1. Introduction

Plant pollen carries the male gamete, or sperm cells, essential for seed production [

1]. Pollen DNA isolation is helpful for multiple disciplines. For example, pollen DNA has been used to investigate plant-pollinator relationships and bee ecology [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9], food (honey) authentication [

10,

11], human immunology via pollen monitoring [

12,

13,

14], urbanization effects on the environment [

15,

16], historical and forensic analyses [

17,

18,

19] and to analyse the pollen microbiome [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. In several of these disciplines (e.g.

, forensic analysis), only trace pollen quantities are sometimes available, making pollen DNA-based analysis challenging. Methodological advancements are needed to improve DNA yields with less starting pollen.

Pollen grains are composed of an outer surface, known as the pollen wall, which provides protection and structural support. The components of the pollen wall include the outer (exine) layer, the inner (intine) layer, and the tryphine or pollen coat which is deposited between the cavities formed in the exine [

27]. This results in a unique patterning of the pollen outer surface which is dependent on plant species and mode of pollination [

1,

27,

28]. During development, pollen progenitor cells utilize a multitude of substrates for the biosynthesis of the pollen wall, including complex proteins, lipids, carbohydrates and phenolic compounds [

29,

30]. At the lysis stage of the DNA isolation process, these elements become exposed in the pollen lysate and can interfere with downstream steps affecting DNA yields. The pollen exine layer is of primary concern. The exine is comprised of the stable biopolymer sporopollenin, which is resistant to common terrestrial stressors such as heat, solubility, UV damage and oxidation [

31]. An early study from 1997 found that mechanical lysis via bead-beating was the most effective approach to break down exine and extract DNA from ruptured tree pollen grains when compared to chemical and temperature-based approaches [

32]. It is now a widely applied pollen lysis method in many commercial kits and in-house protocols.

To remove exine debris, chloroform containing reagents can be used to separate nucleic acids from other cellular remnants. In-house protocols extract debris using chloroform:isoamyl alcohol 24:1 (C:I), phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol 25:24:1 (P:C:I) or chloroform [

46] (

Table 1), while commercial kits omit the use of such solvents as a post-lysis cleaning step. Instead, commercial kits rely on an initial crude lysate filter followed by multiple ethanol buffer wash steps to remove DNA impurities. In addition, in-house methods and commercial DNA isolation kits differ in that the former is typically less costly but more time consuming compared to the latter. Furthermore, across many pollen DNA isolation methods, there appears to be a varying selection of parameters used (

Table 1). This includes the amount of starting pollen material and how it is quantified (per grain or by weight), lysis method, duration and strength, and finally the selection of high-performing DNA isolation protocols, in-house or commercial.

This study had two main objectives. The first objective was to conduct a systematic literature review of pollen DNA isolation optimization studies to identify protocol parameter modifications that significantly improved DNA yields, while revealing potential optimization gaps. This review revealed that users of commercial DNA kits have not employed organic solvents to remove pollen debris. In our own early trials, we experienced low pollen DNA yields with a commercial DNA isolation kit, which we suspected was due to clogging of the filter columns by such debris. As a result, our second objective was to test the addition of chloroform: isoamyl alcohol (C:I) as a post-lysis cleaning step in conjunction with a commercial DNA isolation kit to determine its effect on final pollen DNA yields. Maize/corn (

Zea mays L. ssp.

mays) was used as a model system due to its readily accessible pollen as a wind-pollinated plant [

47], and for its importance as one of the top three most important food crops globally [

48]. Modifications to additional parameters were tested alongside the presence or absence of C:I to reveal whether short (70 s) or long (6 min) lysis durations and small (15±5 mg) or large (125±25 mg) pollen amounts could be optimized for maximum DNA yield. Finally, based on the literature review, two bead type modifications were selected to test pollen lysis performance, specifically 0.5 mm glass and 2.8 mm ceramic beads, using the optimized parameters.

2. Results

2.1. Systematic Review of Published Pollen DNA Isolation Studies

Fifteen pollen DNA isolation optimization studies fit the selection criteria and are summarized in

Table 1. An assortment of different plant sources were used in these studies, and aimed to: (1) test different protocols and/or kits against one another based on highest DNA yields obtained [

34,

35,

38,

39,

44]; (2) present a single new protocol [

2,

32,

33,

37,

40,

41,

43,

45]; or (3) test different bead materials and sizes alone [

36] or in conjunction with different commercial kits [

42].

Variables were observed in two aspects of the basic pollen DNA isolation protocol. The first variable was the pollen sample amount, where starting sample quantities ranged from less than 10 mg to 200 mg (

Table 1, column “Amount”). Since several studies measured pollen quantity by number of grains, it is uncertain whether the proposed range was accurate (

Table 1). Pollen-containing liquid honey sample quantities were similar in that they were reported by weight (g) or volume (ml) and were tested at amounts of 15 g and 50 g for the former, and 3 ml and 12.5 ml for the latter (

Table 1). The second variable were parameters related to lysis. Mechanical lysis was conducted using bead mill, vortex, thermomixer or manual methods which have different metrics to measure strength, while lysis duration typically ranged from 1 to 5 min but also extended into 10 min and 3 h (

Table 1, column “Mechanical; duration”). These longer duration times were coupled with the use of a thermomixer and loosely correlated to larger sample amount (

Table 1, column “Amount” and “Mechanical; duration”). These observations suggest that several foundational parameters underlying pollen DNA isolation protocols in the literature are inconsistent, which in turn affects the comparability of final DNA yields across studies.

In the context of comparative analyses of kits and/or methods, two studies reported that their top performing protocol based on maximum DNA yield were in-house methods when compared to commercial kits: one CTAB- [

38] and one SDS- [

34] based method. Four single method studies also employ in-house CTAB-based pollen DNA extraction methods (

Table 1, column “Study type” and “Kit/Method”). In contrast, three separate studies reported the use, each, of the FastDNA

® SPIN Kit for Soil with modifications [

39], Macherey-Nagel NucleoMag

® Tissue kit [

42] and Wizard

® DNA purification resin and columns [

44] as the best performing compared to the other commercial kits tested. These top performing commercial kits or kit components were not used in any of the other studies listed in

Table 1, although the Qiagen DNeasy Plant kit and Macherey-Nagel Nucleospin kit variations were often employed in comparative and single method studies (

Table 1). These findings indicate that although commercial kits are a popular choice for extracting pollen DNA, in-house methods are just as effective with potentially better DNA yields in comparison.

Bead type optimization was tested by two studies [

36,

42], both of which achieved higher pollen DNA yields with beads larger than 1 mm made of harder material such as ceramic or steel (

Table 1). Several past and recent studies have used glass beads of 1 mm or less, however a few others have incorporated ceramic and steel beads into their pollen DNA isolation protocols to obtain relatively high pollen DNA yields (

Table 1, column “Bead type”). Ceramic beads have been observed with diameters of 0.1 mm, 1.4 mm and 2.8 mm, while the standard diameter for steel beads was consistently 5 mm (

Table 1, column “Bead type”). Furthermore, one study used a matrix of three different bead sizes and materials, including 1.4 mm ceramic beads [

39]. Taken together, these findings suggest that the selection of lysis beads that are relatively larger sized ceramic or steel material improve pollen rupture and final DNA yields.

Finally, it was observed that proteinase K was used in 13 of the 15 pollen DNA isolation protocols as a chemical lysis agent to breakdown proteins and enzymes regardless of the method or kit used (

Table 1, column “Chemical”). This observation indicates that proteinase K is a comparatively standard component of most pollen DNA isolation protocols.

