Submitted:

09 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

In the industrial context of Asaluyeh City, bested in Bushehr Province, in the southern coastal region of Iran, it is essential to interpret urban green spaces to promote social well-being. Accordingly, this case study identifies all public green spaces, parks, and related activities within these places to emphasize the importance of assessing the functionality and contribution of Side Park to the urban fabric. The objective of this article is to evaluate the performance of Asaluyeh City Side Park and to examine public attitudes toward its use and interactional significance. Additionally, this study examines the context of Asaluyeh City as a coastal strategic area with extensive industrial activities and surrounded by several huge refineries located on the edge of the city. The adverse environmental consequences of the stress of refineries and constraints on urban developments are of particular concern in this area. Particularly, the research highlights the necessity for a comprehensive assessment of the accessibility and role of Side Park in meeting the social needs of residents of Asaluyeh City. The methodology comprises a comprehensive examination of the urban environment of Asaluyeh City, direct observation of park users' behaviors and activities, and an evaluation of user satisfaction with the park's functionality. The findings contribute to the body of knowledge regarding the effective use of green public spaces in urban planning, particularly within the context of high levels of stress in industrial cities. Furthermore, this paper provides insights into enhancing social well-being through the presence of green public space, which can inform the enhancement of social well-being in the context of urban development.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Study Area

2. Methodology

2.1. Fieldwork and Park Selection

2.1.1. Mother Park (No.1)

2.1.2. Women’s Park (No.2)

2.1.3. Neighborhood Park (No.3)

2.1.4. Side Park (No.4)

- Easy Accessibility: The park should be situated in a convenient location with pathways and entrances accessible to all. This ensures that the park can be easily reached and navigated by all members of the community.

- Suitability for All Age Groups and Ethnicities: The park should offer a diverse range of amenities and facilities that appeal to a wide demographic, catering to the needs of children, young people, adults, and elderly visitors from various cultural and ethnic backgrounds. This might include multi-functional spaces, play areas, quiet zones, and cultural elements that reflect the community’s diversity.

- Popularity Among Citizens: As a frequently used public space, the park should feature facilities that encourage regular visits, thereby establishing it as a central hub for community gatherings and activities.

2.2. Survey

3. Result

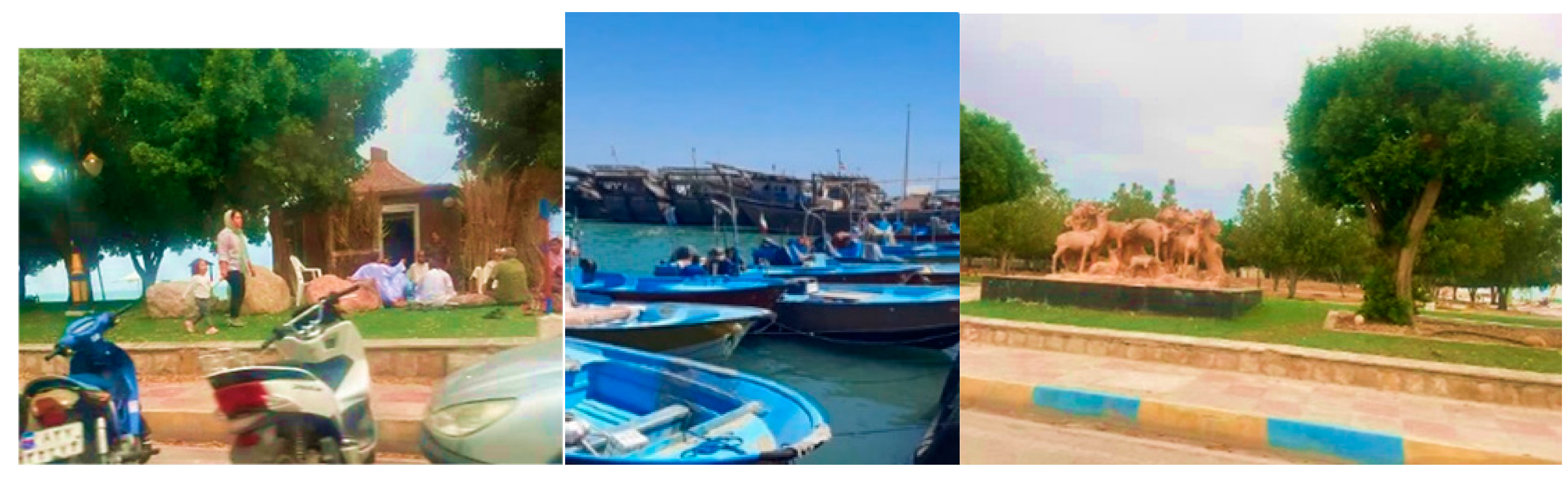

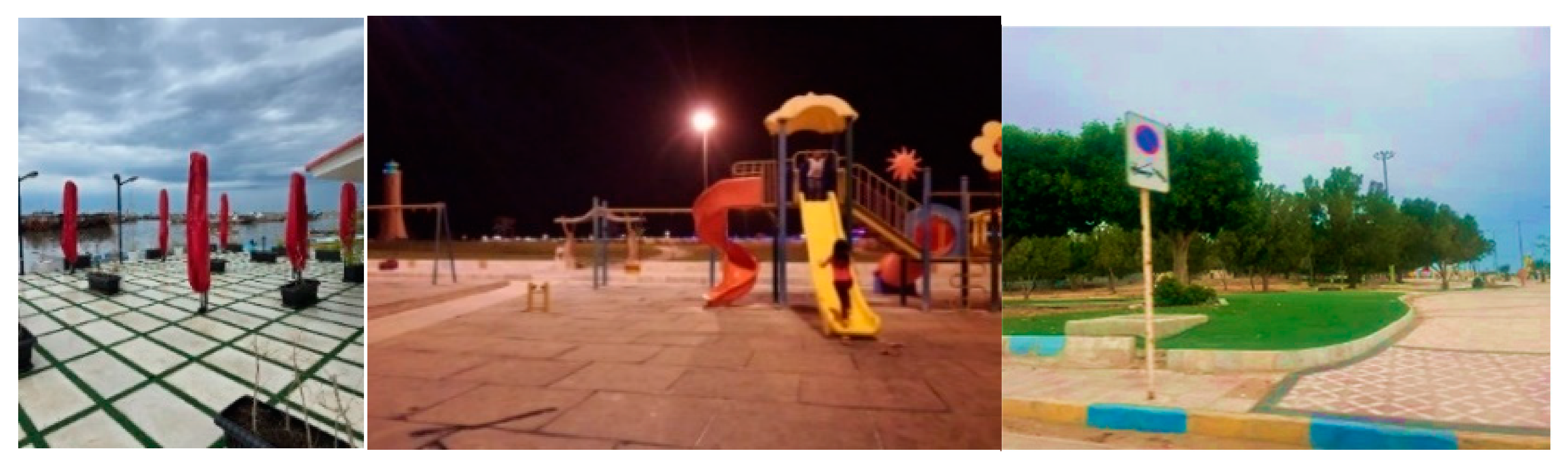

3.1. The Main Characteristics of Side Park of Asaluyeh

3.2. User’s Profile

3.2.1. Genders and Age

3.2.2. Financial Situation

- Housewives. In the context of Muslim culture, it is customary for women to be financially supported by their fathers prior to marriage, and after marriage, they are financially supported by their spouse. The average income of housewives is dependent on the income of the sponsor.

