1. Introduction

In today’s interconnected industrial landscape, where complexity and interdependence continue to grow, the digital transformation of industries and societies has emerged as a critical enabler for understanding the interplay between influencing domains within digitalized ecosystems, which has become essential for advancing sustainable and equitable strategies [

1,

2,

3]. Among essential domains, fairness, environmental impact, and behavior dynamics have become critical focal points as industries navigate growth [

4,

5]. Understanding the interplay among these three domains plays a crucial role in influencing modern digital industrial strategies. These domains, collectively referred to as the

Key Domains, influence and are influenced by crucial industrial and societal contexts, including the circular economy, business models, and supply chain management (referred to as the

Key Contexts) [

6,

7,

8].

The significance of these Key Domains within digital ecosystems is underscored by their role in shaping sustainable and equitable industrial strategies [

9]. For instance, fairness ensures that digitalized industrial processes and outcomes are just, equitable, and transparent, fostering trust and inclusivity among stakeholders [

10,

11]. Similarly, minimizing environmental impact is paramount to mitigating climate change, conserving resources, and ensuring long-term ecological balance, goals that digital tools and platforms can significantly enhance [

6,

12]. Meanwhile, behavior dynamics delve into the complexities of human and organizational actions, offering insights into how digital behaviors and interactions can align with sustainable goals through incentives, norms, and policies [

13,

14].

These domains are not isolated; their interactions within digitalized Key Contexts define the success or failure of modern industrial strategies [

2]. For example, understanding how digital behavioral incentives can promote circular economy strategies [

6,

7] or how fairness considerations can transform digitally integrated supply chains into more equitable systems is pivotal [

8,

15].

Yet, this interplay also introduces challenges in effectively integrating these domains within digitalized ecosystems [

1,

2]. For instance, ensuring fairness in digital industrial strategies often conflicts with the goals of efficiency and scalability [

16]. Efforts to reduce environmental impacts are frequently constrained by existing digital business models that prioritize short-term gains over long-term sustainability or struggle to integrate sustainable strategies into traditionally linear frameworks [

7,

12]. Adding to these challenges is the inherent complexity of human and organizational behavior. Digital behavior dynamics significantly influence how fairness and environmental goals are perceived and acted upon [

13,

14]. These challenges highlight the need for a novel approach that not only addresses individual domains but also considers the trade-offs and synergies that arise in their interactions within digital ecosystems. They highlight gaps in existing research and current digital business strategies, setting the stage for this survey’s contributions to offer a pathway toward resolving these complexities [

9,

15].

While other surveys address these areas individually or in combination with other domains [

2,

5], this survey adopts a contemporary perspective that explicitly incorporates the role of digital transformation in shaping these intersections. This is to address the challenges that have arisen from the increasing complexity and interdependence of modern industrial strategies through the lens of digitalization [

9].

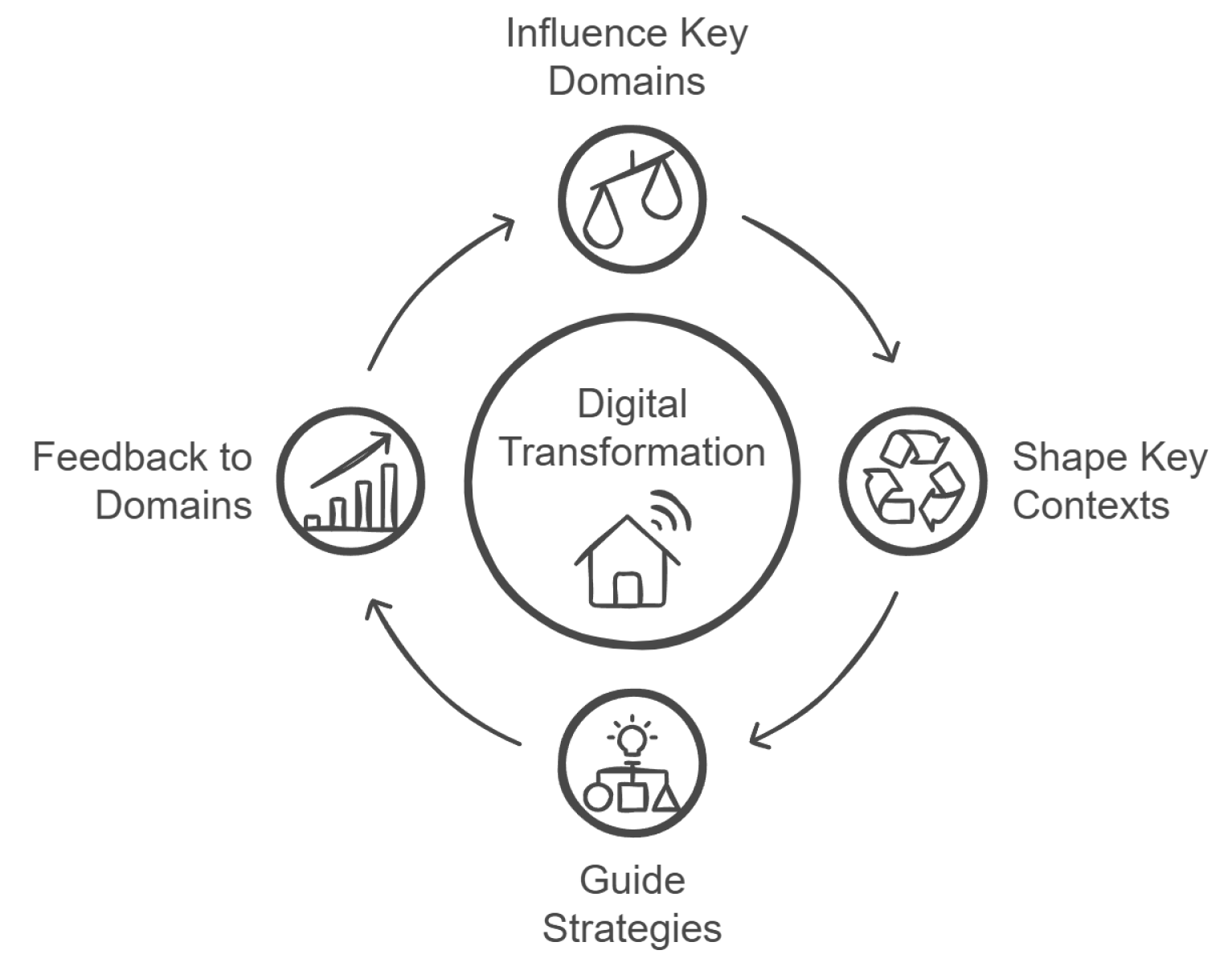

Here, we consider mechanisms and frameworks enabling data sharing within digital ecosystems but exclude processes such as digitizing physical operations or collecting data at the source. The focus is on understanding the interplay of fairness, environmental impact, and behavior dynamics within a digitalized ecosystem of circular economy, business models, and supply chain management (

Figure 1). Rather than limiting itself to a single perspective, this survey examines all possible combinations of these domains, often overlooked in broader studies, through a digital lens to ensure a comprehensive exploration of their interactions [

10,

17]. By considering the multifaceted nature of these domains, this paper’s primary objective is to provide a thorough analysis that captures the complexity of their relationships while situating them within the broader narrative of digital transformation [

2,

4].

In addition, this survey emphasizes the importance of these intersections in shaping sustainable and equitable digital industrial strategies [

9,

15]. It explores how digital behavioral incentives can encourage circular economy adoption [

6,

16] and how fairness principles can enhance equity within digitally integrated supply chains [

8,

17]. By identifying synergies, conflicts, and gaps in current research, this paper provides actionable insights to guide both theoretical advancements and practical applications [

5,

13]. The findings aim to equip researchers, industry professionals, and policymakers with digital tools and frameworks to align environmental, social, and behavioral objectives, addressing the challenges of modern industries with innovative and inclusive approaches [

1,

14]. The contributions of this paper can be categorized into three primary areas:

Foundational Concepts and State of the Art (

Section 3 and

Section 4): This section provides an extensive literature review covering the latest digital advancements in each Key Domain within the Key Contexts, including fairness in digital supply chains, environmental impact criteria in digitally-driven business models, and behavior dynamics within the circular economy. It identifies current trends, synergies, and gaps, situating this survey firmly within the digitalized industrial landscape.

Analysis and Practical Implications (

Section 5): The paper introduces a structured analysis of the interplay of fairness, environmental impact, and behavior dynamics within the digitalized Key Contexts. This analysis highlights both synergistic opportunities and areas where conflicts arise, offering theoretical value and a comprehensive understanding of how these domains interact in practice. It serves as a guide for advancing research on digital transformation and its role in sustainable and equitable business strategies.

Research Gaps and Future Directions (

Section 6): This survey identifies gaps in current research on the digital landscape and suggests specific areas for future investigation. Emphasizing interdisciplinary approaches, it proposes integrating fairness, environmental sustainability, and behavior dynamics into modern strategies for digitalized industries, encouraging innovation to improve sustainable and equitable strategies in the digital era.

Figure 1.

Interplay of Key Domains and Contexts.

Figure 1.

Interplay of Key Domains and Contexts.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section II outlines the methodology employed to synthesize and analyze the literature. Section III, Motivation and Challenges, provides a foundational understanding of the Key Domains and highlights the complexities involved in addressing their intersections within the digitalized Key Contexts. Section IV offers a comprehensive review of the state of the art, focusing on advancements across the Key Domains within these digital contexts. Section V presents a structured analysis of the interactions among these domains, emphasizing synergies, conflicts, and practical implications within digital transformation. Finally, Section VI identifies research gaps and proposes directions for future work, with concluding remarks summarizing key findings in Section VII.

2. Methodology

Building on the foundations laid in the Introduction, this section adopts a contemporary and systematic approach to exploring the interplay of fairness, environmental impact, and behavior dynamics within the contexts of digitalized circular economy, business models, and supply chain management [

18]. This methodology emphasizes recent developments, interdisciplinary perspectives, and the pressing need to address global challenges in sustainability and equity within digital ecosystems [

5,

9].

2.1. Literature Selection and Review

The study undertakes a systematic review of peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, and industry reports from the last decade. Sources were drawn from major academic databases such as Google Scholar, IEEE Xplore, Wiley, and MDPI, using search terms tailored to capture the intersections of the Key Domains and their relevance within the digitalized Key Contexts. The selection criteria prioritized contemporary works that reflect recent advancements and frameworks, ensuring the inclusion of recent research addressing fairness, environmental sustainability, and behavior dynamics in digital ecosystems [

3,

10].

2.2. Contemporary Categorization and Analysis

To align with the principles of contemporary scientific writing, the literature was categorized into thematic clusters that highlight synergies, conflicts, and gaps among the Key Domains within digitalized contexts. This process focused on identifying patterns reflective of current trends, such as the rising emphasis on digital circular economy strategies, equitable resource distribution, and behavioral shifts toward sustainable consumption in digital ecosystems [

6,

14]. These themes informed the development of analytical questions designed to probe deeper into the intersections of the domains.

2.3. Analysis Development

Building on the categorized insights, an analysis was designed to explore the dynamic interactions among the Key Domains within digital ecosystems. This analysis integrates interdisciplinary perspectives to address challenges such as balancing equity with efficiency, reducing environmental impacts, and aligning organizational and consumer behavior with sustainability objectives in digitalized contexts. The analysis’s contemporary design underscores its relevance in addressing both theoretical and practical needs in today’s rapidly evolving digital industrial landscape. By adopting this contemporary approach, the methodology ensures that the survey remains both rigorous and relevant, offering insights that respond to the challenges of modern digitalized industries while paving the way for future interdisciplinary research [

2,

9].

3. Motivation and Challenges

The analysis of modern industrial strategies requires a deep understanding of the theoretical foundations that support key areas of concern. This section explores the core domains of fairness, environmental impact, and behavior dynamics, which are critical for evaluating their interactions within digitalized supply chain management, business models, and the circular economy. By examining these domains through the perspective of established theories and concepts, we can better understand the complexities and challenges that arise when these areas intersect in digital ecosystems. Each domain will be explored in terms of its core concepts and ideas, key challenges, and historical and current perspectives, providing a comprehensive frame of reference for the analysis in

Section 5.

