1. Introduction

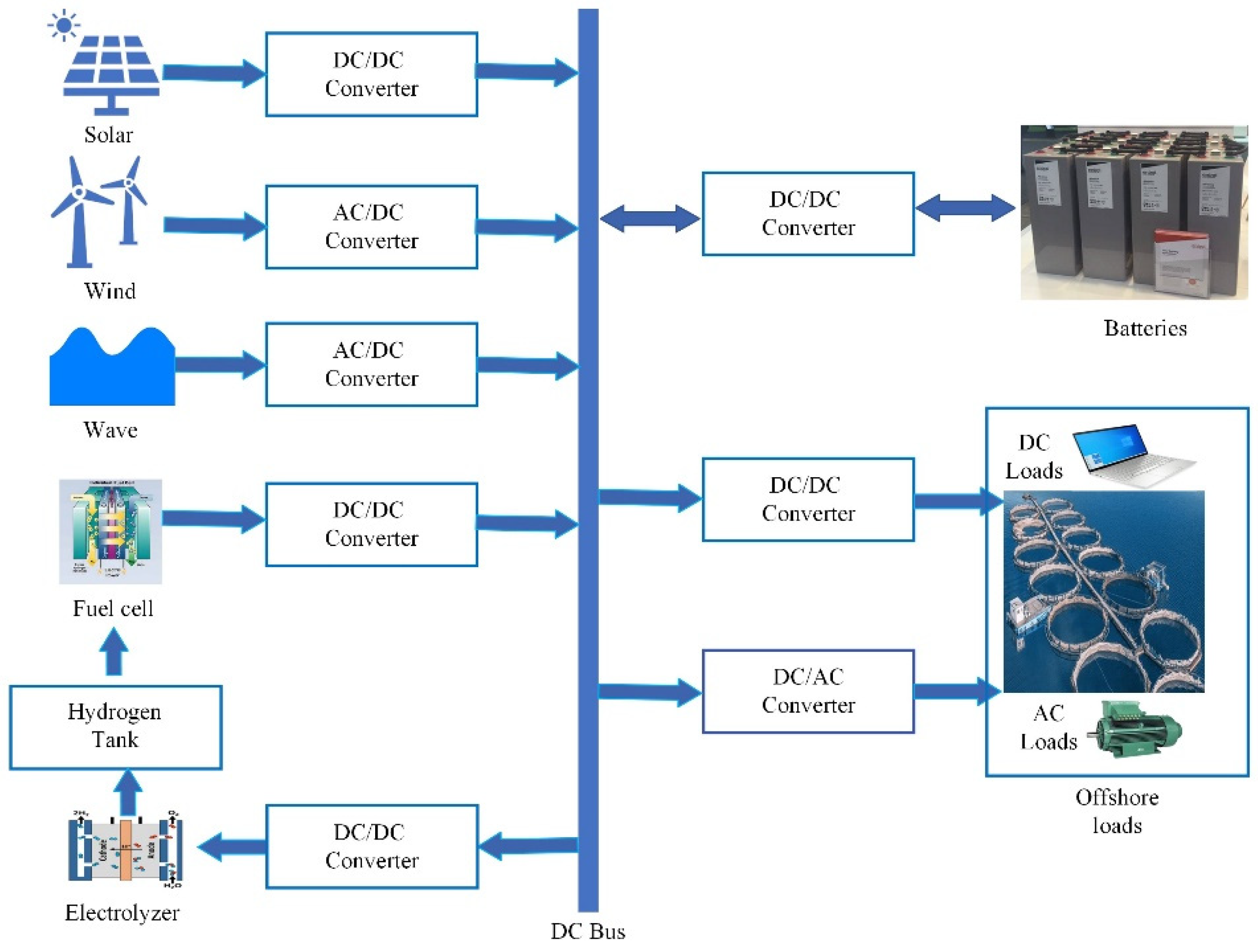

DC microgrids (MGs) integrate diverse distributed renewable energy sources (DRESs), such as solar panels, wind turbines, wave energy converters, and energy storage devices (ESDs) like batteries, and supercapacitors. It can also be combined with hydrogen technology, including electrolysers, hydrogen storage, and fuel cells. This versatility not only significantly reduces greenhouse gas emissions compared to systems reliant on diesel fuel, but also enables better matching of generation with demand. For systems comprising DC-powered modern electronic devices, variable-speed drive motors, and DC motor driven pumps and equipment, DC microgrids can be particularly advantageous [

1]. Benefits of DC MGs over conventional diesel-based AC systems include improved efficiency, simpler system designs, seamless integration with DRESs, enhanced compatibility with ESDs and modern electronic loads, and the elimination of frequency, reactive power flow, and skin effect issues [

2,

3,

4]. These attributes make DC MGs particularly well-suited for powering remote communities and offshore industries, where low-cost, reliable systems and a shift away from reliance on diesel fuel is desirable.

Integrating various DRESs into a single DC MG network presents significant challenges in maintaining small-signal stability under variations in generation and load. These challenges include maintaining voltage stability under all operating conditions, ensuring accurate power sharing, balancing power generation with demand, and upholding power quality [

5,

6,

7]. Small-signal instability can result in poor voltage regulation, increased settling times and oscillations, and degraded controller performance.

ESDs can compensate for the intermittent generation from DRESs in DC MGs, ensuring a stable and continuous power supply [

8,

9]. They play a critical role in balancing supply and demand by storing surplus energy during periods of high generation and releasing it during demand peaks, thus enhancing the system’s overall reliability. Bidirectional DC-DC converters are essential components of DC MGs because they connect ESDs to DC buses, improving the reliability, efficiency, and stability of operations. These converters are pivotal for managing the power flow between storage devices and DC buses while also regulating voltage and current levels [

10]. However, controlling bidirectional DC-DC converters in DC MGs presents significant challenges in maintaining required voltage levels at the outputs of different units, particularly in systems integrated with various DRESs and ESDs. Without an adequate control approach, this integration can result in complex dynamic behaviour which may lead to stability issues [

10,

11].

Conventional droop control is widely used in DC MGs due to its simplicity. However, significant challenges, particularly in droop-coefficient selection, can lead to voltage fluctuations and inaccurate current sharing [

7,

12,

13]. To address these challenges and improve the stability and performance of DC MGs, various strategies have been proposed, including hybrid power sharing control [

14] and several dual-loop cascaded control structures [

15,

16,

17].

In these cascaded configurations, the inner loop controls the battery current, while the outer loop stabilises DC bus voltage, providing a systematic and effective approach to MG management. Specifically, a dual-loop control structure designed to regulate both DC bus and supercapacitor voltage was developed in [

15]. Additionally, a hybrid control structure was introduced in [

16] to regulate DC bus voltage and ensure accurate battery current management. Another approach, a two-loop-based nested control structure, has been developed to regulate the DC bus voltage, considering the state of charge (SoC) of batteries [

17].

Prediction-based cascaded control [

18,

19] and sliding mode control [

20,

21] systems have also been proposed for DC bus voltage regulation, which significantly enhance battery lifespan. However, these techniques may require high-speed processors, optimisation, and additional measurements, which increase implementation costs and computational complexity. The small-signal stability analysis of the cascaded control approach has been investigated to study the dynamic responses under various operating conditions, such as load variations, changes in generations, topology changes, and battery charging and discharging [

22,

23,

24]. Furthermore, sensitivity analysis has been conducted for DC MGs to assess the impact of variations in system parameters [

25,

26,

27].

A proportional-integral-derivative (PID)-based cascaded control system may not adequately provide fast transient responses and could negatively impact voltage quality [

28]. In addition, the time-consuming process of tuning PID parameters complicates its usage. Although PID-based cascaded control systems are designed to optimise transient responses, they often result in higher overshoot due to tuning issues, leading to significant variations in DC bus voltage [

15,

16,

17]. Additionally, the output current and voltage fluctuations caused by this controller compromise system stability and prolong battery response time.

The average current mode (ACM) control approach is the optimal choice for battery charging and discharging due to its direct control over battery current and stable operation at any duty ratio [

29]. An ACM-based cascaded controller has been designed to analyse the small-signal stability of DC MGs [

30]. However, the performance is limited by the varying operating voltage of the supercapacitor, resulting in low gain and phase margin. Additionally, an ACM-based cascaded control approach has been introduced for DC MGs [

31], although this study lacks detailed analysis and mathematical modelling. Small-signal stability and sensitivity analysis are crucial, especially when considering case studies designed to support practical implementation.

To identify issues associated with DC MGs, various control modes have been analysed, including PID voltage mode control, PID-based cascaded control, and ACM-based cascaded control [

32]. This analysis has revealed that ACM-based cascaded control is the most suitable method for DC MGs. The proposed approach offers several major advantages over the conventional PID controllers commonly used in existing literature [

15,

16,

17]. These advantages include satisfactory transient responses with fast recovery, low voltage deviations, higher phase margin, and increased bandwidth. It also ensures stable operation under normal conditions and during disturbances, such as load and generation changes, as well as during battery charging and discharging.

Motivated by the aforementioned discussion, an ACM-based cascaded control approach is initially proposed for DC MGs, followed by the development of an analytical small-signal model. This model examines how variations in control and system parameters impact system dynamics. Stability is assessed using the root locus and Bode plot methods, with a focus on transient, frequency, and performance response metrics, such as the integral of absolute error (IAE), and the integral of time multiplied by absolute error (ITAE) [

33,

34]. The sensitivity of the DC MG is analysed to pinpoint which parameters significantly impact its performance. Ultimately, the effectiveness of the proposed controller’s performance is validated through Electromagnetic Transient (EMT) simulations and compared with a conventional PID-based cascaded controller. In short, this study makes the following key contributions:

1) An ACM-based cascaded control approach is proposed for DC MGs that addresses a wide range of generation and load variations, making it suitable for application in remote communities and offshore industries.

2) The impact of system and controller parameters under small-signal disturbances is analysed, with a particular focus on addressing challenges associated with DC MGs.

3) The system’s performance is evaluated through EMT simulations, demonstrating superiority over a conventional PID-based cascaded controller.

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows: a generic representation of a DC MG and a converter circuit model of a PV/battery-based MG are first introduced in Section II. Section III illustrates the proposed control topology, including the mathematical model of the inner and outer loops, and the equivalent small-signal model of the controller. Section IV describes the stability analysis of the DC MG network, comparing the use of conventional PID controllers and the proposed ACM-based cascaded controller. Simulation results are discussed in Section V, with the DC MG network modelled in MATLAB/Simulink. Section VI finally concludes the paper.

