1. Introduction

Sepsis is defined as a severe and potentially life-threatening syndrome caused by the body’s overwhelming and dysregulated response to an infection, leading to widespread inflammation, tissue damage, and organ dysfunction [

1]. Prompt recognition and treatment are critical to improving outcomes, as sepsis can progress rapidly to septic shock and multiple organ failure. Since there is not a specific treatment for sepsis yet, effective management involves a combination of early diagnosis, timely administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics, fluid resuscitation to stabilize blood pressure, and addressing the underlying infection source [

2,

3]. Advanced therapies, such as vasopressors for circulatory support and organ-specific interventions like mechanical ventilation or dialysis, may be required in severe cases [

4]. Comprehensive care guided by standardized protocols, such as the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines, plays a pivotal role in improving survival rates and minimizing long-term complications [

5]. Identifying risk factors such as weakened immune systems, chronic illnesses, advanced age, or the presence of invasive devices is also vital in preventing sepsis and ensuring early detection in high-risk populations [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Obesity has been identified as a significant risk factor for many diseases including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, stroke, dyslipidemia, osteoarthritis, and some cancers [

10,

11]. However, when it comes to adult sepsis, the “obesity paradox” has been suggested from numerous studies, where higher body mass index (BMI) has been associated with improved sepsis survival [

7,

8,

9,

10,

12], although this paradox is not linear, as morbid obesity can worsen the outcome [

9].

The relationship between obesity and outcomes in pediatric sepsis is complex and less well-defined compared to adult populations [

13]. Several factors unique to pediatric sepsis contribute to these inconclusive results, including physiological differences between children and adults, variations in immune responses, comorbidities, developmental physiology, and inconsistencies in study designs [

14]. Notably, pediatric studies on obesity and sepsis tend to be smaller in scale and often lack standardization in their definitions of both obesity and sepsis [

15,

16,

17]. A critical distinction between adult and pediatric sepsis lies in their respective definitions, which have evolved differently over time. From 2005 until 2024, pediatric sepsis was defined according to the 2005 International Pediatric Sepsis Consensus Conference. This definition, referred to as Sepsis-2, was based on systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria and was shared with adult sepsis at the time [

18]. However, the definition for adult sepsis was updated in 2016 to Sepsis-3, which introduced significant changes. Under Sepsis-3, sepsis was defined as a suspected or confirmed infection with life-threatening organ dysfunction, assessed using the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, with a threshold of at least 2 points [

19]. For nearly eight years, these differing definitions created a gap in the criteria for diagnosing sepsis between adults and children. Only recently, in March 2024, a new International Consensus Criteria for Pediatric Sepsis and Septic Shock was introduced, aligning pediatric definitions more closely with Sepsis-3 [

20]. This updated definition is based on the Phoenix Sepsis Score, which identifies sepsis in children as a suspected or confirmed infection with life-threatening dysfunction by evaluating four systems—respiratory, cardiovascular, coagulation, or neurological. Septic shock, under this new definition, is characterized as sepsis accompanied by cardiovascular dysfunction indicated by at least 1 or more points in the cardiovascular organ system. Importantly, like Sepsis-3, the Phoenix definition requires acute organ dysfunction for the diagnosis of sepsis, making all pediatric sepsis cases equivalent to “severe sepsis” under previous definitions [

19,

20].

Given the introduction of the Phoenix criteria, it is now possible to re-examine the association between obesity and sepsis in pediatric patients with greater precision. The updated definition, with its emphasis on organ dysfunction, provides a more consistent framework for evaluating outcomes in children. In the current study, we aimed to investigate the relationship between obesity and pediatric sepsis using the new Phoenix criteria. Additionally, we compared these findings to data derived from the previously used Sepsis-2 definition. By doing so, we sought to clarify the role of obesity as a potential risk factor in pediatric sepsis and its outcomes.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study was conducted as a retrospective, single-center cohort analysis and received approval from the Institutional Review Board at Boston Children’s Hospital (IRB approval number IRB-P00041981). The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. The cohort included 806 pediatric patients who were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) at Boston Children’s Hospital between January 2014 and December 2019. These patients were identified as having sepsis based on diagnostic codes from the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9 and ICD-10) and defined according to the Sepsis-2 criteria.

2.2. Study Participants and Data Collection

Among the 806 patients enrolled in this study, 640 were younger than 18 years old. For these pediatric patients, we collected comprehensive data from the electronic medical record (EMR), including demographic information, vital signs (such as oxygen saturation and mean arterial blood pressure) at the time of ICU admission, and the presence or absence of respiratory support. Additionally, we recorded the length of ICU stay, types of microbes detected (if any), laboratory data (including complete blood count, chemistry panels, liver and kidney function tests, and arterial blood gas analysis), and medications administered during their ICU stay. To evaluate organ dysfunction, we employed the organ dysfunction scoring system used to develop for the Phoenix criteria [

20]. Initially, eight organ domains were assessed using various established organ injury scoring systems, including the International Pediatric Sepsis Consensus Conference (IPSCC), Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction version 2 (PELOD-2), Pediatric Organ Dysfunction Information Update Mandate (PODIUM), Proulx, and Pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (pSOFA). These domains included respiratory, cardiovascular, coagulation, neurological, renal, hepatic, immunologic, and endocrine systems. Among these, the immunologic and endocrine systems were assessed exclusively in the PODIUM system. Most organ dysfunction scoring systems, however, consistently evaluated six core domains: respiratory, cardiovascular, coagulation, neurological, renal, and hepatic. Consequently, we focused our analysis on these six domains (

Table 1). This was the case for adult sepsis in sepsis-3 definition. Neurological status was evaluated based on available documentation. At our institution, the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is not routinely reported unless a patient has an evident neurological issue. Therefore, patients without documented neurological abnormalities were assumed to be neurologically intact. For patients on sedation, neurological status was assessed based on routine pupil reactivity checks. The Phoenix criteria define sepsis as a Phoenix Sepsis Score of ≥2 points in the presence of suspected infection, with the criteria specifically evaluating the respiratory, cardiovascular, coagulation, and neurological domains [

20]. Of the 640 pediatric patients diagnosed with sepsis under the Sepsis-2 definition, 631 also met the Phoenix criteria for sepsis. Pediatric obesity in this cohort was defined based on Body Mass Index (BMI), which estimates weight relative to height. BMI classifications followed the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) growth charts, with underweight defined as a BMI <5th percentile, normal weight as a BMI between the 5th and 85th percentiles, overweight as a BMI between the 85th and 95th percentiles, and obesity as a BMI ≥95th percentile [

21].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

We presented the number and percentage for categorical variables, mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables with normal distribution, or median and interquartile range (IQR) for variables with skewed distribution. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess normality. P< 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed using STAT13 (College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Obese Children Had Worse Survival and More Organ Dysfunction Under Sepsis-2 Definition

