Submitted:

15 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

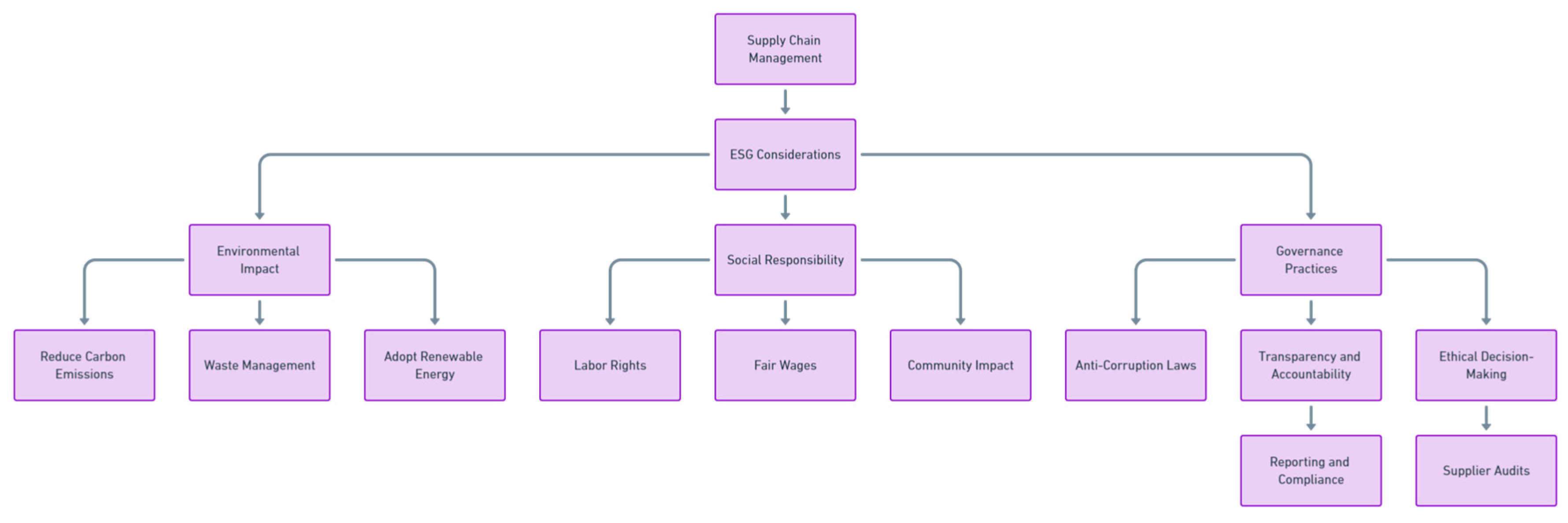

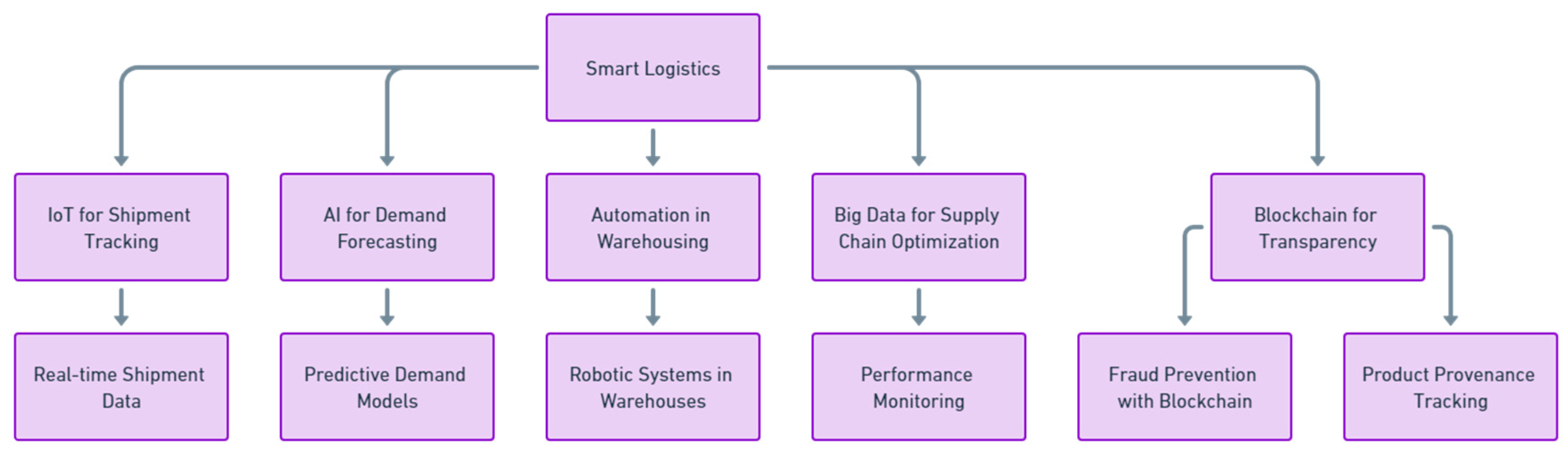

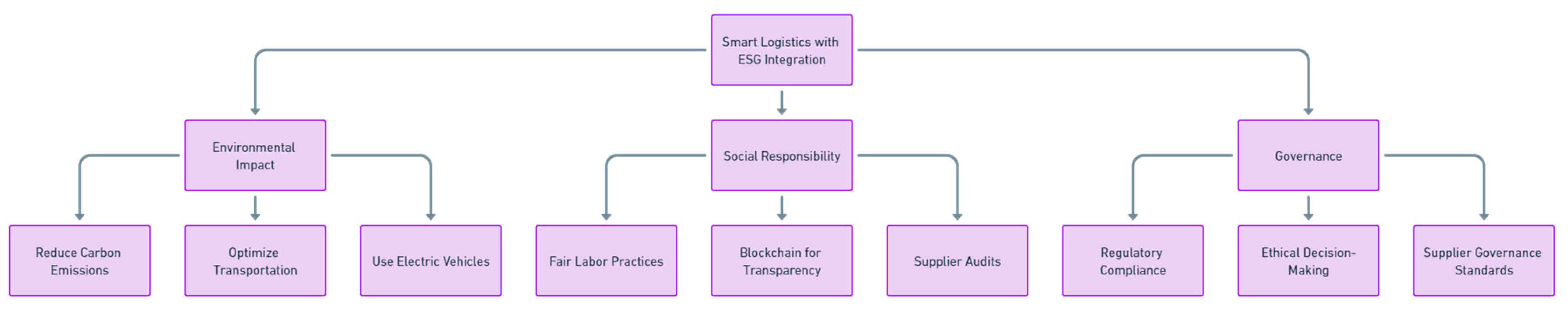

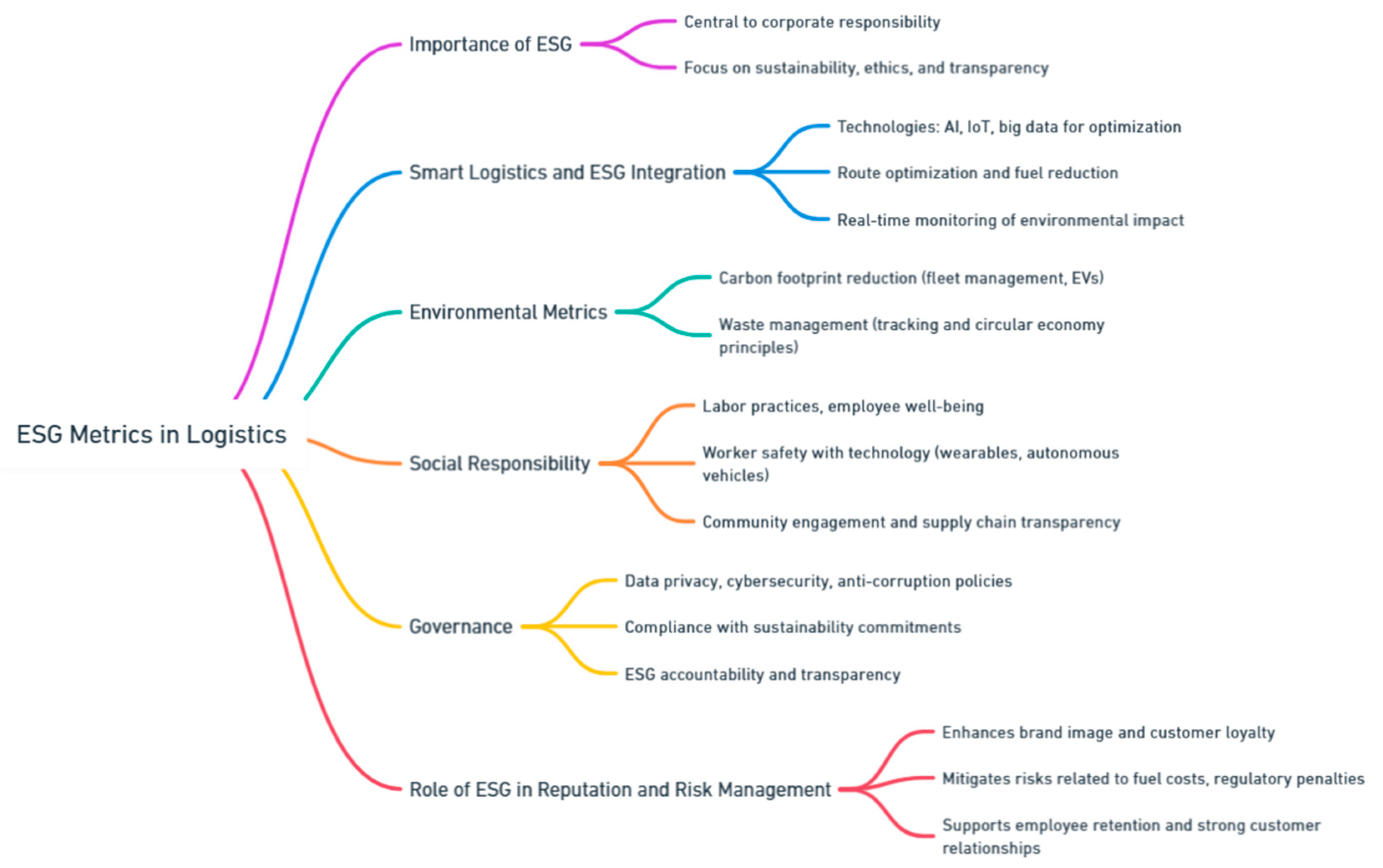

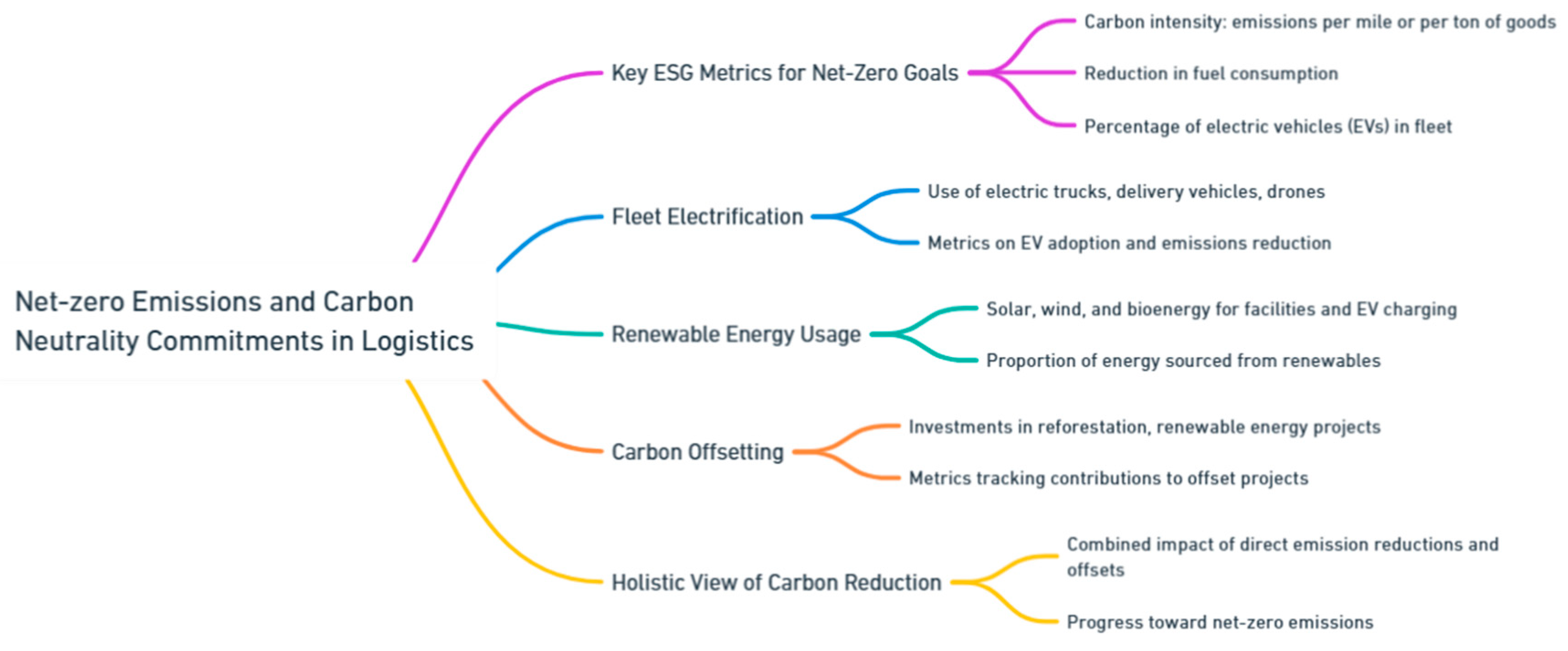

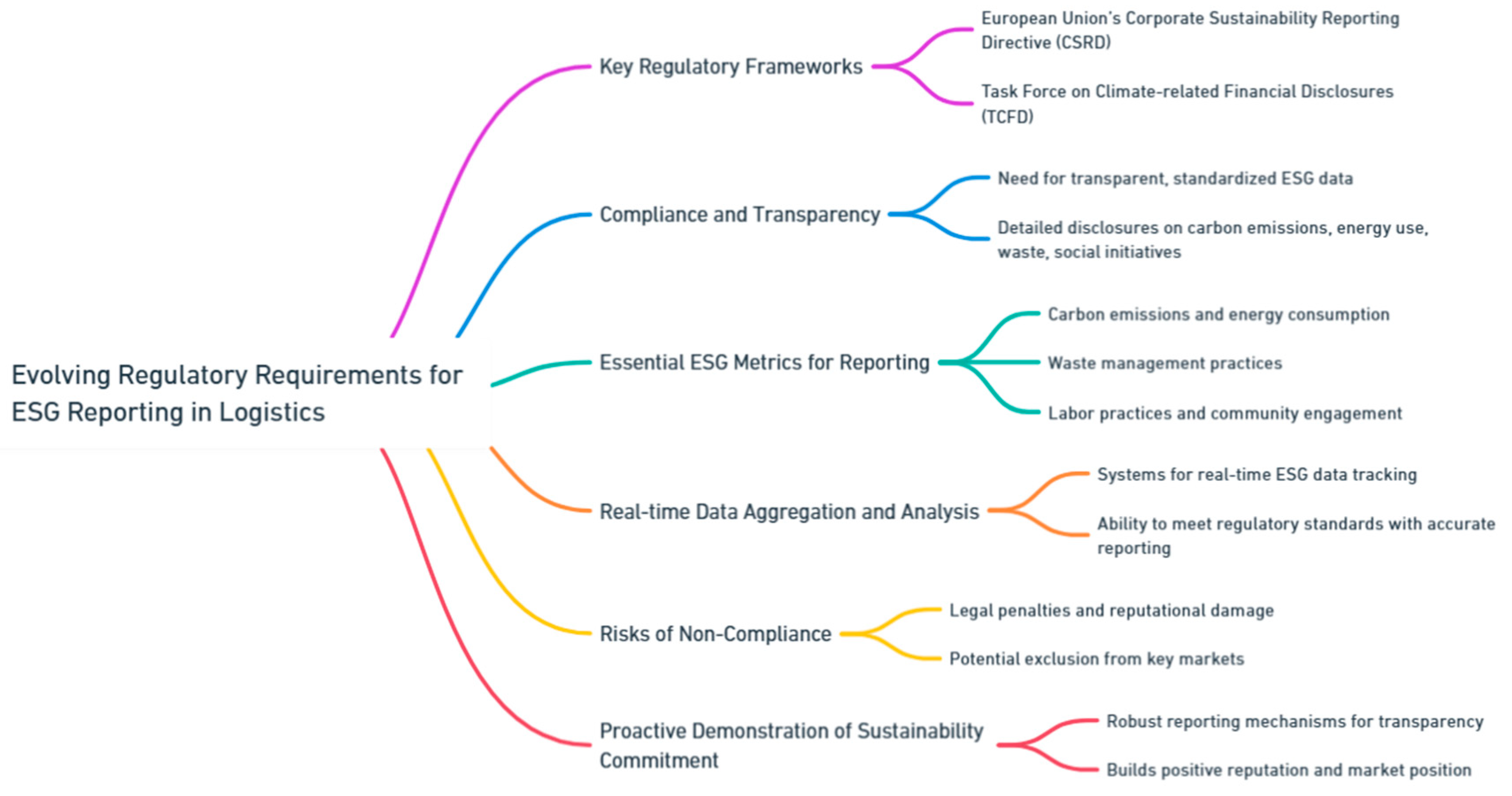

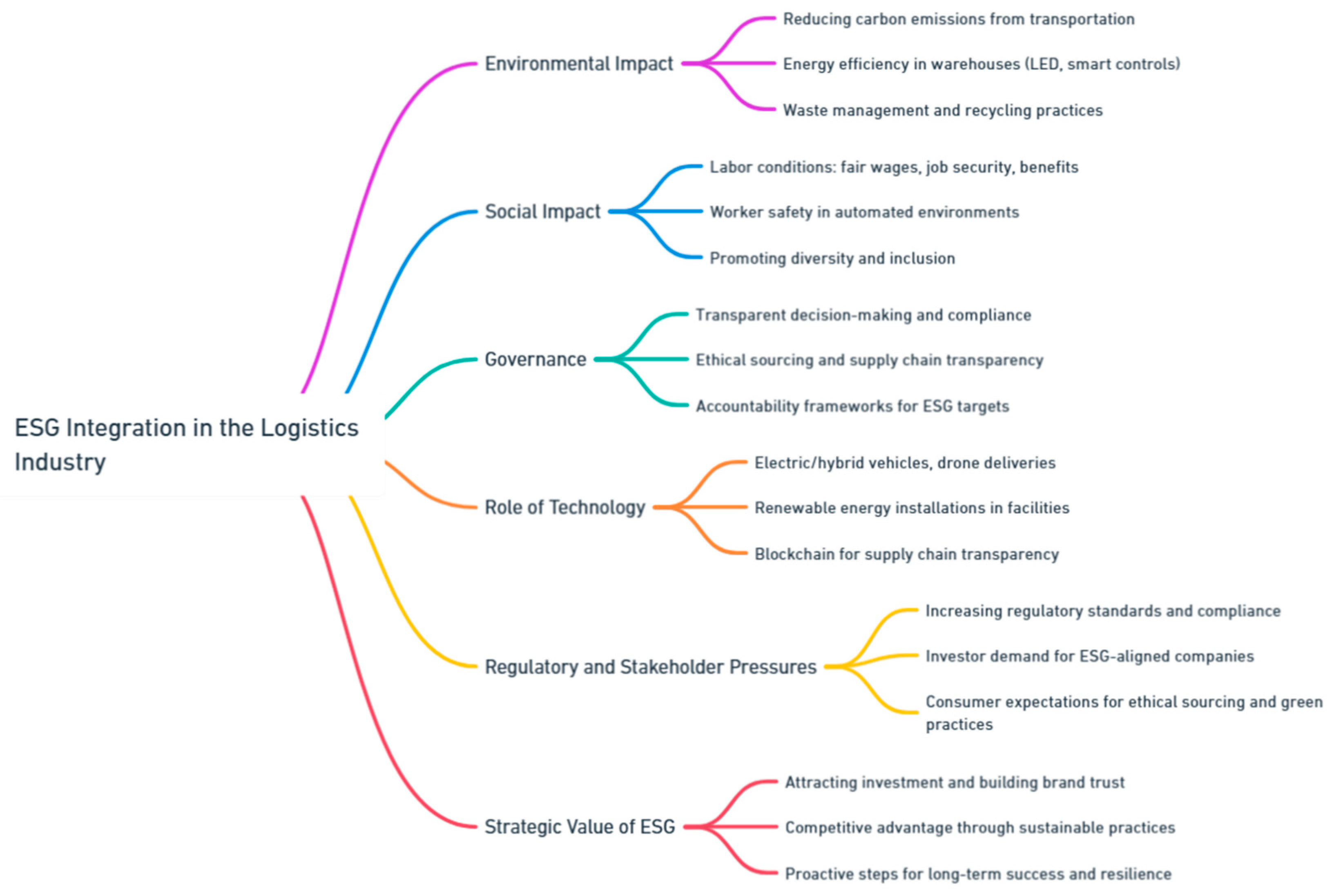

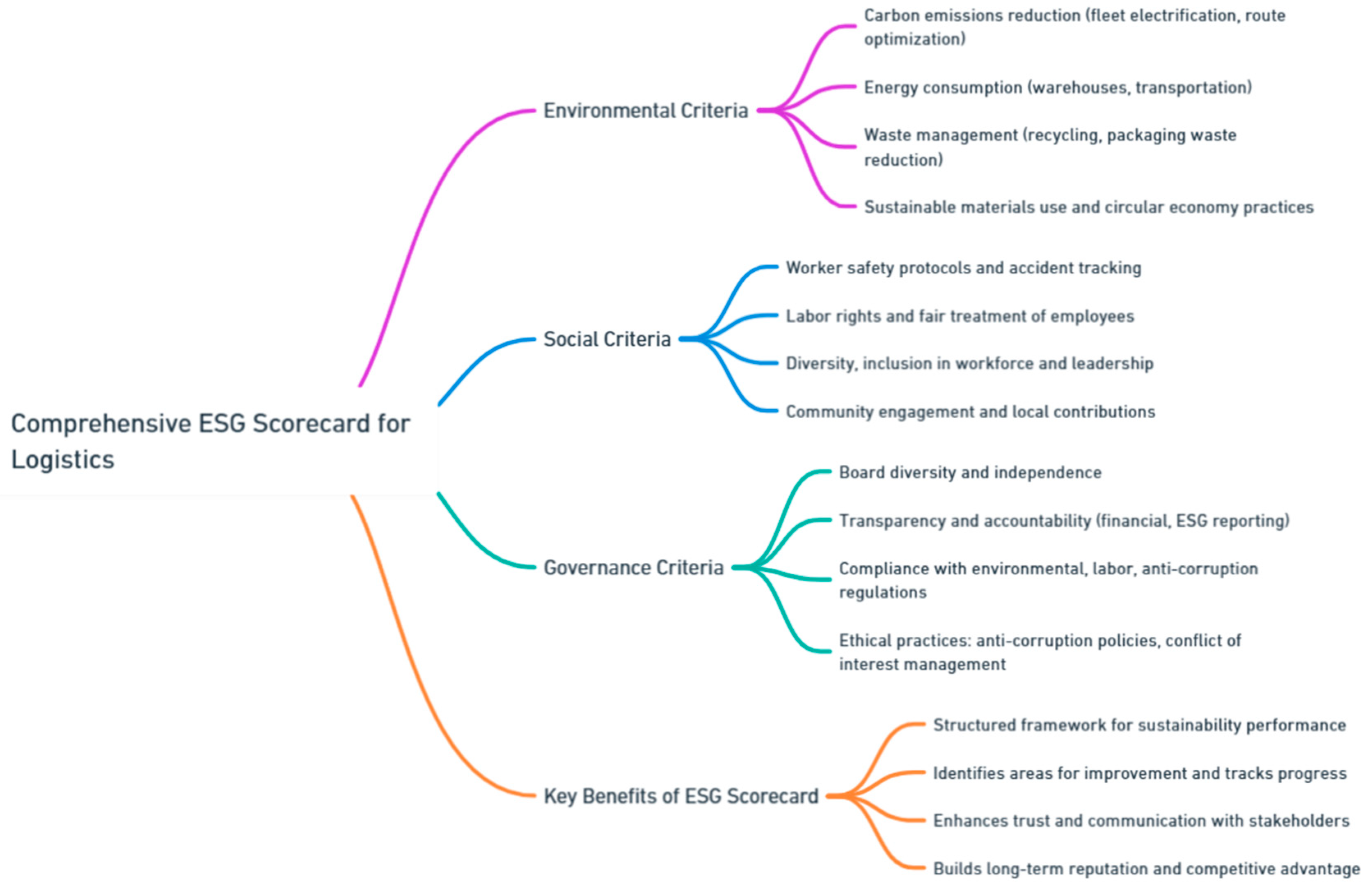

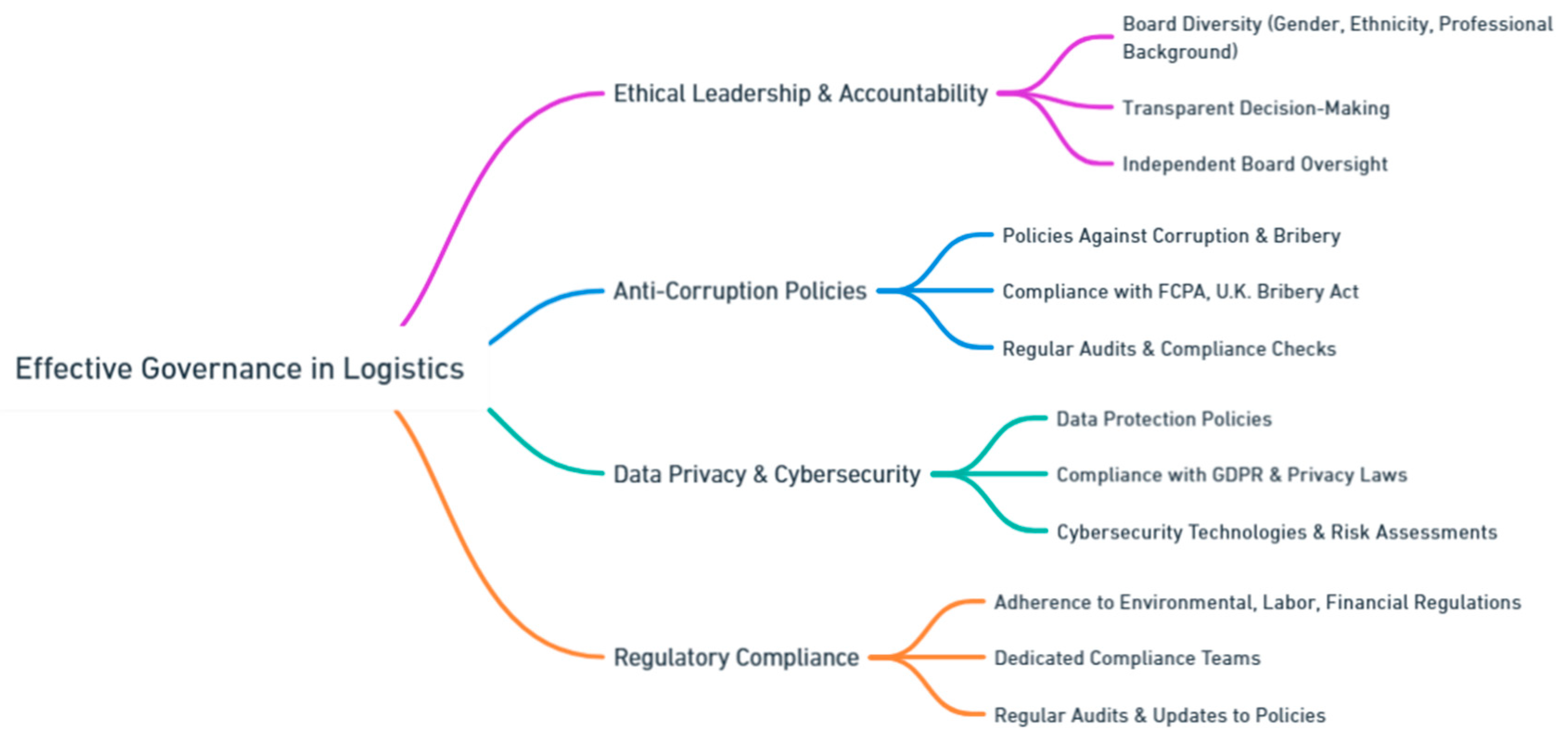

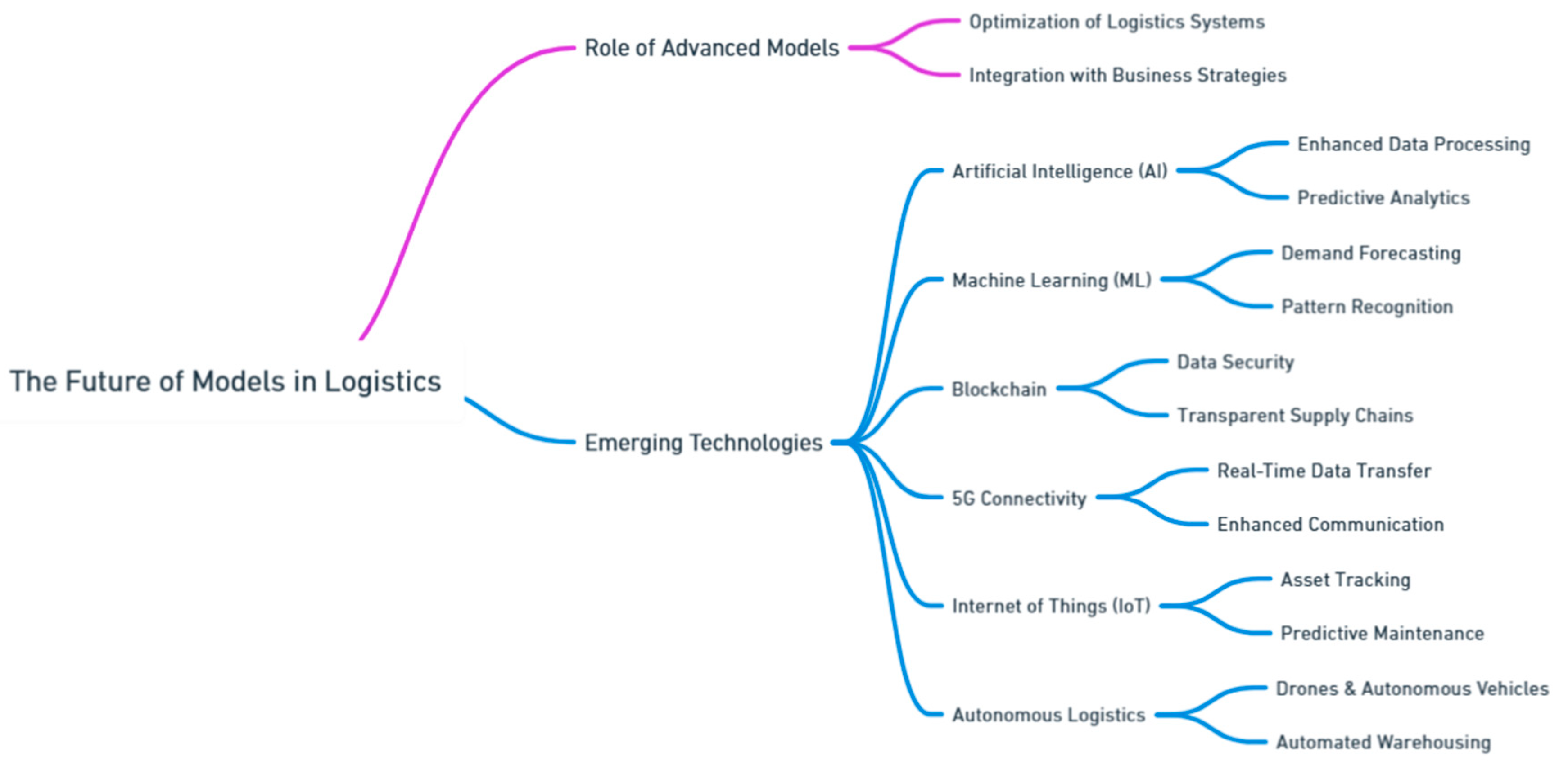

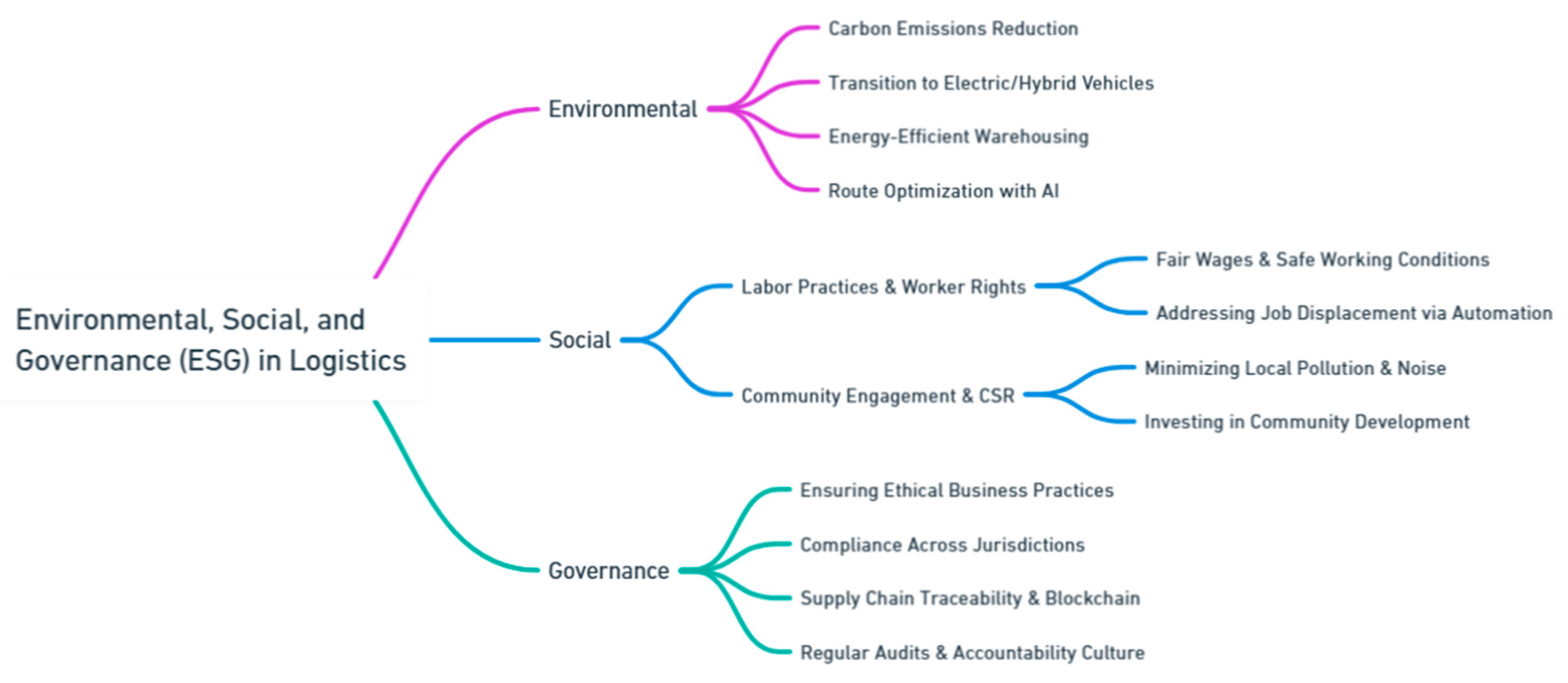

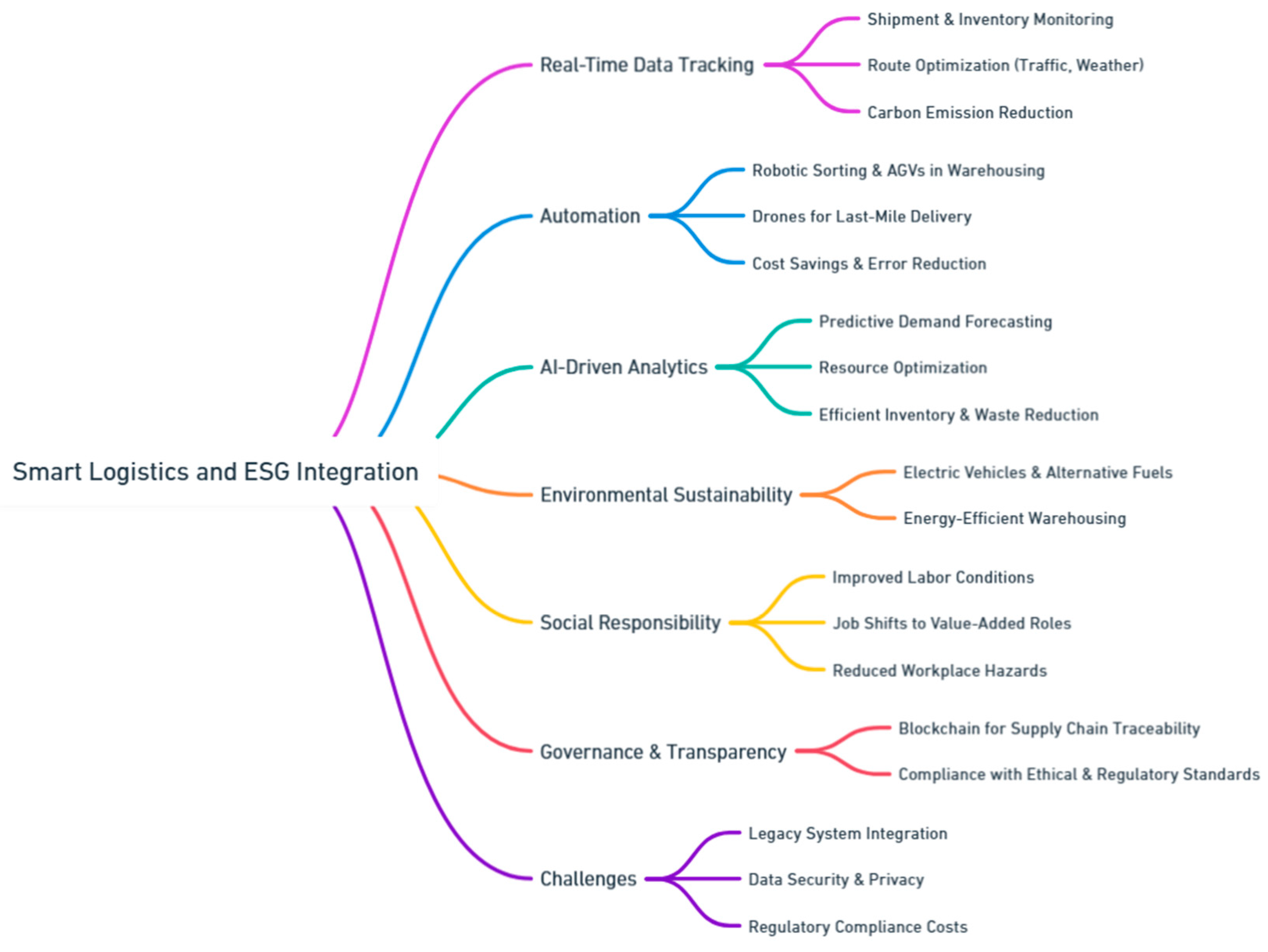

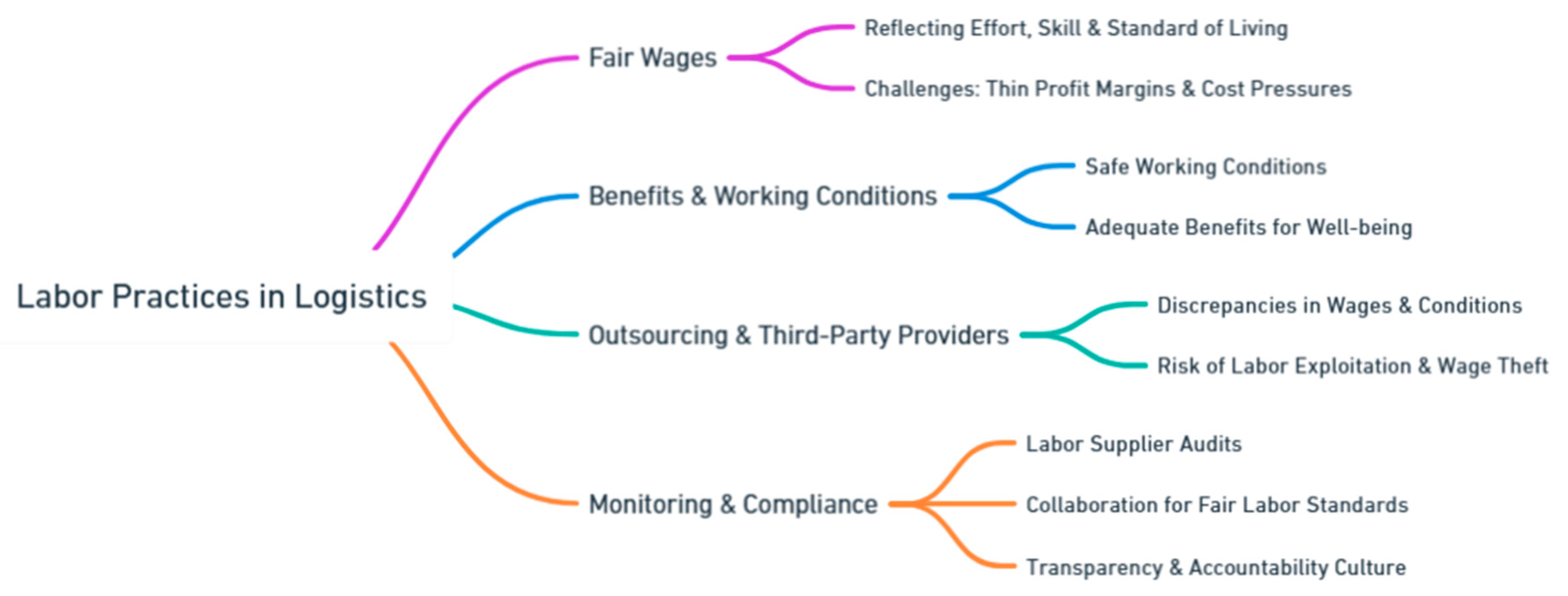

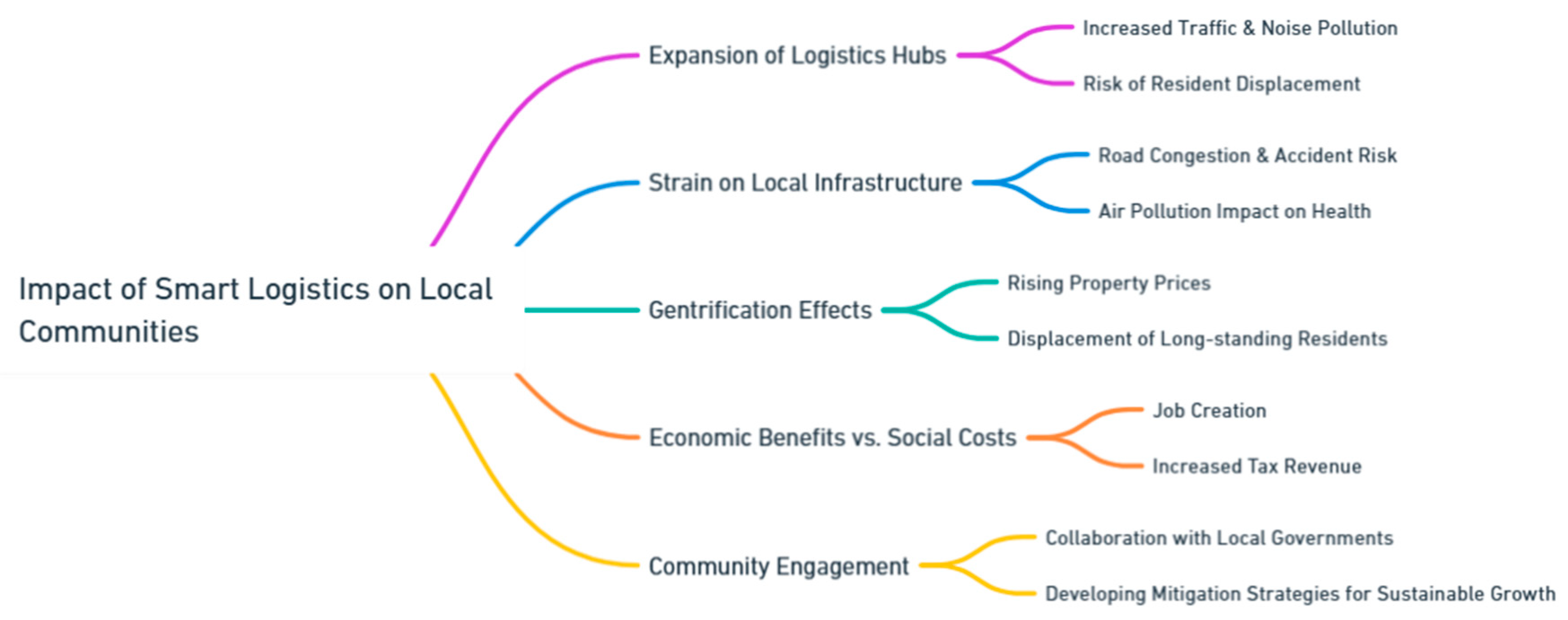

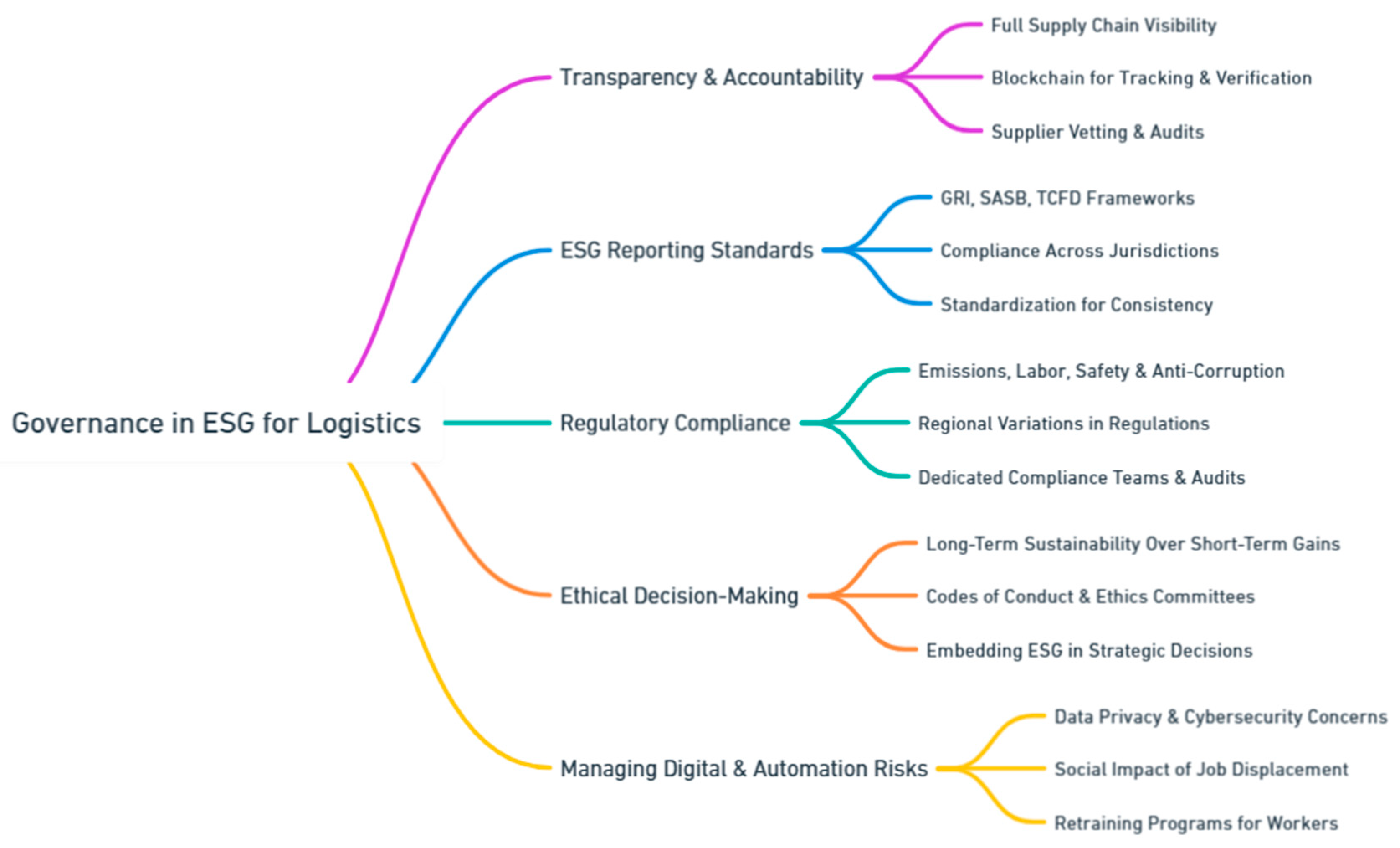

The integration of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) principles into smart logistics represents a transformative approach to supply chain management, offering solutions that address 6 critical challenges in sustainability, ethical labor practices, and transparency. With the increasing awareness of climate change, social inequalities, and governance issues, companies worldwide are turning to advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), big data, blockchain, and the Internet of Things (IoT) to embed ESG principles into their logistics operations. This article explores the role of smart logistics in promoting sustainability and aligning supply chains with ESG goals. It highlights the environmental aspect by showcasing how AI and big data-driven route optimization can reduce fuel consumption and lower carbon emissions. The use of electric vehicles (EVs) and hybrid trucks is also discussed, particularly for last-mile deliveries, as part of efforts to minimize the carbon footprint of logistics operations. Additionally, smart warehouses equipped with IoT devices, automation, and AI-driven systems significantly contribute to improving energy efficiency and reducing waste, further advancing the sustainability agenda. Social responsibility in the context of ESG is equally emphasized, particularly regarding labor practices in global supply chains. Technologies such as blockchain enhance transparency by allowing companies to trace the origin of products and verify adherence to fair labor standards. AI and data analytics are also crucial for monitoring supplier compliance with social standards, reducing risks associated with unethical practices. Governance, the third pillar of ESG, plays a critical role in promoting transparency and accountability across supply chains. Smart technologies help improve oversight, ensure compliance with regulatory requirements, and mitigate risks related to corruption and fraud. In conclusion, the article underscores the importance of integrating ESG principles into smart logistics as a strategic imperative for companies looking to enhance their competitiveness, resilience, and long-term success in the global marketplace.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Rise of ESG in Global Supply Chains