5. Simulation Results

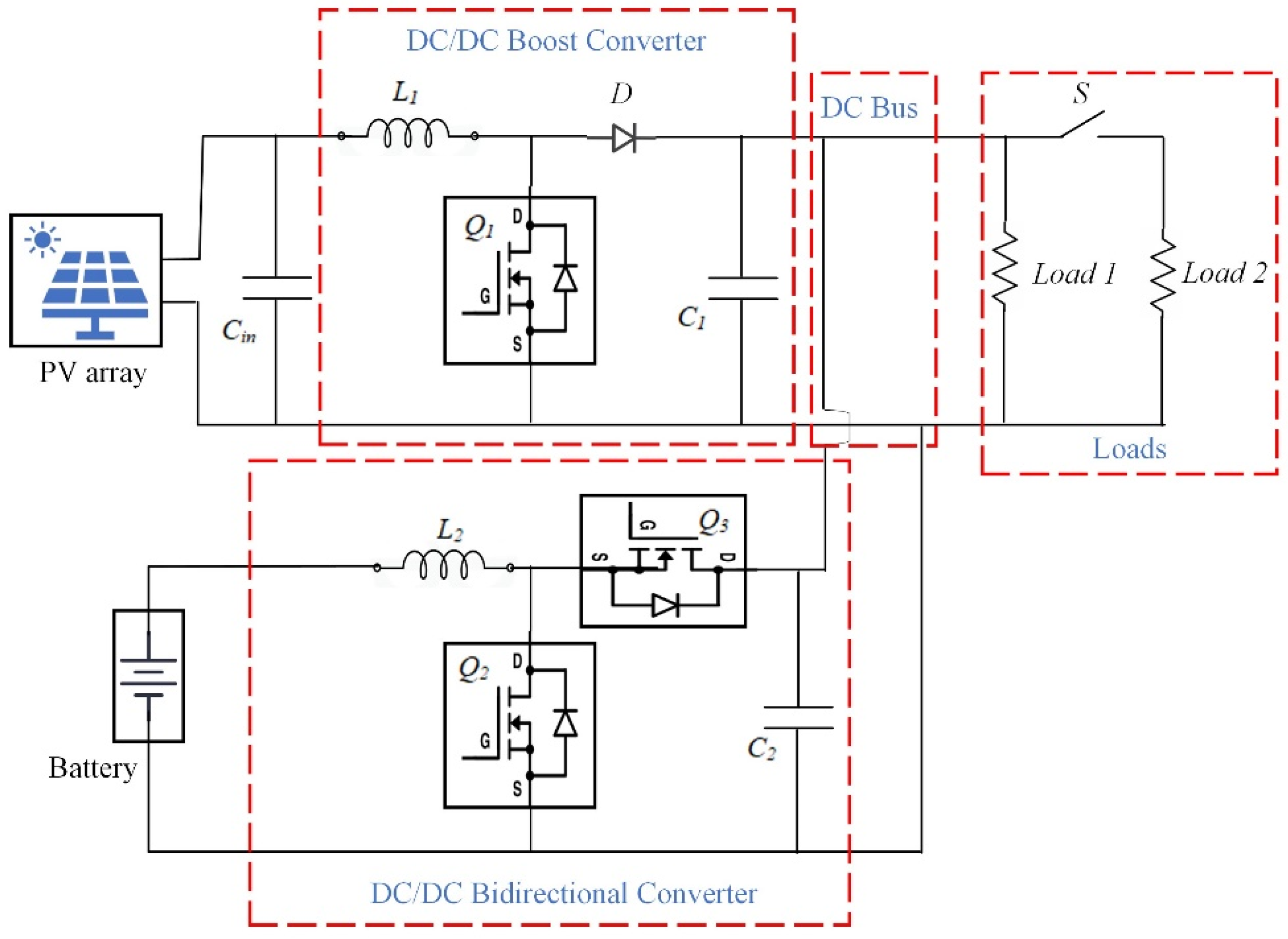

The DC MG system shown in

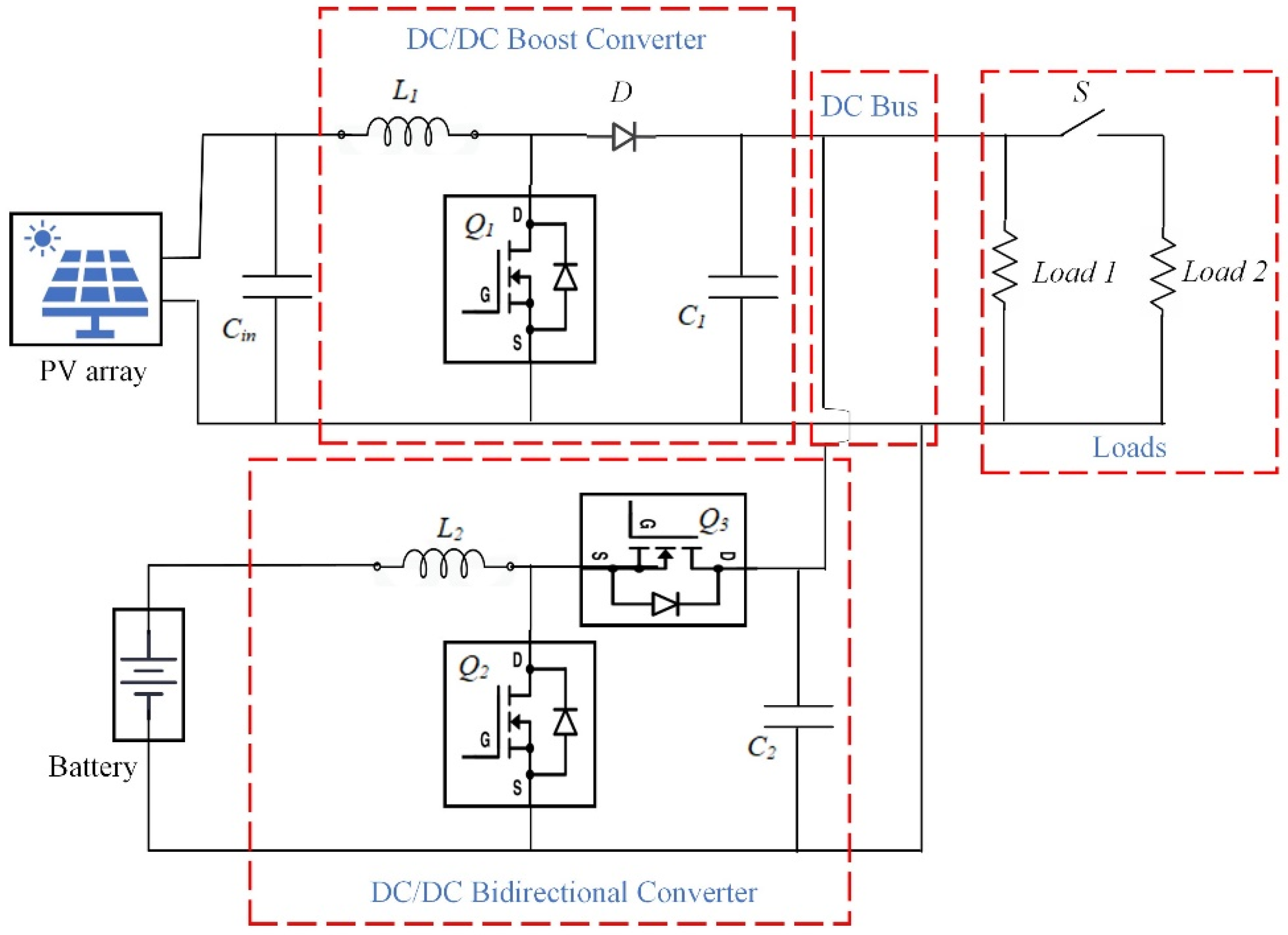

Figure 2, along with the control scheme for the DC-DC bidirectional converter shown in

Figure 3, was implemented on the MATLAB/Simulink platform. The effectiveness of the proposed ACM-based cascaded controller was assessed by comparing it with performance using a conventional PID controller, including transient parameters, power quality measurements, and controller performance criteria, such as settling time, voltage regulation, total harmonic distortion (THD), IAE, and ITAE. The parameters used in this model are detailed in

Table 2. The system includes a 1.5 kW solar panel designed to supply a 2 kW load. It is connected to a 50 Ah battery unit, which stores excess energy by charging when the solar panel generates more than demand. Once the battery reaches its charging limit, solar power generation can be moderated by adjusting the operating point to below its maximum power point, ensuring a balance between generation and demand. When the solar panel generates less than the power demand, the battery compensates by discharging to supply additional power to the load. The battery discharges up to a limit; thereafter, to maintain the system balance, non-essential loads can be selectively reduced based on priority. The performance of the controller was evaluated through dynamic analysis, which provides a deeper understanding of the system’s behaviour when load and generation are varied. This controller effectively maintains the DC bus voltage at 380 V, both under normal operating conditions and in response to step changes in load or generation.

5.1. Load Variations

To investigate the impact of load variations on the DC bus voltage, the load was incrementally adjusted between 5% and 80%. The system’s performance was evaluated under various scenarios, including 5%, 25%, 50%, and 80% increases and decreases in load. It was observed that the system maintains stability under all changes in load, with overshoot/undershoot in DC bus voltage tending to increase proportionally with size of step change in load. This overshoot is not a major concern for this specific system, where the primary focus is on the speed of the controller. Fast controller response, is crucial, enabling rapid adjustment to battery operation during disturbances, thus ensuring system stability can be maintained.

