Submitted:

09 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

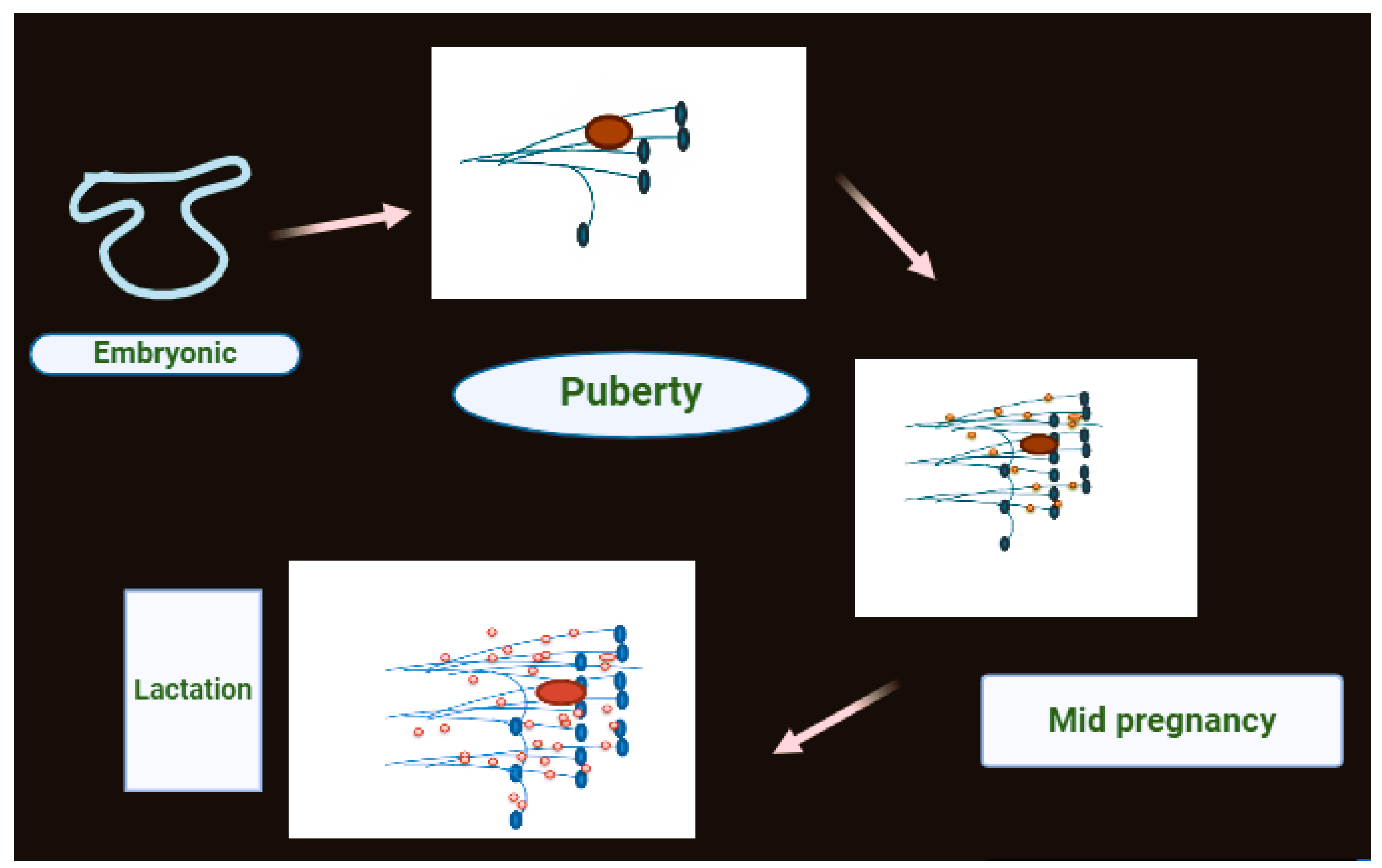

1.1. Structure of Breast

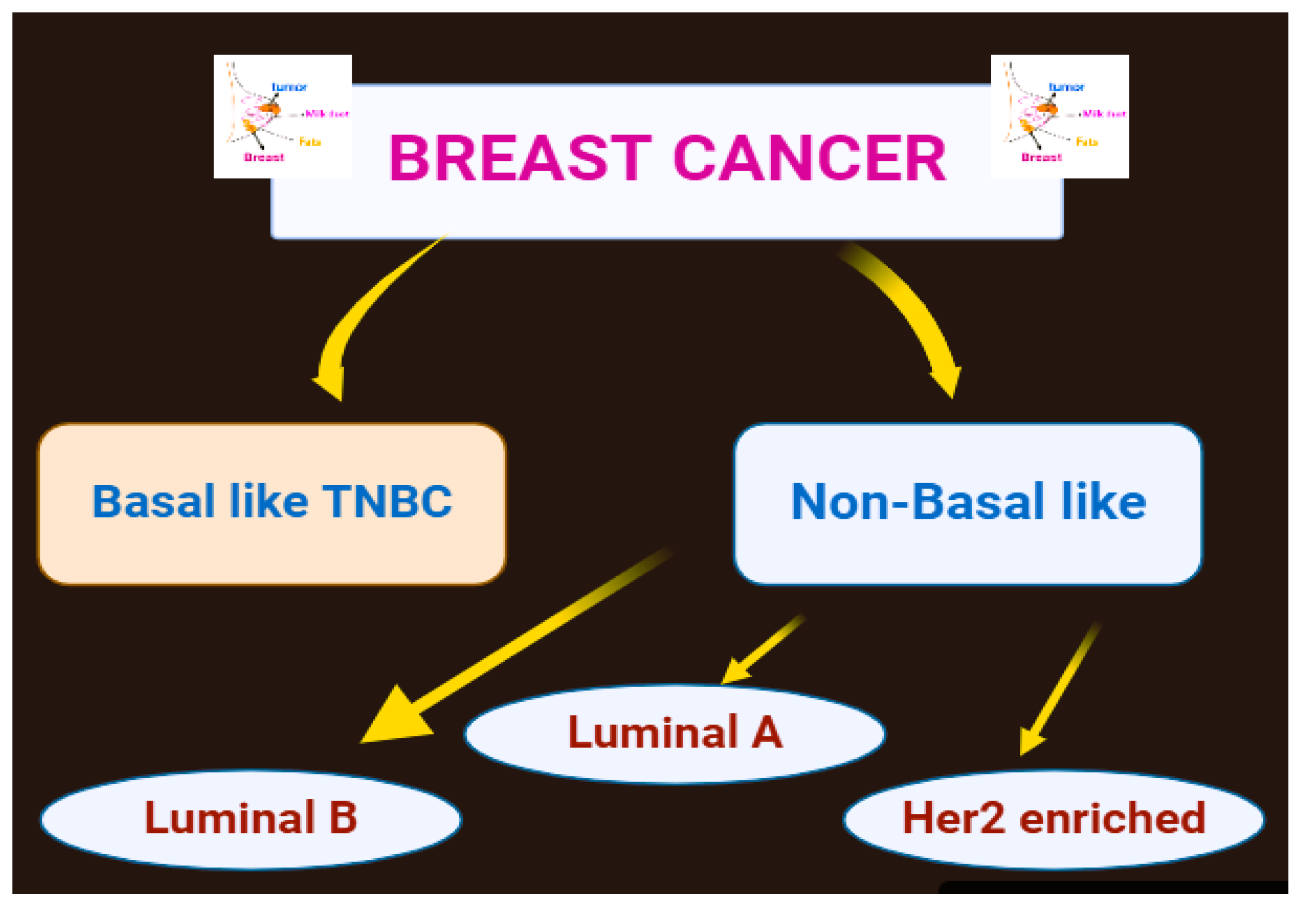

1.2. Kinds of Breast Tumors

1.3. Death Rate Due to Breast Cancer

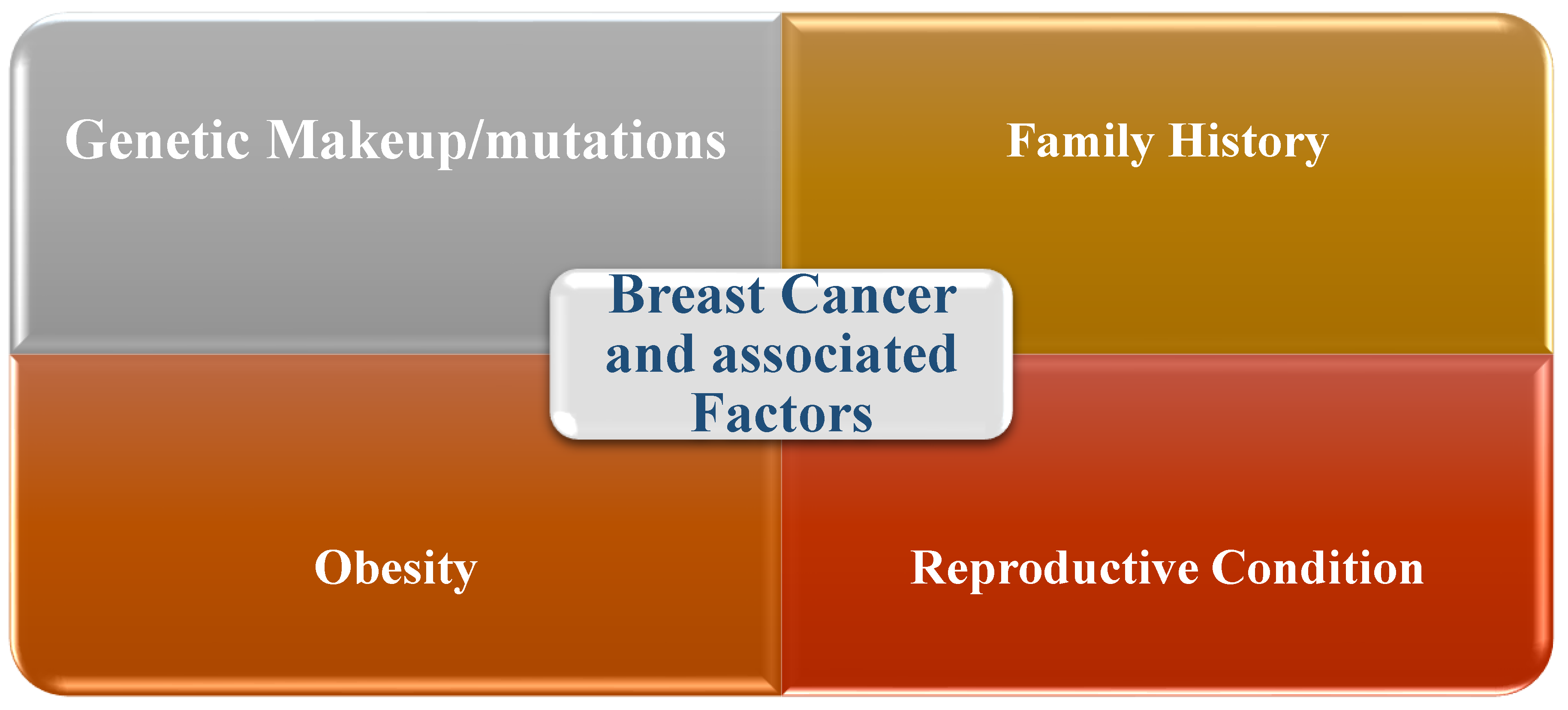

1.4. Risk Factors Associated with Breast Cancer

- Introductory evaluation and screening

- Late determination

- Financial and racial incongruities

- Hereditary and biological variables

1.5. Treatment Approaches for Breast Cancer

Breast Cancer Overview

3. Symptoms and Clinical Manifestations of Breast Cancer

4. Breast Cancer and Physical Activities

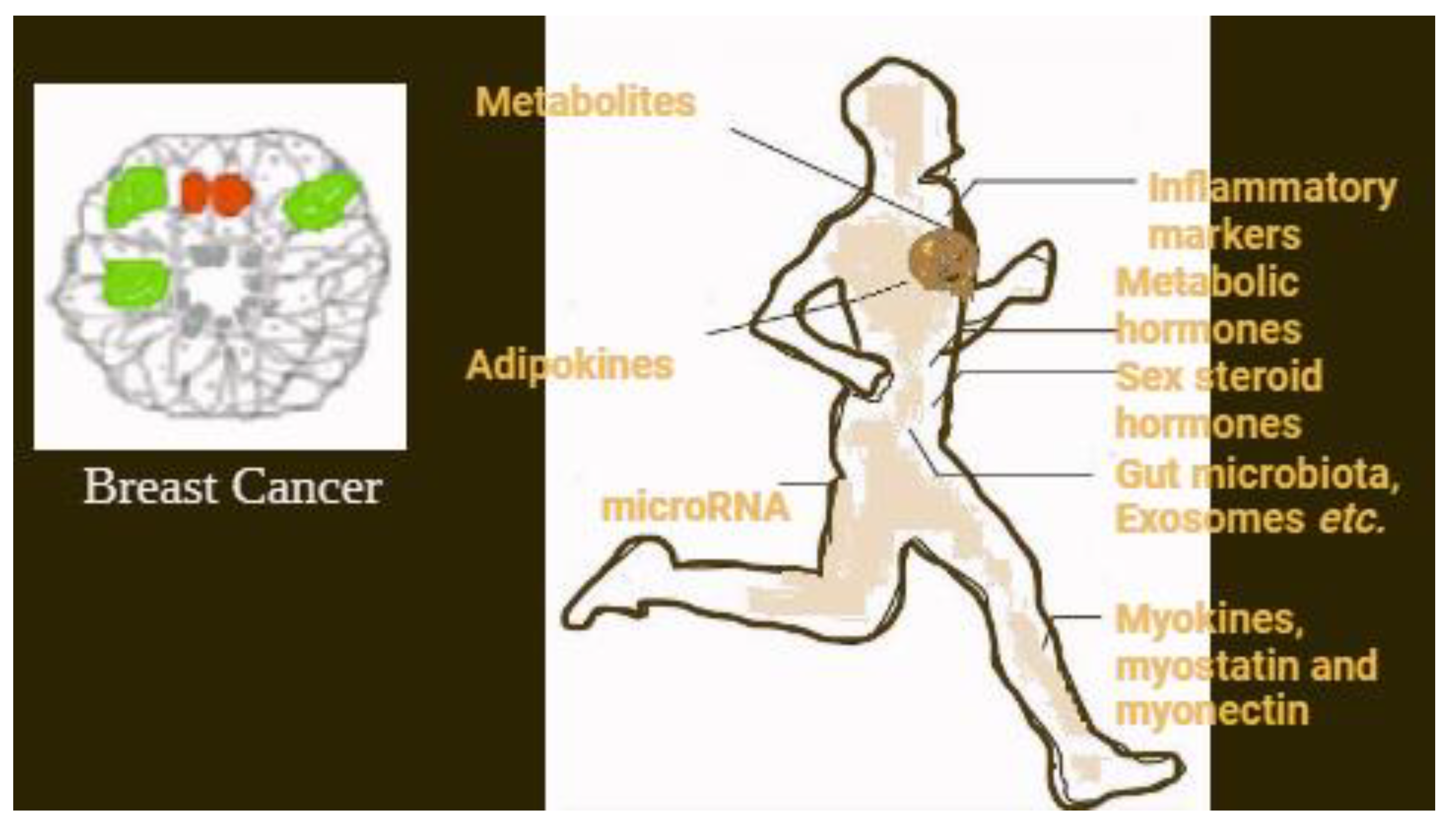

5. The Natural Components Connecting Physical Movement and Breast Cancer

6. Discussion

7. Conclusion

Future Perspective:

References

- Arnold, M.; Morgan, E.; Rumgay, H.; Mafra, A.; Singh, D.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I. Current and future burden of breast cancer: Global statistics for 2020 and 2040. The Breast. 2022, 66, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattiuzzi, C.; Lippi, G. Current cancer epidemiology. Journal of epidemiology and global health. 2019, 9, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.Y.; Park, JY. Epidemiology of Cancer. In Anesthesia for Oncological Surgery. Cham: Springer International Publishing 2024, 11-16.

- Giaquinto, AN.; Sung, H.; Miller, KD.; Kramer, JL.; Newman, LA.; Minihan, A.; Siegel, RL. Breast cancer statistics, 2022. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2022, 72, 524–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaquinto, AN.; Sung, H.; Newman, LA.; Freedman, RA.; Smith, RA.; Star, J.; Siegel, RL. Breast cancer statistics 2024. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2024, 74, 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali-Gombe, M.; Mustapha, MI.; Folasire, A.; Ntekim, A. , Campbell, OB. Pattern of survival of breast cancer patients in a tertiary hospital in South West Nigeria. Ecancermedicalscience. 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilic, L.; Simon, J.; Hackl, M.; Haidinger, G. Time Trends in Male Breast Cancer Incidence, Mortality, and Survival in Austria (1983–2017). Clinical Epidemiology. 2024, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Hao, X.; Song, Z.; Zhi, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J. Correlation between family history and characteristics of breast cancer. Scientific reports. 2021, 11, 6360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, A.; Johnstone, KJ.; McCart Reed, AE.; Simpson, PT.; Lakhani, SR. Hereditary breast cancer: syndromes, tumour pathology and molecular testing. Histopathology. 2023, 82, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, R.; Xu, B. Breast cancer: an up-to-date review and future perspectives. Cancer communications. 2022, 42, 913–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhri, N.; Chad, MA.; Lahkim, M.; Houari, A.; Dehbi, H.; Belmouden, A.; El Kadmiri, N. Risk factors for breast cancer in women: an update review. Medical Oncology. 2022, 39, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zou, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; Ke, F.; Zhang, Y. Prediction of BRCA gene mutation in breast cancer based on deep learning and histopathology images. Frontiers in Genetics. 2021, 12, 661109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, SK.; Banerjee, S.; Baker, GW.; Kuo, CY.; Chowdhury, I. (2022). The mammary gland: basic structure and molecular signaling during development. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022, 23, 3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, T.; Gama, A.; Seixas, F.; Faustino-Rocha, AI.; Lopes, C.; Gaspar, VM.; Oliveira, PA. Mammary glands of women, female dogs and female rats: similarities and differences to be considered in breast cancer research. Veterinary Sciences. 2023, 10, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V. Age related histomorphological and histochemical studies on mammary gland of goat (Doctoral dissertation, Guru Angad Dev Veterinary and Animal Sciences University), 2022.

- Josefson, C. C.; Orr, TJ.; Hood, WR.; Skibiel, AL. Hormones and lactation in mammals. In Hormones and Reproduction of Vertebrates. 2024, 137–167. [Google Scholar]

- Ingthorsson, S.; Traustadottir, GA.; Gudjonsson, T. Breast Morphogenesis: From Normal Development to Cancer. A Guide to Breast Cancer Research: From Cellular Heterogeneity and Molecular Mechanisms to Therapy.

- Gomes, PRL. ; Motta-Teixeira, LC.; Gallo, CC.; do Carmo Buonfiglio, D.; de Camargo, LS.; Quintela, T.; Cipolla-Neto, J. Maternal pineal melatonin in gestation and lactation physiology, and in fetal development and programming. General and comparative endocrinology. 2021, 300, 113633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, RA. Physiology of lactation. In Breastfeeding. 2022, 58–92. [Google Scholar]

- Agre, AM.; Upade, AC.; Yadav, MA.; Kumbhar, SB. A Review on Breasr Cancer and Its Management. World J. Pharm. Res. 2021, 10, 408–437. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, AA. Benign breast disorders in female. Revista de Senología y Patología Mamaria. 2022, 35, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Goyal, N. Applied anatomy of breast cancer. In Breast Cancer: Comprehensive Management. 2022, 23-35.