3.1. Fairness

3.1.1. Overview of Fairness

Fairness is a fundamental principle in both ethical and practical decision-making processes, particularly in the context of modern digitalized industries. In digital industrial strategies, fairness involves ensuring that processes, outcomes, and resource distributions are equitable and just [

10,

11,

19]. This concept is particularly critical in areas such as digitalized supply chain management, where decisions about resource allocation, pricing, and access to services can have far-reaching implications [

7,

8]. The relevance of fairness also extends to the development of digitally driven business models and the implementation of circular economy strategies, where ensuring equity among stakeholders is essential for long-term sustainability and social acceptance [

4,

6].

3.1.2. Core Concepts and Ideas in Fairness

At the heart of fairness are several key theories and concepts that provide a foundation for understanding how fairness can be assessed and implemented [

20]. Equity theory, for instance, suggests that individuals assess fairness by comparing their inputs and outcomes relative to others [

16]. Distributive justice focuses on the fairness of outcomes, ensuring that resources are distributed in a way that is perceived as just by all parties involved [

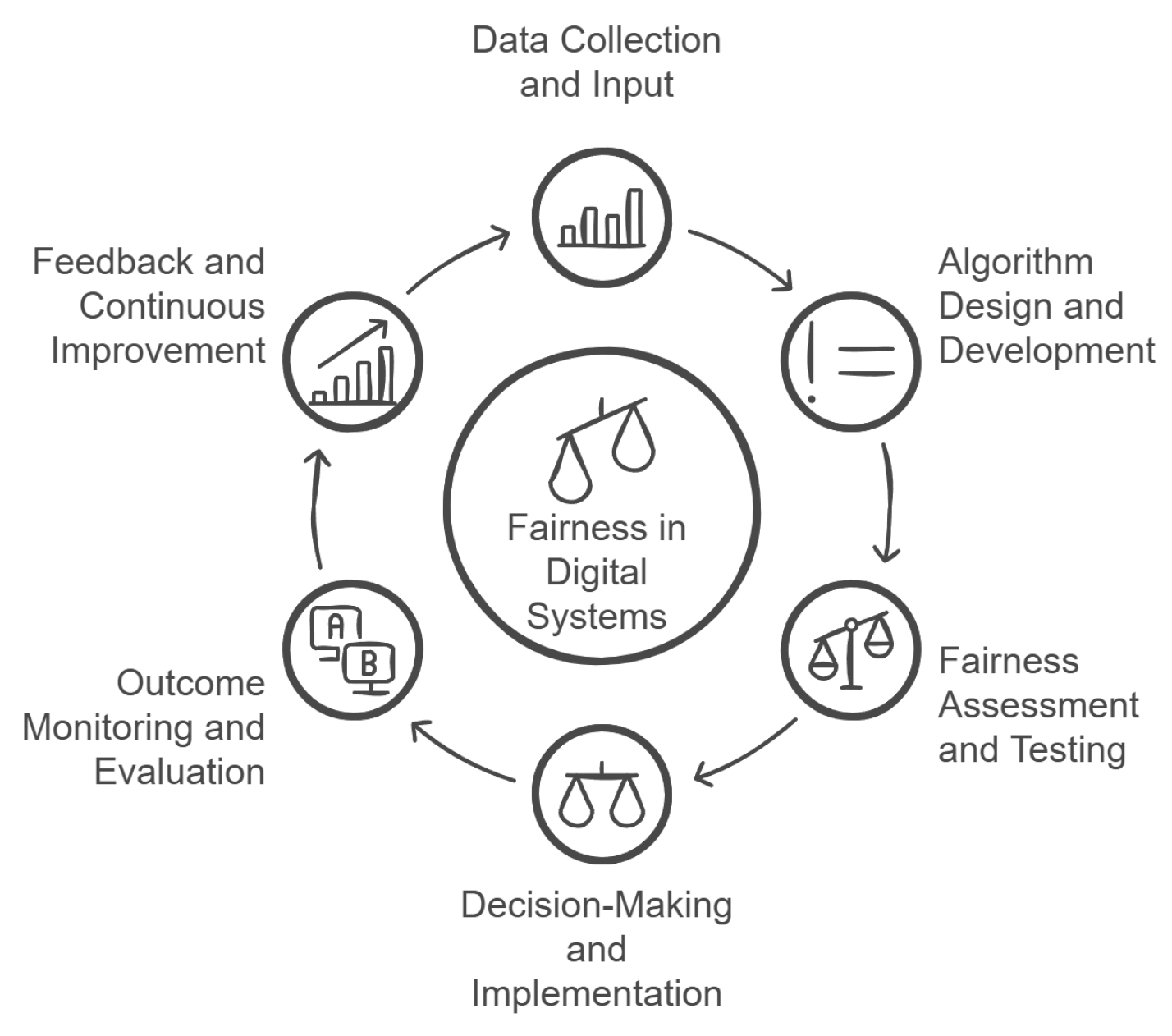

21]. Procedural justice, on the other hand, emphasizes the fairness of the processes that lead to outcomes, highlighting the importance of transparency, consistency, and impartiality in decision-making (

Figure 2) [

10,

22]. These theories are particularly relevant in digitalized contexts, where automated systems are increasingly used to make decisions that impact a wide range of stakeholders [

8,

11].

Figure 2.

Fairness integration cycle in digital systems.

Figure 2.

Fairness integration cycle in digital systems.

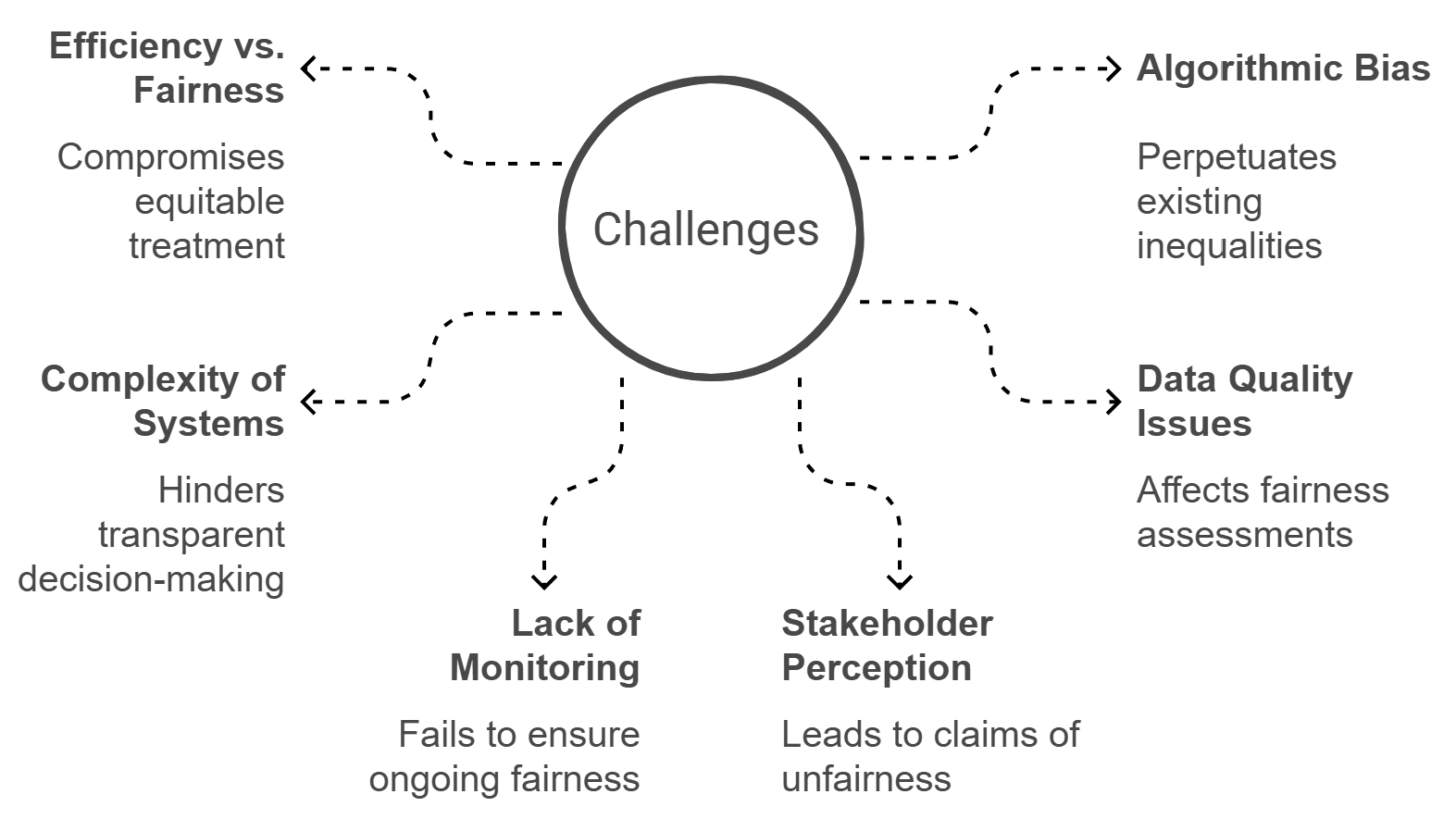

3.1.3. Key Challenges and Considerations in Fairness

Implementing fairness in digitalized industrial contexts presents several challenges (

Figure 3), particularly as industries become more complex and globalized. One of the primary challenges is balancing fairness with efficiency, ensuring equitable treatment while maintaining operational effectiveness, though this can sometimes lead to outcomes perceived as unfair by certain stakeholders [

10,

11]. Another challenge is the potential for bias in digital decision-making processes, such as those driven by algorithms and machine learning, which can unintentionally perpetuate existing inequalities [

5,

23]. Addressing these biases requires careful examination of the data and processes used in decision-making, as well as ongoing monitoring to ensure that fairness is maintained as digital systems evolve [

24,

25].

Figure 3.

Challenges in Implementing Fairness in Digital Industries.

Figure 3.

Challenges in Implementing Fairness in Digital Industries.

3.1.4. Historical and Current Perspectives on Fairness

The concept of fairness has evolved significantly over time, from early theoretical discussions to its application in modern digital and industrial contexts [

4,

5]. Historically, fairness was often associated with legal principles of justice and equity, focusing on ensuring that individuals were treated equally under the law [

20]. In the context of industrial strategies, fairness began to take on new dimensions as businesses sought to balance profitability with social responsibility [

6,

7]. Today, the rise of digital and automated systems has brought new challenges and opportunities for fairness as businesses and regulators work to ensure these systems operate in an efficient and equitable manner [

8,

10]. Current research continues to explore how fairness can be integrated into digital decision-making processes, particularly in dynamic environments such as digitalized supply chain management and the circular economy [

26,

27].

3.2. Environmental Impact

3.2.1. Overview of Environmental Impact

Environmental impact refers to the effect that human activities, particularly industrial and economic activities, have on the natural environment. This concept is central to sustainability efforts, encompassing the various ways in which processes, products, and services contribute to environmental degradation, including pollution, resource depletion, and habitat destruction [

6,

28]. In modern digitalized industrial strategies, minimizing environmental impact is not only a matter of regulatory compliance but also a key component of corporate social responsibility and sustainable development strategies [

4,

7]. The relevance of environmental impact extends to areas such as digitalized supply chain management, where companies must balance efficiency with sustainability, and the design of digitally driven business models and the circular economy, where reducing waste and conserving resources are critical objectives [

8,

29].

