1. Introduction

In recent years, the integration of digital technologies into systems, such as auctioning, has significantly transformed procurement processes, enhancing efficiency but also adding complexity for users like Procurement Officers and Regulatory Officers. However, these technological advancements have also highlighted challenges related to environmental sustainability and fairness, which are foundational to the circular economy framework [

1,

2]. The circular economy, which focuses on minimizing waste and optimizing resource use, deviates from the traditional linear economy model of "take, make, dispose" [

3,

4]. The concept is built upon principles such as maintaining the value of products, materials, and resources for as long as possible, minimizing waste, and regenerating natural systems [

5]. This approach is increasingly essential for sustainable development, particularly in supply chain management, where resource efficiency is paramount [

6,

7].

Despite these advancements, traditional auction systems often fall short in addressing these principles, as they are primarily designed for economic efficiency rather than ecological and social equity [

9,

11]. These systems generally lack the necessary tools to evaluate and optimize economic and environmental performance, leading to inefficiencies and imbalances in resource distribution [

12]. Auctions, by their nature, focus on maximizing financial returns, which can sometimes overlook broader social and environmental impacts [

13]. For instance, transportation activities linked with auctions contribute significantly to CO2 emissions, presenting a substantial environmental challenge [

14,

15]. This makes it difficult for actors like a regulatory officer who needs to understand how different regulatory fees affect the marker and procurement officers who need to define a procurement strategy that plays well with the regulatory settings.

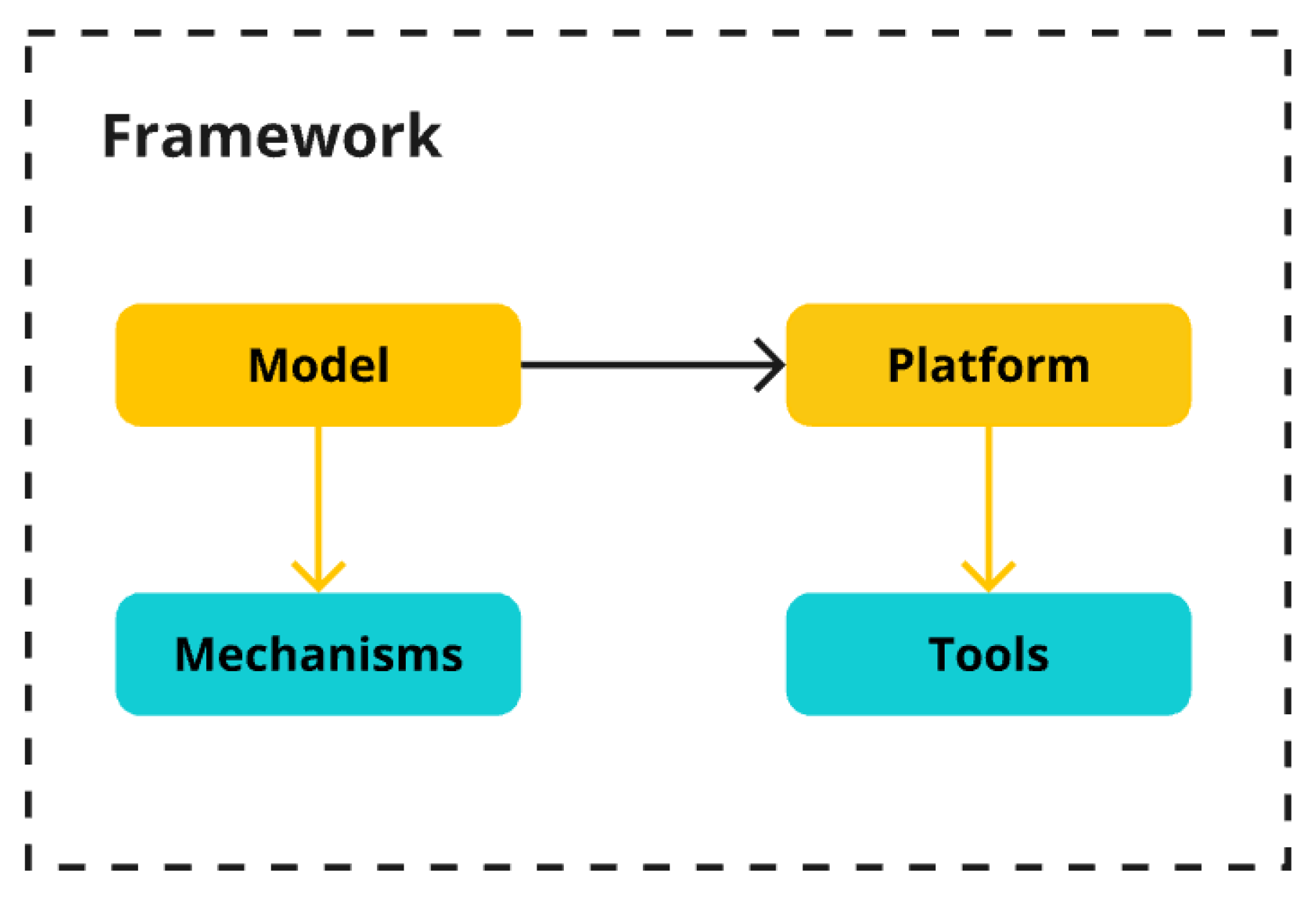

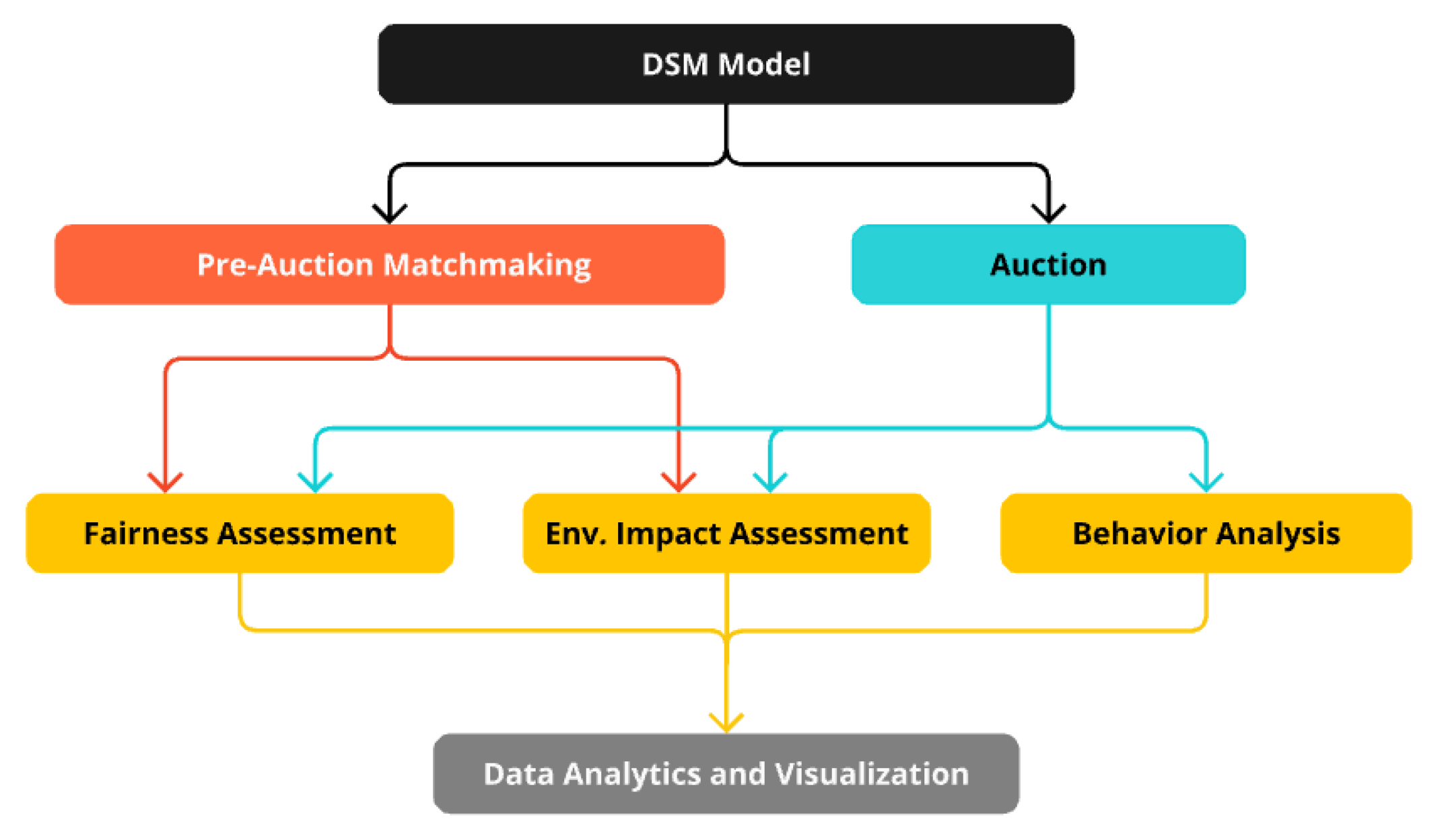

To address these challenges, this paper introduces a novel demand-supply matchmaking (DSM) model implemented within an integrated platform designed to analyze fairness and sustainability in auction environments. The DSM model is part of a broader framework that provides a systematic approach to addressing these challenges. This framework encompasses the platform, model, tools, and mechanisms described throughout this paper. Specifically, the DSM model serves as the conceptual foundation, combining environmental impact assessments, fairness assessments, and bidder behavior analysis into a unified logic for analyzing auction scenarios. The platform that hosts this model acts as the technological environment where these concepts are brought to life, allowing users to simulate auction processes and assess outcomes practically. Within this platform, specific tools are employed to perform key functions, such as calculating environmental impacts, fairness metrics, and simulating bidder behavior dynamics. The operational procedures or algorithms, referred to as mechanisms within the model, guide how the model’s logic is applied during the platform functions. Each tool within the platform may consist of multiple components that work together to achieve specific functionalities.

Figure 1.

General diagram of the DSM framework

Figure 1.

General diagram of the DSM framework

The DSM model operates within this integrated framework, aligning with the principles of the circular economy to enhance resource allocation and reduce environmental impacts, such as CO2 emissions associated with transportation. By simulating bidder behavior and incorporating fairness metrics and environmental considerations, the model provides a comprehensive analysis of auction scenarios. Traditional systems often lack the ability to address such complex, multi-faceted challenges effectively [

16,

17].

The DSM model addresses several key challenges: ensuring equitable resource distribution, reducing environmental impacts, and understanding the strategic behavior of bidders. Traditional auctions often result in uneven outcomes where certain participants consistently benefit over others, leading to issues of inequality [

18]. By assessing fairness, our DSM model aims to promote more equitable outcomes among auction participants, ensuring that benefits are shared fairly and transparently [

19]. Additionally, the model incorporates environmental assessments to evaluate and minimize emissions and waste, aligning with global sustainability goals [

20,

22]. Understanding bidder behavior dynamics is crucial, as strategic bidding often influences auction outcomes significantly. The DSM model provides insights into these dynamics, allowing for an analysis of how different strategies impact fairness and sustainability, thereby promoting auctions that are both economically efficient and socially responsible [

23].

The research focuses on developing a DSM model that integrates various components into a comprehensive framework. This framework includes the platform, which hosts the DSM model and provides the technological environment for simulating auction processes and assessing outcomes. The objectives of this research include demonstrating the model’s effectiveness through simulations, highlighting its potential to transform auction practices, and addressing existing challenges in supply chain management by promoting equitable resource distribution and reducing environmental footprints [

6,

19].

The contributions of this paper can be categorized into three primary areas:

Problem Analysis and Challenges (Section 3 and Section 4): By addressing shortcomings in existing auction systems, particularly those related to fairness, environmental impact, and behavioral dynamics, this paper establishes the necessity for a model that integrates these crucial aspects into the auction process. This analysis identifies where traditional approaches fall short in achieving equitable and sustainable outcomes to fulfill current supply chain and circular economy needs.

Design and Implementation (Section 5): To address these challenges, the DSM model is designed and implemented within an integrated platform. The model incorporates detailed environmental impact assessments, fairness assessments, and behavioral analytics. These mechanisms are organized into tools that are part of a cohesive and balanced auction framework capable of addressing the identified shortcomings. Mechanisms within the model guide how these tools and components interact and operate within the platform.

Evaluation and Results (Section 6): We demonstrate the DSM model’s practical applicability through its capacity to integrate fairness, environmental impact, and decision-making processes in auctions. This evaluation highlights the model’s ability to transform traditional auction systems into more sustainable and equitable models that are fully aligned with the principles of the circular economy.

The results provide detailed evidence of the DSM model’s capacity to increase fairness and a reduction in CO2 emissions compared to existing auction methods, showcasing the model’s potential to transform auction practices [

14,

20]. These results indicate that the DSM model can serve as a powerful tool for enhancing both the economic and environmental aspects of auctions, providing tangible benefits for procurement and regulatory officers, as well as other stakeholders. Particularly, understanding how stakeholder engagement shapes these dynamics can reveal new pathways for fostering sustainability culture in organizations [

10].

This paper begins with a literature review that establishes the context for the proposed DSM model by identifying the limitations of current auction systems in terms of fairness and environmental concerns. The review is followed by an exploration of existing tools and technologies, leading to the design and implementation of the DSM model. The subsequent sections evaluate the model’s effectiveness through simulations, followed by a discussion on the implications of the findings and potential directions for future research. Finally, the paper concludes with a summary of the key contributions and insights.

By presenting a new approach to auction systems, this research aims to set a new standard for integrating environmental sustainability and fairness into digital marketplaces, ultimately contributing to more responsible and efficient supply chain management and circular economy practices [

6,

23].

2. Methodology

2.1. Problem Analysis

To identify the key limitations of traditional auction systems, we conducted a comprehensive problem analysis focusing on three critical areas: fairness, environmental impact, and bidder behavior. This analysis involved reviewing existing literature and empirical studies on auction practices, particularly those impacting supply chain management and circular economy initiatives. For example, we examined the environmental effects of transportation activities associated with auctions, noting substantial contributions to CO2 emissions [

14]. Additionally, we reviewed studies highlighting fairness issues, such as unequal resource distribution due to information asymmetry, which disadvantages less-informed bidders. This background informed our selection of fairness and sustainability as primary objectives for the DSM model.

2.2. Review of Existing Tools

In this phase, we analyzed current auction platforms to understand their functionalities and limitations. We reviewed tools commonly used for economic efficiency in auction systems and evaluated how they address or fail to address sustainability and fairness. For instance, we assessed platforms primarily focused on maximizing financial returns and identified challenges where environmental impact assessments or fairness metrics were lacking. By comparing these tools, we established the need for an integrated model that includes environmental and social metrics, offering a more balanced approach to resource allocation within auction systems. This review confirmed the challenges our DSM model aims to fill, positioning it as a comprehensive alternative to existing tools.

2.3. Design of the DSM Model

Based on insights from the problem analysis and existing tools review, we structured the DSM model to integrate fairness, environmental sustainability, and bidder behavior analysis. During the design phase, we focused on creating an adaptable architecture that could evaluate and balance these objectives in auction scenarios. For example, the model was designed with modular components, each addressing a specific metric: fairness indices (e.g., Jain’s Fairness Index), environmental assessments (CO2 emissions calculations), and bidder behavior simulations.

Each mechanism was designed to function both independently and in conjunction, allowing flexibility in auction setups. We included scenarios that procurement officers and regulatory officers would likely encounter, such as balancing cost with environmental impact in resource allocation. This structured design laid the foundation for the platform’s technical implementation, ensuring each component could be seamlessly integrated.

2.4. Development of the DSM Model

Building on the findings from the problem analysis and tool review, we developed the DSM model, focusing on three core components: fairness metrics, environmental impact metrics, and bidder behavior dynamics. For the fairness component, we integrated Jain’s Fairness Index and Percentage to measure equitable outcomes, ensuring fair distribution of resources among participants. For environmental impact, we designed mechanisms to assess CO2 emissions and waste associated with logistics and transportation, which aligns with circular economy principles. In terms of bidder behavior, we developed a tool to analyze different bidding strategies and their effects on auction outcomes. This design process involved testing various configurations to balance these components without compromising efficiency, as seen in traditional auction systems.

2.5. Platform Implementation

We implemented the DSM model within a digital platform, transforming it into a practical tool for auction-based procurement. This involved creating algorithms and workflows for each component of the model, fairness, environmental impact, and behavior analysis, allowing real-time simulations. For instance, the platform was coded to simulate bidder behavior and calculate fairness metrics dynamically as bids are placed. We employed data-driven methods, such as pre-auction evaluations and environmental assessments, to enrich the decision-making process for procurement and regulatory officers. By consolidating these functions, the platform offers a seamless interface where users can analyze auction outcomes in terms of both sustainability and fairness.

2.6. Evaluation Approach

To validate the DSM model’s effectiveness, we conducted a series of simulations representing various auction scenarios, each designed to test the model’s capacity for balancing fairness, environmental impact, and cost-effectiveness. For example, we ran simulations comparing aggressive bidding strategies with balanced approaches to evaluate their effects on fairness and sustainability scores. These tests measured the DSM model’s performance across multiple metrics, such as CO2 emission reductions and fairness indices, relative to traditional auction systems. By using real-world data on resource distribution and environmental impact, we demonstrated the DSM model’s potential for transforming auction practices in ways that align with both circular economy principles and sustainable supply chain management.

3. Problem Analysis

Demand-supply matchmaking is complex at a large scale. Regulatory Officers need transparent insights into procurement activities to ensure compliance with fairness and environmental standards, focusing on transparency and accountability to meet ethical and sustainable guidelines.

Procurement Officers face the challenge of balancing competitive bidding with sustainable choices. They must evaluate suppliers responsibly while managing costs. Both roles must consider how different settings and strategies affect fairness, environmental impact, and equitable outcomes, highlighting the intricate challenges of integrating these metrics into large-scale auction processes.

3.1. Fairness in Auction Systems

Fairness in auctions refers to the equitable treatment of all participants, ensuring that everyone has an equal opportunity to succeed based on merit rather than advantage or bias. This includes transparency, accessibility, and impartiality throughout the bidding process, which is especially relevant for Regulatory Officers and Procurement Officers working to maintain fair practices.

Traditional auction systems often face criticism for creating unfair outcomes, where participants with more information or resources can gain an advantage, leading to unequal results. This issue is particularly common in sectors like real estate and online marketplaces, where access to information can heavily influence bidding strategies and outcomes [

24]. For regulatory officers, such biases challenge efforts to ensure compliance with fairness standards, while procurement officers must navigate these biases to make responsible supplier choices.

Recent studies highlight that information asymmetry and strategic manipulation are persistent issues in auction systems, limiting opportunities for some participants and reducing the perceived integrity of auction systems [

24,

25]. The reliance on complex algorithms and digital platforms can increase these imbalances, as noted by Bichler et al. (2022), who emphasize the need for auction platforms to incorporate mechanisms that promote transparency and fairness [

26]. This focus on fairness is essential for both regulatory and procurement officers to make informed, equitable decisions in auction environments.

3.2. Environmental Impact

Environmental impact in trade practices is a critical challenge, often overlooked in the pursuit of economic efficiency [

1]. Large-scale procurement processes, especially those involving significant logistics, contribute substantially to environmental degradation through resource consumption, waste generation, and greenhouse gas emissions [

20]. For Regulatory Officers, monitoring these impacts is essential to ensure that procurement aligns with sustainability goals and regulatory standards. Procurement Officers are also directly affected, as they must consider these environmental factors when selecting suppliers and making purchasing decisions [

21].