- Briem, E.; Ingthorsson, S.; Traustadottir, GA.; Hilmarsdottir, B.; Gudjonsson, T. Application of the D492 cell lines to explore breast morphogenesis, EMT and cancer progression in 3D culture. Journal of mammary gland biology and neoplasia, 2019, 24, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beňačka, R.; Szabóová, D.; Guľašová, Z.; Hertelyová, Z.; Radoňák, J. Classic and new markers in diagnostics and classification of breast cancer. Cancers. 2022, 14, 5444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, R.; Swedlund, B.; Ganesan, AK.; Morsut, L.; Maini, PK.; Monuki, ES.; Plikus, MV. Parsing patterns: Emerging roles of tissue self-organization in health and disease. Cell. 2024, 187, 3165–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sosinsky, AZ.; Rich-Edwards, JW.; Wiley, A.; Wright, K.; Spagnolo, PA.; Joffe, H. Enrollment of female participants in United States drug and device phase 1–3 clinical trials between 2016 and 2019. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2022, 115, 106718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Yan, Y.; Guo, Z.; Hou, H.; Garcia, M.; Tan, X.; Suboptimal Health Study Consortium and European Association for Predictive, Preventive and Personalised Medicine. All around suboptimal health—a joint position paper of the Suboptimal Health Study Consortium and European Association for Predictive, Preventive and Personalised Medicine. EPMA Journal. 2021, 12, 403–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, JM.; O'Neill, RM.; Juster, RP.; Irgens, MS. Dimensions of diversity and influences on health disparities. In APA handbook of health psychology, Volume 1: Foundations and context of health psychology. 2025, 51-70.

- Huang, J.; Chan, PS.; Lok, V.; Chen, X.; Ding, H.; Jin, Y.; Wong, MC. Global incidence and mortality of breast cancer: a trend analysis. Aging (Albany NY). 2021, 13, 5748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.; Zheng, R.; Zhang, S.; Wang, S.; Chen, R.; Sun, K.; Wei, W. Global patterns of breast cancer incidence and mortality: A population-based cancer registry data analysis from 2000 to 2020. Cancer Communications. 2021, 41, 1183–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, L.; Gathani, T. Understanding breast cancer as a global health concern. The British journal of radiology. 2022, 95, 20211033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, SM.; Kehm, RD.; Terry, MB. Global breast cancer incidence and mortality trends by region, age-groups, and fertility patterns. EClinicalMedicine. 2021, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopik, V. International variation in breast cancer incidence and mortality in young women. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2021, 186, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Jin, Z.; Bao, L.; Shu, P. The global burden of breast cancer in women from 1990 to 2030: assessment and projection based on the global burden of disease study 2019. Frontiers in Oncology. 2024, 14, 1364397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Planning for tomorrow: global cancer incidence and the role of prevention 2020–2070. Nature reviews Clinical oncology. 2021, 18, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, JDB. ; Morgan, E.; de Luna Aguilar, A.; Mafra, A.; Shah, R.; Giusti, F.; Soerjomataram, I. Global stage distribution of breast cancer at diagnosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA oncology. 2024, 10, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duggan, C.; Trapani, D.; Ilbawi, AM.; Fidarova, E.; Laversanne, M.; Curigliano, G.; Anderson, BO. National health system characteristics, breast cancer stage at diagnosis, and breast cancer mortality: a population-based analysis. The Lancet Oncology. 2021, 22, 1632–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thandra, KC.; Barsouk, A.; Saginala, K.; Aluru, JS.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of lung cancer. Contemporary Oncology/Współczesna Onkologia. 2021, 25, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanoue, LT. Women and lung cancer. Clinics in Chest Medicine. 2021, 42, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtyla, C.; Bertuccio, P.; Wojtyla, A.; La Vecchia, C. European trends in breast cancer mortality, 1980–2017 and predictions to 2025. European Journal of Cancer. 2021, 152, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, MC.; Guerra, MR.; Bustamante-Teixeira, MT.; e Silva, GA.; Tomazelli, J.; Pereira, DDA. ; Malta, DC. Mortality due to cervical and breast cancer in health regions of Brazil: impact of public policies on cancer care. Public Health. 2024, 236, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, RL.; Kratzer, TB.; Giaquinto, AN.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians.

- Siegel, RL.; Miller, KD.; Wagle, NS.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaquinto, AN.; Miller, KD.; Tossas, KY.; Winn, RA.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, RL. Cancer statistics for African American/black people 2022. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2022, 72, 202–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, T.; Karn, T.; Rozenblit, M.; Foldi, J.; Marczyk, M.; Shan, NL.; Pusztai, L. Molecular differences between younger versus older ER-positive and HER2-negative breast cancers. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2022, 8, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, KH.; Park, Y.; Kang, E.; Kim, EK.; Kim, JH.; Kim, SH.; Shin, HC. Effect of estrogen receptor expression level and hormonal therapy on prognosis of early breast cancer. Cancer Research and Treatment: Official Journal of Korean Cancer Association. 2022, 54, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, AM.; Friebel-Klingner, T.; Ehsan, S.; He, W.; Welch, M.; Chen, J.; Armstrong, K. Relationship of established risk factors with breast cancer subtypes. Cancer medicine. 2021, 10, 6456–6467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, AA.; Rolph, R.; Cutress, RI.; Copson, ER. A review of modifiable risk factors in young women for the prevention of breast cancer. Breast Cancer: Targets and Therapy.

- Bodewes, FTH. ; Van Asselt, AA.; Dorrius, MD.; Greuter, MJW.; De Bock, GH. Mammographic breast density and the risk of breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Breast. 2022, 66, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarmiento, DD.; Tumas, N.; Pereyra, SA.; Scruzzi, GF.; Pou, SA. Social determinants of breast cancer screening: a multilevel analysis of proximal and distal factors related to the practice of mammography. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2024, 33, 1651–1658. [Google Scholar]