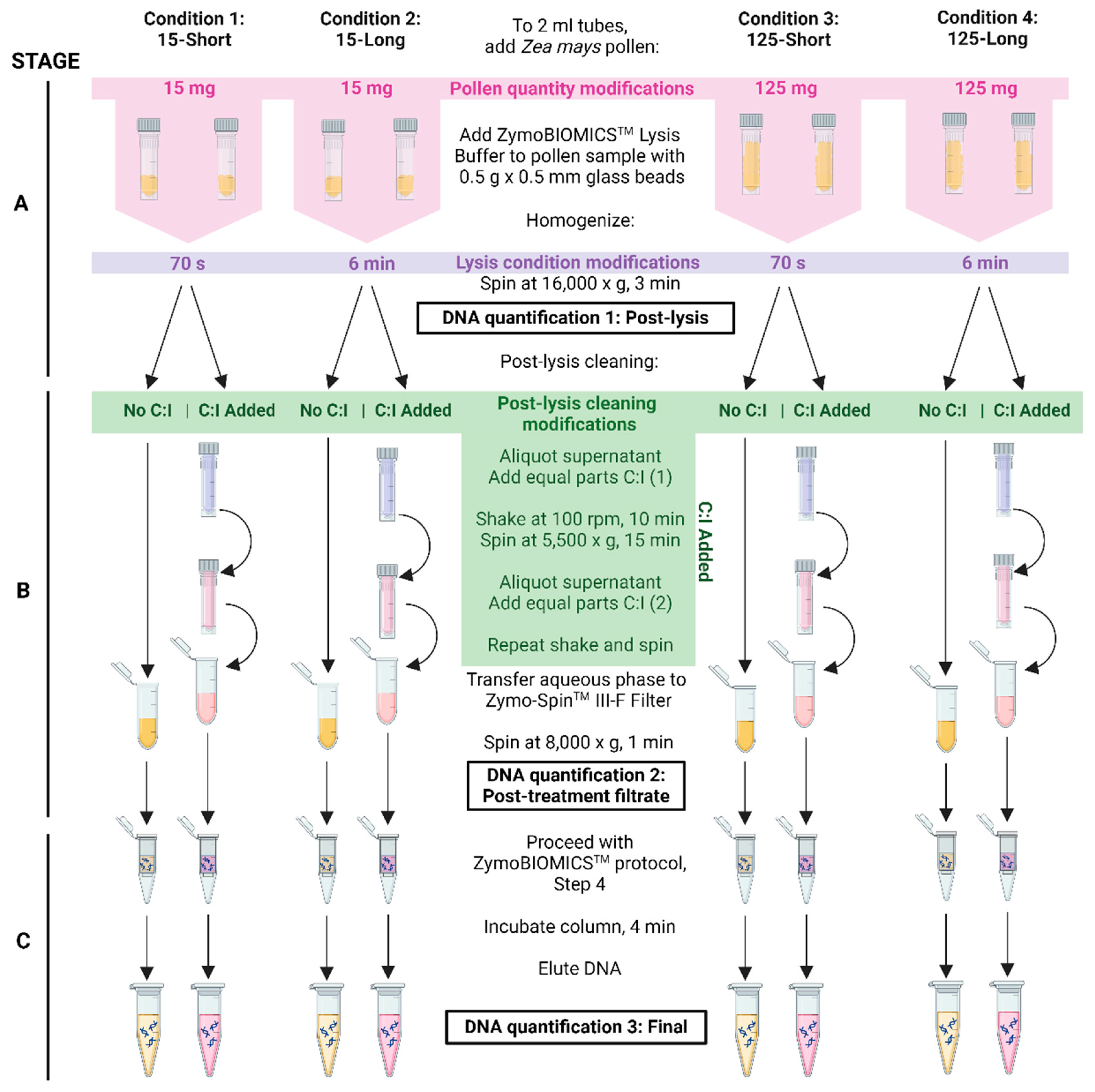

2.2. Chloroform:isoamyl Alcohol (C:I) Extraction as a Post-Lysis Cleaning Step to Improve Final Pollen DNA Yields

We hypothesized that low pollen DNA yields are due to pollen exine lysate clogging the DNA purification column, preventing DNA elution. To attempt to overcome this, chloroform:isoamyl alcohol 24:1 v/v (C:I) based extraction was added as a post-lysis cleaning step (

Figure 1, Stage B). As significant debris was found after the first extraction, two extractions were used. The final DNA yields of the cleaned samples were compared to the non-C:I controls (

Figure 1, DNA Quantification 3). Four different treatments were undertaken, each with a different combination of pollen quantity and

lysis duration: 15-Short (15±5 mg, 70 s of lysis), 15-Long (15±5 mg, 6 min of lysis), 125-Short (125±25 mg, 70 s of lysis) and 125-Long (125±25 mg, 6min of lysis).There were eight replicates per treatment, and two independent trials (

Figure 1;

Table 2). Both trials showed a similar trend of increased final median DNA yields obtained with +C:I in comparison to the non-C:I added control (

Table 3, bottom 3 rows). The final yield increase with +C:I was significant (p≤0.05) for 4 of the 8 attempts across the trials and ranged from 2-10 fold, with the exception of some samples containing 15±5 mg and one trial of the 125-Short treatment. The majority of these exceptions had no detectable DNA yields, regardless of the C:I treatment (

Table 3, bottom row). There were no examples where the non-C:I treated sample final yield was significantly higher than the +C:I treated sample yield. The results suggest that the addition of C:I as a post-lysis cleaning step is not detrimental to final pollen DNA yields and may increase it significantly.

In order to understand at which step in the protocol C:I extractions improve final pollen DNA yields, the same samples were quantified for DNA at earlier time points (

Figure 1, DNA Quantification 1 and 2). First, DNA yields were quantified at the post-lysis step (

Figure 1, Stage A). The samples across treatment groups were handled identically at this point, and hence no differences were expected, but this quantification was added as an internal control to ensure the starting pollen tissues across treatment groups were not biologically different. As expected, no significant differences were observed at this stage between the pre-treatment No C:I group compared to the pre-treatment C:I group (at p≤ 0.05), although the 125-Short condition was significantly different at the 0.10 level (

Table 3, top 3 rows).

Next, the +/-C:I post-treatment filtrates (

Figure 1, DNA Quantification 2) were measured which we hypothesized would differ due to the addition of C:I treatment relative to the non-C:I added control (

Figure 1, Stage B). The DNA yields at this stage from both trials generally showed no significant difference between the +C:I and the non-C:I samples (

Table 3, middle 3 rows). The exceptions were the pollen samples weighing 125±25 mg in Trial 1 (p=0.0078) and the 15-Short condition in Trial 2 (p=0.0781) which resulted in significantly less DNA yield in the +C:I treatment group relative to the control (

Table 3, middle 3 rows). These results indicate that the C:I treatment does not assist with the initial DNA filtering step.

Thus, it was hypothesized that the higher final DNA yields of the C:I treated samples relative to the non-C:I treated control samples were due to lower DNA loss during the intermediary steps of DNA binding to the column matrix and DNA washing (

Figure 1, Stage C). Consistent with this hypothesis, the results show that across both trials, the percentage of pollen DNA that was retained between the post +/-C:I filtrate (DNA Quantification 2) and final DNA quantification (DNA Quantification 3) in the untreated C:I control samples range from 1.1% - 4.3%, while C:I treated samples retained a range of 1.9% - 24.3% DNA (

Table 3).

2.3. The Optimization of Pollen Lysis Duration According to Sample Quantity Can Improve Final DNA Yields

To determine if pollen DNA yields could be further increased by optimizing the initial lysis duration, Short (70 s) and Long (6 min) lysis durations were tested (

Figure 1, Stage A). These treatments were applied to the low and high pollen weights, and to the post-lysis +C:I and non-C:I groups. Two independent trials were conducted, containing eight replicates for each lysis duration (

Table 2). For the 125±25 mg pollen samples, both trials showed a significant increase in final DNA yields with the 6 min lysis duration (p≤0.05) compared to the 70 s lysis duration, regardless of C:I treatment group (

Table 4).