The logistics and transportation activities associated with procurement are primary contributors to greenhouse gas emissions, often conflicting with the sustainability principles that support the circular economy [

18]. A recent study by Bocken et al. (2023) underscores the urgency of integrating environmental metrics into auction and procurement platforms, emphasizing that sustainable trade practices can significantly reduce ecological footprints [

27]. This integration is critical for both regulatory compliance and strategic procurement, as it enables these officers to align trade practices with global sustainability targets. Kauffman et al. (2021) further advocate for eco-friendly auction designs that minimize environmental impact, highlighting the importance of sustainable metrics for both regulatory and procurement strategies [

28].

3.3. Behavioral Dynamics

Understanding bidder behavior dynamics is essential for predicting auction outcomes and ensuring market efficiency. Bidder’s behavioral pattern is influenced by various factors, including competition, risk tolerance, and information access. These dynamics can lead to strategic manipulation and inefficiencies, complicating the auction process for both Regulatory Officers and Procurement Officers. Regulatory officers must monitor such behavior to prevent unfair advantages, while procurement officers need insights into bidder strategies to make balanced and informed decisions.

Research by Cong et al. (2020) demonstrates that strategic bidding often results in outcomes favoring more aggressive or well-informed bidders, which can undermine fairness [

29]. Liu et al. (2022) further explore how behavioral analytics can enhance auction design by providing insights into bidder strategies, promoting outcomes that are both predictable and equitable [

30]. This understanding is crucial for developing auction systems that support economic efficiency while upholding social responsibility.

3.4. Challenges in Supply Chain Management

Current auction systems often create inefficiencies in resource allocation within supply chains, leading to bottlenecks and increased costs. These inefficiencies stem partly from the lack of integration between auction platforms and supply chain management systems, resulting in misaligned procurement, distribution, and inventory strategies [

22]. For Procurement Officers, this misalignment complicates sourcing and resource planning, as they aim to streamline procurement processes to meet demand efficiently. Regulatory Officers also face challenges, as inefficient systems can lead to resource waste and excess environmental impact, making it difficult to ensure compliance with sustainability standards.

Antikainen et al. (2023) emphasize that these inefficiencies are a significant barrier to sustainable supply chain management, highlighting the need for systems that support better resource distribution and reduce waste [

32]. Wilson et al. (2021) further discuss the importance of integrating auction systems with supply chain management to optimize logistics and inventory decisions, enhancing overall efficiency and aligning with sustainable procurement goals [

33].

3.5. Circular Economy Challenges

The transition to a circular economy requires auction systems to prioritize sustainability, emphasizing recycling, reuse, and sustainable sourcing. Unfortunately, many auction systems do not align with these principles, contributing to increased waste and resource depletion [

7]. This misalignment poses challenges for both Regulatory Officers, who aim to enforce standards that minimize environmental impact, and Procurement Officers, who seek suppliers that support circular practices through sustainable product lifecycle management [

8].

Stahel (2016) highlights the systemic changes needed in auction models to align with circular economy goals, emphasizing the importance of considering lifecycle impacts in auction design [

7]. Recent studies by Kirchherr et al. (2023) further advocate for integrating circular economy principles into auction platforms, arguing that such integration is essential for fostering sustainable practices and reducing environmental footprints across industries [

34].

3.6. Interconnections Between Auctions, Supply Chains, and Circular Economy

The limitations of current auction systems create cascading effects across supply chains and circular economy initiatives. Inefficient auctions can lead to delays, increased waste, and environmental harm, ultimately undermining sustainable resource management goals [

5]. For Regulatory Officers, these inefficiencies complicate efforts to ensure compliance with environmental standards, while Procurement Officers face challenges in achieving streamlined and sustainable procurement.

Integrating circular economy principles into auction systems could enhance supply chain efficiency and sustainability. For example, designing auctions that prioritize resource circularity can promote sustainable outcomes, as suggested by Perera et al. (2021) and Bocken et al. (2023), who highlight the transformative potential of sustainable auction practices for achieving circular economy goals [

25,

27].

4. Existing Tools

In the current landscape of auction systems and supply chain management, various tools and platforms have been developed to increase efficiency, fairness, and sustainability. This section reviews these existing solutions, evaluates their capabilities, and identifies challenges that the proposed DSM model aims to address.

4.1. Auction Platforms

Auction platforms serve as digital marketplaces where goods and services are bought and sold through bidding processes. These platforms vary widely in their approach to handling fairness, transparency, and environmental considerations.

4.1.1. Traditional Online Auctions

eBay is one of the most prominent online auction platforms, known for its wide accessibility and user-friendly interface. It supports a broad range of products, from consumer goods to specialized items, catering to millions of users worldwide. eBay operates on a dynamic pricing model where the highest bidder wins, offering flexibility and variety in purchasing options. The platform’s accessibility and product variety make it a versatile marketplace, popular among users for its ease of use and comprehensive offerings. While eBay standardizes access to auctions, it does not adequately address fairness strategies by informed bidders or incorporate sustainable practices into its auction framework [

35].

Limitations and challenges:

Fairness Concerns: Information asymmetry and strategic bidding can lead to unfair advantages, where bidders with more information or faster internet connections can employ the system to their advantage. This creates an unequal outcome for less-informed participants.

Environmental Impact: The platform does not explicitly account for the environmental costs associated with product logistics and transportation, leading to increased emissions and resource use that are not managed or minimized within the platform’s operations.

4.1.2. Auctions and Marketplace

Amazon’s auction-style listings are integrated into its broader marketplace operations, providing users with the option to bid on or buy items directly. The platform is seamlessly connected to Amazon’s extensive logistics and supply chain infrastructure, ensuring an efficient transition from auction to delivery. Amazon’s strong brand reputation and exceptional customer service further enhance user confidence, making it a reliable and trusted platform for online auctions. However, Amazon’s all-inclusive approach is hindered by limited emphasis on impartial practices and sustainability, resulting in opportunities to improve fairness and reduce environmental impacts [

36].

Limitations and challenges:

Transparency Issues: Some practices related to seller ratings and product authenticity can affect fairness, as the platform sometimes favors established sellers over new ones, leading to biased auction outcomes.

Sustainability challenges: There is a limited focus on reducing the environmental impact of auctions, such as emissions from logistics and packaging waste. Amazon’s focus on speed and efficiency often overlooks the environmental costs associated with its extensive logistics network.

4.1.3. Open-Source Auction Platforms

Open-source auction platforms provide flexible and customizable solutions that can be adapted to specific needs and integrated into broader systems.

Auctioneer and

FairAuction are two open-source platforms designed to enhance digital auctions. Auctioneer offers extensive customization, supporting various auction types like English and Dutch auctions, making it adaptable to diverse needs [

37]. FairAuction focuses on ensuring fairness and transparency in the auction process with tools that promote equitable practices [

38]. Both platforms benefit from strong community engagement and allow for tailored solutions for users seeking flexibility. However, they require technical expertise, making them less accessible for non-experts.

Limitations and challenges:

4.2. Environmental Sustainability Tools

With growing awareness of environmental issues, several tools have emerged to assess and mitigate the environmental impacts of auction and supply chain activities.

4.2.1. CO2 Calculation Tools for Logistics

These tools, such as

DHL’s Carbon Calculator and

EcoTransIT World, are designed to assess the carbon footprint of transportation activities within supply chains. These tools offer detailed insights into emissions across various modes of transport, allowing businesses to understand and manage their carbon footprint effectively. Additionally, they provide actionable recommendations for reducing carbon emissions, helping companies develop more sustainable logistics strategies. While useful for logistics, these tools do not address the environmental impact of auction processes, missing opportunities to integrate sustainability into the broader auction framework [

39].

Limitations and challenges:

Limited Integration: Often operate as independent tools without direct integration into auction platforms, which limits their ability to provide a broad view of sustainability across the entire auction process.

Specificity: These tools are primarily designed for logistics and may not account for other environmental impacts, such as those from manufacturing or end-of-life disposal.

4.2.2. Open-Source Environmental Sustainability Tools

OpenLCA is an open-source tool focused on assessing and mitigating the environmental impacts of logistics activities, particularly designed for life cycle assessment (LCA). This tool is highly flexible and adaptable to different logistics scenarios. It also benefits from being open-source, which allows for extensive customization and community-driven improvements. While OpenLCA provides a flexible and open-source approach to sustainability, it may require significant integration efforts to be effectively used alongside existing auction systems [

40].

Limitations and challenges:

4.3. Fairness Tools

4.3.1. Open-Source Fairness Indicators and Algorithms

These tools, such as

Fairlearn toolkit, are designed to measure and enhance fairness in various contexts, including auctions. While these tools provide quantifiable metrics to assess fairness objectively and can be adapted to different auction models, they are not inherently integrated into auction systems, which might require additional customization or integration efforts. Also, their complexity and data dependency limit their applicability and effectiveness in diverse auction environments [

41].

Limitations and challenges:

Complexity: Requires extensive data and computational resources to implement effectively, which can be a barrier for smaller organizations or those without significant technical expertise.

Data Dependency: The effectiveness of these tools depends on the availability and quality of data, which may not always be accessible or reliable.

4.3.2. Open-Source AI Fairness Tools

Aequitas and

AI Fairness 360 are open-source tools designed to measure and evaluate the fairness of machine learning models. It provides a range of fairness metrics that can be applied to assess whether a system treats participants equitably, focusing on issues like disparate impact and bias. Its comprehensive metrics provide valuable insights into equity and transparency, making it a great component for platforms aiming to create fair and unbiased environments. However, its direct application in auction systems may require customization or additional integration, increasing its complexity, and the data dependency can limit its applicability, especially for organizations lacking the necessary technical expertise [

42,

43].

Limitations and challenges:

Complex Implementation: Requires substantial data and expertise to deploy effectively.

Integration Needs: May require additional work to integrate with existing auction platforms, potentially requiring technical expertise and resources.

4.4. Behavioral Analytics

4.4.1. Behavioral Analytics Platforms

These tools, such as

Google Analytics and

Mixpanel, provide insights into user behavior that can be applied to understand bidder strategies in auctions. These platforms offer data-driven insights through real-time analysis of user interactions, helping auctioneers identify bidding patterns and strategies. They are also scalable and capable of handling large datasets across various platforms, making them suitable for extensive auctions. These platforms offer valuable insights but are limited by privacy concerns and a lack of attentiveness to auction contexts, highlighting the need for more targeted behavioral analytics tools in auctions [

44].

Limitations and challenges:

Privacy Concerns: Handling user data requires careful management to protect privacy, which can be challenging given the increasing focus on data protection and user rights.

Focus: These platforms are primarily designed for general analytics and may not be tailored specifically for auction environments, leading to challenges in understanding bidder behavior nuances.

4.4.2. Open-Source Behavioral Analytics

Matomo and

Open Web Analytics (OWA) are an open-source tool that focuses on analyzing user interactions, offering a flexible, community-driven approach to understanding user interactions on digital platforms. It provides real-time analysis, helping auctioneers understand bidding patterns and strategies, and benefits from continuous development through community engagement. However, privacy concerns and integration complexities limit its broad applicability [

45,

46].

Limitations and challenges:

Privacy Concerns: Handling user data requires careful management to protect privacy, especially given the increasing focus on data protection. Complexity of Integration: Integration into existing auction platforms may require significant customization and expertise to align analytics with auction-specific metrics.

4.5. Tools Incorporating Multiple Aspects

4.5.1. EnHelix Auction Software

EnHelix Auction Software is a commercial platform that integrates blockchain technology to increase auction process transparency, security, and efficiency. It is designed primarily for energy and commodities markets, offering tools for environmental impact assessment and compliance with sustainability standards. However, its industry-specific focus and potential implementation complexity may limit broader applicability. [

47].

Limitations and challenges:

Industry Limitation: Primarily designed for energy and commodities markets, which may limit its applicability to other auction settings or industries.

Cost: As a commercial solution, it may be costly for smaller enterprises or those with limited budgets.

4.5.2. SAP Ariba

SAP Ariba is a powerful platform for organizations seeking to integrate sustainability, risk management, and efficient procurement practices. Its comprehensive features support global supply chain operations, making it suitable for large enterprises with complex needs. It provides solutions that can be adapted for auction processes, making it a versatile tool for organizations seeking to increase their procurement strategies. However, its complexity and focus on procurement rather than auctions may necessitate customization and training [

48].

Limitations and challenges:

Cost Considerations: As a high-end commercial solution, it may be expensive for smaller businesses or those with limited procurement needs.

Limited Auction-Specific Features: While adaptable for auction processes, the platform primarily focuses on procurement and supply chain management, which may require customization for specific auction requirements.

4.6. Shortcomings of Existing Tools

The analysis of current tools, as summarized in

Table 1 and

Table 2, reveals some important challenges that limit their adoption and usefulness in auction systems. This section highlights these shortcomings and explains their impact.

4.6.1. Lack of Broad Integration

One of the most notable shortcomings of the existing tools is their specialization in one area, such as fairness, environmental impact, or behavioral analytics, but they fail to provide a broad approach, as shown in

Table 2. For example, tools like Aequitas focus on fairness but don’t consider environmental impact or user behavior. Similarly, tools for calculating carbon emissions, like DHL’s Carbon Calculator, are great for logistics but don’t integrate well with auction platforms. This approach misses the chance to create a system that can assess the full environmental impact and fairness of auctions.

4.6.2. High Complexity and Technical Challenges

Many of these tools reviewed, especially open-source ones like Auctioneer and FairAuction, require a significant technical skill to set up and use, as indicated in

Table 1. This can be a big challenge for smaller organizations or those without dedicated technical teams. This complexity limits the accessibility and broader adoption of these tools, particularly for users seeking straightforward solutions. Additionally, tools that analyze fairness or user behavior often need large amounts of data and powerful computing resources, which aren’t always available. This makes it harder for many users to effectively use these tools.

4.6.3. Not Specifically Designed for Auction Requirements

Some tools, like Google Analytics and Mixpanel, are designed for general data analysis, not specifically for auctions, as shown in

Table 2. This means they might not fully understand or address the unique aspects of bidding behavior in auctions and may need significant customization to be effectively used in auction contexts, which can be resource-demanding, as highlighted in

Table 1. Similarly, popular auction platforms like eBay and Amazon Auctions do not focus enough on ensuring fairness or reducing environmental impact, which are crucial for creating ethical and sustainable auctions.

4.6.4. Cost and Limited Industrial Applicability

Commercial tools like EnHelix Auction Software and SAP Ariba, while offering comprehensive features, are often costly, making them less accessible to smaller enterprises. Additionally, these tools are usually designed for specific industries, like energy or large-scale procurement, which makes them less flexible and harder to adapt to other types of auctions. As noted in

Table 1, these industry-specific tools may not easily adapt to different auction settings without significant customization, further increasing the cost and complexity of their implementation.

4.6.5. Conclusions

The shortcomings identified in the existing tools highlight the need for more integrated, accessible, and auction-specific solutions that can address fairness, environmental impact, and behavioral analytics comprehensively. Future development in auction technology should focus on creating tools that are easy to deploy, adaptable across industries, and capable of addressing the full spectrum of ethical and sustainability concerns in auction processes.

5. Design and Implementation

5.1. Design of the Platform

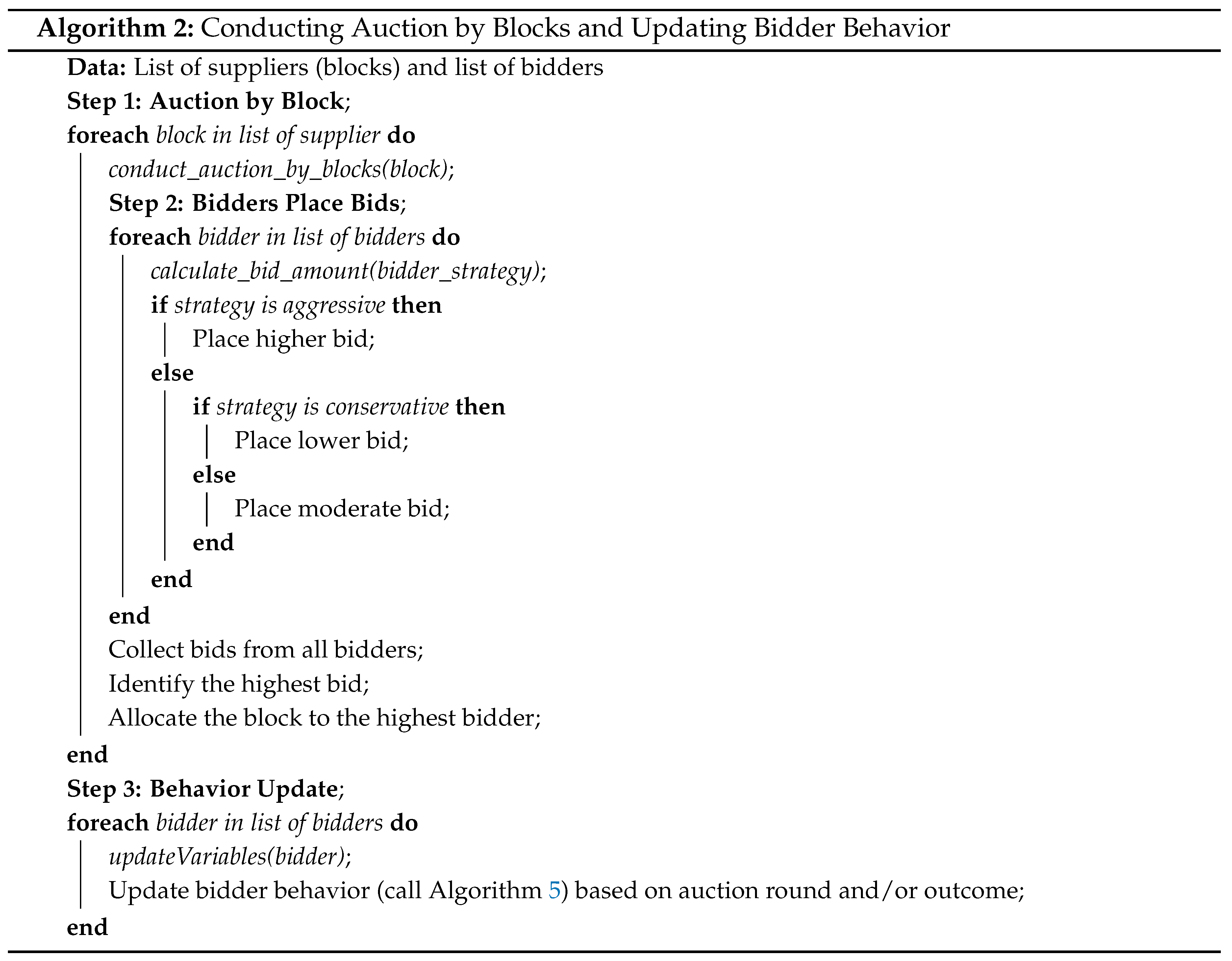

The platform is designed based on the DSM model to address key challenges in auction systems, specifically focusing on fairness, environmental sustainability, and bidder behavior analysis. These challenges are essential for Procurement Officers, who require efficient and equitable resource allocation to support responsible purchasing, and for Regulatory Officers, who oversee compliance with sustainability and fairness standards. The model integrates several mechanisms to provide a complete framework that evaluates and optimizes auction strategies, as shown in

Figure 2 [

49].

5.1.1. Pre-Auction Matchmaking of Demanders and Sellers

Before the auction process begins, the Model is designed to evaluate the potential combinations between demanders (bidders) and sellers (blocks). This process optimizes strategies for each bidder and suggests scenarios where direct purchases may be more beneficial than auctioning. This process is detailed in the papers [

50,

51], which provide a comprehensive explanation of the pre-auction part of the model evaluation methodology.

Key Points:

Optimal Combinations: Evaluates the best matches between demanders and sellers.

Direct Purchase Opportunities: Identifies scenarios where direct purchases may be more advantageous than auctioning.

Strategic Decision-Making: Provides bidders with insights into optimal strategies before the auction process.

