1. Introduction

Water degradation is often caused by the intensification of agricultural activities. Especially around the rural landscape of the Mediterranean region, agriculture has led to the overexploitation of water reserves for irrigation and to the decline in water quality due to non-point source pollutants like fertilizers and pesticide residues entering water bodies [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. While intensive agriculture is crucial for food, feed and fiber production, achieving a balance with water quality and quantity is a challenge. Therefore, appropriate management practices are required, to accomplish these conflicting objectives and meet the objective of good ecological status required by the Water Framework Directive (WFD) (Directive 2000/60/EC, 2000) and Nitrates Directive (Directive 91/676/EEC) [

6].

In addition, agriculture is being promoted globally as a significant method for sustainable energy production through the cultivation of bioenergy crops for renewable energy. The European Union (EU) has implemented measures to advance biofuels through the Renewable Energy Directive (Directive 2018/2001), which is part of the European Green Deal aiming for a climate-neutral EU by 2050. Biomass and biofuels are seen as promising energy sources within the current energy crisis in the EU, as they can be produced domestically, thereby reducing dependence on energy imports. The need to increase bioenergy production in Greece has been recognized over the past decades [

7]. Efforts to increase combined heat and power production from biomass and replacement of portions of gasoline and diesel by liquid biofuels has been reported from more than a decade ago [

8]. However, the national use of renewable energy sources remains low. As an EU member state, Greece must comply with the European Directive, which, for example, mandates that biofuels should contribute with >10% to total transport energy consumption by 2030 [

9].

Apart from the energy targets, bioenergy production can however have positive environmental impacts, when it comes from bioenergy crops that are incorporated within existing resource demanding cropping systems. Specifically, perennial bioenergy crops are considered as a viable option, since they have the capacity to substantially reduce nitrate losses and subsequently reduce nonpoint source pollution [

10]. In addition, bioenergy crops like sunflower and sorghum, require less irrigation water than the majority of irrigated crops, enhancing groundwater conservation [

11]. In particular, the perennial bioenergy crop switchgrass, introduced from the US, characterized as low input, is expected to exhibit similar behavior. Nevertheless, producing bioenergy requires extensive agricultural areas, often leading to significant land use changes. Therefore, it is essential to assess a bioenergy crop’s socio-economic and environmental footprint before selecting it for regional planning. In Greece, no such plan has yet been proposed for any agricultural region to ensure continuous, uninterrupted production of bioenergy products.

The Thessaly plain, located in the center of Greece, represents the most important agricultural producer in the country. The largest river basin in the area is Pinios river basin (PRB), covering roughly 11,000 km

2. It is characterized by Mediterranean climate, fertile soils and mild topography and is considered ideal for a variety of crop cultivations. These characteristics have caused the intensification of irrigated agriculture in the region with water quantity and quality implications [

5,

12]. The region is included in the list of areas characterized as nitrate vulnerable zones, with a negative water balance [

13].

For the assessment of land use changes at the river basin scale, including changes in cropping patterns and their effects on water resources, advanced hydrological models that can provide time-efficient water quantity and quality predictions are widely utilized. Specifically, the process-based Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) model, has been used worldwide in a wide range of studies, among which, one can find a few with bioenergy crops simulation [

14,

15,

16]. Of substantial interest for the present paper are the SWAT studies with bioenergy crops that have highlighted a significant nitrate loss reduction and considerable biomass accumulation for potential energy production, even when grown in low-productivity areas [

17,

18]. Moreover, Gassman et al. [

19] have found that the realistic, limited inclusion of bioenergy crops within agricultural systems, can result to considerable reduction of nitrate loss from land to water.

This study aims to build a dynamic SWAT hydrologic and management model of the intensively managed PRB that will consider climate, land use and agricultural practices to estimate crop yields and evaluate the resulting water quantity and quality of surface and groundwaters. Within this model, the study is the first to attempt a realistic simulation of switchgrass growth cycle in Greece and execute rough scenarios of its implementation across large agricultural areas in order to explore potential upper levels of water improvements and biomass production at the river basin scale.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

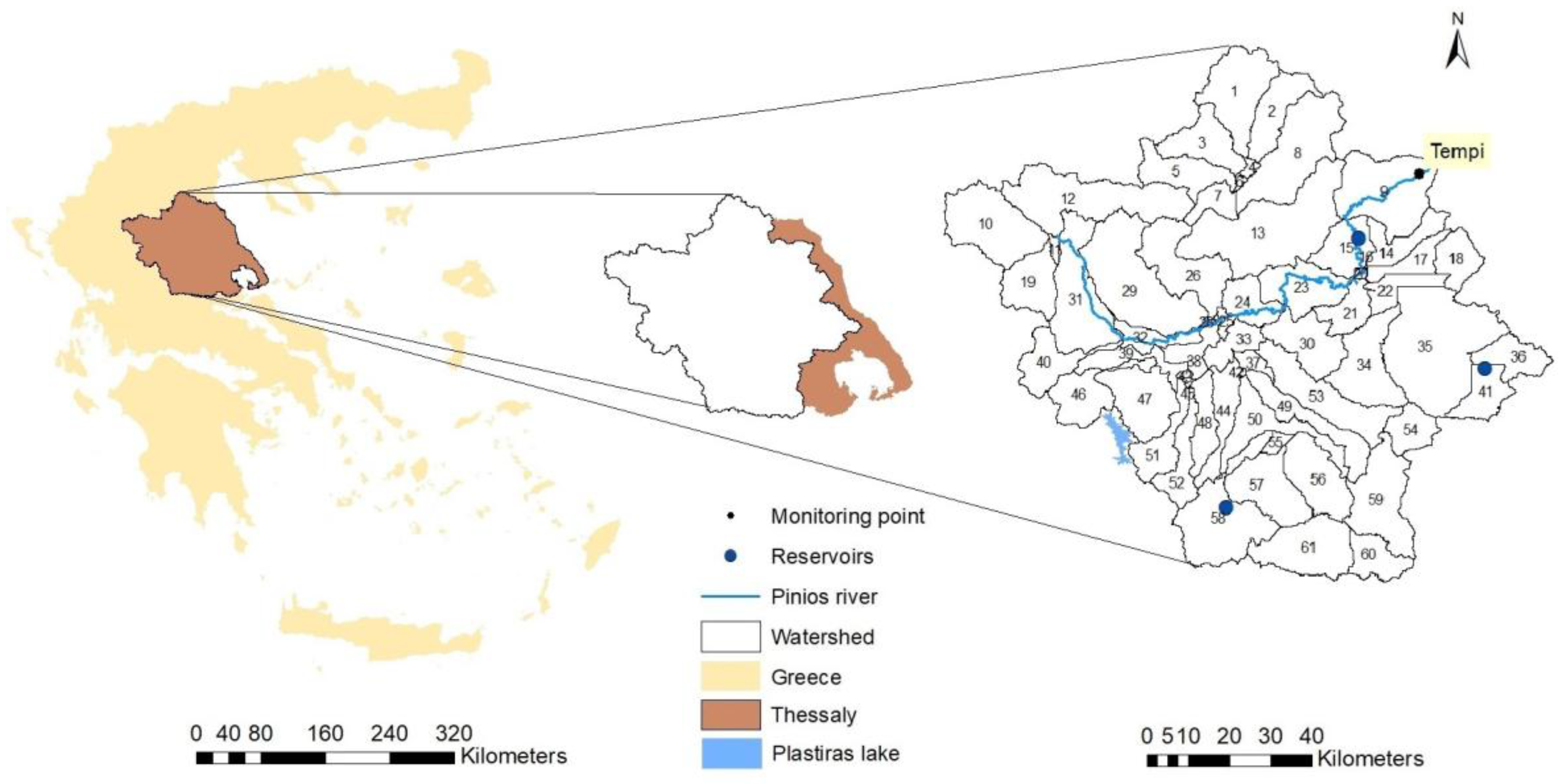

Pinios river basin covers almost entirely the river basin district (RBD) of Thessaly, which is located in Central Greece, as can be observed in

Figure 1. Specifically, it covers an area of about 11,000 km

2 and is the most important agricultural producer in the country. Agriculture is associated with almost 45% of the total basin’s area [

20]. According to the Hellenic Statistical Authority, sector of Agriculture, Livestock, Fishery for the year 2022, crops on arable land cover 80% of the total cultivated agricultural and fallow land [

21]. The main crops cultivated in the PRB are cotton and wheat followed by much smaller areas of corn and alfalfa. The average annual precipitation in the basin is estimated at 700 mm [

22,

23] and the average annual river flow after 'Tempi' location and near the outlet (

Figure 1) is roughly 80 m

3/s as reported by Panagopoulos et al. [

12].