1.2. Smart Logistics: An Overview of Technologies and Trends

1.3. Integrating ESG Principles into Smart Logistics

2. Literature Review

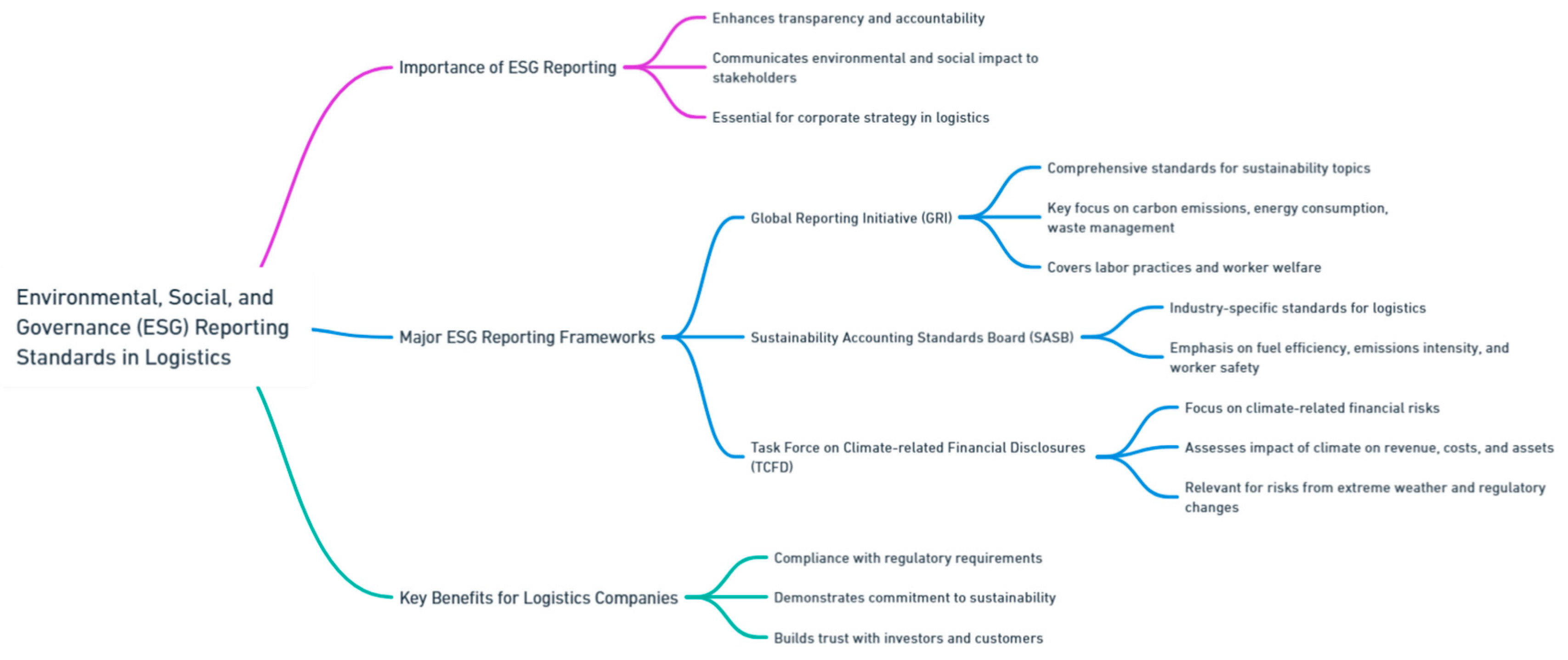

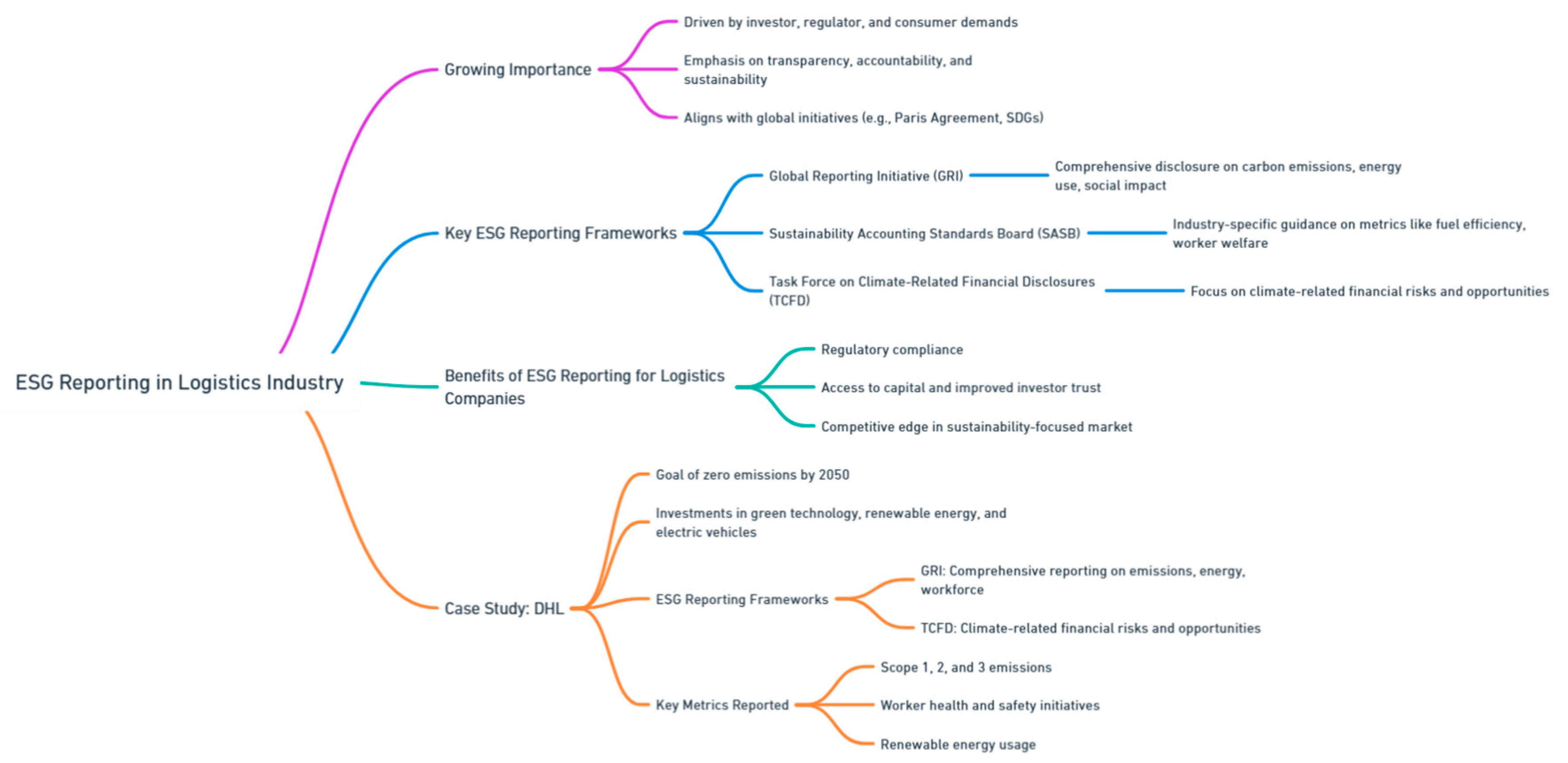

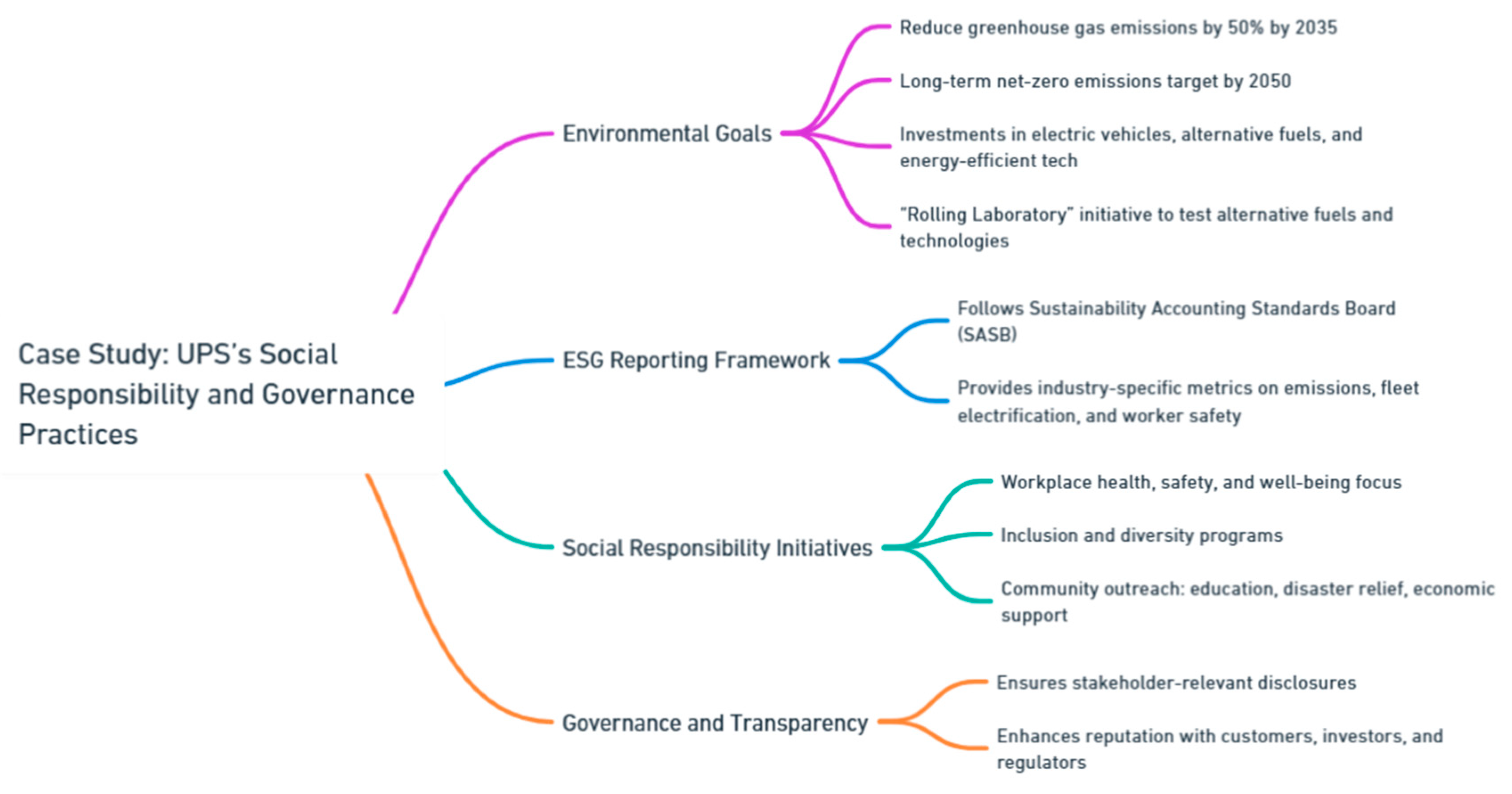

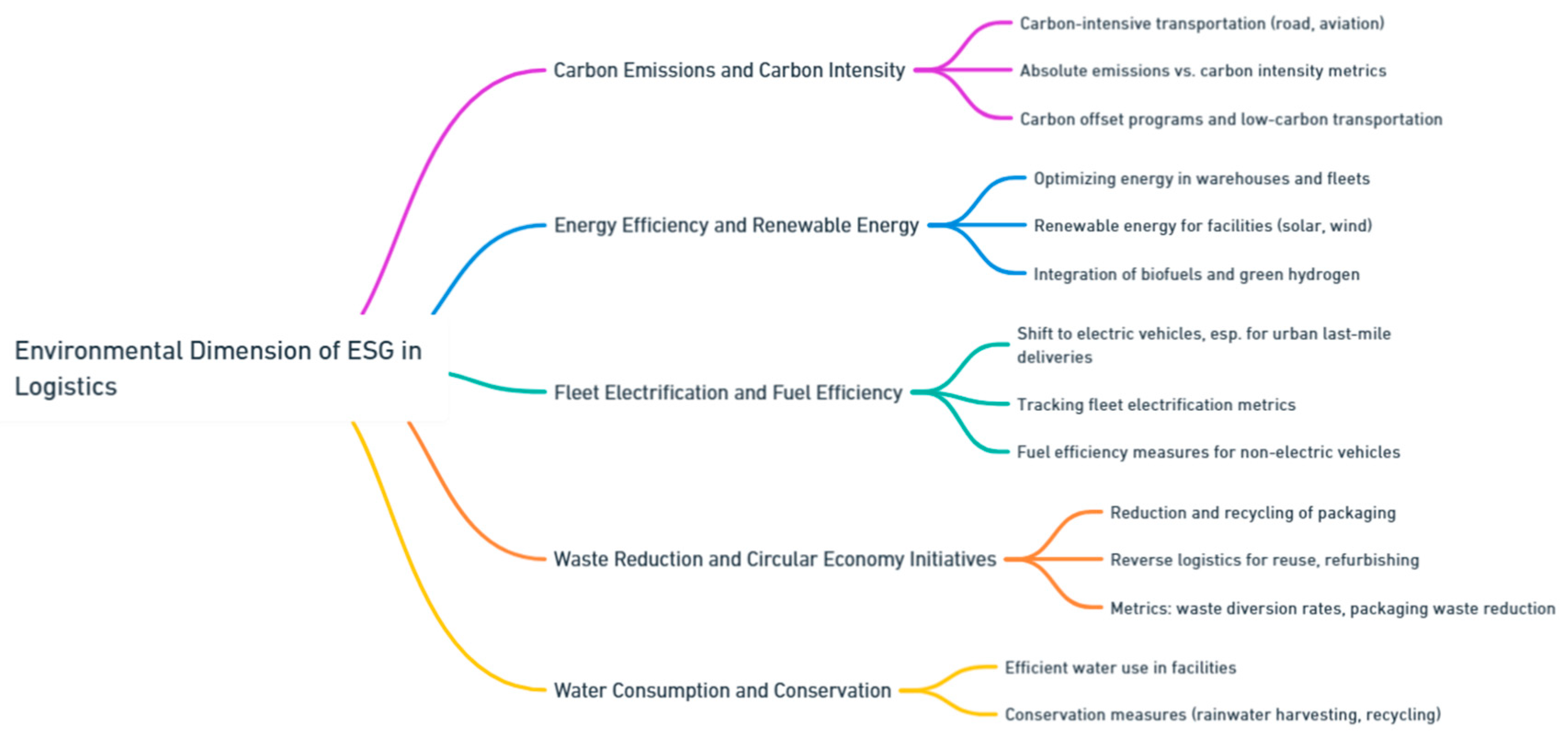

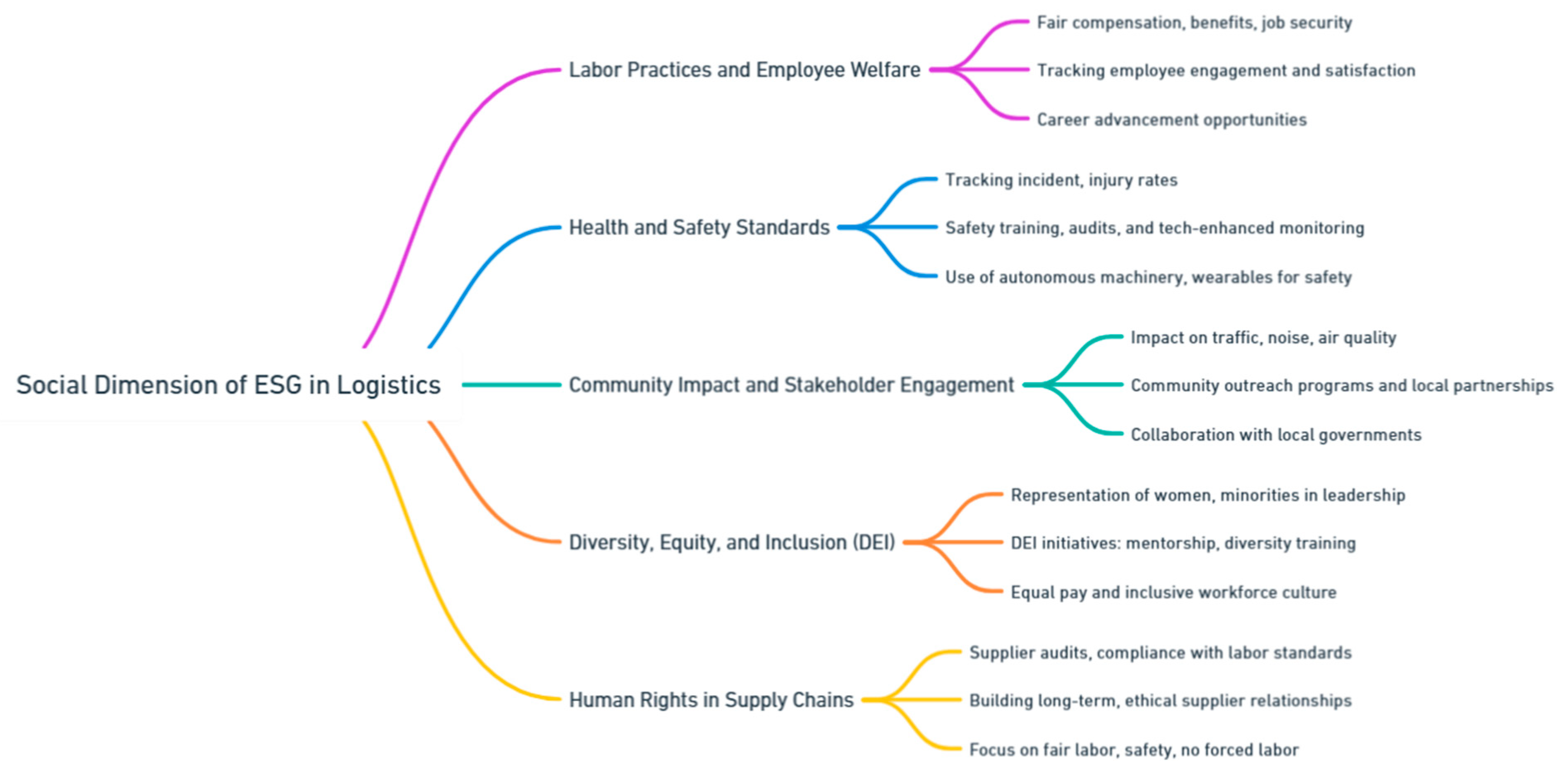

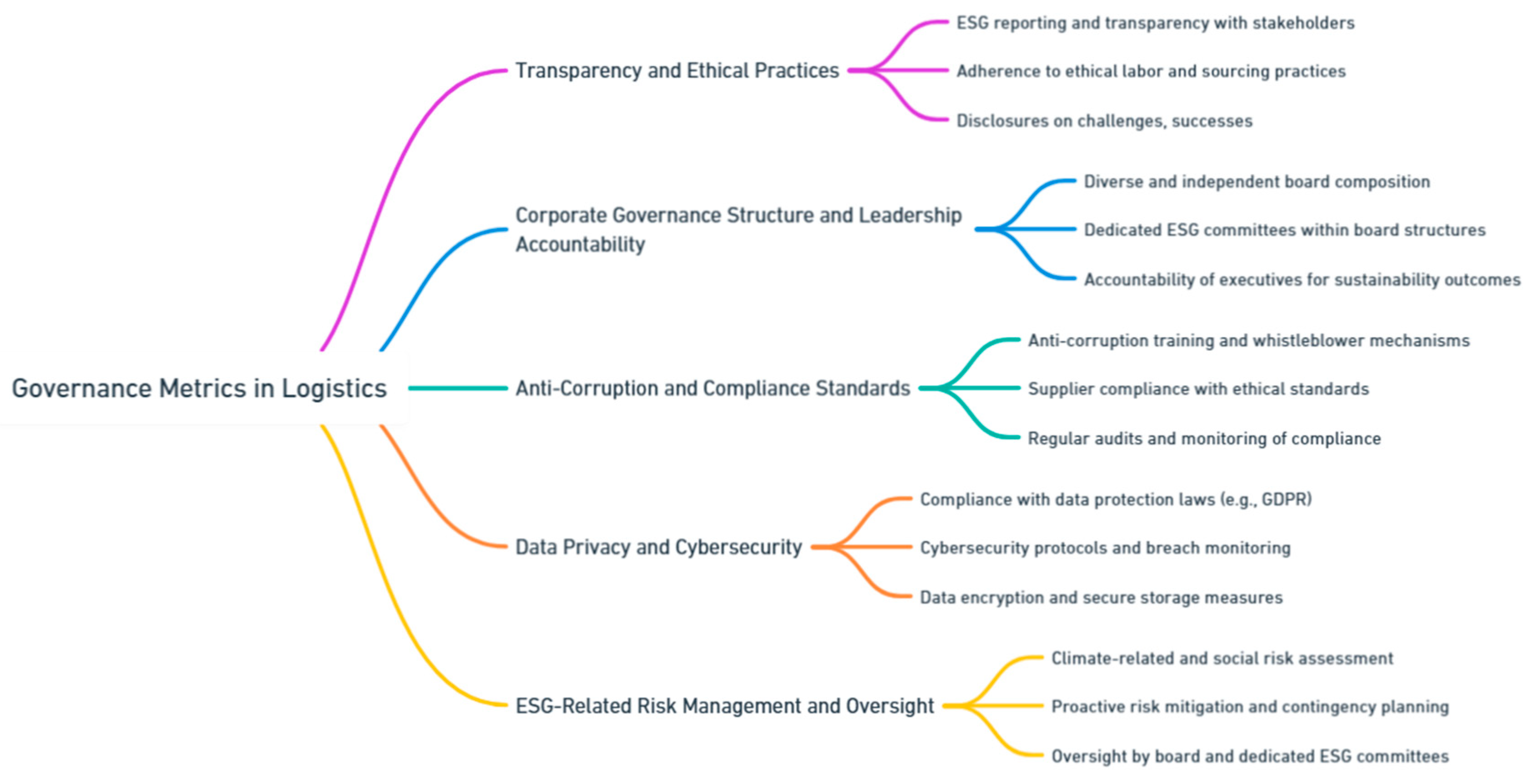

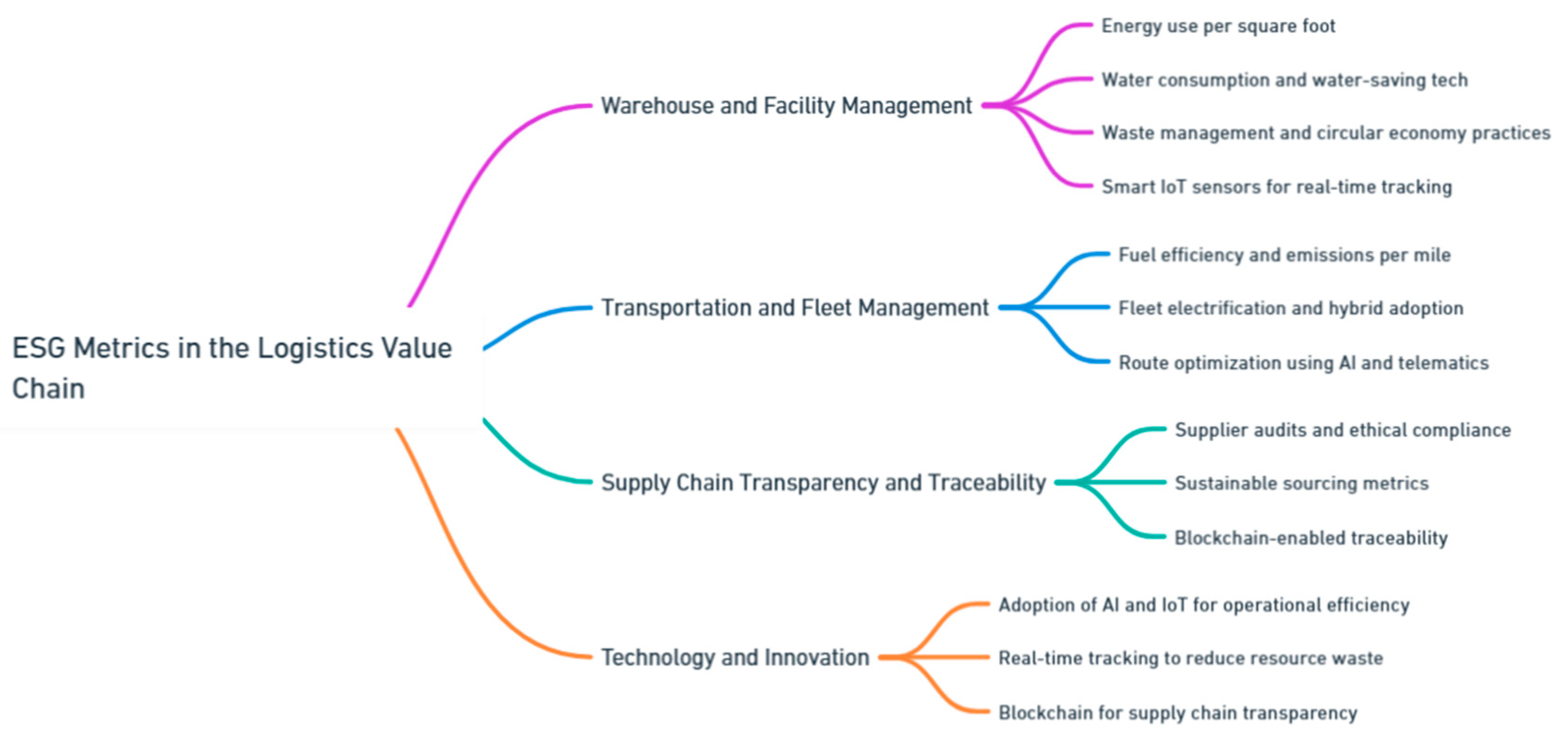

2.1. ESG Frameworks: Environmental, Social, and Governance Dimensions

| Macro-theme | Articles |

| Impact of ESG on Global Supply Chain Management | Bisetti et al., (2023); Lu et al., (2023); Sardanelli, et al., (2022); Sharma, et al., (2023); Ahmed and Shafiq (2022); Jia, et al., (2024); Gualandris, et al. (2021); Archer (2021); Boersma, et al. (2022); Bade, et al. (2024); Dai and Tang, (2022); Di Paola, et al. (2023); de Góes, et al. (2021); Eggert and Hartmann, (2023); Erhun, et al. (2021); Hryhorak, et al. (2022); Laari, et al. 2022; Lèbre, et al. (2022); Lee, et al. (2021); Liao and Pan, (2021); Li, et al. (2023); Li, et al., (2023); Nielsen, (2023); Sachin and Rajesin, (2022); Pérez et al, (2022); Serafeim and Yoon (2022). |

| Technological Integration in ESG and Supply Chains | Qian, et al. (2023); Liu, et al. (2021); Zhang, et al. (2023); Chen, et al. (2024); Zhang and Huang (2024), Asif, et al. (2023); Wang (2023); Saxena, et al. (2022); Busco, et al. (2020); Engel-Cox, et al. (2022); Fatimah, et al. (2023); Kannan, and Seki, (2023); Khan, et al. (2023); Kumar, et al. (2024); Li et al., (2022); Mugurusi and Ahishakiye, (2022); Park and Li, (2021); Zhu and Zhang; (2024); Zioło, et al. (2023). |

| ESG Risk Management and Vulnerabilities in Supply Chains | Tsang, et al. (2024); Tang, et al. (2023); Henrich, et al. (2022); Redondo Alamillos and Mariz (2022); Lawley et al. (2024); Zhang, et al. (2024); Mateska et al. (2022); Chen, et al. (2022); Câmara, (2022); Brewster, (2022); Comoli et al., (2023); Hu, et al. (2023); Gassmann, et al. (2021); Le Tran and Coqueret, 2023; Kelly, (2022); Lin et al., (2023); Lepetit et al., (2021); Van Assche and Narula, (2023); Vivoda and Matthews, (2023); Trahan and Jantz, (2023). |

| Social Responsibility, Green Finance, and ESG Reporting in Supply Chains | Baid and Jayaraman (2022); Gao et al. (2023); Li and Liu (2023); Park, et al. (2022); Wilburn and Wilburn (2020); Bril, et al. (2022); Clark and Dixon (2024); Bhattacharya and Bhattacharya (2023); Bradley, (2021); Chiu and Fong, (2023); Dathe et al. (2024); Edunjobi, (2024), Efthymiou, et al. (2023); de Hoyos Guevara and Dib, (2022); Hsu, et al. (2022); Jinga, (2021); Kandpal, et al. (2024); Kaplan and Ramanna, (2021); Krishnamoorthy (2021), Kuntz (2024); Lee, et al. (2020); Liu (2023); Mohieldin, et al. (2022); McLachlan and Sanders, (2023); López Sarabia, et al. (2021); Saini, N., Antil, A., Gunasekaran, A., Malik, K., & Balakumar, S. (2022); Patil, et al. (2021); Yang, (2023); Wamane, (2023). |

