Submitted:

10 February 2025

Posted:

11 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

INTRODUCTION

1.1. STEM EDUCATION FOR THE 21ST CENTURY

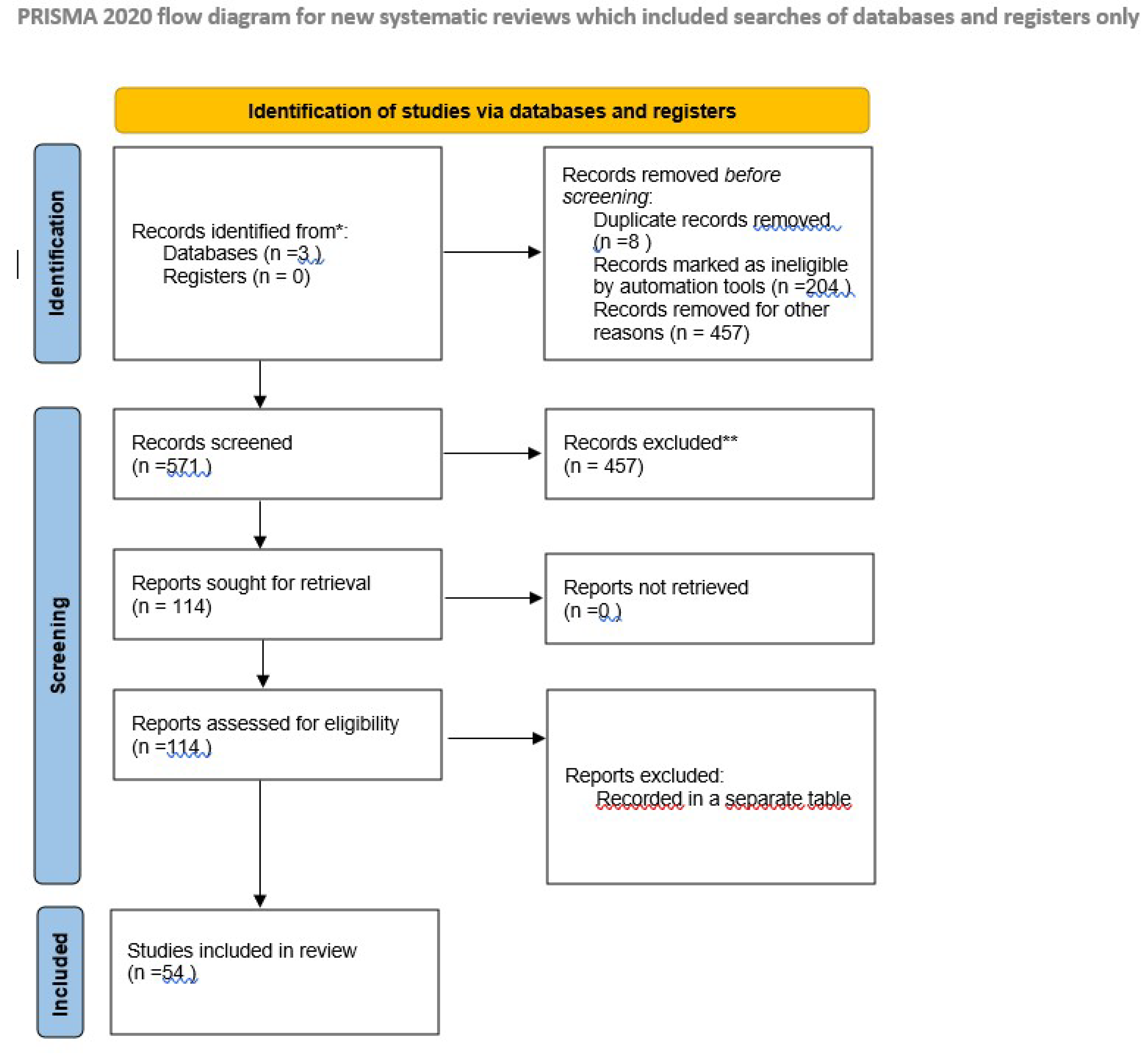

- Articles published between 01/11/2024 and the day of the search were selected.

- Articles only, not book chapters or conference proceedings.

- Articles written in English.

- Articles with free access for all.

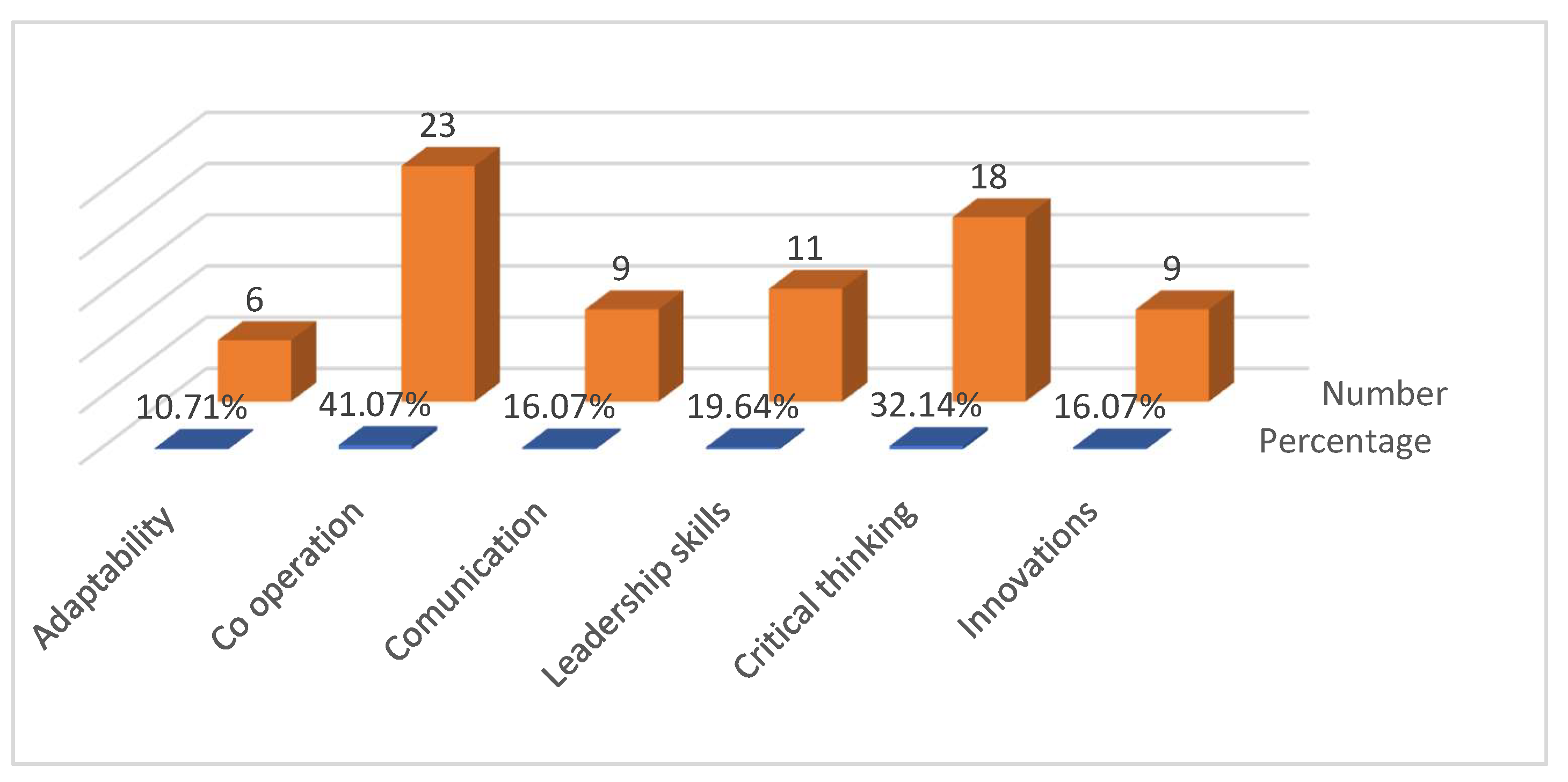

- In terms of 21st century skills, collaboration and critical thinking have been studied more extensively in the literature reviewed.

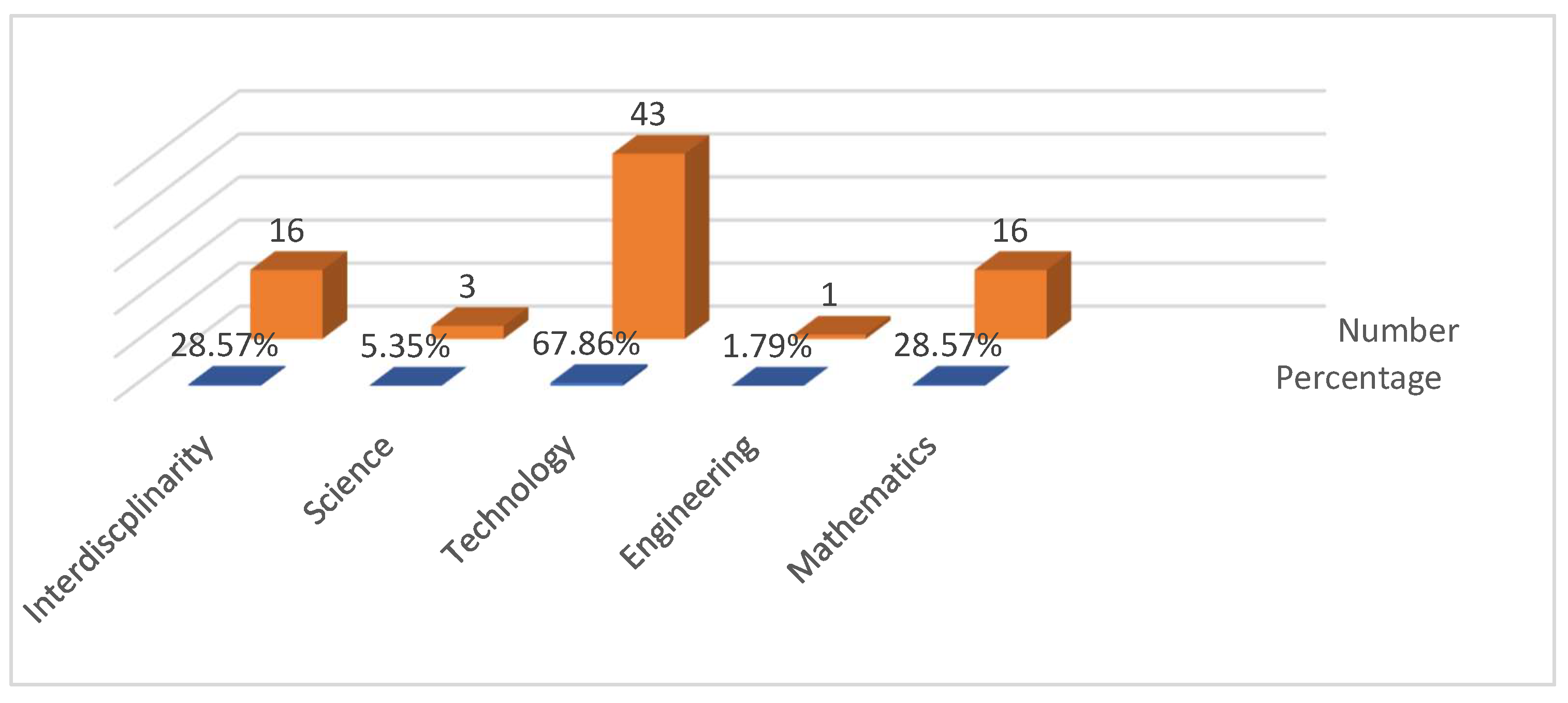

- In terms of STEM, technology is the most relevant.