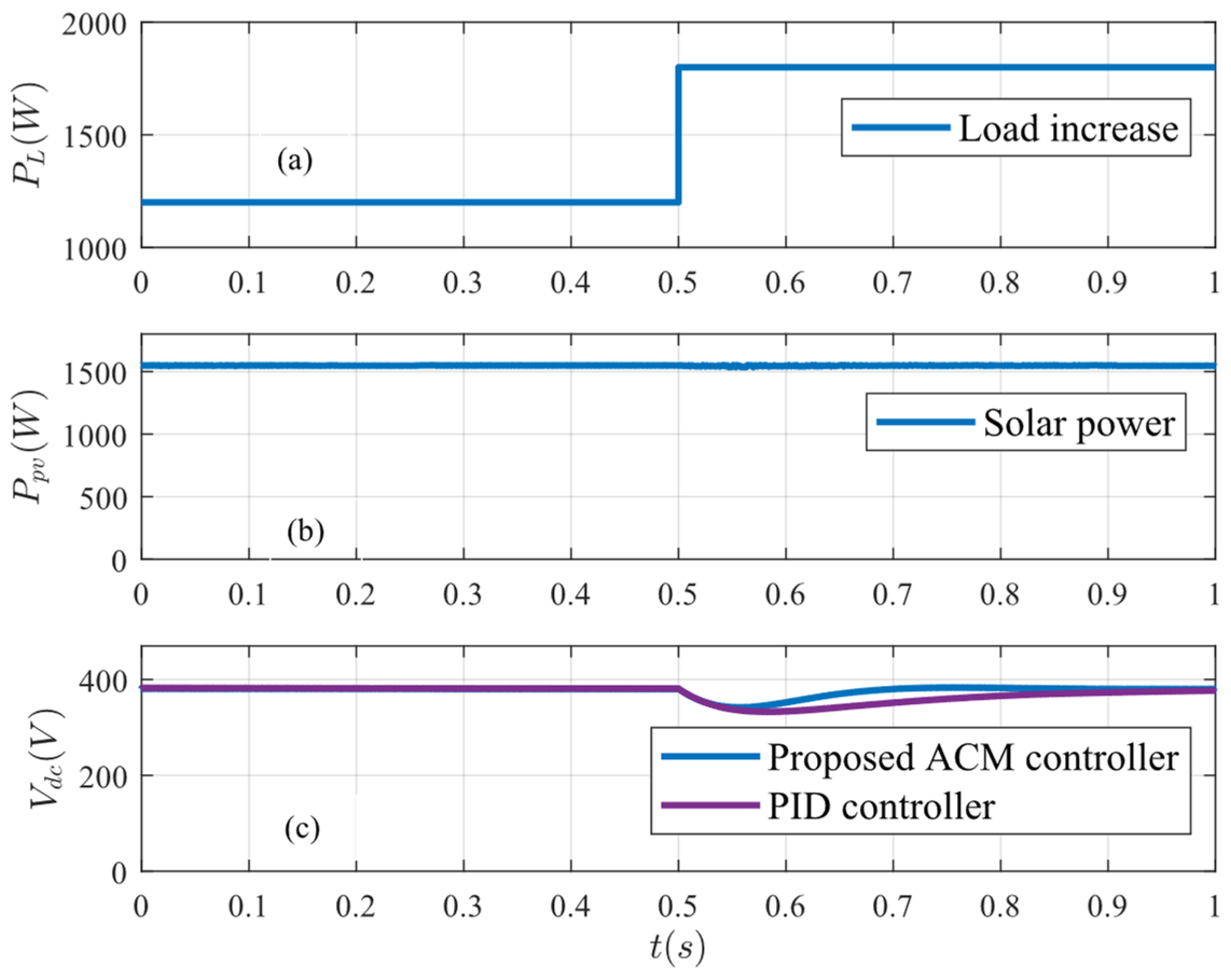

Figure 10a illustrates a scenario where the load increases by 30% at

t = 0.5 s, while PV power remains constant at 1.5 kW, as shown in

Figure 10b. Under these conditions, the proposed controller stabilises the DC bus voltage at 380 V within 0.12 s following the load variation, compared to 0.26 s with the conventional PID controller, as illustrated in

Figure 10c. Furthermore, this method limits DC bus voltage variations up to 0.2 V under steady-state condition, whereas the conventional method experiences variations up to 0.3 V. FFT analysis of the DC bus voltage reveals that the ACM-based cascaded control scheme offers superior power quality compared to the conventional PID-based scheme, with THD reducing from 0.04% to 0.03%.

Table 3 summarises the system performance under increasing load in terms of transient parameters, power quality, and numerical values of error tracking parameters. The proposed controller shows better error tracking performance than the PID controller.

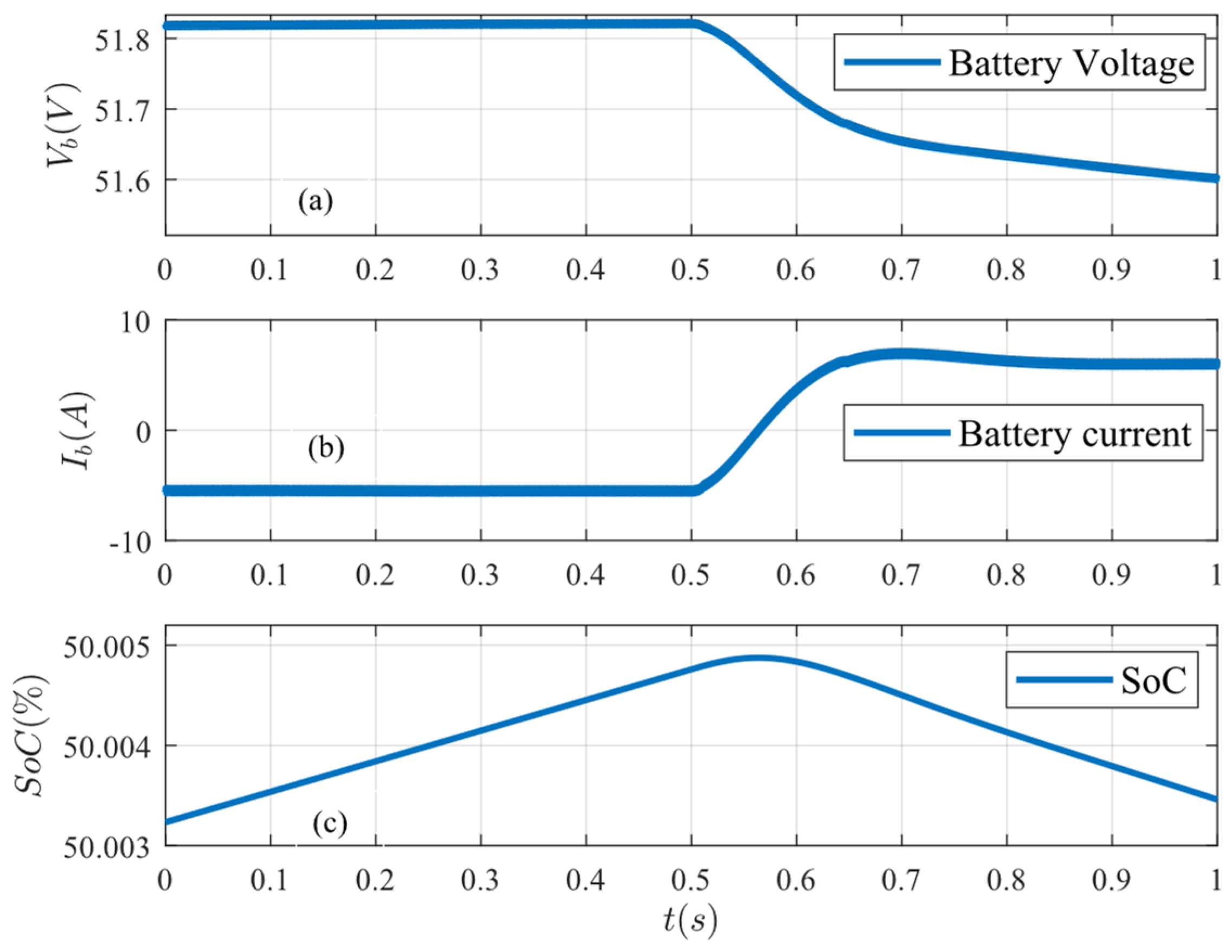

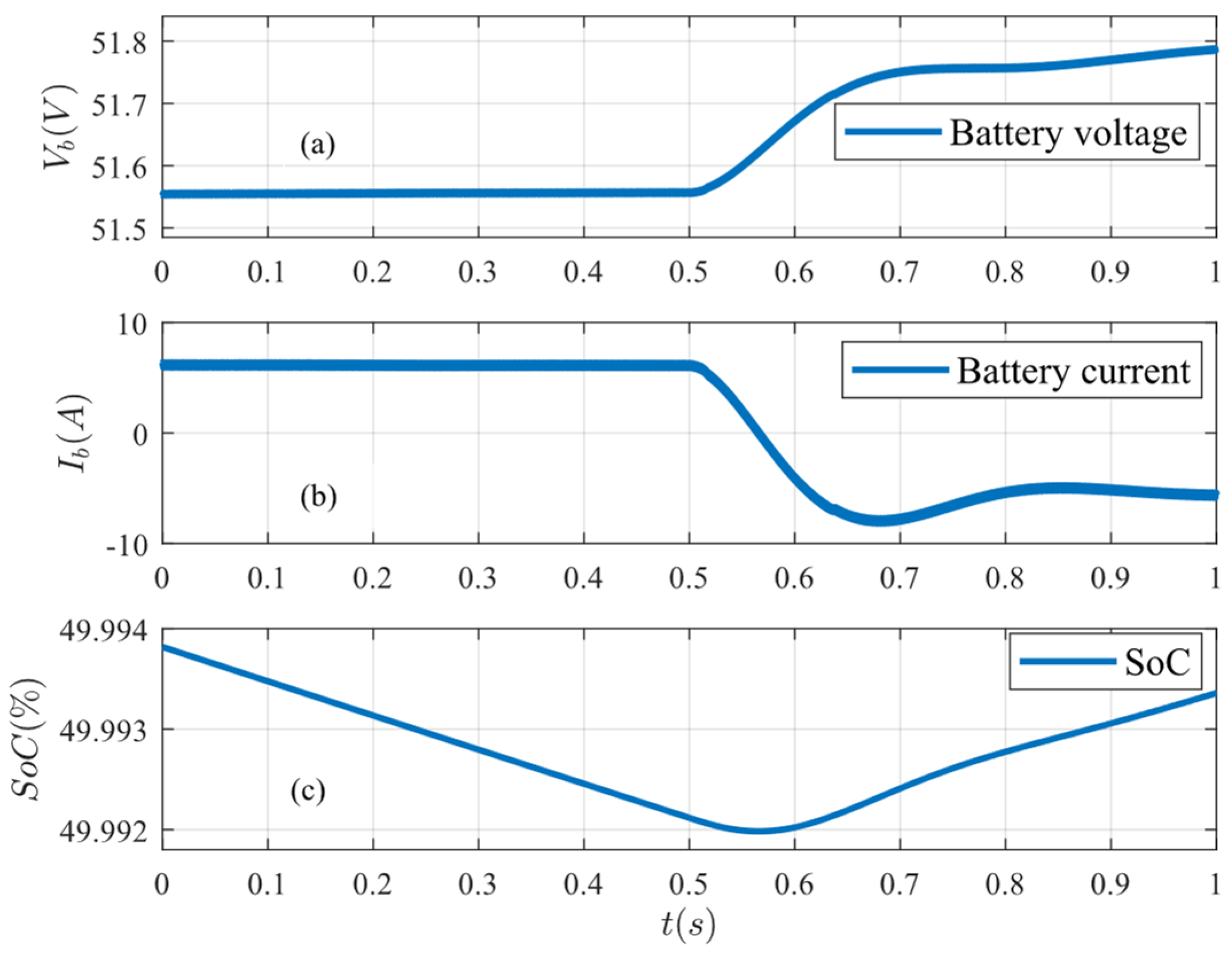

Figure 11 displays the voltage, current, and SoC of the battery as the load increases. Initially, the solar system generates more power than the load requires, allowing the battery to absorb excess power through charging. At

t = 0.5 s, the demand increases from 1.2 kW to 1.8 kW, prompting the battery to discharge and provide additional power to the load, thereby maintaining the balance between generation and demand. In this case, the battery voltage and current ripple are 0.005 V and 0.45 A, respectively, at the switching frequency.