5.1.2. Auction Simulation Process

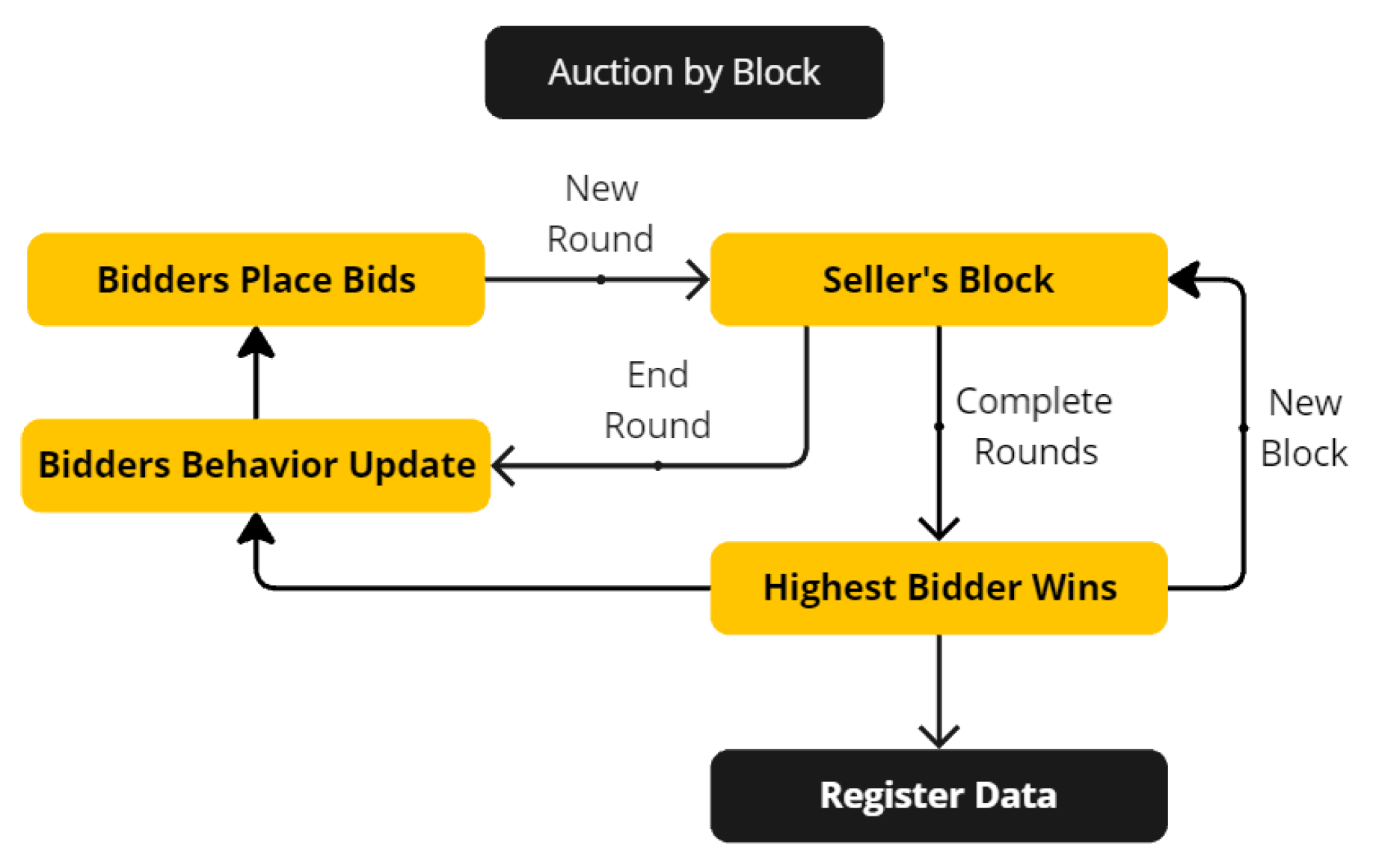

The Model employs the "auction by block" mechanism in this implementation and evaluation. This mechanism auctions each seller’s block sequentially, ensuring efficient and fair resource allocation. This method allows bidders to compete for each block individually, promoting transparent and equitable outcomes.

Key Points:

Sequential Bidding: Blocks are auctioned one at a time until all blocks are sold.

Fairness Mechanisms: Various fairness Mechanisms are used to evaluate the equity of auction outcomes.

Dynamic Behavior: Behavior adjusts based on demand and bidder competition.

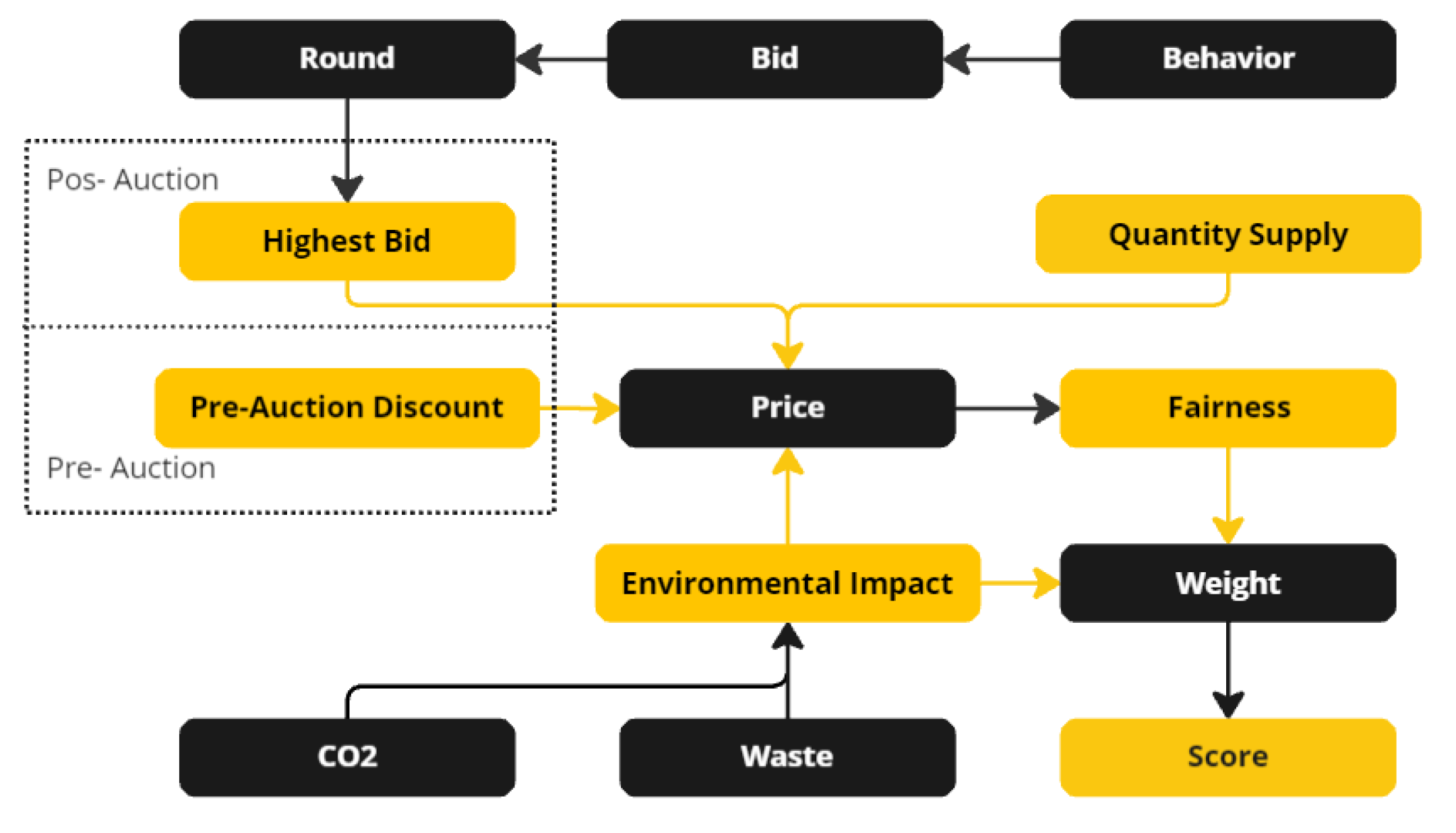

5.1.3. Fairness Assessment

The fairness assessment is crucial for ensuring equitable outcomes among bidders. To ensure equitable outcomes, the model incorporates a few fairness Mechanisms, including Jain’s Fairness Index, a well-known measure of fairness in resource allocation [

52]. These Mechanisms are used to evaluate and promote fairness throughout the auction process.

Key Points:

Equity Evaluation: Uses fairness mechanisms to assess the equity of auction outcomes.

Bias Detection: Identifies and mitigates biases in the pre-auction and auction process.

Transparent Reporting: Provides transparent metrics and reports on fairness.

5.1.4. Environmental Impact Assessment

The environmental impact assessment aims to evaluate and minimize the ecological footprint. This involves mechanisms for carbon emissions and other environmental costs related to logistics, such as transportation and waste. Specifically, waste calculates the difference between the quantity of goods a bidder needs and the quantity they actually receive after the auction. This difference, or excess, is considered waste, which contributes to the environmental footprint of the auction. The model integrates these assessments to promote sustainable practices and align with global sustainability initiatives.

Key Points:

5.1.5. Behavioral Analysis of Bidders

Behavioral analytics of bidders is essential for creating realistic auction simulations. By modeling different types of bidder behaviors (e.g., aggressive, conservative, balanced), the platform can better predict and analyze auction outcomes. Defining the behavior templates and their respective strategies allows the simulation to account for diverse bidder actions.

Key Points:

Behavior Templates: The behavior templates define the various bidder behaviors, such as aggressive, conservative, and strategic. These templates help simulate different bidder actions and responses during the auction process.

Dynamic Adjustments: The model allows bidders to dynamically adjust their strategies based on the outcomes of previous auction rounds. This dynamic adjustment ensures that bidder behavior remains realistic and adaptable to changing auction conditions.

Strategic Decision-Making: Bidders employ different strategies to maximize their success. In the case of this tool, we calculate the unfulfilled needs of the bidder to change their strategy.

Types of Bidders: The DSM model uses three primary types of bidders: aggressive, conservative, and balanced. Each type of bidder has distinct behaviors and strategies.

Type A or Aggressive Bidder: These bidders are characterized by high aggressiveness and market price factors. They are willing to place higher bids and take greater risks to win the auction. Their bid likelihood is generally high, and they are less likely to stop bidding even as prices rise.

Type B or Balanced Bidders: Strategic bidders balance aggressiveness and conservatism. They adjust their bids based on market trends and unfulfilled needs, aiming to make well-informed decisions. Their bid likelihood is balanced, and they stop bidding within a reasonable range to avoid excessive spending.

Type C or Conservative Bidders: Conservative bidders have lower aggressiveness and market price factors. They are more cautious and place lower bids, aiming to avoid overpaying. Their bid likelihood is moderate, and they are more likely to stop bidding when prices approach their predefined limits.

Other Types: In this evaluation, we also have types D, E, and F. Each of them is similar to the ones addressed before. For example, type D is almost equal to type A. The only change is their aggressiveness parameter, fixed to a value of 0.5, the same as the others, type E with Type B and Type F with Type C. The purpose is to give all bidders in an auction of different behavior types the same starting line when referring to aggressiveness to bid and see if that affects the results in the higher bid price.

Behavior Parameters: The behavior of each bidder type is governed by several key parameters, which determine how they interact with the auction process.

Aggressiveness: This parameter determines how "aggressive" a bidder’s bids are. It effectively scales the bid size. Higher values mean more aggressive bidding, which could result in higher bids and increased risk of overpaying.

Market Price Factor: This factor represents the percentage of the market price (price per unit) the bidder is willing to bid. It allows bidders to adjust their bids relative to the market price, making their strategy more flexible and market-aware.

Stop Bid: This parameter defines the expected price range at which the bidder will stop bidding. It helps prevent overbidding by setting a threshold beyond which the bidder will not go, ensuring that the bids remain within a reasonable range.

Bid Likelihood: This parameter indicates the likelihood of a bidder placing a bid. It introduces an element of randomness and uncertainty, simulating real-world scenarios where bidders may choose not to bid in certain situations.

5.1.6. Data Analytics and Visualization

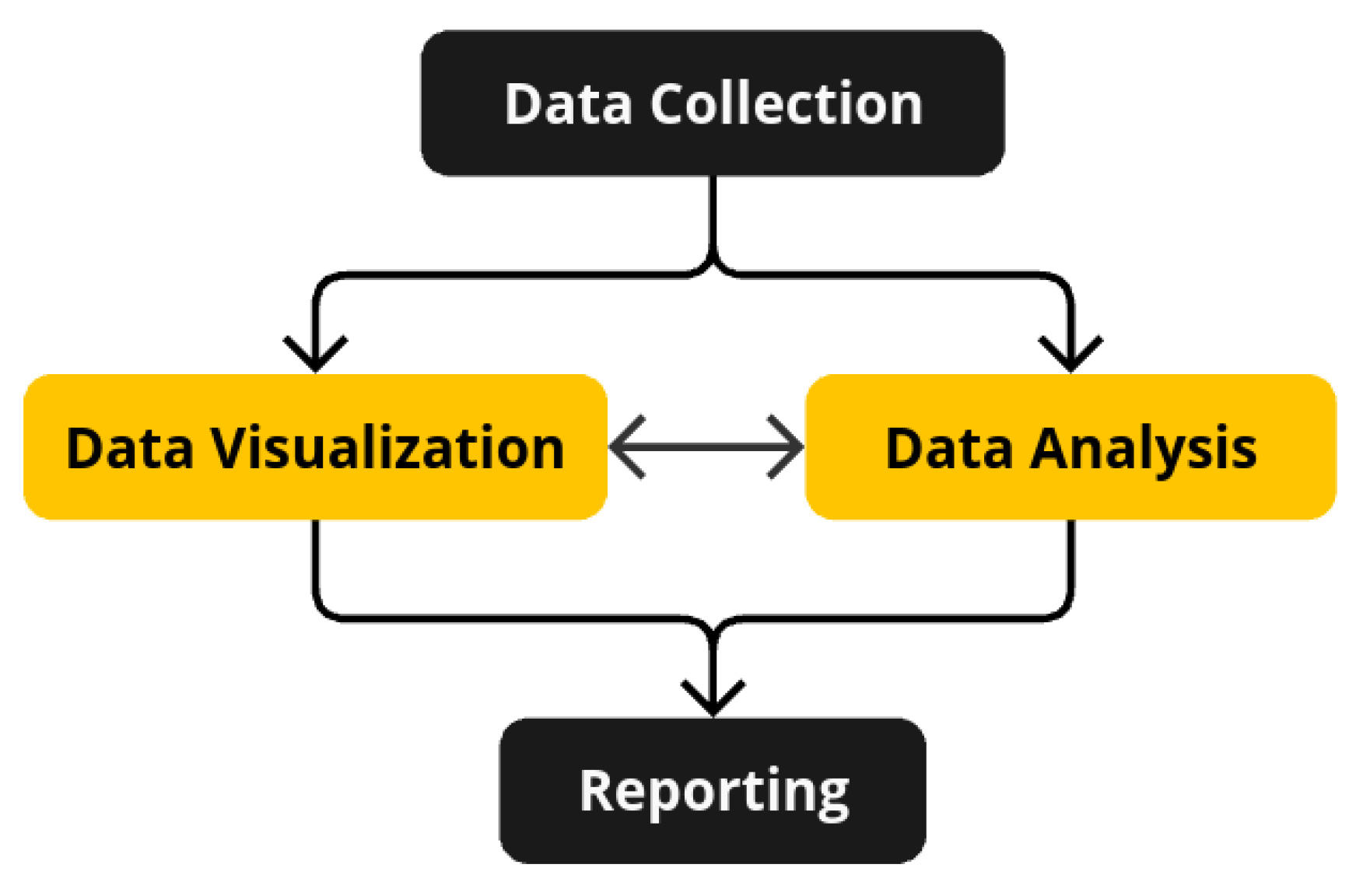

Data analytics and visualization are crucial mechanisms of auction systems, providing stakeholders with valuable insights derived from auction data. These mechanisms enable the interpretation of complex data sets, helping to make informed decisions and optimize auction strategies. When analyzed and visualized effectively, the files generate data revealing patterns, trends, and actionable insights.

Key Points:

Data Collection: The platform collects data from various pre-auction and auction activities, including bids, bidder behavior, environmental impact metrics, and fairness metrics. This data is stored for further analysis,

Figure 3.

Data Visualization: The analyzed data is then visualized; in this case, we export data to an Excel file to make the insights easily interpretable.

Data Analysis: Once collected, the data is analyzed using statistical methods to uncover patterns and trends. This analysis helps understand bidder behavior, auction outcomes, and the impact of different strategies.

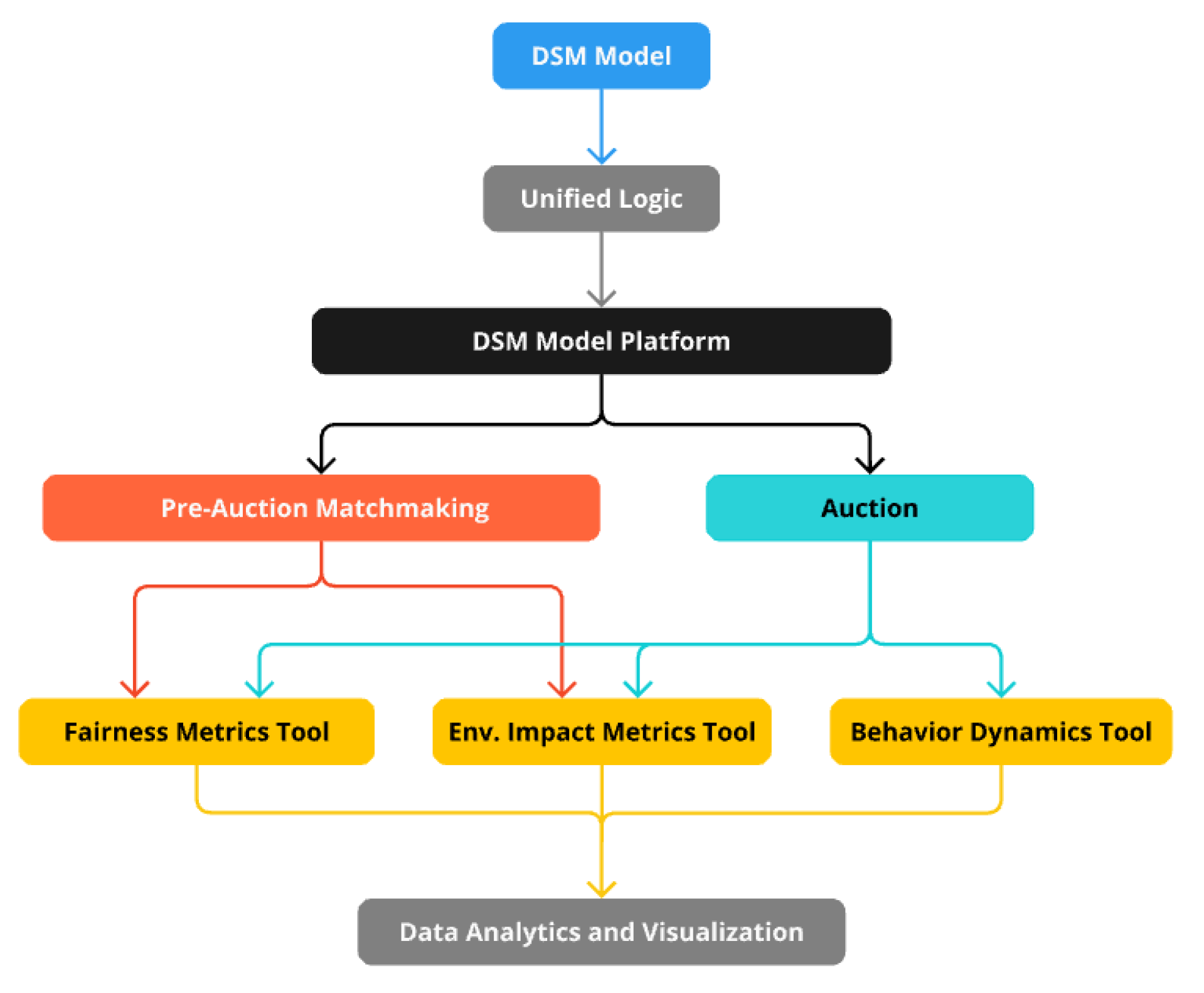

5.2. Implementation Details

The platform unifies the DSM model’s logic by implementing a combination of tools and data-driven methods to address the challenges identified in the design phase. This section details the technical workflows developed to ensure platform functionality, emphasizing features critical for Regulatory Officers and Procurement Officers, such as pre-auction matchmaking, auction simulation processes, fairness metrics, environmental impact metrics, and behavioral dynamics, as shown in

Figure 4. These workflows support compliance, transparency, and strategic decision-making in sustainable procurement.