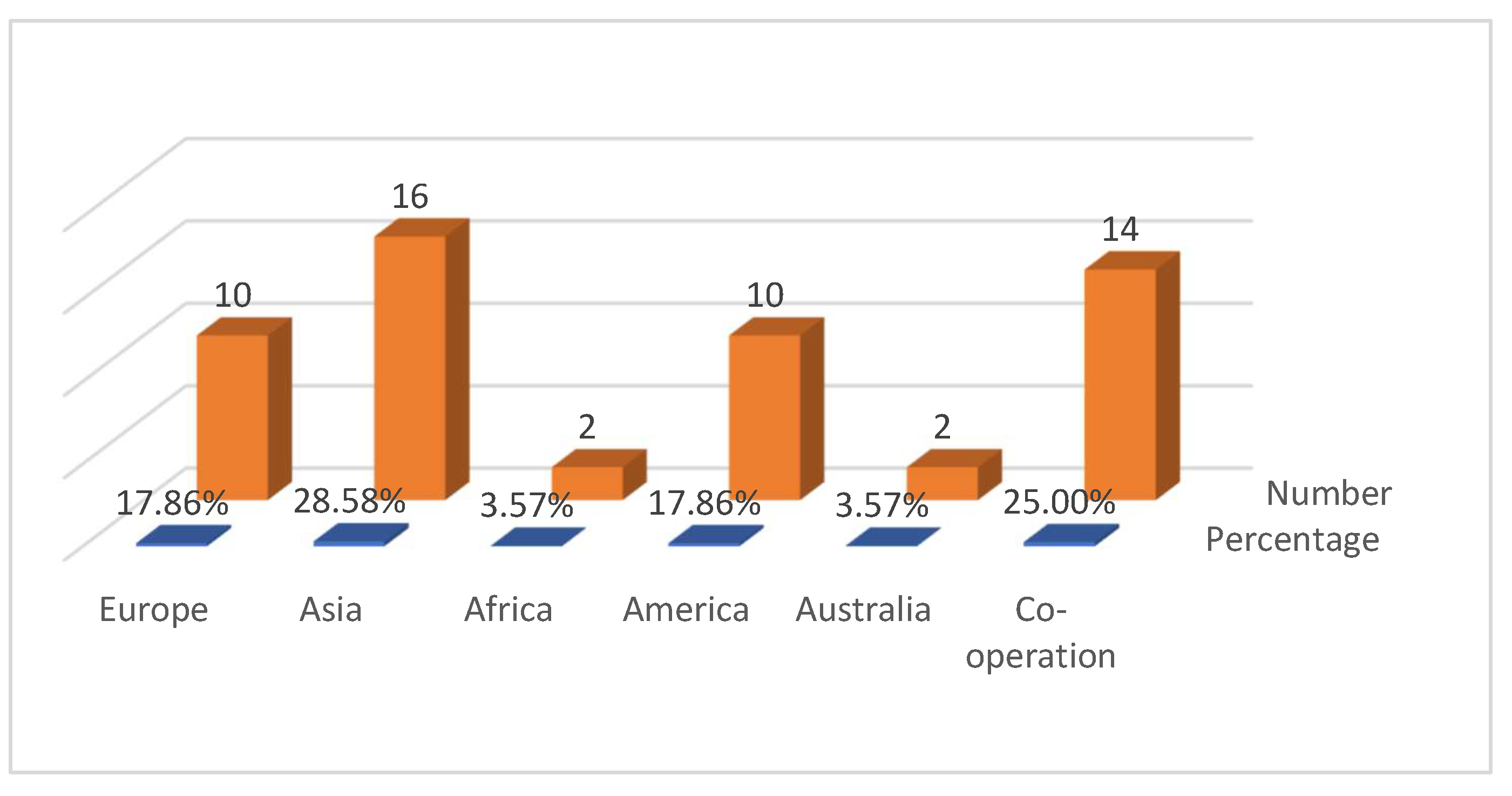

- Many of the studies were carried out by teams of researchers whose institutions are located on different continents, which reinforces the need for collaboration and communication between the scientific community in order to carry out research.

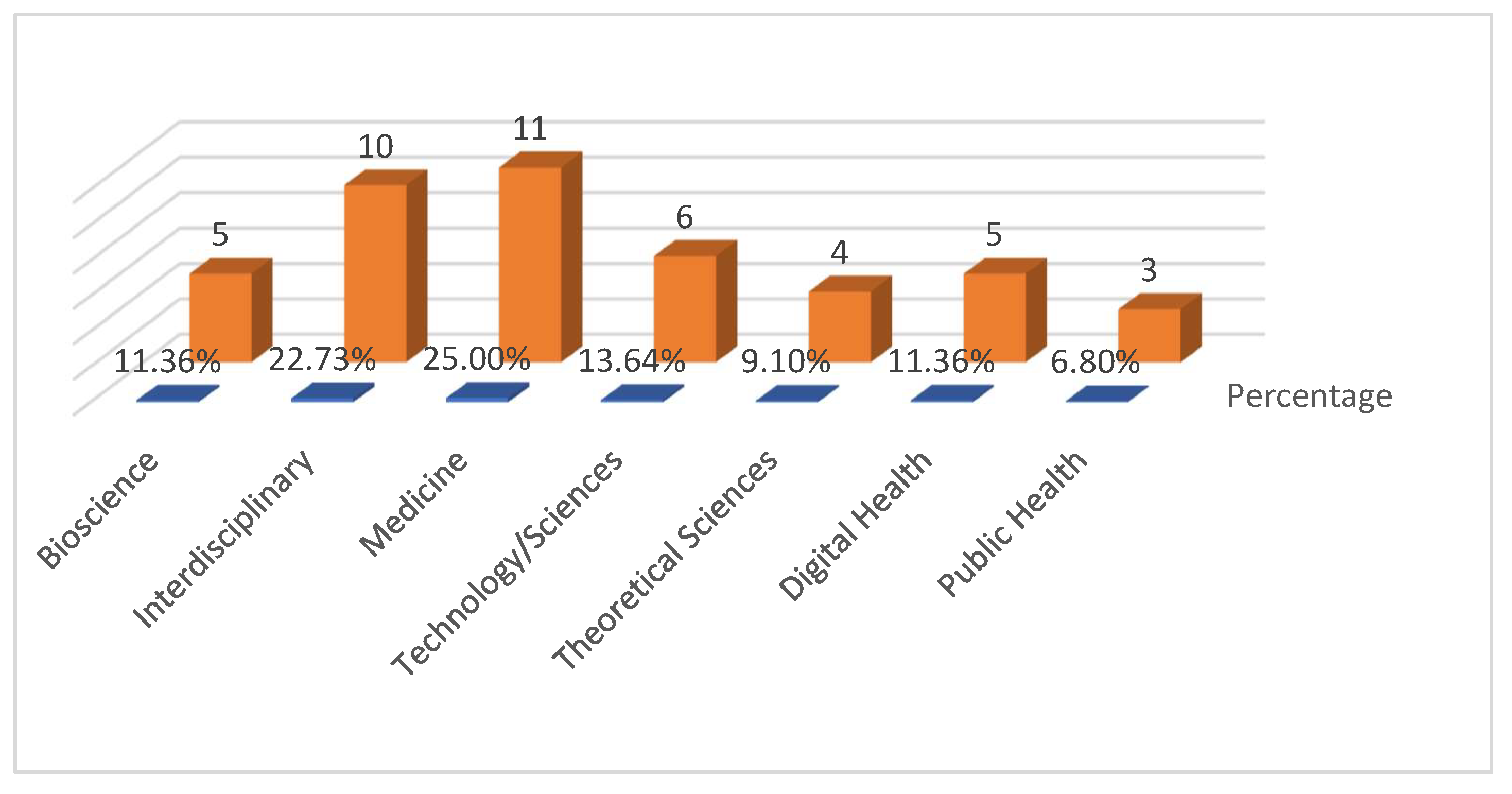

- The articles came from newspapers and journals in many different scientific fields, demonstrating that the pandemic was a problem that required an interdisciplinary approach to solve.

4.1. ADAPTABILITY

4.2. COLLABORATION

4.3. COMMUNICATION

4.4. LEADERSHIP

- making vaccination a condition of employment

- requiring proof of vaccination when entering public places and when travelling

- Providing financial incentives for those who had been vaccinated, either through gift vouchers or raffles of large sums of money [89].

4.5. CRITICAL THINKING

- Monitoring the transmission of information and the impact of disinformation

- Strengthening the critical thinking of the general population by increasing their digital and scientific literacy.

- Fact-checking and peer-reviewing information.

- Valid and accurate transfer of knowledge to avoid its distortion by commercial or political interests [63].