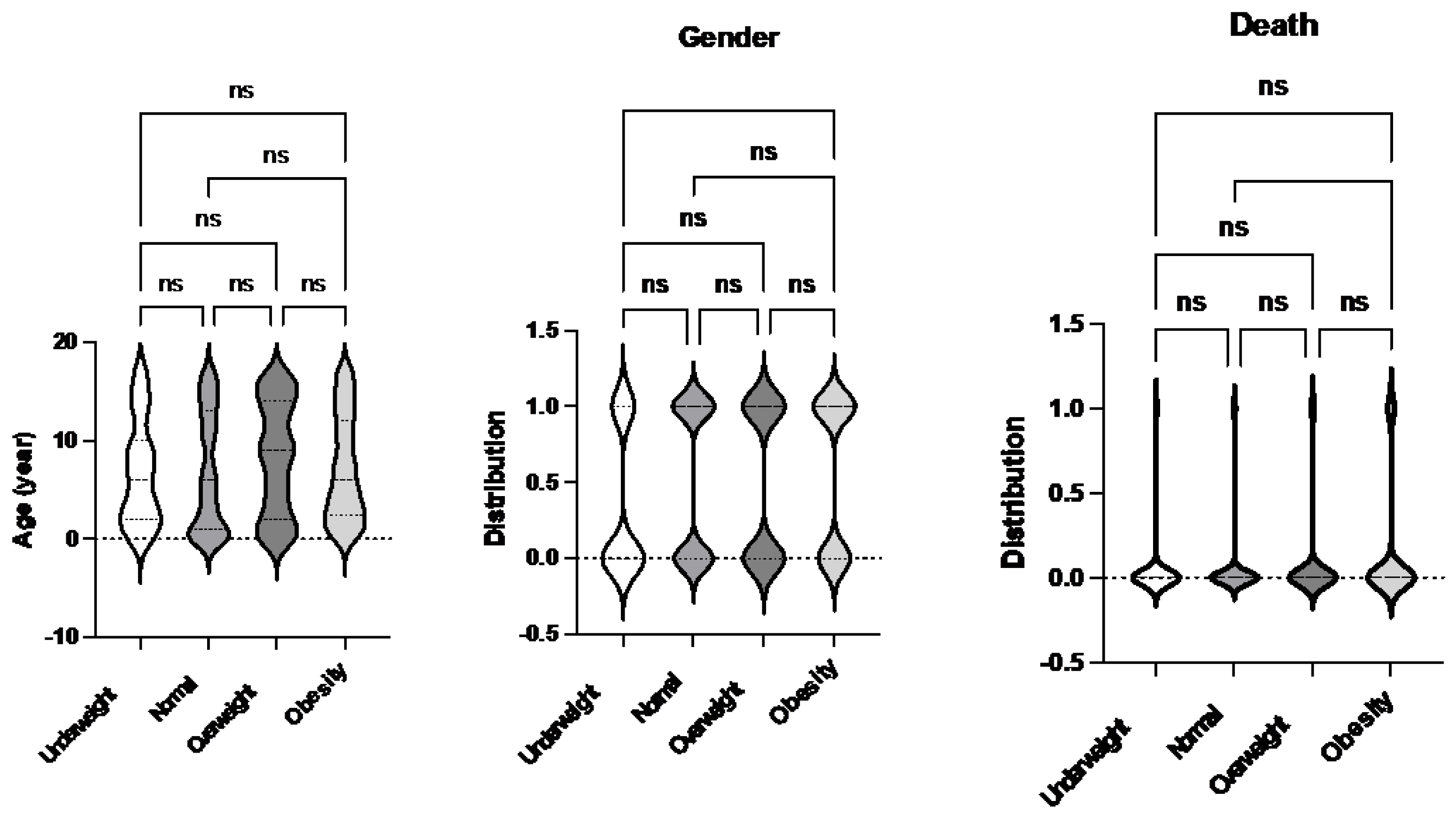

The data on pediatric sepsis, defined using the previous Sepsis-2 definition, is summarized in

Table 2. The study analyzed patient characteristics and outcomes based on body habitus, categorizing patients into the four groups: underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese. No significant differences in age were observed among these groups. However, the underweight group had a higher proportion of female patients compared to other groups. Notably, the obese group exhibited a higher mortality rate compared to the normal weight group (

