1. Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a debilitating neuromuscular disease characterized by the progressive degeneration of motor neurons in the spinal cord and brain, accompanied by severe skeletal muscle atrophy [

1]. ALS patients experience rapid muscle wasting, and the majority succumb to the disease within 2-5 years of diagnosis, primarily due to respiratory failure. The annual incidence of ALS ranges from 1 to 2.6 cases per 100,000 persons, with a prevalence of approximately 11.8 per 100,000 in the United States [

2,

3]. Despite extensive research, effective therapeutic options for ALS remain unavailable. Emerging studies indicate that skeletal muscle defects in ALS, beyond being a consequence of motor neuron loss, can retrogradely impair motor neuron health. This bidirectional role contributes to disease progression, positioning skeletal muscle as an accessible and promising therapeutic target [

4].

Dysregulated inflammation in ALS-affected skeletal muscle is a significant pathological factor that disrupts the local cellular microenvironment and destabilizes the balance between protein synthesis and degradation [

5,

6]. Aberrant activation of inflammatory signaling pathways, including the Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NF-κB) pathway, drives this imbalance by promoting muscle protein breakdown and accelerating muscle wasting [

7,

8]. Furthermore, chronic inflammation hampers muscle regeneration by impairing the regenerative capacity of muscle stem cells and promoting fibrosis and fat infiltration. Notably, sustained inflammation prevents the transition of macrophages from a pro-inflammatory (M1 macrophage) to an anti-inflammatory (M2 macrophage) phenotype. Instead, macrophages adopt a hybrid profile that is unable to effectively clear damaged tissue debris, inhibits angiogenesis, and suppresses muscle stem cell activity necessary for tissue repair. Moreover, these macrophages may release profibrotic factors, such as transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), which exacerbate pathological fibrosis [

9]. Intramuscular administration of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 has been shown to reduce muscle atrophy in ALS mice by facilitating macrophage polarization and activating muscle stem cells [

10]. In this study, we investigate a therapeutic strategy targeting the inflammatory microenvironment in ALS-afflicted skeletal muscle, with the goal of mitigating muscle degradation and promoting regeneration as a potential treatment for ALS.

Skeletal muscle possesses an intrinsic ability to regenerate in response to acute injuries. This process is well-coordinated, involving several interrelated and time-sensitive phases, such as necrosis of injured muscle cells, inflammation, regeneration, maturation, and ultimately, functional recovery. A single intramuscular injection of the snake venom toxin cardiotoxin (CTX) is widely used to induce acute skeletal muscle regeneration in mice and a distinctive anti-inflammatory environment emerges by day 14 post-injection (CTXD14SkM) [

11]. At this stage, coordinated interactions among various cell types actively support muscle repair. Predominant among these are anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages, which secrete cytokines such as IL-10 and growth factors that drive muscle stem cell differentiation and the maturation of new myofibers [

12,

13]. Furthermore, M2 macrophages aid in resolving inflammation by suppressing the pro-inflammatory signaling that predominates in the initial phases of injury [

14].

Extracellular vesicles (EVs), essential mediators of intercellular communication, inherit bioactive molecules such as proteins and nucleic acids from their parent cells. This enables them to mirror the functional characteristics of their cells of origin, facilitating diverse biological effects [

15]. EVs secreted by cells within the anti-inflammatory milieu of CTXD14SkM, including M2 macrophages and other immune cells, myogenic progenitor cells, and regenerating myofibers, are likely enriched with factors possessing anti-inflammatory properties. Therefore, in this study, we isolate EVs derived from CTXD14SkM (CTXD14SkM-EVs) and assess their therapeutic potential in mitigating inflammation and promoting muscle regeneration and repair in an ALS mouse model.

Here, we showed that CTXD14SkM-EVs enhance myoblast differentiation and fusion in a muscle atrophy cellular model induced by the pro-inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), highlighting their anti-inflammatory and myogenesis-promoting potential. Furthermore, intramuscular administration of CTXD14SkM-EVs effectively mitigated muscle atrophy and increased muscle fiber size in a well-established ALS mouse model with denervated muscle atrophy. Notably, EV-treated mice exhibited an increased number of regenerating myofibers, accompanied by elevated expression of key myogenic regulatory factors, indicating active muscle regeneration. Additionally, EV treatment facilitated a shift in macrophage polarization from the pro-inflammatory M1 state to the anti-inflammatory M2 state and suppressed activation of the pro-inflammatory NF-κB signaling pathway observed in ALS-afflicted skeletal muscles. These findings underscore the therapeutic potential of EVs derived from regenerating muscle in alleviating inflammation and enhancing muscle regeneration, offering a promising strategy for treating muscle atrophy associated with ALS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Treatment

Experiments were conducted using transgenic mice overexpressing human SOD1 with a Gly93-Ala mutation (SOD1G93A) (strain designation B6SJL–TgN[SOD1–G93A]1Gur, stock number 002726) and wild-type (WT) B6SJL mice, both obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). All animals were maintained in a controlled environment under standard laboratory conditions. Five SOD1G93A mice received an intramuscular injection of about 4.4 × 10^9 CTXD14SkM-EVs suspended in 20 µL Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (cytiva, Cat#SH30028.03) into the tibialis anterior (TA) and gastrocnemius (GAS) muscles of one limb. As a control, 20 µL of PBS was injected into the TA and GAS muscles of the opposite limb. Treatments were administered weekly, beginning at the pre-symptomatic stage (day 66), with muscle tissue collected at the late symptomatic stage (day 119).

