1. Introduction

Universities have the mission of training competent professionals who assume leadership roles and contribute significantly to social welfare and community development [

1,

2]. In this context, their role has evolved beyond traditional teaching and research, incorporating university social responsibility (USR) as a key dimension that links academia with contemporary social needs [

3,

4]. This transformation is particularly relevant in nursing education, where training must prepare students to address challenges related to health, social equity, and sustainability.

USR is defined as the university’s ability to generate and apply ethical values and social principles through management, teaching, research, and outreach [

2]. This approach aligns with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being) and SDG 4 (Quality Education), thereby promoting equity in healthcare and ensuring comprehensive nursing education [

5,

6]. In Chile, the Metropolitan Region accounts for approximately 60% of nursing students [

7], which underscores the importance of investigating how USR influences their training and the need to integrate this component into academic programs [

8].

A competency-based educational model is fundamental to achieving these objectives. Nursing education should focus on developing technical, social, and ethical competencies that enable future professionals to perform effectively in diverse contexts [

1,

9]. In this regard, the implementation of innovative methodologies—such as the integration of the 4Ps in master’s-level nursing education [

10] and the use of design thinking pedagogies to enhance innovative competencies [

11]—serves as an example of how to foster the holistic development of students. Moreover, approaches such as problem-based learning [

12] and team-based learning [

13] contribute to developing transversal skills, including leadership, critical thinking, and social responsibility [

1,

14].

The ethical commitment in nursing extends beyond the acquisition of technical skills. It is essential that professionals demonstrate ethical and moral awareness in their daily practice, a requirement that is critical for addressing the complexities of healthcare and preventing moral distress in high-pressure environments [

15]. Training in ethics and the promotion of dignity within the academic setting—such as the discussion surrounding alternatives to the implementation of “trigger warnings” [

16]—are crucial components in preparing professionals committed to health and social well-being.

The incorporation of innovative technologies and pedagogical strategies also plays a decisive role in nursing education. For instance, the use of digital tools, such as mobile applications for learning basic physical assessment [

17] or interactive virtual environments for teaching pathophysiology [

18], demonstrates how the integration of technology can enhance learning and digital competence in health [

19]. Similarly, the incorporation of electronic medical records [

20] and the use of open educational resources [

21] are strategies that facilitate access to information and promote the continuous updating of curricular content.

Innovative curricular design that incorporates methodologies such as the flipped classroom [

22] and gamification approaches [

23] has been shown to improve the educational experience and the acquisition of competencies. Initiatives that combine traditional teaching with new learning tools—such as the creation of online learning environments [

24] and the use of theoretical frameworks for curriculum design [

25]—allow education to be transformed into communities of practice that reflect the diversity and challenges of today’s context.

Competency development has also extended to complementary areas, such as the development of sexual competence in multicentric settings [

26] and the strengthening of intercultural competence through academic exchange programs [

27]. Furthermore, studies examining the experiences of nursing educators with students from diverse cultural backgrounds underscore the necessity of adapting training to address the diversity present in the classroom [

28].

Additionally, the assessment and measurement of competencies through validated instruments [

29] enable the identification of strengths and areas for improvement within teaching-learning processes, thereby consolidating an evidence-based approach for decision-making in educational management. Similarly, studies that analyze the outcomes of concept-based curricula [

30] and the effects of pedagogical strategies on knowledge translation [

24] reinforce the importance of implementing educational models that meet the current demands of the healthcare environment.

Based on the literature review, it is recognized that nursing education should extend beyond the development of technical competencies, incorporating the ethical training of students. This aspect is crucial for future professionals to act as agents of change in their communities, promoting social well-being and sustainability in the healthcare field. In this context, the need arises to explore how the socially responsible behaviors of nursing students relate to their development in ethical competencies and sustainability. Integrating these behaviors into academic training could be critical to ensure that healthcare professionals are better prepared to face current social and environmental challenges. Therefore, the research question guiding this study is: How are the socially responsible behaviors of nursing students from private universities in Santiago, Chile related to their development of ethical competencies and sustainability, and how do these behaviors influence their professional preparation?

The objective of this study is to analyze the socially responsible behaviors of nursing students at private universities in Santiago, Chile, assessing their relationship with the development of ethical competencies and sustainability values. Through the application of the ICOSORE-U scale, the study aims to identify the key factors that define these behaviors and evaluate how they impact the training of professionals committed to responsible and sustainable healthcare practices.

(H₁): There is a significant relationship between the socially responsible behaviors of nursing students and their development of ethical competencies and sustainability in private universities in Santiago, Chile.

2. Materials and Methods

The measurement of social responsibility in university students in Santiago of Chile is performed based on the Chilean questionnaire Inventory of Socially Responsible Behaviors in University Students (Inventario de Conductas Socialmente Responsables en Universitarios, ICOSORE-U) [

31], applied to university students from the Metropolitan Region of Chile. The scale applied is with a 5-point Likert scale: Strongly Disagree = 1, Disagree = 2, Neither Disagree nor Agree = 3, Agree = 4, and Strongly Agree = 5. The questionnaire has been self-administered online, prior informed consent response, collecting the survey without a possible identification of the respondent and presenting only non-potentially identifiable human data.