For the 15±5 mg pollen samples, the 70 s lysis duration resulted in a trend of higher final DNA yields in both the non-C:I: and C:I added groups among Trial 1 samples, while no significant difference was observed between lysis duration treatments in Trial 2 (

Table 4). Notably, of the Trial 2 samples containing 15±5 mg pollen, the 16 samples that were not treated with C:I had no detectable final DNA yields, regardless of lysis duration (

Table 2). These findings indicate that in combination with +C:I treatment, DNA yields obtained from low pollen quantity samples likely benefit from a shorter lysis duration, while DNA yields obtained from higher pollen quantity samples can be significantly improved with a longer lysis duration.

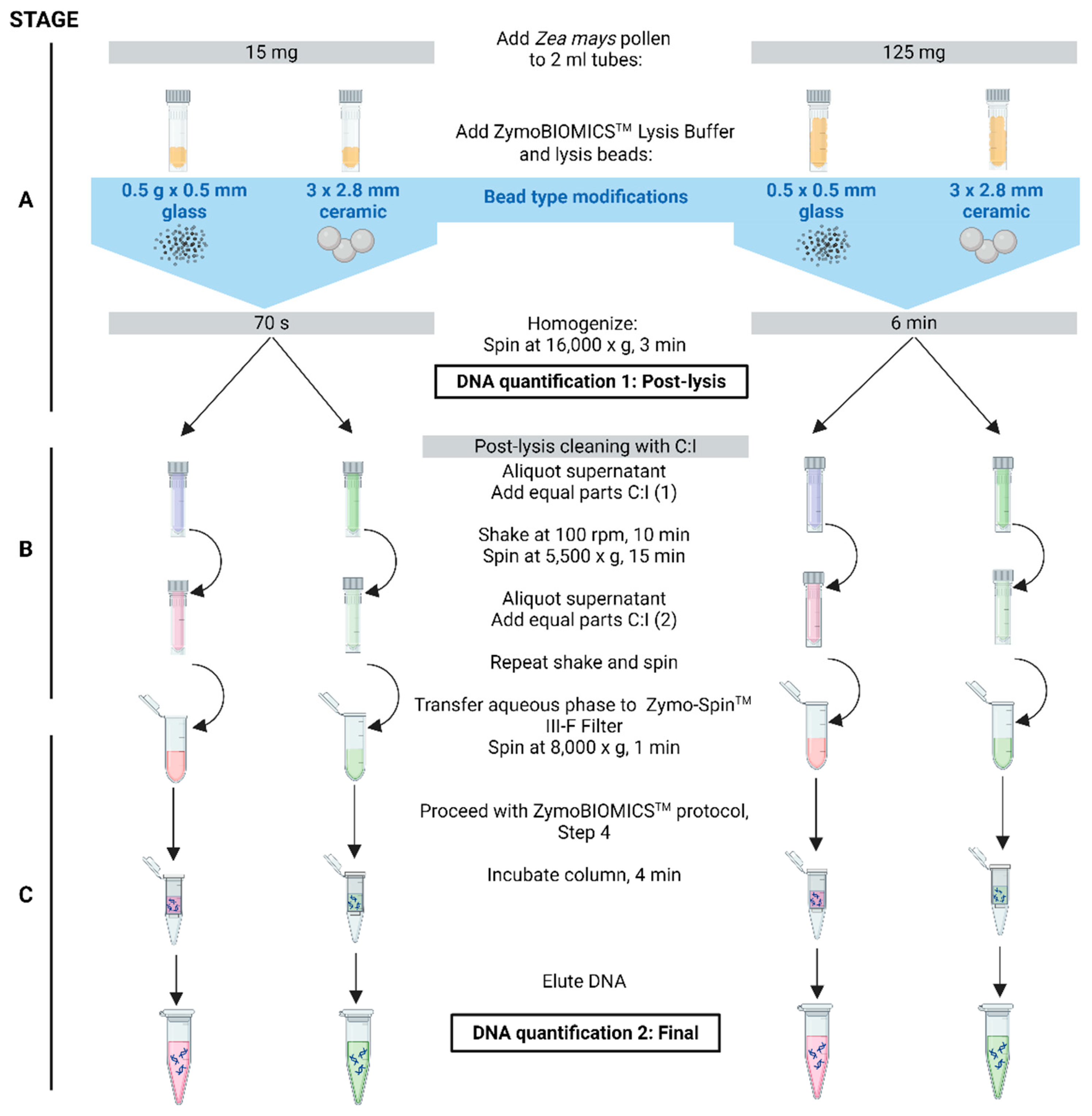

2.4. Bead Type Dramatically Impacts Pollen DNA Yields in Conjunction with +C:I Treatment

It was reported that 0.5 mm glass beads (0.5 g/tube) were less effective at rupturing pollen compared to 2.8 mm ceramic beads (3 beads/tube) [

36]. To confirm and extend this finding in the context of our protocol modifications, the same two bead types and amounts were tested (

Figure 2). The optimized conditions used were: for 15±5 mg pollen samples, a 70 s lysis duration with C:I treatment; for 125±5 mg pollen samples, a 6 min lysis duration with C:I treatment. Two independent trials were conducted containing eight replicates per bead type (

Table 5).

The results showed that the 2.8 mm diameter ceramic beads produced significantly higher post-lysis yields (p = 0.0078 at DNA Quantification 1 in

Figure 2) and final yields (p = 0.0078 at DNA Quantification 2 in

Figure 2) compared to the 0.5 mm diameter glass beads across both trials and conditions tested (

Table 6).

3. Discussion

Pollen DNA isolation is becoming more utilized for different applications. However, we hypothesized that not only efficient rupture, but also removal of the post-lysis pollen exine layer and other debris can interfere with this process. After completing a systematic literature review of published DNA isolation methods, the major advance of this study was that the addition of chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (C:I) as a post-lysis cleaning step improved final maize pollen DNA yields when using a commercial DNA isolation kit regardless of pollen amount or lysis condition. We showed that by optimizing other parameters such as lysis duration, pollen quantity and bead type in combination with the addition of C:I, final DNA yields could be enhanced further.