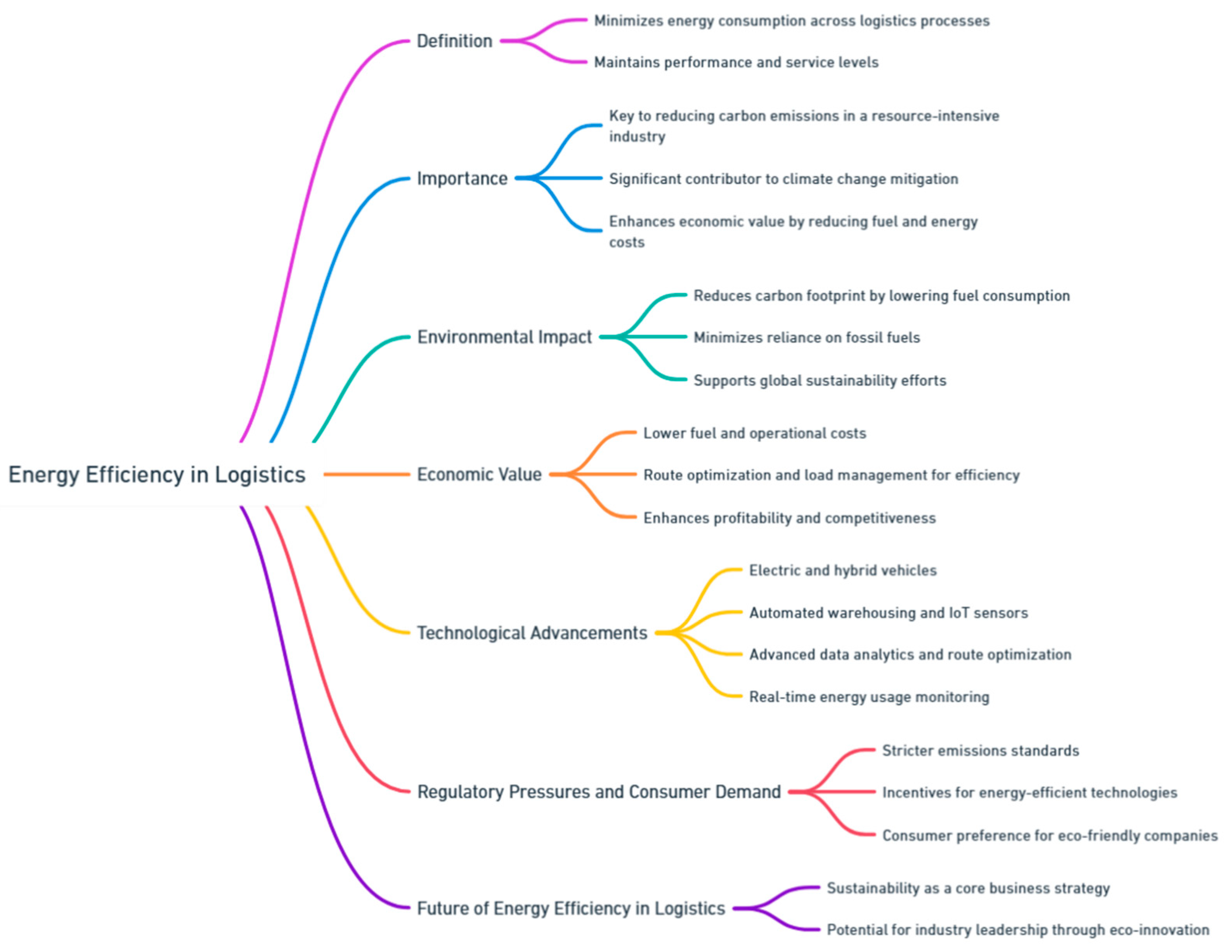

2.2. Smart Logistics Technologies: IoT, AI, Big Data, and Automation

2.3. The Intersection of ESG and Smart Logistics: Current Research and Gaps

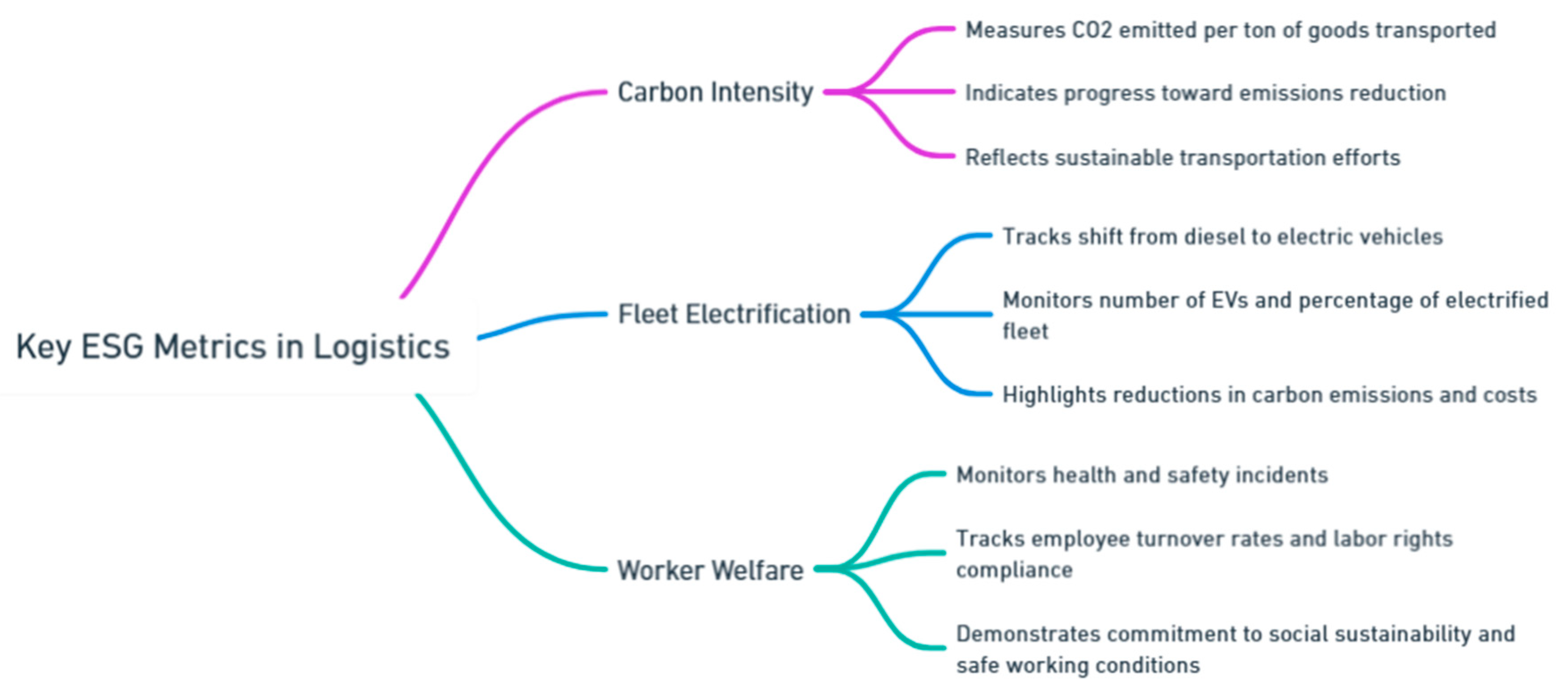

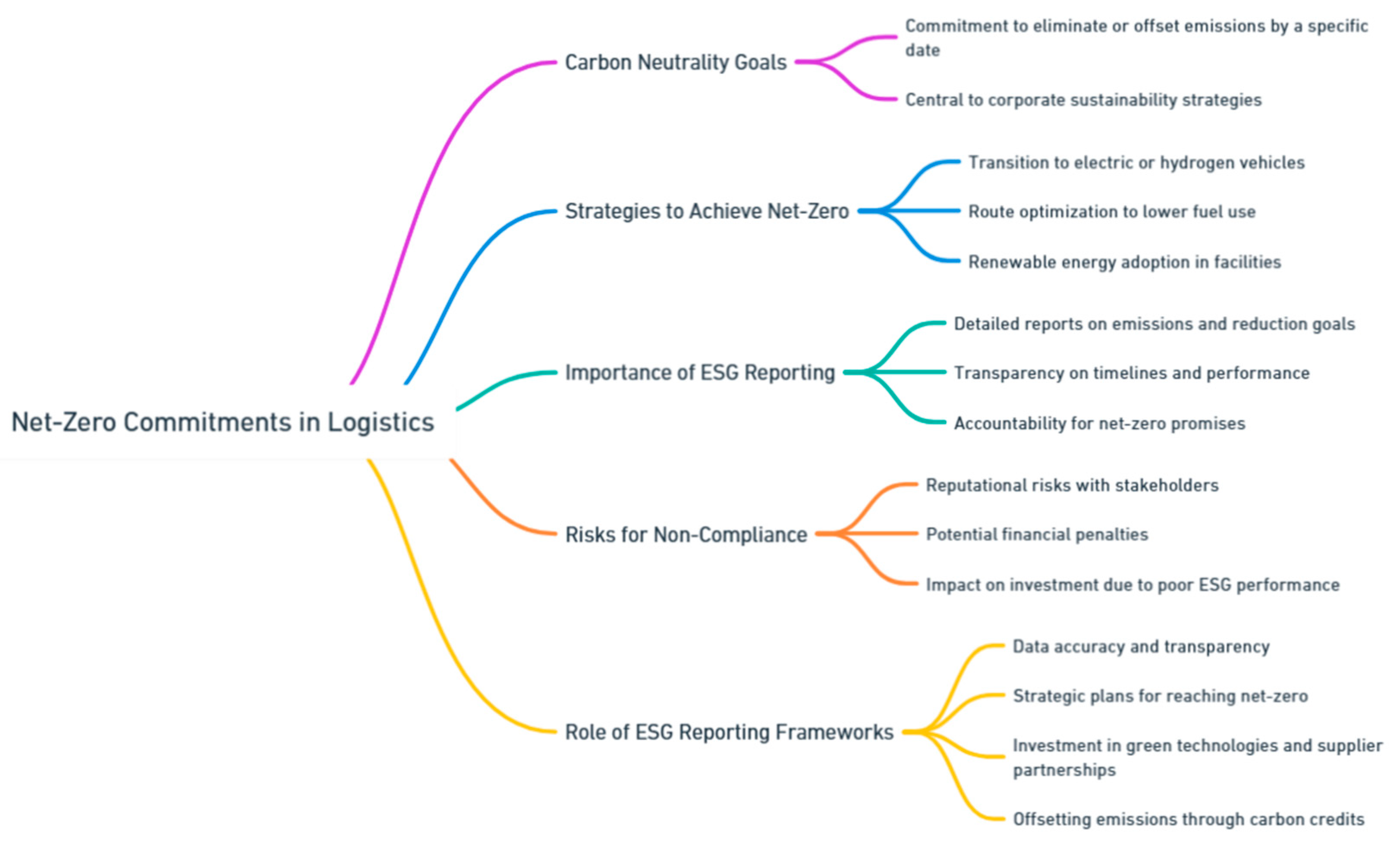

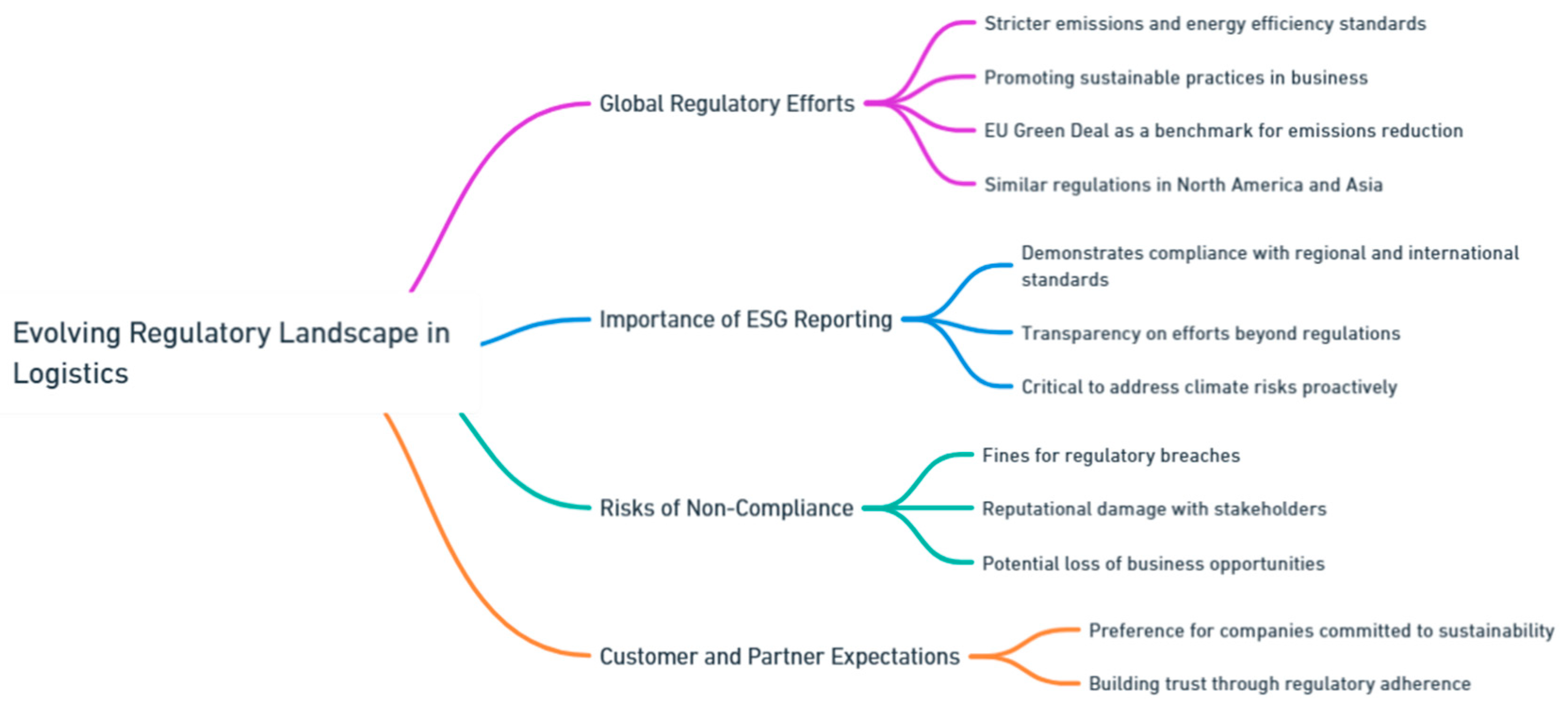

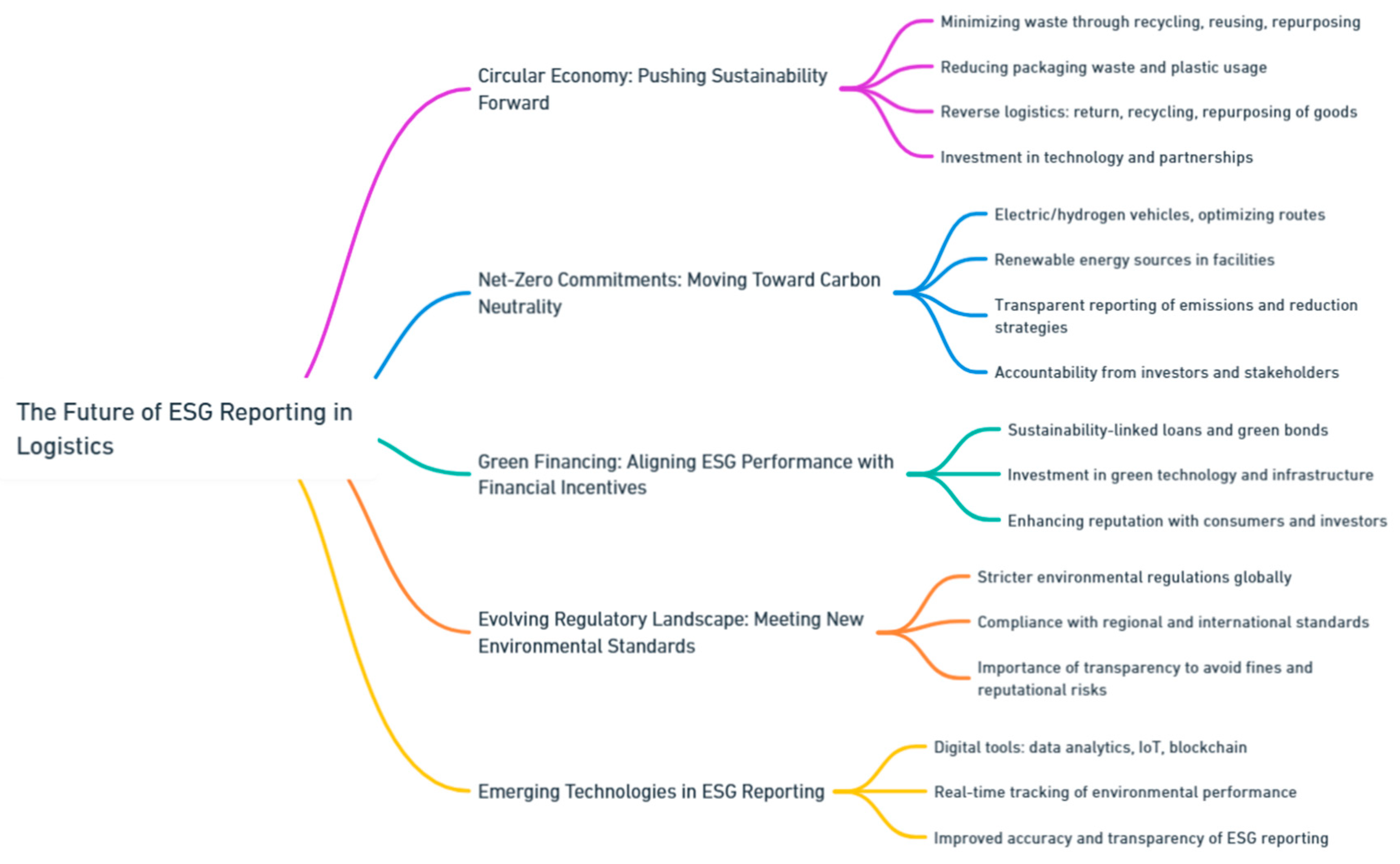

3. Metrics for Evaluating ESG in Logistics Operations

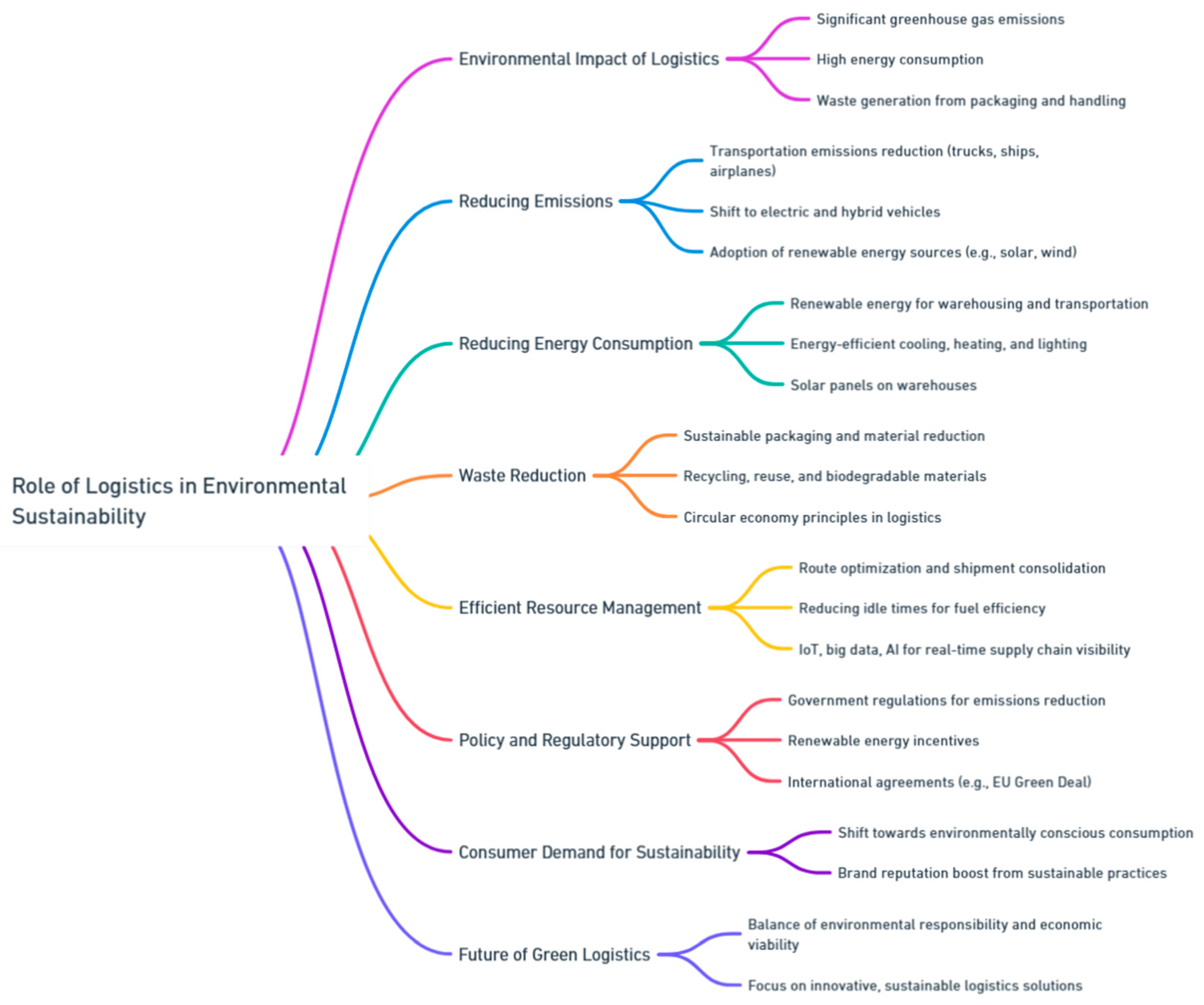

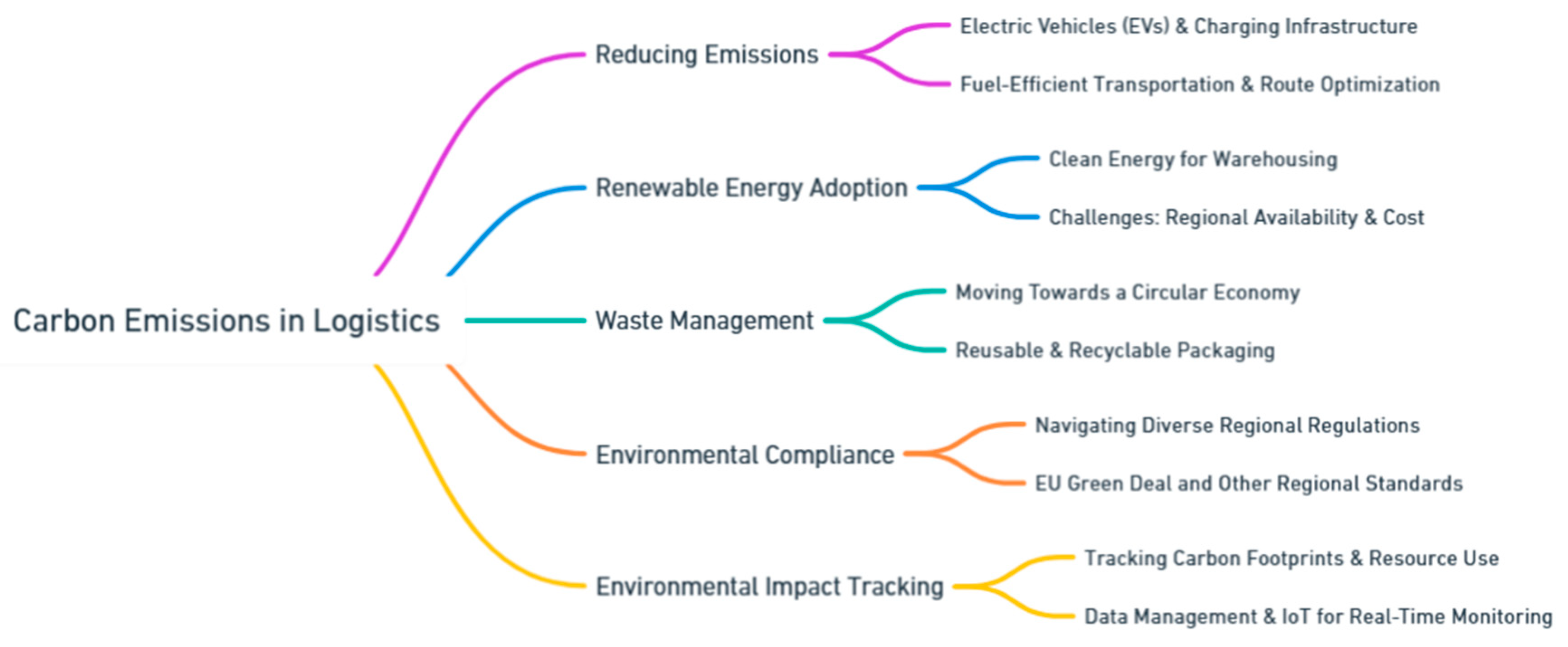

4. Environmental Impact of Smart Logistics

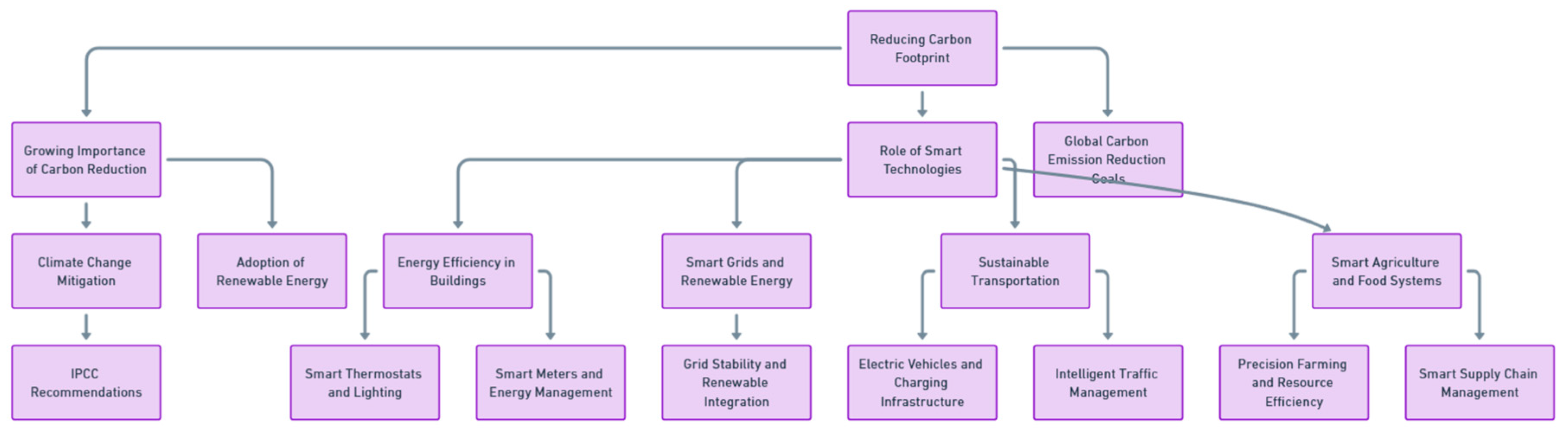

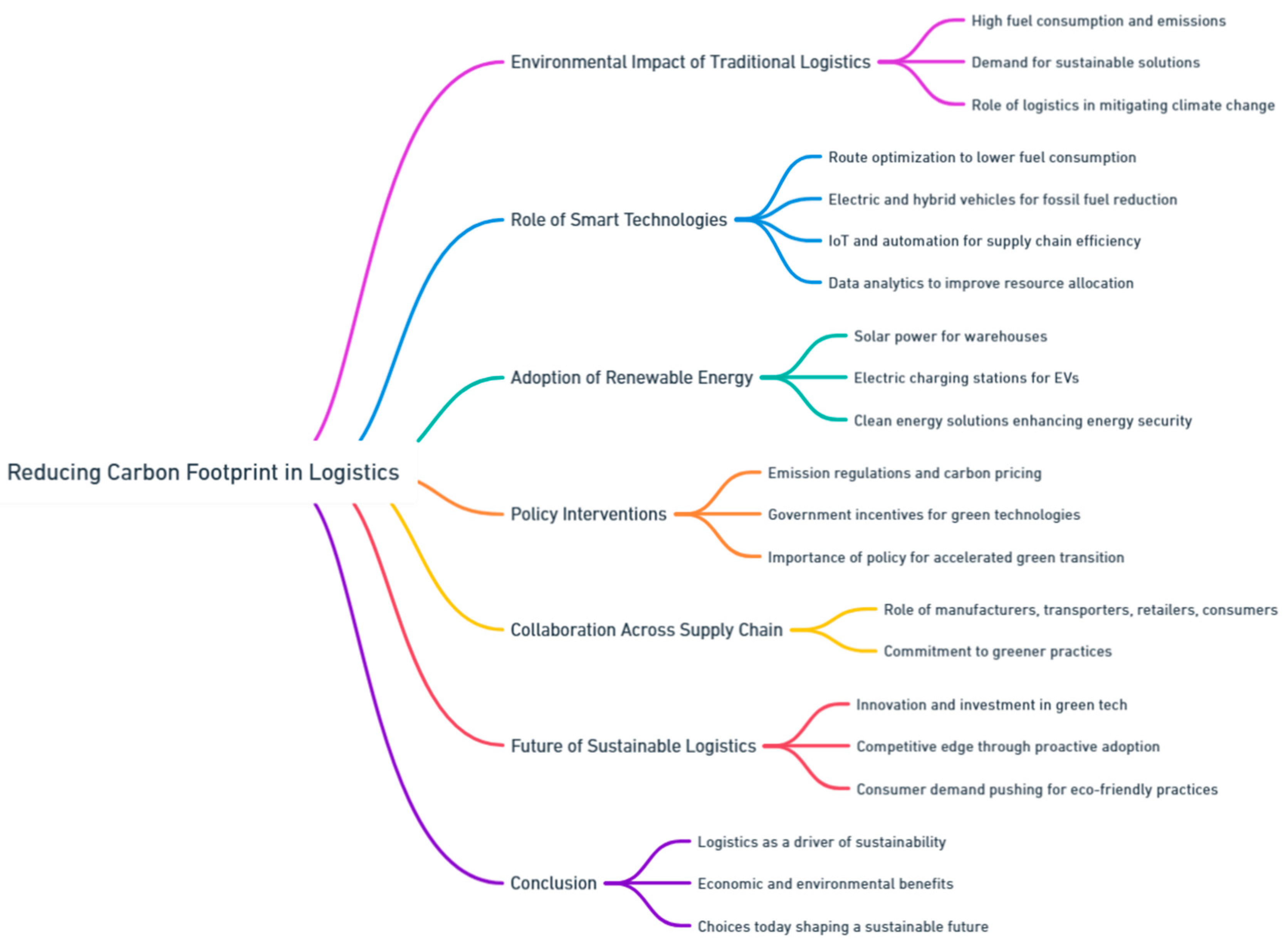

4.1. Reducing Carbon Footprint Through Smart Technologies

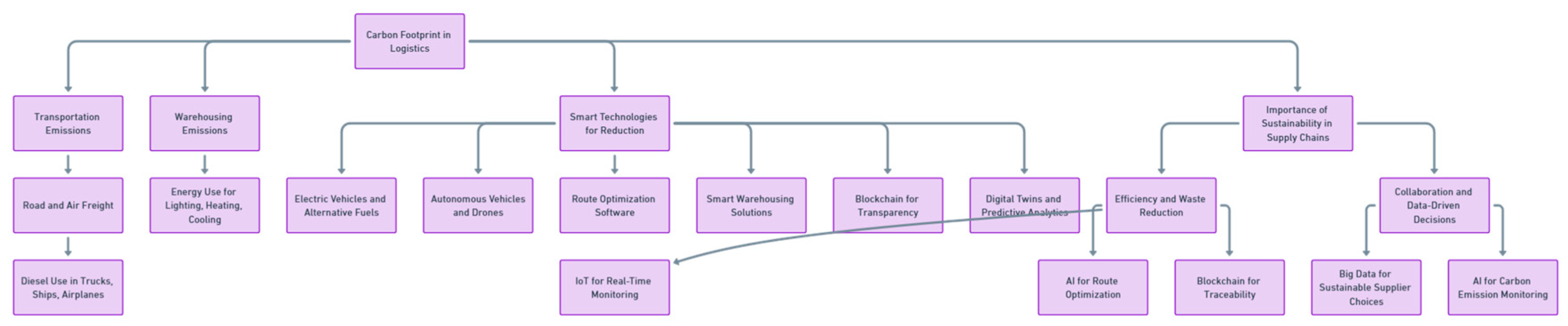

4.1.1. Overview of Carbon Footprint in Logistics

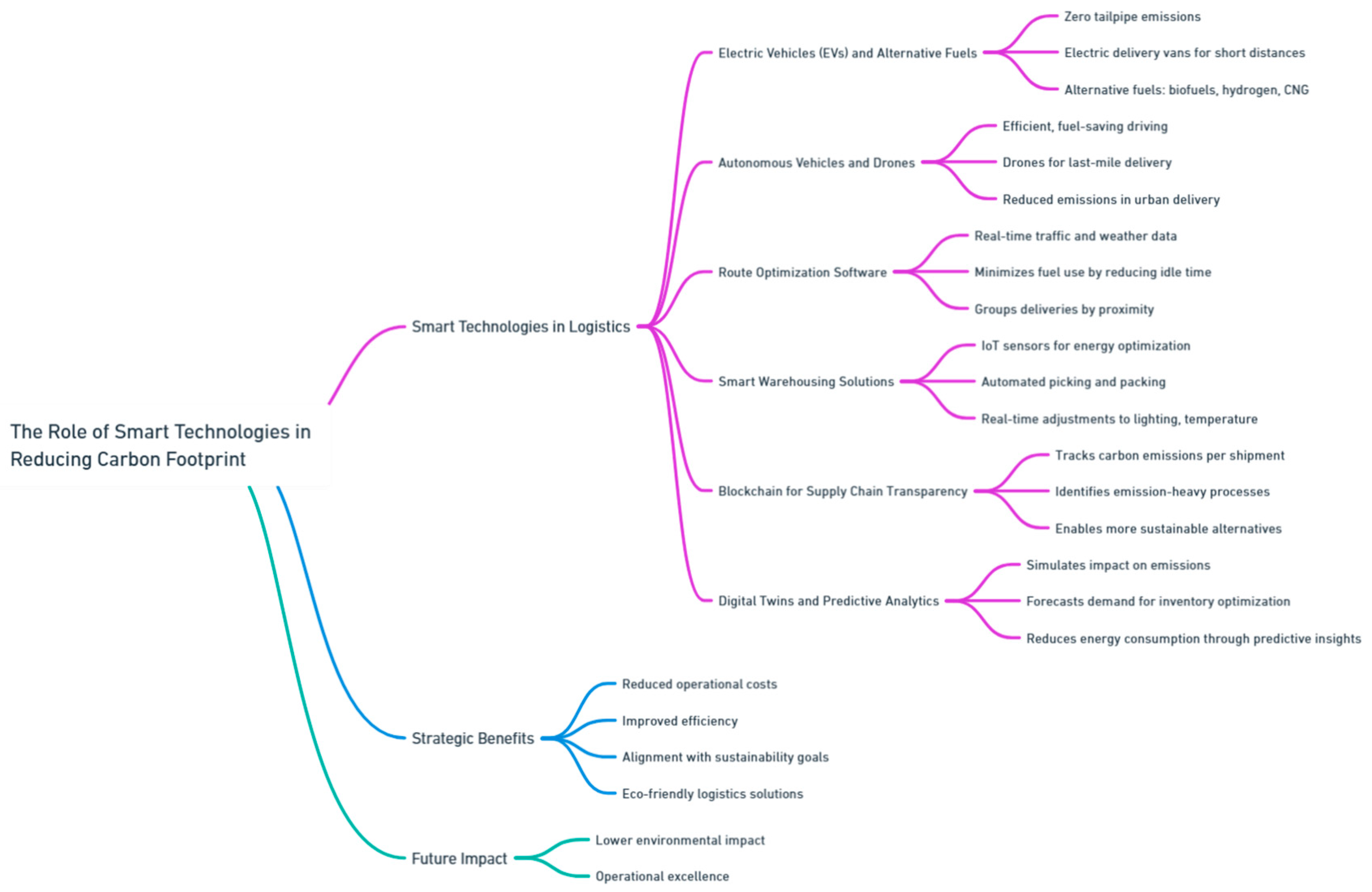

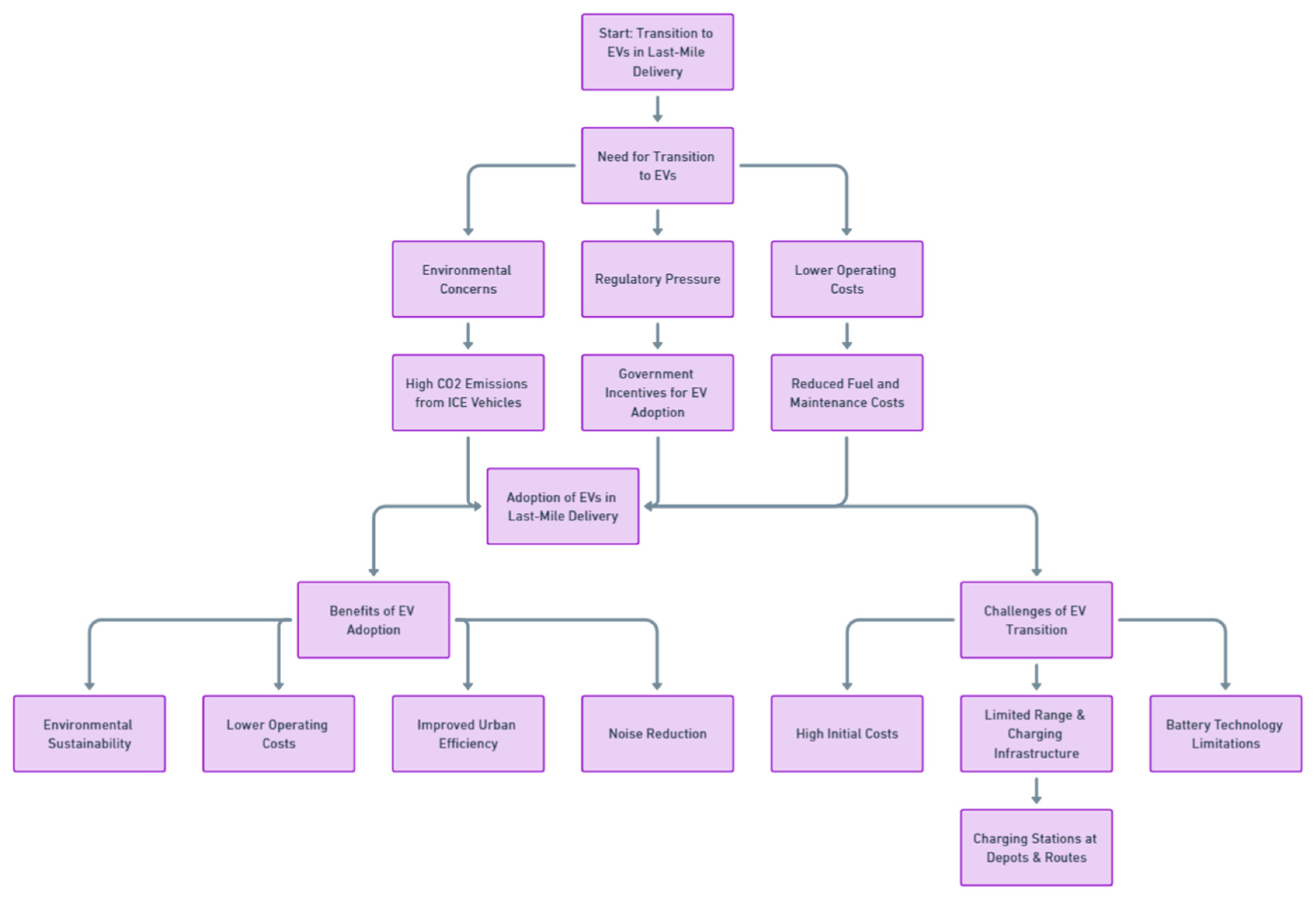

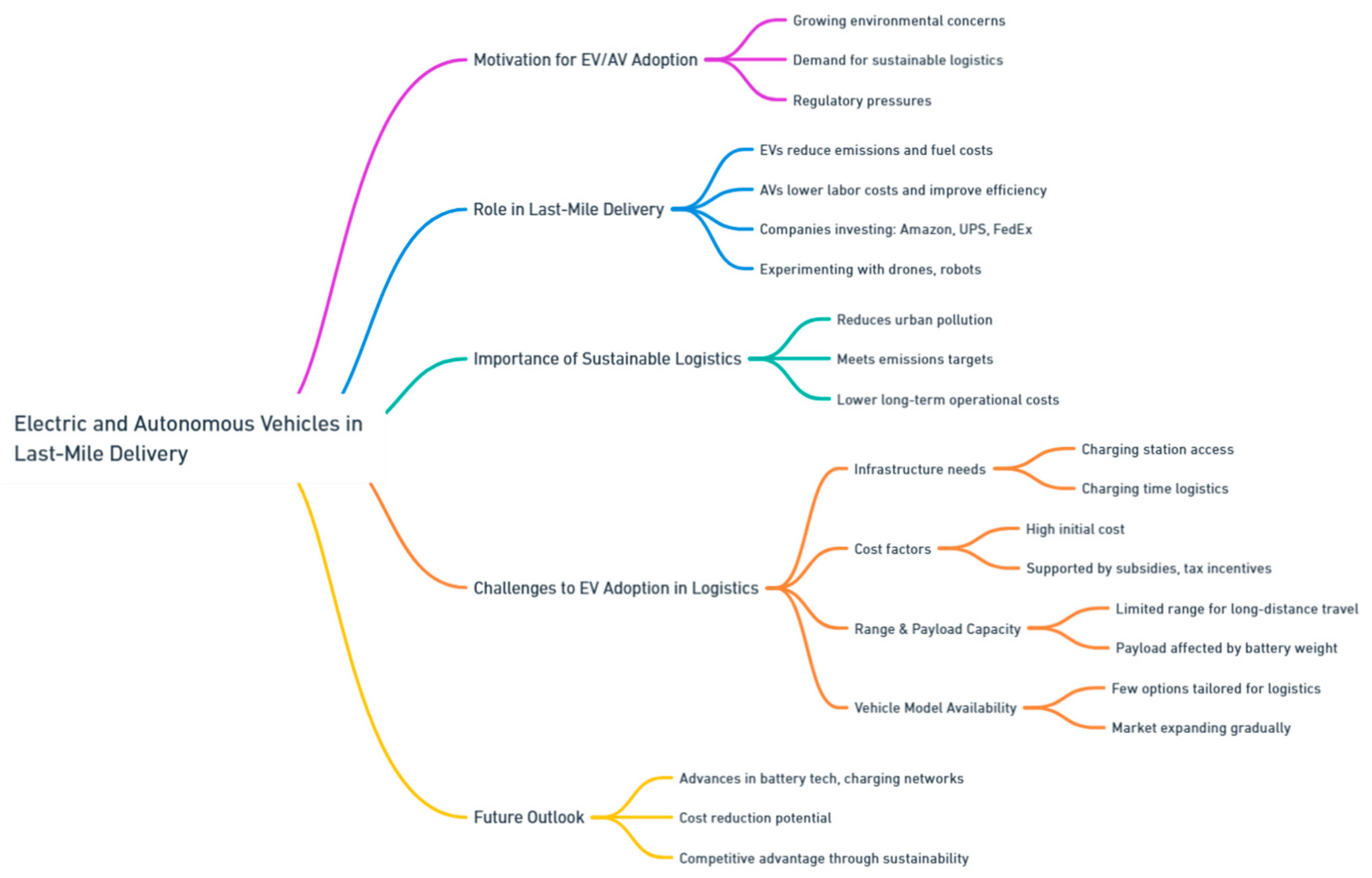

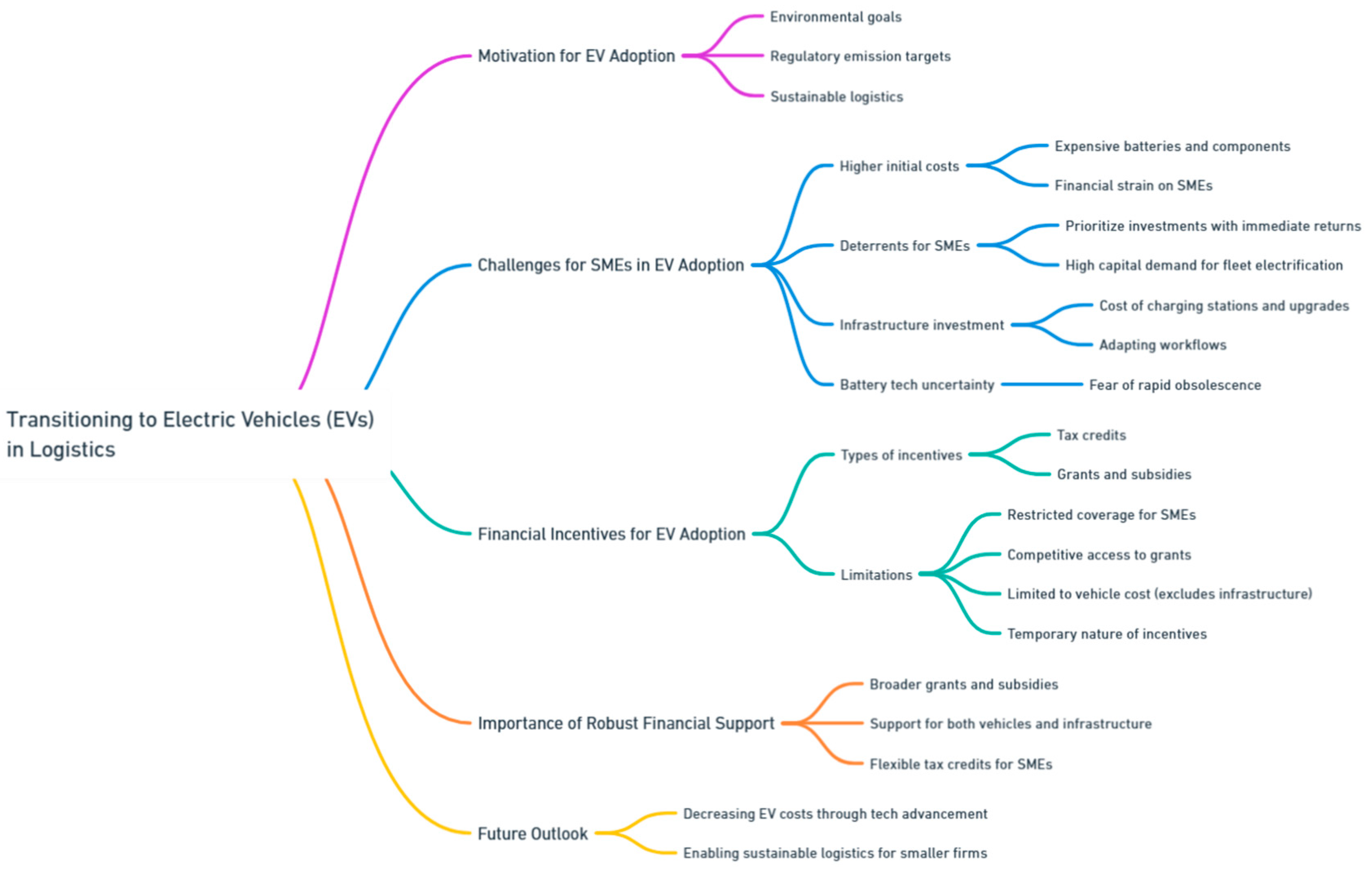

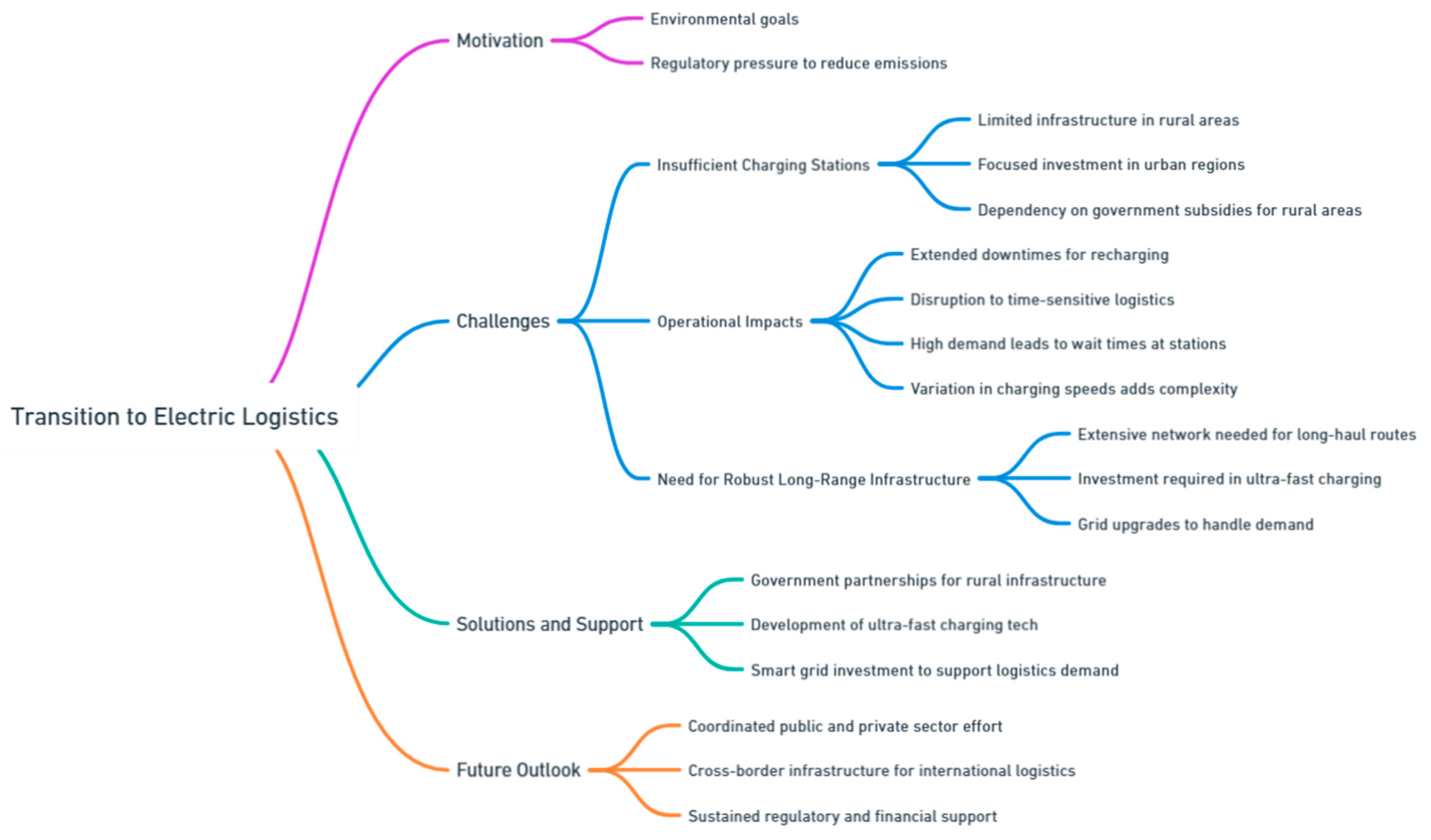

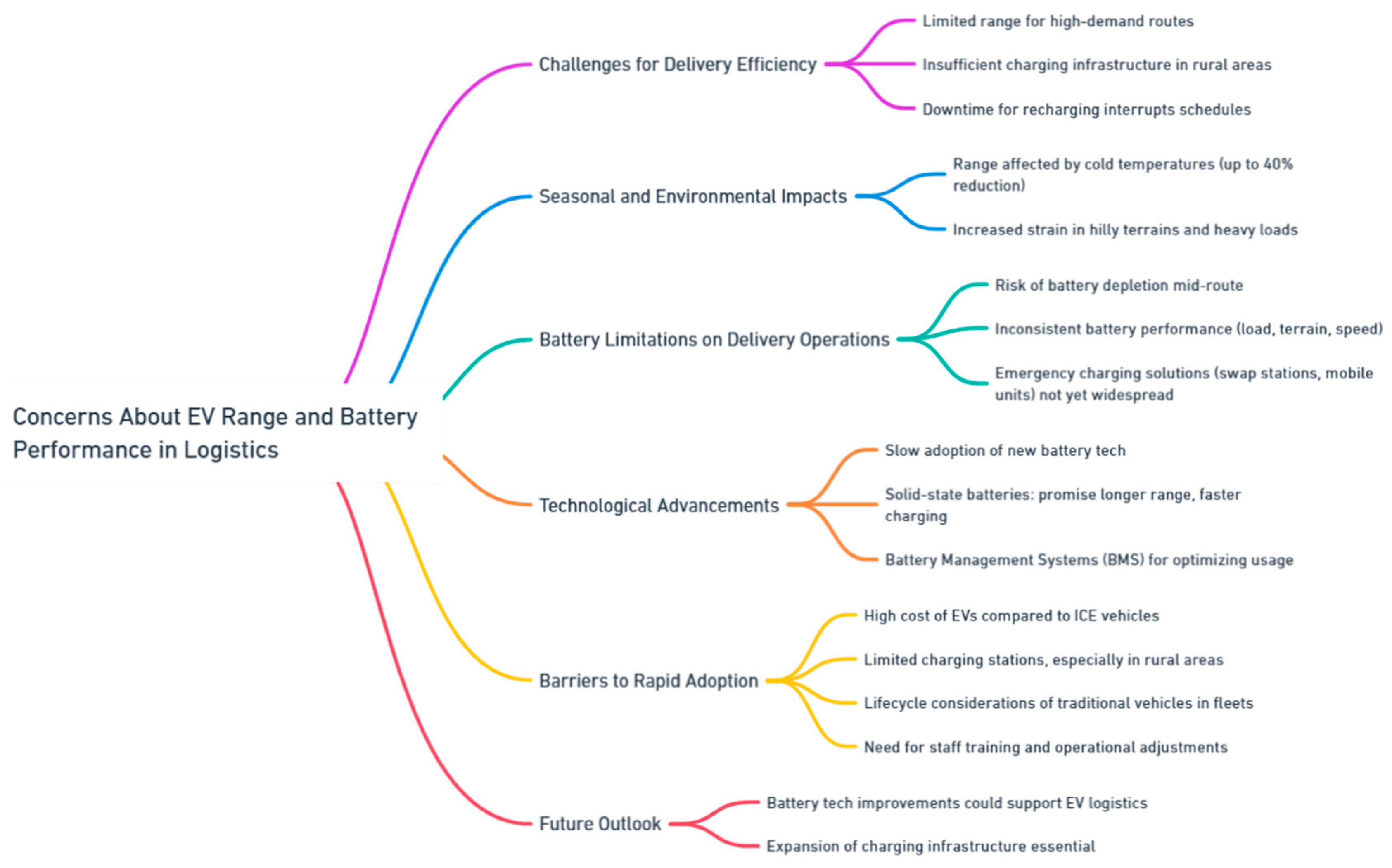

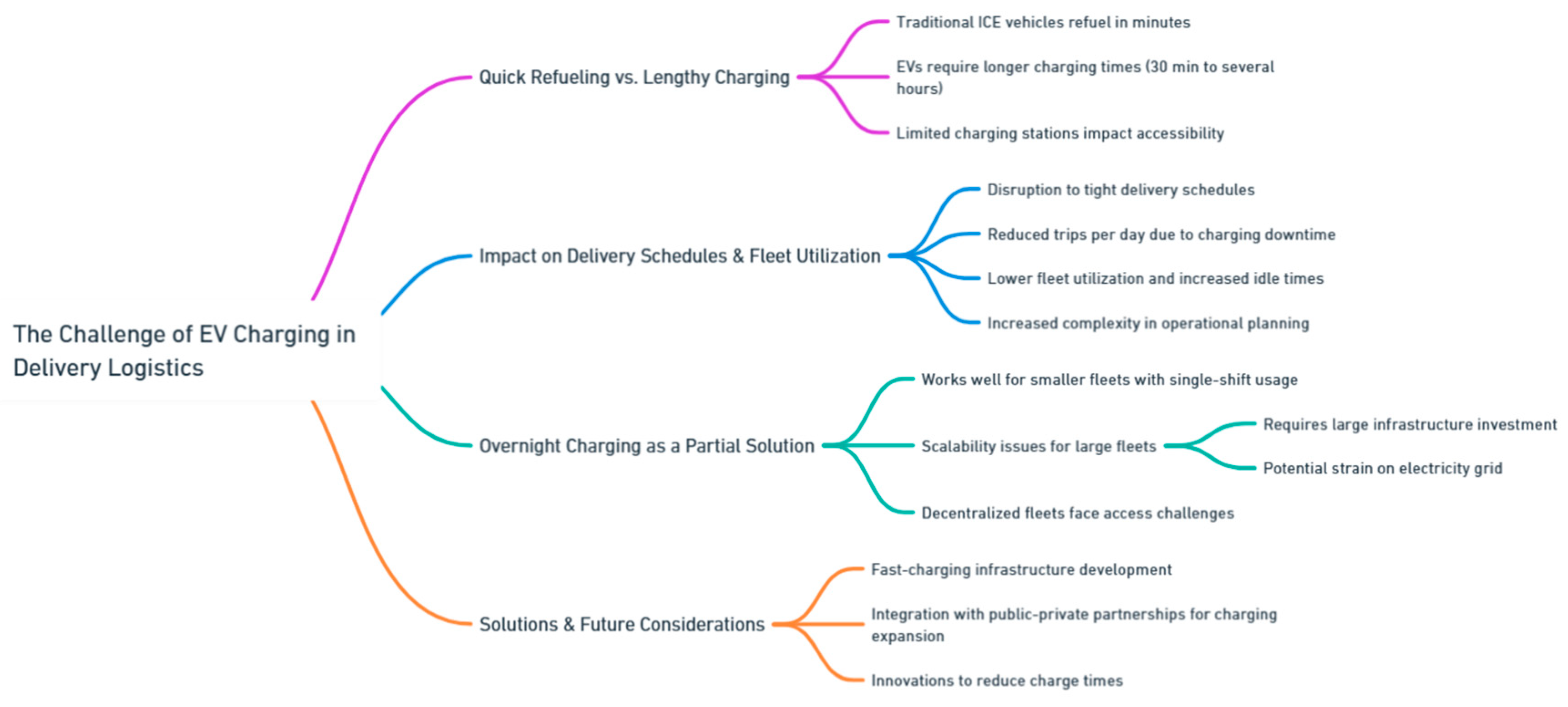

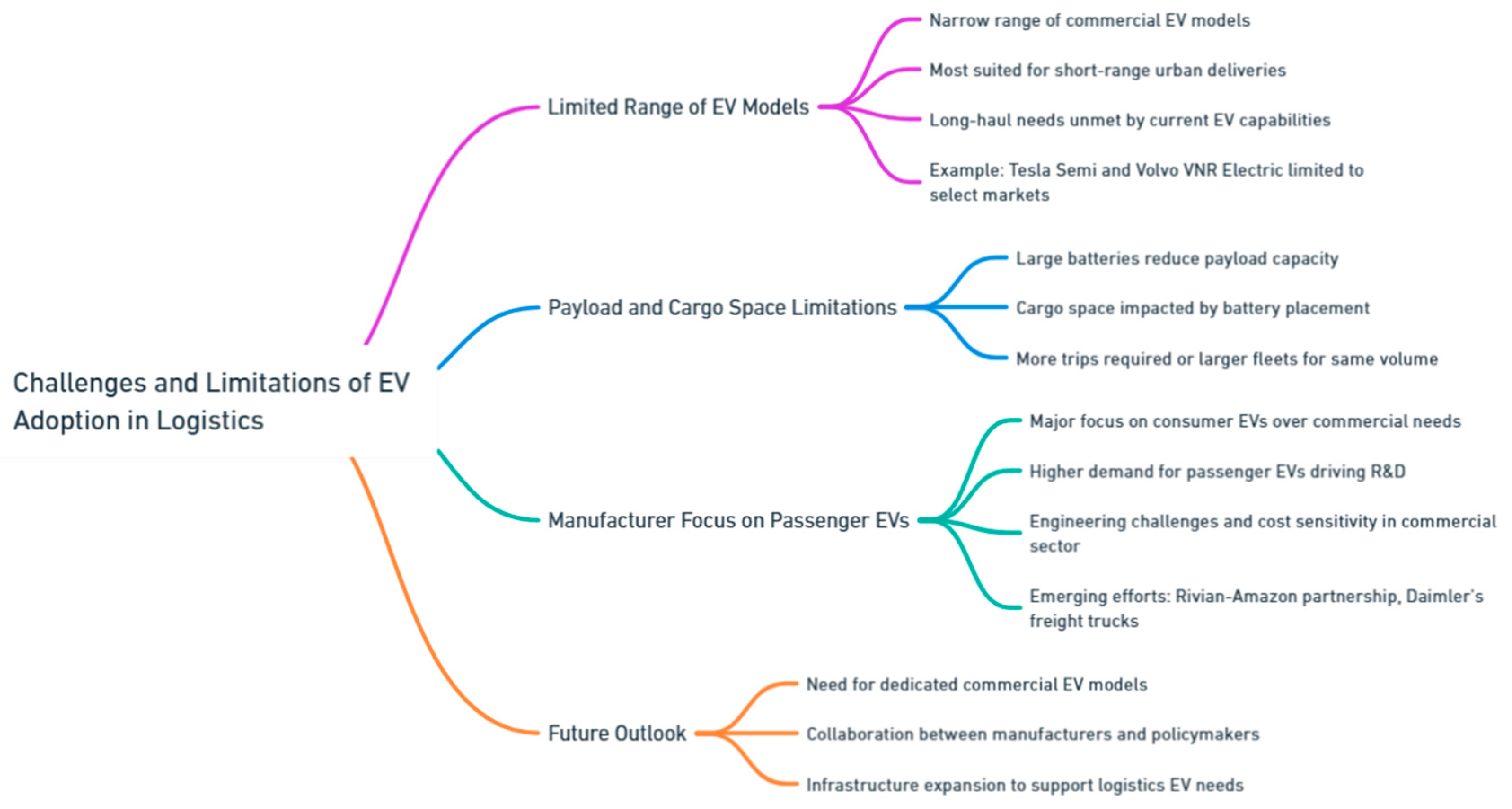

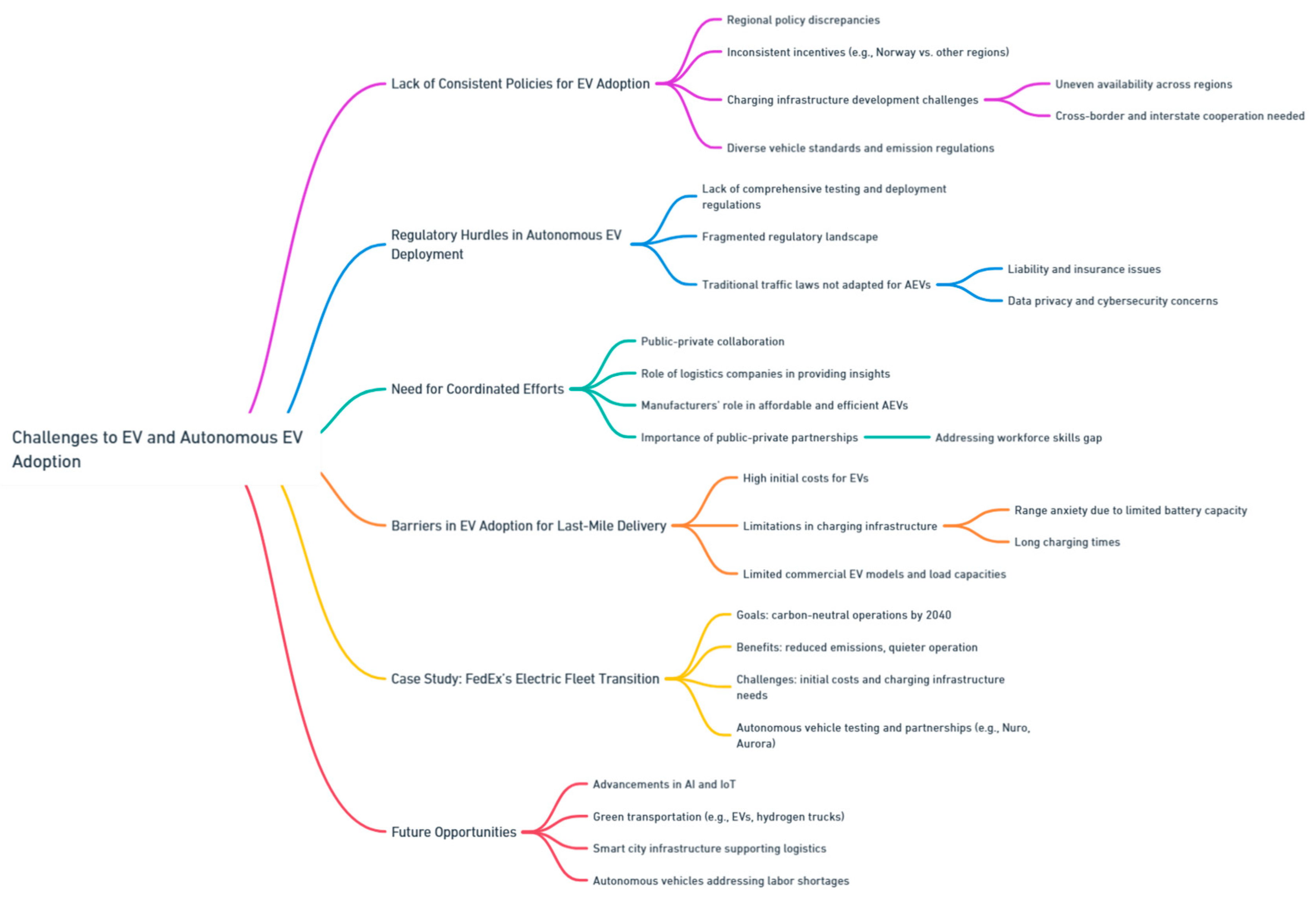

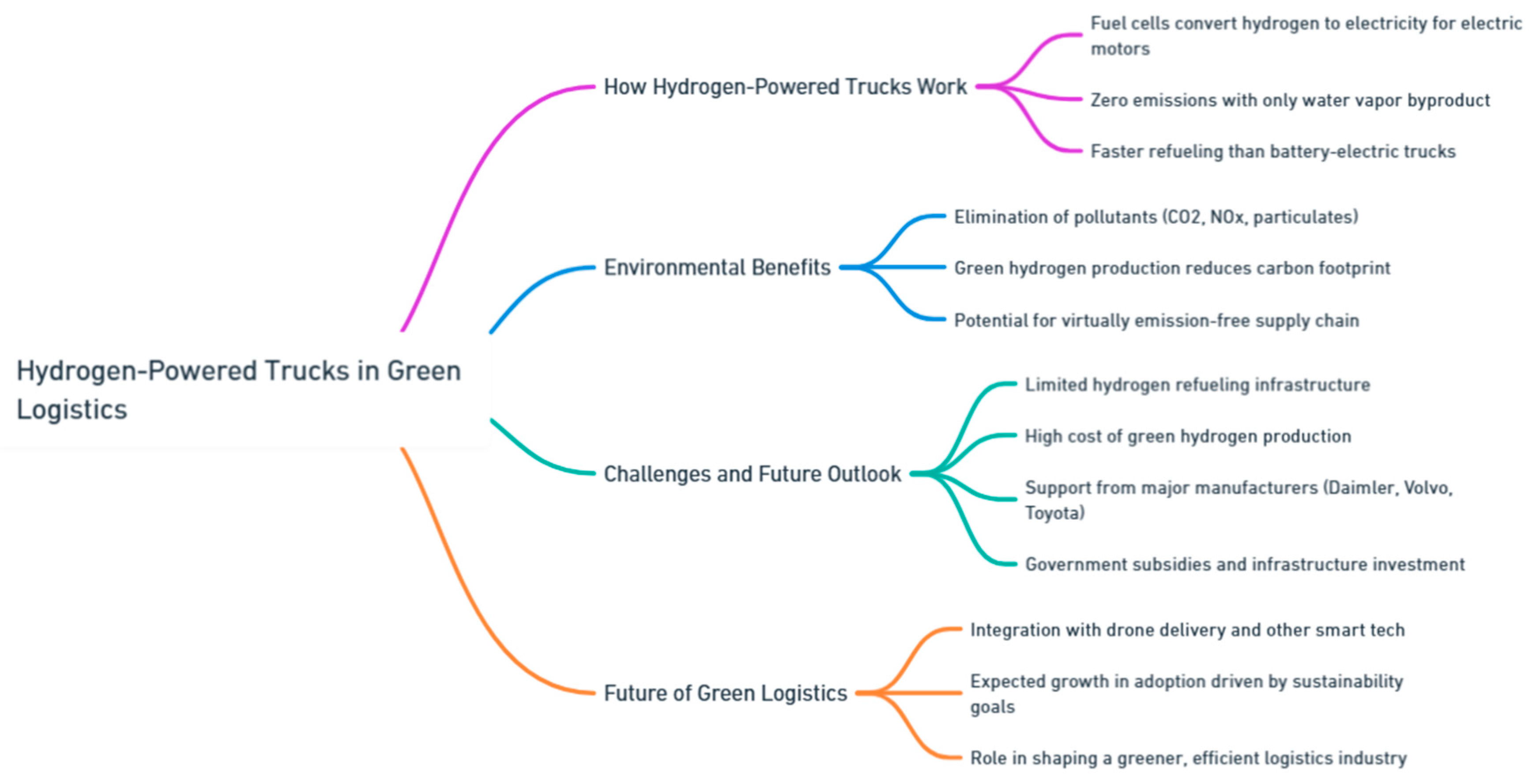

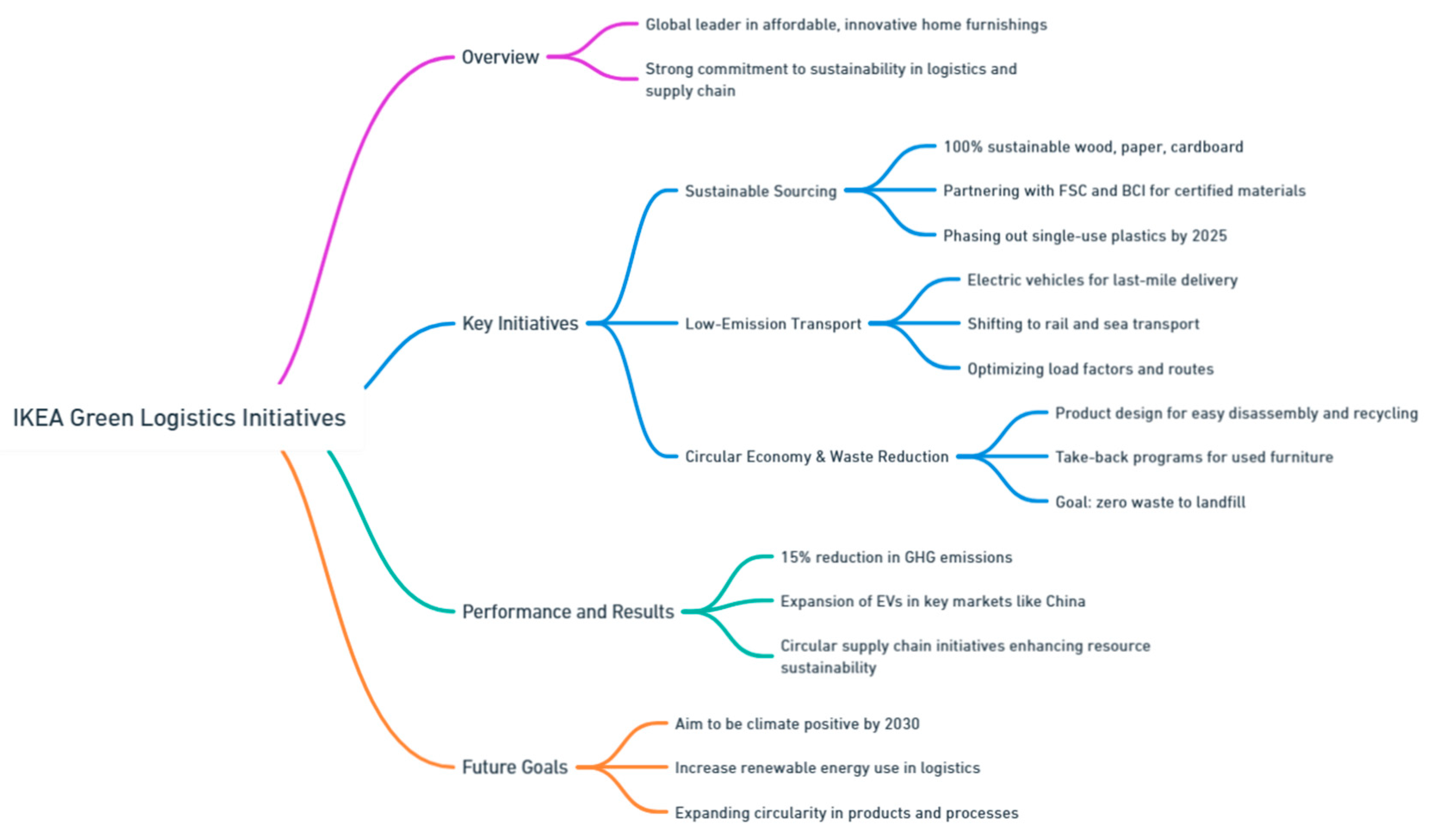

- Electric Vehicles (EVs) and Alternative Fuels. One of the most impactful technologies in reducing logistics-related emissions is the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) and alternative fuel-powered transport. EVs produce zero tailpipe emissions, offering a cleaner alternative to diesel-powered trucks. Many logistics companies, particularly in urban areas, are shifting toward electric delivery vans, which are ideal for short-distance deliveries. Additionally, alternative fuels such as biofuels, hydrogen, and compressed natural gas (CNG) are being integrated into fleets, reducing reliance on traditional fossil fuels. These vehicles help logistics companies reduce both their operational costs and carbon emissions (Qian and Li, 2023; Anosike,et al., 2023).