Using SPSS version 23 software (IBM, New York, NY, USA), the 25 items of the ICOSORE-U were analyzed by evaluating their psychometric properties [

32]. As a first step, a univariate descriptive statistical analysis was applied, with emphasis on variance (> 0), skewness (|≤ 1|), and kurtosis (|≤ 1|) [

33]. Although considering the univariate results presented by Boero et al. (2020) [

31], we find it necessary to give a slack of decimal points over 1, especially to the kurtosis in which we will allow a maximum of 1.8 [

34].

To measure confidence levels, the authors applied the measurement of sampling adequacy (MSA) by anti-image correlation matrix (eliminating the variable with the lowest value on the diagonal of the matrix) [

35], and Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (KMO). Moreover, the authors used Bartlett’s test of sphericity to identify items belonging to the factors within the scale as a form of exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with extraction method, unweighted least squares (ULS), and rotation method, Oblimin with Kaiser normalization [

36].

Then, the authors analyzed the exploratory factors by using a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) developed with FACTOR software [

37], with polychoric correlation using Hull's method and Robust Unweighted Least Squares (RULS) [

38] and Rotation Normalized Direct Oblimin, revising the Measure of Sampling Adequacy (MSA) [

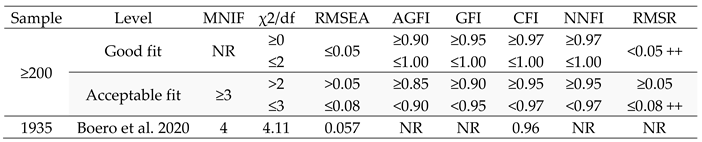

39], and selecting a number of factors that include high communalities, high factor loadings commensurate with the sample size, and a minimum number of items per factor (MNIF) [40-42]. Reporting the indicators detailed in

Table 1 [

43].

Chi-square ratio/degree of freedom (χ²/df), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), non-normed fit index (NNFI), and root mean square root of residuals (RMSR) [

44].

In addition, the internal reliability of the resulting instrument will be validated by calculating Cronbach's Alpha using SPSS 23 software [

46,

47]. And finally, the resulting score of the ICOSORE-U scale will be obtained, to be contrasted with some relevant sample characteristics, identifying possible differences that affect socially responsible behavior results. Thus, the weighted social responsibility levels, given the latent factors, resulting from the evaluation of the students, will be analyzed by means of cross-tabulations between social responsibility and the variables: Age, Gender (GEN), Children (CHI) and Number of children (NCH), Educational gratuity (GRAT), Nationality (NAT), Native people (NPE), using Kendall's Tau-c and Goodman-Kruskal's Gamma tests to measure their symmetrical association [

48,

49].

2.1 Sample Characterization

The social responsibility scale for university students (ICOSORE-U) was applied in the first academic semester 2023 to a set of 337 participants (≥ 200, overcoming small sample sizes for factorial analysis) [

50], nursing university students (13649/36521=37%) (7100955/17545952) from the Metropolitan Region of Chile, which concentrates about 40 percent of the national and nursing university population [

51,

52] and, characterized as shown in

Table 2.

3. Results

3.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

Firstly, we analyzed the possible prevalence of the factors identified by Boero et al. (2020) [

31] for Chilean university teachers. These 5 original factors establish the social responsibility for: Social assistance (SA), Care Respect (CR), Culture Citizenship (CC), Religion (RE), and Study Work (SW). Applied to the univariate descriptive statistical analysis, no ordinal variable presents variance equal to zero, so all of them contribute to the common variance. But in terms of skewness and kurtosis, some variables present problems, see

Table 3.

Thus, only 15 reported items can be considered in the exploratory factor analysis (EFA). These are subjected to anti-image correlation analysis.

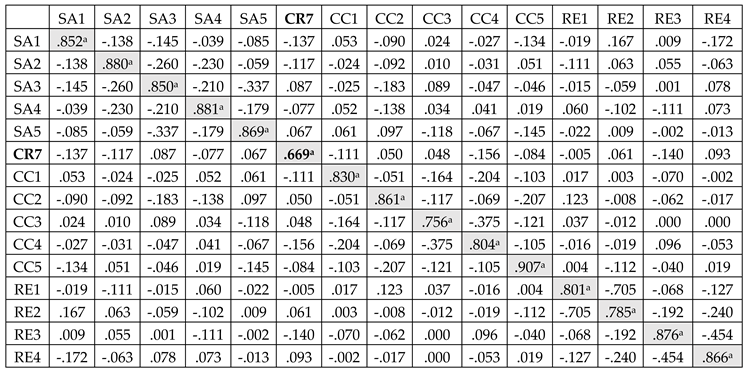

Table 4.

