Submitted:

06 February 2025

Posted:

07 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

High-fat diets (HFDs) compromise male fertility, and cholesterol dysregulation is implicated. Sterol regulatory element-binding protein 2 (SREBP2), a key transcription factor that regulates cholesterol biosynthesis and uptake, is crucial in maintaining testicular cholesterol homeostasis. This study examined SREBP2 dynamics and cholesterol levels in rabbit spermatogenesis under HFDs. Our findings indicate that SREBP2 expression fluctuates throughout the seminiferous epithelium cycle, with HFDs inducing stage-specific disruptions in cholesterol balance, ultimately leading to the emergence of sperm with increased membrane cholesterol, reduced count, impaired motility, abnormal morphology, and decreased functionality. Interestingly, SREBP2 expression patterns in the control group revealed its critical role in normal spermatogenesis. Supplementation with extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) reversed these effects, normalizing SREBP2 expression, and cholesterol content and improving sperm quality. These findings highlight the importance of stage-specific analysis in understanding the impact of dietary fat on male fertility and suggest EVOO as a potential nutritional intervention to safeguard reproductive health.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. General Parameters

2.1.1. Body Parameters

2.1.2. Serum Analyses

2.1.3. Semen Analysis

2.2. Characterization of the Seminiferous Epithelium

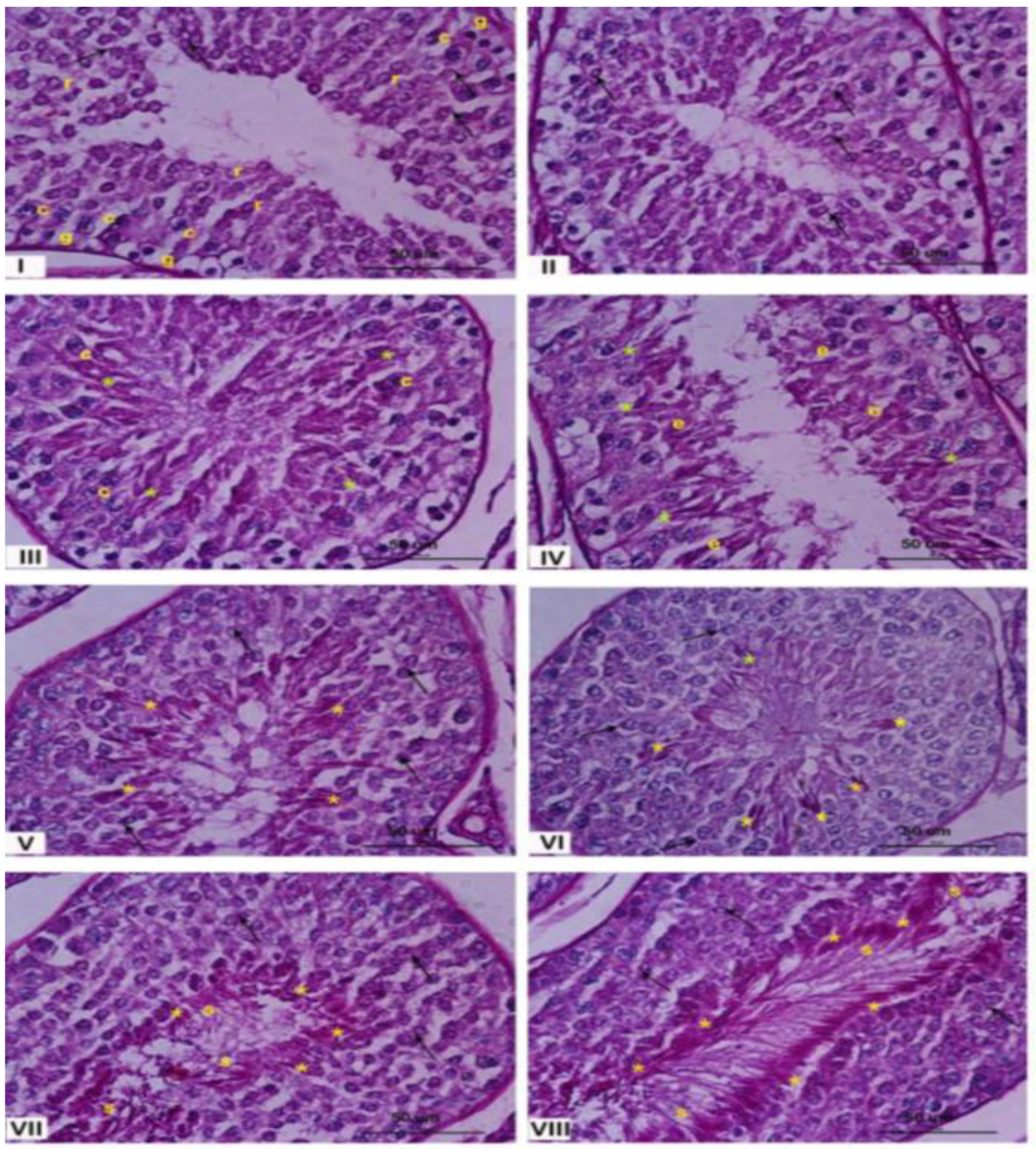

2.2.1. Testis Morphology—Stage Classification of Seminiferous Epithelium

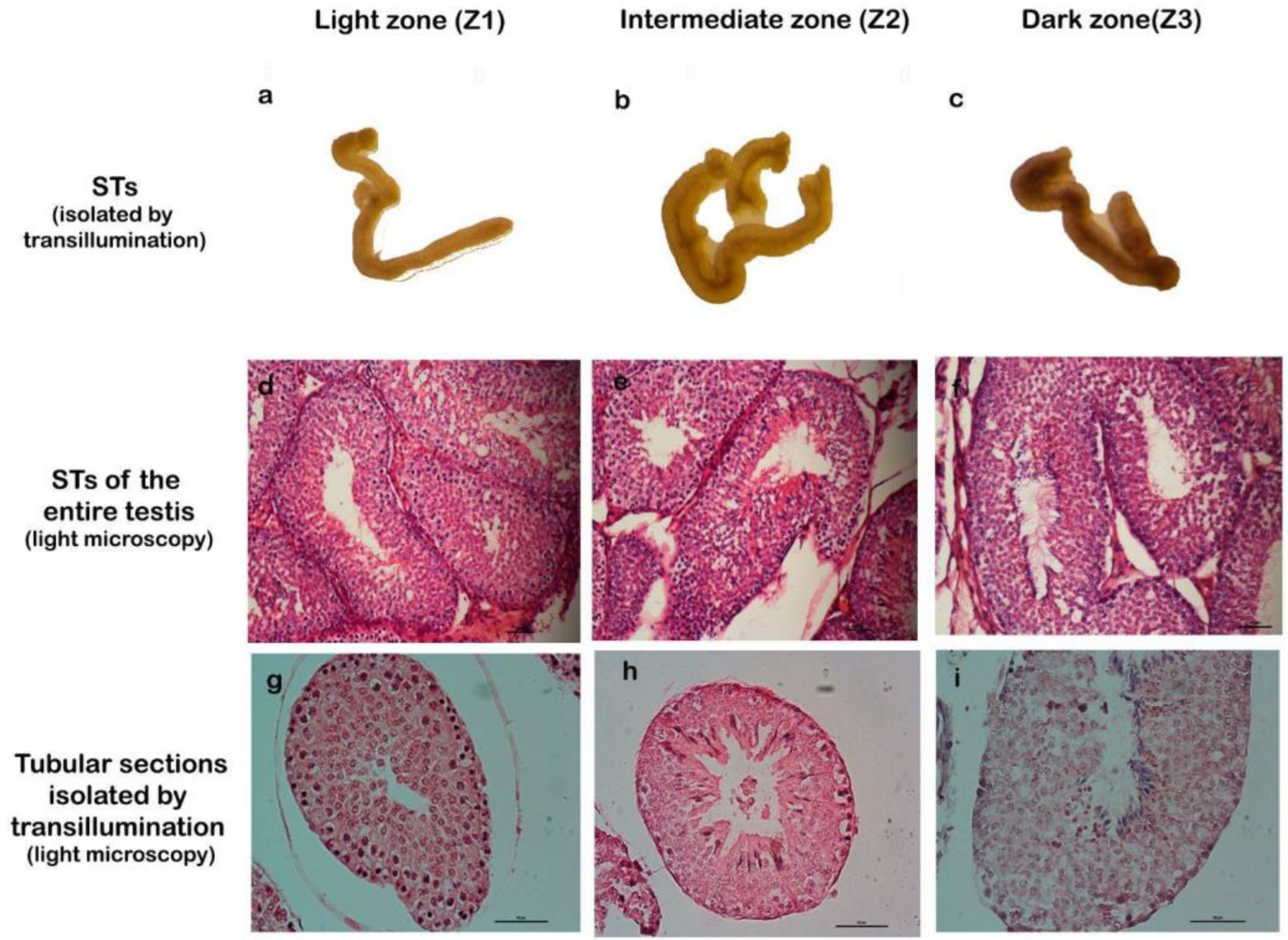