- Self-employed. Individuals are those who are self-employed or engage in entrepreneurial activities, and their income is not dependent on the provision of services by a government institution.

- Employee. whose income is linked to government institutions and is determined by factors such as working hours and compliance with labor security and social security regulations.

- The remaining category is classified as “other.” This category encompasses any occupation not encompassed by the aforementioned categories.

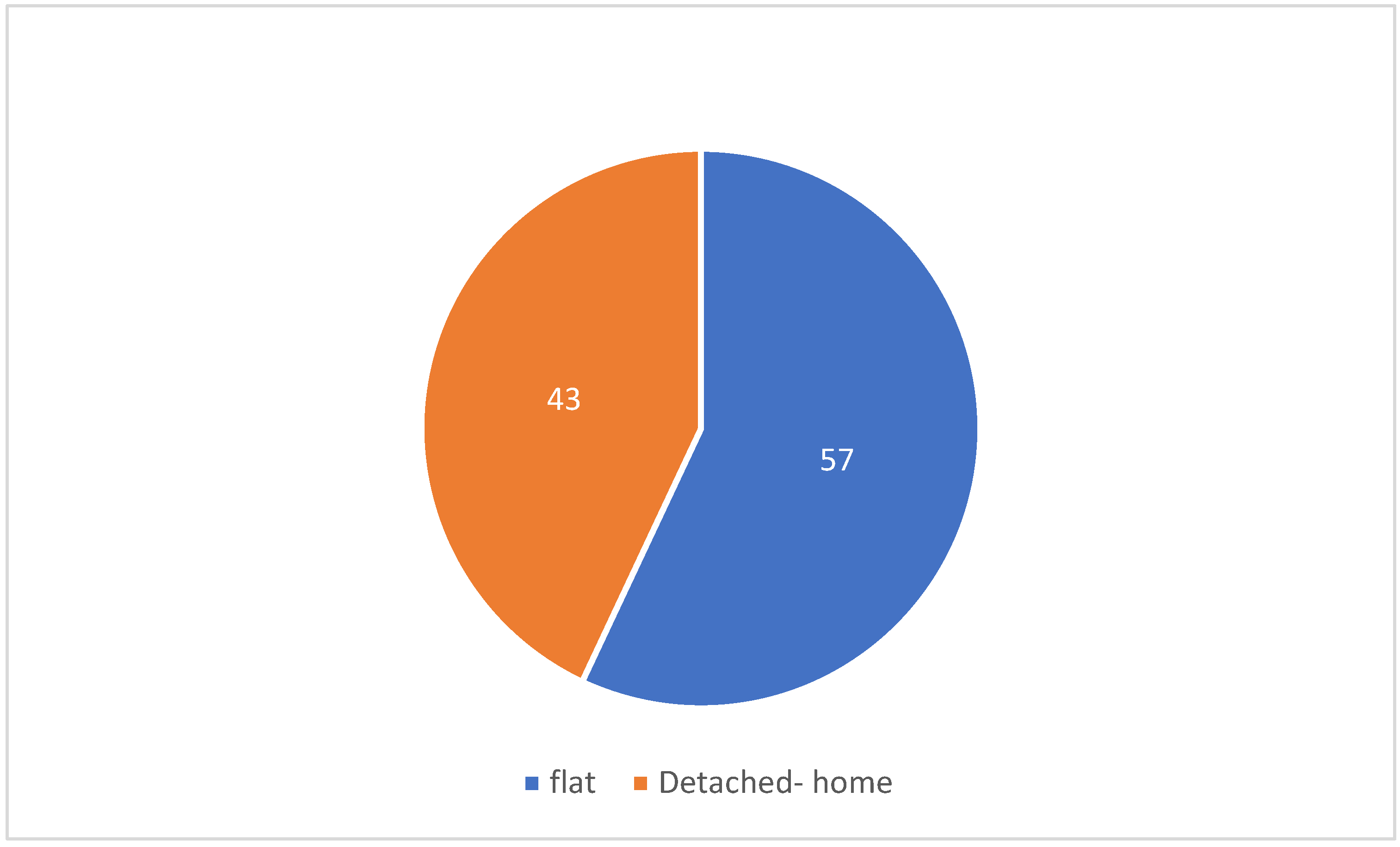

3.2.3. Housing

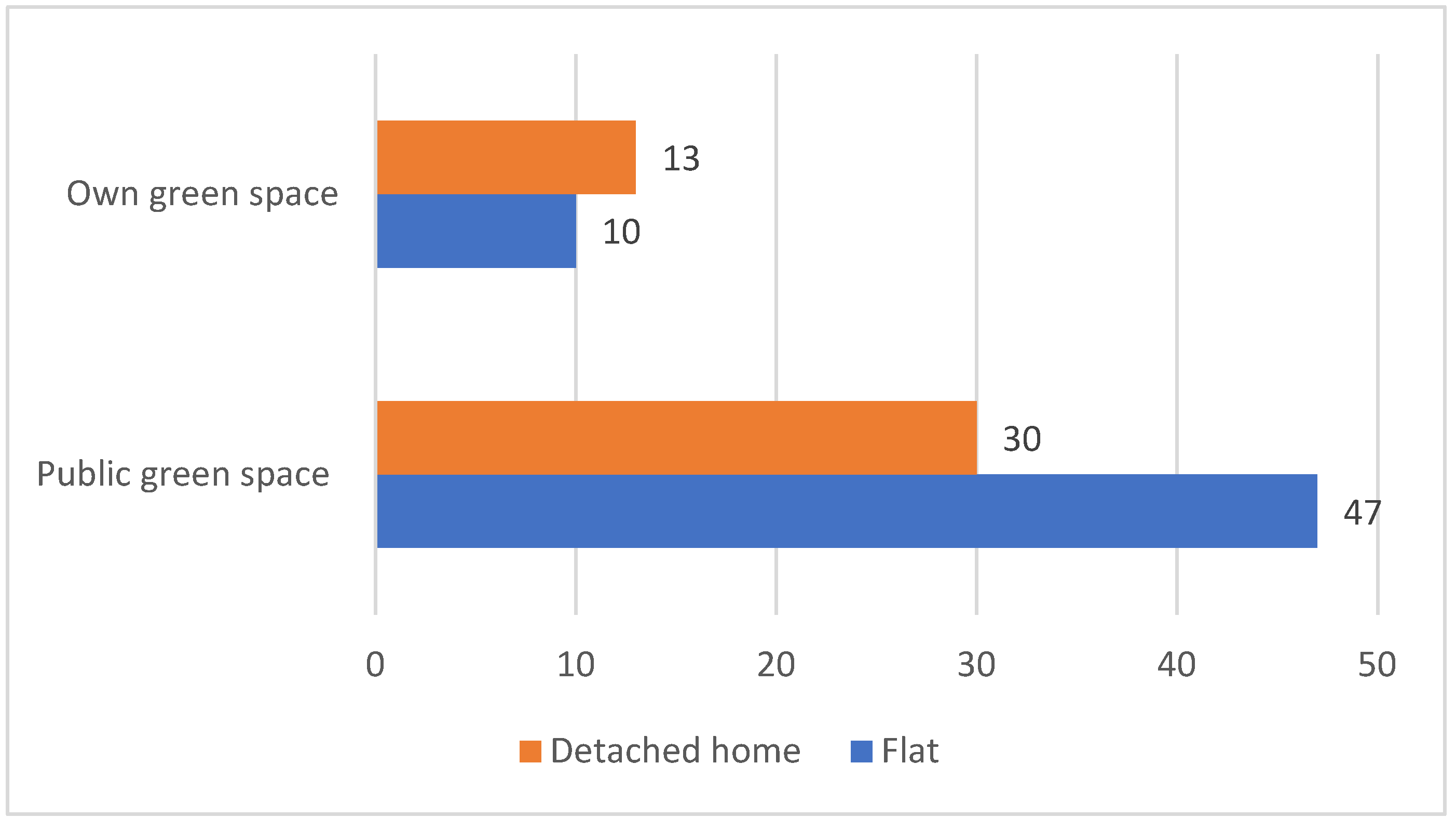