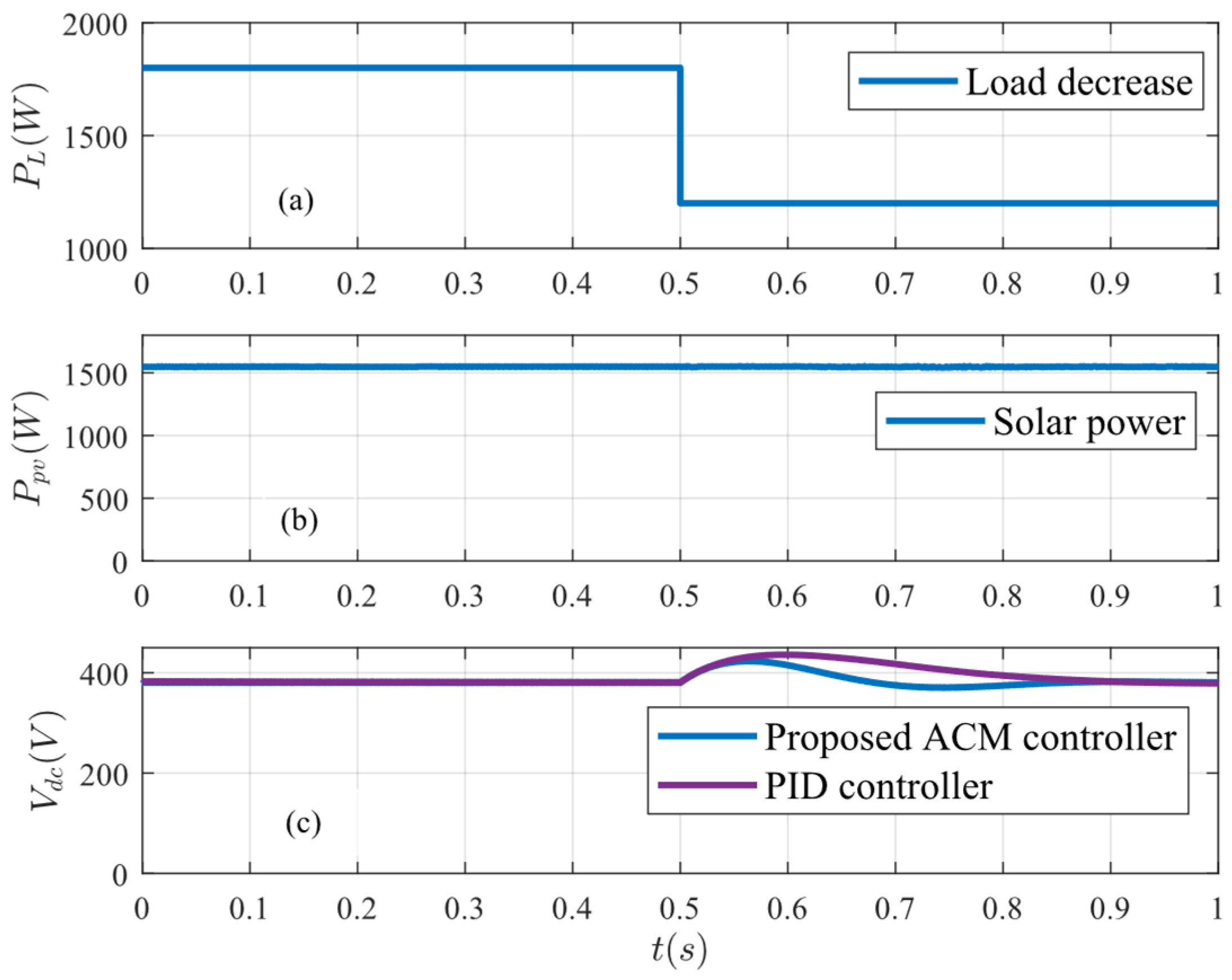

Conversely, when the load decreases at

t = 0.5 s, the system and battery responses are shown in

Figure 12 and

Figure 13, respectively. In this scenario, the DC bus voltage stabilises at the reference voltage within 0.13 s using the proposed controller, while the conventional PID controller takes 0.27 s to achieve stabilisation under decreasing load conditions. Initially, demand exceeds generation, causing the SoC to begin discharging until the load changes at

t = 0.5 s. After this point, the SoC starts to charge again to achieve a balanced condition between generation and demand.

5.2. Generation Variations

Changes in solar irradiance, which in turn affect PV power output, are implemented in order to assess the systems response to variations in generation. A constant load of 1.5 kW is maintained throughout the period where irradiance is varied.

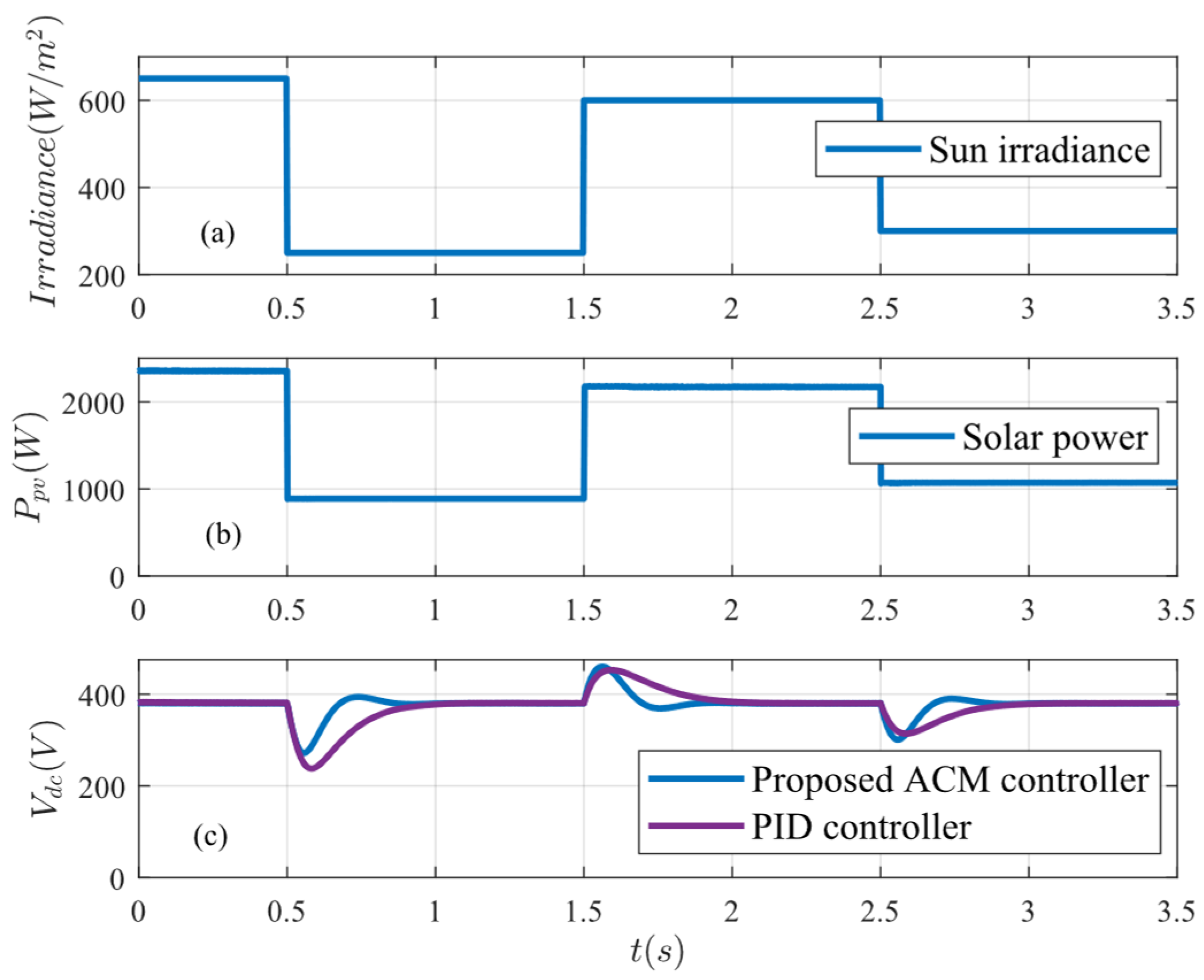

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 illustrate the impact of these variations on the DC bus voltage and the battery, respectively.

Solar irradiance was varied initially from 650 W/m

2 to 250 W/m

2 at

t = 0.5 s, then to 600 W/m

2 at

t = 1.5 s, and finally to 300 W/m

2 at

t = 2.5 s, as shown in

Figure 14a. Despite these fluctuations, the DC bus voltage remains stable and quickly settles at 380 V, as presented in

Figure 14c. Although changes in irradiance result in a large percentage overshoot, they do not affect the overall performance of the controller. The proposed controller settles the DC bus voltage after step-changes in solar irradiance, within 0.14 s at

t = 0.5 s, 0.16 s at

t = 1.5 s and 0.14 s at

t = 2.5 s. This outperforms the conventional approach, with settling time less than half that observed for PID control, at 0.34 s, 0.34 s and 0.28 s, respectively. In addition, ACM control ensures 0.05% voltage regulation on the DC bus under steady-state condition, compared to 0.08% with PID control. The ACM-based method also achieves a THD of 0.02%, significantly lower than for the conventional method at 0.05%.

