Submitted:

08 February 2025

Posted:

08 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

COVID-19 infection continues globally with frequent emergence of unfamiliar SARS-CoV-2 variants acting to impair immunity conferred by vaccines. The competitive binding of SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins by angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) to mimetic and act as a de-coy over that by native ACE-2 receptors on healthy human cells re-mains a practical approach to lessen viral spread. In this study, a therapeutic strategy was developed that targeted gastrointestinal SARS-CoV-2 infection using ACE-2 encapsulated in chi-tosan/tripolyphosphate cross-linked nanoparticles (NPs). Optimization conditions were determined by varying pH (4.0-6.5) and chitosan: ACE-2 mixing ratios (1:1, 1.5:1, 2:1, 2.5:1, 3:1), followed by choice of spray-drying (SD), freeze-drying (FD), or spray-freeze drying (SFD) with varying mannitol concentrations (0, 1:1, and 5:1 of total weight). The optimal formulation was achieved using a pH 5.5 with a mixing chitosan-ACE-2 ratio of 2:1; where ACE-2 loaded NPs had an average particle size of 303.7 nm, polydispersity index (PDI) of 0.21, encapsula-tion efficiency (EE) of 98.4%, zeta potential of 6.8 mV, and ACE-2 loading content (LC) of 28.4%. In general, all drying methods main-tained the spherical shape of the NPs with varying mannitol concen-tration having a significant (P<0.05) effect. After reconstitution, all SD samples had a relatively low yield rate, but the ACE-2 NPs dehydrated specifically by SFD required a lower amount of added mannitol (1:1 of its total weight) and produced a higher yield rate (P<0.05) and similar PDI and EE values, along with relatively good particle size and LC. This formulation also produced a high ACE-2 release and uptake in differentiated Caco-2 cells; thus, representing an effective ACE-2 en-capsulation procedure for use with dry powders.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. ACE-2 Nanoparticles Preparation

2.3. Dehydration of the ACE-2 NPs

2.4. Characterization of Nanoparticles

2.5. Fourier Transform Infrared-Attenuated Total Reflectance (FTIR-ATR) Spectroscopy

2.6. Reconstitution Test

2.7. In Vitro Release Profile of ACE-2 Loaded NPs

2.8. In Vitro Cellular Uptake Study

2.9. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assay

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Optimization of Chitosan-TPP Cross-Linked ACE-2 NPs