- Residents of detached homes have more purpose-driven visits to public green spaces, using them for community engagement or specific public green space activities.

- Residents of flats regard public green spaces as an integral extension of their living spaces and use them more regularly and for a more diverse range of activities. Thereby fulfilling their need for parks and public green spaces.

3.3. The Frequency of Use and Functionality in Side Park

3.3.1. Visiting Patterns

3.3.2. Time Pattern

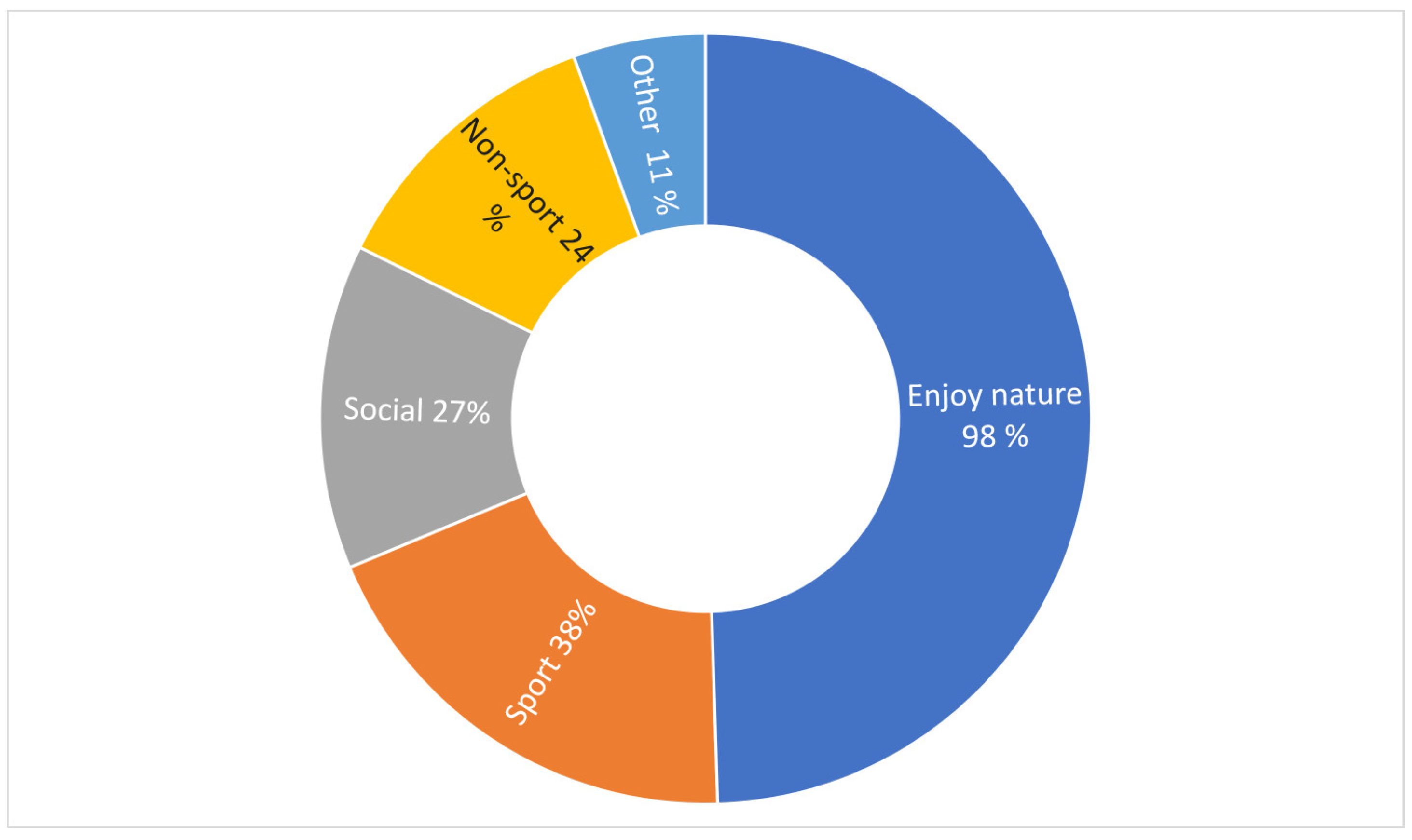

3.3.3. Activity Pattern

- Sports and Healthy Activities: All activities that facilitate human mobility. This category encompasses activities such as walking, team games, running, and cycling.

