Submitted:

10 February 2025

Posted:

11 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. Literature Review

1.3. Original Contributions

1.4. Paper Structure

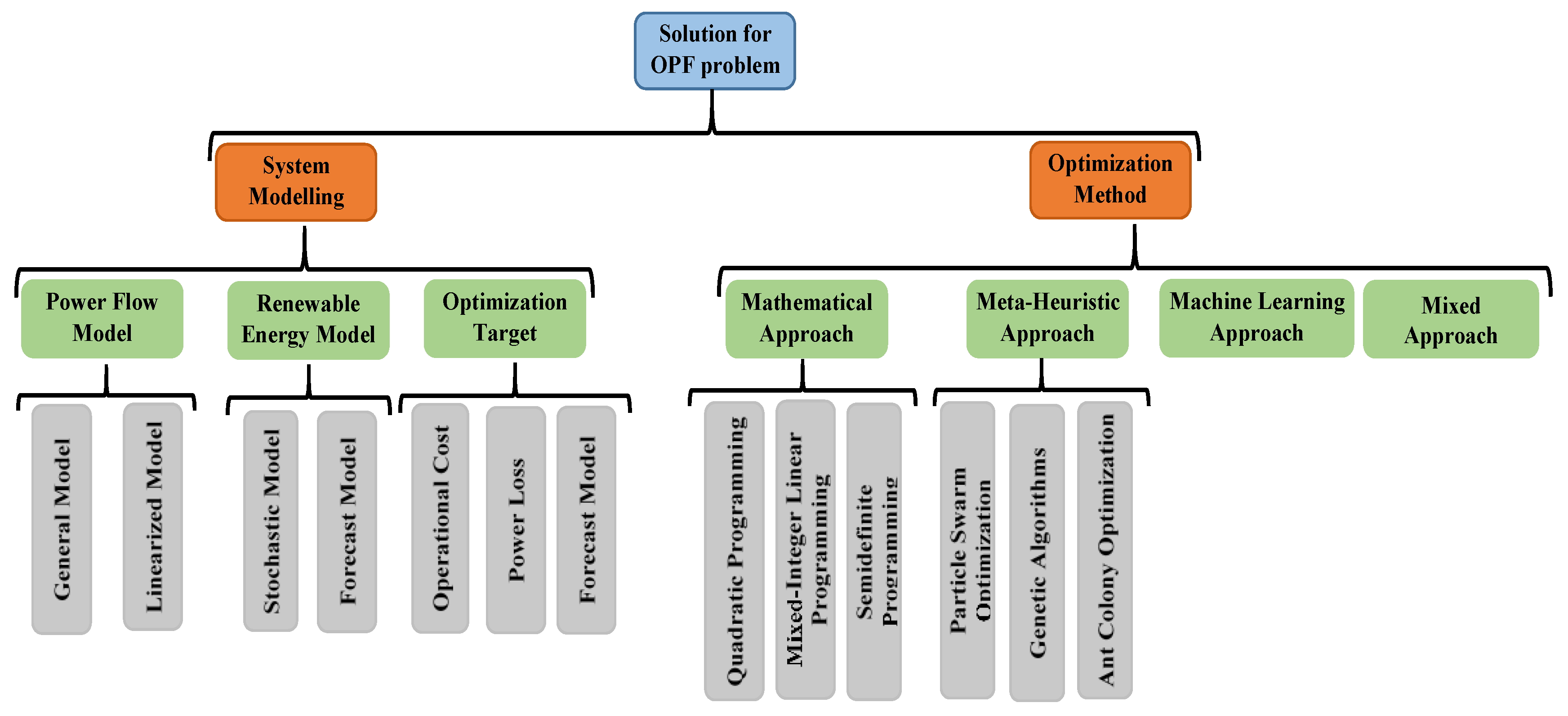

2. OPF Problem in Electric Networks Integrating Wind Energy

2.1. OPF Problem in Electric Networks

2.2. OPF Formulation

2.2.1. Objective Function

2.2.2. Technical Constraints

- Equality restrictions

- Inequality restrictions

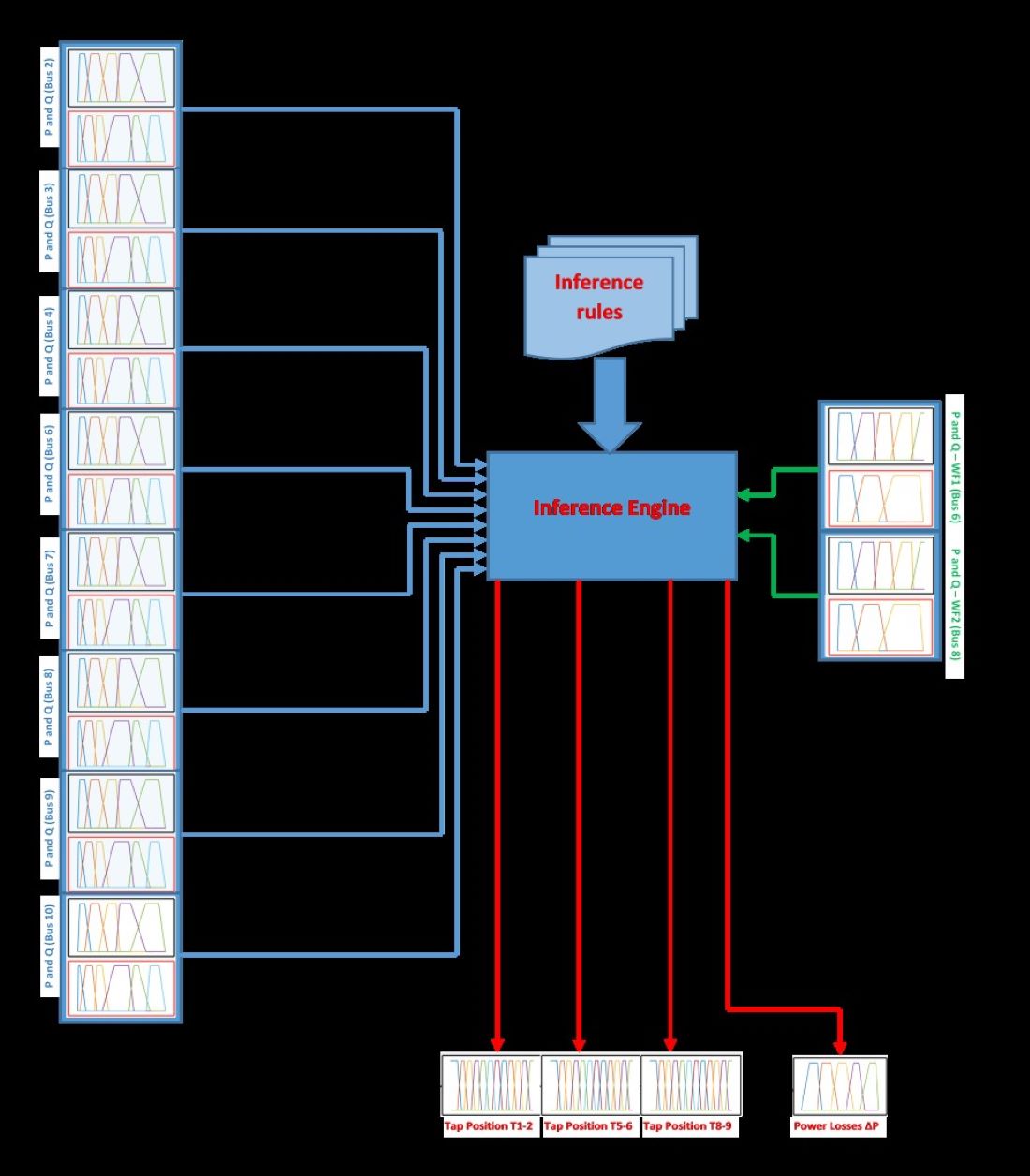

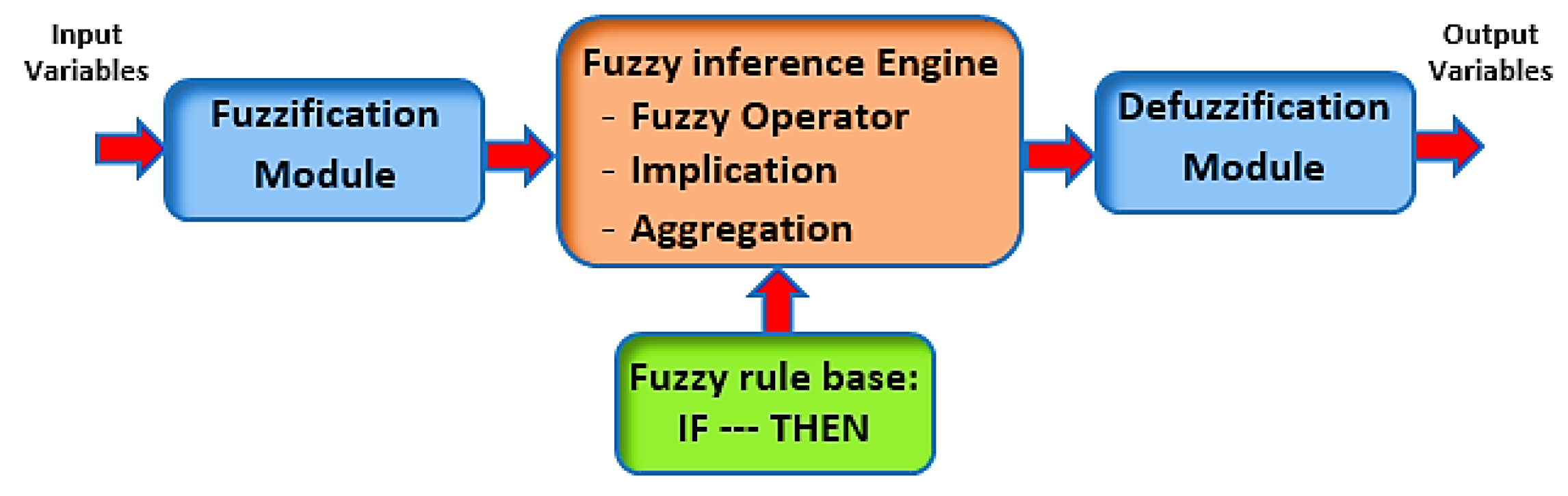

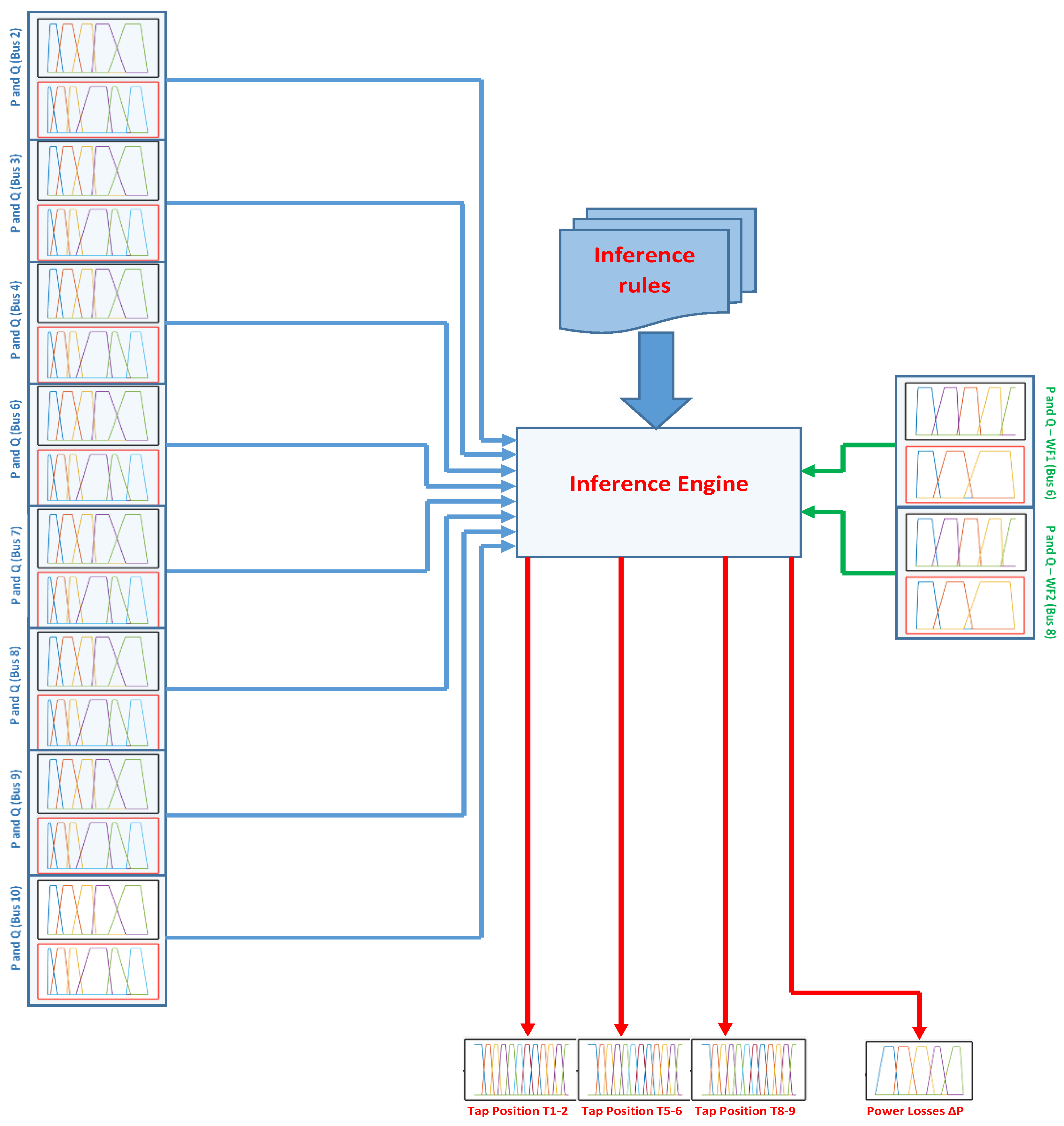

3. Fuzzy Inference System-Based Approach in OPF Analysis

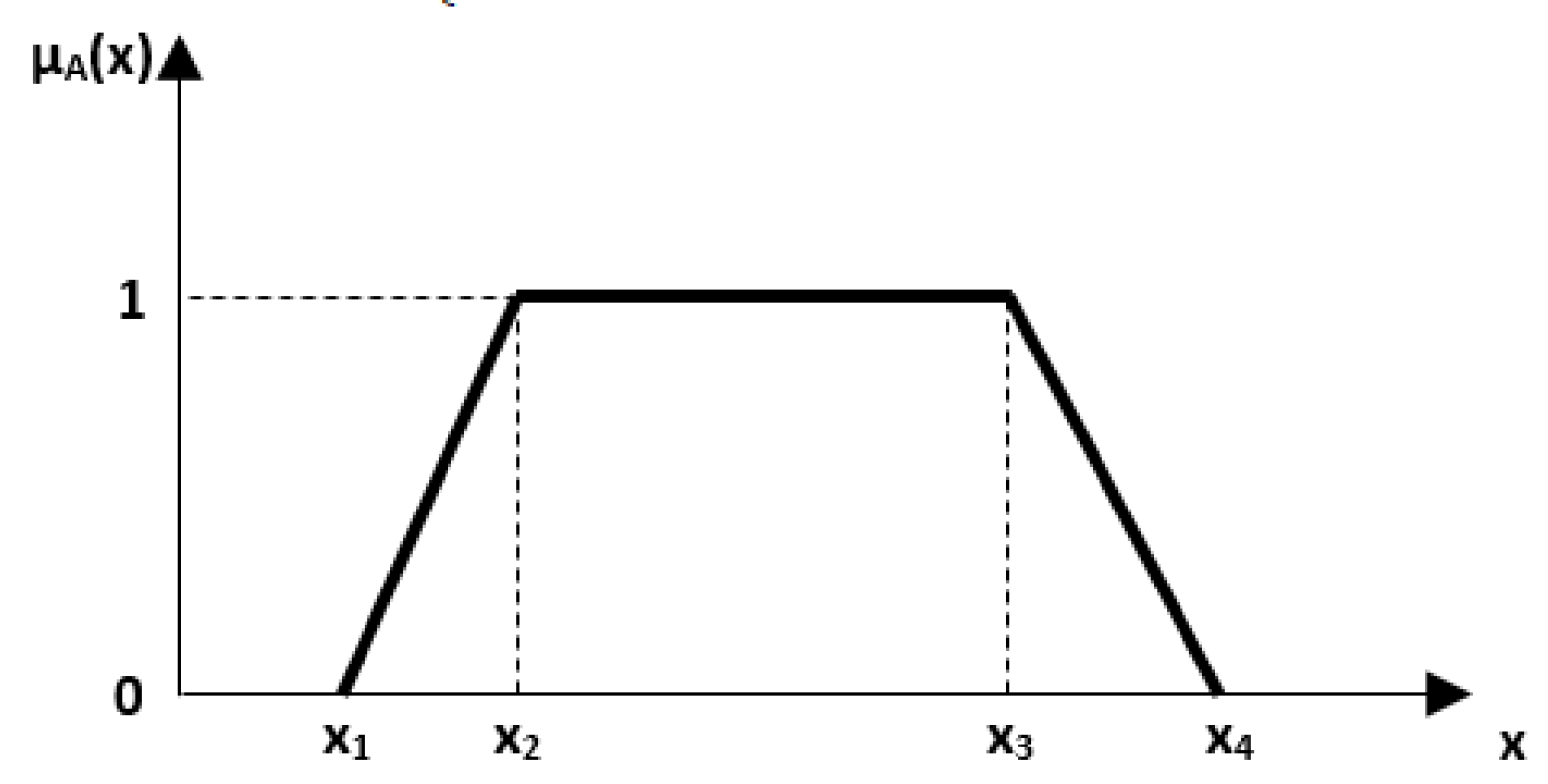

3.1. Fuzzy Sets and Fuzzy Logic

3.2. Fuzzy Inference Systems

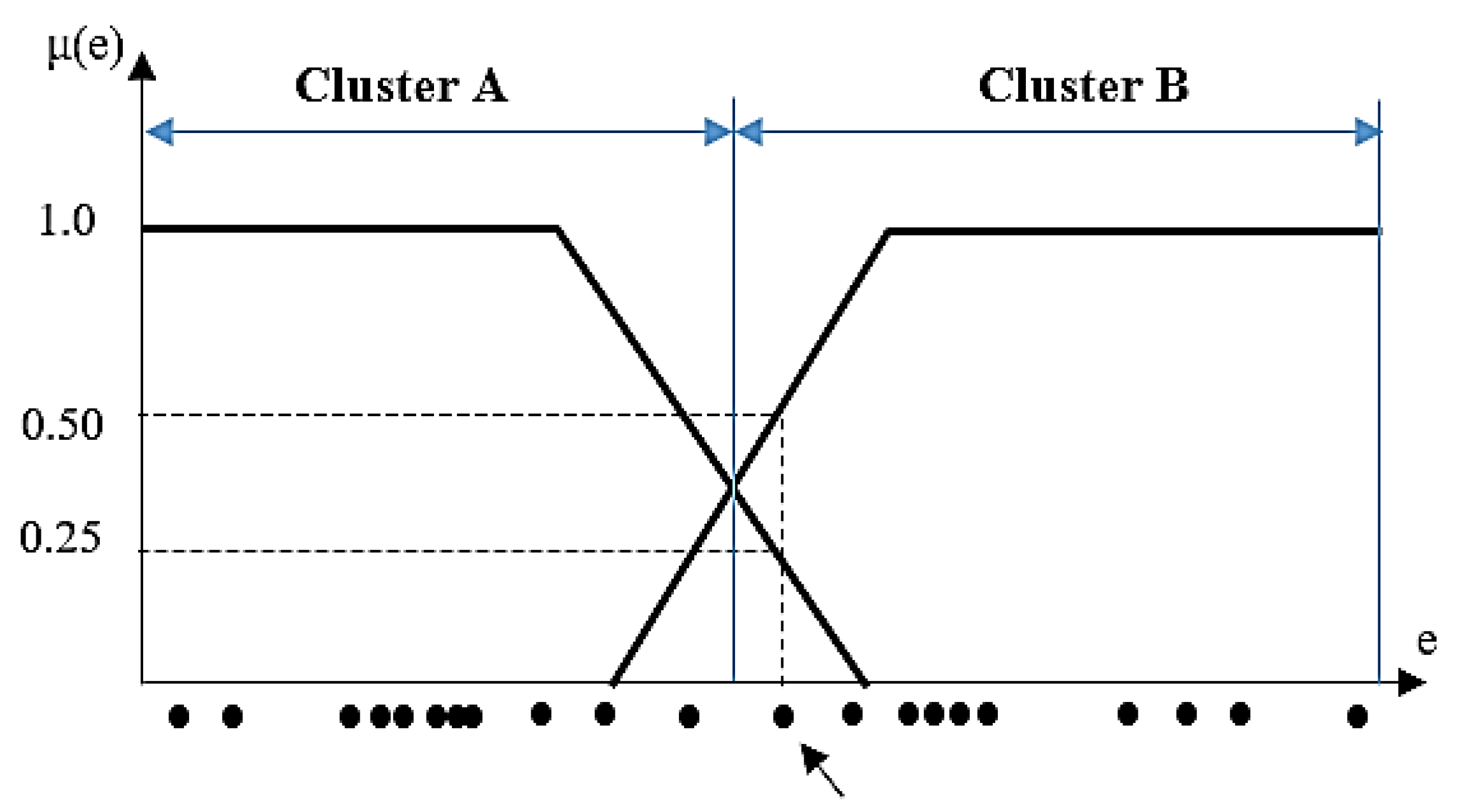

3.2.1. Fuzzification Process

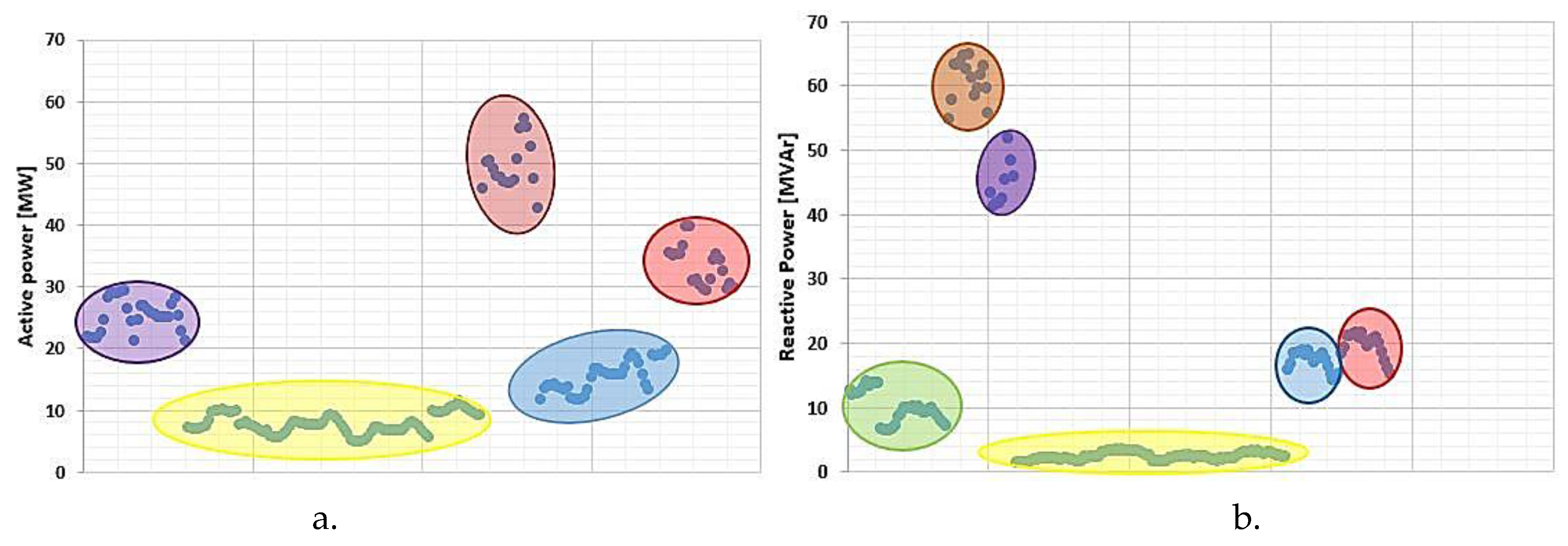

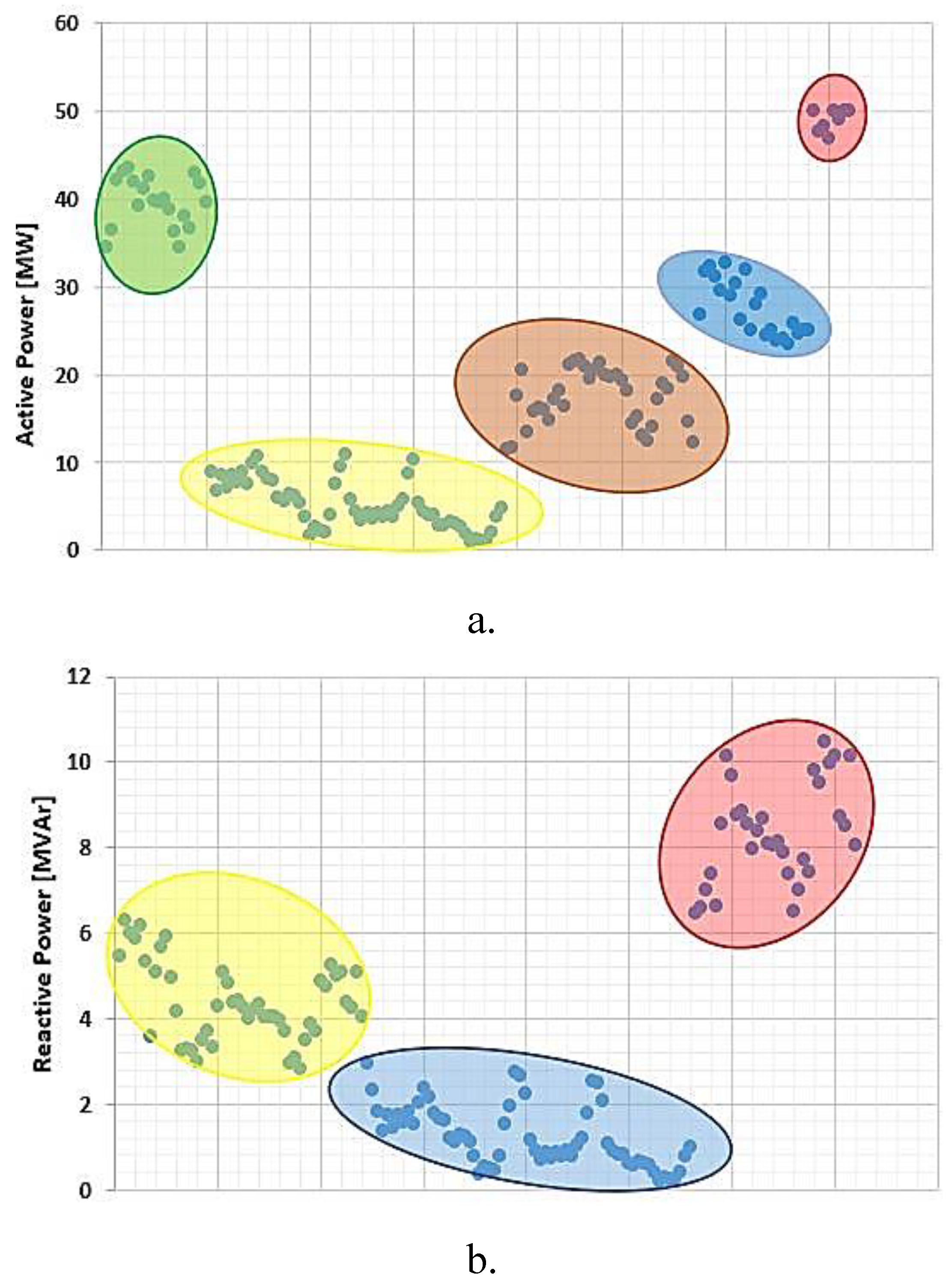

3.2.2. Improving Fuzzification Process with Fuzzy K-Means Clustering Algorithm

- The density of the nearby data points must be calculated to determine the likelihood that each point in a cluster will become a centre.

- Choose the data point with the highest chance of becoming the cluster's first centre.

- Remove all the data points near the cluster's first centre based on the influence range around the cluster's first centre.

- After that, choose the cluster's remaining point with the greatest likelihood of becoming its next centre.

- Repeat the steps 3 and 4 until all of the data within the cluster's influence range is obtained.

3.2.3. Inference Engine

- Calculate the inputs' compatibility with the first component (antecedent) of the inference rule Rn, n = 1, ..., NR.

- Identifying the set of rules RSR closest to the input variables with the highest degree of compatibility. Each of the input data subsets will have a single rule.

- Corresponding to RSR, calculate the membership of input variables in its linguistic categories and choose the higher one as the degree of firing of the rule.

- Fire the rules in RSR and apply the defuzzification process considering the linguistic output value of each rule and its corresponding degree of firing.