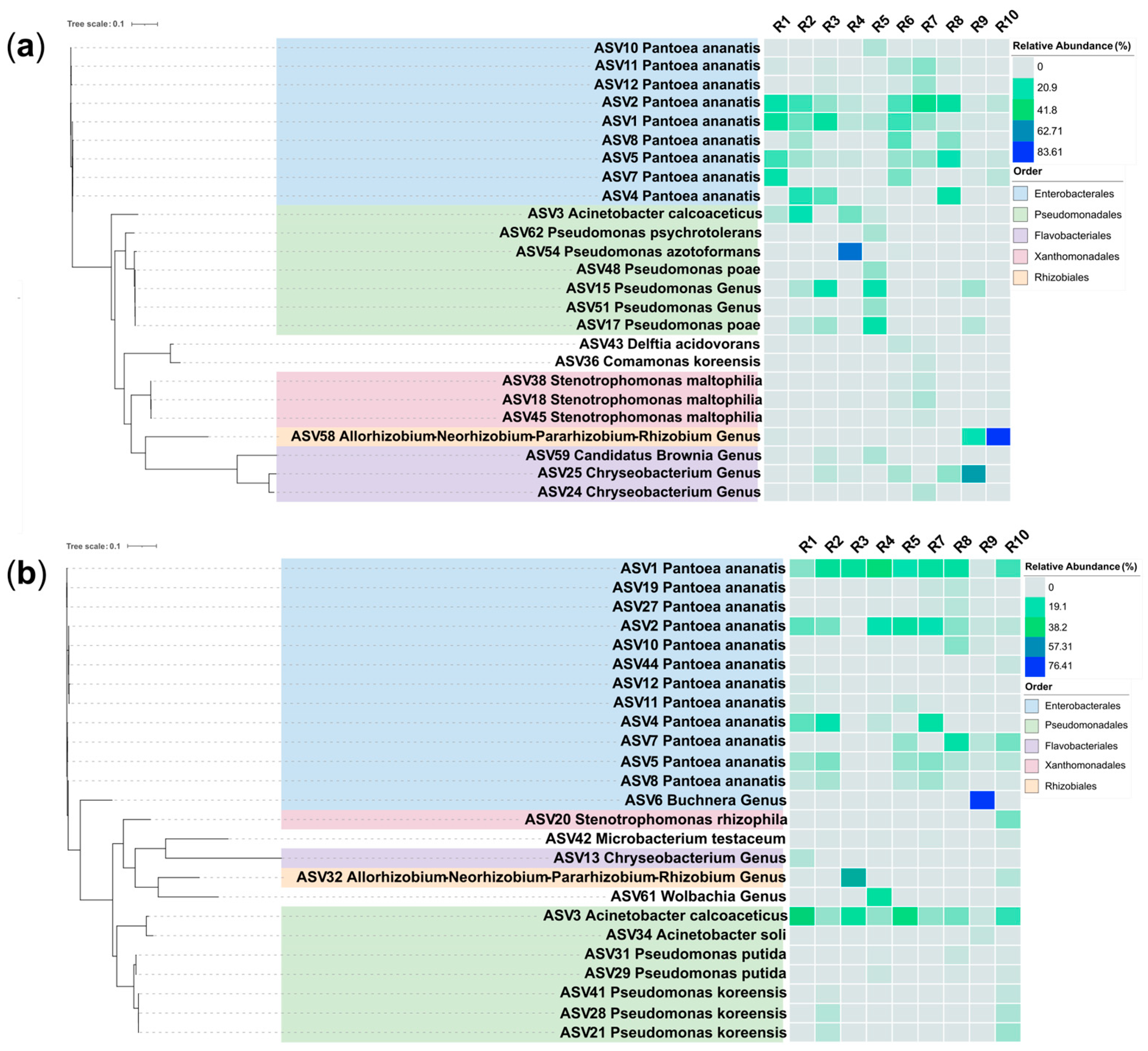

3.1. The Addition of Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol Permits Downstream Applications

The addition of chloroform:isoamyl alcohol to a standard DNA isolation kit protocol resulted in high quality DNA that could be used for further downstream applications including PCR, sequencing and microbiome taxonomic profiling. Microbiome data from two years that used this step is shown (

Figure 3), illustrating the general reproducibility of the bacterial taxa recovered, subject to the presumptive effect of seasonality. For example, of the top 25 amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) shown per trial, 92% of all ASVs belonged to one of five taxonomic groups at the order level (

Figure 3). At the ASV level,

Pantoea ananatis was the most dominant species, with eight ASVs present across both trials. Our laboratory has now used this modification with hundreds of maize pollen DNA samples for microbiome sequencing, including those reported by Khalaf et al. [

26], at two independent sequencing facilities and found it to be robust and reliable, whereas we had a high rate of failures in the absence of C:I extraction.

3.2. Barriers to Standardizing Pollen DNA Isolation Protocols

The studies summarized in

Table 1 illustrated methodological variability across published pollen DNA isolation optimization protocols, primarily related to pollen sample amount, mode of mechanical lysis and lysis duration [

49] and kit/method selection. Notably, pollen grain size, composition [

49], and biological availability of pollen are inherent challenges that exist in this field and can directly affect the above parameters. For example, higher pollen aperture number was shown to significantly increase pollen resistance to rupture [

36]. Parameter selection may also result from equipment and kit/method availability or familiarity. Although these caveats may continue to persist in future research, efforts can be made to minimize their impact and improve comparability across studies. Based on the systematic literature review of pollen DNA isolation optimization studies conducted here, good future practices may include reporting starting pollen sample amounts by weight (mg) and number of grains, and for liquid honey samples, reporting the weight (mg) of the pollen pellet after centrifugation, as done by Torricelli et al., [

37] and Chavan et al., [

40].

To address lysis related parameters, we suggest testing the working protocol on either (1) different quantities of pollen, or if pollen availability is limited, to test (2) different lysis duration times on the shorter and higher end of the 1 min to 5 min range (

Table 1). Metrics such as final DNA yields and percentage of pollen ruptured should be measured to determine the extent of pollen lysis while avoiding DNA shearing [

32,

36]. To further improve pollen rupture, kit or protocol lysis beads can be substituted or mixed with 1.4 mm or 2.8 mm ceramic, or 5 mm steel beads if they are not already being used [

36,

42]. Finally, proteinase K can also be added to digest proteins and enzymes that may target and/or degrade pollen DNA, post-lysis. Results obtained with any of the above modifications should be compared and reported in the respective publication.

With respect to the selection of commercial kits or in-house methods, research is needed to further verify the observation that in-house methods have greater DNA yields than commercial kits. If this is the case, there may be a bias for in-house methods favouring exine containing plant samples, possibly due to improved removal of exine and cell debris in the lysate that would otherwise interfere with downstream DNA binding and/or cleaning. This may be partially attributed to the use of chloroform containing reagents during post-lysis cleaning, however, it has yet to be comprehensively explored.

3.3. Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol Extraction Improves Pollen DNA Yields

The improvements observed in final DNA yields with the addition of C:I revealed some inconsistencies. Of the 8 conditions tested across both trials, only 4 attempts had significantly higher final median DNA yields with +C:I compared to the non-C:I control (

Table 3, bottom 3 rows). The failures included 3 attempts containing 15±5 mg of pollen, and 1 attempt containing 125±25 mg pollen (

Table 3, bottom 3 rows). Each attempt had 16 total samples, resulting in 8 replicate +/-C:I sample pairs. Here, the paired-replicate data can be used to provide further insight to the observed trends (

Table 2). Specifically for the 15±5 mg samples treated for a long lysis duration (15-Long) where final DNA yields were not significantly different between the +/- C:I treatments. Here, final DNA yields were numerically greater for 10 of 16 sample pairs across both trials when C:I was added (

Table 2). In other words, the trend of C:I being beneficial was upheld. Similarly, for the 15±5 mg samples treated for a short lysis duration (15-Short), in Trial 2, 2 out of 8 sample pairs showed final DNA yields that were numerically greater when treated with C:I (

Table 2). The remaining pairs had undetectable DNA yields, annotated by 0 (

Table 2), perhaps due to biological factors that could not be overcome with C:I (e.g.

, senescing pollen). Similarly, amongst 125-Short Trial 1 samples that showed no significant difference between the +/-C:I treatments, 5 out of the 8 sample pairs in this category produced final DNA yields that were greater when C:I was added. Collectively, these findings indicate that samples treated with +C:I show a trend towards higher DNA yields than their non-C:I treated counterparts.

With respect to pollen DNA yield improvement observed with C:I, prior pollen DNA isolation studies have used chloroform containing reagents but without a non-chloroform control, making it difficult to evaluate the efficacy of this purification step. For example, 100 mg of maize pollen treated with chloroform has been reported to produce final yields of 1,200-2,500 ng of DNA [

38], which is comparable to the optimized yields reported here. In contrast, other studies that employed chloroform containing reagents obtained higher DNA yields using 50-200 mg of pollen, but pollen sources were variable, derived from trees [

32], opium poppy [

34], and bees and honey [

33,

37,

45]. Omelchenko et al., extracted pollen DNA from two Poaceae plants using less than 10 mg of pollen, but absolute yields could not be determined as the elution volume was not reported [

43]. Notably, all studies that used chloroform-based cleaning steps were coupled with a traditional CTAB based extraction protocol (

Table 1) in the absence of the later availability of commercial kits containing DNA purification columns. Our results suggest that this old chemical purification method, used universally across organisms and tissues, not only pollen, may have been especially beneficial to DNA isolation from pollen.

In terms of the reason why the addition of the C:I post-lysis step benefits pollen DNA yields in conjunction with a commercial kit, as shown in this study, one possibility is that C:I positively influences DNA binding to the column matrix and subsequent washing. The observed trend that DNA concentrations in the post-C:I treatment filtrate were lower compared to the non-C:I controls suggests that C:I causes an initial loss in DNA likely by DNA sequestration in the chloroform fraction. However, the overall greater final DNA yields in +C:I samples indicates improved DNA recovery after treatment. Additional research is required to test the extent of the effect of C:I on DNA purification, specifically at the level of the column matrix to quantify whether more DNA is lost during the washing steps in the absence of C:I compared to C:I added samples.