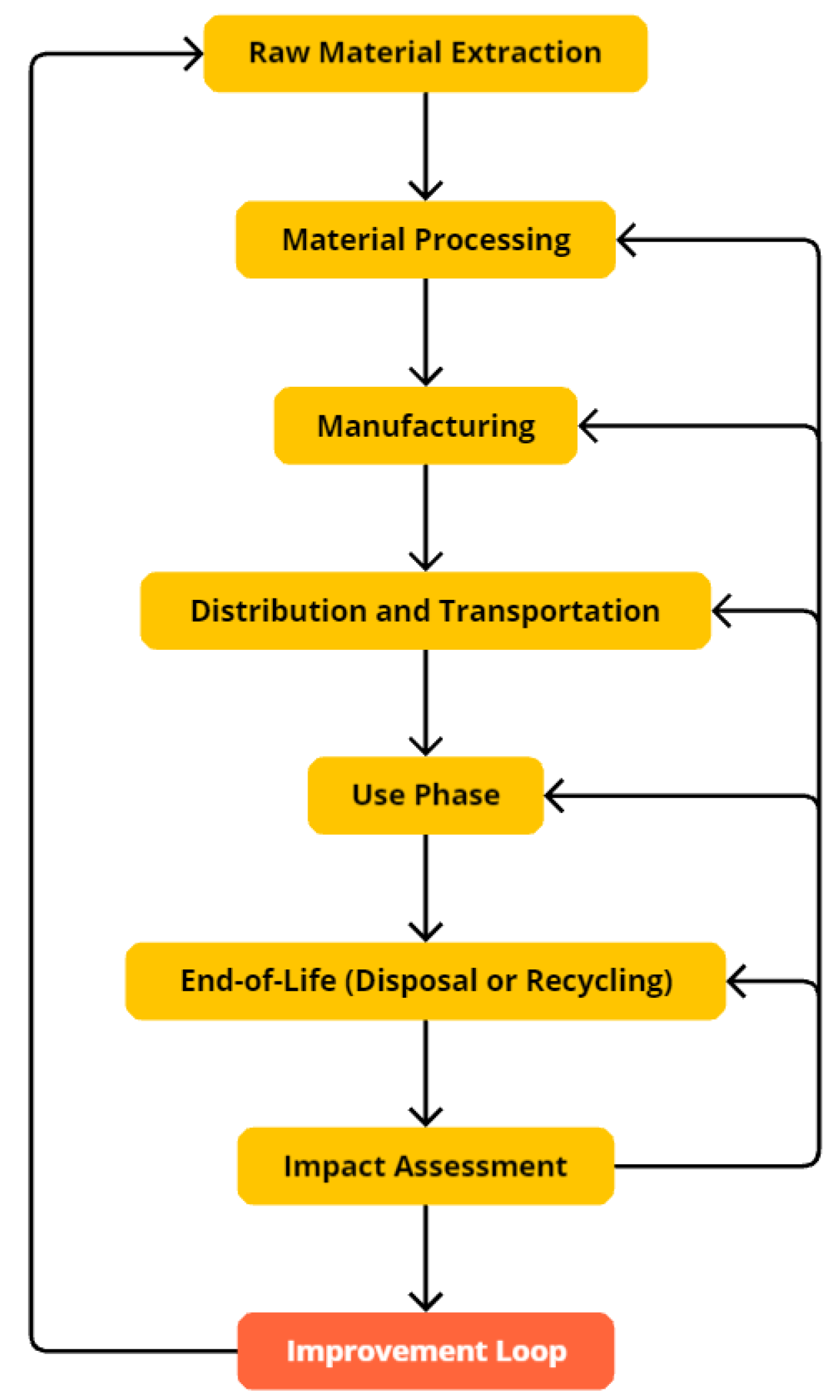

3.2.2. Core Concepts and Ideas in Environmental Impact

Several key concepts and frameworks support the study of environmental impact, with Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) being one of the most important tools. LCA (

Figure 4) is a systematic method for evaluating the environmental aspects and potential impacts associated with a product, process, or service throughout its entire life cycle, from raw material extraction to disposal [

7,

12]. Another significant concept is the Triple Bottom Line (TBL), which expands the traditional reporting framework to include social and environmental performance in addition to financial performance [

30]. Additionally, the Circular Economy (CE) (

Figure 9) model aims to redefine growth by focusing on positive society-wide benefits, decoupling economic activity from the consumption of finite resources, and designing waste out of the system [

6,

7]. These frameworks are increasingly enhanced by digital tools and technologies, which allow for more precise monitoring, analysis, and optimization of environmental strategies [

8,

9]. They are crucial for understanding how businesses can reduce their environmental footprint while maintaining economic viability in digitalized ecosystems [

31].

Figure 4.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) process diagram, showing the progression from raw material acquisition to the end-of-life stage.

Figure 4.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) process diagram, showing the progression from raw material acquisition to the end-of-life stage.

3.2.3. Key Challenges and Considerations in Environmental Impact

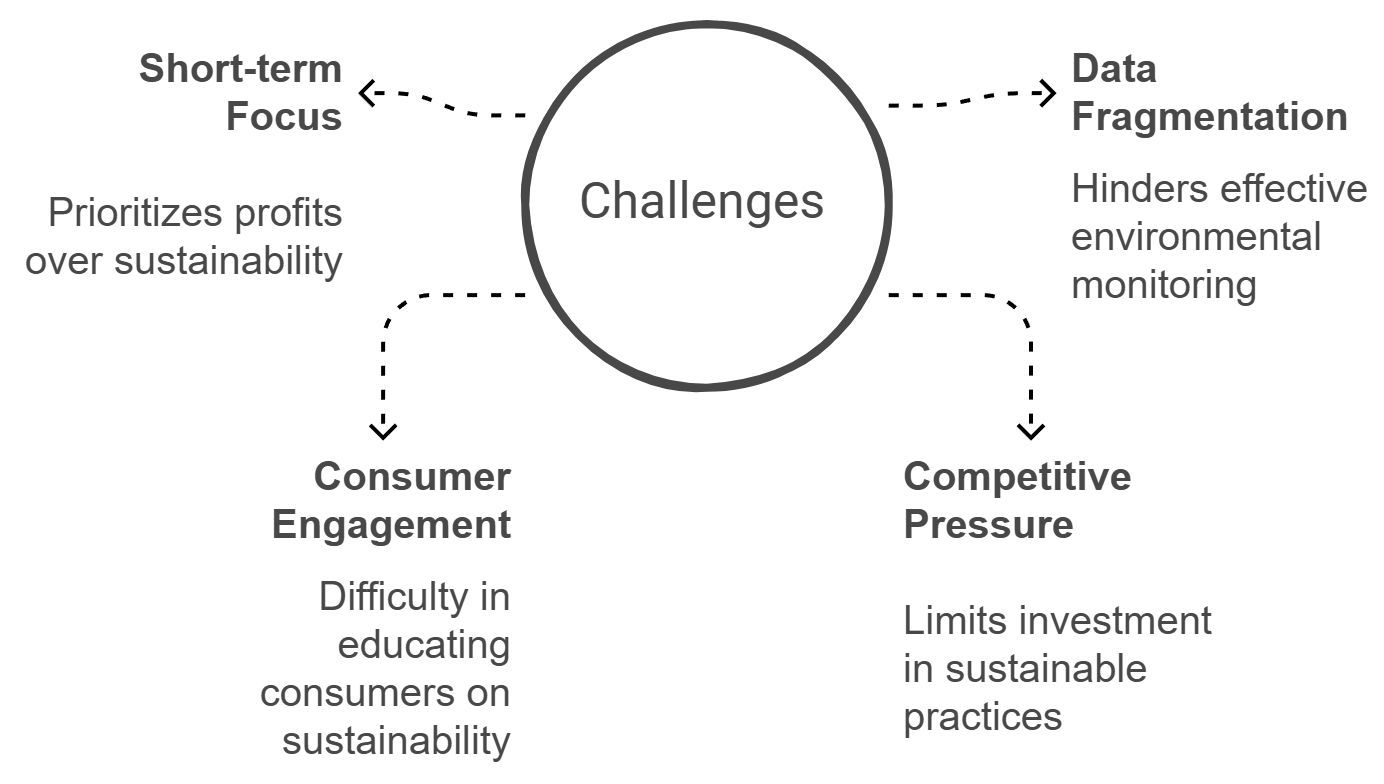

Addressing environmental impact in digitalized industrial contexts presents several challenges (

Figure 5). One of the primary challenges is the integration of sustainability into traditional and digital business models, which often prioritize short-term financial gains over long-term environmental sustainability [

4,

7]. Companies must find ways to align their economic objectives with environmental goals, which can be difficult in competitive markets where cost pressures are high [

6]. Another challenge is the measurement and management of environmental impacts in digitalized global supply chains, where data fragmentation and complexity can hinder effective monitoring and mitigation at every stage of production and distribution [

15,

32]. Additionally, there is the challenge of consumer behavior in digital environments, where businesses must educate and engage consumers on the importance of sustainability. This requires strategies that leverage digital platforms to influence and shift established consumption patterns [

33].

Figure 5.

Challenges in Integrating Environmental Impact in Digital Industries.

Figure 5.

Challenges in Integrating Environmental Impact in Digital Industries.

3.2.4. Historical and Current Perspectives on Environmental Impact

The concept of environmental impact has evolved significantly over time. Initially, environmental concerns were largely oversensitive, focusing on pollution control and remediation. However, with the rise of the environmental movement in the 1960s and 1970s, there was a shift towards more proactive approaches, such as sustainable development and the precautionary principle [

30]. In recent decades, the focus has shifted towards comprehensive strategies like the circular economy, life cycle thinking, and digital environmental monitoring systems, which aim to prevent harm by considering the full environmental impact of products and processes from the outset [

6,

7,

34]. Current perspectives emphasize the need for systemic change, where businesses, governments, and consumers work together to achieve sustainability goals. This includes innovations in green technology, digitalized sustainable supply chain management, and eco-friendly, data-driven business models [

8,

9,

35].

3.3. Behavior Dynamics

3.3.1. Overview of Behavior

Behavior dynamics in industrial and economic contexts refer to the complex interactions and changes in behavior among individuals and groups over time. These dynamics are influenced by various factors, including digital systems, organizational structures, and environmental conditions. Understanding behavior dynamics is critical for optimizing processes, improving decision-making, and ensuring the success of initiatives like sustainability efforts [

14,

36]. In the context of digitalized supply chain management, business models, and the circular economy, behavior dynamics play a significant role in determining how technologies are adopted, how resources are used, and how environmental impacts are managed within digital ecosystems [

7,

37,

38]. Additionally, in the design of digital platforms, such as search engines or e-commerce sites, accurately simulating and predicting the dynamics of user behavior is essential for creating systems that are intuitive, effective, and responsive to user needs [

13,

39]. Effective management of digital behavior dynamics is essential for aligning individual and organizational goals with broader sustainability objectives, ensuring that technological advancements contribute to positive social and environmental outcomes [

40].

