhibitor of B-cell leukemia/lymphoma-2 (BCL-2), an anti-apoptotic protein overexpressed in leukemia stem cells (LSCs) (4, 5). Further trials involving analysis of LSCS undergoing HMA VEN treatment demonstrate that this therapy manifests its effects by causing disruption of tricyclic acid (TCA) cycle due to decreased alpha ketoglutarate and increased succinate levels leading to inhibition of electron transport chain (ETC) (6).

Despite the promising results of HMA-VEN combination therapy, recent studies have demonstrated that the response to these therapies is influenced by karyotypes and underlying genetic mutations in AML and MDS patients. Patients with complex karyotype and underlying genetic mutations such as TP53 mutation showed lower remission rates with this combination. (7, 8)

Most of the data on the efficacy of HMA-VEN combination therapy is from the countries with a well-developed healthcare system. There is scarcity of data from resource limited settings where lack of diagnostic tools for karyotype analysis, mutation detection, ineffective supportive care, unavailability of novel therapies and access to clinical trials can influence the treatment outcomes. In this study we aim to assess the outcomes of AML and MDS patients receiving HMA-VEN combination therapy. The study will provide valuable insight into the real-world application of this regimen in resource limited countries.

2. Materials and Methods

In this retrospective observational cohort, we included 96 patients of AML and MDS (newly diagnosed or relapsed/refractory) receiving HMA+VEN from January 2020 to December 2024 at the Armed Forces Bone Marrow Transplant Centre, Rawalpindi Pakistan. Ethical approval was taken from the hospital ethical committee in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients were diagnosed as per WHO criteria (9, 10)for AML or MDS and received HMA (decitabine or azacitidine) in combination with venetoclax (4) along with antifungal prophylaxis. Mandatory antifungal prophylaxis was added for all patients with the aim to reduce fungal infections and reduce the dose of VEN needed which resulted in significant cost reduction. AML was risk stratified as per ELN criteria (11, 12) whereas MDS was risk stratified as per IPSS or R-IPSS criteria (13, 14). Immunophenotyping was performed using multiparameter flow cytometry and gene expression analysis was performed using qualitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for AML gene panel testing for FLT3-ITD, NPM1, CBFB-MYH11, BCR-ABL1, RUNX1-RUNX1T1, DEK-NUP214 and MLL gene mutation. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) studies and next generation sequencing (NGS) was done in selected cases as per affordability of the patients. Patients of all age, sex, diagnosis of either MDS or AML either in front line settings or relapsed refractory settings receiving at least 1 cycle of HMA-VEN were included in the study.

Patients were given combination chemotherapy protocol according to the recommendations by Di Nardo et al. and European society of medical oncology (ESMO) clinical practice guidelines by Heuser et al. (3, 15) . It included either azacitidine or decitabine in combination with venetoclax. As per institutional policy, choice of HMA was based on physician preference, presence of TP53 mutation, age of patient, cost and availability of the agent. Decitabine was the preferred agent in younger patients especially those with TP53 mutation. Decitabine was administered intravenously at 20mg/m2 for 10 days every 28 days. Azacitidine was given at 75mg/m2 for 7 days either intravenously or subcutaneously. Venetoclax was dosed as 100 mg/day or 200 mg twice daily in combination with voriconazole 200 mg and itraconazole 100mg twice daily respectively. The optimum duration of venetoclax in combination with azacitidine/decitabine was 21 days but was tailored as per patients’ age, performance status, presence of active infections and bone marrow fibrosis. Treatment emergent toxicity was graded as per common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE v5.0). Treatment was interrupted for any CTCAE more than or equal to 3 except hematologic toxicity. The first cycle was administered irrespective of blood counts and delivery of subsequent cycles was dependent on disease response, patient tolerance and blood counts. In case of complete response and significant cytopenias in previous cycles, subsequent cycles were either delayed as per physician’s discretion to allow for count recovery or alternatively venetoclax dose was reduced to 14 days or less in some cases.

The primary outcomes measures were response rates, overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS). Response assessment was performed either at the end of the 1st cycle of chemotherapy or more frequently at the end of 2nd cycle. Treatment responses were evaluated as per International Working Group (IWG) criteria for MDS (16, 17) and ELN criteria for AML (12). Patients achieving complete remission (CR) continued to receive a total of 6 cycles of HMA plus venetoclax. Treatment beyond 4-6 cycles was based on transplant eligibility, financial status, ongoing response to treatment and tolerability. Patients with donor availability who achieved remission and had financial resources were offered hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). Patients with no donor availability or financial constraints were offered autologous HSCT if they achieved minimal residual disease MRD negative CR or intermediate to high dose cytarabine 1-2g/m2 consolidation. Patients who were not eligible for either of these consolidation therapies due to any reason were offered off label venetoclax maintenance at 100mg/day for 15 to 21 days in combination with voriconazole till progression and dose was adjusted as per blood counts and tolerability.

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics are described using median or mean for continuous variables and frequency (percentage) for categorical variables. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the day of diagnosis to death or last follow-up and disease-free survival (DFS) from the date of CR to the time of relapse or death. OS and DFS were evaluated with Kaplan-Meier method and the log rank test was applied to evaluate the association of factors of AML and MDS with OS and DFS. Statistical significance was defined as P value <0.05. Analyses were performed using SPSS v24.

3. Results

A total of 96 patients received a combination of HMA+VEN, with 54 (55.6%) in the AML cohort and 42 (43.3%) in the MDS cohort.