- Social activities (the purpose of sharing with others): activities that are conducted either individually or in group mode. As a result, the group converses with individuals, both those known to them and those who are not. This category encompasses activities such as board games, informal conversation, and any form of audio communication in which two or more individuals engage in face-to-face interaction.

- Non-sport activities: This section encompasses the time spent in public green spaces for leisure purposes. These activities may include playing with children, studying, picnicking, carrying a baby, or establishing a secure environment for children to play in.

- Other activities: include activities such as entertainment, reading (either books or newspapers), contemplation, relaxation, and the release of mental stress, fishing, and swimming.

- The natural environment and surrounding landscape are observed and enjoyable.

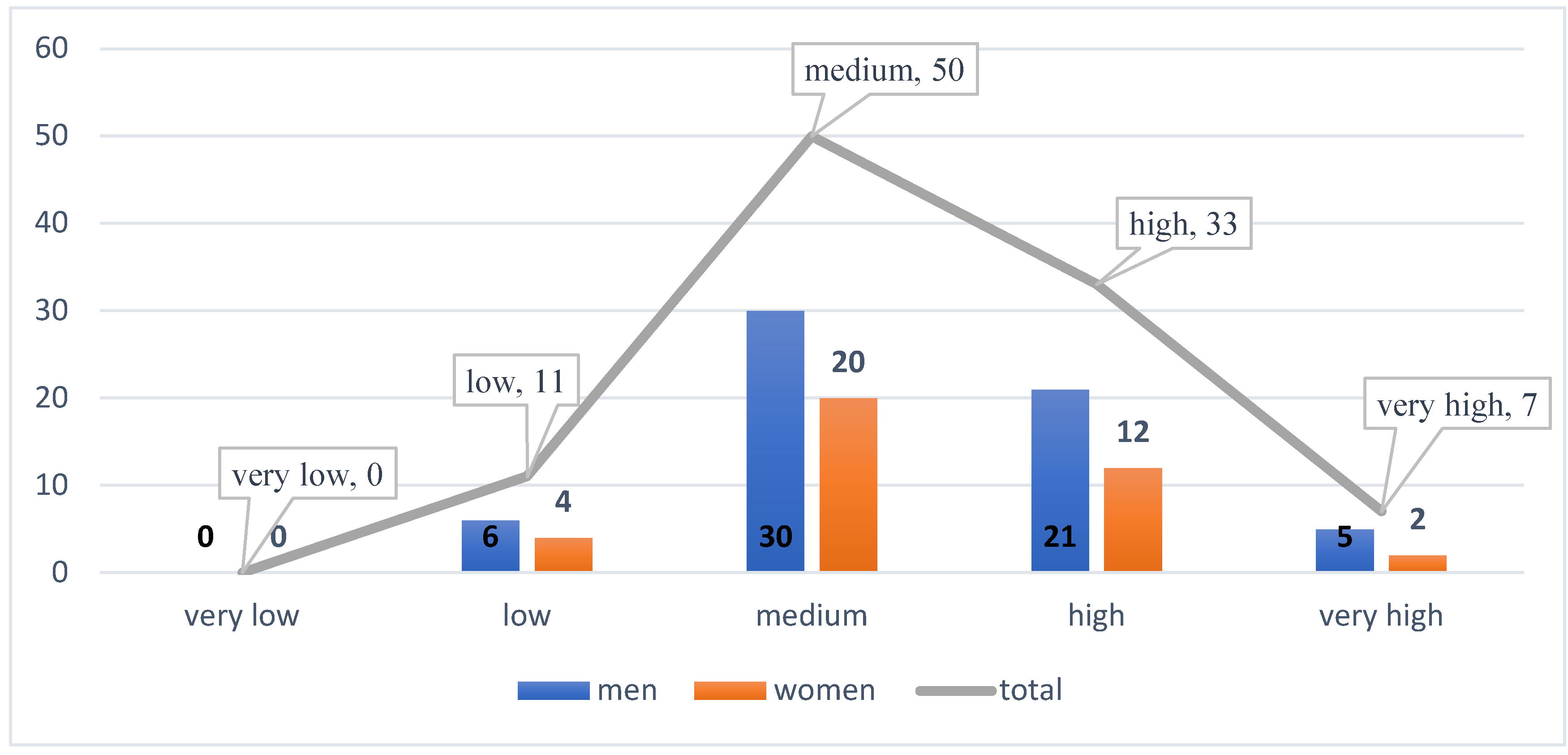

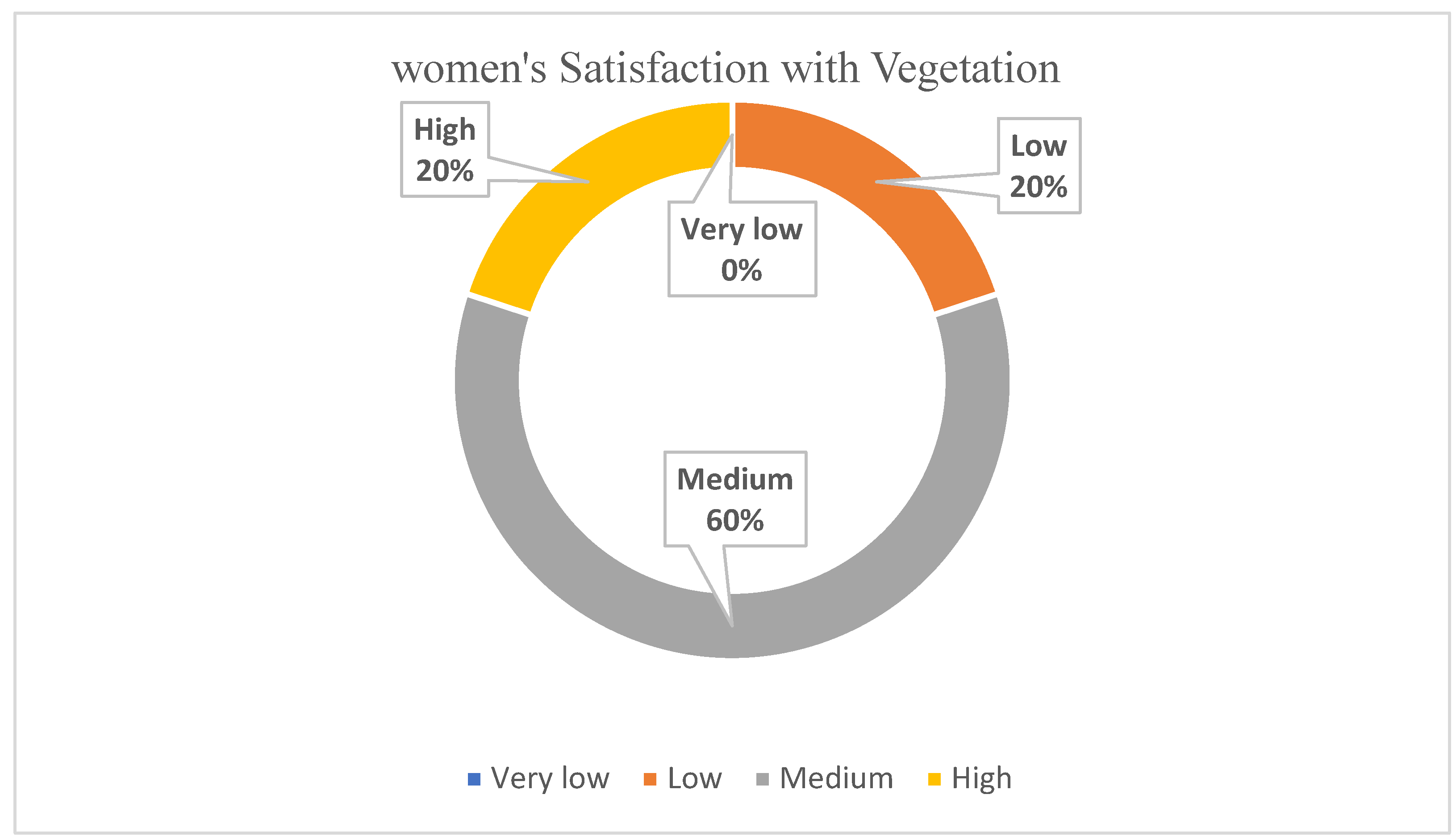

4. User Satisfactions

5. Discussion and Conclusion

- The Role of Side Park in Enhancing Well-Being: Side Park plays a pivotal role in enhancing the well-being of the local community. In an industrialized city like Asaluyeh, where many residents are involved in heavy industries, public green spaces like Side Park offer an essential respite. These spaces provide an accessible environment for physical activity, social interaction, and relaxation, addressing both the physical and mental health needs of the population. This adaptability ensures that Side Park is a dynamic space that serves the various lifestyles and preferences of the community.