3.2.4. Defuzzification Process

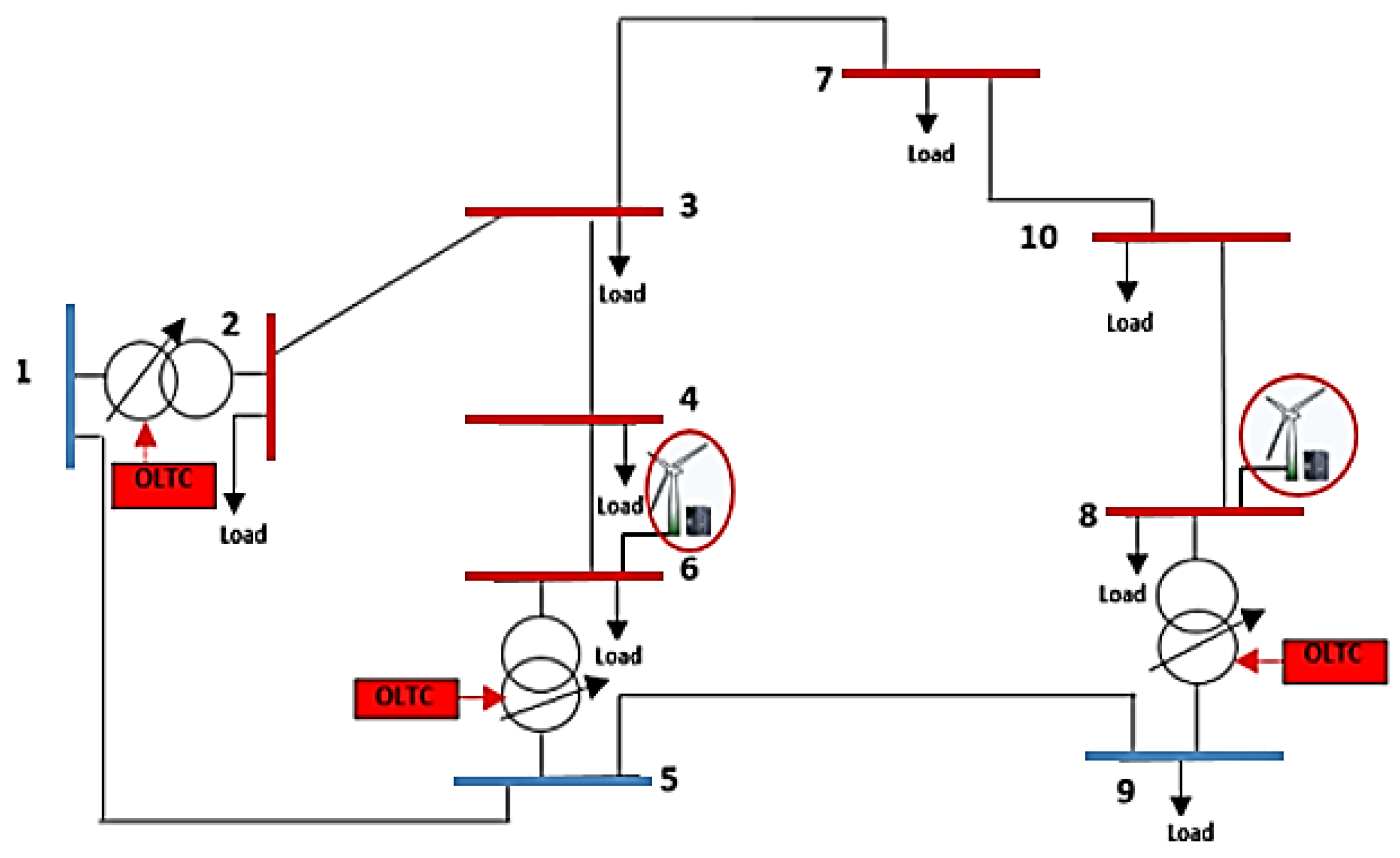

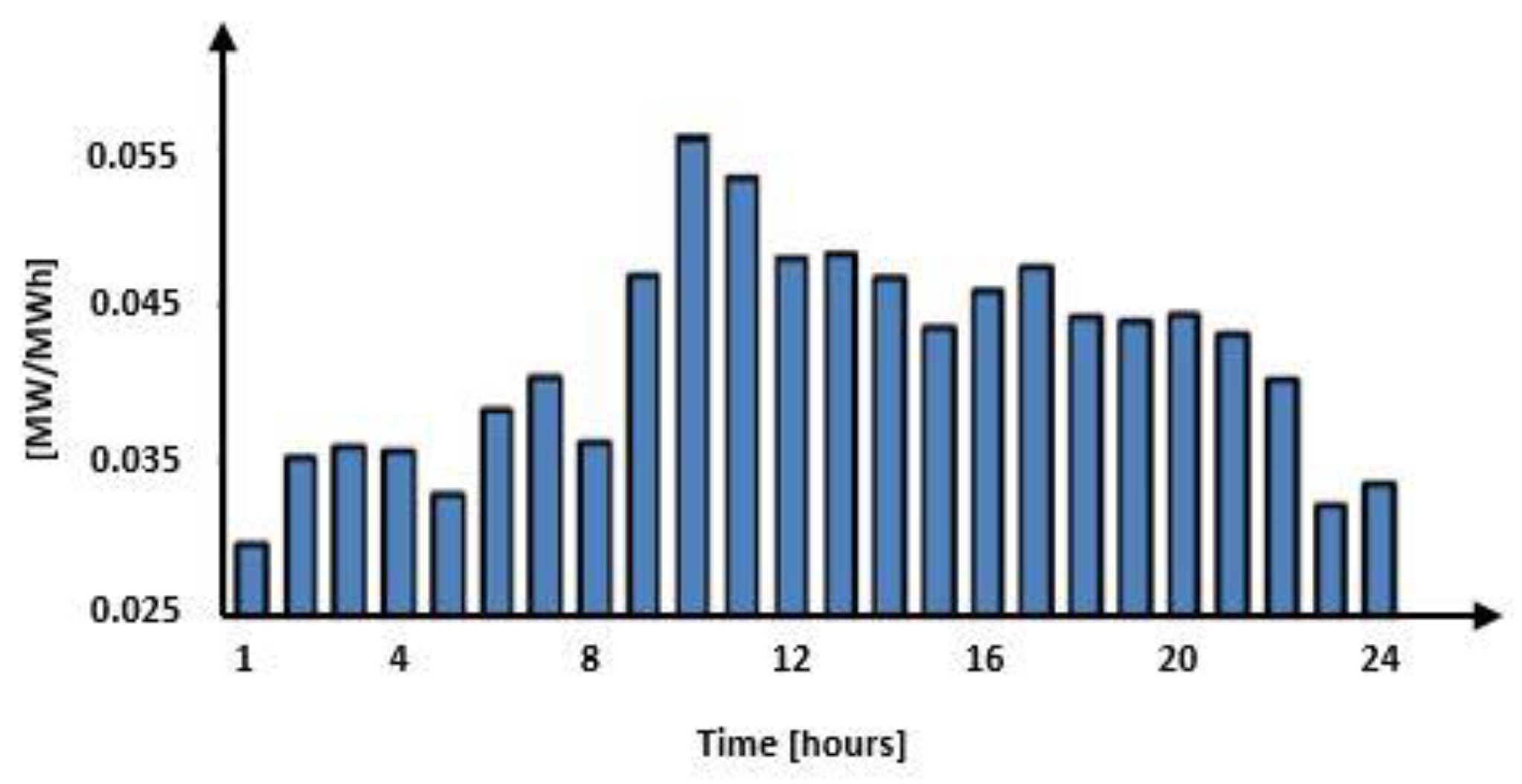

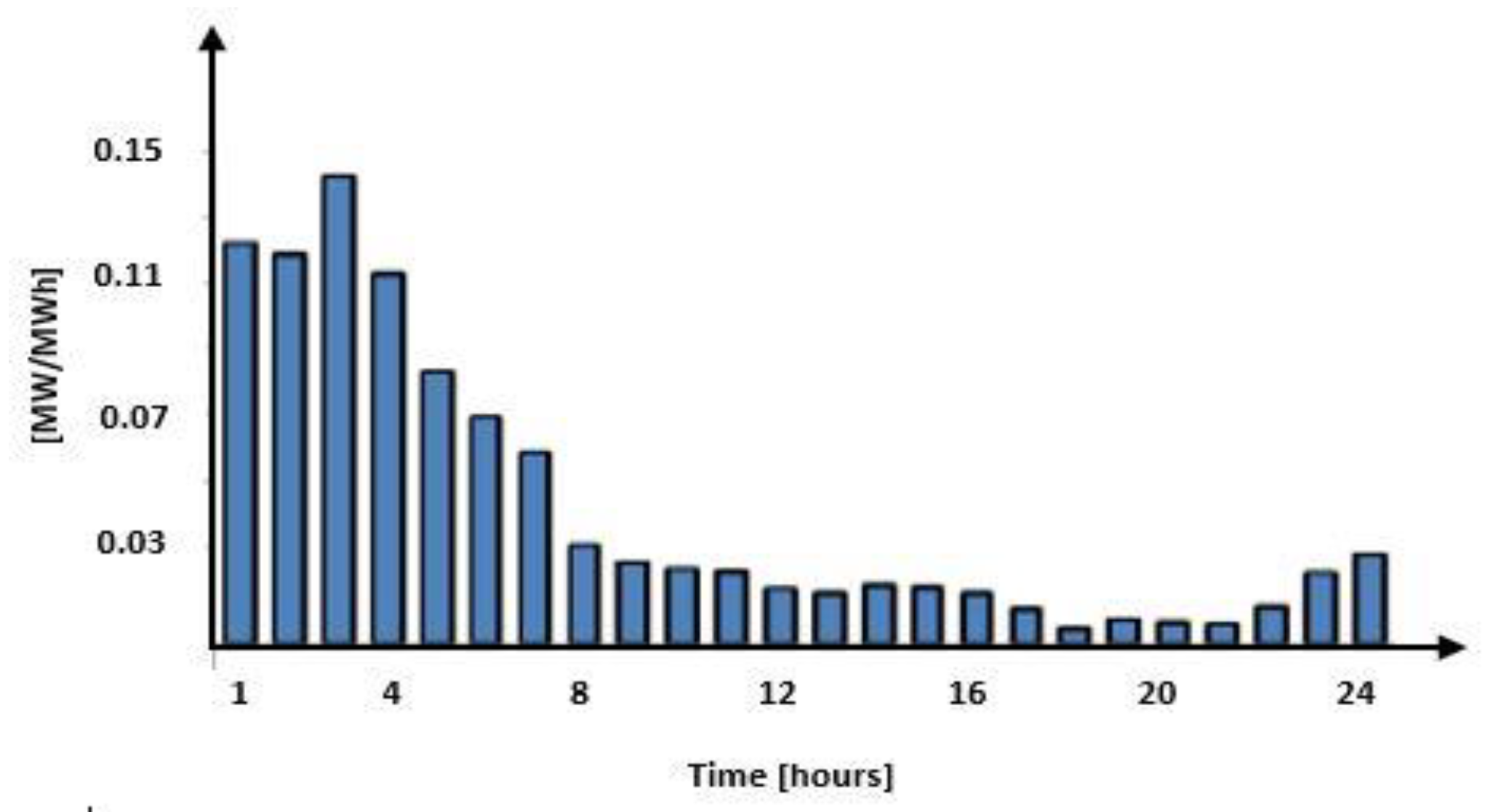

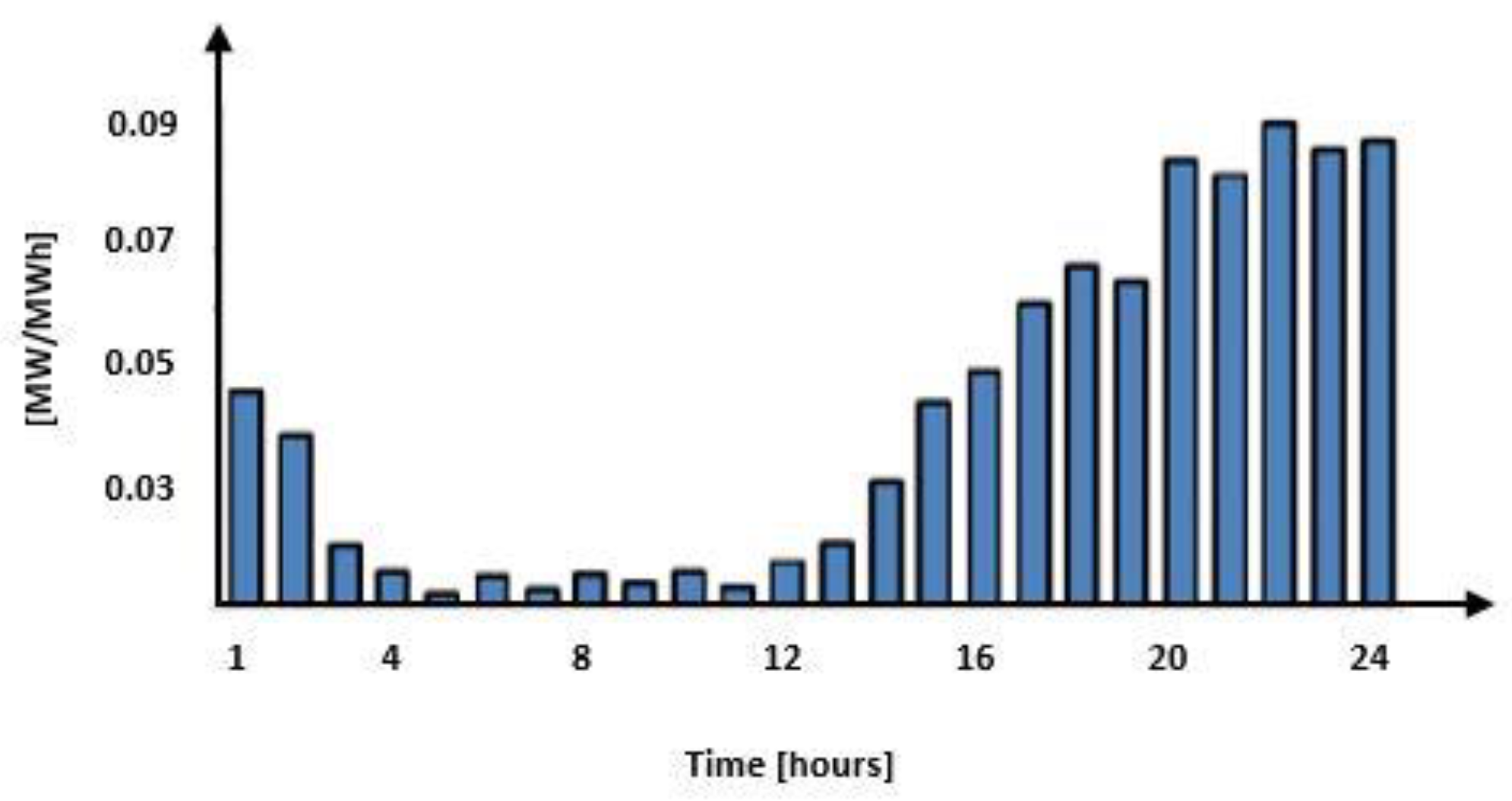

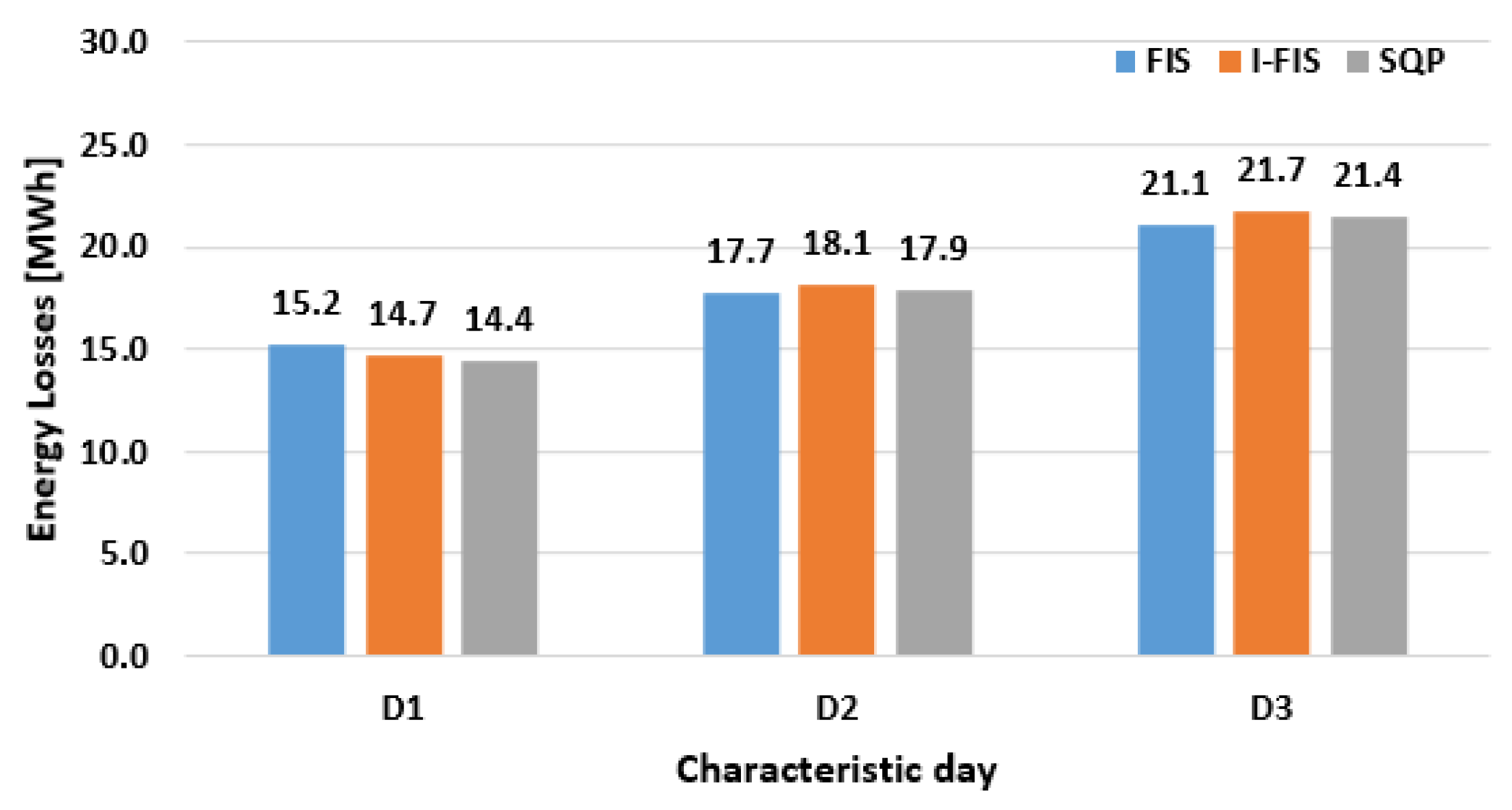

4. Case Study

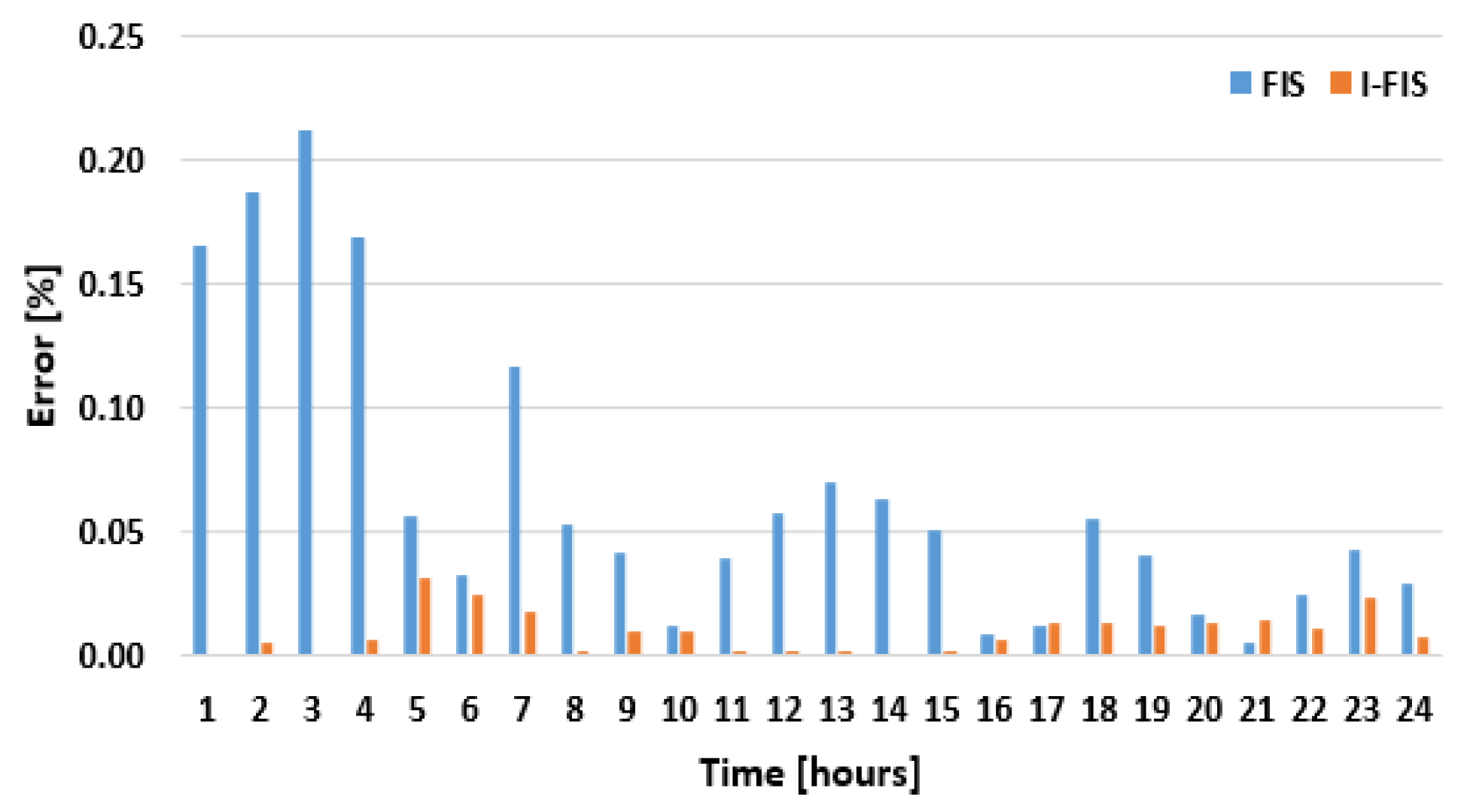

5. Discussions and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OPF | Optimal Power Flow |

| FIS | Fuzzy Inference System |

| I-FIS | Improved Fuzzy Inference System |

| ENO | Electric Network Operator |

| SQP | Sequential Quadratic Programming |

| STATCOM | Static Synchronous Compensator |

| CPP | Classical Power Plant |

| WF | Wind Farm |

| OLTC | On-Load Tap Changer |

| PE | Percentage Errors |

| APE | Average Percentage Errors |

| SCADA | Supervisory, Control, and Data Acquisition |

| RES | Renewable Energy Sources |

References

- Risi, B.-G.; Riganti-Fulginei, F.; Laudani, A. Modern Techniques for the Optimal Power Flow Problem: State of the Art. Energies 2022, 15, 6387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momoh, J.A.; Adapa, R.; El-Hawary, M.E. A Review of Selected Optimal Power Flow Literature to 1993. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, 1999, 14, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentier, J. Contribution á l’Étude du Dispatching Économique. Bulletin de la Société Française des Électriciens 1962, 3, 431–447. [Google Scholar]

- Khalghani, M. R.; Ramezani, M.; Mashhadi, M. R. Probabilistic Power Flow Based on Monte-Carlo Simulation and Data Clustering to Analyze Large-Scale Power System in Including Wind Farm. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Kansas Power and Energy Conference (KPEC), Manhattan, KS, USA; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, C.; Xu, Z.; Dong, Z. Y.; Wong, K. P. Probabilistic Load Flow Computation Using First-Order Second-Moment Method. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting, San Diego, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Xia, D.; Gao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, G.; Lu, W.; Wu, X.; Li, Y. Probabilistic Load Flow Calculation of AC/DC Hybrid System Based on Cumulant Method. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 2022, 139, 107998. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego, L.; Franco, J.; Cordero, L. A Fast-Specialized Point Estimate Method for the Probabilistic Optimal Power Flow in Distribution Systems with Renewable Distributed Generation. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 2021, 131, 107049. [Google Scholar]

- Varathan, G.; Belwin, E. J. A Review of Uncertainty Management Approaches for Active Distribution System Planning. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2024, 205, 114808. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, V.; Saraiva, J. T. Fuzzy Modelling of Power System Optimal Load Flow. In Proceedings of the Power Industry Computer Application Conference, Baltimore, MD, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, B. A.; Saraiva, J. T.; Neves, L. Modelling Costs and Load Uncertainties in Optimal Power Flow Studies In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on the European Electricity Market, Lisboa, Portugal, 2008.

- Sarcheshmah, M.S; Seif, A.R. A New Fuzzy Power Flow Analysis Based on Uncertain Inputs. International Review of Electrical Engineering, 2009, 4, 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Salhi, A.; Naimi, D.; Tarek, B. Fuzzy Multi-Objective Optimal Power Flow Using Genetic Algorithms Applied to Algerian Electrical Network. Recent Patents on Electrical Engineering, 2013, 11, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Peng, Z.; Wang, Q.; Qi, W.; Ge, Y. Optimal power flow method with consideration of uncertainty sources of renewable energy and demand response. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1421277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Shi, L.; Ni, Y. A Solution of Optimal Power Flow Incorporating Wind Generation and Power Grid Uncertainties. IEEE Access, 2018, 6, 19681–19690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M. H.; Kamel, S.; Hussien, A. G. Optimal Power Flow Analysis Considering Renewable Energy Resources Uncertainty Based on an Improved Wild Horse Optimizer. IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution, 2023, 17, 3582–3606. [Google Scholar]

- Lastomo, D.; Setiadi, H. Optimal Power Flow Using Fuzzy-Firefly Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Computer Science and Informatics (EECSI), Malang, Indonesia; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh, M. I.; Usman, M.; Capitanescu, F. Toward Stochastic Multi-Period AC Security Constrained Optimal Power Flow to Procure Flexibility For Managing Congestion and Voltages. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Smart Energy Systems and Technologies (SEST), Vaasa, Finland; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ilyas, M. A.; Abbas, G.; Alquthami, T.; Awais, M.; Rasheed, M. B. Multi-Objective Optimal Power Flow with Integration of Renewable Energy Sources Using Fuzzy Membership Function. IEEE Access, 2020, 8, 143185–143200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Li, X.; Gao, W.; Lu, P.; Wang, T. Random-Fuzzy Chance-Constrained Programming Optimal Power Flow of Wind Integrated Power Considering Voltage Stability. IEEE Access, 2020, 8, 217957–217966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muangkhiew, P.; Chayakulkheeree, K. Multi-objective Optimal Power Flow Using Fuzzy Satisfactory Stochastic Optimization. International Energy Journal, 2022, 22, 281–290. [Google Scholar]