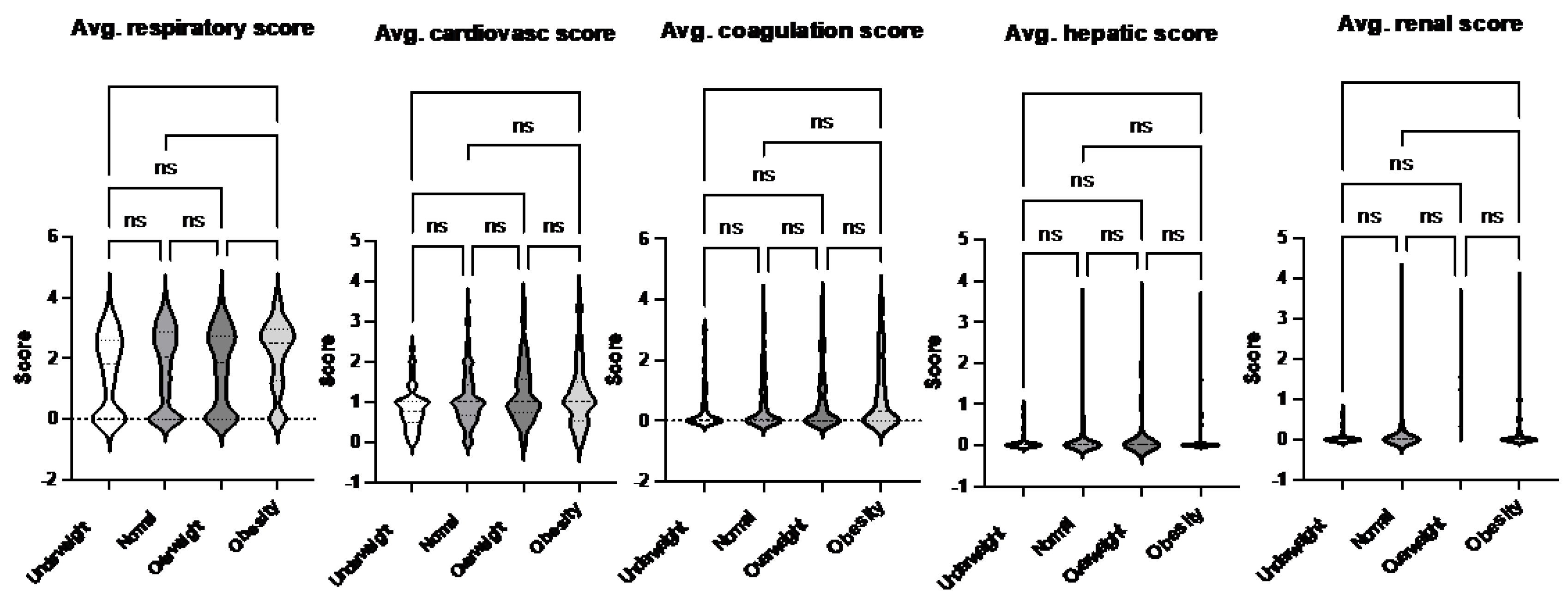

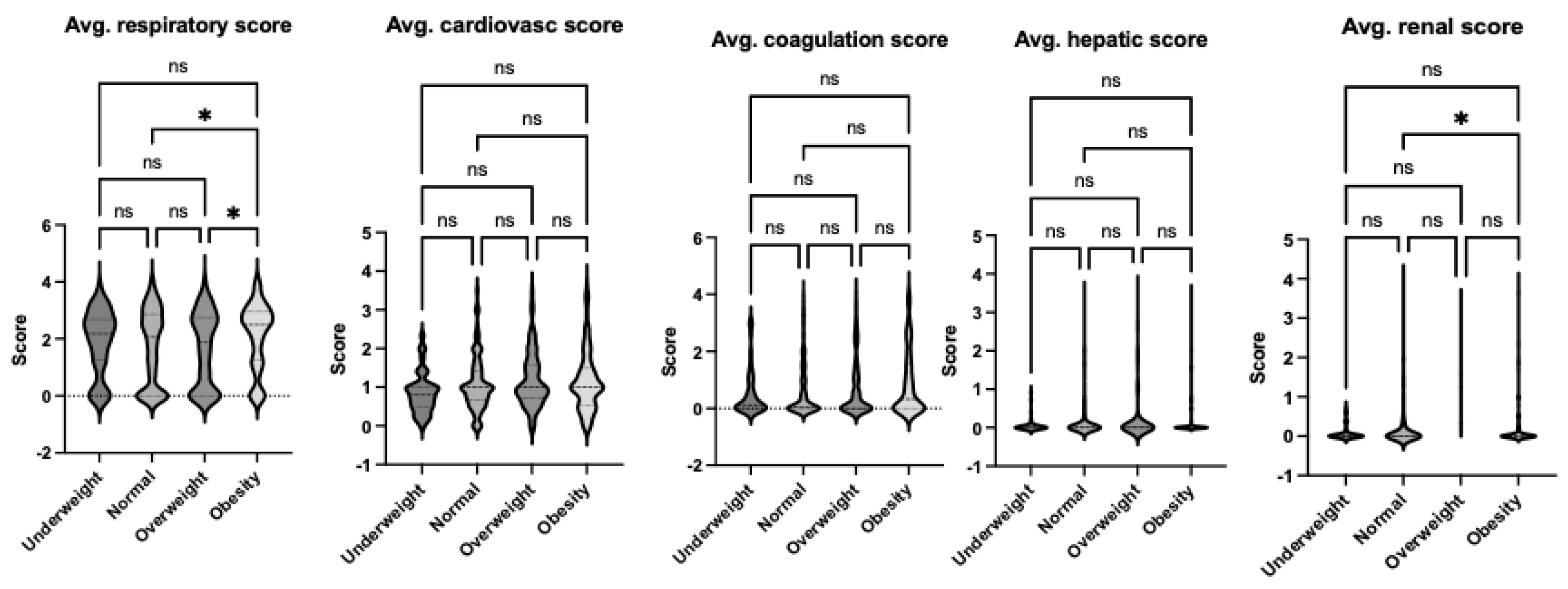

Figure 1). This finding aligns with observed differences in organ injury scores. Specifically, the average respiratory and renal organ injury scores during hospital admission were significantly higher in the obese group compared to the normal weight group (

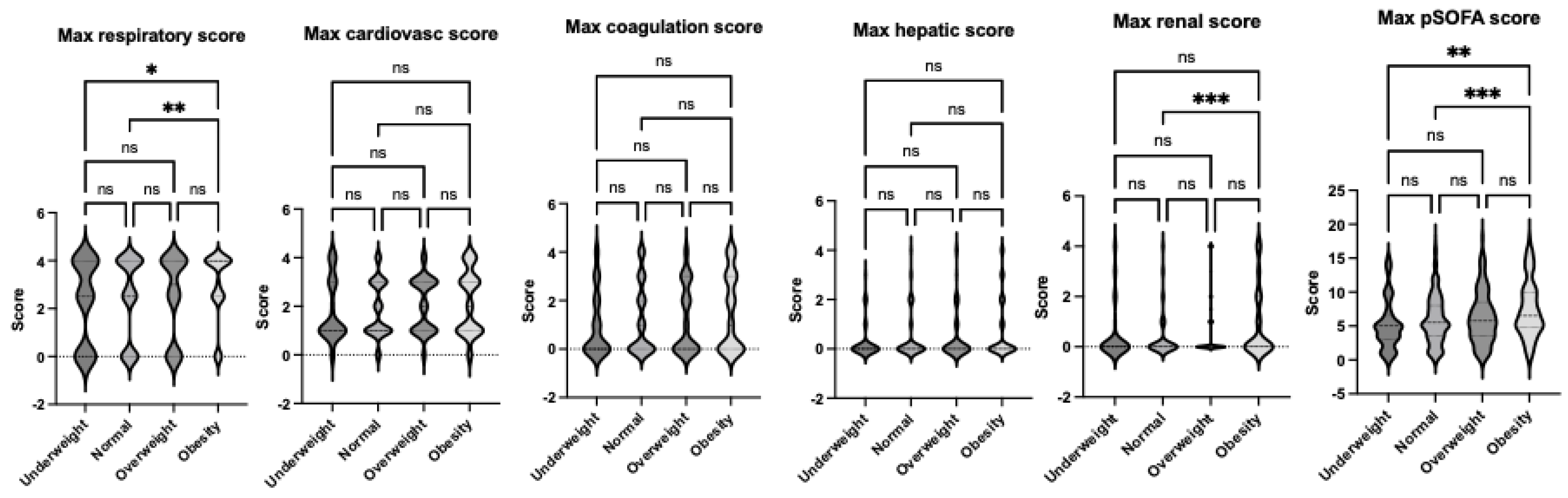

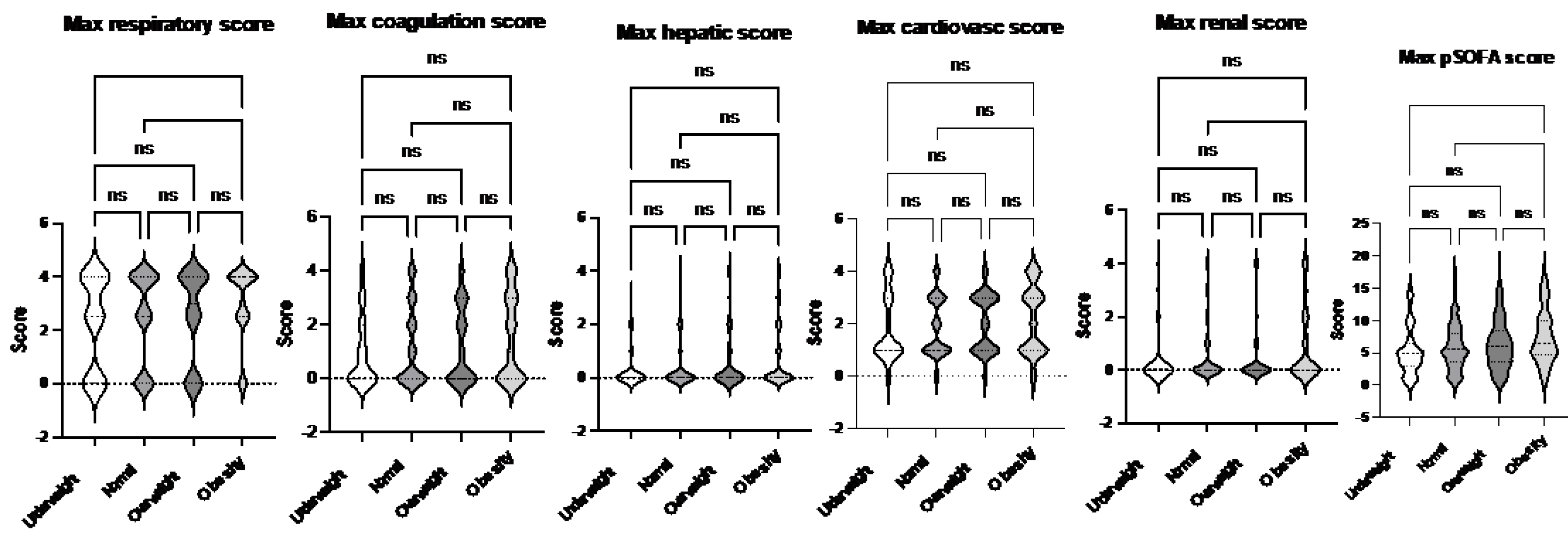

Figure 2). These findings suggest that obesity may exacerbate the severity of respiratory and renal dysfunction in pediatric patients with sepsis. Neurological impairment associated with infection was not apparent in this cohort, as no significant differences in neurological scores were identified among the groups. When analyzing the worst organ injury scores recorded during the hospital stay, the same trends persisted (

Figure 3). Additionally, the total worst organ injury score was significantly worse in the obese group than in the normal weight group (

Figure 3), further corroborating the higher mortality observed in obese patients (

Figure 1). These findings highlight the association between obesity and worse clinical outcomes, including higher organ injury scores and increased mortality, in pediatric patients with sepsis.