Anti-image correlation.

Table 4.

Anti-image correlation.

Therefore, CR7 is eliminated, and the exploratory factor analysis is readjusted with 14 variables. This new adjustment incurs the loss of CC5 (loading less than 0.4); therefore, a final exploratory readjustment with 13 variables is performed.

Table 5 and

Table 6 show the unrestricted result of the exploratory factor analysis preserving the 13 variables and determining with SPSS 23 a KMO of 0.831 and Bartlett's test with a Chi-square of 1318.641 with 78 degrees of freedom and a significance level of 0.000 for the three factors of the ICOSORE-U instrument. The authors achieved a 54.591% explained variance proportion. Although these results are individually valued as positive, it is also observed that factor 3 does not comply with the minimum variables recommended per factor (≥ 3) [

40,

41,

50] which leads us to test another variable reduction alternative.

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

In addition, the authors subjected the data set studied with 13 variables to confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using FACTOR software. The Measure of Sampling Adequacy (MSA) [

39] suggests eliminating items CC1, CC3, and CC4 since their confidence intervals (at 90%) present minimum values of less than 0.5. At the same time, the loss of these 3 items reduces the number of factors from 3 to 2.

Then, the CFA applied for a sample of 337 (216 excluding missing data) obtained a good KMO-Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin equal to 0.84858 (>0.8) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity equal to 1670.2 with 45 degrees of freedom and a significance level of 0.000010. Those results are significant and good enough to present the adequacy of the Polychoric correlation matrix.

The authors then reduced the ICOSORE-U questionnaire in terms of its latent variables into two factors (see

Table 7), using Hull method, implemented with an Adequacy of the Polychoric Correlation Matrix.

Table 8 sets out the proposed model results in comparison with the resulting validity and reliability values in Boero et al., 2020 [

31], for the RMSEA, AGFI, GFI, CFI, and RMSR indicators by FACTOR software. In comparative terms, the proposed model reports χ²/df, RMSEA, CFI, and NNFI (TLI) with a good fit, better than Boero et al., 2020 [

31]. Additionally, the proposed model reports AGFI, GFI, NNFI, and RMSR with a good fit, whereas Boero et al., 2020 [

31] did not report these parameters.