Table 4 showcases a comparison among the proposed ACM and PI controllers, highlighting better performance of proposed controller in terms of speed, power quality, and error tracking ability.

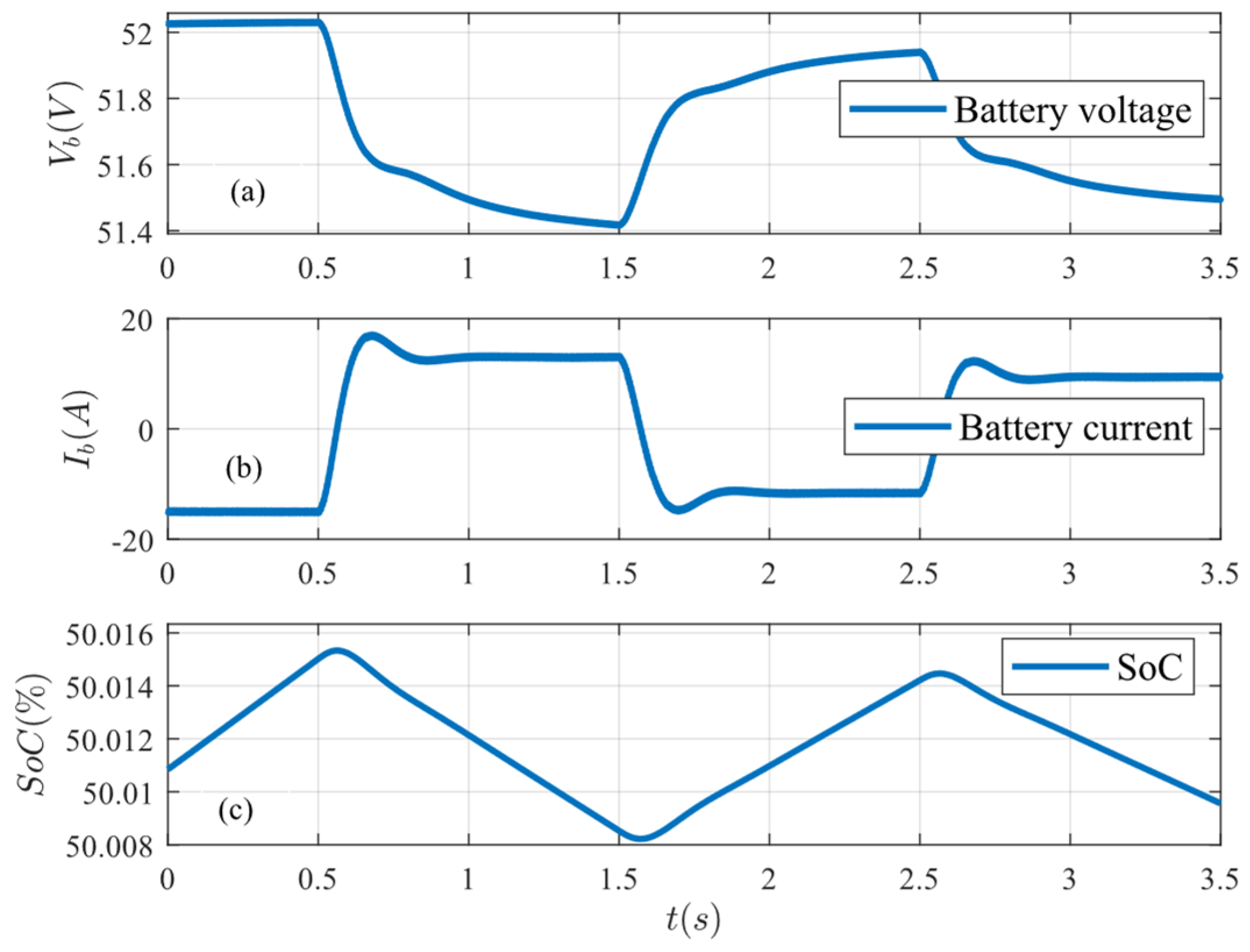

The battery’s SoC demonstrates adaptive behaviour to balance power generation and load demand, as shown in

Figure 15c. When solar irradiance drops at

t = 0.5 s, the battery switches from charging to discharging. At

t = 1.5 s, as irradiance increases, the battery starts to charge again because solar power is higher than demand. At

t = 2.5 s, with a decrease in irradiance from 500 W/m

2 to 300 W/m

2, the battery again starts discharging to achieve the balance condition between generation and demand. These dynamic responses confirm that the proposed controller consistently maintains the DC bus voltage effectively and quickly across all scenarios, offering superior power quality compared to conventional methods.

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis was employed to assess how changes in system parameters affect overall system performance.