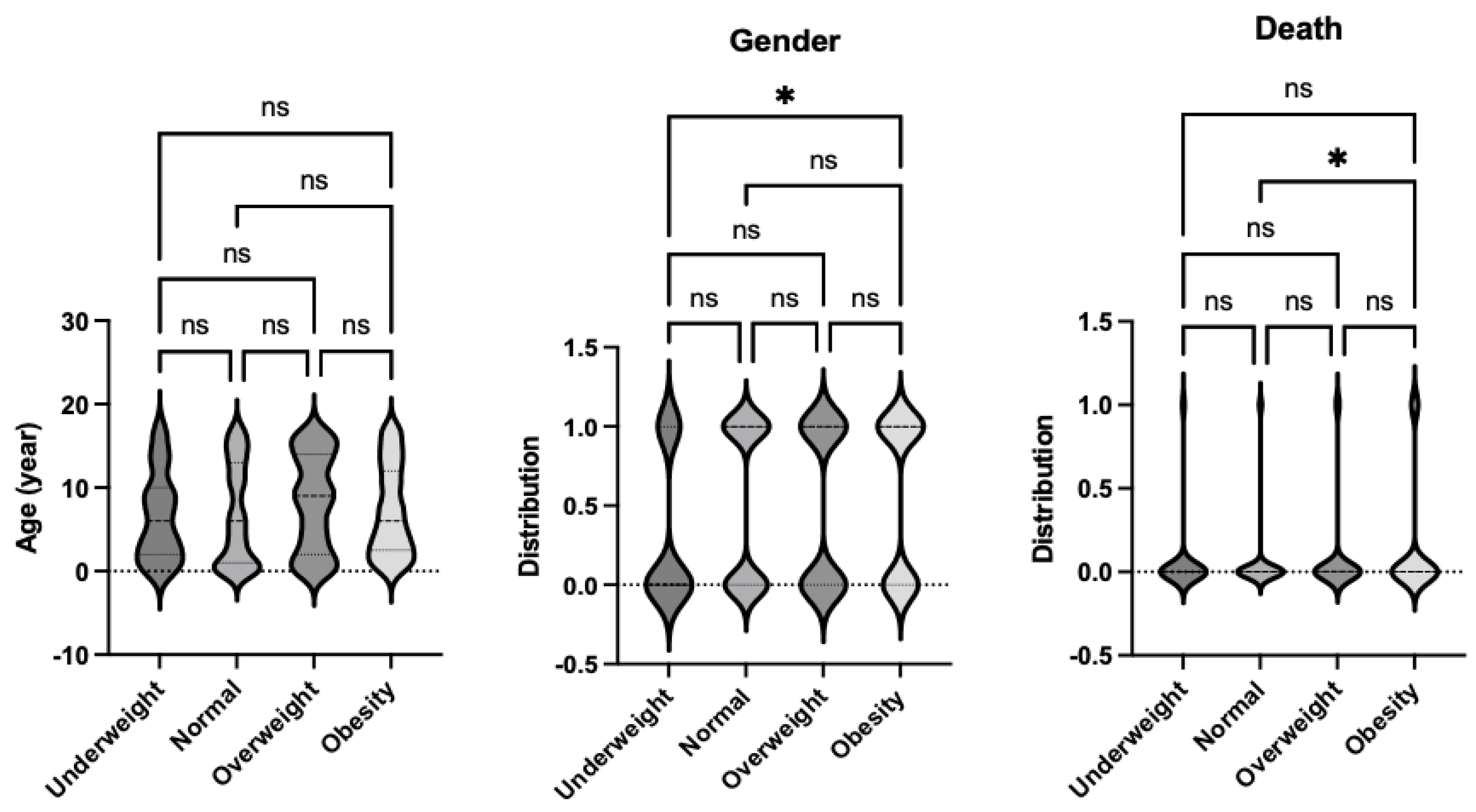

3.2. Obese Children Also Had Worse Survival and More Organ Dysfunction Under the Phoenix Criteria

We then analyzed the data on pediatric sepsis defined under the newly established Phoenix criteria, which incorporates stricter diagnostic guidelines compared to the previous Sepsis-2 definition. Nine patients who were previously classified as having sepsis under Sepsis-2 did not meet the criteria under the Phoenix system. This refined cohort data is detailed in

Table 3. As with the Sepsis-2 analysis, no significant differences in age were identified among the four body habitus groups: underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese. However, the underweight group again showed a higher proportion of female patients compared to the other groups (

Figure 4).

The obesity group had the highest mortality rate among all groups, consistent with the findings under Sepsis-2 criteria (

Figure 4). When examining organ injury scores during admission, the obese group demonstrated significantly greater respiratory and renal dysfunction compared to the normal weight group, as reflected in the average organ injury scores (

Figure 5). This trend persisted when the worst organ injury scores recorded during the hospital stay were analyzed. The obese group consistently exhibited the highest levels of respiratory and renal dysfunction compared to the normal weight group (

Figure 6). Furthermore, the total worst organ injury score was significantly higher in the obese group than in the other groups (

Figure 6), mirroring the higher mortality rate observed in this group (

Figure 4). These findings reaffirm that still under the Phoenix criteria, pediatric sepsis patients with obesity exhibit severe clinical outcomes, including increased organ dysfunction and mortality, compared to their no-obese counterparts.