3.1. AML Cohort

Patients in the AML cohort (n=54) had a male-to-female ratio of 2:1, with a median age of 52 years (IQR:37- 62.2). Median WBC at diagnosis was 5.6 x10

9 per liter (IQR: 2.2- 15.1). The median number of HMA+ Ven cycles given were 3 (IQR: 2-6). Clinical and demographic profile of the cohort is tabulated (

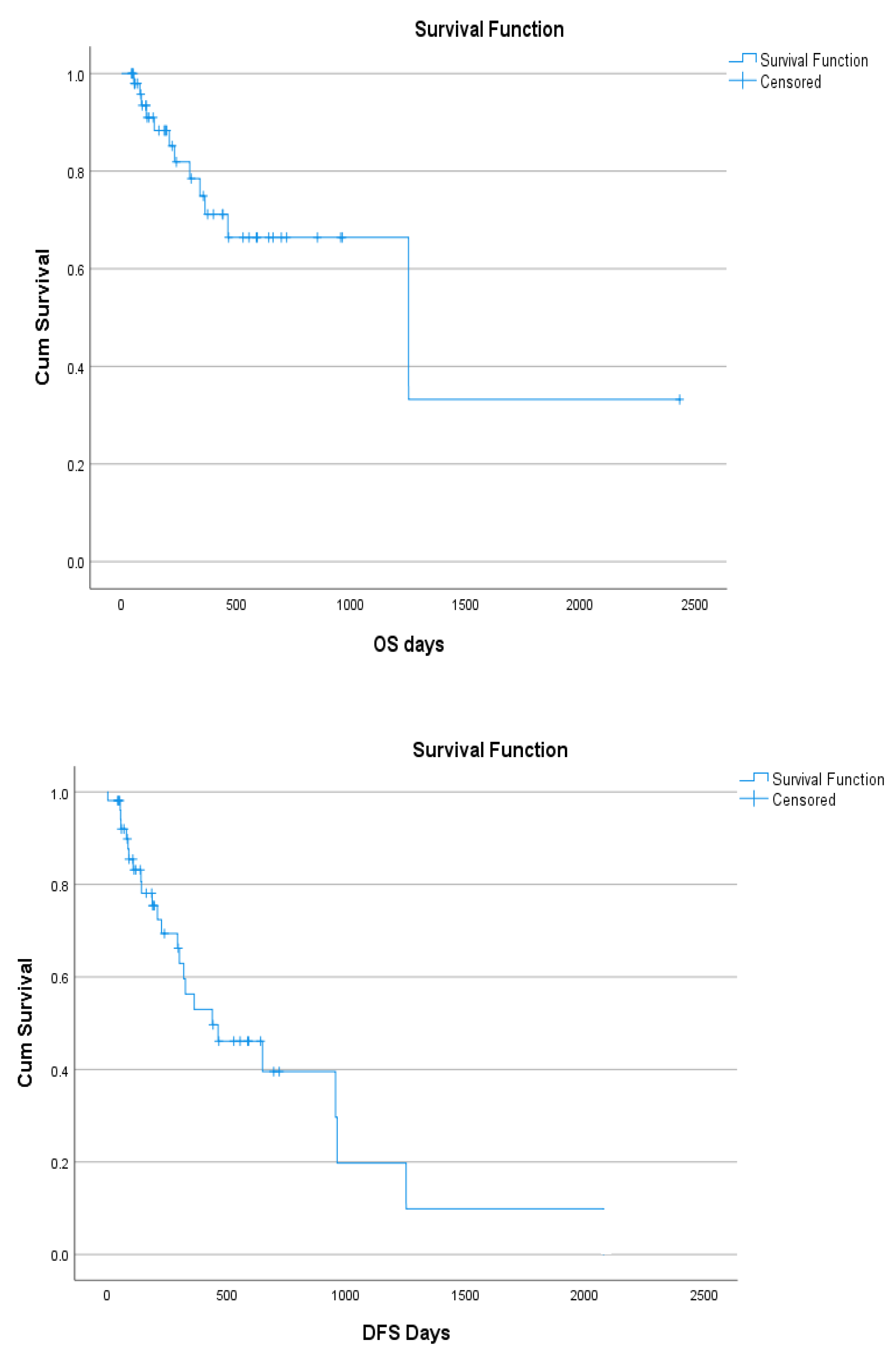

Table 1). The overall survival (OS) of AML cohort was 77.4% with median 1250 survival days (95% CI:139-2360) and the disease-free survival (DFS) was 52.8 % with median survival 438 days (95% CI:165-761) (

Figure 1). ORR at last follow-up was 27(50%) of which 24 (88.8%) had CR and 3(11.1) had CR i, MLFS in 1(1.9%), while response was not assessed in 2(3.7%). There was no response to HMA-Ven based treatment in 14(25.9%) and disease relapse in 10(18.5%) patients. Of patients relapsing on HMA VEN salvage, alternate HMA was administered in 9(14.8%) patients to which only 1(1.9%) patient responded. Patients with salvage HMA (n=8) had 75% OS (P=0.44) and 12% DFS (P=0.58). OS and DFS survival data was not available for 1 patient.

1. Indications for first line treatment were advanced age or frailty in 27 (50%), active infections in 3 (3.9%) and cardiac dysfunction in 2 (3.8%) and poor risk AML in 11 (20.37%) which included MR (n=8), AML with prior cytotoxic therapy (n=2) and AML with germline predisposition (Fanconi anemia evolved to AML) in 1 patient. Indications for use in 2nd line and beyond were relapsed disease in 6 (11.1%), primary refractory disease in 5 (9.3%).

2. Genetic mutations were detected in only 8(14.8%) of which RUNX1-RUNX1T1and FLT3 ITD were present in 3 each (75%%), TP53 mutation and WT1 were present in 1 each (25%). One patient had Fanconi anemia transformed to AML. Karyotype analysis showed normal karyotype in 45(83.4%), complex karyotype and CBF leukemia (18) in 3(5.5%) each whereas del7q and trisomy 8 and 11 in 1(1.8%) each.