2.2.2. Isolated Seminiferous Tubule Characterization and Correlation with Stages

2.3. Cholesterol Analyses

2.3.1. Cholesterol Accumulation in the Seminiferous Epithelium

2.3.2. Cholesterol Distribution Across Spermatogenic Stages

2.3.3. Cholesterol Distribution by Diets and Zones.

2.4. SREBP2 in Seminiferous Tubules

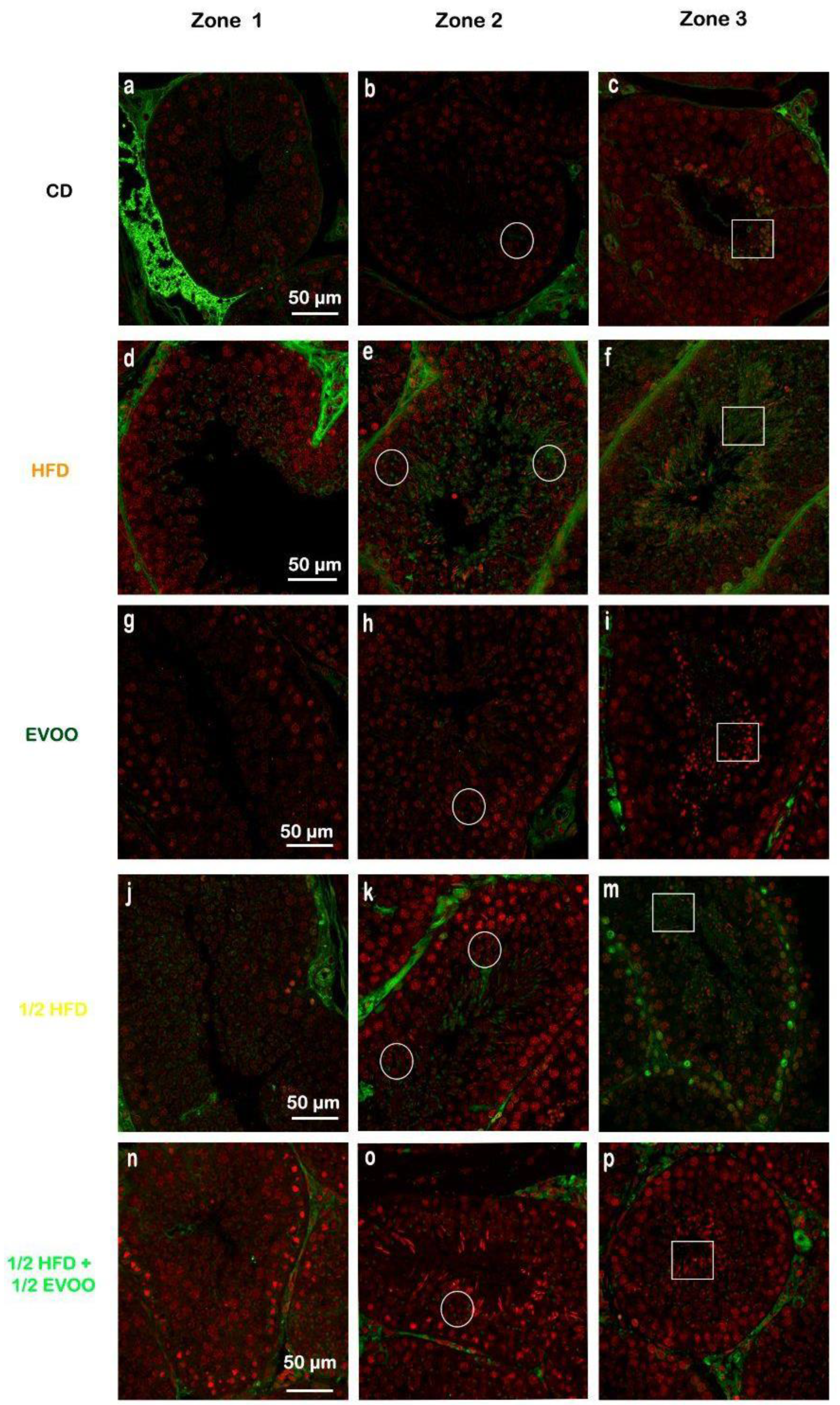

2.4.1. SREBP2 Localization

2.4.2. Distribution of SREBP2 Across Spermatogenic Stages

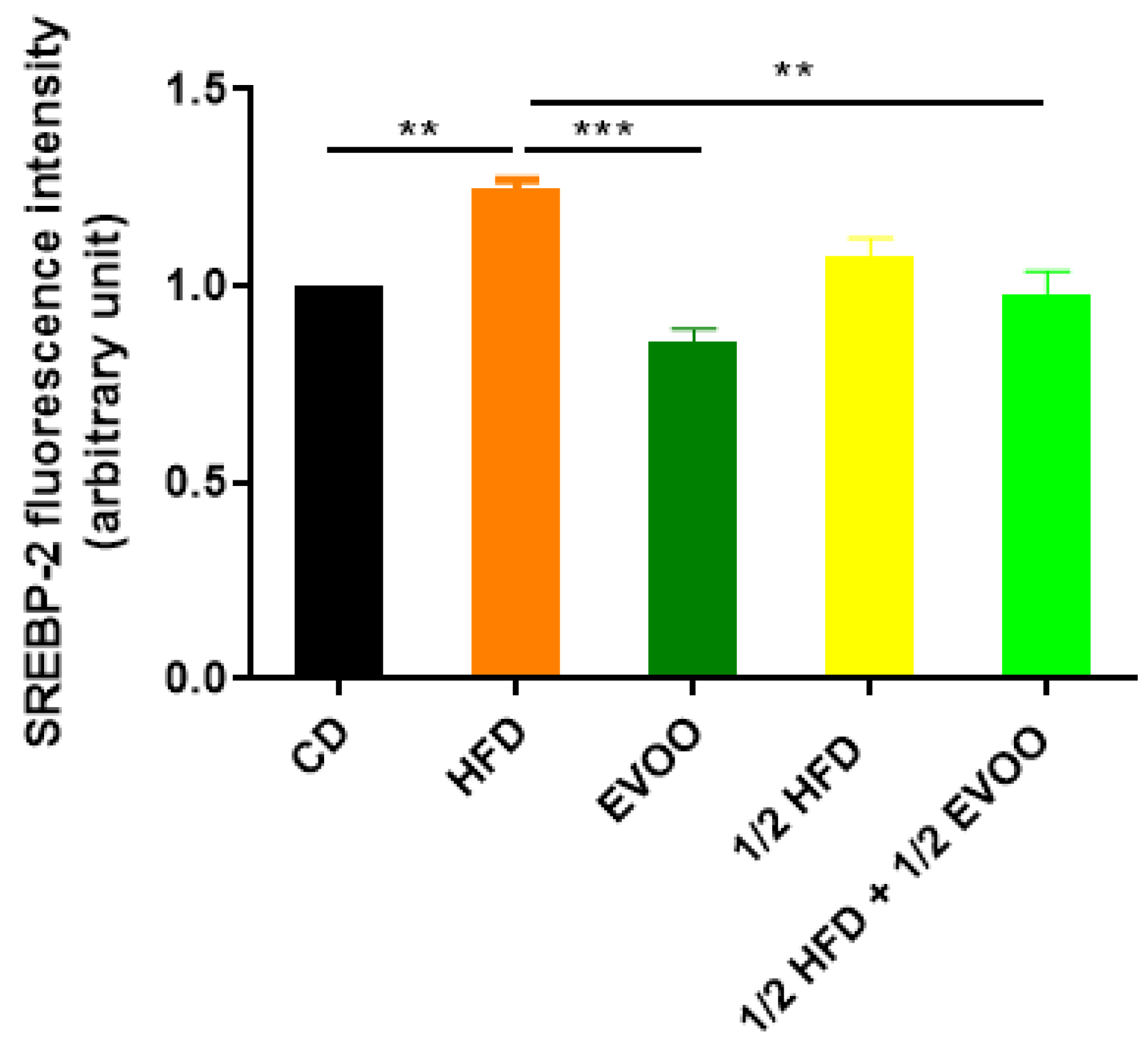

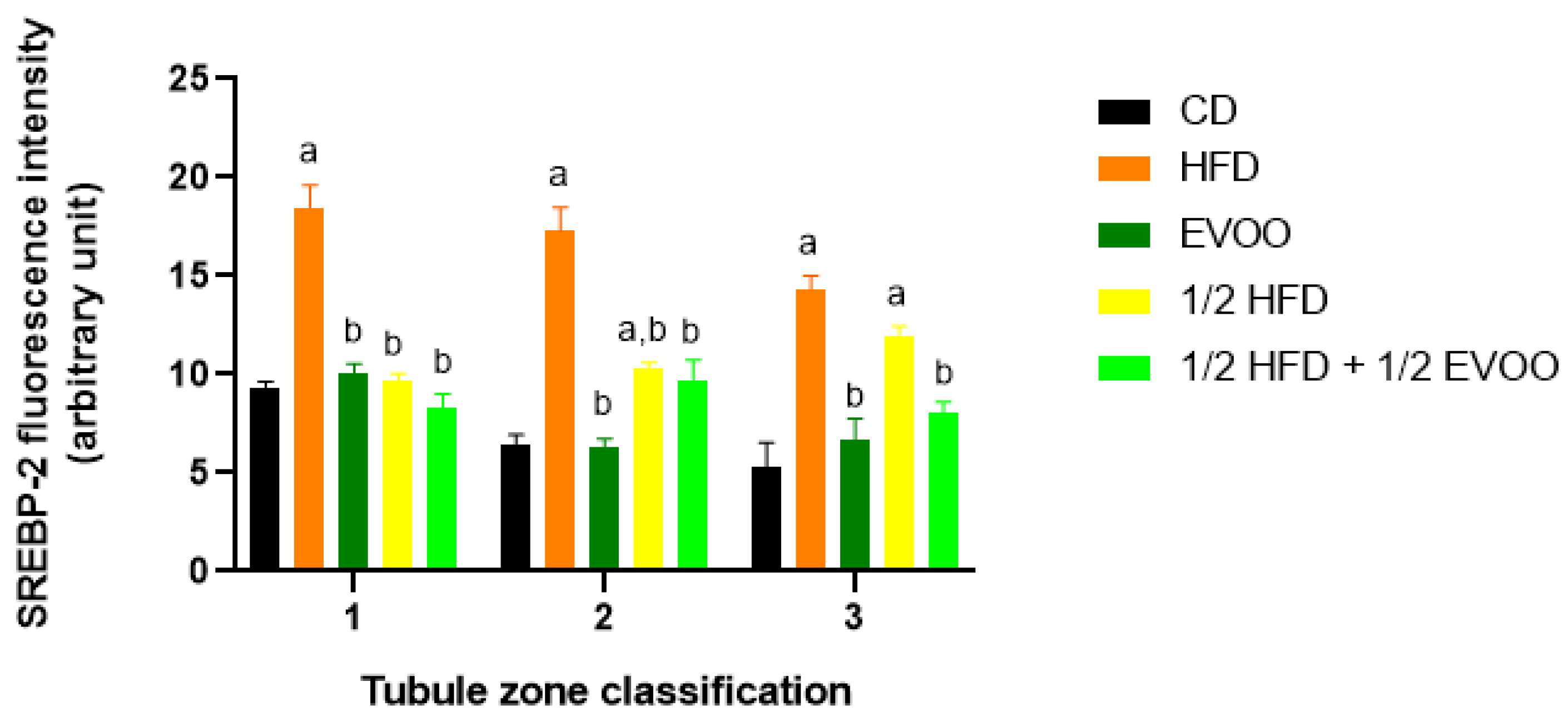

2.4.3. Distribution of SREBP2 Among Zones/Stages and Diet