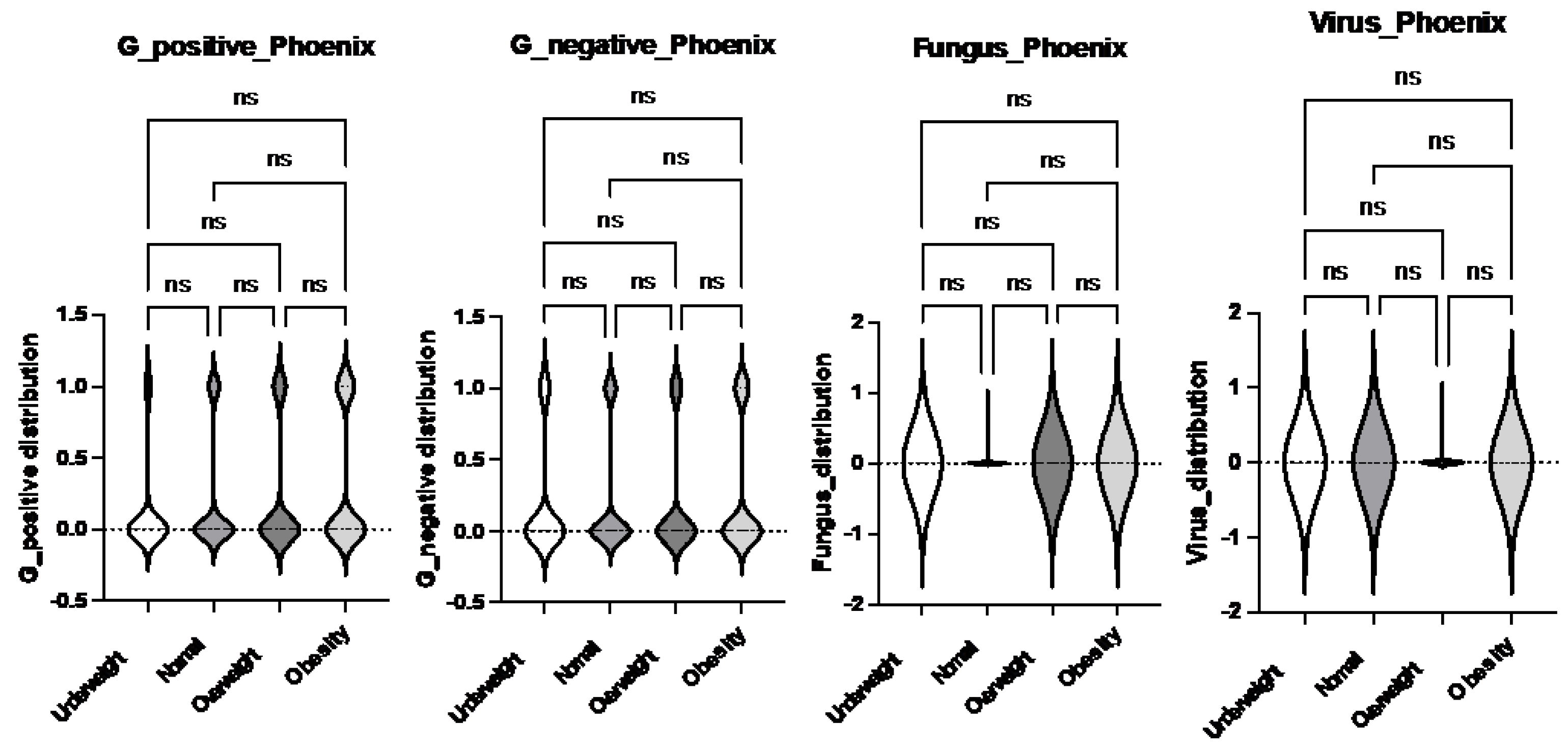

3.3. No Difference in the Frequency of Gram Positive, Negative, Fungal or Viral Sepsis Was Identified Based on the Body Habitus

Different microbial pathogens interact differently with the host immune system, potentially influencing the severity and outcomes of infections [

22]. To assess whether the type of pathogen contributed to differences in clinical outcomes across body habitus groups (underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese), we analyzed the incidence of these microbes in our cohort. We categorized the identified pathogens based on their type—Gram-positive bacteria, Gram-negative bacteria, fungi, and viruses—and compared their distribution across the body habitus groups. No significant differences were observed in the incidence of these pathogens among the groups (

Figure 7). These findings suggest that body habitus, rather than the specific pathogen type, might play a more significant role in influencing morbidity and mortality in pediatric sepsis.

Discussion

In this study, we identified that obese pediatric sepsis population had the worst outcome of sepsis compared to normal weight group, using for the first time the new phoenix criteria of pediatric sepsis [

20].

In line with our results, the study of 454 pediatric ICU (PICU) patients by Peterson et al. reported that although PICU mortality and length of stay were similar for obese/overweight patients (BMI> 85%tile) and normal weight (5%tile < BMI < 85%tile) critically ill children with sepsis, there was significantly higher use of specialized organ-supportive technology (such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) among overweight/obese patients, likely indicating a higher occurrence of multiple organ dysfunction [

13]. In accordance, another meta-analysis study showed that critically ill children with obesity, exhibited higher mortality compared to patients without obesity. In addition, the length of hospital stay was significantly higher in the group with obesity compared to those without obesity. Duration of ICU stay and need for mechanical ventilation (MV) were also tended to be longer in children with obesity, although not statistically significant [

15]. It has been stated that even in the lack of significant difference in mortality between groups with and without obesity in severely injured children and adolescents, children with obesity had longer duration of ICU stay and more complications such as sepsis and wound infection [

23]. In another study across multiple pediatric intensive care units in the U.S. studying the effect of obesity on mortality in critically ill children, age >15 years was associated with increased mortality in children with obesity [

24]. Another retrospective cohort from the same group showed no association between obesity status and mortality in children with severe sepsis [

25]. However, they found that both overweight and obesity had higher association in receiving mechanical ventilation, and longer intensive care unit stay.

In contrast, one study in the pediatric population using the Kids Inpatient Database (KID) and National Inpatient Sample (NIS) from 2003 to 2014 evaluated the effect of obesity and morbid obesity on outcomes in severe sepsis, suggesting that mortality in the obesity group was lower compared to morbid obesity and control groups [

26]. In the adult sepsis, the “obesity paradox” has been described, where obesity has been associated with lower mortality in sepsis with plethora of clinical studies supporting this idea in intensive care unit patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. An international multicenter cohort study assessing the effect of obesity by BMI, on hospital mortality in septic shock patients showed that obese and very obese patients had lower hospital mortality compared to normal weight patients. However, after adjusting for baseline characteristics and sepsis interventions, the association became non-significant [

27]. Another multi-center retrospective study across 139 hospitals in the U.S. showed that BMI was inversely associated with mortality in 55, 000 adults with sepsis [

28]. In a meta-analysis, using four retrospective (n = 6609 patients) and two prospective (n = 556) studies, it was also showed that overweight or obese BMIs reduce adjusted mortality in adults admitted to the ICU with sepsis, severe sepsis, or septic shock. A very recent retrospective cohort study showed also that unintentional weight loss was positively associated with a greater risk of mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis in the ICU [

29]. One more retrospective study in sepsis revealed patients with a low BMI had increased mortality [

30]. In agreement with the sepsis data, the concept of obesity paradox has been reported in various other disease populations such as acute respiratory distress syndrome, stroke, chronic renal disease, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cirrhosis and metastatic malignancy [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36].

Many different hypotheses have been proposed to explain this protective effect of obesity. In one hand, excess adipose tissue fat stores, may serve as a reservoir of energy to be used during the catabolic state created by sepsis-related inflammation [

37,

38]. Other possible explanations are related to the immunomodulatory effect of the adipose tissue and possible differential sepsis related systemic inflammatory response among patients with obesity compared to control population leading to dampening of the pro-inflammatory mediators and contributing to a favorable outcome [

37,

39]. It has been also suggested that there could be a selection bias among patients with obesity with severe sepsis being cared for in intensive care units and end up being recipients of more aggressive therapy in anticipation of a difficult clinical course which may partly explaining the obesity paradox [

26]. Many experts also state that the ‘obesity paradox’ entity is merely based on most observational studies as a result of selection bias and other methodological errors rather than a true entity and discourage the use of this terminology [

40,

41]. Hence it is important to acknowledge the limitations, the influence of confounders and unmeasured entities (genetic factors, body composition, immune response and illness severity) on outcomes, which might contribute to the findings in our study. On top of that, some more clinical studies come to challenge the “obesity paradox”. For instance, a retrospective cohort analysis in sepsis suggested that obese and morbidly obese experienced decreased mortality risk, vs. normal BMI; however, after adjustment for baseline characteristics, this was no longer significant. There was no significant difference in length of stay (LOS) in the ICU across BMI groups. Neither LOS nor adjusted 28-day mortality was significantly increased or decreased in underweight or obese patients with severe sepsis. It was suggested that morbidly obese patients may have decreased 28-day mortality, partially due to differences in initial presentation and source of infection[

42]. Another study investigating the possible impact of obesity, as assessed by the BMI, on morbidity and mortality in ICU patients included in the European observational sepsis occurrence in acutely ill patients (SOAP) study suggested that obesity is associated with increased morbidity but not mortality in critically ill patients [

43].

More recently, a meta-analysis study of genome-wide association studies exploring the relationship between life course adiposity and sepsis in both childhood and adulthood suggested that adiposity in childhood and adults had causal effects on sepsis incidence. Specifically, using the Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis of inverse variance weighted method revealed that genetic predisposition to increased childhood BMI (OR = 1.29, P = 0.003), childhood obesity (OR = 1.07, P = 0.034), adult BMI (OR = 1.38, P < 0.001), adult waist circumference (OR = 1.01, P = 0.028), and adult visceral adiposity (OR = 1.53, P < 0.001) predicted a higher risk of sepsis [

21].