4.6. INNOVATION

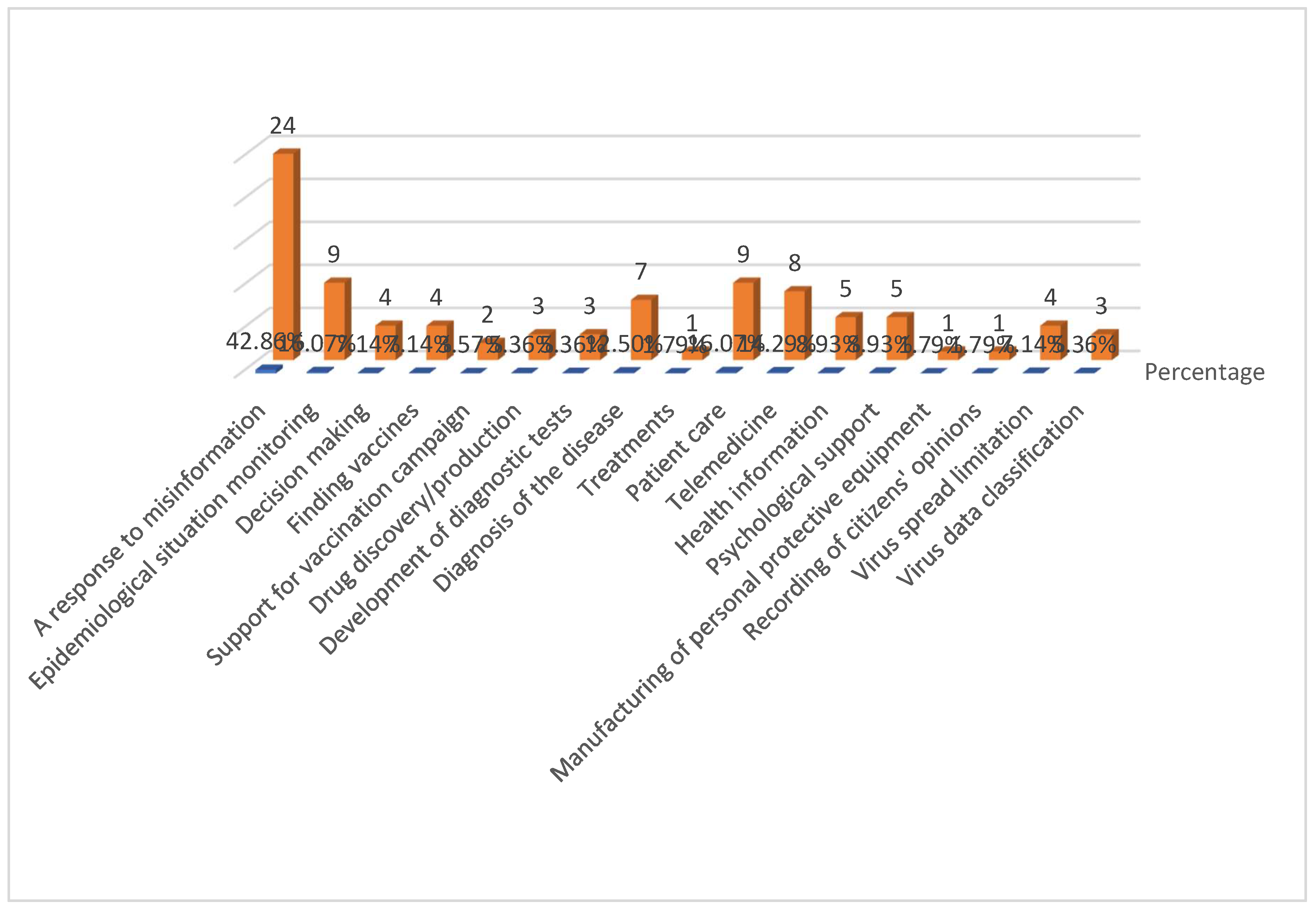

5. THE CONTRIBUTION OF STEM PROFESSIONS TO OVERCOMING THE CRISIS

5.1. THE NEED FOR A MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH.

5.2. THE CONTRIBUTION OF SCIENCE

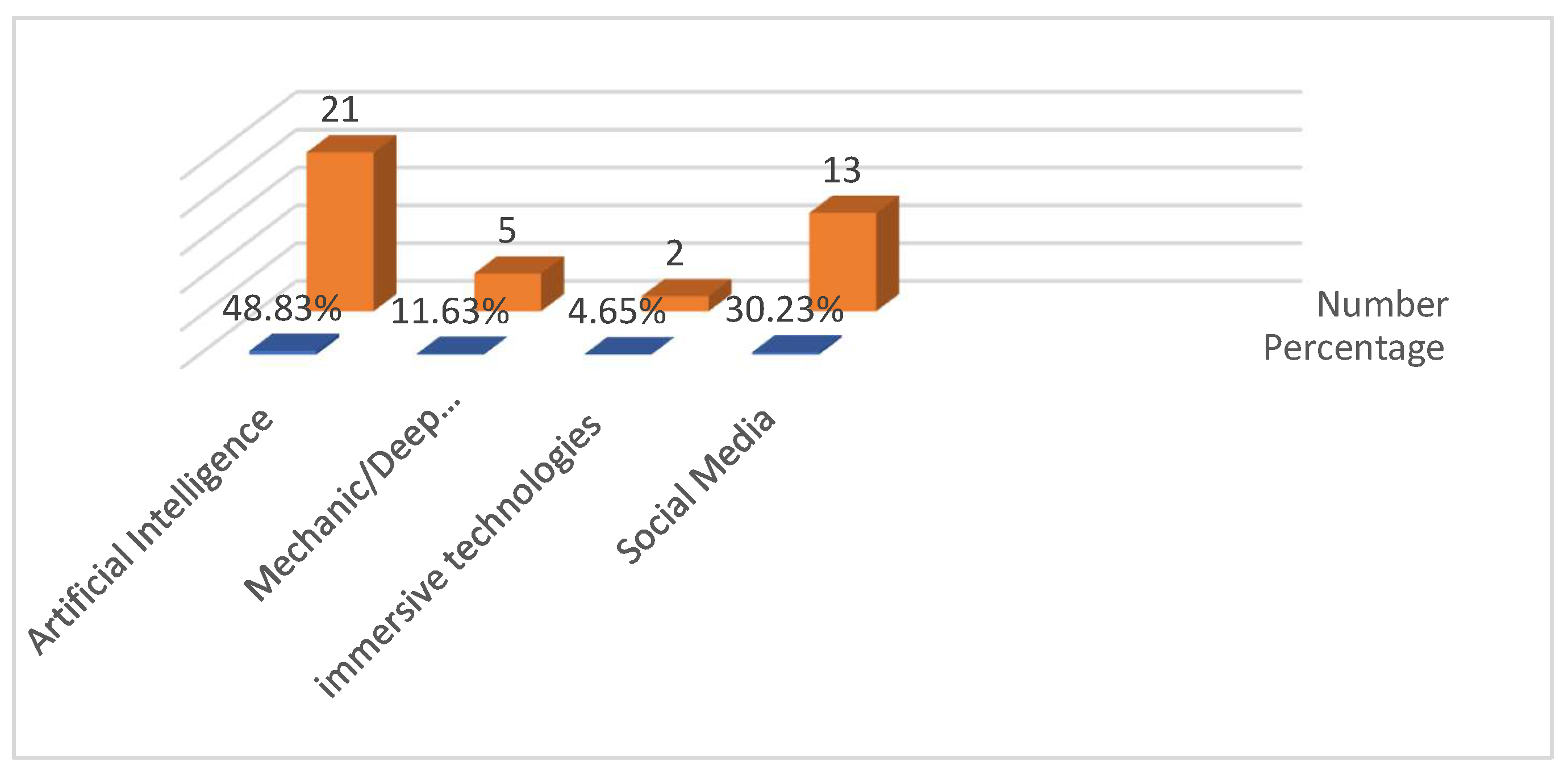

5.3. CONTRIBUTION OF TECHNOLOGY

- Making decisions on policy formulation [16]

- Finding treatments [58],

- Production of personal protection equipment [6],

- Gathering citizens' opinions on the burning issues of the time [79].

- Nanotechnology [6],

- Software [16] ,

- Immersive technologies [90],

- Artificial intelligence [72],

- Machine learning [62],

- Electronic Systems [81],

- Software [16],

- Programming languages [87].

5.4. THE CONTRIBUTION OF MATHEMATICS

- deterministic models [16]

- Patient care [17],

- Decision making [16],

- Monitoring compliance with preventive measures [76].

- Communicating accurate information [67],

- providing psychological support, limiting negative emotions [67].

References

- Gündüz, A.Y. The Importance of Investigating Students’ Lifelong Learning Levels and Perceptions of 21st-Century Skills. Int. e-Journal Educ. Stud. 2023, 7, 788–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Dishon and T. Gilead, "Adaptability and its discontentsQ 21st- century skills and the preparation for an unpredictadle futer," British Journal of Educational Studies, pp. 1-21, 2020.

- T. Oon-Seng, Problem-Based Learning Innovation: Using Problems to Power Learning in the 21st Century, Cengage Learning, 2023.

- E. van Laar,. A. J. A. M. van Deursen, J. A. G. M. van Dijk and J. de Haan, "Determinants of 21st-Century Skills and 21st-Century Digital Skills for Workers: A Systematic Literature Review.," SAGE Open, vol. 10, no. 1, 2020.

- Garavand, A.; Ameri, F.; Salehi, F.; Talebi, A.; Karbasi, Z.; Sabahi, A. A Systematic Review of Health Management Mobile Applications in COVID-19 Pandemic: Features, Advantages, and Disadvantages. Biomed Res Int. 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.; Pathak, S.; Premkumar, M.; Sarpparajan, C.; Balaji, R.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Banerjee, A. A brief overview of SARS-CoV-2 infection and its management strategies: a recent update. Mol Cell Biochem. 2024, 479, 2195–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanchetta, M.S.; de Paula, C.M.; Moraes, K.L.; Santos, W.S.; Linhares, F.M.P.; Oliveira, L.M.d.A.C.; Brasil, V.V.; Viduedo, A.d.F.S. Innovations in the practice of Brazilian community health nursing during the pandemic: a rapid review. Esc. Anna Nery 2024, 28, e20240011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Guo, W.; Yin, X.; Liu, L.; Huang, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, L. Innovative applications of artificial intelligence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Infect. Med. 2024, 3, 100095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-Y.; Su, S.-B.; Chen, K.-T. Surveillance strategies for SARS-CoV-2 infections through one health approach. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwachukwu, G.; Rihan, A.; Nwachukwu, E.; Uduma, N.; Elliott, K.S.; Tiruneh, Y.M. Understanding COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in the United States: A Systematic Review. Vaccines 2024, 12, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussna, A.U.; Alam, G.R.; Islam, R.; Alkhamees, B.F.; Hassan, M.M.; Uddin, Z. Dissecting the infodemic: An in-depth analysis of COVID-19 misinformation detection on X (formerly Twitter) utilizing machine learning and deep learning techniques. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afyouni, I.; Hashim, I.; Aghbari, Z.; Elsaka, T.; Almahmoud, M.; Abualigah, L. Insights from the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Survey of Data Mining and Beyond. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2024, 17, 1359–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsmadi, I.; Rice, N.M.; O’brien, M.J. Fake or not? Automated detection of COVID-19 misinformation and disinformation in social networks and digital media. Comput. Math. Organ. Theory 2022, 30, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agampodi, S.; Mogeni, O.D.; Chandler, R.; Pansuriya, M.; Kim, J.H.; Excler, J.-L. Global pandemic preparedness: learning from the COVID-19 vaccine development and distribution. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2024, 23, 761–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Qaf’an, E.; Alford, S.; Porteous, K.; Lim, D. Healthcare Decision-Making in a Crisis: A Qualitative Systemic Review Protocol. Emerg. Med. Int. 2024, 2024, 2038608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lais, R.S.; Fitzner, J.; Lee, Y.-K.; Struckmann, V. Open-sourced modeling and simulating tools for decision-makers during an emerging pandemic or epidemic – Systematic evaluation of utility and usability: A scoping review update. Dialog- Heal. 2024, 5, 100189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomer, S. Munigala, C. Coles and et al., "he response of the Military Health System (MHS) to the COVID-19 pandemic: a summary of findings from MHS reviews. Health Res Policy Sys 2024, 22.

- H. Nouira, O. Jaoued, I. Ouanes,. M. Jrad, S. Chtioui, R. Gharbi, M. Fekih Hassen, H. Ben Sik Ali and S. Elatrous, "Implementation of simulation training in the Intensive Care Units (ICU) during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review.," La Tunisie medicale 2024, 102, 433–439.

- BAŞAR, F.B.; Teacher, B.P.D.O.N.E.; Ada, Ş. The Relationship between eTwinning Activities and 21st Century Education and Teaching Skills. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Res. Stud. 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, H.M. The Importance of Adaptability for the 21st Century. Society 2015, 52, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD Skills Strategy 2019, skillas to shape a better future. 2019 OECD Skills Strategy: Greece," OECD, 2019.

- L. Gonzalez-Perez and M. Ramirez-Montoya, "Components of Education 4.0 in 21st Century Skillw Frameworkw: Systematic Reviw," Sustainability 2022, 14, 1493.

- Ab Ghani, S.; Awang, M.M.; Ajit, G.; Rani, M.A.M. Participation in Co-Curriculum Activities and Students’ Leadership Skills. J. Southwest Jiaotong Univ. 2020, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partnership for 21st Century Skills. Framework for 21st Century Learning.," 2019.

- Lin, K.-Y.; Yeh, Y.-F.; Hsu, Y.-S.; Wu, J.-Y.; Yang, K.-L.; Wu, H.-K. STEM education goals in the twenty-first century: Teachers’ perceptions and experiences. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2022, 33, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meirbekov, A.; Maslova, I.; Gallyamova, Z. Digital education tools for critical thinking development. Think. Ski. Creativity 2022, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Heystek, The implementation of problem-based learning to foster pre-service teachers' critical thinking in education for sustainable development, North-West University, 2021.

- van der Zanden, P.J.A.C.; Denessen, E.; Cillessen, A.H.N.; Meijer, P.C. Fostering critical thinking skills in secondary education to prepare students for university: teacher perceptions and practices. Res. Post-Compulsory Educ. 2020, 25, 394–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaleh, N.J. Teaching Critical Thinking Skills: Literature Review. The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology 2020, 19. [Google Scholar]

- P. Ellerton and R. Kelly, "Creativity and Critical Thinking," Education in 21st Century, pp. 7-27, 2021.