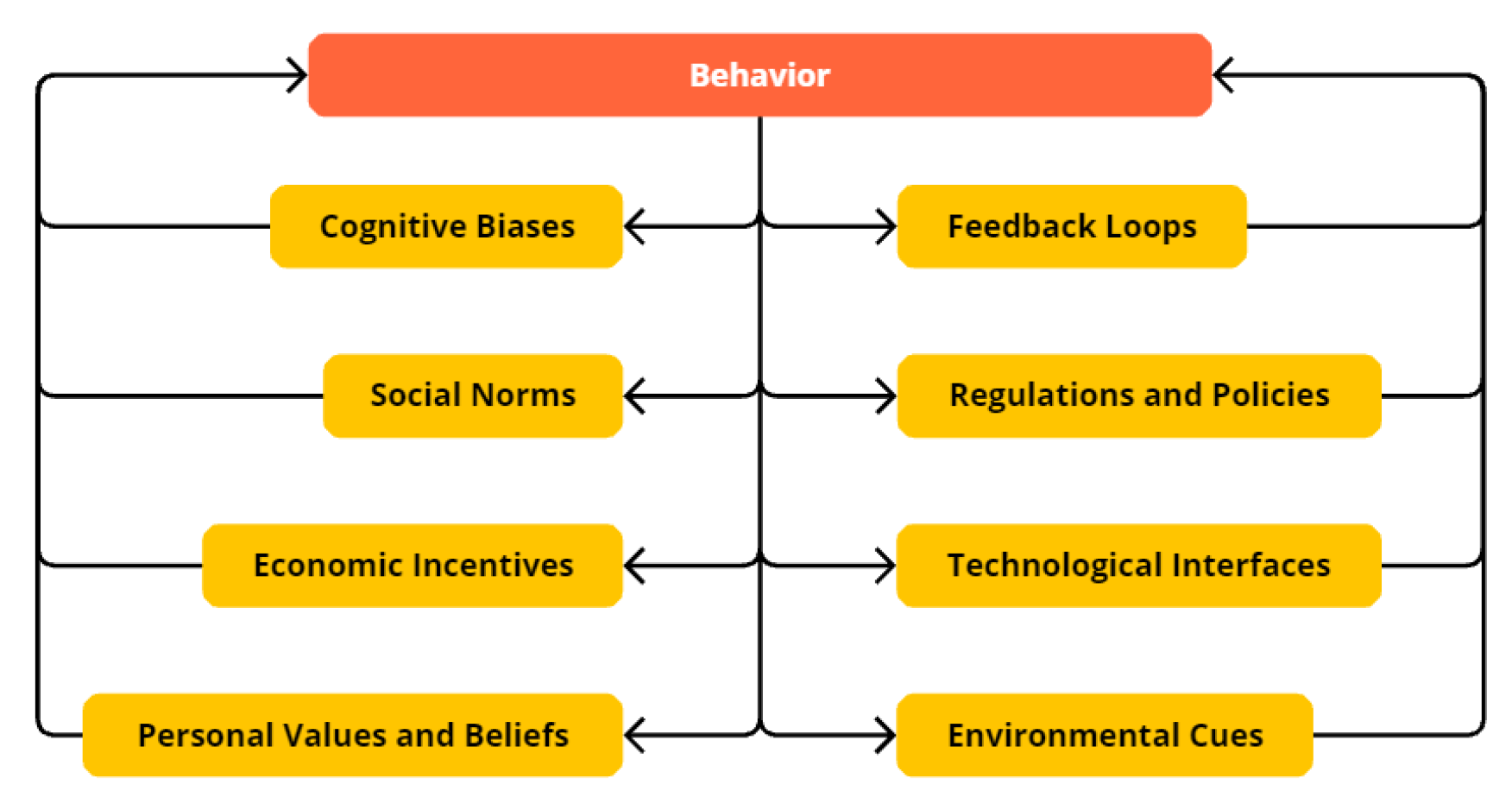

Figure 6.

Behavioral Influence Model, factors that influence individual and group behavior, particularly in the context of industrial decision-making, sustainability, and technology adoption.

Figure 6.

Behavioral Influence Model, factors that influence individual and group behavior, particularly in the context of industrial decision-making, sustainability, and technology adoption.

3.3.2. Core Concepts and Ideas in Behavior

Several key theories and concepts support the study of behavior dynamics in industrial and digitalized contexts. Behavioral Economics remains a crucial field, offering insights into how economic decisions are made and how they evolve in response to changing conditions, explaining why individuals sometimes make irrational decisions that deviate from traditional economic models [

5,

41]. Nudge Theory suggests that subtle changes in how choices are presented can significantly influence behavior without restricting freedom of choice [

14,

42]. Bounded Rationality, introduced by Herbert Simon, describes how individuals make decisions with limited information and cognitive resources, leading to behavior that adapts as conditions change [

16]. Social Norms Theory explores how individuals’ behavior is influenced by the evolving perceptions of what others do and what others think they should do, which is particularly relevant in the adoption and diffusion of sustainable strategies and digital technologies [

43]. In the context of digital platforms, User Behavior Simulation is a critical concept that involves modeling the dynamic interactions between users and systems, taking into account how behavior might change over time in response to different stimuli. This includes understanding click patterns, search behaviors, and decision-making processes to improve user experience and system performance [

13,

44]. These theories are essential for understanding how behavior dynamics are influenced by technological and environmental changes in digitalized industrial contexts. They provide the foundation for designing systems and strategies that align user behavior with broader sustainability and organizational goals.

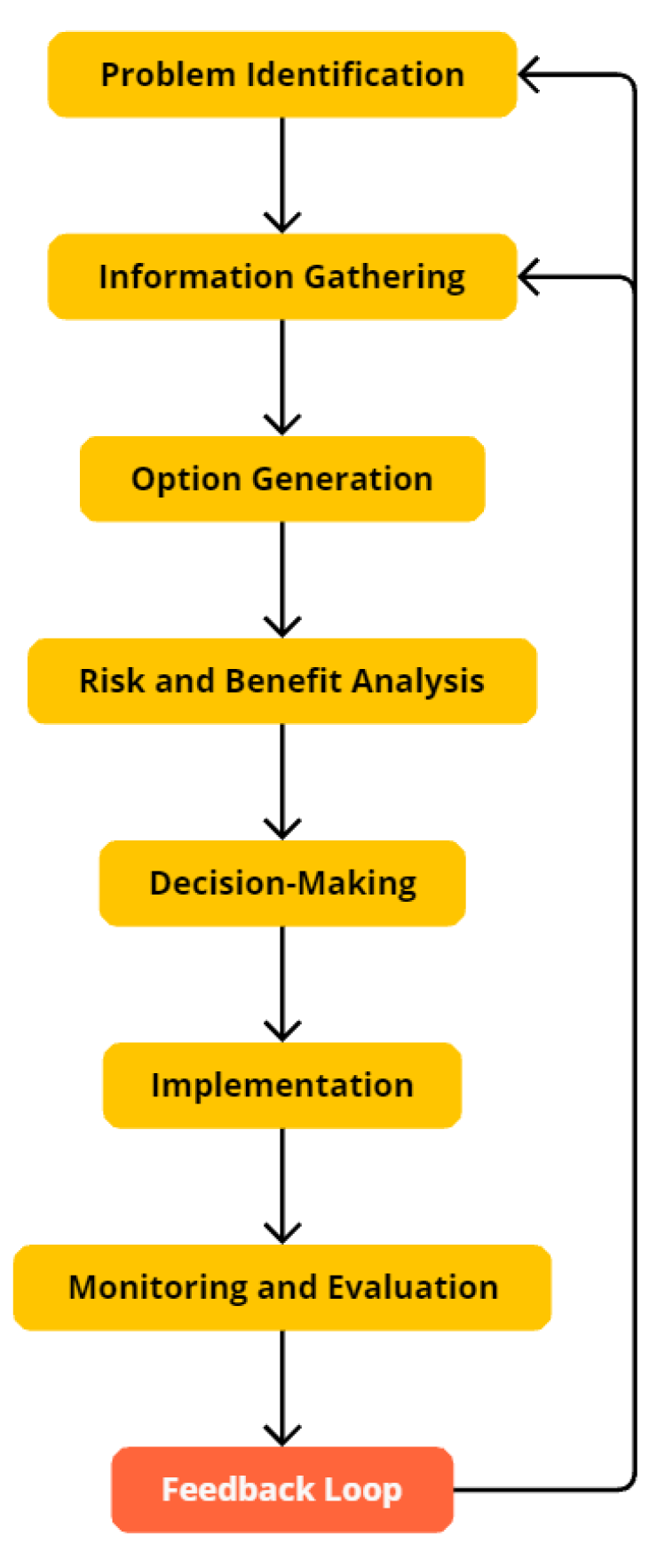

Figure 7.

Decision-Making process diagram, steps involved in making decisions, particularly in the context of industrial and organizational settings, where factors like risk, uncertainty, and competing objectives play significant roles.

Figure 7.

Decision-Making process diagram, steps involved in making decisions, particularly in the context of industrial and organizational settings, where factors like risk, uncertainty, and competing objectives play significant roles.

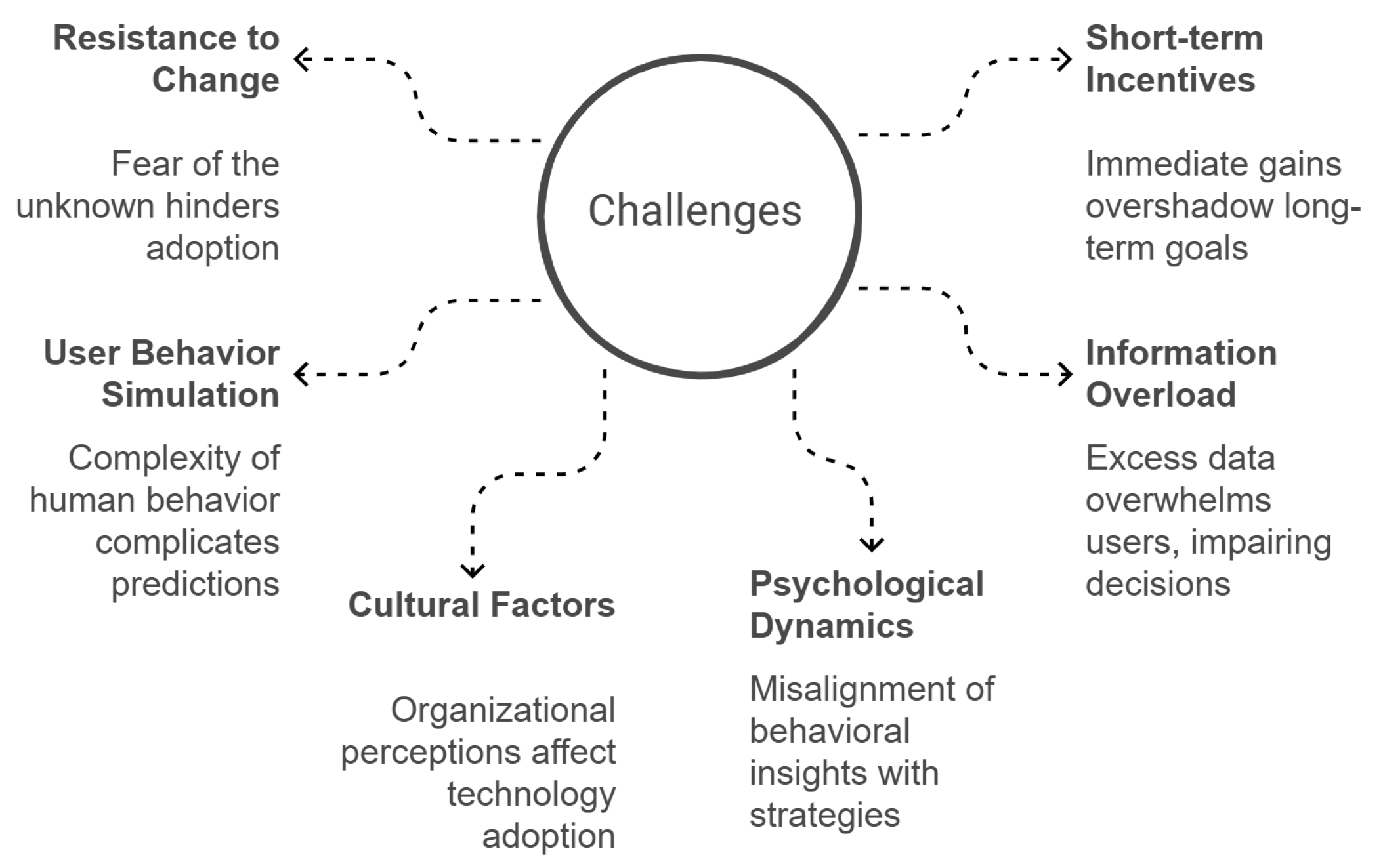

3.3.3. Key Challenges and Considerations in Behavior

Understanding and influencing behavior dynamics in industrial and digitalized settings presents several challenges (

Figure 8). A major challenge is the resistance to change that often accompanies the introduction of new technologies or strategies [

5]. This resistance can stem from factors such as fear of the unknown, perceived loss of control, and comfort with existing routines. Another challenge is the tension between short-term incentives and long-term goals, where individuals and organizations may prioritize immediate gains over long-term sustainability, leading to decisions that are suboptimal from an environmental or social perspective [

37]. In digital platforms, a significant challenge lies in accurately simulating user behavior. While models can predict general patterns, the complexity and variability of human behavior make it difficult to create simulations that account for all possible interactions [

13]. Additionally, information overload in digital environments can overwhelm users, leading to suboptimal decision-making or disengagement [

14]. There is also the challenge of cultural and organizational factors, which play a significant role in shaping behavior and influencing how new strategies and digital technologies are perceived and adopted [

45,

46]. Addressing these challenges requires a deep understanding of psychological, social, and organizational dynamics, as well as strategies for managing change and improving user interaction systems.