2.2. CTXD14SkM-EVs Isolation

To isolate CTXSkM-EVs from acutely injured skeletal muscle, cardiotoxin (CTX) (10 µM, 20 µL) (Millipore Sigma, Cat#217503) was injected intramuscularly into the TA and GAS muscles of approximately 2-month-old WT mice. Fourteen days post-injury, the TA and GAS muscles were harvested and sectioned into 2-3 mm pieces using a scalpel. The sliced muscles were then placed in a digestion solution containing 2 mg/mL Collagenase Type II (Worthington-Biochem, Cat#LS004176) in DMEM with 100 U/mL Penicillin/Streptomycin (P-S) (Gibco, Cat#15140122), with 500 µL used for each TA muscle and 1 mL for each GAS muscle. The tissue was rotated in the digestion solution at 37°C for 24 hours. After digestion, the tissue mixture was centrifuged at 1,000 xg for 30 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected and filtered through a 0.8 µm filter. CTXD14SkM-EVs were then isolated from the filtered supernatant by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 xg for 1 hour at 4°C, and the resulting EV pellet was resuspended in PBS.

2.3. MemGlow Assessment

The size and concentration of the isolated EVs were assessed using nano-flow cytometry on the Flow NanoAnalyzer (NanoFCM, Xiamen, China). To determine the proportion of particles with a lipid membrane, the EVs were stained with 2 nM MemGlow 488 (Cytoskeleton, Denver, CO), a fluorogenic membrane probe, for 10 minutes. Fluorescence was then measured using the Flow NanoAnalyzer

2.4. C2C12 Differentiation

C2C12 myoblast (CRL-1772™, ATCC), were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 U/mL P-S. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with a 5% CO₂/95% air atmosphere. C2C12 cells were seeded at 100,000 cells per well in the 24-well plate with growth medium. After 24 hours, the growth medium was replaced into differentiation medium (DMEM supplemented with 2% horse serum and 100 U/mL P-S) to initiate differentiation. Three treatment conditions were applied: (1) differentiation medium only, (2) differentiation medium with 5 ng/ml TNF-α and PBS, (3) differentiation medium with 5 ng/mL TNF-α and approximately 1.8 × 10^8 CTXD14SkM-EVs. After 3 days of treatment, cells were evaluated for myosin heavy chain (MHC) expression.

2.5. Immunostaining of Cells

C2C12 were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 10 minutes at room temperature, followed by permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. Cells were then blocked in 10% FBS in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. The primary antibody, MF20 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, DSHB), was diluted in a blocking buffer and applied overnight at 4°C. The following day, cells were washed three times with PBS to remove any excess primary antibody. A secondary antibody, donkey anti-mouse (Abcam, Cat# ab150108) diluted in PBS, was then applied for 1 hour at room temperature. After incubation, cells were washed three additional times with PBS, and DAPI was applied for nuclear counterstaining. Fluorescence images were captured using a fluorescence microscope.

2.6. Histology

TA muscle tissues were embedded in OCT compound and frozen. Cryosections (10 µm) were prepared, mounted on glass slides, and air-dried. Sections were fixed in 4% PFA for 10 minutes, rinsed in PBS, and stained with hematoxylin (Harris, Sigma, Cat No. HHS32) for 1 minute. After rinsing, sections were stained with eosin (Sigma, Cat No. HT110316) for 30 seconds, followed by a brief wash in distilled water. Slides were then dehydrated through graded ethanol concentrations, cleared with xylene, and coverslipped with a permanent mounting medium. Images were captured using a light microscope.

2.7. Immunohistochemistry of Skeletal Muscle

TA muscle tissues were embedded in OCT, frozen, and cryosectioned at 10 µm thickness. Sections were mounted on glass slides, air-dried, and fixed with 4% PFA for 10 minutes, followed by PBS rinses. Tissues were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes, then blocked in 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. Primary antibody against Laminin (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# L9393) was applied in the blocking buffer and incubated overnight at 4°C. The next day, sections were washed in PBS and incubated with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark. After final PBS washes, sections were mounted with an antifade mounting medium containing DAPI for nuclear counterstaining. Images were captured using a fluorescence microscope. For M1/2 macrophage staining, longitudinal section of TA muscle, 20 µm thick, were collected and fixed in 4% PFA for 10 minutes. Tissues were then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes, followed by blocking in the solution of 10% FBS and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. Primary antibodies anti-CD11b (eBioscience, Cat#14-0112-81), iNOS (Bio-Techne, Cat#NB300-605SS), and anti-mannose receptor (Abcam, Cat#ab64693), were prepared in the blocking buffer and applied to the tissue sections, which were incubated overnight at 4°C. The following day, sections were washed with PBS and incubated with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies: Alex Fluor 488 anti-Rat (Invitrogen, Cat#53-4031-80) and Alex Fluor 594 anti-Rabbit (Abcam, Cat#ab150080) for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark. Finally, images were captured using a fluorescence microscope.

2.8. Western Blotting

Samples were lysed in RIPA buffer (Millipore Sigma, Cat#20-188) supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitors. Proteins were separated via SDS-PAGE gel, transferred onto PVDF membranes, blocked with 5% FBS in PBST (PBS with 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 hour, and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies: anti-Myogenin (Invitrogen, Cat#PA5-87235), anti-NF-κB p65 (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat#8242), anti-Phospho-NF-κB p65 (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat#3033), anti-beta-actin (Cell Signaling, Cat#4970S), anti-Vinculin (Cell Signaling, Cat#2148S), and anti-GAPDH (Cell Signaling, Cat#97166T). Membranes were then incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) secondary antibody (Promega, Cat#W4011) or HRP-conjugated anti-Mouse IgG (Cell Signaling, Cat#7076S) for 1 hour at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized using a ChemiDoc™ MP imaging system (Bio-Rad) with WesternBright ECL chemiluminescent substrate (Fisher Scientific, Cat#NC0930892).