- Multipurpose Design and Community Access: Side Park features diverse spaces and a multifunctional design, including football pitches, walking paths, a daily market, scenic landscapes, and zones for social interaction. This variety ensures that the park remains a valuable resource for individuals from all walks of life and could enhance community well-being in industrial urban settings. As a place where physical and mental well-being can thrive, the park encourages fostering social connections and community cohesion. It acts as a crucial counterbalance to the stresses of urban industrial life, providing a snug green environment where residents can relax and escape the demands of their daily routines. Consequently, Side Park is an essential component of the urban fabric, contributing to a healthier and more connected community.

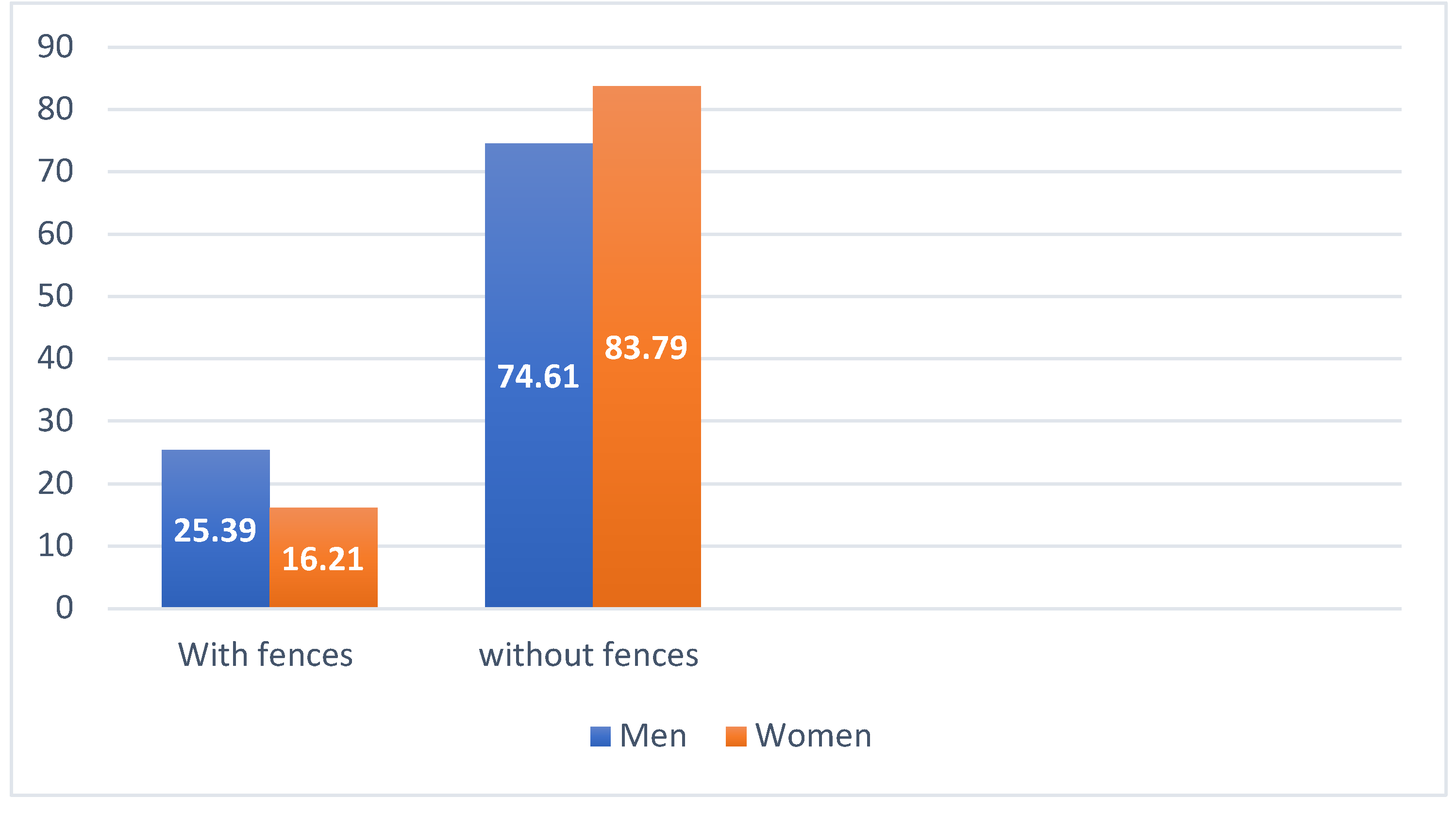

- Addressing Urban Challenges: the park’s lack of fencing has not compromised its safety. On the contrary, the open design has fostered a sense of freedom, and the positive perceptions of safety expressed by both men and women highlight the park’s success in creating a secure and welcoming space. The absence of the fences has not been detrimental, and it has contributed to a sense of openness, inclusivity, and community engagement. Despite the challenges posed by development restrictions of urban planning limitations, climate conditions, pollution from the refinery, and other urban issues, Side Park is an example of how the design of public green spaces can significantly enhance the quality of social life, improve public health, and strengthen social ties in industrial cities.