5.3.1. System Loading

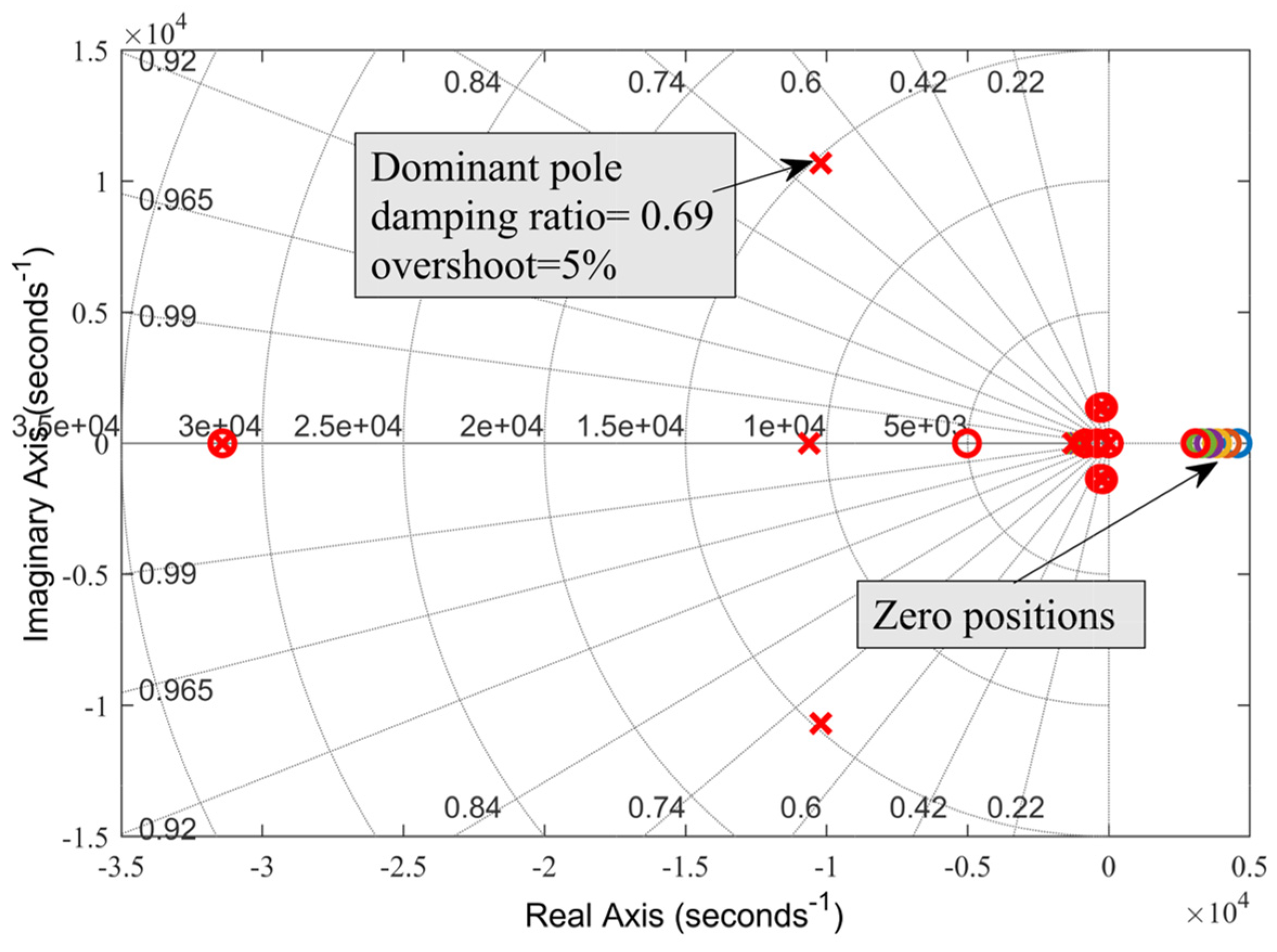

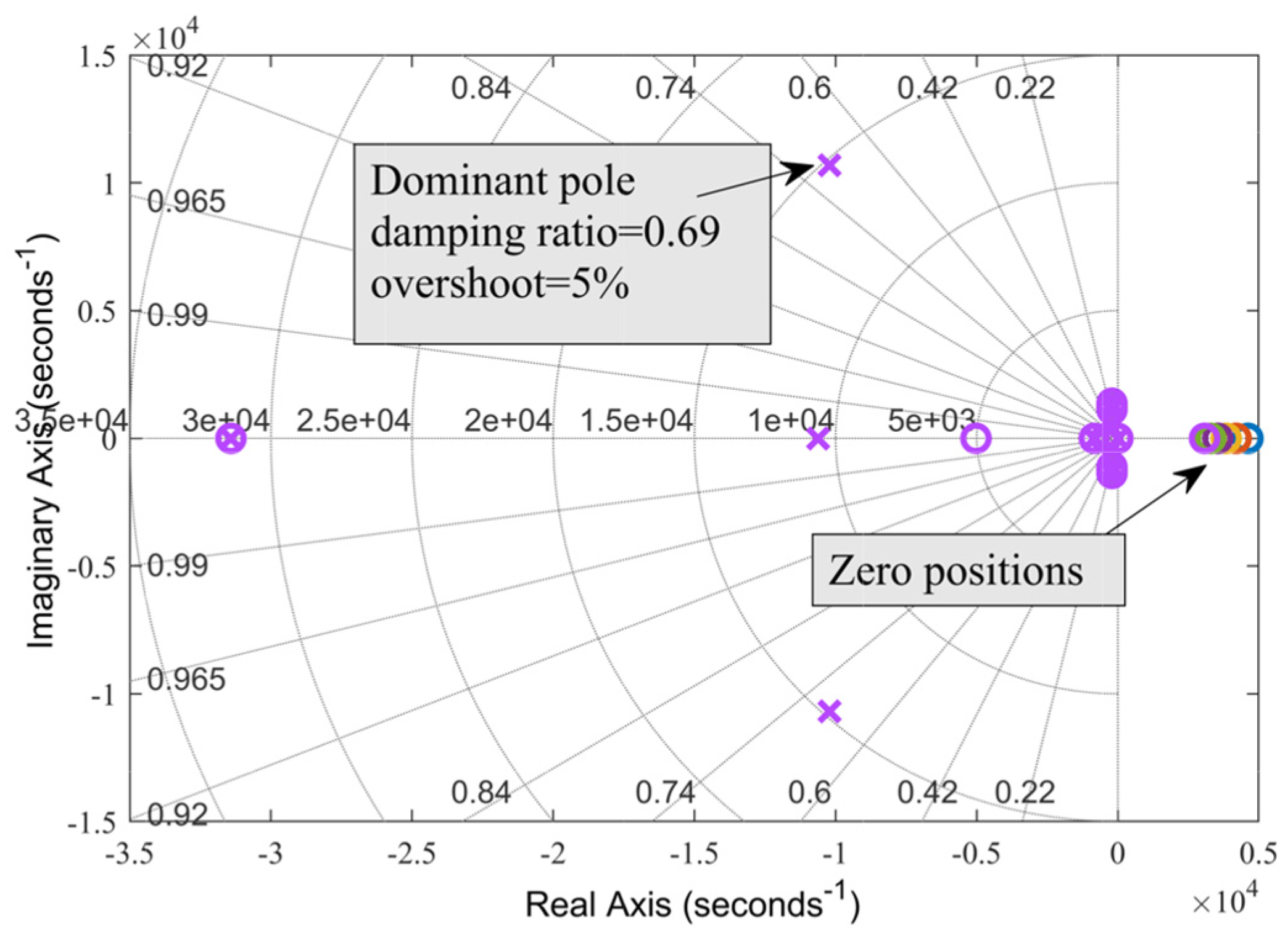

To observe the impact of system loading on the dominant poles of the DC MG, the system load was varied by 50% from the nominal power, keeping all parameters constant. The pole-zero locations of the entire system, illustrated in

Figure 16, reveal that despite these variations, the dominant pole positions remain constant. Although there is a shift in the zero positions, it does not affect the controller’s performance.

5.3.2. Converter Parameters

Figure 17 illustrates how variations in the bidirectional converter’s inductor (

L2) affect the system’s dominant poles. In this case,

L2 is increased from its reference value to 50%. The system’s pole-zero map indicates no impact on the dominant poles, suggesting that the system is less sensitive to inductor variations.

5. Conclusions

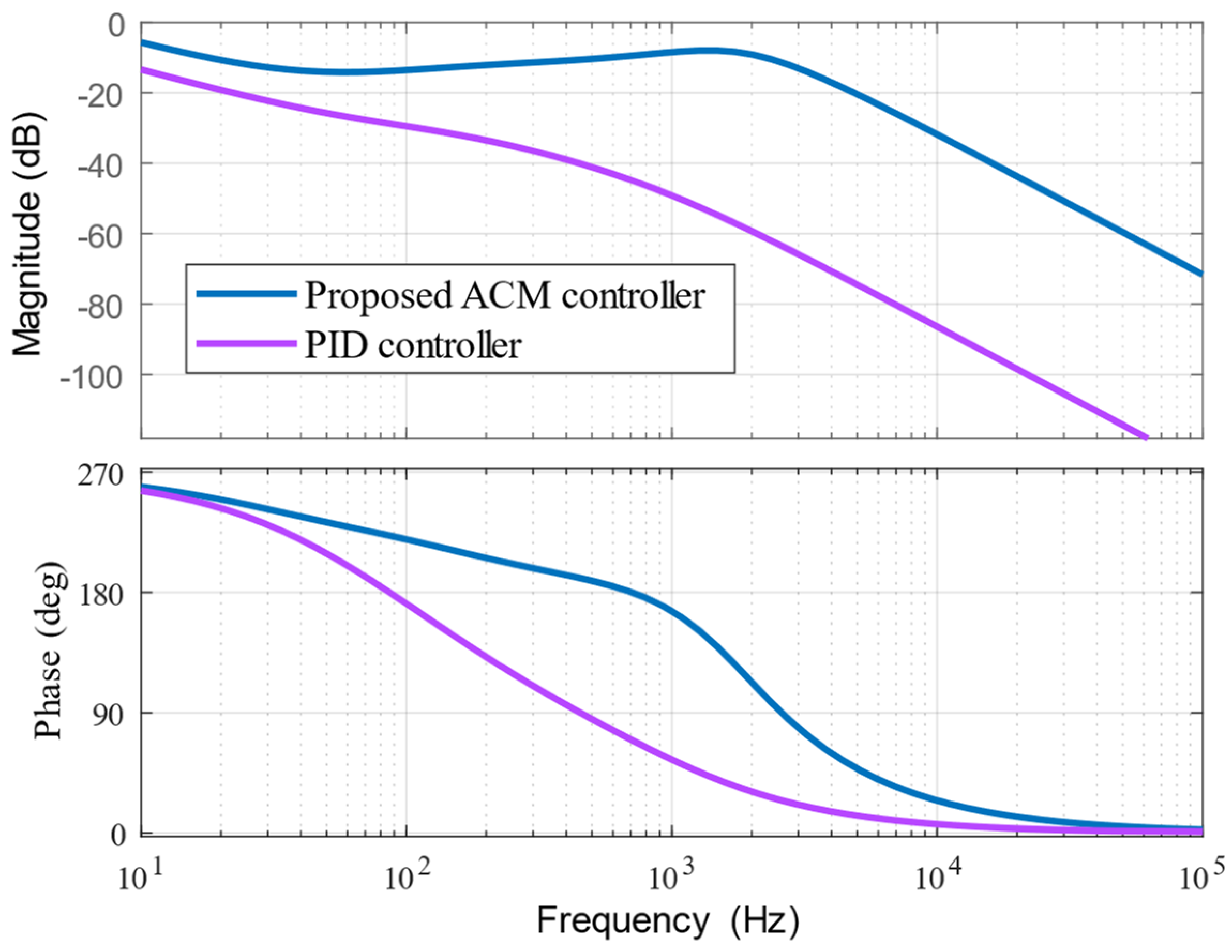

This paper proposes an ACM-based cascaded control approach for DC MGs and compares its performance with a conventional PID-based cascaded control scheme. A detailed mathematical and small-signal model of the proposed control approach is developed to evaluate system stability, determining performance metrics in terms of transient, frequency, and controller error performance parameters. Small-signal model analysis demonstrates that the proposed ACM-based cascaded control scheme offers significant improvements over the conventional PID-based control scheme. It achieves a smaller settling time of 117 ms, a higher phase margin of 84 degrees, and a higher bandwidth of 35 Hz, resulting in faster transient responses and satisfactory frequency metrics. In addition, it offers superior power quality and voltage regulation compared to the conventional scheme, with better error tracking performance. The effectiveness of the ACM-based cascaded controller is validated through EMT simulation, accounting for variations in load demands and generation. When subjected to load changes, the DC bus voltage stabilises within 0.12 s using the proposed control scheme, compared to 0.26 s with the conventional control scheme. Both small-signal and EMT results indicate that the proposed method performs satisfactorily under normal operating conditions and after small-signal disturbances. Sensitivity analysis further reveals that the proposed control scheme’s dominant poles are less affected by load and converter parameter variations.

The proposed ACM-based cascaded control system designed for DC MGs offers a versatile solution addressing small-signal disturbances. Its ability to manage varying load and generation profiles ensures reliability and sustainability in isolated settings, making it suitable for remote communities and offshore industries seeking to replace conventional diesel generation with integration of DRESs. Implementation of this approach in remote and offshore applications offers the potential for enhanced energy efficiency, lower emissions, reduced operational costs, and increased resilience against power disruptions. Future research should investigate the scalability of such DG MGs, the integration of emerging technologies, and the optimisation of energy management in these applications.

Figure 1.

A model of a DC MG structure suitable for offshore settings.

Figure 1.

A model of a DC MG structure suitable for offshore settings.

Figure 2.

Simulation model of proposed DC MG.

Figure 2.

Simulation model of proposed DC MG.

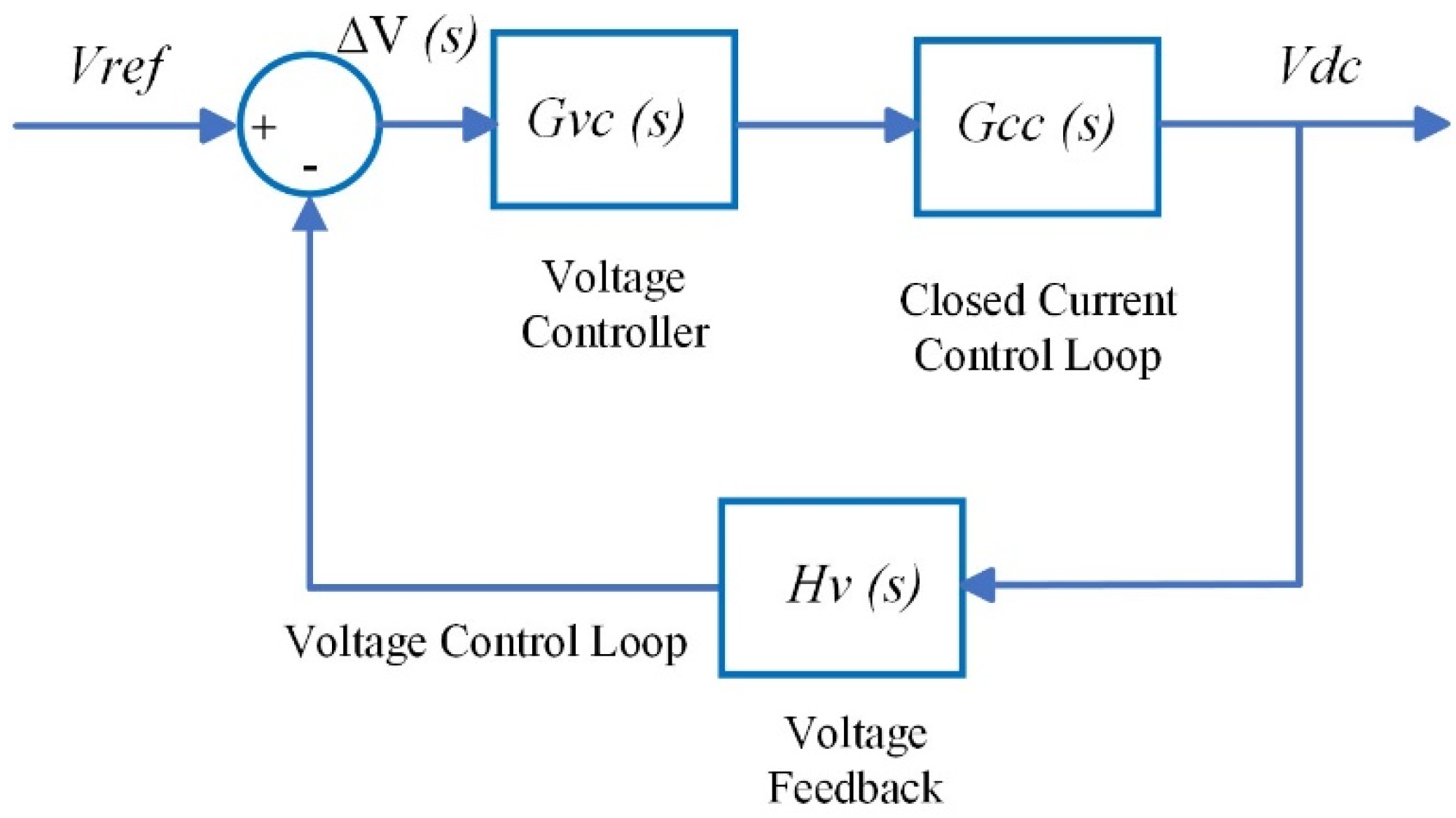

Figure 3.