3.WHO Classification:

4. Safety and Tolerability: HMA VEN was a fairly tolerable regimen and grade 3 or above cytopenias resulting in delays in subsequent chemotherapy cycle administration was observed in 5(9.3%) patients. The most frequent adverse event was febrile neutropenia (FN) which was observed in 36 (66.7%) of the AML cohort however there was notably no mortality in the entire cohort due to treatment related toxicity (TRM) or FN. AML patients with hematological toxicity leading to delayed subsequent chemotherapy cycle administration had 80% OS (P=0.66) and DFS (P=0.93). Patients who developed active infections during treatment had 72.2% OS (P=0.45) and 47.2% DFS (P=0.97).

5. Consolidative Treatment: A total of 7(12.9%) patients underwent consolidative HSCT of which 5 (71.4%) were fully matched whereas haploidentical and autologous HSCT were received by 1 each (28.5%). Patients ineligible for HSCT either due to high hematopoietic stem cell transplant comorbidity index score (HCT-CI score) or lack of donor availability were offered intermediate to high dose cytarabine(1-2g/m2) consolidation (IDAC/ HIDAC) in 5(9.3%) patients. Patients who were either deemed ineligible for any consolidative treatment or were non affording/non accepting were offered off label venetoclax maintenance after 6 cycles of HMA VEN in 10 (18.5%) patients due to lack of availability of oral azacitidine. None of the patients received continuous HMA VEN owing to severe financial toxicity.

Further association of AML factors with OS and DFS was summarized in

Table 1.

Table 1.

The association of AML factors with OS and DFS.

Table 1.

The association of AML factors with OS and DFS.

| |

|

Overall Survival |

Disease Free Survival |

| |

|

Total

(n)

|

Dead

(n)

|

Alive

n(%)

|

P-value |

Total

(n)

|

Dead /relapsed

(n)