Several prior studies have compared commercial kits that do not include chloroform-containing reagents to isolate pollen DNA. The study by Swenson and Gemeinholzer reported a presumptive average yield of 65-75 ng DNA, starting with 10,000 pollen grains of maize [

36]. These yields are less than half the amount obtained here with 15±5 mg pollen. Bell et al., showed maize pollen DNA yields ranging from undetectable levels to 5,504 ng DNA when starting with 1 million pollen grains, with an approximate yield of 1,216 ng DNA across 3 replicates [

39], comparable to the yields obtained in the present study with 125±25 mg pollen. Other protocols using commercial kits generated relatively less [

41] or more [

2,

42,

44] final DNA yields than described here, however these studies vary in the pollen quantity and plant species source used, bead type parameters, reagents used, etc., making final DNA yields difficult to compare comprehensively.

3.4. Optimal Lysis Duration Is Dependent on Starting Pollen Quantity

The second most significant contribution of this study was demonstrating, using post-lysis C:I, that DNA could be successfully extracted from a nearly 10-fold range in the starting pollen quantity (125±25 mg and 15±5 mg). Prior studies have used quantities of 50-200 mg or more [

32,

34,

37,

38,

44] as well as smaller quantities of 10 mg or less [

36,

38,

42], but only a single study examined this parameter systematically using dilutions [

43]. That study found about 150,000 grains of pollen from two Poaceae species yielded 14.7±0.7 ng/µl, whereas 10,000 grains of pollen yielded 1.07±0.12 ng/µl, although total DNA yields could not be determined, as DNA pellet resuspension volume was not reported [

43]. Additionally, Swensen and Gemeinholzer tested 15 pollen species and pollen mixes, to conclude that an increase in pollen quantity from 10,000 to 100,000 grains would improve DNA yields of both synthetic and single communities of pollen samples [

36]. Taken together with our results, 10-15 mg of pollen may be a reliable starting point if attempting pollen DNA isolations for the first time on untested sample types, as it is likely that DNA yields will be quantifiable and will permit further troubleshooting of protocol parameters. Having a reliable protocol that permits smaller quantities of starter pollen to be used is highly advantageous because of the biological constraints of some plant species that are unable to shed copious amounts of collectable pollen. It is possible that the protocol outlined here may be capable of producing detectable DNA yields with less than 15±5 mg pollen due to the addition of chloroform:isoamyl alcohol, although this must be verified experimentally.

This study showed that optimal lysis duration is dependent on pollen quantity, where the 15±5 mg pollen samples showed trends for improved final DNA yields with a shorter lysis duration, and the 125±25 mg pollen showed significant improvement in final DNA yields with the longer duration (

Table 4). Our finding that lysis duration is dependent on pollen quantity is consistent with prior studies. For most pollen samples reported that were 50 mg or less, researchers used total lysis durations of around 2 min [

32,

36,

42], although other pollen and honey-containing pollen samples were lysed or processed for upwards of 5 min in the literature [

33,

37,

43,

44,

45]. Swenson and Gemeinholzer observed that 114 s was the optimal duration for pollen rupture of a 10,000-pollen grain sample of Z. mays using larger sized beads, as opposed to the presumptive mean of 304.3 s [

36]. Similarly, in the present study, for samples containing 15±5 mg pollen, optimal lysis was observed at 70 seconds compared to 6 min. An area of further study may be to increase lysis duration from 70 s to 114 s to determine if DNA yields increase as reported [

36].

For pollen or honey-containing pollen samples of 100 mg or greater, most mechanical lysis durations ranged between 1 min to 3 min using a bead mill or vortex [

38,

39,

40,

45]. Other methods have included manual mechanical lysis using mortar-pestles [

34], omitting this step completely [

2] or by thermomixer for 30 min [

37] to 3 h [

44], although the pollen amount used by the latter, must be inferred as only honey amount was reported at 50 g. Notably, the 3 min lysis duration employed by Bell et al., was applied to a 1 million maize pollen grain sample for an absolute yield of 1,216 ng DNA (15.2 ng/µl eluted in 80 µl) [

39]. Since comparable yields were obtained in this study, a reduction in lysis duration from 6 min to 3 min for 125±25 mg pollen samples may be an interesting parameter to test, since one may opt for a shorter lysis duration to prevent shearing of liberated DNA.

Regarding the lysis of larger pollen quantities, the short duration lysis treatment (125-Short) tested in this study showed some discrepancies. Although Trial 1 DNA yields were relatively unremarkable, several Trial 2 samples generated undetectable DNA yields when sampled at the post-lysis and post-treatment filtrate quantification steps, including both the +/-C:I treatments, which was inconsistent with the corresponding final DNA yields for those samples (

Table 2). Different pollen samples were used between Trials 1 and 2 which may partially explain the trial-to-trial inconsistencies observed, as maize pollen has the potential to harbor high levels of reactive phenolics and flavonoids, as well as other phytochemicals [

50]. These compounds could potentially interfere in the intercalation process by the Qubit dye for DNA quantification. Since these inconsistencies were not observed in the long duration lysis treatment (125-Long), it may also indicate that a larger pollen quantity coupled with a longer lysis duration may help to resolve this issue.

3.5. The Importance of Lysis Bead Type

Finally, our finding that larger lysis beads increase pollen DNA yields is consistent with prior studies. Swensen and Gemeinholzer lysed samples with 1.4 mm or 2.8 mm diameter ceramic beads, or 5 mm diameter steel beads [

36], while Bell et al., utilized a mixture of beads and materials: 1.4 mm ceramic, 0.1 mm silica, and 4 mm glass beads, known as the Lysing Matrix E from the FastDNA

® SPIN Kit for Soil [

39]. Both studies generated high DNA yields from pollen samples, despite the discrepancy in pollen amounts used (

Table 1). Regarding bead material, these studies demonstrate that incorporating beads larger than 1.4 mm and made of harder materials such as ceramic or steel, are beneficial with respect to breaking down the pollen exine more efficiently. In addition, an assortment of bead sizes and materials simultaneously may help to lyse multi-species pollen mixes to accommodate for varying morphological traits and exine compositions [

51].

4. Materials and Methods

Systematic Review of Published Pollen DNA Isolation Optimization Studies

Systematic literature searches were conducted to identify protocol parameters that significantly improved final DNA yields and to reveal methodological gaps. Different combinations of the following search terms were used in the academic search engines, Web of Science and PubMed: “pollen”, “DNA”, “isolat*”, “extract*”, “method*”, “metabarcod*”. These terms were used to search against publication titles, abstracts or both, and were restricted to studies that provided final DNA yields after extraction. Furthermore, studies that utilized trace quantities of starting pollen for environmental DNA sampling were excluded as atypical for experimental plant biology research. However, if the same publication evaluated pure or mixed pollen samples containing larger quantities of starting pollen, these findings were assessed.

Plant Material and Harvesting

For pollen DNA isolations, Zea mays ssp. mays (maize) pollen was used. Pollen samples #4, 8, 20, and 25 were collected in 2019 from greenhouse grown plants, and sample #295 was collected in the summer of 2021 from field maize grown at the Elora Research Station, University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada. For microbiome analysis, LH82 inbred pollen was collected from field-grown maize at the Elora Research Station independently during the summers of 2021 and 2022. The afternoon before pollen collection, paper bags were used to cover tassels and securely stapled in place. After collection the following morning, anthers, insects, and other debris were removed. LH82 pollen used for microbiome analyses was collected from a pool of plants 13-19 for Trial 1 and plants 7-11 for Trial 2. Cleaned pollen samples were stored in cryogenic vials at -80°C.