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed using GraphPad Prism version 10.0 (GraphPad Software). A two-tailed, unpaired Student’s Paired t-test was used for comparisons between two treatment groups. For comparisons among more than two groups with a single variable, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test was applied for multiple comparisons. All data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was set at * P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.005, *** p < 0.0001, **** P ≤ 0.0001.

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and Characterization of CTXD14SkM-EVs

To isolate and enrich CTXD14SkM-EVs, skeletal muscle from 3-month-old wild-type mice were dissected 14 days after acute injury induced by intramuscular injection of CTX. The muscles underwent enzymatic dissociation, filtration, and sequential ultracentrifugation (

Fig. 1A). Nanoflow cytometry was used to assess the concentration and size distribution of these isolated EVs, confirming a size range of 50-200 nm, consistent with reported extracellular vesicles, particularly exosomes (

Fig. 1B). These isolated EVs were then treated with MemGlow dye to label the lipid bilayer, and nanoflow cytometry-based analysis revealed that around 90% of the particles are fluorescent and lipid-enclosed structures, indicating the high-purity of these EV samples (

Fig. 1C). Compared to EVs derived from wild-type mouse skeletal muscle, these derived from acutely injured skeletal muscle showed no significant difference in size distribution (Figure S1). In addition, the morphology of CTXD14SkM-EVs were identified by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (JEM-1011, JEOL, Japan) (

Fig. 1D).

3.2. CTXD14SkM-EVs promote Myoblast Differentiation in a Cellular Muscle Atrophy Model Induced by Proinflammatory Cytokine TNF-α.

To investigate the therapeutic potential of CTXD14SkM-EVs in mitigating muscle atrophy, we employed a well-established myotube atrophy model using C2C12 myoblasts. This model was induced by TNF-α, a pro-inflammatory cytokine elevated in ALS and other muscle-wasting disorders. TNF-α is known to impair myogenic differentiation and activate catabolic pathways, including the ubiquitin-proteasome system and NF-κB signaling, leading to the downregulation of essential myogenic markers such as myoblast determination protein 1 (MyoD) and myogenin, while promoting the degradation of muscle structural proteins [16-18]. Thus, TNF-α-induced muscle atrophy models are widely used to study muscle degeneration and evaluate therapeutic interventions. In this study, TNF-α was administered during C2C12 myoblasts differentiation to inhibit myogenic progression and induce an atrophic state. To assess the protective effects of CTXD14SkM-EVs, these EVs were added concurrently with TNF-α. After 72 hours of treatment, myotubes were immunostained for myosin heavy chain (MHC), a hallmark of mature muscle fibers (

Fig. 2A, B). Our results showed that TNF-α treatment markedly reduced both myoblast differentiation and fusion indices, consistent with its known atrophic effects. Strikingly, CTXD14SkM-EVs treatment significantly rescued both indices under TNF-α-induced condition, indicating a protective effect on myogenic differentiation and myotube formation (

Fig. 2C, D). These findings highlight the potential of CTXD14SkM-EVs as a therapeutic approach to combat inflammation-driven muscle atrophy.

3.3. CTXD14SkM-EVs Alleviate ALS-related Muscle Atrophy in SOD1G93A Mice

To assess the therapeutic effects of CTXD14SkM-EVs on mitigating inflammation-driven muscle atrophy

in vivo, we utilized a well-established ALS mouse model expressing the human SOD1 protein with the pathogenic missense mutation G93A (SOD1

G93A) [

19]. The SOD1

G93A mice recapitulate ALS-related muscle atrophy, accompanied by inflammation and impaired muscle regeneration. CTXD14SkM-EVs were intramuscularly injected into the tibialis anterior (TA) and gastrocnemius (GAS) muscles of one limb in SOD1

G93A mice, while the contralateral limb received PBS as a control. The treatment began at the pre-symptomatic stage (postnatal day 66, P66) and continued weekly until muscle tissues were collected at the late symptomatic stage (P119) for analysis (

Fig. 3A). First, the muscle weight-to-body weight ratios for the TA and GAS muscles were evaluated. Notably, both the TA and GAS muscles treated with CTXD14SkM-EVs exhibited significantly increased muscle weights compared to their PBS-treated counterparts (

Fig. 3B, C). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of TA muscle fibres revealed that, as expected, SOD1

G93A mice had smaller muscle fibre cross-sectional areas (CSA) compared to wild-type mice. In contrast, the CTXD14SkM-EVs treated group showed increased muscle fibre size and abundant centrally located myonuclei compared to PBS-treated SOD1

G93A mice (

Fig. 3D).

To further investigate CSA distribution, immunostaining for Laminin, a myofiber basement member marker, was performed (

Fig. 4A). TA muscles from the CTXD14SkM-EV-treated group exhibited a reduced proportion of small CSA myofibers and an increased proportion of larger CSA myofibers compared to the PBS-treated control group (

Fig. 4B). The average CSA was significantly greater in the CTXD14SkM-EVs-treated group than in the PBS-treated group (

Fig. 4C, D), indicating that CTXD14SkM-EVs may mitigate muscle atrophy in SOD1

G93A mice. Furthermore, the percentage of myofibers with centralized nuclei, an indicator of active regeneration, was significantly higher in the CTXD14SkM-EVs-treated group compared to the PBS-treated group, suggesting that CTXD14SkM-EVs may promote muscle stem cell-mediated regeneration (

Fig. 4E). Additionally, the protein level of Myogenin, a myogenic marker linked to the differentiation commitment of muscle stem cells, showed an increasing trend in the EV-treated group, supporting the regenerative potential of CTXD14SkM-EVs (

Fig. 4F, G).