|

Alive/disease free (%) |

P-value |

| WHO Classification |

AML-NOS |

34 |

6 |

28 (83) |

0.12 |

37 |

15 |

22 (59.4) |

0.04 |

| |

AML-MR |

14 |

9 |

5(57.1%) |

|

11 |

9 |

5(35.7%) |

|

| |

Prior cytotoxic therapy |

2 |

0 |

2 (100) |

|

2 |

0 |

2 (100) |

|

| |

RGA |

3 |

1 |

1 (50) |

|

2 |

2 |

0 (0) |

|

| Risk stratification |

Favorable |

3 |

1 |

2 (66.7) |

0.2 |

3 |

3 |

0 (0) |

0.005 |

| |

Int |

37 |

5 |

31 (86.1) |

|

36 |

14 |

22 (61.1) |

|

| |

Adverse |

14 |

6 |

8 (57.1) |

|

14 |

8 |

6 (42.9) |

|

| Sequencing |

1st line |

41 |

8 |

32 (80) |

0.81 |

41 |

16 |

24 (60) |

0.84 |

| |

2nd line |

12 |

4 |

8 (66.7) |

|

12 |

8 |

4 (33.3) |

|

| |

3rd line |

1 |

0 |

1 (100) |

|

1 |

1 |

0 (0) |

|

| HMA used |

Azacitidine |

44 |

6 |

37 (86) |

0.14 |

43 |

18 |

25 (58.1) |

0.34 |

| |

Decitabine |

10 |

6 |

4 (40) |

|

10 |

7 |

3 (30) |

|

| ORR Cycle 1 |

Yes |

26 |

4 |

22 (84.6) |

0.003 |

26 |

9 |

17 (65.4) |

0.03 |

| |

No |

17 |

8 |

9 (52.9) |

|

17 |

13 |

4 (23.5) |

|

| |

Not Assessed |

11 |

0 |

10 (100) |

|

10 |

3 |

7 (70) |

|

| Response after cycle 1 |

CR |

15 |

3 |

12 (80) |

0.02 |

15 |

5 |

10 (66.7) |

0.24 |

| |

CRi |

5 |

1 |

4 (80) |

|

5 |

1 |

4 (80) |

|

| |

PR |

6 |

0 |

6 (100) |

|

6 |

3 |

3 (50) |

|

| |

NR |

14 |

8 |

6 (42.9) |

|

14 |

13 |

1 (7.1) |

|

| |

IH |

1 |

0 |

1 (100) |

|

1 |

0 |

1 (100) |

|

| |

MLFS |

2 |

0 |

2 (100) |

|

2 |

0 |

2 (100) |

|

| |

Not assessed |

11 |

0 |

10 (100) |

|

10 |

3 |

7(70) |

|

| ORR Cycle 2 |

Yes |

34 |

3 |

31 (91.2) |

0.001 |

34 |

10 |

24(70) |

0.01 |

| |

No |

13 |

7 |

6 (46.2) |

|

13 |

12 |

1 (7.7) |

|

| |

Not Assessed |

7 |

2 |

4 (66.7) |

|

6 |

3 |

3 (50) |

|

| Response after cycle 2 |

CR |

27 |

3 |

24 (88.9) |

0.01 |

27 |

8 |

19 (70) |

0.06 |

| |

CRi |

3 |

0 |

3 (100) |

|

3 |

0 |

3 (100) |

|

| |

PR |

4 |

0 |

4 (100) |

|

4 |

2 |

2 (50) |

|

| |

NR |

12 |

7 |

5 (41.7) |

|

12 |

12 |

0 (0) |

|

| |

MLFS |

1 |

0 |

1 (100) |

|

1 |

0 |

1 (100) |

|

| |

Not assessed |

7 |

2 |

4 (66.7) |

|

6 |

3 |

3 (50) |

|

| ORR EOT |

Yes |

36 |

2 |

34 (94.4) |

0.001 |

36 |

9 |

27 (75) |

0.001 |

| |

No |

16 |

10 |

6 (37.5) |

|

16 |

15 |

1 (6.3) |

|

| |

Not Assessed |

2 |

0 |

1 (100) |

|

1 |

1 |

0 (0) |

|

| IDAC cons |

Yes |

5 |

1 |

4 (80) |

0.91 |

5 |

1 |

4 (80) |

0.37 |

| |

No |

48 |

11 |

37 (77.1) |

|

48 |

24 |

24 (50) |

|

| Allo BMT |

Yes |

5 |

1 |

4 (80) |

0.86 |

5 |

1 |

4 (80) |

0.32 |

| |

No |

48 |

11 |

37 (77.1) |

|

48 |

24 |

24 (50) |

|

| Haplo BMT |

Yes |

1 |

0 |

1 (100) |

0.51 |

1 |

1 |

0 (0) |

0.91 |

| |

No |

52 |

12 |

40 (76.9) |

|

52 |

24 |

28 (53.8) |

|

| Auto BMT |

Yes |

1 |

0 |

1 (100) |

0.51 |

1 |

0 |

1 (100) |

0.37 |

| |

No |

52 |

12 |

40 (76.9) |

|

52 |

25 |

27 (51.9) |

|

| Ven Maintenance |

Yes |

10 |

0 |

10 (100) |

0.02 |

10 |

4 |

6 (60) |

0.18 |

| |

No |

43 |

12 |

31 (72.1) |

|

43 |

21 |

22 (51.2) |

|

Table 2.

OS and DFS as per WHO classification (OS: Overall Survival, DFS: Disease free survival, WHO: World Health Organization).

Table 2.

OS and DFS as per WHO classification (OS: Overall Survival, DFS: Disease free survival, WHO: World Health Organization).

| WHO Classification |

Overall Survival (OS)

(p=0.002)

|

Disease Free Survival (DFS)

(p=0.12)

|

| AML with recurrent genetic abnormalities (n=3) |

66.7% |

33.3% |

| AML with minimal differentiation (n=3) |

66.7% |

66.7% |

| AML without maturation (n=4) |

75% |

50% |

AML with maturation

(n=18) |

100% |

66.7% |

AML with myelomonocytic differentiation

(n=7) |

100% |

66.7% |

| Acute monocytic leukemia (n=2) |

100% |

100% |

AML with myelodysplasia related changes (MR)

(n=14) |

57.1% |

35.7% |

AML with prior cytotoxic therapy

(n=2) |

100% |

100% |

AML with germline predisposition

(n=1) |

100% |

100% |

Figure 1.

OS and DFS of AML patients.

Figure 1.

OS and DFS of AML patients.

3.2. MDS cohort

MDS cohort (n=42) had a male-to- female ratio 9.5:1 with 51 years median age (IQR:36.5- 57.5). Out of 42, 5 (11.9%) patients progressed from MDS-MLD and 1(2.4%) from MDS-MPN while 36(83.7) had no prior presentation or antecedent hematologic disorders. Median Hb, white cell count and platelet count at diagnosis were 7.80 g/dL (IQR: 6.80- 9.59), 5.19 x 10