In addition, the majority of the animal data have associated obesity with more organ injury[

44,

45], which is in line with our findings in the pediatric population. A recent review on diet-induced obesity murine models found that among seventeen studies with the majority of them using male C57BL/6 mice, cecal ligation and puncture to induce sepsis, and high-fat diets, seven (64%) studies reported increased mortality in obese septic mice, one (9%) observed a decrease, and three (37%) found no significant difference. The liver, lungs, and kidneys were the most studied organs. Alanine transaminase results were inconclusive. Myeloperoxidase levels were increased in the livers of two studies and inconclusive in the lungs of obese septic mice. Creatinine and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin were elevated in obese septic mice [

46]. Interestingly, obese patients had more respiratory and renal dysfunction. Obese patients tend to require more intrathoracic pressure to maintain the same level of ventilation compared to normal habitus patients. Obese patients have more body mass, which may lead to higher creatinine release.

Lastly, our study showed that the worst sepsis outcome that was observed in this study associated with obesity could not be attributed to differences in the type of pathogens that caused the infection, suggesting more intrinsic host mechanisms associated with obesity in sepsis. Overall, the lack of variation in pathogen incidence by body habitus underscores the importance of focusing on host factors, such as body habitus and its physiological implications and in understanding the mechanisms driving differences in morbidity and mortality in pediatric sepsis. Further research could investigate how these host factors interact with immune responses to infections and whether targeted interventions for specific body habitus groups might improve outcomes.

Limitations

Single-center studies are valuable for providing detailed insights into specific populations or settings providing controlled conditions and detailed data collection. However, they have some limitations that we need to take into consideration when interpreting the results. Findings from a single-center study may not reflect an easily or straight forward generalization due to differences in patient demographics, local healthcare practices, resources, or infrastructure. The small sample size can limit the statistical power and the ability to detect significant effects or trends.

In addition, the observational and retrospective nature of the study can identify associations but cannot establish cause-and-effect relationships due to the absence of controlled interventions. Uncontrolled confounders, such as unmeasured factors that influence both exposure and outcome, can bias the results as well. In addition, the study’s limitations include using weight and laboratory data only from the first day of PICU admission, preventing analysis of how daily changes affect outcomes and resource use. Accurate height assessment in critically ill neonates and infants (aged 0–2 years) is also challenging, with supine length being the most common method for evaluating stature in this group. Additionally, the lack of data on mortality and morbidity beyond PICU discharge limits the evaluation of weight status on readmissions, late mortality, long-term functional outcomes, and resource use among survivors.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study underscores the critical association between obesity and poor outcomes in pediatric sepsis, particularly when analyzed under the newly introduced Phoenix definition. Our findings reveal that obese children with sepsis experience increased mortality, greater organ dysfunction, and higher organ injury scores compared to their normal-weight and over-weight counterparts, aligning with previous literature on the adverse effects of obesity in critically ill pediatric populations. The study highlights the need for standardized definitions and larger, multi-center investigations to validate these findings and address existing controversies surrounding the “obesity paradox” observed in adult and pediatric sepsis. Additionally, the study’s limitations, regarding its single-center, retrospective design emphasize the necessity for future research to explore the long-term impact of obesity on pediatric sepsis outcomes and identify targeted interventions for this vulnerable population. These insights have the potential to guide more effective management strategies and improve survival rates in obese children with sepsis.

List of abbreviations

| Body mass index (BMI) |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) |

| Diabetes mellitus (DM) |

| Electronic medical record (EMR) |

| Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) |

| Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) |

| Institutional Review Board (IRB) |

| Intensive care unit (ICU) |

| International Classification of Diseases (ICD) |

| International Pediatric Sepsis Consensus Conference (IPSCC) |

| Interquartile range (IQR) |

| Kids Inpatient Database (KID) |

| Length of stay (LOS) |

| Mechanical ventilation (MV) |

| Mendelian randomization (MR) |

| National Inpatient Sample (NIS) |

| Pediatric Intensive care unit (PICU) |

| Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction version 2 (PELOD-2) |

| Pediatric Organ Dysfunction Information Update Mandate (PODIUM) |

| Pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (pSOFA) |

| Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) |

| Sepsis Occurrence in Acutely ill Patients (SOAP) |

| Standard deviation (SD) |

| Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) |

Funding

This study is in part supported by R21HD099194 (K.Y., S.K.). CHMC Anesthesia Foundation (S.K., K.Y.)

Authors’ contributions

K.Y performed data collection and analysis. Both K.Y and S.K. conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the manuscript, contributed to data interpretation, and approved the final manuscript for submission. S.K. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript and take responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the data presented.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study was conducted as a retrospective, single-center cohort analysis and received approval from the Institutional Review Board at Boston Children’s Hospital (IRB approval number IRB-P00041981).

Consent for Publication

Not applicable. This study does not include individual patient data or identifiable information.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Guarino M, Perna B, Cesaro AE, Maritati M, Spampinato MD, Contini C, et al. 2023 Update on Sepsis and Septic Shock in Adult Patients: Management in the Emergency Department. J Clin Med. 2023;12(9). [CrossRef]

- Cox MI, Voss H. Improving sepsis recognition and management. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2021;51(4):101001. [CrossRef]

- Uffen JW, Oosterheert JJ, Schweitzer VA, Thursky K, Kaasjager HAH, Ekkelenkamp MB. Interventions for rapid recognition and treatment of sepsis in the emergency department: a narrative review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(2):192-203. [CrossRef]

- Howell MD, Davis AM. Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock. JAMA. 2017;317(8):847-8.

- Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, Antonelli M, Coopersmith CM, French C, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock Crit Care Med. 2021;49(11):e1063-e143.

- Henriksen DP, Pottegard A, Laursen CB, Jensen TG, Hallas J, Pedersen C, et al. Risk factors for hospitalization due to community-acquired sepsis - a population-based case-control study. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0124838. [CrossRef]

- Martin GS, Mannino DM, Moss M. The effect of age on the development and outcome of adult sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(1):15-21. [CrossRef]

- Wang HE, Donnelly JP, Griffin R, Levitan EB, Shapiro NI, Howard G, et al. Derivation of Novel Risk Prediction Scores for Community-Acquired Sepsis and Severe Sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(7):1285-94. [CrossRef]

- Wang HE, Griffin R, Judd S, Shapiro NI, Safford MM. Obesity and risk of sepsis: a population-based cohort study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21(12):E762-9. [CrossRef]

- Apovian CM. Obesity: definition, comorbidities, causes, and burden. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(7 Suppl):s176-85.

- Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, Ard JD, Comuzzie AG, Donato KA, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2985-3023.

- Yeo HJ, Kim TH, Jang JH, Jeon K, Oh DK, Park MH, et al. Obesity Paradox and Functional Outcomes in Sepsis: A Multicenter Prospective Study. Crit Care Med. 2023;51(6):742-52. [CrossRef]

- Peterson LS, Gallego Suarez C, Segaloff HE, Griffin C, Martin ET, Odetola FO, et al. Outcomes and Resource Use Among Overweight and Obese Children With Sepsis in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. J Intensive Care Med. 2020;35(5):472-7. [CrossRef]

- Randolph AG, McCulloh RJ. Pediatric sepsis: important considerations for diagnosing and managing severe infections in infants, children, and adolescents. Virulence. 2014;5(1):179-89.

- Alipoor E, Hosseinzadeh-Attar MJ, Yaseri M, Maghsoudi-Nasab S, Jazayeri S. Association of obesity with morbidity and mortality in critically ill children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Obes (Lond). 2019;43(4):641-51. [CrossRef]

- Irving SY, Daly B, Verger J, Typpo KV, Brown AM, Hanlon A, et al. The Association of Nutrition Status Expressed as Body Mass Index z Score With Outcomes in Children With Severe Sepsis: A Secondary Analysis From the Sepsis Prevalence, Outcomes, and Therapies (SPROUT) Study. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(11):e1029-e39. [CrossRef]

- Wheeler DS, Wong HR, Zingarelli B. Pediatric Sepsis - Part I: “Children are not small adults!”. Open Inflamm J. 2011;4:4-15.