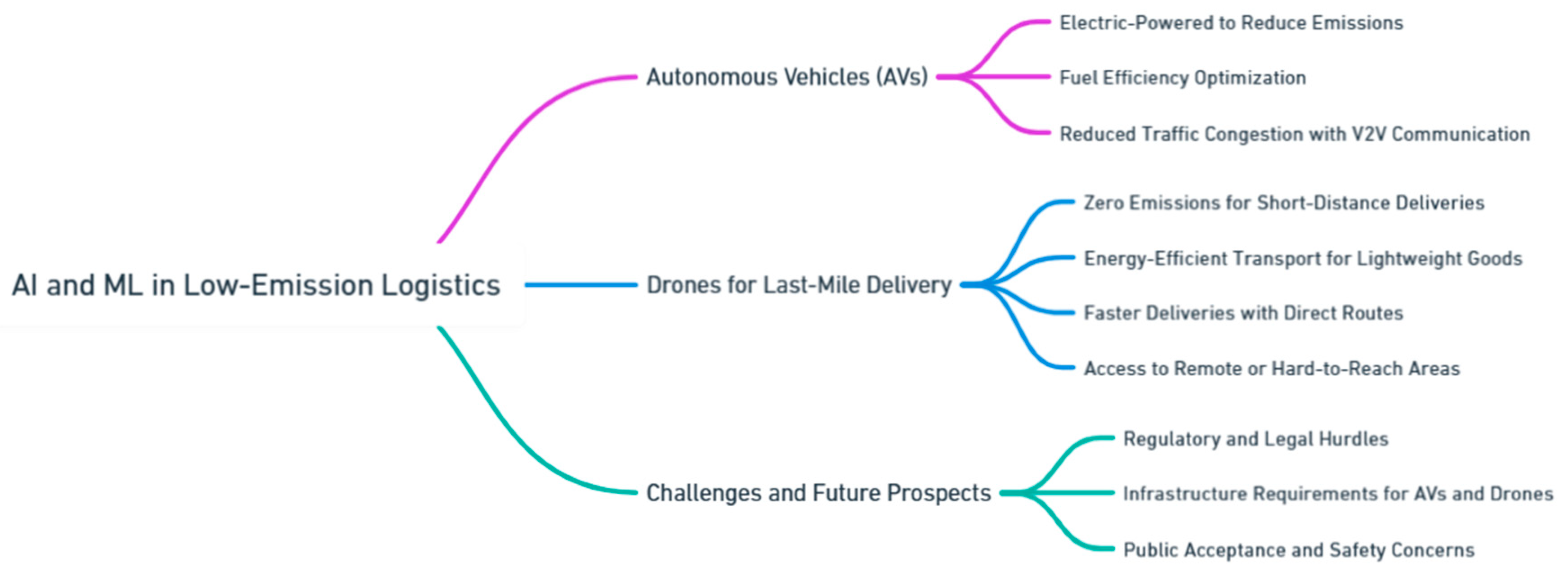

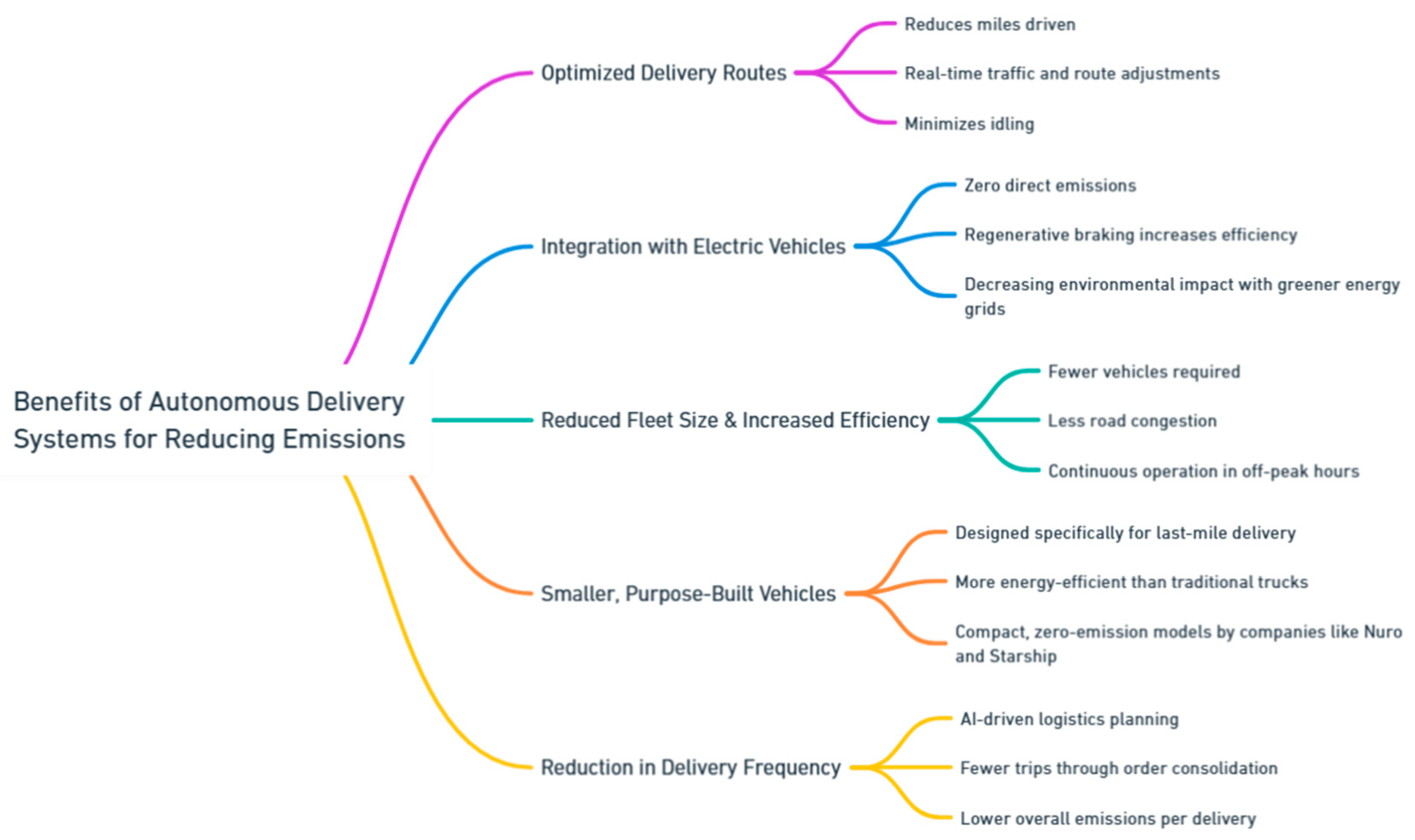

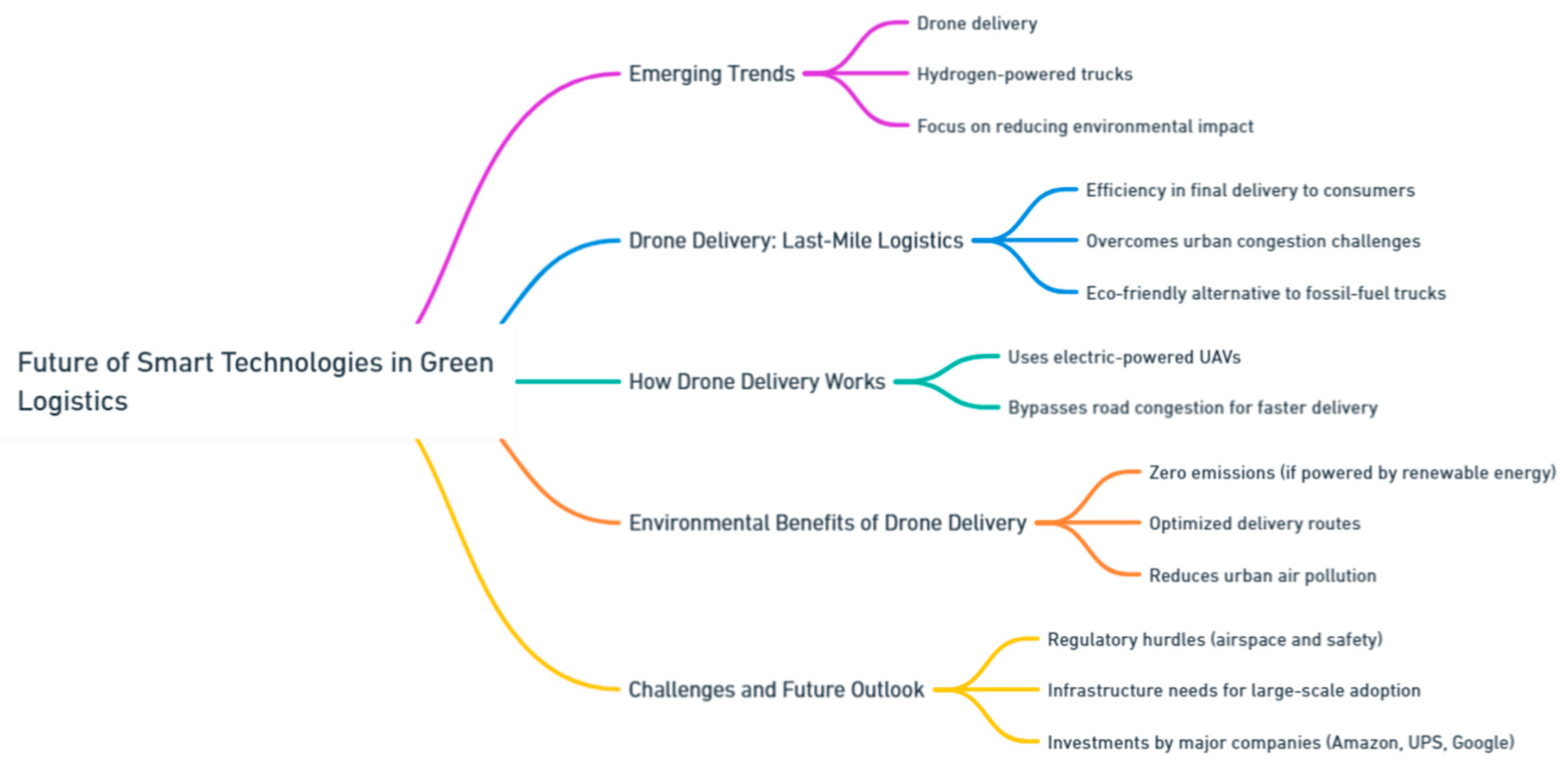

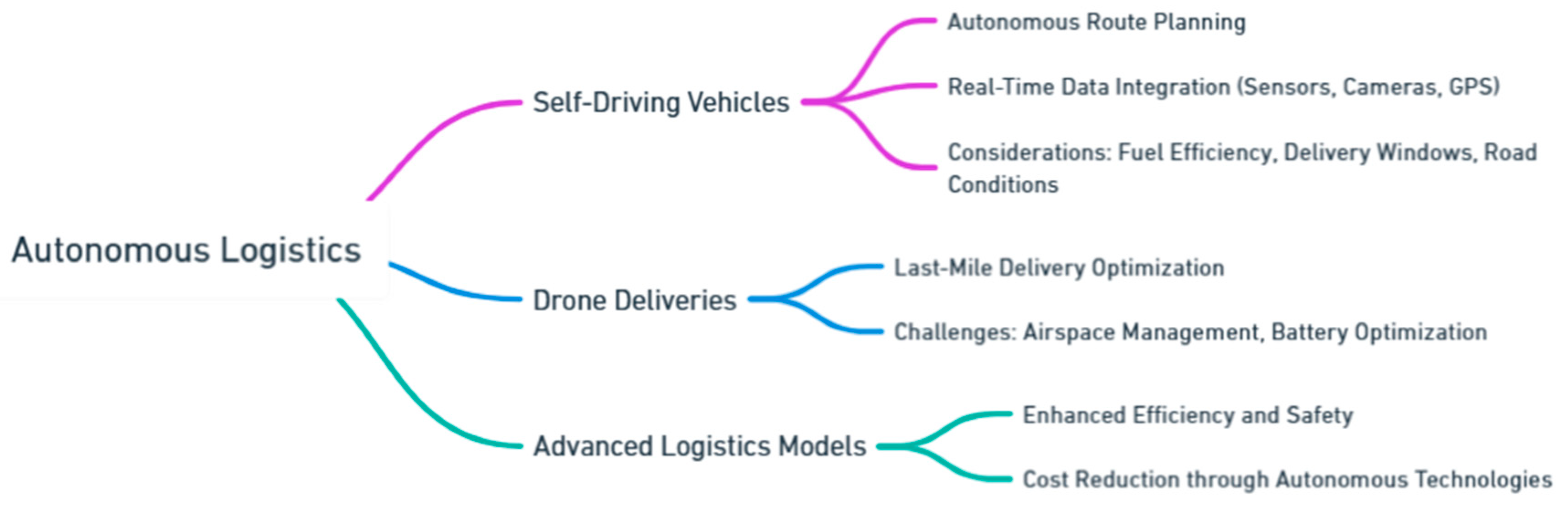

- Autonomous Vehicles and Drones. Autonomous vehicles and drones represent a major shift toward reducing emissions in logistics by enabling more efficient and optimized delivery processes. Autonomous trucks, for example, can be programmed to drive in fuel-efficient manners, avoiding traffic and optimizing routes to save fuel. Drones, especially for last-mile deliveries, are becoming a viable option for light and short-distance deliveries. Since drones operate on electric batteries, they help reduce the carbon footprint in urban delivery networks, especially for e-commerce deliveries (Nurgaliev, et al., 2023; Figliozzi, 2020).

- Route Optimization Software. Route optimization software plays a crucial role in cutting emissions by calculating the most efficient delivery routes. Using real-time data on traffic conditions, weather, and road closures, these systems enable logistics companies to minimize fuel consumption by reducing unnecessary detours and idle time. The software uses advanced algorithms to group deliveries based on proximity and urgency, ensuring that delivery fleets operate at maximum efficiency. This not only reduces fuel usage but also improves delivery times and reduces costs (Tao et al., 2023; Shi et al., 2020).

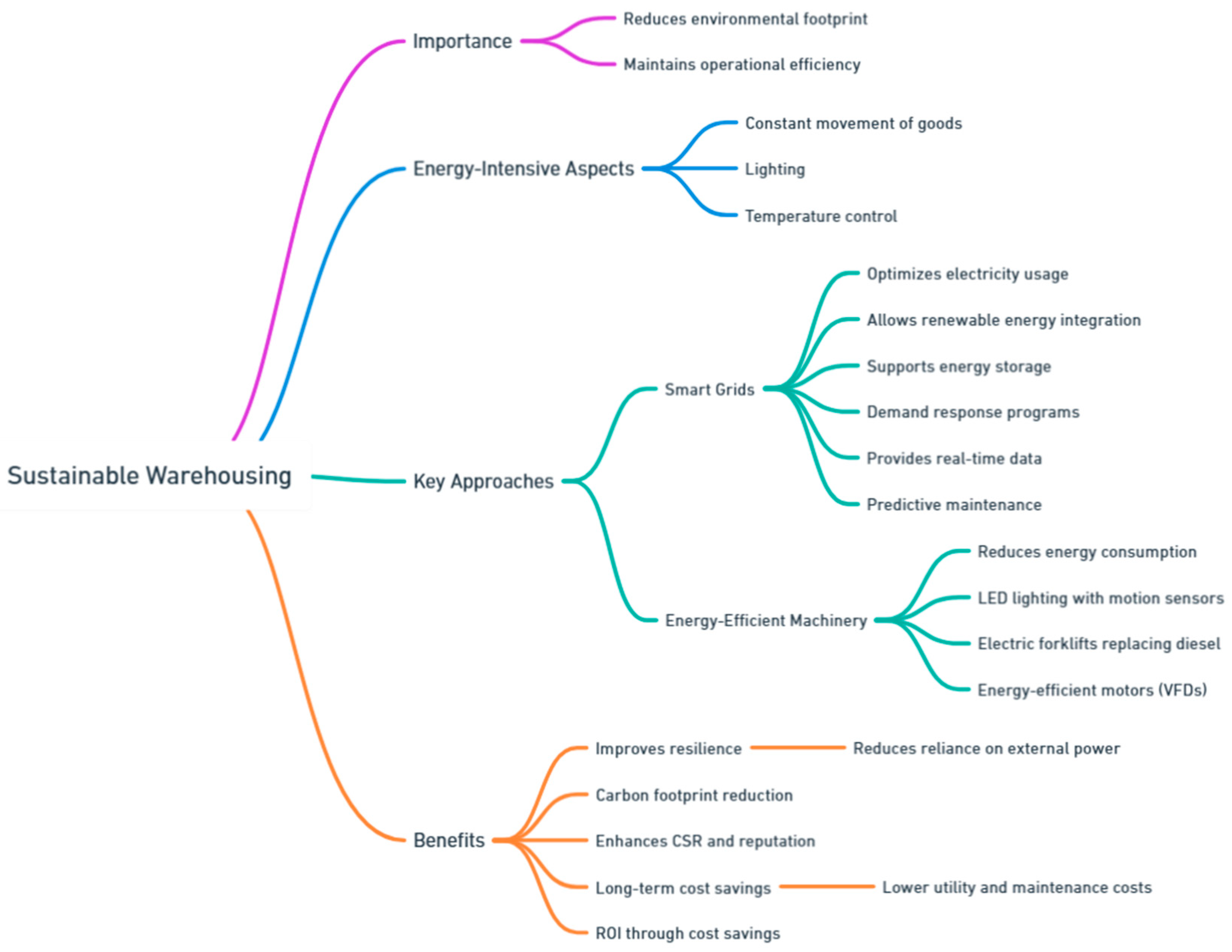

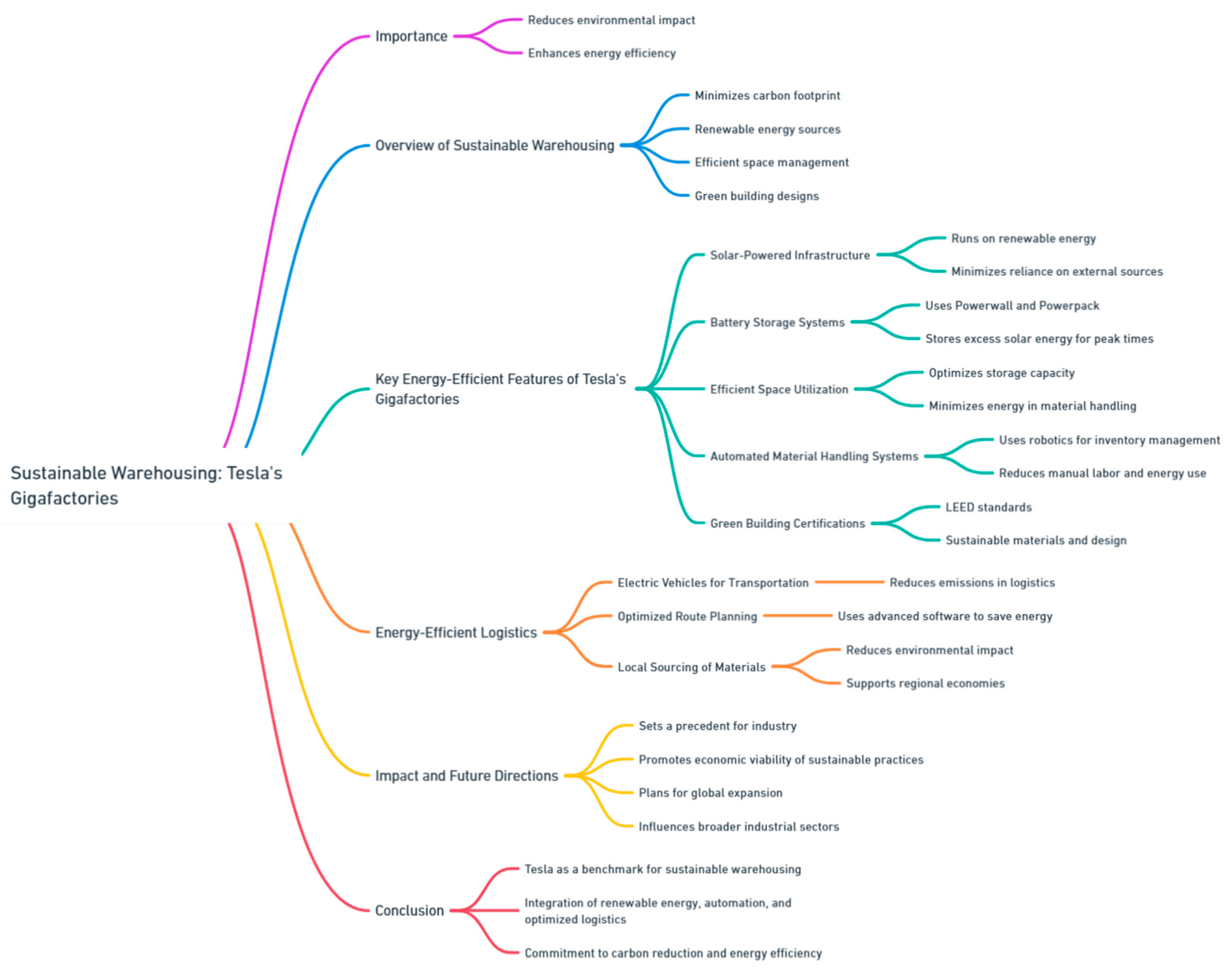

- Smart Warehousing Solutions. Energy efficiency in warehousing is another key area where smart technologies are helping reduce carbon footprints. Smart warehousing solutions use Internet of Things (IoT) sensors, automation, and advanced energy management systems to optimize energy consumption. For instance, IoT sensors can monitor and adjust lighting, temperature, and machinery use in real-time, ensuring that energy is used only when necessary. Automation in picking and packing processes also reduces energy wastage by minimizing human error and speeding up operations (Metallidou et al., 2020; Yar et al., 2021).

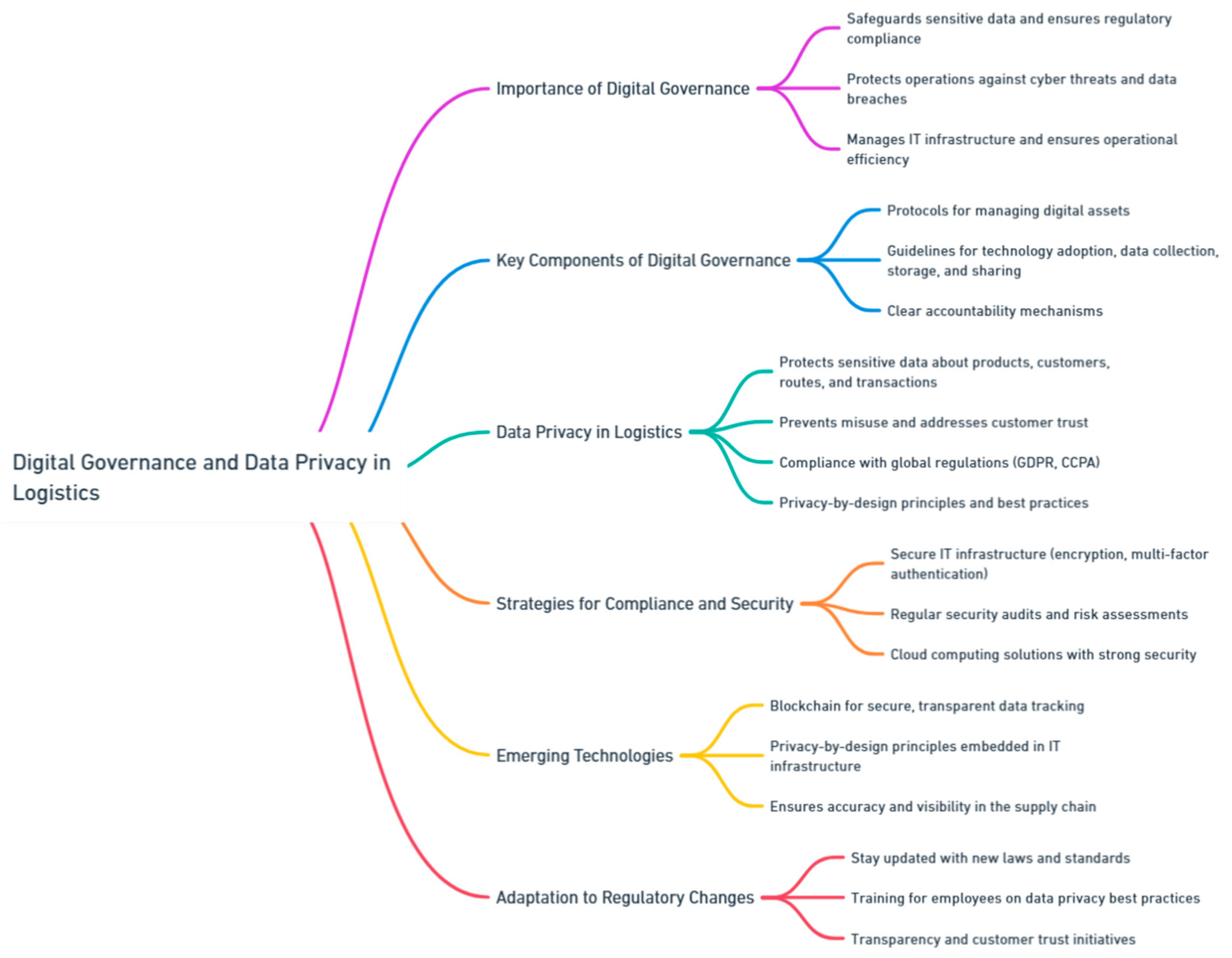

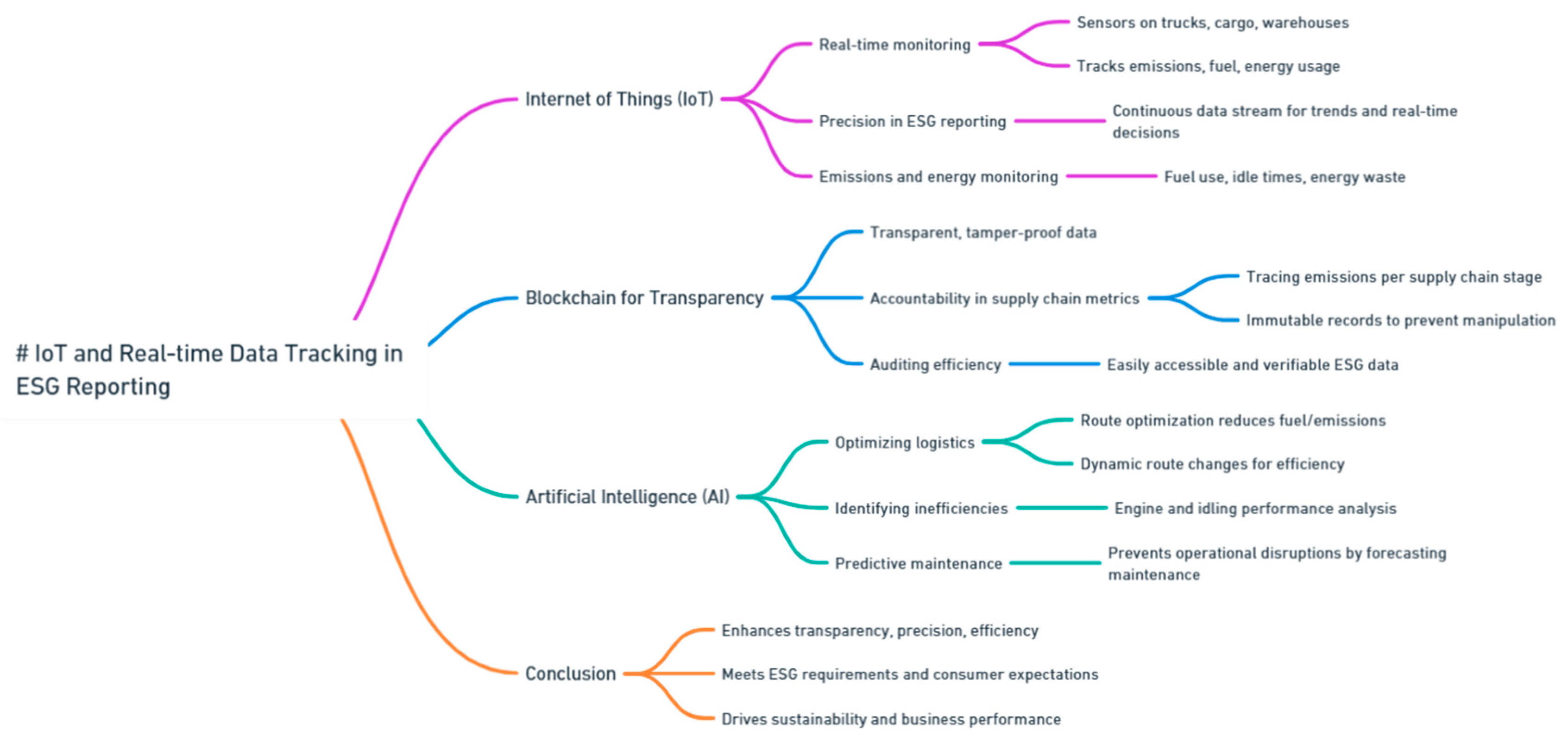

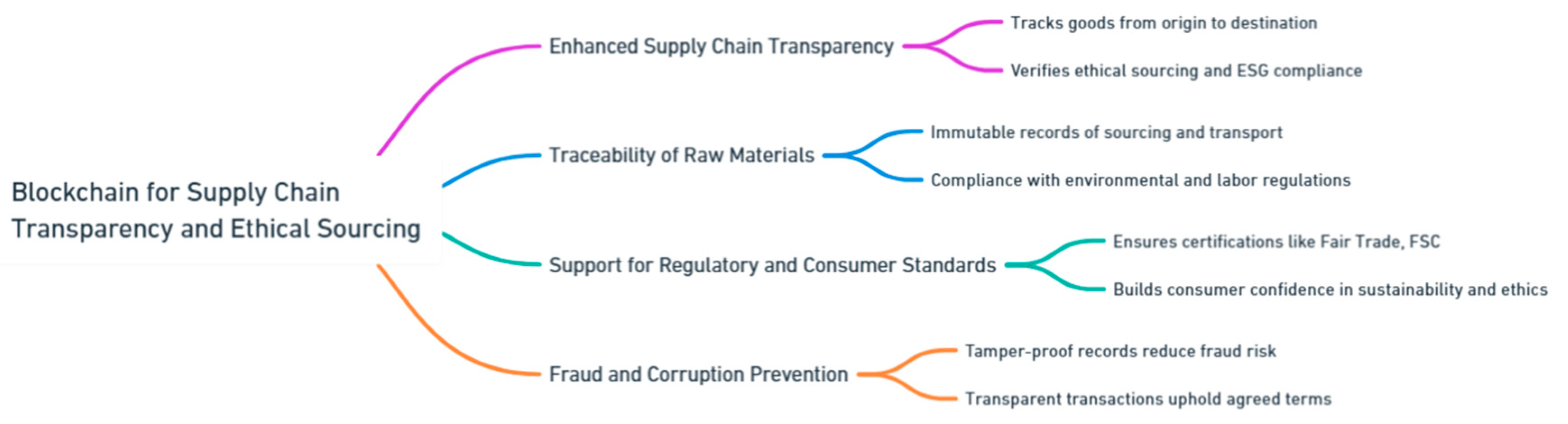

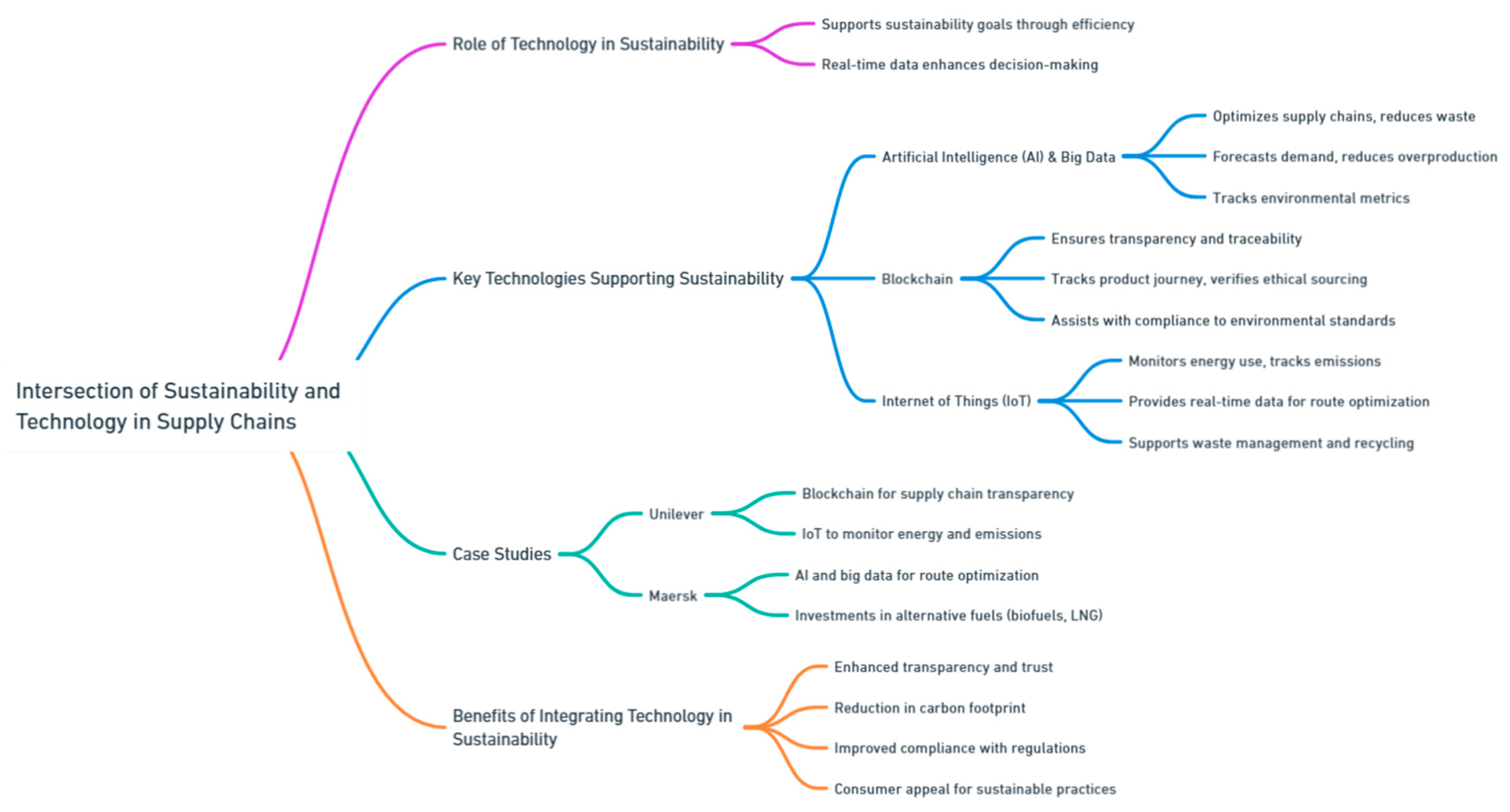

- Blockchain for Supply Chain Transparency. Blockchain technology is being utilized to increase transparency and traceability in logistics operations. By providing an immutable record of every step in the supply chain, blockchain helps companies identify inefficiencies and areas where emissions can be reduced. For example, blockchain can track the carbon emissions associated with each shipment, allowing companies to pinpoint emission-heavy processes and address them with more sustainable alternatives (Centobelli et al., 2022; Sunny et al., 2020).

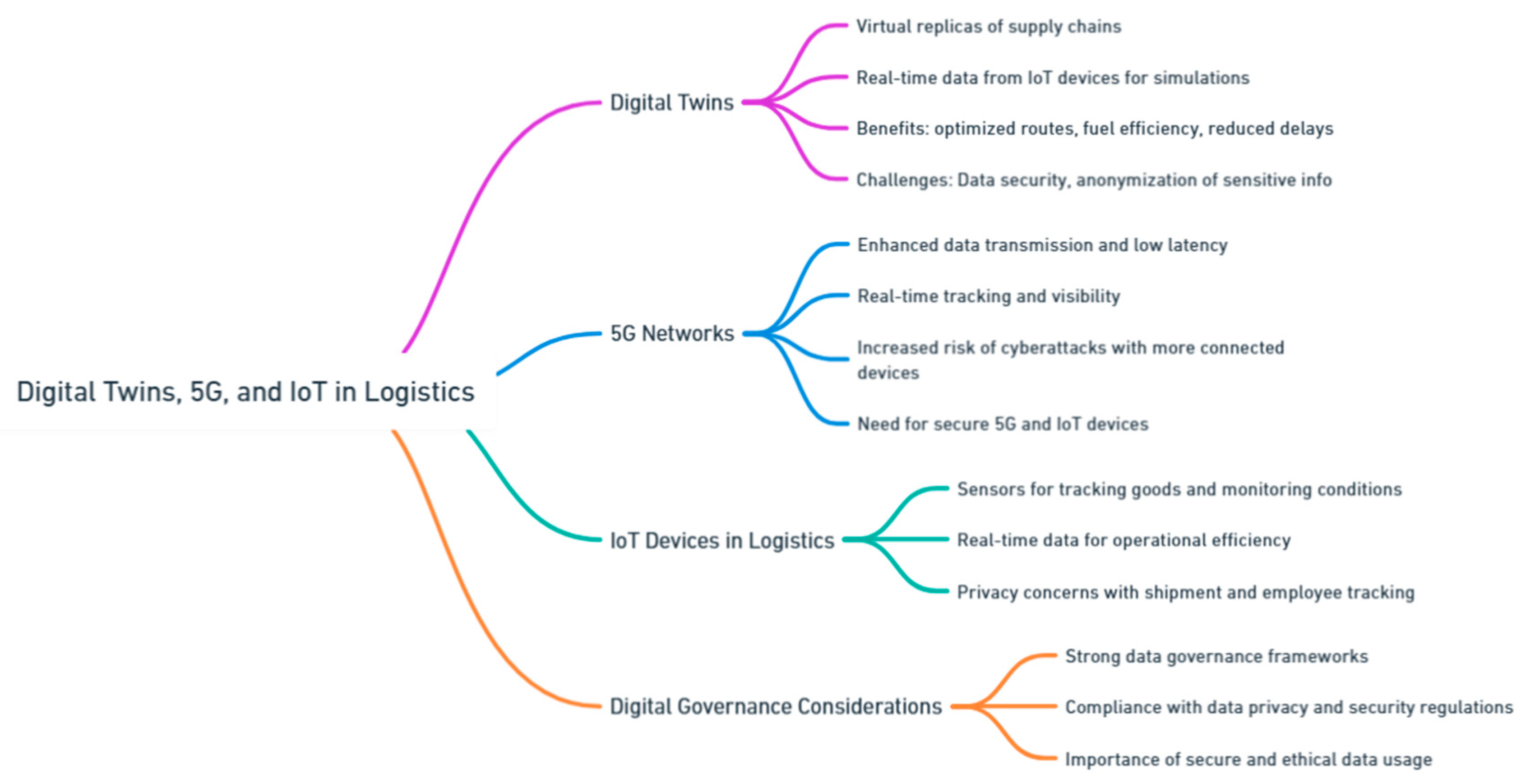

- Digital Twins and Predictive Analytics. Digital twins, which are virtual models of physical logistics systems, allow companies to simulate and predict the impact of different strategies on emissions. By analyzing various operational scenarios, logistics managers can predict how changes in transport routes, warehousing practices, or fleet composition will affect the overall carbon footprint. Predictive analytics further assists by forecasting demand and optimizing inventory management, which can lead to fewer shipments and reduced energy consumption. Reducing the carbon footprint in logistics through smart technologies is not only a necessity for mitigating climate change but also a strategic move for businesses aiming to improve efficiency and reduce costs. Electric vehicles, autonomous systems, route optimization, smart warehousing, blockchain, and digital twins all contribute to creating a more sustainable logistics sector. As these technologies continue to evolve and become more accessible, the logistics industry can significantly reduce its environmental impact while maintaining operational excellence. This transformation is crucial for aligning with global sustainability goals and meeting the increasing demand for eco-friendly logistics solutions (Park and Yang, 2020; Moshood, et al., 2021).

4.1.2. Importance of Sustainability in Supply Chains

4.1.3. Introduction of Smart Technologies as a Solution

4.1.4. Smart Technologies Offer Efficient, Scalable Methods to Reduce the Logistics Sector's Carbon Footprint, Contributing to Sustainable Development

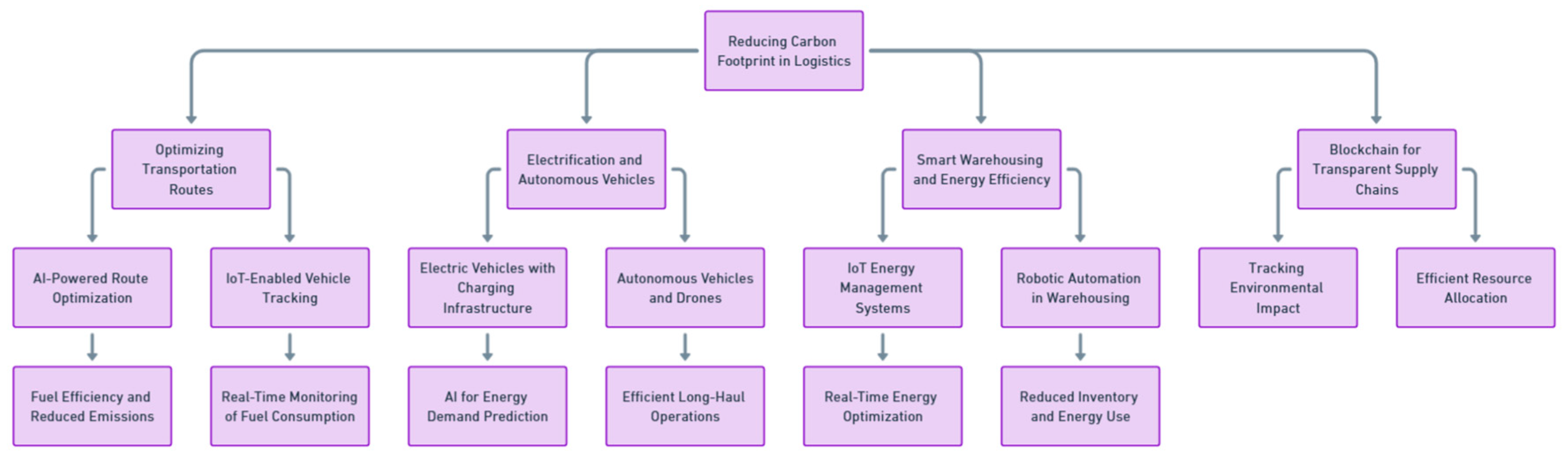

4.2. Reducing Carbon Footprint Through Smart Technologies

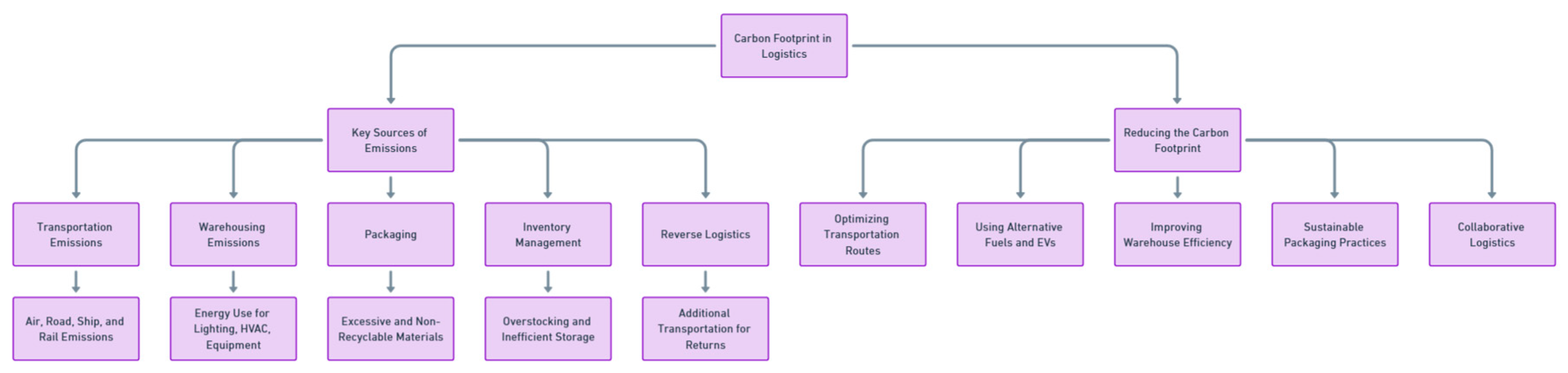

4.2.1. Definition of Carbon Footprint in Logistics

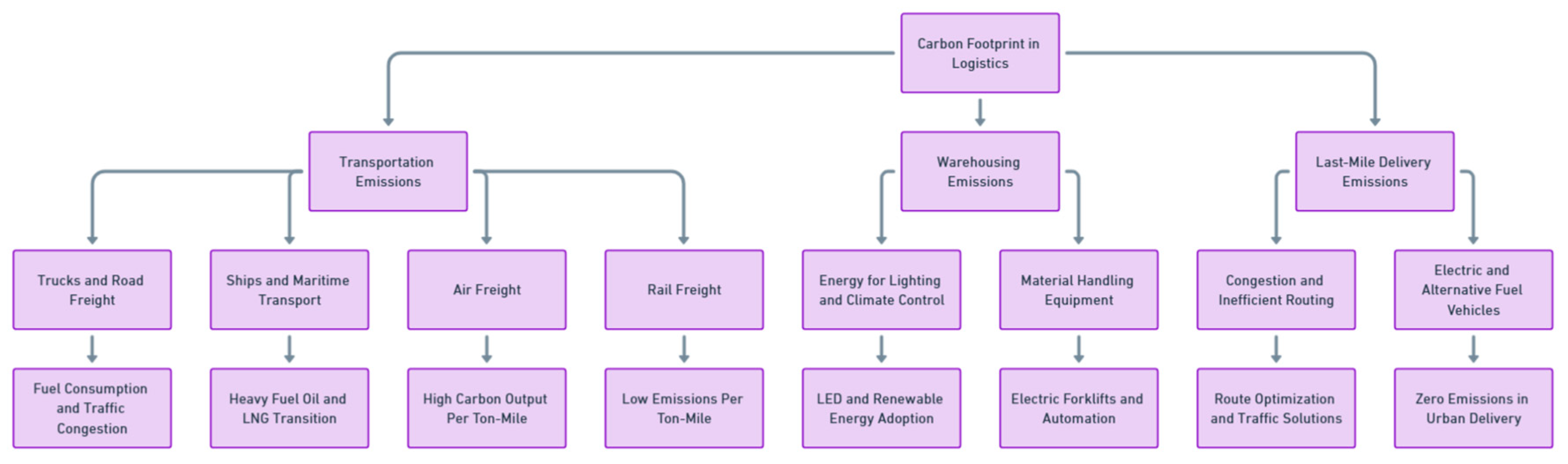

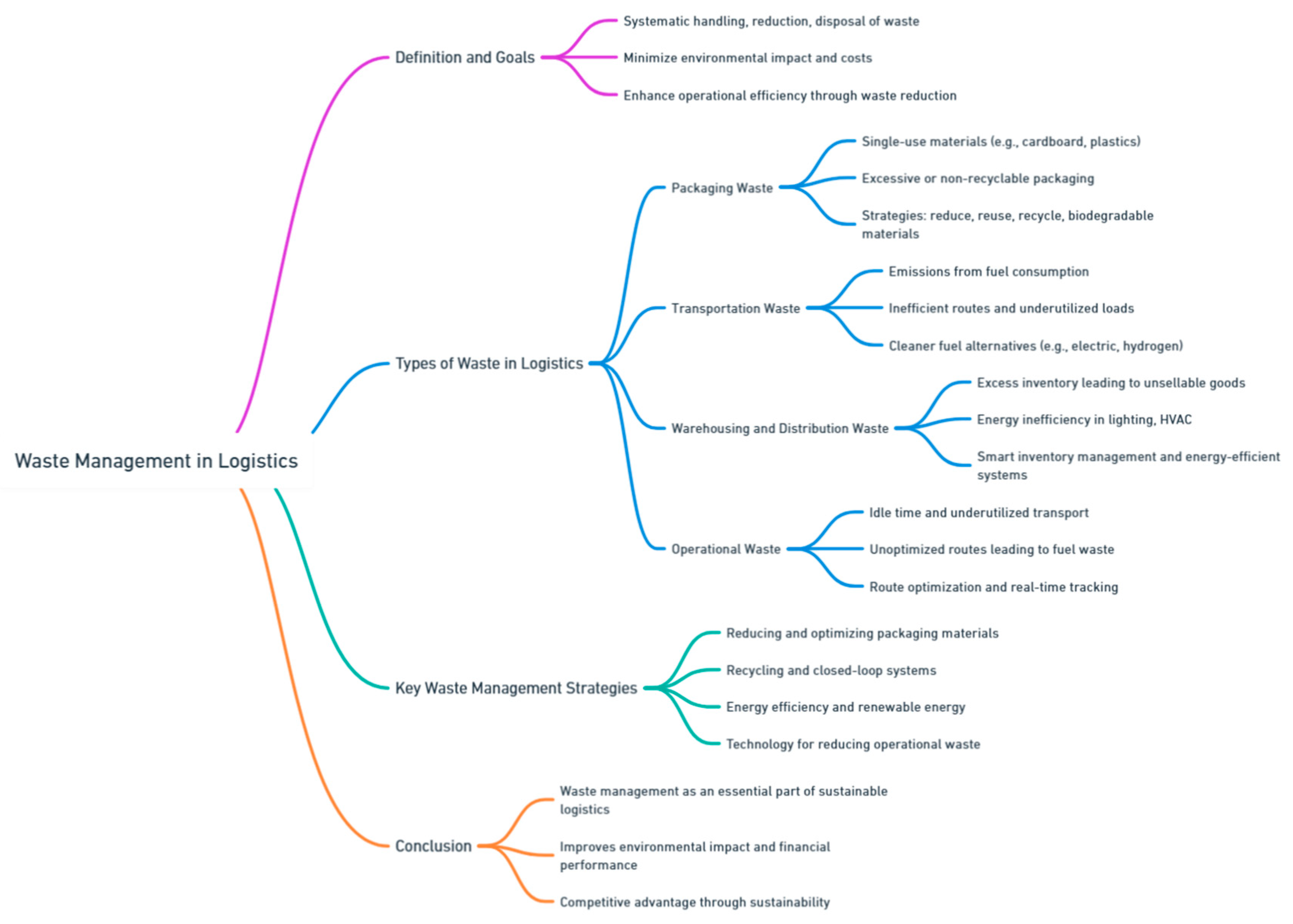

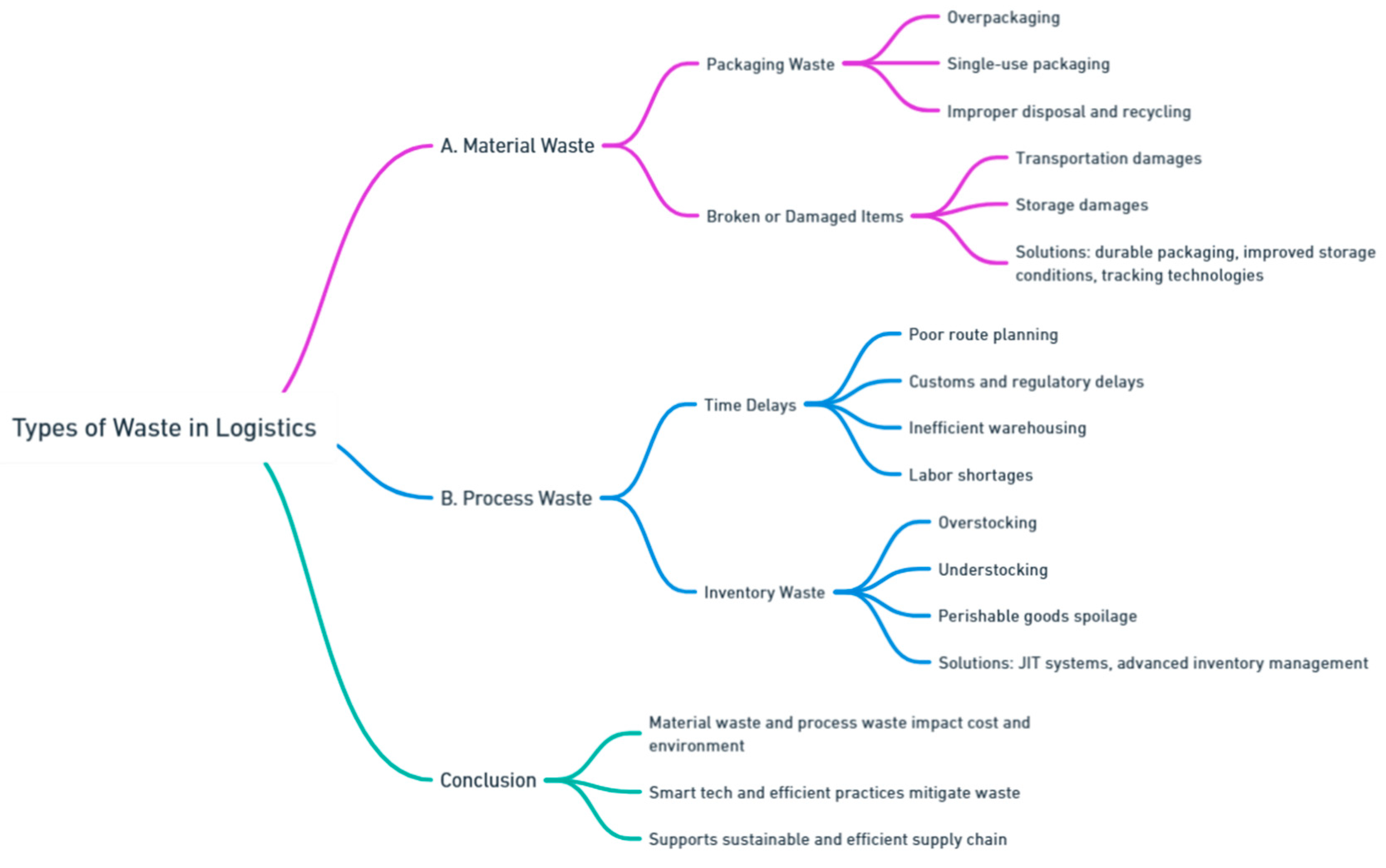

- Transportation: This is the largest contributor to carbon emissions in logistics. The transportation of goods by trucks, ships, planes, and trains consumes vast amounts of fossil fuels. Among these, air freight is the most carbon-intensive, while ocean and rail transport tend to be more energy-efficient. However, road transportation is the most commonly used mode of transport for shorter distances and last-mile delivery, making it a significant contributor to overall emissions.