9 per liter (IQR: 1.73- 5.44) and 109 x 10

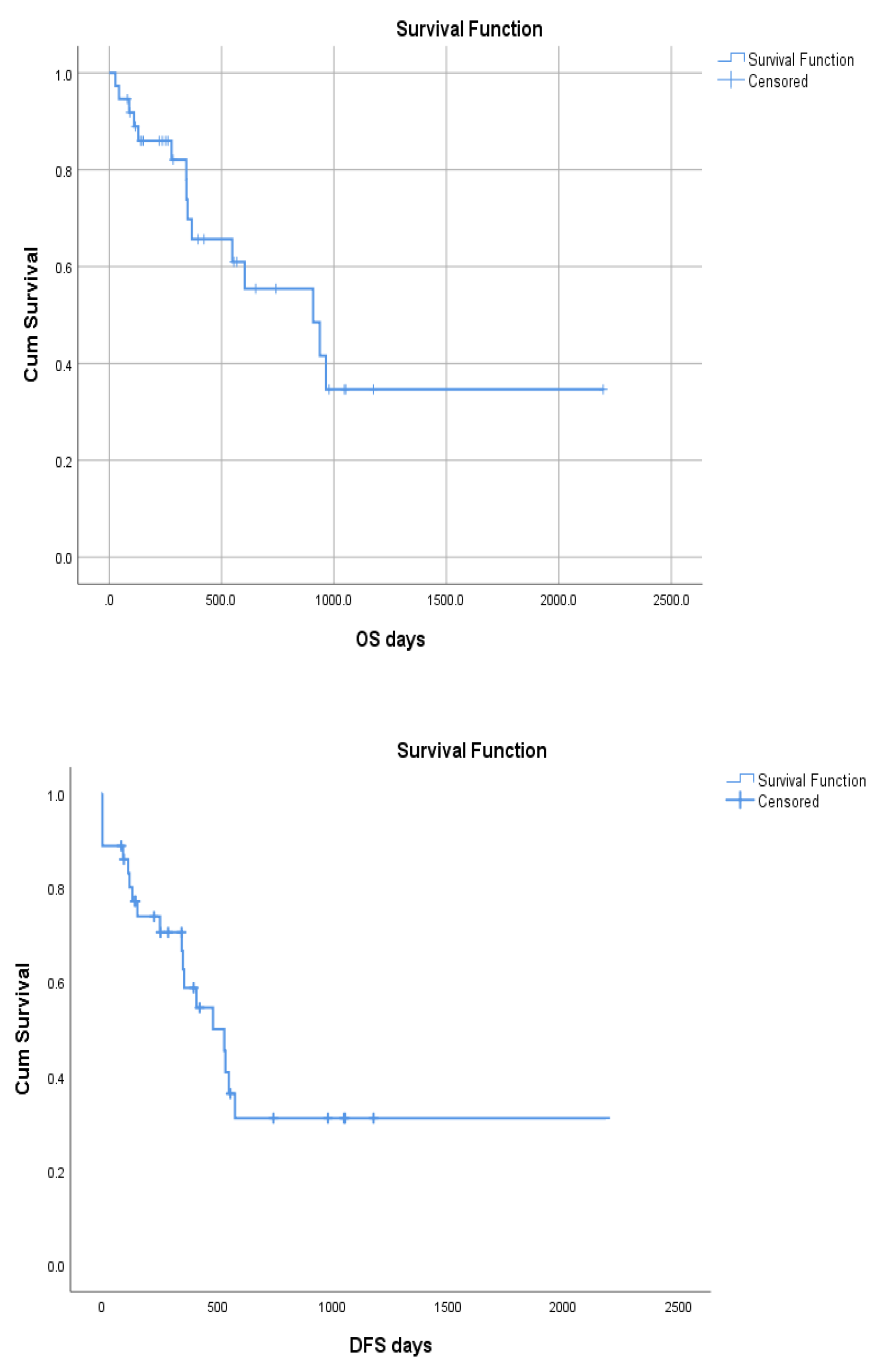

9 per liter (IQR: 23- 115) respectively. The OS of MDS cohort on HMA-Ven combination therapy was 59.5% with median 907 survival days (95% CI: 386-1424) and the DFS was 44.4 % with median survival 528 days (95% CI: 336-719) (

Figure 2). Total of 8(21.1%) patients experienced disease relapse. Median days to achieve response were 64 days (IQR: 35.25- 85.50). The association of MDS factors with OS and DFS is summarized in

Table 2.

1.Disease Classification: Disease subclassification showed MDS- IB1 in 5(11.6%), IB2 in 28(65.1%), MDS-LB in 4(9.3%), MDS-MPN-U, MDS-F in 2 each (4.7% each), MDS-RS in 1 (2.3%). Disease classification was missing for 1 patient.

2. Genetic abnormalities: Karyotype analyses showed normal cytogenetics in 38(90.5%) and abnormal in 4(9.5%). Genetic mutations were present in 3(7.3%) of which TP53, del7q were present in 1 each whereas 1 patient had ASXL1, TET2 EZH2, RUNX1 and STAG2 mutations.

3.Risk Stratification: The median R-IPSS and IPSS scores were 5 (IQR: 4.2-6) and 1.5 (IQR: 0.75-2) respectively.

4. Safety and Tolerability: HMA VEN in MDS cohort was well tolerated. FN was observed in 23(54.8%) and hematologic toxicity leading to delays in subsequent cycles was observed in 23(54.8%) patients.

5.Consolidative Treatment: Of all the MDS cohort, 7(17.1%) underwent consolidative allogeneic HSCT and 2(4.9%) haploidentical HSCT.

Total 5(12.2%) of the patients received off label venetoclax maintenance.

Figure 2.

OS and DFS of MDS patients.

Figure 2.

OS and DFS of MDS patients.

Table 2.

The association of MDS factors with OS and DFS.

Table 2.

The association of MDS factors with OS and DFS.

| |

|

Overall Survival |

Disease Free Survival |

| |

|

Total

(n)

|

Dead

(n)

|

Alive

n(%)

|

p-value |

Total

(n)

|

Dead/ Relapsed

(n)

|

Alive/ Disease free

n(%)