- Goldstein B, Giroir B, Randolph A, International Consensus Conference on Pediatric S. International pediatric sepsis consensus conference: definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction in pediatrics. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6(1):2-8. [CrossRef]

- Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801-10. [CrossRef]

- Schlapbach LJ, Watson RS, Sorce LR, Argent AC, Menon K, Hall MW, et al. International Consensus Criteria for Pediatric Sepsis and Septic Shock. JAMA. 2024;331(8):665-74. [CrossRef]

- Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Guo SS, Wei R, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data. 2000(314):1-27.

- Casadevall A, Pirofski LA. Host-pathogen interactions: basic concepts of microbial commensalism, colonization, infection, and disease. Infect Immun. 2000;68(12):6511-8. [CrossRef]

- Brown CV, Neville AL, Salim A, Rhee P, Cologne K, Demetriades D. The impact of obesity on severely injured children and adolescents. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(1):88-91; discussion 88-91. [CrossRef]

- Ross PA, Newth CJ, Leung D, Wetzel RC, Khemani RG. Obesity and Mortality Risk in Critically Ill Children. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20152035. [CrossRef]

- Ross PA, Klein MJ, Nguyen T, Leung D, Khemani RG, Newth CJL, et al. Body Habitus and Risk of Mortality in Pediatric Sepsis and Septic Shock: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Pediatr. 2019;210:178-83 e2. [CrossRef]

- Thavamani A, Umapathi KK, Sankararaman S, Roy A. Effect of obesity on mortality among hospitalized paediatric patients with severe sepsis. Pediatr Obes. 2021;16(8):e12777. [CrossRef]

- Arabi YM, Dara SI, Tamim HM, Rishu AH, Bouchama A, Khedr MK, et al. Clinical characteristics, sepsis interventions and outcomes in the obese patients with septic shock: an international multicenter cohort study. Crit Care. 2013;17(2):R72. [CrossRef]

- Pepper DJ, Demirkale CY, Sun J, Rhee C, Fram D, Eichacker P, et al. Does Obesity Protect Against Death in Sepsis? A Retrospective Cohort Study of 55,038 Adult Patients. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(5):643-50. [CrossRef]

- Lin W, Lin B, Chen J, Li R, Yu Y, Huang S, et al. Impact of unintentional weight loss on 30-day mortality in intensive care unit sepsis patients: a retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):31535. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Hu X, Xu J, Huang F, Guo Z, Tong L, et al. Increased body mass index linked to greater short- and long-term survival in sepsis patients: A retrospective analysis of a large clinical database. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;87:109-16. [CrossRef]

- Zhi G, Xin W, Ying W, Guohong X, Shuying L. “Obesity Paradox” in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Asystematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0163677. [CrossRef]

- Oesch L, Tatlisumak T, Arnold M, Sarikaya H. Obesity paradox in stroke - Myth or reality? A systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0171334. [CrossRef]

- Kalantar-Zadeh K, Rhee CM, Chou J, Ahmadi SF, Park J, Chen JL, et al. The Obesity Paradox in Kidney Disease: How to Reconcile it with Obesity Management. Kidney Int Rep. 2017;2(2):271-81. [CrossRef]

- Oreopoulos A, Padwal R, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Fonarow GC, Norris CM, McAlister FA. Body mass index and mortality in heart failure: a meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2008;156(1):13-22. [CrossRef]

- Hastie CE, Padmanabhan S, Slack R, Pell AC, Oldroyd KG, Flapan AD, et al. Obesity paradox in a cohort of 4880 consecutive patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(2):222-6. [CrossRef]

- Lennon H, Sperrin M, Badrick E, Renehan AG. The Obesity Paradox in Cancer: a Review. Curr Oncol Rep. 2016;18(9):56. [CrossRef]

- Kalani C, Venigalla T, Bailey J, Udeani G, Surani S. Sepsis Patients in Critical Care Units with Obesity: Is Obesity Protective? Cureus. 2020;12(2):e6929.

- Robinson MK, Mogensen KM, Casey JD, McKane CK, Moromizato T, Rawn JD, et al. The relationship among obesity, nutritional status, and mortality in the critically ill. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(1):87-100.

- Wacharasint P, Boyd JH, Russell JA, Walley KR. One size does not fit all in severe infection: obesity alters outcome, susceptibility, treatment, and inflammatory response. Crit Care. 2013;17(3):R122. [CrossRef]

- Flegal KM, Ioannidis JPA. The Obesity Paradox: A Misleading Term That Should Be Abandoned. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2018;26(4):629-30. [CrossRef]

- Banack HR, Stokes A. The ’obesity paradox’ may not be a paradox at all. Int J Obes (Lond). 2017;41(8):1162-3.

- Gaulton TG, Marshall MacNabb C, Mikkelsen ME, Agarwal AK, Cham Sante S, Shah CV, et al. A retrospective cohort study examining the association between body mass index and mortality in severe sepsis. Intern Emerg Med. 2015;10(4):471-9. [CrossRef]

- Sakr Y, Madl C, Filipescu D, Moreno R, Groeneveld J, Artigas A, et al. Obesity is associated with increased morbidity but not mortality in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(11):1999-2009. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan JM, Nowell M, Lahni P, Shen H, Shanmukhappa SK, Zingarelli B. Obesity enhances sepsis-induced liver inflammation and injury in mice. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24(7):1480-8. [CrossRef]

- Lewis ED, Williams HC, Bruno MEC, Stromberg AJ, Saito H, Johnson LA, et al. Exploring the Obesity Paradox in A Murine Model of Sepsis: Improved Survival Despite Increased Organ Injury in Obese Mice. Shock. 2022;57(1):151-9. [CrossRef]

- Eng M, Suthaaharan K, Newton L, Sheikh F, Fox-Robichaud A, National Preclinical Sepsis Platform SC. Sepsis and obesity: a scoping review of diet-induced obesity murine models. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2024;12(1):15. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Comparison of demographics and mortality of septic patients based on sepsis-2 per body habitus. Age, gender and mortality were compared among underweight, normal, overweight and obese patients. Dunn’s multiple comparison tests were used for age. For gender and mortality, logistic regression analysis was performed. * p< 0.05.

Figure 1.

Comparison of demographics and mortality of septic patients based on sepsis-2 per body habitus. Age, gender and mortality were compared among underweight, normal, overweight and obese patients. Dunn’s multiple comparison tests were used for age. For gender and mortality, logistic regression analysis was performed. * p< 0.05.

Figure 2.

Comparison of average organ scores of septic patients based on sepsis-2 per body habitus. Dunn’s multiple comparison tests were used. * p< 0.05.

Figure 2.

Comparison of average organ scores of septic patients based on sepsis-2 per body habitus. Dunn’s multiple comparison tests were used. * p< 0.05.

Figure 3.

Comparison of maximum organ scores of septic patients based on sepsis-2 per body habitus. Dunn’s multiple comparison tests were used. *. **, and ***, p< 0.05, < 0.01 and < 0.001, respectively.

Figure 3.

Comparison of maximum organ scores of septic patients based on sepsis-2 per body habitus. Dunn’s multiple comparison tests were used. *. **, and ***, p< 0.05, < 0.01 and < 0.001, respectively.

Figure 4.

Comparison of demographics and mortality of septic patients based on Phoenix score per body habitus. Age, gender and mortality were compared among underweight, normal, overweight and obese patients. Dunn’s multiple comparison tests were used for age. For gender and mortality, logistic regression analysis was performed. * p< 0.05.

Figure 4.