5.2.1. Pre-Auction Matchmaking

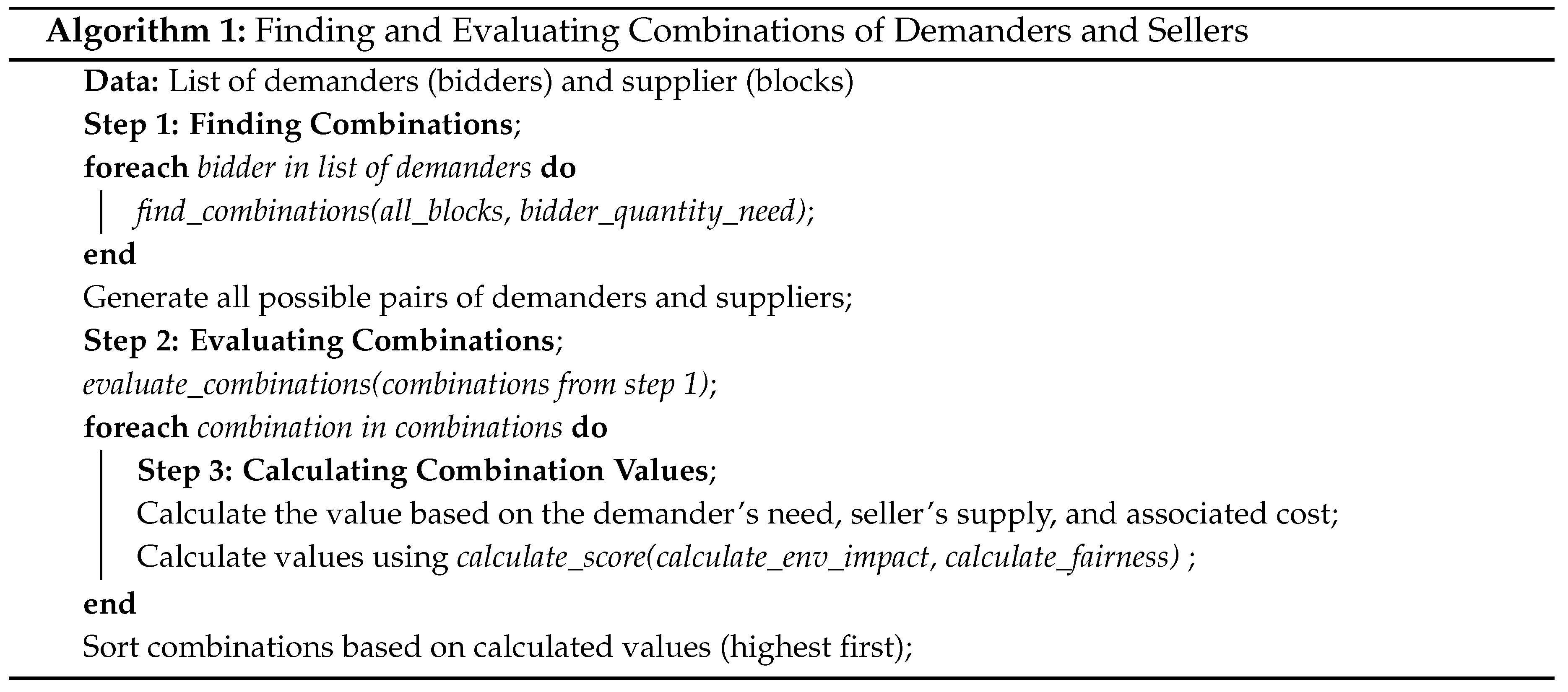

The pre-auction matchmaking process is important for optimizing the auction outcomes by evaluating potential combinations of demanders (bidders) and sellers (blocks). This process was implemented using the following key functions, as shown in

Figure 5:

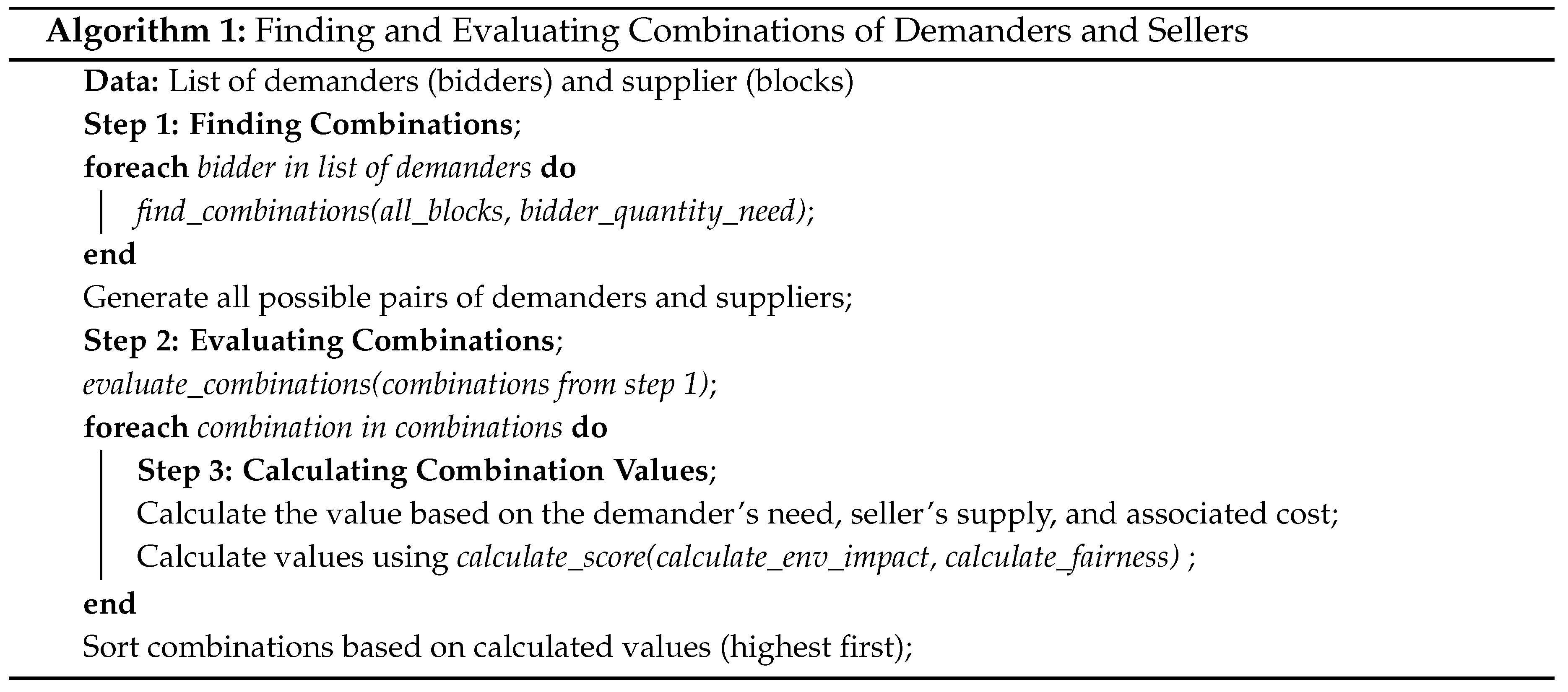

The pre-auction matchmaking (Algorithm 1) aims to match demanders (bidders) with suppliers (blocks) by first generating all possible combinations of demander-supplier pairs. In Step 1, the find_combinations() function ensures that every bidder is paired with all available suppliers to explore all potential matches. Next, in Step 2, the evaluate_combinations() function assesses each combination by calculating its value, which involves considering the demander’s need, the seller’s supply, and associated costs. Additionally, the value calculation incorporates metrics like environmental impact (calculate_env_impact) and fairness (calculate_fairness). Finally, these combinations are sorted to prioritize those with the highest value, ensuring the most beneficial pairs are selected. This approach helps balance economic efficiency with sustainability and fairness in the matching process.

Figure 5.

Pre-Auction Demand-Seller Matchmaking Evaluation Workflow.

Figure 5.

Pre-Auction Demand-Seller Matchmaking Evaluation Workflow.

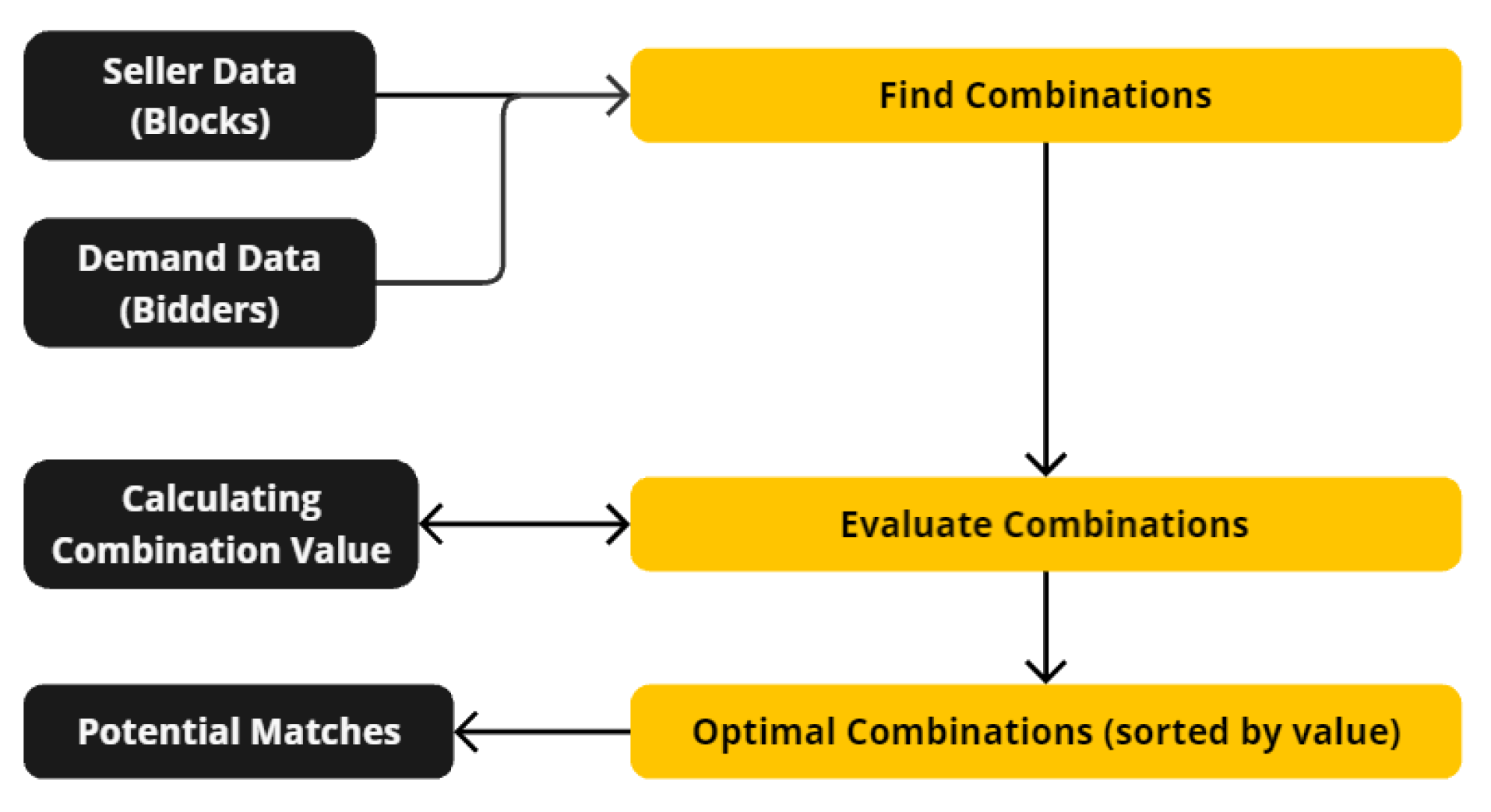

5.2.2. Auction Simulation Process

The auction process was designed to allocate resources efficiently and fairly. The platform uses an "auction by block" strategy, which was implemented through the following functions, as shown in

Figure 6:

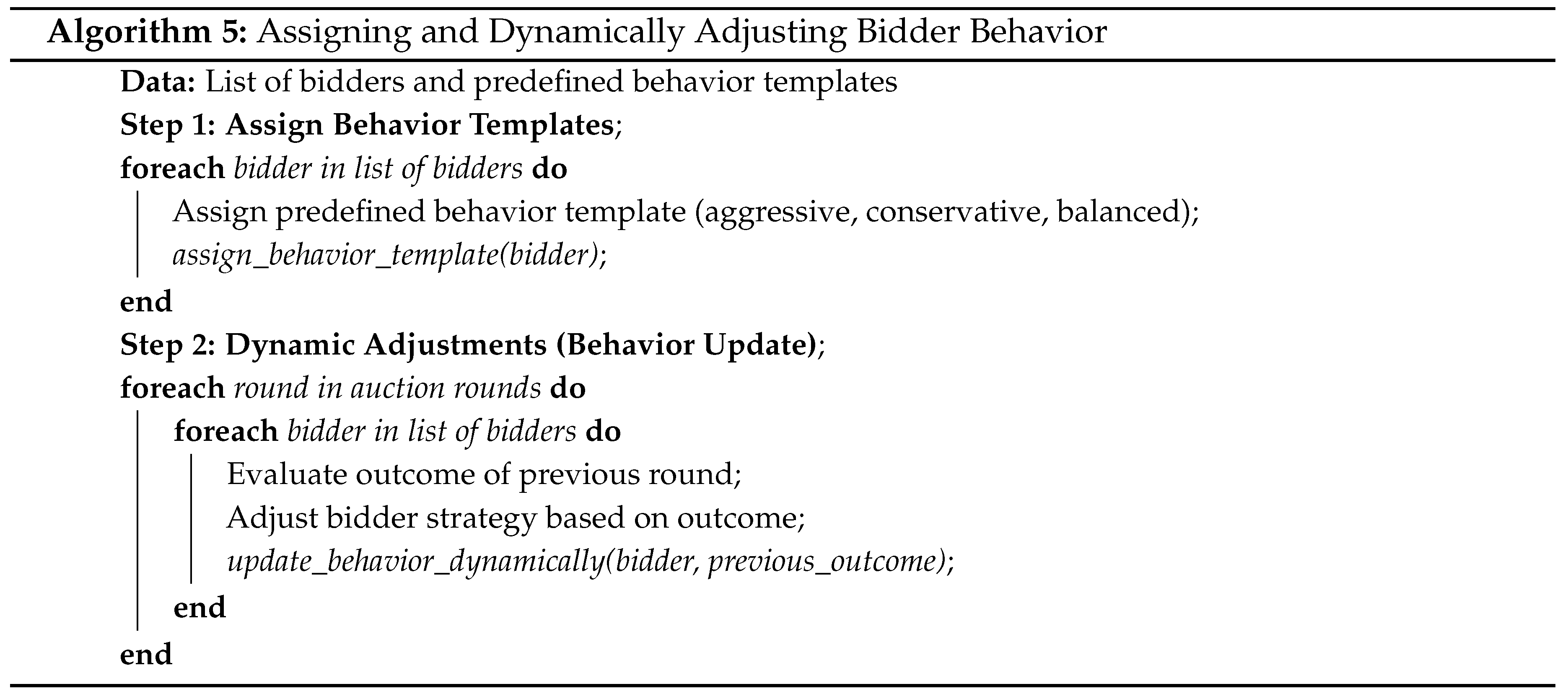

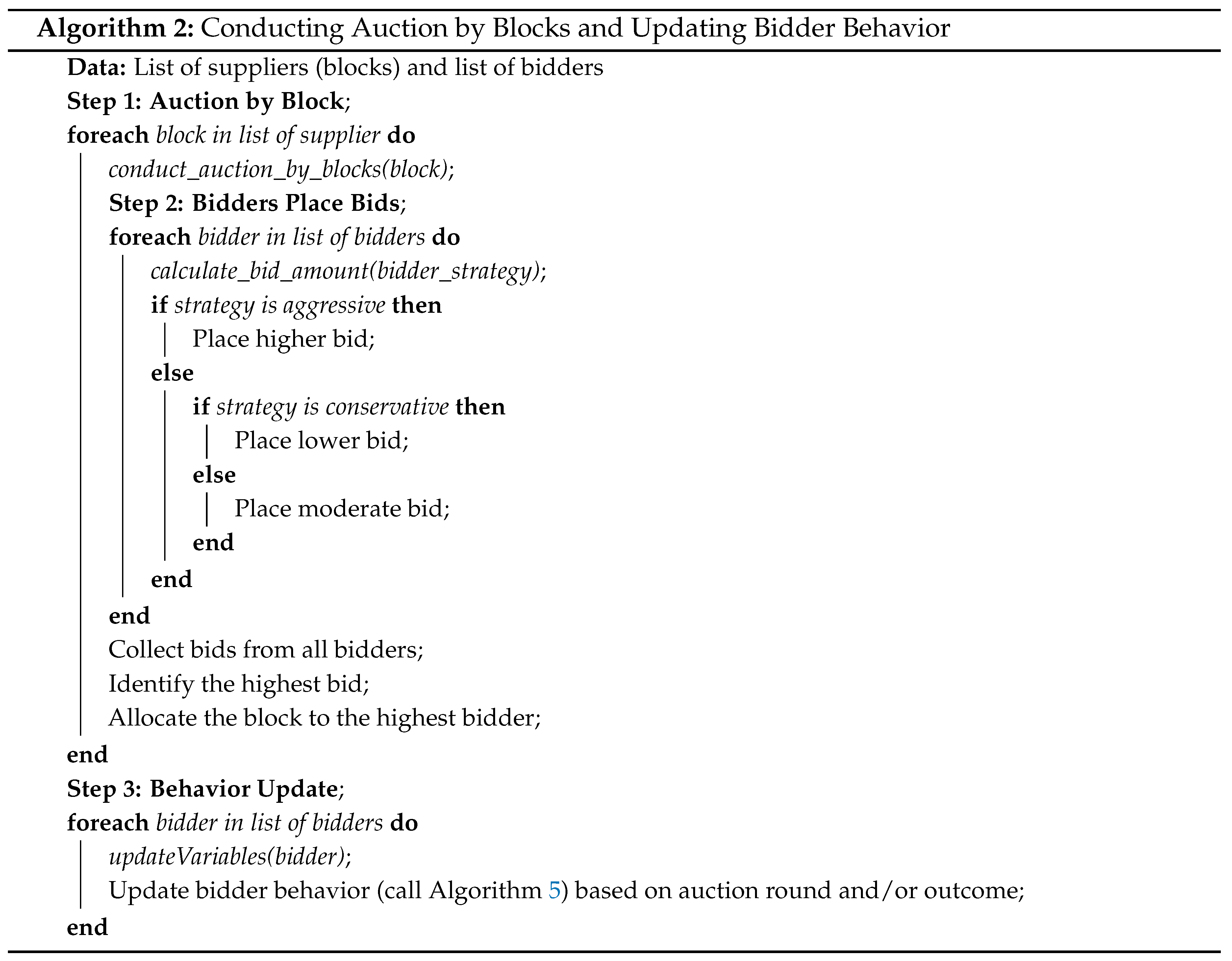

The auction process (Algorithm 2) is conducted for each supplier’s block, ensuring an optimal allocation. In Step 1, the conduct_auction_by_blocks() function handles the auction for each block in turn. During Step 2, each bidder places their bids based on their individual strategy—aggressive, conservative, or moderate—using the calculate_bid_amount() function. The bidding process considers different levels of risk and commitment, where aggressive strategies involve higher bids and conservative ones involve lower bids. Once all bids are collected, the highest bid is identified, and the block is allocated to the highest bidder. Finally, in Step 3, the updateVariables() function updates each bidder’s behavior based on the auction round and/or outcome, allowing them to adapt their future strategies dynamically. To accomplish this, the algorithm of the behavior dynamics tool (Algorithm 5) is called to assign behavior templates and allow dynamic adjustments.