|

p-value |

| Prior disease |

MDS-MLD |

5 |

2 |

3 (60) |

0.65 |

5 |

2 |

3 (60) |

0.01 |

| |

MDS-MPN |

1 |

0 |

1 (100) |

|

1 |

1 |

0 (0) |

|

| |

No |

31 |

13 |

18 (58.1) |

|

30 |

17 |

13 (43.3) |

|

| Cytogenetics |

Normal |

24 |

8 |

16 (66.7) |

0.12 |

24 |

11 |

13 (54.2) |

0.06 |

| |

Abnormal |

4 |

2 |

2 (50) |

|

3 |

3 |

0 (0) |

|

| |

NA |

9 |

5 |

4 (44.4) |

|

9 |

6 |

3 (33.3) |

|

| HMA |

Azacitidine |

28 |

10 |

18 (64.3) |

0.41 |

27 |

15 |

12 (44.4) |

0.78 |

| |

Decitabine |

9 |

5 |

4 (44.4) |

|

9 |

5 |

4 (44.4) |

|

| ORR after cycle 1 |

Yes |

12 |

3 |

9 (75) |

0.28 |

12 |

2 |

10 (83.3) |

0.01 |

| |

No |

11 |

5 |

6 (54.5) |

|

10 |

8 |

2 (20) |

|

| |

NA |

14 |

7 |

7 (50) |

|

14 |

10 |

4 (28.6) |

|

| Response after cycle 1 |

Response |

11 |

3 |

10 (90.9) |

0.18 |

13 |

3 |

10 (79.9) |

0.001 |

| |

No Response |

7 |

4 |

3 (42.8) |

|

6 |

5 |

1 (16.6) |

|

| |

Stable disease |

3 |

1 |

2 (66.7) |

|

3 |

2 |

1 (33.3) |

|

| |

Not assessed |

9 |

4 |

5 (55.6) |

|

9 |

6 |

3 (33.3) |

|

| |

NA |

5 |

3 |

2 (40) |

|

5 |

4 |

1 (20) |

|

| Febrile neutropenia |

Yes |

21 |

10 |

11 (52.4) |

0.24 |

21 |

13 |

8 (38.1) |

0.07 |

| |

No |

16 |

5 |

11 (68.8) |

|

15 |

7 |

8 (53.3) |

|

| ORR after cycle 2 |

Yes |

19 |

6 |

13 (68.4) |

0.12 |

19 |

6 |

13 (68.4) |

0.009 |

| |

No |

15 |

9 |

6 (40) |

|

14 |

12 |

2 (14.3) |

|

| |

NA |

3 |

0 |

3 (100) |

|

3 |

2 |

1 (33.3) |

|

| Response after cycle 2 |

Response |

21 |

6 |

15 (71.4) |

0.03 |

21 |

7 |

14 (66.6) |

0.01 |

| |

No Response |

8 |

5 |

3 (37.5) |

|

4 |

3 |

1 (25) |

|

| |

Stable disease |

6 |

4 |

2 (33.3) |

|

6 |

6 |

0 (0) |

|

| |

NA |

2 |

0 |

2 (100) |

|

2 |

1 |

1 (50) |

|

| ORR EOT |

Yes |

17 |

4 |

13 (76.5) |

0.07 |

17 |

3 |

14 (82.4) |

0.001 |

| |

No |

19 |

11 |

8 (42.1) |

|

18 |

17 |

1 (5.6) |

|

| |

NA |

1 |

0 |

1 (100) |

|

1 |

0 |

1 (100) |

|

| Response EOT |

Response |

20 |

4 |

7 (45.4) |

0.62 |

20 |

6 |

14 (70) |

0.001 |

| |

No Response |

11 |

6 |

5 (45.4) |

|

10 |

9 |

1 (10) |

|

| |

Stable disease |

5 |

3 |

2 (40) |

|

5 |

5 |

0 (0) |

|

| |

Not assessed |

1 |

0 |

1 (100) |

|

1 |

0 |

1 (100) |

|

| Consolidation Allo |

Yes |

6 |

2 |

4 (66.7) |

0.09 |

6 |

2 |

4 (66.7) |

0.06 |

| |

No |

30 |

12 |

18 (60) |

|

29 |

17 |

12 (41.4) |

|

| |

NA |

1 |

1 |

0 (0) |

|

1 |

1 |

0 (0) |

|

| Consolidation Haplo |

Yes |

2 |

1 |

1 (50) |

0.17 |

2 |

1 |

1 (50) |

0.37 |

| |

No |

34 |

13 |

21 (61.8) |

|

33 |

18 |

15 (45.5) |

|

| |

NA |

1 |

1 |

0 (0) |

|

1 |

1 |

0 (0) |

|

| Relapse |

Yes |

8 |

6 |

2 (25) |

0.001 |

8 |

8 |

0 (0) |

0.01 |

| |

No |

28 |

8 |

20 (71.4) |

|

27 |

11 |

16 (59.3) |

|

| |

Refractory |

1 |

1 |

0 (0) |

|

1 |

1 |

0 (0) |

|

4. Discussion

Our study documents real world outcomes of HMA+VEN therapy in resource limited settings, showing important variability in treatment indications, administration patterns and patient outcomes when compared with previously published clinical trial data. Notably our study highlights discrepancies in response rates and survival outcomes relative to those reported from high-income countries.

The AML cohort in our study consisted of a younger population than typically observed, where the median age is around 65 years (19). The ORR in the AML cohort improved from cycle 1 to the end of treatment which is consistent with rapid onset of action of this combination. (18)

However, CR rates in both AML and MDS cohorts were less than those reported in clinical trials from high-income settings. For instance, DiNardo et al. reported a CR rate of 67% in elderly patients with AML (20) and Zeiden et al. reported a CR of 40% in high risk MDS patients (21).

Real world data even from high resource centers shows inferior response rates compared to the VIALE -A trial, highlighting the challenges of translating clinical trial results into practice(22).

In our MDS cohort, the ORR declined from cycle 2 onwards to end of treatment (EOT) potentially due to cycle interruptions, increased myelosuppression or clonal progression and secondary resistance as noted in prior literature.

In front line AML settings, HMA +VEN achieved lower response rates compared to conventional induction chemotherapy, even in LMICs (23). This supports the continued superiority of intensive regimens where feasible. However, factors such as younger age, good performance status and access to supportive care often influence the choice of intensive induction, while limitations in infrastructure and expertise restrict its availability to select centers and in institutions lacking such capabilities, HMA+VEN offers a practical and tolerable alternative(24).

Survival outcomes in both AML and MDS patients in our cohort exceeded those historically reported for HMA monotherapy. For instance, Fenaux et al. documented a median OS of 15 months (50.8% at 2 years) with azacytidine alone in high risk MDS(25). The improved outcomes seen in our study may reflect the synergistic mechanism of action between HMA and VEN, where HMAs induce DNA hypomethylation and differentiation, while VEN targets BCL-2, leading to mitochondrial apoptosis of leukemic stem cells (LSCs)(26).

Resistance to HMA monotherapy has been linked to mutations in UCK2, SLC29A1 and reduced expressions of genes critical for decitabine activation. Furthermore, azacytidine has been shown to spare founder clones, allowing malignant hematopoiesis to persist even in morphologic remission. In contrast, VEN inhibits oxidative phosphorylation in LSCs, contributing to deeper responses and potentially lower relapse rates(26).

Although certain genetic mutations (FLT3-ITD, TP53 and RAS pathway) are associated with poor outcomes following HMA+VEN therapy,(27) we did not observe such correlation in our cohort. Prior studies by Bejar et al. and Feld et al. have reported poor prognostic associations with TP53, RUNX1 and ASXL1 mutations in MDS and AML respectively, which differs from our findings, likely due to limited molecular profiling in our cohort. Similarly, monocytic differentiation in AML, associated with lower VEN sensitivity in some studies, was not significantly associated with response in our analysis (28).

Azizi et al. demonstrated that HMA+ VEN improves response rates compared to HMA alone but increases myelosuppression particularly neutropenia [

30]. Febrile neutropenia was more frequent in our study compared to western cohorts. A meta-analysis by Guo et al. reported a 47% pooled incidence of febrile neutropenia in patients receiving HMA+VEN [

31] underscoring the need for robust infection control and supportive care, which are often inadequate in LMICs. Infectious complications, financial barriers, and limited supportive care availability remain significant challenges in these settings (29).