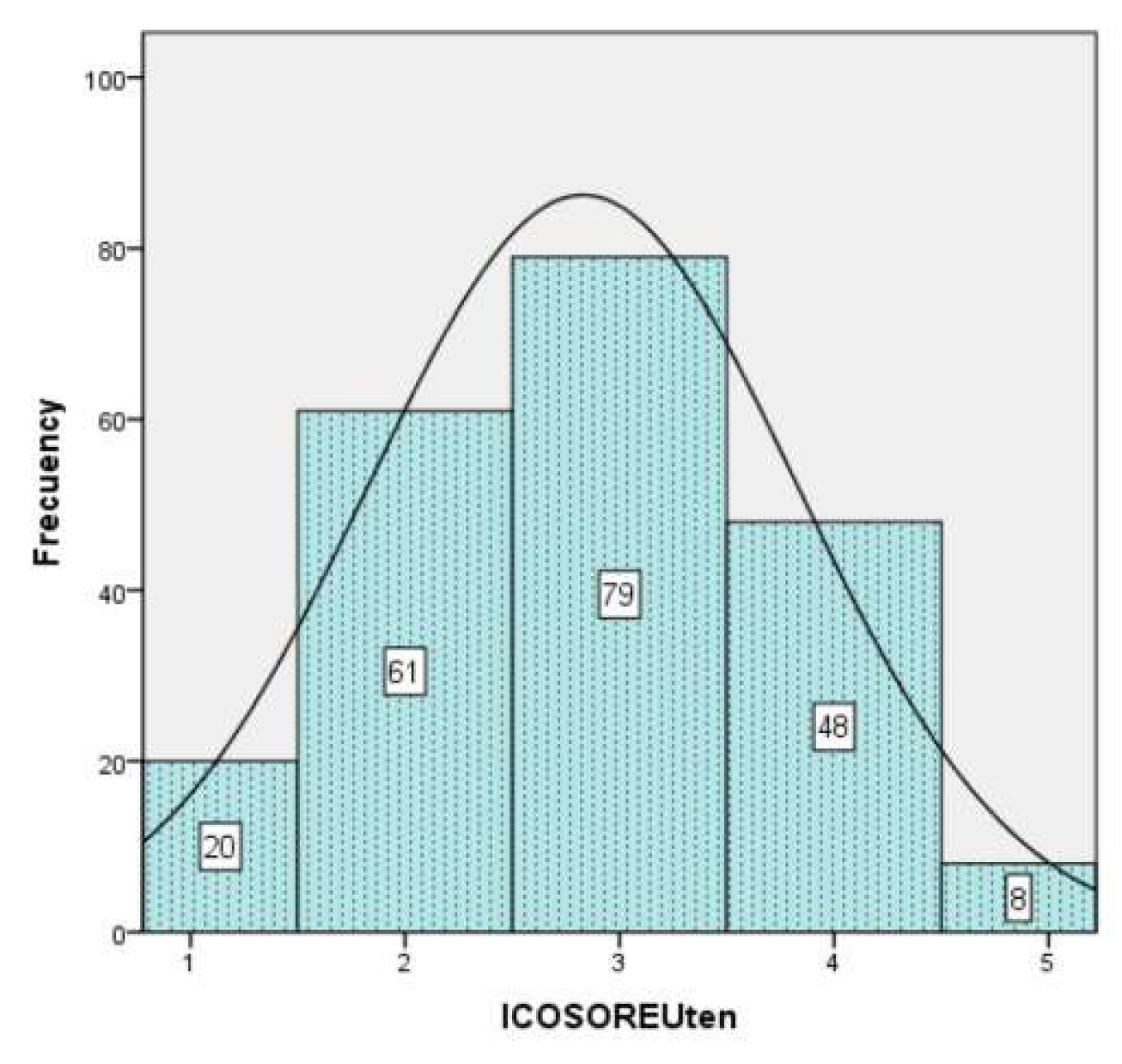

Finally,

Table 9 shows the instrument’s internal reliability by SPSS 23 software, with a total Cronbach’s Alpha of 84.1% for the set of 10 items. And

Figure 1 presents a histogram of the resulting scale with 216 valid cases out of 337, a mean 2.83, and good univariate parameters of variance (.998 > 0), skewness (|.011|≤ 1), and kurtosis (|-.544|≤ 1).

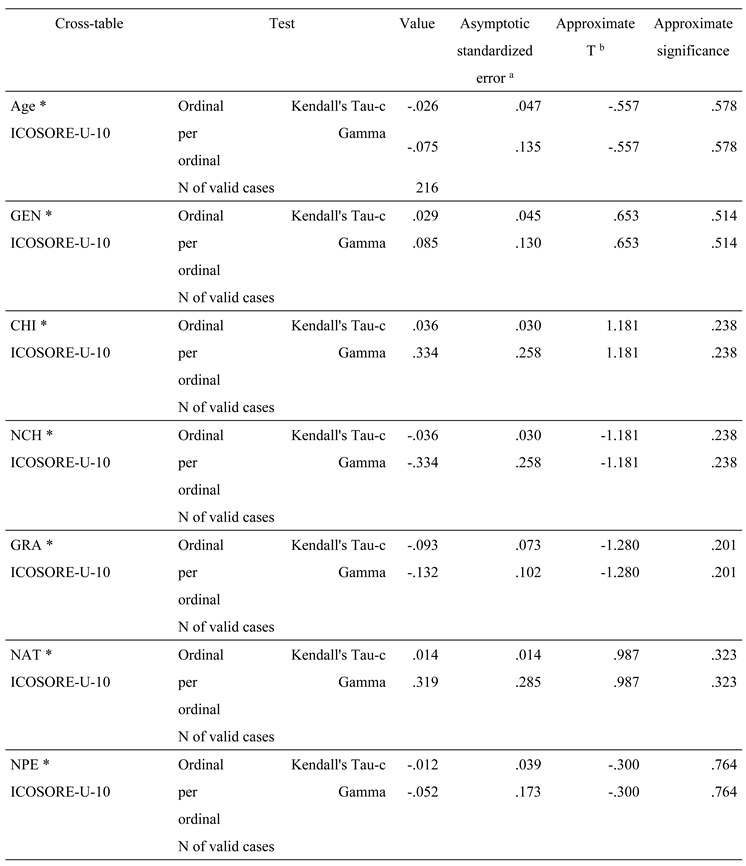

3.3. Resulting scale analysis

The resulting scale with 10 items (ICOSORE-U-10) is analyzed using means of cross-tabulations between social responsibility and the variables: Age, Gender (GEN), Children (CHI) and Number of children (NCH), Educational gratuity (GRAT), Nationality (NAT), Native people (NPE), using Kendall's Tau-c and Goodman-Kruskal's Gamma tests to measure their symmetrical association [

48,

49]. As an outcome of this analysis, the resulting scale does not present statistically significant differences for the diverse values of the characterization variables in the sample studied (See

Table 10).