Figure 8.

Challenges in Integrating Behavior Dynamics in Digital Industries.

Figure 8.

Challenges in Integrating Behavior Dynamics in Digital Industries.

3.3.4. Historical and Current Perspectives on Behavior

The study of behavior in industrial and digital contexts has evolved significantly over time. Early approaches were influenced by classical economics, which assumed that individuals act rationally to maximize utility. However, the limitations of this model became apparent, leading to the development of behavioral economics, which incorporates psychological insights into economic models [

47]. The introduction of nudge theory in the early 2000s marked a significant shift, highlighting how small, strategic changes could influence long-term behavior dynamics [

48]. More recently, there has been a growing interest in the role of social norms and cultural factors in shaping dynamic behavior, particularly in the context of sustainability and technology adoption [

4]. In digital platforms, understanding the dynamics of user behavior has become critical for optimizing system performance and user experience, acknowledging that behavior is not static but continually evolving [

13,

49]. Current perspectives emphasize the importance of a broad approach to behavior dynamics, integrating insights from psychology, sociology, and economics to develop strategies that are both effective and ethical. This approach is increasingly important as industries navigate the challenges of digital transformation, sustainability, and global competition, where behavior dynamics play a crucial role in determining long-term success within digitalized industrial ecosystems [

50].

Table 1.

Overview of Key Domains in the Theory Section

Table 1.

Overview of Key Domains in the Theory Section

| Key Domain |

Core Concepts and Ideas |

Historical and Current Perspectives |

Key Challenges and Considerations |

| Fairness |

- Equity in resource distribution

- Ethical sourcing and trade strategies |

- Evolved from classical notions of equality

- Focus on social justice in global supply chains |

- Balancing global trade fairness

- Addressing bias in automated decision-making

- Ensuring equitable access to resources |

| Environmental Impact |

- Sustainability

- Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)

- Resource efficiency |

- Shift from environmental protection to sustainability

- Growing focus on circular economy principles |

- Measuring and reducing carbon footprints

- Integrating sustainability into traditional business models

- Managing resource depletion |

| Behavior Dynamics |

- Behavioral economics - Nudge theory

- Decision-making processes |

- Rooted in psychology and economics

- Recent focus on nudging behaviors towards sustainability |

- Understanding consumer resistance to change

- Leveraging behavioral insights in business strategies

- Promoting sustainable behaviors |

4. State of the Art

In the current landscape of industrial research and practice, there is a growing emphasis on understanding how key domains (fairness, environmental impact, and behavior dynamics) intersect and influence each other within critical contexts such as the circular economy, business models, and supply chain management. This interplay is essential for designing sustainable, equitable, and resilient industrial strategies in response to global challenges such as resource scarcity, climate change, and social inequality [

4,

6].

Central to enabling this interplay is the role of digitalization and data sharing, which provide the tools and infrastructure necessary for fostering collaboration, optimizing processes, and enhancing transparency [

8,

51]. Technologies such as blockchain, artificial intelligence (AI), and the Internet of Things (IoT) are among the most prominent enablers, offering capabilities that address key challenges across these domains and contexts:

Blockchain enhances traceability and accountability, supporting ethical practices and fostering trust among stakeholders [

52,

53,

54].

AI provides advanced analytics and predictive insights, enabling resource efficiency and sustainable decision-making [

11,

22].

IoT facilitates real-time monitoring of resource flows, waste streams, and product lifecycles, bridging the gap between physical and digital ecosystems [

55,

56].

While these technologies are transformative, the primary focus of this survey is to examine the interplay between the three domains and contexts, identifying gaps, synergies, and opportunities for innovation. Digital tools are discussed in this context as mechanisms that operationalize and amplify the benefits of this interplay. By framing the analysis around these domains and contexts, this section provides a comprehensive overview of recent advancements, key trends, and ongoing challenges in driving sustainable industrial practices [

9,

57].

4.1. Digitalization and Data Sharing

The rapid advancement of digital technologies and the increasing importance of data sharing have become central to modern industrial ecosystems. These innovations provide the foundation for addressing challenges within fairness, environmental sustainability, and behavior dynamics, enabling collaboration, optimization, and transparency across industries [

58,

59].

4.1.1. Key Frameworks and Initiatives

Digitalization and data sharing are supported by several frameworks and initiatives that align closely with the principles of the circular economy, sustainable business models, and ethical supply chains. Key examples include:

International Data Spaces Association (IDSA) and IDS Reference Architecture Model (IDS RAM): The IDSA provides a globally recognized framework for secure and standardized data exchange across organizations. The IDS RAM serves as a blueprint for implementing trusted data spaces, ensuring interoperability, data sovereignty, and compliance with ethical and legal standards. These elements are particularly relevant for industries transitioning to circular economy practices, as they facilitate the secure sharing of resources and process data [

17,

60].

GAIA-X and Catena-X: GAIA-X is an initiative aimed at building a federated data infrastructure for Europe, promoting data availability while maintaining sovereignty. In parallel, Catena-X focuses on creating a data-driven ecosystem for the automotive industry, integrating supply chain participants to enhance efficiency, traceability, and sustainability. Together, these initiatives demonstrate the role of collaborative platforms in driving digital transformation [

15,

58].

European Union’s Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR) and Digital Product Passports (DPPs): The EU ESPR introduces measures to improve the sustainability of products throughout their lifecycle. Digital Product Passports, a key component of this regulation, provide a digital record of product attributes, enabling stakeholders to track and optimize environmental performance. These tools align closely with the principles of the circular economy by supporting resource efficiency [

6,

61].

Industry-Specific Efforts: Beyond these broad frameworks, industry-specific initiatives play a crucial role in advancing data sharing. For instance, the healthcare sector leverages data spaces to streamline patient care and research, while the manufacturing industry uses real-time data sharing to enhance production efficiency and reduce waste [

9].

4.1.2. Challenges and Opportunities

While these frameworks and initiatives demonstrate the transformative potential of data sharing, challenges remain. Ensuring data security and privacy, managing intellectual property rights, and overcoming organizational resistance to data sharing are critical concerns [

13,

49]. However, the opportunities for innovation, cost reduction, and sustainability make addressing these challenges a worthwhile pursuit.

4.1.3. Scope Clarification

It is essential to distinguish between data sharing and broader concepts such as data collection or industrial automation. This paper focuses on the mechanisms and frameworks enabling data sharing within digital ecosystems. It deliberately excludes broader processes such as digitizing physical operations or collecting data at the source. By narrowing the focus, this discussion underscores the strategic importance of collaboration and interoperability in achieving sustainable industrial strategies [

8,

62].

4.1.4. Integration with Key Contexts

The integration of data-sharing frameworks into circular economy models, business strategies, and supply chain management holds transformative potential. For example:

In the circular economy, data sharing facilitates the tracking of materials across product lifecycles, enabling resource optimization and waste reduction [

59,

63].

In business models, transparent data sharing fosters trust among stakeholders, enhancing collaborative innovation [

17,

56].

In supply chain management, real-time data exchange improves operational efficiency and ensures ethical and sustainable practices [

8,

15].

By aligning these frameworks and technologies with the three key domains, digitalization and data sharing emerge as pivotal drivers for achieving sustainable and equitable industrial practices.

4.2. Circular Economy

The circular economy is a transformative approach to economic activity that emphasizes the reuse, recycling, and sustainable management of resources. Unlike the traditional linear economy model, which follows a "take-make-dispose" model, the circular economy aims to keep resources in use for as long as possible, extracting maximum value and minimizing waste [

6,

64]. This model has gained prominence as industries and governments seek to address environmental challenges and resource scarcity, moving towards a more sustainable and resilient economic system. Within digitalized contexts, the circular economy principles are enhanced by digital tools and technologies that enable efficient resource tracking, data-driven decision-making, and the optimization of recycling and reuse processes [

51,

65,

66].

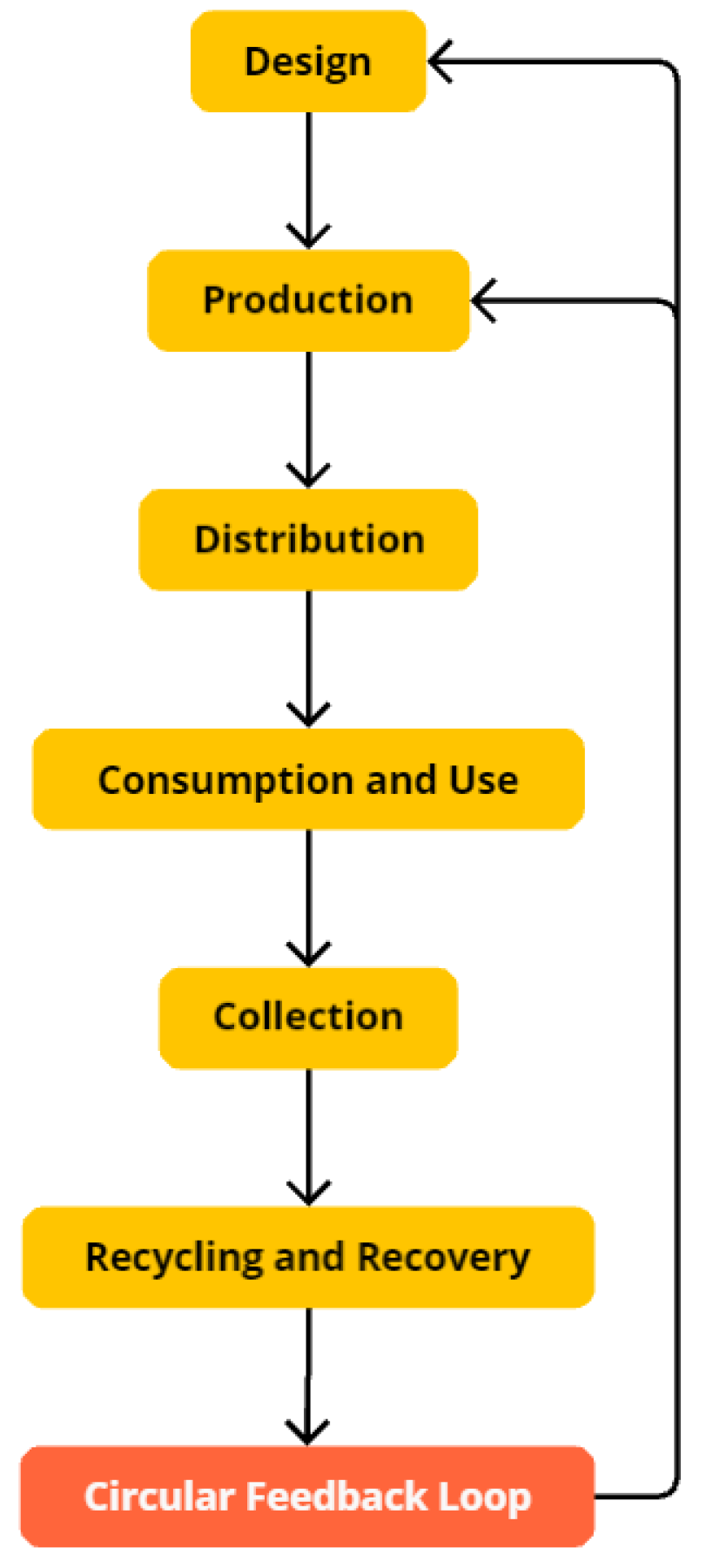

Figure 9.

Circular Economy (CE) closed-loop system, where products, materials, and resources are kept in use for as long as possible, minimizing waste.

Figure 9.

Circular Economy (CE) closed-loop system, where products, materials, and resources are kept in use for as long as possible, minimizing waste.

4.2.1. Fairness in Circular Economy

Fairness in the circular economy involves the equitable distribution of resources, ethical labor practices, and inclusivity across supply chains. As the circular economy grows in importance, its implementation must not worsen existing inequalities but instead promote social equity and inclusion [

4].