The region has been classified as a nitrate-vulnerable zone (Nitrates Directive) [

24], mostly due to intensive agricultural activities, particularly related to the growth of wheat, cotton and corn. Irrigation accounts for 94% of total water usage according to the Hellenic Ministry for the Environment, Energy and Climate Change-Special Secretariat for Water [

25]. Since groundwater currently supplies more than 65% of the region's total water usage, groundwater is crucial to the region's sustainability [

20]. Two of the twenty-seven groundwater bodies recognized in the PRB, covering 2,184 km

2, have been classified as having “bad” quality, while nine are recorded to have “bad” quantity status according to the most recent regional water management plan [

26]. In addition, three reservoirs operate in the area contributing to a lower extent as irrigation sources (

Figure 1). Specifically, “Girtoni” reservoir is located in the Northeastern part of the basin, “Karla” is the reservoir in subbasin 41 in the southeastern part (

Figure 1) and “Smokovo” is the reservoir in the south. These three reservoirs irrigate approximately 13,500 ha, 7,600 ha and 11,500 ha respectively. Additionally, 9,600 ha of cropland in the southwestern part of the basin (subbasins 39, 43, 47) are irrigated by an outside source, 'Plastiras' lake, as shown in

Figure 1.

2.2. SWAT Model Description

SWAT was developed by the US Department of Agriculture in collaboration with Texas A&M University [

27] for use in complex agricultural landscapes. It is a semi-distributed, process-based small watershed-to-river basin-scale model used for the simulation of hydrologic, sediment, and nutrient processes as well as crop growth, management practices, and land use changes in a watershed by using the water balance approach [

28]. The watershed in the GIS-based SWAT is divided into subbasins and one reach is associated with each subbasin. The subbasins are then divided into Hydrologic Response Units (HRUs), which represent a unique combination of land use, soil type and topography.

Runoff and loadings such as nutrients, sediments and pollutants transported by runoff are calculated separately in each HRU and then summed together to define the total loadings from the subbasin. Crop growth is also modeled at the HRU scale. Water balance is the driving force behind water quality processes and crop growth rates occurring in the basin, including the simulation of surface runoff/infiltration, evapotranspiration, lateral flow, percolation, and return flow. Surface runoff is estimated at the HRU level by using a modification of the Soil Conservation Service (SCS) Curve Number (CN) method [

29]. Groundwater aquifers are separated in SWAT into two systems: a shallow unconfined aquifer, which governs the amount of return flow to streams and a deep confined aquifer, which does not contribute to return flow, but can act as a source or sink. The soil erosion caused by rainfall is calculated by the Modified Universal Soil Loss Equation (MUSLE) [

30], which is a modified version of the Universal Soil Loss Equation (USLE) developed by Wischmeier and Smith [

31].

The crop growth component of SWAT is a simplified version of the Erosion Productivity Impact Calculator (EPIC) model, which is capable of simulating a wide range of crop rotation, pastureland, and trees. Agricultural management practices are defined in SWAT by specific management operations [

12,

29,

32] affecting every cropping and livestock system, including bioenergy crops [

33,

34], by defining planting, harvesting, tillage passes, irrigation, grazing, nutrient and pesticide applications. In order to simulate the PRB the latest available ArcSWAT 2012 version; Release 687 compatible with ArcGIS 10.8.2 was implemented.

2.3. SWAT Pinios Model

A terrain layer was inserted to start the modeling setup for the PRB. An available 25x25 Digital Elevation Model (DEM) for the study area [

12] was used to delineate the study area of PRB, covering a large part of the River Basin District of Thessaly in central Greece (

Figure 1). The area of the basin delineated was 10,623 km

2 covering roughly 75% of the Thessaly region. The elevation ranges significantly in this region with maximum values around 2,000 m near the borders of the basin. The basin was then divided into 61 subbasins based on the natural hydrologic pathways defined by the surface topography. For the stream delineation, a 10,000 ha upstream drainage area was decided (1% of the total basin’s area), defining the minimum drainage area required to form the origin of a stream. The river locations with accessible measured flows, the meteorological stations of the area and the existing dam locations were also taken into account in the definition of subbasins.

A land cover layer derived from Corine (CLC) 2012 [

35] was used in the modeling. The use of the 2012 land use map until nowadays was allowed by a direct comparison with CLC 2018 which showed insignificant changes of landcover types in PRB, but also by comparing the current crop patterns in the agricultural land with those of previous decades. So, both recent and older crop allocation data from the Hellenic Statistical Authority were analyzed and confirmed the rather stable crop types and irrigated land in PRB in the last two decades [

21]. In the final land use layer for SWAT only crops covering a significant area (>1% of the total agricultural land) were considered. Specifically, the 10 land use classes included in the final map were: pasture, forested areas, wetlands, urban lands, orchard trees, fallow areas, wheat, corn, cotton and alfalfa cultivations.

Table 1 presents the basin's area assigned to crops that was considered representative from 2010 and onwards in PRB. Corn was the most resource-demanding crop in this study, receiving 630 mm of irrigation water and 364 kg N/ha annually. In addition, cotton was fertilized with 185 kg N/ha and was irrigated with 420 mm every year. Wheat, which occupied the largest area, as a non-irrigated crop, received 169 kg N/ha. Lastly, alfalfa, as a perennial crop with significant irrigation water consumption, needed >600 mm of irrigation water annually, while its fertilization did not include N inputs.

The soil map of PRB was produced with data obtained from the European Soil Database (ESDB) [

36,

37].

Table 2 presents some of the soil parameters required by SWAT and the corresponding parameters of the datasets based on ESDB. From the ESDB shapefile, the polygons located in the PRB were extracted, resulting in a shapefile with 19 different soil types. All these 19 soils had two layers with the first layer being always of 300 mm depth. Most of the soils belonged to the hydrologic category B, having moderate infiltration rates and water capacities. Specifically, among the most important parameters used by SWAT, the available water capacities of the soils ranged between 0,14-0,17 mm water/mm soil and the saturated hydraulic conductivities ranged between 9,98-21,69 mm/hr.

The study area was divided into two slope classes. Higher sloped land was considered more erosive and therefore, for the needs of this study, a threshold to distinguish it from lowland was required. From the initial model executions and simulated erosion rates per HRU, the threshold of 1.5% was considered as critical for significant erosion occurrence. A similar approach has been followed in another published study with the critical threshold being 2%, very close to our selection [

17]. The above layers of land use, soils and slope classes were overlayed, creating 1850 HRUs. The average HRU area in PRB was 5.7 km

2.

Additional pressures of N in the basin were added by livestock. The parameterization of the model took into consideration the recent reported numbers from the Hellenic Statistical Authority [

38]. These are: 108,363 cattle, 1,410,538 sheep and 936,838 poultry during the years 2011 to 2021. These numbers corresponded to the three distinctive regions where livestock operations occurred: Prefectures of Larisa, Trikala, and Karditsa and animals were spatially allocated during the setup of the model to match the respective number for each district. The pressures of livestock activity were assessed based on the total number of animals within each subarea and the types of manure associated with each animal category [

29]. Grazing in the region occurred from April to October for cattle and goats, whereas during the remaining wet months of the year, it was assumed that animals were confined to indoor or restricted open spaces with manure being collected into manure heaps and then deposited onto grassland areas on a regular weekly basis. Grazing and manure deposition in the model was simulated in pastureland. Due to insufficient data regarding the poultry in PRB, a unified approach was adopted, involving weekly spreading of poultry manure across grassland areas (pastures) for the entire number of poultry in the basin (both domestic and those raised in organized poultry farms) throughout the year.

Finally, nitrogen (N) pressures from the waste water treatment installations (WWTPs) of the two biggest cities within PRB, ‘Larisa’ and ‘Trikala’, were added to the model as point source discharges to rivers. Data were collected from the official website of the Ministry of Environment and Energy [

39], as well as from the approved River Basin Management Plans of the 1st Revision, and specifically from the detailed documentation text of the analysis of anthropogenic pressures and their impacts on surface and groundwater systems of the Thessaly Water District [

40]. In Larisa, the calculated daily N load was 175.2 kg, corresponding to 63,948 kg N/ year, whereas in Trikala the respective loads were 104.5 kg N/day or 38,142.5 kg N/year.

2.4. Hydrological Evaluation of the Pinios River Basin Model

Our SWAT PRB model was developed with meteorological data for 8 years (2016-2023). River flow measured data were also accessible from the automatic monitoring network of hydrological stations of the Inland Water Department of the Hellenic Centre for Marine Research (HCMR) for almost the same period [

41]. Flow data from the station 'Tempi' near the outlet of PRB (

Figure 1) was used for evaluating flow simulations. A warm-up period of two years was also considered necessary with this rather short simulation period in order to eliminate the initial uncertainties [

42]. To deal with the problem of flow data limitations and accelerate the hydrological baseline representation with SWAT, we took advantage of the detailed previous studies conducted with SWAT for the same study area [

12,

43]. Even with small differences in land use types and crop growth schedules, transferring some parameters to a new model of the same area was considered realistic for simulating hydrology. Therefore, the default values of certain parameters related mostly to soil and groundwater modules of SWAT were modified by adopting the respective well calibrated parameters of the previous studies, which have evaluated simulated flows in a Pinios river location upstream the 'Tempi' station but also in several other nested subbasins within the model domain. Therefore, the parameter values used for hydrology in the present study were quite representative of a reliable simulation of monthly river flows on a multi-site basis, as recommended to achieve the required model performance efficiency all across the landscape [

44]. The statistical results produced from the comparison of past measured flows with the respective simulations were sufficient [

12], with Nash Sutcliffe Efficiencies (NSE) and coefficients of Determination (R

2) being close to “1”, quite above the minimum thresholds required for satisfactory performances [

45]. The final parameter values used in the present SWAT modelling study were thus based on the reported optimum values and some small further adjustments carried out in the present work (

Table 3) with the purpose to optimize the convergence of simulated monthly flows at 'Tempi' station with the recent available measured ones. Special attention was given to the parameters related to groundwater due to their important sensitivity [

46].