3.2. Morphological Analysis of ACE-2 NPs Dehydrated by Different Methods

3.3. FTIR-ATR Spectroscopy Analysis

3.4. Yield Rate, Reconstitution and Stability Analysis

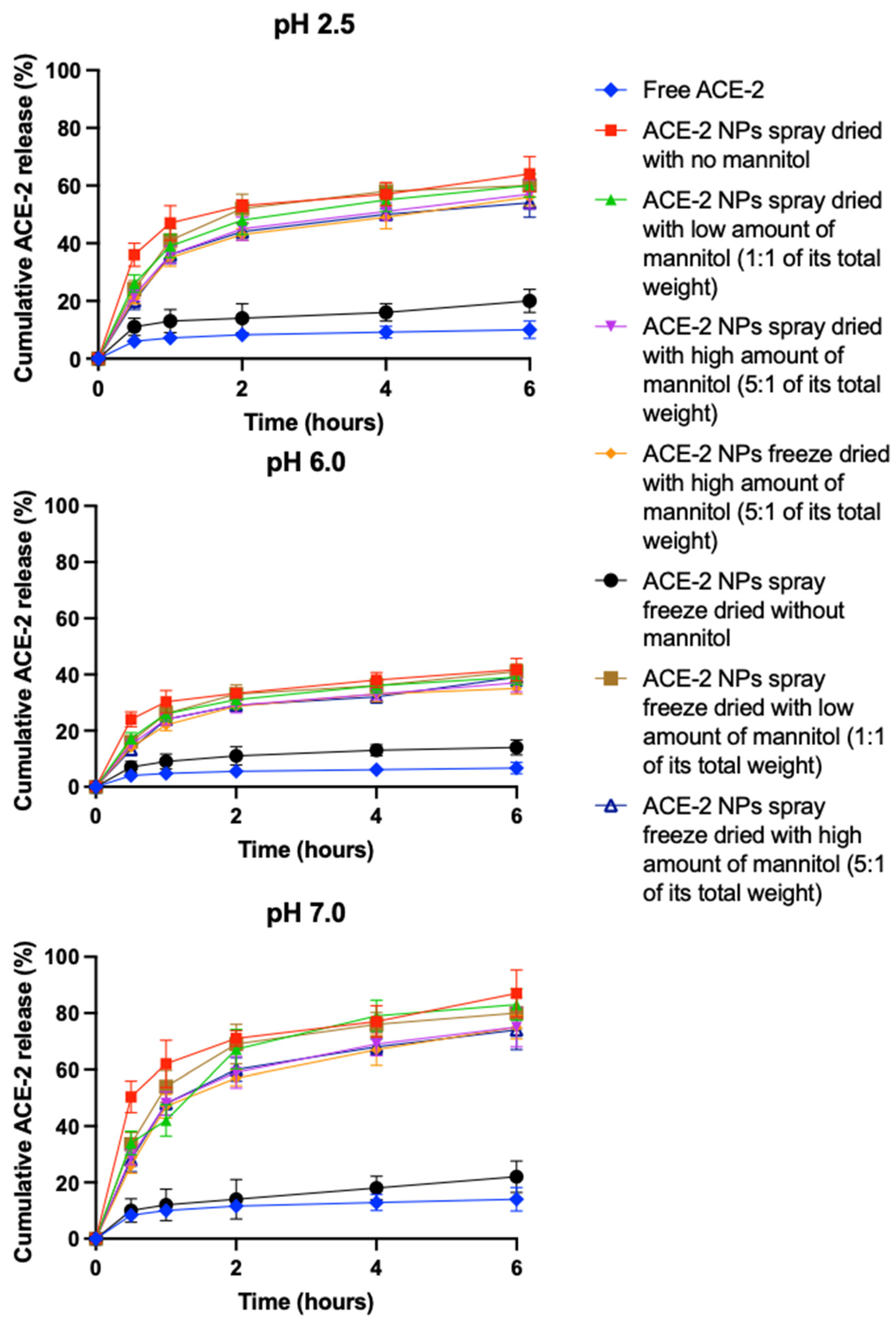

3.5. In Vitro Release of ACE-2 from NPs at Different pHs

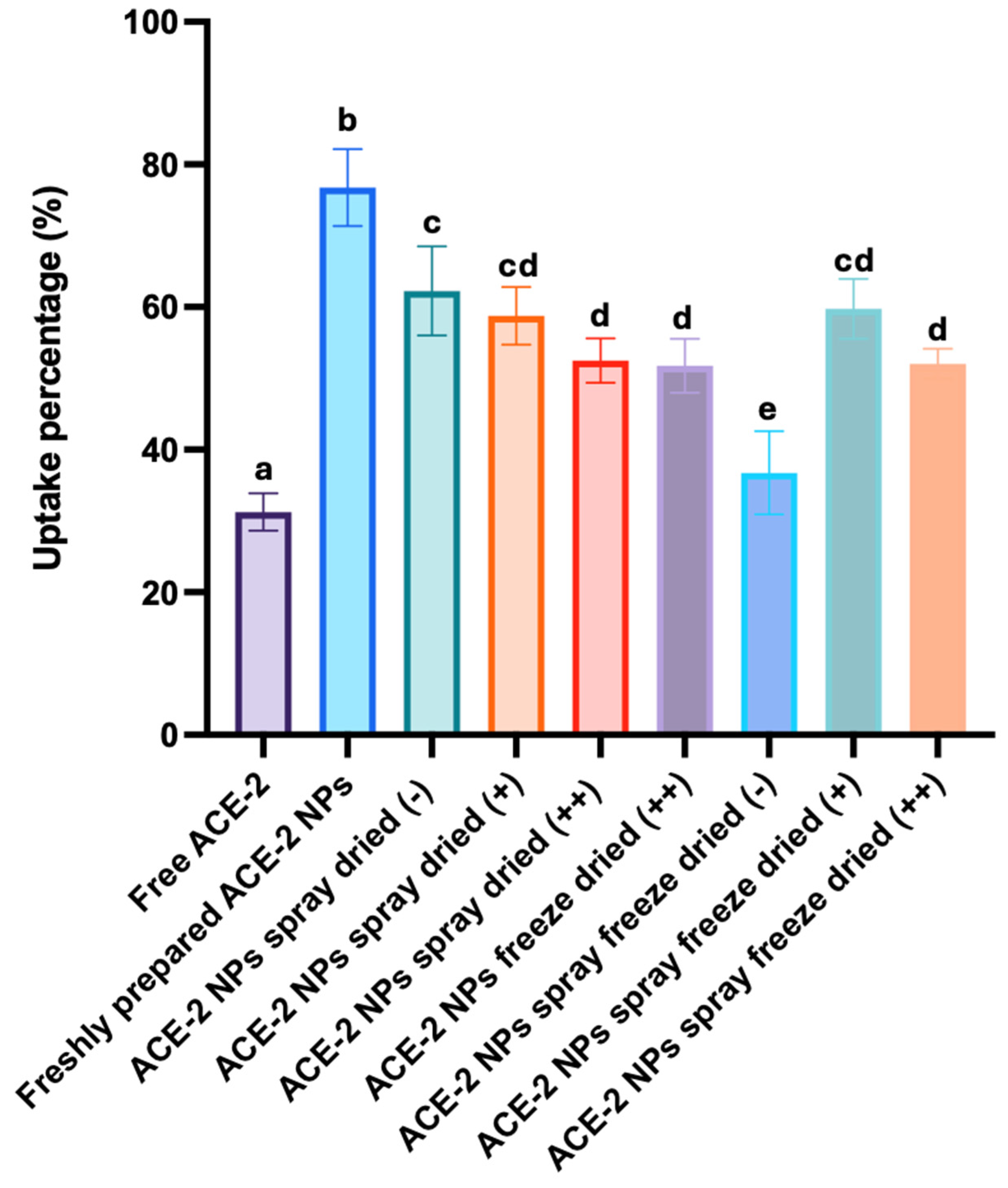

3.6. In Vitro Cellular (Cacp-2) Uptake of Dehydrated ACE-2 NPs

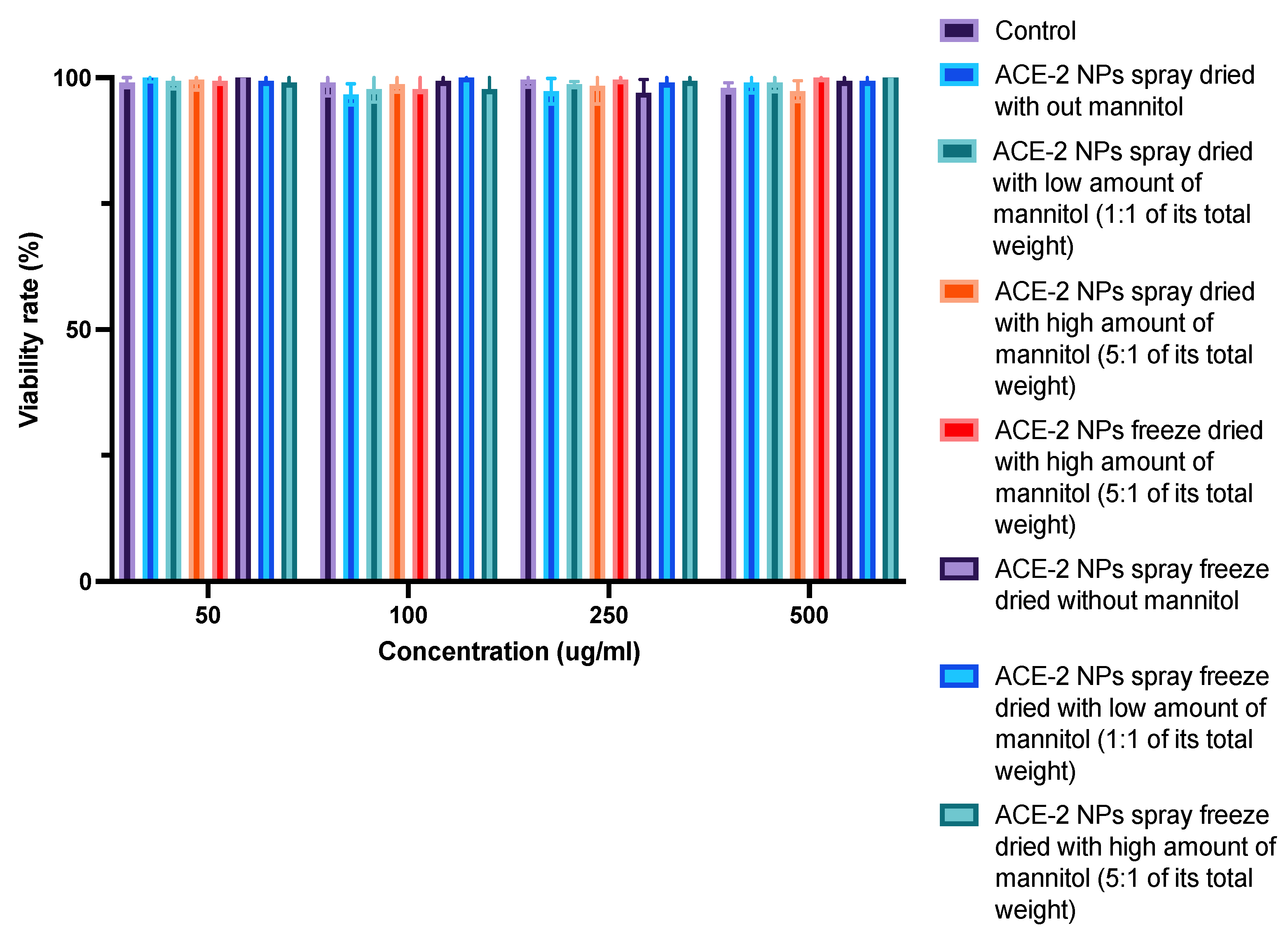

3.7. In Vitro Toxicity Evaluation of Dehydrated ACE-2 NPs

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Z.; Hu, S.; Popowski, K. D.; Liu, S.; Zhu, D.; Mei, X.; Li, J.; Hu, Y.; Dinh, P.-U. C.; Wang, X. Inhalation of ACE2-expressing lung exosomes provides prophylactic protection against SARS-CoV-2. Nature Communications 2024, 15(1), 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, A.; Irie, T.; Suzuki, R.; Maemura, T.; Nasser, H.; Uriu, K.; Kosugi, Y.; Shirakawa, K.; Sadamasu, K.; Kimura, I. Enhanced fusogenicity and pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 Delta P681R mutation. Nature 2022, 602(7896), 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldelli, A.; Wong, C. Y. J.; Oguzlu, H.; Gholizadeh, H.; Guo, Y.; Ong, H. X.; Singh, A.; Traini, D.; Pratap-Singh, A. Nasal delivery of encapsulated recombinant ACE2 as a prophylactic drug for SARS-CoV-2. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2024, 655, 124009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannar, D.; Saville, J. W.; Zhu, X.; Srivastava, S. S.; Berezuk, A. M.; Zhou, S.; Tuttle, K. S.; Kim, A.; Li, W.; Dimitrov, D. S. Structural analysis of receptor binding domain mutations in SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern that modulate ACE2 and antibody binding. Cell Reports 2021, 37(12). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoufaly, A.; Poglitsch, M.; Aberle, J. H.; Hoepler, W.; Seitz, T.; Traugott, M.; Grieb, A.; Pawelka, E.; Laferl, H.; Wenisch, C. Human recombinant soluble ACE2 in severe COVID-19. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2020, 8(11), 1154–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diao, X.; Jia, R.; Wang, Y.; Liu, G.; Chen, X.; Liu, D.; Guan, H. The physicochemical properties, microstructure, and stability of diacylglycerol-loaded multilayer emulsion based on protein and polysaccharides. LWT 2024, 196, 115879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M. A.; Syeda, J. T.; Wasan, K. M.; Wasan, E. K. An overview of chitosan nanoparticles and its application in non-parenteral drug delivery. Pharmaceutics 2017, 9(4), 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rampino, A.; Borgogna, M.; Blasi, P.; Bellich, B.; Cesàro, A. Chitosan nanoparticles: Preparation, size evolution and stability. International journal of pharmaceutics 2013, 455(1-2), 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balde, A.; Kim, S.