Our MDS cohort population includes high risk patients, historically known for dismal outcomes(30). However, with HMA+VEN, several patients were successfully bridged to HSCT. Given the declining response rates in MDS with prolonged therapy, early consolidation with HSCT should be considered to improve long term outcomes.(31)

In LMICs, HMA +VEN has emerged as a valuable first line therapy especially where access to intensive chemotherapy is limited or unaffordable and many of these patients are denied any form of treatment at all due to severe financial constraints and lack of advanced healthcare infrastructure. Based on favorable response and tolerability, this regimen is particularly suitable for patients unfit for intensive chemotherapy due to age, performance status, comorbidities, active infection, or financial barriers. Based on high relapse rate and low median duration of response, the responses achieved with HMA+VEN need to be consolidated depending on donor availability, depth of remission and patient eligibility, with definitive therapies, including allogeneic, haploidentical, or even autologous HSCT in selected cases achieving MRD negative CR (32, 33). Where transplant is not feasible, high or intermediate dose cytarabine consolidation may be considered. Patients not eligible for any consolidation therapy, may be offered off label venetoclax maintenance especially in settings where azacitidine maintenance is not cost effective(34). HMA+VEN may even be used as a bridge to intensive chemotherapy in patients who need some time to arrange finances to be able to bear the out-of-pocket cost of intensive induction chemotherapy.

Our study offers valuable insight into the real-world application of HMA+VEN, though it has several limitations. Only two patients underwent next generation sequencing (NGS) based testing for AML or MDS related genes rendering us underpowered to assess the impact of mutational landscape on treatment response. Additionally, the retrospective design, small sample size, short follow up duration, and limited molecular testing reduce generalizability. Future research should focus on prospective trials with larger cohorts, improved access to molecular diagnostics, and investigations into research mechanisms, toxicity mitigation, and rational combinations to enhance efficacy. Incorporating novel agents into HMA+VEN backbone may offer therapeutic gains and warrant exploration. We aim to use this study to guide treatment algorithms for AML and MDS patients who are not a candidate for IC due to factors listed above.

5. Conclusions

HMA-VEN combination therapy is a feasible and effective treatment for patients with MDS and AML presenting in a resource limited setting. However, the low CR rates and high incidence of febrile neutropenia compared to high-income countries underscores the need for better supportive care, comprehensive molecular testing and individualized treatment approaches.

References

- Tefferi A, Vardiman JW. Myelodysplastic syndromes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361(19):1872-85.

- Estey, E.; Karp, J.E.; Emadi, A.; Othus, M.; Gale, R.P. Recent drug approvals for newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia: gifts or a Trojan horse? Leukemia 2020, 34, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiNardo, C.D.; Pratz, K.W.; Letai, A.; A Jonas, B.; Wei, A.H.; Thirman, M.; Arellano, M.; Frattini, M.G.; Kantarjian, H.; Popovic, R.; et al. Safety and preliminary efficacy of venetoclax with decitabine or azacitidine in elderly patients with previously untreated acute myeloid leukaemia: a non-randomised, open-label, phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinardo, C.D.; Jonas, B.A.; Pullarkat, V.; Thirman, M.J.; Garcia, J.S.; Wei, A.H.; Konopleva, M.; Döhner, H.; Letai, A.; Fenaux, P.; et al. Azacitidine and Venetoclax in Previously Untreated Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souers, A.J.; Leverson, J.D.; Boghaert, E.R.; Ackler, S.L.; Catron, N.D.; Chen, J.; Dayton, B.D.; Ding, H.; Enschede, S.H.; Fairbrother, W.J.; et al. ABT-199, a potent and selective BCL-2 inhibitor, achieves antitumor activity while sparing platelets. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollyea, D.A.; Stevens, B.M.; Jones, C.L.; Winters, A.; Pei, S.; Minhajuddin, M.; D’alessandro, A.; Culp-Hill, R.; Riemondy, K.A.; Gillen, A.E.; et al. Venetoclax with azacitidine disrupts energy metabolism and targets leukemia stem cells in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1859–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa U, Castelli G, Pelosi E. TP53-mutated myelodysplasia and acute myeloid leukemia. Mediterranean Journal of Hematology and Infectious Diseases. 2023;15(1):e2023038.