Figure 6.

Auction Mechanism By Block Workflow.

Figure 6.

Auction Mechanism By Block Workflow.

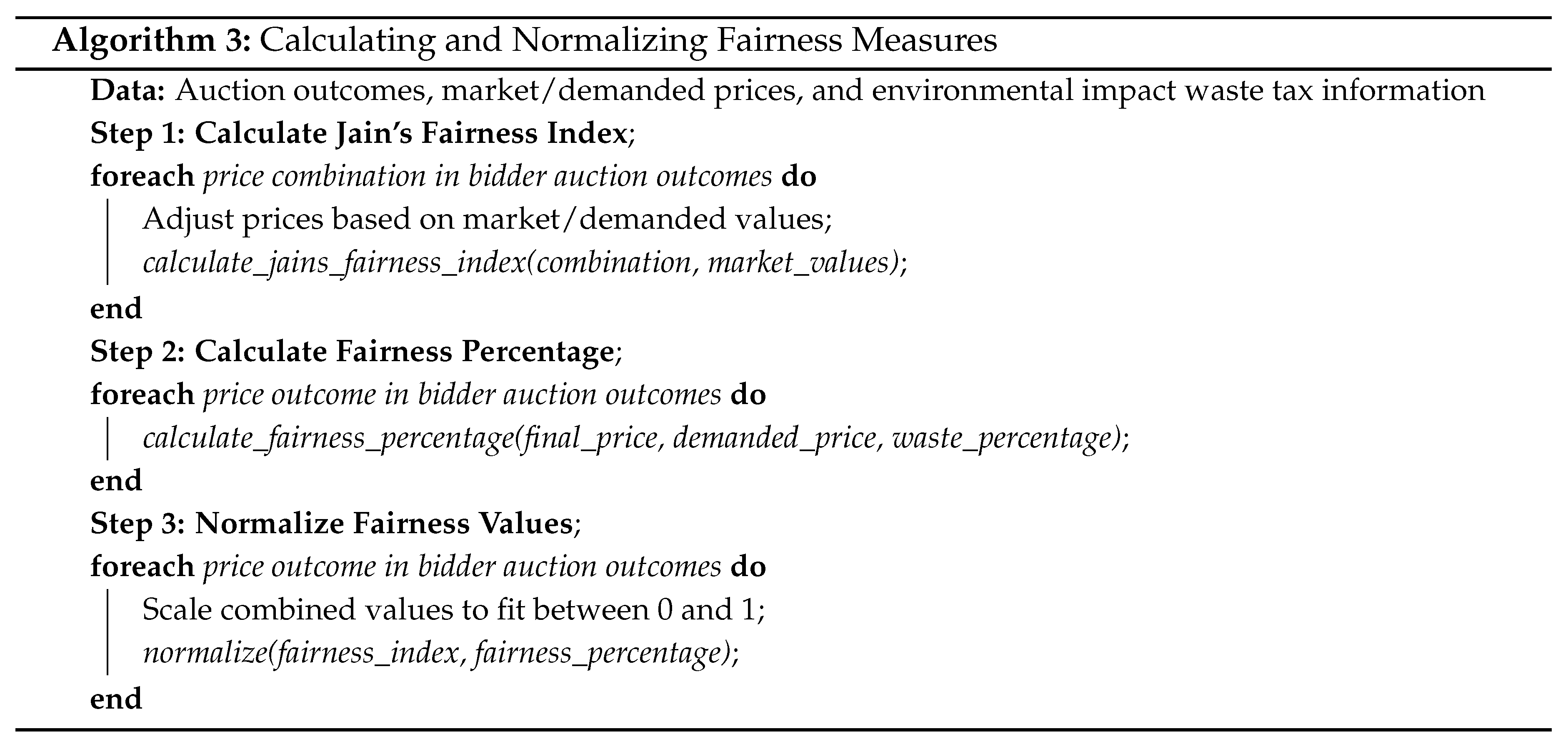

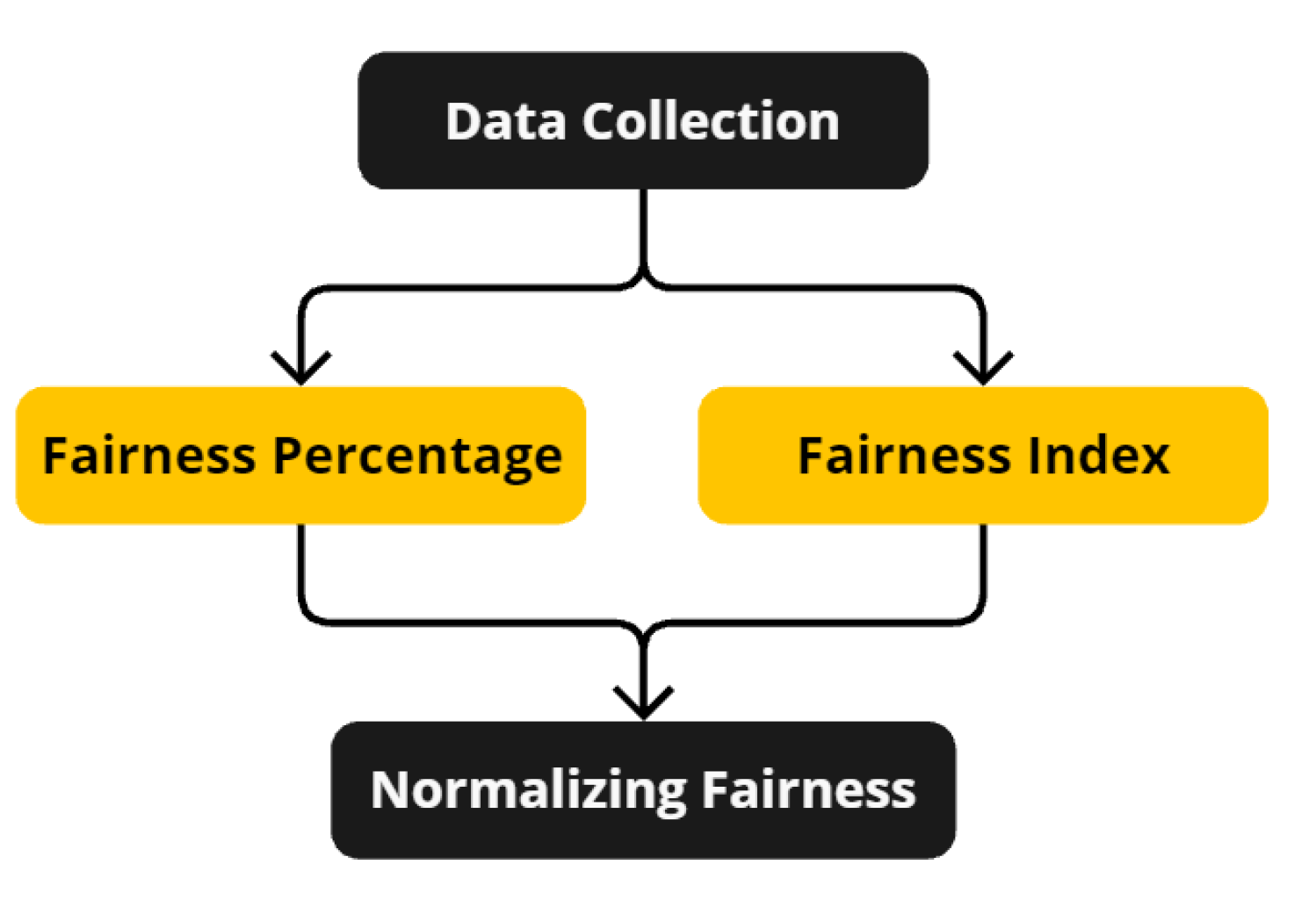

5.2.3. Fairness Metrics Tool

To ensure equitable outcomes, the platform includes a fairness metrics tool that was implemented as follows, as shown in

Figure 7:

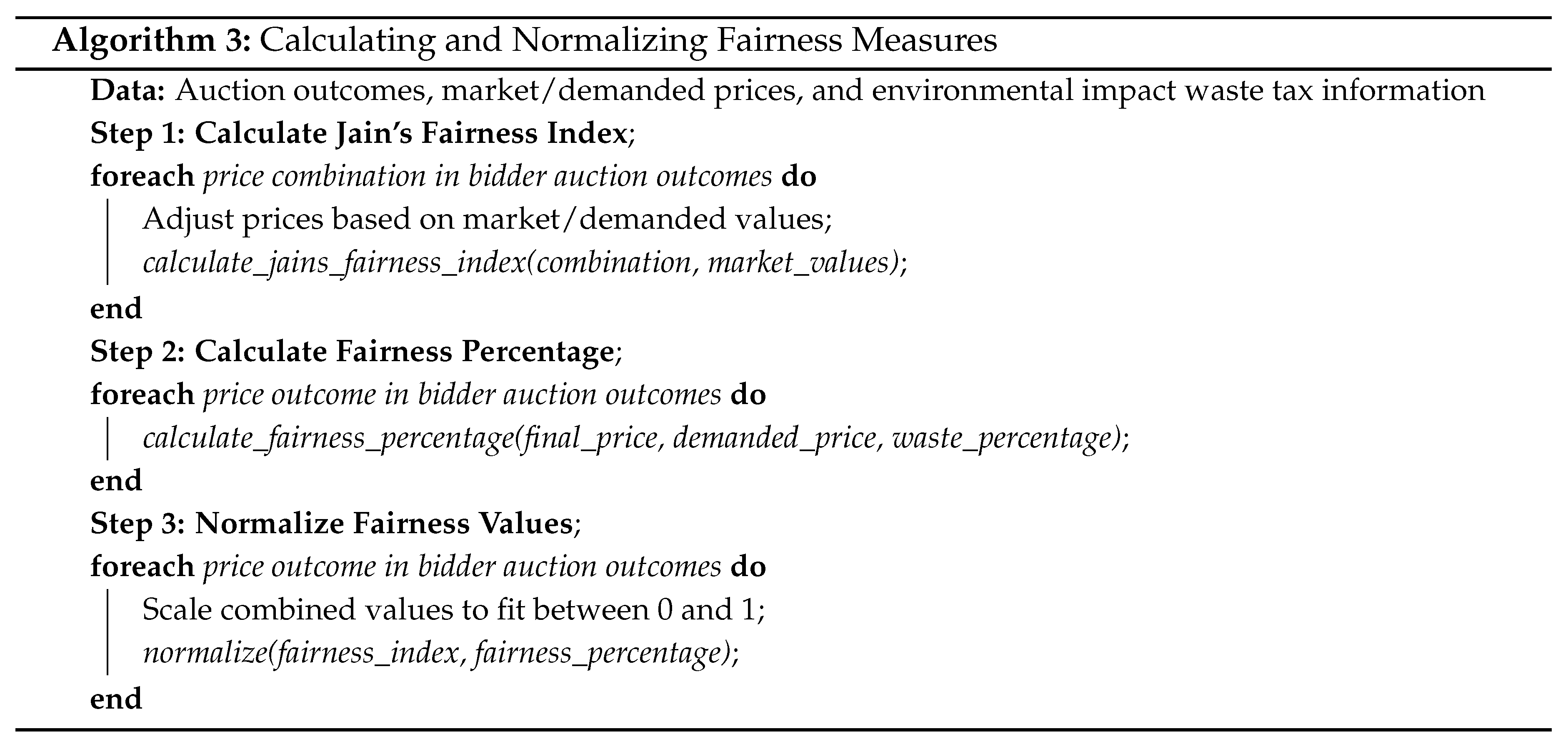

Fairness metrics (Algorithm 3) calculate and normalize fairness measures for the auction outcomes to ensure a balanced allocation of resources. In Step 1, the calculate_jains_fairness_index() function uses Jain’s formula to assess fairness by adjusting each price combination against market or demanded values, providing an initial index of how fairly resources are allocated. In Step 2, the calculate_fairness_percentage() function computes a fairness percentage by comparing the final prices to the demanded prices and accounting for environmental impact through waste taxes. Finally, in Step 3, the normalize() function scales the fairness values to lie between 0 and 1, ensuring that the calculated fairness metrics are consistent and comparable across all outcomes.

Figure 7.

Fairness Assessment Workflow.

Figure 7.

Fairness Assessment Workflow.

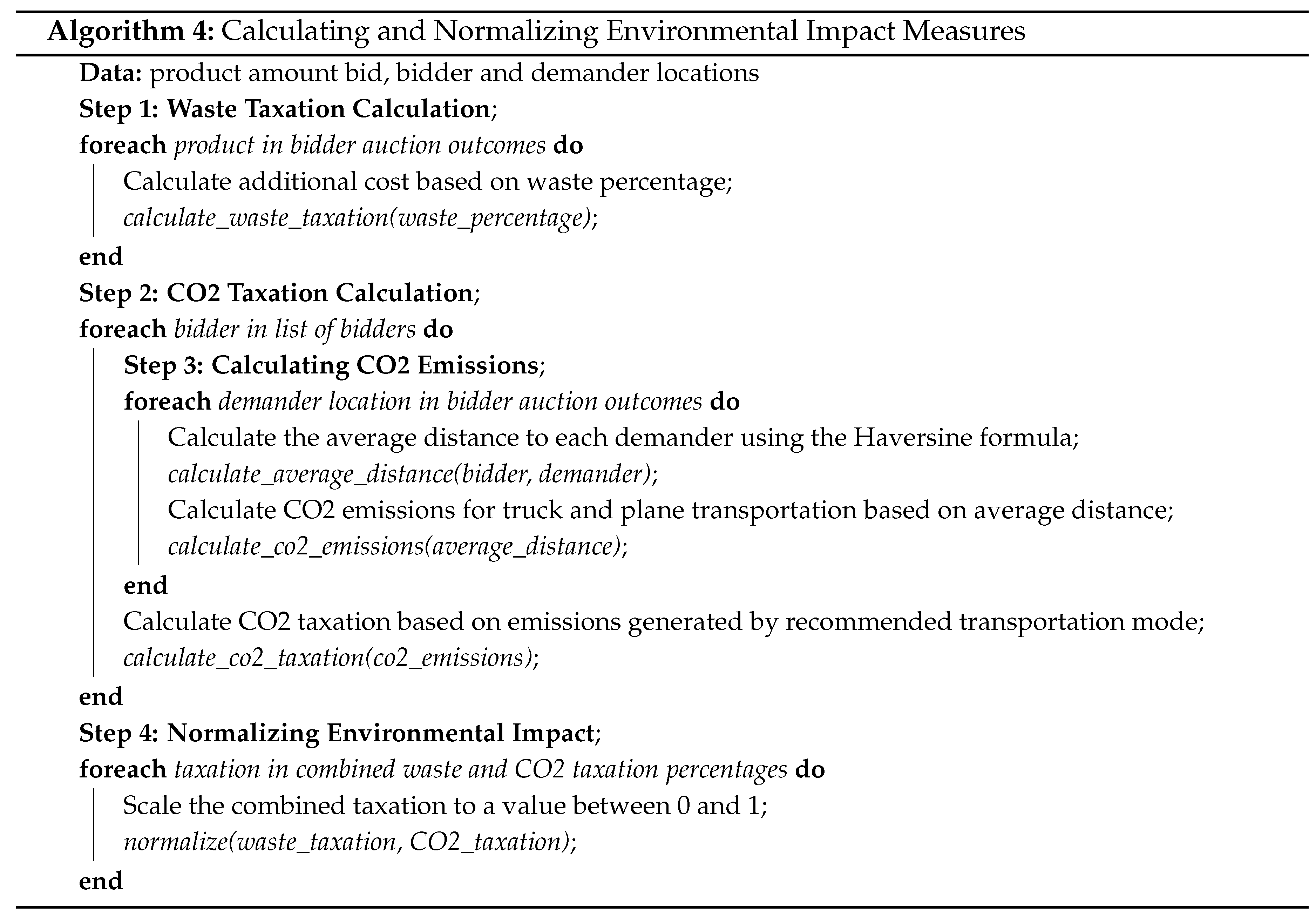

5.2.4. Environmental Impact Metrics Tool

The environmental impact metrics tool was implemented to evaluate and minimize the ecological footprint of auction activities. Key functions include, as shown in

Figure 8:

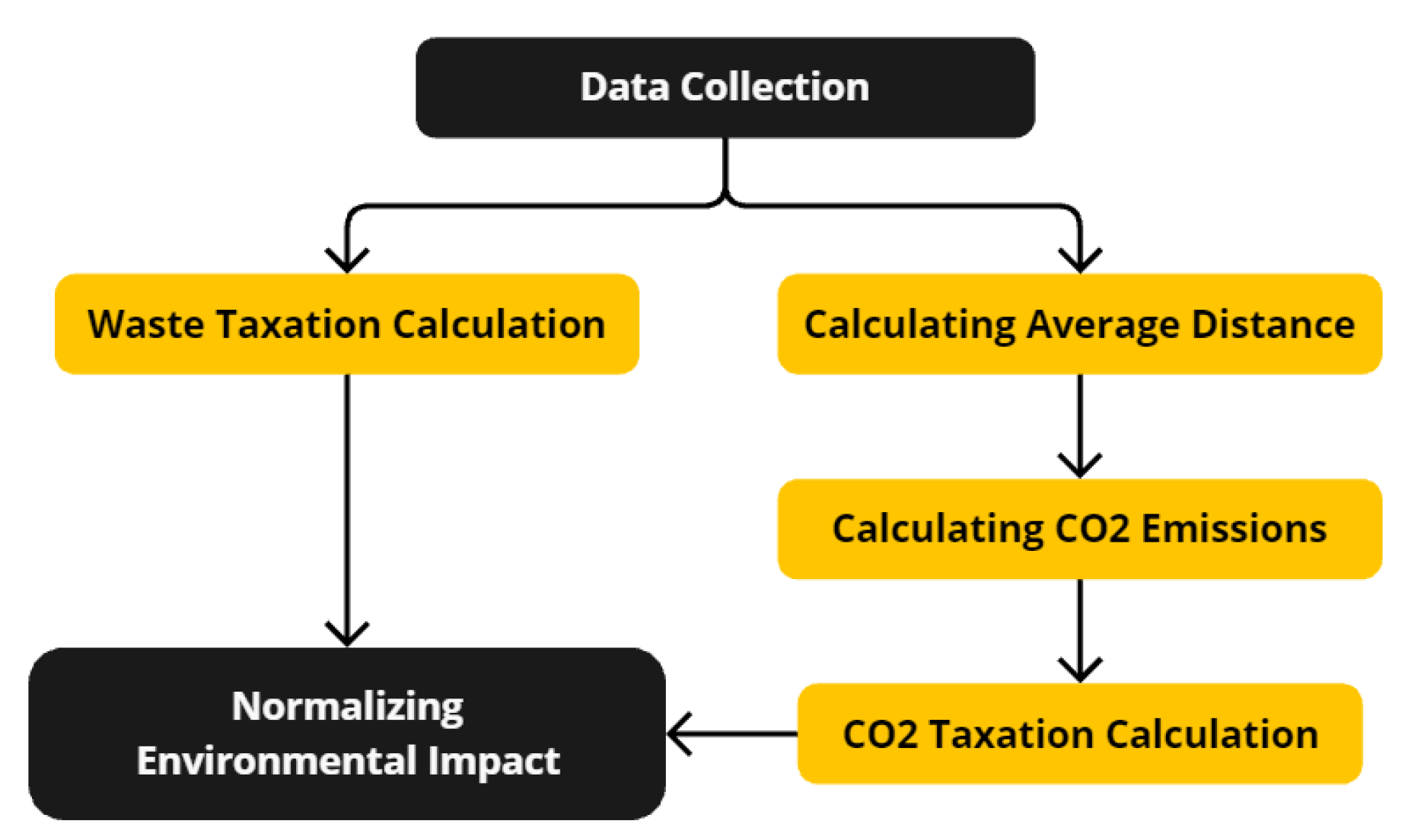

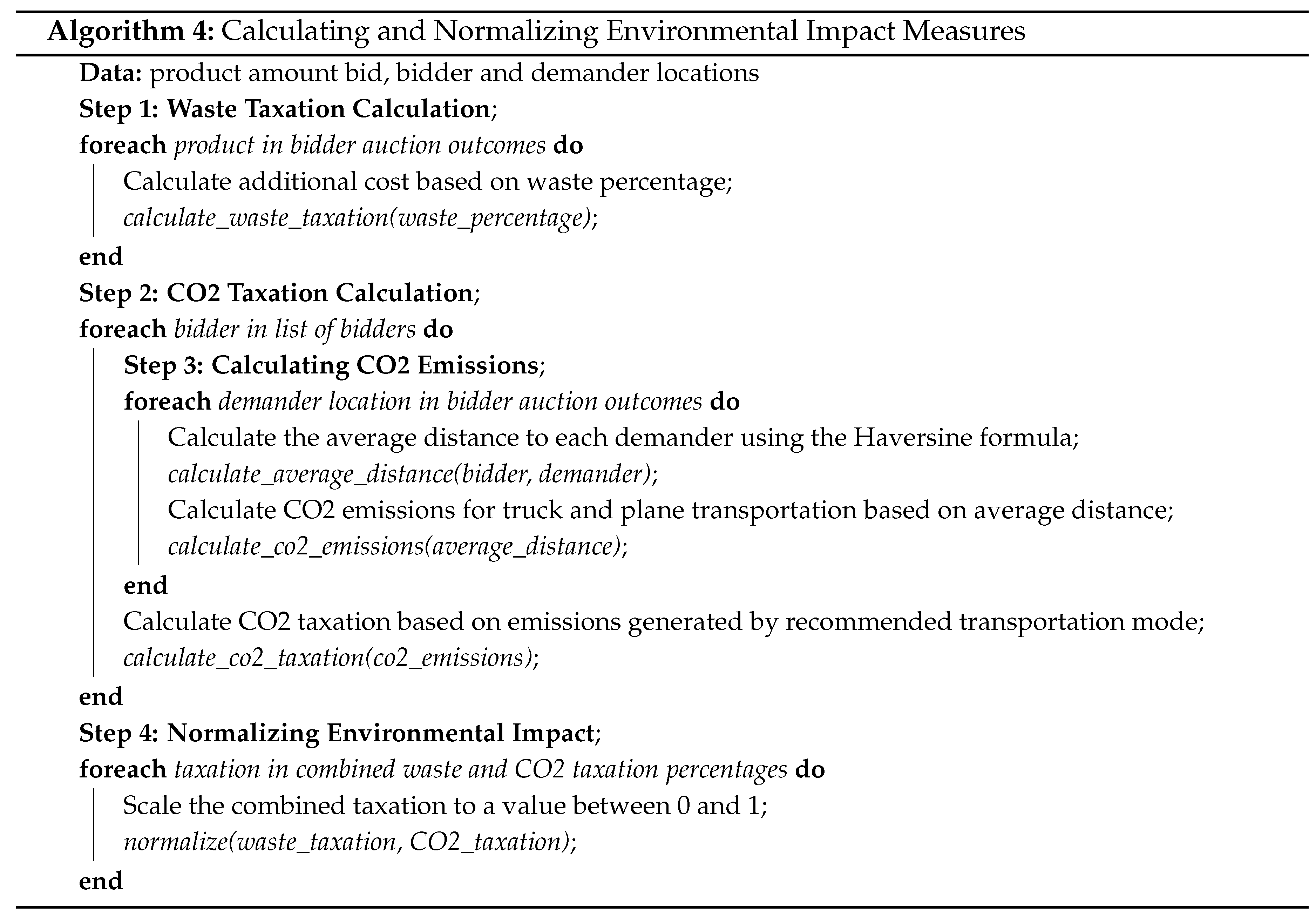

Environmental impact metrics (Algorithm 4) calculate and normalize environmental costs and taxes to promote sustainable practices in the auction process. In Step 1, the calculate_waste_taxation() function computes the additional cost for each product based on the percentage of waste generated. A graduated tax rate is applied to encourage reduced waste, thereby fostering more environmentally friendly production and allocation practices. In Step 2, CO2 taxation is calculated for each bidder by assessing the emissions involved. First, in Step 3, the calculate_average_distance() function determines the average distance between bidder and demander locations using the Haversine formula. Based on these distances, the calculate_co2_emissions() function estimates CO2 emissions for transportation, considering both truck and plane options and recommending the mode with lower emissions. After calculating emissions, Step 2 continues by determining the CO2 tax using calculate_co2_taxation(), which applies a graduated rate to reflect the environmental impact of the transport mode used. This layered approach helps ensure that bidders and suppliers are aware of and financially accountable for their environmental impact, promoting sustainable behavior throughout the auction process. Finally, in Step 4, the normalize() function combines the waste and CO2 taxation values, scaling them to a value between 0 and 1. This normalization provides a consistent and standardized measure of the environmental impact, making it easier to compare and evaluate environmental sustainability across auction outcomes.

Figure 8.

Environmental Impact Assessment Workflow.

Figure 8.

Environmental Impact Assessment Workflow.

5.2.5. Behavioral Dynamics Tool

The bidder behavior dynamics tool passes through a set of parameters that influence their bidding strategies. This tool was implemented using the following, as shown in

Figure 9:

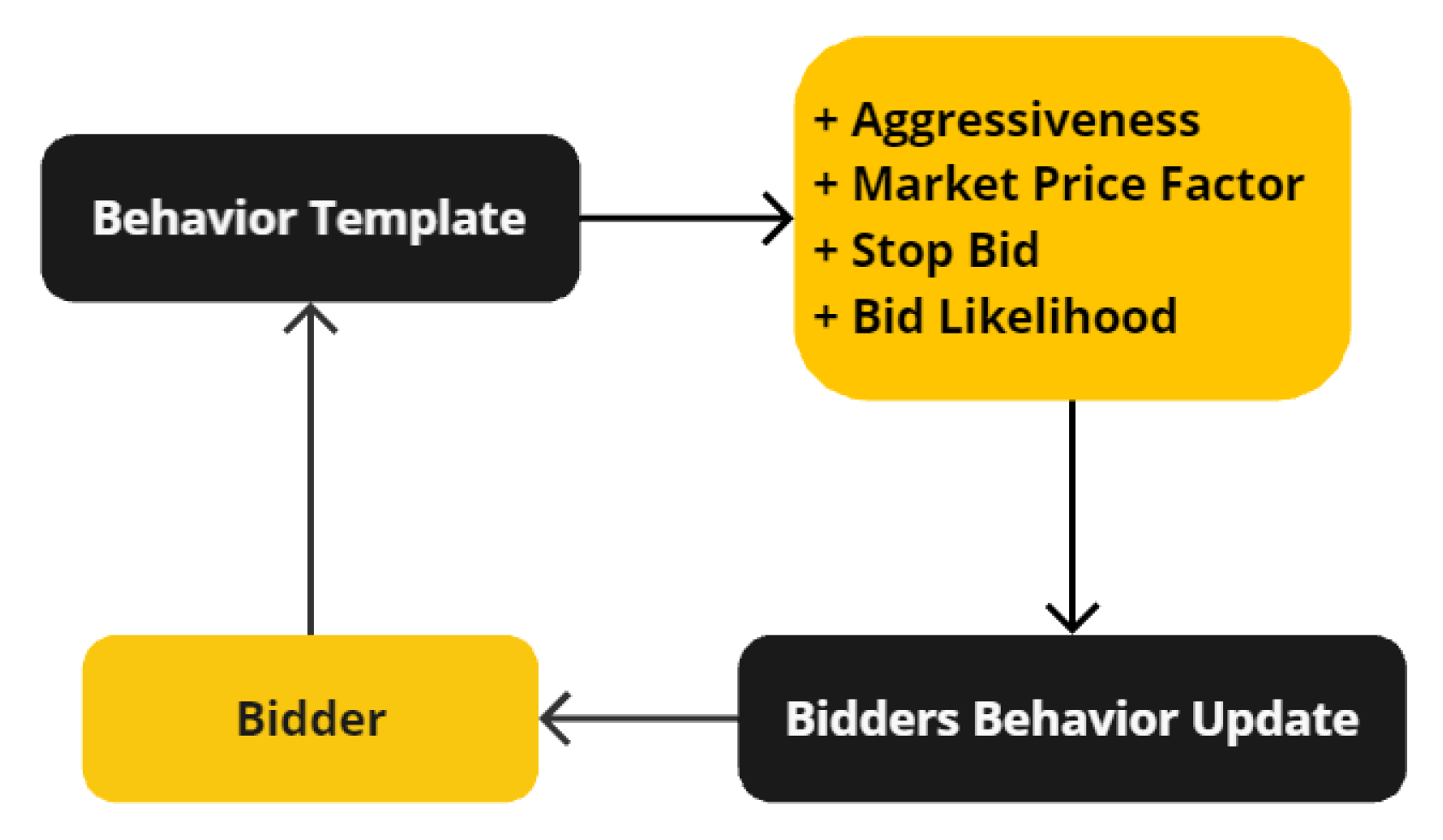

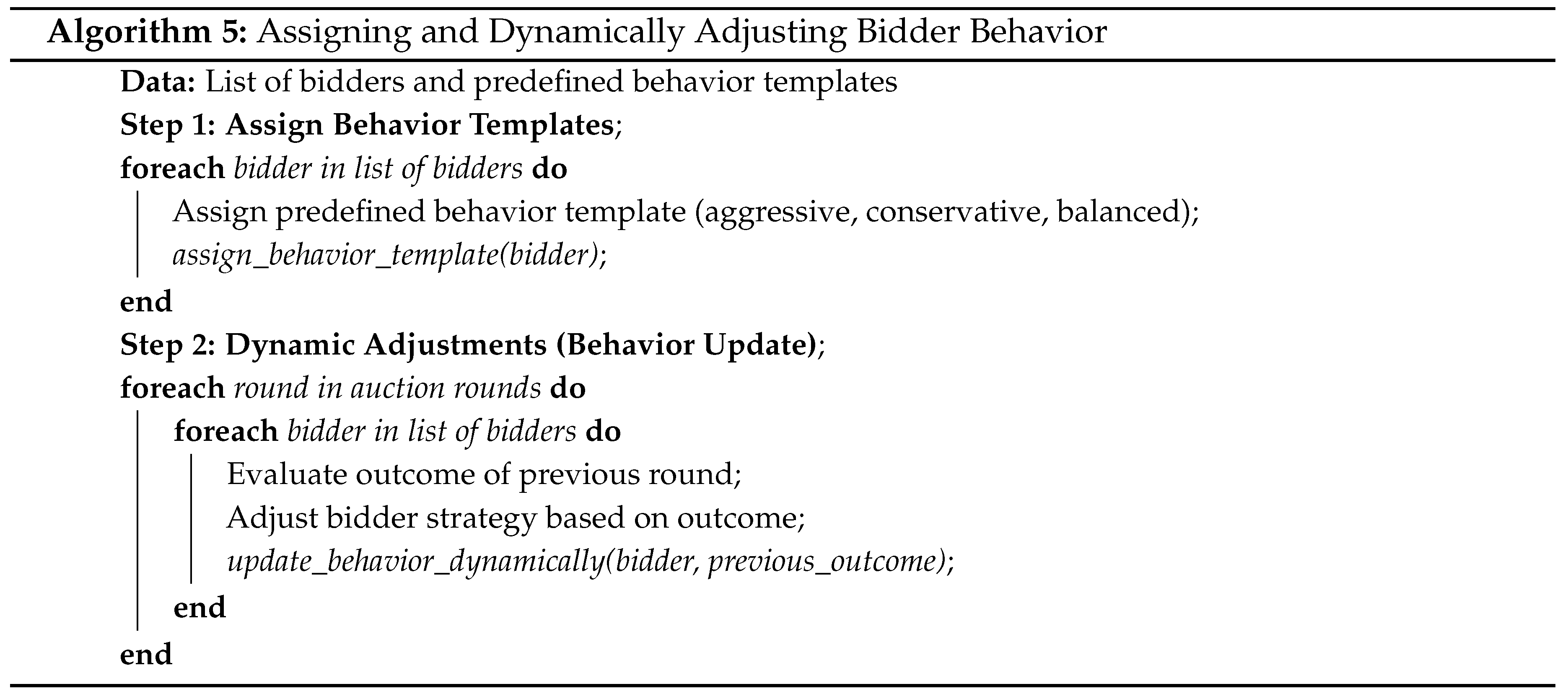

The behavioral dynamics tool (Algorithm 5) demonstrates how bidders adapt their behavior over the course of multiple auction rounds. In Step 1, each bidder is assigned a predefined behavior template—either aggressive, conservative, or balanced—using the assign_behavior_template() function. These templates define how each bidder initially approaches the auction, influencing their bidding strategy and risk tolerance. In Step 2, the bidders are allowed to dynamically adjust their behavior based on the outcomes of previous rounds. Using the update_behavior_dynamically() function, each bidder evaluates their performance after every round and modifies their strategy accordingly. This approach ensures that bidders learn from their experiences and adjust to changing conditions, simulating a more realistic auction environment where participants can adapt to maximize their chances of success. The dynamic nature of behavior adjustment allows for a more nuanced representation of real-world bidding behavior, where strategies evolve in response to competition and outcomes.

Figure 9.

Behavioral Model Workflow.

Figure 9.

Behavioral Model Workflow.

The tool introduced earlier is implemented through a series of calculations that determine each bidder’s actions during the auction. The tool uses predefined behavior templates to assign initial values to each parameter, as shown in

Table 3.

In each round of the auction, the amount bid by the bidder is calculated using the behavior parameters. If the value of a random value between 0 and 1 (

rN) is greater than bid Likelihood (

bH), it would skip the round to give more variation in the bidders’ behavior. However, to ensure more consistent results, we fix the value of

bH to 1.1, as shown in Equation (

1). The bid amount (

bA) that is shown in Algorithm 2 is calculated using the aggressiveness (

agg), block price (

bP), and market price factor (

mpF). If the calculated bid amount exceeds the stop bid (

sB) times the block price (

bP), the bidder stops bidding for that block, as defined in Equation (

2).

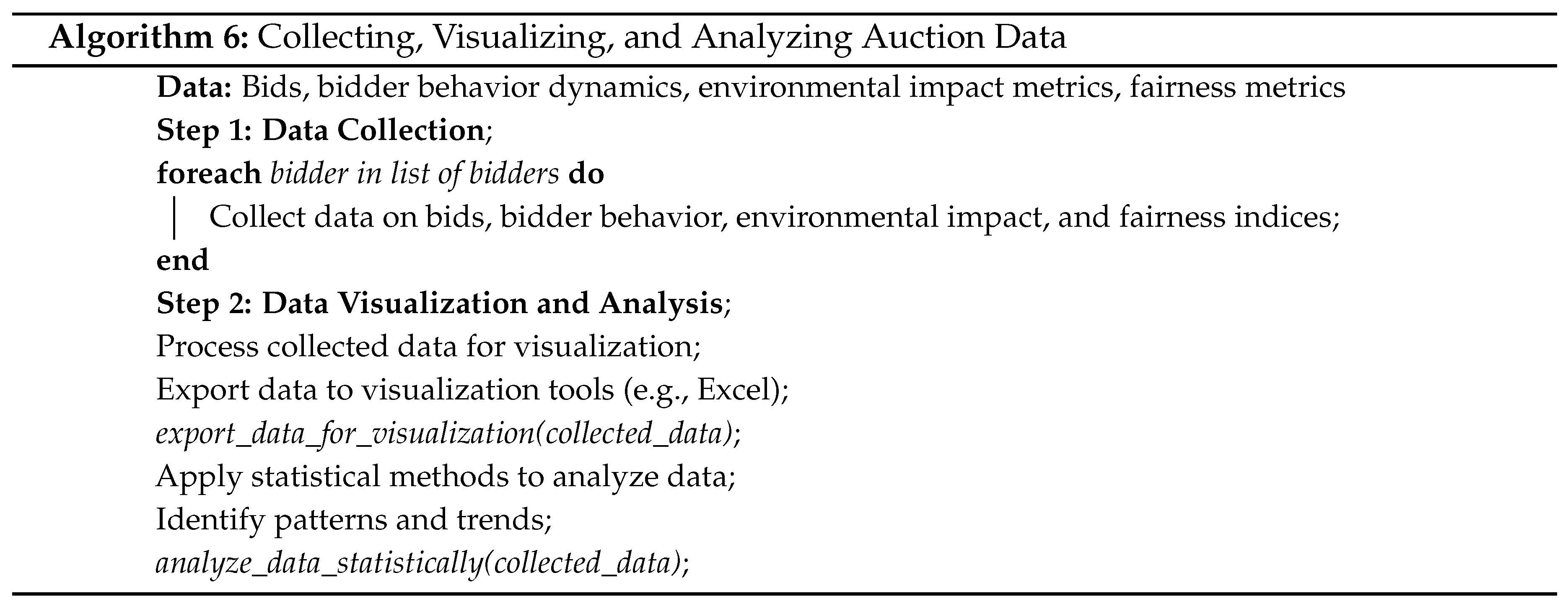

5.2.6. Data Analytics and Visualization

Data analytics and visualization are crucial for interpreting the results of the auction. The implementation involved, as shown in

Figure 10:

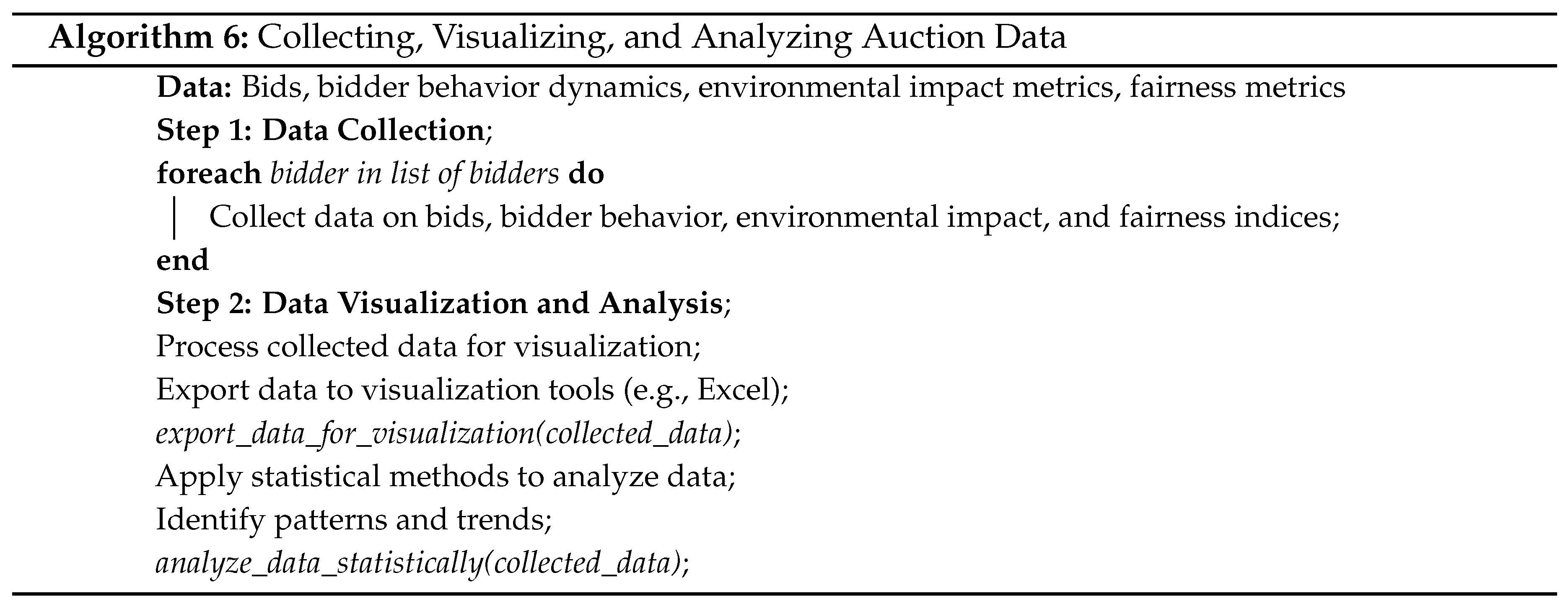

The Data analytics and visualization tool (Algorithm 6) is in charge of the process of collecting, visualizing, and analyzing data generated before and during the auctions. In Step 1, data is collected from each bidder using the collect_data() function. This data includes details on bids, bidder behavior, environmental impact metrics, and fairness indices, ensuring comprehensive coverage of all relevant aspects of the pre-auction and auction. In Step 2, the collected data undergoes both visualization and analysis. The export_data() function makes the data accessible for further review, exporting it to tools like Excel. Simultaneously, statistical analysis is performed to identify trends and patterns that could support strategic decision-making. This dual approach ensures that the collected data is not only presented in an understandable way but also rigorously analyzed to extract actionable insights, ultimately guiding better decision-making in future auctions.