In digitalized contexts, technologies such as blockchain, artificial intelligence (AI), and the Internet of Things (IoT) are reshaping how fairness is operationalized, enhancing transparency and accountability [

54,

67]. Blockchain ensures traceability, supporting fair labor practices and ethical sourcing. Studies have shown that blockchain platforms are effective in verifying compliance with ethical standards, fostering trust, and ensuring equitable treatment across supply chains [

23,

31]. Similarly, Digital Product Passports (DPPs), as part of the European Union’s Ecodesign framework, provide lifecycle data that empower informed decisions and promote equitable resource allocation [

68,

69]. AI enhances fairness by optimizing resource allocation and addressing systemic inequities. For example, AI-driven analytics can improve recycling infrastructure placement, ensuring that underserved areas benefit from circular initiatives [

11]. IoT complements these advancements by enabling real-time tracking of resource flows, identifying inefficiencies, and supporting the equitable distribution of resources [

9].

Moreover, recent research emphasizes the importance of fair labor practices in circular supply chains, ensuring that workers involved in recycling and remanufacturing processes are treated equitably [

65,

70]. Addressing systemic inequities is essential to ensuring that circular strategies, such as recycling and resource efficiency, are inclusive of marginalized communities and promote equitable access to resources [

26]. Despite these advancements, further integration of digital tools is required to ensure widespread adoption. Frameworks that combine blockchain, AI, and IoT offer a pathway to align fairness with broader sustainability goals [

33].

4.2.2. Environmental Impact in Circular Economy

Minimizing environmental impact is a core objective of the circular economy. This economic model is designed to reduce waste, minimize resource use, and mitigate environmental degradation by emphasizing strategies such as recycling, remanufacturing, and product life extension. By keeping resources in use for longer and designing products for reuse, the circular economy addresses critical environmental challenges such as pollution, resource depletion, and climate change [

6,

7].

Digital technologies are critical enablers of these goals, facilitating waste reduction, improving resource efficiency, and enhancing lifecycle management. In digitalized contexts, tools such as IoT-based monitoring, blockchain-enabled traceability, and AI-driven predictive analytics significantly enhance the effectiveness of circular strategies by optimizing resource use and improving process efficiency [

8,

9].

AI supports lifecycle assessments (LCAs) by providing precise, real-time data for evaluating environmental footprints [

12]. For instance, Chauhan et al. [

68] demonstrate how AI can identify inefficiencies, optimize recycling, and reduce emissions throughout product lifecycles. LCAs, a key tool in measuring environmental impact, are further enhanced by data-driven insights that enable real-time tracking and analysis of environmental metrics. This allows organizations to pinpoint areas where circular strategies can be most effective, ensuring resource efficiency and waste minimization [

71]. IoT further aids environmental monitoring by tracking material flows and energy use, providing actionable data to ensure resource efficiency and reduce waste. For example, IoT-enabled sensors allow businesses to monitor the lifecycle of products, from production to disposal, enabling more precise resource allocation and minimizing environmental impact [

57]. Blockchain enhances environmental accountability by ensuring transparent reporting on resource use and emissions. For example, Kouhizadeh et al. [

67] emphasize blockchain’s ability to provide immutable records of environmental performance, fostering trust among stakeholders. Blockchain technologies also enable companies to verify sustainable practices across supply chains, supporting broader environmental goals [

54].

Despite the advancements offered by digital tools, challenges remain in scaling their application across industries. The implementation of digital technologies often requires significant upfront investment, while barriers such as data privacy concerns and the digital divide can limit their adoption. Furthermore, industries must navigate the integration of these technologies into existing frameworks to achieve the circular economy’s environmental objectives [

72].

4.2.3. Behavior Dynamics in Circular Economy

Behavior dynamics are critical to the successful implementation of the circular economy, as they influence how consumers, businesses, and governments adopt and engage with circular strategies. Understanding these dynamics is key to promoting sustainable practices such as reuse, recycling, and resource efficiency [

6,

40]. Behavioral economics and psychology offer valuable insights into how to encourage circular behaviors, including the use of incentives for recycling or creating social norms around sustainable consumption. For example, strategies for shifting consumer behavior toward sustainability have been studied in the context of the circular economy, with an emphasis on aligning individual actions with broader environmental goals [

33].

Digital technologies further enhance efforts to shape behavior dynamics. AI-driven personalization tools and gamification platforms can engage consumers more effectively by aligning product offerings with individual values and preferences. For instance, digital tools have been shown to increase recycling and reuse behaviors by making sustainable practices more accessible and rewarding [

13]. Similarly, IoT technologies provide actionable feedback, such as real-time waste reduction insights, encouraging users to adopt circular behaviors in their daily lives [

73]. AI and blockchain technologies also play a significant role in informing ethical decision-making within the circular economy. For example, blockchain ensures transparency and fosters trust by providing immutable records, while AI optimizes resource allocation to meet consumer demands for sustainable products [

67].

The transition to a circular economy requires significant changes at multiple levels, from individual consumers to entire organizations and industries. Recent research emphasizes the need for systemic behavioral shifts, highlighting the role of digital ecosystems in driving these changes [

3,

51]. For example, digital platforms leveraging behavioral data can predict and influence adoption patterns, aligning business strategies with consumer preferences to facilitate sustainable practices [

72]. Although significant progress has been made in understanding and shaping behavior dynamics, further research is needed to explore how digital tools can drive systemic behavioral changes, particularly at organizational and policy levels. Addressing barriers such as digital access and consumer trust is essential for ensuring widespread adoption of circular economy practices and achieving long-term sustainability goals [

74].

4.2.4. Intersections and Emerging Themes

The circular economy is deeply interconnected with fairness, environmental sustainability, and behavior dynamics, forming a framework where these domains reinforce one another. Recent research highlights that achieving environmental goals within circular systems is inseparable from ensuring equitable resource distribution and fostering widespread behavioral engagement [

6,

75]. The alignment of fairness with environmental sustainability is evident in initiatives that aim to make resource recovery systems and recycling programs accessible to all stakeholders. Blockchain-enabled traceability and lifecycle data tools enhance transparency and accountability, ensuring that circular strategies effectively address social inequities while reducing environmental impact [

67,

68]. For example, inclusive infrastructure initiatives supported by digital technologies promote equitable resource access, benefiting communities most affected by environmental degradation [

4].

Behavior dynamics further shape the success of circular strategies. Effective recycling, reuse, and sustainable consumption hinge on behavioral incentives that align individual actions with environmental priorities. Research underscores the importance of behavior in determining the environmental outcomes of circular strategies, with tools like gamification platforms and AI-driven analytics showing promise in promoting sustainable practices at scale [

13,

14]. These tools not only encourage circular behaviors but also address accessibility challenges, though ensuring fair access to digital platforms remains an ongoing issue [

9].

Emerging research calls for an integrated approach that embeds fairness, environmental sustainability, and behavior dynamics into circular systems. This approach must address gaps in accessibility, policy alignment, and stakeholder collaboration to ensure that the circular economy achieves its full potential. Digital transformation plays a pivotal role in enabling this integration, offering tools to create systems that are not only environmentally sustainable but also socially equitable and behaviorally viable [

3]. By aligning fairness with environmental sustainability and leveraging behavioral insights, the circular economy can evolve into a comprehensive system capable of addressing the complex challenges of the 21st century. A collaborative, multi-stakeholder approach is essential to fostering inclusivity, ensuring that marginalized groups benefit from circular initiatives, and creating lasting impact [

31,

72].

4.3. Business Models

Business models serve as the strategic frameworks through which organizations create, deliver, and capture value. Unlike the circular economy, which focuses on systemic approaches to resource optimization, and supply chain management, which emphasizes operational logistics, business models define how organizations align their strategies with stakeholder needs and market demands[

76]. In the context of this survey, business models are examined as distinct yet interconnected with the circular economy and supply chain management. They serve as mechanisms to operationalize circular strategies and leverage supply chain processes to achieve sustainable and equitable outcomes. By integrating fairness, environmental sustainability, and behavior dynamics, business models become tools for driving innovation and addressing global challenges. Recent research emphasizes the importance of sustainable business models that prioritize environmental and social outcomes alongside financial performance, highlighting their role in fostering long-term value creation for both businesses and society [

77,

78].

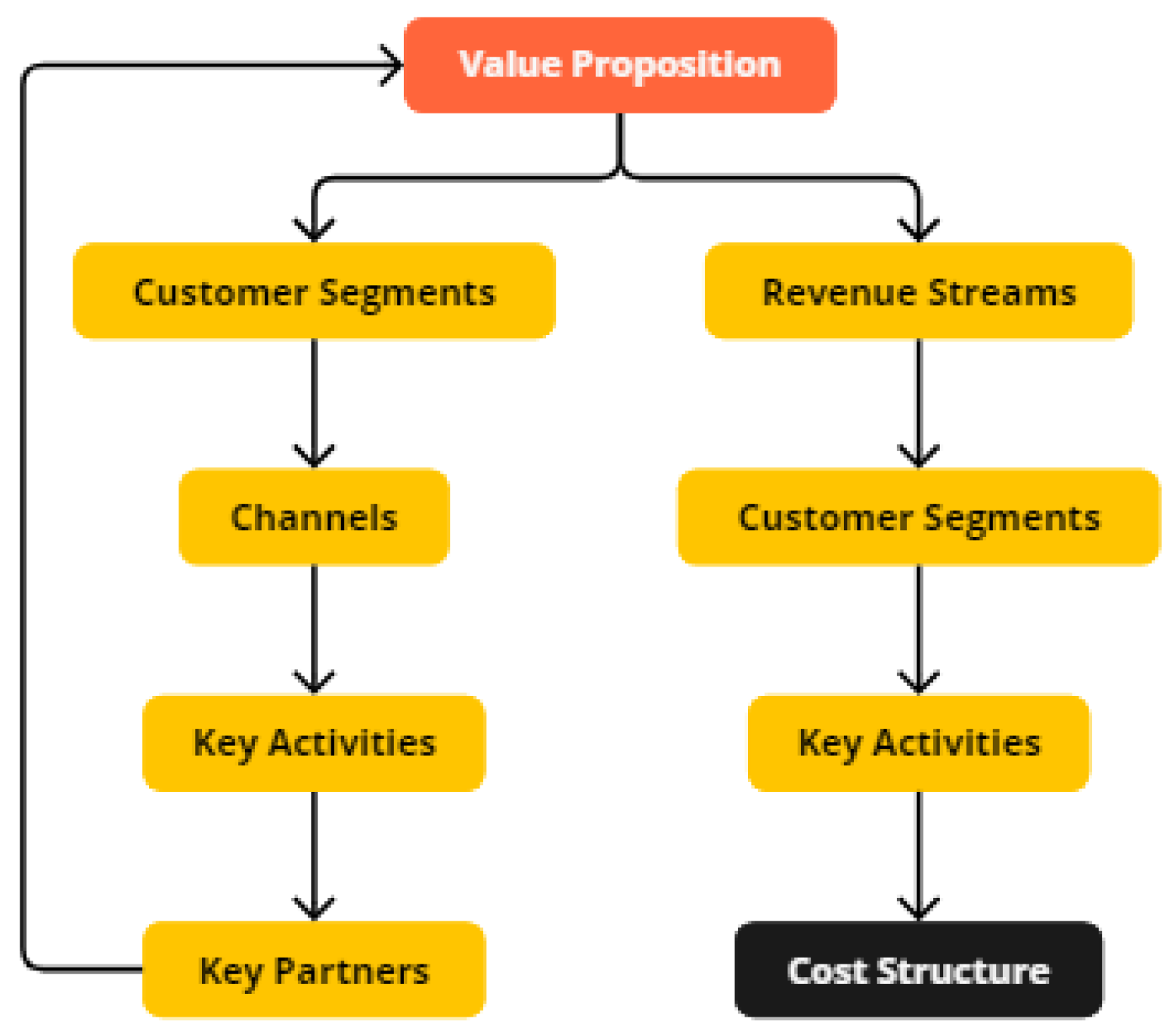

Figure 10.