-K.; Benjakul, S.; Nazeer, R. A. Pulmonary drug delivery applications of natural polysaccharide polymer derived nano/micro-carrier systems: A review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 220, 1464–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezvankhah, A.; Emam-Djomeh, Z.; Askari, G. Encapsulation and delivery of bioactive compounds using spray and freeze-drying techniques: A review. Drying Technology 2020, 38(1-2), 235–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Baldelli, A.; Singh, A.; Fathordoobady, F.; Kitts, D.; Pratap-Singh, A. Production of high loading insulin nanoparticles suitable for oral delivery by spray drying and freeze drying techniques. Scientific reports 2022, 12(1), 9949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vishali, D.; Monisha, J.; Sivakamasundari, S.; Moses, J.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. Spray freeze drying: Emerging applications in drug delivery. Journal of Controlled Release 2019, 300, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggerstedt, S. N.; Dietzel, M.; Sommerfeld, M.; Süverkrüp, R.; Lamprecht, A. Protein spheres prepared by drop jet freeze drying. International journal of pharmaceutics 2012, 438(1-2), 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishwarya, S. P.; Anandharamakrishnan, C.; Stapley, A. G. Spray-freeze-drying: A novel process for the drying of foods and bioproducts. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2015, 41(2), 161–181. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, Q.; Wang, T.; Cochrane, C.; McCarron, P. Modulation of surface charge, particle size and morphological properties of chitosan–TPP nanoparticles intended for gene delivery. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2005, 44(2-3), 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Gokhale, R.; Burgess, D. J. Sugars as bulking agents to prevent nano-crystal aggregation during spray or freeze-drying. International journal of pharmaceutics 2014, 471(1-2), 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Freshly prepared | FD ++ |

SD - |

SD + |

SD ++ |

SFD - |

SFD + |

SFD - |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS (nm) | 303 ± 12a | 674 ± 47b | 343 ± 33c | 535 ± 24d | 613 ± 37b | 366 ± 29c | 548 ± 30d | 664 ± 42b |

| PDI | 0.19 ± 0.02a | 0.24 ± 0.03a | 0.22 ± 0.02a | 0.23 ± 0.03a | 0.25 ± 0.05a | 0.22 ± 0.04a | 0.21 ± 0.03a | 0.20 ± 0.04a |

| EE (%) | 98.40± 0.32a | 98.01 ± 0.43a | 97.63 ± 0.29a | 99.01 ± 0.51a | 98.23 ± 0.43a | 99.03 ± 0.39a | 98.93 ± 0.36a | 99.02 ± 0.22a |

| LC (%) | 28.42 ± 0.21a | 4.71 ± 0.13b | 18.14 ± 0.44c | 3.92 ± 0.10d | 2.02 ± 0.06e | 27.84 ± 0.30a | 14.22 ± 0.32f | 4.69 ± 0.36b |

| YR (%) | NA | 99.83 ± 0.13a | 47.87 ± 2.13b | 53.32 ± 3.13c | 55.31 ± 2.13c | 99.67 ± 0.13a | 98.98 ± 0.13a | 99.32 ± 0.13a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).