Figure 10.

Data Analytics and Visualization Workflow.

Figure 10.

Data Analytics and Visualization Workflow.

6. Evaluation and Results

This study aims to demonstrate the effectiveness of integrating fairness, environmental impact, and behavioral strategies into auction-based circular economy and supply chain management tools. These tools are essential for Procurement Officers, who need to optimize resource allocation and make sustainable sourcing decisions, and for Regulatory Officers, who ensure that procurement practices align with environmental standards and fairness guidelines. In this section, we present the evaluation and results of our experiments, showing how the proposed framework supports improved decision-making processes, minimizes environmental footprint, and ensures equitable outcomes for all stakeholders.

6.1. Evaluation of the Platform

6.1.1. Evaluation Scenarios

To evaluate the performance and effectiveness of the platform, we tested it across a variety of scenarios that mimic real-world auction conditions. These scenarios were designed to test its performance in terms of fairness, environmental impact, and bidder behavior.

Scenario 1. 10 Bidders and 14 Blocks: In this scenario, we evaluated the outcomes of a single bidder across different types of behavior when all bidders exhibit the same behavior type. The focus was on understanding how each behavior type (aggressive, conservative, balanced) influenced the auction results. The results were then compared to a pre-auction evaluation to assess how well the platform predicted and managed these behaviors.

Scenario 2. 4 Bidders and 8 Blocks: This scenario replicates the first but with a smaller number of bidders and blocks. The goal was to analyze how the reduction in competition affects the auction outcomes and bidder behavior. Again, the focus was on comparing the outcomes of different behavior types against pre-auction predictions to see if the platform could maintain its performance under less competitive conditions.

Scenario 3. 10 Bidders, 14 Blocks, and Mixed Behavior Types: In the final scenario, the platform was tested with 10 bidders and 14 blocks but with a mix of behavior types. Specifically, the bidders were grouped into two categories: Normal (Type A, B, C, and a combination between them), and Moderate (Type D, E, F, and a combination between them). The results for each group were analyzed and compared to determine how mixed behaviors influence fairness, environmental impact, and overall auction efficiency of the simulation.

6.1.2. Evaluation Metrics

To assess the platform’s performance, the following metrics were applied across all scenarios:

Fairness Metrics: Fairness was evaluated using Jain’s Fairness Index, which measures how equitably resources are allocated among bidders. Additionally, we looked at fairness percentage metrics, which compare final pre-auction or auction prices to initial demands and adjust for environmental impact taxes.

Environmental Impact Metrics: Environmental impact was measured through metrics such as waste generated (the difference between the amount needed and the amount received by each bidder) and CO2 emissions related to transportation. These metrics helped assess how well the platform encourages environmentally responsible bidding strategies.

Behavioral Analysis Metrics: Bidder behavior was analyzed by examining bid success rates, overall costs incurred by bidders, and how well bidders could adapt their strategies based on auction progress. This was crucial for understanding the platform’s ability to model and predict the outcomes of different bidder behaviors accurately.

6.2. experimental Platform Setup

The two

Table 4 and

Table 5 show results from the platform in two different scenarios, and that will allow users to compare and observe different parameters that change depending on behavior type. In these tables,

Need is the quantity of goods that the bidder demands,

Supplied is the total quantity supplied by the sellers, which can be one block or a combination of more than one. Then

%Waste and

%CO2 are the extra percentages that would be charged over the total price of the supplies costs (the range in these parameters is between 0% and 30%).

NEI normalize environmental impact,

NF normalize fairness,

Price Total, and

Score are the parameters that would be taken into consideration for the charts that would be presented in the following parts. In this analysis, we use a 50/50 in

Weight, which means that the

Score parameter is divided in the same percentage between environmental impact (

NEI) and fairness (

NF).

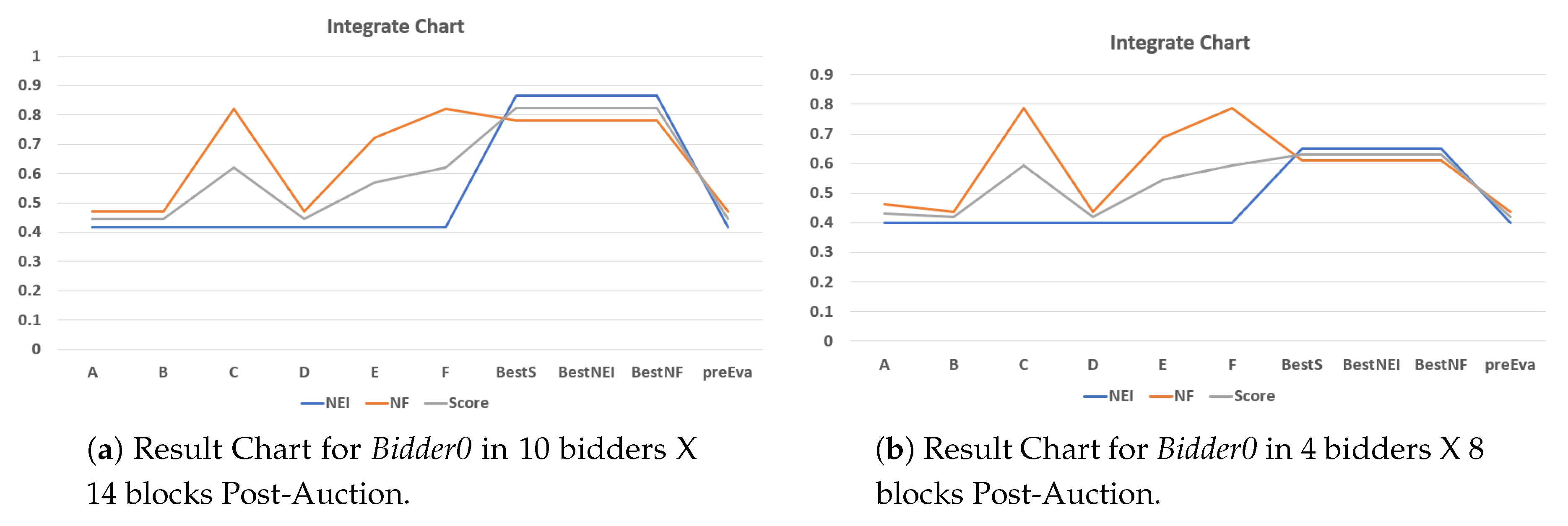

In the Chart

11a,b, we can visually compare the information obtained from the tables. The result of each behavior type can be compared against the best outcome that was obtained from the pre-auction evaluation this parameter is

BestS refer to the best score that

Bidder0 could have obtained fulfilling the demand goods,

BestNEI best environmental impact value,

BestNF best fairness, and

preEva is the outcome pre-auction for the combination of blocks that

Bidder0 had bid and won, it is a useful reference to compare against the outcomes of the auction.

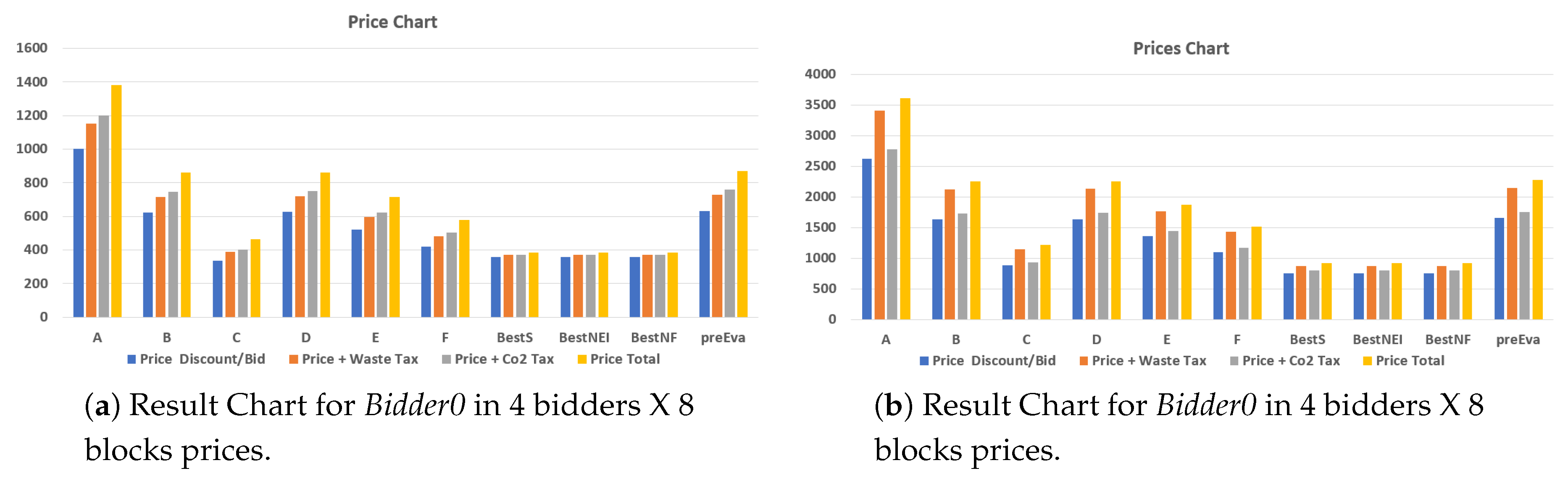

The different prices that are shown in the Chart

12a,b,

Price + Discount/Bid,

Price + Waste Tax,

Price + CO2 Tax,

Price Total are the values that affect Jain’s fairness index. The parameter

Price that is used in each of the different prices of the chart is the outcome price of the auction in the case of the post-auction calculations and the seller price of the block in the case of pre-auction calculations. Also, the first bar in the char change depending if it is a pre-auction or post-auction calculation, in the case of the pre-auction parameter (

BestS,

BestNEI,

BestNF, and

preEva), the first price is referred to the discount that the bidder can obtain if the combination of blocks has two or more blocks from the same seller, trying to emulate a more realistic market. In the case of the post-auction parameter of all the behavior types, the first price considers the winning bid made from the

Bidder0. To calculate

Price Total, we use the price discount/bid with the percentage taxation of waste and CO2.

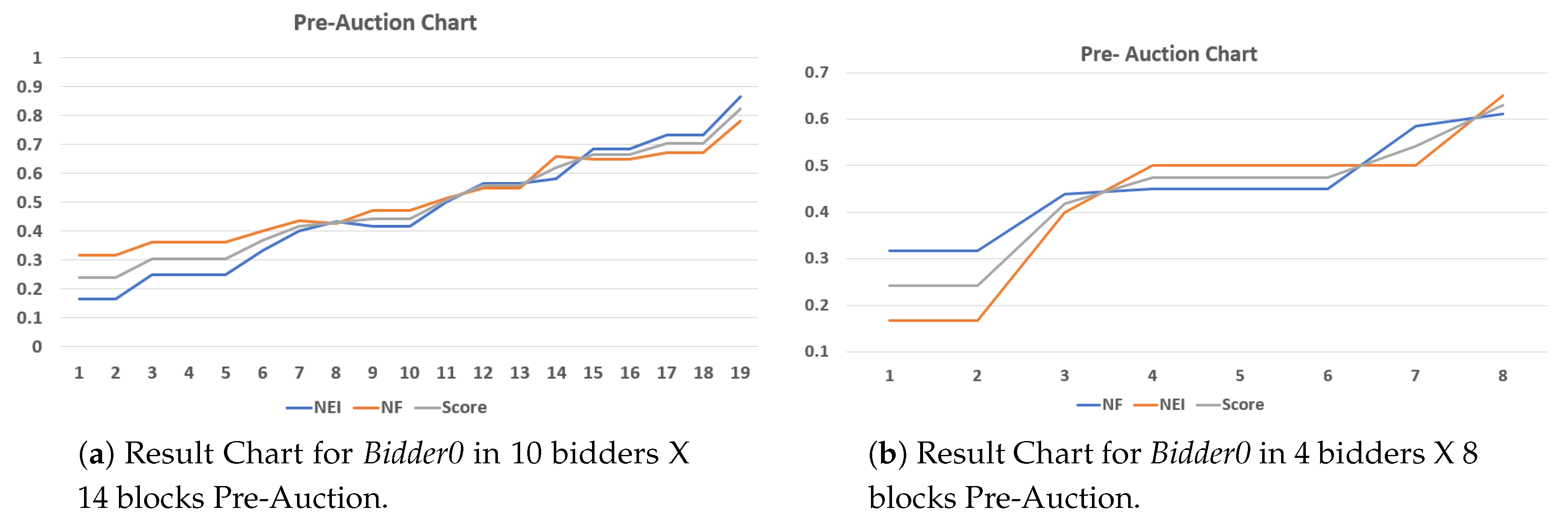

The strategic advantage of conducting a pre-auction evaluation is vividly demonstrated in Chart

13a,b with a visualization of the

Score,

NF, and

NEI. This evaluation score, sorted, allows bidders to analyze and identify optimal block combinations before the auction. It also helps the bidder visualize the

median of this set of blocks offered for auction and find if a good score would be a straightforward approach.