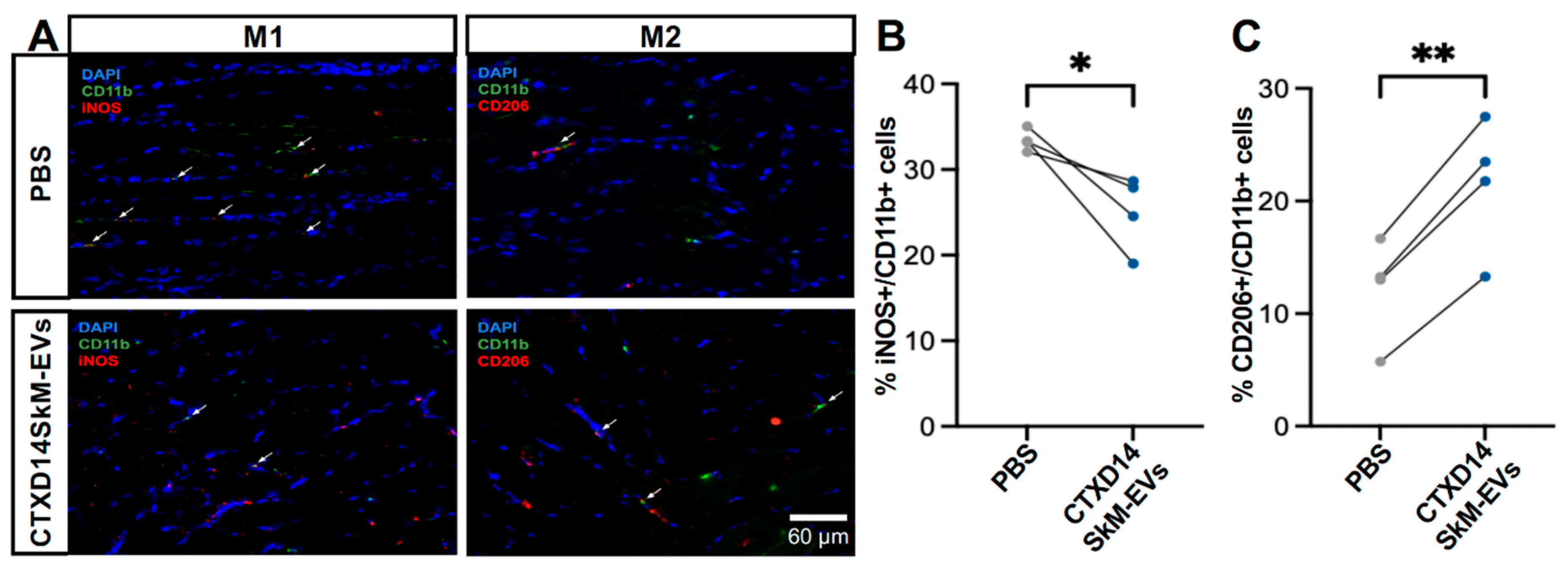

3.4. CTXD14SkM-EVs Enhance M2 Macrophage Polarization in ALS-Affected Skeletal Muscle

Given the anti-inflammatory microenvironment predominantly driven by M2 macrophages in the skeletal muscles 14 days post-acute injury (CTXD14SkM), we hypothesized that EVs derived from CTXD14SkM would inherit the capacity to promote macrophage polarization towards an anti-inflammatory and pro-regenerative state [

11,

13]. To test this hypothesis, we performed immunostaining for M1 and M2 macrophage markers in the TA muscles of SOD1

G93A mice treated with either CTXD14SkM-EV or PBS (

Fig. 5A). The results showed that CTXD14SkM-EV treatment significantly increased the proportion of M2 macrophages (CD206+/CD11b+) while reducing the presence of M1 macrophages (iNOS+/CD11b+) compared to PBS treatment (

Fig. 5B, C). These findings indicate that CTXD14SkM-EVs effectively promote the polarization of macrophages toward a pro-regenerative M2 phenotype.