- Perera, T. Developing the Critical Thinking Skill of Secondary Science Students in Sri Lanka. Global Comparative EducationQ Journal of the WCCES 2022, 6, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Jia, Q. Twenty years of research development on teachers’ critical thinking: Current status and future implications—A bibliometric analysis of research articles collected in WOS. Think. Ski. Creativity 2023, 48, 101252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, Y.J.F.; Barriga, A.M.; Díaz, R.A.L.; Cuesta, J.A.G. Teacher education and critical thinking: Systematizing theoretical perspectives and formative experiences in Latin America. Rie-Revista De Investig. Educ. 2021, 39, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misbah, M.; Hamidah, I.; Sriyati, S.; Samsudin, A. A bibliometric analysis: research trend of critical thinking in science education. Journal of Engineering Science and Technology 2022, 118–126. [Google Scholar]

- Rubini, B.; Septian, B.; Permana, I. Enhancing critical thinking through the science learning on using interactive problem based module. J. Physics Conf. Ser. 2019, 1157, 022001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, A.; Ay, Ş.Ç. How to teach critical thinking: an experimental study with three different approaches. Learn. Environ. Res. 2022, 26, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, R.G.; Cavera, V.L.; Chinn, C.A. The Role of Evidence Evaluation in Critical Thinking: Fostering Epistemic Vigilance. In: Puig, B., Jiménez-Aleixandre, M.P. (eds) Critical Thinking in Biology and Environmental Education. Contributions from Biology Education Research.," Springer, Cham., 2022.

- Boyraz, S. A scale development study for one of the 21st centuryskills: Collaboration at secondary schools. African Educational Research Journal 2021, 9, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Salmons and L. A. Wilson, Learning to Collaborate, Collaborating to Learn, New York: Routledge, 2019.

- Petre, G.-E. Developing Students’ Leadership Skills Through Cooperative Learning: An Action Research Case Study. International Forum 2020, 23, 143–162. [Google Scholar]

- Channing, J. How Can Leadership Be Taught? Implications for Leadership Educators. International Journal of Educational Leadership Preparation 2020, 15, 134–148. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, L.L. The Importance of Teacher Leadership Skills in the Classroom. Educ. J. 2021, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmuti, D.; Minnis, W.; Abebe, M. Does education have a role in developing leadership skills? Manag. Decis. 2005, 43, 1018–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muammar, O. Exploring students’ perceptions of leadership skills in higher education: An impact study of the leadership training program. Gift. Educ. Int. 2021, 38, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Leal, R.; Holzer, A.A.; Bradley, C.; Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Patti, J. The relationship between emotional intelligence and leadership in school leaders: a systematic review. Camb. J. Educ. 2021, 52, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirotiak, T.; Sharma, A. Problem-Based Learning for Adaptability and Management Skills. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pr. 2019, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M.L.; Porfeli, E.J. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. M. Breiner, C. C. J. M. Breiner, C. C. Johnson, S. S. Harkness and C. M. Koehler, "What Is STEM? A Discussion About Conceptions of STEM in Education and Partnerships.," School Science and Mathematics, Jan 2012.

- Bybee, R.W. What Is STEM Education? Science 2010, 329, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Tytler, J. Aderson and Y. Li, "STEM Education for the Twenty-First Century.," in Integrated Approaches to STEM Education: An International Perspective, Cham, Springer International Publishing, 2020, pp. 21-43.

- Maass, K.; Geiger, V.; Ariza, M.R.; Goos, M. The Role of Mathematics in interdisciplinary STEM education. ZDM – Math. Educ. 2019, 51, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Yakman and H. Lee, "Exploring the Exemplary STEAM Education in the U.S. as a Practical Educational Framework for Korea," Journal of The Korean Association For Science Education, Aug 2012.

- UNESCO, Embracing a culture of lifelong learning, Germany: UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learnin, 2020.

- Ankolekar, A.; Eppings, L.; Bottari, F.; Pinho, I.F.; Howard, K.; Baker, R.; Nan, Y.; Xing, X.; Walsh, S.L.; Vos, W.; et al. Using artificial intelligence and predictive modelling to enable learning healthcare systems (LHS) for pandemic preparedness. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 24, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. Chaufan, N. Hemsing, C. Heredia and. J. McDonald, "Trust Us—We Are the (COVID-19 Misinformation) Experts: A Critical Scoping Review of Expert Meanings of “Misinformation” in the Covid Era. COVID 2024, 4, 1413–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuheirwe, M.; Otim, R.; Male, K.J.; Ahimbisibwe, S.; Sackey, J.D.; Sande, O.J. Misinformation, knowledge and COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: a cross-sectional study among health care workers and the general population in Kampala, Uganda. BMC Public Heal. 2024, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See, K.C. Enhancing COVID-19 Vaccination Awareness and Uptake in the Post-PHEIC Era: A Narrative Review of Physician-Level and System-Level Strategies. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arevalo-Romero, J.A.; Chingaté-López, S.M.; Camacho, B.A.; Alméciga-Díaz, C.J.; Ramirez-Segura, C.A. Next-generation treatments: Immunotherapy and advanced therapies for COVID-19. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulla, N.; Soltane, R.; Alasiri, A.; Allayeh, A.K.; Taha, A.; Alshehri, F.; Alrokban, A.H.; Zaghloo, S.S.; Zayan, A.Z.; Abdalla, K.F.; Sayed, A.M. Advancements in SARS-CoV-2 detection: Navigating the molecular landscape and diagnostic technologies. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheisari, M.; Ghaderzadeh, M.; Li, H.; Taami, T.; Fernández-Campusano, C.; AbbasI, A.A. Mobile Apps for COVID-19 Detection and Diagnosis for Future Pandemic Control: Multidimensional Systematic Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, L. Cuypers, L. Laenen and et al., "Nationwide quality assurance of high-throughput diagnostic molecular testing during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: role of the Belgian National Reference Centre. Virol J. 2024, 21.

- Koksaldi, I.C.; Park, D.; Atilla, A.; Kang, H.; Kim, J.; Seker, U.O.S. RNA-Based Sensor Systems for Affordable Diagnostics in the Age of Pandemics. ACS Synth. Biol. 2024, 13, 1026–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Kisa and A. Kisa, "A Comprehensive Analysis of COVID-19 Misinformation, Public Health Impacts, and Communication Strategies: Scoping Review. J Med Internet Res 2024.

- D. Kbaier, A. Kane, M. McJury and I. Kenny, "Prevalence of Health Misinformation on Social Media—Challenges and Mitigation Before, During, and Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic: Scoping Literature Review,". J Med Internet Res. 2024.

- Yang, L.; Lu, S.; Zhou, L.; Prevention, B.C.C.F.D.C.A. The Implications of Artificial Intelligence on Infection Prevention and Control: Current Progress and Future Perspectives. China CDC Wkly. 2024, 5, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterworth, J.; Smerdon, D.; Baumeister, R.; von Hippel, W. Cooperation in the Time of COVID. ," Perspectives on psychological science : a journal of the Association for Psychological Science 2024, 19, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeem, J.; Gul, O.M.; Parlak, I.B.; Karpouzis, K.; Salman, Y.B.; Kadry, S.N. Detection of Misinformation Related to Pandemic Diseases using Machine Learning Techniques in Social Media Platforms. EAI Endorsed Trans. Pervasive Heal. Technol. 2024, 10, 6459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Rasmussen,. L. Lindekilde and M. B. Petersen, "Public Health Communication Reduces COVID-19 Misinformation Sharing and Boosts Self-Efficacy.," Journal of Experimental Political Science 2024, 11, 327–342.

- Lytton, S.; Ghosh, A. SARS-CoV-2 Variants and COVID-19 in Bangladesh—Lessons Learned. Viruses 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizumi, A.; Kolis, J.; Abad, N.; Prybylski, D.; A Brookmeyer, K.; Voegeli, C.; Wardle, C.; Chiou, H. Beyond misinformation: developing a public health prevention framework for managing information ecosystems. Lancet Public Heal. 2024, 9, e397–e406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, Z. COVID-19 Misinformation on Social Media and Public’s Health Behavior: Understanding the Moderating Role of Situational Motivation and Credibility Evaluations. Hum. Arenas 2022, 7, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirani, R.; Noruzi, K.; Hussaini, A.; Aifuwa, E.; Ely, K.; Lewis, J.; Gabr, A.; Smiley, A.; Tiwari, R. Artificial Intelligence and Healthcare: A Journey through History, Present Innovations, and Future Possibilities. Life 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussna, A.U.; Islam, R.; Alam, G.R.; Uddin, J.; Ashraf, I.; Samad, A. A graph mining-based approach to analyze the dynamics of the Twitter community of COVID-19 misinformation disseminators. ICT Express 2024, 10, 1280–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakene, A.D.; Cooper, L.N.; Hanna, J.J.; Perl, T.M.; Lehmann, C.U.; Medford, R.J. A pandemic of COVID-19 mis- and disinformation: manual and automatic topic analysis of the literature. Antimicrob. Steward. Heal. Epidemiology 2024, 4, e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.; Newell, R.; Babu, G.R.; Chatterjee, T.; Sandhu, N.K.; Gupta, L. The social media Infodemic of health-related misinformation and technical solutions. Heal. Policy Technol. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardasevic, S.; Jaiswal, A.; Lamba, M.; Funakoshi, J.; Chu, K.-H.; Shah, A.; Sun, Y.; Pokhrel, P.; Washington, P. "Public Health Using Social Network Analysis During the COVID-19 Era: A Systematic Review. Information, 2024; 15. [Google Scholar]

- Zaheer, H.; Bashir, M. Detecting fake news for COVID-19 using deep learning: a review. Multimedia Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 74469–74502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, S.; Hadi, H.J.; Ahmad, N.; Alshara, M.A. Fake News Detection Revisited: An Extensive Review of Theoretical Frameworks, Dataset Assessments, Model Constraints, and Forward-Looking Research Agendas. Technologies 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhaloob, L.; Purnat, T.D.; Tabche, C.; Atwan, Z.; Dubois, E.; Rawaf, S. Management of infodemics in outbreaks or health crises: a systematic review. Front. Public Heal. 2024, 12, 1343902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Chandler, R.; Balakrishnan, M.R.; Brasseur, D.; Bryan, P.; Espie, E.; Hartmann, K.; Jouquelet-Royer, C.; Milligan, J.; Nesbitt, L.; Pal, S.; et al. Collaboration within the global vaccine safety surveillance ecosystem during the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learnt and key recommendations from the COVAX Vaccine Safety Working Group. BMJ Glob. Heal. 2024, 9, e014544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, R.; Carlson, H.; Geduld, H.; Nyasulu, J.C.Y.; Quinette, L.; Karina, B.; Yvonne, C.M.; Michele, P.; Michael, M.; Conran, J.; Nina, G.; Lucy, B.L.; Emiroglu, N. Defining and identifying the critical elements of operational readiness for public health emergency events: a rapid scoping review. BMJ Global Health, 2024; 9. [Google Scholar]