- A Vital Urban Asset: The demand for spaces that promote mental and physical health is particularly important in industrial cities like Asaluyeh, where residents often face high-stress environments. Side Park addresses these needs by creating opportunities for interaction and community engagement. This park plays a crucial role in supporting the holistic well-being of the community, enhancing both mental and physical health. Side Park fosters community cohesion, improves public health, and provides a venue for diverse recreational activities, making it an indispensable asset for Asaluyeh. It highlights the critical importance of well-designed, multifunctional public green spaces in industrial cities, which serve as vital tools for improving quality of life and strengthening social connections.

Acknowledgement

References

- Alabbas, W., and A. Polat. 2019. Comparative Analysis of Park User Preferences in Konya (Turkey) and Kirkuk (Iraq) Cities 9: 1128–1143. [CrossRef]

- Anbari, M., and L. Malaki. 2012. Investigating the social effects of industrial growth poles on local sustainable development (A case study of Asalouye Industrial Growth Pole). Local development (rural-urban) 3, 2: 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bahriny, F. 2021. Traditional versus Modern? Perceptions and Preferences of Urban Park Users in Iran. Sustainability. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/76501563/Traditional_versus_Modern_Perceptions_and_Preferences_of_Urban_Park_Users_in_Iran.

- Bennet, S. A., N. Yiannakoulias, A. M. Williams, and P. Kitchen. 2012. Playground Accessibility and Neighbourhood Social Interaction Among Parents. Social Indicators Research 108, 2: 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesura, A. 2004. The Role of Urban Parks for the Sustainable City. Landscape and Urban Planning 68: 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P., O. Potchter, and I. Schnell. 2014. A methodological approach to the environmental quantitative assessment of urban parks. Applied Geography 48: 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N. 2008. Does quality of the built environment affect social cohesion? Proceedings of The Ice-Urban Design and Planning 161: 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germann-Chiari, C., and K. Seeland. 2004. Are urban green spaces optimally distributed to act as places for social integration? Results of a geographical information system (GIS) approach for urban forestry research. Forest Policy and Economics 6, 1: 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaźmierczak, A. 2013. The contribution of local parks to neighbourhood social ties. Landscape and Urban Planning 109, 1: 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M., and W. Sullivan. 2001. Environment and Crime in the Inner City: Does Vegetation Reduce Crime? Environment and Behavior-ENVIRON BEHAV 33: 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyttä, M., A. Broberg, T. Tzoulas, and K. Snabb. 2013. Towards contextually sensitive urban densification: Location-based softGIS knowledge revealing perceived residential environmental quality. Landscape and Urban Planning 113: 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebach, J., and J. Gilliland. 2010. Child-Led Tours to Uncover Children’s Perceptions and Use of Neighborhood Environments. Children, Youth and Environments 20, 1: 52–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, S., and M. J. Koohsari. 2009. Analyzing Accessibility Dimension of Urban Quality of Life: Where Urban Designers Face Duality Between Subjective and Objective Reading of Place. Social Indicators Research 94, 3: 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn Karl, T. 2004. Oil-Led Development: Social, Political, and Economic Consequences. In Encyclopedia of Energy. Elsevier: pp. 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruthaveeran, S. 2017. Exploring the urban park use, preference and behaviours among the residents of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P., A. G. de Barros, L. Kattan, and S. C. Wirasinghe. 2016. Public transportation and sustainability: A review. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering 20, 3: 1076–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabavi, F., Y. Ahmad, and A. T. Goh. 2012. Daylight and Opening in Traditional Houses in Yazd, Iran. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, R. A., S. Ahmad, and A. Zain Ahmed. 2013. Physical Activity and Human Comfort Correlation in an Urban Park in Hot and Humid Conditions. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosratpour, D. 2012. Evaluation of Traditional Iranian Houses and Match it with Modern Housing. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Evaluation-of-Traditional-Iranian-Houses-and-Match-Nosratpour/f1671ffdf9aa94326d981bd57debe7937af3cc54.

- Paul, S., and H. Nagendra. 2017. Factors Influencing Perceptions and Use of Urban Nature: Surveys of Park Visitors in Delhi. Land 6, 2: 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakip, S. R. M., Mt Norizan, Siti Syamimi Akhir, and Oma. 2015. Determinant Factors of Successful Public Parks in Malaysia. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/11678252/Determinant_Factors_of_Successful_Public_Parks_in_Malaysia.

- Shu, S., L. Meng, X. Piao, X. Geng, and J. Tang. 2024. Effects of Audio–Visual Interaction on Physio-Psychological Recovery of Older Adults in Residential Public Space. Forests 15, 2: 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, N., A. Lak, and S. M. R. Moussavi.A. 2023. Green space and the health of the older adult during pandemics: A narrative review on the experience of COVID-19. Frontiers in Public Health 11: 1218091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolch, J. R., J. Byrne, and J. P. Newell. 2014. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: The challenge of making cities ‘just green enough. Landscape and Urban Planning 125: 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Population | Men | Women | Household |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 12.564 | 8.204 | 4.36 | 2.449 |

| 2020 | 15.346 | 11.684 | 3.662 | 3.334 |

| No. | Park Name | Map | Area | Function | Users | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mother Park |  |