- Warehousing: Logistics involves the storage of goods in warehouses or distribution centers before they reach their final destination. The operation of these facilities requires substantial energy, especially for lighting, climate control, and material handling equipment. Depending on the size and energy efficiency of the warehouse, the carbon footprint can vary significantly.

- Packaging: Packaging is another significant factor in the carbon footprint of logistics. Excessive or non-recyclable packaging materials contribute to waste and require additional energy for production and disposal. Moreover, packaging affects the volume and weight of goods during transportation, influencing fuel consumption.

- Inventory Management: Inefficient inventory management can lead to overstocking or underutilization of storage space, which increases energy use in warehouses. Poor management of goods can also result in additional transportation, further increasing emissions.

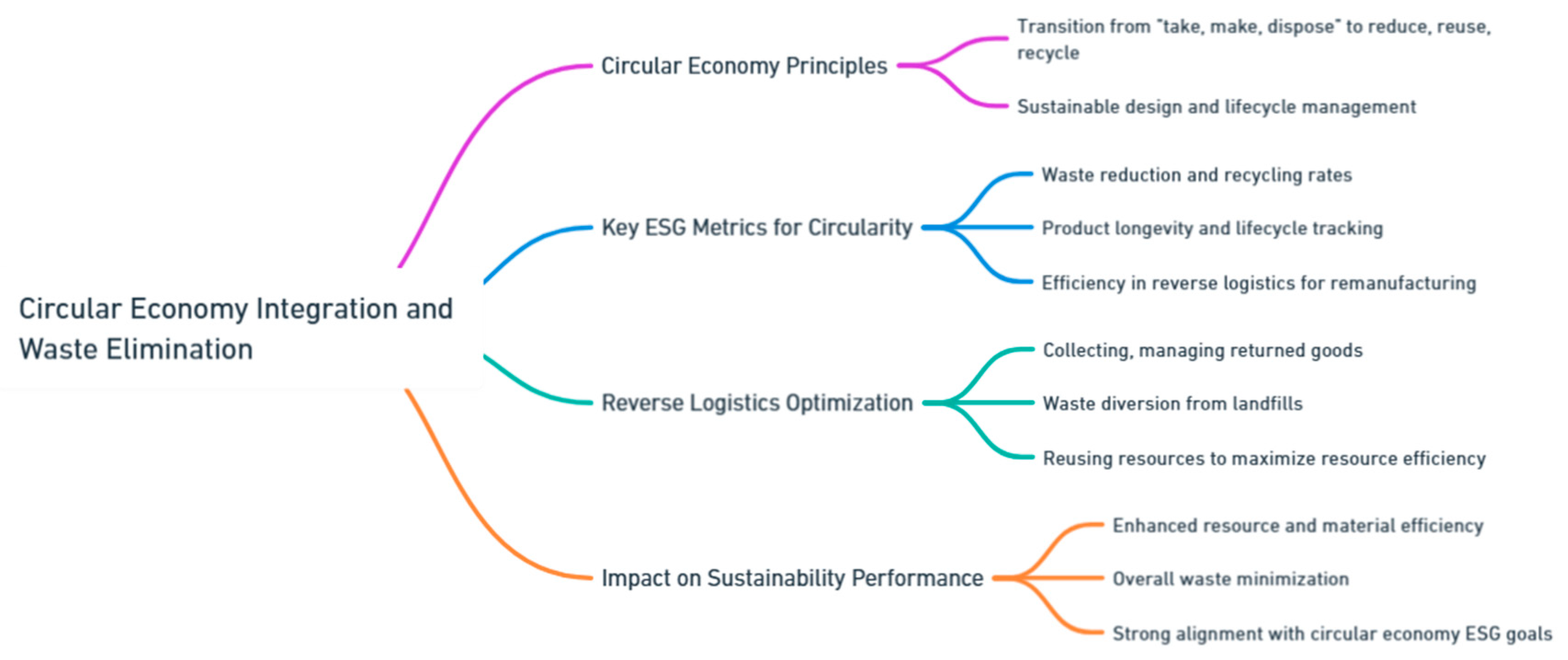

- Reverse Logistics: The process of returning goods, also known as reverse logistics, generates additional transportation and handling, which can add to the carbon footprint. This often includes the transportation of defective or unwanted products back to manufacturers or sellers, as well as the recycling or disposal of packaging materials.

- Optimizing Transportation Routes and Modes: One of the most effective ways to reduce emissions in logistics is by optimizing transportation routes and choosing more energy-efficient modes of transport. Route optimization software can help companies reduce the distance traveled by vehicles, leading to lower fuel consumption and emissions. Additionally, shifting from road transport to rail or sea for long-distance shipments can significantly cut emissions, as these modes are more energy-efficient per ton-mile of goods moved.

- Using Alternative Fuels and Electric Vehicles: The adoption of alternative fuels, such as biofuels, hydrogen, and electricity, is gaining traction in the logistics sector. Electric vehicles (EVs), in particular, are being increasingly used for last-mile deliveries, which reduces emissions in densely populated urban areas. While the widespread adoption of EVs in logistics is still in its early stages, it holds significant potential for reducing the sector's carbon footprint.

- Improving Warehouse Efficiency: Warehouses and distribution centers can reduce their carbon footprint by improving energy efficiency. Installing energy-efficient lighting, using renewable energy sources like solar panels, and implementing smart climate control systems can significantly reduce energy consumption. Additionally, automating warehouse operations with robotics and AI can optimize space utilization and minimize energy waste.

- Sustainable Packaging Practices: Reducing the use of non-recyclable materials, minimizing packaging waste, and designing packaging to be lighter and more compact can help reduce emissions in logistics. Reusable packaging materials, such as crates and pallets, are also being used more widely to decrease waste and transportation emissions.

- Collaborative Logistics: Companies can reduce their carbon footprint by collaborating with other businesses to share transportation resources and consolidate shipments. This approach, known as collaborative logistics, allows companies to maximize the use of transportation assets, such as trucks or shipping containers, thereby reducing the number of trips and lowering emissions.

4.2.2. Key Sources: Transportation, Warehousing, and Last-Mile Delivery

- Trucks and Road Freight: Road freight, particularly through trucks, is one of the most widely used forms of transportation in logistics. This is especially true for domestic and regional shipments, where trucks are often relied upon for last-mile delivery and shorter routes. However, trucks are highly reliant on fossil fuels, particularly diesel, which results in significant greenhouse gas emissions. As trucks operate over long distances or in urban areas, their carbon footprint increases due to fuel consumption and traffic congestion.

- Ships and Maritime Transport: Shipping is a more efficient mode of transport in terms of emissions per ton of cargo moved, making it a preferred option for international trade and long-distance shipping. However, due to the vast scale of global shipping operations, the total emissions from maritime transport are still substantial. Large container ships often burn heavy fuel oil, a particularly carbon-intensive fossil fuel, contributing to a significant portion of global emissions. There are ongoing efforts to reduce emissions in this sector by adopting cleaner technologies such as liquefied natural gas (LNG) or electric propulsion.

- Air Freight: Air transportation is the most carbon-intensive mode of logistics transport. While air freight accounts for a smaller portion of total global trade by volume, it is responsible for a disproportionately high percentage of emissions. This is because jet fuel has a higher carbon output per ton-mile than other fuels, and planes are typically used for high-priority, long-distance shipments. The high speed of air transport comes with a steep environmental cost, and efforts to minimize air freight are critical to reducing the logistics industry's carbon footprint.

- Rail Freight: Rail transport is considered one of the most environmentally friendly modes of transportation for moving goods over long distances. Trains, especially those powered by electricity or hybrid systems, produce significantly lower emissions than trucks or airplanes. As a result, many companies are exploring ways to shift freight from road to rail, particularly for bulk goods and raw materials.

- Energy Use for Lighting and Climate Control: Warehouses require extensive lighting to ensure the safe and efficient handling of goods. Many older warehouses still rely on inefficient lighting systems, which consume large amounts of electricity. Climate control, such as heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC), is another major energy consumer. Warehouses dealing with perishable goods often require refrigeration, further increasing their carbon footprint. Transitioning to energy-efficient lighting systems, such as LED, and using renewable energy sources can help reduce emissions from warehousing operations.

- Material Handling Equipment: Forklifts, cranes, and conveyor systems used to move goods within warehouses are typically powered by electricity or fossil fuels. While some facilities have shifted to electric forklifts, others still use diesel-powered equipment, contributing to carbon emissions. Automation and robotics in warehousing have the potential to improve efficiency, but they also require energy, which can increase the carbon footprint if not managed sustainably.

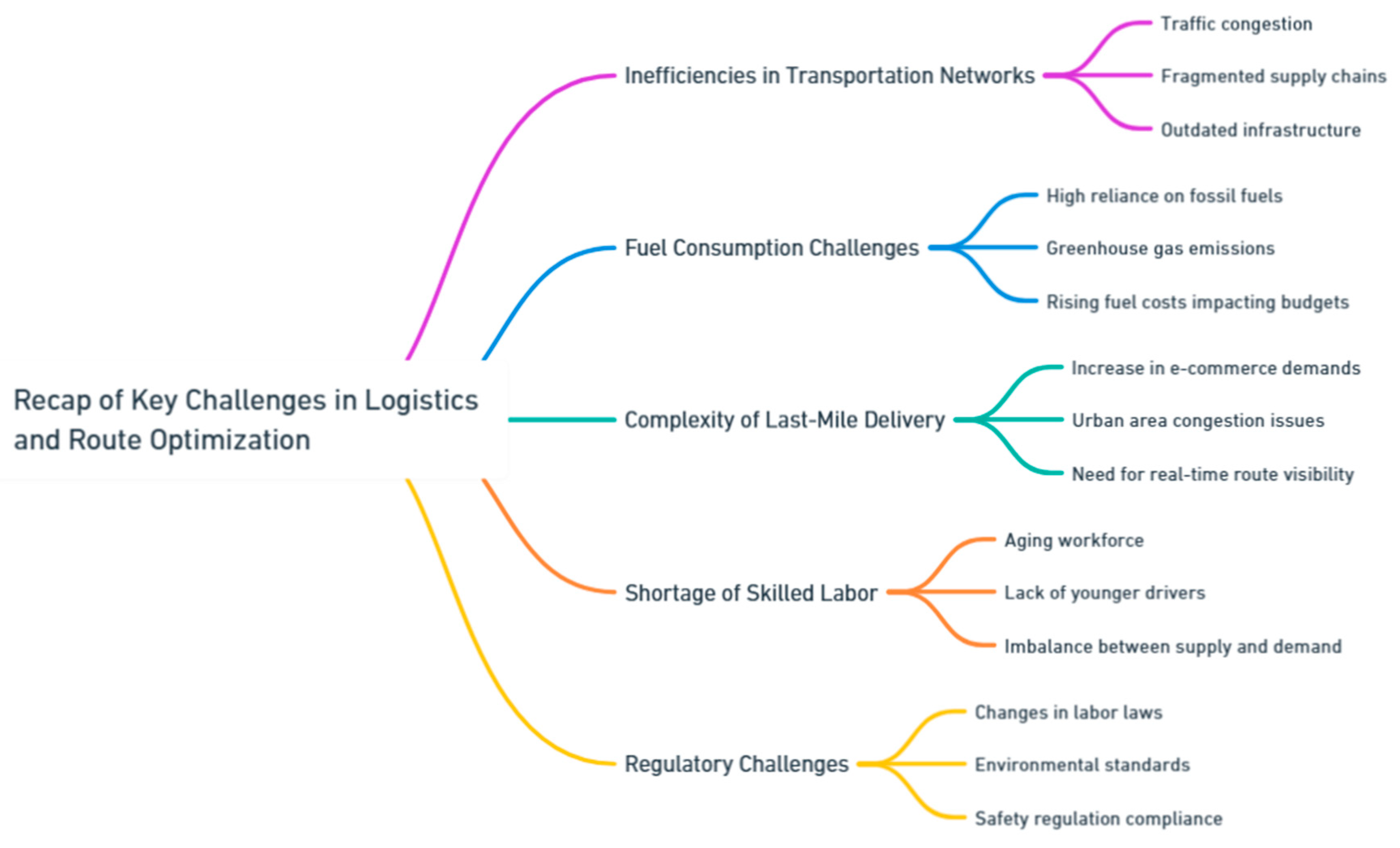

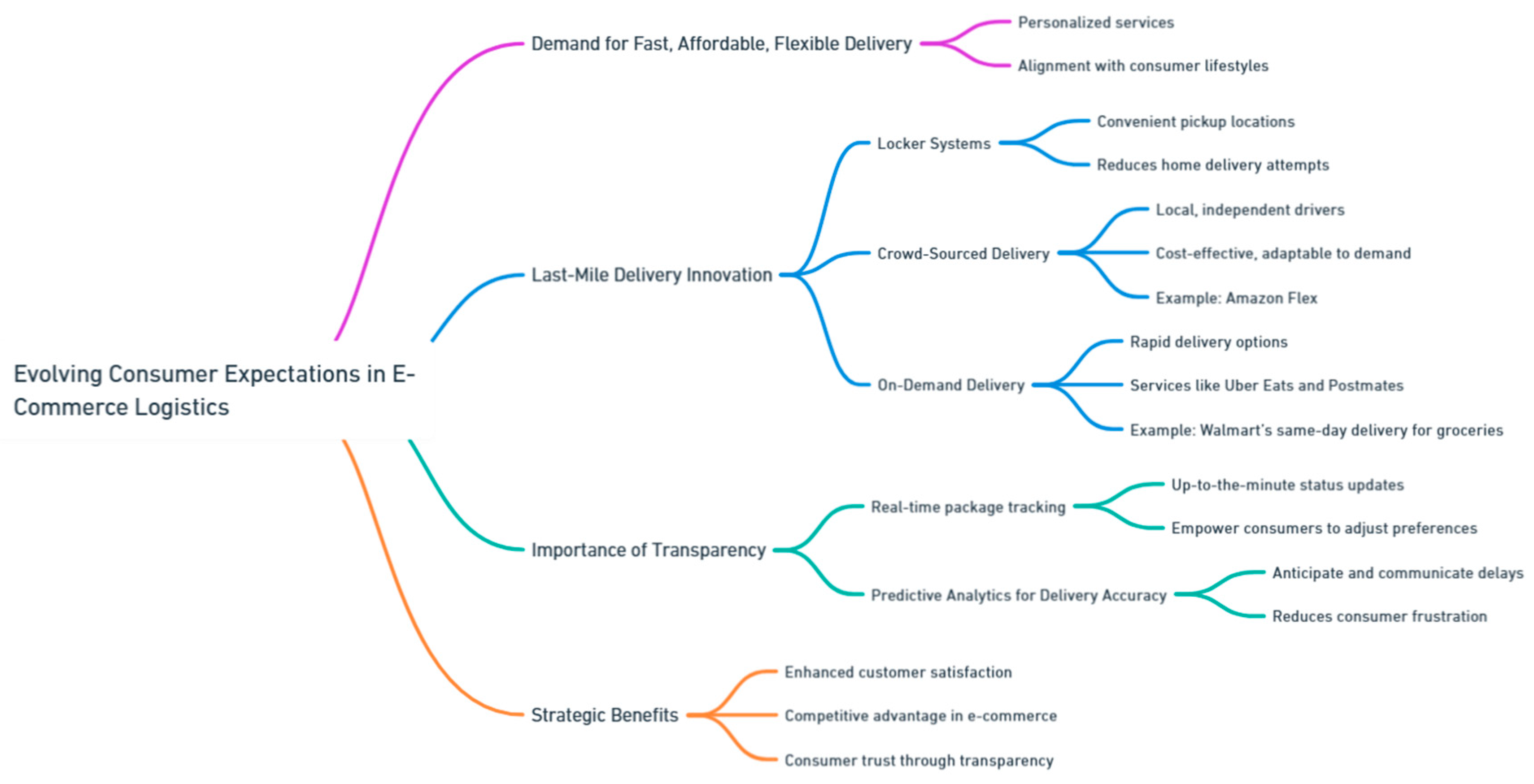

- Congestion and Inefficient Routing: Last-mile delivery vehicles often face traffic congestion, especially in densely populated cities. This not only slows down deliveries but also leads to higher fuel consumption and increased emissions. Inefficient routing can further exacerbate the problem, as vehicles may cover more distance than necessary. Optimizing delivery routes and using technology to plan more efficient paths can significantly reduce the carbon footprint of last-mile delivery.

- Electric and Alternative Fuel Vehicles: To address the environmental challenges of last-mile delivery, many companies are turning to electric vehicles (EVs) and alternative fuel vehicles. EVs, in particular, are gaining popularity for urban deliveries as they produce zero emissions at the point of use. However, the overall carbon footprint depends on how the electricity is generated. In regions where renewable energy is used, EVs can dramatically reduce emissions, making them a key part of the solution for sustainable last-mile logistics.

- Energy Use for Lighting and Climate Control: Warehouses require extensive lighting to ensure the safe and efficient handling of goods. Many older warehouses still rely on inefficient lighting systems, which consume large amounts of electricity. Climate control, such as heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC), is another major energy consumer. Warehouses dealing with perishable goods often require refrigeration, further increasing their carbon footprint. Transitioning to energy-efficient lighting systems, such as LED, and using renewable energy sources can help reduce emissions from warehousing operations.

- Material Handling Equipment: Forklifts, cranes, and conveyor systems used to move goods within warehouses are typically powered by electricity or fossil fuels. While some facilities have shifted to electric forklifts, others still use diesel-powered equipment, contributing to carbon emissions. Automation and robotics in warehousing have the potential to improve efficiency, but they also require energy, which can increase the carbon footprint if not managed sustainably.

- Congestion and Inefficient Routing: Last-mile delivery vehicles often face traffic congestion, especially in densely populated cities. This not only slows down deliveries but also leads to higher fuel consumption and increased emissions. Inefficient routing can further exacerbate the problem, as vehicles may cover more distance than necessary. Optimizing delivery routes and using technology to plan more efficient paths can significantly reduce the carbon footprint of last-mile delivery.

- Electric and Alternative Fuel Vehicles: To address the environmental challenges of last-mile delivery, many companies are turning to electric vehicles (EVs) and alternative fuel vehicles. EVs, in particular, are gaining popularity for urban deliveries as they produce zero emissions at the point of use. However, the overall carbon footprint depends on how the electricity is generated. In regions where renewable energy is used, EVs can dramatically reduce emissions, making them a key part of the solution for sustainable last-mile logistics.

4.3. Reducing Carbon Footprint Through Smart Technologies

4.3.1. Definition and Types of Smart Technologies in Logistics

4.3.2. Types of Smart Technologies in Logistics

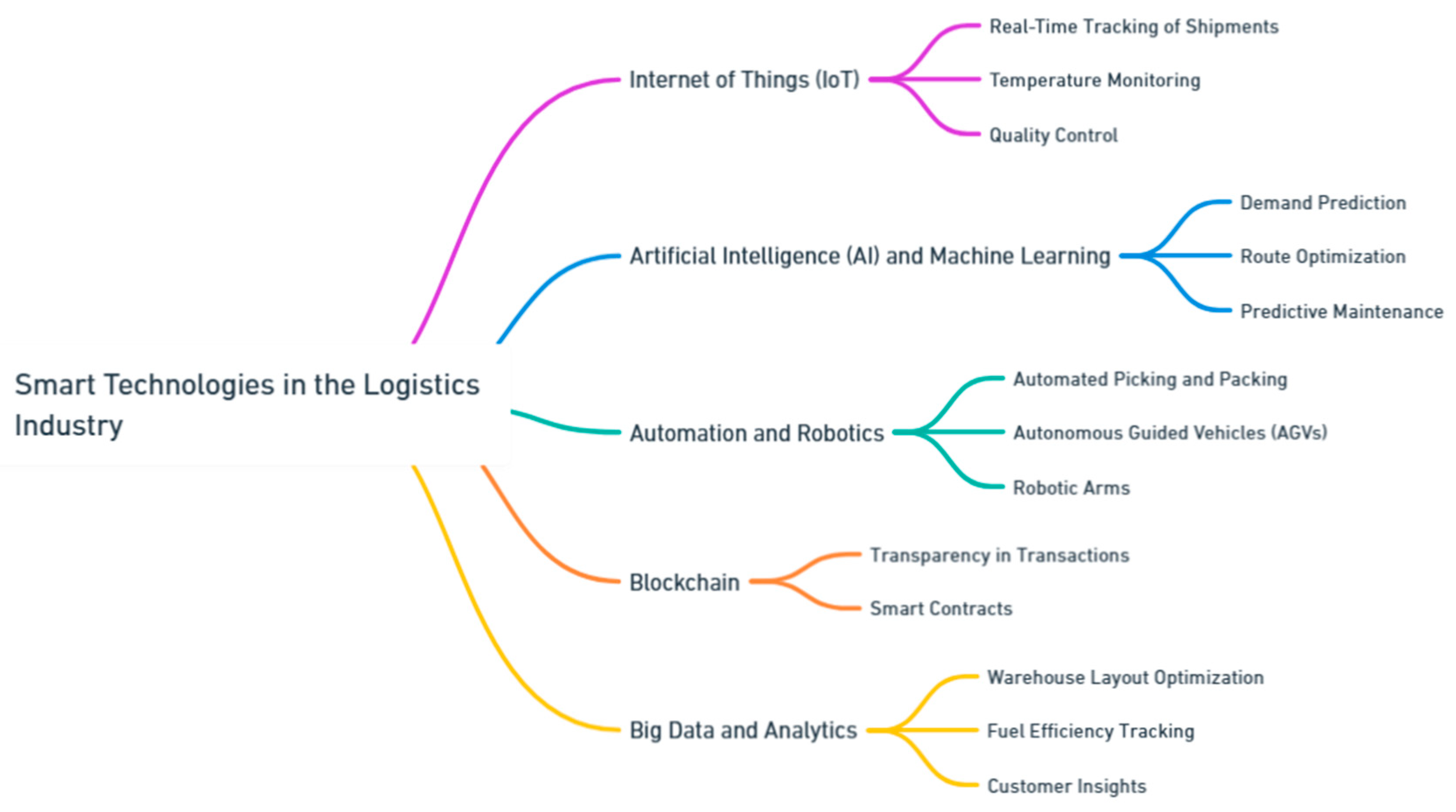

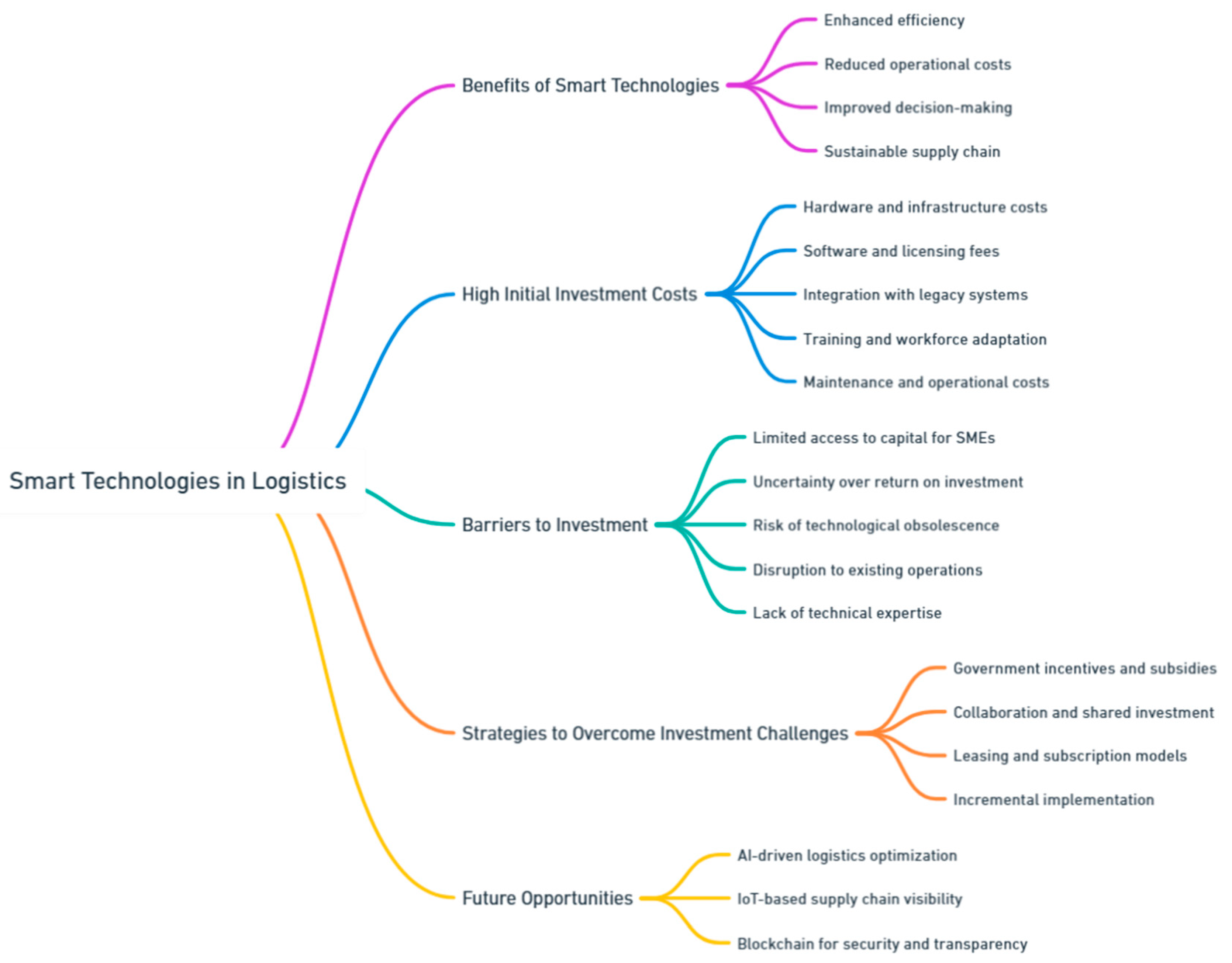

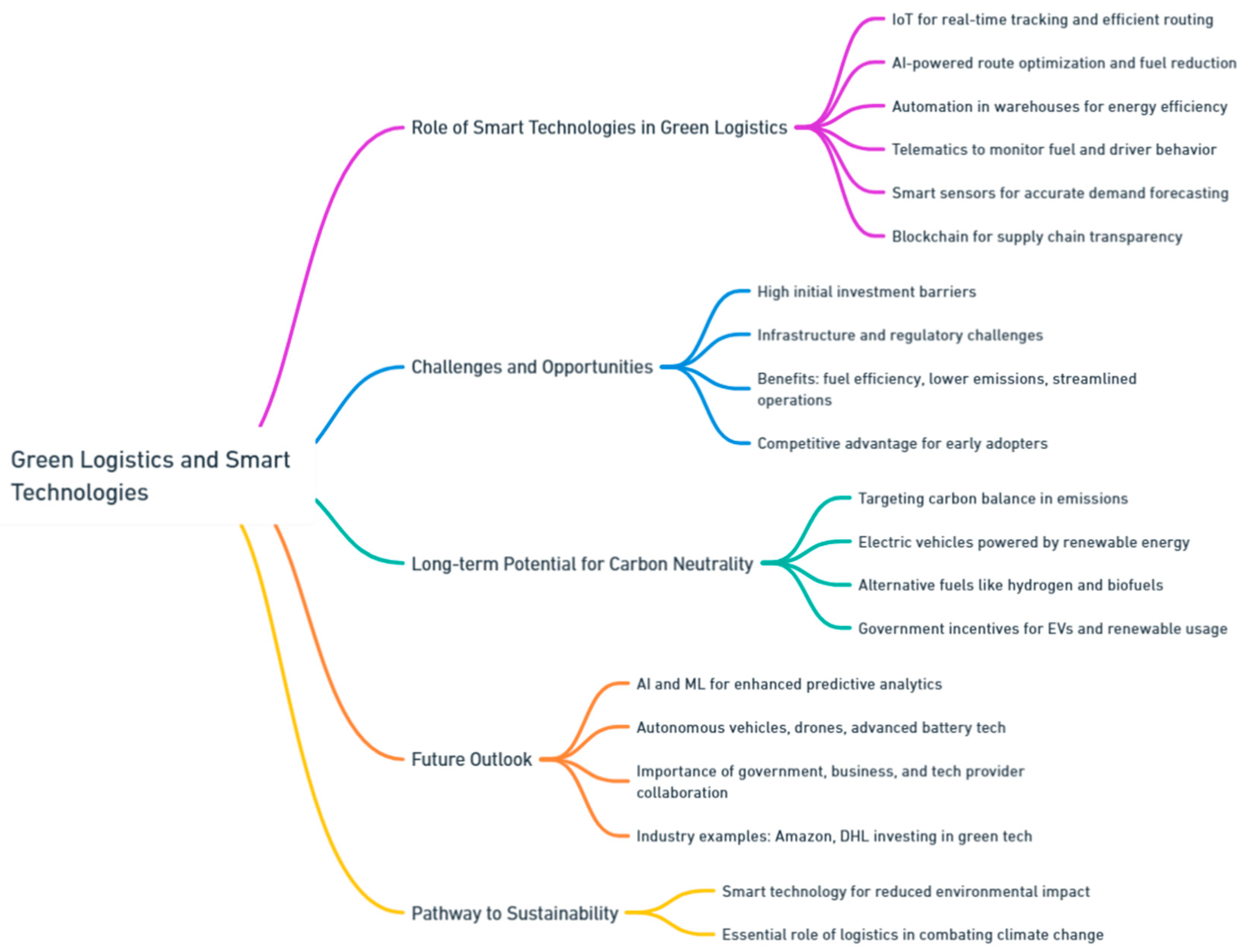

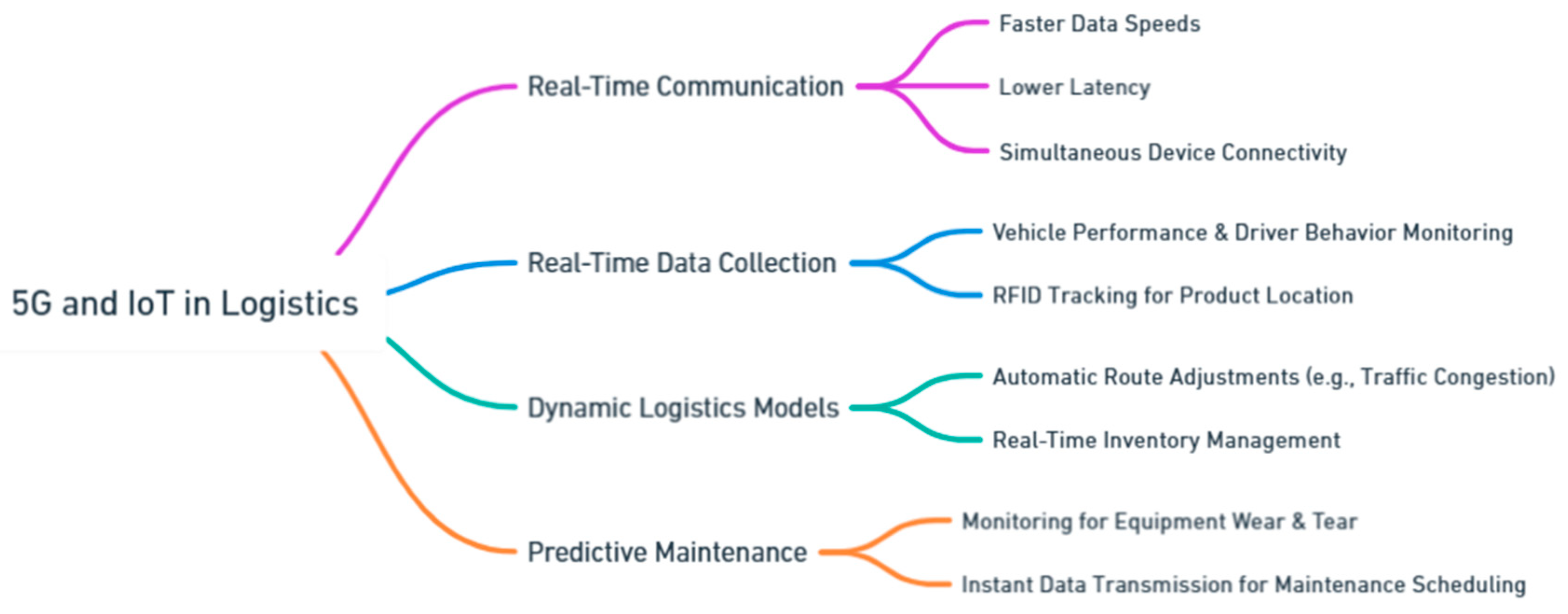

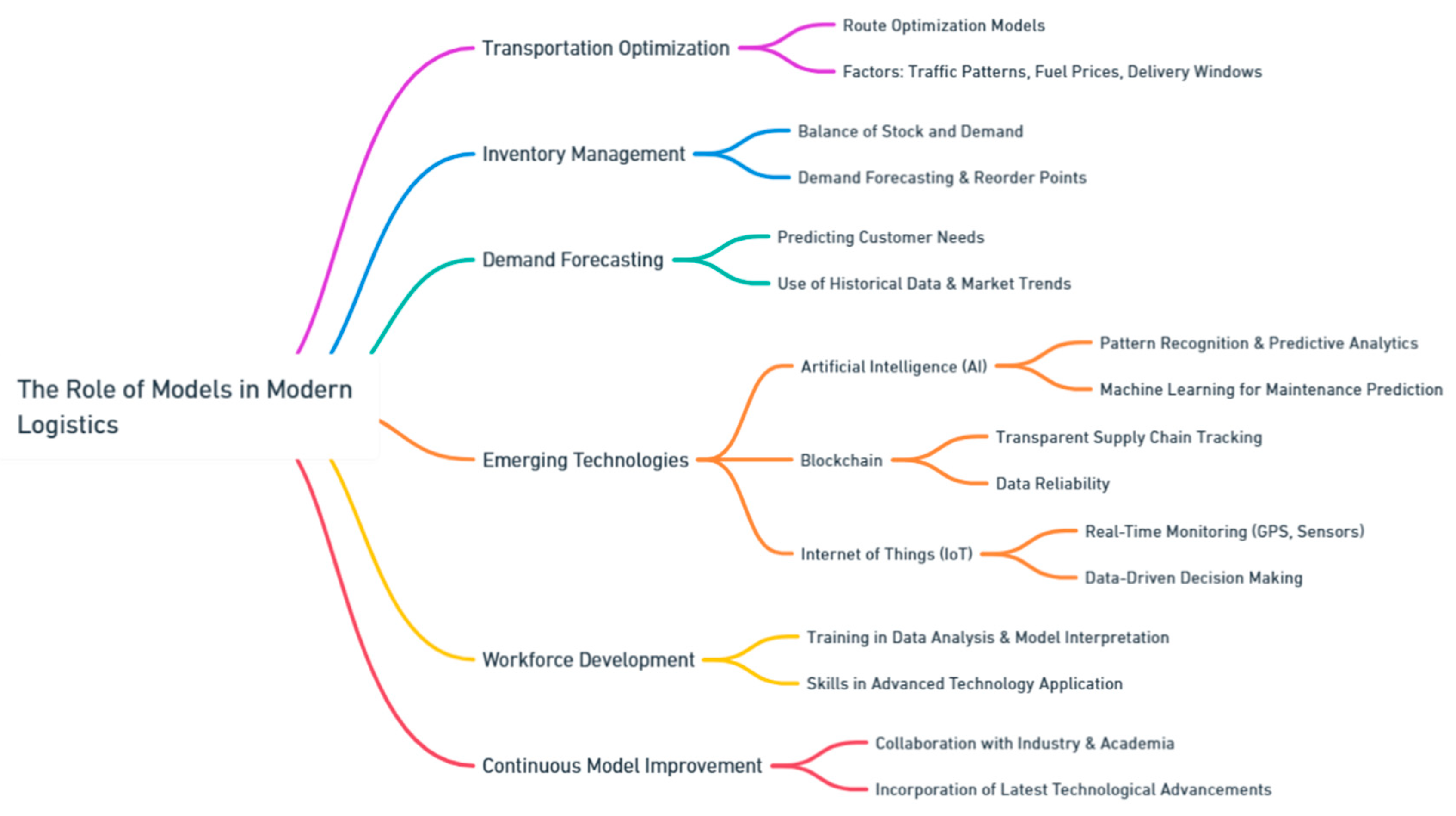

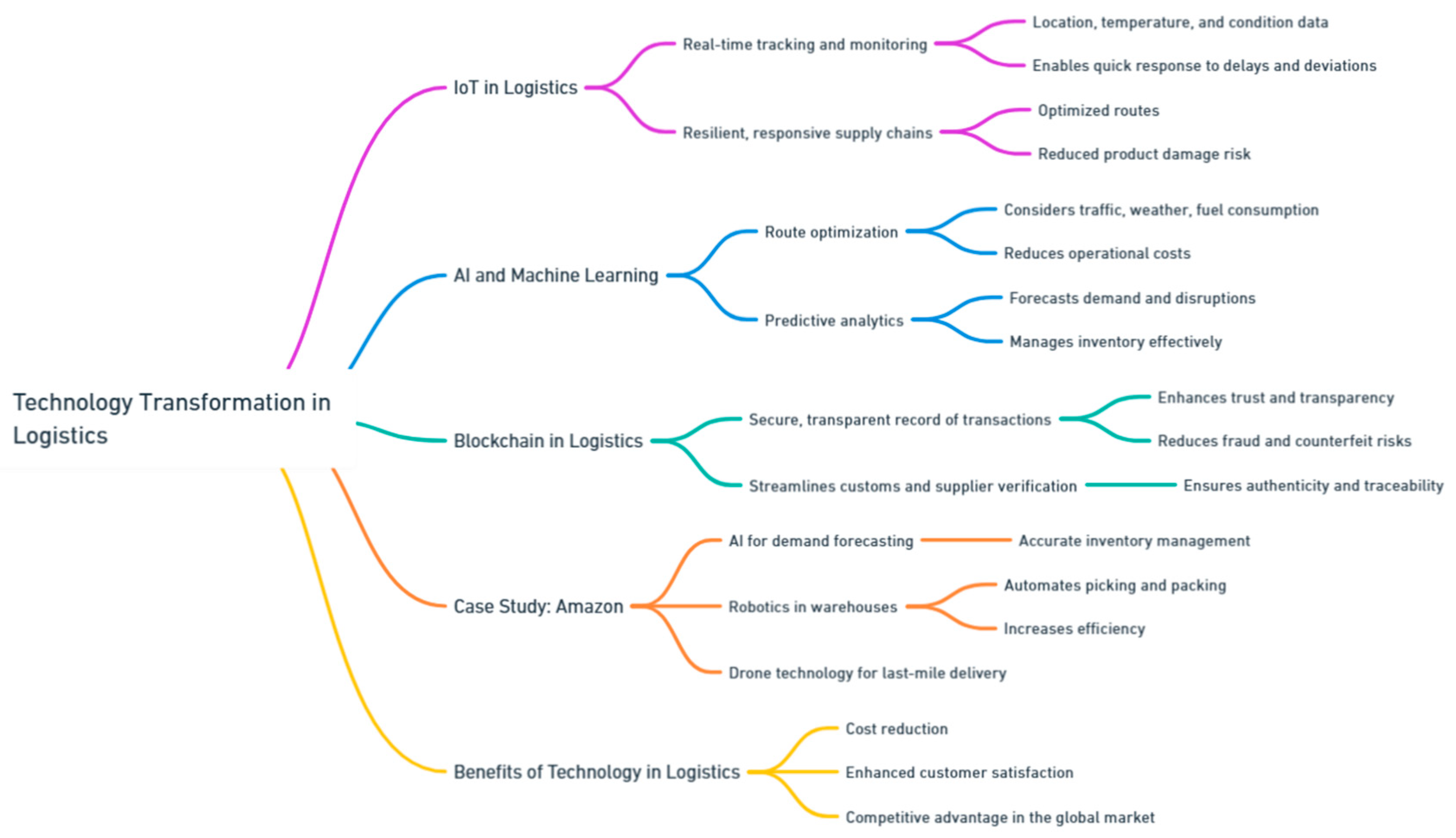

- Internet of Things (IoT). The Internet of Things (IoT) is a network of interconnected devices that collect and exchange data via the internet. In logistics, IoT devices can be embedded in vehicles, containers, warehouses, and cargo to monitor real-time conditions, including location, temperature, humidity, and movement. This constant flow of data helps companies track shipments, monitor inventory, and maintain product quality, especially for sensitive goods like food or pharmaceuticals. For example, IoT sensors can alert logistics managers if the temperature inside a refrigerated truck exceeds a certain threshold, allowing them to take immediate action and prevent spoilage. Additionally, IoT-based vehicle tracking systems provide real-time updates on delivery routes, enabling better route planning and reducing delays. This enhanced visibility and control lead to improved operational efficiency, cost savings, and customer satisfaction.