- Pandiarajan, K.; Babulal, C. K. Fuzzy Harmony Search Algorithm Based Optimal Power Flow for Power System Security Enhancement. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 2016, 78, 72–79. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Q.; Gao, W.; Ma, R. Multi-Objective Random-Fuzzy Optimal Power Flow of Transmission-Distribution Interaction Considering Security Region Constraints. Electric Power Systems Research, 2023, 224, 109715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Chaturvedi, D. K. Optimal Power Flow Solution Using Fuzzy Evolutionary and Swarm Optimization. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 2013, 47, 416–423. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, R. H.; Tsai, S. R.; Chen, Y. T.; Tseng, W. T. Optimal Power Flow By a Fuzzy Based Hybrid Particle Swarm Optimization Approach. Electric Power Systems Research, 2011, 81, 1466–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, U.; Nangia, U.; Jain, N. K.; Gupta, S. Optimal Power Flow Solution Using a Learning-Based Sine–Cosine Algorithm. The Journal of Supercomputing, 2024, 80, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadipour, M.; Ali, Z.; Ramachandaramurthy, V. K.; Ridha, H. M. A Memory-Guided Jaya Algorithm to Solve Multi-Objective Optimal Power Flow Integrating Renewable Energy Sources. Applied Soft Computing 2024, 111924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Sun, Y.; Zou, Y.; Zheng, F.; Liu, S.; Zhao, B.; Wu, M.; Cui, H. Optimal Power Flow in Distribution Network: A Review on Problem Formulation and Optimization Methods. Energies 2023, 16, 5974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoraș, G.; Neagu, B.-C.; Ivanov, O.; Livadariu, B.; Scarlatache, F. A New SQP Methodology for Coordinated Transformer Tap Control Optimization in Electric Networks Integrating Wind Farms. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M. S.; Chowdhury, M. M. -U. –T; Kamalasadan, S. Sequential Quadratic Programming (SQP) Based Optimal Power Flow Methodologies for Electric Distribution System with High Penetration of DERs. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, 2024, 60, 4810–4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saatchi, R. Fuzzy Logic Concepts, Developments and Implementation. Information, 2024, 15, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Han, J.; Shen, Q.; Angelov, P. . Autonomous Learning for Fuzzy Systems: A Review. Artif Intell Rev 2023, 56, 7549–7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samavat, T.; Nazari, M.; Ghalehnoie, M.; Nasab, M.A.; Zand, M.; Sanjeevikumar, P.; Khan, B. A Comparative Analysis of the Mamdani and Sugeno Fuzzy Inference Systems for MPPT of an Islanded PV System. International Journal of Energy Research 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujaru, K.; Adak, D.; Kar, T.K.; Patra, S.; Jana, S. A Mamdani Fuzzy Inference System with Trapezoidal Membership Functions For Investigating Fishery Production. Decision Analytics Journal, 2024, 11, 100481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.; Mitchell, J.; Razaque, A.; et al. A Fuzzy Inference System (FIS) to Evaluate the Security Readiness of Cloud Service Providers. J Cloud Comp, 2020, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathinathan, T.; Ponnivalavan, K.; Mike Dison, E. Different Types of Fuzzy Numbers and Certain Properties. Journal of Computer and Mathematical Sciences, 2015, 6, 631–651. [Google Scholar]

- Grigoraş, G.; Neagu, B.; Scarlatache, F. Estimation of Energy Losses in Distribution Transformers Using A Fuzzy Approach, In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Fundamentals of Electrical Engineering (ISFEE), Bucharest, Romania, 2016.

- Ferraro, M.B. Fuzzy k-Means: History and Applications. Econometrics and Statistics, 2024, 30, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy Poli, V. S. Fuzzy C-Means and Fuzzy K-Means Algorithms using Fuzzy Functional Dependencies, In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Fuzzy Theory and Its Applications (iFUZZY), Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 2022.

- Choudhary, A.; Badholia, A.; Sharma, A.; et al. A Dynamic K-Means-Based Clustering Algorithm Using Fuzzy Logic for CH Selection and Data Transmission Based On Machine Learning. Soft Comput 2023, 27, 6135–6149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surendra, H.J.; Deka, P.C.; Rajakumara, H.N. Application of Mamdani model-based fuzzy inference system in water consumption estimation using time series. Soft Comput, 2022, 26, 11839–11847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, T. M.; Camargo, H. d. A. Context-Sensitive Clustering in the Design of Fuzzy Models, In Proceedings of the 2008 Eighth International Conference on Hybrid Intelligent Systems, Barcelona, Spain, 2008.