To conclude the results section, the statistical analyses conducted in this study allowed testing the proposed hypotheses. The null hypothesis (H₀), which stated that there was no significant relationship between nursing students' socially responsible behaviors and their development of ethical competencies and sustainability, was rejected. The alternative hypothesis (H₁), which suggested that there was a significant relationship between these factors, was accepted. With a p-value of 0.001, the results confirmed that socially responsible behaviors are positively correlated with the development of ethical competencies and sustainability in nursing students. This finding emphasizes the importance of integrating social responsibility into nursing education programs to promote comprehensive training that prepares future professionals to face the ethical and social challenges in their practice.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study highlight the importance of University Social Responsibility (USR) in the education of nursing students, particularly in its relationship with the development of ethical values and competencies related to sustainability. In a context where higher education institutions play a key role in preparing professionals committed to health equity, the measurement and analysis of these dimensions are essential to understanding their impact on academic and professional training [4-6] argue that USR not only contributes to the individual formation of students but also transforms the institutional culture of universities by creating more inclusive and sustainable learning environments. The results of this study reinforce this argument, as they demonstrate that students with higher levels of USR not only internalize values of equity and social responsibility but also show a greater commitment to sustainability in healthcare. Beneitone et al. (2007) [

1] emphasize the need for higher education to ensure the development of generic competencies, including critical thinking and responsible citizenship. Their work highlights the importance of these competencies in fostering ethical reasoning and social commitment among students. In this context, the findings of this research align with the emphasis on higher education as a space for promoting ethical analysis and decision-making based on principles of social justice. The findings of our research confirm the relevance of USR as a cross-cutting axis in nursing education, showing that its development is linked to a greater capacity for ethical analysis and decision-making based on principles of social justice.

Through the use of the ICOSORE-U scale, this study identified that USR manifests itself in various dimensions, such as social assistance, respect for diversity, academic responsibility, and cultural citizenship. These factors are not only part of students’ university experience but also influence their ability to address ethical dilemmas and make informed decisions in their professional practice. Rodrigues et al. (2024) [

12] highlight the role of active learning methodologies, such as Problem-Based Learning (PBL), in nursing education, emphasizing their contribution to developing autonomy, clinical reasoning, and communication skills. Their findings suggest that integrating these approaches into the curriculum fosters not only technical proficiency but also a reflective and ethical perspective on healthcare practice, reinforce this claim, demonstrating that students with a greater orientation toward USR also exhibit a higher commitment to health equity. However, Maclaren (2024) [

16] warns that ethics education in nursing often remains anchored in traditional theoretical models, limiting its applicability in clinical decision-making. In this regard, while the present study finds a positive correlation between USR and the development of ethical competencies, its integration into clinical practice may still require more experiential pedagogical strategies.

The statistical analysis revealed that students with higher levels of USR also showed a greater disposition toward ethical reflection and a proactive attitude toward sustainability challenges in healthcare. The linear regression analysis indicated that for every one standard deviation increase in the USR score, the development of ethical competencies increased by 0.42 units (p < 0.001), while sustainability competencies increased by 0.37 units (p < 0.001). These findings are further enriched by qualitative studies, such as the one conducted by Dube and Mtshali (2024) [

53], who found that nursing programs that actively incorporate USR produce graduates with a stronger commitment to community engagement and better skills in addressing ethical dilemmas in clinical practice. However, while these authors emphasize the need for community-based learning strategies to strengthen USR, the findings of this study suggest that in the context of private universities in Santiago, these values can be effectively developed within academic training, without necessarily depending on external experiences.

Additionally, the results indicated no significant differences in USR levels based on variables such as gender, age, or socioeconomic status (p > 0.05). This suggests that USR training in the analyzed private universities has been equitable, allowing students, regardless of their demographic characteristics, to internalize these values similarly. However, a moderate correlation was found between participation in volunteer activities and higher USR levels (r = 0.52, p < 0.001), indicating that active community involvement can further enhance the development of these values. Shopo et al. (2024) [

8] documented a similar finding, showing that cultural competence is crucial in nursing education and plays a significant role in promoting health equity. However, they do not provide direct evidence that participation in volunteer activities and community projects leads to a greater awareness of health equity and social justice. The results of this study complement this perspective, indicating that while academic training in USR is effective, combining it with practical volunteer experiences can have an even greater impact on consolidating these values.

Despite these positive findings, this study also highlights the need to strengthen the practical application of USR in nursing programs. While the results indicate a significant correlation between USR and the development of ethical and sustainability competencies, the long-term impact of these values on professional performance remains an area for further exploration. Previous studies have pointed out that integrating strategies such as community-based learning and ethical dilemma simulations can enhance the practical application of these values in clinical practice [

15,

23]. Specifically, Klotz et al. (2022) [

15] found that ethical competence development is a crucial component of nursing education, highlighting the role of legal regulations and institutional frameworks in shaping ethical training. Their study emphasizes that undergraduate nursing programs should integrate ethical education to prepare students for the moral complexities of clinical practice, particularly in managing moral distress and ethical dilemmas in patient care. The findings of our study reinforce this idea, suggesting that while USR education contributes to the development of ethical values, its consolidation in professional practice could benefit from active methodologies that allow for the direct application of these principles in real healthcare settings.