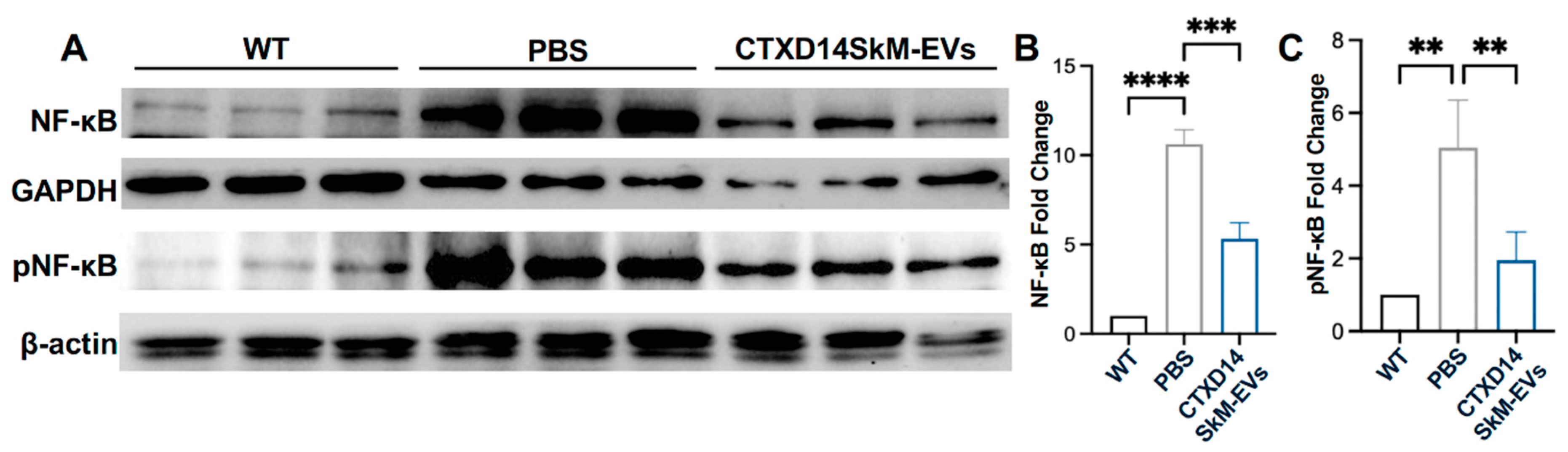

3.5. CTXD14SkM-EVs Suppress NF-κB Pathway Activation in the Skeletal Muscle of ALS Mice

Aberrant activation of NF-κB signalling in ALS-afflicted skeletal muscles is a critical driver of chronic inflammation, suppression of myogenic regulatory factors, and upregulation of proteolytic enzymes, collectively contributing to muscle degeneration and wasting [6,8,20-23]. Thus, targeting NF-κB signaling represents a promising therapeutic strategy to attenuate inflammation and mitigate muscle atrophy in ALS. To assess the impact of CTXD14SkM-EVs treatment on NF-κB signaling in the TA muscle of SOD1

G93A mice, we performed western blot analysis to quantify the expression of total NF-κB, the active phosphorylated format of NF-κB (pNF-κB), and the loading controls GAPDH and β-actin across three experimental groups: wild-type (WT) mice, PBS-treated ALS mice, and CTXD14SkM-EV-treated ALS mice. As expected, both NF-κB and pNF-κB protein levels were significantly elevated in the TA muscle of the PBS-treated ALS mice compared to the WT group, indicating a heightened inflammatory response in ALS-affected skeletal muscles. Notably, CTXD14SkM-EV treatment markedly downregulated both NF-κB and pNF-κB protein levels in ALS, bringing them closer to baseline levels observed in WT mice (

Fig. 6A, B, C). Meanwhile, the CTXD14SkM-EV-treated group exhibited an increased expression of key markers associated with M2 macrophage polarization and anti-inflammatory responses, including Interleukin-10 (IL-10), Chitinase-Like Protein 3 (Chil3), and Arginase 1 (Arg1) (Figure S2). These findings suggest that CTXD14SkM-EV treatment effectively suppresses NF-κB signaling in the skeletal muscles of SOD1

G93A mice, supporting its potential to mitigate inflammation and muscle atrophy in ALS.

4. Discussion

This study explores the therapeutic potential of EVs derived from regenerating skeletal muscle for treating ALS-afflicted muscle atrophy. Most current pharmacological treatments for ALS focus on targeting neuronal deficits, showing limited clinical promise. Given the importance of muscle atrophy in ALS progression and pathogenesis, approaches targeting muscle wasting are of high therapeutic interest. Multiple pathogenic mechanisms are known to be involved in ALS-related motor defects and muscle atrophy, including chronic inflammation, impaired regeneration, proteostasis dysregulation, mitochondrial and metabolic defects. Current therapeutic strategies targeting ALS-afflicted muscle defects often focus on one or few misregulated pathways. Our findings demonstrated that regenerating skeletal muscle-derived EVs provide a multifaceted strategy to counter muscle atrophy in an ALS mouse model (SOD1G93A) by promoting muscle regeneration, shifting macrophage polarization towards an anti-inflammatory phenotype, and downregulating the pro-inflammatory NF-κB signaling pathway essential for protein homeostasis. These EVs (CTXD14SkM-EVs) are derived from cells within the regenerating skeletal muscle 14 days post-acute injury, the peak phase of regeneration facilitated by the collective activities of residing cells, such as macrophages predominantly in an anti-inflammatory M2 state, activated muscle stem cells, and newly formed muscle fibers. EVs are known to inherit molecular cargos from their sourced cells and mediate regulatory functions in recipient cells. Recently, EVs have been proved to be key mediators of the therapeutic effects of stem cells, instead of stem cell engrafting and differentiation. As expected, the CTXD14SkM-EVs may carry and transfer functional molecules from cells within the regenerating skeletal muscle to recipient cells in ALS-affected skeletal muscle, facilitating an anti-inflammatory and pro-regenerative environment for muscle repair.

In an ALS-like cellular models of muscle wasting, the CTXD14SkM-EVs mitigated the detrimental effects induced by the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α on myoblasts, as evidenced by improved differentiation and fusion indices. Moreover, in vivo, intramuscular administration of CTXD14SkM-EVs alleviated ALS-related muscle atrophy in SOD1G93A mice, as indicated by increased muscle mass and muscle fibre size. Meanwhile, a higher percentage of myofibers with centralized nuclei was observed post EV-treatment, suggesting active muscle regeneration. These results suggest that CTXD14SkM-EVs may counteract inflammation-induced muscle wasting by enhancing myoblast function and promoting muscle regeneration.