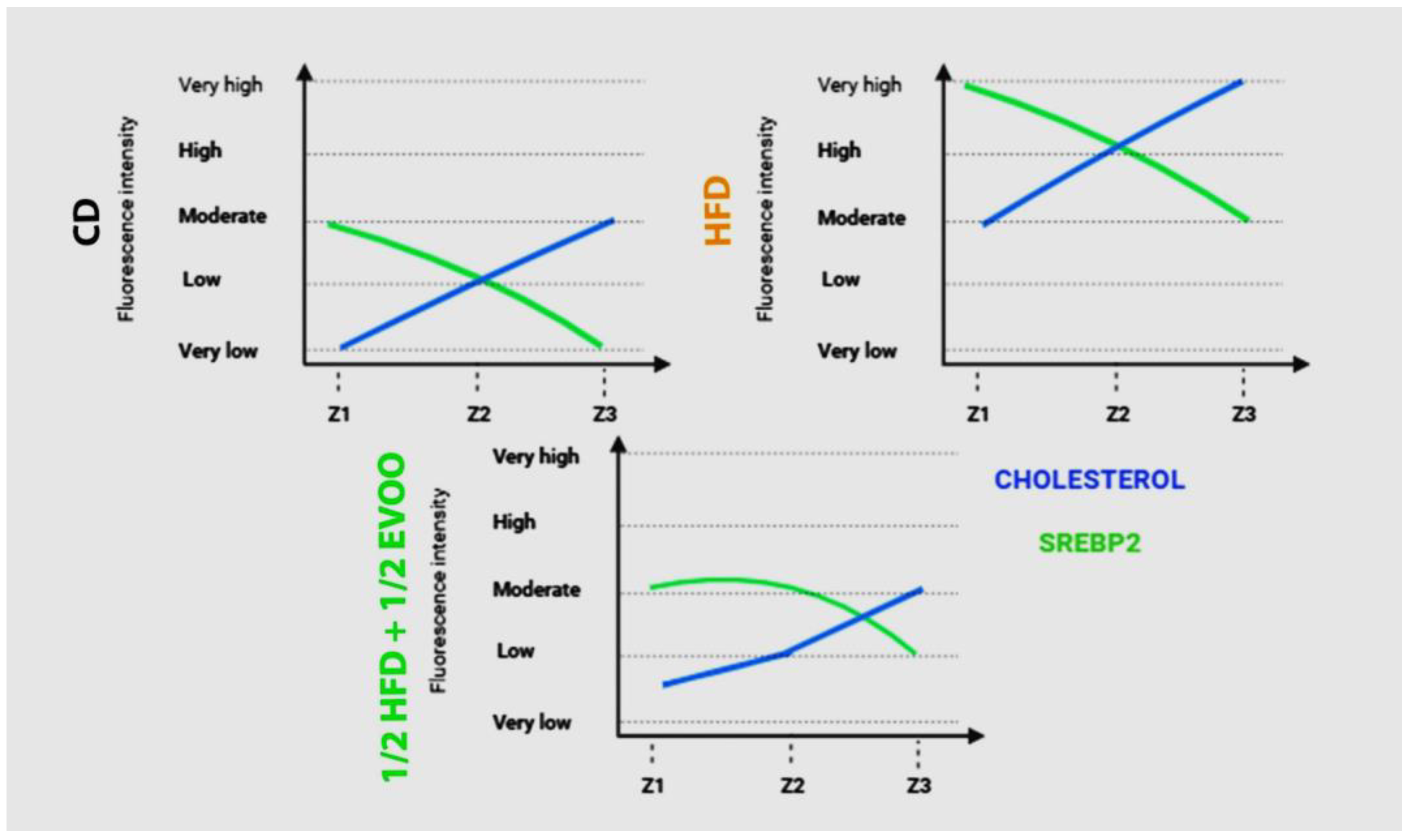

2.5. Comparison Between SREBP2 and Cholesterol Distribution.in Seminiferous Tubules

2.5.1. Relationship Between SREBP2 and Cholesterol Distribution in the Seminiferous Epithelium.

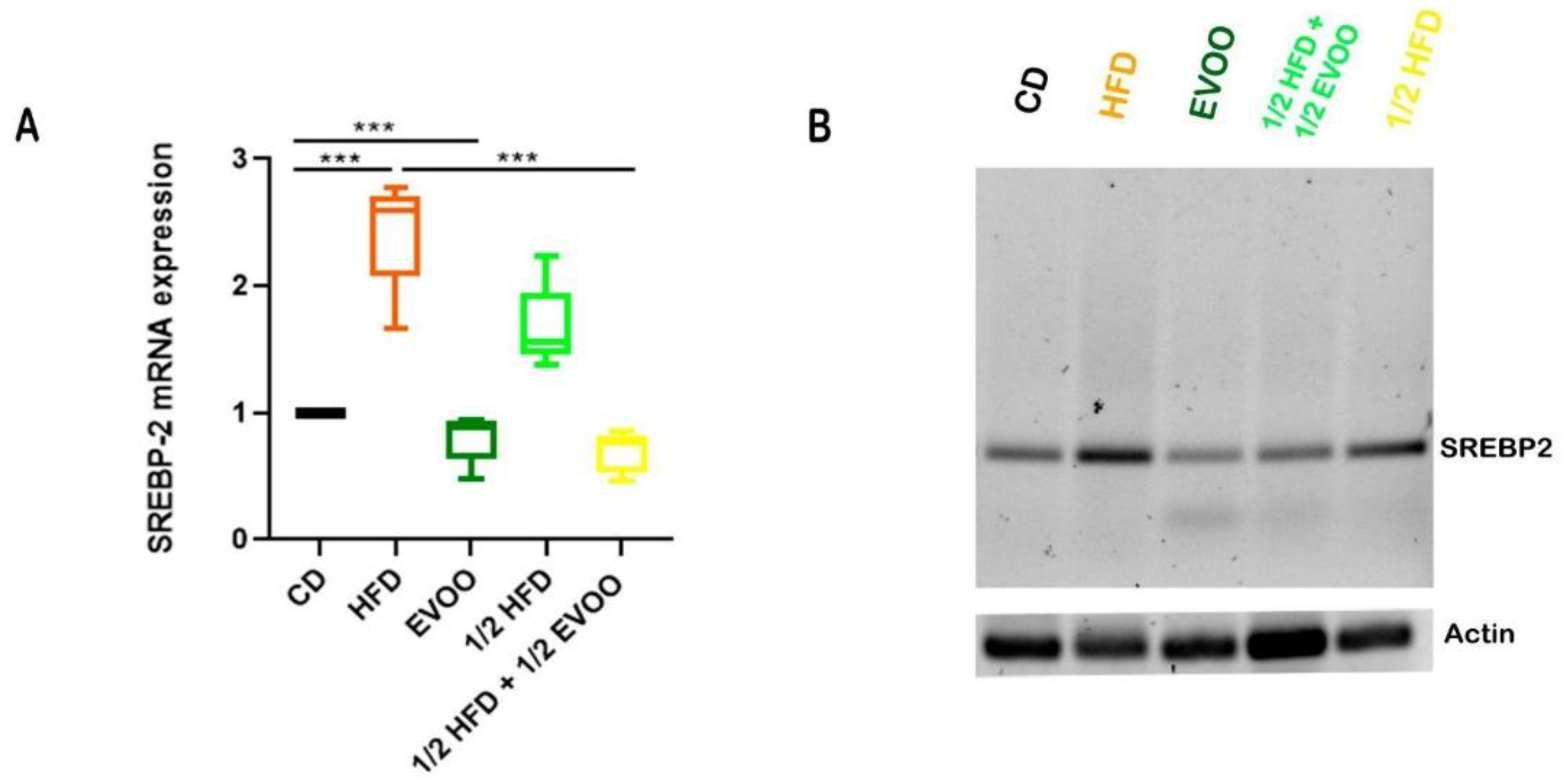

2.5. Molecular Studies.

2.5.1. Expression of SREBP2 mRNA in the Seminiferous Epithelium

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

4.2. EVOO Analysis

| Chemical | % | Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Humidity and volatile materials | 0.06 | IRAM 500 |