DNA Isolation Treatments

There were four categories of treatments tested: pollen weight, lysis duration, +/- post-lysis chloroform:isoamyl alcohol, bead type, and for each treatment there were eight replicates and two independent trials. First, pollen DNA isolation with chloroform:isoamyl alcohol 24:1 v/v (C:I) was tested using two amounts of maize pollen: 15±5 mg and 125±25 mg. The ZymoBIOMICSTM DNA Miniprep Kit (#D4300, Cedarlane Labs, Burlington, Ontario, CA) was used to extract DNA according to the manufacturer’s protocol with modifications (

Figure 1). Briefly, tubes were prepared with 0.5 g x 0.5 mm sterile glass beads (#Z250465-1PAK, Sigma Aldrich, Oakville, Ontario, CA) and chilled for at least 5 min before adding 750 µl ZymoBIOMICSTM Lysis Buffer. Pollen samples were added to each tube and agitated well before homogenization using the FisherbrandTM Bead Mill 24 Homogenizer (Thermo-Fisher, USA). Second, lysis duration was tested in combination with the two sample amounts mentioned above. The Short (conservative) lysis duration settings were: Speed (m/s) = 4.5, Time = 70 s, Cycle(s) = 1, Dwell = 1 min (total duration 70 s). The Long (aggressive) lysis duration settings were: Speed (m/s) = 5, Time = 1 min, Cycle(s) = 6, Dwell = 1 min (total duration 6 min). Notably, the Dwell setting defines the rest period after the specified duration of Time, for the total number of Cycles. Samples were centrifuged at 16,000 x g for 3 min before adding 750 µl C:I (#C0549-1PT, Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, Ontario, Canada). Tubes were placed in an orbital shaker at 100 rpm, room temperature for 10 min, then centrifuged at 5,500 x g for 15 min. A fresh tube was used to aliquot 500-600 µl of the aqueous phase and an equal volume of C:I was added. The previous shaking and centrifugation steps were repeated a second time. Then, 400 µl of the aqueous phase was transferred to a Zymo-Spin™ III-F Filter, centrifuged at 8,000 x g for 1 min. Untreated samples did not receive C:I; instead, after the lysate was centrifuged, 400 µl of the supernatant was transferred directly to the Zymo-Spin™ III-F Filter. The remaining steps were carried out as specified in the manufacturer’s protocol. For 15±5 mg and 125±25 mg pollen of sample used, 50 µl and 100 µl was eluted, respectively. The column matrix was incubated at room temperature for 4 min before centrifugation.

To observe the effect of bead type on lysis efficiency, two bead types were tested using the optimized C:I protocol. The 0.5 g x 0.5 mm sterile glass beads were compared to 3 x 2.8 mm ceramic beads (#15340160, Fisher Scientific, Ottawa, Ontario, CA) as previously tested [

36], using the best performing sample amounts and bead mill setting combinations: 1) 15±5 mg/70 s and 2) 125±25 mg/6 min. For the latter, the ceramic beads ruptured the plastic tube caps, resulting in the reduction of the bead mill setting from Speed = 5 to Speed = 4 for both ceramic and glass bead samples. Pollen DNA was isolated in replicates of eight and repeated two times, independently. Pollen DNA used for microbiome analyses were isolated in replicates of 10 for each of the two independent trials.

DNA Quantification

Pollen DNA was quantified using a Qubit v1.2 fluorometer (#Q32857, Molecular Probes, Invitrogen by Life Technologies) and dsDNA BR Assay Kit (#Q32853, Fisher Scientific, Ottawa, Ontario, CA). For C:I optimization, DNA concentrations were sampled three times during the isolation procedure: post-lysis, post-treatment, and after the final elution (

Figure 1). Post-lysis and post-treatment samples for Qubit DNA quantification were prepared at a ratio of 1:40 (5 µl in 200 µl total sample). Final elution Qubit samples were prepared at a ratio of 1:10 (20 µl in 200 µl total sample). Bead size samples were DNA quantified post-lysis and final elution only. DNA concentrations (ng/µl) were converted to absolute amounts by multiplying by lysis volume (750 µl), post-treatment volume (400-500µl) and/or final elution volume (50 µl or 100 µl) as relevant.

Full-Length 16S rRNA Gene PacBio Sequel II Sequencing

Pollen DNA samples were shipped to Integrated Microbiome Resource (IMR) at Dalhousie University (Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada) for full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing using the Pacific Bioscience (PacBio) single-molecule real-time (SMRT)-Cell Sequel II system at 2X depth (maximum of 100k reads/sample). Library preparation was conducted with the Express Template Kit (TPK) 2.0 as described [

52,

53]. Briefly, DNA was PCR amplified using high-fidelity Phusion Plus polymerase. The full-length 16S rRNA primers 27F-5’- AGRGTTYGATYMTGGCTCAG-3’ and 1492R-5’-RGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3’ were combined with PacBio barcodes to generate fusion primers. PCR products were visualized on a Coastal Genomics Analytical gel. Same sample PCR reactions were pooled, cleaned and normalized using the Charm Biotech Just-a-Plate 96-well Normalization kit. Up to 190 samples were pooled to form one library and were fluorometrically quantified prior to sequencing. PacBio Sequel II sequencing platform was conducted using 8M chips, resulting in an approximately 240-320 Gb output.

Data Analysis

Statistical analysis of pollen DNA isolation data: Data were analyzed in GraphPad Prism version 9.5.1 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California USA). Absolute amounts of DNA in replicates of eight per group were inputted as column data tables and reported as median values. To analyze the effect of post-lysis cleaning using C:I on DNA yields under different pollen quantity and lysis duration conditions, a Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test was conducted. Where values in the same row were identical, such as ties or values of zero, Pratts method was applied in GraphPad. The same test was used to analyze the effect of bead type on DNA yields under optimal pollen quantity and lysis duration combinations. The effect of lysis duration on DNA yields was assessed under different pollen quantity and lysis duration conditions, using a Mann-Whitney U test. Significance levels of P≤0.05 and P≤0.10 were reported.

Computational analysis of pollen microbiome data: The received FASTQ files were processed using the DADA2 R package (1.30.0) to infer amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) [

54]. Sequences corresponding to the 27F and 1492R primers were removed using the removePrimers function. Reads were filtered and trimmed using the filterAndTRim function (nops, filts, minQ=3, minLen=1300, maxLen=1600, maxN=0, rm.phix=FALSE, maxEE=2). To assign ASVs, pseudo-pooling was used, and singletons were ignored. The removeBimeraDenovo function was used to remove chimeras, then species level taxonomy was assigned using the assignTaxonomy function, applied on the silva_nr99_v138.1_wSpecies_train_set.fa.gz with minBoot = 80 training set. Using the phyloseq (1.46.0) R package [

55], a phyloseq object was generated comprised of the ASVs, taxonomy and metadata table. All mitochondrial and chloroplast taxonomic assignments were removed from the phyloseq object. The Biostrings (2.70.1) [

56] was used for biological strings manipulation. dplyr (1.1.4) [

57] and tidyverse (2.0.0) [

58] were used for further data processing in R studio. In command line, extracted ASVs reads were aligned using MUSCLE (3.8.1551) [

59] and the phylogenetic tree was generated using RAxML-NG (1.2.2 )(released on 11.04.2024 by The Exelixis Lab [

60]. The phylogenetic tree was uploaded to iTOL online platform [

61] for annotation and visualization.

5. Conclusions

Here, we have shown that chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (24:1) is a relatively simple and cost effective reagent to utilize for post-lysis cleaning during pollen DNA extraction in conjunction with a commercial DNA isolation kit. Its addition has been shown to minimize the amount of starting pollen while maximizing pollen DNA yields of high quality for further downstream analyses. Furthermore, based on these results and a systematic review of the literature, we propose that pollen DNA isolation protocols would benefit from combining approaches for optimization. Depending on the amount of starting pollen available, any one or more of the following parameters may be optimized during the working stages of protocol troubleshooting: lysis bead size and material, enzymes to aid in chemical lysis of pollen components, lysis duration, and the addition of C:I extraction as a post-lysis cleaning step. These parameters can be easily incorporated into any in-house or commercial kit protocol for a multitude of applications. The future implications of this study may include: (1) improved extraction of DNA from biologically realistic quantities of pollen (e.g., for forensics), thus removing the need for pollen pooling; and (2) establishing the beginnings of a standardized pollen DNA isolation protocol. This study also suggests future experiments: (1) to test whether a mixed composition of lysis bead sizes and materials is more effective for samples containing mixed pollen species; and (2) to examine how different morphological and chemical traits affect pollen DNA yields including varying exine composition, morphology, shape, macronutrient and phenolic content.