- Mosadeghrad, A.M.; Afshari, M.; Isfahani, P.; Ezzati, F.; Abbasi, M.; Farahani, S.A.; Zahmatkesh, M.; Eslambolchi, L. Strategies to strengthen the resilience of primary health care in the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhsen, K.; Cohen, D.; Glatman-Freedman, A.; Husseini, S.; Perlman, S.; McNeil, C. Review of Israel’s action and response during the COVID-19 pandemic and tabletop exercise for the evaluation of readiness and resilience—lessons learned 2020–2021. Front. Public Heal. 2024, 11, 1308267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenta, E.T.; Bogale, E.K.; Anagaw, T.F. The role of social media on COVID-19 preventive behaviors worldwide, systematic review. PloS one 2024, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Cuadros, D.F.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Omori, R.; Musuka, G. Advancing Public Health Surveillance: Integrating Modeling and GIS in the Wastewater-Based Epidemiology of Viruses, a Narrative Review. Pathogens 2024, 13, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, C.; Holzscheiter, A.; Kickbusch, I. Germany's role in global health at a critical juncture. The Lancet 2024, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herre, B.; Rodés-Guirao, L.; Mathieu, E.; Ritchie, H.; Giattino, C.; Hasell, J.; Dattani, S.; Ortiz-Ospina, E.; Roser, M. Best practices for government agencies to publish data: lessons from COVID-19. Lancet Public Heal. 2024, 9, e407–e410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boylan, S.; Arsenault, C.; Barreto, M.; A Bozza, F.; Fonseca, A.; Forde, E.; Hookham, L.; Humphreys, G.S.; Ichihara, M.Y.; Le Doare, K.; et al. Data challenges for international health emergencies: lessons learned from ten international COVID-19 driver projects. Lancet Digit. Heal. 2024, 6, e354–e366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayaz-Farkhad, B.; Jung, H. Do COVID-19 Vaccination Policies Backfire? The Effects of Mandates, Vaccination Passports, and Financial Incentives on COVID-19 Vaccination. Perspectives on Psychological Science 2024, 19, 660–674. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khan, H.U.; Ali, Y.; Khan, F.; Al-Antari, M.A. A comprehensive study on unraveling the advances of immersive technologies (VR/AR/MR/XR) in the healthcare sector during the COVID-19: Challenges and solutions. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calistri, A.; Roggero, P.F.; Palù, G. Chaos theory in the understanding of COVID-19 pandemic dynamics. Gene 2024, 912, 148334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeamii, V.C.; E Okobi, O.; Wambai-Sani, H.; Perera, G.S.; Zaynieva, S.; Okonkwo, C.C.; Ohaiba, M.M.; William-Enemali, P.C.; Obodo, O.R.; Obiefuna, N.G. Revolutionizing Healthcare: How Telemedicine Is Improving Patient Outcomes and Expanding Access to Care. Cureus 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alashek, W.; Ali, S. Satisfaction with telemedicine use during COVID-19 pandemic in the UK: a systematic review. Libyan J. Med. 2024, 19, 2301829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, M.; Zare, Z.; Mojtabaeian, S.M.; Izadi, R. Artificial Intelligence and Decision-Making in Healthcare: A Thematic Analysis of a Systematic Review of Reviews. Heal. Serv. Res. Manag. Epidemiology 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarela, M.; Podgorelec, V. Recent Applications of Explainable AI (XAI): A Systematic Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ( “Covid19 crisis” OR “Covid19 pandemic” OR “health crisis”) AND (“management of crisis” OR “COVID management”) OR (“end of pandemic” OR “end of pandemic COVID”) OR (COVID19 misinformation”) OR (“COVID19 solutions”) OR (COVID19 and technology”) |

|

| S.N. | TITLE | COUNTRY- YEAR | Type of study | sample | method | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A Comprehensive Analysis of COVID-19 Misinformation, Public Health Impacts, and Communication Strategies: Scoping Review | 2024 Norway |

Scoping Review | 21 articles | PRISMA-ScR | Misinformation had a significant impact on mental health, vaccine hesitancy and health care decisions. Social and traditional media were important channels for the spread of misinformation. |

| 2 | Chaos theory in the understanding of COVID-19 pandemic dynamics | 2024 Italy |

Article | Bibliographic Review |

Insights from Chaos Theory highlight the importance of flexibility and adaptability in responding strategies. | |

| 3 | Systematic Review of Health Management Mobile Applications in COVID-19 Pandemic: Features, Advantages, and Disadvantages. | 2024 Iran |

Systematic Review | 12 articles | PRISMA | The most common advantages of the app were disease management and the ability to record information from users, digital call monitoring and privacy. The most common disadvantages were lower compliance with daily symptom reporting, personal interpretation of questions and bias in results. |

| 4 | Innovative applications of artificial intelligence during the COVID-19 pandemic, | 2024 China |

Systematic Review | Bibliographic Review |

AI enables prediction, diagnosis, decision support for COVID-19 response and control. Intelligent systems support risk analysis and policy making to combat COVID-19. Multidisciplinary collaboration is essential for responsible AI solutions against COVID-19. |

|

| 5 | SARS-CoV-2 Variants and COVID-19 in Bangladesh—Lessons Learned. | 2024 Bangladesh |

Article | Bibliographic Review |

The legacy of COVID-19 pandemic is a multifaceted impact on human life and an unprecedented international response to a shared global predicament. Open access to information fascillitated understanding of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the COVID-19 illness. | |

| 6 | Next-generation treatments: Immunotherapy and advanced therapies for COVID-19 | 2024 Colombia |

Article | Bibliographic Review |

Extensive research and global cooperation have provided a profound understanding of the fundamental biological and molecular characteristics of SARS-CoV-2. This knowledge has proven invaluable in guiding the development of biotechnological approaches and preventive measures, particularly vaccin | |

| 7 | Satisfaction with telemedicine use during COVID-19 pandemic in the UK: a systematic review | 2024 United Kingdom |

Systematic Review | 27 eligible studies | PRISMA | COVID-19 pandemic has transformed healthcare in the UK and promoted a revolution in telemedicine applications. Satisfaction was high among both recipient and provider of healthcare. Telemedicine managed to provide a continued care throughout the pandemic while maintaining social distance. |

| 8 | Mobile Apps for COVID-19 Detection and Diagnosis for Future Pandemic Control: Multidimensional Systematic Review | 2024 China Iran USA Chile Italy |

Multidimensional Systematic Review | 42 studies | PRISMA | Mobile apps could soon play a significant role as a powerful tool for data collection, epidemic health data analysis, and the early identification of suspected cases. These technologies can work with the internet of things, cloud storage, 5th-generation technology, and cloud computing. |

| 9 | Prevalence of Health Misinformation on Social Media—Challenges and Mitigation Before, During, and Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic: Scoping Literature Review | 2024 UK |

Scoping Literature Review | 70 sources | Arksey and O’Malley’s methodology | It highlights the necessity for a collaborative global interdisciplinary effort to ensure equitable access to accurate health information, thereby empowering health practitioners to effectively combat the impact of online health misinformation. |

| 10 | Strategies to strengthen the resilience of primary health care in the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review | 2024 Iran UK |

a scoping review | 167 articles | Arksey and O’Malley’s methodology | The study underscored the need for well-resourced, managed, and adaptable PHC systems, capable of maintaining continuity in health services during emergencies. The identified interventions suggested a roadmap for integrating resilience into PHC, essential for global health security. |

| 11 | Enhancing COVID-19 Vaccination Awareness and Uptake in the Post-PHEIC Era: A Narrative Review of Physician-Level and System-Level Strategies. | 2024 Singapore |

Narrative Review | Vaccination remains crucial in reducing the spread and severity of the disease. To tackle challenges such as incomplete vaccination coverage and vaccine hesitancy, various physician-level and system-level strategies have been implemented. These strategies aim to improve access to vaccines, combat misinformation, and enhance vaccine uptake. | ||

| 12 | Germany's role in global health at a critical juncture |

2024 Germany |

Review | Germany's role in global health has further expanded. It has lived up to many of its earlier promises and claims: it has upheld multilateral solutions to global health challenges, increased its financial contributions significantly, and successfully advocated with others for the EU's stronger engagement on global health. At the same time, Germany remains politically one of the strongest defenders of the present intellectual property rights system. | ||

| 13 | The response of the Military Health System (MHS) to the COVID-19 pandemic: a summary of findings from MHS reviews | 2024 USA |

narrative literature review | 16 internal Department of Defense reports, reviews by the US Congress | narrative review | similar to the US civilian sector, the MHS also experienced delays in care, staffing and materiel challenges, and a rapid switch to telehealth. Lessons regarding the importance of communication and preparation for future public health emergency responses are relevant to civilian healthcare systems responding to COVID-19 and other similar public health crises. |

| 14 | Understanding COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in the United States: A Systematic Review | 2024 USA |

Systematic Review | 544 studies | PRISMA And 5C model of vaccine hesitancy |

By understanding and mitigating the predictors of hesitancy and reinforcing the factors that encourage uptake, we can improve vaccination rates and advance public health objectives. Future research should continue to explore these dynamics and develop tailored strategies that resonate with diverse populations, ultimately fostering a more robust and resilient public health response to COVID-19 and beyond. |

| 15 | Artificial Intelligence and Healthcare: A Journey through History, Present Innovations, and Future Possibilities | 2024 USA |

Review | On the telemedicine front, the text delves into its pivotal role, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Telemedicine, encompassing real-time and store-and-forward methodologies, has become a crucial tool, enhancing accessibility, reducing healthcare expenditures, and mitigating unnecessary exposure to infections. | ||

| 16 | Do COVID-19 Vaccination Policies Backfire? The Effects of Mandates, Vaccination Passports, and Financial Incentives on COVID-19 Vaccination | 2024 USA |

Research article | 43 articles | stress the importance of complementing incentive policies with other provaccine policies and/or communication strategies that promote positive attitudes toward vaccination. For example, financial incentives are more effective in increasing intentions to vaccinate when they are coupled with communication strategies that emphasize personal freedom gained from vaccination and other measures that increased access to vaccination (e.g., the ability to get vaccines from local doctors | |

| 17 | Beyond misinformation: developing a public health prevention framework for managing information ecosystems | 2024 USA |

Review article | Addressing infodemics through the preventive lens of public health offers several advantages. This framework expands the scope of infodemic management beyond emergency response, while still recognising its importance, and emphasises the need to develop upstream interventions before public health emergencies occur. Furthermore, this breadth encourages public health professionals to consider developing interventions beyond only responding to misinformation, such as debunking or other communication interventions. | ||

| 18 | A comprehensive study on unraveling the advances of immersive technologies (VR/AR/MR/XR) in the healthcare sector during the COVID-19: Challenges and solutions | 2024 Qatar |

comprehensive study | 220 | PRISMA | Immersive technologies supporting different apps, hardware platforms, tools, devices, platforms, architectures and with other technologocal support helped in overcoming this pandemic. These technologies covered almost every field related to the healthcare industry ranging from medical training to the cognitive rehabilitation. These technologies enabled healthcare professionals to experience immersive, interactive, 3D modeling, simulation, feedback, collaborative, efficient, effective and flexible means to perform different healthcare tasks during current pandemic of COVID-19. |

| 19 | Review of Israel’s action and response during the COVID-19 pandemic and tabletop exercise for the evaluation of readiness and resilience—lessons learned 2020–2021 | 2024 Israil |

Review Article | DART analysis | Our study appraised strengths and weaknesses of the COVID-19 pandemic response in Israel and led to concrete recommendations for adjusting responses and future similar events. An efficient response comprised multi-sectoral collaboration, policy design, infrastructure, care delivery, and mitigation measures, including vaccines, while risk communication, trust issues, and limited cooperation with minority groups were perceived as areas for action and intervention. | |

| 20 | Data challenges for international health emergencies: lessons learned from ten international COVID-19 driver projects |

2024 UK USA Brazil |

Use of pre-provisioned trusted research environments can go a long way to opening up data sharing across national and regional boundaries; expediting this process can be crucial in research areas such as rare diseases, where national datasets might be too small to give rise to significant results. It also provides a good mechanism for reducing the risk involved in data sharing, as the data remains within a secure environment at all times. Use of data curation expertise early on in initiatives can accelerate progress as this step is typically time-consuming and often underestimated. As part of this curation, considering making data findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable at the same time and considering field labelling and units can reduce the work involved in sharing metadata. |

|||

| 21 | Healthcare Decision-Making in a Crisis: A Qualitative Systemic Review Protocol | 2024 Australia |