| Fiber | < 0.01 | AOAC |

| Total Carbon hydrates | < 0.01 | Total sugars method |

| Proteins | < 0.01 | Kjeldahl methods, N x 5,8 |

| Calories | 899 | Kcal /100 g |

| 3767 | Kjoul /100 g | |

| Total lipids | 99.94 | Twisselmann method |

| Class | Percentage of methyl esters |

|---|---|

| Meristic | 0.01 |

| Palmitic | 14.25±0.24 |

| Palmitoleic | 1.48±0.01 |

| Heptadecanoic | 0.07±0.01 |

| Stearic | 70.36±0.28 |

| Oleic | 9.92±0.70 |

| Linoleic | 0.72±0.26 |

| Arachidonic | 0.37±0.10 |

| Behenic | 0.11±0.01 |

| Acidity: g % oleic acid | 0,91±0.1 |

| Peroxide index: meq O2/kg | 9.0±0.5 |

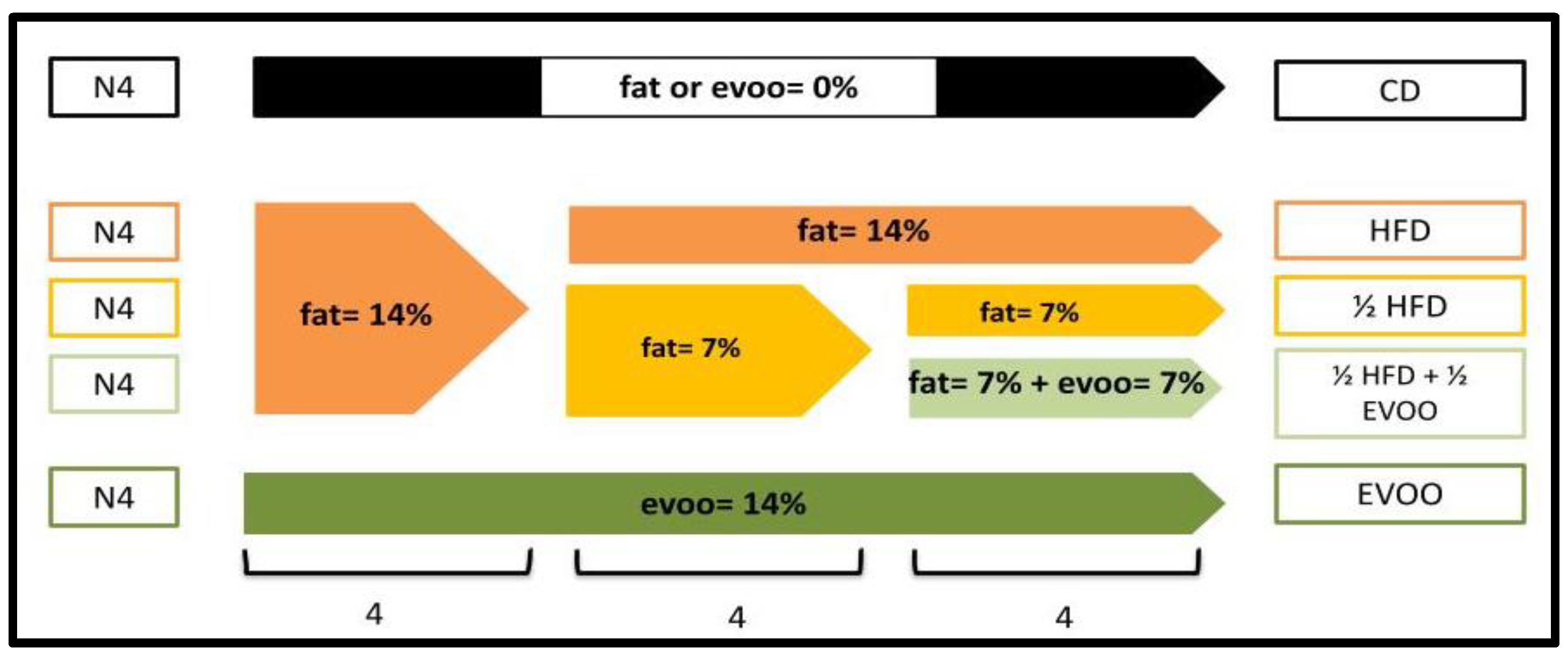

4.3. Animal Model and Experimental Groups

| Diet | % (v/w) Fat supplementation | % (v/w) Olive oil supplementation | Group Name | ||

| 14 | 7 | 14 | 7 | ||

| Normal | - | - | - | - | CD (Control Diet) |

| Experimental | + | - | - | - | HFD (High-Fat Diet) |

| - | + | - | - | ½ HFD (Media High-Fat Diet) | |

| - | - | + | - | EVOO (Extra Virgin Olive Oil Diet) | |

| - | + | - | + | ½ HFD + ½ EVOO (Media HFD and media Extra Virgin Olive Oil) - Protective diet. | |

4.4. General Parameters

4.5. Structural Studies

4.6. Molecular Studies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript | . |

| Control diet: | CD |

| Control group: | CG |

| EVOO groups: | animal group fed with EVOO |

| Experimental diet: | ED |

| Extra Virgin olive oil: | EVOO |

| Glutamate piruvate transaminase: | GPT |

| Glutamic oxalacetic transaminase: | GOT |

| Hematoxylin-Eosin: | H-E |

| High-fat diet/s: | HFD/s |

| Kilo Dalton: | kDa |

| cholesterol not coupled to high-density protein: | non-HDL cholesterol |

| Periodic Acid Schiff: | PAS |

| Propidium iodide: | PI |

| Sterol cleavage-activating protein: | SCAP |

| Sterol response element binding protein 1a, 1c, and 2: | SREBP1a, SREBP1c, and SREBP2, |

| The half concentration of fat compared with HFD: | ½ HFD |

| The half concentration of olive oil compared with EVOO: | ½ EVOO |

| Zone 1, light zone by transillumination method, corresponding to stages I and II: | Z1 |

| Zone 2, intermediate zone by transillumination method, corresponding to stages III, IV, V, and VI: | Z2 |

| Zone 3, dark zone by transillumination method, corresponding to stages VII and VIII.: | Z3 |

References

- F. Saez and J. R. Drevet, “Dietary Cholesterol and Lipid Overload: Impact on Male Fertility,” Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev., vol. 2019, p. 4521786, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Funes et al., “A chronic high-fat diet causes sperm head alterations in C57BL/6J mice,” Heliyon, vol. 5, no. 11, Art. no. 11, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. L. Nassan, J. E. Chavarro, and C. Tanrikut, “Diet and men’s fertility: does diet affect sperm quality?,” Fertil. Steril., vol. 110, no. 4, pp. 570–577, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Ghosh and S. Mukherjee, “Testicular germ cell apoptosis and sperm defects in mice upon long-term high fat diet feeding,” J. Cell. Physiol., vol. 233, no. 10, pp. 6896–6909, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Luo et al., “High fat diet impairs spermatogenesis by regulating glucose and lipid metabolism in Sertoli cells,” Life Sci., vol. 257, p. 118028, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Jarvis et al., “High fat diet causes distinct aberrations in the testicular proteome,” Int. J. Obes. 2005, vol. 44, no. 9, Art. no. 9, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Xiu-Yan Yang, Yu-jie Gu, and Guang-Jian Jiang, “Proteomics Analysis of Testis of Rats Fed a High-Fat Diet,” Cell. Physiol. Biochem., vol. 47, pp. 378–389, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Almujaydil, “The Role of Dietary Nutrients in Male Infertility: A Review,” Life Basel Switz., vol. 13, no. 2, p. 519, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. E. S. Lancellotti et al., “Hypercholesterolemia Impaired Sperm Functionality in Rabbits,” PLOS ONE, vol. 5, no. 10, Art. no. 10, Oct. 2010. [CrossRef]