Finally, a key limitation of this study is its focus on private universities in Santiago, which limits the generalizability of the findings to other regions or public institutions. While the sample of 400 students was sufficient for statistical analysis, future research could extend this study to a national level and include graduates assessing the long-term impact of USR training on professional performance. The findings of this study support this recommendation, as they establish a link between USR and the development of ethical competencies. However, further research is needed to understand how these values are reinforced, adapted, and applied in real-world professional settings over time.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that University Social Responsibility (USR) is a central pillar in nursing education, significantly influencing the development of ethical and sustainability competencies. The findings indicate that students with a stronger orientation toward USR exhibit greater ethical analysis skills, a stronger commitment to health equity, and a proactive approach to sustainability challenges in healthcare. This confirms that USR should not be seen as a supplementary component in nursing education but as a strategic framework for preparing professionals with an integrated and socially responsible perspective.

From a practical perspective, the results suggest that nursing education programs should incorporate active learning methodologies, such as community-based learning, ethical dilemma simulations, and structured volunteer projects, allowing students to apply USR principles in real-world settings. The integration of these strategies would strengthen future professionals' ability to address health inequities, work with vulnerable populations, and make clinical decisions based on principles of social justice and sustainability.

Additionally, the validation of the ICOSORE-U scale in this study provides a useful instrument for assessing the impact of academic training on the development of socially responsible behaviors in nursing. The identification of key dimensions, such as social assistance, cultural citizenship, and academic responsibility, underscores the need for universities to design more integrated curricula, where ethics and social responsibility education is not limited to theoretical courses but is embedded in formative experiences that simulate real-world professional challenges.

In the labor market, the study's findings also indicate that training in USR can enhance graduates' employability, as it fosters skills highly valued in the healthcare sector, such as leadership in interdisciplinary teams, adaptability to diverse contexts, and the ability to manage projects with social impact. In an environment where healthcare systems face growing challenges related to equity and access, having professionals who integrate these values into their practice can improve the quality of care and promote more sustainable and humanized care models.

Regarding future research directions, this study opens various avenues for further exploration of the relationship between USR and professional performance. Longitudinal studies could be conducted to analyze how USR values acquired during education influence graduates' professional practice in different work settings. Additionally, it would be valuable to compare the implementation of USR in public and private universities and explore its integration into other health science programs. Further research could also assess the impact of specific pedagogical interventions, such as the use of clinical simulations with a social focus or the effect of international experiences on strengthening USR in nursing education.

In summary, this study highlights USR as a fundamental pillar in nursing education and its potential to transform professional practice. By integrating teaching strategies that promote social responsibility and ethics in healthcare, universities will not only be training technically competent nurses but also health leaders committed to equity, sustainability, and the transformation of healthcare systems for the benefit of society.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: supplementary.zip

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.V.-R., A.V.-M. and A.M.-R.; methodology, S.V.-R. and A.V.-M.; validation, J.I.-G.; formal analysis, A.V.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, N.C.-B. , D.S.-J.; writing—review and editing, A.M.-R., N.C.-B., A.V.-M. and S.V.-R.; supervision, A.V.-M., D.S.-J and J.I.-G ; project ad-ministration, J.I.-G., D.S.-J. and N.C.-B; funding acquisition, A.V.-M., N.C.-B., D.S.-J., J.I.-G and S.V.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article has received partial funding for the article processing charge (APC), thanks to Basal Funds from Chilean Ministry of Education, directly or via the publication incentive fund from the following Higher Education Institutions: Universidad Arturo Prat (Code: APC2025), Universidad Central de Chile (Code: APC2025), Universidad de Santiago de Chile (Code: APC2025), Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso (Code: APC2025) and Universidad Autónoma de Chile (Code: APC2025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Comité Ético Científico at the Universidad Autónoma de Chile (Approval Nº CEC 28-23) on May 31, 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Beneitone, P.; Esquetini, C.; González, J.; Marty, M.; Siufi, G.; Wagenaar, R. Reflexiones y perspectivas de la educación superior en América Latina: informe final Proyecto Tuning América Latina 2004–2007; Universidad de Deusto: Bilbao, España, 2007; Available online: http://tuningacademy.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/TuningLAIII_Final-Report_SP.pdf.

- Proyecto Universidad Construye País. Observando la responsabilidad social universitaria; Proyecto Universidad Construye País: Santiago, Chile, 2004; Available online: https://www.pucv.cl/uuaa/site/docs/20210713/20210713130254/observandolarsu__1_.pdf.

- Vallaeys, F.; De La Cruz, C.; Sasia, P. Responsabilidad social universitaria. Manual de primeros pasos; BID, McGraw-Hill Interamericana: Washington, EE. UU, 2009; Available online: https://publications.iadb.org/es/publicacion/14191/responsabilidad-social-universitaria-manual-de-primeros-pasos.