Review Article | PRISMA | Although public health crises impose a drastic burden on society and the individual, effective decision-making by healthcare leaders can act to minimize harm, saving the lives and livelihoods of entire communities. | |

| 22 | Nationwide quality assurance of high-throughput diagnostic molecular testing during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: role of the Belgian National Reference Centre | 2024 Belgium |

Review Article | Thanks to a nationwide collaboration between the NRC UZ/KU Leuven, Sciensano, the Belgian government, the newly established testing platforms and all clinical laboratories, Belgium effectively responded to the high demand for COVID-19 testing during the ongoing pandemic. Initially, diagnostic testing for SARS-CoV-2 was solely conducted at the NRC. However, clinical laboratories swiftly implemented SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic assays with the support and technical expertise of the NRC. Nonetheless, this proved insufficient to meet the testing demand during Belgium’s initial wave of the epidemic. To facilitate the rapid expansion of testing capacity, the national testing platform was established as an extension of the NRC laboratory. | ||

| 23 | Collaboration within the global vaccine safety surveillance ecosystem during the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learnt and key recommendations from the COVAX Vaccine Safety Working Group | 2024 Switzerland Belgium France UK South Africa Brazil USA |

Analysis | Vaccine safety data sharing is essential between all stakeholders in the vaccine ecosystem to ensure equitable access to evidence for decision-making. For data to provide relevant insights for risk management, there must be comprehensive mechanisms in place to ensure vaccine safety data and/or knowledge of safety data gaps can be readily shared and used. Information exchange regarding post-licensure safety knowledge gaps could allow for collaborative efforts to generate the necessary data required for local regulatory benefit/risk decision-making. The resources required for efficient generation of high-quality evidence require involvement of the industry. | ||

| 24 | Open-sourced modeling and simulating tools for decision-makers during an emerging pandemic or epidemic – Systematic evaluation of utility and usability: A scoping review update | 2024 Germany |

scoping review | 29 articles | PRISMA | Tool usage can enhance decision-making when adapted to the user's needs and purpose. They should be consulted critically rather than followed blindly. |

| 25 | A brief overview of SARS-CoV-2 infection and its management strategies: a recent update | 2024 India |

Article | In the management of the post-COVID era, strategies such as early public participation, dynamic consent, digital literacy improvements, and the appointment of third-party judicial could be considered to facilitate the co-creation of noticeable, trustworthy, and genuine anti-epidemic technologies with mechanisms for transparency and accountability. Thus, it is essential to be well informed on the most recent updates on COVID-like illnesses and diligently follow public health guidelines. This is crucial in safeguarding individual well-being as well as the overall health of the community. | ||

| 26 | Defining and identifying the critical elements of operational readiness for public health emergency events: a rapid scoping review | 2024 South Africa Switzerland (WHO) |

scoping review | 54 peer-reviewed publications and 24 grey literature sources | PRISMA | OPR is in an early stage of adoption. Establishing a consistent and explicit framework for OPRs within the context of existing global legal and policy frameworks can foster coherence and guide evidence-based policy and practice improvements in health emergency management. |

| 27 | Implementation of simulation training in the Intensive Care Units (ICU) during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review | 2024 Tunisia |

A scoping review | 7 articles | PRISMA | Results supported the impact of simulation, in critical care, as an effective method to enhance knowledge and confidence, and to improve protocol development during pandemics such as COVID-19 |

| 28 | Advancing Public Health Surveillance: Integrating Modeling and GIS in the Wastewater-Based Epidemiology of Viruses, a Narrative Review | 2024 USA China Japan Zimbabwe |

Narrative Review | This review concludes by underscoring the transformative potential of these analytical tools in public health, advocating for continued research and innovation to strengthen preparedness and response strategies for future viral threats. This article aims to provide a foundational understanding for researchers and public health officials, fostering advancements in the field of wastewater-based epidemiology. | ||

| 29 | Artificial Intelligence and Decision-Making in Healthcare: A Thematic Analysis of a Systematic Review of Reviews | 2024 Iran |

Thematic Analysis | 18 articles | PRISMA | This study revealed that AI tools have been applied in various aspects of healthcare decision-making. The use of AI can improve the quality, efficiency, and effectiveness of healthcare services by providing accurate, timely, and personalized information to support decision-making. Further research is needed to explore the best practices and standards for implementing AI in healthcare decision-making |

| 30 | Surveillance strategies for SARS-CoV-2 infections through one health approach | 2024 Taiwan |

Review article | 109 studies | PRISMA | The COVID-19 pandemic highlights the new strategy of the One Health approach for managing zoonotic epidemics. The surveillance program using the One Health approach is an important measure to detect the epidemiology of the disease in animals and humans, and it should be possible to determine the role of the various animal species and humans during the pandemic. Based on this information, holistic strategies can be planned to control and prevent this pandemic |

| 31 | RNA-Based Sensor Systems for Affordable Diagnostics in the Age of Pandemics | 2024 Turkey South Korea |

Review article | As the world grapples with the challenges of pandemics and rapid disease outbreaks, the future lies in collaborative efforts at the intersection of molecular biology, engineering, and data science. This interdisciplinary approach will drive the development of RNA-based sensor systems that offer affordable, rapid, and accurate diagnostic solutions, revolutionizing healthcare strategies and bolstering global preparedness for emergent health crises. Ultimately, as we navigate this new age of pandemics, harnessing the power of RNA-based diagnostics is poised to play a pivotal role in safeguarding public health on a global scale. | ||

| 32 | Best practices for government agencies to publish data: lessons from COVID-19 | 2024 UK |

Article | A lot of the data published by government agencies during the pandemic did not follow these best practices. Often, others—such as teams of university researchers, data journalists, and our team at Our World in Data—had to improve available data to make them easier to access and understand. | ||

| 33 | Advancements in SARS-CoV-2 detection: Navigating the molecular landscape and diagnostic technologies | 2024 Saudi Arabia Egypt Iraq |

Review article | The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants, particularly the Delta and Omicron strains, has underscored the critical need for rapid testing technologies. Looking ahead, point-of-care testing (POCT) kits, characterized by their simplicity of use, speed in delivering results, and high specificity and sensitivity, are expected to become standard tools for the screening of infected individuals both at home and within community settings. These kits are poised to play a pivotal role in managing and controlling outbreaks caused by mutant strains. | ||

| 34 | Revolutionizing Healthcare: How Telemedicine Is Improving Patient Outcomes and Expanding Access to Care | 2024 USA Caribbean Nigeria |

systematic review | The findings in this review summarise several key things. First, the rapid expansion of telemedicine, catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic, has profoundly reshaped healthcare delivery, notably in chronic disease management and patient access. | ||

| 35 | Using artificial intelligence and predictive modelling to enable learning healthcare systems (LHS) for pandemic preparedness | 2024 Netherlands Belgium USA United Kingdom |

Review article | AI techniques like machine learning (ML) and natural language processing could be instrumental in unlocking knowledge from data. AI can aid in diagnosis, risk stratification, and prediction of outcomes. Effective communication with stakeholders is essential for translating knowledge into action. | ||

| 36 | Management of infodemics in outbreaks or health crises: a systematic review | 2024 United Kingdom United States Iraq |

Review article | 29 studies | PRISMA | Some countries applied different methods of IM to people’s behaviors. These included but were not limited to launching media and TV conservations, using web and scientific database searches, posting science-based COVID-19 information, implementing online surveys, and creating an innovative ecosystem of digital tools, and an Early AI-supported response with Social Listening (EARS) platform. Most of the interventions were effective in containing the harmful effects of COVID-19 infodemic. However, the quality of the evidence was not robust. |

| 37 | Dissecting the infodemic: An in-depth analysis of COVID-19 misinformation detection on X (formerly Twitter) utilizing machine learning and deep learning techniques | 2024 Bangladesh USA Saudi Arabia Norway |

Research article | 87 | PRISMA | In the domains of community analysis and the detection of fake news, deep learning algorithms and graph mining techniques have proven to be extraordinarily effective and are positioned to bring about a paradigm shift. The ecosystem responsible for propagating fake news connected to COVID-19 is significant and highly collaborative, and its dynamics continue to expand even after the pandemic period. |

| 38 | Trust Us—We Are the (COVID-19 Misinformation) Experts: A Critical Scoping Review of Expert Meanings of “Misinformation” in the Covid Era | 2024 Canada UK |

Review article | 68 references | Arksey και O'Malley | We conclude that, at a minimum, continuing efforts to identify, manage, or suppress MDM blunt much-needed democratic and open debate about matters of major social relevance in public health matters and beyond. |

| 39 | Insights from the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Survey of Data Mining and Beyond | 2024 UAE Saudi Arabia Jordan |

In conclusion, although it is very hard to find any positive impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on most of the sectors that touched our lives, from sociological and health perspectives to the economic crash, and at personal and community levels, one can appraise the huge effort made by the scientific community in an attempt to alleviate such disastrous impact. This survey covered the main technical contributions from data mining perspectives, focusing on social data, contact tracing, medical imaging, and health-related time-series data. We presented the challenges, techniques, and open problems with opportunities that can be tackled soon. | |||

| 40 | The Implications of Artificial Intelligence on Infection Prevention and Control: Current Progress and Future Perspectives | 2024 China |

During the pandemic, AI techniques can be utilized for epidemic forecasting, resource management, and information dissemination to alleviate pressure on hospitals. Furthermore, AI has significantly contributed to the effective dissemination of disease prevention and control information. A notable example is the AI-powered chatbot developed by the World Health Organization, which provided reliable information and helped alleviate public anxiety during the pandemic. | |||

| 41 | A pandemic of COVID-19 mis- and disinformation: manual and automatic topic analysis of the literature | 2024 USA |

868 References |

PRISMA | Our comprehensive analysis reveals a significant proliferation of dis- and misinformation research during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study illustrates the pivotal role of social media in amplifying false information. Research into the infodemic was characterized by negative sentiments. | |

| 42 | Global pandemic preparedness: learning from the COVID-19 vaccine development and distribution | 2024 USA Republic of Korea Sweden |

Perspective | Urgent challenges necessitate advances in vaccine technology and production scale-up, and success relies on global collaboration and strategic investment. Equitable access to vaccines demands global cooperation to overcome distribution challenges and a reformation of intellectual property laws to facilitate agile medical knowledge sharing while still protecting innovators’ rights. Effective vaccination campaigns are contingent on combating misinformation and rigorously assessing the vaccines and vaccination impact on public health |

||

| 43 | The social media Infodemic of health-related misinformation and technical solutions | 2024 India UK Qatar USA |

The COVID-19 Infodemic and associated misinformation may misguide individuals and impact health-related decision-making. The social media algorithms play a key role in determining the propagation of misinformation and future efforts should focus on these attributes of SMPs to combat misinformation. |

|||

| 44 | Public Health Using Social Network Analysis During the COVID-19 Era: A Systematic Review | 2024 USA |

Systematic Review | 51 | PRISMA | Accurate data are crucial for epidemiologists and public health practitioners to understand disease patterns, identify specific risk factors, and develop effective public health interventions. The use of social media data without proper ethical considerations may skew epidemiological findings as the usage of various social media platforms may be more active in certain communities/populations, leading to conclusions that do not accurately represent the broader population |

| 45 | The role of social media on COVID-19 preventive behaviors worldwide, systematic review | 2024 Ethiopia |