Business Models process diagram, demonstrate the influence of each component of a business model, driving innovation and long-term success.

Figure 10.

Business Models process diagram, demonstrate the influence of each component of a business model, driving innovation and long-term success.

4.3.1. Fairness in Business Models

Fairness in business models ensures the equitable distribution of value among stakeholders, including workers, suppliers, customers, and marginalized communities. This involves addressing issues such as fair pricing, equitable profit distribution, ethical sourcing, and inclusive innovation. By embedding fairness into their strategies, organizations enhance consumer trust, foster stakeholder collaboration, and create long-term value that benefits diverse communities [

4].

In digitalized contexts, blockchain technology plays a pivotal role in fostering fairness by enhancing transparency and trust. Recent studies demonstrate how blockchain platforms enable businesses to verify ethical sourcing and labor practices, ensuring accountability across value chains [

54]. Blockchain also supports fair pricing mechanisms, enabling equitable compensation for all participants while promoting trust among stakeholders [

67]. AI contributes to fairness by identifying inequities in resource allocation and optimizing business strategies to promote inclusivity. For instance, AI-driven analytics can detect disparities in supply chain networks, allowing businesses to redirect resources or adjust operations to address imbalances [

10]. Similarly, real-time data analytics provide actionable insights, supporting fair treatment across the value chain and fostering inclusivity in decision-making processes [

21].

The growing demand for corporate social responsibility (CSR) and ethical business strategies has driven companies to re-evaluate their business models to incorporate fairness at every level. Research emphasizes the importance of fairness in industries with significant power imbalances between stakeholders, highlighting the role of inclusive innovation in creating equitable access to goods and services [

7]. Through digital ecosystems and tools such as platform-based business models, AI frameworks, and blockchain-enabled transparency, organizations can advance fairness while achieving sustainability and inclusivity goals [

9].

4.3.2. Environmental Impact in Business Models

Minimizing environmental impact has become a critical focus in modern business models as organizations strive to align profitability with sustainability. Companies face growing pressure to reduce their ecological footprint and contribute to global sustainability goals, prompting the adoption of strategies such as resource efficiency, waste reduction, and the integration of renewable energy sources [

7,

34].

Digital tools play a transformative role in enabling these strategies. IoT-based monitoring systems and AI-driven lifecycle assessments (LCAs) provide real-time insights into resource use, energy consumption, and waste generation. These tools allow businesses to optimize operations, identify inefficiencies, and reduce emissions while maintaining economic competitiveness [

68]. Predictive analytics and real-time environmental monitoring further enhance the ability of businesses to make data-driven decisions that minimize their environmental impact [

9].

The circular economy has emerged as a particularly effective model for reducing environmental impact by extending the lifecycle of resources and products. Recent research underscores the integration of circular principles into business models as a pathway to sustainability. For instance, frameworks for sustainable business model archetypes demonstrate how organizations can adopt circular strategies, such as designing for durability, enabling product reuse, and prioritizing resource efficiency, to achieve significant environmental benefits [

78]. When combined with digital innovations, these sustainable business model archetypes offer organizations a means to enhance environmental performance without compromising competitiveness. By embedding circular economy principles into their strategies and leveraging digital tools, companies can create business models that not only minimize environmental impact but also drive long-term value creation and resilience in a changing global landscape [

29,

79].

4.3.3. Behavior Dynamics in Business Models

Behavioral dynamics shape how organizations align their strategies with sustainability goals, influencing both internal decision-making and consumer engagement. By leveraging behavioral insights, businesses can adapt their operations, develop innovative models, and respond to evolving market demands. AI-driven tools, such as behavioral analytics and personalization algorithms, enable companies to analyze consumer preferences and design products or services that align with sustainability values, fostering deeper engagement and promoting long-term customer relationships [

9].

Unlike the societal-scale behaviors discussed in the circular economy, business models emphasize the role of internal organizational behavior. Cultural shifts and operational adjustments are often necessary to implement sustainability-focused strategies effectively. Research highlights that organizations embedding behavioral insights into internal processes, such as adopting nudge-based approaches or fostering sustainable workplace cultures, are more likely to succeed in scaling circular practices [

7]. For example, predictive analytics and data-driven simulations enable companies to anticipate and influence behavioral trends with greater precision, ensuring alignment with sustainability objectives [

46].

Digital platforms further enhance engagement by enabling businesses to track and respond to consumer behavior in real-time. These platforms often incorporate incentive mechanisms, such as subscription models, take-back programs, or gamification strategies, to encourage consumer participation in circular practices [

13,

42]. Such strategies demonstrate how behavioral dynamics drive both consumer and organizational alignment with sustainability goals, operationalizing circular principles through business models. Understanding behavior dynamics within organizations is also key to successfully implementing new business models, particularly those requiring significant cultural or operational changes. Businesses that integrate these insights into their strategies not only foster deeper connections with stakeholders but also drive innovation and resilience in dynamic markets [

37,

39].

4.3.4. Intersections and Emerging Themes

Business models integrate fairness, environmental sustainability, and behavior dynamics, creating opportunities to align profitability with global sustainability goals. These interconnected domains foster innovation and drive inclusive, environmentally responsible strategies [

78]. The connection between fairness and environmental sustainability is evident in business practices that prioritize ethical value chains while reducing ecological footprints. Blockchain and AI technologies enhance these efforts by improving transparency and equitable resource distribution, ensuring sustainable outcomes benefit all stakeholders [

79].

Behavior dynamics further influence the effectiveness of business models by shaping consumer and organizational engagement. AI-driven personalization and incentive mechanisms have demonstrated their potential to promote sustainable behaviors, such as participation in circular initiatives [

13,

68]. For example, digital platforms that gamify recycling or reward sustainable consumption create stronger consumer engagement while advancing environmental objectives. However, these strategies must adapt to diverse markets and industries to maximize their impact and inclusivity [

9,

80].

Emerging research emphasizes the transformative potential of business models that fully integrate these domains. Companies that embed environmental and social considerations into their strategies not only enhance resilience but also build stronger relationships with customers, employees, and stakeholders [

81]. Digital technologies, such as predictive analytics and real-time monitoring systems, enable businesses to adapt to evolving consumer demands and sustainability goals more effectively. By leveraging these tools, organizations can create frameworks that are not only economically viable but also socially equitable and environmentally sustainable [

4].

The integration of these domains highlights the potential of inclusive innovation, where new business models ensure benefits for a wide range of stakeholders, including those traditionally underserved. Through such frameworks, businesses can align profitability with sustainability, achieving long-term value creation that addresses the complex challenges of the modern economy [

82].

4.4. Supply Chain Management

Supply chain management (SCM) is a critical area of study and practice, encompassing the planning, execution, and oversight of the flow of goods, services, and information from raw material suppliers to end consumers. The complexity of global supply chains, coupled with the need for efficiency, transparency, and sustainability, makes SCM a vital context in which to explore the intersections of key domains such as fairness, environmental impact, and behavior dynamics [

9].

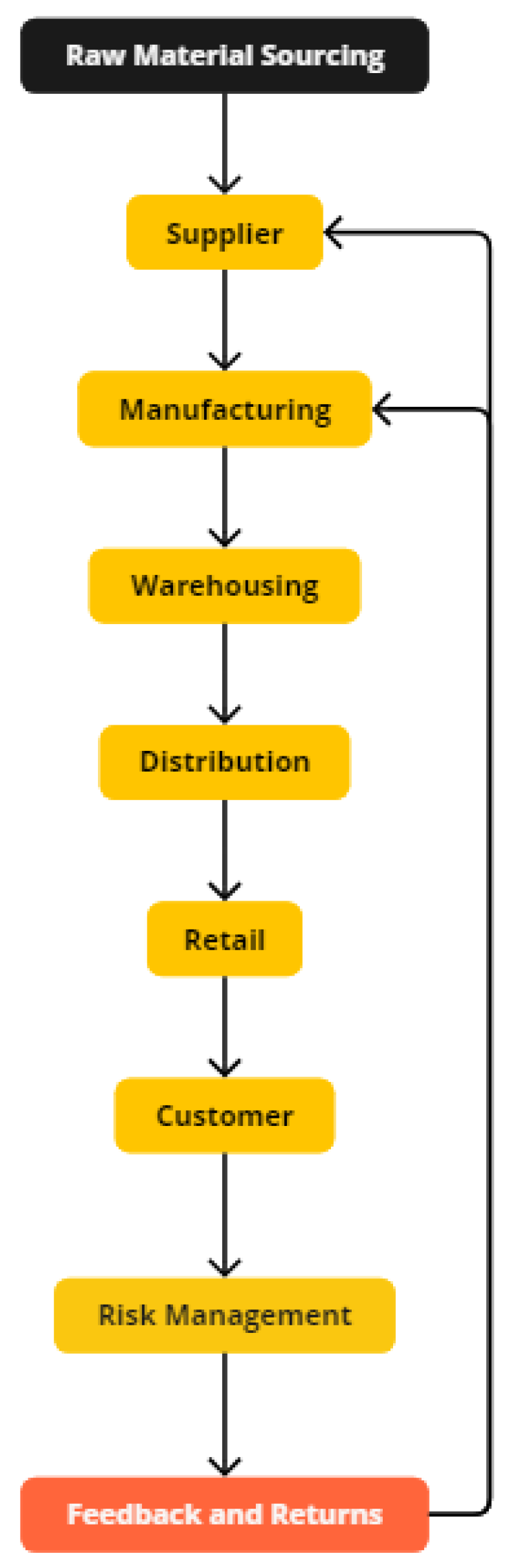

Figure 11.

Supply Chain Management process diagram (SCM) highlights the interconnections between different stages of the supply chain.

Figure 11.

Supply Chain Management process diagram (SCM) highlights the interconnections between different stages of the supply chain.

4.4.1. Fairness in Supply Chain Management

Fairness in supply chain management ensures the equitable treatment of all stakeholders, including workers, suppliers, and communities. It addresses critical issues such as fair labor strategies, equitable resource distribution, and ethical sourcing of materials. As supply chains grow increasingly global and complex, ensuring fairness across all levels has become a critical concern, particularly in industries with extensive outsourcing and supply networks [

31,

83].

Digital technologies play a pivotal role in fostering fairness. Blockchain technology enhances transparency and accountability by enabling traceability in sourcing and labor practices. Recent studies demonstrate how blockchain-enabled traceability improves ethical sourcing and ensures fair labor conditions across global supply chains, supporting fair treatment for small suppliers and vulnerable workers [

54,

67]. Smart contracts further enhance fairness by automating compliance with ethical standards, reducing opportunities for exploitation, and fostering trust among stakeholders [

84]. AI-driven analytics also support fairness by identifying inequities in resource allocation and optimizing supplier relationships to promote inclusivity. These technologies ensure that sustainable supply chain practices are accessible to all stakeholders, addressing systemic disparities that have traditionally marginalized smaller suppliers and workers in vulnerable conditions [

68,

85].

Recent research emphasizes the need for frameworks and tools to assess and ensure fairness in supply chains. By integrating ethical considerations into supply chain contracts, negotiations, and resource allocation models, organizations can create pathways for more equitable and sustainable supply chain strategies [

86].

4.4.2. Environmental Impact on Supply Chain Management

Environmental sustainability is a core objective of modern supply chain management (SCM), driven by the urgent need to reduce emissions, waste, and resource consumption. Environmental impact in SCM encompasses assessing and managing the ecological consequences of activities such as production, transportation, and disposal, highlighting the shift toward green supply chain management (GSCM) [

87,

88].

Digital technologies, particularly IoT-enabled monitoring systems and AI-powered optimization tools, play a transformative role in minimizing environmental footprints. These tools provide real-time data and predictive analytics, allowing companies to identify inefficiencies in logistics and transportation, significantly reducing carbon emissions and resource use [

67,

84]. For instance, IoT technologies enable precise tracking of energy consumption and waste generation across supply chain stages, while AI-driven analytics optimize routes and inventory management to reduce environmental impact [

65].