- Cartina, G.; Grigoras, G.; Bobric, E. C.; Comanescu, D. Improved fuzzy load models by clustering techniques in optimal planning of distribution networks. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Bucharest PowerTech, Bucharest, Romania; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mazarei, A.; Sousa, R.; Mendes-Moreira, J.; Molchanov, S.; Ferreira, H.M. Online Boxplot Derived Outlier Detection. Int J Data Sci Anal, 2025, 19, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumalai, C.; Kanimozhi, R.; Vaishnavi, B. Data Analysis Using Box Plot on Electricity Consumption, Proceedings of the 2017 International conference of Electronics, Communication and Aerospace Technology (ICECA), Coimbatore, India, 2017.

| Refs. | Uncertainty data | Defining fuzzy models | Objective Function | OPF Methodology |

Network type |

RES integration |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Second | ||||||

| [4] [13] |

Yes | Done by Decision Maker |

Generat. Cost | - | NR-MCS | Real IEEE30 |

Yes |

| [5] | Yes | Done by Decision Maker |

Runtime | - | FOSM-MCS | IEEE9 IEEE18 | No |

| [6] | Yes | Done by Decision Maker |

- | - | CM | IEEE34 IEEE57 | Yes |

| [7] [14] |

Yes | Done by Decision Maker |

Power losses | - | PEM PSO |

IEEE69 IEEE30 |

Yes |

| [12] | Yes | Done by Decision Maker |

Cost | Voltage index | GA | 59 bus Test | Yes |

| [15] [16] |

Yes No |

- | Total Cost | Power losses | WHOA FFA |

IEEE30 | Yes No |

| [17] | No | - | Cost | - | Stochastic | 5 bus Test Nordic32 |

Yes |

| [18] [19] |

Yes | Done by Decision Maker |

Generation cost | Power losses | PSO NSGA-II |

IEEE30 | Yes |

| [20] | Yes | Done by Decision Maker |

Voltage index | Optimal Tap | FMOPF | IEEE30 | No |

| [21] [24] |

No | Fuel cost | - Power losses |

FHSA | IEEE30 IEEE57 IEEE118 |

No | |

| [22] [23] |

Yes | Done by Decision Maker |

Generation cost | Power losses | MORF FZGAPSO |

IEEE33 IEEE30 |

Yes |

| [25] | Yes | Done by Decision Maker |

Cost savings | Power losses | L-SCA | IEEE57 IEEE18 59 bus test |

Yes |

| [26] | Yes | Done by Decision Maker |

Power losses | Voltage deviation | MG-JA | IEEE30 IEEE57 |

Yes |

|

Proposed approach |

Yes | Fuzzy K-Means clustering | Power losses | Bus Voltage | SQP | Real | Yes |

| No. | Bus i | Bus j | Number of circuits | R [Ω] |

X [Ω] |

B [μS] |

| 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 2.00 | 18.52 | 184.00 |

| 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 10.87 | 24.73 | 157.50 |

| 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 0.87 | 2.16 | 13.50 |

| 4 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 1.11 | 4.45 | 23.00 |

| 5 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 6.08 | 12.28 | 77.00 |

| 6 | 7 | 10 | 1 | 5.62 | 12.23 | 71.00 |

| 7 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 0.43 | 1.08 | 7.00 |

| 8 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 2.05 | 19.43 | 193.22 |

| Variable | Clusters | Average value |

Standard Deviation | Minimum value |

Maximum value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Generated Active Power [MW] |