Research Article | 32 studies | PRISMA | Social media helps people to seek and share knowledge, connect with others, and find enjoyment and amusement to support preventive behaviors. When searching for information on COVID-19 pandemic prevention, social media exhibited a better predictive capacity. In these urgent times, social media could even help with quick information availability; misinformation or inadequate understanding can cause misunderstandings within the community. |

| 46 | Cooperation in the Time of COVID | 2024 Australia |

Research article | In this brief review, we explored how to leverage understanding of the nature of cooperation to facilitate public health during crises such as pandemics. In service of that goal, we conclude by highlighting three areas in which policies enhanced (or could have enhanced) cooperation by addressing key issues raised in this review, following which we highlight important questions for future research. | ||

| 47 | Detecting fake news for COVID-19 using deep learning: a review | 2024 Pakistan |

Review article | Datasets are explored, various studies are discovered and reviewed multiple approaches which deal with fake news detection using machine learning and deep learning techniques. Although, transformer based models are being widely used and provide state of the art results, hybrid ensembles surpass them. The review has unearthed the fact that people are generally unaware of the steps taken to minimize COVID-19 spread. | ||

| 48 | Innovations in the practice of Brazilian community health nursing during the pandemic: a rapid review | 2024 Canada Brazil |

Review article | 11 articles | PRISMA | Conclusions and implication to the practice the connection between primary health care, academia, and organizations produced simple solutions to unknown, complex, and unpredictable situations. However, the idea of innovation as something unprecedented, untested, and structurally revolutionary, was not extensively identified by this rapid review, due to the conceptual and theoretical fragility of the interventions and projects reported. |

| 49 | Recent Applications of Explainable AI (XAI): A Systematic Literature Review | 2024 Finland Slovenia |

Review article | 512 articles | PRISMA | The findings indicate a dominant trend in health-related applications, particularly in cancer prediction and diagnosis, COVID-19 management, and various other medical imaging and diagnostic uses. |

| 50 | Misinformation, knowledge and COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: a cross-sectional study among health care workers and the general population in Kampala, Uganda | 2024 Uganda USA |

cross-sectional quantitative | 564 study participants | The study showed a negative impact of misinformation on vaccine uptake and could be the most significant contributor to vaccine hesitancy in future vaccine programs. | |

| 51 | Fake News Detection Revisited: An Extensive Review of Theoretical Frameworks, Dataset Assessments, Model Constraints, and Forward-Looking Research Agendas | 2024 China Saudi Arabia |

Review article | 355 studies | he comprehensive analysis of existing FND approaches and techniques have inferred that the literature provides limited automated insights for FND. The proposed methods and techniques in the existing literature undermine the effectiveness of interdisciplinary theories on FN and OSN users. These theories highlight the incitement of intentional and unintentional FND propagation. Thus, designing the FND systems in light of the proposed recommendations that expose FN-related biases and motives is significant. The constant development of publicly available datasets is remarkable. | |

| 52 | COVID-19 Misinformation on Social Media and Public’s Health Behavior: Understanding the Moderating Role of Situational Motivation and Credibility Evaluations | 2024 Bangladesh |

cross-sectional quantitative | 373 study participants | The findings of the study suggest that participants are prone to believe in conspiracy and religious misinformation which ultimately influence them to show COVID-19-negative behavioral responses about maintaining the guidelines proposed by the WHO, CDC, and others. | |

| 53 | Fake or not? Automated detection of COVID-19 misinformation and disinformation in social networks and digital media | 2024 USA |

Given that previous studies have demonstrated a direct link between COVID-19 misinformation and an unwillingness to follow public-health measures, effective application of machine-learning techniques to detect misinformation and disinformation in social and digital platforms is becoming an increasingly important tool in the global fight against the deadly disease. | |||

| 54 | Detection of Misinformation Related to PandemicDiseases using Machine Learning Techniques in Social Media Platforms | 2024 Turkey Greece Norway United Arab Emirates Lebanon |

Research Article | During the COVID-19 pandemic, this study analyzed sentiment on Instagram and Facebook using conventional machine learning methods and employed deep learning techniques for Twitter and YouTube due to their unstructured content. The research introduced stacking ensemble learning to enhance sentiment analysis accuracy by combining machine and deep learning models; this method proved to be the best method for improving the accuracy for Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube content, improving detection accuracy | ||

| 55 | A graph mining-based approach to analyze the dynamics of the Twitter community of COVID-19 misinformation disseminators | 2024 Bangladesh USA Republic of Korea |

Our effort leads to the following key findings: (a) COVID-19-related misinformation still persists; (b) misinformation is primarily disseminated through retweets; (c) a small group of individuals (3%) are responsible for a significant portion of the spread; (d) these individuals tend to form distinct communities, and we have identified five major ones. | |||

| 56 | Public Health Communication Reduces COVID-19 Misinformation Sharing and Boosts Self-Efficacy | 2024 Denmark |

2.232 | accuracy nudges |

he analyses showed that while the accuracy nudge and a 15-second capability-oriented intervention significantly increased sharing discernment – that is, the relative sharing of real vs. false headlines – they did not have a significant effect on neither false or real headline sharing compared to the control condition. The 3-minute capability-oriented intervention significantly increased sharing discernment and self-efficacy and reduced false headline sharing. In sum, we found mixed support for effectiveness of short capability-oriented messages and accuracy nudges against misinformation. |

| SN | Title | DOI | reason for rejection |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Adaptation of Digital Health Solutions During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Hungary: A Scoping Review | https://doi.org/10.34172/ijhpm.7940 | It looks at the legislative interventions that have facilitated telemedicine. |

| 2 | COVID-19 Pandemic Risk Assessment: Systematic Review | 10.2147/RMHP.S444494 | Addresses the level of risk control - regional, global, etc. |

| 3 | Global impact of COVID-19 on food safety and environmental sustainability: Pathways to face the pandemic crisis | 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e35154 | Impact of COVID-19 on agriculture and food security. |

| 4 | Preclinical and Clinical Investigations of Potential Drugs and Vaccines for COVID-19 Therapy: A Comprehensive Review With Recent Update | 10.1177/2632010X241263054 | Mention of current drugs to combat the virus, no mention of the contribution of technology. |

| 5 | Mental health care measures and innovations to cope with COVID-19: an integrative review | 10.1590/1413-81232024298.06532023 | Main article in Portuguese, only the abstract in English |

| 6 | 13. Innovative Applications of Telemedicine and Other Digital Health Solutions in Pain Management: A Literature Review | 10.1007/s40122-024-00620-7 | It refers to pain management in general and not to the contribution of telemedicine during the pandemic. |

| 7 | The Ambivalence of Post COVID-19 Vaccination Responses in Humans | 10.3390/biom14101320 | It only mentions the types of vaccines, not the technologies used or any innovations. |

| 8 | Effectiveness of telehealth versus in-person care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review | 10.1038/s41746-024-01152-2 | There are no references to the use of telemedicine or innovative applications of telemedicine. |

| 9 | Pivoting school health and nutrition programmes during COVID-19 in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review | 10.7189/jogh.14.05006 | It relates to school feeding programmes and how they have been affected by school closures. |

| 10 | Innovations produced in Primary Health Care during the COVID-19 pandemic: an integrative literature review | 10.1590/1413-81232024296.07022023 | Main article in Portuguese. |

| 11 | Application of telemedicine technology for cardiovascular diseases management during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review | 10.3389/fcvm.2024.1397566 | Relates only to the treatment of cardiovascular disease |

| 12 | Acceptability and Satisfaction of Patients and Providers With Telemedicine During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review | 10.7759/cureus.56308 | Only analyses the results of a questionnaire, nowhere mentions innovative uses of telemedicine |

| 13 | Thoughts on and Proposal for the Education, Training, and Recruitment of Infectious Disease Specialists | 10.18926/AMO/67195 | It refers only to the training of qualified doctors. |

| 14 | A global scoping review of adaptations in nurturing care interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic | 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1365763 | It addresses issues of nutrition and its management during the pandemic. |

| 15 | A narrative review of telemedicine and its adoption across specialties | 10.21037/mhealth-23-28 | General reference to advantages and disadvantages of telemedicine, no explicit reference to pandemic. |

| 16 | Role of new vaccinators/pharmacists in life-course vaccination | 10.1080/07853890.2024.2411603 | General reference to the campaign against adult vaccination, no reference to the use of innovative artificial or technological devices. |

| 17 | The laboratory parameters in predicting the severity and death of COVID-19 patients: Future pandemic readiness strategies | 10.17305/bb.2023.9540 | Investigated the relationship between baseline clinical characteristics, initial laboratory parameters at hospital admission and disease severity and mortality in patients with COVID-19. |

| 18 | Consequences of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Among Healthcare Providers During the First 10 Months of Vaccine Availability: Scoping Review | 10.1177/08445621241251711 | It mentions the consequences of vaccine hesitancy among nurses, but not innovative solutions. |

| 19 | Strengthening resilience and patient safety in healthcare institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic: Experience from a quasi-medical center | 10.1016/j.jfma.2024.09.035 | It refers to questionnaires on health system resilience distributed to staff during COVID19 and interviews with health facility managers. |

| 20 | Navigating the Challenges and Resilience in the Aftermath of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Adolescents with Chronic Diseases: A Scoping Review | 10.3390/children11091047 | This study aims to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the daily lives of adolescents with chronic diseases. |

| 21 | COVID-19 Infection Percentage Estimation from Computed Tomography Scans: Results and Insights from the International Per-COVID-19 Challenge | 10.3390/s24051557 | It mentions the use of new technologies in MRI to diagnose COVID19 , but after the crisis, so it is not included in the technologies that helped exit the crisis. |

| 22 | Interdisciplinary managerial interventions for healthcare workers' mental health - a review with COVID-19 emphasis | 10.13075/mp.5893.01448 | The aim of the review is to summarise the types of management interventions available to protect the mental health of healthcare workers, including an assessment of their prevalence, determinants of effectiveness and limitations from the perspective of healthcare managers. |

| 23 | Telepharmacy Implementation to Support Pharmaceutical Care Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review | 10.4212/cjhp.3430 | Magazine subscription required. |

| 24 | Exploring the Interplay of Food Security, Safety, and Psychological Wellness in the COVID-19 Era: Managing Strategies for Resilience and Adaptation | 10.3390/foods13111610 | This study examines the impact of the pandemic on mental health, food consumption habits and food safety protocols. Through a comprehensive analysis, it aims to clarify the nuanced relationship between food, food safety and mental wellbeing in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting synergistic effects and dynamics that underpin holistic human wellbeing. |

| 25 | Impact of infection prevention and control practices, including personal protective equipment, on the prevalence of hospital-acquired infections in acute care hospitals during COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis | 10.1016/j.jhin.2024.02.010 | Review the effectiveness of the use of personal security measures, there is no innovation or use of technology. |

| 26 | Engaging communities as partners in health crisis response: a realist-informed scoping review for research and policy | 10.1186/s12961-024-01139-1 | There is a general reference to responding to health crises at Community level, but no specific reference to COVID. |

| 27 | Japan's healthcare delivery system: From its historical evolution to the challenges of a super-aged society | 10.35772/ghm.2023.01121 | It identifies the weaknesses in Japan's health system that emerged in the aftermath of the pandemic and ways to address them. |

| 28 | Conducting a health technology assessment in the West Bank, occupied Palestinian territory: lessons from a feasibility project | 10.1017/S0266462324000084 | Health technology assessment for the Occupied Palestinian Territories and breast cancer patients. |

| 29 | Prepared for the polycrisis? The need for complexity science and systems thinking to address global and national evidence gaps | 10.1136/bmjgh-2023-014887 | In this article, we argue that multi-criteria requires greater use of complexity in science and systems thinking. The interdependence of global threats needs to be viewed through the lens of systemic risk: risk embedded in broader contexts of systemic processes, global in nature, highly interconnected with complex, non-linear, causal structures. |