- Czwikla, J.; Urbschat, I.; Kieschke, J.; Schüssler, F.; Langner, I.; Hoffmann, F. Assessing and explaining geographic variations in mammography screening participation and breast cancer incidence. Frontiers in Oncology. 2019, 9, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, HS.; Plichta, JK.; Kong, A.; Tan, CW.; Hwang, S.; Sultana, R.; Habib, AS. Risk factors for persistent pain after breast cancer surgery: a multicentre prospective cohort study. Anaesthesia. 2023, 78, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, I.; Kalichman, L.; Chen, N.; Susmallian, S. A comprehensive approach to risk factors for upper arm morbidities following breast cancer treatment: a prospective study. BMC cancer. 2021, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waks, AG.; Winer, EP. Breast cancer treatment: a review. Jama. 2019, 321, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, E.; Hiscox, S. New therapeutic approaches in breast cancer. Maturitas. 2011, 68, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trayes, KP.; Cokenakes, SE. Breast cancer treatment. American family physician. 2021, 104, 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Riis, M. Modern surgical treatment of breast cancer. Annals of medicine and surgery. 2020, 56, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, C.; Bauer-Nilsen, K.; McNulty, RH.; Vicini, F. Novel radiation therapy approaches for breast cancer treatment. In Seminars in Oncology. 2020, 47, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anampa, J.; Makower, D.; Sparano, JA. Progress in adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: an overview. BMC medicine. 2015, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denduluri, N.; Somerfield, MR.; Chavez-MacGregor, M.; Comander, AH.; Dayao, Z.; Eisen, A.; Giordano, SH. Selection of optimal adjuvant chemotherapy and targeted therapy for early breast cancer: ASCO guideline update. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2021, 39, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ficarra, S.; Thomas, E.; Bianco, A.; Gentile, A.; Thaller, P.; Grassadonio, F.; Hofmann, H. Impact of exercise interventions on physical fitness in breast cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review. Breast Cancer. 2022, 29, 402–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, JD.; Gray, E.; Pashayan, N.; Deandrea, S.; Karch, A.; Vale, DB.; Breast Screening Working Group. The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on breast cancer early detection and screening. Preventive medicine. 2021, 151, 106585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolarz, B.; Nowak, AZ.; Romanowicz, H. Breast cancer—epidemiology, classification, pathogenesis and treatment (review of literature). Cancers. 2022, 14, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goff, SL.; Danforth, DN. The role of immune cells in breast tissue and immunotherapy for the treatment of breast cancer. Clinical breast cancer. 2021, 21, e63–e73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukasiewicz, S.; Czeczelewski, M.; Forma, A.; Baj, J.; Sitarz, R.; Stanisławek, A. Breast cancer—epidemiology, risk factors, classification, prognostic markers, and current treatment strategies—an updated review. Cancers. 2021, 13, 4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schegoleva, AA.; Khozyainova, AA.; Fedorov, AA.; Gerashchenko, TS.; Rodionov, EO.; Topolnitsky, EB.; Denisov, EV. Prognosis of different types of non-small cell lung cancer progression: current state and perspectives. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2021, 55, 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Orrantia-Borunda, E.; Anchondo-Nuñez, P.; Acuña-Aguilar, LE.; Gómez-Valles, FO.; Ramírez-Valdespino, CA. Subtypes of breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2022.

- Zapletal, O.; Žatecký, J.; Gabrielová, L.; Selingerová, I.; Holánek, M.; Burkoň, P.; Coufal, O. Axillary Overtreatment in Patients with Breast Cancer After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in the Current Era of Targeted Axillary Dissection. Cancers. 2025, 17, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanth, P.; Inadomi, JM. Screening and prevention of colorectal cancer. Bmj. 2021, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monticciolo, DL.; Malak, SF.; Friedewald, SM.; Eby, PR.; Newell, MS.; Moy, L.; Smetherman, D. Breast cancer screening recommendations inclusive of all women at average risk: update from the ACR and Society of Breast Imaging. Journal of the American College of Radiology. 2021, 18, 1280–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cathcart-Rake, EJ.; Ruddy, KJ.; Bleyer, A.; Johnson, RH. Breast cancer in adolescent and young adult women under the age of 40 years. JCO oncology practice. 2021, 17, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, D.; Pal, D.; Sharma, R.; Garg, VK.; Goel, N.; Koundal, D.; Belay, A. [Retracted] Global Increase in Breast Cancer Incidence: Risk Factors and Preventive Measures. BioMed research international. 2022, (1), 9605439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrou, M.; Constantinidou, A. Tumor associated macrophages in breast cancer progression: implications and clinical relevance. Frontiers in Immunology. 2024, 15, 1441820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, P.; Brown, KA. Obese adipose tissue as a driver of breast cancer growth and development: update and emerging evidence. Frontiers in Oncology. 2021, 11, 638918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCart Reed, AE.; Kalinowski, L.; Simpson, PT.; Lakhani, SR. Invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast: the increasing importance of this special subtype. Breast Cancer Research. 2021, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. Surviving Late-Stage Cancers by Practicing Guan Yin Citta Dharma Door. Health Science Journal. 2024, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, NH.; Mobley, D.; Key, RG. Prostate Cancer: Expert Advice for Helping Your Loved One.2023.

- Shang, C.; Xu, D. Epidemiology of Breast Cancer. Oncologie (Tech Science Press). 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulska-Będkowska, W.; Czajka-Francuz, P.; Jurek-Cisoń, S.; Owczarek, AJ.; Francuz, T.; Chudek, J. The predictive role of serum levels of soluble cell adhesion molecules (sCAMs) in the therapy of advanced breast cancer—A single-centre study. Medicina. 2022, 58, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San Juan, BP.; Hediyeh-Zadeh, S.; Rangel, L.; Milioli, HH.; Rodriguez, V.; Bunkum, A.; Chaffer, CL. Targeting phenotypic plasticity prevents metastasis and the development of chemotherapy-resistant disease. MedRxiv. 2022, 2022–03. [Google Scholar]

- Guang, Y.; Wan, F.; He, W.; Zhang, W.; Gan, C.; Dong, P.; Zhang, Y. A model for predicting lymph node metastasis of thyroid carcinoma: a multimodality convolutional neural network study. Quantitative Imaging in Medicine and Surgery. 2023, 13, 8370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moral, R.; Escrich, E. Influence of olive oil and its components on breast cancer: Molecular mechanisms. Molecules. 2022, 27, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narain, R.; Muncie-Vasic, JM.; Weaver, VM. Forcing the code: tension modulates signaling to drive morphogenesis and malignancy. Genes & Development. 2025, 39, 163–181. [Google Scholar]

- Vickers, R.; Porter, W. Immune Cell Contribution to Mammary Gland Development. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia. 2024, 29, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, WK.; Law, BM.; Ng, MS.; He, X.; Chan, DN.; Chan, CW.; McCarthy, AL. Symptom clusters experienced by breast cancer patients at various treatment stages: a systematic review. Cancer Medicine. 2021, 10, 2531–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, CD.; Lamb, LR.; D'Alessandro, HA. Mitigating the impact of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) vaccinations on patients undergoing breast imaging examinations: a pragmatic approach. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2021, 217, 584–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, J.; Leblanc, M.; Elgbeili, G.; Cordova, MJ.; Marin, MF.; Brunet, A. The mental health impacts of receiving a breast cancer diagnosis: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Cancer. 2021, 125, 1582–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilkhomovna, KD. Manifestations of post-mastectomy syndrome, pathology of the brachial neurovascular bundle in clinical manifestations. Innovative Society: Problems, Analysis and Development Prospects (Spain).

- Harada, TL.; Uematsu, T.; Nakashima, K.; Kawabata, T.; Nishimura, S.; Takahashi, K.; Sugino, T. Evaluation of breast edema findings at T2-weighted breast MRI is useful for diagnosing occult inflammatory breast cancer and can predict prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Radiology. 2021, 299, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, G.; Ochoa, CY.; Farias, AJ. Religion and spirituality: their role in the psychosocial adjustment to breast cancer and subsequent symptom management of adjuvant endocrine therapy. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2021, 29, 3017–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, MK. Imaging of the Symptomatic Breast. In Breast & Gynecological Diseases: Role of Imaging in the Management. 2021, 27-79.