151 m2 | Local Park | Child / men and women | 24 H |

| 2 | Women’s Park |  |

118 m2 | Special Park | Only women | Part time |

| 3 | Neighborhood Park |  |

365 m2 | Local Park | Child / men and women | 24 H |

| 4 | Side Park |  |

6176 m2 | Local Park | Child / men and women |

| Part One | User’s profile | 1 | Age: | |

| 2 | Gender | Male | ||

| Female | ||||

| Other | ||||

| 3 | Level of education: | |||

| 4 | Job | Housewife | ||

| Self-employee | ||||

| Employee | ||||

| Other | ||||

| 5 | Average income: | |||

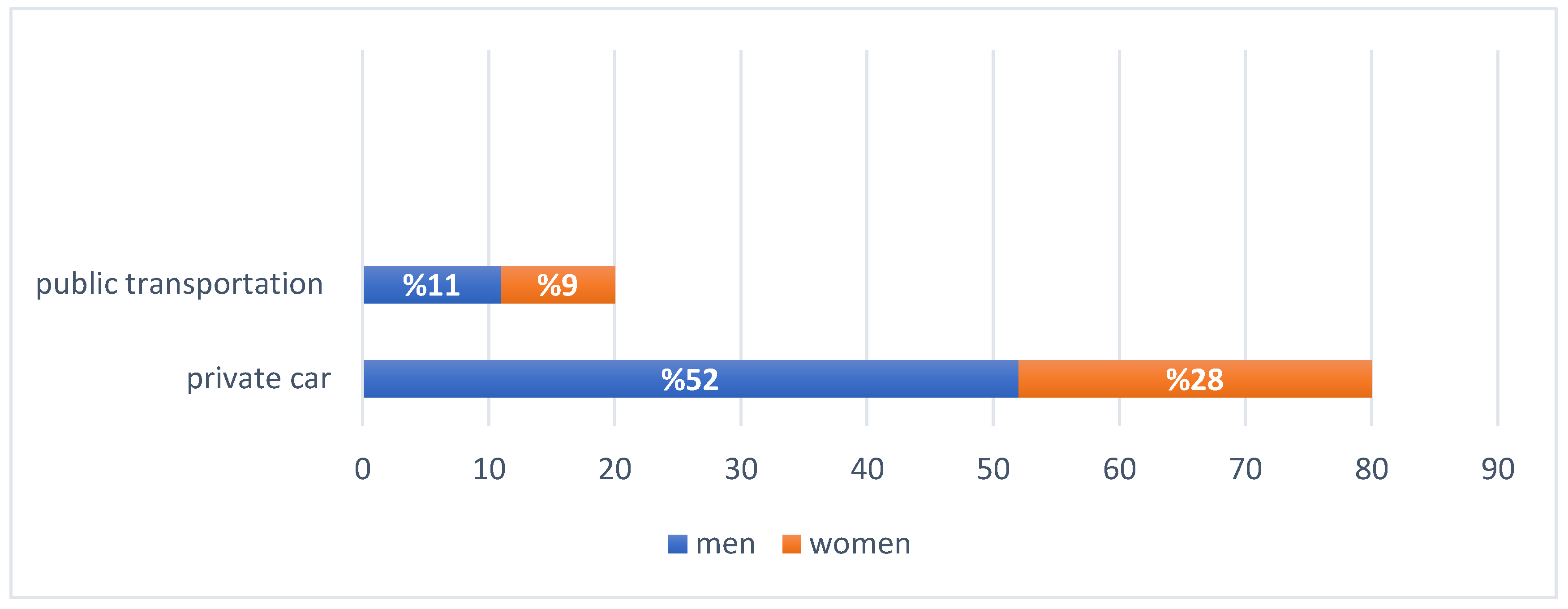

| 6 | Means of transport | Public transportation | ||

| Private car | ||||

| 7 | Kind of house | Flat | ||

| Detached-home | ||||

| 8 | Preferred places | Own green space | ||

| Public green space | ||||

| Part Two | Frequency and functionality of Side Park | 9 | Park visiting mode. | With a Group |

| Alone | ||||

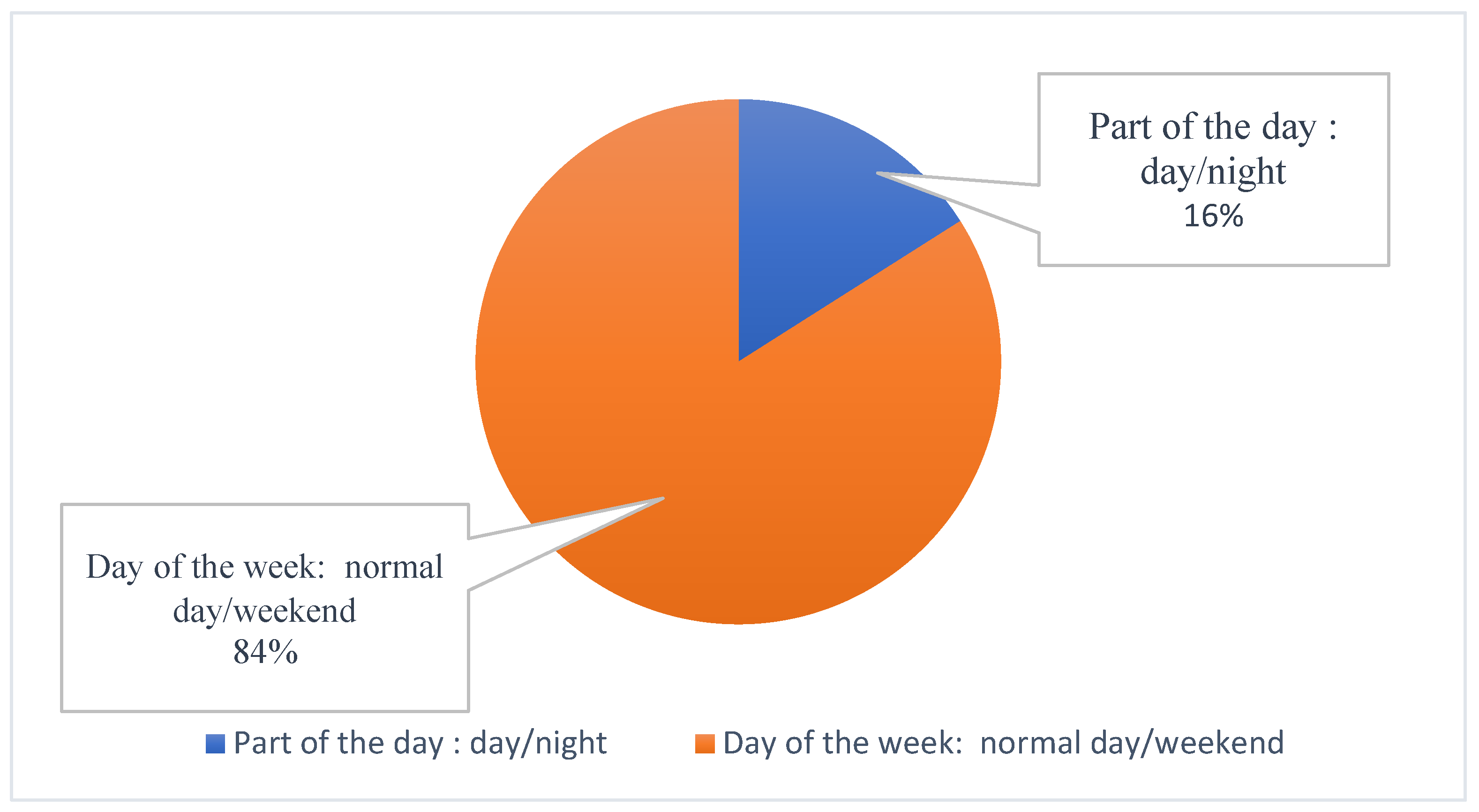

| 10 | Time frequency for visiting park | Part of the day: day/night | ||

| Day of the week: normal day/weekend | ||||

| 11 | Activities in side park | Sports | ||

| non-sport | ||||

| Interactive with others | ||||

| To see the landscapes | ||||

| Fishing or swimming | ||||

| Other activities | ||||

| Part Three | User’s satisfaction | 12 | Satisfaction with Side park | Non satisfaction |