Comparison of demographics and mortality of septic patients based on Phoenix score per body habitus. Age, gender and mortality were compared among underweight, normal, overweight and obese patients. Dunn’s multiple comparison tests were used for age. For gender and mortality, logistic regression analysis was performed. * p< 0.05.

Figure 5.

Comparison of average organ scores of septic patients based on Phoenix score per body habitus. Dunn’s multiple comparison tests were used. * p< 0.05.

Figure 5.

Comparison of average organ scores of septic patients based on Phoenix score per body habitus. Dunn’s multiple comparison tests were used. * p< 0.05.

Figure 6.

Comparison of maximum organ scores of septic patients based on Phoenix score per body habitus. Dunn’s multiple comparison tests were used. ** and ***, p< 0.01 and p< 0.001, respectively.

Figure 6.

Comparison of maximum organ scores of septic patients based on Phoenix score per body habitus. Dunn’s multiple comparison tests were used. ** and ***, p< 0.01 and p< 0.001, respectively.

Figure 7.

Comparison of frequency of bacterial, viral and fungal sepsis per Phoenix criteria per body habitus. Logistic regression analysis was performed. No statistical significance was observed.

Figure 7.

Comparison of frequency of bacterial, viral and fungal sepsis per Phoenix criteria per body habitus. Logistic regression analysis was performed. No statistical significance was observed.

Table 1.

Respiratory, cardiovascular, coagulation, hepatic, renal and neurological dysfunction scoring systems originally tested for the development of Phoenix criteria.

Table 1.

Respiratory, cardiovascular, coagulation, hepatic, renal and neurological dysfunction scoring systems originally tested for the development of Phoenix criteria.

| Variables |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

| Respiratory (0-3 points) |

|

| PaO2/FiO2

|

>400 |

< 400 +RS |

100~200+RS |

<100 +RS |

|

| Or |

|

|

|

|

|

| SpO2/FiO2

|

>292 |

< 292 +RS |

148-220 +RS |

< 148 + RS |

|

| Coagulation (0-2 points) * 1 point each, max 2 points |

|

Platelet (x103/µL)

INR

D-Dimer (mg/L)

Fibrinogen (mg/dL) |

>100

< 1.3

< 2

>100 |

< 100

>1.3

>2

<100 |

|

|

|

| Hepatic (0-1 point) |

|

|

|

Bilirubin(mg/dL)

ALT (IU/L) |

<4

<102 |

> 4

> 102 |

|

|

|

| Cardiovascular (0-6 points). 1 point each 2 points each |

|

Vasoactive drugs

Lactate <mmol/L)

MAP |

No

< 5 |

1

5-10.9 |

2~

>11 |

|

|

| <1 mo |

>30 |

<17-30 |

<17 |

|

|

| 1-11 mo |

>38 |

<25-38 |

<25 |

|

|

| 12-23 mo |

>43 |

<31-43 |

<31 |

|

|

| 24-59 mo |

>44 |

<32-44 |

<32 |

|

| 60-143 mo |

>48 |

<36-48 |

<36 |

|

| 144-216 mo |

>51 |

<38-51 |

<38 |

|

| Neurologic (0-2 points) |

GCS

Pupil reactivity |

>10

Reactive |

<10 |

Fixed bilaterally |

| Renal (0-1 point) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) |

|

|

|

| <1 mo |

<0.8 |

0.8> |

|

|

| 1-11 mo |

<0.3 |

0.3> |

|

|

| 12-23 mo |

<0.4 |

0.4> |

|

|

| 24-59 mo |

<0.6 |

0.6> |

|

|

| 60-143 mo |

<0.7 |

0.7> |

|

|

| 144-216 mo |

<1.0 |

1.0> |

|

|

| ALT, alanine aminotransferase; mo, month; MAP, mean arterial pressure; GCS, Glascow Coma Score |

Table 2.

Sepsis-2 definition based data.

Table 2.

Sepsis-2 definition based data.

| |

Underweight (n=52) |

Normal (n=333) |

Overweight (n=115) |

Obesity

(n=141) |

| Age |

6 (2, 10) |

6 (1, 13) |

9 (2, 14) |

6 (2.5, 12) |

| Gender |

m 18, f 34 |

m 173, f 160 |

m 58, f 57 |

m 80, f 61 |

| Avg. Respiratory score |

1.84 (0, 2.60) |

2.06 (0, 2.88) |

1.88 (0, 2.75) |

2.50 (1.25, 2.96) |

| Avg. Cardiovasc score |

0.78 (0.50, 1.00) |

1.00 (0.67, 1.41) |

1.00 (0.72, 1.58) |

1.00 (0.54, 1.50) |

| Avg. Coagulation score |

0 (0, 0.51) |

0.05 (0, 1.06) |

0 (0, 1.00) |

0.33 (0, 1.55) |

| Avg. Hepatic score |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 0.15) |

| Avg. Renal score |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 0.28) |

| Max. Respiratory score |

2.5 (0, 4) |

2.5 (0, 4) |

3 (0, 4) |

4 (2.5, 4) |

| Max. Cardiovasc score |

1 (1, 3) |

1 (1, 3) |

2 (1, 3) |

2 (1, 3) |

| Max. Coagulation score |

0 (0, 2) |

1 (0, 2) |

0 (0, 3) |

1 (0, 3) |

| Max. Hepatic score |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 1) |

| Max. Renal score |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 2.5) |

0 (0, 2) |

| Total score |

5 (3, 6.5) |

5.5 (3.5, 8) |

5.8 (3.5, 8.5) |

6.5 (4.8, 10) |

| Death (%) |

2 (3.8%) |

18 (5.4%) |

8 (7.0%) |

18 (12.8%) |

Table 3.

Phoenix criteria-based data.

Table 3.

Phoenix criteria-based data.

| |

Underweight (n=43) |

Normal

(n=333) |

Overweight (n=115) |

Obesity

(n=141) |

| Age |

6 (2, 10) |

6 (1, 13) |

9 (2, 9) |

6 (2.5, 12) |

| Gender |

m 14, f 29 |

m 173, f 160 |

m 58, f 57 |

m 61, f 80 |

| Avg. respiratory score |

2.18 (1.25, 2.69) |

2.06 (0, 2.88) |

1.88 (0, 2.75) |

2.50 (1.25, 2.96) |

| Avg. Cardiovasc score |

0.80 (0.50, 1.00) |

1.00 (0.67, 1.41) |

1.00 (0.72, 1.58) |

1.00 (0.54, 1.50) |

| Avg. Coagulation score |

0.13 (0, 0.86) |

0.05 (0, 1.06) |

0 (0, 1.00) |

0.33 (0, 1.55) |

| Avg. Hepatic score |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 0.15) |

| Avg. Renal score |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 0.28) |

| Max. Respiratory score |

3 (2.5, 4) |

2.5 (0, 4) |

3 (0, 4) |

4 (2.5, 4) |

| Max. Cardiovasc score |

1 (1, 3) |

1 (1, 3) |

2 (1, 3) |

2 (1, 3) |

| Max. Coagulation score |

0 (1, 2) |

1 (0, 2) |

0 (0, 3) |

1 (0, 3) |

| Max. Hepatic score |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 1) |

| Max. Renal score |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 2.5) |

0 (0, 2) |

| Total score |

5 (3.5, 8.0) |

5.5 (3.5, 8) |

5.8 (3.5, 8.5) |

6.5 (4.8, 10) |

| Death (%) |

2 (4.7%) |

18 (5.4%) |

8 (7.0%) |

18 (12.8%) |

| Gram positive bacteria |

5 (11.6%) |

70 (21.0%) |

27 (23.5%) |

43 (30.5%) |

| Gram negative bacteria |

8 (18.6%) |

73 (21.9%) |

24 (20.9%) |

37 (26.2%) |

| Fungus |

0 (0%) |

1 (0.3%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

| Virus |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (0.9%) |

0 (0%) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).