C1 | 7.84 | 1.60 | 5.00 | 11.40 |

| C2 | 15.37 | 2.43 | 11.70 | 19.60 | |

| C3 | 25.13 | 1.88 | 21.30 | 28.20 | |

| C4 | 33.35 | 3.28 | 29.50 | 39.90 | |

| C5 | 49.52 | 3.88 | 42.80 | 57.20 | |

|

Generated Reactive Power [MVAr] |

C1 | 2.41 | 0.58 | 1.40 | 3.50 |

| C2 | 8.60 | 1.37 | 6.50 | 10.20 | |

| C3 | 14.02 | 1.38 | 12.10 | 16.30 | |

| C4 | 19.20 | 1.48 | 16.90 | 21.60 | |

| C5 | 44.71 | 3.61 | 41.40 | 51.90 | |

| C6 | 61.01 | 3.14 | 54.90 | 64.90 | |

|

Requested Active Power [MW] |

C1 | 5.29 | 2.75 | 0.87 | 10.98 |

| C2 | 17.48 | 3.18 | 11.49 | 21.76 | |

| C3 | 27.52 | 3.15 | 23.41 | 32.69 | |

| C4 | 39.65 | 2.85 | 34.44 | 43.52 | |

| C5 | 48.99 | 1.25 | 46.81 | 50.00 | |

|

Requested Reactive Power [MVAr] |

C1 | 1.21 | 0.68 | 0.18 | 2.72 |

| C2 | 4.35 | 0.93 | 2.84 | 6.32 | |

| C3 | 8.35 | 1.18 | 6.46 | 10.49 | |

|

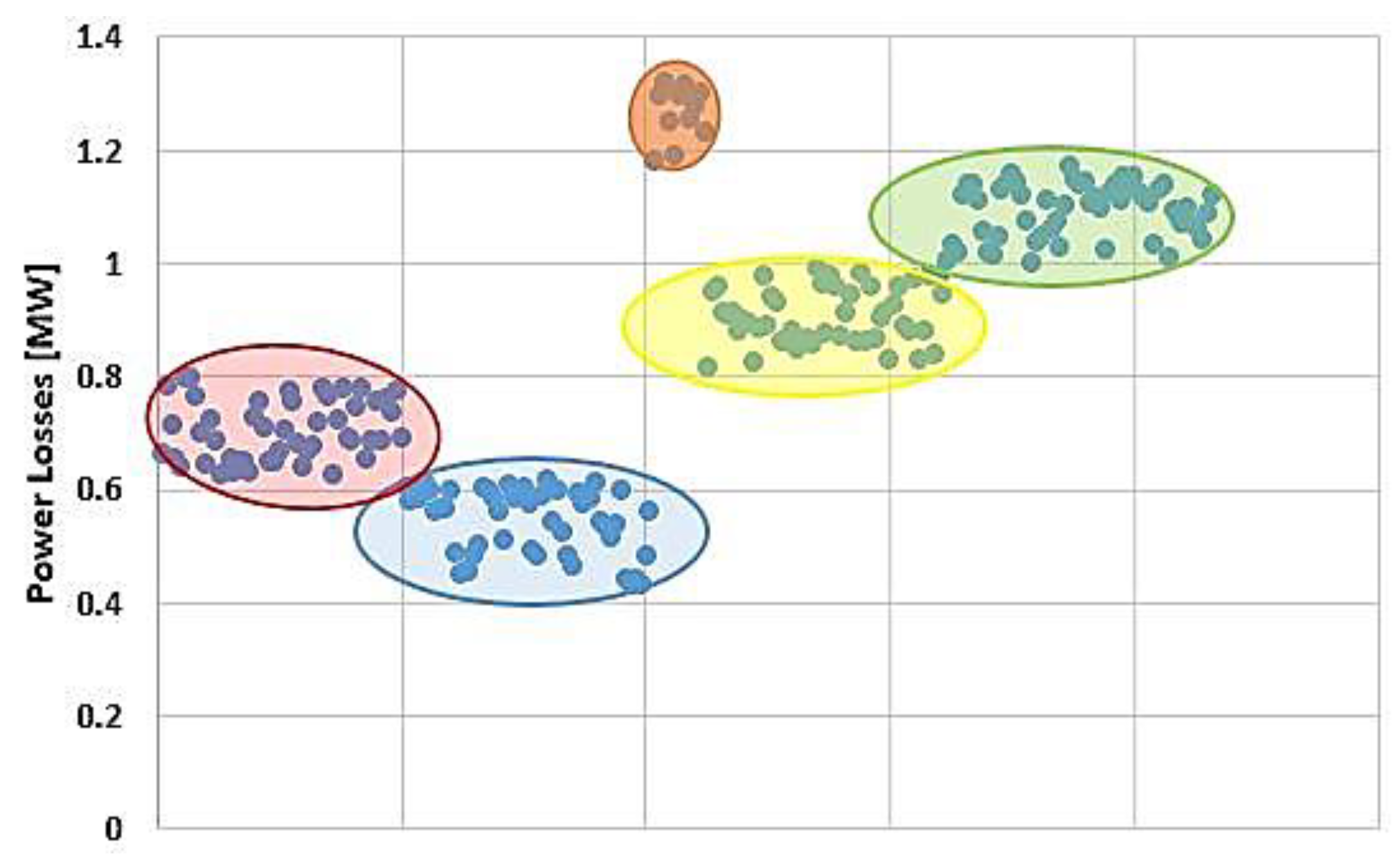

Power Losses [MW] |

C1 | 0.54 | 0.06 | 0.43 | 0.62 |

| C2 | 0.70 | 0.05 | 0.62 | 0.80 | |

| C3 | 0.90 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.99 | |

| C4 | 1.09 | 0.05 | 1.00 | 1.17 | |

| C5 | 1.26 | 0.05 | 1.18 | 1.32 |

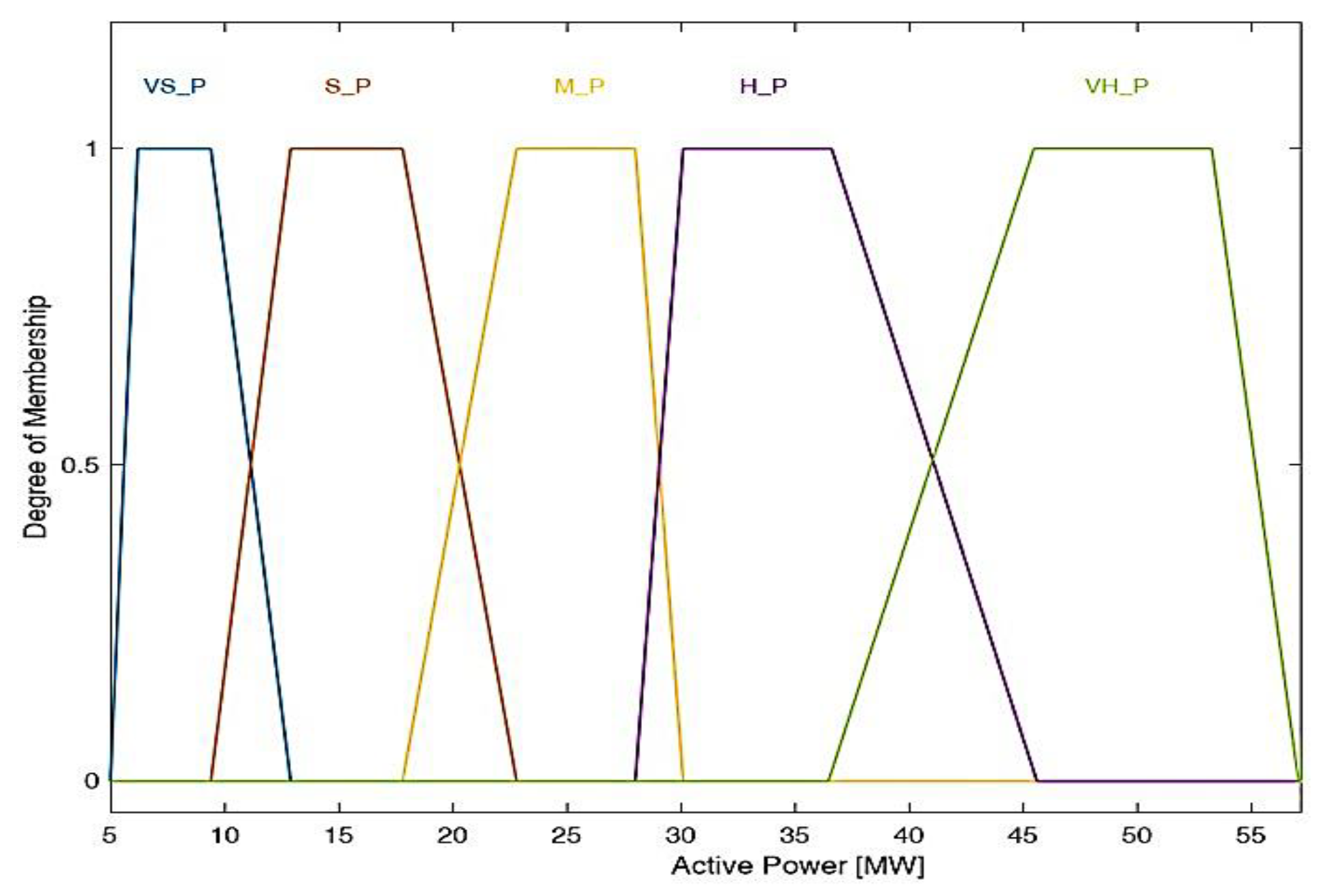

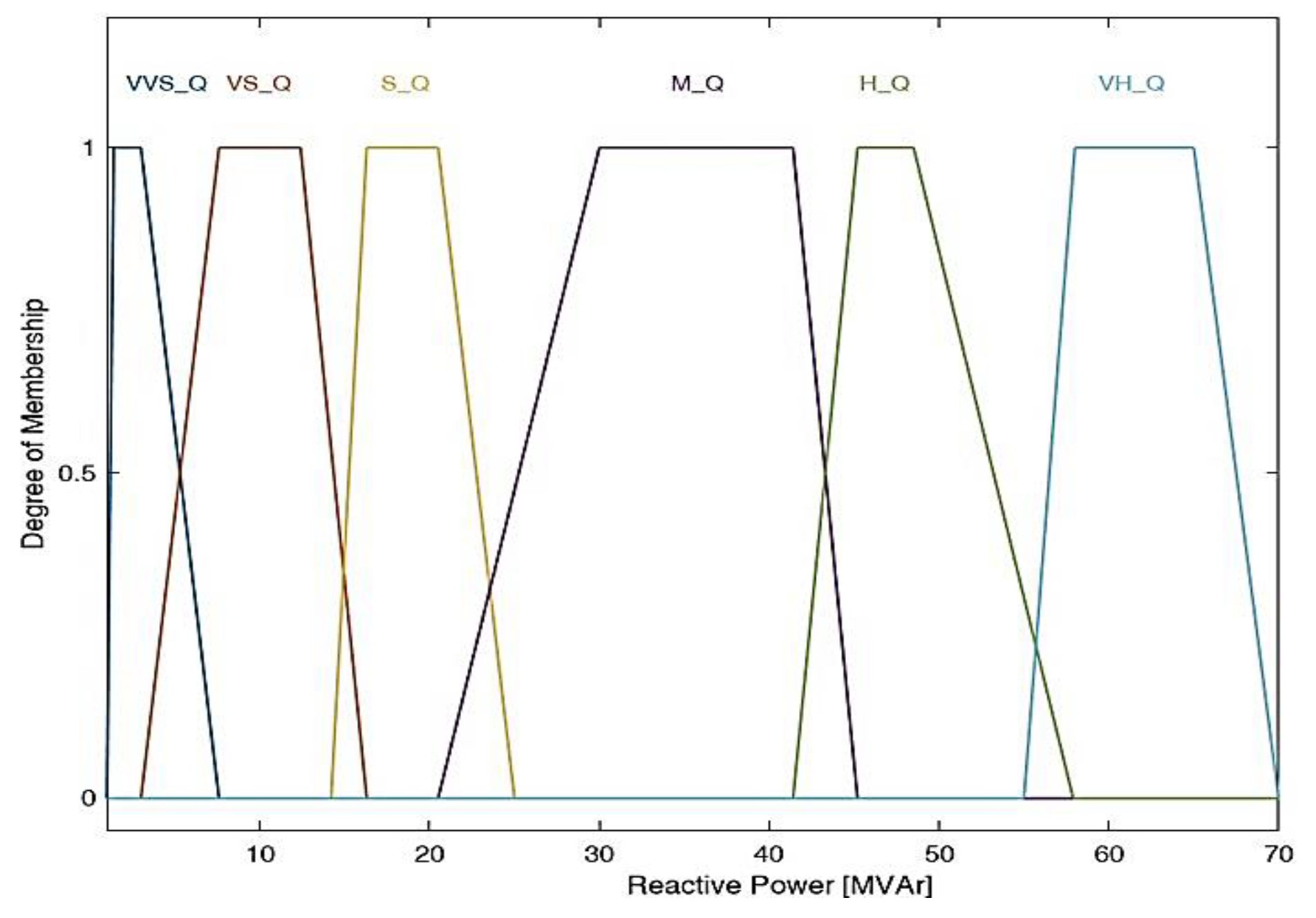

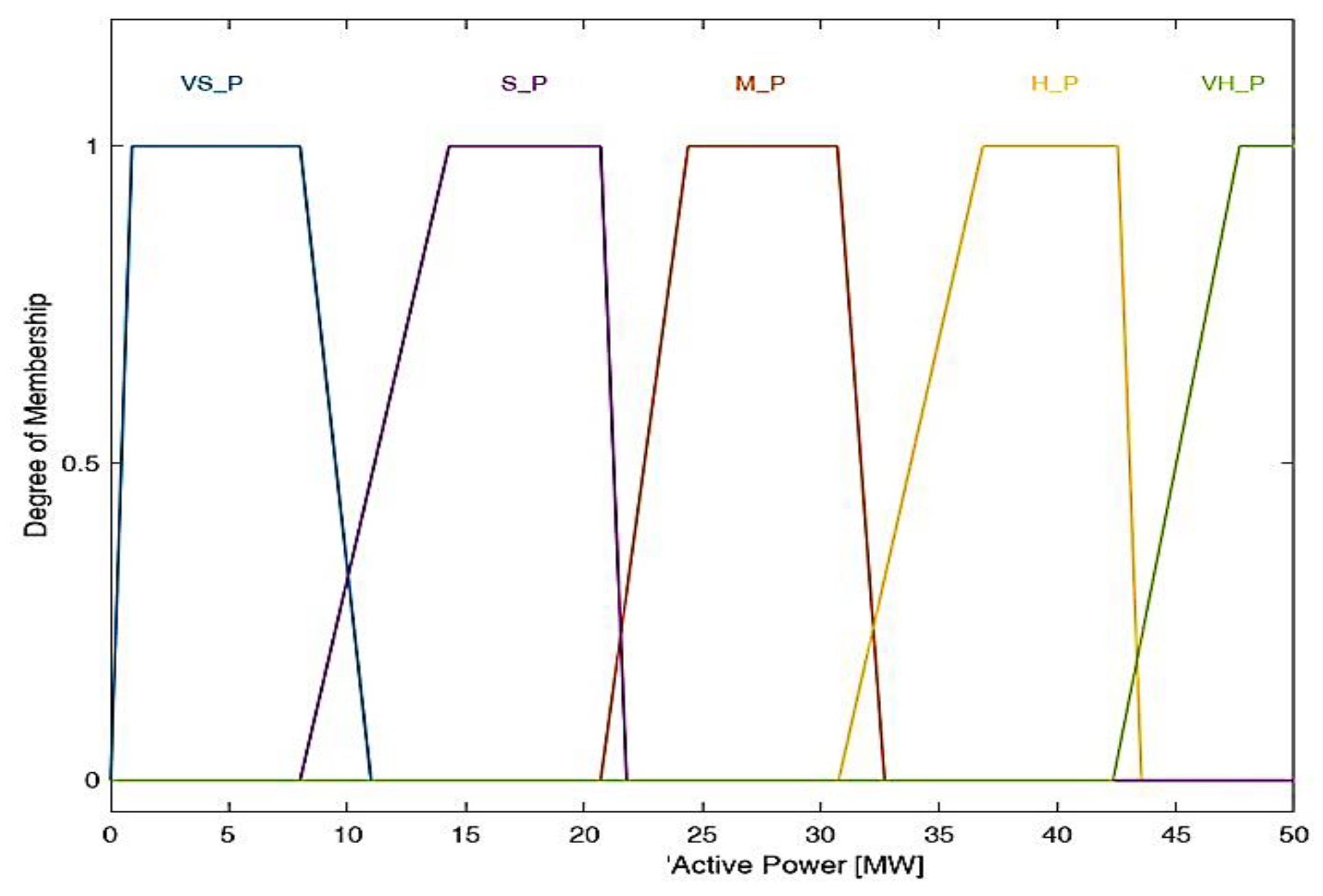

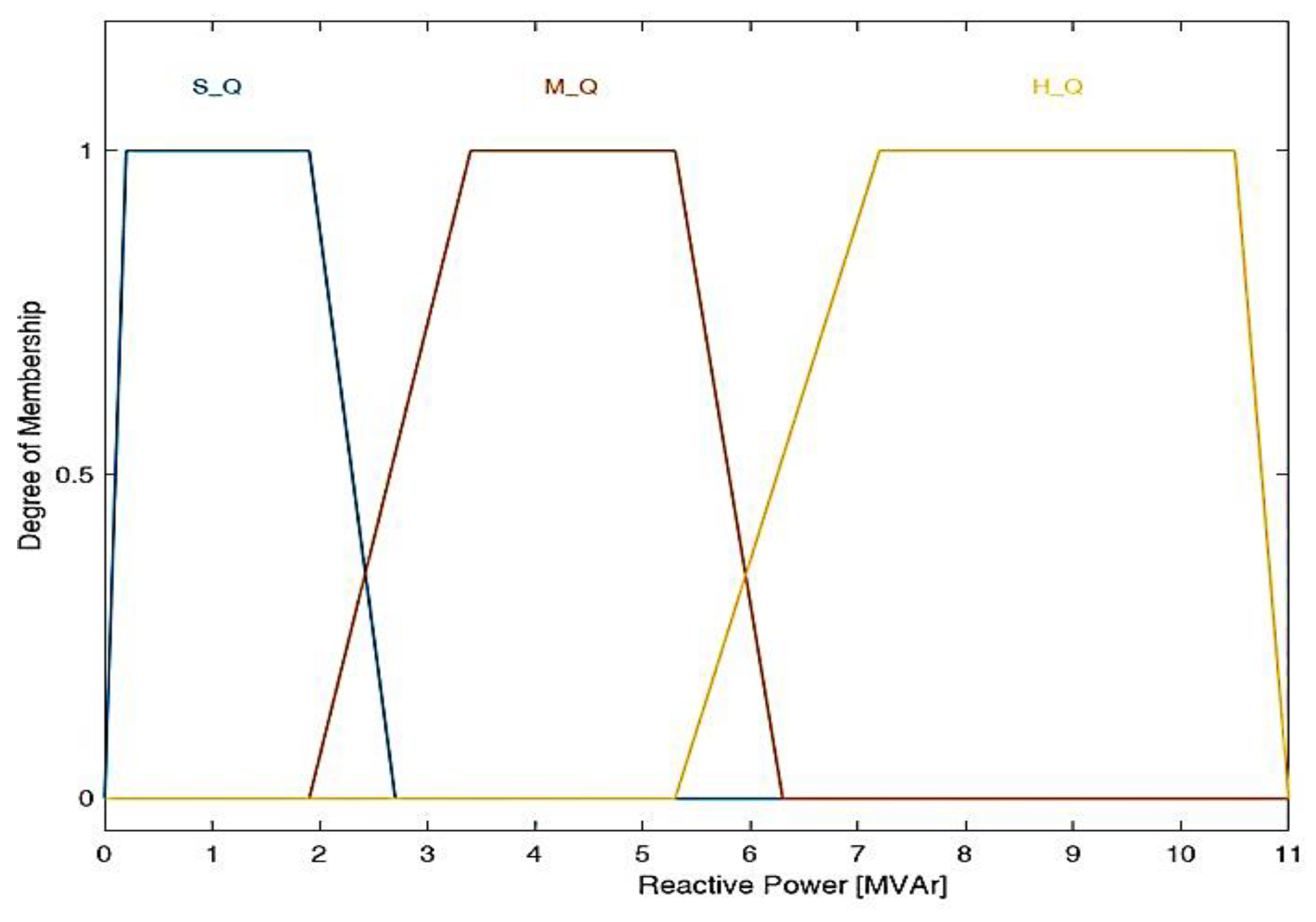

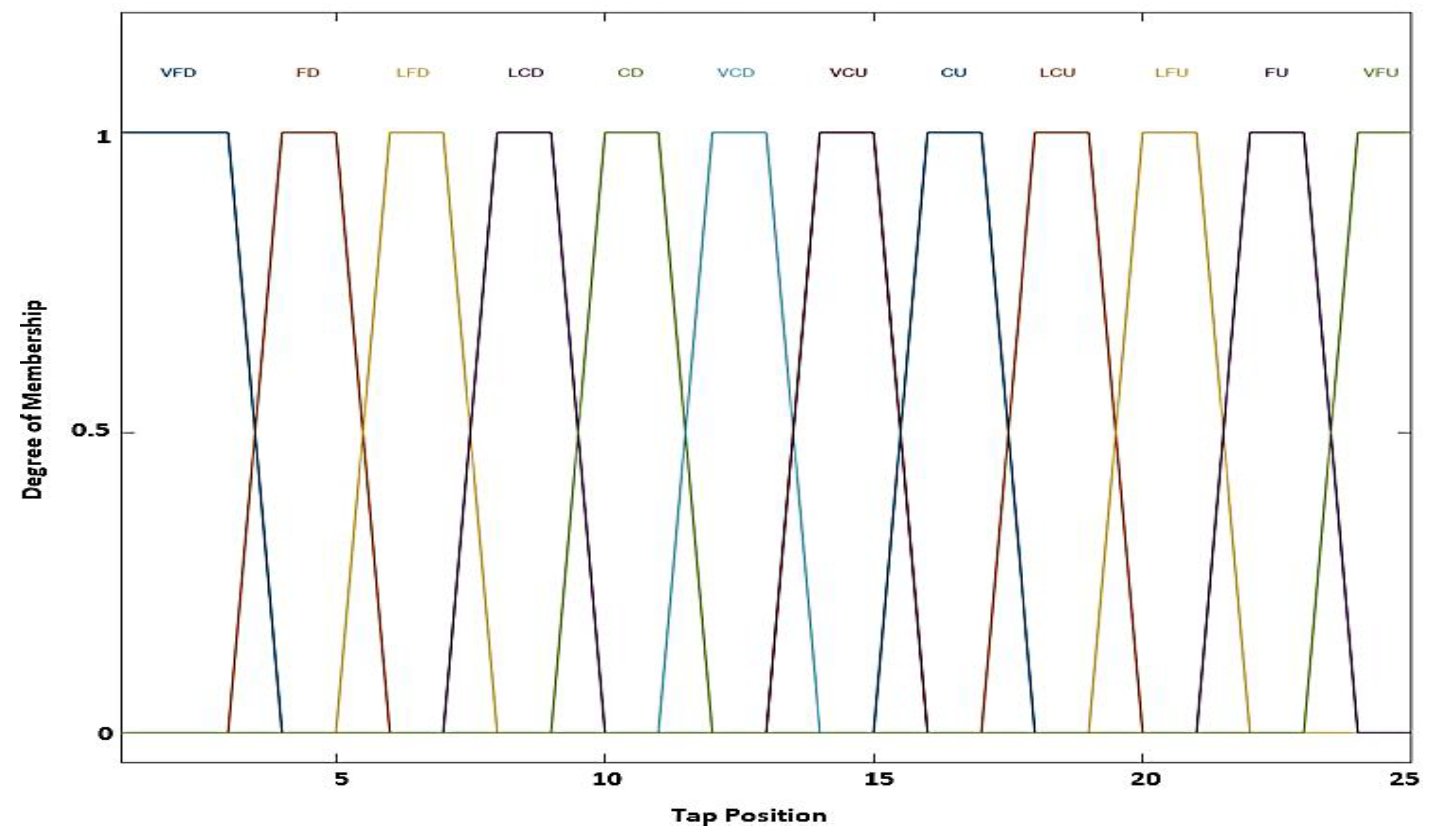

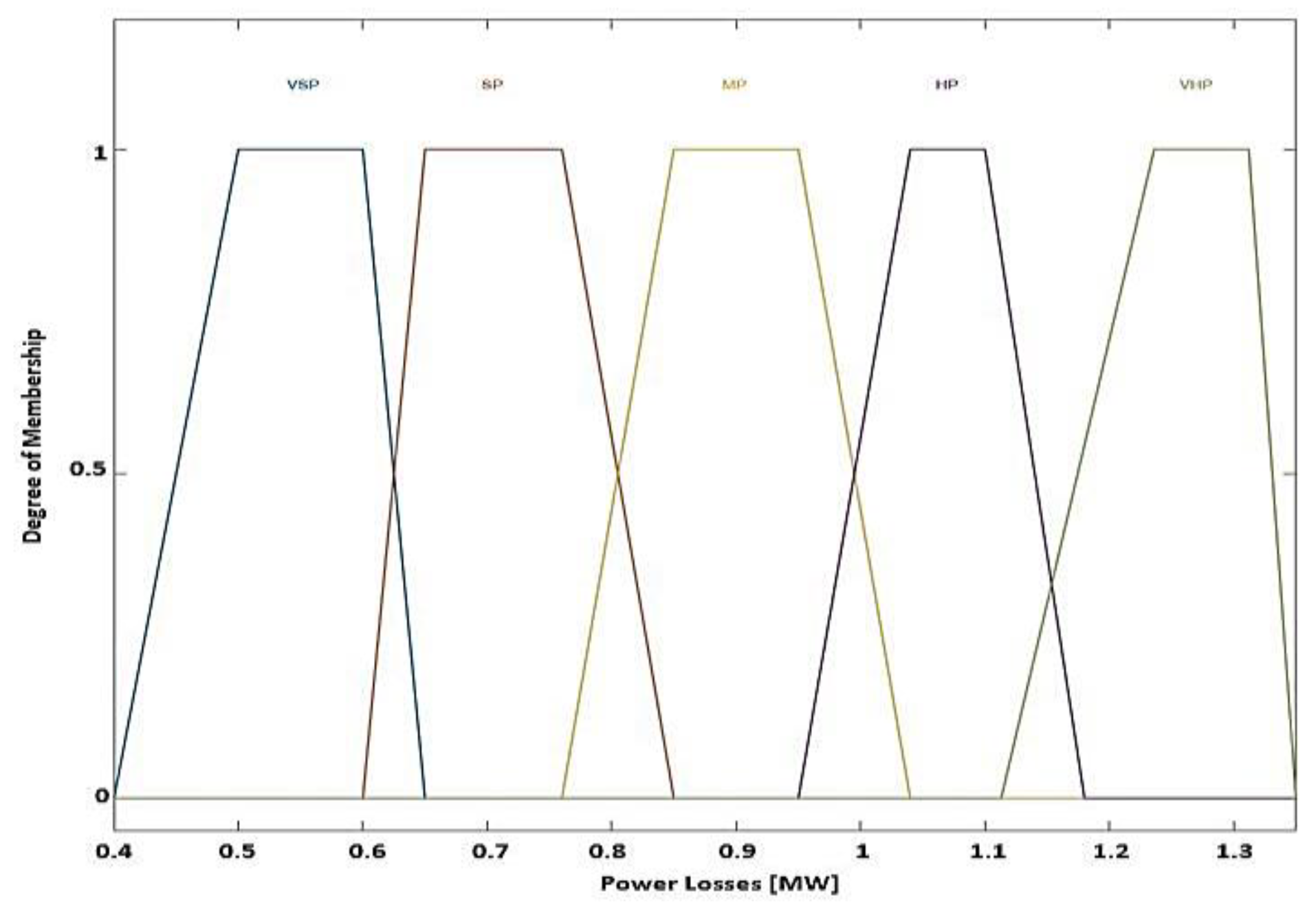

| Type of variable | Linguistic Categories | Break Points | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x1 | x2 | x3 | x4 | |||