The anti-inflammatory properties of CTXD14SkM-EVs were further supported by their ability to modulate macrophage polarization and regulate NF-κB signaling. In ALS-affected skeletal muscle, chronic inflammation involves a disrupted transition of macrophages from the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype, which clears debris and damaged tissue, to the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, which promotes muscle regeneration and tissue repair. This prolonged pro-inflammatory state may not only impair muscle stem cell function for regeneration but also exacerbate muscle protein breakdown, leading to muscle atrophy [

24,

25]. CTXD14SkM-EVs effectively promoted a phenotypic shift in macrophages from the M1 to M2 phenotype in ALS-affected skeletal muscle. This shift may may alleviate the inflammatory burden and create a more favourable microenvironment for muscle regeneration and repair. As such, CTXD14SkM-EVs hold significant potential as modulators of immune responses in ALS therapy. In addition to modulating macrophage populations, CTXD14SkM-EVs also significantly suppressed the excessive activation of the NF-κB pathway in ALS skeletal muscles. Specifically, they downregulated the expression of both NF-κB and its phosphorylated form (pNF-κB) in the skeletal muscles of SOD1

G93A mice. Persistent activation of NF-κB in ALS muscle is associated with elevated inflammation, increased proteolytic activity, reduced expression of myogenic regulatory factors, and impaired muscle regeneration, collectively driving muscle atrophy [

7,

8]. By downregulating NF-κB signaling, CTXD14SkM-EVs may interrupt these pathogenic cascades, thereby reducing chronic inflammation, enhancing myogenic differentiation, and decreasing protein degradation. Together, these therapeutic effects contribute to muscle repair and functional recovery in ALS.

This study demonstrates that CTXD14SkM-EVs possess therapeutic potential to mitigate ALS-related muscle atrophy, providing valuable insights into leveraging EVs derived from regenerating skeletal tissue to address multiple pathogenic processes underlying muscle degeneration. These findings lay a strong foundation for developing EV-based therapies targeting muscle atrophy in ALS, which could complement therapeutic strategies focusing on neuroprotection. Future research should prioritize identifying the molecular cargo within CTXD14SkM-EVs responsible for these therapeutic effects, as well as optimizing delivery and dosing strategies to enhance their efficacy in treating ALS and other muscle-wasting diseases.

Author Contributions

Y.Y. and J. G. conceptualized and designed the study, wrote the manuscript. J.G. carried out most of the experiments. R. H. and Y. Z. performed extracellular characterization, A. S., E. S. and K. C. involved in data collection and analysis.

Funding

This research was supported by startup funds from the University of Georgia (to Y.Y.).

Ethics declarationsEthics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments were approved in

accordance with current guidelines for the care of laboratory animals and were approved by the appropriate

committees of University of Georgia (Approval ID: A2023 05-006-Y1-A0).

Consent for publication

All authors agree to publish this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors have any significant conflicts of interest regarding the contents of this paper.

References

- Masrori, P.; Van Damme, P. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a clinical review. Eur J Neurol 2020, 27, 1918-1929. [CrossRef]

- Talbott, E.O.; Malek, A.M.; Lacomis, D. The epidemiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Handb Clin Neurol 2016, 138, 225-238.

- Wolfson, C.; Gauvin, D.E.; Ishola, F.; Oskoui, M. Global Prevalence and Incidence of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. Neurology 2023, 101, e613-e623. [CrossRef]

- Kubat, G.B.; Picone, P. Skeletal muscle dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a mitochondrial perspective and therapeutic approaches. Neurol Sci 2024, 45, 4121-4131. [CrossRef]

- Al-Sarraj, S.; King, A.; Cleveland, M.; Pradat, P.F.; Corse, A.; Rothstein, J.D.; Leigh, P.N.; Abila, B.; Bates, S.; Wurthner, J.; et al. Mitochondrial abnormalities and low grade inflammation are present in the skeletal muscle of a minority of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; an observational myopathology study. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2014, 2, 165. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Li, M.; Chang, M.; Liu, R.; Qiu, J.; Wang, K.; Deng, C.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, J.; Wang, W.; et al. Inflammation: Roles in Skeletal Muscle Atrophy. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Frantz, J.D.; Tawa, N.E., Jr.; Melendez, P.A.; Oh, B.C.; Lidov, H.G.; Hasselgren, P.O.; Frontera, W.R.; Lee, J.; Glass, D.J.; et al. IKKbeta/NF-kappaB activation causes severe muscle wasting in mice. Cell 2004, 119, 285-298.

- Kallstig, E.; McCabe, B.D.; Schneider, B.L. The Links between ALS and NF-kappaB. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22.

- Duchesne, E.; Dufresne, S.S.; Dumont, N.A. Impact of Inflammation and Anti-inflammatory Modalities on Skeletal Muscle Healing: From Fundamental Research to the Clinic. Phys Ther 2017, 97, 807-817. [CrossRef]

- Fabbrizio, P.; Margotta, C.; D'Agostino, J.; Suanno, G.; Quetti, L.; Bendotti, C.; Nardo, G. Intramuscular IL-10 Administration Enhances the Activity of Myogenic Precursor Cells and Improves Motor Function in ALS Mouse Model. Cells 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, J.; Liu, Y. Skeletal Muscle Regeneration in Cardiotoxin-Induced Muscle Injury Models. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Lan, H.; Jian, X.; Huang, J.; Wang, H.; Hu, J.; Liao, H. Myofiber directs macrophages IL-10-Vav1-Rac1 efferocytosis pathway in inflamed muscle following CTX myoinjury by activating the intrinsic TGF-beta signaling. Cell Commun Signal 2023, 21, 168.

- Wang, X.; Zhou, L. The Many Roles of Macrophages in Skeletal Muscle Injury and Repair. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 952249. [CrossRef]

- Mosser, D.M.; Edwards, J.P. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol 2008, 8, 958-969. [CrossRef]

- Yanez-Mo, M.; Siljander, P.R.; Andreu, Z.; Zavec, A.B.; Borras, F.E.; Buzas, E.I.; Buzas, K.; Casal, E.; Cappello, F.; Carvalho, J.; et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J Extracell Vesicles 2015, 4, 27066.