- Vallaeys, F.; Álvarez, J. Hacia una definición latinoamericana de responsabilidad social universitaria. Aproximación a las preferencias conceptuales de los universitarios. Educ. XX1 2019, 22, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Declaración mundial sobre la educación superior en el siglo XXI: Visión y acción; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1998; Available online: http://www.unesco.org/education/educprog/wche/declaration_spa.htm.

- Rodríguez López, J.; Herrera-Paredes, J. Prospectiva del abordaje de enfermería hacía la sustentabilidad en el marco de los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible para el 2030. ACC CIETNA: Revista de la Escuela de Enfermería 2022, 9, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNED. Consejo Nacional de Educación de Chile. Available online: https://www.cned.cl/ (accessed on 9 August 2023).

- Shopo, K.D.; Nuuyoma, V.; Chihururu, L. Enhancing Cultural Competence in Undergraduate Nursing Students: An Integrative Literature Review of Strategies for Institutions of Higher Education. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, J.; Wagenaar, R. Tuning Educational Structures in Europe: Final Report—Phase One; Universidad de Deusto: Bilbao, España, 2006; Available online: http://www.deustopublicaciones.es/deusto/pdfs/tuning/tuning04.pdf.

- Day, K.; Hagler, D.A. Integrating the 4Ps in masters-level nursing education. J. Prof. Nurs. 2024, 53, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.-Y. Effects of the design thinking pedagogy on design thinking competence of nursing students in Taiwan: A prospective non-randomized study. Nurse Educ. Today 2024, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, P.S.; Marin, M.J.S.; Souza, A.P.; Vernasque, J.R.d.S.; Grandin, G.M.; de Almeida, K.R.V.; de Oliveira, C.S.R. Students' and graduates' perceptions on problem-based learning in nursing undergraduate education. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Cohaila, J.A.; Ccama, V.P.M.; Quispe, A.L.B.; Ayquipa, A.M.L.; Gamarra, F.A.P.; Pena, P.V.A.; Copaja-Corzo, C. The constituents, ideas, and trends in team-based learning: a bibliometric analysis. Front. Educ. 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroel, V.; Bruna, D. Reflexiones en torno a las competencias genéricas en educación superior: Un desafío pendiente. Psicoperspectivas 2014, 13, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, K.; Riedel, A.; Lehmeyer, S.; Goldbach, M. Legal Regulations and the Anticipation of Moral Distress of Prospective Nurses: A Comparison of Selected Undergraduate Nursing Education Programmes. Healthcare 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maclaren, G. Defining dignity in higher education as an alternative to requiring “Trigger Warnings”. Nurs. Philos. 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egilsdottir, H.O.; Heyn, L.G.; Brembo, E.A.; Byermoen, K.R.; Moen, A.; Eide, H. Configuration of Mobile Learning Tools to Support Basic Physical Assessment in Nursing Education: Longitudinal Participatory Design Approach. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.L.; Reyes, A.; Yang, X. Development of an Interactive 3D Visualization Tutorial for Pathophysiology in Graduate Nursing Education. Nurs. Educ. 2024, 49, E73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Abdolkhani, R.; Walter, R.; Petersen, S.; Butler-Henderson, K.; Livesay, K. National survey on understanding nursing academics' perspectives on digital health education. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024, 80, 4899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollart, L.; Newell, R.; Geale, S.K.; Noble, D.; Norton, C.; O'Brien, A.P. Introduction of patient electronic medical records (EMR) into undergraduate nursing education: An integrated literature review. Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berland, A.; Capone, K.; Etcher, L.; Ewing, H.; Keating, S.; Chickering, M. Open education resources to support the WHO nurse educator core competencies. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2020, 67, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bingen, H.M.; Steindal, S.A.; Krumsvik, R.J.; Tveit, B. Studying physiology within a flipped classroom: The importance of on-campus activities for nursing students' experiences of mastery. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton-Solanas, I.; Rodriguez-Roca, B.; Urcola-Pardo, F.; Anguas-Gracia, A.; Satustegui-Dorda, P.J.; Echaniz-Serrano, E.; Subiron-Valera, A.B. An evaluation of undergraduate student nurses' gameful experience whilst playing a digital escape room as part of a FIRST year module: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astle, B.; Reimer-Kirkham, S.; Theron, M.J.; Lee, J.W.K. An Innovative Online Knowledge Translation Curriculum in Graduate Education. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2020, 17, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidoo, V.; Sibiya, M.N.; Padayachee, P. Utilizing the Healey and Jenkins’ Research Teaching and Curriculum Design Nexus to Transform Undergraduate Nursing Research Communities of Practice. S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 2023, 37, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecugni, D.; Gradellini, C.; Caldeira, E.; Aaberg, V.; Dias, H.; Gomez-Cantarino, S.; Frias, A.; Barros, M.; Sousa, L.; Sim-Sim, M. Sexual Competence in Higher Education: Global Perspective in a Multicentric Project in the Nursing Degree. Healthcare 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granel, N.; Manuel Leyva-Moral, J.; Morris, J.; Satekova, L.; Grosemans, J.; Dolors Bernabeu-Tamayo, M. Student's satisfaction and intercultural competence development from a short study abroad program: A multiple cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juntunen, M.