It should be noted that the zero values selected for the last parameter of

Table 3 had a critical role in PRB modelling. The parameter represented the initial water content in the shallow aquifers of the basin with significant values of it allowing groundwater exploitation regardless of the magnitude of natural recharge occurring. In PRB however, groundwater has been overexploited over the years. As a result, pumping from permanent reserves that are usually found at high depths is not economically and technically feasible nowadays. To allow the model to exploit only the renewable groundwater reserves, namely the water resources that entered each year the aquifers, and in this way mimic the actual situation across the intensively irrigated cropland of PRB, a zero value for the parameter was assigned to all HRUs at the beginning of simulation (1/1/2016).

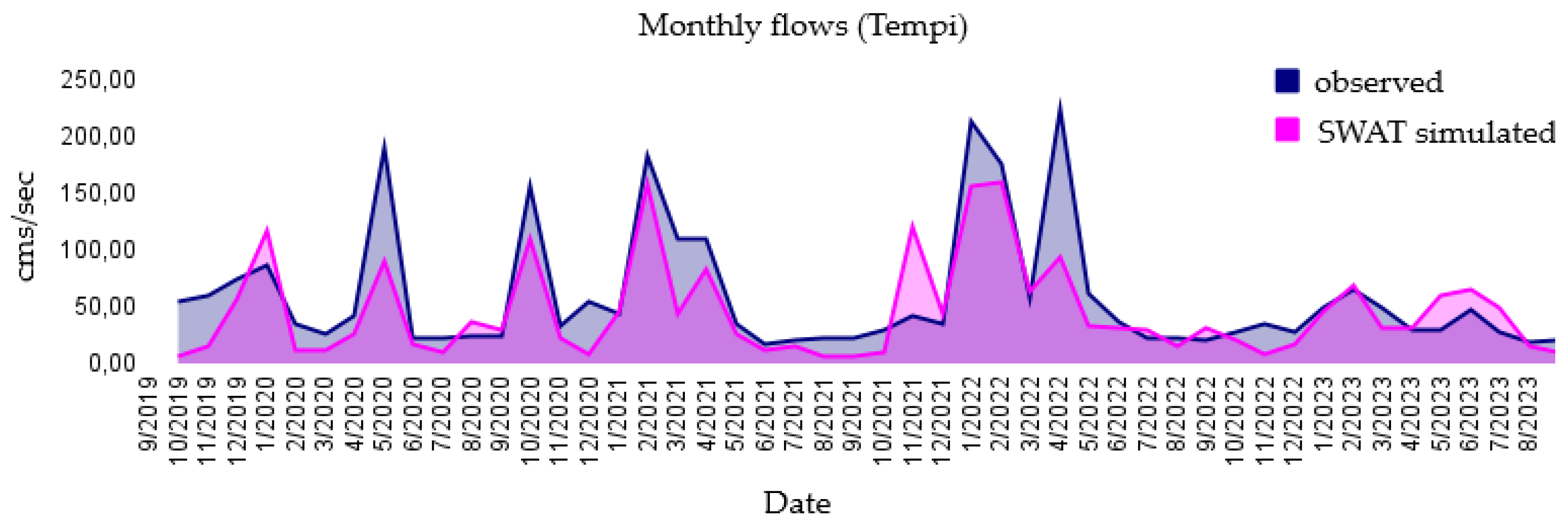

The hydrological performance of the model in the recent period of 2016-2023, with available discharge data from HCMR is shown in

Figure 2 below. The Figure depicts the comparison of simulated versus observed river flows at the flow station “Tempi”, near the outlet of the basin (

Figure 1). The available observed data covered a period of almost 4 years (2019 to 2023), with a few other stations having much less data available, not allowing a reliable comparison. The accuracy of simulation was measured with the use of NSE and R

2, which were calculated as 0.59 and 0.65 respectively.

2.5. Water Quality Evaluation of the Pinios River Basin Model

Due to insufficient observed river loads of nitrates-nitrogen (N-NO

3) or total nitrogen (TN) for conducting a detailed comparison with simulated loads, we adjusted a few empirical parameters. In

Table 4 the most important calibrated parameters with their final values are shown. The very sensitive N percolation coefficient (NPERCO) was adjusted at the entire basin level based on data found in the literature in order to depict a more realistic to the Greek conditions simulated value [

47]. Moreover, the parameters CDN and SDNCO, which governed soil denitrification, were adjusted to achieve a reasonable simulated denitrification rate. The adjustment was based mainly on the annual N fertilization rate in crop areas and was terminated when simulated denitrification from soil was within 10-20% of N fertilization [

29].

The river water quality observations related to N species were acquired by the national monitoring program for the implementation of the WFD in Greece conducted by HCMR [

48]. These observed data were comprised of scarce samples within the five-year period 2018-2022, covering evenly the wet (November – April) and the dry (May – September) periods. Due to the limited and irregular frequency of the grab samples for measuring N-NO

3 and TN, these specific measurements could not be compared with simulated data reliably. Therefore, the observed sparse-sampled concentrations were averaged across the wet and dry periods of each year and then compared to the respective simulated seasonal concentrations. In situations like this where a complete measured time series is unavailable, the data are insufficient for analysis using the recommended statistics mentioned in the hydrological evaluation section 2.4. Therefore, model outputs for N-NO

3 and TN were compared graphically with the observations to ensure that the calibrated outputs were within the range of seasonal nutrient levels in the river [

47].

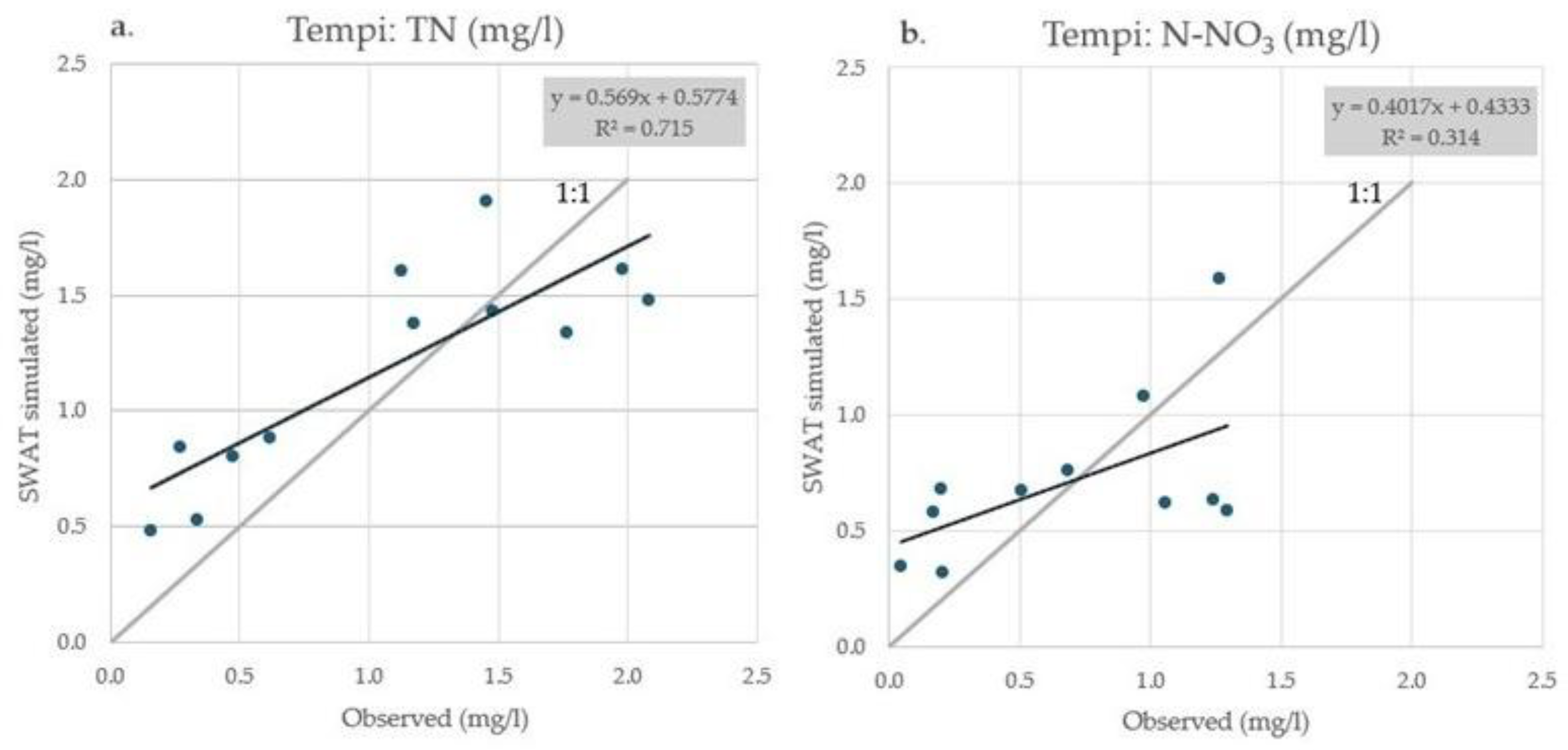

Figure 3 presents these graphic comparisons which allowed an adequate model evaluation for N species at large time steps.