- Barba, D.; León-Sosa, A.; Lugo, P.; Suquillo, D.; Torres, F.; Surre, F.; Caicedo, A. Breast cancer, screening and diagnostic tools: All you need to know. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2021, 157, 103174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seif Abd Elalem, SG.; Kamel, HH.; Abd Elrahim, AH.; Osman, HA. Early Symptoms of Breast Cancer among Postmenopausal Women In El–Minia Oncology Center. Minia Scientific Nursing Journal. 2023, 14, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudjoe, D. Facilitators to Earlier Presentation among Women Diagnosed with Early Stage Breast Cancer Disease; a Systematic Narrative Review of Literature. 2024.

- Shaikh, K.; Krishnan, S.; Thanki, R.; Shaikh, K.; Krishnan, S.; Thanki, R. Types, diagnosis, and treatment of breast cancer. Artificial intelligence in breast cancer early detection and diagnosis. 2021, 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli, C.; Barberis, M. Breast cancer heterogeneity. Diagnostics. 2021, 11, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Kong, D.; Liu, J.; Zhan, L.; Luo, L.; Zheng, W.; Sun, S. Breast cancer heterogeneity and its implication in personalized precision therapy. Experimental hematology & oncology. 2023, 12, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez, C.; Owens, A.; Medeiros, L.; Dabydeen, D.; Sritharan, N.; Phatak, P.; Kandlikar, SG. Breast cancer detection using enhanced IRI-numerical engine and inverse heat transfer modeling: model description and clinical validation. Scientific Reports. 2024, 14, 3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, N.; Henderson, M.; Sundararajan, M.; Salas, M. Discrepancies in ICD-9/ICD-10-based codes used to identify three common diseases in cancer patients in real-world settings and their implications for disease classification in breast cancer patients and patients without cancer: a literature review and descriptive study. Frontiers in Oncology. 2023, 13, 1016389. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, PY. Liou, CF. Impact of patient resourcefulness on cancer patients’ pain management and medical opioid use: A cross-sectional study. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2025, 74, 102771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Planning for tomorrow: global cancer incidence and the role of prevention 2020–2070. Nature reviews Clinical oncology. 2021, 18, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cechanovičiūtė, V.; Cechanovičienė, I. (2022). Overview of the epidemiology, risk factors, clinical features, diagnostics and prevention of breast cancer. Medicinos mokslai. Medical sciences. Kėdainiai: VšĮ" Lietuvos sveikatos mokslinių tyrimų centras".

- Zubair, M.; Wang, S.; Ali, N. Advanced approaches to breast cancer classification and diagnosis. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2021, 2021. 11, 632079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, P.; Stephan, T.; Kannan, R.; Abraham, A. A hybrid artificial bee colony with whale optimization algorithm for improved breast cancer diagnosis. Neural Computing and Applications. 2021, 33, 13667–13691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, CH. Global challenges in breast cancer detection and treatment. The Breast. 2022, 62, S3–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, W.; Huang, M.; Leung, XY.; Li, Y. The healing impact of travel on the mental health of breast cancer patients. Tourism Management. 2025, 106, 104997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.; Wang, JHY. Fatalism and psychological distress among Chinese American Breast Cancer Survivors: mediating role of perceived self-control and fear of cancer recurrence. International journal of behavioral medicine. 2023, 30, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, JH.; Jung, YS.; Kim, JY.; Bae, SH. Determinants of quality of life in women immediately following the completion of primary treatment of breast cancer: A cross-sectional study. PloS one. 2021, 16, e0258447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannioto, RA.; Hutson, A.; Dighe, S.; McCann, W.; McCann, SE.; Zirpoli, GR.; Ambrosone, CB. Physical activity before, during, and after chemotherapy for high-risk breast cancer: relationships with survival. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2021, 113, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, I.; Said, MS.; Islam, M.; Nadeem, H.; Khan, AH.; Hashmi, AM. Clinical evaluation of patients suffering from breast cancer and determination of evolving treatment therapies and better strategies related to breast cancer. International Journal of Natural Medicine and Health Sciences. 2023, 2, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Emery, J.; Butow, P.; Lai-Kwon, J.; Nekhlyudov, L.; Rynderman, M.; Jefford, M. Management of common clinical problems experienced by survivors of cancer. The Lancet. 2022, 399, 1537–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiCaprio, MR.; Murtaza, H.; Palmer, B.; Evangelist, M. Narrative review of the epidemiology, economic burden, and societal impact of metastatic bone disease. Annals of Joint. 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergerot, C.; Bergerot, PG.; Maués, J.; Segarra-Vazquez, B.; Mano, MS.; Tarantino, P. Is cancer back?—psychological issues faced by survivors of breast cancer. Annals of Palliative Medicine. 2024, 13, 1229234–1221234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inam, F.; Bergin, RJ.; Mizrahi, D.; Dunstan, DW.; Moore, M.; Maxwell-Davis, N.; Swain, CT. Diverse strategies are needed to support physical activity engagement in women who have had breast cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2023, 31, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natalucci, V.; Villarini, M.; Emili, R.; Acito, M.; Vallorani, L.; Barbieri, E.; Villarini, A. Special attention to physical activity in breast cancer patients during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: the DianaWeb cohort. Journal of personalized medicine. 2021, 11, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magno, S.; Rossi, MM.; Filippone, A.; Rossi, C.; Guarino, D.; Maggiore, C.; Masetti, R. Screening for Physical Activity Levels in Non-Metastatic Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Surgery: An Observational Study. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2022, 21, 15347354221140327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, CL.; Thomson, CA.; Sullivan, KR.; Howe, CL.; Kushi, LH.; Caan, BJ.; McCullough, ML. American Cancer Society nutrition and physical activity guideline for cancer survivors. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2022, 72, 230–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albini, A.; La Vecchia, C.; Magnoni, F.; Garrone, O.; Morelli, D.; Janssens, JP.; Corso, G. Physical activity and exercise health benefits: cancer prevention, interception, and survival. European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2025, 34, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquinot, Q.; Meneveau, N.; Falcoz, A.; Bouhaddi, M.; Roux, P.; Degano, B.; Mougin, F. Cardiotoxicity is mitigated after a supervised exercise program in HER2-positive breast cancer undergoing adjuvant trastuzumab. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2022, 9, 1000846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, LJ.; Meredith, T.; Yu, J.; Patel, A.; Neal, B.; Arnott, C.; Lim, E. Heart failure therapies for the prevention of HER2-monoclonal antibody-mediated cardiotoxicity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Cancers. 2021, 13, 5527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travers, G.; Kippelen, P.; Trangmar, SJ.; González-Alonso, J. Physiological function during exercise and environmental stress in humans—an integrative view of body systems and homeostasis. Cells. 2022, 11, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Fernández-García, B.; Lehmann, HI.; Li, G.; Kroemer, G.; López-Otín, C.; Xiao, J. Exercise sustains the hallmarks of health. Journal of sport and health science. 2023, 12, 8–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagalaz-Anula, N.; Mora-Rubio, MJ.; Obrero-Gaitán, E.; Del-Pino-Casado, R. Recreational physical activity reduces breast cancer recurrence in female survivors of breast cancer: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2022, 59, 102162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, H.; Yang, Z.; Li, J.; Wen, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zheng, Y.; He, J. Associations between female lung cancer risk and sex steroid hormones: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the worldwide epidemiological evidence on endogenous and exogenous sex steroid hormones. BMC cancer. 2021, 21, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanty, SS.; Mohanty, PK. Obesity as potential breast cancer risk factor for postmenopausal women. Genes & diseases. 2021, 8, 117–123. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, BM.; Berry, DC. The regulation of adipose tissue health by estrogens. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2022, 13, 889923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetemäki, N.; Robciuc, A.; Vihma, V.; Haanpää, M.; Hämäläinen, E.; Tikkanen, MJ.; Savolainen-Peltonen, H. Adipose tissue sex steroids in postmenopausal women with and without menopausal hormone therapy. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