| low | ||||

| Medium | ||||

| High | ||||

| Very High | ||||

| 13 | Why use another park, say the name. | Different design | ||

| Facilities | ||||

| Nearest | ||||

| Safety | ||||

| 14 | Satisfaction with plants and vegetation | Very low | ||

| Low | ||||

| Medium | ||||

| High | ||||

| Very high | ||||

| 15 | Which item is necessary. | Playground for child | ||

| Benches | ||||

| Shaded threes | ||||

| Pergola | ||||

| Other | ||||

| No. | Functionality | Picture | Length: (M) | Area: (M2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone 1 | Mini children Park. football pitch. Restaurant. green space |

|

215 | 710 |

| Zone 2 | Walking. green public space. |

|

800 | 1567 |

| Zone 3 | Daily market bazaar. fishing market zone. |

|

106 | 452 |

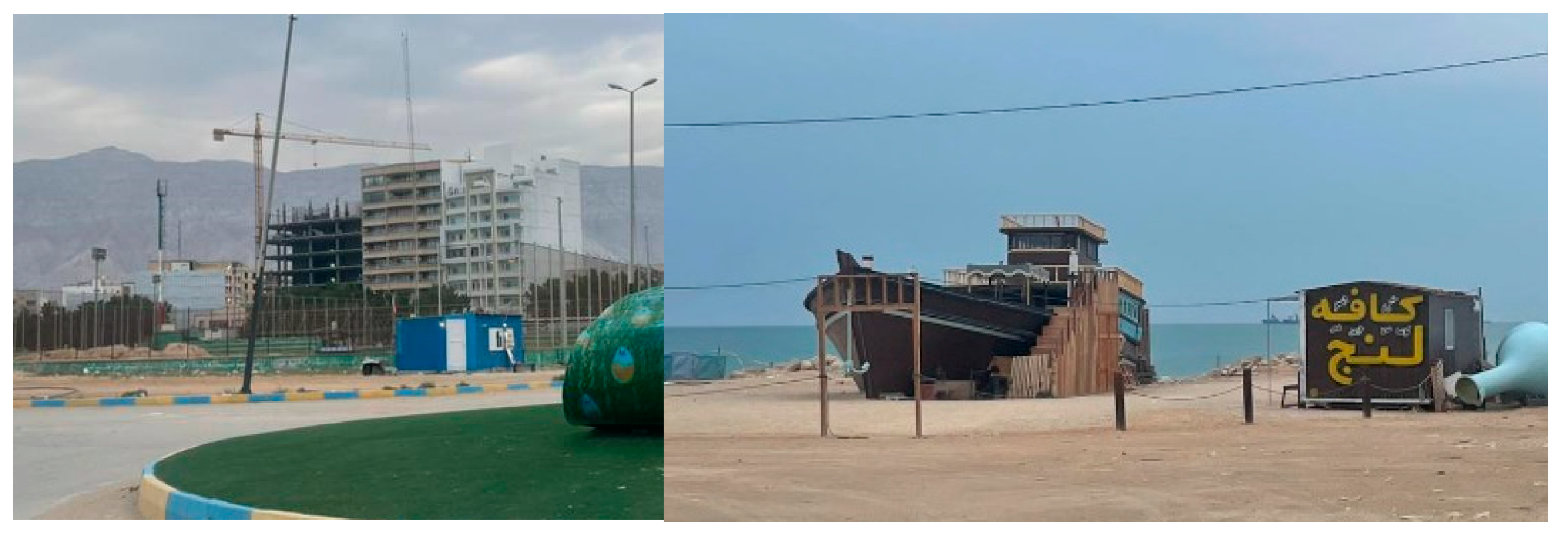

| Zone 4 | Main port of Asaluyeh. Walking. green spaces. coffee shop |  |

422 | 860 |

| Zone 5 | Mini Park. green space. fast-food. |  |

233 m | 650 |

| Zone 6 | football pitch. coffee shop. Administrative area. |  |

450 | 754 |

| Zone 7 | Administrative area. green space. kids play ground. green space |

|

360 | 1251 |

| Total | 2.586 | 4.833 | ||

| Age | Men | Men % | Women | Women % | Total | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18-20 | - | - | 3 | 8.03 | 3 | 3 |

| 21-30 | 6 | 9.50 | 6 | 16.26 | 12 | 12 |

| 31-40 | 31 | 49.27 | 18 | 48.72 | 49 | 49 |

| 41-50 | 20 | 31.73 | 7 | 18.96 | 27 | 27 |

| 51-60 | 6 | 9.50 | 3 | 8.03 | 9 | 9 |

| Total | 63 | 100 % | 37 | 100% | 100 | 100% |

| Level of education | Men | Men% | Women | Women % | Total | Total% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre- diploma | 5 | 7.94 | 4 | 10.81 | 9 | 9 |

| High school diploma | 8 | 12.69 | 9 | 24.33 | 17 | 17 |

| Associate degree | 14 | 22.22 | 7 | 18.92 | 21 | 21 |

| Bachelor degree | 22 | 34.93 | 12 | 32.43 | 34 | 34 |

| Master degree | 14 | 22.22 | 5 | 13.51 | 19 | 19 |

| Total | 63 | 100% | 37 | 100% | 100 | 100% |

| Job | Men | Men % | Women | Women % | Total | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housewife | - | - | 18 | 48.64 | 18 | 18 |

| Self- employed | 15 | 23.81 | 5 | 13.52 | 20 | 20 |

| Employee | 48 | 76.19 | 12 | 32.44 | 60 | 60 |

| Other | - | - | 2 | 5.4 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 63 | 100% | 37 | 100% | 100 | 100% |

| Sort | Men | Men % | Women | Women% | Total | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With a Group | 45 | 71.43 | 33 | 89.19 | 78 | 78 |

| Alone | 18 | 28.57 | 4 | 10.81 | 22 | 22 |

| Total | 63 | 100% | 37 | 100% | 100 | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).