Upon initial observation, scattergrams demonstrate a positive correlation and a comparable magnitude between observed and simulated seasonal concentrations. In

Figure 3a the simulated TN concentrations were either above or below the 1:1 line, indicating no systematic over- or under-estimation by the model on a seasonal basis. The N-NO

3 concentrations were slightly overestimated, but the data pairs were not far from the 1:1 line, suggesting that the model predicted a magnitude comparable to the observed data. The correlation coefficient for TN was 0.84 (R

2 = 0.71), indicating a strong positive correlation between the simulated and observed values (

Figure 3). The correlation coefficient for N-NO

3 was 0.56, (R

2 = 0.31), which was not as strong as that of TN. Nevertheless, even the current degree of coincidence between the seasonal observed and simulated values allowed a quite realistic aggregation of seasonal concentrations that led to reasonable estimation of TN and N-NO

3 river loads at large time steps (annual, mean annual). Specifically, the mean annual (2018-2022) observed TN and N-NO

3 concentrations were 1.37 and 0.89 with the respective simulated ones being 1.97 and 0.85.

2.6. Plant Growth Evaluation

Additionally, the simulated crop yields of all the four conventional crops of the area served as evaluation indicators for this study. In order to accurately simulate crops' growth, several plant parameters were adjusted slightly in the SWAT plant database according to local knowledge and the convergence of the simulated yields with reported ones.

Table 5 summarizes the adjusted parameters and their final values for each land cover type.

The simulated mean annual yields were compared with observed and reported values provided by the Hellenic Statistical Authority [

21] and the comparison proved that with the above crop parameter values the model simulated the annual productions of the cultivated crops with acceptable deviations. Specifically, the simulated values for corn, cotton, alfalfa and wheat were 11.45 t/ha, 3.11 t/ha, 12.38 t/ha and 3.84 t/ha with their respective observed production yields being 12.24 t/ha, 3.45 t/ha, 11.88 t/ha and 3.64 t/ha. Upon further analysis of the available observed data, it was determined that the simulated spatial variability of the produced yields was also reasonable.

2.7. Baseline Simulation

The validated PRB model produced the baseline results with respect to hydrology, water quality and crop production with reference to the period 2018-2023 (the first two years 2016 and 2017 were disregarded as warm up years). As explained above, the initial groundwater tables at the beginning of the simulation were set equal to zero in order to simulate only the exploitation of the renewable groundwater reserves for irrigation. This representation was considered realistic due to the overexploitation of groundwater in the past decades and the resulting decrease in the level of groundwater tables at rather inaccessible levels.

The average annual surface runoff at the entire basin level was calculated at 96 mm. The average annual evapotranspiration for the basin was estimated at 447.3 mm for the same period, with a total rainfall of 700 mm. The areas where the annual abstractions covered fully or partly the needs of the crops were also detected. The irrigation deficit varied across the basin with a maximum at 90% but with the irrigated HRUs that met a severe water scarcity of ≥50%, covering a rather small part of the irrigated land. In the baseline, during the period of 2018-2023, the total amount of water consumption per year for irrigation was roughly equal to 680 × 10

6 m

3. Irrigation from shallow aquifers was the main source of irrigation in the region, as 79% of the total arable land, without including fallow land, was irrigated by this source. The remaining 21% was irrigated by surface water including the three reservoirs located within the basin (

Figure 1) and an outside source, “Plastiras lake”, which satisfied the irrigation needs of approximately 10,000 ha of cropland in the southwestern part of the basin. In order to examine the extent of groundwater exploitation, the amount of water stored in shallow aquifers at the end of the simulation period (SWAT parameter SA_ST) was used. In the most intensively managed areas, the groundwater content at the simulation end varied between 0–200 mm.

Regarding water quality, the analysis of the baseline results has shown that the area is indeed sensitive to N-NO

3 pollution, as its concentration exceeded the threshold of 0.6 mg/l, which, according to the Greek classification system for rivers [

49], has been set as the upper limit of the “good” physicochemical status of water bodies. Specifically, the simulated mean annual N-NO

3 concentration at the basin outlet was 1.68 mg/l. In addition, the mean annual TN loss from the entire land of PRB to its surface waters was calculated at 4.65 kg/ha. In groundwater, N-NO

3 pollution was caused by the accumulation of nitrates, which in some cases reached levels that are prohibitive for the use of water for water supply purposes. Concentrations of N-NO

3 leaching, used as a pollution indicator in this work, were directly or indirectly governed by several N-NO

3 pathways such as the N applied with fertilizers in the topsoil, the N uptake of different crops as well as the N that was transported directly to streams. The average annual N-NO

3 leached concentration in the basin was calculated at 21.2 mg/l.

2.8. Bioenergy Crop Simulation

In this study, the implementation of the perennial bioenergy crop, switchgrass, in PRB was examined through three what-if scenarios. The developed scenarios are listed in

Table 6 together with the baseline scenario which was used for comparison purposes.

Sloping land was taken into consideration for switchgrass implementation separately because grasses and perennial vegetation with persistent roots have theoretically the capacity to adapt to these areas of potentially lower productivity and it would be thus of interest to compare the results produced there with those in non-sloping areas. The term “sloping land” refers to areas of land that are not generally considered very well-suited for intensive agricultural use due to land slope that limits the use of machinery, and several practices compared to the lowland areas. These areas may also be subject to soil degradation due to increased soil erosion that causes loss of valuable topsoil and are usually described as erosive, droughty and nutrient poor, which may lead to reduced productivity [