| 30 | Approaches to Design an Efficient, Predictable Global Post-approval Change Management System that Facilitates Continual Improvement and Drug Product Availability | 10.1007/s43441-024-00614-9 | They recommend a set of 8 approaches to enable a holistic transformation of the global PAC management system. This article presents their view of the problem of global regulatory complexity for PAC management, its impact on continuous improvement and risk to the supply of medicines, and approaches that can help mitigate the problem.PAC = Changes made to medicines and vaccines by companies after they have been launched and approved. |

| 31 | Effectiveness of digital health interventions against COVID-19 misinformation: a systematic realist review of intervention trials | https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.07.24311635 | Published in 2023 |

| 32 | Understanding the features and effectiveness of randomized controlled trials in reducing COVID-19 misinformation: a systematic review Get access Arrow | https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyae036 | No free access |

| 33 | Tackling medicine shortages during and after the COVID-19 pandemic: Compilation of governmental policy measures and developments in 38 countries | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2024.105030 | No free access |

| 34 | Have we found a solution for health misinformation? A ten-year systematic review of health misinformation literature 2013–2022 | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2024.105478 | It relates to a more general context than the pandemic, and offers more general solutions. |

| 35 | Examining the influence of information-related factors on vaccination intentions via confidence: Insights from adult samples in Italy and Serbia during the COVID-19 pandemic | https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12929 | Published in 2023 |

| 36 | COVID-19 and Health Information-Seeking Behavior: A Scoping Review | 10.30491/ijmr.2024.479731.1295 | Mentions how users search for information, no reference to technology and innovation. |

| 37 | Automatic detection of health misinformation: a systematic revie | https://doi.org/10.1007/s12652-023-04619-4 | In general, in terms of misinformation, it is not clear what techniques were used during the pandemic. |

| 38 | The power of artificial intelligence for managing pandemics: A primer for public health professionals | https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.3864 | Reference to AI applications in future pandemics, no specific reference to COVID. |

| 39 | Beyond COVID: towards a transdisciplinary synthesis for understanding responses and developing pandemic preparedness in Alaska | https://doi.org/10.1080/22423982.2024.2404273 | We focus specifically on the research generated during the COVID-19 pandemic in Alaska in order to: (1) identify potential areas for further health and pandemic-related research from a social science perspective; (2) outline areas for theoretical and conceptual synergy in future research to generate new research questions; and (3) offer concluding remarks on future research and preparedness applications for future infectious disease outbreaks. |

| 40 | Confronting misinformation related to health and the environment: a systematic review | https://doi.org/10.22323/2.23010901 | General health misinformation not during the pandemic |

| 41 | Evaluating Sources Influencing Vaccine Hesitancy: A Systematic Review. | https://cjni.net/journal/?p=13118 | Examines the factors that influence vaccine hesitancy in general. |

| 42 | Misinformation, disinformation, and fake news: lessons from an interdisciplinary, systematic literature review | https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2024.2323736 | It does not refer to misinformation during the pandemic. |

| 43 | Enlightened change agents with leadership skills’: A scoping review of competency-based curricula in public health PhD education | https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2023.2293475 | The aims of this study were to identify the key drivers for the adoption of competency-based curricula in doctoral education and to articulate the core competencies to be developed as part of the curriculum for doctoral education in public health. |

| 44 | Current landscape of long COVID clinical trials | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2024.111930 | No free access |

| 45 | Issues and Challenges of Artificial Intelligence Implementation in Healthcare: A Review Study | 10.4018/979-8-3693-5976-1.ch004 | Chapter in a book |

| 46 | Detecting Urdu COVID-19 misinformation using transfer learning | https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-024-01300-2 | Our contribution to the field is twofold: first, we have collected a large and diverse dataset of Urdu tweets. Second, we have introduced a novel approach that incorporates feature extraction and ensemble learning techniques, complemented by high-performance filtering and voting classifiers explicitly designed for the COVID-19 Urdu dataset. |

| 47 | How new pharmacists handled COVID-19 misinformation: A qualitative study | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japh.2024.102226 | No free access |

| 48 | Leveraging the ability of the online health information seekers to find credible online sources | http://dx.doi.org/10.21608/EJCM.2024.249600.1276 | Published in 2023 |

| 49 | COVID-19 in Polish-language social media - misinformation vs government information: COVID-19 misinformation in polish social media | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlpt.2024.100871 | Does not mention ways of coping with technology or innovation |

| 50 | ACOVMD: Automatic COVID-19 misinformation detection in Twitter using self-trained semi-supervised hybrid deep learning model | https://doi.org/10.1111/issj.12475 | No free access |

| 51 | The Social Contract at Risk: COVID-19 Misinformation in South Africa | https://doi.org/10.4102/jamba.v16i1.1630 | Exploration of the complex social implications of misinformation. |

| 52 | Information Disorder Amidst Crisis: A Case Study of COVID-19 in India | https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSS.2024.3450788 | No free access |

| 53 | The Relationship Between News Coverage of COVID-19 Misinformation and Online Search Behavior | https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2024.2395155 | No free access |

| 54 | Unmasking an infodemic: what characteristics are fuelling misinformation on social media? | https://dx.doi.org/10.1504/IJAMC.2024.140646 | No free access |

| 55 | Are you vaccinated? Yeah, I’m immunized': a risk orders theory analysis of celebrity COVID-19 misinformation | https://doi.org/10.1080/17538068.2024.2320984 | No free access |

| 56 | Enhancing COVID-19 misinformation detection through novel attention mechanisms in NLP | https://doi.org/10.1111/exsy.13571 | No free access |

| 57 | Endorsement of COVID-19 misinformation among criminal legal involved individuals in the United States: Prevalence and relationship with information sources | 0.1371/journal.pone.0296752. | This study examined the prevalence of COVID-19-related misinformation and its relationship to the sources of COVID-19 information used among Americans with criminal justice involvement (CLI). |

| 58 | Telemedicine and Pediatric Care in Rural and Remote Areas of Middle-and-Low-Income Countries: Narrative Review | 10.1007/s44197-024-00214-8 | It does not focus on the COVID era and its contribution to overcoming the crisis, but only on paediatrics. |

| Reference | Collaboration |

|---|---|

| [86] | Germany's participation in the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A) collaboration, which aims to ensure the rapid development and equitable distribution of vaccines and experimental treatments. |

| In Germany, to speed up the exit from the crisis, cooperation between different ministries has been encouraged. | |

| [83] | In Israel, cooperation was seen as necessary between many different bodies, from the Ministry of Health, the government, citizens, academics, the military and even private organisations. |

| [61] | In Belgium, crisis management at this level was considered to require cooperation between various bodies such as the Public Health Institute (Sciensano), the government and various groups set up on an emergency basis to help manage the crisis. |

| Collaboration was required to enable the widespread use of diagnostic tests, and at this level the National Reference Centre, pharmaceutical companies, academics, government and the Federal Agency for Medicines and Health Products (FAMHP) worked together. | |

| [71] | The “Stop The Spread” campaign, aimed at reducing misinformation, is an example of collaboration between WHO and the UK government. |

| [10,14] | A shining example of unprecedented global collaboration is the rapid development and distribution of vaccines. |

| [81] | Collaboration between local industries and construction companies to produce as many goods as possible, mainly medical equipment, needed during the pandemic. |

| [14] | The way out of the crisis was largely based on vaccines, so their equitable distribution was a prerequisite, leading to the creation of CONVEX, whose members include the World Health Organization, the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), Gavi's Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), the Vaccine Alliance, and the Gavi Foundation. |

| [7] | In Brazil, a platform to help students and teachers cope with feelings of fear and anxiety was created by two university institutions. |

| [83] | Cooperation took place on a multidisciplinary level, with the Israeli Ministry of Health maintaining the lead role in crisis management. |

| Reference | Country | |

|---|---|---|

| [87] | Malaysia | The Ministry of Health, in order to contribute to the ability of experts to analyse data in order to draw safe conclusions on the appropriate ways to deal with the crisis, published detailed data that could be analysed at a second level. |

| Argentina | Daily data publication. | |

| Nigeria | ||

| Chile | The collection and publication of data related to the rates of disease, the rates of those vaccinated, and the rates of deaths between vaccinated and unvaccinated people, contributed to strengthening the vaccination campaign. | |

| [80] | African Union(Ghana, Nigeria, Ethiopia, South Africa) | To provide valid information, adverse reactions to vaccines were recorded and reported on a weekly basis. |

| [88] | United Kingdom | Programme (International COVID-19 Data Alliance - ICODA). The aim of the programme was to make research data on health and the virus available to the global scientific and research community so that it could be used to improve health in low- and middle-income countries. In this context, the value of collaboration in addressing the crisis was highlighted as 135 researchers from 19 different countries worked together to analyse the data at a second level and find solutions to the problems that had arisen. |

| [66] | United Kingdom | The collaboration has led to the creation of the Open Access Scholarly Publishing Association, an agreement between publishers of scientific journals to prioritise the immediate publication of articles containing data on the virus so that the information can be disseminated to the wider scientific community. |

| [79] | Kingdom of Saudi Arabia | Information management in the context of the pandemic and future challenges of the same nature were the focus of the World Digital Health Summit in Riyadh. The summit focused on information management, dissemination of scientific data and support for digital health. |

| [79] | U.S.A | IMPACT was created by health professionals in Illinois to promote interdisciplinary communication, debunk misinformation, and limit the impact of misinformation on social media. |

| [66] | Social media users with large followings agreed to use their accounts to help publish valid information, using their communication skills and visibility to help limit misinformation. |

| Reference | Country | Role |

|---|---|---|

| [86] | Germany | Recognising the need for leadership in critical global circumstances, the country took a leading role in managing the crisis at the global level. |

| [61] | Belgium | The National Reference Centre (NRC) played a leading role in managing diagnostic testing in the country. |

| [17] | USA | The extraordinary circumstances created by the pandemic required individuals with leadership skills to go to the front lines, make decisions, but also report back to superiors so that the US Military Health System (MHS) could respond. |

| Reference | Country | Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| [70] | USASouth Korea | Online courses for seniors on using search engines and choosing reliable sources. |

| [11] | USA | Students have had access to free online asynchronous courses and syllabuses on source evaluation. |

| [7] | Brazil | Teaching older people to use social media in the state of Paraná. |

| Audiovisual and written materials have been made available on how to use social media and smart phones for older people. | ||

| [90] | AR technology was used to create games that presented information about the disease in an entertaining way, with the ultimate goal of informing older people about ways to combat the pandemic. | |

| [70] | Educational game that allows the user to create hypothetical posts, giving them the opportunity to understand how easy it is to spread false information. |

| Reference | |

|---|---|

| [6,14] | New drugs, new vaccines, the use of new technologies and innovative products have contributed to the treatment of infectious diseases. |

| [6] | Innovative vaccine solutions are still being sought. One possibility is a nasal vaccine that would prevent the virus from entering the body. |

| [83] | Israel has been a pioneer in mass vaccination. This has been achieved mainly through pioneering tactics in disseminating information to the general public. |

| [88] | While the ICODA DP-PRIEST team has developed an innovative tool to help doctors in low- and middle-income countries decide whether a patient should be admitted to an intensive care unit |

| Also innovative was the action of the DP-IDS-COVID19 group, which launched an index in Brazil to identify social inequalities and vulnerable groups, and to implement interventions based on this data. |

| Refere- nce |

|

|---|---|

| [83] | In Israel, the exit from the crisis was based on interdisciplinary cooperation. |