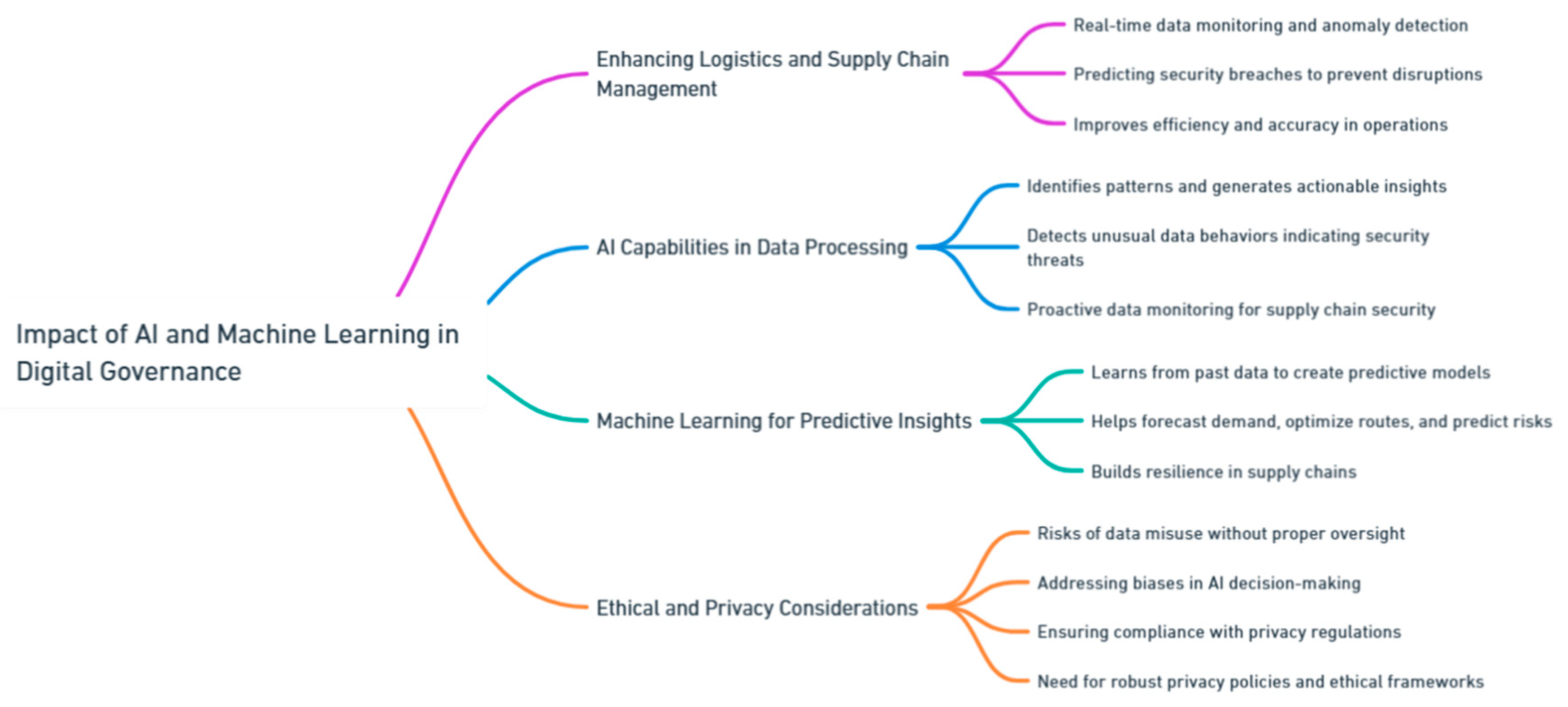

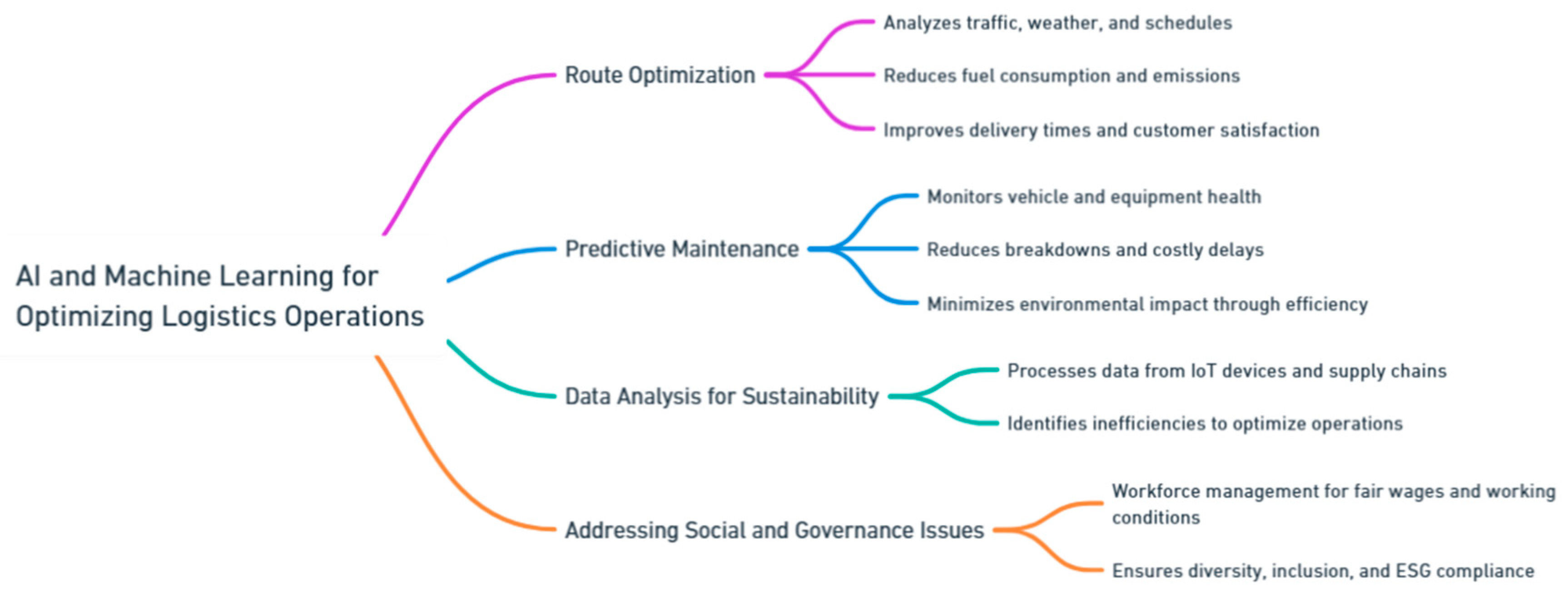

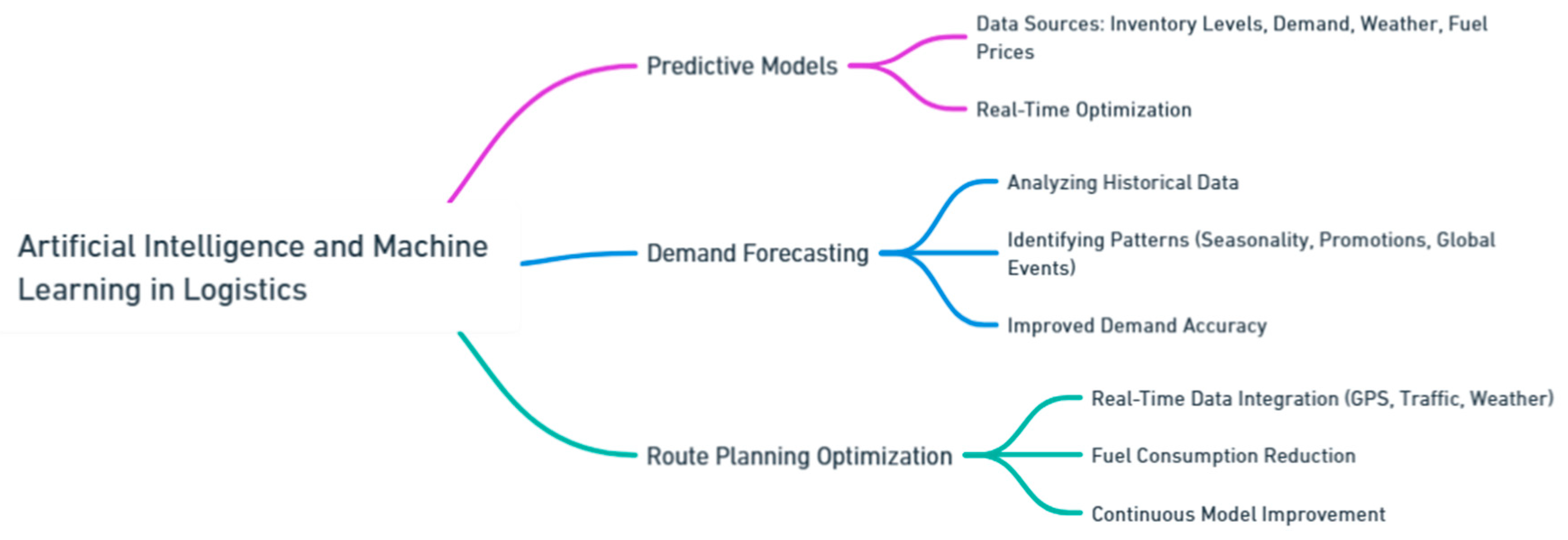

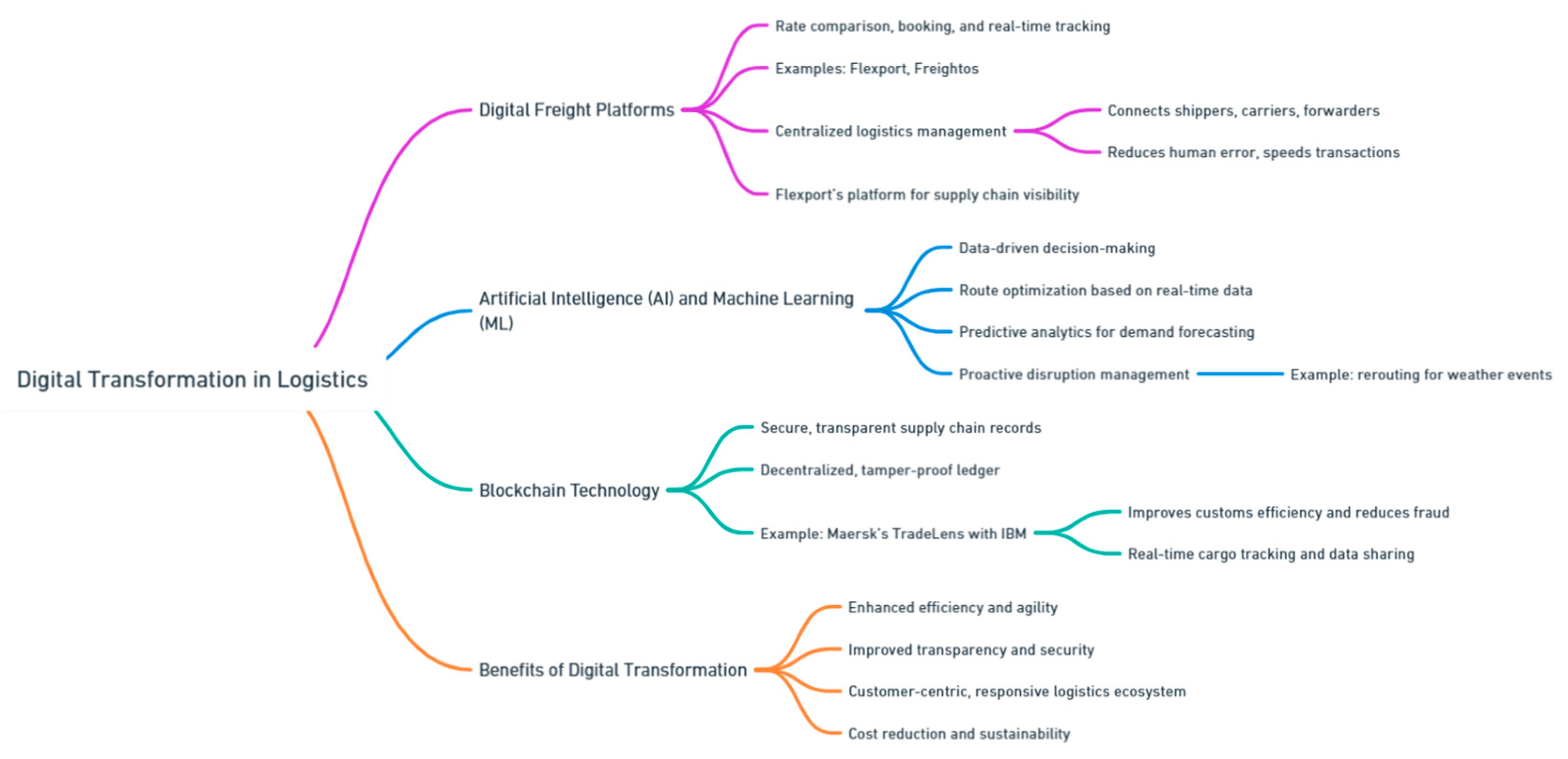

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are transforming logistics by enabling smarter decision-making and process automation. AI algorithms can analyze vast amounts of data to identify patterns, predict demand, and optimize logistics networks. Machine learning, a subset of AI, allows systems to improve their performance over time by learning from historical data. In logistics, AI and ML are commonly used for demand forecasting, route optimization, and predictive maintenance. For instance, AI-powered systems can analyze past demand patterns and market trends to forecast future demand accurately. This helps logistics companies optimize inventory levels, reduce stockouts, and avoid overstocking. Additionally, AI-driven route optimization tools analyze real-time traffic, weather conditions, and fuel prices to determine the most efficient delivery routes, reducing transportation costs and carbon emissions. AI is also being used in predictive maintenance, where sensors on vehicles and machinery collect data on performance and condition. AI algorithms analyze this data to predict when equipment is likely to fail, allowing companies to schedule maintenance before breakdowns occur. This proactive approach reduces downtime, extends equipment lifespan, and minimizes repair costs.

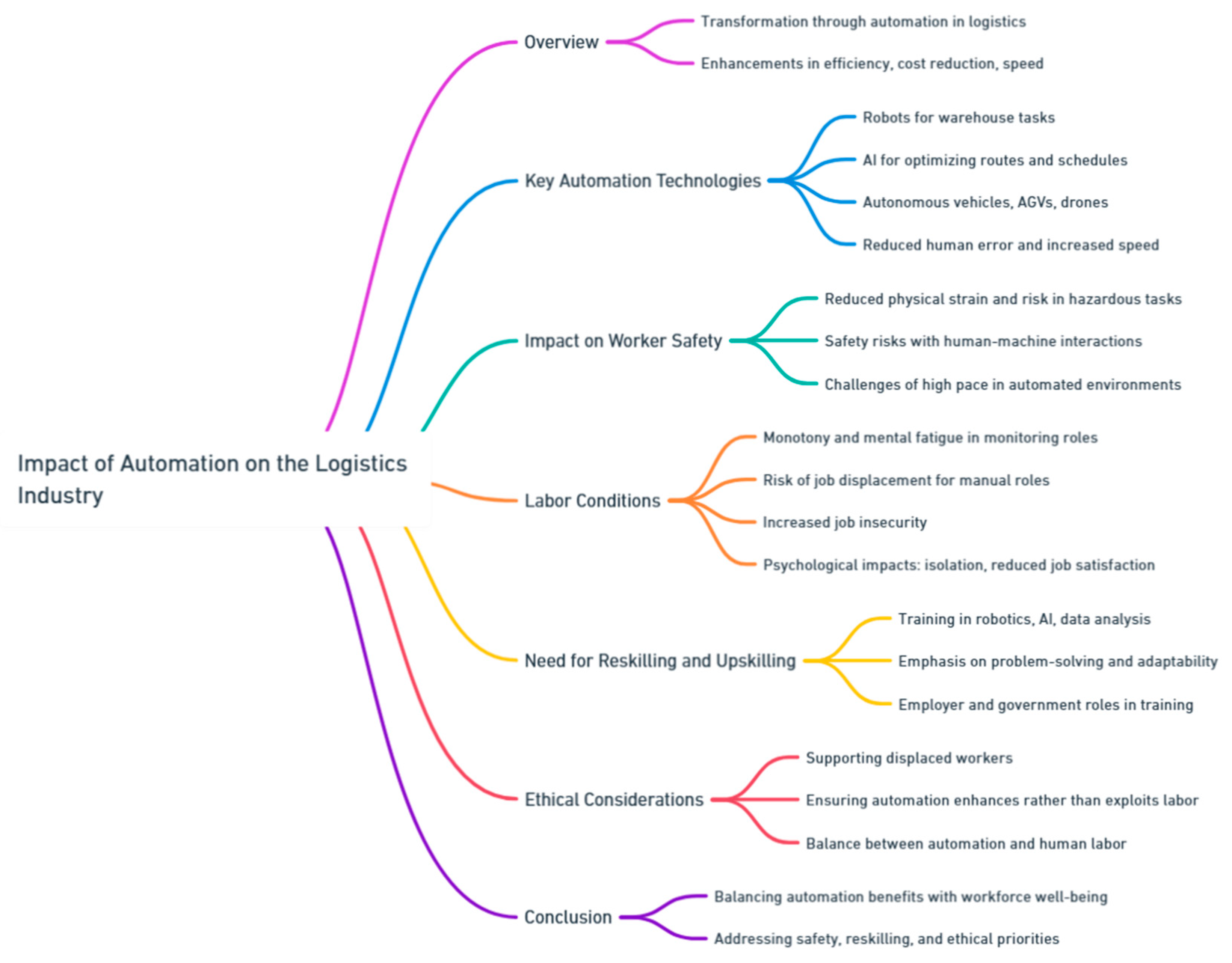

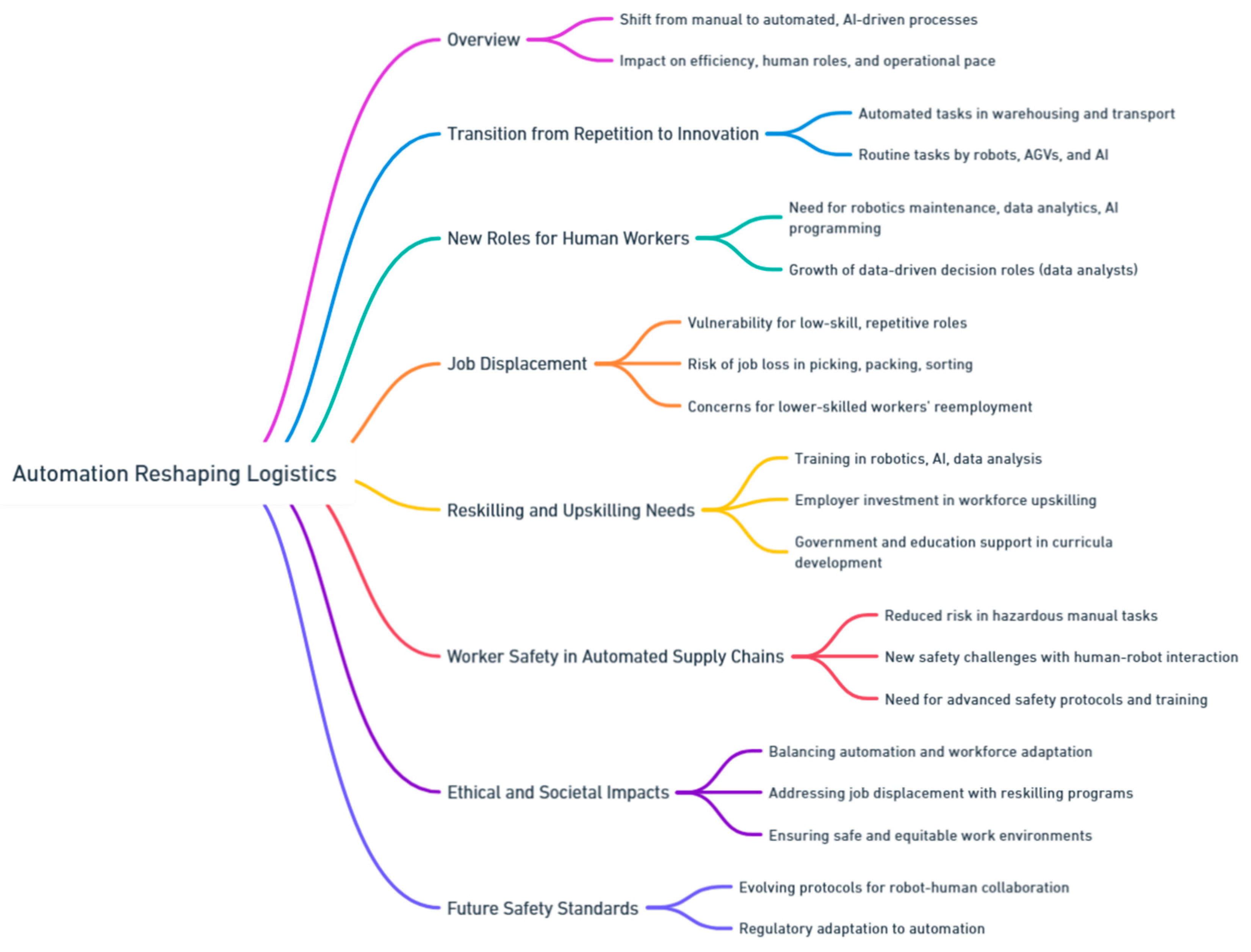

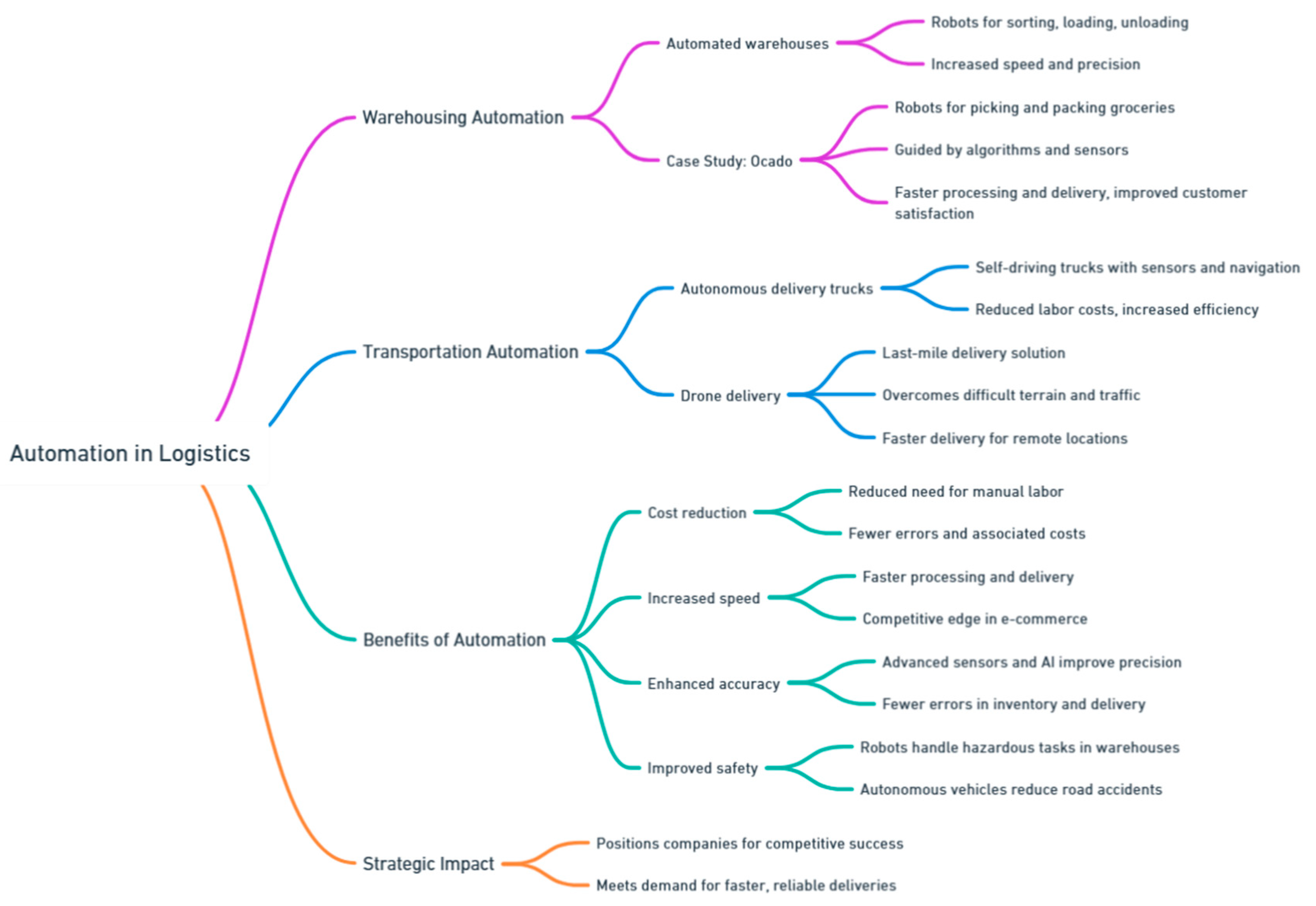

- Robotics and Automation. Robotics and automation are revolutionizing logistics by enhancing efficiency and reducing manual labor. In warehouses, automated systems and robots are used to perform tasks such as picking, packing, sorting, and inventory management. These technologies not only improve speed and accuracy but also reduce the risk of human error and workplace injuries. One common application of automation in logistics is the use of Automated Guided Vehicles (AGVs) or Autonomous Mobile Robots (AMRs) in warehouses. AGVs and AMRs are used to transport goods within a warehouse or distribution center, reducing the need for manual handling. These robots can navigate complex environments, avoid obstacles, and optimize their routes, leading to faster and more efficient operations. Robotic arms are also being employed for picking and packing tasks. These machines are equipped with sensors and AI algorithms that allow them to handle items of varying shapes, sizes, and weights. By automating these tasks, companies can increase throughput and reduce labor costs, particularly during peak seasons when demand surges.

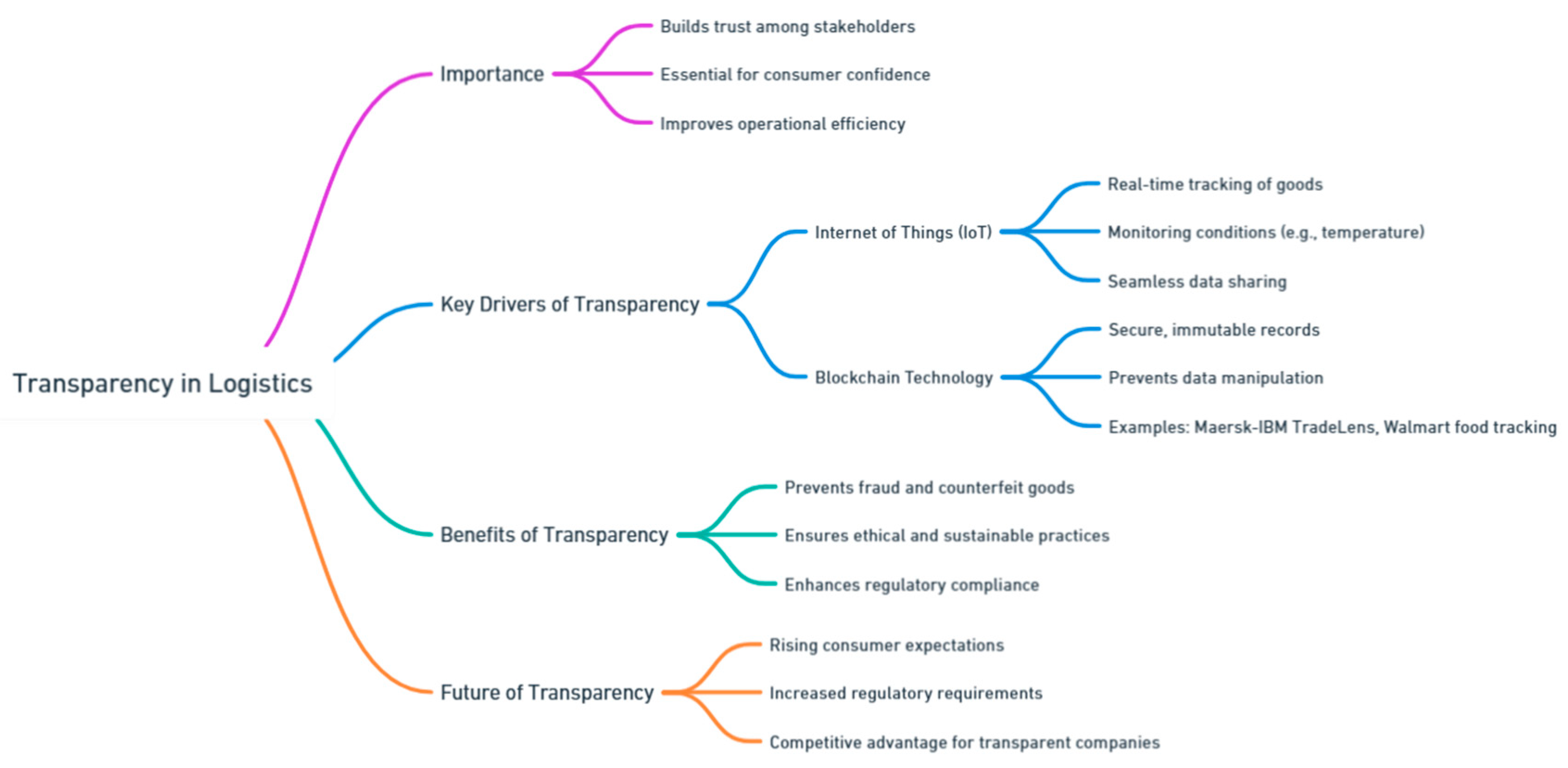

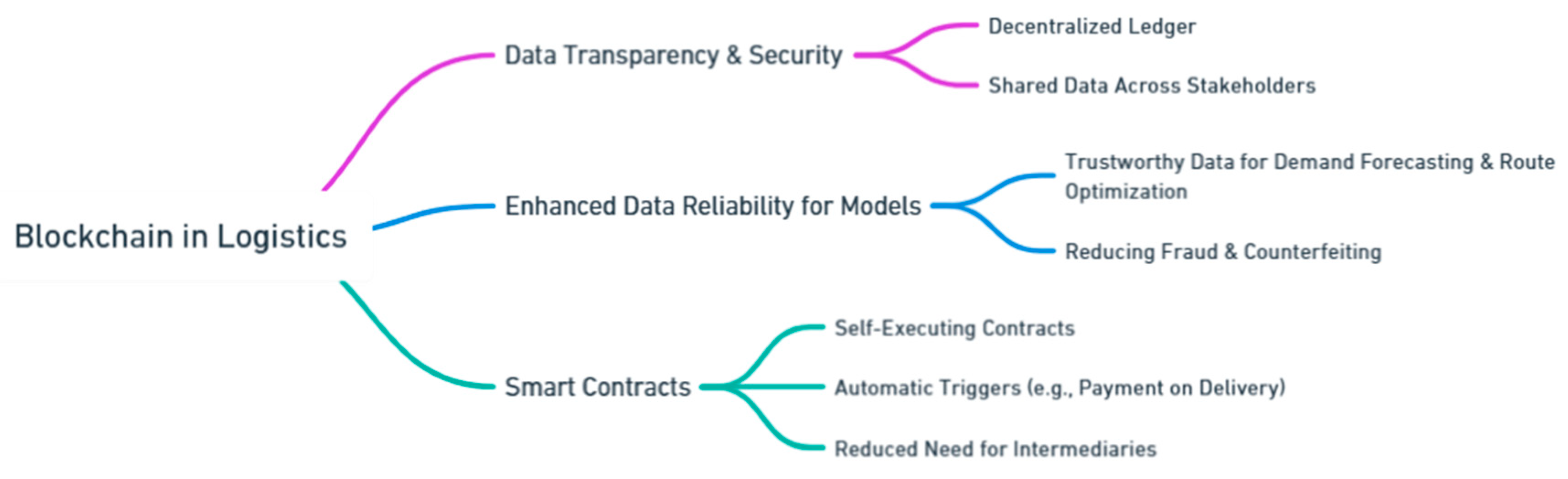

- Blockchain Technology. Blockchain technology is gaining traction in logistics due to its ability to enhance transparency, security, and traceability in supply chain transactions. Blockchain is a decentralized and immutable ledger that records transactions in a secure and transparent manner. In logistics, it can be used to track the movement of goods, verify authenticity, and ensure compliance with regulations. For instance, blockchain can provide a tamper-proof record of a product's journey from the manufacturer to the end customer, including all intermediaries such as transport providers, warehouses, and customs authorities. This transparency reduces the risk of fraud, counterfeiting, and disputes. Moreover, blockchain-based smart contracts can automate payment and verification processes, speeding up transactions and reducing administrative costs. Blockchain is particularly valuable in industries that require strict regulatory compliance, such as pharmaceuticals and food supply chains. It ensures that all parties involved in the logistics process have access to accurate and up-to-date information, improving accountability and trust.

- Big Data and Data Analytics. The logistics industry generates vast amounts of data, from shipping schedules and inventory levels to customer preferences and fuel consumption. Big data and data analytics technologies allow companies to process and analyze this data to gain insights, make informed decisions, and improve operational performance. For example, data analytics can be used to optimize warehouse layouts by analyzing order patterns and item locations. By placing frequently ordered items closer to packing stations, companies can reduce the time it takes to fulfill orders. Similarly, big data analytics can be used to analyze fuel consumption patterns and identify areas where efficiency can be improved, such as by optimizing driving behaviors or selecting more fuel-efficient routes. In addition, customer data can be analyzed to identify trends and preferences, enabling companies to offer more personalized services and improve customer satisfaction. The ability to leverage big data for predictive analytics also helps companies anticipate demand, manage inventory levels, and respond more effectively to market fluctuations.

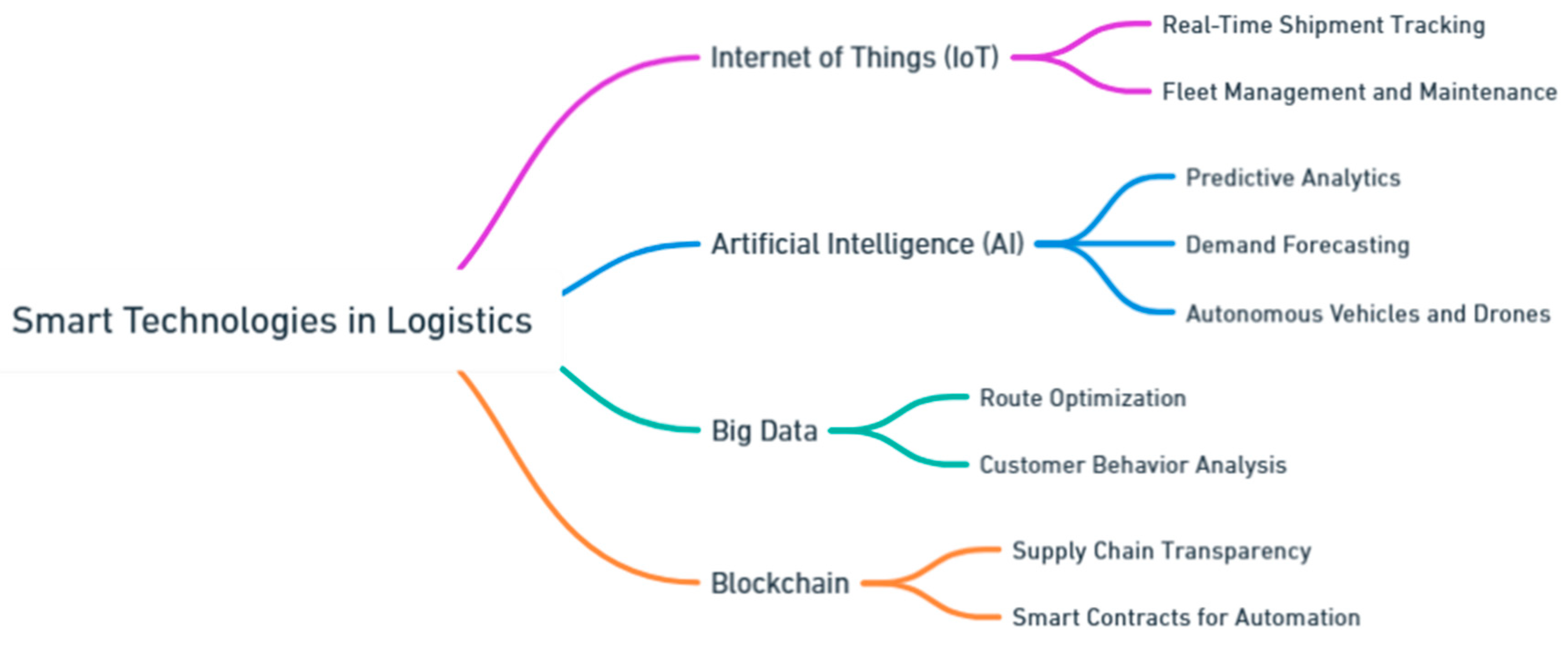

4.3.3. Smart Technologies in Logistics

- Real-Time Shipment Tracking: IoT sensors embedded in containers or vehicles allow companies to track shipments in real time. This technology provides updates on the location, condition, and estimated arrival time of goods. For example, a sensor in a refrigerated truck can monitor temperature and alert the driver or logistics manager if the temperature deviates from the required range, ensuring that perishable goods like food or pharmaceuticals remain in optimal condition.

- Fleet Management: IoT-enabled GPS tracking systems are used to monitor vehicle routes, fuel consumption, and maintenance needs. By gathering data from fleet vehicles, companies can optimize routes to reduce fuel consumption, ensure timely maintenance, and minimize vehicle downtime.

- Predictive Analytics and Demand Forecasting: AI algorithms can analyze historical data, customer behavior, and market trends to accurately forecast demand. This helps companies manage inventory levels more effectively, reducing the risk of overstocking or stockouts. By predicting when and where demand will spike, logistics providers can better allocate resources and streamline operations.

- Autonomous Vehicles and Drones: AI is a key enabler of autonomous delivery systems, including self-driving trucks and drones. These technologies are being developed to automate last-mile deliveries, reduce labor costs, and improve delivery times. While still in the early stages, autonomous delivery systems have the potential to significantly disrupt the logistics industry by enhancing operational efficiency and reducing reliance on human labor.

- Route Optimization: Big Data analytics tools can process vast amounts of data from multiple sources—such as traffic patterns, fuel prices, weather conditions, and delivery schedules—to identify the most efficient delivery routes. This helps reduce fuel consumption, shorten delivery times, and lower operational costs.

- Customer Behavior Analysis: Big Data allows logistics companies to analyze customer purchasing patterns, preferences, and delivery expectations. By understanding customer behavior, companies can offer personalized services, optimize delivery schedules, and improve overall customer satisfaction. For instance, data on e-commerce purchasing trends can help companies prepare for peak periods, such as holiday shopping seasons, by optimizing inventory and staffing levels.

- Supply Chain Transparency: Blockchain can provide a digital ledger that tracks the movement of goods from the point of origin to the final destination. This is particularly useful in industries where product authenticity and regulatory compliance are critical, such as pharmaceuticals and food. For example, Blockchain technology can verify that a product was sourced ethically, manufactured according to regulatory standards, and delivered without tampering.

- Smart Contracts: Blockchain enables the use of smart contracts, which are self-executing contracts with predefined conditions. In logistics, smart contracts can automate processes such as payments, document verification, and customs clearance. For instance, once a shipment arrives at its destination and is confirmed by IoT sensors, a smart contract could automatically trigger payment to the supplier, reducing administrative delays and costs.

4.4. Reducing Carbon Footprint Through Smart Technologies

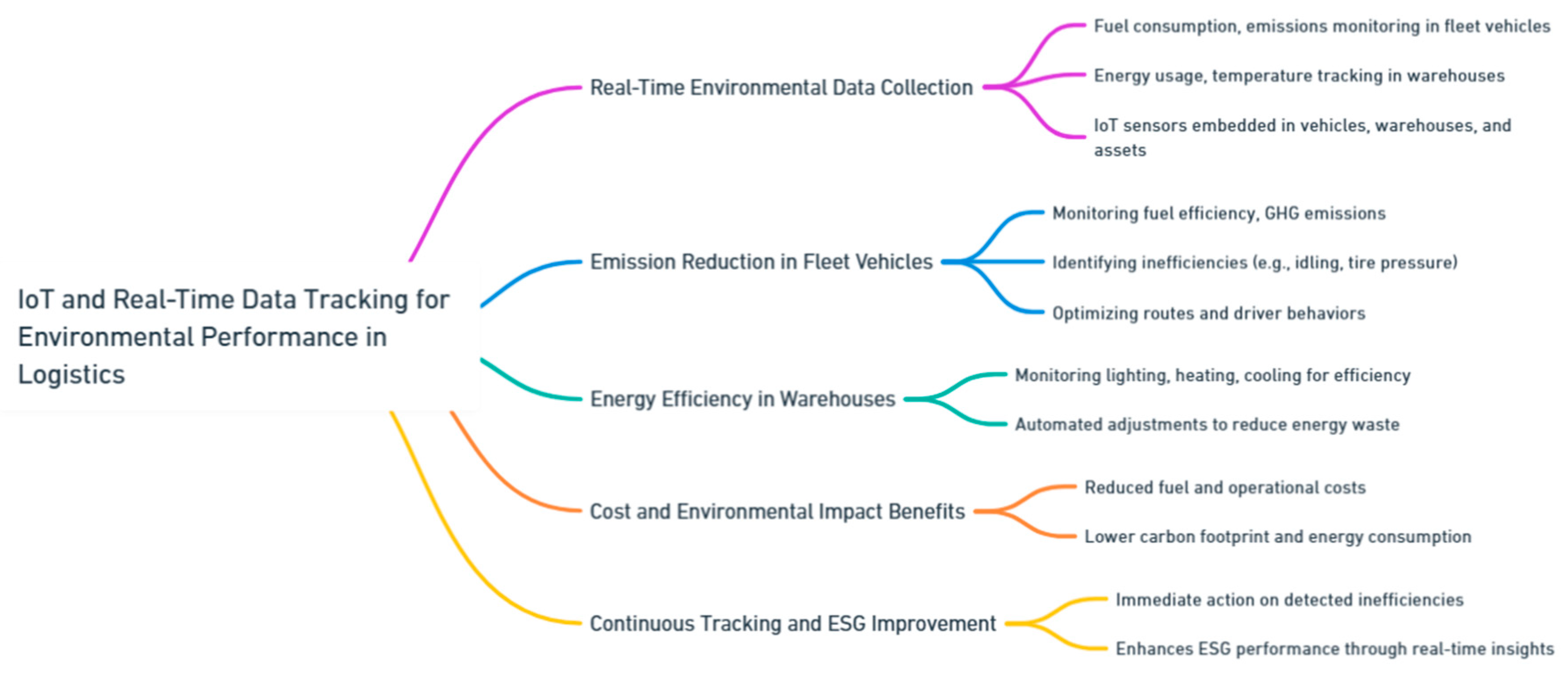

4.4.1. IoT and Its Impact on Carbon Emissions in Logistics

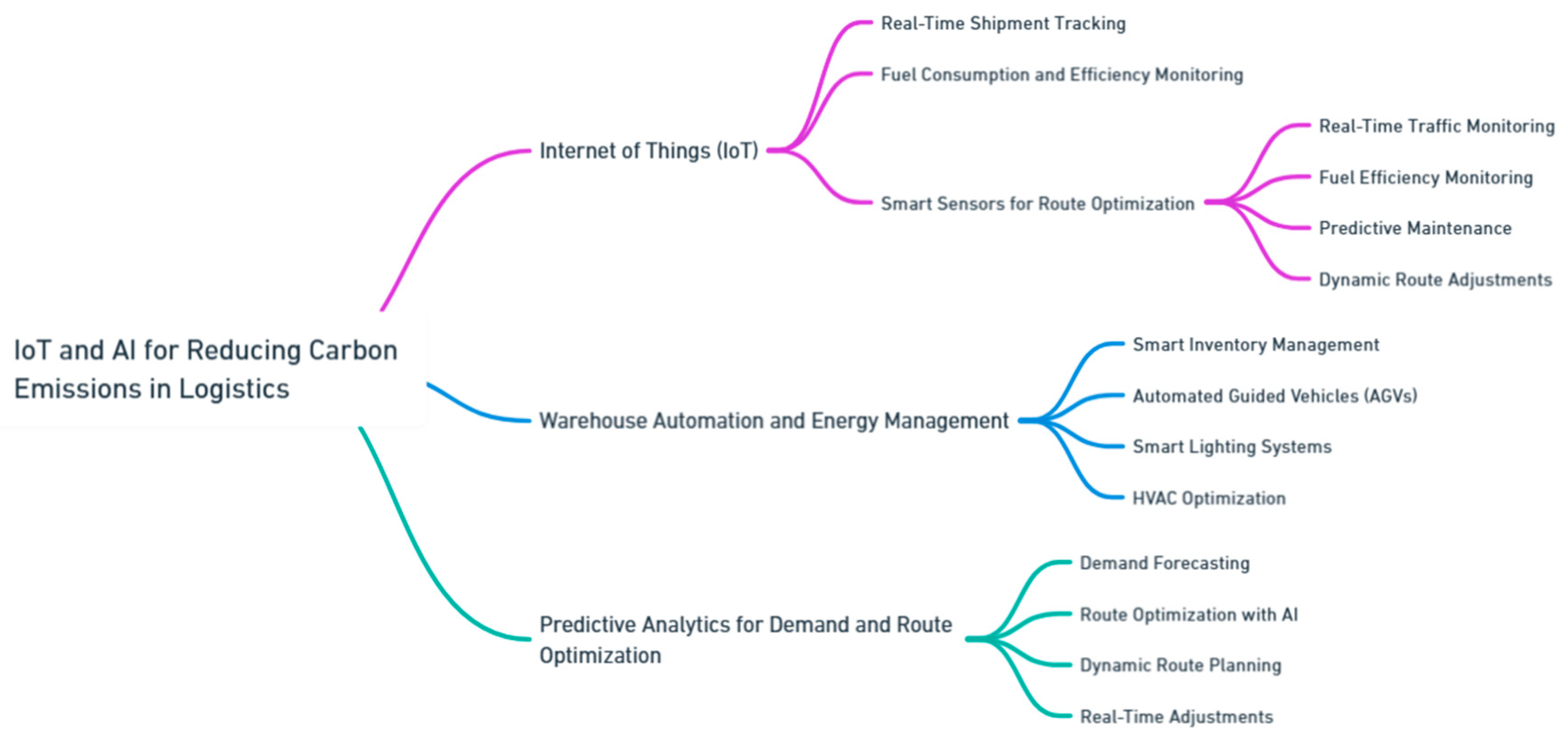

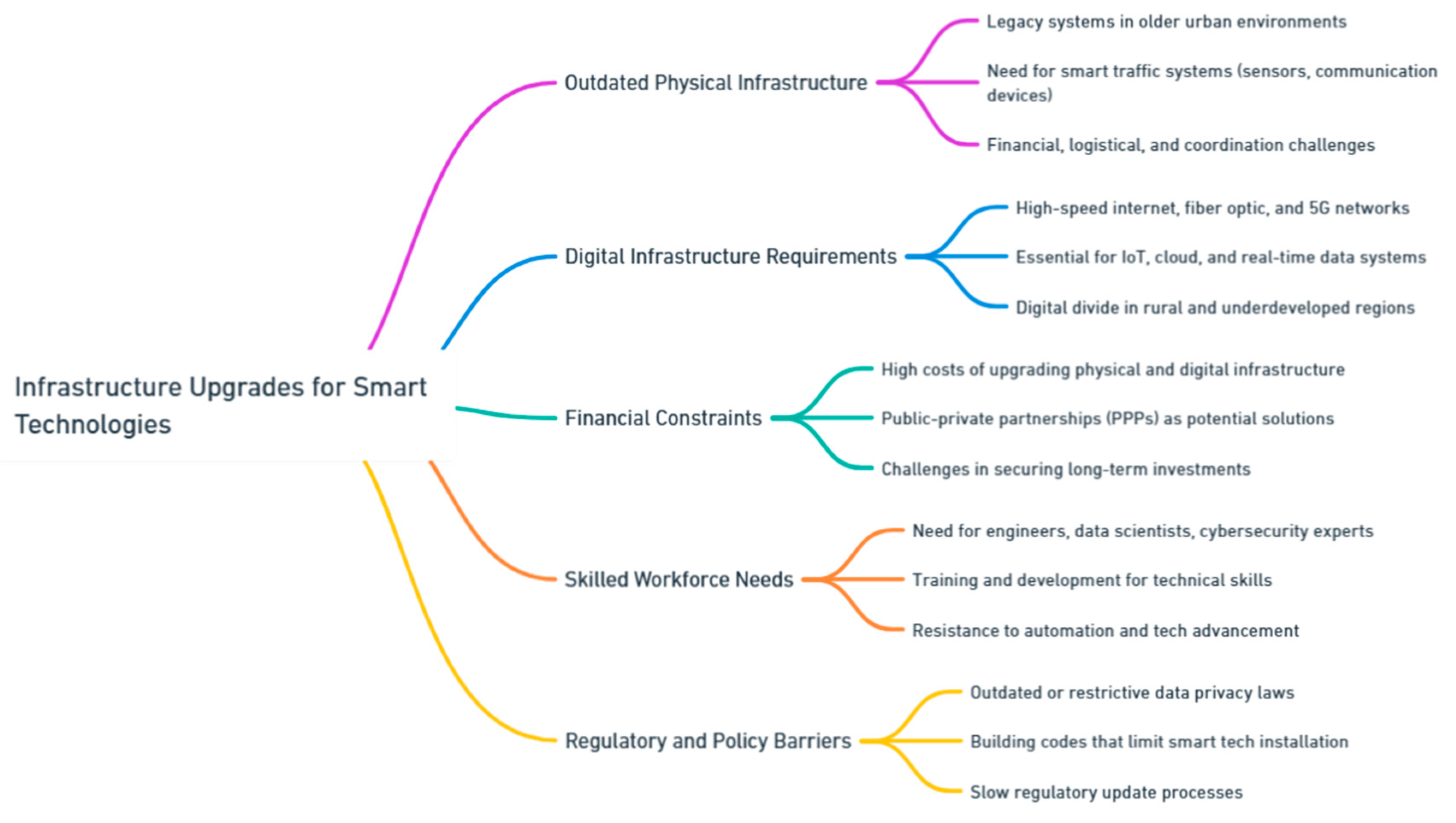

- Real-Time Traffic Monitoring: One of the key challenges in logistics is dealing with unpredictable traffic conditions. Traffic congestion leads to longer travel times, increased fuel consumption, and higher emissions. Smart sensors installed in vehicles can collect real-time data on traffic patterns, road conditions, and vehicle locations. This data is transmitted to route optimization systems, which use advanced algorithms to adjust routes on the fly, avoiding traffic bottlenecks and selecting the fastest and most fuel-efficient paths (Chen et al., 2021; Danchuk et al., 2023).

- Fuel Efficiency Monitoring: Smart sensors in vehicles also monitor fuel consumption, providing data on driving behavior, engine performance, and vehicle load. By analyzing this data, logistics managers can identify inefficiencies in how vehicles are being operated. For example, sudden acceleration, excessive idling, and hard braking increase fuel consumption and emissions. Route optimization systems can recommend driving adjustments to minimize fuel use and suggest optimal routes that reduce the number of stops and starts, further improving fuel efficiency (Wickramanayake et al., 2020; Peppes et al., 2021).

- Predictive Maintenance: IoT-enabled sensors also help optimize vehicle performance by monitoring the condition of critical components such as tires, brakes, and engines. Predictive maintenance systems use data from these sensors to predict when a vehicle might experience a breakdown or require maintenance. By addressing maintenance issues before they lead to breakdowns, companies can avoid unexpected delays and reduce the likelihood of vehicles taking longer or less efficient routes due to malfunctions. Properly maintained vehicles also run more efficiently, reducing fuel consumption and emissions (Massaro et al.,2020; Killeen, et al., 2022).

- Dynamic Route Adjustments: Traditional route planning methods rely on static data, such as historical traffic patterns and distances. However, this approach doesn't account for real-time variables like accidents, weather conditions, or sudden road closures, all of which can lead to inefficient routes. Smart sensors, combined with real-time data analytics, enable dynamic route adjustments based on current conditions. For instance, if a vehicle encounters an unexpected road closure, the system can instantly reroute it to a faster, more fuel-efficient path, saving both time and fuel (Guo et al., 2020; Gmira et al., 2021).

- Integration with Other Sustainable Technologies: IoT-based route optimization can be integrated with other green technologies to further reduce emissions. For example, smart sensors can coordinate with electric vehicles (EVs) to ensure that routes are optimized based on charging station locations and battery life. This allows logistics companies to maximize the use of EVs, which produce zero tailpipe emissions, for urban deliveries and short-distance routes (Li et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2022).

- Real-time Monitoring of Fuel Consumption: One of the primary contributors to carbon emissions in logistics is fuel consumption. IoT sensors track fuel usage in real time, giving fleet managers insight into how much fuel is being consumed by each vehicle during different driving conditions. By analyzing this data, managers can identify inefficient fuel usage patterns and adjust routes or driving behaviors accordingly. For example, if a particular vehicle consistently uses more fuel than others under similar conditions, it could indicate engine inefficiency or poor driving habits, both of which contribute to unnecessary fuel consumption and higher emissions.