The research underscores the importance of adopting green supply chain practices such as closed-loop logistics, lifecycle assessments (LCAs), and green transportation strategies. LCAs, in particular, allow organizations to identify and mitigate critical environmental areas, providing a comprehensive framework for improving sustainability throughout the supply chain [

31,

89]. These strategies not only reduce ecological footprints but also enhance supply chain resilience by addressing resource scarcity and regulatory challenges. Integrating circular principles into SCM further enhances environmental outcomes by extending the lifecycle of materials and products. Circular strategies, such as reuse, remanufacturing, and recycling, reduce waste while creating more efficient and sustainable supply chains. Studies show that these approaches when supported by digital platforms for real-time data analysis and predictive modeling, enable actionable insights to optimize supply chain activities and meet long-term sustainability goals [

32].

4.4.3. Behavioral Dynamics in Supply Chain Management

Behavior dynamics play a crucial role in supply chain management (SCM) by influencing decision-making, collaboration, and compliance across the supply chain network. Understanding how human behavior interacts with technological systems and organizational processes is critical for optimizing supply chain performance and aligning with sustainability objectives [

5].

Digital tools, such as AI-powered behavioral analytics and gamification platforms, enable organizations to align stakeholder behaviors with circular supply chain models. For instance, incentivizing suppliers to adopt greener practices or encouraging consumers to participate in reverse logistics systems has proven effective in advancing circular strategies [

16]. Predictive analytics and real-time feedback systems provide deeper insights into these dynamics, promoting alignment with sustainability goals by modeling and responding to behavioral trends effectively.

Organizational behavior also significantly impacts the adoption of sustainable supply chain practices. Research highlights the importance of fostering a culture of collaboration and innovation within organizations to overcome resistance to change and promote sustainability-focused strategies [

26]. By addressing decision-making biases and encouraging proactive engagement with sustainability initiatives, businesses can enhance resilience and adaptability within their supply chains [

27]. These behavioral insights are particularly relevant in digitalized SCM, where technologies support the dynamic interactions between suppliers, consumers, and organizational systems. For example, real-time behavioral analytics allow businesses to anticipate risks, improve collaboration, and ensure compliance with sustainable practices across the supply chain [

13]. By leveraging behavioral insights and digital technologies, organizations can align stakeholder actions with sustainability goals, ensuring long-term success in achieving both economic and environmental objectives.

4.4.4. Intersections and Emerging Themes

Supply chain management (SCM) integrates fairness, environmental sustainability, and behavior dynamics to create systems that are efficient, ethical, and resilient. The interplay between fairness and environmental sustainability is evident in initiatives that prioritize equitable resource distribution while minimizing environmental impacts. For instance, blockchain and IoT technologies play a vital role in ensuring transparency and accountability across these interconnected domains, fostering trust and collaboration among stakeholders [

55,

71].

Behavior dynamics further influence the success of sustainable SCM by fostering collaboration and compliance among stakeholders. Behavioral changes are essential for driving the adoption of green strategies, such as closed-loop logistics or resource-efficient practices. Incentives and digital tools, such as AI-driven decision-making systems and gamification platforms, align stakeholder behaviors with broader sustainability goals, ensuring the widespread adoption of sustainable practices across supply chain networks [

13,

84].

Emerging research emphasizes the need for greater integration of digital tools and collaborative frameworks to address accessibility challenges and enhance stakeholder alignment. Ethical AI and real-time analytics are increasingly important in adapting supply chain practices to meet both environmental and social challenges [

67]. Additionally, the adoption of circular supply chain models demonstrates how environmental sustainability can be integrated with economic efficiency, offering scalable solutions that are both sustainable and resilient [

4]. By embedding fairness, environmental sustainability, and behavior dynamics into SCM, industries can develop systems that are adaptable to changing global demands and better equipped to address the complexities of modern supply chains. These integrated approaches, supported by digital technologies, provide a pathway to ensuring long-term economic viability while promoting social and environmental responsibility [

7,

90].

Table 2.

Comparison of Studies Across Key Domains and Contexts

Table 2.

Comparison of Studies Across Key Domains and Contexts

| Paper/Study |

SCM |

Business Models |

Circular Economy |

Fairness |

Env. Impact |

Behavior Dynamics |

| Velenturf & Purnell [4] |

|

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

| Ali et al. [10] |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

| Jesse & Jannach [13] |

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

| Ghobakhloo [9] |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

| Voukkali et al. [31] |

|

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

| Mehrabi et al. [5] |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

| Reike et al. [6] |

|

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

| White et al. [14] |

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

| Geissdoerfer et al. [7] |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

| Booth et al. [21] |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

| Legros & Cislaghi [36] |

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

| Bhutta et al. [35] |

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

| Rosa et al. [82] |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

| Sarkis et al. [8] |

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

| Kouhizadeh et al. [67] |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

| Kraus et al . [94] |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

| Biswas et al. [15] |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

5. Analysis and Practical Applications

In this section, we will focus on examining the practical applications, challenges, successes, and future prospects of the key domains within the key contexts. Additionally, we will identify gaps in current research and suggest areas where further study is needed.

5.1. Circular Economy

5.1.1. Integration of Key Domains

Fairness plays a critical role in the circular economy by ensuring that the benefits of strategies such as recycling, remanufacturing, and resource efficiency are equitably distributed among all stakeholders. This includes addressing social equity by providing fair access to resources and opportunities, particularly for marginalized communities that are often disproportionately affected by environmental degradation. Fair division approaches, as discussed in sustainability and biodiversity impact studies, provide valuable insights into equitable resource distribution [

21,

82].

The primary objective of the circular economy is to minimize environmental impact by maintaining resources in use for as long as possible, reducing waste, and designing products with longer lifecycles. Strategies such as recycling, remanufacturing, and designing for end-of-life recovery aim to create closed-loop systems that reduce raw material extraction and waste generation, ultimately mitigating the environmental footprint of industrial activities. This aligns with principles of sustainability and resource conservation [

4,

70].

Understanding behavior dynamics is essential for the successful adoption and implementation of circular economy initiatives. Consumer, organizational, and governmental behaviors evolve and interact in response to these initiatives, requiring strategies that promote sustainable practices. Encouraging behaviors such as recycling, reducing consumption, and purchasing sustainable products necessitates targeted interventions that address the complexity of behavior dynamics and social norms [

14,

64].

Table 3.

Matrix of Key Domain Impacts on Circular Economy Elements

Table 3.

Matrix of Key Domain Impacts on Circular Economy Elements

| Element |

Fairness |

Environmental Impact |

Behavior Dynamics |

| Resource Use |

Equitable Access to Resources |

Minimizing Resource Depletion |

Encouraging Sustainable Consumption |

| Product Lifecycle |

Fair Labor strategies in Manufacturing |

Design for Longevity and Recyclability |

Promoting Product Returns for Recycling |

| Waste Management |

Socially Responsible Waste Disposal |

Waste Reduction and Reuse Strategies |

Behavioral Incentives for Waste Reduction |

| Economic Models |

Inclusive Economic Participation |

Circular Business Models |

Consumer Engagement in Circular Initiatives |

| Policy and Governance |

Fair Policy Frameworks |

Environmental Regulations |

Public Awareness and Education |

5.1.2. Challenges

Scaling Circular strategies: One of the primary challenges in the circular economy is scaling circular strategies across industries and geographies. Implementing circular models often requires significant upfront investment in infrastructure, technology, and education, which can be a barrier for many companies, especially smaller ones [

33,

34,

91].

Ensuring Social Equity: Ensuring that the circular economy is fair and inclusive is a significant challenge. Often, the benefits of circular strategies are not equitably distributed, with marginalized communities either being excluded from these benefits or disproportionately bearing the negative impacts of circular initiatives (e.g., e-waste recycling) [

21,

31,

65].

Behavioral Resistance: Changing consumer and organizational behaviors to support the circular economy is challenging. Consumers may resist circular strategies due to a lack of awareness, convenience, or perceived cost barriers. Similarly, businesses may be slow to adopt circular models due to concerns about profitability or operational complexity. Effective strategies are needed to influence behavior dynamics at all levels to support the transition to a circular economy [

14,

36,

82].

5.1.3. Case of Successful Application

One notable example of the successful application of circular economy principles is the remanufacturing processes implemented in the automotive industry. Companies have increasingly embraced closed-loop production models where used vehicle components are collected, refurbished, and reintegrated into the market as high-quality alternatives to new parts. This approach significantly reduces waste, conserves raw materials, and minimizes energy consumption, aligning with sustainability and circular economy principles [

7,

82,

85].

In the realm of waste management and recycling, inclusive recycling programs have emerged as a transformative strategy for promoting both environmental sustainability and social equity. These programs create employment opportunities in marginalized communities while ensuring the efficient recovery and reuse of materials. By integrating social inclusion into circular strategies, such initiatives demonstrate the potential for circular economy models to address broader socio-economic challenges beyond environmental concerns [

31,

65].

Consumer participation is another critical factor in the success of circular economy initiatives. Companies have implemented behavioral incentives to encourage customers to return used products for refurbishment or recycling. Such strategies help extend product life cycles and reduce waste generation. Research has shown that consumer behavior dynamics, supported by targeted incentives and digital engagement, play a crucial role in fostering sustainable consumption patterns and promoting circularity [

14,

33,

73].

5.1.4. Future Prospects and Research Needs

Future research should focus on developing frameworks and strategies to ensure that the circular economy is inclusive and equitable. This includes identifying ways to involve marginalized communities in circular initiatives and ensuring that they benefit from the transition to circularity. Addressing fairness in the circular economy requires targeted interventions that prevent social inequalities and ensure fair access to sustainable resources [

21,

31,

65].

The adoption of circular economy principles in supply chain management is expected to grow, with more companies exploring closed-loop systems that prioritize resource efficiency and waste reduction. Research is needed to identify the best strategies for scaling these models across different industries. There is significant potential for innovation in circular design and manufacturing, particularly in developing materials and processes that facilitate the disassembly, recycling, and repurposing of products at the end of their lifecycle. Advances in sustainable manufacturing and supply chain strategies, alongside the integration of digital technologies such as blockchain and IoT, can further enhance the feasibility of circular business models [

34,

56,

75].

Further research is also needed to explore how behavior dynamics influence the adoption and success of circular economy strategies. Understanding the role of incentives, policies, and cultural factors in shaping consumer and organizational behavior is crucial to accelerating the shift toward circularity. Social norms, behavioral nudges, and digital platforms have been identified as key factors in influencing sustainable consumption and production patterns, making them important areas for future study [

66,

82,

92].

5.2. Business Models

5.2.1. Integration of Key Domains

Fairness in business models is essential for creating value in a way that benefits all stakeholders, including customers, employees, suppliers, and communities. This involves ensuring the equitable distribution of profits, fair pricing strategies, and ethical sourcing. As businesses increasingly integrate social responsibility into their core strategies, fairness has become a key element in designing sustainable and inclusive business models. Incorporating fairness into business models also contributes to long-term competitive advantage by fostering trust and stakeholder engagement [

21,

77,

93].

Modern business models are progressively being designed with environmental sustainability at their core. This includes adopting strategies that minimize waste, reduce carbon footprints, and utilize renewable resources. Companies are also exploring innovative models, such as the circular economy, which inherently reduces environmental impact by keeping resources in use for as long as possible. The integration of environmental sustainability into business models is not only a response to regulatory pressures but also a strategic approach to meeting consumer demand for greener products and services. Research highlights that integrating circular and green strategies into business models is a key driver for long-term corporate resilience and success [

29,

78].

Behavior dynamics play a crucial role in shaping and adapting business models, particularly in how companies respond to and influence customer behavior. Understanding consumer behavior is essential for developing business models that not only meet current market needs but also encourage sustainable consumption patterns. Additionally, internal behavior dynamics within organizations influence how business models are implemented and sustained, particularly when new, more sustainable strategies are introduced. The adoption of sustainable business models often requires shifts in organizational culture, employee engagement, and market perceptions, all of which are deeply connected to behavior dynamics [

36,

82,

94].

Table 4.

Matrix of Key Domain Impacts on Business Model Elements

Table 4.

Matrix of Key Domain Impacts on Business Model Elements

| Element |

Fairness |

Environmental Impact |

Behavior Dynamics |

| Value Proposition |