The last charts

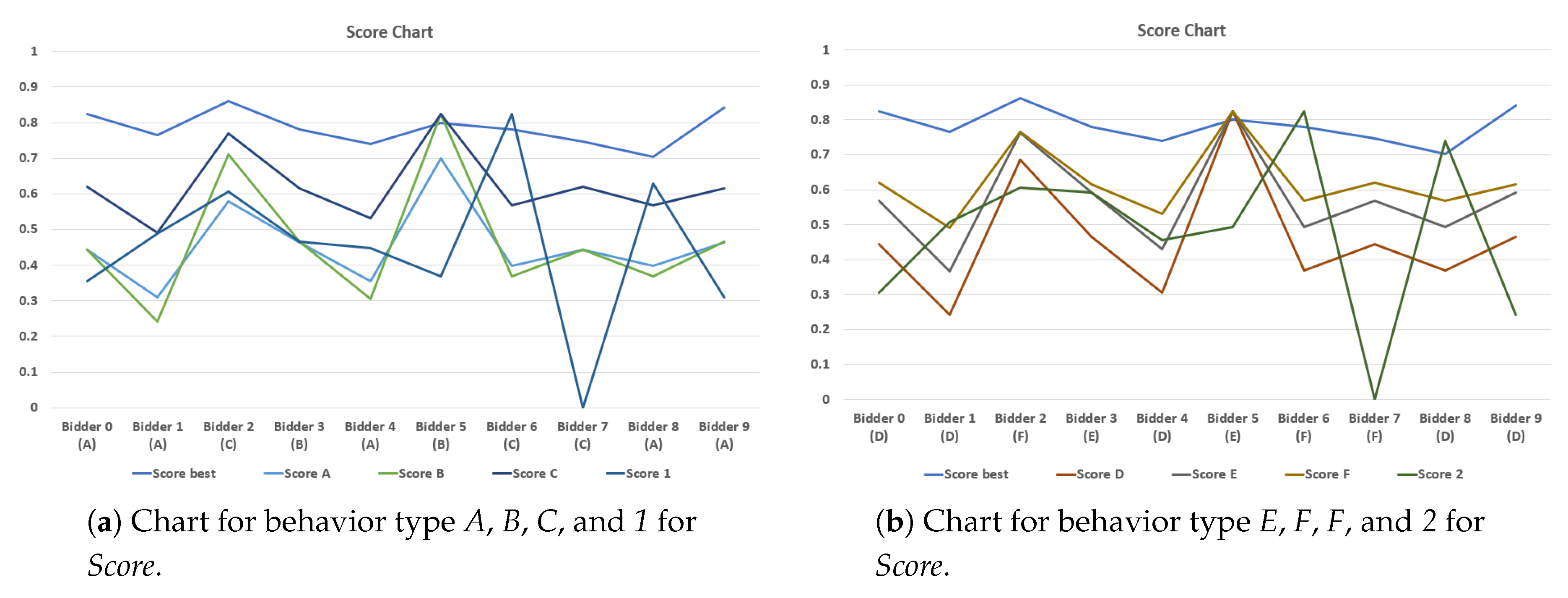

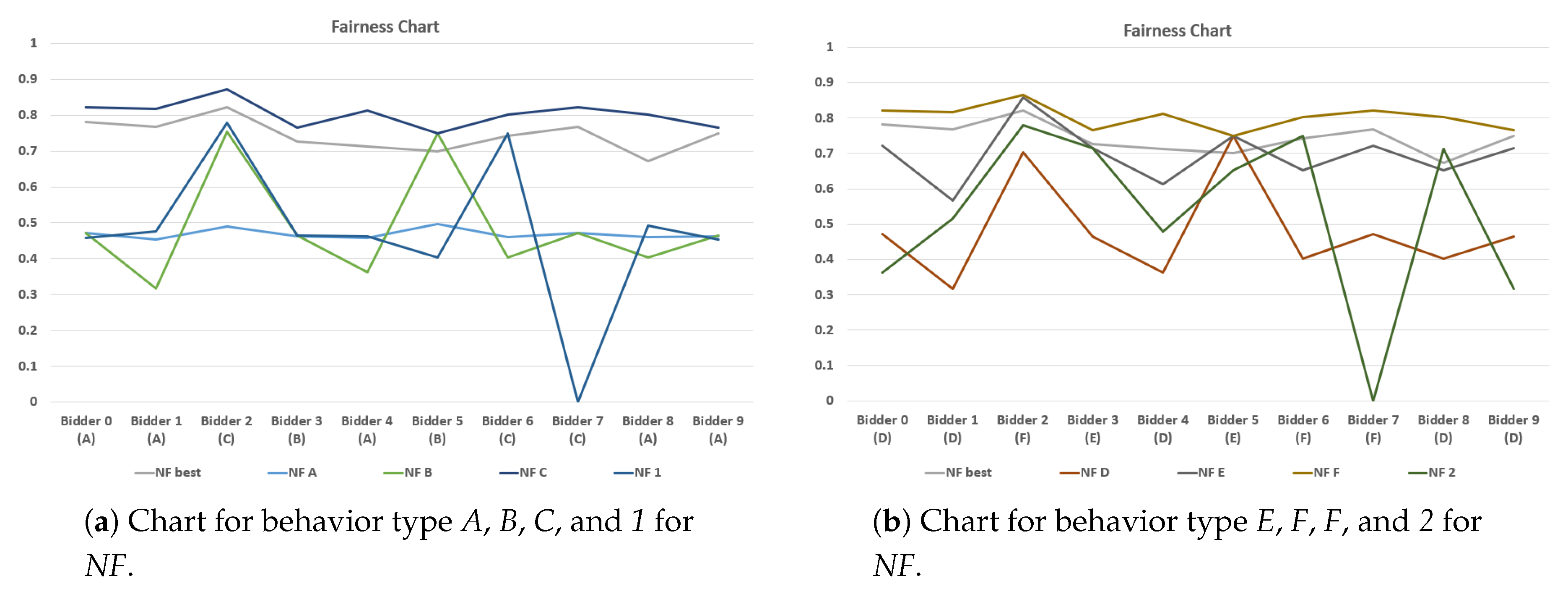

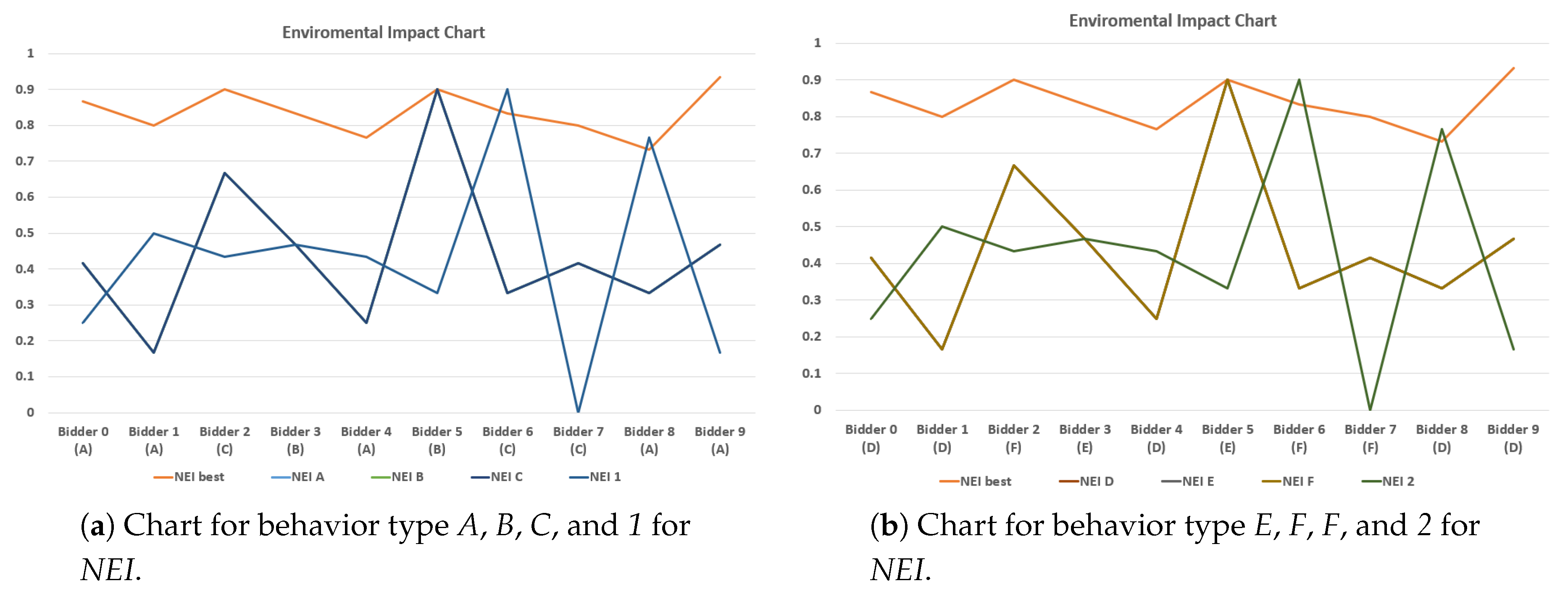

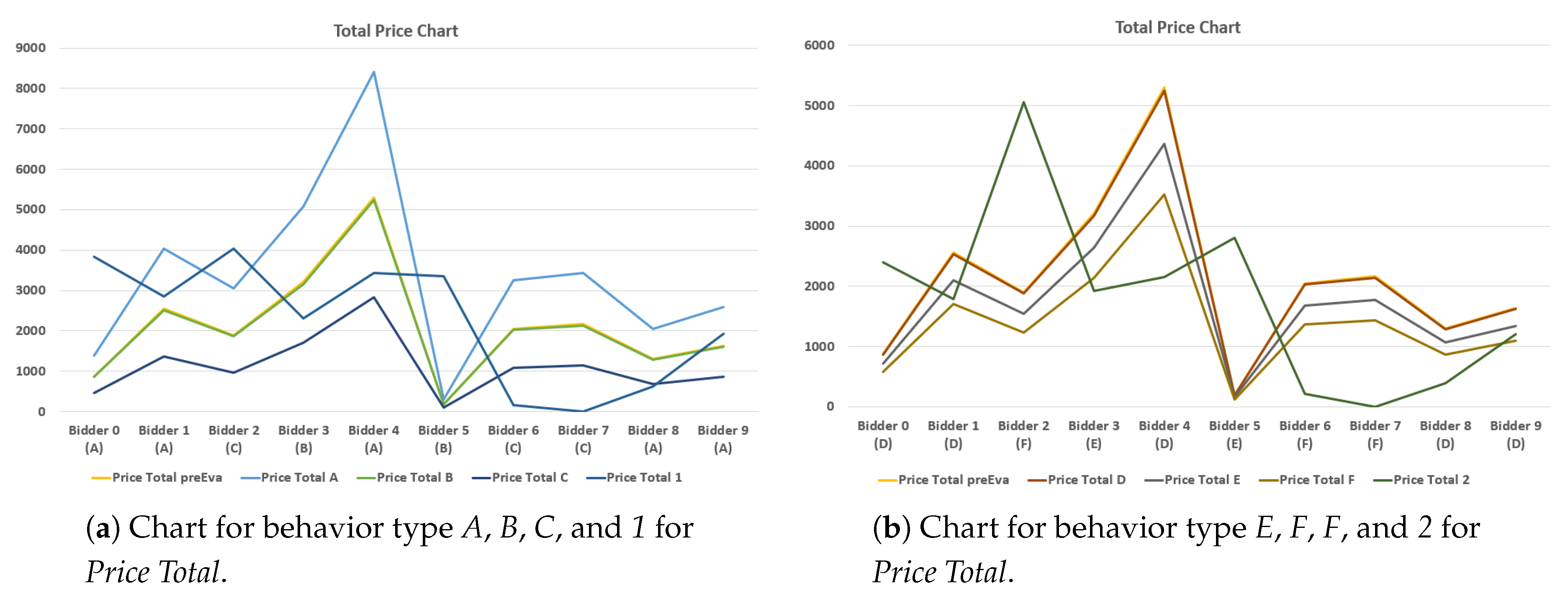

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16 and

Figure 17 are divided mainly into two sections, the

left side showing the behaviors

A,

B,

C, and

1. And the

right side that includes

D,

E,

F, and

2 that in this case behavior

1 and

2 is a combination of the other three respective behavior types of their side.

6.3. Results

This section presents the outcomes from the simulation platform, focusing on the three scenarios outlined in the Evaluation section. The results are analyzed in terms of fairness, environmental impact, and bidder behavior, providing insights into the framework’s effectiveness and potential areas for improvement.

6.3.1. Scenario 1: 10 Bidders and 14 Blocks

In this scenario, the platform was tested with 10 bidders and 14 blocks, evaluating the outcomes for each behavior type of a single bidder when all bidders followed the same strategy. The key metrics, including fairness, environmental impact (waste and CO2 emissions), and price rates, were used to assess performance.

Integrating Fairness and Environmental Metrics

Table 4 shows results from Scenario 1 with 10 bidders and 14 blocks. Type C (Conservative Bidder) achieved the highest score, emphasizing the effectiveness of conservative strategies in balancing fairness and environmental sustainability. Specifically, Type C and F, which balanced fairness and environmental impact, achieved a combined score of 0.6193. This suggests that it is possible to achieve both environmental goals and fairness without compromising on either.

The charts in

Figure 11a and

Figure 13a illustrate how different bidding strategies impacted the outcomes. The analysis challenges the assumption that higher environmental impact results in lower fairness, as shown by the relatively high fairness score (

NF) achieved by Type F, despite a high environmental impact (

NEI).

Price Analysis

The pricing charts (

Figure 12a) reveal how the different bidding behaviors impacted the final costs. For Scenario 1, the aggressive bidding strategy of Type A resulted in the highest total price, while conservative bidders managed to maintain a lower total price. This variation directly influenced the fairness index (Jain’s Fairness Index), demonstrating the interconnectedness of economic, environmental, and fairness considerations in auction results.

Key Findings:

Fairness: The platform demonstrated high fairness across all behavior types, with minor variations. Aggressive bidders (Type A) tended to win more blocks but at a higher cost, while conservative bidders (Type C) showed lower costs but fewer wins.

Environmental Impact: Aggressive bidding led to higher CO2 emissions and waste due to the larger number of blocks won, highlighting the trade-off between competitiveness and sustainability.

Bidder Behavior: The pre-auction evaluation closely predicted the auction outcomes, indicating the platform’s strong ability to model and manage bidder behavior effectively.

The results from Scenario 1, as shown in

Table 4, indicate that Type C (Conservative Bidder) achieved the highest combined score within this specific scenario. This outcome suggests that, in the context of the DSM framework, conservative bidding strategies were more effective at balancing fairness and environmental sustainability in a highly competitive auction environment. In contrast, the aggressive bidding strategy of Type A resulted in higher associated costs, which adversely affected its overall score.

6.3.2. Scenario 2: 4 Bidders and 8 Blocks

This scenario examined how the platform performs with fewer bidders and blocks. The results revealed how reduced competition impacts fairness, environmental impact, and the effectiveness of different bidding strategies.

Integrating Fairness and Environmental MetricsTable 5 presents the results from Scenario 2, with 4 bidders and 8 blocks. In this scenario, the balanced bidder (Type B) performed consistently, managing to achieve a good balance between fairness and environmental impact. The reduced competition allowed for more equitable outcomes, with Type F again showing strong performance in balancing both metrics.

The charts in

Figure 11b and

Figure 13b highlight the impact of different bidding strategies on the outcomes. The strategic advantage of pre-auction evaluation is clear, as bidders who used this information were able to achieve more competitive bids and better alignment with their objectives.

Price Analysis The pricing charts (

Figure 12b) from Scenario 2 show that even in a less competitive environment, the pricing varied significantly depending on the bidding strategy. Conservative bidders were able to maintain lower costs, but with fewer blocks available, the overall impact on fairness and environmental scores was more pronounced than in Scenario 1. This reinforces the importance of considering both fairness and environmental metrics in auction strategy.

Key Findings:

Fairness: Fairness metrics remained consistent with Scenario 1 but with slightly reduced variation due to fewer bidders.

Environmental Impact: Lower competition led to less aggressive bidding, reducing the overall environmental impact.

Bidder Behavior: The platform continued to accurately predict outcomes, though the impact of the strategy was less pronounced in a less competitive environment.

In Scenario 2, as shown in

Table 5, where there were fewer bidders, Type B (Balanced Bidder) performed consistently well. The reduced competition in this scenario led to more equitable outcomes in terms of fairness and environmental metrics, indicating that balanced strategies can be particularly effective under conditions of lower competition within the DSM framework.

6.3.3. Scenario 3: 10 Bidders, 14 Blocks, and Mixed Behavior Types

This scenario assessed the platform’s ability to handle mixed bidder behaviors, comparing outcomes for aggressive, conservative, and balanced strategies within a single auction. The focus was on how mixed strategies influence overall fairness, environmental sustainability, and auction efficiency.

The results first reveal that for bidders with behavior types 1 and 2, one bidder (Bidder 7) did not win any blocks during the auction. This is reflected as a low spike in all the charts. Additionally, the metrics Score best, NF best, and NEI best serve as references, indicating the best possible outcomes for each parameter across the different bidders.

In the Chart

14a,b, bidders with behavior types

C and

F achieved outcomes closest to these references. Notably, in behavior types

1 and

2, bidders with more conservative strategies generally performed better, except for one aggressive bidder who secured a favorable outcome by being the last to bid, potentially benefiting from lower prices as other aggressive bidders had already fulfilled their needs.

The Chart

15a,b show that, on average, bidders with behavior types

1 and

2 tend to achieve higher values compared to other behavior types, except for types

C and

F, which exhibit the best results. Despite this, the other types demonstrate a more balanced average outcome among their respective bidders.

The Chart

16a,b, behavior types

1 and

2 show better average and more balanced outcomes compared to other behavior types when compared against pre-auction values.

Lastly, the analysis

Figure 17a,b, indicates that aggressive bidding strategies, like those of Type

A, tend to increase total costs. In contrast, balanced or strategic approaches, represented by Types

C and

F, consistently result in higher overall scores and better fairness (

NF) metrics. This suggests that these strategies are more effective in achieving equitable outcomes by integrating fairness and environmental considerations into the bidding process. Additionally, behavior types

1 and

2 tend to produce more average outcomes across bidders, suggesting they may offer a different but viable strategic approach.

Key Findings:

Fairness: Bidders with conservative strategies generally led to more favorable outcomes in fairness metrics compared to purely aggressive or balanced strategies. Bidders with mixed behaviors (Types 1 and 2) showed more balanced but average outcomes, indicating a viable yet less extreme strategic approach.

Environmental Impact: Mixed behaviors introduced more variability in environmental impact, with balanced strategies typically showing better performance.

Bidder Behavior: The platform successfully managed the complexities of mixed behaviors, demonstrating robustness in diverse auction environments.

In summary, the mixed behavior scenario offered insights into the interactions between different bidding strategies within the DSM framework. The results indicate that aggressive bidders (Type A) tend to dominate in securing the most blocks. However, when considering fairness and environmental impact metrics, balanced and conservative bidders (Type B and Type C) achieve higher overall scores. This outcome underscores the importance of integrating diverse bidding strategies within the DSM framework to achieve more balanced and sustainable auction outcomes.

6.4. Summary of Key Findings

The results demonstrate that the Demand-Supply Matchmaking (DSM) platform successfully integrates fairness and environmental metrics into the auction process, supporting Procurement Officers and Regulatory Officers in achieving balanced and sustainable decision-making. Specifically, the platform effectively manages multiple objectives, such as maintaining fairness and minimizing environmental impact, without significantly compromising either. This balanced approach results in auction outcomes that are cost-effective, fair, and environmentally conscious, aligning closely with the platform’s goals of strategic and responsible decision-making.

6.4.1. Strategic Bidding Advantage

Pre-auction evaluations within the DSM platform provide bidders, including procurement officers, with strategic insights that enable the selection of block combinations that minimize waste and reduce environmental impact. This proactive approach leads to more competitive bids, lowers overall costs, and improves fairness metrics post-auction. By leveraging these evaluations, procurement officers can align their strategies effectively with both their organizational objectives and the broader sustainability goals of the DSM framework, achieving more favorable and sustainable outcomes.

6.4.2. Impact of Bidder Behavior

The findings from the DSM platform indicate that aggressive bidding strategies while offering potential short-term gains, are often linked to higher overall costs and lower fairness scores within this auction framework. In contrast, balanced and conservative strategies, especially those informed by pre-auction evaluations, produce more sustainable and equitable outcomes. For regulatory officers, these findings underscore the importance of incorporating fairness and environmental considerations into auction systems, especially in circular economy initiatives and supply-chain management.

6.4.3. Mixed Behavior Insights

The analysis of mixed bidding strategies within the DSM platform reveals that aggressive bidders tend to secure a greater number of blocks, while balanced and conservative bidders achieve higher scores in terms of fairness and environmental impact. For procurement officers, these results highlight the value of incorporating diverse bidding strategies to reach sustainable outcomes using the DSM framework rather than relying solely on aggressive tactics.

6.4.4. Platform Strengths

The DSM platform is effective in maintaining fairness and minimizing environmental impact across various scenarios involving both homogeneous and mixed bidder behaviors. This adaptability demonstrates its potential for real-world supply-chain and market applications, supporting regulatory officers in verifying compliance and procurement officers in achieving sustainable resource allocation. However, trade-offs between fairness, environmental impact, and competitiveness suggest that further model refinement could enhance its performance, particularly in managing highly aggressive or risk-averse strategies without compromising sustainability goals.

7. Discussion and Future Work

The implications of the findings from this demand-supply matching for auction framework are substantial and have been able to influence various domains such as policy-making, market practices, and sustainable development. By integrating fairness and environmental impact assessments, this framework provides Regulatory Officers with tools to enforce eco-friendly and fair market operations, helping to shape policy rules that prioritize these values. For Procurement Officers, the framework can optimize bidding strategies, making procurement more competitive and sustainable. Modeling bidder behavior provides deeper insights that enable more effective and equitable auction system designs, benefiting both regulatory oversight and procurement planning.

Potential Usage:

Policy-Making: The framework’s ability to assess fairness and environmental impact has potential policy implications, promoting equity and sustainability in market operations to support regulatory officer goals.

Market Practices: Businesses and procurement officers can use the framework to improve bidding strategies, cut costs, and lower environmental impact, promoting competitive and sustainable practices.

Sustainable Development: By highlighting environmental costs, the framework aligns procurement strategies with global sustainability goals, reducing carbon footprints and advancing circular economy principles.

7.1. Future Work

There are several promising areas for future research and development to improve this framework.

Integration of Real-Time Data: Real-time data can enhance decision-making for procurement and regulatory officers by providing up-to-date market conditions, environmental metrics, and bidder behavior insights for dynamic strategies.

Exploring Additional behavioral analytics: Expanding behavioral analytics to include more complex bidding dynamics can increase simulation accuracy, helping both officers anticipate outcomes and ensure fair practices.

Enhancing Environmental Impact Metrics: Developing comprehensive environmental metrics, including lifecycle analysis, can provide a more complete picture of ecological impacts, supporting regulatory officers’ sustainability goals.

8. Conclusions

In this work, we developed a framework that integrates environmental impact assessments, fairness metrics, and behavioral analytics to optimize auction strategies. Key contributions include:

Environmental Impact Considerations: By incorporating CO2 emissions and waste management, the framework aids regulatory officers in enforcing sustainable practices and helps procurement officers minimize the ecological footprint of procurement activities.

Fairness Assessment: Using Jain’s Fairness Index and other fairness metrics supports equitable outcomes, addressing procurement and regulatory concerns around fair auction practices.

Behavioral analytics: The framework’s modeling of various bidder behaviors provides strategic insights, aiding procurement officers in supplier selection and helping regulatory officers ensure ethical bidding.

By addressing these aspects, the DSM framework facilitates more sustainable and equitable market practices, specifically by aligning economic efficiency with environmental management and fairness considerations within auction settings. This focused approach paves the way for targeted innovations, such as integrating real-time data, enhancing environmental metrics, and incorporating advanced behavioral analytics into the platform, further supporting the strategic roles of procurement and regulatory officers.