- L. Simón et al., “Manchette-acrosome disorders during spermiogenesis and low efficiency of seminiferous tubules in hypercholesterolemic rabbit model,” PLoS ONE, vol. 12, no. 2, Art. no. 2, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. K. Funes et al., “Impact of high fat diet on the sterol regulatory element-binding protein 2 cholesterol pathway in the testicle,” Mol. Hum. Reprod., vol. 27, no. 5, Art. no. 5, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Sigrist-Flores et al., “Chronic intake of moderate fat-enriched diet induces fatty liver and low-grade inflammation without obesity in rabbits,” Chem. Biol. Interact., vol. 300, pp. 56–62, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Fan et al., “Rabbit models for the study of human atherosclerosis: from pathophysiological mechanisms to translational medicine,” Pharmacol. Ther., vol. 0, pp. 104–119, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. D. Horton, I. Shimomura, M. S. Brown, R. E. Hammer, J. L. Goldstein, and H. Shimano, “Activation of cholesterol synthesis in preference to fatty acid synthesis in liver and adipose tissue of transgenic mice overproducing sterol regulatory element-binding protein-2.,” J. Clin. Invest., vol. 101, no. 11, pp. 2331–2339, Jun. 1998.

- J. Pai, O. Guryev, M. S. Brown, and J. L. Goldstein, “Differential Stimulation of Cholesterol and Unsaturated Fatty Acid Biosynthesis in Cells Expressing Individual Nuclear Sterol Regulatory Element-binding Proteins *,” J. Biol. Chem., vol. 273, no. 40, pp. 26138–26148, Oct. 1998. [CrossRef]

- S. P. Persengiev, P. J. Raval, S. Rabinovitch, C. F. Millette, and D. L. Kilpatrick, “Transcription factor Sp1 is expressed by three different developmentally regulated messenger ribonucleic acids in mouse spermatogenic cells,” Endocrinology, vol. 137, no. 2, pp. 638–646, Feb. 1996. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, F. Liu, C. F. Millette, and D. L. Kilpatrick, “Expression of a Novel, Sterol-Insensitive Form of Sterol Regulatory Element Binding Protein 2 (SREBP2) in Male Germ Cells Suggests Important Cell- and Stage-Specific Functions for SREBP Targets during Spermatogenesis,” Mol. Cell. Biol., vol. 22, no. 24, Art. no. 24, Dec. 2002. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, J. T. San Agustin, G. B. Witman, and D. L. Kilpatrick, “Novel role for a sterol response element binding protein in directing spermatogenic cell-specific gene expression,” Mol. Cell. Biol., vol. 24, no. 24, pp. 10681–10688, Dec. 2004. [CrossRef]

- K. Fon Tacer, S. Kalanj-Bognar, M. R. Waterman, and D. Rozman, “Lanosterol metabolism and sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP) expression in male germ cell maturation,” J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol., vol. 85, no. 2–5, pp. 429–438, Jun. 2003. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, B. L. Sartini, C. F. Millette, and D. L. Kilpatrick, “A developmental switch in transcription factor isoforms during spermatogenesis controlled by alternative messenger RNA 3′-end formation,” Biol. Reprod., vol. 75, no. 3, pp. 318–323, Sep. 2006. [CrossRef]

- A. K. Funes et al., “Extra-virgin olive oil ameliorates high-fat diet-induced seminal and testicular disorders by modulating the cholesterol pathway,” Andrology, vol. 11, no. 6, Art. no. 6, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. E. Saez Lancellotti et al., “Semen quality and sperm function loss by hypercholesterolemic diet was recovered by addition of olive oil to diet in rabbit,” PloS One, vol. 8, no. 1, Art. no. 1, 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. K. Funes et al., “Cholesterol dynamics in rabbit liver: High-fat diet, olive oil, and synergistic dietary effects,” Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., vol. 733, p. 150675, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Simón et al., “Manchette-acrosome disorders and testicular efficiency decline observed in hypercholesterolemic rabbits are recovered with olive oil enriched diet,” PloS One, vol. 13, no. 8, Art. no. 8, 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. E. Swierstra and R. H. Foote, “Cytology and kinetics of spermatogenesis in the rabbit,” J. Reprod. Fertil., vol. 5, pp. 309–322, Jun. 1963. [CrossRef]

- Juho-Antti Mäkelä and et al., “Transillumination-Assisted Dissection of Specific Stages of the Mouse Seminiferous Epithelial Cycle for Downstream Immunostaining Analyses - PubMed,” J Vis Exp., no. 164, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. T. Gwynne and J. F. Strauss, “The role of lipoproteins in steroidogenesis and cholesterol metabolism in steroidogenic glands,” Endocr. Rev., vol. 3, no. 3, Art. no. 3. 1982. [CrossRef]

- D. H. Morgan, O. Ghribi, L. Hui, J. D. Geiger, and X. Chen, “Cholesterol-enriched diet disrupts the blood-testis barrier in rabbits,” Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab., vol. 307, no. 12, pp. E1125-1130, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- “HC diet inhibited testosterone synthesis by activating endoplasmic reticulum stress in testicular Leydig cells - PMC.” Accessed: Sep. 03, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6484377/.

- P. Campos-Silva, A. Furriel, W. S. Costa, F. J. B. Sampaio, and B. M. Gregorio, “Metabolic and testicular effects of the long-term administration of different high-fat diets in adult rats,” Int. Braz J Urol Off. J. Braz. Soc. Urol., vol. 41, no. 3, pp. 569–575, 2015. [CrossRef]

- B. B. Madison, “Srebp2: A master regulator of sterol and fatty acid synthesis,” J. Lipid Res., vol. 57, no. 3, Art. no. 3, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. Alarcon, J. Roco, M. Medina, A. Medina, M. Peral, and S. Jerez, “High fat diet-induced metabolically obese and normal weight rabbit model shows early vascular dysfunction: mechanisms involved,” Int. J. Obes. 2005, vol. 42, no. 9, Art. no. 9, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- W. Pluta, W. Dudzińska, and A. Lubkowska, “Metabolic Obesity in People with Normal Body Weight (MONW)-Review of Diagnostic Criteria,” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health, vol. 19, no. 2, p. 624, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Rezaei, M. Akhlaghi, M. R. Sasani, and R. Barati Boldaji, “Olive oil lessened fatty liver severity independent of cardiometabolic correction in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized clinical trial,” Nutr. Burbank Los Angel. Cty. Calif, vol. 57, pp. 154–161, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Hwang et al., “Dietary saturated and monounsaturated fats protect against acute acetaminophen hepatotoxicity by altering fatty acid composition of liver microsomal membrane in rats,” Lipids Health Dis., vol. 10, p. 184, Oct. 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Hess and L. Renato de Franca, “Spermatogenesis and cycle of the seminiferous epithelium,” Adv. Exp. Med. Biol., vol. 636, pp. 1–15, 2008. [CrossRef]