- Chandran, R.; Knobloch, T.J.; Anghelina, M.; Agarwal, S. Biomechanical signals upregulate myogenic gene induction in the presence or absence of inflammation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2007, 293, C267-276. [CrossRef]

- Powrozek, T.; Pigon-Zajac, D.; Mazurek, M.; Ochieng Otieno, M.; Rahnama-Hezavah, M.; Malecka-Massalska, T. TNF-alpha Induced Myotube Atrophy in C2C12 Cell Line Uncovers Putative Inflammatory-Related lncRNAs Mediating Muscle Wasting. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Yang, S.T.; Wang, J.J.; Zhou, J.; Xing, S.S.; Shen, C.C.; Wang, X.X.; Yue, Y.X.; Song, J.; Chen, M.; et al. TNF alpha inhibits myogenic differentiation of C2C12 cells through NF-kappaB activation and impairment of IGF-1 signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2015, 458, 790-795.

- Gurney, M.E.; Pu, H.; Chiu, A.Y.; Dal Canto, M.C.; Polchow, C.Y.; Alexander, D.D.; Caliendo, J.; Hentati, A.; Kwon, Y.W.; Deng, H.X.; et al. Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science 1994, 264, 1772-1775. [CrossRef]

- Capitanio, D.; Vasso, M.; Ratti, A.; Grignaschi, G.; Volta, M.; Moriggi, M.; Daleno, C.; Bendotti, C.; Silani, V.; Gelfi, C. Molecular signatures of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis disease progression in hind and forelimb muscles of an SOD1(G93A) mouse model. Antioxid Redox Signal 2012, 17, 1333-1350.

- Li, H.; Malhotra, S.; Kumar, A. Nuclear factor-kappa B signaling in skeletal muscle atrophy. J Mol Med (Berl) 2008, 86, 1113-1126. [CrossRef]

- Aishwarya, R.; Abdullah, C.S.; Remex, N.S.; Nitu, S.; Hartman, B.; King, J.; Bhuiyan, M.A.N.; Rom, O.; Miriyala, S.; Panchatcharam, M.; et al. Pathological Sequelae Associated with Skeletal Muscle Atrophy and Histopathology in G93A*SOD1 Mice. Muscles 2023, 2, 51-74. [CrossRef]

- Sandri, M. Protein breakdown in muscle wasting: role of autophagy-lysosome and ubiquitin-proteasome. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2013, 45, 2121-2129. [CrossRef]

- Carata, E.; Muci, M.; Di Giulio, S.; Mariano, S.; Panzarini, E. Looking to the Future of the Role of Macrophages and Extracellular Vesicles in Neuroinflammation in ALS. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Van Dyke, J.M.; Smit-Oistad, I.M.; Macrander, C.; Krakora, D.; Meyer, M.G.; Suzuki, M. Macrophage-mediated inflammation and glial response in the skeletal muscle of a rat model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Exp Neurol 2016, 277, 275-282. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Isolation and characterization of CTXD14SkM-EVs. (A) Schematic overview of the isolation process for CTXD14SkM-EVs. (B) Size distribution of EVs. (C) MemGlow staining of EVs: red dots represent the MemGlow-positive population, blue dots represent the MemGlow-negative population. Side scatter (SS) and FITC intensity of the EVs were detected using NanoFCM. (D) Contrast image of CTXD14SkM-EVs sample. Scale bar: 100 µm.

Figure 1.

Isolation and characterization of CTXD14SkM-EVs. (A) Schematic overview of the isolation process for CTXD14SkM-EVs. (B) Size distribution of EVs. (C) MemGlow staining of EVs: red dots represent the MemGlow-positive population, blue dots represent the MemGlow-negative population. Side scatter (SS) and FITC intensity of the EVs were detected using NanoFCM. (D) Contrast image of CTXD14SkM-EVs sample. Scale bar: 100 µm.

Figure 2.

CTXD14SkM-EVs Promote Myoblast Differentiation in a cellular muscle atrophy model induced by proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α. (A) Schematic overview of C2C12 differentiation. (B) Immunostaining of MHC (green) and DAPI (blue) of in three groups: differentiation medium only, differentiation medium with 5 ng/mL TNF-α and PBS, differentiation medium with 5 ng/mL TNF-α and CTXD14SkM-EVs. Scale bar: 60 µm. (C) Differentiation index calculated as (number of MHC+ cells/total number of nuclei). (D) The Fusion index calculated as (number of nuclei in MHC+ cells with ≥2 nuclei/total number of nuclei). The experiment was repeated, and data are reported as means ± SEM. * P ≤ 0.05, **** p < 0.0001 by One-way ANOVA.

Figure 2.

CTXD14SkM-EVs Promote Myoblast Differentiation in a cellular muscle atrophy model induced by proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α. (A) Schematic overview of C2C12 differentiation. (B) Immunostaining of MHC (green) and DAPI (blue) of in three groups: differentiation medium only, differentiation medium with 5 ng/mL TNF-α and PBS, differentiation medium with 5 ng/mL TNF-α and CTXD14SkM-EVs. Scale bar: 60 µm. (C) Differentiation index calculated as (number of MHC+ cells/total number of nuclei). (D) The Fusion index calculated as (number of nuclei in MHC+ cells with ≥2 nuclei/total number of nuclei). The experiment was repeated, and data are reported as means ± SEM. * P ≤ 0.05, **** p < 0.0001 by One-way ANOVA.

Figure 3.

CTXD14SkM-EVs Alleviate Muscle Atrophy in SOD1G93A Mice. (A) Schematic overview of

CTXD14SkM-EVs and PBS treatment in SOD1G93A mice. (B) TA muscle weight to body weight ratio (n=4). Paired

Student’s t-test. **P ≤ 0.005. (C) GAS muscle weight to body weight ratio (n=4). Paired Student’s t-test. * P ≤ 0.05.