Author Contributions

AM, BJM and MNR: Conceptualization, Methodology; AM: Formal analysis; AM and BJM: Investigation; AM: Original draft preparation, Visualization; AM and EMK: Software; AM, EMK and MNR: Writing – reviewing and editing; MNR: Funding acquisition, Supervision.

Funding

Funding was provided by grants to M.N.R. from Grain Farmers of Ontario (054810), the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA 030356, 030564) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC 401424, 401663, 400924). The funders were not involved in the design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the report and decision to submit the article for publication.

Data Availability Statement

The microbiome datasets presented here have been submitted to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) online repository:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accession citation PRJNA1163389.

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this study to our cherished friend and colleague, Benjamin J. McFadyen, who passed away suddenly during the early preparation stage of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

- Bedinger, P. The Remarkable Biology of Pollen. Plant Cell 1992, 4, 879–887. [CrossRef]

- Pornon, A.; Escaravage, N.; Burrus, M.; Holota, H.; Khimoun, A.; Mariette, J.; Pellizzari, C.; Iribar, A.; Etienne, R.; Taberlet, P.; et al. Using Metabarcoding to Reveal and Quantify Plant-Pollinator Interactions. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 27282. [CrossRef]

- Bell, K.L.; Fowler, J.; Burgess, K.S.; Dobbs, E.K.; Gruenewald, D.; Lawley, B.; Morozumi, C.; Brosi, B.J. Applying Pollen DNA Metabarcoding to the Study of Plant–Pollinator Interactions. Applications in Plant Sciences 2017, 5, 1600124. [CrossRef]

- Dew, R.M.; McFrederick, Q.S.; Rehan, S.M. Diverse Diets with Consistent Core Microbiome in Wild Bee Pollen Provisions. Insects 2020, 11, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Kapheim, K.M.; Johnson, M.M.; Jolley, M. Composition and Acquisition of the Microbiome in Solitary, Ground-Nesting Alkali Bees. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 2993. [CrossRef]

- Klečka, J.; Mikát, M.; Koloušková, P.; Hadrava, J.; Straka, J. Individual-Level Specialisation and Interspecific Resource Partitioning in Bees Revealed by Pollen DNA Metabarcoding. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13671. [CrossRef]

- Chesters, D.; Liu, X.; Bell, K.L.; Orr, M.C.; Xie, T.; Zhou, Q.; Zhu, C. An Integrative Bioinformatics Pipeline Shows That Honeybee-Associated Microbiomes Are Driven Primarily by Pollen Composition. Insect Science 2022, 30, 555–568. [CrossRef]

- Carneiro de Melo Moura, C.; Setyaningsih, C.A.; Li, K.; Merk, M.S.; Schulze, S.; Raffiudin, R.; Grass, I.; Behling, H.; Tscharntke, T.; Westphal, C.; et al. Biomonitoring via DNA Metabarcoding and Light Microscopy of Bee Pollen in Rainforest Transformation Landscapes of Sumatra. BMC Ecology and Evolution 2022, 22, 51. [CrossRef]

- Santorelli, L.A.; Wilkinson, T.; Abdulmalik, R.; Rai, Y.; Creevey, C.J.; Huws, S.; Gutierrez-Merino, J. Beehives Possess Their Own Distinct Microbiomes. Environ Microbiome 2023, 18, 1. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, C.M.; Keeling, S.E.; Brewer, M.J.; Hathaway, S.C. Using Chemical and DNA Marker Analysis to Authenticate a High-Value Food, Manuka Honey. npj Science of Food 2018, 2, 9. [CrossRef]

- Pathiraja, D.; Cho, J.; Kim, J.; Choi, I.G. Metabarcoding of eDNA for Tracking the Floral and Geographical Origins of Bee Honey. Int Food Res J 2023, 164, 112413. [CrossRef]

- Kraaijeveld, K.; de Weger, L.A.; Ventayol García, M.; Buermans, H.; Frank, J.; Hiemstra, P.S.; den Dunnen, J.T. Efficient and Sensitive Identification and Quantification of Airborne Pollen Using Next-Generation DNA Sequencing. Molecular Ecology Resources 2015, 15, 8–16. [CrossRef]

- Ghitarrini, S.; Pierboni, E.; Rondini, C.; Tedeschini, E.; Tovo, G.R.; Frenguelli, G.; Albertini, E. New Biomolecular Tools for Aerobiological Monitoring: Identification of Major Allergenic Poaceae Species through Fast Real-Time PCR. Ecology and Evolution 2018, 8, 3996–4010. [CrossRef]

- Polling, M.; Sin, M.; de Weger, L.A.; Speksnijder, A.G.C.L.; Koenders, M.J.F.; de Boer, H.; Gravendeel, B. DNA Metabarcoding Using nrITS2 Provides Highly Qualitative and Quantitative Results for Airborne Pollen Monitoring. Sci Total Environ 2022, 806, 150468. [CrossRef]

- Westreich, L.R.; Westreich, S.T.; Tobin, P.C. Bacterial and Fungal Symbionts in Pollen Provisions of a Native Solitary Bee in Urban and Rural Environments. Microbial Ecology 2022, 86, 1416–1427. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.N.; Rehan, S.M. Wild Bee and Pollen Microbiomes across an Urban–Rural Divide. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 2023, 99, fiad158. [CrossRef]

- Bell, K.L.; De Vere, N.; Keller, A.; Richardson, R.T.; Gous, A.; Burgess, K.S.; Brosi, B.J. Pollen DNA Barcoding: Current Applications and Future Prospects. Genome 2016, 59, 629–640. [CrossRef]

- Parducci, L.; Bennett, K.D.; Ficetola, G.F.; Alsos, I.G.; Suyama, Y.; Wood, J.R.; Pedersen, M.W. Ancient Plant DNA in Lake Sediments. New Phytol 2017, 214, 924–942. [CrossRef]

- Wasti, Q.Z.; Sabar, M.F.; Farooq, A.; Khan, M.U. Stepping towards Pollen DNA Metabarcoding: A Breakthrough in Forensic Sciences. Forensic Science, Medicine, and Pathology 2023. [CrossRef]

- Obersteiner, A.; Gilles, S.; Frank, U.; Beck, I.; Häring, F.; Ernst, D.; Rothballer, M.; Hartmann, A.; Traidl-Hoffmann, C.; Schmid, M. Pollen-Associated Microbiome Correlates with Pollution Parameters and the Allergenicity of Pollen. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0149545. [CrossRef]

- Manirajan, B.A.; Ratering, S.; Cardinale, M.; Maisinger, C.; Schnell, S. The Microbiome of Flower Pollen and Its Potential Impact on Pollen-Related Allergies. Old Herborn University Seminar Monograph 2019, 33, 65–72.