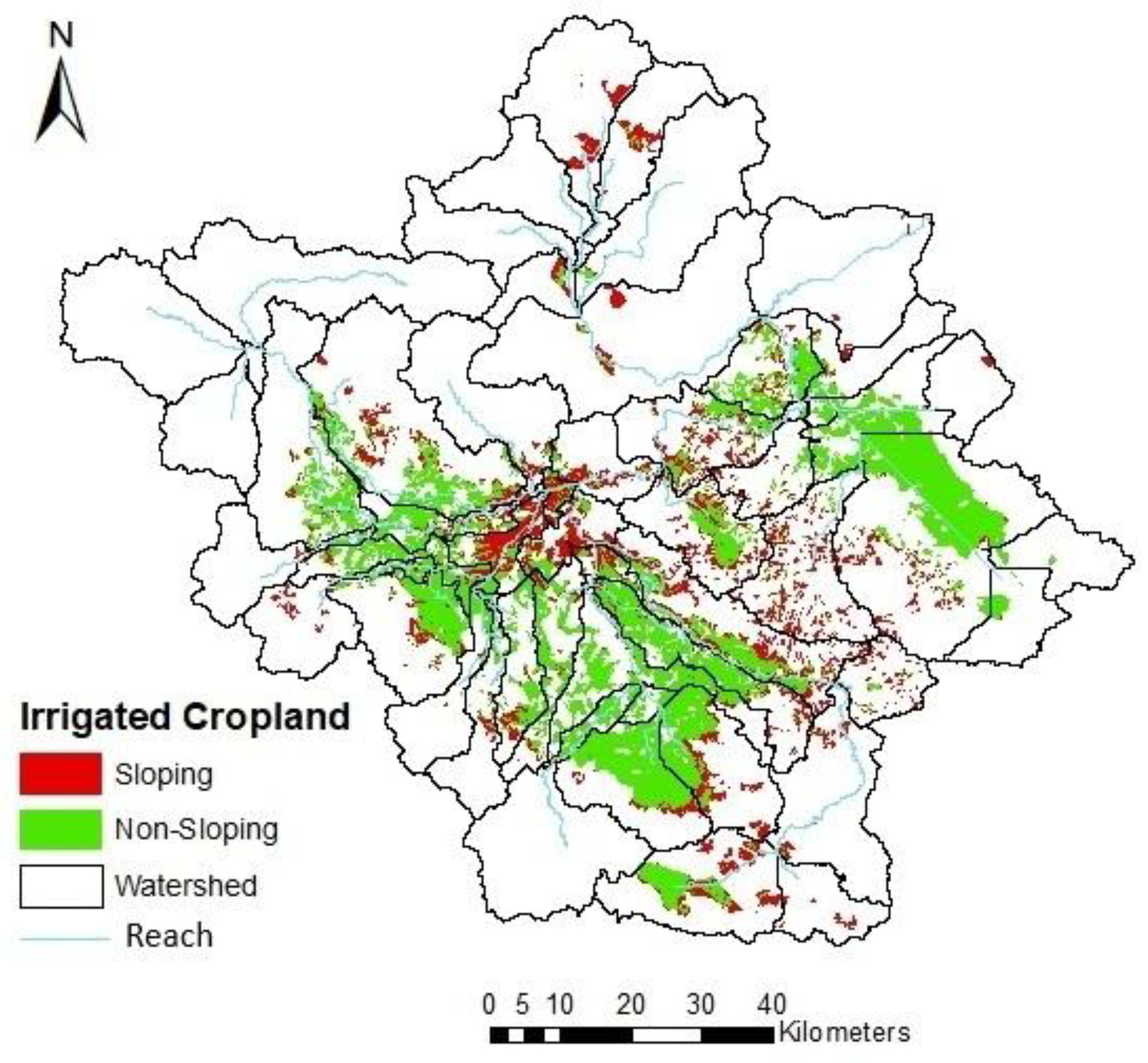

17]. In the PRB model of the present study, as sloping lands, the crop areas with slopes >1.5% were considered based on the definition of HRUs. Moreover, it was chosen not to extend switchgrass implementation scenarios in pastureland or semi-forested regions, but only to the irrigated cropland (sloping, non-sloping) areas. Non-irrigated cropland was not candidate for switchgrass installation as no additional water pressure from switchgrass irrigation, would be realistic in the water scarce PRB.

Figure 4 illustrates the sloping and the non-sloping irrigated cropland areas of PRB on HRU level. Sloping irrigated cropland (presented with the red color in the map) represented 5.8% of the whole basin. Specifically, 219 out of 1,850 HRUs represented the sloping irrigated cropland of PRB, accounting for 30% of the irrigated cropland. The remaining 70% represented the non-sloping irrigated cropland (illustrated with the green color in the map of

Figure 4). In numbers, from the 202,692 ha of the total irrigated cropland, 61,156 ha represented the irrigated sloping cropland and 141,537 ha the irrigated non-sloping cropland as presented in

Table 7.

None of the developed scenarios can be considered as very realistic mostly due to the extensive implementation of the bioenergy crop in the sloping and non-sloping irrigated landscapes or the total irrigated land. However, our focus in developing these initial scenarios was to test the behavior of our PRB model across a large variety of land with switchgrass established and explore the potential effects on water under big changes to the existing irrigated cropping system.

To simulate the crop closely to the Greek conditions several plant parameters were adjusted in the SWAT plant database according to the recommendations of experts from the University of Thessaly and their relevant published works [

50,

51]. The parameters as well as their final adjusted values are presented in

Table 8.

Switchgrass was simulated with its sowing date in May of the first year of simulation (2016) and its harvest and kill operation in October of the last year of simulation (2023), with annual harvests in all intermediate years [

51]. The results produced from its growth refer to the last 6 years (2018-2023) of the simulation period due to the 2-y warm up period that was neglected. The irrigation amount applied annually during the dry period (May-September) was 250 mm [

51]. Only N fertilization was considered in this study since switchgrass requirements for P are minimal, with P application being only necessary in cases of significant soil deficiency [

52]. The usual N fertilization rate for Greek conditions ranged between 80 and 160 kg per ha and was considered adequate to satisfy the plant needs resulting in a satisfactory amount of produced biomass [

50]. In this study, 150 kg N per ha during each year was applied with an additional 30 kg of N per ha right after seeding. For harvesting switchgrass, the one cut system was selected as the optimal one for the study area.

In all the developed scenarios switchgrass replaced all the irrigated crops existing in the respective land of each scenario, namely cotton, corn and alfalfa. When cotton was replaced by switchgrass, almost 20% less N was applied to the respective HRUs, while there were no P applications. Moreover, this replacement resulted in 40% less irrigation water used (if groundwater availability allowed optimum irrigation). Similarly, when corn was replaced, there was a 59% reduction in the N applied with fertilization and a 60% theoretical reduction in the water consumed for irrigation. On the other hand, only when alfalfa was replaced by switchgrass, the amounts of applied N increased (alfalfa did not receive N at all) but there was a significant theoretical reduction of 58% in the irrigation water applied.

3. Results

The three manual scenarios were tested one by one in the Pinios river basin. The baseline scenario that simulated the 8-year period from 2016 to 2023 by providing results for the 6-y period of 2018-2023 due to the first 2-y warm up period, was used as a test bed for evaluating these alternative switchgrass implementation scenarios. The results of the baseline scenario (scenario 1) proved that the study area was vulnerable to N-NO

3. The mean annual effects of all the four scenarios on surface runoff, ET, groundwater content, total irrigation, N-NO

3 loads, N-leached concentrations and switchgrass biomass production at the entire basin scale were calculated and are listed in

Table 9.

3.1. Results on Hydrology

Switchgrass as a perennial crop with significantly high biomass production had increased evapotranspiration values compared to other crops. Specifically, a 2.2%, a 1% and a 1.5% increase in the mean annual baseline ET (461 mm) of the entire basin was observed in the second, third and fourth scenarios respectively, compared to the first scenario. The effect was much more pronounced at the HRU level with ET increases up to 10% on an annual basis where cotton was the baseline crop. The average increase in the HRUs where corn was replaced by switchgrass was almost 2.5%, while alfalfa replacement by switchgrass resulted to almost the same ET values as both were perennial crops with similar simulated biomass yields.

Surface runoff in the switchgrass implementation scenarios was expected to be reduced compared to the baseline mean annual 157 mm that were simulated at the entire basin level. As presented in

Table 9, a mean annual reduction of 15%, 4% and 11% occurred in the second, third and fourth scenarios respectively.

Figure 5 illustrates the effect of switchgrass installation on the groundwater content of the basin.

Figure 5a represents the first scenario (baseline), while

Figure 5b depicts the impact of switchgrass implementation in the second scenario with switchgrass simulated in the entire irrigated land. The data used for the creation of the Figure maps represent the values simulated by SWAT at the last day of simulation (31/12/2023) allowing the assessment of the long-term effect of switchgrass on groundwater exploitation. Thus, the map on the left, referring to the first scenario, presents the groundwater content in mm at the end of 2023, while the map on the right depicts the groundwater increase (in mm) per subbasin from the baseline caused by the second scenario (switchgrass in all irrigated cropland).

As can be observed in

Figure 5 switchgrass resulted in significant increases of the groundwater content with almost half of the PRB area gaining >60 mm (or 600 m

3/ha) of water in the aquifers when switchgrass replaced the more water-demanding conventional crops. The majority of the subbasins present an increase of water stored in the shallow aquifers. The average increase observed among the subbasins was 68 mm while 22 out of the 61 subbasins met >50% increases of groundwater content from the baseline. As shown by the results on

Table 9, the total effect of switchgrass implementation scenarios on the groundwater amounts stored in the aquifers of the entire PRB at the end of the simulation was positive in all cases. Specifically, the 5.61 billion m

3 of stored groundwater at the end of the simulation period in scenario 1 were increased by 10%, 4% and 5% under scenarios No. 2, 3 and 4 respectively.

The irrigation water abstracted from the shallow aquifer with switchgrass implementation was considerably reduced as well. As stated in section 2.8, according to the theoretical irrigation water needs of the crops, 40%, 60% and 58% less water consumption was expected by replacing cotton, corn and alfalfa with switchgrass respectively. According to the results of

Table 9, the total 680 hm

3 of water that was actually abstracted from the shallow aquifers of PRB for irrigation purposes on a mean annual basis in the baseline, was reduced by 40%, 10% and 28% from the implementation of the second, third and fourth scenarios respectively. Obviously, these numbers resulted from the extent of the irrigated areas and irrigated conventional crops that were replaced by switchgrass in each scenario.

3.2. Results on Water Quality

The impacts on N-NO

3 were quite positive too, with predicted N-NO

3 loss reductions being quite or very significant on the entire basin level, depending on the extent of the perennial crop installation.

Figure 6 illustrates the effect of the N-NO

3 loss of the basin in the first (6a) and second scenario (6b). The data used for creating the maps represent the average year for each scenario, calculated from the model’s output data for the 6-year period of interest (2018-2023).

It is evident that there was an important effect in reducing N-NO

3 under switchgrass implementation in parts of PRB's cropland. Specifically, the average percentage reduction observed in the HRUs of the most lowland areas of the Thessaly plain, covering the central part of the basin, was 80%, with the reduction in certain HRUs approaching 95%. As can be observed in

Figure 6, in the central, southern and western parts of PRB N-NO

3 annual loads in many irrigated areas were reduced at the levels of <0.3 kg/ha, with the respective baseline values being greater than 1 kg/ha. The maximum N-NO

3 annual HRU load simulated in the first, baseline scenario, was 19.8 kg/ha whereas in the second, extensive switchgrass implementation scenario, the corresponding value was reduced to 11.1 kg/ha. The mean annual N-NO

3 loads on the entire basin level were calculated for all switchgrass scenarios (

Table 9) and precisely, from the mean annual 1.48 kg of lost N-NO

3 per ha of PRB land to streams, an 18%, a 7% and similarly a 7% reduction were simulated from the second, the third and the fourth implementation scenarios respectively.