- Monitoring Driver Behavior for Efficiency: Driving behaviors such as harsh braking, rapid acceleration, and excessive idling can significantly impact fuel efficiency. IoT-enabled telematics systems provide real-time feedback to drivers and fleet managers about driving habits that waste fuel. Through constant monitoring, drivers can be alerted to adjust their behavior to minimize fuel consumption. For instance, smooth acceleration, maintaining steady speeds, and avoiding prolonged idling can reduce the amount of fuel burned, resulting in lower emissions. By promoting more eco-friendly driving practices, IoT helps logistics companies make substantial progress in reducing their carbon footprint (Mane et al., 2021; Sarmadi et al., 2022).

- Tire Pressure Monitoring Systems (TPMS): Tire pressure is another crucial factor in fuel efficiency. Under-inflated tires create more rolling resistance, causing vehicles to use more fuel to maintain the same speed. IoT-enabled Tire Pressure Monitoring Systems (TPMS) alert drivers and fleet managers when tire pressure drops below the optimal level, allowing for timely maintenance. Properly inflated tires not only reduce fuel consumption but also extend tire life, contributing to both economic and environmental benefits. As fuel efficiency improves, carbon emissions are reduced (Yi et al., 2020; Szczucka-Lasota et al., 2021).

- Predictive Maintenance for Engine Efficiency: IoT sensors collect data on various aspects of vehicle health, including engine performance, oil levels, and exhaust emissions. Using this data, predictive maintenance systems can identify potential issues before they lead to major breakdowns or inefficiencies. For example, if sensors detect that an engine is running hotter than usual, it could indicate a developing problem such as clogged air filters or malfunctioning components. Addressing such issues early not only prevents costly repairs but also ensures that the engine operates at optimal efficiency, reducing fuel consumption and emissions (Kong et al., 2020)

- Reducing Downtime and Unnecessary Trips: Unscheduled vehicle breakdowns often lead to delays, additional trips, or inefficient use of resources, all of which increase emissions. Predictive maintenance helps minimize vehicle downtime by scheduling maintenance only when necessary, based on actual data rather than predetermined intervals. This reduces the likelihood of unexpected breakdowns and ensures that vehicles are always running efficiently. By keeping vehicles in peak condition, logistics companies can reduce the number of additional trips or repairs, directly contributing to lower emissions (Kovaleva et al., 2020; Srebrenkoska et al., 2023).

- Emission Control Systems and IoT: Many vehicles are equipped with emission control systems that reduce the output of harmful gases like carbon dioxide (CO₂), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and particulate matter. IoT sensors monitor the performance of these systems to ensure they are functioning properly. If an emission control component, such as a catalytic converter, starts to underperform, the system will alert fleet managers, allowing for timely repairs or replacements. This ensures that vehicles continue to meet emission standards, reducing their overall environmental impact (Ge et al., 2023).

- Real-time Traffic and Route Data: IoT systems provide real-time data on traffic conditions, road closures, and weather, allowing fleet managers to adjust routes dynamically. By avoiding traffic congestion and selecting the most efficient routes, vehicles can reduce idling time, minimize distance traveled, and conserve fuel. Route optimization not only saves time and operational costs but also reduces the overall carbon footprint of logistics operations.

- Dynamic Load Management: IoT technologies also enable more efficient load management. By collecting data on vehicle capacity, cargo weight, and delivery schedules, IoT systems can help optimize loading and reduce the number of trips required. Proper load distribution reduces the strain on engines, improving fuel efficiency and lowering emissions.

- Smart Inventory Management: IoT-based inventory management systems enable real-time tracking and monitoring of goods as they move through the warehouse. RFID tags and sensors placed on products or storage racks communicate with centralized software to provide accurate, real-time data on stock levels, product location, and demand patterns. This data helps optimize warehouse layouts and reduce unnecessary movements, which in turn minimizes the energy required to operate machinery like forklifts or conveyor belts. For instance, automated systems can ensure that frequently moved products are stored closer to shipping areas, reducing the travel time and energy needed to pick and pack orders. By reducing the overall operational time and minimizing manual intervention, these smart systems reduce energy consumption and lower emissions (Soltanirad et al., 2022; Mishra and Mohapatro, 2020).

- Automated Guided Vehicles (AGVs): Automated Guided Vehicles, which are equipped with IoT sensors, are used in warehouses to move goods from one location to another without human intervention. These vehicles follow optimized paths that reduce energy consumption by minimizing unnecessary movements and avoiding congestion. Unlike traditional forklifts or manual carts, AGVs can work 24/7, and their routes and tasks can be continually optimized in real-time, based on IoT data. AGVs are typically powered by electricity, and when combined with energy-efficient charging systems, they can significantly reduce the carbon emissions associated with goods movement inside the warehouse. Furthermore, their precision and efficiency result in fewer mistakes and less waste, further contributing to sustainability goals (Patricio and Mendes, 2020; Yu and Yang, 2022 ).

- Robotic Systems: IoT-enabled robotic systems are increasingly used in warehouses for tasks such as picking, packing, and sorting goods. These systems rely on real-time data and AI algorithms to ensure optimal performance, reducing the need for human labor and cutting down on energy-intensive manual processes. Robotics systems can work around the clock without requiring breaks, making them more efficient in terms of energy use compared to traditional labor models. By reducing human intervention, these systems also minimize the need for heating, cooling, and lighting in specific areas of the warehouse, further contributing to energy savings. The precision and accuracy of these robotic systems help reduce errors and waste, further reducing the warehouse’s environmental footprint (Liu et al., 2022; Subrahmanyam et al., 2021).

- Smart Lighting Systems: IoT-enabled lighting systems can reduce energy waste by using sensors to detect motion and adjust lighting accordingly. Instead of keeping all lights on 24/7, smart lighting systems only activate in areas where workers or equipment are present. Additionally, these systems can adjust brightness based on the time of day or the amount of natural light available, further reducing electricity consumption. By reducing unnecessary energy use, smart lighting systems lower both operational costs and the carbon footprint of warehouse facilities. The integration of LEDs, which consume significantly less energy than traditional lighting solutions, further amplifies these benefits.

- Climate Control and HVAC Optimization: Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems are one of the largest energy consumers in warehouses, especially in facilities that store temperature-sensitive goods. IoT sensors can monitor temperature, humidity, and other environmental conditions in real-time, allowing the system to adjust HVAC operations as needed. For instance, climate control can be localized, so only specific areas of the warehouse that require heating or cooling are targeted, reducing the overall energy load. Moreover, IoT sensors can predict and preemptively adjust climate settings based on external weather conditions or anticipated changes in warehouse occupancy. This level of precision ensures that energy is not wasted on overcooling or overheating large spaces, thus reducing carbon emissions.

- Predictive Maintenance: IoT also enables predictive maintenance for energy-intensive warehouse equipment. Sensors installed on machinery like conveyor belts, forklifts, and HVAC systems can collect data on equipment performance. By analyzing this data, IoT systems can predict when a piece of equipment is likely to fail or become inefficient, allowing for timely maintenance that prevents excessive energy consumption. Predictive maintenance ensures that machines operate at optimal efficiency, reducing energy waste. It also extends the lifespan of equipment, minimizing the environmental impact associated with manufacturing and transporting new machinery.

- Fleet Management and Route Optimization: IoT-enabled GPS trackers and sensors provide real-time data on vehicle locations, fuel consumption, and traffic conditions. This data allows logistics companies to optimize delivery routes, reducing unnecessary travel distances and fuel consumption. By cutting down on fuel usage, companies can significantly reduce their carbon emissions.

- Energy-Efficient Warehousing: IoT systems can monitor and control energy use in warehouses by optimizing lighting, heating, and cooling systems. Smart sensors detect when certain areas are unoccupied and automatically adjust the energy use, thereby reducing electricity consumption and lowering the carbon footprint of warehousing operations.

- Predictive Maintenance: IoT sensors installed in vehicles and machinery can monitor the condition of assets in real time, predicting potential failures before they happen. This reduces the need for emergency repairs and ensures that vehicles and equipment operate at peak efficiency, resulting in lower fuel consumption and reduced emissions.

- Supply Chain Transparency and Efficiency: IoT devices can track products throughout the supply chain, providing insights into where delays or inefficiencies occur. By identifying these bottlenecks, logistics companies can streamline their operations, reducing unnecessary storage times and transportation legs, which, in turn, lowers energy consumption and emissions.

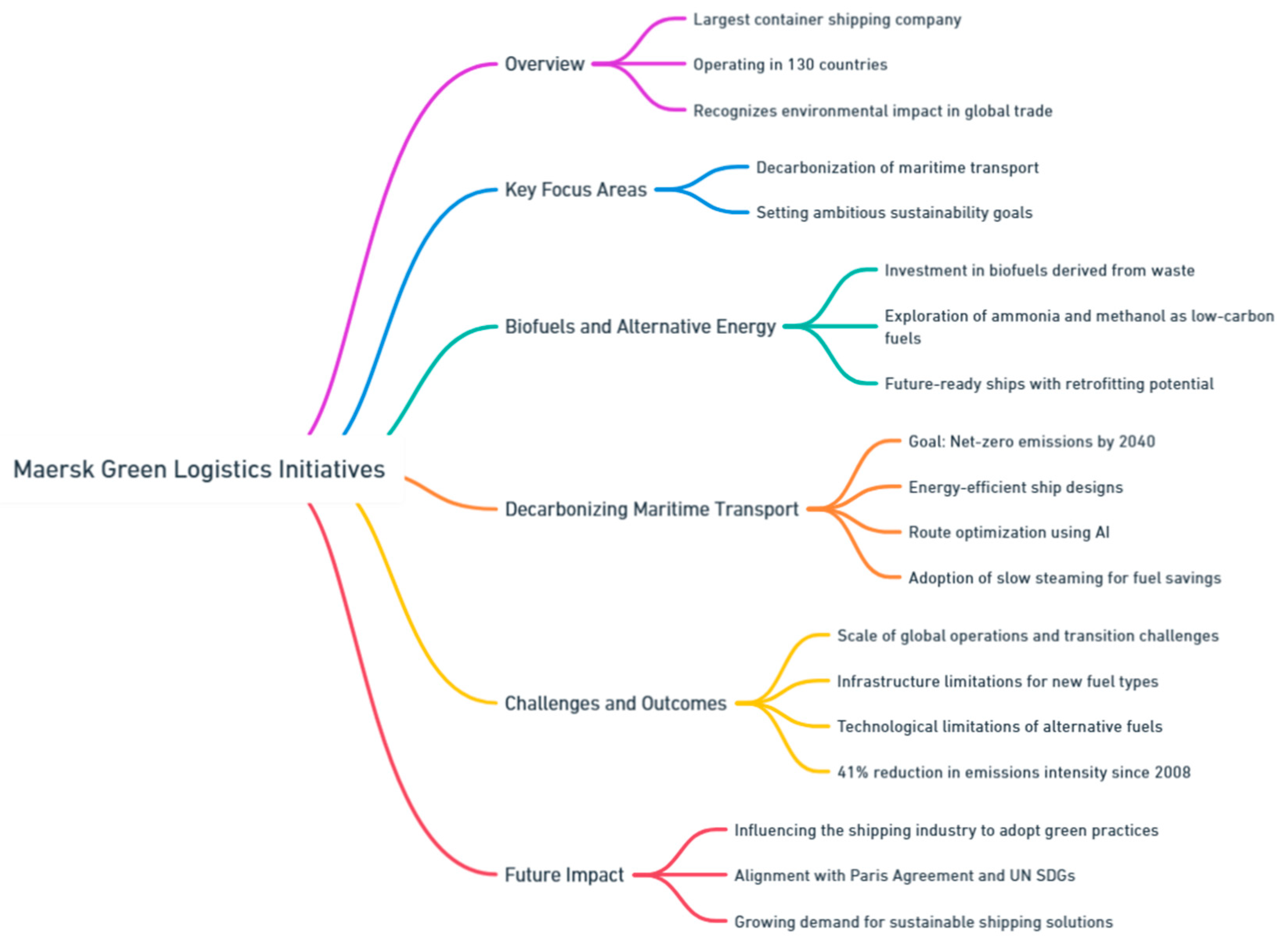

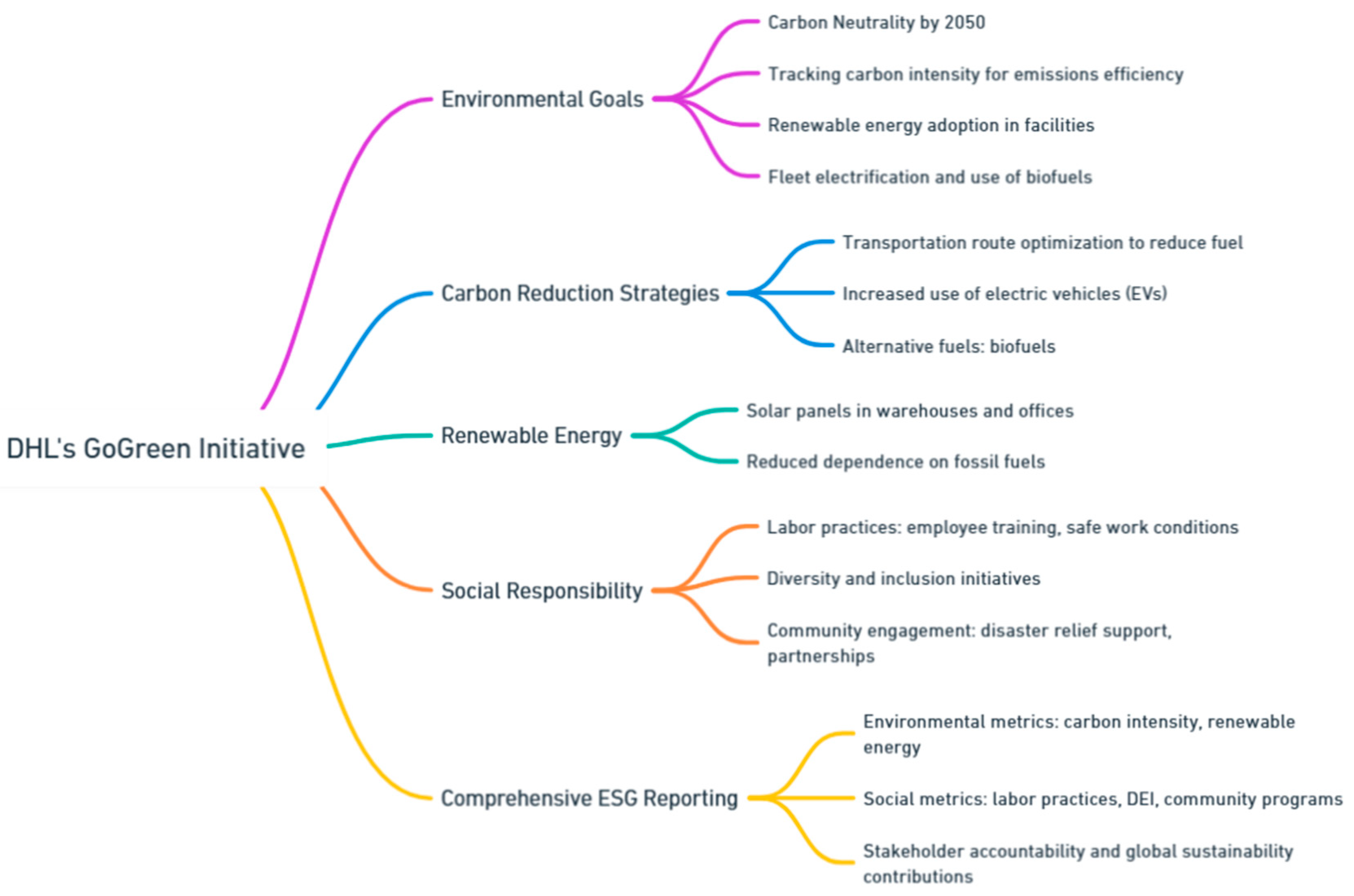

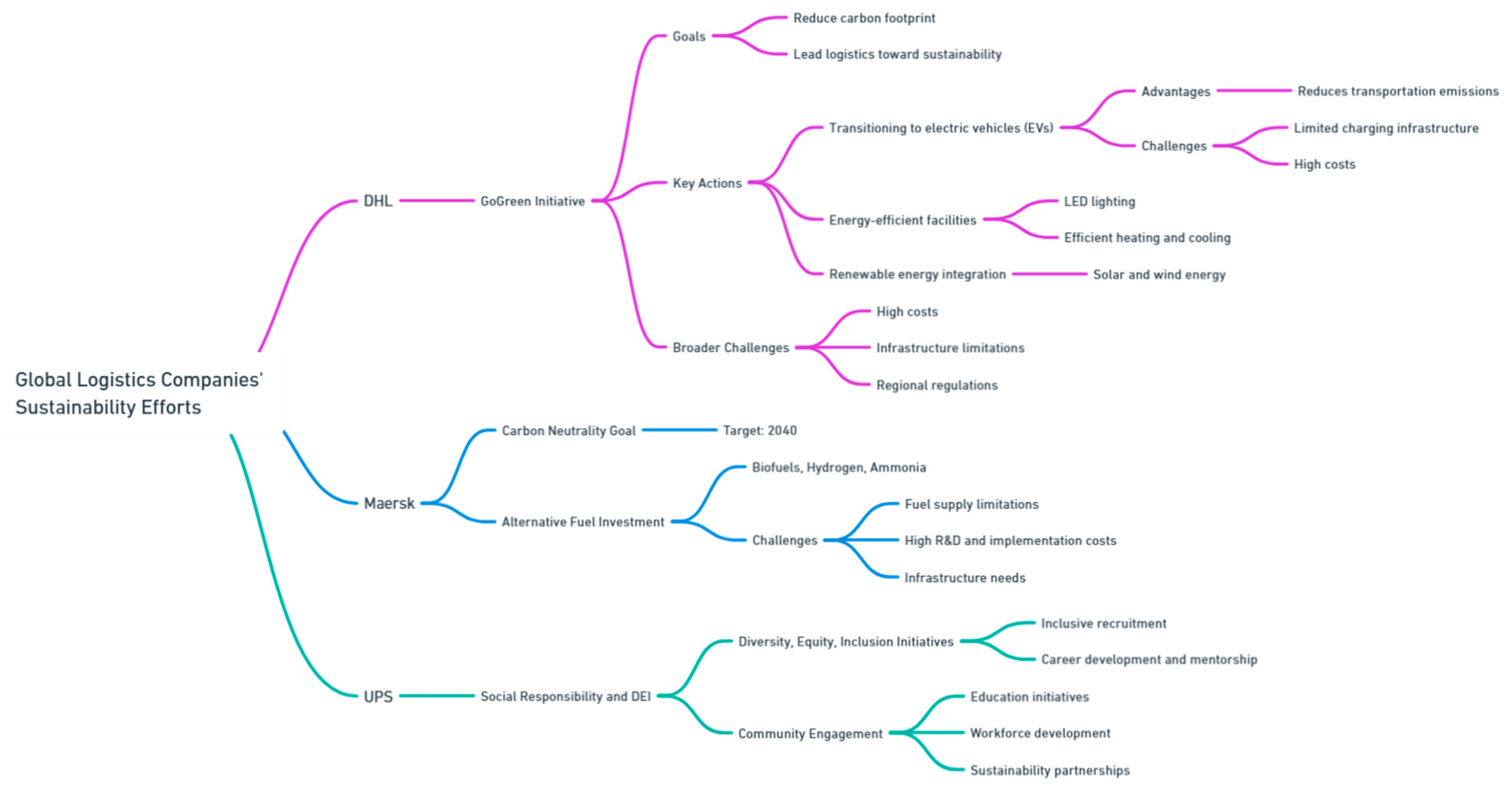

- Smart Trucking and Fleet Optimization: One of DHL’s key sustainability initiatives is its use of IoT in smart trucking. DHL has implemented IoT-enabled GPS tracking and telematics systems in its delivery trucks to monitor real-time vehicle data such as fuel consumption, speed, engine performance, and route efficiency. By analyzing this data, DHL can optimize delivery routes to minimize travel distances, reduce fuel consumption, and lower emissions. Additionally, IoT-enabled fleet management helps DHL identify underperforming vehicles that may require maintenance or upgrades, further improving fuel efficiency. DHL’s smart trucking initiative is part of its GoGreen program, which aims to reduce logistics-related emissions through cleaner transport solutions and optimized operations. As a result of these efforts, DHL has reported a significant reduction in fuel usage and CO₂ emissions across its global fleet.

- Smart Warehousing with IoT Sensors. DHL has also integrated IoT technology into its warehousing operations to reduce energy consumption. In several of its distribution centers, DHL has installed smart sensors that monitor temperature, lighting, and occupancy levels. These sensors automatically adjust the lighting and HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) systems based on real-time data. For example, when certain areas of the warehouse are unoccupied, the IoT system reduces lighting and cooling in those areas, leading to significant energy savings. Moreover, IoT systems are used to optimize the layout of warehouses by analyzing the flow of goods. This reduces the amount of time forklifts and other machinery spend moving around the facility, cutting down on energy use and emissions from warehouse operations.

- IoT for Predictive Maintenance: To further improve the efficiency of its operations, DHL has implemented IoT-driven predictive maintenance across its fleet and machinery. By installing IoT sensors on vehicles and equipment, DHL can monitor the performance and condition of assets in real time. These sensors detect early signs of wear and tear, allowing DHL to schedule maintenance proactively rather than reactively. This approach reduces downtime, increases the longevity of equipment, and ensures that vehicles and machinery operate at optimal efficiency.

- How Predictive Analytics Works in Demand Forecasting: Predictive analytics involves the use of AI and ML algorithms to analyze large datasets and identify patterns. These algorithms process historical sales data, current market trends, customer behavior, seasonality, and external factors such as economic conditions or even weather forecasts. By analyzing these complex relationships, AI-powered systems can generate highly accurate demand forecasts, allowing companies to anticipate changes in demand and adjust their logistics and inventory strategies accordingly. For instance, a retail company can use predictive analytics to anticipate which products will be in high demand during peak seasons, such as holidays or back-to-school periods. This helps logistics providers ensure that enough inventory is available in warehouses and distribution centers ahead of time, minimizing the risk of delays or stock shortages.

- Benefits of AI and ML in Demand Forecasting: Improved Accuracy: AI and ML can process much larger volumes of data and analyze complex variables that traditional forecasting methods cannot. This results in more precise demand predictions, helping businesses avoid costly errors such as overstocking or understocking. Real-Time Adaptation: AI-driven demand forecasting systems can update predictions in real-time based on new data inputs, such as sudden shifts in consumer behavior or unexpected supply chain disruptions. This allows companies to respond dynamically to changing market conditions, improving flexibility and resilience. Enhanced Supply Chain Coordination: Accurate demand forecasting enables better coordination between different parts of the supply chain, from suppliers and manufacturers to distribution centers and retailers. This results in smoother operations and fewer disruptions, ultimately improving customer satisfaction.

- AI-Driven Inventory Management: With predictive demand analytics, logistics managers can optimize inventory management by ensuring that products are available where they are needed most. For example, AI algorithms can suggest which warehouses should stock specific products based on forecasted regional demand, helping reduce storage costs and ensuring faster delivery times. Additionally, predictive analytics can help reduce the costs associated with unsold goods by better aligning inventory levels with actual market demand.

- How AI and ML Enhance Route Optimization: Traditional route planning typically relies on static maps and pre-determined delivery schedules. However, AI-powered systems can process real-time data and adapt routes dynamically to changing conditions. Machine learning algorithms use historical data to predict traffic congestion, road hazards, or weather delays, enabling logistics managers to reroute vehicles in real-time to avoid disruptions. For example, an AI-based route optimization system can detect a traffic jam ahead on a delivery route and immediately suggest an alternative path, helping the driver avoid delays and reduce fuel consumption. This flexibility not only improves delivery times but also leads to more efficient fuel usage, which is both cost-effective and environmentally friendly.

- Dynamic Route Planning and Real-Time Adjustments: AI and ML allow logistics companies to plan delivery routes more intelligently, taking into account multiple variables simultaneously. In addition to traffic conditions, these systems can factor in vehicle capacity, delivery time windows, and customer preferences to create highly optimized delivery plans. Moreover, real-time adjustments can be made if conditions change, such as unexpected weather events or customer cancellations, ensuring that routes remain efficient and cost-effective throughout the day.

- Benefits of AI-Driven Route Optimization: AI-driven route optimization systems enhance fuel efficiency by optimizing routes and reducing the number of miles driven, significantly lowering fuel consumption. This not only reduces operational costs but also contributes to sustainability efforts by minimizing the logistics industry's carbon footprint. Additionally, faster and more efficient delivery routes lead to improved delivery times, which are crucial for meeting customer expectations, especially in e-commerce and last-mile delivery sectors. Cost savings are another benefit of AI-based route optimization, as it reduces the need for excess transportation resources, such as drivers and vehicles. Fewer miles traveled mean less wear and tear on vehicles, lower fuel costs, and a decreased need for additional personnel. Moreover, AI and machine learning provide increased flexibility, enabling logistics companies to respond to real-time events, such as last-minute orders or sudden changes in delivery schedules, without sacrificing efficiency. This flexibility allows businesses to remain agile in a highly competitive market.

- Autonomous Vehicles and Drones: AI and ML are also playing a key role in the development of autonomous vehicles and drones for logistics. These technologies use real-time data from sensors and cameras to navigate complex environments and deliver goods without human intervention. Autonomous vehicles and drones have the potential to further reduce costs, improve safety, and enhance the efficiency of last-mile deliveries.

4.4.2. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Logistics: Autonomous Vehicles and Drones for Low-Emission Deliveries

- Reduced Carbon Emissions: Many autonomous delivery vehicles are designed to be electric, contributing to a significant reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. Electric vehicles (EVs) produce zero tailpipe emissions, making them an environmentally friendly alternative to conventional fuel-powered delivery trucks. As the global logistics industry faces increasing pressure to reduce its carbon footprint, AVs powered by clean energy will play a vital role in creating more sustainable supply chains.

- Fuel Efficiency: Even when autonomous vehicles use hybrid or conventional fuel systems, their AI-driven navigation and driving systems optimize fuel usage. AVs are capable of selecting the most fuel-efficient routes, reducing idling times in traffic, and maintaining optimal speeds, all of which contribute to improved fuel efficiency. Over time, these incremental improvements in fuel consumption can lead to significant reductions in overall emissions.

- Reduced Traffic Congestion: Autonomous vehicles can communicate with one another through Vehicle-to-Vehicle (V2V) communication, enabling more efficient traffic flow and reducing congestion. When delivery vehicles can coordinate their movements, fewer stops and starts occur, lowering fuel consumption and emissions. AI-driven route optimization systems also allow AVs to avoid traffic hotspots and congestion, ensuring that deliveries are made faster and more sustainably.

- Zero Emissions: Drones are typically powered by electricity, meaning they produce zero direct emissions. In urban areas where delivery trucks contribute to air pollution and traffic congestion, drones offer a cleaner, more environmentally friendly alternative. By reducing the reliance on fuel-powered vehicles for short-distance deliveries, drones help reduce the overall carbon footprint of the logistics sector.

- Energy Efficiency: Drones require significantly less energy than traditional delivery vehicles to transport lightweight goods over short distances. Their ability to bypass roads and traffic further increases their efficiency, allowing them to make quick, energy-efficient deliveries. For instance, delivering a small package via drone is far more energy-efficient than using a truck, which consumes more fuel and emits more CO₂ during stop-and-go urban deliveries.

- Faster Delivery Times: Drones can deliver goods more quickly than traditional ground-based methods, especially in areas with heavy traffic or limited road access. By providing rapid and direct delivery routes, drones can minimize the time spent on each delivery, reducing fuel consumption and emissions. Additionally, faster delivery times can lead to higher customer satisfaction, which is increasingly important in the era of e-commerce and on-demand services.

- Access to Remote Areas: Drones are particularly useful for delivering goods to remote or hard-to-reach locations where traditional vehicles cannot easily go. This capability not only improves delivery efficiency but also reduces the need for long and energy-intensive trips by fuel-powered trucks or vans, further lowering emissions (Rejeb et al., 2023; Li et al., 2020).

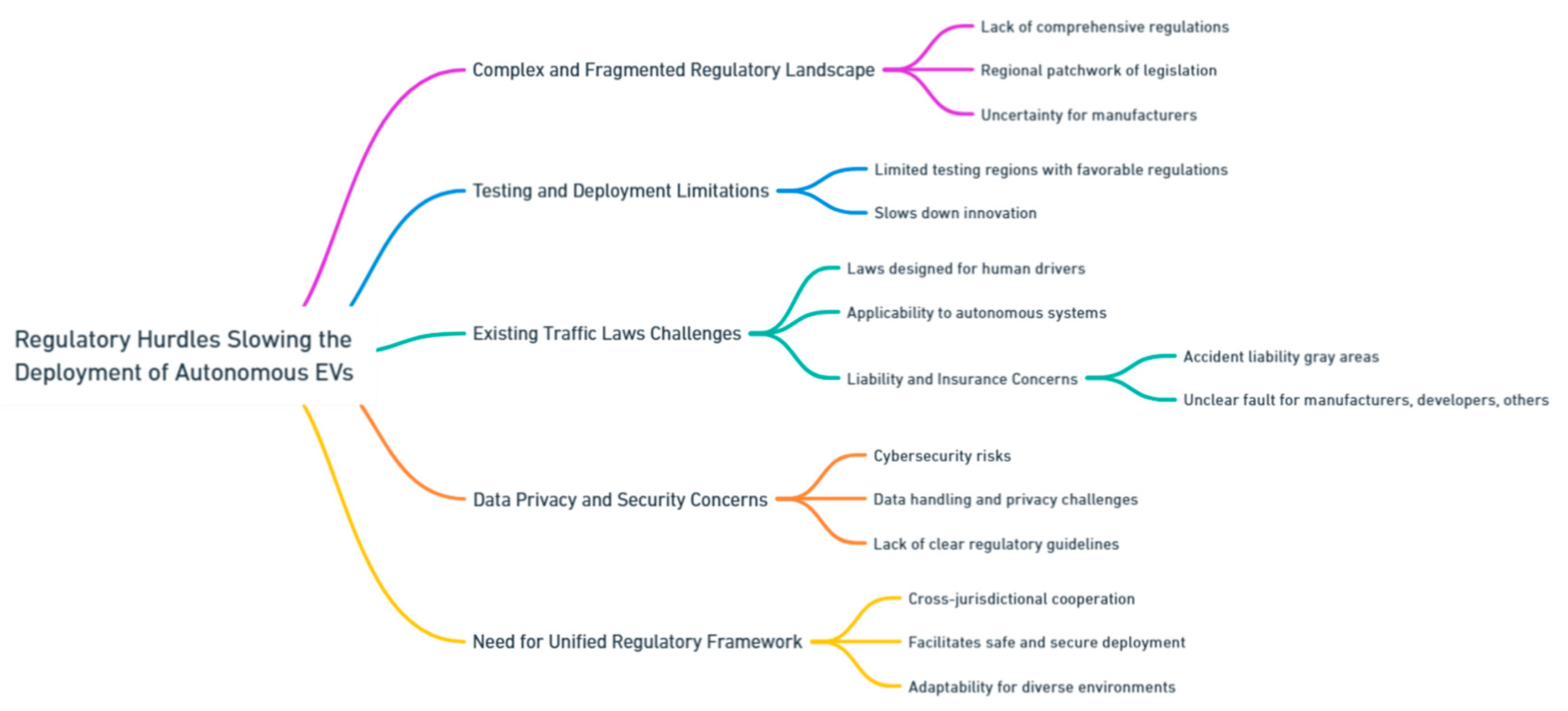

- Regulatory and Legal Hurdles: The widespread adoption of autonomous vehicles and drones for deliveries is currently limited by regulatory and legal restrictions. Governments and regulatory bodies are still developing the frameworks needed to ensure the safe and ethical use of these technologies. Concerns about safety, privacy, and airspace control need to be addressed before AVs and drones can become mainstream in logistics.

- Infrastructure Development: The deployment of autonomous vehicles and drones requires substantial infrastructure development, including charging stations for electric AVs and drone delivery hubs. Cities and logistics providers must invest in this infrastructure to enable the widespread use of these technologies.

- Public Acceptance: Gaining public trust and acceptance is another challenge for autonomous delivery vehicles and drones. People may have concerns about safety, data privacy, and job displacement as these technologies become more prevalent in logistics.

4.4.3. AI’s Impact on Reducing Energy Consumption in Warehouses

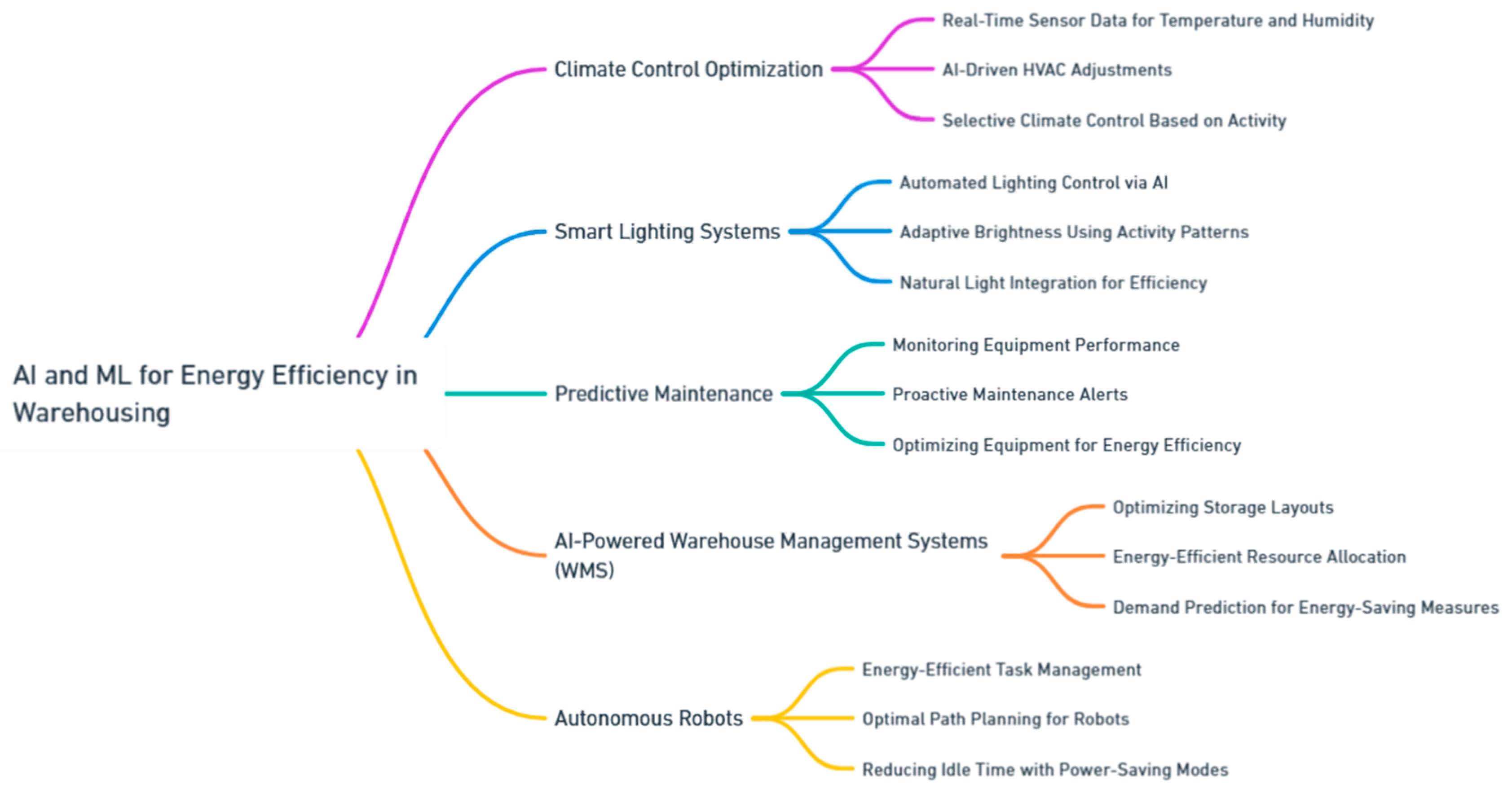

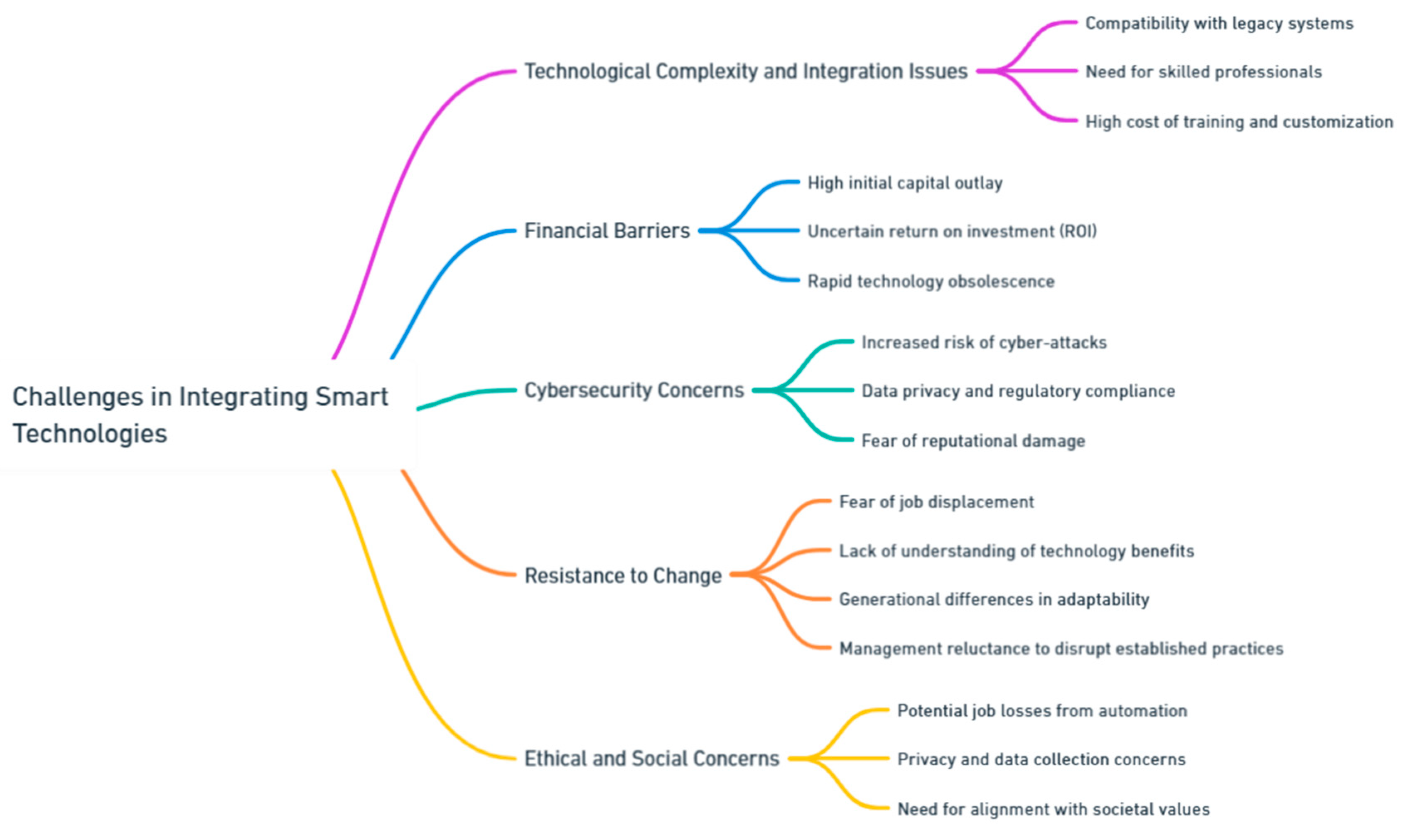

- Optimizing Climate Control Systems: One of the most energy-consuming aspects of a warehouse is the climate control system. Heating, cooling, and ventilation are necessary to maintain a stable environment, especially in cold storage facilities. AI and ML can help optimize the performance of these systems by analyzing large amounts of data from sensors placed throughout the warehouse. These sensors track temperature, humidity, airflow, and energy use in real time. Using this data, AI-driven systems can learn patterns of energy consumption and identify opportunities to reduce waste. For instance, AI can adjust HVAC systems based on external weather conditions, the time of day, and occupancy levels. It can also predict when certain areas of the warehouse will be less active, allowing for selective climate control rather than maintaining the same temperature across the entire facility. These dynamic adjustments reduce unnecessary energy use, improve efficiency, and maintain optimal conditions for the goods stored inside (Domingues et al., 2023; Yayla et al., 2022).

- Smart Lighting Systems: Lighting is another significant contributor to energy consumption in warehouses, especially in large facilities that operate around the clock. Traditionally, warehouses have relied on manual or time-based lighting systems that may not always align with actual usage patterns. AI-powered smart lighting systems can revolutionize this by automating lighting control based on real-time data. AI systems can use sensors and cameras to detect human presence and activity levels in different parts of the warehouse. By integrating with ML algorithms, these systems can learn usage patterns and predict when certain areas are likely to be occupied, allowing them to adjust lighting accordingly. For example, AI could dim or turn off lights in areas that are not in use and increase brightness in areas with high activity. This level of precision helps reduce energy consumption while ensuring that the warehouse remains safe and well-lit during operations. Additionally, AI-driven systems can leverage natural light by adjusting artificial lighting based on the amount of sunlight entering the warehouse. This dynamic control further reduces energy consumption, particularly during daylight hours (Vaidya et al., 2021; Elkhoukhi et al., 2022).

- Predictive Maintenance for Energy-Efficient Equipment: Material handling equipment such as conveyors, forklifts, and automated storage and retrieval systems (AS/RS) are critical for warehouse operations, but they also consume significant energy. Inefficient or poorly maintained equipment can lead to excessive energy use and higher operational costs. AI and ML can play a vital role in ensuring that equipment operates at peak efficiency through predictive maintenance. Predictive maintenance involves using AI algorithms to analyze data from sensors embedded in warehouse equipment. These sensors monitor the performance of machinery, such as motor speed, temperature, and energy consumption, and detect patterns that may indicate a future breakdown or efficiency loss. By predicting when a piece of equipment is likely to fail or operate less efficiently, AI systems can alert warehouse managers to schedule maintenance proactively. This approach reduces downtime, extends the life of the equipment, and ensures that machines are operating at optimal energy efficiency. Moreover, by avoiding unexpected equipment failures, AI-driven predictive maintenance minimizes disruptions in warehouse operations, leading to smoother workflows and less energy waste associated with inefficient processes or machinery breakdowns (Bermeo-Ayerbe et al., 2022; Çınar et al., 2020).

- AI-Powered Warehouse Management Systems (WMS): AI-powered Warehouse Management Systems (WMS) are increasingly being used to optimize warehouse operations, including energy consumption. These systems can analyze vast amounts of data related to inventory levels, order fulfillment, and equipment usage, allowing warehouse managers to make smarter decisions about how to allocate resources. AI-driven WMS can help reduce energy consumption by optimizing storage layouts, reducing the distance that forklifts and other equipment must travel to retrieve items. By streamlining these processes, AI-powered WMS reduce the energy required for material handling and order picking, further contributing to overall energy savings. Additionally, AI can predict peaks in demand and suggest energy-saving measures during periods of lower activity, ensuring that energy use is proportional to the actual needs of the warehouse at any given time (Khan et al., 2023).

- Autonomous Robots and Energy Efficiency: Autonomous robots are increasingly being used in warehouses for tasks such as picking, packing, and transporting goods. These robots, powered by AI and ML, are designed to work efficiently with minimal energy use. Unlike traditional manual equipment, which may be left running idle between tasks, autonomous robots can power down or enter energy-saving modes when not in use. Furthermore, AI algorithms can optimize the paths taken by robots to reduce the distance traveled and the energy consumed. For instance, AI systems can calculate the most efficient routes for robots to pick and deliver items, minimizing both time and energy usage. This not only improves operational efficiency but also significantly reduces energy consumption, particularly in large warehouses with high volumes of daily activity (Song and Xin, 2021).

4.4.4. Case Study: Amazon's AI-Powered Logistics Solutions

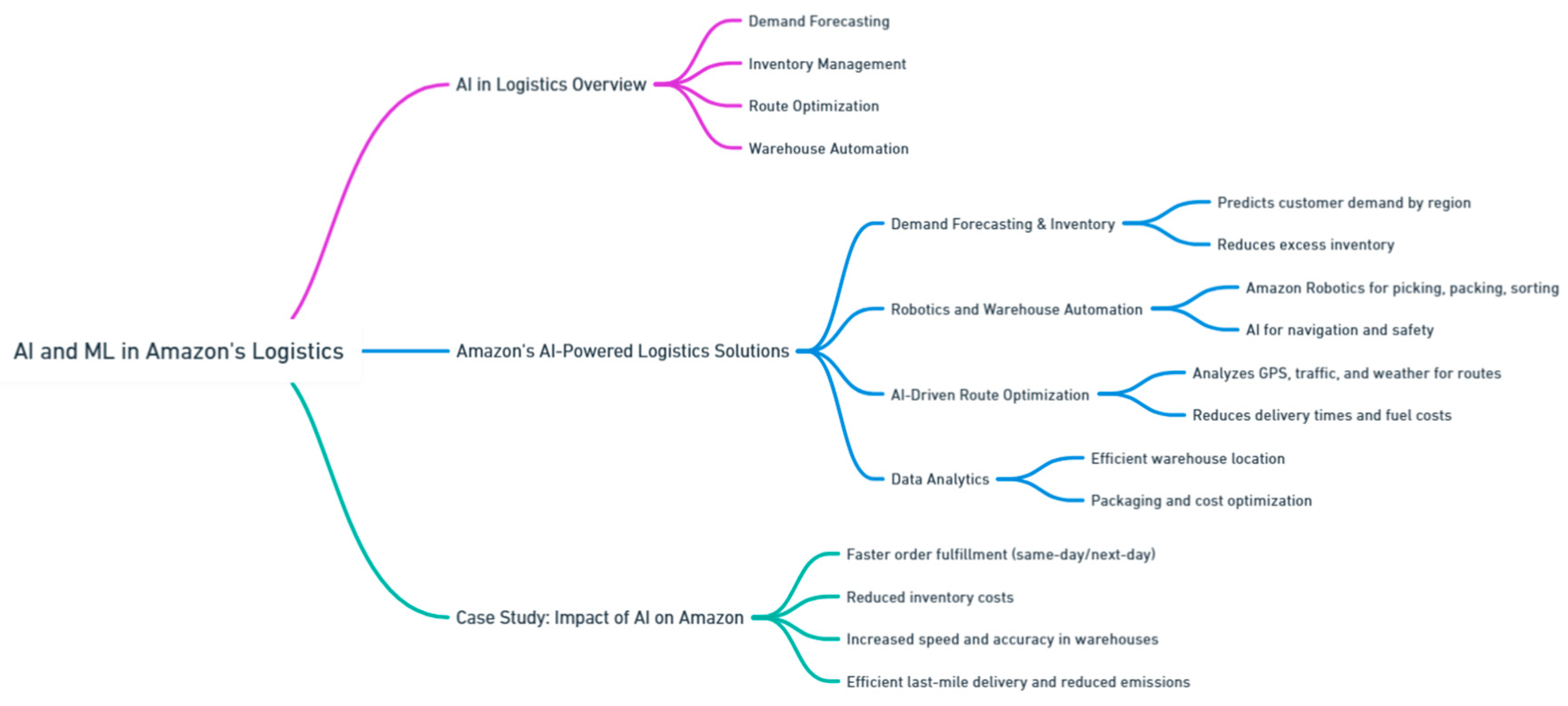

- Demand Forecasting and Inventory Management: Amazon uses sophisticated AI algorithms to predict customer demand accurately. By analyzing past purchase data, browsing patterns, and even external factors like market trends and seasonal changes, Amazon can anticipate which products will be in demand in specific regions. This predictive accuracy ensures that warehouses are stocked efficiently, reducing the need for excess inventory and minimizing stockouts.

- Robotics and Automation in Warehouses: One of Amazon’s hallmark AI innovations is its use of robots in fulfillment centers. In 2012, Amazon acquired Kiva Systems, now known as Amazon Robotics, which produces robots that automate tasks such as picking, packing, and sorting products. These robots, powered by AI, move shelves of products to human workers, drastically reducing the time and effort required for order fulfillment. AI also helps these robots navigate warehouses without collisions, improving efficiency and safety.

- AI-Powered Route Optimization for Last-Mile Delivery: Last-mile delivery, the final leg of the shipping process, is often the most complex and expensive part of logistics. Amazon uses AI to optimize this phase, analyzing data from GPS, traffic conditions, delivery preferences, and weather forecasts to determine the most efficient delivery routes. This AI-driven approach reduces delivery times, cuts fuel costs, and enhances customer satisfaction by providing more accurate delivery windows.

- Data Analytics and Machine Learning Algorithms : Amazon collects massive amounts of data from its operations, and AI-powered analytics tools sift through this data to uncover patterns, predict trends, and make real-time decisions. For instance, machine learning models help in determining the most efficient warehouse locations, optimizing packaging for minimal shipping costs, and identifying bottlenecks in the supply chain (Gandhi et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2022).

4.4.5. Tracking and Optimizing Supply Chain Emissions Using Big Data

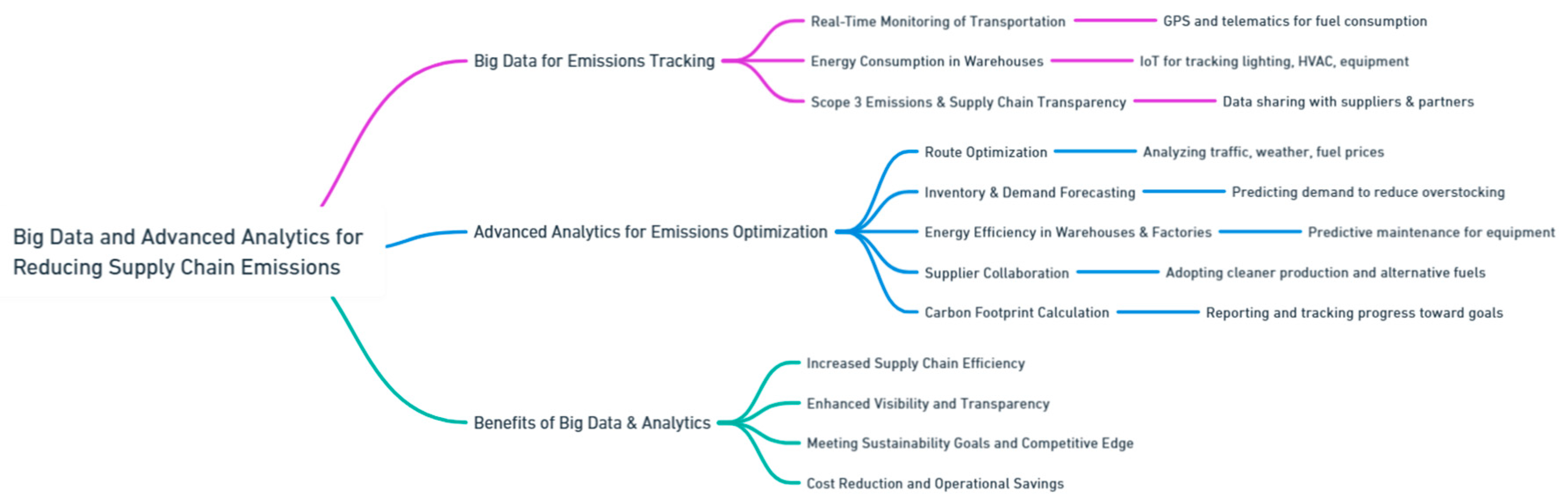

- Real-Time Monitoring of Transportation Emissions: Big Data analytics tools can collect real-time information from GPS devices and vehicle telematics systems to monitor fuel consumption, driving patterns, and vehicle performance. By tracking data such as miles traveled, fuel efficiency, and idle times, companies can calculate the carbon emissions of each trip and identify inefficiencies in the transportation network. For example, a logistics company could use this data to optimize routes, reduce fuel consumption, and minimize unnecessary trips, resulting in lower emissions.