- Li, X.; Suh, H.S.; Lachaine, J.; Schuh, A.C.; Pratz, K.; Betts, K.A.; Song, J.; Dua, A.; Bui, C.N. Comparative Efficacy of Venetoclax-Based Combination Therapies and Other Therapies in Treatment-Naive Patients With Acute Myeloid Leukemia Ineligible for Intensive Chemotherapy: A Network Meta-Analysis. Value Heal. 2023, 26, 1689–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardiman, J.W.; Harris, N.L.; Brunning, R.D. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of the myeloid neoplasms. Blood 2002, 100, 2292–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arber, D.A.; Orazi, A.; Hasserjian, R.; Thiele, J.; Borowitz, M.J.; Le Beau, M.M.; Bloomfield, C.D.; Cazzola, M.; Vardiman, J.W. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood 2016, 127, 2391–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döhner, H.; Wei, A.H.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Craddock, C.; DiNardo, C.D.; Dombret, H.; Ebert, B.L.; Fenaux, P.; Godley, L.A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2022 recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the ELN. Blood 2022, 140, 1345–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döhner, H.; Estey, E.; Grimwade, D.; Amadori, S.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Büchner, T.; Dombret, H.; Ebert, B.L.; Fenaux, P.; Larson, R.A.; et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood 2017, 129, 424–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, P.; Cox, C.; LeBeau, M.M.; Fenaux, P.; Morel, P.; Sanz, G.; Sanz, M.; Vallespi, T.; Hamblin, T.; Oscier, D.; et al. International Scoring System for Evaluating Prognosis in Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Blood 1997, 89, 2079–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, P.L.; Tuechler, H.; Schanz, J.; Sanz, G.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Solé, F.; Bennett, J.M.; Bowen, D.; Fenaux, P.; Dreyfus, F.; et al. Revised International Prognostic Scoring System for Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Blood 2012, 120, 2454–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuser, M.; Ofran, Y.; Boissel, N.; Mauri, S.B.; Craddock, C.; Janssen, J.; Wierzbowska, A.; Buske, C. Acute myeloid leukaemia in adult patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheson, B.D.; Greenberg, P.L.; Bennett, J.M.; Lowenberg, B.; Wijermans, P.W.; Nimer, S.D.; Pinto, A.; Beran, M.; de Witte, T.M.; Stone, R.M.; et al. Clinical application and proposal for modification of the International Working Group (IWG) response criteria in myelodysplasia. Blood 2006, 108, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, A.M.; Platzbecker, U.; Bewersdorf, J.P.; Stahl, M.; Adès, L.; Borate, U.; Bowen, D.T.; Buckstein, R.J.; Brunner, A.M.; E Carraway, H.; et al. Consensus proposal for revised International Working Group response criteria for higher risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 2023, 141, 2047–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.G.; Volpe, V.O.; Wang, C.; Ball, S.; Tobon, K.; Chan, O.; Padron, E.; Kuykendall, A.; Lancet, J.E.; Komrokji, R.; et al. Outcomes by best response with hypomethylating agent plus venetoclax in adults with previously untreated acute myeloid leukemia. Ann. Hematol. 2024, 104, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliusson, G.; Antunovic, P.; Derolf, Å.; Lehmann, S.; Möllgård, L.; Stockelberg, D.; Tidefelt, U.; Wahlin, A.; Hoglund, M. Age and acute myeloid leukemia: real world data on decision to treat and outcomes from the Swedish Acute Leukemia Registry. Blood 2009, 113, 4179–4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinardo, C.D.; Pratz, K.; Pullarkat, V.; Jonas, B.A.; Arellano, M.; Becker, P.S.; Frankfurt, O.; Konopleva, M.; Wei, A.H.; Kantarjian, H.M.; et al. Venetoclax combined with decitabine or azacitidine in treatment-naive, elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2019, 133, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komrokji, R.S.; Singh, A.M.; Al Ali, N.; Chan, O.; Padron, E.; Sweet, K.; Kuykendall, A.; Lancet, J.E.; Sallman, D.A. Assessing the role of venetoclax in combination with hypomethylating agents in higher risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood Cancer J. 2022, 12, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleyer, L.; Klammer, P.; Drost, M.; Angermann, H.; Keil, F.; Petzer, V.; Heibl, S.; Moritz, J.; Girschikofsky, M.; Stampfl-Mattersberger, M.; et al. Real-World Comparison of Outcomes of Patients Treated with HMA Monotherapy Versus HMA-Ven - Insights from 1634 Patients Included within the Austrian Myeloid Registry of the AGMT Study Group. Blood 2024, 144, 3793–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okello, C.D.; Meshinchi, S.; Tarlock, K.; Warren, E.H.; Towlerton, A.M.; Ddungu, H.; Mulumba, Y.; Geriga, F.; Orem, J.; Balagadde, J.K. Clinical Outcome and Treatment-Related Mortality in Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia Treated at the Uganda Cancer Institute. Blood 2022, 140, 8940–8941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, C.; Unni, M.; Paul, M.; Harimadhavan, M.; Ganapathy, R.; Haridas, N.K.; V.S., S.; Sreenaryanan, C.; Yawalkar, R.; Mony, U.; et al. Treatment Challenges in Acute Myeloid Leukemia in Lower-Middle-Income Countries: Navigating Intensity, Affordability, and Infections. Blood 2023, 142, 5180–5180. [CrossRef]

- Fenaux, P.; Ades, L. Review of azacitidine trials in Intermediate-2-and High-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk. Res. 2009, 33, S7–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, R.; Nikoo, M.Z.; Veeraballi, S.; Singh, A. Venetoclax and Hypomethylating Agent Combination in Myeloid Malignancies: Mechanisms of Synergy and Challenges of Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bataller, A.; Bazinet, A.; DiNardo, C.D.; Maiti, A.; Borthakur, G.; Daver, N.G.; Short, N.J.; Jabbour, E.J.; Issa, G.C.; Pemmaraju, N.; et al. Prognostic risk signature in patients with acute myeloid leukemia treated with hypomethylating agents and venetoclax. Blood Adv. 2024, 8, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Yang, J.; Chen, M.; Xiang, X.; Ma, H.; Niu, T.; Gong, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Wu, Y. Myelomonocytic and monocytic acute myeloid leukemia demonstrate comparable poor outcomes with venetoclax-based treatment: a monocentric real-world study. Ann. Hematol. 2024, 103, 1197–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangudubiyyam, S.K.S.S.; Dhawan, R.; Swaminathan, A.; Stitha, P.; Naik, R.D.; Aggarwal, M.; Kumar, P.; Dass, J.; Viswanathan, G.; Tyagi, S.; et al. Challenges and outcomes of treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in resource-constrained settings. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 7014–7014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekeres, M.A.; Cutler, C. How we treat higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 2014, 123, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallman DA, Xie Z. Frontline treatment options for higher-risk MDS: can we move past azacitidine? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2023;2023(1):65-72.

- Unglaub, J.M.; Schlenk, R.F.; Middeke, J.M.; Krause, S.W.; Kraus, S.; Einsele, H.; Kramer, M.; Zukunft, S.; Kauer, J.; Renders, S.; et al. Venetoclax-based salvage therapy as a bridge to transplant is feasible and effective in patients with relapsed/refractory AML. Blood Adv. 2025, 9, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, L.; Ma, R.; Pang, A.; Yang, D.; Chen, X.; Wei, J.; He, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhai, W.; et al. Outcome of autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with favorable-risk acute myeloid leukemia in first remission. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Chillon, C.; Dillon, R.; Russell, N. Optimal Post-Remission Consolidation Therapy in Patients with AML. Acta Haematol. 2023, 147, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).