- Iwase, T.; Wang, X.; Shrimanker, TV.; Kolonin, MG.; Ueno, NT. Body composition and breast cancer risk and treatment: mechanisms and impact. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2021, 186, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleach, R.; Sherlock, M.; O’Reilly, MW.; McIlroy, M. Growth hormone/insulin growth factor axis in sex steroid associated disorders and related cancers. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2021, 9, 630503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, MA.; Strickler, HD.; Hutson, AD.; Einstein, MH.; Rohan, TE.; Xue, X.; Gunter, MJ. Sex hormones, insulin, and insulin-like growth factors in recurrence of high-stage endometrial cancer. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2021, 30, 719–726. [Google Scholar]

- Gharahdaghi, N.; Phillips, BE.; Szewczyk, NJ.; Smith, K.; Wilkinson, DJ.; Atherton, PJ. Links between testosterone, oestrogen, and the growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor axis and resistance exercise muscle adaptations. Frontiers in physiology. 2021, 11, 621226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’alonzo, NJ.; Qiu, L.; Sears, DD.; Chinchilli, V.; Brown, JC.; Sarwer, DB.; Sturgeon, KM. WISER survivor trial: combined effect of exercise and weight loss interventions on insulin and insulin resistance in breast cancer survivors. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieli-Conwright, CM.; Harrigan, M.; Cartmel, B.; Chagpar, A.; Bai, Y.; Li, FY.; Irwin, ML. Impact of a randomized weight loss trial on breast tissue markers in breast cancer survivors. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2022, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgeon, K. M.; Brown, JC.; Sears, DD.; Sarwer, DB.; Schmitz, KH. WISER survivor trial: combined effect of exercise and weight loss interventions on inflammation in breast cancer survivors. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2023, 55, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvie, M.; Pegington, M.; Howell, SJ.; Bundred, N.; Foden, P.; Adams, J.; Howell, A. Randomised controlled trial of intermittent vs continuous energy restriction during chemotherapy for early breast cancer. British Journal of Cancer. 2022, 126, 1157–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.; Sturgeon, KM.; Gordon, BR.; Brown, JC.; Sears, DD.; Sarwer, DB.; Schmitz, KH. WISER survivor trial: combined effect of exercise and weight loss interventions on adiponectin and leptin levels in breast cancer survivors with overweight or obesity. Nutrients. 2023, 15, 3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei, P.; Hoseini, R. Exercise training modulates adipokine dysregulations in metabolic syndrome. Sports Medicine and Health Science. 2022, 4, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Gutierrez, A.; Aguilera, CM.; Osuna-Prieto, FJ.; Martinez-Tellez, B.; Rico Prados, MC.; Acosta, FM.; Sanchez-Delgado, G. Exercise-induced changes on exerkines that might influence brown adipose tissue metabolism in young sedentary adults. European Journal of Sport Science. 2023, 23, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A. S.; Renehan, AG.; Saxton, JM.; Bell, J.; Cade, J.; Cross, AJ.; Martin, RM. Cancer prevention through weight control—where are we in 2020? British Journal of Cancer. 2021, 124, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadier, N. S.; El Hajjar, F.; Al Sabouri, AAK. ; Abou-Abbas, L.; Siomava, N.; Almutary, AG.; Tambuwala, MM. Irisin: An unveiled bridge between physical exercise and a healthy brain. Life Sciences. 2024, 339, 122393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okechukwu, CE.; Okechukwu, CE.; Agag, A.; Naushad, N.; Abbas, S.; Deb, AA. Hypothesized biological mechanisms by which exercise-induced irisin mitigates tumor proliferation and improves cancer treatment outcomes. MGM Journal of Medical Sciences. 2021, 8, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, R.; Shamsi, A.; Mohammad, T.; Hassan, MI.; Kazim, SN.; Chaudhary, AA.; Islam, A. FNDC5/irisin: physiology and pathophysiology. Molecules. 2022, 27, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Kenfield, SA.; Yanagisawa, Y.; Newton, RU. Why exercise has a crucial role in cancer prevention, risk reduction and improved outcomes. British medical bulletin. 2021, 139, 100–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, M.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, D.; Liu, S.; Tao, Y. Signaling pathways in cancer metabolism: mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2023, 8, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbar, N.; Khan, NA.; Muhammad, JS. Siddiqui, R. The role of gut microbiome in cancer genesis and cancer prevention. Health Sciences Review. 2022, 2, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhernakova, DV.; Kurilshikov, A.; Andreu-Sánchez, S.; Wang, D.; Augustijn, HE.; Fu, J. Influence of the microbiome, diet and genetics on inter-individual variation in the human plasma metabolome. Nature medicine. 2022, 28, 2333–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jelic, MD.; Mandic, AD.; Maricic, SM.; Srdjenovic, BU. Oxidative stress and its role in cancer. Journal of cancer research and therapeutics. 2021, 2021. 17, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, BM.; Banik, BK.; Borah, P.; Jain, A. Reactive oxygen species (ROS): key components in cancer therapies. Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry (Formerly Current Medicinal Chemistry-Anti-Cancer Agents). 2022, 22, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Salehi, H.; Rahman, MA.; Zahid, Z.; Madadkar Haghjou, M.; Najafi-Kakavand, S.; .Zhuang, W. Plant hormones and neurotransmitter interactions mediate antioxidant defenses under induced oxidative stress in plants. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2022, 13, 961872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, OE.; Akosile, OA.; Oni, AI.; Opowoye, IO.; Ishola, C. A.; Adebiyi, JO.; Abioja, MO. Oxidative stress in poultry production. Poultry Science. 2024, 104003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Hussain, SJ.; Kaur, G.; Poor, P.; Alamri, S.; Siddiqui, MH.; Khan, MIR. Salicylic acid improves nitrogen fixation, growth, yield and antioxidant defence mechanisms in chickpea genotypes under salt stress. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation. 2022, 41, 2034–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lei, Z.; Sun, T. The role of microRNAs in neurodegenerative diseases: a review. Cell Biology and Toxicology. 2023, 39, 53–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwani, A.; Andreasik, A.; Szatanek, R.; Siedlar, M.; Baj-Krzyworzeka, M. The role of miRNA in regulating the fate of monocytes in health and cancer. Biomolecules. 2022, 12, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, JAC. ; Veras, ASC.; Batista, VRG.; Tavares, MEA.; Correia, RR.; Suggett, CB.; Teixeira, GR. Physical exercise and the functions of microRNAs. Life sciences. 2022, 304, 120723. [Google Scholar]