- Manirajan, B.A.; Maisinger, C.; Ratering, S.; Rusch, V.; Schwiertz, A.; Cardinale, M.; Schnell, S. Diversity, Specificity, Co-Occurrence and Hub Taxa of the Bacterial-Fungal Pollen Microbiome. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 2018, 94, fiy112. [CrossRef]

- Manirajan, B.; Ratering, S.; Rusch, V.; Schwiertz, A.; Geissler-Plaum, R.; Cardinale, M.; Schnell, S. Bacterial Microbiota Associated with Flower Pollen Is Influenced by Pollination Type, and Shows a High Degree of Diversity and Species-Specificity. Environmental Microbiology 2016, 18, 5161–5174. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Jeon, C.W.; Cho, G.; Kim, D.R.; Kwack, Y.B.; Kwak, Y.S. Comparison of Microbial Community Structure in Kiwifruit Pollens. Plant Pathology Journal 2018, 34, 143–149. [CrossRef]

- Compant, S.; Cambon, M.C.; Vacher, C.; Mitter, B.; Samad, A.; Sessitsch, A. The Plant Endosphere World – Bacterial Life within Plants. Environmental Microbiology 2020, 23, 1812–1829. [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, E.M.; Shrestha, A.; Reid, M.; McFadyen, B.J.; Raizada, M.N. Conservation and Diversity of the Pollen Microbiome of Pan-American Maize Using PacBio and MiSeq. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14, 1276241. [CrossRef]

- Quilichini, T.D.; Grienenberger, E.; Douglas, C.J. The Biosynthesis, Composition and Assembly of the Outer Pollen Wall: A Tough Case to Crack. Phytochem 2015, 113, 170–182. [CrossRef]

- Althiab-Almasaud, R.; Teyssier, E.; Chervin, C.; Johnson, M.A.; Mollet, J.C. Pollen Viability, Longevity, and Function in Angiosperms: Key Drivers and Prospects for Improvement. Plant Reproduction 2023, 37, 273–293. [CrossRef]

- Ariizumi, T.; Toriyama, K. Genetic Regulation of Sporopollenin Synthesis and Pollen Exine Development. Annual Review of Plant Biology 2011, 62, 437–460. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Sun, M.; Xiong, T.; Ye, F.; Zhao, Z. Development and Genetic Regulation of Pollen Intine in Arabidopsis and Rice. Gene 2024, 893, 147936. [CrossRef]

- Grienenberger, E.; Quilichini, T.D. The Toughest Material in the Plant Kingdom: An Update on Sporopollenin. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12, 703864. [CrossRef]

- Simel, E.J.; Saidak, L.R.; Tuskan, G.A. Method of Extracting Genomic DNA from Non-Germinated Gymnosperm and Angiosperm Pollen. BioTechniques 1997, 22, 390–394. [CrossRef]

- Lalhmangaihi, R.; Ghatak, S.; Laha, R.; Gurusubramanian, G.; Senthil Kumar, N. Protocol for Optimal Quality and Quantity Pollen DNA Isolation from Honey Samples. J Biomol Tech 2014, 25, 92–95. [CrossRef]

- Kaˇnuková, S.; Mrkvová, M.; Mihálik, D.; Kraic, J. Procedures for DNA Extraction from Opium Poppy (Papaver Somniferum L.) and Poppy Seed-Containing Products. Foods 2020, 9, 1429. [CrossRef]

- Guertler, P.; Eicheldinger, A.; Muschler, P.; Goerlich, O.; Busch, U. Automated DNA Extraction from Pollen in Honey. Food Chemistry 2014, 149, 302–306. [CrossRef]

- Swenson, S.J.; Gemeinholzer, B. Testing the Effect of Pollen Exine Rupture on Metabarcoding with Illumina Sequencing. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245611. [CrossRef]

- Torricelli, M.; Pierboni, E.; Tovo, G.R.; Curcio, L.; Rondini, C. In-House Validation of a DNA Extraction Protocol from Honey and Bee Pollen and Analysis in Fast Real-Time PCR of Commercial Honey Samples Using a Knowledge-Based Approach. Food Analytical Methods 2016, 9, 3439–3450. [CrossRef]

- Folloni, S.; Kagkli, D.M.; Rajcevic, B.; Guimarães, N.C.C.; Van Droogenbroeck, B.; Valicente, F.H.; Van den Eede, G.; Van den Bulcke, M. Detection of Airborne Genetically Modified Maize Pollen by Real-Time PCR. Molecular Ecology Resources 2012, 12, 810–821. [CrossRef]

- Bell, K.L.; Burgess, K.S.; Botsch, J.C.; Dobbs, E.K.; Read, T.D.; Brosi, B.J. Quantitative and Qualitative Assessment of Pollen DNA Metabarcoding Using Constructed Species Mixtures. Molecular Ecology 2019, 28, 431–455. [CrossRef]

- Chavan, D.; Adolacion, J.R.T.; Crum, M.; Nandy, S.; Lee, K.H.; Vu, B.; Kourentzi, K.; Sabo, A.; Willson, R.C. Isolation and Barcoding of Trace Pollen-Free DNA for Authentication of Honey. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2022, 70, 14084–14095. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, B. Pollen Identification Using Sequencing Techniques, University of Skövde: Skövde, 2022.

- Leontidou, K.; Vernesi, C.; De Groeve, J.; Cristofolini, F.; Vokou, D.; Cristofori, A. DNA Metabarcoding of Airborne Pollen: New Protocols for Improved Taxonomic Identification of Environmental Samples. Aerobiologia 2018, 34, 63–74. [CrossRef]

- Omelchenko, D.O.; Krinitsina, A.A.; Kasianov, A.S.; Speranskaya, A.S.; Chesnokova, O.V.; Polevova, S.V.; Severova, E.E. Assessment of ITS1, ITS2, 5′-ETS, and trnL-F DNA Barcodes for Metabarcoding of Poaceae Pollen. Diversity 2022, 14, 191. [CrossRef]

- Soares, S.; Amaral, J.S.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P.; Mafra, I. Improving DNA Isolation from Honey for the Botanical Origin Identification. Food Control 2015, 48, 130–136. [CrossRef]

- Waiblinger, H.U.; Ohmenhaeuser, M.; Meissner, S.; Schillinger, M.; Pietsch, K.; Goerlich, O.; Mankertz, J.; Lieske, K.; Broll, H. In-House and Interlaboratory Validation of a Method for the Extraction of DNA from Pollen in Honey. J Verbr Lebensm. 2012, 7, 243–254. [CrossRef]

- Dairawan, M.; Shetty, P.J. The Evolution of DNA Extraction Methods. American Journal of Biomedical Science & Research 2020, 8, 39–45. [CrossRef]

- Kiesselbach, T.A. The Structure and Reproduction of Corn (50th Anniversary Ed.). Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press 1999.

- OECD/FAO OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2023-2032; OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook; OECD Publishing: Paris, 2023; ISBN 978-92-64-61933-3.

- Payne, W.W. Structure and Function in Angiosperm Pollen Wall Evolution. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 1981, 35, 39–59. [CrossRef]

- Bujang, J.S.; Zakaria, M.H.; Ramaiya, S.D. Chemical Constituents and Phytochemical Properties of Floral Maize Pollen. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247327. [CrossRef]

- Prudnikow, L.; Pannicke, B.; Wünschiers, R. A Primer on Pollen Assignment by Nanopore-Based DNA Sequencing. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2023, 11, 1112929. [CrossRef]

- Comeau, A.; Douglas, G.; Langille, M. Integrated Microbiome Research (IMR): Protocols Available online: https://imr.bio/protocols.html (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Comeau, A.M.; Filloramo, G.V. Preparing Multiplexed 16S/18S/ITS Amplicon SMRTbell Libraries with the Express TPK2.0 for the PacBio Sequel2 V.1. protocols.io 2023. [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-Resolution Sample Inference from Illumina Amplicon Data. Nature Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [CrossRef]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. Phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [CrossRef]

- Pagès, H.; Aboyoun, P.; Gentleman, R.; DebRoy, S. Biostrings: Efficient Manipulation of Biological Strings. R Package Version 2.72.1 Available online: https://bioconductor.org/packages/Biostrings. (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Wickham, H.; François, R.; Henry, L.; Müller, K.; Vaughan, D. Dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. R Package Version 1.1.4 Available online: https://dplyr.tidyverse.org/.

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. Journal of Open Source Software 2019, 4, 1686. [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple Sequence Alignment with High Accuracy and High Throughput. Nucleic Acids Research 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, A.M.; Darriba, D.; Flouri, T.; Morel, B.; Stamatakis, A. RAxML-NG: A Fast, Scalable and User-Friendly Tool for Maximum Likelihood Phylogenetic Inference. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 4453–4455. [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v5: An Online Tool for Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49, W293–W296. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).