| Input Variables |

Generated Active Power [MW] |

VS_P | 0 | 0.9 | 8.0 | 11.0 |

| S_P | 8.0 | 14.3 | 20.7 | 21.8 | ||

| M_P | 20.7 | 24.4 | 30.7 | 32.7 | ||

| H_P | 30.7 | 36.8 | 42.5 | 43.5 | ||

| VH_P | 42.5 | 47.7 | 50.0 | 50.0 | ||

|

Generated Reactive Power [MVAr] |

S_Q | 0 | 0.2 | 1.9 | 2.7 | |

| M_Q | 1.9 | 3.4 | 5.3 | 6.3 | ||

| H_Q | 5.3 | 7.2 | 10.5 | 11.0 | ||

|

Requested Active Power [MW] |

VS_P | 5.0 | 6.2 | 9.4 | 12.9 | |

| S_P | 9.4 | 12.9 | 17.8 | 22.8 | ||

| M_P | 17.8 | 22.8 | 28 | 30.1 | ||

| H_P | 28 | 30.1 | 36.6 | 45.6 | ||

| VH_P | 36.6 | 45.6 | 53.4 | 57 | ||

|

Requested Reactive Power [MVAr] |

VVS_Q | 1.0 | 1.4 | 3.0 | 7.6 | |

| VS_Q | 3.0 | 7.6 | 12.4 | 16.3 | ||

| S_Q | 14.2 | 16.3 | 20.5 | 25.0 | ||

| M_Q | 20.5 | 30.0 | 41.4 | 45.2 | ||

| H_Q | 41.4 | 45.2 | 48.5 | 57.9 | ||

| VH_Q | 55.0 | 58.0 | 65.0 | 70.0 | ||

| Output Variables | Tap Position | VFD | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| FD | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| LFD | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

| LCD | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| CD | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | ||

| VCD | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | ||

| VCU | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | ||

| CU | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | ||

| LCU | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | ||

| LFU | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | ||

| FU | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | ||

| VFU | 23 | 24 | 25 | 25 | ||

| Power Losses [MVA] | VS_dP | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.65 | |

| SP_dP | 0.6 | 0.65 | 0.76 | 0.85 | ||

| MP_dP | 0.76 | 0.85 | 0.95 | 1.04 | ||

| HP_dP | 0.95 | 1.04 | 1.1 | 1.18 | ||

| VHP_dP | 1.11 | 1.23 | 1.31 | 1.35 | ||

| Rule | P2req | Q2req | P3req | Q3req | P4req | Q4req | P6req | Q6req | P7req | Q7req | P8req | Q8req | P9req | Q9req | P10req | Q10req | P6inj | Q6inj | P8inj | Q8inj |

| R1 | H | M | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | M | VS | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | VS | S | VS | M | M | S | M |

| R2 | H | M | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | M | VS | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | VS | S | VS | M | H | S | M |

| R3 | H | H | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | M | VS | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | S | M | VS | H | H | S | M |

| R4 | VH | VH | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | M | S | VS | VVS | S | VVS | S | S | M | VS | H | H | S | M |

| R5 | VH | VH | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | H | S | VS | VVS | S | VVS | S | S | M | VS | H | H | S | M |

| R6 | VH | VH | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | H | S | VS | VVS | S | VVS | S | S | M | VS | VH | H | M | M |

| R7 | VH | VH | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | H | S | VS | VVS | S | VVS | S | S | M | VS | H | H | M | M |

| R8 | VH | VH | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | H | S | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | S | M | VS | H | H | S | M |

| R9 | VH | VH | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | H | S | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | S | H | VS | H | H | S | M |

| R10 | VH | H | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | H | S | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | S | M | VS | H | H | S | M |

| R11 | VH | H | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | H | VS | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | S | M | VS | H | H | S | M |

| R12 | VH | H | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | M | VS | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | S | M | VS | M | M | S | M |

| R13 | H | H | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | M | VS | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | S | M | VS | M | M | S | M |

| R14 | H | M | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | M | VS | VS | VSS | VS | VVS | S | VS | S | VS | M | H | S | S |

| R15 | H | M | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | M | VS | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | VS | S | VS | S | S | VS | S |

| R16 | H | M | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | M | VS | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | VS | S | VS | VS | S | VS | S |

| R17 | H | H | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | M | VS | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | S | M | VS | VS | S | VS | S |

| R18 | VH | VH | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | M | S | VS | VVS | S | VVS | S | S | M | VS | VS | S | VS | S |

| R19 | VH | VH | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | H | S | VS | VVS | S | VVS | S | S | M | VS | VS | S | VS | S |

| R20 | VH | VH | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | H | S | VS | VSS | S | VVS | S | S | M | VS | S | S | VS | S |

| R21 | VH | VH | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | H | S | VS | VVS | S | VVS | S | S | M | VS | S | M | VS | S |

| R22 | VH | VH | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | H | S | VS | VVS | S | VVS | S | S | M | VS | M | M | S | S |

| R23 | VH | VH | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | H | S | VS | VVS | S | VVS | S | S | M | VS | M | M | S | M |

| R24 | VH | VH | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | H | S | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | S | H | VS | M | H | S | M |

| R25 | VH | VH | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | H | S | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | S | H | VS | VH | H | M | M |

| R26 | VH | H | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | H | S | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | S | M | VS | VH | H | M | M |

| R27 | VH | H | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | H | VS | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | S | M | VS | VH | H | M | M |

| R28 | VH | H | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | M | VS | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | S | M | VS | VH | H | M | M |

| R29 | H | H | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | M | VS | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | S | M | VS | VH | H | M | M |

| R30 | H | M | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | M | VS | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | VS | S | VS | H | H | S | M |

| R31 | H | M | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | M | VS | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | VS | S | VS | VH | H | M | M |

| R32 | H | M | VS | VSS | VS | VSS | M | VS | VS | VVS | VS | VSS | S | VS | S | VS | H | H | S | M |

| R33 | H | H | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | M | VS | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | S | M | VS | M | M | S | S |

| R34 | VH | VH | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | M | S | VS | VVS | S | VVS | S | S | M | VS | S | M | VS | S |

| R35 | VH | VH | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | H | S | VS | VVS | S | VVS | S | S | M | VS | S | S | VS | S |

| R36 | VH | VH | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | H | S | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | S | M | VS | VS | S | VS | S |

| R37 | VH | VH | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | H | S | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | S | H | VS | VS | S | VS | S |

| R38 | VH | H | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | H | S | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | S | M | VS | VS | S | VS | S |

| R39 | VH | H | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | H | VS | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | S | M | VS | VS | S | VS | S |

| R40 | VH | H | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | M | VS | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | S | M | VS | VS | S | VS | S |

| R41 | H | H | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | M | VS | VS | VVS | VS | VVS | S | S | M | VS | VS | S | VS | S |

| Rule | T1-2 | T5-6 | T8-9 | ΔP | Rule | T1-2 | T5-6 | T8-9 | ΔP |

| R1 | LCD | LFD | LCD | VS | R22 | CD | LCD | CD | S |

| R2 | LCD | LFD | LCD | VS | R23 | CD | LCD | LCD | S |

| R3 | LCD | LFD | LCD | VS | R24 | CD | LCD | CD | S |

| R4 | CD | LCD | LCD | VS | R25 | CD | LCD | CD | S |

| R5 | CD | LCD | LCD | S | R26 | CD | LCD | LCD | VS |

| R6 | CD | CD | CD | S | R27 | CD | LCD | LCD | VS |

| R7 | CD | CD | CD | S | R28 | LCD | LFD | LFD | VS |

| R8 | CD | CD | CD | S | R29 | LCD | LFD | LFD | VS |

| R9 | CD | LCD | CD | S | R30 | LCD | LFD | LCD | VS |

| R10 | CD | LCD | LCD | S | R31 | LCD | LFD | LCD | VS |

| R11 | LCD | LCD | LCD | VS | R32 | LCD | LFD | LFD | VS |

| R12 | LCD | LFD | LCD | VS | R33 | LCD | LFD | LCD | VS |

| R13 | LCD | LFD | LCD | VS | R34 | CD | LCD | LCD | M |

| R14 | LCD | LFD | LFD | VS | R35 | CD | LCD | LCD | H |

| R15 | LCD | LFD | LFD | VS | R36 | CD | LCD | LCD | H |

| R16 | LCD | LFD | LFD | VS | R37 | CD | LCD | LCD | VH |

| R17 | LCD | LFD | LCD | S | R38 | CD | LCD | LCD | H |

| R18 | LCD | LFD | LCD | M | R39 | LCD | LFD | LCD | M |

| R19 | CD | LCD | LCD | H | R40 | LCD | LFD | LFD | S |

| R20 | CD | CD | CD | M | R41 | LCD | LFD | LFD | S |

| R21 | CD | LCD | CD | M |

| Hour | Objective function - Power Loss | Control Variables - Tap Position | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΓFIS [MW] |

Γ*I-FIS [MW] |

ΓSQP [MW] |

SQP | FIS | |||||

| T1-2 | T5-6 | T8-9 | T1-2 | T5-6 | T8-9 | ||||

| 1 | 0.527 | 0.511 | 0.4877 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 9 |

| 2 | 0.528 | 0.453 | 0.4479 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 7 |

| 3 | 0.528 | 0.453 | 0.4555 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 7 |

| 4 | 0.528 | 0.454 | 0.4568 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 7 |

| 5 | 0.527 | 0.547 | 0.482 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 9 |

| 6 | 0.527 | 0.602 | 0.4994 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 9 |

| 7 | 0.590 | 0.602 | 0.6028 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 9 |

| 8 | 0.590 | 0.729 | 0.7239 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 9 | 8 |

| 9 | 0.719 | 0.684 | 0.6852 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| 10 | 0.718 | 0.657 | 0.6275 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| 11 | 0.718 | 0.661 | 0.6323 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| 12 | 0.718 | 0.653 | 0.6534 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 10 |

| 13 | 0.718 | 0.657 | 0.6292 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| 14 | 0.721 | 0.646 | 0.6477 | 12 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| 15 | 0.721 | 0.65 | 0.6501 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| 16 | 0.72 | 0.597 | 0.5989 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 10 |

| 17 | 0.721 | 0.631 | 0.6312 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 10 |

| 18 | 0.721 | 0.728 | 0.7285 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 10 |

| 19 | 0.727 | 0.777 | 0.7533 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 11 |

| 20 | 0.722 | 0.707 | 0.7077 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 10 |

| 21 | 0.590 | 0.65 | 0.6488 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 10 | 10 |

| 22 | 0.590 | 0.583 | 0.582 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 9 | 9 |

| 23 | 0.530 | 0.582 | 0.5589 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 9 |

| 24 | 0.527 | 0.535 | 0.5113 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 9 |

| Hour | Objective function- Power Loss | Optimization Variables - Tap Position | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΓFIS [MW] |

Γ*I-FIS [MW] |

ΓSQP [MW] |

SQP | FIS | |||||

| T1-2 | T5-6 | T8-9 | T1-2 | T5-6 | T8-9 | ||||

| 1 | 0.527 | 0.49 | 0.4906 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 8 |

| 2 | 0.528 | 0.485 | 0.481 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 8 |

| 3 | 0.528 | 0.601 | 0.5864 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 7 |

| 4 | 0.528 | 0.626 | 0.6183 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 7 |

| 5 | 0.527 | 0.547 | 0.5402 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 7 |

| 6 | 0.721 | 0.725 | 0.7237 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 7 |

| 7 | 0.933 | 0.935 | 0.9251 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 8 |

| 8 | 1.040 | 1.063 | 1.0442 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| 9 | 1.070 | 1.127 | 1.1124 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| 10 | 1.020 | 1.075 | 1.0618 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| 11 | 1.010 | 1.076 | 1.0742 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 9 |

| 12 | 0.979 | 1.022 | 1.0252 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 |

| 13 | 0.900 | 0.964 | 0.9595 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 11 |

| 14 | 0.900 | 0.91 | 0.8895 | 12 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 11 |

| 15 | 0.721 | 0.782 | 0.7796 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| 16 | 0.721 | 0.698 | 0.6895 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| 17 | 0.720 | 0.688 | 0.6867 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 10 |

| 18 | 0.721 | 0.744 | 0.7448 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 10 |

| 19 | 0.727 | 0.803 | 0.7796 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 11 |

| 20 | 0.722 | 0.678 | 0.6526 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 11 |

| 21 | 0.605 | 0.599 | 0.5964 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| 22 | 0.530 | 0.525 | 0.5252 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 8 |

| 23 | 0.532 | 0.483 | 0.4836 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 7 |

| 24 | 0.531 | 0.469 | 0.4621 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 7 |

| Hour | Objective function - Power Loss | Optimization Variables - Tap Position | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΓFIS [MW] |

Γ*I-FIS [MW] |

ΓSQP [MW] |

SQP | FIS | |||||

| T1-2 | T5-6 | T8-9 | T1-2 | T5-6 | T8-9 | ||||

| 1 | 0.527 | 0.440 | 0.4405 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 8 |

| 2 | 0.528 | 0.433 | 0.4302 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 8 |

| 3 | 0.528 | 0.441 | 0.4414 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 8 |

| 4 | 0.528 | 0.437 | 0.4332 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 8 |

| 5 | 0.527 | 0.508 | 0.4843 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 9 |

| 6 | 0.530 | 0.583 | 0.5601 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 9 |

| 7 | 0.875 | 0.759 | 0.738 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| 8 | 0.932 | 1.013 | 1.0099 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 10 | 10 |

| 9 | 1.030 | 1.108 | 1.0936 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| 10 | 1.060 | 1.091 | 1.0772 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| 11 | 1.010 | 1.07 | 1.0679 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 9 |

| 12 | 1.010 | 1.098 | 1.0953 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 9 |

| 13 | 0.968 | 1.073 | 1.0708 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 9 |

| 14 | 0.968 | 1.059 | 1.0594 | 12 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 9 |

| 15 | 0.968 | 1.045 | 1.0423 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 9 |

| 16 | 0.966 | 0.987 | 0.9778 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 9 |

| 17 | 1.070 | 1.109 | 1.088 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| 18 | 1.180 | 1.298 | 1.2759 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| 19 | 1.230 | 1.321 | 1.300 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| 20 | 1.200 | 1.251 | 1.2288 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| 21 | 1.110 | 1.142 | 1.1182 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| 22 | 0.907 | 0.958 | 0.9429 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 8 |

| 23 | 0.720 | 0.802 | 0.7733 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 6 | 7 |

| 24 | 0.721 | 0.696 | 0.6881 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 7 |