Cascaded control structure for DC-DC bidirectional converter.

Figure 3.

Cascaded control structure for DC-DC bidirectional converter.

Figure 4.

Modified cascaded control structure.

Figure 4.

Modified cascaded control structure.

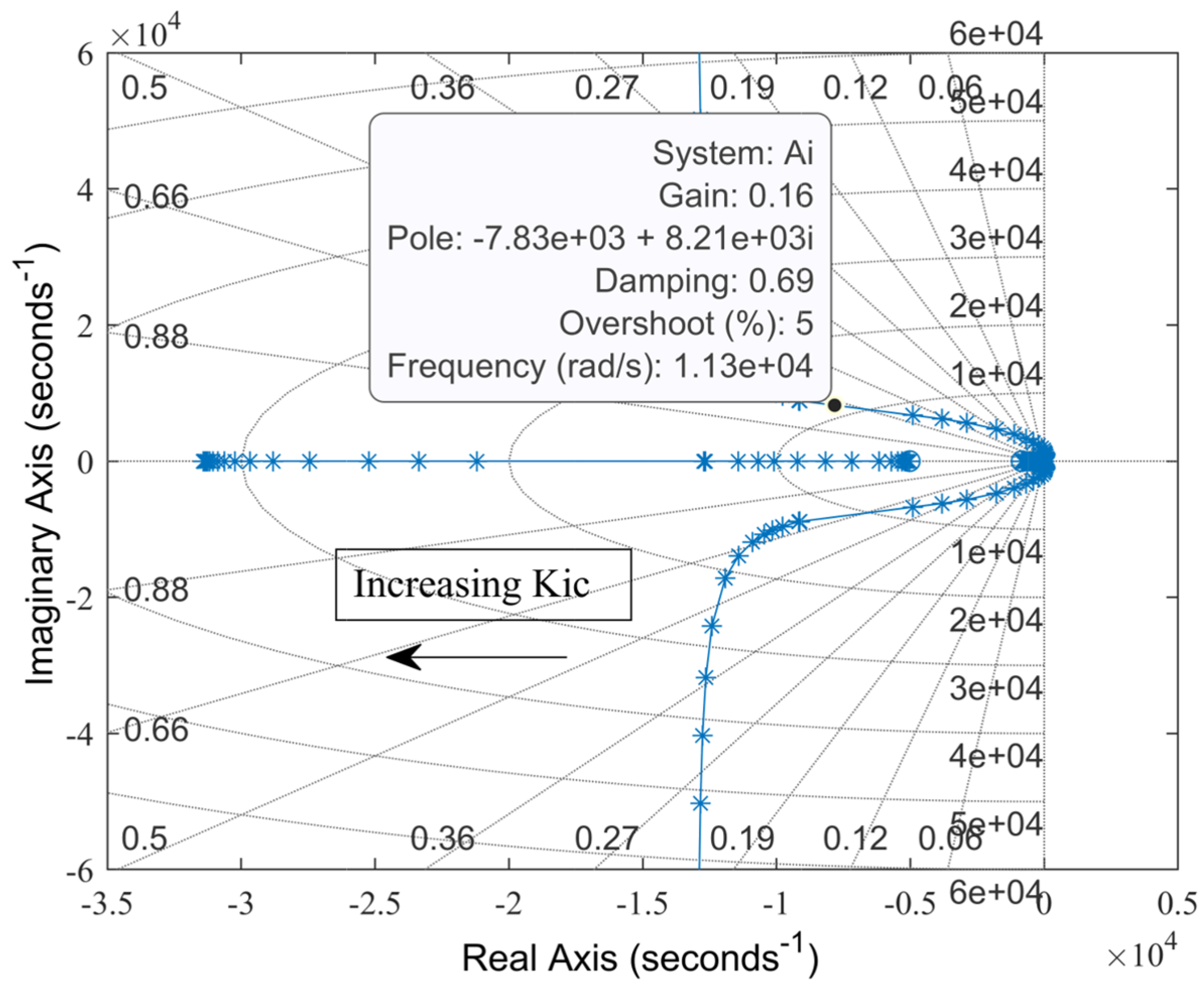

Figure 5.

Root locus for varying current controller gain, Kic.

Figure 5.

Root locus for varying current controller gain, Kic.

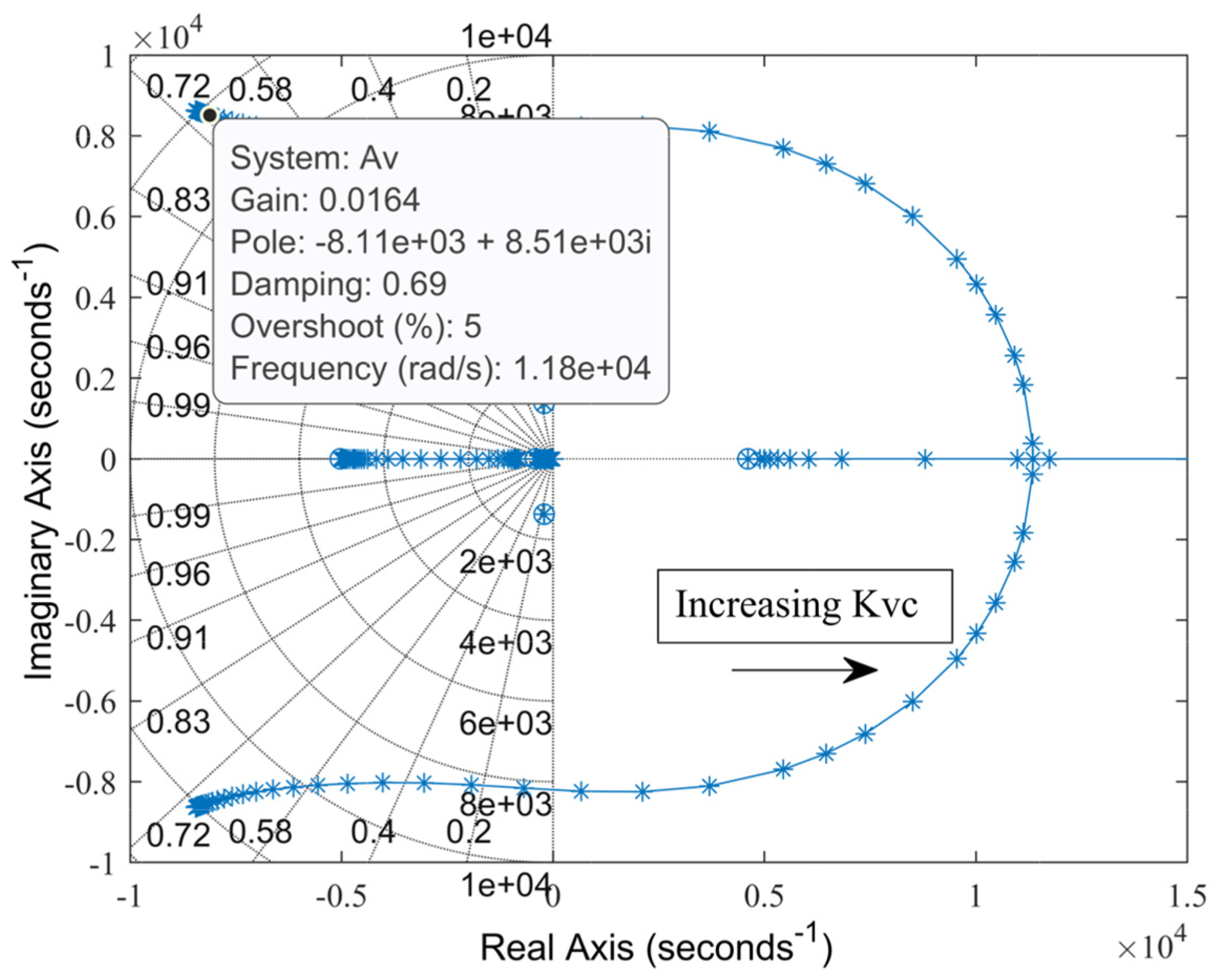

Figure 6.

Root locus for varying voltage controller gain, Kvc.

Figure 6.

Root locus for varying voltage controller gain, Kvc.