(D) H&E staining of TA muscle in two groups: SOD1G93A muscle treated with PBS and SOD1G93A muscle treated

with CTXD14SkM-EVs. Scale bar: 50 µm.

Figure 3.

CTXD14SkM-EVs Alleviate Muscle Atrophy in SOD1G93A Mice. (A) Schematic overview of

CTXD14SkM-EVs and PBS treatment in SOD1G93A mice. (B) TA muscle weight to body weight ratio (n=4). Paired

Student’s t-test. **P ≤ 0.005. (C) GAS muscle weight to body weight ratio (n=4). Paired Student’s t-test. * P ≤ 0.05.

(D) H&E staining of TA muscle in two groups: SOD1G93A muscle treated with PBS and SOD1G93A muscle treated

with CTXD14SkM-EVs. Scale bar: 50 µm.

Figure 4.

CTXD14SkM-EVs promote muscle regeneration in SOD1G93A Mice. (A) Immunostaining of Laminin (green) and DAPI (blue) in the three groups: WT muscle (n=3), PBS (n=4), CTXD14SkM-EVs (n=4). Scale bar: 70 µm (B) Myofiber size distribution in two groups: PBS (gray, n=4) and CTXD14SkM-EVs (blue, n=4). (C) Comparison of average CSA between PBS and CTXD14SkM-EVs treated groups, analysed by paired Student’s t-test. (D) Comparison of the percentage of CSA above 2000 µm² of among the three groups, analysed by one-way ANOVA. (E) Percentage of myofibers with central nuclei to total myofibers, analysed by one-Way ANOVA. (F) Western blot analysis of Myogenin protein level in WT (n=3), PBS (n=3), and CTXD14SkM-EVs (n=3) groups. (G) Myogenin protein levels among the three groups were quantified using ImageJ, and the results were analysed by one-way ANOVA. * P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.005, **** p < 0.0001.

Figure 4.

CTXD14SkM-EVs promote muscle regeneration in SOD1G93A Mice. (A) Immunostaining of Laminin (green) and DAPI (blue) in the three groups: WT muscle (n=3), PBS (n=4), CTXD14SkM-EVs (n=4). Scale bar: 70 µm (B) Myofiber size distribution in two groups: PBS (gray, n=4) and CTXD14SkM-EVs (blue, n=4). (C) Comparison of average CSA between PBS and CTXD14SkM-EVs treated groups, analysed by paired Student’s t-test. (D) Comparison of the percentage of CSA above 2000 µm² of among the three groups, analysed by one-way ANOVA. (E) Percentage of myofibers with central nuclei to total myofibers, analysed by one-Way ANOVA. (F) Western blot analysis of Myogenin protein level in WT (n=3), PBS (n=3), and CTXD14SkM-EVs (n=3) groups. (G) Myogenin protein levels among the three groups were quantified using ImageJ, and the results were analysed by one-way ANOVA. * P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.005, **** p < 0.0001.

Figure 5.

CTXD14SkM-EVs Enhance M2 Macrophage Polarization in ALS-affacted Skeletal Muscle. (A) Immunostaining of CD11b (green), iNOS (red), CD206 (red), and DAPI (blue) in TA muscle sections from PBS (n=4) and CTXD14SkM-EVs (n=4) groups. Scale bar: 60 µm (B) Comparison of the percentage of M1 macrophage (iNOS+/CD11b+) between the PBS and CTXD14SkM-EVs groups, analysed by paired Student’s t-test. (C) Comparison of the percentage of M2 macrophage (CD206+/CD11b+) between the PBS and CTXD14SkM-EVs groups, analysed by paired Student’s t-test. * P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.005.

Figure 5.

CTXD14SkM-EVs Enhance M2 Macrophage Polarization in ALS-affacted Skeletal Muscle. (A) Immunostaining of CD11b (green), iNOS (red), CD206 (red), and DAPI (blue) in TA muscle sections from PBS (n=4) and CTXD14SkM-EVs (n=4) groups. Scale bar: 60 µm (B) Comparison of the percentage of M1 macrophage (iNOS+/CD11b+) between the PBS and CTXD14SkM-EVs groups, analysed by paired Student’s t-test. (C) Comparison of the percentage of M2 macrophage (CD206+/CD11b+) between the PBS and CTXD14SkM-EVs groups, analysed by paired Student’s t-test. * P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.005.

Figure 6.

CTXD14SkM-EVs Suppress NF-κB Pathway Activation in the Skeletal Muscle of SOD1G93A Mice. (A) Western blot analysis of NF-κB, pNF-κB, GAPDH, and β-actin proteins for three groups: WT (n=3), PBS (n=3), and CTXD14SkM-EVs (n=3). (B) Quantification of NF-κB protein levels among the three groups using Image J, statistical analysis by one-way ANOVA. (C) Quantification of pNF-κB protein levels among the three groups using Image J, statistical analysis by one-way ANOVA. **P ≤ 0.005, *** p < 0.0001, **** p < 0.0001.

Figure 6.

CTXD14SkM-EVs Suppress NF-κB Pathway Activation in the Skeletal Muscle of SOD1G93A Mice. (A) Western blot analysis of NF-κB, pNF-κB, GAPDH, and β-actin proteins for three groups: WT (n=3), PBS (n=3), and CTXD14SkM-EVs (n=3). (B) Quantification of NF-κB protein levels among the three groups using Image J, statistical analysis by one-way ANOVA. (C) Quantification of pNF-κB protein levels among the three groups using Image J, statistical analysis by one-way ANOVA. **P ≤ 0.005, *** p < 0.0001, **** p < 0.0001.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).