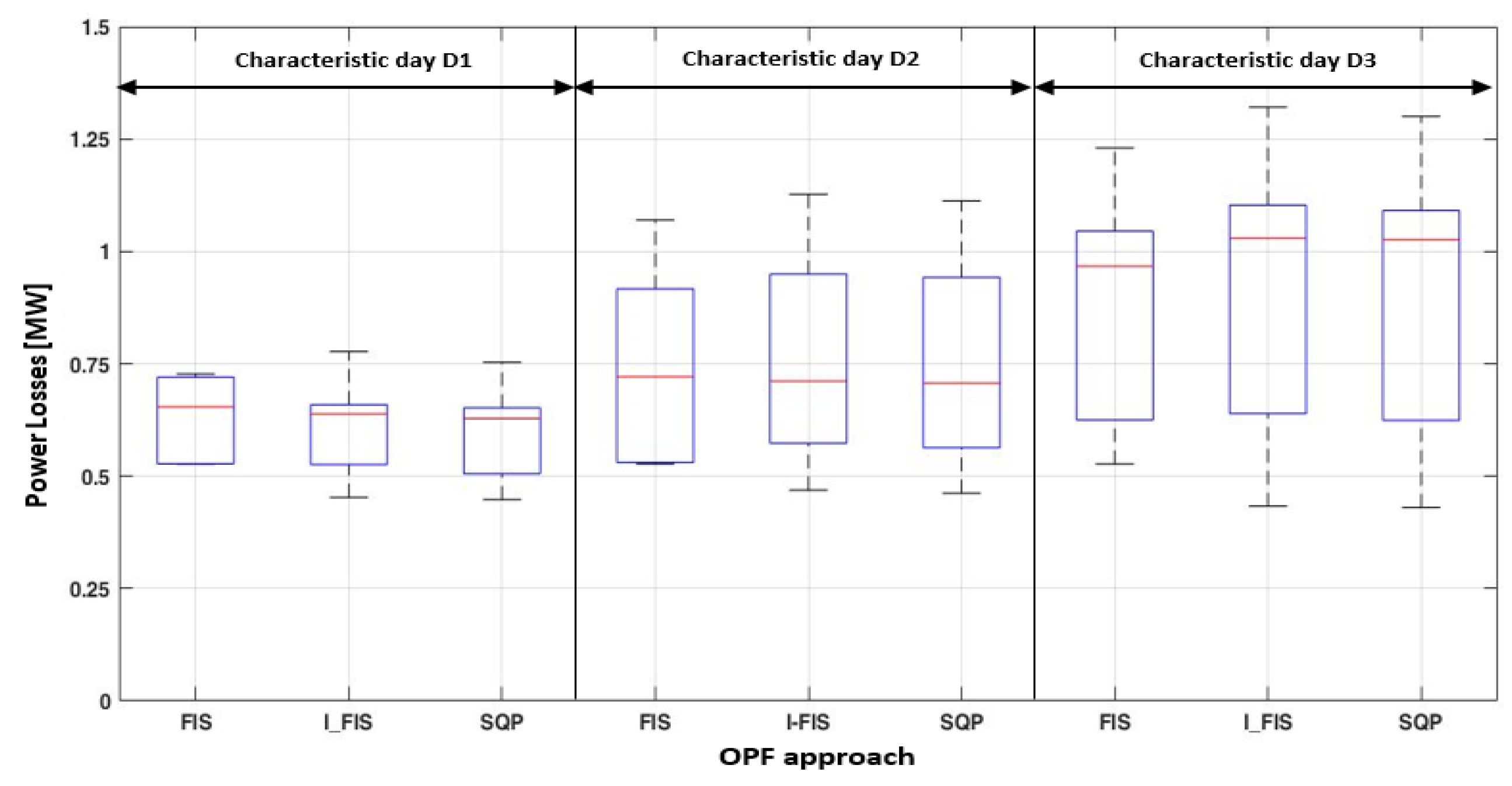

| Quartile | Characteristic Day D1 | Characteristic Day D2 | Characteristic Day D2 | ||||||

| FIS | I-FIS | SQP | FIS | I-FIS | SQP | FIS | I-FIS | SQP | |

| Q0 | 0.53 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.53 | 0.43 | 0.43 |

| Q1 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.51 | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.56 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.62 |

| Q2 | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.72 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.97 | 1.03 | 1.03 |

| Q3 | 0.72 | 0.66 | 0.65 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 1.05 | 1.10 | 1.09 |

| Q4 | 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 1.07 | 1.13 | 1.11 | 1.23 | 1.32 | 1.30 |

| Hour | Characteristic Day D1 | Characteristic Day D2 | Characteristic Day D3 | ||||||

| FIS | I-FIS | SQP | FIS | I-FIS | SQP | FIS | I-FIS | SQP | |

| 1 | 99.31 | 99.33 | 99.36 | 99.32 | 99.37 | 99.37 | 99.00 | 99.16 | 99.16 |

| 2 | 99.22 | 99.33 | 99.34 | 99.27 | 99.33 | 99.33 | 98.99 | 99.17 | 99.18 |

| 3 | 99.21 | 99.33 | 99.32 | 99.46 | 99.39 | 99.41 | 98.71 | 98.92 | 98.92 |

| 4 | 99.23 | 99.34 | 99.33 | 99.48 | 99.39 | 99.40 | 99.06 | 99.22 | 99.23 |

| 5 | 99.30 | 99.28 | 99.36 | 99.52 | 99.50 | 99.51 | 99.31 | 99.33 | 99.36 |

| 6 | 99.32 | 99.23 | 99.36 | 99.38 | 99.38 | 99.38 | 99.43 | 99.37 | 99.40 |

| 7 | 99.37 | 99.36 | 99.36 | 99.33 | 99.32 | 99.33 | 99.26 | 99.36 | 99.38 |

| 8 | 99.48 | 99.36 | 99.37 | 99.31 | 99.30 | 99.31 | 99.37 | 99.32 | 99.32 |

| 9 | 99.30 | 99.33 | 99.33 | 99.31 | 99.27 | 99.28 | 99.32 | 99.27 | 99.28 |

| 10 | 99.17 | 99.24 | 99.27 | 99.31 | 99.28 | 99.28 | 99.29 | 99.27 | 99.28 |

| 11 | 99.18 | 99.24 | 99.28 | 99.32 | 99.27 | 99.28 | 99.32 | 99.28 | 99.28 |

| 12 | 99.23 | 99.30 | 99.30 | 99.32 | 99.29 | 99.28 | 99.32 | 99.26 | 99.27 |

| 13 | 99.20 | 99.27 | 99.30 | 99.35 | 99.30 | 99.30 | 99.34 | 99.27 | 99.27 |

| 14 | 99.21 | 99.29 | 99.29 | 99.30 | 99.29 | 99.31 | 99.33 | 99.27 | 99.27 |

| 15 | 99.25 | 99.33 | 99.33 | 99.39 | 99.34 | 99.34 | 99.34 | 99.29 | 99.29 |

| 16 | 99.19 | 99.33 | 99.32 | 99.34 | 99.36 | 99.36 | 99.32 | 99.31 | 99.31 |

| 17 | 99.26 | 99.35 | 99.35 | 99.34 | 99.37 | 99.37 | 99.31 | 99.29 | 99.30 |

| 18 | 99.38 | 99.37 | 99.37 | 99.39 | 99.37 | 99.37 | 99.32 | 99.25 | 99.26 |

| 19 | 99.39 | 99.35 | 99.37 | 99.41 | 99.35 | 99.37 | 99.30 | 99.25 | 99.26 |

| 20 | 99.37 | 99.38 | 99.38 | 99.29 | 99.33 | 99.36 | 99.30 | 99.27 | 99.28 |

| 21 | 99.45 | 99.39 | 99.39 | 99.36 | 99.37 | 99.37 | 99.31 | 99.29 | 99.31 |

| 22 | 99.38 | 99.39 | 99.39 | 99.26 | 99.27 | 99.27 | 99.37 | 99.33 | 99.34 |

| 23 | 99.43 | 99.37 | 99.39 | 99.14 | 99.22 | 99.22 | 99.42 | 99.36 | 99.38 |

| 24 | 99.36 | 99.35 | 99.38 | 98.99 | 99.05 | 99.12 | 99.36 | 99.39 | 99.39 |

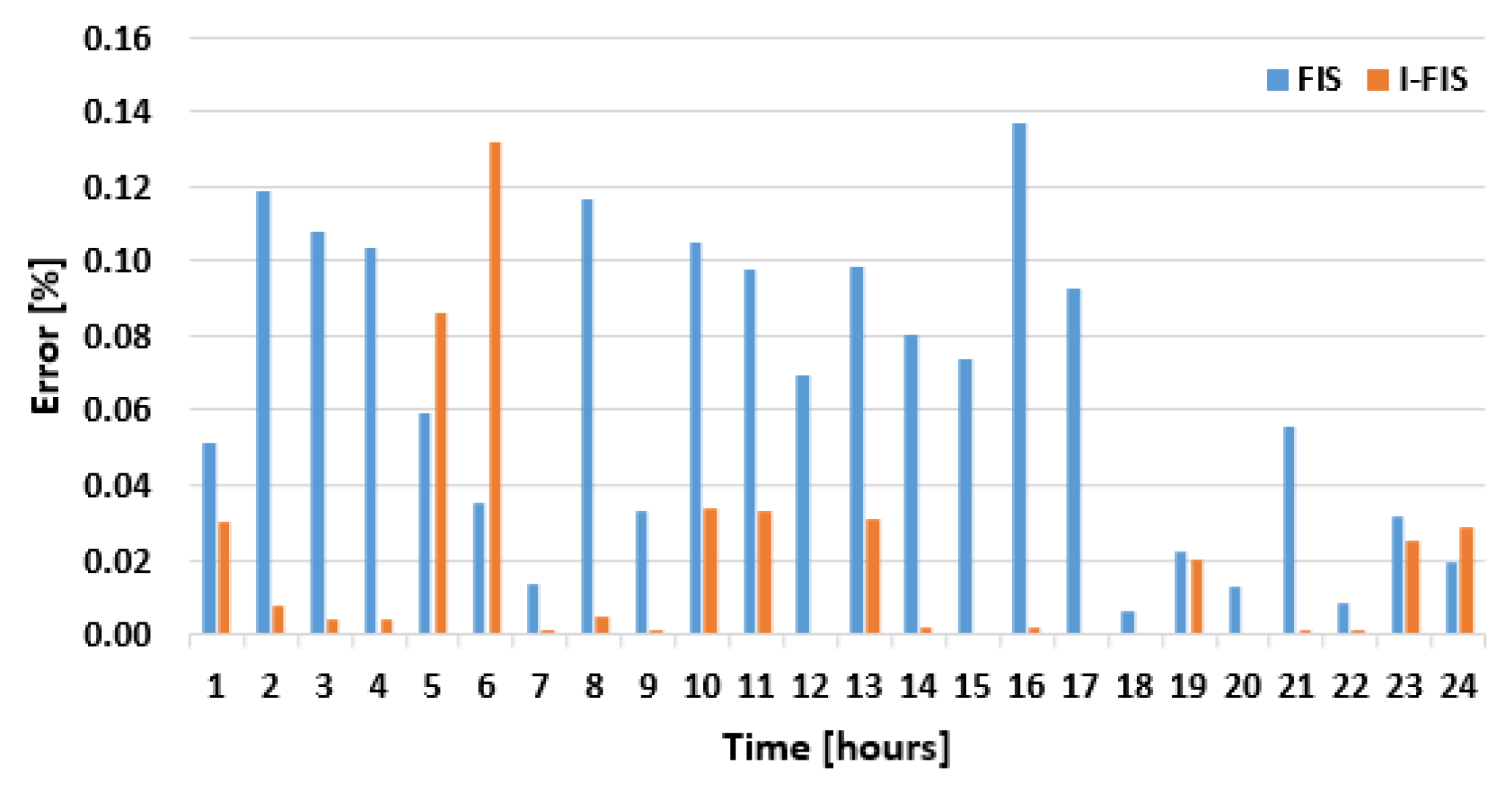

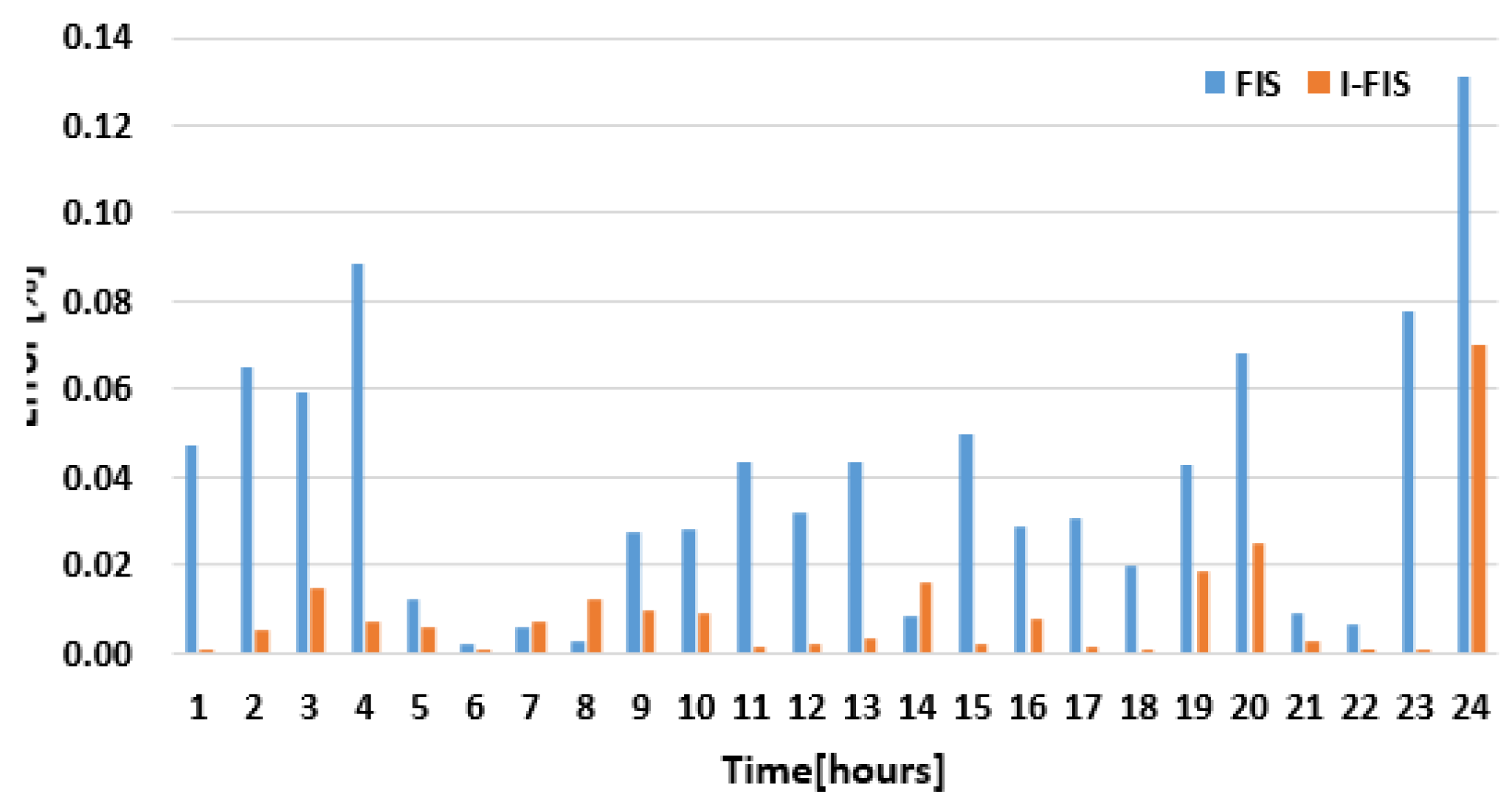

| Hour | Characteristic Day D1 | Characteristic Day D2 | Characteristic Day D3 | |||

| PEFISEN | PEI-FISEN | PEFISEN | PEI-FISEN | PEFISEN | PEI-FISEN | |

| 1 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.`01 | 0.19 | 0.01 |

| 3 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.00 |

| 4 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.01 |

| 5 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| 6 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| 7 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.02 |

| 8 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.00 |

| 9 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| 10 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| 11 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| 12 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 |

| 13 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.00 |

| 14 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.00 |

| 15 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 |

| 16 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| 17 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| 18 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| 19 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| 20 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| 21 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| 22 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| 23 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| 24 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).