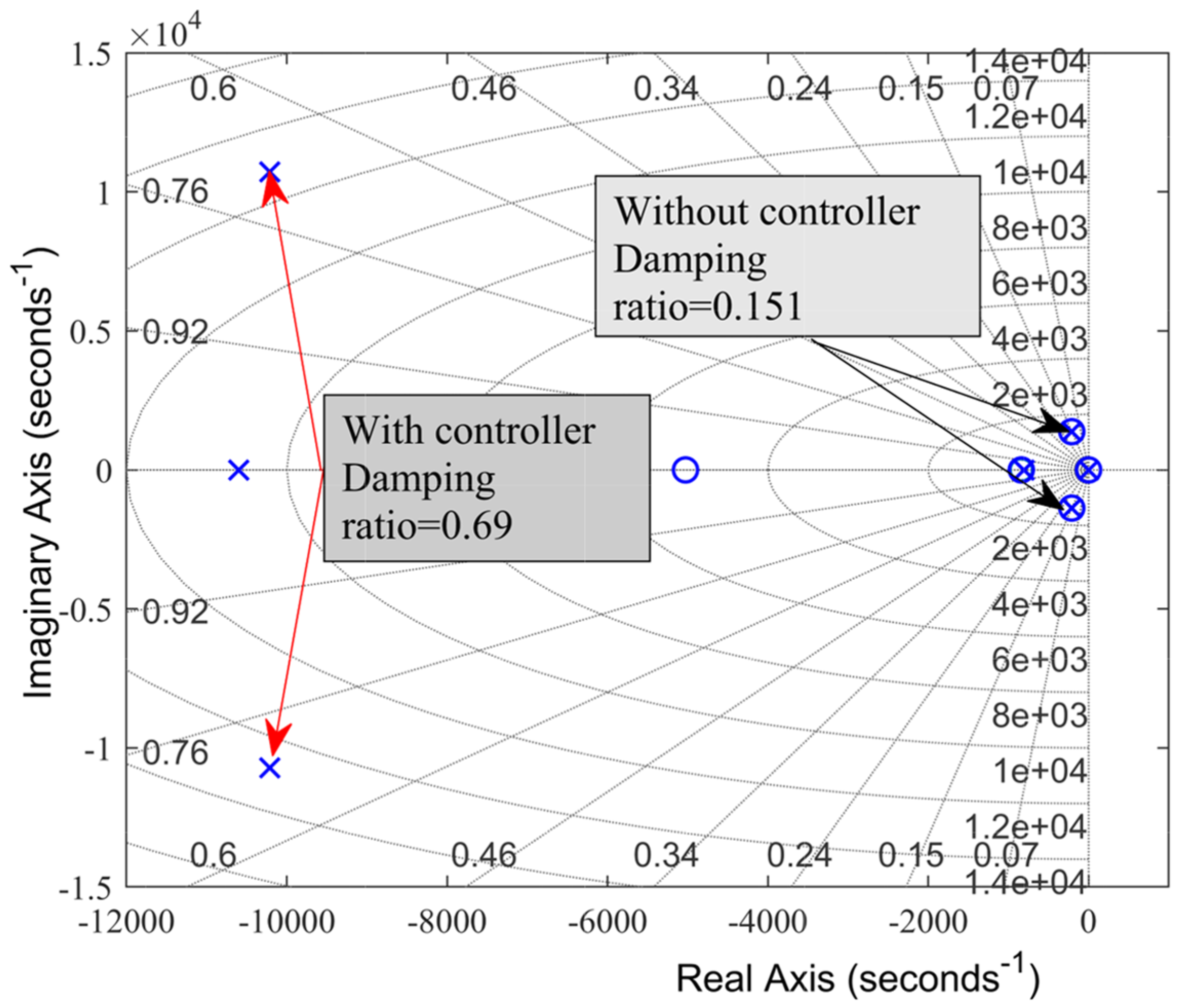

Figure 7.

Locations of dominant poles.

Figure 7.

Locations of dominant poles.

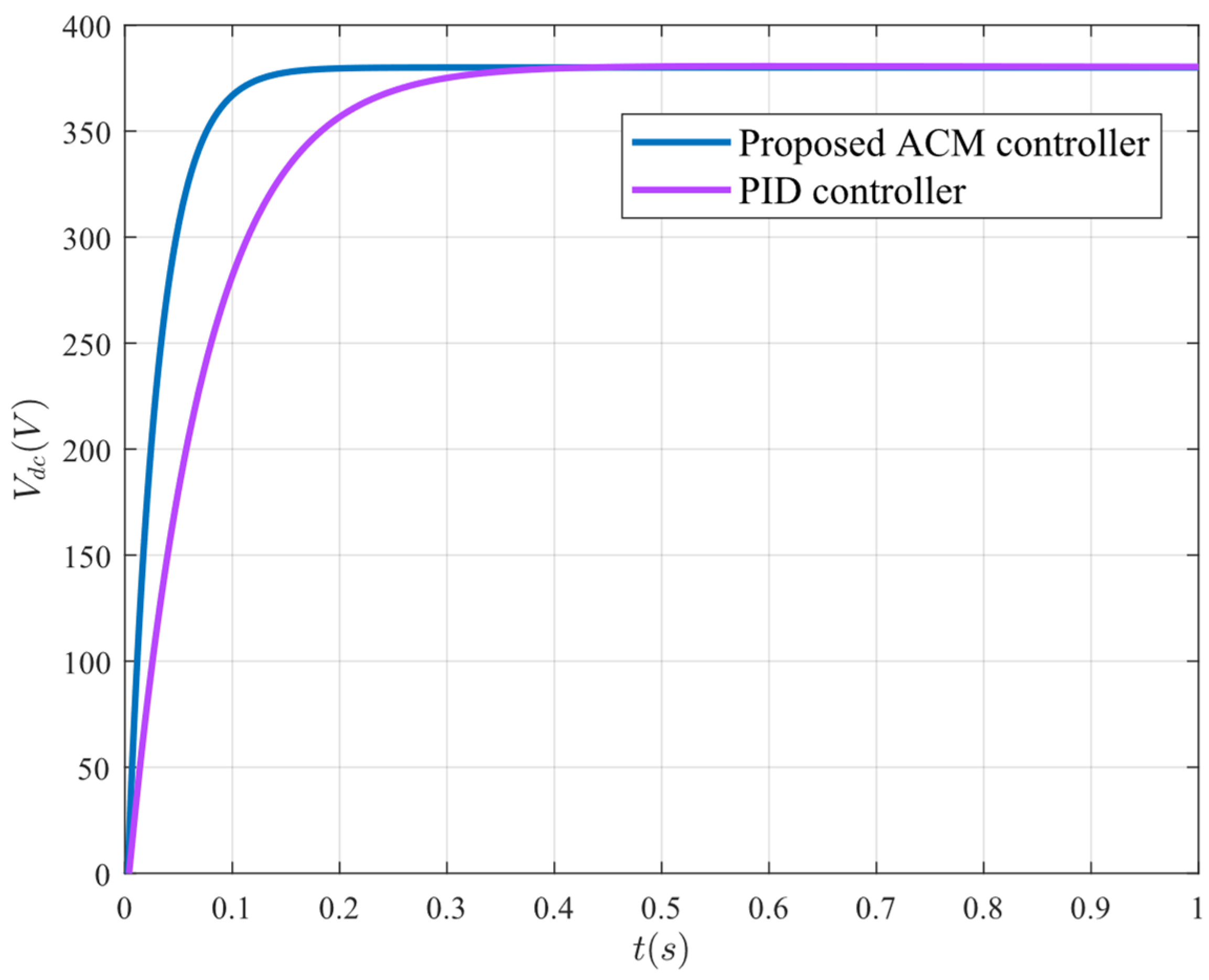

Figure 8.

Transient response comparison between ACM and PID controller.

Figure 8.

Transient response comparison between ACM and PID controller.

Figure 9.

Frequency response comparison between ACM and PID controller.

Figure 9.

Frequency response comparison between ACM and PID controller.

Figure 10.

System response under load increase: (a) load power, (b) PV power, and (c) bus voltage.

Figure 10.

System response under load increase: (a) load power, (b) PV power, and (c) bus voltage.

Figure 11.

Battery conditions under load increase: (a) battery voltage, (b) battery current, and (c) battery SoC.

Figure 11.

Battery conditions under load increase: (a) battery voltage, (b) battery current, and (c) battery SoC.

Figure 12.

System response under load decrease: (a) load power, (b) PV power, and (c) bus voltage.

Figure 12.

System response under load decrease: (a) load power, (b) PV power, and (c) bus voltage.

Figure 13.

Battery conditions under load decrease: (a) battery voltage, (b) battery current, and (c) battery SoC.

Figure 13.

Battery conditions under load decrease: (a) battery voltage, (b) battery current, and (c) battery SoC.

Figure 14.

System response under generation variations: (a) solar irradiance, (b) PV power, and (c) bus voltage.

Figure 14.

System response under generation variations: (a) solar irradiance, (b) PV power, and (c) bus voltage.

Figure 15.

Battery conditions under generation variations: (a) battery voltage, (b) battery current, and (c) battery SoC.

Figure 15.

Battery conditions under generation variations: (a) battery voltage, (b) battery current, and (c) battery SoC.

Figure 16.

Effect of the dominant pole due to load variations.

Figure 16.

Effect of the dominant pole due to load variations.

Figure 17.

Effect of the dominant pole due to inductance variations.

Figure 17.

Effect of the dominant pole due to inductance variations.

Table 1.

System performance specifications.

Table 1.

System performance specifications.

| Performance specification |

Value |

| PID controller |

Proposed ACM controller |

| Rise time (ms) |

155 |

63 |

| Settling time (ms) |

274 |

117 |

| Phase margin (degree) |

86 |

84 |

| Gain margin (dB) |

28 |

10 |

| Bandwidth (Hz) |

14 |

35 |

Table 2.

System parameters.

Table 2.

System parameters.

| Parameter |

Value |

| Load power and DC bus voltage |

2 kW and 380 V |

| Battery capacity and terminal voltage |

50 Ah and 48 V |

| PV power |

1.5 kW |

| Inductance, L1, L2

|

470 µH and 5 mH |

| Capacitance, C1, C2

|

1000 µF and 33 µF |

| Switching frequency |

20 kHz |

| Target crossover frequency for current loop compensator |

2 kHz |

| Target crossover frequency for voltage loop compensator |

0.2 kHz |

| Current and voltage feedback gain, Hi, Hv

|

1 and 1 |

Table 3.

System performance specifications under load variation.

Table 3.

System performance specifications under load variation.

| Performance specification |

Value |

| PID controller |

Proposed ACM controller |

| Settling time (ms) |

260 |

120 |

| Voltage regulation (%) |

0.08 |

0.05 |

| THD (%) |

0.04 |

0.03 |

| IAE |

48.01 |

22.48 |

| ITAE |

35.94 |

7.9 |

Table 4.

System performance specifications under generation variation.

Table 4.

System performance specifications under generation variation.

| Performance specification |

Value |

| PID controller |

Proposed ACM controller |

| Settling time (ms) |

340 |

140 |

| Voltage regulation (%) |

0.08 |

0.05 |

| THD (%) |

0.05 |

0.02 |

| IAE |

109.87 |

37.05 |

| ITAE |

241.2 |

59.79 |