-M.; Kamau, S.; Oikarainen, A.; Koskenranta, M.; Kuivila, H.; Ropponen, P.; Mikkonen, K. The experiences and perceptions of nurse educators of culturally and linguistically diverse nursing students' competence development – Qualitativestudy. Nurse Educ. Today 2024, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wannarit, L.-O.; Ritudom, B. Psychometric properties of the Thai Qualifications Framework for Higher Education instrument among Royal Thai Air Force nurse stakeholders. Belitung Nurs. J. 2024, 10, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckner, M.; Camp, S.; Murabito, S. Outcomes of Concept-Based Curricula: An Integrative Review. J. Nurs. Educ. 2024, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boero, P.; Trizano-Hermosilla, I.; Vinet, E.V.; Navarro, G. Inventory of Socially Responsible Behaviors in Chilean University Students. Rev. Iberoam. Diagn. Eval. Aval. Psicol. 2020, 57, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.J. Psychometric Validity. In The Wiley Handbook of Psychometric Testing; Irwing, P., Booth, T., Hughes, D.J., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2018; pp. 751–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, P.J.; Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Hernández-Dorado, A.; Muñiz, J. Decalogue for the Factor Analysis of Test Items. Psicothema 2022, 34, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, A.D.; Yu, C.C. Descriptive Statistics for Modern Test Score Distributions: Skewness, Kurtosis, Discreteness, and Ceiling Effects. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2015, 75, 365–388, M.; González, R.; Peralta, C. Formación en responsabilidad social en estudiantes universitarios: un estudio comparativo. Rev. Educ. Super. 2019, 48, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F.; Cerny, B.A. Factor Analysis of the Image Correlation Matrix. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1979, 39, 711–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloret-Segura, S.; Ferreres-Traver, A.; Hernández-Baeza, A.; Tomás-Marco, I. Exploratory Item Factor Analysis: A practical guide revised and updated. An. Psicol. 2014, 30, 1151–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, P.J.; Lorenzo-Seva, U. Program FACTOR at 10: Origins, development and future directions. Psicothema 2017, 29, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang-Wallentin, F.; Jöreskog, K.G.; Luo, H. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Ordinal Variables With Misspecified Models. Struct. Equ. Model. 2010, 17, 392–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Ferrando, P.J. MSA: the forgotten index for identifying inappropriate items before computing exploratory item factor analysis. Methodology 2021, 17, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velicer, W.F.; Fava, J.L. Affects of variable and subject sampling on factor pattern recovery. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Timmerman, M.E.; Kiers, H.A.L. The Hull method for selecting the number of common factors. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2011, 46, 340–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyriazos, T.A. Applied Psychometrics: Sample Size and Sample Power Considerations in Factor Analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in General. Psychology 2018, 9, 2207–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J. Assessing goodness of fit in confirmatory factor analysis. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2005, 37, 240–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the Fit of Structural Equation Models: Tests of Significance and Descriptive Goodness-of-Fit Measures. Methods Psychol. Res. 2003, 8, 23–74. Disponible en: https://www.stats.ox.ac.uk/~snijders/mpr_Schermelleh.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Kalkan, Ö.K.; Kelecioğlu, H. The effect of sample size on parametric and nonparametric factor analytical methods. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2016, 16, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegalajar-Palomino, M.C.; Martínez-Valdivia, E.; Burgos-García, A. Análisis de la responsabilidad social en estudiantes universitarios de educación. Form. Univ. 2021, 14, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Pereira, M.G.; Pinto-Loria, M.L.; Hernández-Payán, E. Responsabilidad social: desarrollo y validación de una escala para estudiantes universitarios. Psicumex 2022, 12, e447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, R.H. A New Asymmetric Measure of Association for Ordinal Variables. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1962, 27, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, E. Guidelines to Statistical Evaluation of Data from Rating Scales and Questionnaires. J. Rehabil. Med. 2000, 32, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, E.J.; Harrington, K.M.; Clark, S.L.; Miller, M.W. Sample Size Requirements for Structural Equation Models: An Evaluation of Power, Bias, and Solution Propriety. Educational and Psychological Measurement 2013, 73, 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Statistics Institute. Population and Housing Census; Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas de Chile. Available online: https://www.ine.cl/estadisticas/sociales/censos-de-poblacion-y-vivienda/censo-de-poblacion-y-vivienda (accessed on 9 August 2023).

- National Education Council. Regional INDICES; Consejo Nacional de Educación de Chile. Available online: https://www.cned.cl/indices_New_~/regional.php (accessed on 9 August 2023).

- Dube, B.M.; Mtshali, N.G. Stakeholders' perspectives on competency-based education program in Africa: A qualitative study. Health SA Gesondheid 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).