Another important output is the mean annual N-NO

3 leached concentrations of the baseline and the three switchgrass scenarios, included in

Table 9 as well. From the calculated mean concentrations at the basin level, a 44%, a 23% and a 25% reduction of the baseline N-NO

3 leached concentration of 21.2 mg/L was predicted on a mean annual basis in the second, third and fourth scenarios respectively.

3.3. Results on Switchgrass Biomass Production

Figure 7 illustrates the mean annual biomass production of switchgrass under the second simulated scenario with switchgrass implemented in the entire irrigated land. The presented map was created by using the simulated mean annual (2018-2023) data on switchgrass biomass production.

The simulated production of switchgrass, both mean annual (2018-2023) and averaged in space, was calculated at 18.6 t/ha (

Table 9), with the maximum biomass simulated for a single HRU being 22 t/ha. Published data on actual switchgrass growth within the study area [

50] reported a typical range from 15 t/ha to 20 t/ha of biomass production on an annual basis. According to this evidence, simulated biomass yields that belong to the first class of the map of

Figure 7 (<12 t/ha/y) were considered very low, these of the second (12-15 t/ha/y) and third (15-20 t/ha/y) classes were rather low and normal respectively, and the rest (>20 t/ha/y) were near optimum. It is remarkable that, according to the last row of

Table 9, in the third scenario, when switchgrass was only implemented in the sloping irrigated land, its mean annual biomass production was simulated equal to 18.2 t/ha, while in the fourth scenario (only in non-sloping cropland) it was just a little higher and equal to 18.4 t/ha. These almost identical production levels per unit area have shown that, in our model, growing switchgrass on milder topography had similar production levels with growing it on steeper areas. Thus, the selection of sloping areas was not a limiting factor for biomass production.

4. Discussion

The PRB SWAT model developed in this study simulated realistically the hydrological and N cycle processes occurring at the river basin scale. This is the case with crop yields and switchgrass biomass production in particular, as well as with switchgrass impact on water quality and quantity for which it was essential to rely on other research studies to compare our model predictions. The reduction in surface runoff caused by switchgrass implementation was the combined effect of: a) the more dense land coverage that characterizes most perennial crops compared to annual crops resulting in surface runoff reductions [

53], b) the reduced amount of water that switchgrass received with its irrigation applications that also resulted to the production of less water capable of becoming runoff and c) the slightly increased ET, leaving a reduced water amount to be lost via runoff [

54].

As has been stated, switchgrass received notably less irrigation water compared to the existing irrigated crops in the PRB, which led to the assumption that its adoption could increase groundwater reserves. Indeed, apart from the reduced direct water abstractions, in the majority of HRUs switchgrass could reduce surface runoff and increase soil water content and percolation, the water that moves below the root zone over time [

55]. While this was a fair observation for the entire basin level there were certain HRUs where the opposite was observed due to less water applied on the topsoil via irrigation. Overall, despite the fact that the areas that were available for switchgrass installation covered small percentages of the entire basin (19% of the basin represented the total irrigated cropland, 5.8% was the sloping irrigated cropland and 13.2% the non-sloping irrigated cropland), the individual effects in the subbasins were anything but trivial as they proved to have the potential to improve considerably water availability because of the reduced abstractions.

Regarding the total irrigation water used in PRB, as expected, the effect of the fourth scenario (switchgrass in non-sloping irrigated cropland) was greater than the effect of the third one (sloping irrigated cropland), and this difference was attributed to the significantly more area of non-sloping irrigated land that was available for switchgrass installation in the fourth scenario. This resulted in the replacement of more crops with greater irrigation water needs. Based on all these results concerning the hydrology of the area in all the developed scenarios, it can be concluded that the perennial crop could be effective in alleviating high-water abstractions from the shallow aquifers of PRB and in this manner enhancing their water balance.

The agricultural use of N fertilizers has been a major contributor to N exports to waters from agricultural areas. Specifically, in PRB that is highly vulnerable to N-NO

3 pollution, N-NO

3 reduction was considered of great importance. The trend in N loss reduction was correlated with N transported in dissolved forms via runoff (mainly N-NO

3). In general, the decrease in N-NO

3 loadings was mainly because switchgrass required lower N fertilizer inputs in comparison to baseline crops. The model simulations indicated that biofuel crop adoption could reduce N losses compared to current cropping systems used in PRB as observed in other studies as well [

17,

19,

56,

57]. The level of reduction varied between scenarios, with the areal extent of deployment of the bioenergy crop being the key factor for the greatest reduction caused by the second scenario (all irrigated crops replaced by switchgrass). However, the third and the fourth scenarios had the same overall effect at the basin level resulting to average N-NO

3 loss rates of 1.37 and 1.38 kg/ha, even though a lower rate would be expected in the fourth scenario with switchgrass implemented in the double area than in the third scenario. The almost identical N-NO

3 reduction is obviously attributed to the greatest effect of the perennial crop in sloping areas where increased runoff reduction led to a more pronounced N-NO

3 reduction as well. The rather low N-NO

3 percentage reduction of 7% (1.37 and 1.38 from 1.48 kg./ha as shown in

Table 9) was considerable for both scenarios, since conventional crops replacement represented a small percentage of land cover change in the entire basin (5.8% for the sloping irrigated cropland scenario and 13% for the non-sloping irrigated cropland scenario) and additionally, in both scenarios there were extensive areas of non-irrigated wheat, not replaced by switchgrass, that still contributed greatly to N pollution (wheat HRUs contributed 47% of the total N-NO

3 pollution from the cropland in the first, baseline scenario). So, even though the effect was not as significant in the entire basin level as in the irrigated HRUs, if the perennial crop was planned to be installed in the entire sloping cropland (irrigated and non-irrigated), N-NO

3 could be reduced substantially, leading probably to impressive water quality improvements.

Nitrate pollution in PRB had anthropogenic activities as main sources, mostly crops cultivation and secondly, livestock farming. In groundwater, nitrate pollution is generally caused from the accumulation of nitrates, which in some cases can reach levels that are prohibitive for the use of water for water supply purposes. This means that the magnitude of N-NO

3 leaching is directly or indirectly governed by N fertilization, N crop uptake and N lost from soils that is transported to streams. Additionally, the increased concentration of leaching nitrates can be attributed to high irrigation rates in these areas [

58,

59]. Thus, the reduced leached N-NO

3 concentrations from switchgrass implementation were expected as the perennial crop could reduce significantly N-NO

3 leaching from the agricultural lands of our study area due to its lower irrigation and N fertilization needs.

One limitation of SWAT in the simulation of crop growth is the inability to account for crop diseases in specific areas and years that may have led to relatively higher simulated yields in certain years than those reported. Hence, it is always preferred to discuss simulated average annual yields, and this was the case with switchgrass biomass production simulated under scenarios. By calculating biomass yields only in sloping areas, it can be concluded that some of the highest yields occurred there. Evidently, switchgrass had a great potential to grow in these areas. The average biomass production calculated in the sloping-land scenario was 18.2 t/ha and the maximum production observed in a single HRU was 22 t/ha. The areas where inadequate productions (less than 12 t/ha) were observed (

Figure 7) could be related to irrigation water deficits in these areas. In the center of the basin where the main part of the Thessaly plain (lowland areas) is located, there were constant biomass production yields of less than 15 t/ha (

Figure 7). This can be also attributed to the insufficient groundwater content of the aquifers in this subregion due to the lower precipitation levels in this area that has subsequently led to less percolation and aquifer recharge compared to other areas in the western parts of the basin. The deficit irrigation observed proved further that irrigation water was the main limiting parameter for switchgrass crop growth as it has been also stated by Giannoulis et al. [

60] for this particular subregion of PRB. It should be also noticed that all irrigated areas served by reservoirs in this study had no problems of irrigation water shortage. A representative example of the positive role of reservoirs in meeting irrigation water needs in PRB is the large area irrigated by the Karla reservoir in the most eastern part where, despite the low precipitation and groundwater recharge, switchgrass biomass production reached its maximum values of >20 t/ha/y (

Figure 7).

Concerning the conventional irrigated crops in the PRB, their spatially averaged simulated yield rates per ha of cropland in the last two scenarios when only part of the irrigated land was replaced by switchgrass, did not practically changed from their average (per unit area) simulated yields at the baseline. However, an added benefit that was observed at the very local level under the partial replacement of irrigated conventional crops by switchgrass in the third and fourth scenarios was the increased availability of groundwater due to the reduced overall abstractions. Switchgrass implementation solely in sloping/non-sloping irrigated areas gave the potential to adjacent conventional crops in non-sloping/sloping areas that were irrigated inadequately before, to improve their production yields due to increased irrigation amounts applied from groundwater.

5. Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to provide estimates of the effects that switchgrass cultivation can have on water quantity and quality when implemented in large areas of a Greek agricultural basin, using SWAT. The developed scenarios had the purpose to explore upper limits of water quantity/quality impacts arising from the hypothetical wide adoption of a perennial bioenergy crop, as they were simulated for the first time in a Greek basin with the common Mediterranean hydrometeorological conditions. Switchgrass proved to have great potential of growing in sloping areas and producing sufficient amounts of biomass, even though these areas were expected to have relatively lower productivity due to their higher susceptibility in soil and nutrient loss.

The reduction of total nitrates loss from land to waters depended on the spatial extent of switchgrass implementation, which also had significantly positive effects on water quantity and quality at the very local level. Switchgrass was confirmed to be a low input crop in this study, increasing the groundwater content of several subbasins. The numerical results indicated that in such an extensively managed area, with N-NO3 pollution problems and high exploitation of water resources, switchgrass had the potential to serve as a mitigation measure to alleviate both these issues. Indeed, the study can support the progressive substitution of parts of the cropland with conventional crops with bioenergy crops, promoting it as an effective restoration measure for water bodies, according to the WFD requirements, that could be also adopted in the next phases of the regional WFD management plans.

Ongoing research activities can add value to the preliminary results presented in this paper. An economic analysis including the cultivation costs and benefits from crops may facilitate decision makers to take local socio-economic factors into consideration when selecting locations for bioenergy crops adoption within the basin. Cost numbers will be also associated with water quantity and quality impacts for various schemes of crops allocation across the landscape. The development of an efficient optimization tool to identify optimum solutions that can simultaneously satisfy economic (net farmers' income, bioenergy production) and environmental (water quantity and quality in rivers and groundwater) objectives at the basin scale is included in our ongoing research efforts. It is believed that the current study on switchgrass simulation with SWAT, along with the future directions constitute a useful approach to hydrologic, water quality and bioenergy crop simulation that can help decision makers and water managers incorporate bioenergy crops within their combined efforts towards renewable energy production and water protection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization M.S , L.K and Y.P.; methodology, M.S., L.K. K.G., and Y.P.; software, M.S, L.K., S.K. and H.G.; validation, M.S., L.K., S.K. H.G. and K.G.; formal analysis, M.S., L.K. and Y.P.; investigation, M.S., L.K., S.K., H.G. and E.D.; resources, M.S, L.K and Y.P.; data curation, M.S., L.K., K.G., E.D. and Y.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S. and L.K.; writing—review and editing, M.S., L.K., S.K., H.G., K.G., E.D. and Y.P.; visualization, M.S., L.K., S.K., H.G. and Y.P.; supervision, Y.P.; project administration, Y.P.; funding acquisition Y.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research study is carried out within the framework of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan Greece 2.0, funded by the European Union – NextGenerationEU (Implementation body: HFRI). More specifically: This research was supported under the Basic Research Financing Action “Horizontal support of all sciences”, Sub-action 1 (Project Number: 16425 and project title: BIOGRASS). https://greece20.gov.gr.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available from the authors of the paper upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive and insightful comments that helped us improve our article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

The appendix is an optional section that can contain details and data supplemental to the main text—for example, explanations of experimental details that would disrupt the flow of the main text but nonetheless remain crucial to understanding and reproducing the research shown; figures of replicates for experiments of which representative data is shown in the main text can be added here if brief, or as Supplementary data. Mathematical proofs of results not central to the paper can be added as an appendix.

Appendix B

All appendix sections must be cited in the main text. In the appendices, Figures, Tables, etc. should be labeled starting with “A”—e.g., Figure A1, Figure A2, etc.

References

- Claro, A.M.; Fonseca, A.; Fraga, H.; Santos, J.A. Future Agricultural Water Availability in Mediterranean Countries under Climate Change: A Systematic Review. Water 2024, 16, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, Y.; Karpouzos, D.; Georgiou, P.; Papamichail, D. Ecosystem Services Evaluation from Sustainable Water Management in Agriculture: An Example from An Intensely Irrigated Area in Central Greece. In Proceedings of the 7th International Electronic Conference on Water Sciences, online, 15-30 March 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamataris, D.; Tsavdaridou, AI.; Banti, D.; Malliaras, A.; Karalis, A.; Theocharis, N.; Michos, C.; Mazaris, A. Water-Ecosystems-Food nexus security achievement in the context of climate change: the case study of an agricultural Mediterranean Basin, Greece. Research Ideas and Outcomes 2023, 9, e116070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Girolamo, A.M.; Lo Porto, A. Source Apportionment of Nutrient Loads to a Mediterranean River and Potential Mitigation Measures. Water 2020, 12, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psomas, A.; Dagalaki, V.; Panagopoulos, Y.; Konsta, D.; Mimikou, M. Sustainable agricultural water management in Pinios river basin using remote sensing and hydrologic modeling. Procedia engineering 2016, 162, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellenic Ministry for the Environment, Energy and Climate Change- Special Secretariat for Water. Report on Directive 91/676/EEC - Nitrate pollution situation in the Greek territory (Reference period: 2020 - 2023). Available online at: https://wfdver.ypeka.gr/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/files/GR08/GR08_P26b_Perilipsi_En.pdf. Accessed on: 10/10/2024.

- Skoulou, V.; Mariolis, N.; Zanakis, G.; Zabaniotou, A. Sustainable management of energy crops for integrated biofuels and green energy production in Greece. Renewable and sustainable energy reviews 2011, 15, 1928–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukis, I.; Vassilakos, N.; Kontopoulos, G.; Karellas, S. Policy plan for the use of biomass and biofuels in Greece: Part I: Available biomass and methodology. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2009, 13, 971–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitkidis, G.; Magoutas, A.; Kitsios, F. Market and economic feasibility analysis for the implementation of 2nd generation biofuels in Greece. Energy Strategy Reviews 2018, 19, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoulis, K.; Bartzialis, D.; Skoufogianni, E.; Gravalos, I.; Xiradakis, P.; Danalatos, N. G. Panicum virgatum L. could be an alternative environmentally friendly feedstock for energy production. SSRG International Journal of Agriculture & Environmental Science (SSRG – IJAES). 2017; 4, 14–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Marek, G.W.; Marek, T.H.; Moorhead, J.E.; Heflin, K.R.; Brauer, D.K.; Gowda, P.H.; Srinivasan, R. Assessment of alternative agricultural land use options for extending the availability of the Ogallala Aquifer in the Northern High Plains of Texas. Hydrology 2018, 5, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, Y.; Makropoulos, C.; Gkiokas, A.; Kossida, M.; Evangelou, L.; Lourmas, G.; Michas, S.; Tsadilas, C.; Papageorgiou, S.; Perleros, V.; Drakopoulou, S.; Mimikou, M. Assessing the cost-effectiveness of irrigation water management practices in water stressed agricultural catchments: The case of Pinios. Agricultural water management 2014, 139, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First Revision of the Regional River Basin Management Plan (in Greek). Available online at: https://wfdver.ypeka.gr/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/EL08_SDLAP_APPROVED.pdf. Accessed on: 20/11/2024.

- Kharel, G.; Zhong, Y.; Will, R.E.; Zhang, T.; Zou, C. B. Potential Hydrological Impacts of Planting Switchgrass on Marginal Rangelands in South Central Great Plains. Water 2022, 14, 3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, E.; Saraswat, D.; Singh, G. Comparative analysis of bioenergy crop impacts on water quality using static and dynamic land use change modeling approach. Water 2020, 12, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Chaubey, I.; Cibin, R.; Engel, B.; Sudheer, K.P.; Volenec, J.; Omani, N. Perennial biomass production from marginal land in the Upper Mississippi River Basin. Land degradation & development 2018, 29, 1748–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, Y.; Gassman, P.W.; Kling, C.L.; Cibin, R.; Chaubey, I. Water quality assessment of large-scale bioenergy cropping scenarios for the upper Mississippi and Ohio-Tennessee river basins. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association 2017, 53, 1355–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibin, R.; Trybula, E.; Chaubey, I.; Brouder, S. M.; Volenec, J. J. Watershed-scale impacts of bioenergy crops on hydrology and water quality using improved SWAT model. Gcb Bioenergy 2015, 8, 837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassman, P.W.; Valcu-Lisman, A.M.; Kling, C.L.; Mickelson, S.K.; Panagopoulos, Y.; Cibin, R.; Chaubey, I.; Wolter, C. F.; Schilling, K.E. Assessment of bioenergy cropping scenarios for the Boone River watershed in north central Iowa, United States. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association 2017, 53, 1336–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisinaras, V.; Herrmann, F.; Panagopoulos, A.; Tziritis, E.; McNamara, I.; Wendland, F. Fully Distributed Water Balance Modelling in Large Agricultural Areas—The Pinios River Basin (Greece) Case Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellenic Statistical Authority, Data on crop areas, Available online at: https://www.statistics.gr/en/statistics/-/publication/SPG06/-. Accessed on: 21/12/2024.