- Khoury, R.; Nagy, C. Running from stress: a perspective on the potential benefits of exercise-induced small extracellular vesicles for individuals with major depressive disorder. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences. 2023, 10, 1154872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeidi, A.; Tayebi, SM.; To-Aj, O.; Karimi, N.; Kamankesh, S.; Niazi, S.; Zouhal, H. Physical Activity, Natural Products, and Minerals in the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: An Update. Annals of applied sport science. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aya, V.; Flórez, A.; Perez, L.; Ramírez, JD. Association between physical activity and changes in intestinal microbiota composition: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2021, 16, e0247039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Johnston, LJ.; Wu, C.; Ma, X. Gut microbiota and its metabolites: Bridge of dietary nutrients and obesity-related diseases. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition. 2023, 63, 3236–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, MM.; Islam, MR.; Shohag, S.; Ahasan, MT.; Sarkar, N.; Khan, H.; Rauf, A. Microbiome in cancer: Role in carcinogenesis and impact in therapeutic strategies. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2022, 149, 112898. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Molina, E.; Furtado, GE.; Jones, JG.; Portincasa, P.; Vieira-Pedrosa, A.; Teixeira, AM.; Sardão, VA. The advantages of physical exercise as a preventive strategy against NAFLD in postmenopausal women. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2022, 52, e13731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutac, P.; Buzga, M.; Elavsky, S.; Bunc, V.; Jandacka, D.; Krajcigr, M. The Effect of Regular Physical Activity on Muscle and Adipose Tissue in Premenopausal Women. Applied Sciences. 2021, 11, 8655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenech, MF.; Bull, CF.; Van Klinken, BJW. Protective effects of micronutrient supplements, phytochemicals and phytochemical-rich beverages and foods against DNA damage in humans: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials and prospective studies. Advances in Nutrition. 2023, 14, 1337–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistelli, M.; Natalucci, V.; Scortichini, L.; Agostinelli, V.; Lenci, E.; Crocetti, S.; Berardi, R. The impact of lifestyle interventions in high-risk early breast cancer patients: a modeling approach from a single institution experience. Cancers. 2021, 13, 5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimauro, I.; Grazioli, E.; Antinozzi, C.; Duranti, G.; Arminio, A.; Mancini, A.; Di Luigi, L. Estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer in postmenopausal women: the role of body composition and physical exercise. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2021, 18, 9834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obeagu, EI.; Obeagu, GU. Breastfeeding’s protective role in alleviating breast cancer burden: A comprehensive review. Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 2024, 86, 2805–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Chico, C.; López-Ortiz, S.; Peñín-Grandes, S.; Pinto-Fraga, J.; Valenzuela, PL.; Emanuele, E.; Santos-Lozano, A. Physical exercise and the hallmarks of breast cancer: a narrative review. Cancers. 2023, 15, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negrini, KA.; Lin, D.; Shah, D.; Wu, H.; Wehrung, KM.; Thompson, HJ.; Sturgeon, KM. Role of Oncostatin M in Exercise-Induced Breast Cancer Prevention. Cancers. 2024, 16, 2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Parra, N.; Cupeiro, R.; Alfaro-Magallanes, VM.; Rael, B.; Rubio-Arias, JÁ. ; Peinado, AB.; IronFEMME Study Group. Exercise-induced muscle damage during the menstrual cycle: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2021, 35, 549–561. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Suen, SC.; Lewis, SJ.; Martin, RM.; English, DR.; Boyle, T.; Giles, GG.; Zheng, W. Physical activity, sedentary time and breast cancer risk: a Mendelian randomisation study. British journal of sports medicine. 2022, 56, 1157–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, AM.; Wang, D.; Perumal, N.; Liu, E.; Wang, M.; Ahmed, T.; GWG Pooling Project Consortium. Risk factors for inadequate and excessive gestational weight gain in 25 low-and middle-income countries: An individual-level participant meta-analysis. PLoS medicine. 2023, 20, e1004236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennfjord, MK.; Gabrielsen, R.; Tellum, T. Effect of physical activity and exercise on endometriosis-associated symptoms: a systematic review. BMC women's health. 2021, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, MS.; Saleem, J.; Zakar, R.; Aiman, S.; Khan, MZ.; Fischer, F. Benefits of physical activity on reproductive health functions among polycystic ovarian syndrome women: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2023, 23, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhou, W. Roles and molecular mechanisms of physical exercise in cancer prevention and treatment. Journal of sport and health science. 2021, 10, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Approaches | Procedure |

|---|---|

| Surgical Resection | At the outset of breast cancer, surgical removal of the tumor is possible. The earlier the tumor is removed, the higher the survival rate. |

| Radiotherapy | High-energy radiation are used to destroy cancer cells, which is often used to get rid of leftover cancer tissues after surgery. |

| Adjuvant Chemotherapy | Chemotherapy is done after surgery to target any remaining cancer cells and prevent the cancer from coming back. |

| Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy | Chemotherapy is administered before surgery to shrink the tumor so that it can be removed during surgery. |

| Hormonal Therapies | In cancer treatment, they are used as hormone receptor blockers to help block hormones (such as estrogen) that promote tumor growth. |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | Using antibodies for targeted therapy, like trastuzumab (Herceptin), is especially effective against HER2 positive breast cancer. |

| Immunotherapy | This viewpoint makes a difference boost the body's resistant framework to battle cancer and appears guarantee in forceful sorts of breast cancer. |

| Small Molecular Inhibitors | They target particular molecular pathways included in cancer cell development and survival, giving more successful and less poisonous medications than chemotherapy. |

| Physical activity | There are many theories that explain how the body reduces the risk of cancer. This includes a lower risk for estrogen and androgens. There are also some factors related to insulin, adipokines, etc. Similar mechanisms might work in the survival of breast cancer. This will overall reduce mortality and recurrence related to the disease. |

| Sex steroid hormones | Estrogen, Testosterone and androgens |

| Metabolic hormones | Insulin, Insulin-like growth factor, Leptin, |

| Inflammatory markers | C-reactive proteins, Tumor necrosis factor, Inter leukins |

| Stress hormones | Cortisol, Epinephrine, Nor Epinephrine |

| Adipokines | Resistin, Adiponectin |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).