- Energy Consumption in Warehouses: IoT sensors installed in warehouses can monitor energy consumption for lighting, heating, cooling, and equipment usage. Big Data analytics can then process this data to identify areas where energy efficiency improvements can be made, such as optimizing HVAC systems, using energy-efficient lighting, or automating equipment to reduce idle times. By tracking energy use in real time, companies can reduce emissions associated with warehouse operations.

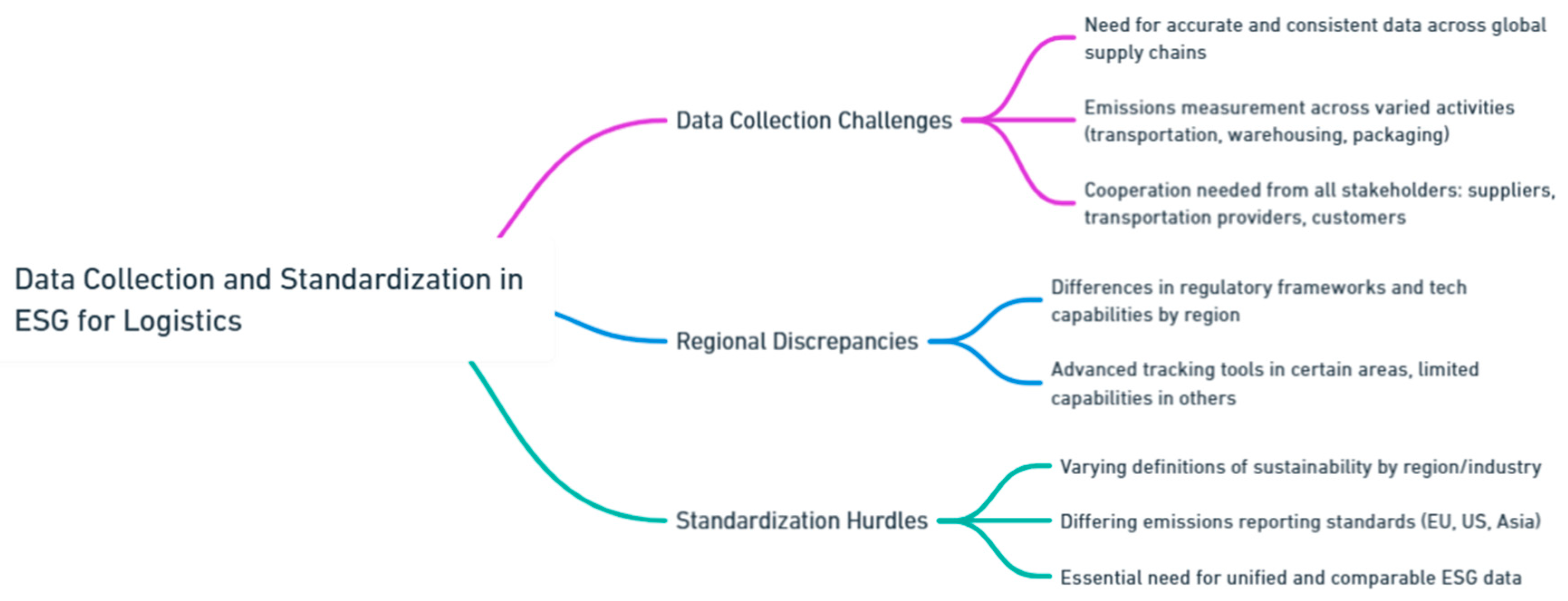

- Supply Chain Transparency and Scope 3 Emissions: One of the most difficult aspects of tracking supply chain emissions is calculating Scope 3 emissions, which include indirect emissions from activities such as supplier production, purchased goods, and transportation services. Big Data enables companies to collect information from their suppliers and third-party logistics providers, giving them better visibility into the environmental impact of their entire supply chain. For example, a manufacturer can track the energy use of its suppliers and transportation providers, allowing them to work together to reduce emissions (Goodarzian et al., 2021; Guzman et al., 2023).

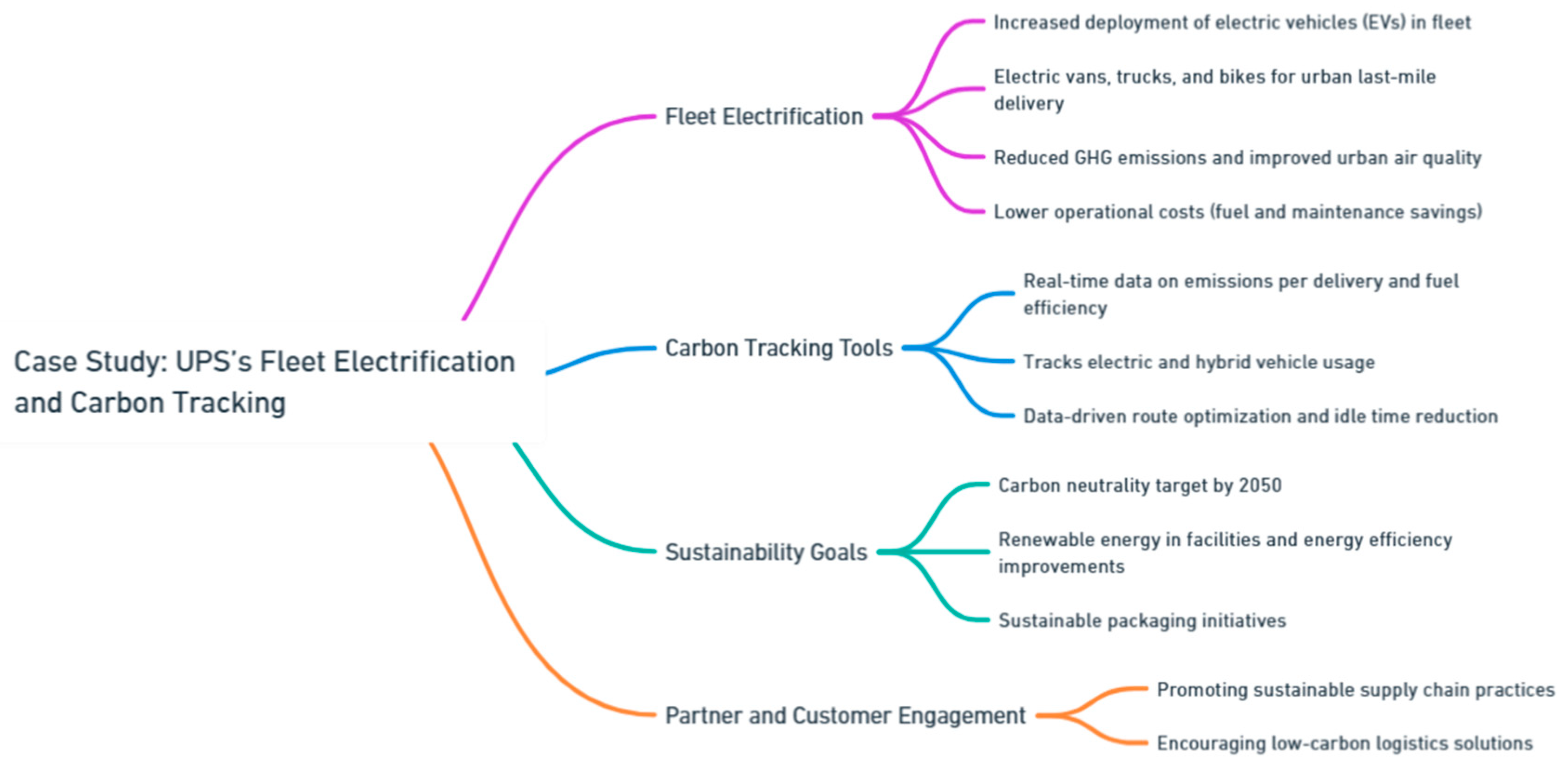

- Route Optimization: One of the most effective ways to reduce transportation emissions is through route optimization. Advanced analytics tools can process data from multiple sources, including traffic patterns, weather conditions, fuel prices, and delivery schedules, to determine the most efficient routes for vehicles. By minimizing the distance traveled and avoiding congested areas, companies can significantly reduce fuel consumption and emissions. For example, delivery companies like UPS use route optimization algorithms to reduce miles driven, resulting in lower emissions and operational costs.

- Inventory and Demand Forecasting: Excess inventory and poor demand forecasting can lead to unnecessary transportation and warehousing, both of which contribute to emissions. Advanced analytics tools can analyze historical sales data, market trends, and customer behavior to predict demand more accurately. This enables companies to optimize their inventory levels, reduce the need for rush shipments, and avoid overstocking, all of which help lower emissions associated with transportation and storage.

- Energy Efficiency Improvements: Advanced analytics can analyze energy consumption data across warehouses and factories to identify inefficiencies and recommend energy-saving strategies. For example, predictive maintenance tools can analyze data from equipment sensors to predict when machines are likely to fail or become inefficient. By addressing maintenance issues proactively, companies can improve energy efficiency and reduce emissions associated with equipment breakdowns or inefficient operations.

- Supplier and Partner Collaboration: Supply chains involve multiple stakeholders, including suppliers, manufacturers, and logistics providers. Big Data and advanced analytics tools can facilitate collaboration by sharing emissions data and identifying areas for improvement across the entire supply chain. For example, companies can work with suppliers to adopt cleaner production methods or collaborate with logistics providers to use alternative fuels. This data-driven collaboration can help reduce emissions at every stage of the supply chain.

- Carbon Footprint Calculation and Reporting: Advanced analytics can calculate the carbon footprint of products or supply chain activities by processing data from multiple sources and providing detailed reports on emissions. This is especially important for companies that need to meet regulatory requirements or achieve sustainability goals. These tools allow businesses to accurately report their emissions, monitor progress toward emission reduction targets, and identify opportunities for improvement (Sharifani et al, 2022; ALLAHHAM et al., 2023).

- Increased Efficiency: By using data to optimize routes, inventory, and energy consumption, companies can improve the overall efficiency of their supply chain operations, leading to lower emissions and cost savings.

- Enhanced Visibility and Transparency: Big Data enables companies to track emissions across their entire supply chain, including Scope 3 emissions, providing a clear picture of their environmental impact.

- Sustainability and Competitive Advantage: Companies that optimize their supply chain emissions can achieve sustainability goals, comply with regulations, and enhance their brand reputation as environmentally responsible organizations.

- Cost Reduction: Reducing emissions often goes hand-in-hand with cost savings, as optimizing fuel consumption, energy use, and inventory levels leads to lower operational costs.

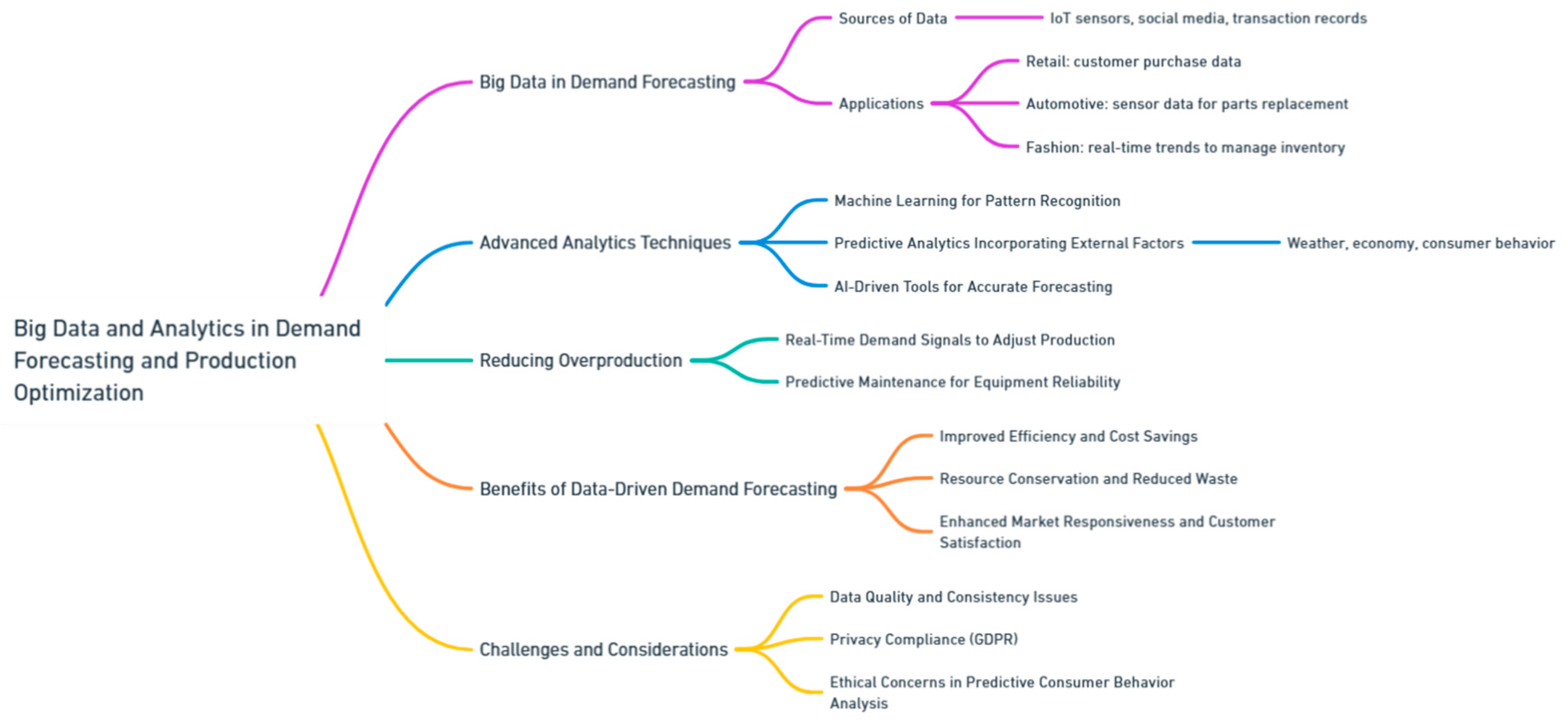

4.4.6. Big Data and Advanced Analytics: Forecasting Demand and Reducing Overproduction

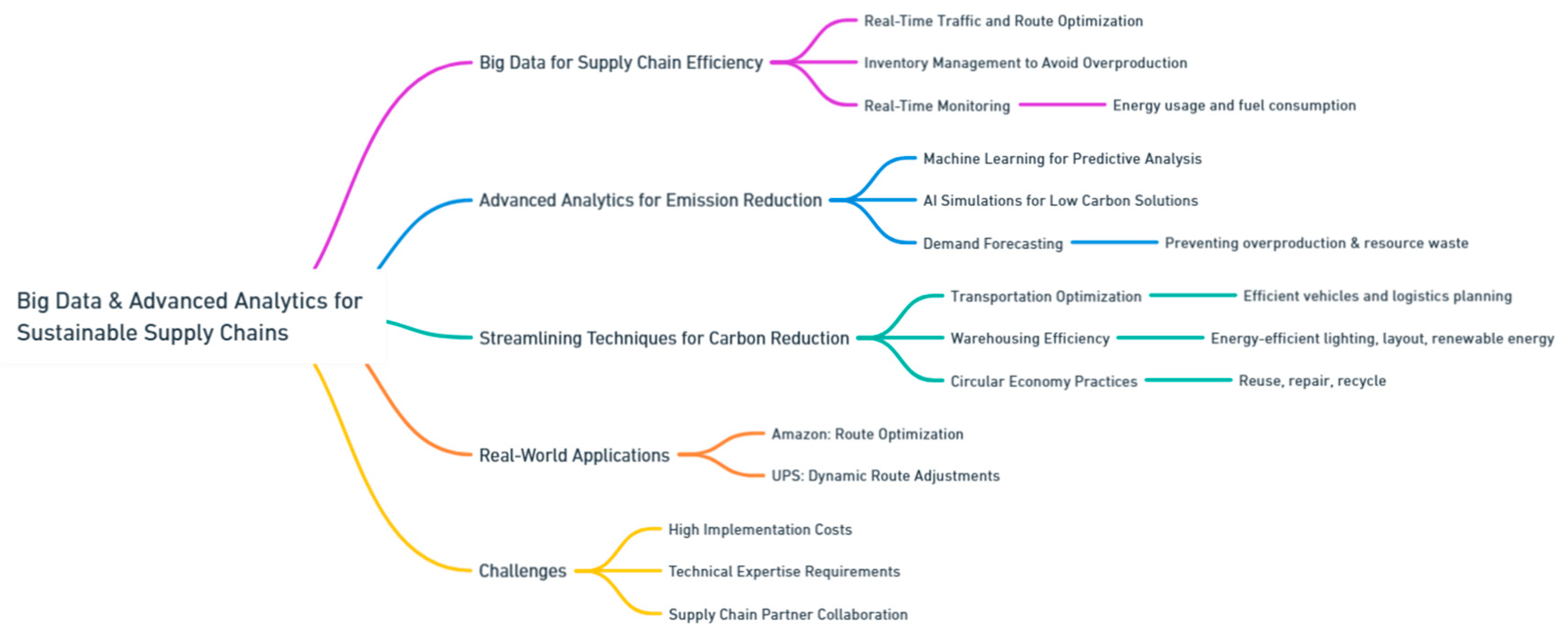

4.4.7. Big Data and Advanced Analytics in Streamlining Supply Chains to Minimize Carbon-Heavy Activities

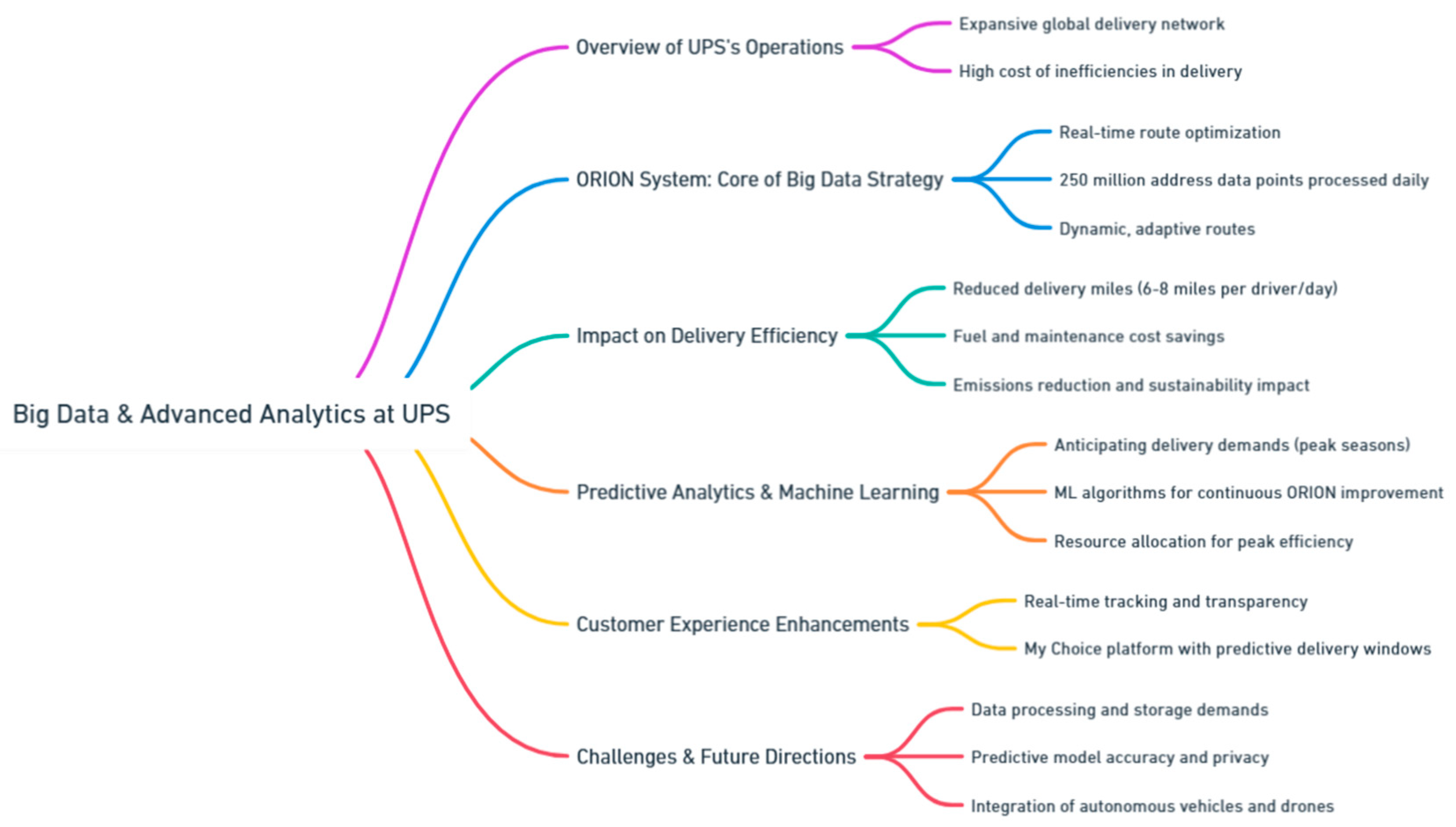

4.4.8. Big Data and Advanced Analytics: UPS Case Study

4.5. Reducing Carbon Footprint Through Smart Technologies

4.5.1. Blockchain for Green Supply Chains: Enhancing Transparency in Sourcing and Delivery Processes

- Ethical Sourcing and Sustainability Verification: Blockchain allows companies to verify that raw materials, such as minerals, cotton, or timber, are sourced from environmentally responsible and ethically sound suppliers. For example, a diamond company can use blockchain to track every diamond from the mine to the retailer, verifying that it was sourced from a conflict-free area. Similarly, a coffee company can use blockchain to trace coffee beans back to farms that use sustainable agricultural practices, ensuring that consumers are buying environmentally friendly products.

- Certification and Compliance: Blockchain can also facilitate compliance with environmental regulations and certifications. For instance, companies that are required to meet certain sustainability standards, such as the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) for paper products or Fair Trade for agricultural goods, can use blockchain to record certifications at each stage of the supply chain. This not only provides proof of compliance but also reassures consumers and regulators that sustainability claims are legitimate. Each participant in the supply chain, from farmers to manufacturers, can upload certification information, which is securely stored and accessible for verification at any time.

- Reducing Environmental Impact in Sourcing: Blockchain technology helps identify and track the carbon footprint associated with sourcing materials. By recording every step of a product's journey—from the extraction of raw materials to transportation and processing—blockchain can give companies insight into the environmental costs of their supply chain. Armed with this data, businesses can make informed decisions to minimize waste, reduce emissions, and optimize sourcing strategies for a greener footprint.

- Green Logistics Tracking: Blockchain can be integrated with Internet of Things (IoT) devices to track the environmental impact of transportation, such as fuel consumption and emissions. Each vehicle in the delivery network can be equipped with IoT sensors that monitor emissions, and this data can be securely logged in the blockchain. By analyzing this data, logistics managers can optimize routes, reduce unnecessary fuel consumption, and transition to more sustainable transportation modes, such as electric vehicles. This helps ensure that the delivery process aligns with the company’s green supply chain goals.

- Carbon Offsetting and Reporting: In cases where logistics inevitably result in carbon emissions, blockchain can provide transparency for carbon offsetting programs. If a company chooses to invest in carbon credits to neutralize its emissions, blockchain can verify that these offsets are legitimate and ensure that the funds go toward certified environmental projects. The immutable nature of blockchain ensures that companies cannot falsely claim to offset emissions, fostering trust among consumers and environmental groups.

- Waste Reduction in Packaging and Delivery: Packaging waste is a significant environmental challenge in logistics. Blockchain can help track and verify sustainable packaging practices by recording the materials used and ensuring compliance with environmental standards. Moreover, blockchain can enable a circular economy by facilitating reverse logistics processes, such as product returns and recycling efforts. With blockchain, customers and companies can track how returned products or packaging materials are recycled or disposed of in an environmentally responsible manner (Kouhizadeh et al., 2021; Munir et al., 2022).

- Increased Trust and Accountability: Blockchain’s transparency allows all stakeholders to verify sustainability claims, making it easier for companies to build trust with consumers who are increasingly concerned about the environmental and ethical impact of their purchases.

- Improved Efficiency: By streamlining processes and reducing the need for intermediaries, blockchain can make supply chains more efficient, leading to cost savings and reduced environmental impact.

- Enhanced Regulatory Compliance: Blockchain helps businesses comply with environmental laws and regulations by providing a verifiable record of their sustainability efforts and certifications.

- Better Decision-Making: With greater visibility into every step of the supply chain, businesses can make more informed decisions about sourcing, manufacturing, and logistics to minimize their environmental impact.

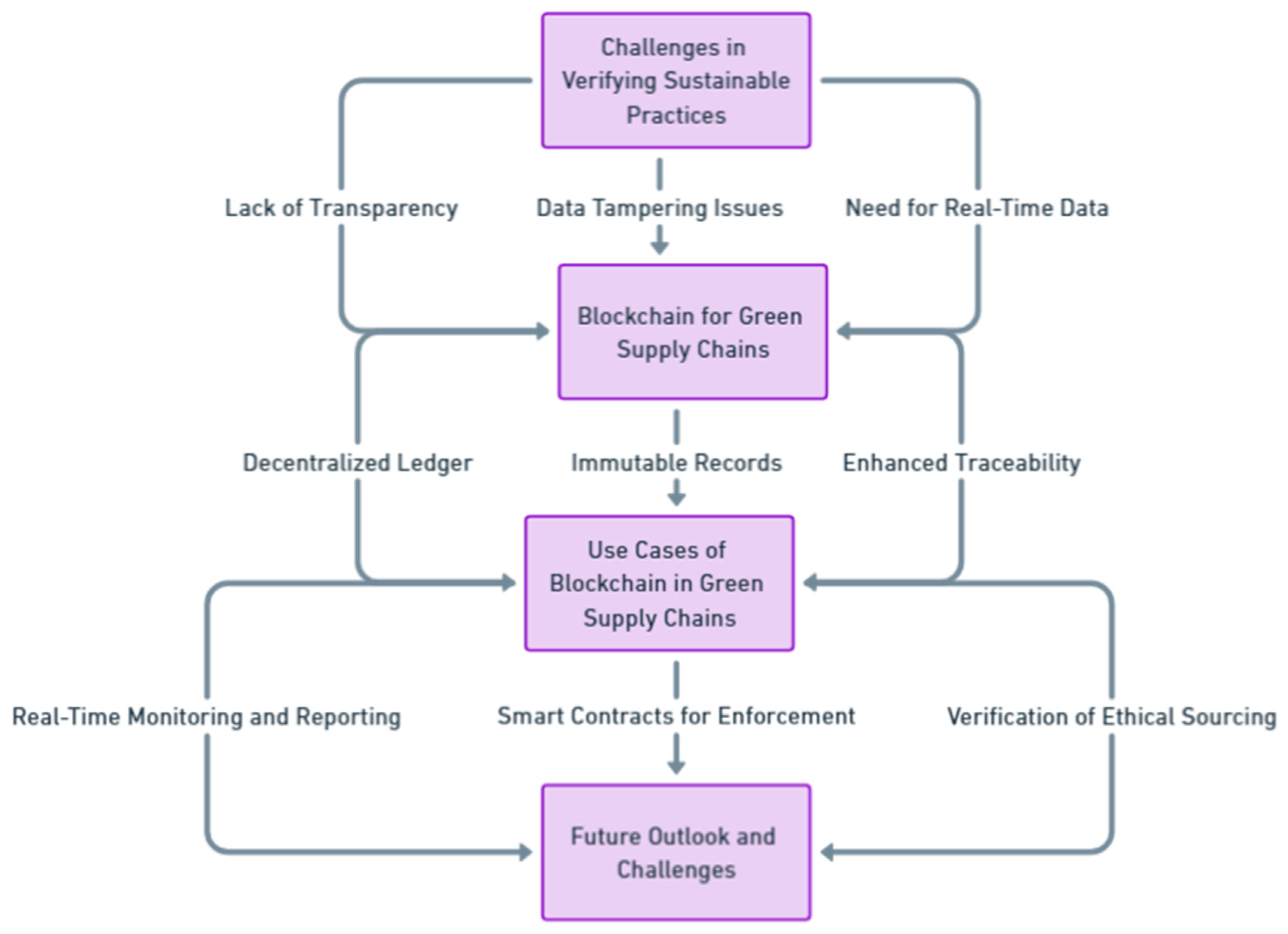

4.5.2. Blockchain for Green Supply Chains: Verifying Sustainable Practices in Logistics Operations

4.5.3. Reducing Fraud in Carbon Offset Programs

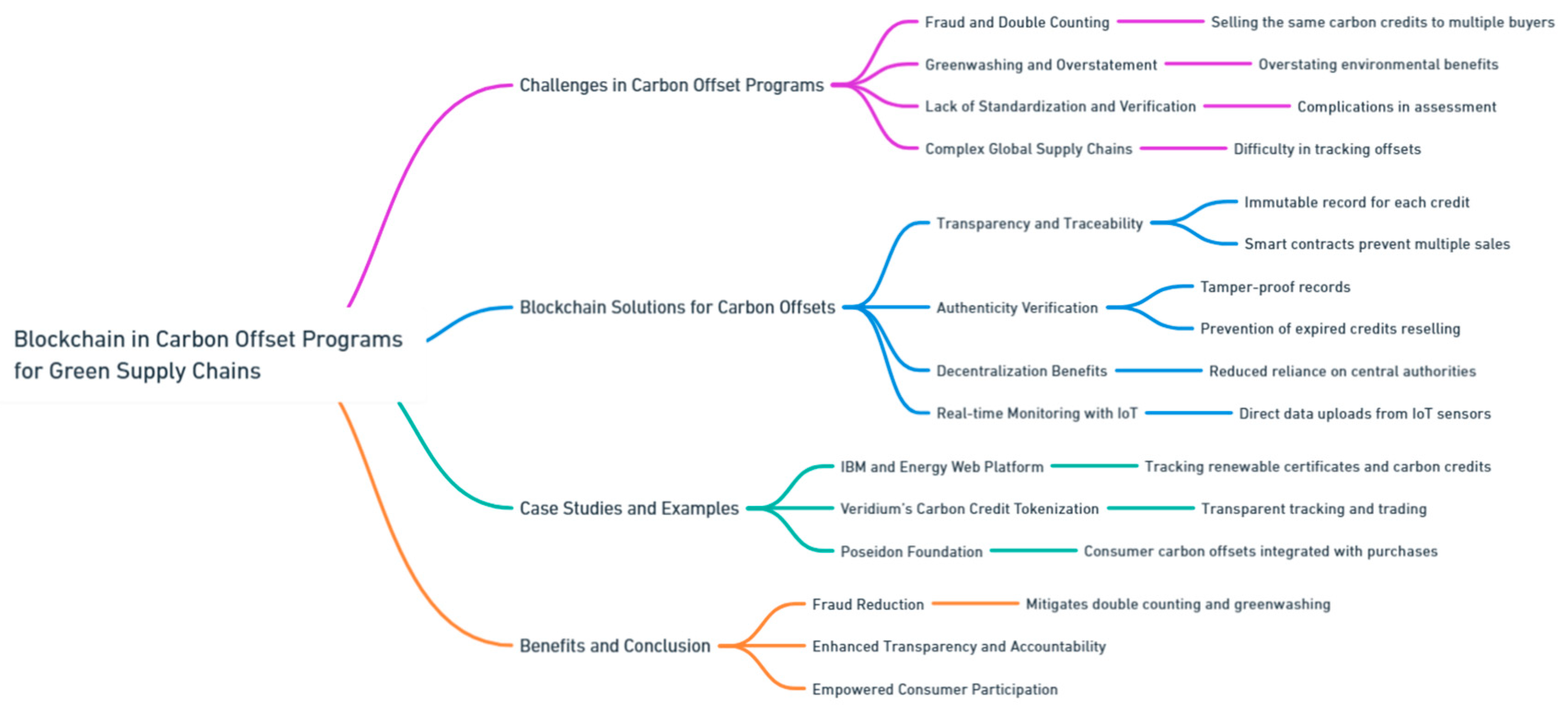

- Transparency and Traceability: Blockchain creates a digital ledger that records every transaction and cannot be altered once it is verified. In the context of carbon offsets, this ensures that each credit is traceable from its origin to its retirement, reducing the risk of fraud. The use of smart contracts can automate verification processes and ensure that carbon credits are only sold once.

- Authenticity: By providing a verifiable, tamper-proof record of emissions reductions, blockchain helps in ensuring that the carbon credits being traded are legitimate. This means companies cannot falsely claim to have reduced their emissions when they haven’t, and it also prevents the reuse or reselling of expired or fraudulent carbon credits.

- Decentralization: Unlike traditional carbon offset systems that rely on central authorities or intermediaries, blockchain operates in a decentralized manner. This eliminates the need for trust in a single organization, as all transactions are verified by the network, reducing the potential for manipulation and corruption.

- Real-time Monitoring: With the integration of Internet of Things (IoT) devices, blockchain can enable real-time monitoring of carbon offset projects. For instance, sensors can measure the amount of carbon being sequestered by a forest restoration project and upload that data directly to the blockchain. This real-time verification improves accuracy and reduces the chances of data manipulation.

4.5.4. Case Study: IBM’s Blockchain Solution for Sustainable Supply Chains

4.5.5. Reducing Carbon Footprint Through Smart Technologies

- -

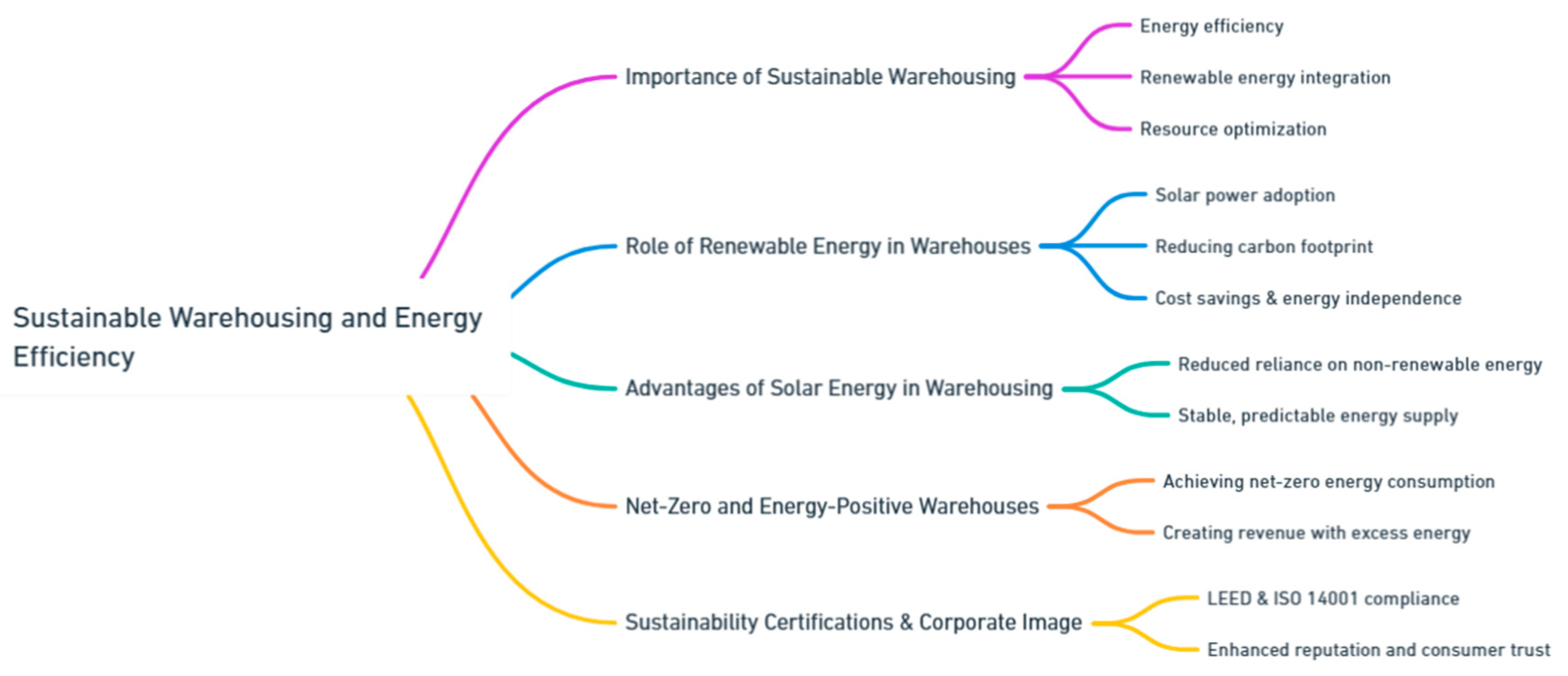

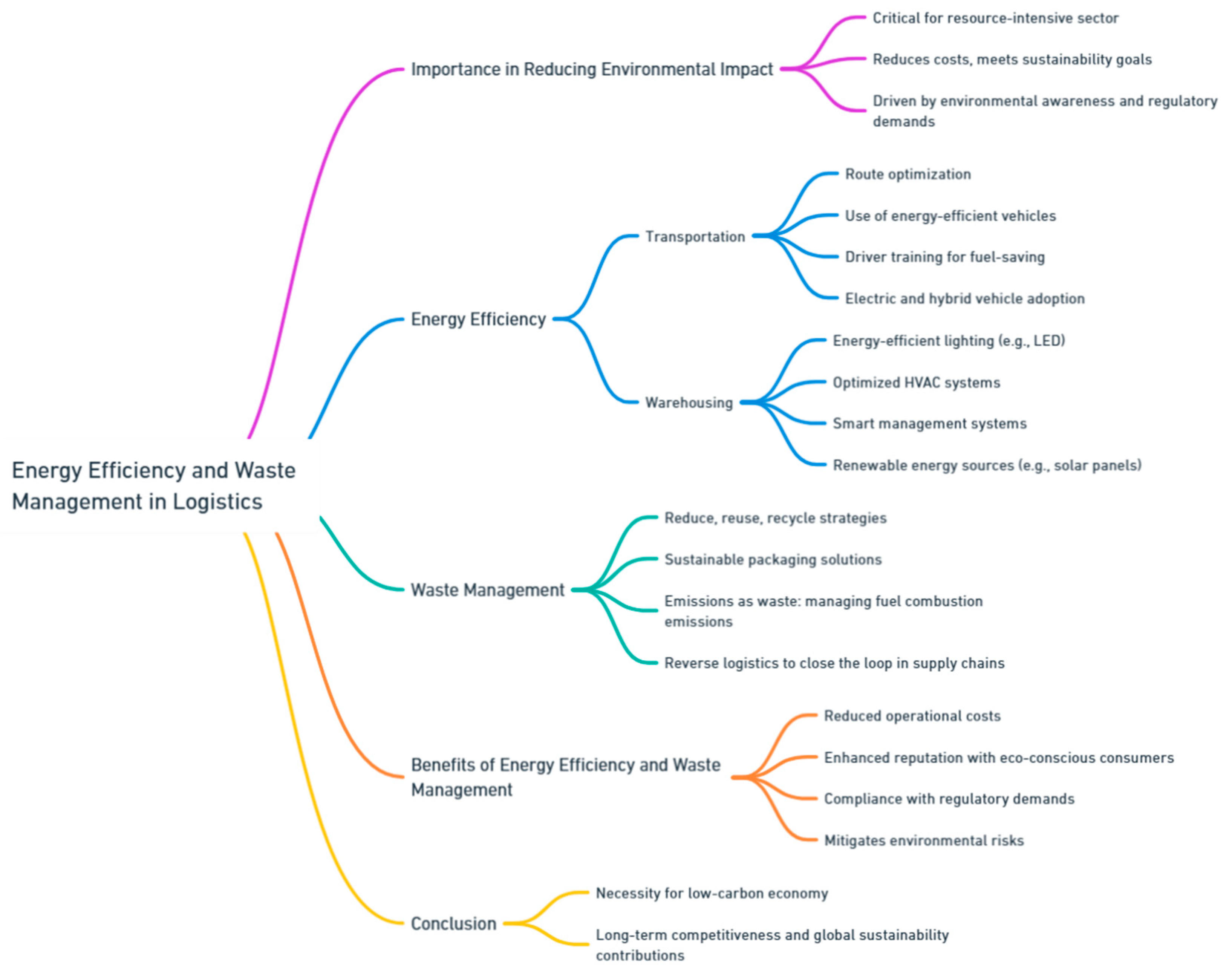

- Energy efficiency: Reducing the energy consumption of warehouses through better design, more efficient equipment, and smarter management systems.

- -

- Renewable energy integration: Shifting from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, and geothermal energy.

- -

- Resource optimization: Minimizing waste, optimizing space usage, and utilizing environmentally friendly materials in construction and operations.

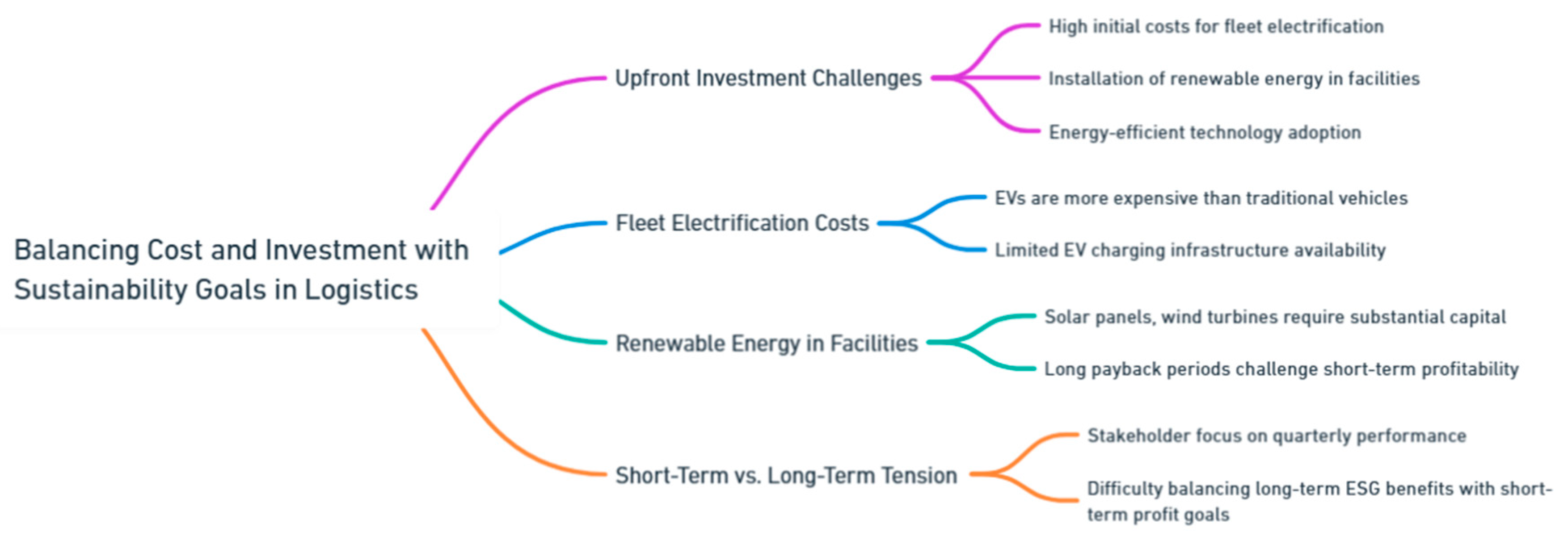

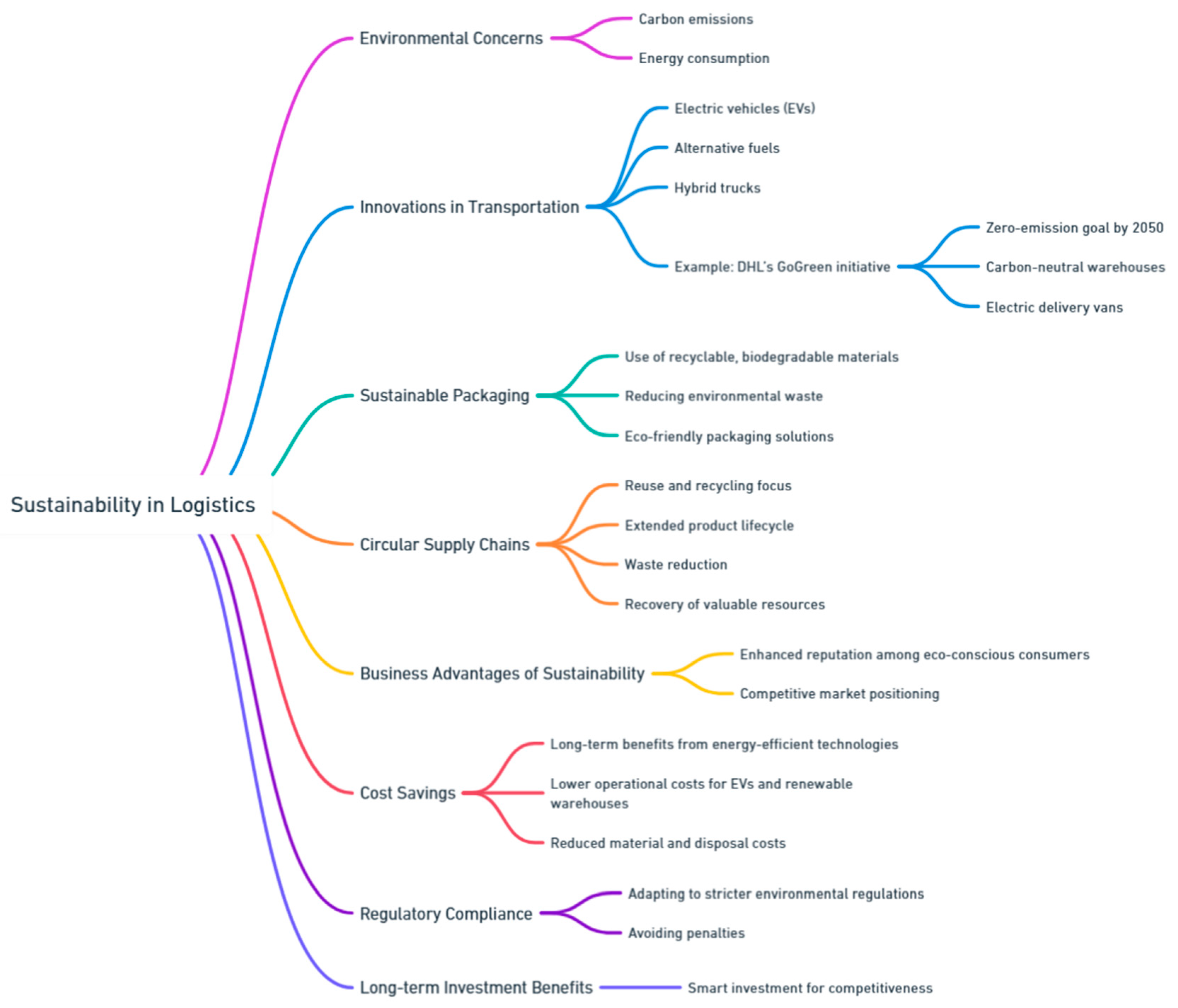

- Reducing Carbon Footprint: The primary reason for using renewable energy in warehouses is to reduce carbon emissions. Traditional warehouses rely heavily on electricity generated from fossil fuels, which produce a large amount of carbon dioxide (CO₂) and other greenhouse gases. By switching to solar power or other renewable sources, warehouses can dramatically reduce their reliance on non-renewable energy and lower their overall carbon footprint. This is especially important in meeting global sustainability goals, such as the reduction of GHG emissions set by international agreements like the Paris Climate Accord. For example, a warehouse equipped with solar panels can significantly reduce its need for grid electricity, which is often generated using coal, natural gas, or oil. As a result, the warehouse’s operations become cleaner and greener, contributing to a more sustainable supply chain ( Lewczuk et al., 2021; Boztepe and Çetin, 2020).

- Cost Savings and Energy Independence: Another critical advantage of using renewable energy, particularly solar power, in warehouses is the potential for cost savings. Solar energy systems can generate electricity on-site, reducing the need to purchase electricity from the grid. Over time, this leads to substantial cost reductions, especially as solar panel technology becomes more affordable and efficient. Although there is an upfront investment required for installing solar panels, the long-term financial benefits often outweigh the initial costs. Additionally, solar energy can help warehouses achieve a degree of energy independence. With solar power systems in place, warehouses are less susceptible to energy price fluctuations and potential shortages, ensuring a more stable and predictable energy supply. In areas where electricity costs are high, solar energy can provide a competitive advantage by lowering operating expenses and improving profit margins (Farthing et al., 2021; Boztepe and Çetin, 2020).

- Net-Zero and Energy-Positive Warehouses: By incorporating renewable energy technologies, warehouses can move closer to achieving net-zero energy consumption. A net-zero warehouse produces as much energy as it consumes over a year, effectively offsetting its energy needs with renewable energy generation. This is a significant step toward sustainability, as it allows warehouses to operate without contributing to the growing demand for non-renewable energy. Some warehouses have even become energy-positive, meaning they generate more energy than they consume. This excess energy can be stored in batteries for later use, sold back to the grid, or used to power other parts of the supply chain. Energy-positive warehouses not only reduce their environmental impact but also create new revenue streams through the sale of surplus electricity (Mavrigiannaki et al., 2021; Wei et al., 2021).