- Arampatzis, G.; Panagopoulos, A.; Pisinaras, V.; Tziritis, E.; Wendland, F. Identifying potential effects of climate change on the development of water resources in Pinios River Basin, Central Greece. Applied water science 2018, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliades, L.; Loukas, A.; Liberis, N. A water balance derived drought index for Pinios River Basin, Greece. Water resources management 2011, 25, 1087–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitrates Directive - Vulnerable Zones Reporting 7 - Web map by Joint Research Centre of European Commission available online at: https://water.jrc.ec.europa.eu/portal/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=b33a220c1b284583851e93a245da02ef. Accessed on: 10/12/2024.

- Hellenic Ministry for the Environment, Energy and Climate Change-Special Secretariat for Water. Compilation of Management Plan for the River Basins of Thessaly Water District (GR08)-Management Plan; Athens, Greece, 2017; pp. 252. Available online at: https://wfdver.ypeka.gr/el/project/gr08-26b-approved-management-summaryen-gr/. Accessed on 15/11/2024.

- Second Revision of the Regional River Basin Management Plan (in Greek). Available online at: https://wfdver.ypeka.gr/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/EL08_2REV_sdlap.pdf. Accessed on: 25/11/2024.

- Williams, J.R.; Arnold, J.G.; Kiniry, J.R.; Gassman, P.W.; Green, C.H. History of model development at Temple, Texas. Hydrological sciences journal 2008, 53, 948–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloui, S.; Mazzoni, A.; Elomri, A.; Aouissi, J.; Boufekane, A.; Zghibi, A. A review of Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) studies of Mediterranean catchments: Applications, feasibility, and future directions. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 326, 116799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neitsch, S.L.; Arnold, J.G.; Kiniry, J.R.; Williams, J.R. Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) Theoretical Documentation. Blackland Research Center, Texas. 2009. Agricultural Experiment Station, Temple, Texas (BRC Report 02-05). Available online at: https://swat.tamu.edu/media/69296/swat-io-documentation-2012.pdf. Accessed on: 02/11/2024.

- Williams, J.R. Sediment-yield prediction with universal equation using runoff energy factor¹. In Present and Prospective Technology for Predicting Sediment Yield and Sources: In proceedings of the Sediment-Yield Workshop, USDA Sedimentation Laboratory, Oxford, Miss., U.S.A, 28-30 November 1972. Agricultural Research Service, US Department of Agriculture 1975, 40, 244. Available online: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e1/FEDLINK_-_United_States_Federal_Collection_%28IA_presentprospecti40sedi%29.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Wischmeier, W.H.; Smith, D.D. Predicting rainfall-erosion losses from cropland east of the Rocky Mountains. Agricultural Handbook, 1965, pp. 282.

- Arabi, M.; Frankenberger, J.R.; Engel, B.A.; Arnold, J.G. Representation of agricultural conservation practices with SWAT. Hydrological Processes: An International Journal 2008, 22, 3042–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trybula, E.M.; Cibin, R.; Burks, J.L.; Chaubey, I.; Brouder, S.M.; Volenec, J.J. Perennial rhizomatous grasses as bioenergy feedstock in SWAT: parameter development and model improvement. Gcb Bioenergy 2015, 7, 1185–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Wang, T.T.; Jin, S.H.A.O.; Sheng, G.U.O.; Wei, Z.H.U.; Yu, Y.J.; Chen, S.; Hatano, R. Modeling the biomass of energy crops: Descriptions, strengths and prospective. Journal of integrative agriculture 2017, 16, 1197–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corine Land Cover 2012 — European Environment Agency. Available online at: https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/external/corine-land-cover-2012. Accessed on: 15/11/2024.

- Hiederer, R. Mapping soil properties for Europe-spatial representation of soil database attributes. EUR26082EN scientific and technical research series. 2013, 47, 1831–9424. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=f0031d732307a43e9dca04e46b47dfc6d75a8be9 (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Hiederer, R. Mapping soil typologies—spatial decision support applied to European Soil Database. Publications Office of the European Union, 2013, pp. 127. Available online at: https://esdac.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ESDB_Archive/eusoils_docs/other/EUR25932EN.pdf. Accessed on: 21/11/2024.

- Hellenic Statistical Authority, Data on livestock, Available online at: https://www.statistics.gr/en/statistics/-/publication/SPK13/-, Accessed on: 05/12/2024.

- General Secretariat of Waste Management Coordination, Wastewater Treatment Control and Planning Department, Web map of the Urban Wastewater Treatment Plants. Available online at: https://astikalimata.ypeka.gr/wtp. Accessed on: 20/11/2024.

- First Revision of River Basin Management Plans, Detailed methodologies on anthropogenic pressures (in Greek). Available online at: https://wfdver.ypeka.gr/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Methodologia_Piesewn_v3.pdf. Accessed on: 04/11/2024.

- Inland Water Department of the Hellenic Centre for Marine Research (HCMR), Data on the automatic monitoring network of hydrological stations. Available online at: https://hydro-stations.hcmr.gr/. Accessed on: 05/11/2024.

- Oo, H.T.; Zin, W.W.; Kyi, C.T. Analysis of streamflow response to changing climate conditions using SWAT model. Civil Engineering Journal 2020, 6, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, Y.; Dimitriou, E. A Large-Scale Nature-Based Solution in Agriculture for Sustainable Water Management: The Lake Karla Case. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.; Singh, D.K.; Islam, A.; Sarangi, A. Multi-site calibration of hydrological model and assessment of water balance in a semi-arid river basin of India. Quaternary International 2021, 571, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriasi, D.N.; Arnold, J.G.; Van Liew, M.W.; Bingner, R.L.; Harmel, R.D.; Veith, T.L. Model evaluation guidelines for systematic quantification of accuracy in watershed simulations. Transactions of the ASABE 2007, 50, 885–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapes, K. L.; Pricope, N. G. Evaluating SWAT model performance for runoff, percolation, and sediment loss estimation in low-gradient watersheds of the Atlantic coastal plain. Hydrology 2020, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, Y.; Makropoulos, C.; Baltas, E.; Mimikou, M. SWAT parameterization for the identification of critical diffuse pollution source areas under data limitations. Ecological modelling 2011, 222, 3500–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WFD program conducted by Hellenic Centre for Marine Research HCMR. Monitoring and recording of the status (quality, quantity, pressures, and uses) of surface waters of Greece” (MIS 5001676), under the Operational Program: “Transport infrastructure, environment and sustainable development” 2014–2020, financed by the Hellenic Ministry of the Environment and the European Regional Development Fund. Available online at: https://wfd.hcmr.gr/. Accessed on: 16/11/2024.

- Skoulikidis, N.T.; Amaxidis, Y.; Bertahas, I.; Laschou, S.; Gritzalis, K. Analysis of factors driving stream water composition and synthesis of management tools—A case study on small/medium Greek catchments. Science of the Total Environment 2006, 362, 205–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannoulis, K.D.; Vlontzos, G.; Karyotis, T.; Bartzialis, D.; Danalatos, N.G. Assessing the efficiency of switchgrass different cultural practices for pellet production. Land use policy 2014, 41, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoulis, K.D.; Karyotis, T. Sakellariou-Makrantonaki, M.; Bastiaans, L.; Struik, P.C.; Danalatos, N.G. Switchgrass biomass partitioning and growth characteristics under different management practices. NJAS-Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 2016, 78, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbersen, H.W.; Christian, D.G.; El Bassem, N.; Alexopoulou, E.; Pignatelli, V.; Van Den Berg, D. Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) as an alternative Energy crop in Europe. Initiation of a productivity network. Final Report Fair 5-CT97-3701 “Switchgrass”, 2001, pp. 1–91. Available online at: www.switchgrass.nl. Accessed on: 09/12/2024.

- Goldstein, J.; Tarhule, A.; Brauer, D. Simulating the hydrologic response of a semiarid watershed to switchgrass cultivation. Hydrology Research 2014, 45, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, K.E.; Jha, M.K.; Zhang, Y.K.; Gassman, P.W.; Wolter, C.F. Impact of land use and land cover change on the water balance of a large agricultural watershed: Historical effects and future directions. Water Resources Research, 2008, Volume 44. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ale, S.; Rajan, N.; Morgan, C.L.S.; Park, J. Hydrological responses of land use change from cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) to cellulosic bioenergy crops in the Southern High Plains of Texas, USA. GCB Bioenergy 2016, 8, 981–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ale, S.; Rajan, N.; Srinivasan, R. Modeling the effects of land use change from cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) to perennial bioenergy grasses on watershed hydrology and water quality under changing climate. Agricultural Water Management 2017, 192, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Femeena, P. V.; Sudheer, K. P.; Cibin, R.; Chaubey, I. Spatial optimization of cropping pattern for sustainable food and biofuel production with minimal downstream pollution. Journal of environmental management 2018, 212, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curk, M.; Glavan, M. Assessing and Mapping the Environmental Impacts of Best Management Practices in Nitrate-Vulnerable Areas. Water 2023, 15, 2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Liu, W. Nitrate contamination of groundwater in an agroecosystem in Zhangye Oasis, Northwest China. Environmental Earth Sciences 2010, 61, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoulis, K. D.; Danalatos, N. G. Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) nutrients use efficiency and uptake characteristics, and biomass yield for solid biofuel production under Mediterranean conditions. Biomass and Bioenergy 2014, 68, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).