- C. C. Linder, L. L. Heckert, K. P. Roberts, K. H. Kim, and M. D. Griswold, “Expression of receptors during the cycle of the seminiferous epithelium,” Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci., vol. 637, pp. 313–321, 1991. [CrossRef]

- J.-F. Shi, Y.-K. Li, K. Ren, Y.-J. Xie, W.-D. Yin, and Z.-C. Mo, “Characterization of cholesterol metabolism in Sertoli cells and spermatogenesis (Review),” Mol. Med. Rep., vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 705–713, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Shimizu-Albergine, B. Van Yserloo, M. G. Golkowski, S.-E. Ong, J. A. Beavo, and K. E. Bornfeldt, “SCAP/SREBP pathway is required for the full steroidogenic response to cyclic AMP,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., vol. 113, no. 38, pp. E5685-5693, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- “Endogenous sterol intermediates of the mevalonate pathway regulate HMGCR degradation and SREBP-2 processing - PubMed.” Accessed: Sep. 03, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31455613/.

- “Cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate(cAMP)/cAMP-responsive element modulator (CREM)-dependent regulation of cholesterogenic lanosterol 14alpha-demethylase (CYP51) in spermatids - PubMed.” Accessed: Sep. 03, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10551787/.

- H. Wang et al., “Evaluation on the phagocytosis of apoptotic spermatogenic cells by Sertoli cells in vitro through detecting lipid droplet formation by Oil Red O staining,” Reproduction, vol. 132, no. 3, Art. no. 3, Sep. 2006. [CrossRef]

- T. Ozkan-Nikitaras, D. J. Grzesik, L. E. L. Romano, J. P. Chapple, P. J. King, and C. C. Shoulders, “N-SREBP2 Provides a Mechanism for Dynamic Control of Cellular Cholesterol Homeostasis,” Cells, vol. 13, no. 15, Art. no. 15, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xiong, C. Yu, and Q. Zhang, “Ubiquitin-Proteasome System-Regulated Protein Degradation in Spermatogenesis,” Cells, vol. 11, no. 6, p. 1058, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Yahagi et al., “Absence of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 (SREBP-1) ameliorates fatty livers but not obesity or insulin resistance in Lep(ob)/Lep(ob) mice,” J. Biol. Chem., vol. 277, no. 22, pp. 19353–19357, May 2002. [CrossRef]

- A. Takahashi et al., “Transgenic mice overexpressing nuclear SREBP-1c in pancreatic beta-cells,” Diabetes, vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 492–499, Feb. 2005. [CrossRef]

- T.-I. Jeon and T. F. Osborne, “SREBPs: metabolic integrators in physiology and metabolism,” Trends Endocrinol. Metab. TEM, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 65–72, Feb. 2012. [CrossRef]

- C. Lammi et al., “Extra Virgin Olive Oil Phenol Extracts Exert Hypocholesterolemic Effects through the Modulation of the LDLR Pathway: In Vitro and Cellular Mechanism of Action Elucidation,” Nutrients, vol. 12, no. 6, p. 1723, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Rifai, G. R. Warnick, J. R. McNamara, J. D. Belcher, G. F. Grinstead, and I. D. Frantz, “Measurement of low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol in serum: a status report,” Clin. Chem., vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 150–160, Jan. 1992.

- M. H. Burgos and G. Di Paola, “Eosin test for the evaluation of sperm vitality,” Fertil. Steril., vol. 2, no. 6, Art. no. 6, 1951. [CrossRef]

- “Filipin, an Antifungal Antibiotic: Isolation and Properties | Journal of the American Chemical Society.” Accessed: Oct. 05, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/ja01623a032.

- V. Betina, “Paper chromatography of antibiotics,” Chromatogr. Rev., vol. 7, pp. 119–178, Jan. 1965. [CrossRef]

- F. Schroeder, J. F. Holland, and L. L. Bieber, “FLUOROMETRIC EVIDENCE FOR THE BINDING OF CHOLESTEROL TO THE FILIPIN COMPLEX,” J. Antibiot. (Tokyo), vol. 24, no. 12, Art. no. 12, 1971. [CrossRef]

- A. W. Norman, R. A. Demel, B. de Kruyff, and L. L. M. van Deenen, “Studies on the Biological Properties of Polyene Antibiotics: EVIDENCE FOR THE DIRECT INTERACTION OF FILIPIN WITH CHOLESTEROL,” J. Biol. Chem., vol. 247, no. 6, Art. no. 6, Mar. 1972. [CrossRef]

- K. Harzer and B. Kustermann-Kuhn, “Quantified increases of cholesterol, total lipid and globotriaosylceramide in filipin-positive Niemann-Pick type C fibroblasts,” Clin. Chim. Acta, vol. 305, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Mar. 2001. [CrossRef]

- K. Yanagisawa, “Cholesterol and Abeta aggregation,” Pharmacopsychiatry, vol. 36 Suppl 2, pp. S127-129, Sep. 2003. [CrossRef]

- E. Trushina et al., “Mutant Huntingtin Impairs Axonal Trafficking in Mammalian Neurons In Vivo and In Vitro,” Mol. Cell. Biol., vol. 24, no. 18, Art. no. 18, Sep. 2004. [CrossRef]

| Primer | Forward | Reverse | T° | #C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actin | ACCAACTGGGACGACATGGAGAA | GTCAGGATCTTCATGAGGTAGTC | 54 | 30 |

| SREBP2 | CAGATTCCCTTGTTCTGACCACACTG | GCCAGCTTCAGCACCATGTTC | 62 | 28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).